Abstract

Recent investigations have elucidated the influence of the Strong Black Woman (SBW) Schema on the mental health and treatment seeking behaviors of Black women in the United States. However, the SBW schematic characteristics that produce depression have yet to be identified. The current study fills this void in the literature through a quantitative examination of how characteristics of the SBW Schema relate to depressive symptomology. Analyses were based on 194 participants, including college students (n = 98) and community members (n = 96), ranging in age from 18 to 82 years-old (M = 37.53, SD = 19.88). As hypothesized, various manifestations of self-silencing were found to significantly mediate the relationship between the perceived obligation to manifest strength (a SBW characteristic) and depressive symptomatology. The present study advances the idea that depressive symptoms are related to endorsement of the SBW Schema and highlights self-silencing as a mechanism by which this relationship occurs. These results offer evidence and clarification of the impact of the SBW Schema on Black women’s mental health and identify specific points of intervention for mental health practitioners conducting therapeutic work with Black women. We provide recommendations for future research to avoid pathologizing strength and we discuss the implications and potential benefits of integrating a Womanist theoretical perspective into counseling for Black women, a population that has historically underutilized mental health resources.

Keywords: African American women, mental health, psychological distress, counseling, depression, Superwoman, gender roles, Strong Black Woman

“Black Superwomen” are at risk for psychological turmoil and premature health deterioration according to a burgeoning body of research that has identified the Black Superwoman or Strong Black Woman (SBW) construct as a risk factor for negative physical and mental health outcomes (Donovan & West 2015; Harrington, Crowther, & Shipherd, 2010; Watson & Hunter 2015; Woods-Giscombé, 2010). To date, most studies of the SBW Schema have been qualitative and theoretical in nature. Few scholars have attempted quantitatively to identify explanatory mechanisms for the relation between SBW endorsement and negative mental health outcomes. The current study addresses this void in the literature through a quantitative examination of SBW Schema characteristics and their association to depressive symptomology, offering timely evidence and clarification of the impact of the SBW Schema on the mental health of Black women in the United States, a population that has historically underutilized counseling and other mental health resources (Brown et al., 2010).

Strong Black Woman Schema

Birthed in response to the harsh realities of intersectional oppression (i.e., racism and sexism) during enslavement (Harris-Lacewell, 2001), the SBW Schema is an amalgamation of beliefs and cultural expectations of incessant resilience, independence, and strength that guide meaning making, cognition, and behavior related to Black womanhood (Abrams, Maxwell, Pope, & Belgrave, 2014). As a result of continuously conjuring resilience as a response to physical and psychological hardships, many Black women have mastered the art of portraying strength while concealing trauma—a balancing act often held in high esteem among Black women.

The SBW Schema functions as a cultural ideal and psychological coping mechanism for many Black women (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009). A SBW is a self-proclaimed warrior who exudes psychological hardiness and endurance despite adversity. As a result of her intersecting identities— as a woman, a Black person, and an individual who identifies as a SBW— a SBW independently assumes a multiplicity of responsibilities and roles, chief among them are provider and caretaker. She is proud to be both Black and a woman and often utilizes religion and spirituality to sustain her strength (Abrams et al., 2014; Woods-Giscombé, 2010).

The SBW Schema and Negative Mental Health Outcomes

“When a Black woman suffers from a mental disorder, the overwhelming opinion is that she is weak [which] is intolerable.” – Meri Danquah (Danquah, 1998, p. 20)

Black women’s identification with the pursuit of strength has been linked to several pernicious psychological outcomes, including distress, depression (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009; Donovan & West, 2015), anxiety (Watson & Hunter, 2015), and binge eating to quell psychological distress (Harrington et al., 2010). In qualitative studies, Black women have described being overwhelmed by pressures to embody strength and be resilient for their families and communities (Abrams et al., 2014; Woods-Giscombé, 2010). In spite of these feelings, many Black women also perceive pressure to refrain from inconveniencing others with their emotional issues and needs. As such, help-seeking behavior is diametrically opposed to the identity of a SBW because they are hesitant to seek tangible and intangible support, express emotional needs, or exhibit vulnerability (Watson-Singleton, 2017; Woods-Giscombé, 2010). As highlighted by other studies, psychological distress often goes unnoticed because it is veiled by an exhibition of strength (Abrams et al., 2014; Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009). This self-silencing aspect of the SBW Schema is of particular interest to us in the current study because it has been linked to depressive symptomatology and may be a barrier to perceiving a need for and to seeking mental health services.

Depression among U.S. Black women has significant implications for the social and psychological well-being of the Black community. In 2014, among persons 18 years of age and older, the percentages of Non-Hispanic Black women who reported sadness, hopelessness, and worthlessness was significantly greater than those reported by Non-Hispanic White women (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2016). Most relevant to the SBW, 9.9% of Non-Hispanic Black women reported “everything is an effort” as compared to 5.8% of Non-Hispanic White women (CDC, 2016). According to the 2013–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, depression was almost twice as common among women as among men and the proportion of adults with depression increased with decreasing family income level (Brody, Pratt, Hughes, & National Center for Health Statistics, 2018), which has implications for socioeconomically disadvantaged Black women. For example, Blacks living below the poverty level, as compared to those over twice the poverty level, are three times more likely to report psychological distress. Moreover, Blacks are 10% more likely to report having serious psychological distress than Non-Hispanic Whites. Despite these statistics, Black women are unlikely to utilize psychological services (Brody et al., 2018), which may be linked to a cultural obligation to self-silence as a SBW.

Theory of Self-Silencing

According to the theory of silencing the self, silencing behaviors involve inhibiting self-expression to maintain relationships and circumvent retaliation, possible loss, and conflict (Jack & Dill, 1992). The theory suggests women “bite their tongues” due to a loss of self in a relationship or fear of one’s authentic self, rejection, loss, and/or alienation. Self-silencing manifests in four distinct behaviors: (a) silencing the self (i.e., women not directly asking for what they want or telling others how they feel), (b) divided-self (i.e., women presenting a submissive exterior to the public despite feeling hostility and anger), (c) care as self-sacrifice (i.e., women putting needs and emotions of others ahead of their own), and (d) externalized self-perceptions (i.e., women evaluating themselves based on external [cultural] standards) (Jack & Ali, 2010). Most relevant to the current study are self-silencing and externalized self-perceptions.

Because outward expressions of discomfort, pain, and/or a need for assistance could jeopardize one’s reputation for fortitude, self-silencing is a hallmark characteristic of a SBW. Thus, instead of facilitating a “loss of self,” as proposed by the theory of silencing the self, self-silencing appears to protect Black women’s projected image of a “strong self.” Nevertheless, incessant attempts to muzzle self-expression can be challenging because self-silencing can have serious mental and physical health consequences when exercised over time (Jack & Ali, 2010). For example, self-denial of one’s needs and desires can create an internal homeostatic imbalance that promotes dysfunction of neurobiological systems and subsequent depression (Jack, 2011). In addition, whereas some Black women may engage in self-silencing because of relationships or internalized fears, others may utilize selfsilencing to fulfill the cultural (externalized) obligation to display strength (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009). Socialized expectations of strength drive many Black women’s externalized self-perceptions (Abrams et al., 2014), which colors how they appraise and subsequently interact with their environment (Bem, 1981). When society’s standards conflict with personal standards, Black women may self-silence by muting internal standards and by adhering to externalized self-perceptions, a suppressive behavior that may render SBW-identified women susceptible to depressive symptoms.

According to the theory of silencing the self, social situations and interpersonal relationships can influence a woman’s schematic interpretations to affect her vulnerability to depression (Jack & Dill, 1992). In this regard, endorsement of the SBW Schema and associated silencing behaviors (e.g., self-silencing and externalized self-perceptions) should be related to depressive symptoms among Black women. By examining the impact of distinct forms of self-silencing on the relationship between perceived strength obligations and depressive symptoms, the current study better clarifies specific mechanisms contributing to psychological distress experienced by some Black women who internalize the cultural expectation of strength. In doing so, our study contributes to the literature by moving beyond theorized relationships to empirically tested associations.

The Present Study

Depression among U.S. Black women remains an understudied topic. Recently, researchers have found endorsement of the SBW Schema to predict higher anxiety and depression symptoms (Watson & Hunter, 2015). However, the ways in which SBW characteristics lead to depression have yet to be identified. Thus, the current study investigated whether self-silencing mediates the relation between perceived strength obligations and depression. We hypothesized that (a) increased endorsement of the perceived obligation to manifest strength will predict greater depressive symptomatology (Hypothesis 1) and (b) self-silencing (Hypothesis 2a) and externalized self-perceptions (Hypothesis 2b) will mediate the relation between the perceived obligation to manifest strength and depressive symptomatology.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from 250 women. During the cleaning process, 13 cases were deleted because participants did not identify as African American (an inclusion criterion of the study). An additional 40 cases were removed because they did not identify as a Strong Black Women (9 did not claim this identity, 30 were unsure, and 1 did not respond). Lastly, three cases with 20% or more missing data were removed. Thus, analyses were based on 194 participants, including college students recruited via SONA (n = 96) and local community members (n = 98). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 82 years-old (M = 37.53, SD = 19.88). Most of the sample (n = 175, 90%) had a higher- education background. More than half of the sample (n = 119, 60%) reported having a romantic partner and 26% (n = 51) were married. Detailed demographic data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Demographics | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 94% (183) |

| Bisexual | 3% (5) |

| Gay/Lesbian | 2% (3) |

| Other | .5% (1) |

| Income | |

| <$50,00 | 43 % (84) |

| $50,000- $100,000 | 37 % (71) |

| $100,001- $200,000 | 14 % (28) |

| >$200,000 | 4% (7) |

| Education | |

| Less than a high school diploma | 2 % (3) |

| High school graduate | 8 % (16) |

| Some College | 40 % (78) |

| Associate’s Degree | 5 % (10) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 18 % (35) |

| Master’s Degree | 24 % (46) |

| Graduate/Professional Degree | 3% (6) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Have a Romantic Partner | 61% (119) |

| Married | 26% (51) |

| Employment Status | |

| Full Time | 33% (63) |

| Part Time | 28% (55) |

| Unemployed | 22% (43) |

| Homemaker | 2% (4) |

| Disability Benefits | 1% (2) |

| Retired | 14% (27) |

Measures and Procedure

Depressive symptomatology.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was used to assess depression symptoms. The CES-D is a 20-item scale that allows respondents to indicate frequency of symptoms experienced in one week’s time on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 (Rarely or none of the time: Less than one day) to 3 (Most or all of the time: 5–7 days). Example items include: “I had crying spells” and “I could not get going.” Higher summed scores indicate the presence of greater depressive symptomatology. The CES-D has demonstrated good internal consistency and construct validity in previous research with U.S. Black women (Hawkins, Miller, & Stewart, 2015) and in the current study (α = .91).

SBW Schema: Obligation to exude strength.

To assess the obligation to manifest strength component of the SBW Schema, the Superwoman subscale from the Stereotypic Roles of Black Women Scale (Thomas, Witherspoon, & Speight, 2004) was used. Examples from the 11-item subscale include: “Black women have to be strong to survive” and “I tell others that I am fine when I am depressed or down.” Responses range from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree) on a 5-point scale. Higher summed scores indicate greater endorsement of a perceived obligation to manifest strength. The Superwoman subscale has demonstrated adequate internal consistency in previous research with U.S. Black women (Donovan & West, 2015) as well as in the current study (α = .78). It is important to note that other dimensions of the SWBWS (e.g., Jezebel and Sapphire) were not examined because they were not relevant to the current study.

Silencing the self.

The Silencing the Self-Scale (STSS; Jack & Dill, 1992) contains 31 items and is used to assess internal psychological processes associated with depression in women. The current study utilized two of the measure’s subscales: Silencing the Self Subscale and the Externalized Self Perception Subscale. Initially, the Care as Self Sacrifice Subscale was to be included in analyses, however, the low internal consistency of this subscale (α = .48) negated its use in the current study. Overall, the STSS has demonstrated good internal consistency and construct validity in previous research with U.S. Black women (Banks & Xu, 2013).

Silencing the Self subscale.

The Silencing the Self subscale assesses the degree to which individuals inhibit thoughts and behaviors when experiencing negative affect. A sample item from the nine-item subscale is: “I think it’s better to keep my feelings to myself when they conflict with my partner’s.” Responses are indicated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). Higher summed scores indicate greater self-silencing. In the current study, the Silencing the Self Subscale demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .80).

Externalized Self-Perception subscale.

The Externalized Self-Perception subscale assesses the degree to which individuals judge themselves according to sociocultural gendered expectations and standards. A sample item from the six-item subscale is: “I tend to judge myself by how I think other people see me.” Responses are indicated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). Higher summed scores indicate greater externalized self-perceptions. This subscale demonstrated moderately strong internal consistency in the current study (α = .82).

Recruitment.

Convenience and participant-referral sampling strategies were employed for recruitment. SONA, an online research participant management and data collection platform, was used to recruit college students. Community participants were recruited via posted and distributed flyers, email messages, and word of mouth from organizations that serve Black women, including volunteer service organizations, churches, and public service sororities.

Data collection.

College student participants enrolled in the study online through SONA for extra course credit. After digitally consenting to participate in the study, participants completed the questionnaire online via Survey Monkey and were awarded extra course credit upon completion. Community participants completed paper-and-pencil surveys in various community settings (i.e., churches and community centers). When participants arrived at the study location, a researcher greeted them and explained the purpose of the study. Each participant provided written informed consent and then completed a questionnaire comprising measures regarding health and experiences associated with being a Black woman. The order in which measures were presented in the survey was as follows: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977), Stereotypic Roles of Black Women Scale (Thomas, Witherspoon, & Speight, 2004), Silencing the Self-Scale (Jack & Dill, 1992), and demographic questions. After completing the questionnaire, women were thanked for their participation and given a small gift bag that included hair and skin care products, earrings, a mug, and candy (monetary value of approximately $10 USD). The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Results

Data Cleaning and Assumptions for Analysis

Before conducting primary analyses, data were cleaned and screened for outliers. To address missing data, an expectation maximization procedure was used. This procedure was chosen because missing data were randomly distributed across all variables and the procedure yields more accurate estimates of variance (Tabachnick & Fiddell, 2001). To assess normality, residual scatterplots of predicted scores were reviewed, and this assumption was met. Univariate outliers were assessed by examining the saved standardized scores for variables, following guidelines of Tabachnick and Fidell (2001). One univariate outlier was found. To reduce its influence, the score was changed by adding one to the next highest score. To check for multivariate outliers, the Mahalanobis distance was reviewed; however, none was identified. For linearity, a scatterplot was used to ensure that variables did not have a curvilinear relationship; the assumption was met. Multicollinearity was assessed by examining correlations of the variables, and homoscedasticity was assessed by checking whether the residuals were evenly distributed; both assumptions were met. To evaluate hypotheses, we used mediation analyses with bootstrapping (Hayes, 2012) via the PROCESS macro in SPSS (Model 4).

Hypothesis Testing

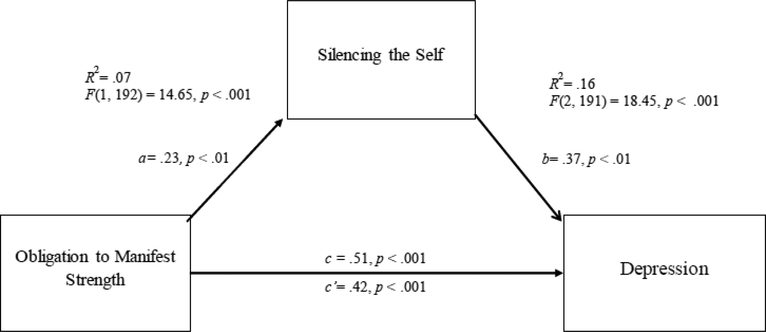

All variables were significantly positively correlated to each other (see Table 2). Regression analyses were used to test hypotheses in mediation models. In the first mediation model (see Figure 1), we predicted that obligation to manifest strength (X) impacts depressive symptomatology (Y) indirectly through silencing the self (M). Hypothesis 1, which predicted increased endorsement of the perceived obligation to manifest strength will predict greater depressive symptomatology, was tested. Results demonstrated that the obligation to manifest strength significantly predicted depressive symptomatology (c = .51, p <.001) and self-silencing (a = .23, p <.001). The mediator, silencing the self, also predicted depressive symptomatology (b = .37, p <.01).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Variables

| Possible | Range | Correlations |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (SD) | Range | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1. Superwoman (SRBWS) | 36.76 (7.17) | 11–55 | 18–54 | (.79) | |||

| 2. Depression Symptomatology (CES- D) |

14.31 (10.66) | 0–80 | 0–48 | .34** | (.90) | ||

| 3. Silencing the Self | 23.15 (6.19) | 9–45 | 9–41 | .26** | .30** | (.81) | |

| 4. Externalized Self Perception | 15.41 (5.28) | 6–30 | 6–29 | .38** | .62** | .52** | (.81) |

Note. Coefficient alphas are reported in parentheses along the diagonal of the correlation matrix. *p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Model testing the mediation of the relationship between Obligation to Manifest Strength and Depression through Silencing of Self after controlling for age and income. Values along each pathway report the standardized coefficients.

To test Hypothesis 2a, that self-silencing would mediate the relationship between obligation to manifest strength and depressive symptomatology, bootstrapping was used at a 95% confidence interval with 5,000 samples. Results revealed the estimate of the indirect effect was significant (ab = .09, 95% CI [.03 - .18]) because the confidence interval did not include zero. Thus, Hypothesis 2a was fully supported, suggesting that the more strongly Black women feel obligated to be strong, they more likely they are to silence themselves and, in turn, develop depressive symptoms.

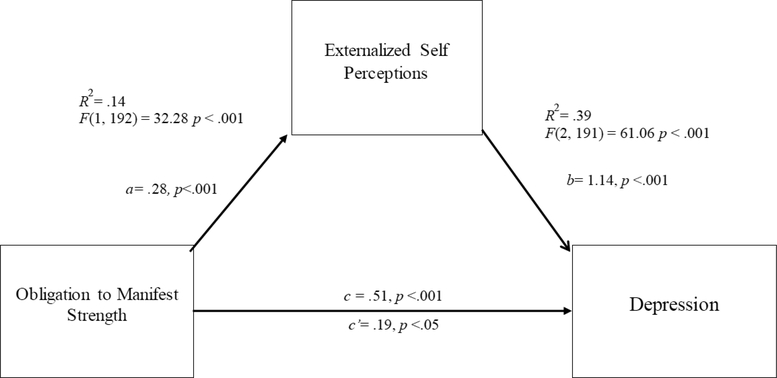

Next, Hypothesis 2b, that externalized self -perceptions would mediate the relationship between obligation to manifest strength and depressive symptomatology, was tested. A mediation analysis was again used to examine the relationships between obligation to manifest strength (X), externalized self-perceptions (M), and depressive symptomatology (Y). Similar to the first model, obligation to manifest strength significantly predicted depressive symptomatology (c= .51, p <.001) and externalized self-perceptions (a = .28, p <.001). Externalized self-perceptions also predicted depressive symptomatology (b = 1.14, p <.001). A bootstrapping analysis at a 95% confidence interval using 5,000 samples was used to investigate the indirect effect of externalized self-perceptions on the relationship. Externalized self-perceptions significantly mediated the relationship between obligation to manifest strength and depressive symptomatology (ab = .31, 95% CI [.18, .47]). Supporting our hypothesis, the pressure to exude strength manifests in depressive symptoms through externalized self-perceptions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Model testing the mediation of the relationship between Obligation to Manifest Strength and Depression through Externalized Self Perceptions after controlling for age and income. Values along each pathway report the standardized coefficients.

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to better understand the mechanisms through which internalizing the SBW Schema leads to depressive symptomology. Because most empirical investigations of the SBW Schema to date have been qualitative, the current study stands as one of a few quantitative studies to confirm a relationship between internalization of the SBW Schema and psychological distress. Moreover, it adds to the literature by highlighting externalized self-perceptions and silencing the self as key explanatory mechanisms in depressive symptomatology related to the schema.

Consistent with extant research, our findings suggest it can be overwhelming for U.S. Black women to fulfill the unrelenting expectation to display strength (Woods-Giscombé, 2010). Specifically, Donovan and West (2015) examined depression symptoms among Black women and found that moderate-to-high levels of SBW endorsement increased the relationship between stress and depressive symptoms, whereas low levels of SBW endorsement did not. Harrington and colleagues (2010) also found internalization of the SBW Schema to have a negative impact on the mental health of Black women, such that high levels of internalization were related to emotion regulation difficulties and binge eating for psychological reasons.

Additionally, our findings lend support for self-silencing and externalized self-perceptions as mechanisms by which the SBW’s obligation to manifest strength results in depressive symptomatology. These results are significant because they offer empirical evidence for the theorized association between the SBW and self-silencing. Highlighting this connection is relevant to mental health wellness because prior studies have explicated the psychological toll of self-silencing. For example, self-silencing is related to physiological changes linked to psychological stress and depression (Jack & Ali, 2010). The related construct of emotion suppression (i.e., the conscious effort of inhibiting emotional arousal) has also been associated with negative mental health outcomes including major depressive disorder (Beblo et al., 2012). Thus, identifying various forms of self-silencing to explain the relationship between strength and depression establishes a need and creates an opportunity for mental health professionals to intervene in culturally specific ways.

It is important to note that endorsement of externalized self-perceptions, as a form of self-silencing, is rooted in a broader sociocultural context. Emerging as a response to sexist norms, self-silencing behaviors are used to manage societal expectations of gendered behavior (Jack, Ali, & Dias, 2014). When examining intersections of race and gender, self-silencing behaviors, namely endorsement of externalized self-perceptions, are used to cope with experiences of gendered racism (Lewis, Mendenhall, Harwood, & Huntt, 2013). Oppressive stereotypes (e.g., Mammy and Superwoman) and stifling sociocultural conditions (e.g., racism, sexism, gerrymandering, and lack of educational and employment opportunities; Collins, 2005) have created an environment in which U.S. Black women must negotiate harmful psychological messages and externalized perceptions, while meeting the cultural expectation of strength. To achieve this psychologically taxing balancing act, many Black women endorse the SBW schema and call upon self-silencing to quiet their present but hidden needs for assistance. Thus, it is plausible that as a result of intersecting social and cultural identities, depression among Black women can operate and present differently as seen in the Sisterella Complex (explained in detail in Jones & Shorter-Gooden, 2003).

Previous approaches to understanding the psychology of women have failed to capture this process and other social complexities among Women of Color because they paint limited, broad strokes of lived experiences. In contrast, the current study contributes to the justification for grounding mental health research with Black women in intersectionality, a theory postulating that social identities, including but not limited to race, gender, and cultural identities, interlock to simultaneously influence a person’s lived experiences and mental well-being (Cole, 2009).

Practice Implications

In the current study we found that an overwhelming majority (over 80%) of Black women identified as a SBW, highlighting the dominance of this cultural ideal. As stated by Romero (2000, p. 225) in a book describing approaches in psychotherapy for Black women, the SBW Schema

… helps [a Black woman] to remain tenacious against the dual oppressions of racism and sexism…. It keeps her from falling victim to her own despair but it also masks her vulnerabilities… As much as it may give her the illusion of control, it keeps her from identifying what she needs and reaching out for help.

The cultural obligations to manifest strength can make it difficult to prevent or treat mental health issues among U.S. Black women and has likely contributed to this population’s underutilization of psychological services (Neufeld, Harrison, Stewart, & Hughes, 2008). Although Black women are disproportionately affected by mental health disorders, admitting that one is overwhelmed or in need of help conflicts with the idealized, unwavering capabilities of being a SBW.

As such, traditional counseling models (i.e., those that largely rely on the individualization of clinical issues) may prove ineffective in comprehensively addressing Black women’s mental health needs. Practitioners who serve U.S. Black women must be cognizant of this potential cultural barrier. Specifically, traditional treatment modalities, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, may be counterproductive in treating Black women due to their over-emphasis on symptom reduction instead of recognizing, unpacking, and addressing social, cultural, and historical factors that contribute to the development of symptoms. For example, cognitive reframing without acknowledgement of the sociocultural demands placed on Black women may not be effective in long-term symptom reduction. Moreover, these orientations may pathologize Black women for exuding strength without validating how it is at times useful and encouraged in their lives.

Given consistently low rates of mental health service utilization among Black women, there is a need for mental health professionals to use innovative methods to reach a group that has historically avoided engaging in self-care and seeking assistance (Brown et al., 2010; Ward & Heidrich, 2009). Moreover, as our findings suggest, this group may be more difficult to reach due to normative subscriptions to the SBW schema. As such, practitioners must take this cultural factor and group tendency into account when attempting to increase the number of Black women who receive mental health support. For example, instead of expecting Black women to seek counseling and related mental health care, mental health professionals should consider the identity-incongruent nature of this help-seeking behavior and may instead find it more useful to bring care to Black women. Introducing Black women to counseling and mental health services in familiar environments, such as homes, community centers, and faith-based institutions, may assist with increasing access to and utilization of services. The integration of mental health care into traditional medical agencies may also increase access to care.

Additionally, ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association (2016) and the American Counseling Association (2014) charge mental health clinicians with the provision of culturally competent care. Training counselors to recognize that depression may manifest in Black women in nuanced ways, as described in detail by Jones and Shorter-Gooden (2003), will be imperative to facilitating the delivery of services tailored to the needs of Black women. Further, it is possible that counseling approaches that acknowledge Black women’s trepidations and facilitate exploration of their intersecting identities (e.g., gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, subscription to the SBW schema) could also be effective in helping Black women engage in more adaptive coping strategies. Indeed, culturally tailored interventions increase client retention and are up to four times more effective than non-tailored interventions (Griner & Smith, 2006; Ward & Brown, 2015).

Integrating a Womanist theoretical perspective within counseling and research may also be beneficial. Womanism emphasizes the current survival mechanisms of Black women while striving to encourage healing and balance (Lindsay-Dennis, 2015). This is ideal because it refrains from victim-blaming. At its core, Womanism focuses on achieving wellness among Women of Color to allow one’s optimal self to be expressed (Bryant-Davis & Comas-Días, 2016). Other tenets of Womanism include empowerment, resistance, and embracing multiple and varied identities among Black women (King, 2003). From this perspective, clinicians and researchers can advance adaptive coping mechanisms associated with Womanism as well as challenge maladaptive coping linked to endorsement of the SBW Schema. Moreover, after psychosocial needs are identified, self-care planning should commence so as to promote adaptive coping strategies (e.g., use of spirituality and reliance on social support systems) in place of maladaptive coping associated with the SBW Schema. Overuse of any coping mechanism can be problematic, despite its utility, hence a need for flexibility.

Additionally, counselors should empower Black women in courses of treatment by fostering agency and autonomy while exploring broader sociocultural systems. Processing societal messages and mainstream stereotypes in therapy may lead to the deconstruction of externalized self-perceptions, where Black women can learn to differentiate their self-image from the external views of others. Counselors may also collaborate with clients to emphasize culturally congruent coping and redefine strength as intentional self-care and resilience (Sanchez-Hucles, 2016).

Limitations

Despite numerous strengths of the current study, there are several limitations. First, the regionally limited sample and cross-sectional design of the study preclude generalizability as well as predictive and causal conclusions. Another limitation of our study relates to the use of the Stereotypic Roles for Black Women Scale to measure aspects of the SBW Schema. As stated earlier, there is no known validated instrument to measure the SBW Schema. Thus, researchers have resorted to teasing apart the construct and measuring its characteristics individually with previously validated measures. Furthermore, Care as Self-Sacrifice (an aspect of the SBW Schema) was excluded from analyses due to low internal consistency of the measure used (i.e., Care as Self-Sacrifice Subscale of the Silencing the Self Scale). Despite these limitations, findings from our study build upon SBW research and aid in better understanding associated mental health consequences.

Future Research Directions

The small-to-medium sized effects of our findings indicate that other variables can account for the relationship between perceived obligations to manifest strength and depressive symptoms. As such, future research can examine other factors that may mediate the relationship between internalization of the SBW Schema and depressive symptomology. This could include racial/ethnic identity, perceptions of racism, encounters with sexism, and/or experiences of gendered racism. Future research with longitudinal designs could also assist in identifying causal relationships that can explicate the consistency of identification as a SBW (e.g., whether the construct is one that maintains stability over time). It is possible that Black women call upon or identify with the SBW Schema variably and at certain developmental periods. Additionally, future research can strengthen our understanding of the Schema by validating a SBW measure. With a validated instrument to capture the construct, researchers would be better able to evaluate the SBW Schema as it relates to mental and even physical health outcomes. An additional area for future research is to examine all of the dimensions of self-silencing as they relate to aspects of the SBW.

Conclusion

Although U.S. Black women have historically and relentlessly felt pressure to be strong for their families and communities, many struggle with depending on others for support. Despite the experience of psychological distress, many Black women find it foreign and difficult to emote openly. This may be especially true for those who endorse the SBW Schema. As the results of the current study indicate, the incessant need to showcase strength can be psychologically taxing, and self-silencing and externalized self-perceptions are pathways by which Black women’s obligation to exude strength results in depressive symptomology. Researchers and practitioners may use the findings presented herein to inform and improve mental health interventions and services offered to Black women. Integrating a Womanist theoretical perspective into counseling approaches for Black women and recognizing strength as an asset, along with its hidden liabilities, has the potential to increase the number of Black women who receive needed mental health support.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: Research reported in this manuscript was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5F31HL122118-02) and the National Institute of Mental Health ( R25MH087217) of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.”

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Research Involving Human Subjects: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Virginia Commonwealth University and was conducted ethically according to the approved protocol.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Contributor Information

Jasmine A. Abrams, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Ashley Hill, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Morgan Maxwell, University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

References

- Abrams JA, Maxwell M, Pope M, & Belgrave FZ (2014). Carrying the world with the grace of a lady and the grit of a warrior: Deepening our understanding of the “strong Black woman” schema. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(4), 503–518. 10.1177/0361684314541418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Counseling Association. (2014). Code of ethics.

- American Psychological Association. (2016). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/ethics-code-2017.pdf

- Banks J, & Xu J (2013). Self-silencing as a predictor of physical activity behavior. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34(7), 505–513. 10.3109/01612840.2013.774076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant T (2009). Behind the mask of the strong Black woman: Voice and the embodiment of a costly performance. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 10.1177/0094306110380384d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beblo T, Fernando S, Klocke S, Griepenstroh J, Aschenbrenner S, & Driessen M (2012). Increased suppression of negative and positive emotions in major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 141(2), 474–479. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88(4), 354–364. 10.1037//0033-295x.88.4.354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody DJ, Pratt LA, Hughes JP, & National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.). (2018). Prevalence of depression among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 2013–2016. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29638213 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote N, Beach S, Battista D, & Reynolds C (2010). Depression stigma, race, and treatment seeking behavior and attitudes. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(3), 350–368. 10.1002/jcop.20368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis TE, & Comas-Díaz LE (2016). Womanist and mujerista psychologies: Voices of fire, acts of courage. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. (2016). Summary health statistics: National Health Interview Survey: 2014. Table A-7. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs/tables.htm

- Cole ER (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64, 170–180. 10.1037/a0014564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P (2005). Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. New York, NY: Routledge. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danquah MN (1998). Willow weep for me: A Black woman’s journey through depression. New York, NY: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan RA, & West LM (2015). Stress and mental health: Moderating role of the strong Black woman stereotype. Journal of Black Psychology, 41(4), 384–396. 10.1177/0095798417732414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, & Smith TB (2006). Culturally adapted mental health interventions: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43, 531–548. 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington EF, Crowther JH, & Shipherd JC, (2010). Trauma, binge eating, and the “strong Black woman.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 469–479. 10.1037/a0019174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Lacewell M (2001). No place to rest: African American political attitudes and the myth of Black women’s strength. Women and Politics, 23, 1–34. 10.1080/1554477x.2001.9970965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins MAW, Miller DK, & Stewart JC (2015). A 9-year, bidirectional prospective analysis of depressive symptoms and adiposity: The African American Health Study. Obesity, 23(1), 192–199. 10.1002/oby.20893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/

- Jack DC (2011). Reflections on the Silencing the Self Scale and its origins. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(3), 523–529. 10.1177/0361684311414824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jack DC, & Ali A (2010). Silencing the self across cultures: Depression and gender in the social world. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jack DC, Ali A, & Dias S (2014). Depression in multicultural populations In Leong FTL, Comas-Díaz L, Nagayama Hall GC, McLoyd VC, & Trimble JE (Eds.), APA handbook of multicultural psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267–287). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 10.1037/14187-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jack DC, & Dill D (1992). The Silencing the Self Scale: Schemas of intimacy associated with depression in women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 16(1), 97–106. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1992.tb00242.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C, & Shorter-Gooden K (2003). Shifting: The double lives of Black women in America. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Mendenhall R, Harwood SA, & Huntt MB (2013). Coping with gendered racial microaggressions among Black women college students. Journal of African American Studies, 17(1), 51–73. 10.1007/s12111-012-9219-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay-Dennis L (2015). Black feminist-womanist research paradigm: Toward a culturally relevant research model focused on African American girls. Journal of Black Studies, 46(5), 506–520. 10.1177/0021934715583664 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld A, Harrison MJ, Stewart M, & Hughes K (2008). Advocacy of women family caregivers: Response to nonsupportive interactions with professionals. Qualitative Health Research, 18, 301–310. 10.1177/1049732307313768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero RE (2000). The icon of the strong Black woman: The paradox of strength In Jackson LC & Greene B (Eds.), Psychotherapy with African American women: Innovations in psychodynamic perspectives and practice (pp. 225–238). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Hucles JV (2016). Womanist therapy with Black women In Bryant-Davis T & Comas-Díaz L (Eds.), Womanist and mujerista psychologies: Voices of fire, acts of courage (pp. 69–92). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; http://dx.doi.org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.1037/14937-004 [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG & Fidell LS, (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Witherspoon KM, & Speight SL (2004). Toward the development of the stereotypic roles for Black Women Scale. Journal of Black Psychology, 30(3), 426–442. 10.1177/0095798404266061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E, & Brown RL (2015). A culturally adapted depression intervention for African American Adults experiencing depression: Oh happy day. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(1), 11–22. 10.1037/ort0000027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward EC, & Heidrich SM (2009). African American women’s beliefs about mental illness, stigma, and preferred coping behaviors. Research in Nursing & Health, 32(5), 480–492. 10.1002/nur.20344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson NN, & Hunter CD (2015). Anxiety and depression among African American women: The costs of strength and negative attitudes toward psychological help-seeking. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(4), 604–612. 10.1037/cdp0000015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson-Singleton N (2017). Strong Black woman schema and psychological distress: The mediating role of perceived emotional support. Journal of Black Psychology, 43(8), 778–788. 10.1177/0095798417732414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé CL (2010). Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qualitative Health Research, 20, 668–683. 10.1177/1049732310361892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]