Abstract

Spastin and katanin sever and destabilize microtubules. Paradoxically, despite their destructive activity they increase microtubule mass in vivo. Here we combine single-molecule fluorescence total internal reflection and electron microscopy to show that the elemental step in microtubule-severing was the generation of nanoscale damage throughout the microtubule by active extraction of tubulin heterodimers. These damage sites were repaired spontaneously by GTP-tubulin incorporation rejuvenating and stabilizing the microtubule shaft. Consequently, spastin and katanin increased microtubule rescue rates. Furthermore, newly severed ends emerged with a high-density of GTP-tubulin that protected them against depolymerization. The stabilization of the newly severed plus-ends and the higher rescue frequency synergized to amplify microtubule number and mass. Thus, severing enzymes regulate microtubule architecture and dynamics by promoting GTP-tubulin incorporation within the microtubule shaft.

Summary

Severing enzymes spastin and katanin extract tubulin dimers from microtubules and amplify microtubule arrays by promoting microtubule lattice repair

The plasticity of the microtubule cytoskeleton follows from multiple levels of regulation through microtubule-end polymerization and depolymerization, crosslinking, and microtubule severing. Microtubule severing generates internal breaks in microtubules. It is mediated by three enzymes of the AAA (ATPases associated with various cellular activities) ATPase family – katanin, spastin and fidgetin (reviewed in (1)) that are widely conserved in animals and plants. They are critical for the generation and maintenance of complex non-centrosomal microtubule arrays in neurons (2–5) and the plant cortex (6–8), and regulate meiotic and mitotic spindle morphology and length (9–12), cilia biogenesis (13, 14), centriole duplication (14, 15), cytokinesis (16, 17), axonal growth (18), wound healing (19) and plant phototropism (7, 8). Both spastin and katanin are associated with debilitating diseases. Spastin is mutated in hereditary spastic paraplegias, neurodegenerative disorders characterized by lower extremity weakness due to axonopathy (reviewed in (1)). Katanin mutations cause microcephaly, seizures and severe developmental defects (14, 15, 20). Disease mutations impair microtubule severing (21, 22).

Paradoxically, in many of these systems, the loss of the microtubule-severing enzyme leads to a decrease in microtubule mass (reviewed in (1)). Spastin loss causes sparse disorganized microtubule arrays at Drosophila synaptic boutons (2) , and impaired axonal outgrowth and sparse microtubule arrays in zebrafish axons (23). Similarly, katanin loss leads to sparse cortical microtubule arrays in Arabidopsis (8, 24), while in C. elegans meiotic spindles it results in loss of microtubule mass and number (25). It was hypothesized that the observed increase in microtubule number and mass results from templated nucleation from the severed ends (26, 27). This is an attractive mechanism for rapidly generating microtubule mass, especially in the absence of centrosome-based nucleation as in neurons or meiotic spindles. This severing-dependent microtubule amplification has been directly observed in plant cortical microtubule arrays (8). However, for this amplification to operate, the GDP-tubulin lattice exposed through severing would have to be stabilized because GDP-microtubules depolymerize spontaneously in the absence of a stabilizing GTP-cap (28–31). We wanted to study this paradox and combined time- resolved transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy to directly observe the effects of severing enzymes spastin and katanin on microtubule structure and dynamics in vitro.

Severing enzymes nanodamage microtubules

Because light microscopy-based severing assays fail to capture ultrastructural features of severing intermediates due to resolution limitations, we used negative-stain TEM to capture and image spastin-mediated microtubule severing intermediates in vitro using purified, recombinant spastin. To minimize severing intermediate breakage, we performed severing reactions directly on EM grids. These on-grid reactions revealed a high density of “bites” into the protofilament structure (Fig. 1) that resulted in the removal of tubulin dimers. Severing reactions performed with taxol-stabilized microtubules in the tube and then transferred to EM grids by pipetting produced many short microtubules with blunt ends (fig. S1A), similar to those previously reported in vitro with katanin (32) indicating that the fragile nanodamaged severing intermediates are lost during pipetting. Thus, in our on-grid severing setup, we were able to capture intermediates that were otherwise disrupted by shear forces introduced by pipetting. Upon prolonged incubation (>5min), severing was driven to completion on the EM grid, with severe destruction of the microtubule structure indicating that the intermediates observed were on-pathway (fig. S1B). The nanoscale damage sites were observed with GDP microtubules regardless of whether they were stabilized with taxol or not (Figs. 1A, B) or polymerized with the non-hydrolyzable analog GMPCPP (Fig. 1C). The nanodamage we observed in vitro is reminiscent of that observed by electron tomography in freeze-substituted C. elegans meiotic spindles (25). The same extraction of tubulin dimers and protofilament fraying was observed if reactions were performed in solution and then microtubules were deposited on an EM grid without pipetting to avoid shear (Fig. 1D; Materials and Methods). In control reactions without the enzyme the integrity of the lattice was preserved, (figs. S1C and S1D), while in the spastin treated samples nanodamage sites were detected every ~2.2 μm (fig. S1D). Time-course experiments revealed a gradual increase in nanoscale damage as well as the number of shorter microtubules (Fig. 1E). We extended our TEM analyses to the microtubule-severing enzyme katanin (Figs. 1F, 1G and figs. S1E–H). As with spastin, TEM revealed that katanin microtubule severing also proceeds through progressive extraction of tubulin dimers out of the microtubule.

Fig. 1. Spastin and katanin extract tubulin out of the microtubule.

(A–C) Microtubules in the absence or presence of 33 nM spastin. The reaction proceeded on-grid for one minute and was imaged using negative stain TEM (Materials and Methods). Boxed regions shown at 2X magnification in insets. Scale bar, 50 nm. Microtubules imaged at 30,000x magnification. Arrows indicate nanoscale damage sites. (D) Fields of GMPCPP microtubules incubated with buffer or 25nM spastin. Severing proceeded in solution and reactions were passively deposited on EM grids, negatively stained and visualized by TEM (Materials and Methods). Arrows indicate nanoscale damage. Microtubules imaged at 13,000x magnification; boxed regions, 30,000x magnification. Scale bar, 50 nm. (E) Microtubule length distribution after spastin incubation; cyan, control; dark and light grey, 2 and 5 min incubation, respectively. (F) Fields of GMPCPP microtubules incubated with buffer or 100 nM katanin imaged as in (D). Scale bar, 50 nm. (G) Microtubule length distribution after katanin incubation; cyan, control; dark and light grey, 2 and 5 min incubation, respectively.

Tubulin incorporation repairs nanodamage

Our TEM analysis showed that GMPCPP microtubules, taxol-stabilized microtubules or non-stabilized microtubules, do not sever even when peppered with spastin and katanin induced nanodamage and do not catastrophically depolymerize upon removal of the initial tubulin subunits. This raised the possibility that this damage could be repaired by incorporation of tubulin subunits from the soluble pool, as recently observed with mechanically damaged or photodamaged microtubules in vitro (33, 34). To test this hypothesis, we preassembled HiLyte647 fluorescently-labeled GMPCPP microtubules and incubated them with spastin (or katanin) and ATP to initiate severing (Materials and Methods). Under these conditions, we observed rare severing events (Fig. 2). Upon perfusion of soluble HiLyte488-labeled tubulin and GTP we observed tubulin incorporation in discrete patches along microtubules. These were numerous, far exceeding the number of severing events. Mock-treated microtubules showed no incorporation of tubulin into microtubules (Figs. 2A–C). The tubulin concentration used was below the critical concentration for tubulin polymerization. Similar results were obtained with taxol-stabilized microtubules (fig. S2). Because photodamage can induce lattice defects in fluorescently labeled microtubules (34), we also performed experiments with unlabeled microtubules visualized by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy and also observed incorporation of tubulin in spastin-treated microtubules, but not in controls (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. Spastin and katanin catalyzed nanoscale damage is repaired by spontaneous tubulin incorporation.

(A, B) HiLyte647-labeled GMPCPP microtubules (magenta) incubated with buffer (A) or 10 nM spastin for 35 s (B) followed by incubation with 1 μM HiLyte488-labeled GTP-tubulin (cyan) and washing of excess tubulin (Materials and Methods); Arrows designate severing events. (C) HiLyte647-labeled GMPCPP microtubules (magenta) incubated with 2 nM katanin for 90 s followed by incubation with 1 |iM HiLyte488-labeled GTP-tubulin (cyan) and washing of excess tubulin (Materials and Methods). Arrows designate severing events. (D) DIC imaged unlabeled GMPCPP microtubules incubated with 10 nM spastin followed by incubation with 1 μM HiLyte488-labeled GTP-tubulin (cyan) and washing of excess tubulin (Materials and Methods). Insets show severing events. Scale bar, 5 μm.

In time-course experiments both the number of repaired nanoscale damage sites and mean fluorescence along repaired microtubules increased over time (figs. S3A, S3B, S4A, S4B). The size of the repair sites (full-width-at-half-maximum, FWHM, figs. S3C, S4C) was initially diffraction-limited and shifted toward larger values at longer incubation times, indicating an expansion of the damage as detected by soluble GTP-tubulin incorporation. Frequent nanoscale damage events were visible when severing events were extremely sparse: as early as 35 s, the density of spastin-induced nanoscale damage sites was 0.35±0.01 μm−1, compared to 0.0008±0.0004 μm−1 for severing events (figs. S3A, S3D). Thus, most nanoscale damage events did not lead to macroscopic severing events. Once a sufficient number of tubulin dimers was removed from the lattice, the microtubule unraveled and a macroscopic severing event was visible. Consistent with this, we observed an abrupt increase in mesoscale severing at 120 and 90s for spastin and katanin, respectively (figs. S3D, S4D).

Next, we probed the effect of soluble tubulin on spastin microtubule severing by performing severing assays in the presence of fluorescently-labeled soluble tubulin (fig. S5). This allowed us to detect microtubule nanoscale damage and severing simultaneously. Spastin-induced severing was not significantly affected with 100 nM tubulin even though we observed incorporation of HiLyte-488 labeled tubulin into microtubules (Fig. 3A and fig. S5; Materials and Methods). However, severing was considerably reduced in the presence of 2μM soluble tubulin (Fig. 3A), and in this case, tubulin fluorescence intensity at repair sites was also significantly higher (Fig. 3B). Thus, the tubulin extraction activity of the enzyme was not significantly inhibited by soluble tubulin as proposed previously for katanin (35), but the rate of tubulin incorporation at nanodamage sites increased with tubulin concentration and slowed down the progression to a macroscopic severing event. This higher tubulin incorporation at damage sites delays (and can even prevent) the completion of a severing event. Consistent with this, the time between the incorporation of HiLyte488-tubulin at a nanoscale damage site and the completion of a severing event was longer in the presence of 2μM tubulin compared to 100 nM (Fig. 3C). Thus, while almost all nanoscale damage sites detectable under our experimental conditions proceeded to complete severing within 65 s after tubulin incorporation in the presence of 100 nM soluble tubulin, only 47% did so at 2 μM tubulin (Fig. 3D). We also monitored live the addition of single fluorescently-labeled tubulin dimers by TIRF microscopy (Fig. 3E; Materials and Methods). Fluorescence intensity analyses revealed that repair proceeded mainly through the incorporation of tubulin heterodimers and not the addition of larger tubulin polymers or aggregates because the fluorescence intensity distribution of incorporated tubulin was similar to the one of single tubulin subunits immobilized to glass (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3. Incorporation of soluble tubulin into spastin-induced nanoscale damage sites inhibits microtubule severing.

(A) Severing rates in the presence of soluble tubulin (n= 31, 28 and 36 microtubules for no tubulin, 100 nm and 2 μM tubulin, respectively from multiple chambers). Error bars, s.e.m. (B) Intensity distribution of fluorescent tubulin puncta incorporated at spastin-induced nanodamage sites; n=50 and 49 puncta from multiple chambers for 100 nM and 2 μM tubulin, respectively. Bars, mean and s.d. (C) Repair at damage sites delays severing (n=81 and 83 severing events from multiple chambers for 100 nM and 2μM tubulin, respectively). (D) Fraction of GMPCPP microtubules severed by 20 nM spastin within 65 s of initial tubulin incorporation in the presence of 100nM and 2μM HiLyte488 soluble tubulin; Error bars, s.e.m. in (C) and (D). (E) Live imaging of Alexa488 GTP-tubulin (cyan) incorporation into HiLyte647 GMPCPP microtubules (magenta) after spastin induced damage. Scale bar, 1.5 μm. (F) Fluorescence intensity distribution of Alexa488-labeled tubulin (labeling ratio ~1.0) immobilized on glass (black) or incorporated into spastin induced nanodamage sites (cyan); n=188 and 398 for glass immobilized and microtubule incorporated particles, respectively. (G) Spastin-induced nanodamage and spontaneous tubulin repair of GDP microtubules (magenta) grown from axonemes and stabilized with a GMPCPP cap (bright cyan); spastin (5 nM) and 5 μM soluble HiLyte488 GTP-tubulin (cyan). White arrows, tubulin incorporation sites, yellow arrows, severing events. Scale bar, 5 μm. (H) Average completion time of a severing event after spastin perfusion. GMPCPP microtubules (brown), GMPCPP capped GDP microtubules (grey) in the absence or presence of soluble tubulin; n=36, 63, 34 and 27 microtubules from multiple chambers for GMPCPP, GMPCPP capped GDP microtubules with 0, 2 μM and 5 μM soluble GTP-tubulin, respectively. Bars, mean and s.d.; **** p-value of < 0.0001 determined by two-tailed t-test for (B), (C), (D) and (H).

Severing enzymes introduce GTP-tubulin islands

To rule out repair as an artifact of working with stabilized microtubules (either taxol or GMPCPP-stabilized), we extended our experiments to non-stabilized GDP-microtubules. We polymerized GDP-microtubules from axonemes and stabilized their ends with a GMPCPP cap to avoid spontaneous depolymerization (Materials and Methods). We then introduced spastin in the absence or presence of fluorescently-labeled soluble GTP-tubulin. Within 50 s of introducing 5 nM spastin and 5μM soluble tubulin (tubulin concentrations in vivo are 5–20 μM (36, 37) we observed incorporation of tubulin as puncta along microtubules (Fig. 3G and movie S1). At these enzyme and tubulin concentrations, most tubulin incorporation sites did not progress to a severing event, and the severing rate was considerably lower than in the absence of soluble tubulin (Fig. 3H). However, tubulin incorporation always preceded microtubule-severing. No repair sites were observed in the absence of spastin. Thus, the local balance between active tubulin removal catalyzed by the enzyme and passive tubulin incorporation determines whether a nanodamage site progresses to a mesoscale severing event or fails to do so because of the repair with GTP-tubulin from the soluble pool.

We also visualized the lattice-incorporated tubulin at higher resolution using TEM. We generated recombinant human α1AβIII tubulin with an engineered FLAG-tag at the β-tubulin C-terminus (38). We then used this recombinant tubulin to repair brain microtubules nanodamaged by spastin. The presence of the FLAG-tag on the recombinant tubulin allowed its specific detection both in fluorescence and TEM images using fluorescent or gold-conjugated secondary antibodies against anti-FLAG antibodies (Materials and Methods). Fluorescence microscopy revealed that the recombinant tubulin robustly incorporates along microtubules nanodamaged by spastin with ATP.

No incorporation was detected with spastin and ATPγS (fig. S6). TEM showed the discrete, productive incorporation of recombinant α1AβIII tubulin in islands along microtubules and the absence of tubulin aggregates at nanodamage sites (fig. S7). The anti-FLAG primary and secondary gold-conjugated antibodies are specific for the recombinant tubulin as brain microtubules showed only background antibody decoration (fig. S7C and D). In the absence of recombinant soluble tubulin in the reaction, microtubules were robustly nanodamaged under these conditions (fig. S7E). Moreover, neither recombinant tubulin incorporation nor association with the microtubule lattice were observed by fluorescence and TEM assays with the slow-hydrolyzable analog ATPγS (figs. S6, S7A and C). Thus, soluble tubulin incorporated productively into the microtubule lattice at nanodamage sites created by spastin in an ATP hydrolysis-dependent manner.

Severing enzymes promote rescues

Because spastin and katanin catalyze GTP-tubulin incorporation along microtubules, we next examined their effects on microtubule dynamics. It has been recognized for 30 years that tubulin incorporation into a growing microtubule stimulates hydrolysis of the bound GTP. The resulting GDP-tubulin lattice is unstable, but is protected from depolymerization by a layer of GTP-tubulin. This “GTP-cap” at the microtubule end results from a lag between the GTP hydrolysis rate on the incorporated tubulin and microtubule growth speed (30, 31, 39–42). More recently, islands of GTP-tubulin were detected along microtubules in cells and correlated with rescue (33, 43), the transition from depolymerization to growth, one of the parameters of microtubule dynamic instability. As with stabilized GMPCPP and GDP GMPCPP-capped microtubules, the newly perfused GTP- tubulin rapidly incorporated along the GDP-microtubule lattice of dynamic microtubules in the presence of spastin and katanin with ATP, unlike in the control without ATP where only addition at microtubule ends was visible (Figs. 4A–D, movies S2 and S3). We then characterized microtubule dynamics in the presence of spastin or katanin at physiological concentrations (25 nM; spastin and katanin concentrations in HeLa cells are 46 nM and 28 nM, respectively (37)). At these enzyme concentrations, we observed robust microtubule severing and internal GTP-tubulin incorporation. Both spastin and katanin increased rescue frequencies ~ thirteen and nine-fold, respectively (0.5 ± 0.2 min−1 for control versus 6.6 ± 1.6 min−1 and 4.5 ± 0.7 min−1 for spastin and katanin, respectively; Fig. 4E). While 61% of depolymerization events rescued in the presence of spastin or katanin, only 13% rescued in the control (Fig. 4F). Consistent with their promotion of tubulin exchange along the microtubule shaft, neither spastin nor katanin had a significant effect on rates of microtubule growth and catastrophe (Figs. 4G, H). This is in contrast to other rescue promoting factors like CLASPs, for example, which promote rescue by increasing the on-rate of tubulin dimers at microtubule ends and thus decrease catastrophe and increase growth rates (44) or conventional MAPs like MAP2 which promote rescue by stabilizing the microtubule lattice (45).

Fig. 4. Spastin and katanin promote GTP-tubulin island formation and increase rescues.

(A, B) Time course of a dynamic 10% HiLyte647-labeled microtubule (magenta) at 12 μM tubulin in the presence of 25nM spastin without (A) or with ATP (B) showing HiLyte488-labeled tubulin incorporation (cyan) at the microtubule tip (A) or incorporation along the microtubule in addition to the tip (B). First micrograph for each condition was recorded just before the perfusion of 12 μM 10% HiLyte488-labeled tubulin into the chamber. Scale bar, 2μm. (C, D) Time course of a dynamic 10% HiLyte647-labeled microtubule (magenta) at 12 μM tubulin in the presence of 25nM katanin without (C) or with ATP (D) showing HiLyte488-labeled tubulin incorporation (cyan) at the microtubule tip (C) or incorporation along the microtubule in addition to the tip (D). First micrograph for each condition was recorded just before the perfusion of 12 μM 10% HiLyte488- labeled tubulin into the chamber. Scale bar, 2μm. (E) Rescue frequency at 10 μM tubulin in the absence or presence of 25 nM spastin and 25 nM katanin and ATP; n = 47, 45, and 61 microtubules from multiple chambers for control without enzyme, spastin and katanin, respectively. ****, p-value of < 0.0001 determined by the Mann-Whitney test; error bars, s.e.m. throughout. (F) Probability of rescue of a depolymerizing microtubule in the absence or presence of spastin and katanin with ATP; n = 68, 57, 78 depolymerization events for control, spastin and katanin, respectively. ****, p-value of < 0.0001 determined by two-tailed t-test. (G, H) Growth rates (G) and catastrophe frequency (H) in the absence or presence of spastin and katanin and ATP; n = 56, 37 and 34 growth events for control, spastin and katanin, respectively in (G) and n = 62, 70, and 71 microtubules for control, spastin and katanin, respectively in (H).

In our dynamics assays, tubulin is continually extracted by the enzyme, while at the same time, the lattice is healed with newly incorporated GTP-tubulin that gradually converts into GDP-tubulin. To decouple these processes and establish directly whether the GTP-tubulin islands introduced by these enzymes can act as microtubule rescue sites, we introduced non-hydrolyzable GTP-tubulin islands in the microtubule. For this, we first nanodamaged with spastin or katanin a GMPCPP-capped GDP microtubule and healed it with GMPCPP-tubulin, removed the enzyme and GMPCPP tubulin from the chamber, and initiated microtubule depolymerization through laser ablation close to the GMPCPP-cap (Fig. 5 and S8A-C; Materials and Methods). No GMPCPP- tubulin incorporation was detected in the control performed in the presence of enzyme without ATP. These microtubules depolymerized all the way to the seed upon ablation (Fig. 5B). In contrast, microtubules with GMPCPP-tubulin islands incorporated along their lengths through the ATP hydrolysis-dependent activity of spastin or katanin were stabilized against depolymerization at the location of the island (Fig. 5C), despite the absence of soluble tubulin in the chamber: 75% and 76% paused when they encountered a GMPCPP island introduced by spastin or katanin, respectively (Fig. 5D, figs. S8A, B and C; movie S4). Those that depolymerized through the island showed a decrease in the depolymerization speed (Fig. 5E and fig. S8D). Moreover, fluorescence intensity analysis revealed that GMPCPP-islands that paused depolymerization were statistically significantly brighter than those that did not (Fig. 5F and fig. S8E). Next, we wanted to establish whether these enzyme-generated GMPCPP-islands were competent to support microtubule regrowth. For this, we performed the above experiment, but during the last step we introduced 7 soluble GTP-tubulin into the chamber (Figs. 5A, G and H and movie S5). While at these tubulin concentrations rescue events were very rare in the control, we saw a higher probability of rescue of microtubules with spastin-incorporated GMPCPP islands (Fig. 5I). When the GMPCPP- island did not support a rescue, it did however slow down depolymerization (Fig. 5J). Moreover, fluorescence intensity analysis revealed that GMPCPP-islands that supported rescues were significantly brighter than those that did not (Fig. 5K). Thus, microtubule dynamics measurements and experiments with GMPCPP-tubulin islands indicate that GTP-islands introduced in a microtubule severing enzyme-dependent manner promote microtubule rescue and that there is a minimal local GTP-tubulin density required to robustly support rescue at that site. Because the microtubule rescues when the balance shifts from net tubulin loss to net tubulin addition, it is likely that the correlation between the size of the GTP-tubulin island and rescue probability will vary with tubulin concentration or the presence of MAPs. Thus, smaller GTP-tubulin-islands might still be effective rescue sites at higher tubulin concentrations or in the presence of MAPs that increase the tubulin on-rate.

Fig. 5. Enzyme generated GMPCPP-islands protect against depolymerization and act as rescue sites.

(A) Experiment schematic. GDP microtubules (solid magenta) were polymerized from seeds (black) and capped with GMPCPP-tubulin (magenta outline). Spastin, ATP and GMPCPP-tubulin (green) were added and washed out of the chamber. Microtubules were laser-ablated in the absence (B-F) or presence of GTP-tubulin (G-K) (Materials and Methods). (B) Kymograph of a depolymerizing laser-ablated microtubule (magenta) pre-incubated with spastin, no ATP. (C) Kymographs of depolymerizing laser-ablated microtubules pausing at GMPCPP-tubulin islands (green) introduced by spastin, 1mM ATP. White arrows, pauses. Horizontal scale bars, 5μm; vertical, 10 sec. (D) Pie chart shows proportion of depolymerization events that paused at GMPCPP-islands (white) or did not (grey); n = 44. (E) Depolymerization rates of microtubules without GMPCPP-islands pre-incubated with spastin, no ATP or through GMPCPP-islands introduced by spastin, 1mM ATP; n = 17 and 7 microtubules for no ATP and ATP, respectively. (F) Fluorescence intensity of GMPCPP-islands through which microtubules depolymerized or paused; n = 9 and 14, respectively. (G, H) Kymographs of laser-ablated microtubules in the presence of 7μM soluble GTP-tubulin after pre-incubation with spastin no ATP showing complete depolymerization (G) or rescue (green arrows) at a GMPCPP-island introduced by spastin, ATP (H). Horizontal scale bar, 5μm; vertical, 20 sec. (I) Rescue frequency of laser-ablated microtubules incubated with spastin, with or without ATP; n = 23 and 24 microtubules, respectively. (J) Depolymerization rates in the presence of 7μM GTP-tubulin of microtubules pre-incubated with spastin, no ATP or through GMPCPP-islands introduced by spastin, ATP; n = 9 and 6 microtubules, respectively. (K) Intensity of GMPCPP-islands that did not stop depolymerization (n=6) or at which microtubules rescued in the spastin, ATP condition (n = 9). **, ***, p-values of < 0.01 and 0.001 respectively determined by the Mann-Whitney test. Error bars, s.e.m. throughout.

Severing enzyme-generated GTP-islands recruit EB1

The GTP state of tubulin is recognized by MAPs belonging to the end binding (EB) protein family. EB1 preferentially binds to growing microtubule ends by sensing the GTP (or GDP-Pi) state of tubulin (46, 47). Consistent with the creation of GTP-tubulin islands, in the presence of spastin or katanin and ATP, we observed EB1 not only at the growing ends as in the control, but also as distinct puncta along microtubules (Figs. 6A–D). These are reminiscent of the EB3 puncta observed at sites of tubulin repair after laser-induced damage (34). 89% of the newly-incorporated GTP-tubulin islands co-localized with EB1 (Figs. 6E and F). These EB1 puncta were transient, consistent with the dynamic removal and incorporation of new tubulin into the lattice and the gradual GTP hydrolysis of the incorporated tubulin (Figs. 6A, C, fig. S9 and movie S6). Consistent with a protective effect of the GTP-islands, microtubule dynamics assays in the presence of spastin and EB1 revealed that 74% of rescues were associated with the presence of EB1 at the rescue site (fig. S10A). This number is significantly higher than the prediction given by the random superposition of EB1 puncta and rescue events (74% versus 14%, p < 0.0001 by Fisher test; Materials and Methods). Similarly, 63% of rescues in the presence of katanin occurred at the site of an EB1 spot (fig. S10B) compared to zero when the distribution was randomized (p < 0.00001 by Fisher test, Materials and Methods). Laser ablation of microtubules peppered with EB1 puncta also revealed a dramatic increase in rescue frequency. While 100% of ablation induced depolymerization events rescued within 4s, only 15% did so in the presence of spastin and ATPγS (Figs. 6G and H). Similar results were obtained with katanin (Fig. 6I and movie S7). Thus, the ATP-dependent action of the enzyme that promotes tubulin exchange within the lattice is required for the observed increase in rescue frequency.

Fig. 6. Spastin and katanin generated GTP-tubulin islands recruit EB1.

(A) Time course of EB1-GFP (green) on a dynamic microtubule (magenta) in the presence of 25nM spastin without or with ATP. Scale bar, 2 μm. Line scans on the right show EB1-GFP intensity profiles along the microtubule at indicated times. Intensity profiles start on the microtubule lattice and end at the microtubule tip. (B) Density of EB1-GFP puncta on microtubules incubated without spastin or with spastin without and with ATP; error bars, s.e.m. (C) Time course of EB1-GFP on a dynamic microtubule in the presence of 25nM katanin without and with ATP. Intensity profiles as in (A). (D) Density of EB1-GFP puncta on microtubules incubated without katanin or with katanin without or with ATP; error bars, s.e.m. (E) Co-localization of newly incorporated GTP-tubulin (magenta, top panel) and EB1-GFP (green, middle panel) in the presence of spastin and ATP. Bottom panel, overlay. Images acquired immediately after perfusing enzyme and EB1-GFP into chamber. Scale bar, 2μm. (F) Fluorescence intensity of incorporated tubulin (magenta) and EB1-GFP (green) along the microtubule lattice in (E) showing their co-localization. 89% of tubulin islands co-localize with EB1-GFP (n = 38 puncta from 22 microtubules from multiple chambers measured immediately after perfusion of 10% HyLite647-tubulin). (G) Time course of laser-ablated dynamic microtubules (magenta) incubated with 25 nM spastin, ATPγS (left) or spastin, ATP (right) in the presence of 50 nM EB1-GFP (green) (Materials and Methods). The dotted line marks the ablated region and start of depolymerization. Scale bar, 2 μm. (H, I) Pie charts show fates of plus-ends generated through laser-ablation of microtubules incubated with spastin (H) or katanin (I) with ATPγS or ATP; % of plus-ends that depolymerized (grey) or rescued (white) within 4 s after ablation; n = 13 and 13 microtubules for spastin ATPγS and ATP, respectively, from multiple chambers; n = 54 and 9 microtubules for katanin ATPγS and ATP, respectively, from multiple chambers.

Severing amplifies microtubule mass and number

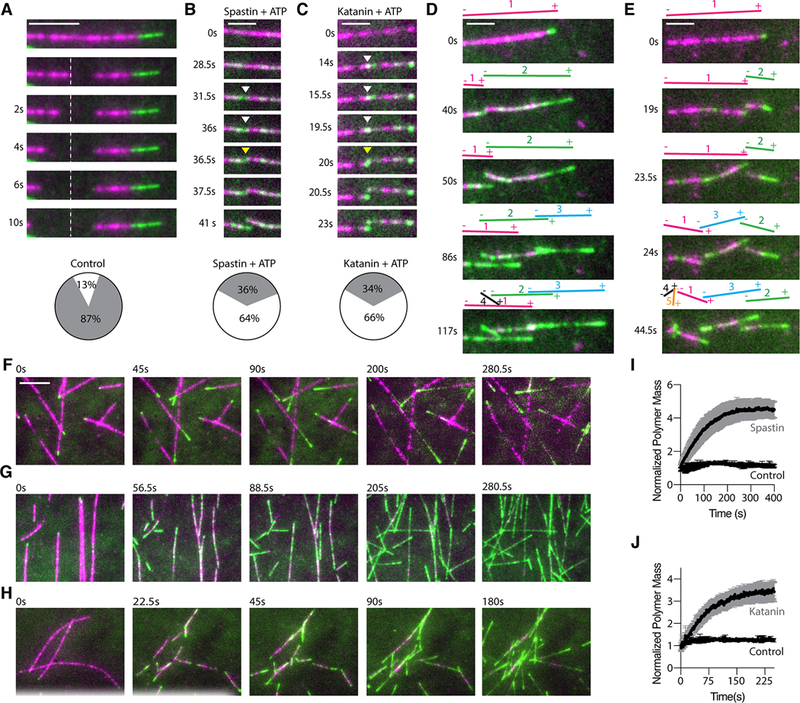

The GDP-tubulin lattice is unstable and when exposed by laser ablation rapidly depolymerized at the plus ends even in the presence of soluble tubulin (Fig. 7A) consistent with classic experiments performed with laser ablated or mechanically cut microtubules (28, 29, 48–51) . Surprisingly, at 12μM tubulin the majority of new plus-ends generated by spastin or katanin were stable and rapidly reinitiated growth (Figs. 7B, C). In contrast, in the absence of either enzyme or in the presence of spastin or katanin and ATPγS new plus-ends generated through laser ablation rapidly depolymerized (Figs. 7A, 6H, 6I). This indicates that it is not the passive binding of the protein that stabilizes the new plus-ends against spontaneous depolymerization but the ATP-dependent incorporation of GTP-tubulin at severing sites. The minus-ends were stable regardless of whether they were generated through enzyme action or laser ablation, consistent with classic earlier experiments using laser ablation (29)(28). Thus, when the local tubulin extraction by spastin or katanin outpaces the rate of tubulin incorporation, a severing event occurs and the newly-severed microtubule ends emerge with a high density of GTP-tubulin that is protective (Figs. 7B, C). Moreover, the plus-ends that depolymerize immediately after severing resume growth after a lower net loss of polymer mass (figs. S8F, G). Thus, the increase in microtubule number with each severing event (Figs. 7D, E) together with the higher rescue frequency synergize to produce a rapid amplification of total microtubule number and mass (Figs. 7F–J).

Fig. 7. Severing enzyme-based microtubule number and mass amplification.

Plus-ends generated through laser ablation depolymerize. Pie chart shows % of plus-ends that are stable (white) or depolymerize (grey) ; n = 32 microtubules from multiple chambers. Scale bar, 5μm. (B, C) Spastin (B) or katanin (C) severed ends emerge with newly incorporated GTP-tubulin and are stable. Pie chart shows % of plus-ends that are stable (white) or depolymerize (grey); n= 96 and 94 for spastin and katanin, respectively from multiple chambers. Scale bar, 2μm. (D, E) Time lapse showing consecutive spastin (D) or katanin (E) induced severing events on a microtubule. Microtubule (magenta), incorporated tubulin (green). Scale bar, 2μm. (F) Time lapse showing microtubule dynamics at 12μM tubulin in the absence of severing enzyme. Green, newly incorporated tubulin at the growing ends. The last two frames are bleach corrected. Scale bar, 5μm. (G, H) Time lapse showing microtubule number and mass amplification through spastin (G) and katanin (H) severing. Green, newly incorporated HiLyte-488 tubulin perfused into the chambers together with the severing enzymes. (I, J) Microtubule mass as a function of time; n = 4, 5 and 4 chambers for control, spastin and katanin, respectively; error bars, s.e.m.

Discussion

The classical view of microtubule dynamics has been that tubulin dimer exchange occurs exclusively at microtubule ends through polymerization and depolymerization (30, 52). By visualizing at the ultrastructural level a severing reaction, we show that spastin and katanin extract tubulin subunits from the microtubule (Fig. 1) and that this ATP hydrolysis-dependent tubulin removal is counteracted by spontaneous lattice incorporation of soluble GTP-tubulin (Figs. 2, 3, 4, figs. S5, S6 and S7). The nanodamaged microtubules do not immediately unravel, but are long- lived enough to have a chance to heal through the productive incorporation of tubulin into the lattice. Because longitudinal lattice contacts are stronger than lateral ones (42), we speculate that tubulin dimer loss from the microtubule wall has a slight longitudinal bias that proceeds along the protofilament. This would give the microtubule a chance to heal before it is severed across and generate GTP-tubulin islands that consists of several tubulin dimers in the longitudinal direction. The geometry of the nanodamage sites and the mechanism of tubulin incorporation and conformational changes at these sites will be an exciting and fundamental question for future exploration.

This mechanism of lattice repair can explain the earlier observation of inhibition of katanin severing by soluble tubulin (35, 53). The ragged, Swiss cheese-nature of the nanodamaged microtubules is conducive to healing, as the incoming tubulin dimers can make stabilizing lateral interactions. Thus, depending on the local rates of the severing enzyme-catalyzed tubulin removal and the spontaneous incorporation of new GTP-tubulin into the lattice, the action of a microtubule-severing enzyme results in a severing event where the newly-emerging ends have a high density of GTP-tubulin or a microtubule that preserves integrity but acquires a GTP-island at the site of enzyme action. The higher GTP density at the newly severed ends can also act to quickly recruit molecular motors and MAPs that can modulate the fate of the newly generated end.

While microtubule repair after defects introduced through laser-induced photodamage (34) or mechanical stress has been reported in vitro (33, 54), our study identifies a family of enzymes as biological agents that promote the ATP-dependent incorporation of GTP-tubulin islands into microtubules. Microtubule repair has a high incidence in vivo at microtubule crossovers or bundles (34) where microtubule-severing enzymes have been shown to act (7, 8, 17, 55). Our findings thus suggest that the high incidence of repair at these sites might not be due exclusively to mechanical damage (34), but also the action of microtubule-severing enzymes. Since spastin and katanin preferentially target glutamylated microtubules (13, 57, 57), they could also selectively rejuvenate through GTP-tubulin incorporation ageing microtubules with accumulated glutamylation marks. GTP-tubulin islands were reported along axonal microtubules (58), a neuronal compartment where severing enzyme act, raising the intriguing possibility that severing enzymes could also be used as quality control and maintenance factors in hyperstable microtubule arrays like those in axons, centrioles and cilia where spastin and katanin are important for their biogenesis and maintenance (2, 5, 13, 14) and where they could serve to remove and replace old, possibly damaged tubulin subunits without affecting overall microtubule organization. It will be thus interesting to establish how impaired lattice repair contributes to the disease phenotypes seen in patients with spastin and katanin mutations

Our study shows that severing enzyme-catalyzed incorporation of GTP-tubulin along microtubules has two physiological consequences: it increases the frequency at which microtubules rescue (Figs. 4, 5 and 6) and stabilizes against depolymerization newly severed plus-ends that emerge with a high density of GTP-tubulin (Fig. 7). Thus, microtubule dynamics can be modulated not only by factors that affect tubulin incorporation at microtubule ends, but by severing enzymes that promote the exchange of tubulin subunits within the microtubule shaft. The synergy between the increased rescue rates and the stabilization of the newly-severed ends leads to microtubule amplification in the absence of a nucleating factor, explaining why, paradoxically, the loss of spastin and katanin results in loss of microtubule mass in many systems (2, 23, 25, 27). Such a mechanism of polymer amplification has parallels to the actin cytoskeleton where severed filaments are used for templated actin polymerization ((26, 59); reviewed in (60)). When severing enzymes are expressed at high levels or are positively regulated, tubulin extraction outpaces repair and the microtubule array disassembles. Cells likely modulate severing activity and the rate of tubulin lattice incorporation through the action MAPs to elicit these two different outcomes. This regulation will be a fascinating area of future exploration.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

Drosophila melanogaster full-length spastin was purified by affinity chromatography and ion exchange as previously described (62). Caenorhabditis elegans MBP-tagged katanin Mei1/Mei2 (12) was purified on amylose resin. The affinity tag was removed by Tobacco Etch Virus protease and the protein was further purified on an ion exchange MonoS column (GE Healthcare) as previously described (63). Peak fractions were concentrated, buffer exchanged into 20 mM Hepes 7.0, 300 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM TCEP and flash frozen in small aliquots in liquid nitrogen. Homo sapiens EB1-GFP was expressed and purified as previously described (64). Human a1AßIII tubulin with an engineered FLAG-tag at the β-tubulin C-terminus was expressed using baculovirus and purified as described previously (38).

Transmission electron microscopy of microtubule severing reactions

Taxol-stabilized GDP microtubules were prepared by polymerizing 10 μl of 100 μM glycerol-free porcine tubulin (Cytoskeleton Inc., Denver, CO) in 80 mM K-PIPES pH 6.8, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 10 % DMSO, 1 mM GTP for 1 hour in 37 °C water bath. Taxol was added to 20 μM final concentration and the reaction was incubated on the bench top for 1–2 hours. Microtubules were loaded on 60 % glycerol cushion (BRB80, 60 % (v/v) glycerol and 20 μM taxol) at 37 °C using a pipette tip with the tip cut off. Non-polymerized tubulin was removed by centrifugation in a TLA100 rotor at 35,000 rpm for 15 min at 37 °C. The pellet was gently re-suspended to 2.5 μM of tubulin in BRB80, supplemented with 20 μM taxol and 1mM GTP at 37 °C using a pipette tip with the tip cut off.

For GDP microtubules, all polymerization and severing reactions were performed at 37 °C. 20 μl of 100 μM glycerol-free porcine tubulin (Cytoskeleton Inc.) was polymerized in 10 % DMSO, 1 mM GTP and 10 mM MgCl2 for 1 hour at 37 °C water bath. The microtubules were passed through 60 % glycerol cushion (BRB80, 60 % (v/v) glycerol and 1mM GTP) using a TLA100 rotor at 53,000xg for 15 min to remove non-polymerized tubulin. The pellet was washed twice using 50 μl buffer (BRB80, 10 % DMSO, 1 mM GTP) and gently re-suspended to 30 μM in the same buffer using a pipette tip with the tip cut off.

GMPCPP microtubules were prepared by polymerizing 20 μl of 100 μM glycerol-free porcine tubulin (Cytoskeleton Inc.) in 1mM GMPCPP in BRB80 (80 mM PIPES-KOH pH6.8, 1mM MgCl2, 1mM EGTA, 1mM DTT) on ice for 5 min and then in a water bath at 37 °C for 1 hour. Non-polymerized tubulin was removed by centrifugation in a TLA100 rotor at 126,000 × g for 5 min at 37 °C. The pellet was washed twice with 50 μl of BRB80 at 37 °C and re-suspended in 50 μl of ice-cold BRB80. The reaction was kept on ice for 30 min and periodically mixed up and down to fully depolymerize microtubules. GMPCPP was added to 1 mM, the polymerization reaction was kept on ice for 10 min and then transferred to 37 °C for 2–4 hrs or overnight. Non-polymerized tubulin was removed by centrifugation and washed as described above. The microtubule pellet was gently re-suspended to 2.5 μM of tubulin in BRB80 using a pipette tip with the tip cut off.

We found that performing severing reactions in the tube followed by pipetting onto electron microscopy grids resulted in microtubule breakage. We therefore first carried out severing reactions on the electron microscopy grid. Briefly, 2μl microtubule solution (at 1 to 3 μM) in BRB80 (80mM PIPES pH 6.8, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA) was applied to a glow-discharged Cu grid, followed by pipetting of 2μl ATP solution (10mM ATP in BRB80 supplemented with 20mM taxol, for taxol stabilized microtubules) and 2μl spastin (at 100 nM). The reaction was allowed to proceed on grid for one minute or as specified, after which the liquid was wicked off with calcium-free filter paper, and the grid was stained with 0.75% (w/v) uranyl formate, and air-dried. Images were collected on a FEI Morgagni 286 electron microscope operated at 80kV and equipped with AMT lens-coupled 1k x 1k CCD camera. For the solution severing reaction time courses, 20 μl of GMPCPP or taxol-stabilized microtubules in BRB80 buffer at 2.5 μM or 1 μM were applied to parafilm followed by addition of 20 μl of 50 nM spastin or 200 nM katanin in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1mM TCEP and 1mM ATP to a final concentration of 25 nM spastin and 100 nM for katanin. For the solution severing reaction time courses of non-stabilized GDP microtubules, 20 μl of 30 μM GDP microtubules in the presence of 10% DMSO were incubated with 2 μl of 20 nM katanin. Buffer without severing enzymes was added to microtubules as a negative control. The severing reactions were incubated for 30 sec, 2 or 5 mins and carbon- coated grids (Carbon Film only on 400 mesh, Ted Pella, Inc.) were dipped in the reactions. Excess liquid was blotted using filter paper. Grids were washed three times with 40 μl BRB80, stained with 0.75 % (w/v) uranyl formate and air-dried. Images were collected on a T12 Technai electron microscope (FEI) equipped with a 2k x2k Gatan US1000 CCD camera. Images were collected at nominal magnifications of 550x, 13,000x or 30,000x corresponding to pixel sizes of 84 Å/pix, 3.55 Å/pix, or 1.54 Å/pix, respectively.

TIRF based assays of tubulin incorporation into stabilized microtubules damaged by spastin and katanin

Double-cycled, GMPCPP-stabilized microtubules (65) were polymerized from 2 mg/ml porcine brain tubulin (Cytoskeleton). First polymerization was 1 h, the second polymerization step was at least 4 h to obtain long microtubules. Then microtubules were centrifuged, resuspended in warm BRB80 (80 mM K-PIPES pH 6.8, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA) and stored at 37°C or RT before use. The same results were obtained regardless of whether the storage temperature was 37°C or RT. Taxol-stabilized microtubules (62) were polymerized from 5 mg/ml porcine brain tubulin containing 1% biotinylated and 20% HiLyte647-labeled tubulin (Cytoskeleton) in BRB80 with 10% DMSO, 0.5 mM GTP and 10 mM MgCl2. After 1 h incubation at 37°C, 20 μM Taxol was added and the mixture was further incubated ON. Microtubules were then centrifuged through a 60% glycerol cushion for 12 min at 109,000 g, 35°C. The microtubule pellet was washed with warm BRB80 supplemented with 14.3 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 20 μM Taxol and resuspended gently in the same buffer.

Chambers for TIRF microscopy were assembled as previously described (62). Double-cycled GMPCPP microtubules containing 1% biotinylated tubulin and 20% HiLyte647-labeled tubulin (or unlabeled tubulin for the DIC assays) assembled as above were immobilized in the chamber with 2 mg/ml Neutravidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged by TIRF or DIC microscopy in severing buffer (BRB80 buffer with 2 mg/ml casein, 14.3 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2.5% glycerol, 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 1% Pluronic F127 (Life Technologies) and oxygen scavengers). To introduce and detect nanoscale damage in microtubules (Fig. 2), immobilized microtubules were then incubated with 10 nM spastin or 2 nM katanin in severing buffer for 35 s or 90 s respectively. Microtubules in control experiments were incubated without severing enzyme. The enzyme mixture was then replaced with 1 μM HiLyte488-labeled tubulin (Cytoskeleton), 1 mM ADP, 0.5 mM GTP, 1% F127 Pluronic, 2.5 mg/ml casein in BRB80 and left to incubate for 5 min. The tubulin containing solution was then washed out with 45 μl of BRB80 supplemented with oxygen scavengers, 1.5 mg/ml casein, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 1% F127 Pluronic. Microtubules and HiLyte488-labeled tubulin were imaged by TIRF. Multiple fields of view were imaged. The same assay was performed for taxol-stabilized microtubules, but in this case the repair step was performed with 0.1 μM soluble tubulin to prevent microtubule nucleation in the presence of taxol. For time course experiments, the same protocol was used except that microtubules were incubated with 2 nM spastin (fig. S3) or 2 nM katanin (fig. S4) for 35–120 sec. Control microtubules were incubated without severing enzyme for 120 sec. 1 μM HiLyte488-labeled tubulin was used for the repair step. For repair with 1 μM recombinant human tubulin (fig. S6), nanodamaged microtubules were incubated for 5 min with recombinant tubulin. Unincorporated tubulin was washed away and tubulin incorporated into microtubules was detected by anti-FLAG M2 antibodies (Sigma Aldrich, diluted 1:500) and goat anti-mouse antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, diluted 1:1000). All assays were performed at room temperature. Details regarding image acquisition and analysis are described in the subsection below.

Image acquisition and analysis of tubulin incorporation in GMPCPP-and taxol-stabilized microtubules by TIRF microscopy

Images were acquired using a Nikon Ti-E microscope equipped with a 100× 1.49 NA oil objective and a TI-TIRF adapter (Nikon). The 488 excitation laser (Coherent Inc.) was set at 20 mW and the 647 nm laser (Coherent Inc) was set to 2 mW before being coupled into the Ti-TIRF optical fiber (Nikon). Two-color simultaneous imaging was performed using a TuCAM (Andor) device that splits the emission on to two separate EMCCD cameras (Andor iXon 897). The excitation and emission were split by a quad band dichroic (Semrock) and the emission was further split by an FF640 filter (Semrock) and further filtered with a FF01–550/88 (Semrock) for the 488 channel and a FF01–642/LP (Semrock) for the 640 channel. The Tucam imaging system introduces an extra 2X magnification yielding a final pixel size of 77 nm. The images from the two cameras were aligned by first imaging a grid of spots (Nanogrid MiralomaTech) on each camera and using the GridAligner plug-in for ImageJ.

DIC illumination was provided by a SOLA-SE-II (Lumencor) coupled to the microscope by a liquid light guide. A standard set of polarizer and analyzer (Nikon 100 X-II High NA/Oil) prisms were used and the image was captured on a CoolSNAP (Photometrics) camera. The final pixel size for DIC images was 65 nm. Raw DIC images were processed using an FFT bandpass filter. DIC images were scaled and transformed to overlay with fluorescent images by imaging fluorescent microtubules in both channels for image registration. The entire imaging setup was controlled by Micro-Manager (66).

For data shown in figs. S3 and S4, images were analyzed using scripts in ImageJ and MATLAB. First, the offset between 640 and 488 channels was corrected with the GridAligner plugin. Then microtubules were selected with 7 px-wide line selection and line scans were generated. These line scans were imported into a MATLAB script that identified the peaks in the 488 channel and recorded the number, intensity and full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) of the repair sites. The FWHM for a diffraction-limited spot was obtained using 100 nm TetraSpeck beads (Thermo Fischer Scientific). Data were exported to PRISM software for graphing.

Transmission electron microscopy of microtubules repaired with recombinant tubulin

GMPCPP microtubules at 1 μM concentration in 1x BRB80 were applied to parafilm in a humidity chamber and incubated with 20 nM spastin in microtubule-severing buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 300 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP and 0.5 mM ATP). Buffer containing 0.5 mM ATPγS instead of ATP was used as a control. Severing was allowed to proceed for 30 seconds followed by addition of 0.6 μM soluble FLAG-tagged single-isoform recombinant neuronal human α1AβIII tubulin to repair the microtubule lattice in the presence of 1 mM GTP and 5mM ADP to inactivate the enzyme. The repair reaction was carried out for 5 min. Microtubules were then stabilized by the addition of 5 volumes of 0.2% glutaraldehyde in 1xBRB80 (80mM PIPES, 1mM MgCl2, 1mM EGTA). After 3 minutes, crosslinking was quenched by the addition of Tris-HCl pH 7.5 to 20 mM final concentration and crosslinked microtubules were transferred into a 10 ml centrifuge tube (Beckman Coulter). The microtubule severing and healing procedure was repeated three more times, reactions were pooled into the same centrifuge tube and microtubules were then spun down in a MLA-80 rotor at 100,000 × g for 15 min at 30 °C. The microtubule pellet was gently washed with 200 μl of 1x BRB80 at 37 °C twice and re-suspended in 50 μl of warm 1x BRB80. 5 μl of 6.7 μM of monoclonal mouse-raised anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma Aldrich) and 5 μl of 11.45 μM of goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated to 4 nm spherical gold nanoparticles, C11–4-TGAMG-50, (Nanopartz) were added to microtubules to label repaired sites. Antibody labeling was allowed to proceed for 5 min and the reaction was mixed with 10 volumes of 30 % glycerol in 1x BRB80. Microtubules in 30% glycerol were loaded on 1x BRB80 cushion containing 40% glycerol and spun down onto glow-discharged carbon-coated grids (Carbon Film only on 400 mesh, Ted Pella, Inc.) at 4,200 x g for 20 min at 30 °C. Excess liquid was blotted using filter paper. Grids were washed three times with 30 μl of BRB80, stained with 0.75 % (w/v) uranyl formate and air-dried. Images were collected on a T12 Technai electron microscope (FEI) equipped with a 2k x 2k Gatan US1000 CCD camera. Images were collected at nominal magnifications of 6,800x and 18,500x corresponding to pixel sizes of 6.8 Å/pix, 2.5 Å/pix, respectively. Images in fig. S7F were collected on a TF20 electron microscope (FEI) equipped with a K2 camera (Gatan). Images were collected at 50,000x magnification and 9,600x magnifications corresponding to pixel sizes of 0.73 Å/pix and 3.65 Å/pix, respectively.

Live imaging of severing and tubulin incorporation into nanodamaged GMPCPP- microtubules and GMPCPP-capped GDP-microtubules

To observe microtubule severing and tubulin incorporation at damage sites simultaneously (Fig. 3 and figs. S5A–C), GMPCPP-stabilized double-cycled microtubules labeled with 1% biotin and 20% HiLyte647-tubulin were immobilized in imaging chambers. Image acquisition was started using 100 ms continuous exposure in the 647 and 488 channels simultaneously and the chamber was perfused with severing buffer containing 0.5 mM GTP, 20 nM spastin and 0, 0.1 or 2 μM HiLyte488-labeled tubulin. Severing rates were calculated by manual counting of severing events (microtubule breaks) as a function of time. Tubulin incorporation sites were readily visible in the 488 channel. To observe the live incorporation of single tubulin dimers into microtubules damaged by spastin (Figs. 3F, G), double-cycled GMPCPP microtubules composed of 20% HiLyte647- labeled and 1% biotinylated tubulin were immobilized in imaging chambers as above. The chamber was then perfused with severing buffer and images of microtubules were acquired. Microtubules were then incubated for 30 sec with 20 nM spastin in severing buffer. Image acquisition was started during the spastin incubation step and a solution containing fluorescently labeled tubulin (50 nM Alexa488-labeled tubulin (PurSolutions LLC, USA) in BRB80 with 2 mg/ml casein, 14.3 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ADP, 0.5 mM GTP, 1% Pluronic F127 and oxygen scavengers) was flushed in. Images were acquired for 5 min at 10 Hz in the 488 nm channel. After tubulin perfusion, the 640 laser was turned off to prevent photobleaching or microtubule photodamage. Images of fluorescent tubulin molecules landing on the microtubule were analyzed using a 7×7 pixel box and the intensity of tubulin molecules incorporated into the microtubule was calibrated against the intensity of single tubulin dimers obtained by immobilizing 0.5 nM Alexa488 tubulin on glass with an anti-ß tubulin antibody (SAP.4G5, Sigma Aldrich) and imaging under the same conditions.

For imaging of non-stabilized microtubules GDP microtubules with a GMPCPP cap, sea urchin axonemes purified as described (67) were non-specifically adhered to the coverslip and 15 μM tubulin containing 20% HiLyte647 tubulin, and 1mM GTP added to start microtubule growth from the axonemes. After the desired microtubule length was achieved (10–20 μm), the solution was exchanged quickly to introduce HiLyte488 tubulin (20%) and 0.5 mM GMPCPP. After the growth of the GMPCPP cap, tubulin and nucleotide were washed out and spastin (5 nM) was introduced in the chamber with 1 mM ATP in the absence or presence of soluble tubulin at 2 μM (500 nM HiLyte488 tubulin + 1.5 μM unlabeled tubulin) or 5 μM (500 nM HiLyte488 tubulin + 4.5 μM unlabeled tubulin) and 0.5 mM GTP. Polymerization and imaging were performed at 30°C.

Microtubule dynamics measurements and EB1 recognition of lattice-incorporated GTP- tubulin

TIRF microscopy chambers were prepared as described above. 10% HiLyte647-labeled microtubules were polymerized at 30°C at 10 μM tubulin. 25 nM spastin or katanin and 10 μM porcine brain tubulin containing 10% HyLite647-labeled tubulin was perfused into the chamber in severing assay buffer (50 mM KCl, 1% F127 Pluronic, 0.2 mg/ml casein, 6.2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1.5% glycerol, 0.1% methylcellulose 4000cP and oxygen scavengers in 1xBRB80) with 1 mM GTP and 1 mM ATP) together with 50 nM EB1-GFP. Images were acquired in the 647 and 488 channels simultaneously at 2 Hz. Microtubule rescues are defined as transition of microtubules from shrinkage to growth. Rescue frequency was calculated as the number of rescues divided by the time spent depolymerizing. Catastrophes are defined as the transition of microtubules from growth to shrinkage. Catastrophe frequency was calculated as the number of catastrophes divided by the time spent in the polymerization state. The EB1 puncta and the microtubule rescue site were considered co-localized when the distance between the EB1 spot and the end of the depolymerizing microtubule was less than two pixels. The cutoff for an EB1 puncta was defined as having a mean intensity in a 5×5 pixel box that is at least 3 standard deviations above the mean background EB1 lattice intensity. Background EB1 lattice intensity was determined from control chambers without severing enzymes. Background EB1 lattice intensity was the same in the absence of severing enzymes or the presence of severing enzymes but in the absence of ATP. For statistical significance calculation, rescue site analysis was also performed using synthetic data generated by shifting the position of the EB1 spots by 7 pixels on the microtubule (alternatively, both towards the plus and the minus ends).

For the GTP-tubulin and EB1-GFP co-localization experiments shown in Fig. 6E, microtubule extensions were grown in the absence of fluorescent tubulin for 8 minutes at 30°C at 12 μM porcine brain tubulin (Cytoskeleton) in severing assay buffer. 20 nM spastin, 50nM EB1-GFP and 12μM porcine brain tubulin containing 10% HyLite647-labeled tubulin was perfused into the chamber in severing assay buffer. Image acquisition was started during perfusion in the 640 and 488 channels simultaneously at 5 Hz. The offset between the 640 and 488 channels was corrected using a nanogrid (Nanogrid Miraloma Tech) and the GridAligner plug-in in ImageJ.

Laser ablation of microtubules with spastin or katanin generated GMPCPP-islands

GMPCPP-stabilized unmodified microtubule seeds were immobilized on glass. To pre-grow microtubules, 16μM tubulin containing 12.5% HiLyte647-labeled tubulin with 1mM GTP was perfused into the chamber and incubated for 10 minutes at 30°C. Microtubules were then capped using 6μM tubulin with 10% HiLyte 647 and 0.5mM GMPCPP. The chamber was washed after 2 minutes with severing assay buffer without GTP and then incubated with 4nM spastin, 6μM tubulin containing 25% HiLyte-labeled 488 tubulin in the presence of 200μM GMPCPP in severing assay buffer (50 mM KCl, 1% F127 Pluronic, 0.2 mg/ml casein, 6.2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2.5% glycerol, 0.1% methylcellulose 4000cP and oxygen scavengers in 1xBRB80) with or without 1mM ATP for 3 minutes. The chamber was washed with buffer containing severing assay buffer. Microtubules were ablated with a 405nm laser at 40% power using the iLas laser illuminator (BioVision). Images in the 488 and 647 channels were acquired sequentially with 100 ms exposure. For the rescue frequency measurements, 15% HiLyte647-labeled tubulin at 7μM in severing assay buffer containing 1mM GTP was perfused into the chamber. For the katanin experiments, the chamber was washed after microtubule capping with severing assay buffer without GTP and then incubated with 20nM katanin and 8μM tubulin containing 25% HiLyte-labeled 488 tubulin in the presence of 200μM GMPCPP in severing assay buffer with or without ATP for 45 sec. Microtubule depolymerization rates through the GMPCPP islands were determined by dividing the length of the island by the time it takes to depolymerize through it.

Laser ablation of dynamic microtubules with enzyme-generated GTP islands

TIRF microscopy chambers were prepared as described above. HiLyte647-labeled microtubule extensions were polymerized for 8 minutes at 30°C at 12 μM porcine brain tubulin (Cytoskeleton) containing 20% HiLyte647-labeled tubulin in severing assay buffer. 25 nM spastin or katanin, 50nM EB1-GFP and 12μM porcine brain tubulin containing 20% HyLite647-labeled tubulin was perfused into the chamber in severing assay buffer with ATP or ATPγS. Microtubules were ablated using a DeltaVision OMX™ with the 405nm laser at 100% power for 1 sec or with a 405nm laser at 40% power using an iLas laser illuminator (BioVision). Images were acquired in the 647 and 488 channels at 5 Hz on the DeltaVision OMX and 2.9Hz on the iLas system..

Live imaging of tubulin incorporation and severing into dynamic microtubules

Chambers for TIRF microscopy were prepared as described above. GMPCPP-stabilized, unmodified microtubules containing 2% biotinylated tubulin were immobilized with 0.1 mg/ml NeutrAvidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Microtubule extensions were polymerized for 12 minutes at 30°C at 10 or 12 μM porcine brain tubulin (Cytoskeleton) containing 10% HiLyte647 tubulin in severing assay buffer (50 mM KCl, 1% F127 Pluronic, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP, 0.2 mg/ml casein, 6.2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1.5% glycerol, 0.1% methylcellulose 4000cP and oxygen scavengers in 1xBRB80). Then, 25 nM katanin or spastin with 12 μM porcine brain tubulin containing 10% HyLite488-labeled tubulin was perfused into the chamber in severing assay buffer.

Images were acquired with 488 and 640 lasers simultaneously at 2 Hz at 100 ms exposure. The incorporation of the HiLyte488 tubulin was immediately visible upon perfusion only at microtubule tips in the control and along the microtubules and the dynamic tips in the enzyme and ATP conditions. Total polymer mass was obtained by measuring the background corrected total integrated fluorescence in both the 488 and 640 channels. The laser ablation controls were performed at the same enzyme and tubulin concentrations but with 1mM ATPγS. Microtubules were ablated with a 405nm laser at 40% power using an iLas laser illuminator (BioVision) for the katanin experiments and the Deltavision OMX for spastin.

Quantification and Data Analysis

N numbers and statistical tests are reported for all experiments in figure legends. All experiments were performed multiple times and only representative images are shown. ImageJ was used for image analysis. Prism (Graphpad) was used for graphi006Eg and statistical analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank A. Szyk, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) for purified spastin and katanin and Xufeng Wu, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) for help in the Light Microscopy Core.

Funding: NG is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. A.M.D. is supported by NIH grant R01GM121975. A.R.M. is supported by the intramural programs of NINDS and NHLBI.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data and material availability: All data needed to understand and assess the conclusions of this research are available in the main text and supplementary materials. Information and requests for reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the corresponding author, Antonina Roll-Mecak, Antonina@mail.nih.gov

References and Notes

- 1.Roll-Mecak A, McNally FJ, Microtubule-severing enzymes. Current opinion in cell biology 22, 96–103 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherwood NT, Sun Q, Xue M, Zhang B, Zinn K, Drosophila spastin regulates synaptic microtubule networks and is required for normal motor function. PLoS Biol 2, e429 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trotta N, Orso G, Rossetto MG, Daga A, Broadie K, The hereditary spastic paraplegia gene, spastin, regulates microtubule stability to modulate synaptic structure and function. Current Biology 14, 1135–1147 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone MC et al. , Normal spastin gene dosage is specifically required for axon regeneration. Cell reports 2, 1340–1350 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad FJ, Yu W, McNally FJ, Baas PW, An essential role for katanin in severing microtubules in the neuron. The Journal of cell biology 145, 305–315 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoppin-Mellet V, Gaillard J, Vantard M, Katanin’s severing activity favors bundling of cortical microtubules in plants. The Plant Journal 46, 1009–1017 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Q, Fishel E, Bertroche T, Dixit R, Microtubule severing at crossover sites by katanin generates ordered cortical microtubule arrays in Arabidopsis. Current Biology 23, 2191–2195 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindeboom JJ et al. , A mechanism for reorientation of cortical microtubule arrays driven by microtubule severing. Science 342, 1245533 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang D, Rogers GC, Buster DW, Sharp DJ, Three microtubule severing enzymes contribute to the “Pacman-flux” machinery that moves chromosomes. The Journal of cell biology 177, 231–242 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNally K, Audhya A, Oegema K, McNally FJ, Katanin controls mitotic and meiotic spindle length. The Journal of cell biology 175, 881–891 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loughlin R, Wilbur JD, McNally FJ, Nedelec FJ, Heald R, Katanin contributes to interspecies spindle length scaling in Xenopus. Cell 147, 1397–1407 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNally K et al. , Katanin maintains meiotic metaphase chromosome alignment and spindle structure in vivo and has multiple effects on microtubules in vitro. Molecular biology of the cell 25, 1037–1049 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma N et al. , Katanin regulates dynamics of microtubules and biogenesis of motile cilia. The Journal of cell biology 178, 1065–1079 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu WF et al. , Katanin p80 regulates human cortical development by limiting centriole and cilia number. Neuron 84, 1240–1257 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mishra-Gorur K et al. , Mutations in KATNB1 cause complex cerebral malformations by disrupting asymmetrically dividing neural progenitors. Neuron 84, 1226–1239 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connell JW, Lindon C, Luzio JP, Reid E, Spastin couples microtubule severing to membrane traffic in completion of cytokinesis and secretion. Traffic 10, 42–56 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guizetti J et al. , Cortical constriction during abscission involves helices of ESCRT-III- dependent filaments. Science 331, 1616–1620 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karabay A, Yu W, Solowska JM, Baird DH, Baas PW, Axonal growth is sensitive to the levels of katanin, a protein that severs microtubules. The Journal of neuroscience 24, 5778–5788 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charafeddine RA et al. , Fidgetin-Like 2: a microtubule-based regulator of wound healing. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 135, 2309–2318 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yigit G et al. , A syndrome of microcephaly, short stature, polysyndactyly, and dental anomalies caused by a homozygous KATNB1 mutation. American journal of medical geneticsPart A 170, 728–733 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roll-Mecak A, Vale RD, The Drosophila homologue of the hereditary spastic paraplegia protein, spastin, severs and disassembles microtubules. Current biology 15, 650–655 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang K et al. , Microtubule minus-end regulation at spindle poles by an ASPM-katanin complex. Nature cell biology 19, 480 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood JD et al. , The microtubule-severing protein Spastin is essential for axon outgrowth in the zebrafish embryo. Human molecular genetics 15, 2763–2771 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burk DH, Ye Z-H, Alteration of oriented deposition of cellulose microfibrils by mutation of a katanin-like microtubule-severing protein. The Plant Cell 14, 2145–2160 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srayko M, O’Toole ET, Hyman AA, Muller-Reichert T, Katanin disrupts the microtubule lattice and increases polymer number in C. elegans meiosis. Current biology : CB 16, 1944–1949 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ribbeck K, Mitchison TJ, Meiotic spindle: sculpted by severing. Current biology 16, R923–R925 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roll-Mecak A, Vale RD, Making more microtubules by severing: a common theme of noncentrosomal microtubule arrays? The Journal of cell biology 175, 849–851 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker R, Inoue S, Salmon E, Asymmetric behavior of severed microtubule ends after ultraviolet-microbeam irradiation of individual microtubules in vitro. The Journal of cell biology 108, 931–937 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran P, Walker R, Salmon E, A metastable intermediate state of microtubule dynamic instability that differs significantly between plus and minus ends. The Journal of cell biology 138, 105–117 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchison T, Kirschner M, Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature 312, 237–242 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlier MF, Pantaloni D, Kinetic analysis of guanosine 5’-triphosphate hydrolysis associated with tubulin polymerization. Biochemistry 20, 1918–1924 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang D et al. , Drosophila katanin is a microtubule depolymerase that regulates cortical- microtubule plus-end interactions and cell migration. Nature cell biology 13, 361–369 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaedel L et al. , Microtubules self-repair in response to mechanical stress. Nature materials 14, 1156–1163 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aumeier C et al. , Self-repair promotes microtubule rescue. Nature cell biology 18, 1054–1064 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bailey ME, Sackett DL, Ross JL, Katanin Severing and Binding Microtubules Are Inhibited by Tubulin Carboxy Tails. Biophysical journal 109, 2546–2561 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hiller G, Weber K, Radioimmunoassay for tubulin: a quantitative comparison of the tubulin content of different established tissue culture cells and tissues. Cell 14, 795–804 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Itzhak DN, Tyanova S, Cox J, Borner GH, Global, quantitative and dynamic mapping of protein subcellular localization. Elife 5, e16950 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vemu A et al. , Structure and dynamics of single-isoform recombinant Neuronal Human Tubulin. Journal of Biological Chemistry, jbc. C116. 731133 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carlier M-F, Guanosine-5′-triphosphate hydrolysis and tubulin polymerization. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 47, 97–113 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carlier MF, Pantaloni D, Assembly of microtubule protein: role of guanosine di-and triphosphate nucleotides. Biochemistry 21, 1215–1224 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carlier MF, Didry D, Pantaloni D, Microtubule elongation and guanosine 5′-triphosphate hydrolysis. Role of guanine nucleotides in microtubule dynamics. Biochemistry 26, 4428–4437 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.VanBuren V, Odde DJ, Cassimeris L, Estimates of lateral and longitudinal bond energies within the microtubule lattice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99, 6035–6040 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dimitrov A et al. , Detection of GTP-tubulin conformation in vivo reveals a role for GTP remnants in microtubule rescues. Science 322, 1353–1356 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Bassam J et al. , CLASP promotes microtubule rescue by recruiting tubulin dimers to the microtubule. Developmental cell 19, 245–258 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ichihara K, Kitazawa H, Iguchi Y, Hotani H, Itoh TJ, Visualization of the stop of microtubule depolymerization that occurs at the high-density region of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2). Journal of molecular biology 312, 107–118 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zanic M, Stear JH, Hyman AA, Howard J, EB1 recognizes the nucleotide state of tubulin in the microtubule lattice. PloS one 4, e7585 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maurer SP, Fourniol FJ, Bohner G, Moores CA, Surrey T, EBs recognize a nucleotide-dependent structural cap at growing microtubule ends. Cell 149, 371–382 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spurck TP et al. , UV microbeam irradiations of the mitotic spindle. II. Spindle fiber dynamics and force production. The Journal of cell biology 111, 1505–1518 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brugués J, Nuzzo V, Mazur E, Needleman DJ, Nucleation and transport organize microtubules in metaphase spindles. Cell 149, 554–564 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nicklas RB, Lee GM, Rieder C, Rupp G, Mechanically cut mitotic spindles: clean cuts and stable microtubules. Journal of cell science 94, 415–423 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tirnauer JS, Salmon ED, Mitchison TJ, Microtubule plus-end dynamics in Xenopus egg extract spindles. Molecular biology of the cell 15, 1776–1784 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howard J, Hyman AA, Microtubule polymerases and depolymerases. Current opinion in cell biology 19, 31–35 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vale RD, Severing of stable microtubules by a mitotically activated protein in Xenopus egg extracts. Cell 64, 827–839 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Forges H et al. , Localized mechanical stress promotes microtubule rescue. Current Biology 26, 3399–3406 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang C et al. , KTN80 confers precision to microtubule severing by specific targeting of katanin complexes in plant cells. The EMBO journal 36, 3435–3447 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valenstein ML, Roll-Mecak A, Graded control of microtubule severing by tubulin glutamylation. Cell 164, 911–921 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lacroix B et al. , Tubulin polyglutamylation stimulates spastin-mediated microtubule severing. The Journal of cell biology 189, 945–954 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakata T, Niwa S, Okada Y, Perez F, Hirokawa N, Preferential binding of a kinesin-1 motor to GTP-tubulin-rich microtubules underlies polarized vesicle transport. The Journal of cell biology 194, 245–255 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan AY, Bailly M, Zebda N, Segall JE, Condeelis JS, Role of cofilin in epidermal growth factor-stimulated actin polymerization and lamellipod protrusion. The Journal of cell biology 148, 531–542 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DesMarais V, Ghosh M, Eddy R, Condeelis J, Cofilin takes the lead. J Cell Sci 118, 19–26 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ziolkowska NE, Roll-Mecak A, In vitro microtubule severing assays. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 1046, 323–334 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zehr E et al. , Katanin spiral and ring structures shed light on power stroke for microtubule severing. Nature structural & molecular biology 24, 717–725 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Albee AJ, Wiese C, Xenopus TACC3/maskin is not required for microtubule stability but is required for anchoring microtubules at the centrosome. Molecular biology of the cell 19, 3347–3356 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gell C et al. , Purification of tubulin from porcine brain. Microtubule Dynamics: Methods and Protocols, 15–28 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Edelstein AD et al. , Advanced methods of microscope control using ^Manager software. Journal of biological methods 1, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gibbons I, Fronk E, A latent adenosine triphosphatase form of dynein 1 from sea urchin sperm flagella. Journal of Biological Chemistry 254, 187–196 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.