Abstract

Interleukin (IL)-21 is a member of the γ chain-receptor cytokine family along with IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15. The effects of IL-21 are pleiotropic, owing to the broad cellular distribution of the IL-21 receptor. IL-21 is secreted by activated CD4 T cells and natural killer T cells. Within CD4 T cells, its secretion is restricted mainly to T follicular helper (Tfh) cells and Th17 cells to a lesser extent. Our research focus has been on the role of IL-21 and more recently of Tfh in immunopathogenesis of HIV infection. This review focuses on first the influence of IL-21 in regulation of T cell, B cell, and NK cell responses and its immunotherapeutic potential in viral infections and as a vaccine adjuvant. Second, we discuss the pivotal role of Tfh in generation of antibody responses in HIV-infected persons in studies using influenza vaccines as a probe. Lastly, we review data supporting ability of HIV to infect Tfh and the role of these cells as reservoirs for HIV and their contribution to viral persistence.

Keywords: IL-21 and T cells, Tfh cells, IL-21 and B cells, HIV persistence, HIV and IL-21, IL-21 and immunity

Introduction

Interleukin-21 (IL-21) belongs to the family common γ chain (γc) cytokines that include IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15, all of which utilize the γc (CD132) in their receptor complexes for regulating multiple innate and adaptive immune responses. IL-21 is produced by CD4 T cells, in particular T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, T helper 17 (Th17) cells, and also by natural killer T cells [1–4], and by CD8 T cells under certain conditions [5, 6]. The IL-21 receptor (IL-21R) is a heterodimer composed of the common γc and the unique IL-21R, and is expressed on a broad range of lymphoid tissues including spleen, thymus, and lymph nodes [2, 7, 8], and less often in cells from lung and small intestine. In lymphocytes, IL-21R is constitutively expressed on T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells with the highest expression on B cells. T cells express low levels of IL-21R that increase upon T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation. Constitutive expression of IL-21R has been reported on dendritic cells (DC), macrophages, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells [9–12]. This wide range of expression of IL-21R explains the pleiotropic effect of IL-21 in the regulation of immune response. The binding of IL-21 to its receptor leads to the activation of the Janus kinase family proteins (JAK) 1 and 3. Downstream of JAK recruitment, IL-21 mainly activates signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3, and to a weaker and more transient degree, STAT1, STAT4, and STAT5 leading to the activation of Akt and MAPK pathways [8, 13].

Based on their immunomodulatory properties, several γc cytokines, notably IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21 have been investigated in the context of acute and chronic phases of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection [14–24]. For example, administration of rIL-7 to uninfected or SIV-infected Rhesus macaques (RM) demonstrated alterations in T cell homeostasis [20–22] with no effect on SIV replication [22]. In a recent study, IL-7 administered during the acute phase of SIV infection was found to be effective in preventing decline of circulating na¨ıve and memory CD4 T cells [25]. In humans, IL-7 therapy has shown promise for immune reconstitution [26–29]. Administration of rIL-15 to healthy RM was found to increase the frequency of long-lived effector memory CD4 and CD8 T cells [17]. In chronically SIV-infected RM, rIL-15 augmented effector memory CD8 T cells without reduction in viral replication in chronic infection [18, 19], whereas in acute SIV infection, rIL-15 administration resulted in increased peak viremia, which was attributed to increased CD4 T cell activation and proliferation [30]. We chose to study IL-21 in the context of HIV/SIV infection because of its wide range of target cells, its interesting effects in clinical trials in certain human cancers [31, 32], and because it was known to be produced by CD4 T cells, the main cellular target of HIV infection.

IL-21 and modulation of T cells and NK cell cytotoxic properties in HIV infection

Our group was the first to initiate research with IL-21 in the HIV/AIDS field [33]. Based on the T cell-potentiating properties of IL-21 that had been described in tumor models [31, 32], we hypothesized that IL-21 could augment the effector function of CD8 T cells in patients with HIV infection. We found that indeed ex vivo treatment of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with IL-21 resulted in augmented cytotoxic properties of CD8 T cells of HIV-infected patients with HIV RNA of \ 50 copies/mL and CD4 counts > 200 cells/mm3 [33]. Cytotoxic molecules such as perforin and granzyme B were upregulated in memory and effector CD8 T cell subsets and in HIV gag antigen-specific CD8 T cells. Unlike other γc cytokines like IL-15 or IL-2, treatment with IL-21 resulted in selective increase in cytotoxic molecules in CD8 T cells without driving their proliferation or degranulation.

To further understand the mechanisms by which IL-21 increases the cytotoxic molecules on CD8 T cells in HIV infected patients and modulates their cytotoxic potential, we performed in vitro studies using CD8 T cells from healthy volunteers that were pre-activated via T cell receptor signals to mimic their heightened state of immune activation in HIV-infected patients [34]. We found that IL-21 upregulates the cytotoxic effector function and the expression of the costimulatory molecule CD28 on CD8 T cells. The acquisition of cytotoxic molecules in IL-21-treated CD8 T cells was accompanied by sustained expression of surface markers characteristic of memory T cells (i.e., CD27, CD28, and CD127). By gene expression analysis, we further showed that IL-2 and IL-21 operate different transcriptional regulation of perforin and granzyme B induction in CD8 T cells; IL-2 orchestrated the expression of cytotoxic effector genes RUNX3 and EOMES, while IL-21 only induced EOMES [34]. Furthermore, although IL-21 and IL-2 induced mRNA expression of GZMB and PRF1 equally, IL-21 promoted higher accumulation of granzyme B and perforin at the protein level, suggestive of a post-transcriptional regulation mechanism, perhaps similar to that described for perforin expression by NK cells [35]. We also found that CD8 T cells treated with IL-21 ex vivo displayed augmented antiviral activity comparable to that induced by IL-2, but unlike IL-2 it did not induce HIV-1 replication in vitro in CD4 T cells [34].

HIV replication requires CD4 T cell activation. For a molecule to be considered for immunotherapy, it is important to demonstrate that it does not enhance viral replication. Modulation of cytotoxic molecules without induction of generalized cellular activation by IL-21 provided a rationale for investigating immunotherapeutic properties of IL-21. Our results have been confirmed and expanded by several other studies, showing the importance of IL-21 in induction, maintenance, survival, and cytotoxicity of CTL during HIV infection [6, 36–38]. Collectively, these studies favor the concept that IL-21 can modulate the phenotypic and enhance antiviral properties of CD8 T cells that may be impaired during HIV-1 infection. A cytokine that has been used as an adjuvant in many vaccine trials is IL-12 [39–43] and has been tested for its immunomodulatory benefits during chronic SIV infection [44, 45]. IL-12 is a potent inducer of IL-21 [46–48], and it is possible that some beneficial effects of IL-12 can be mediated in part indirectly by the induction of IL-21 [47].

In addition to CD8 T cells, we found that cytotoxic properties of human NK cells were also profoundly influenced by exposure to IL-21 ex vivo. NK cells are important components of the innate arm of the immune response and have been shown to mediate cytotoxic activity against infected CD4 T cells in very early stages of HIV infection [49, 50]. These cells express IL-21R and can be influenced by in vitro exposure to IL-21 [51]. IL-21R is equally expressed on all NK cell subsets, as defined by the differential expression of CD16 and CD56. We analyzed the effects of IL-21 on resting peripheral blood NK cells in chronically HIV-infected individuals. We studied the in vitro effects of IL-21 on perforin expression, proliferation, degranulation, IFN-γ production, cytotoxicity, and induction of STAT phosphorylation in NK cells [51]. Our data indicated that the CD56dim subset of NK cells, which is preferentially dependent upon IL-21, is reduced during HIV infection. Ex vivo treatment with IL-21 enhanced the responses of NK cells from HIV-infected subjects by stimulating perforin production in a STAT3-dependent manner. IL-21 could also enhance HIV-specific antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, secretory, and cytotoxic functions, as well as the viability of NK cells from HIV-infected persons [38]. IL-21-activated NK cells were found to inhibit viral replication when co-cultured with HIV-infected autologous CD4 T cells in a perforin-dependent manner [38]. IL-21 activates STAT3, MAPK, and Akt to enhance NK cell functions [38, 51]. Together, these studies of immunomodulatory properties of IL-21 resulting in augmentation of virus-specific CD8 T cells and NK effector functions in chronically HIV-infected individuals point to the potential utility of IL-21 for immunotherapy or as a vaccine adjuvant.

IL-21 as an immunotherapeutic agent: administration of IL-21 in vivo

The therapeutic utility of IL-21 has been currently investigated in a number of malignant disorders and in viral infections (reviewed in [52–55]). In human clinical trials, therapeutic benefits of IL-21 have been reported in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, metastatic melanoma, and relapsed/refractory indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, with demonstrable antitumor activity (reviewed by Hashmi and Van Veldhuizen [56]). In phase I and phase IIa studies in patients with metastatic melanoma, administration of IL-21 was well tolerated and resulted in increases in CD8 T cells and NK cells expressing mRNA for IFN-γ, perforin, and granzyme B [57–60]. Role of IL-21 in regulating the immune responses has been reported in both acute [61–64] and chronic [65–68] viral infections in mice and also in chronic hepatitis B and C virus infections [69–77] in humans.

Our group investigated the effects of IL-21 administration to SIV-infected rhesus macaques. To evaluate safety, biological activity, and immunomodulatory effects of IL-21, we conducted a pilot study of recombinant mamuIL-21 (rMamuIL-21) administration in chronically SIV-infected RM [24]. IL-21 was well tolerated up to the highest dose of 100 μg/kg body weight, and enhanced the expression of cytotoxic molecules perforin and granzyme B in T cells and NK cells within 48 h. After each dose of IL-21, increases were noted in frequency and median fluorescence intensity of granzyme B and perforin expression in memory and effector subsets of CD8 T cells in peripheral blood, in peripheral and mesenteric lymph node cells, and in peripheral blood memory and effector CD4 T cells. Consistent with our prior observation in IL-21 treated cells of HIV-infected individuals [33], administration of IL-21 to SIV-infected RM did not induce T cell activation, proliferation, or increase the levels of plasma virus load [24]. In addition to augmentation of cytotoxic molecules in CD8 T cells, we also noted an increase in memory B cells and SIV-specific Ab response in IL-21-treated animals. Thus, this first in vivo IL-21 study in chronically SIV-infected animals provided evidence that IL-21 could modulate the immune responses in chronic SIV infection without having any adverse effect on the markers of disease progression.

To analyze the effect of IL-21 during the early stages of SIV infection, we conducted another study in which IL-21 was administered during acute SIV infection [23]. We infected 12 RM with SIV-mac239, and at day 14 postinfection, six of the animals were treated with five weekly subcutaneous doses of 50 μg/kg rhesus rIL-21-IgFc, which represents a dosage similar or lower to that tested in phase I and II clinical trials in humans. Thus, IL-21 treatment was safe and did not increase plasma viral load or result in systemic immune activation. Consistent with our observation in chronic SIV-infected animals [24], acutely infected RM showed higher expression of perforin and granzyme B in total and SIV-specific CD8 T cells with IL-21 treatment in comparison with untreated animals. IL-21 treatment increased the levels of intestinal Th17 cells along with reduced levels of intestinal T cell proliferation, microbial translocation, and systemic activation/inflammation in the chronic phase of SIV infection without T cell exhaustion or undesirable effects on viral load [23]. In addition, IL-21 also increased the frequencies of memory B cells. Results of this study are significant for HIV immunopathogenesis research, as any immunotherapeutic modality that preserves Th17 cells in the gut mucosa can potentially minimize gut microbial translocation and ultimately prevent immune activation and disease progression. Overall, our data demonstrate that IL-21 treatment in SIV-infected RM can improve mucosal immune function through enhanced preservation of Th17 cells. However, further studies are needed to extend this observation to see whether IL-21 given prior to SIV infection can modulate the course of acute SIV infection and whether it can be used as a suitable adjuvant in vaccines to bolster cellular and humoral immunity.

T follicular helper (Tfh) cells and IL-21 in humoral immune responses

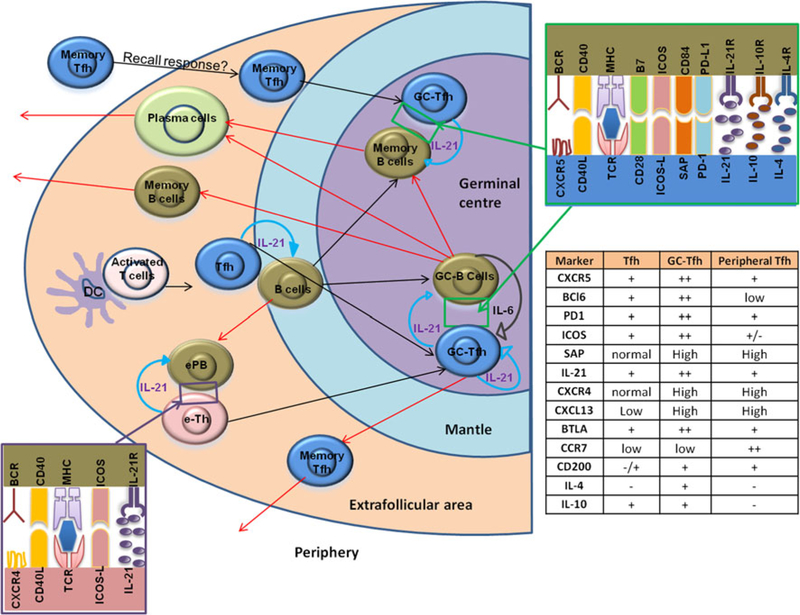

Several investigators have performed extensive studies to elucidate T-B cell intercation in lymph nodes that leads to antibody responses. Germinal centers (GC) are sites within lymphoid follicles in secondary lymphoid organs that are critical for the generation of T-dependent antibody responses mediated via cooperative interaction between resident B cells and Tfh cells (reviewed in [78, 79]). Tfh cells in GC are characterized by the high expression of the transcriptional regulator Bcl-6, surface expression of follicular homing receptor CXC chemokine receptor (CXCR)5, and co-stimulatory molecules like ICOS, CD40L, and PD-1, with secretion of their signature cytokine, IL-21 [80–83]. Upon receiving cognate T cell help, B cells might undergo three potential fates. They can differentiate into an extrafollicular focus of antibody-secreting plasmablasts, or form a GC within the B cell follicle, or differentiate into early recirculating memory B cells [84–86]. As shown in Fig. 1, early humoral immune responses occur in extrafollicular areas of lymphoid tissues where B cells differentiate into short-lived extrafollicular plasmablasts (ePB). Following interactions with extrafollicular helper T cells (eTh), ePB produce low-affinity antibodies that are predominantly short-lived. Similar to Tfh cells, the function of eTh is mediated by CD40L, ICOS, and IL-21 and they do not express high levels of CXCR5 [87, 88]; rather, they show higher CXCR4 expression [89]. eTh cells might also give rise to GC Tfh cells following interactions with cognate B cells [90]. However, the quality of the immune responses is different between these two pathways. With the help of extrafollicular Th cells, ePB produce low-affinity antibodies that are predominantly short-lived, whereas the end product of immune response after a GCs reaction is the production of high-affinity Abs along with the generation long-lived PCs and memory B cells with antigen affinity. During GC reaction, antigen-activated Tfh cells interact with antigen-primed B cells via unique surface molecules that regulate Tfh differentiation and function and through the production of cytokine IL-21 (Fig. 1). Although the importance of Tfh cells for B cell differentiation and function was initially described for Tfh cells residing within GC, the role of Tfh B cell interaction in the T cell zone–B cell zone border of the GC is also under scrutiny [91–93].

Fig. 1.

Tfh cells and IL-21 secreted by Tfh cells coordinate the follicular and extrafollicular immune responses: DC-primed T cells get activated, upregulate Bcl6, and CXCR5, and migrate toward the B cell follicle. Activated T cells then interact with antigen-activated B cell and further undergo differentiation and maturation, and secrete IL-21. IL-21 then initiates an autocrine loop that promotes Tfh cell development. Early events in the development of humoral immune responses occur in extrafollicular areas of lymphoid tissues where B cells differentiate into short-lived extrafollicular plasmablasts (ePB). Following interactions with extrafollicular helper T cells (eTh) cells, ePB produces low-affinity antibodies that are predominantly short-lived. Similar to Tfh cells, the function of eTh is mediated by CD40L, ICOS, and IL-21 and they do not express high levels of CXCR5; rather, they show higher CXCR4 expression. eTh cells might also give rise to GC Tfh cells following interactions with cognate B cells. Alternatively, both T and B cells migrate to the GC where Tfh cells reach their fully differentiate and produce high levels of IL-21. In the GC, Tfh cells interact with GC B cells through an array of molecular pairings, including pairings of T cell antigen receptor (TCR) and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II; CD28 and B7 family members; the costimulatory molecule CD40 and its ligand CD40L; ICOS and its ligand ICOSL; SLAM family members on both cell types; and PD-1 and PD-L1. These interactions further enhance the production of IL-21 and the IL-21 produced by Tfh cells helps in the maintenance and persistence of Tfh cell phenotype, function, and is a major B cell helper cytokine to induce B cell class switching and for antibody diversification mechanisms. After the completion of the GC reaction, long-lived plasma cells (PC) and memory B cells and antigen-specific memory Tfh cells exit the follicular region and enter the circulation. Memory Tfh cells could reenter to the GC and induce GC reaction during a secondary immune response [90]

Association of IL-21 in the regulation of Tfh cell differentiation was first identified by microarray profiling of human Tfh cells [94]. Experiments using IL-21 reporter mice have shown that among Tfh cells, about one-third of the population express IL-21 in the context of a T cell-dependent immunization [95]. IL-21 can also induce c-Maf, thus providing a positive self-regulatory loop that maintains IL-21 expression in Tfh cells [96]. In addition, IL-21 can induce Bcl6 expression in Tfh cells [4, 97]. Expressions of Bcl6 and cMaf on Tfh cells are important for the induction of migration genes of Tfh cells that control homing to the lymph nodes, namely CXCR4, CXCR5, CC-chemokine receptor (CCR)7, and genes that are involved in T–B interactions including CD40L, ICOS, CXC chemokine ligand (CXCL)13, the SLAM-associated protein (SAP), and programmed death (PD)-1 receptor [98].

Tfh-derived IL-21 orchestrates many aspects of B cell differentiation and function, GC development and maintenance, and development of memory B cells and plasma cells (PC) [81, 87, 93, 99]. Within GC, IL-21 promotes persistence of GC B cells through the upregulation of Bcl6 in GC B cells [81, 87]. In GC, IL-21 is important in developing and maintaining the GC reaction by regulating Bcl6 expression on both B cells and Tfh cells [81, 97, 100]. IL-21 plays an important role in vaccine-induced humoral immune responses by regulating B cell function. IL-21 is capable of inducing B cell proliferation, differentiation, class switching or death, depending upon the type of antigenic stimulation and accessory signals [7, 101], making the IL-21-elicited signaling the most important among all the γc cytokines for long-lived humoral immunity [83, 102]. Na¨ıve human B cells are efficiently induced to secrete immunoglobulin via IL-21 following cognate T–B interaction [103, 104]. Recently, expression of the IL-21R on B cells was shown to be critical for the development of memory B cells [105]. IL-21-elicited STAT3 activation induces B cell maturation with the expression of PC-associated genes, phenotypic PC formation, and antibody secretion [87, 103, 106–109]. In experiments conducted ex vivo, IL-21 is capable of driving PC differentiation and IgM, IgG, and IgA antibody production from human splenic GC B cells, [108]. Consistent with these observations, the importance of IL-21 in developing humoral immune responses has been reported in humans with severe combined immunodeficiency [83].

HIV infection significantly alters several aspects of distribution of B cell subsets and B cell function, resulting from excessive B cell activation and impaired survival (reviewed in [110–113]). Following the initiation of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), most of the B cell phenotypic alterations revert back to normal but the CD27+ resting memory B cells remain significantly decreased in comparison with healthy uninfected donors, despite virologic control and CD4 T cell recovery [114, 115]. In a study by Van Grevenynghe et al., lower memory B cell survival from HIV-infected subjects was attributed to disrupted IL-2 and IL-21 signaling leading to increased Foxo3a transcriptional activity and increased expression of its pro-apoptotic target TRAIL [111]; results from this study support the concept that IL-21 could rescue the memory B cell from apoptosis in HIV-infected people and thereby benefit the overall humoral immune responses by supporting the persistence and survival of memory B cells during HIV infection [116, 117]. The fact that IL-21 production is mainly stimulated by the activation of Tfh cells, it is important to determine whether the B cell defects in HIV-infected patients are secondary to a deficiency in the CD4 Tfh cell compartment and if it can be reversed by IL-21.

Peripheral Tfh cells (pTfh)

The fate of the GC Tfh after their interaction with B cells is not known. Although widely believed that they undergo apoptosis in the GC, recent data suggest that they are capable of exiting the GC to generate a heightened memory cell response [118, 119]. Persistence of Tfh cells within the lymph nodes several weeks after immunization has been reported [118]. However, as antigen persisted in this model, it was not clear whether those cells were true memory cells. Later studies conclusively demonstrated the generation of memory Tfh cells after GC reaction [120, 121].

It was recently demonstrated that human peripheral CXCR5+ memory CD4 T cells share functional properties with the GC Tfh cells [122–127], such as the ability to secrete IL-21 and to induce autologous na¨ıve and memory B cell subsets to produce immunoglobulins [104, 128]. We observed that the pTfh cells displayed a memory phenotype with the characteristics of central memory cells [128]. Marshall et al. also observed that a subset of memory cells with similar phenotypic features as Tfh cells existed within the memory cell pool, and these CXCR5+memory cells enhance the kinetics of B cell expansion and class switching, and suggested that such CXCR5 expression on memory cells promotes migration to areas where encounter with cognate B cells can occur following reintroduction of antigen [129, 130]. Notably, these peripheral CXCR5+ CD4 T cells are absent in circulation of patients with ICOS deficiency [131] who also lack GC.

In HIV infection, a recent study has identified a resting memory subpopulation of circulating memory PD-1+CXCR5+CD4+Tcells to be most closely related to bona fide GC Tfh cells by gene expression profile, cytokine profile, and functional properties [132], and also demonstrated that frequencies of PD1+CXCR5+CXCR3negpTfh cells directly correlated with broad neutralizing Ab development. We have noted that in HIV infected treatment naive patients, 12 months of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) incorporating raltegravir was highly effective in CD4 T cell immune reconstitution [133]. These patients manifested increase in central memory CD4 T cells and pTfh cells as well as IL-21 producing CD4 T cells after phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) + Ionomicin stimulation implying improved pTfh function. In well-controlled HIV infection, pTfh frequency was found to be equivalent in patients and healthy controls (HCs) [128]. We have investigated pTfh and their relationship to serologic responses to influenza vaccination in HIV-1-infected patients [128].

HIV infection and B cell responses: role of IL-21 and pTfh

We have utilized influenza vaccination as a probe to investigate the immune competence of pTfh cells and B cells in HIV infection. We started these studies at the time of the 2009/H1N1 pandemic influenza outbreak [128, 134, 135] in virally suppressed HIV-infected adults on combination ART and healthy controls of similar age and with similar frequencies of B cells. Blood was drawn at pre-, 1, and 4 weeks post-vaccination. At 4 weeks post-vaccination, only 50 % patients were classified as vaccine responders based on Ab titers of > 1:40 and > 4-fold increase in Ab titers, whereas 100 % of healthy controls were responders. Pre-vaccination CD4 and CD8 T cell counts and plasma HIV RNA were not different between the responder and non-responder patients. Characteristic immunologic findings related to vaccine responses in this cohort [128, 134, 135] are summarized in Table 1. The upregulation of IL-21/IL-21R in B cells and CD4 T cells in the vaccine responders corresponded with development of plasmablasts and memory B cells suggesting that responsiveness to IL-21 was important for the Ab response. Patients who did not respond to the H1N1/09 vaccine failed to develop these vaccine-induced characteristic B cells changes.

Table 1.

Signature immunologic changes in pTfh and B cells in vaccine responders (VR) following influenza vaccine at T1 (7 days), T2 (4 week) [128, 134, 135, 142]

| pTfh cell changes in VR (not seen in non-pTfh or VNR) |

| Expansion of pTfh at T1 and T2 |

| Ag-stimulated IL-21 production in pTfh (ICC) |

| “Help” to autologous B cells for Ag-specific IgG production and B cell differentiation in purified pTh plus B cell co-cultures at T2 |

| B cell changes in VR (deficient in VNR) |

| Increase in plasmablasts at T1 |

| Spontaneous H1N1 influenza Ab-secreting cells (ASC) at T1 |

| Increase in total memory B cells and switch memory at T2 |

| Upregulation of IL-21R on total B and memory B cells at T2 |

| Increase in plasma cells at T2 |

| Increase in TACI expression on total B memory B cells at T2 |

| Downregulation of BAFF-R expression on total B and memory B cells at T2 |

| PBMC/plasma findings in VR (deficient in VNR) |

| Production of IL-21 and CXCL13 in Ag-stimulated culture supernatants with increases in plasma IL-21 |

| Increase in plasma BAFF and APRIL levels |

VR vaccine responders, VNR vaccine non-responders, pTfh peripheral T follicular helper cells, ICC intracellular cytokine staining, PBMC peripheral blood mononuclear cells, Ab antibody

In vaccine responders, pTfh cells underwent expansion with secretion of IL-21 and CXCL13 in H1N1-stimulated PBMC culture supernatants at week 4 (T2) post-vaccination. These changes were not seen in vaccine non-responders. In purified pTfh and B cell co-culture experiments, pTfh cells supported HIN1Ag-stimulated IgG production by autologous B cells only in vaccine responders. At T2, frequencies of pTfh were correlated with memory B cells, serum H1N1 Ab titers, and Ag-induced IL-21 secretion. Our results showed for the first time a role of pTfh cells in inducing vaccine-induced immune response and indicate that the expansion of pTfh could be considered as a biomarker for ensuing immune response following vaccination. Consistent with our findings, a later study by Bentebibel and colleagues found that a small population of activated ICOS+CXCR3+CXCR5+ cells transiently appear in human blood after influenza vaccination and that these cells correlate with influenza antibody titers [136] Importantly, as mentioned earlier, a recent study indicates that the frequency of pTfh correlated with the development of bnAbs against HIV in a large cohort of HIV infected individuals [132]. Taken together, these studies support the concept that Tfh cells exist as memory cells in the periphery. As pTfh cells are easily accessible from peripheral blood their utility as surrogate Tfh biomarkers needs to be investigated. Our data support the concept that pTfh cells could be used as a tool for studying the relationship between Tfh and B cells in generation of immune responses. Studies using lymph node Tfh and peripheral blood Tfh cells pre- and post-immunization are needed to conclusively establish the relationship of pTfh with lymph node Tfh with respect to an ongoing immune response. The molecular signatures of these cell subsets from the two sites during an immune response also need to be investigated in order to understand their precise functional relationship.

IL-21 and pTfh cells in aging

The major reason underlying the susceptibility to infection and for poor vaccine responses in both the HIV uninfected elderly and HIV infected of all ages is the decline of or impairment in functioning of the immune system, often termed as immunosenescence [137, 138]. Advances in antiretroviral therapy have dramatically increased the life expectancy of HIV infected persons up to ≥ 70 years [139], and incidence of new HIV infections at older ages has also increased. It is estimated that by 2015, 50 % of HIV infected population will be ≥ 50 years of age [140]. Given the independent detrimental effects of aging and of HIV infection on the immune system, research into cumulative immune decline with HIV and aging has taken on increasing significance.

We have expanded our research focus to study the effect of aging on immune responses in HIV infected individuals. To address the relationship between aging and HIV infection, we first studied the distribution of factors contributing to the HIV disease progression in young and older HIV-infected individuals [141]. In this study, we investigated immune activation and microbial translocation in HIV infected aging women in postmenopausal ages. Twenty-seven postmenopausal women with HIV infection receiving cART with documented viral suppression and 15 HIV-negative age-matched controls were included in this study. Levels of immune activation markers (T cell immune phenotype, sCD25, sCD14, sCD163), microbial translocation (lipopolysaccharide), and biomarkers of cardiovascular disease and impaired cognitive function (sVCAM-1, sICAM-1, and CXCL10) were evaluated. Our results indicate that T cell activation and exhaustion, monocyte/macrophage activation, and microbial translocation were significantly higher in HIV-infected women when compared to uninfected controls [141]. Microbial translocation correlated with T cell and monocyte/macrophage activation. Biomarkers of cardiovascular disease and impaired cognition were elevated in women with HIV infection and correlated with immune activation. Our data indicate that HIV-infected antiretroviral-treated aging women who achieved viral suppression are in a generalized state of immune activation and therefore are at an increased risk of age-associated end-organ diseases compared to uninfected age-matched controls.

We investigated whether the age-associated changes in combination with the factors affecting HIV disease progression might also negatively impact the immune function in HIV infected older patients. To address this issue, preliminary studies were conducted in which immune response after influenza vaccination was measured in these HIV-infected postmenopausal women and compared with healthy HIV-negative postmenopausal volunteers [142]. Antibody titers to trivalent influenza vaccination given during the 2011–2012 season were determined before and 4 weeks after vaccination. Our results showed reduced seroprotective influenza antibody titers (≥ 1:40) in HIV infected women compared to HIV uninfected women (31 vs. 58 %, respectively) pre-vaccination. Following vaccination, magnitude of antibody responses and frequency of seroprotection were lower in HIV infected (75 %) than in HIV uninfected (91 %) women [142]. Seroconversion was associated with an increase in plasma IL-21, the signature cytokine of Tfh cells. A novel observation in this study was that post-vaccine antibody responses were inversely correlated with pre-vaccination plasma TNFα levels and with markers of immune activation (CD38 and HLA-DR) on CD4 T cells, including pTfh subset, indicating detrimental consequences of immune activation and inflammation on vaccine-induced antibody response in older age. Plasma TNFα levels were found to correlate with activated pTfh cells, and inversely with the post-vaccination levels of plasma IL-21. Higher frequencies of activated and exhausted CD8 T and B cells were noted in HIV infected women [142]. Our results indicate that in aging, activated CD4 and pTfh cells may compromise influenza vaccine-induced antibody response, for which a mechanism of TNFα-mediated impairment of pTfh-induced IL-21 secretion is postulated. It is hypothesized that interventions aimed at reducing chronic inflammation and immune activation may improve response to vaccines [142]. We are now conducting a larger study of influenza vaccination in different age groups to investigate the molecular and immunologic mechanisms that could explain the defect in aging-associated immune response and to understand the effect of HIV on aging. Studies in SIV-infected aged Rhesus macaques are needed to understand the immune responses in inductive sites such as GC following vaccination. The question whether IL-21 supplementation or cellular therapy using in vitro expanded Tfh cells could improve the immune responses after vaccination needs to be investigated.

pTfh cells and HIV reservoirs

In addition to its role in regulating the immune responses, recent studies have ascribed an important role of Tfh cells in the LN in contributing to HIV persistence and reservoirs. In SIV infection models of Rhesus macaques and pig tail macaques, studies have clearly demonstrated that Tfh cells within LNs are highly susceptible to SIV infection [77, 143, 144] and suggest that Tfh cells have relevance for assessing the size of the viral reservoir [143]. Within weeks of SIV inoculation, these cells are often maintained or expanded in frequency and spatial localization within B cell follicles [77, 143]. Early infection of Tfh cells represents an unexpected focus of viral infection. However, infection of Tfh cells does not interrupt antibody production but may be a factor that limits the quality of antibody responses.

Consistent with the findings in macaques, susceptibility of LN Tfh cells and HIV infection in human has been reported recently [145]. This study showed that both Tfh (CXCR5+PD1+) and CXCR5negPD1+ cell populations are enriched in HIV-specific CD4 T cells, and these populations are significantly expanded in viremic HIV-infected subjects and the percentage of Tfh cells correlated with the levels of plasma viremia. Tfh cell population contained the highest percentage of CD4 T cells harboring HIV DNA and was the most efficient in supporting productive infection in vitro [145]. These studies indicate that Tfh cells could be an important target of HIV, and it was suggested that compared with T cell zones, GCs seemed to exclude CD8 T cells while harboring increasing numbers of virus-specific CD4 T cells, suggesting an environment particularly beneficial for virus replication and reservoirs [146]. Moreover, it has been suggested that reduced tissue penetration of ART in lymph nodes also would favor the persistence of the virus at sites within LNs that could favor Tfh cells as an important cellular subset for HIV persistence and viral reservoirs [147]. In humans, prior studies have identified central memory CD4 T cells (TCM) as a major reservoir for HIV in virally suppressed individuals along with transitional memory (TTM), which is consistent with their capacity to survive for long periods in vivo that makes it ideal for HIV to persist within these cells [148]. A close association of PD1+CXCR5+ Tfh cells with GC Tfh has been reported recently with respect to their gene signatures and helper function of B cells [132]. Moreover, a recent study has shown that PD1+CXCR5+ Tfh cells from lymph nodes of patients with HIV infection contained the highest percentage of HIV infected cells and were the most efficient in supporting virus replication and production, indicating a close association of PD1 with HIV reservoirs in lymph nodes [145]. We are currently investigating the role of pTfh cells in viral persistence and its association with HIV reservoirs. Consistent with the reported data in lymph node Tfh cells, we noted a higher permissiveness of pTfh cells to HIV-1 infection compared to non-pTfh cells and PD1+ pTfh cells showed higher frequencies of virally infected cells (Pallikkuth et al., unpublished). This research is in progress, and we are now identifying the factors that contribute to the higher permissiveness of pTfh cells to HIV and also how ART-induced decrease in virus levels affects the HIV burden on pTfh cells. Overall, our preliminary investigations revealed that in addition to their role in immune responses, pTfh cells could also serve as the major CD4 T cell compartment for HIV infection, replication, and production. Our preliminary results indicate that pTfh cells could be considered as one of the important memory cell subsets that support HIV infection and persistence. Further investigation is needed to clarify the potential utility of pTfh cells as tools for measuring the burden of HIV for HIV persistence and in cure research.

Conclusions and future perspectives

In this review, we have highlighted the favorable properties of IL-21 in modulation of adaptive immune responses in the context of HIV infection in humans and SIV infection in Rhesus macaques. Three major properties of IL-21 are as follows: 1. augmentation of cytotoxic molecules perforin and granzyme B in CTL and NK cells; 2. induction of antibody responses and autocrine regulation; and 3. lack of induction of T cell activation that leads to HIV replication. Our studies in chronic and acute SIV-infected rhesus macaques using IL-21 showed enhancement of cellular immunity without associated immune activation and increase in virus replication [23, 24], indicating a immunomodulatory effect of IL-21 at different stages of SIV infection. In humans, in vitro studies [33, 51] as well as investigations of HIV-infected patients with different disease states including elite controllers have ascribed an important role to IL-21 in preservation of virus control [6, 36, 37, 116, 117]. There is ample support for the beneficial role of IL-21 in other acute and chronic virus infections. Mice models of acute and chronic LCMV infection highlighted the importance of IL-21 in promoting and sustaining immune response during chronic and acute viral infections [65–67]. Immunomodulatory properties of IL-21 have also been described in human hepatitis B and C infections. IL-21 mRNA levels were increased in PBMC of patients with acute infection who cleared the virus compared with patients who did not clear the virus [149]. A study by Ma et al. suggests that serum IL-21 levels may be a biomarker for HBeAg seroconversion during therapy in chronic hepatitis B virus-infected patients, a good prognosis marker of HBV. HBeAg seroconversion coincides with the development of the HBV-specific CD8T cell repertoire that is believed to control viral replication. This study suggests that IL-21 may also have a role in immunotherapy for chronic hepatitis B infection [150].

The recent advances in the field of immunity by understanding the role of GC in regulating the adaptive immune responses further strengthen the cooperative role of IL-21 and Tfh cells in regulating antigen-specific antibody production. In HIV infection, a role for Tfh in HIV Ab responses [132] and importantly in flu vaccine-induced Ab responses [128, 136] has been demonstrated. Together, there is compelling rationale to investigate IL-21 as a vaccine adjuvant to augment T and B cell immune responses and also in immunotherapeutic approaches to enhance CTL for eliminating virally infected target cells in “cure” strategies aimed at achieving permanent virologic control. The lack of an effect of IL-21 on immune activation after in vivo administration in chronic and acute SIV infection indicates that IL-21 has promise in immunotherapeutic approaches in SIV/HIV infection as it does not appear to affect factors that favor disease progression.

Thus far, definitive studies have not been performed that demonstrate the utility of IL-21 either in vaccine design or as a therapeutic moiety in HIV/SIV infection. For example, it is not known whether IL-21 by itself or as a vaccine adjuvant in healthy RM can elicit cellular or humoral immune responses that impact infection status in any way after a virus challenge. IL-21 could potentially promote the generation of high-affinity antibodies during an immune response by modulating signals required for antigen-specific expansion, and differentiation of B cells and Tfh cells. Current data on interaction between Tfh cells, B cells, and IL-21 during a humoral immune response support the notion that IL-21 supplementation could enhance the efficacy of vaccines or immunity against infection in immunocompromised individuals. Current knowledge supports the rationale for continued exploration of the properties of IL-21 in experimental models of HIV/SIV infection in prevention and treatment during early and chronic stages in conjunction with ART and other immunotherapeutic strategies

The studies of pTfh cells point to the potential utility of pTfh as biomarkers of ongoing immune response. Further studies are needed to establish the relationship of pTfh with lymph node Tfh and to determine whether pTfh cells can provide insight into the immune responses at the inductive sites such as GC. Knowledge in this field will open avenues for translational research using IL-21 and Tfh cells and may help in the development of IL-21-based adjuvant or pTfh-based cellular therapies that could potentially be used in understanding HIV immunopathogenesis, in strategies to improve the immune response in situations where it is deeply compromised, and in approaches aimed at “curing” HIV. The role of pTfh as reservoirs for HIV is particularly relevant and in need for further investigation as strategies to eliminate virus from cellular sanctuaries are developed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant A1077501, AI 108472 to SP and a CFAR developmental award to S Palli. We acknowledge support from the Miami Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) at the University Of Miami Miller School Of Medicine, which is funded by a Grant (P30AI073961) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The CFAR program at the NIH includes the following co-funding and participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, FIC, and OAR.

Biography

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Coquet JM, Kyparissoudis K, Pellicci DG, Besra G, Berzins SP, Smyth MJ, et al. IL-21 is produced by NKT cells and modulates NKT cell activation and cytokine production. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2007;178:2827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parrish-Novak J, Dillon SR, Nelson A, Hammond A, Sprecher C, Gross JA, et al. Interleukin 21 and its receptor are involved in NK cell expansion and regulation of lymphocyte function. Nature 2000;408:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei L, Laurence A, Elias KM, O’Shea JJ. IL-21 is produced by Th17 cells and drives IL-17 production in a STAT3-dependent manner. J Biol Chem 2007;282:34605–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, Yang XO, Kang HS, Ma L, et al. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity 2008;29:138–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mittal A, Murugaiyan G, Beynon V, Hu D, Weiner HL. IL-27 induction of IL-21 from human CD8 + T cells induces granzyme B in an autocrine manner. Immunol Cell Biol 2012;90:831–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams LD, Bansal A, Sabbaj S, Heath SL, Song W, Tang J, et al. Interleukin-21-producing HIV-1-specific CD8 T cells are preferentially seen in elite controllers. J Virol 2011;85:2316–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin H, Carrio R, Yu A, Malek TR. Distinct activation signals determine whether IL-21 induces B cell costimulation, growth arrest, or Bim-dependent apoptosis. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2004;173:657–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozaki K, Kikly K, Michalovich D, Young PR, Leonard WJ. Cloning of a type I cytokine receptor most related to the IL-2 receptor beta chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:11439–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandt K, Bulfone-Paus S, Jenckel A, Foster DC, Paus R, Ruckert R. Interleukin-21 inhibits dendritic cell-mediated T cell activation and induction of contact hypersensitivity in vivo. J Invest Dermatol 2003;121:1379–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caruso R, Fina D, Peluso I, Fantini MC, Tosti C, Del Vecchio Blanco G, et al. IL-21 is highly produced in Helicobacter pyloriinfected gastric mucosa and promotes gelatinases synthesis. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2007;178:5957–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monteleone G, Caruso R, Fina D, Peluso I, Gioia V, Stolfi C, et al. Control of matrix metalloproteinase production in human intestinal fibroblasts by interleukin 21. Gut 2006;55:1774–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruckert R, Bulfone-Paus S, Brandt K. Interleukin-21 stimulates antigen uptake, protease activity, survival and induction of CD4 + T cell proliferation by murine macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol 2008;151:487–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asao H, Okuyama C, Kumaki S, Ishii N, Tsuchiya S, Foster D, et al. Cutting edge: the common gamma-chain is an indispensable subunit of the IL-21 receptor complex. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2001;167:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pahwa S Role of common gamma chain utilizing cytokines for immune reconstitution in HIV infection. Immunol Res 2007;38:373–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pallikkuth S, Parmigiani A, Pahwa S. The role of interleukin-21 in HIV infection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2012;23:173–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craiu A, Barouch DH, Zheng XX, Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE, Lifton MA, et al. An IL-2/Ig fusion protein influences CD4 + T lymphocytes in naive and simian immunodeficiency virus-infected Rhesus monkeys. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir 2001;17:873–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villinger F, Miller R, Mori K, Mayne AE, Bostik P, Sundstrom JB, et al. IL-15 is superior to IL-2 in the generation of long-lived antigen specific memory CD4 and CD8 T cells in rhesus macaques. Vaccine 2004;22:3510–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueller YM, Petrovas C, Bojczuk PM, Dimitriou ID, Beer B, Silvera P, et al. Interleukin-15 increases effector memory CD8 + t cells and NK Cells in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Virol 2005;79:4877–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Picker LJ, Reed-Inderbitzin EF, Hagen SI, Edgar JB, Hansen SG, Legasse A, et al. IL-15 induces CD4 effector memory T cell production and tissue emigration in nonhuman primates. J Clin Investig 2006;116:1514–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beq S, Nugeyre MT, Ho Tsong Fang R, Gautier D, Legrand R, Schmitt N, et al. IL-7 induces immunological improvement in SIV-infected rhesus macaques under antiviral therapy. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2006;176:914–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fry TJ, Moniuszko M, Creekmore S, Donohue SJ, Douek DC, Giardina S, et al. IL-7 therapy dramatically alters peripheral T-cell homeostasis in normal and SIV-infected nonhuman primates. Blood 2003;101:2294–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moniuszko M, Edghill-Smith Y, Venzon D, Stevceva L, Nacsa J, Tryniszewska E, et al. Decreased number of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells that express the interleukin-7 receptor in blood and tissues of SIV-infected macaques. Virology 2006;356:188–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pallikkuth S, Micci L, Ende ZS, Iriele RI, Cervasi B, Lawson B, et al. Maintenance of intestinal Th17 cells and reduced microbial translocation in SIV-infected rhesus macaques treated with interleukin (IL)-21. PLoS Pathog 2013;9:e1003471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pallikkuth S, Rogers K, Villinger F, Dosterii M, Vaccari M, Franchini G, et al. Interleukin-21 administration to rhesus macaques chronically infected with simian immunodeficiency virus increases cytotoxic effector molecules in T cells and NK cells and enhances B cell function without increasing immune activation or viral replication. Vaccine 2011;29:9229–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vassena L, Miao H, Cimbro R, Malnati MS, Cassina G, Proschan MA, et al. Treatment with IL-7 prevents the decline of circulating CD4 + T cells during the acute phase of SIV infection in rhesus macaques. PLoS Pathog 2012;8:e1002636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy Y, Lacabaratz C, Weiss L, Viard JP, Goujard C, Lelievre JD, et al. Enhanced T cell recovery in HIV-1-infected adults through IL-7 treatment. J Clin Investig 2009;119:997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sereti I, Dunham RM, Spritzler J, Aga E, Proschan MA, Medvik K, et al. IL-7 administration drives T cell-cycle entry and expansion in HIV-1 infection. Blood 2009;113:6304–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy Y, Sereti I, Tambussi G, Routy JP, Lelievre JD, Delfraissy JF, et al. Effects of recombinant human interleukin 7 on T-cell recovery and thymic output in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy: results of a phase I/IIa randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 2012;55:291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vandergeeten C, Fromentin R, DaFonseca S, Lawani MB, Sereti I, Lederman MM, et al. Interleukin-7 promotes HIV persistence during antiretroviral therapy. Blood 2013;121:4321–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mueller YM, Do DH, Altork SR, Artlett CM, Gracely EJ, Katsetos CD, et al. IL-15 treatment during acute simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection increases viral set point and accelerates disease progression despite the induction of stronger SIV-specific CD8 + T cell responses. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2008;180:350–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moroz A, Eppolito C, Li Q, Tao J, Clegg CH, Shrikant PA. IL-21 enhances and sustains CD8 + T cell responses to achieve durable tumor immunity: comparative evaluation of IL-2, IL-15, and IL-21. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2004;173:900–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Bleakley M, Yee C. IL-21 influences the frequency, phenotype, and affinity of the antigen-specific CD8 T cell response. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2005;175:2261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White L, Krishnan S, Strbo N, Liu H, Kolber MA, Lichtenheld MG, et al. Differential effects of IL-21 and IL-15 on perforin expression, lysosomal degranulation, and proliferation in CD8 T cells of patients with human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV). Blood 2007;109:3873–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parmigiani A, Pallin MF, Schmidtmayerova H, Lichtenheld MG, Pahwa S. Interleukin-21 and cellular activation concurrently induce potent cytotoxic function and promote antiviral activity in human CD8 T cells. Hum Immunol 2011;72:115–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fehniger TA, Cai SF, Cao X, Bredemeyer AJ, Presti RM, French AR, et al. Acquisition of murine NK cell cytotoxicity requires the translation of a pre-existing pool of granzyme B and perforin mRNAs. Immunity 2007;26:798–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chevalier MF, Julg B, Pyo A, Flanders M, Ranasinghe S, Soghoian DZ, et al. HIV-1-specific interleukin-21 + CD4 + T cell responses contribute to durable viral control through the modulation of HIV-specific CD8 + T cell function. J Virol 2011;85:733–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yue FY, Lo C, Sakhdari A, Lee EY, Kovacs CM, Benko E, et al. HIV-specific IL-21 producing CD4 + T cells are induced in acute and chronic progressive HIV infection and are associated with relative viral control. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2010;185:498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iannello A, Boulassel MR, Samarani S, Tremblay C, Toma E, Routy JP, et al. IL-21 enhances NK cell functions and survival in healthy and HIV-infected patients with minimal stimulation of viral replication. J Leukoc Biol 2010;87:857–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Metzger DW. Interleukin-12 as an adjuvant for induction of protective antibody responses. Cytokine 2010;52:102–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalams SA, Parker SD, Elizaga M, Metch B, Edupuganti S, Hural J, et al. Safety and comparative immunogenicity of an HIV-1 DNA vaccine in combination with plasmid interleukin 12 and impact of intramuscular electroporation for delivery. J Infect Dis 2013;208:818–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindsay RW, Ouellette I, Arendt HE, Martinez J, Destefano J, Lopez M, et al. SIV antigen-specific effects on immune responses induced by vaccination with DNA electroporation and plasmid IL-12. Vaccine 2013;31:4749–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naderi M, Saeedi A, Moradi A, Kleshadi M, Zolfaghari MR, Gorji A, et al. Interleukin-12 as a genetic adjuvant enhances hepatitis C virus NS3 DNA vaccine immunogenicity. Virologica Sinica 2013;28:167–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodriguez AM, Pascutti MF, Maeto C, Falivene J, Holgado MP, Turk G, et al. IL-12 and GM-CSF in DNA/MVA immunizations against HIV-1 CRF12_BF Nef induced T-cell responses with an enhanced magnitude, breadth and quality. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e37801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villinger F, Bucur S, Chikkala NF, Brar SS, Bostik P, Mayne AE, et al. In vitro and in vivo responses to interleukin 12 are maintained until the late SIV infection stage but lost during AIDS. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir 2000;16:751–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe N, Sypek JP, Mittler S, Reimann KA, Flores-Villanueva P, Voss G, et al. Administration of recombinant human interleukin 12 to chronically SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir 1998;14:393–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ma CS, Suryani S, Avery DT, Chan A, Nanan R, Santner-Nanan B, et al. Early commitment of naive human CD4(+) T cells to the T follicular helper (T(FH)) cell lineage is induced by IL-12. Immunol Cell Biol 2009;87:590–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nurieva RI, Dong C. (IL-)12 and 21: a new kind of help in the follicles. Immunol Cell Biol 2009;87:577–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmitt N, Morita R, Bourdery L, Bentebibel SE, Zurawski SM, Banchereau J, et al. Human dendritic cells induce the differentiation of interleukin-21-producing T follicular helper-like cells through interleukin-12. Immunity 2009;31:158–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alter G, Altfeld M. NK cells in HIV-1 infection: evidence for their role in the control of HIV-1 infection. J Intern Med 2009;265:29–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tiemessen CT, Shalekoff S, Meddows-Taylor S, Schramm DB, Papathanasopoulos MA, Gray GE, et al. Natural killer cells that respond to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) peptides are associated with control of HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 2010;202:1444–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strbo N, de Armas L, Liu H, Kolber MA, Lichtenheld M, Pahwa S. IL-21 augments natural killer effector functions in chronically HIV-infected individuals. AIDS (London, England) 2008;22:1551–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarra M, Franze E, Pallone F, Monteleone G. Targeting interleukin-21 in inflammatory diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2011;15:695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sondergaard H, Skak K. IL-21: roles in immunopathology and cancer therapy. Tissue Antigens 2009;74:467–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spolski R, Leonard WJ. Interleukin-21: basic biology and implications for cancer and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2008;26:57–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yuan FL, Hu W, Lu WG, Li X, Li JP, Xu RS, et al. Targeting interleukin-21 in rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Biol Rep 2011;38: 1717–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hashmi MH, Van Veldhuizen PJ. Interleukin-21: updated review of Phase I and II clinical trials in metastatic renal cell carcinoma, metastatic melanoma and relapsed/refractory indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2010;10:807–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davis ID, Brady B, Kefford RF, Millward M, Cebon J, Skrumsager BK, et al. Clinical and biological efficacy of recombinant human interleukin-21 in patients with stage IV malignant melanoma without prior treatment: a phase IIa trial. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:2123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis ID, Skrumsager BK, Cebon J, Nicholaou T, Barlow JW, Moller NP, et al. An open-label, two-arm, phase I trial of recombinant human interleukin-21 in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:3630–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frederiksen KS, Lundsgaard D, Freeman JA, Hughes SD, Holm TL, Skrumsager BK, et al. IL-21 induces in vivo immune activation of NK cells and CD8(+) T cells in patients with metastatic melanoma and renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2008;57:1439–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson JA, Curti BD, Redman BG, Bhatia S, Weber JS, Agarwala SS, et al. Phase I study of recombinant interleukin-21 in patients with metastatic melanoma and renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2034–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yi JS, Ingram JT, Zajac AJ. IL-21 deficiency influences CD8 T cell quality and recall responses following an acute viral infection. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2010;185:4835–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Novy P, Huang X, Leonard WJ, Yang Y. Intrinsic IL-21 signaling is critical for CD8 T cell survival and memory formation in response to vaccinia viral infection. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 186:2729–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rasheed MA, Latner DR, Aubert RD, Gourley T, Spolski R, Davis CW, et al. Interleukin-21 is a critical cytokine for the generation of virus-specific long-lived plasma cells. J Virol 2013;87:7737–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karnowski A, Chevrier S, Belz GT, Mount A, Emslie D, D’Costa K, et al. B and T cells collaborate in antiviral responses via IL-6, IL-21, and transcriptional activator and coactivator, Oct2 and OBF-1. J Exp Med 2012;209:2049–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elsaesser H, Sauer K, Brooks DG. IL-21 is required to control chronic viral infection. Science (New York, NY) 2009;324:1569–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frohlich A, Kisielow J, Schmitz I, Freigang S, Shamshiev AT, Weber J, et al. IL-21R on T cells is critical for sustained functionality and control of chronic viral infection. Science (New York, NY) 2009;324:1576–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yi JS, Du M, Zajac AJ. A vital role for interleukin-21 in the control of a chronic viral infection. Science (New York, NY) 2009;324:1572–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schmitz I, Schneider C, Frohlich A, Frebel H, Christ D, Leonard WJ, et al. IL-21 restricts virus-driven Treg cell expansion in chronic LCMV infection. PLoS Pathog 2013;9:e1003362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pawlak K, Mysliwiec M, Pawlak D. Interleukin-21 in hemodialyzed patients: association with the etiology of chronic kidney disease and the seropositivity against hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Biochem 2011;44:1416–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Franks I Viral hepatitis: interleukin 21 has a key role in age-dependent response to HBV. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;8:243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma SW, Huang X, Li YY, Tang LB, Sun XF, Jiang XT, et al. High serum IL-21 levels after 12 weeks of antiviral therapy predict HBeAg seroconversion in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 2012;56:775–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Publicover J, Goodsell A, Nishimura S, Vilarinho S, Wang ZE, Avanesyan L, et al. IL-21 is pivotal in determining age-dependent effectiveness of immune responses in a mouse model of human hepatitis B. J Clin Invest 2011;121:1154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ma Z, Xie Y, Wang Y, Ma L, He Y, Zhang Y, et al. Peripheral blood CD4(+);CXCR5(+); follicular helper T cells are related to hyperglobulinemia of patients with chronic hepatitis B. Xi bao yu fen zi mian yi xue za zhi Chin J Cell Mol Immunol 2013;29:515–8, 21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kared H, Fabre T, Bedard N, Bruneau J, Shoukry NH. Galectin-9 and IL-21 mediate cross-regulation between Th17 and Treg cells during acute hepatitis C. PLoS Pathog 2013;9:e1003422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li L, Liu M, Cheng L, Gao X, Fu J, Kong G, et al. HBcAg-specific IL-21 producing-CD4 + T cells are associated with relative viral control in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Scand J Immunol 2013;78:439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li N, Zhu Q, Li Z, Han Q, Chen J, Lv Y, et al. IL21 and IL21R polymorphisms and their interactive effects on serum IL-21 and IgE levels in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hum Immunol 2013;74:567–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Petrovas C, Yamamoto T, Gerner MY, Boswell KL, Wloka K, Smith EC, et al. CD4 T follicular helper cell dynamics during SIV infection. J Clin Investig 2012;122:3281–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nutt SL, Tarlinton DM. Germinal center B and follicular helper T cells: siblings, cousins or just good friends+ Nat Immunol 2011;12:472–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Victora GD, Nussenzweig MC. Germinal centers. Annu Rev Immunol 2012;30:429–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eto D, Lao C, DiToro D, Barnett B, Escobar TC, Kageyama R, et al. IL-21 and IL-6 are critical for different aspects of B cell immunity and redundantly induce optimal follicular helper CD4 T cell (Tfh) differentiation. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e17739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Linterman MA, Beaton L, Yu D, Ramiscal RR, Srivastava M, Hogan JJ, et al. IL-21 acts directly on B cells to regulate Bcl-6 expression and germinal center responses. J Exp Med 2010;207:353–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Spolski R, Leonard WJ. IL-21 and T follicular helper cells. Int Immunol 2009;22:7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Recher M, Berglund LJ, Avery DT, Cowan MJ, Gennery AR, Smart J, et al. IL-21 is the primary common gamma chain-binding cytokine required for human B-cell differentiation in vivo. Blood 2011;118:6824–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu YJ, Zhang J, Lane PJ, Chan EY, MacLennan IC. Sites of specific B cell activation in primary and secondary responses to T cell-dependent and T cell-independent antigens. Eur J Immunol 1991;21:2951–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jacob J, Kassir R, Kelsoe G. In situ studies of the primary immune response to (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl. I. The architecture and dynamics of responding cell populations. J Exp Med 1991;173:1165–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Inamine A, Takahashi Y, Baba N, Miyake K, Tokuhisa T, Takemori T, et al. Two waves of memory B-cell generation in the primary immune response. Int Immunol 2005;17:581–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zotos D, Coquet JM, Zhang Y, Light A, D’Costa K, Kallies A, et al. IL-21 regulates germinal center B cell differentiation and proliferation through a B cell-intrinsic mechanism. J Exp Med 2010;207:365–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee SK, Rigby RJ, Zotos D, Tsai LM, Kawamoto S, Marshall JL, et al. B cell priming for extrafollicular antibody responses requires Bcl-6 expression by T cells. J Exp Med 2011;208:1377–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Odegard JM, Marks BR, DiPlacido LD, Poholek AC, Kono DH, Dong C, et al. ICOS-dependent extrafollicular helper T cells elicit IgG production via IL-21 in systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med 2008;205:2873–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tellier J, Nutt SL. The unique features of follicular T cell subsets. Cell Mol Life Sci 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1420-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Haynes NM, Allen CD, Lesley R, Ansel KM, Killeen N, Cyster JG. Role of CXCR5 and CCR7 in follicular Th cell positioning and appearance of a programmed cell death gene-1high germinal center-associated subpopulation. J Immunol 2007;179:5099–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hardtke S, Ohl L, Forster R. Balanced expression of CXCR5 and CCR7 on follicular T helper cells determines their transient positioning to lymph node follicles and is essential for efficient B-cell help. Blood 2005;106:1924–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Crotty S Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu Rev Immunol 2011;29:621–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chtanova T, Tangye SG, Newton R, Frank N, Hodge MR, Rolph MS, et al. T follicular helper cells express a distinctive transcriptional profile, reflecting their role as non-Th1/Th2 effector cells that provide help for B cells. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2004;173:68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Luthje K, Kallies A, Shimohakamada Y, Belz GT, Light A, Tarlinton DM, et al. The development and fate of follicular helper T cells defined by an IL-21 reporter mouse. Nat Immunol 2012;13:491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pot C, Jin H, Awasthi A, Liu SM, Lai CY, Madan R, et al. Cutting edge: IL-27 induces the transcription factor c-Maf, cytokine IL-21, and the costimulatory receptor ICOS that coordinately act together to promote differentiation of IL-10-producing Tr1 cells. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2009;183:797–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Martinez GJ, Yang XO, Tanaka S, Matskevitch TD, et al. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science (New York, NY) 2009;325:1001–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kroenke MA, Eto D, Locci M, Cho M, Davidson T, Haddad EK, et al. Bcl6 and maf cooperate to instruct human follicular helper CD4 T cell differentiation. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2012;188:3734–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fazilleau N, Mark L, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Follicular helper T cells: lineage and location. Immunity 2009;30:324–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Johnston RJ, Poholek AC, DiToro D, Yusuf I, Eto D, Barnett B, et al. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science (New York, NY) 2009;325:1006–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mehta DS, Wurster AL, Whitters MJ, Young DA, Collins M, Grusby MJ. IL-21 induces the apoptosis of resting and activated primary B cells. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2003;170:4111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pallikkuth S, Parmigiani A, Pahwa S. Role of IL-21 and IL-21 receptor on B cells in HIV infection. Crit Rev Immunol 2012;32:173–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ettinger R, Sims GP, Fairhurst AM, Robbins R, da Silva YS, Spolski R, et al. IL-21 induces differentiation of human naive and memory B cells into antibody-secreting plasma cells. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2005;175:7867–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Morita R, Schmitt N, Bentebibel SE, Ranganathan R, Bourdery L, Zurawski G, et al. Human blood CXCR5(+)CD4(+) T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity 2011;34:108–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rankin AL, MacLeod H, Keegan S, Andreyeva T, Lowe L, Bloom L, et al. IL-21 receptor is critical for the development of memory B cell responses. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2011;186:667–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Avery DT, Deenick EK, Ma CS, Suryani S, Simpson N, Chew GY, et al. B cell-intrinsic signaling through IL-21 receptor and STAT3 is required for establishing long-lived antibody responses in humans. J Exp Med 2010;207:155–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kurosaki T, Shinohara H, Baba Y. B cell signaling and fate decision. Annu Rev Immunol 2010;28:21–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bryant VL, Ma CS, Avery DT, Li Y, Good KL, Corcoran LM, et al. Cytokine-mediated regulation of human B cell differentiation into Ig-secreting cells: predominant role of IL-21 produced by CXCR5 + T follicular helper cells. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2007;179:8180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Diehl SA, Schmidlin H, Nagasawa M, van Haren SD, Kwakkenbos MJ, Yasuda E, et al. STAT3-mediated up-regulation of BLIMP1 Is coordinated with BCL6 down-regulation to control human plasma cell differentiation. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2008;180:4805–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Moir S, Fauci AS. B cells in HIV infection and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2009;9:235–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.van Grevenynghe J, Cubas RA, Noto A, DaFonseca S, He Z, Peretz Y, et al. Loss of memory B cells during chronic HIV infection is driven by Foxo3a- and TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. J Clin Investig 2011;121:3877–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Amu S, Ruffin N, Rethi B, Chiodi F. Impairment of B-cell functions during HIV-1 infection. AIDS (London, England) 2013;27:2323–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Moir S, Fauci AS. Insights into B cells and HIV-specific B-cell responses in HIV-infected individuals. Immunol Rev 2013;254:207–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Malaspina A, Moir S, Orsega SM, Vasquez J, Miller NJ, Donoghue ET, et al. Compromised B cell responses to influenza vaccination in HIV-infected individuals. J Infect Dis 2005;191:1442–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Moir S, Malaspina A, Ho J, Wang W, Dipoto AC, O’Shea MA, et al. Normalization of B cell counts and subpopulations after antiretroviral therapy in chronic HIV disease. J Infect Dis 2008;197:572–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Iannello A, Boulassel MR, Samarani S, Debbeche O, Tremblay C, Toma E, et al. Dynamics and consequences of IL-21 production in HIV-infected individuals: a longitudinal and cross-sectional study. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2010;184:114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Iannello A, Tremblay C, Routy JP, Boulassel MR, Toma E, Ahmad A. Decreased levels of circulating IL-21 in HIV-infected AIDS patients: correlation with CD4 + T-cell counts. Viral Immunol 2008;21:385–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fazilleau N, Eisenbraun MD, Malherbe L, Ebright JN, Pogue-Caley RR, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, et al. Lymphoid reservoirs of antigen-specific memory T helper cells. Nat Immunol 2007;8:753–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rasheed AU, Rahn HP, Sallusto F, Lipp M, Muller G. Follicular B helper T cell activity is confined to CXCR5(hi)ICOS(hi) CD4 T cells and is independent of CD57 expression. Eur J Immunol 2006;36:1892–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hale JS, Youngblood B, Latner DR, Mohammed AU, Ye L, Akondy RS, et al. Distinct memory CD4 + T cells with commitment to T follicular helper- and T helper 1-cell lineages are generated after acute viral infection. Immunity 2013;38:805–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Weber JP, Fuhrmann F, Hutloff A. T-follicular helper cells survive as long-term memory cells. Eur J Immunol 2012;42:1981–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Schaerli P, Loetscher P, Moser B. Cutting edge: induction of follicular homing precedes effector Th cell development. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2001;167:6082–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Schaerli P, Willimann K, Lang AB, Lipp M, Loetscher P, Moser B. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J Exp Med 2000;192:1553–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Forster R, Emrich T, Kremmer E, Lipp M. Expression of the G-protein–coupled receptor BLR1 defines mature, recirculating B cells and a subset of T-helper memory cells. Blood 1994;84:830–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Forster R, Mattis AE, Kremmer E, Wolf E, Brem G, Lipp M. A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell 1996;87:1037–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kim CH, Rott LS, Clark-Lewis I, Campbell DJ, Wu L, Butcher EC. Subspecialization of CXCR5 + T cells: B helper activity is focused in a germinal center-localized subset of CXCR5 + T cells. J Exp Med 2001;193:1373–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol 2004;22:745–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Pallikkuth S, Parmigiani A, Silva SY, George VK, Fischl M, Pahwa R, et al. Impaired peripheral blood T-follicular helper cell function in HIV-infected non-responders to the 2009 H1N1/09 vaccine. Blood 2012;120:985–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Marshall HD, Chandele A, Jung YW, Meng H, Poholek AC, Parish IA, et al. Differential expression of Ly6C and T-bet distinguish effector and memory Th1 CD4(+) cell properties during viral infection. Immunity 2011;35:633–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.MacLeod MK, David A, McKee AS, Crawford F, Kappler JW, Marrack P. Memory CD4 T cells that express CXCR5 provide accelerated help to B cells. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2011;186:2889–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bossaller L, Burger J, Draeger R, Grimbacher B, Knoth R, Plebani A, et al. ICOS deficiency is associated with a severe reduction of CXCR5 + CD4 germinal center Th cells. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2006;177:4927–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Locci M, Havenar-Daughton C, Landais E, Wu J, Kroenke MA, Arlehamn CL, et al. Human Circulating PD-1CXCR3CXCR5 memory Tfh cells are highly functional and correlate with broadly neutralizing HIV antibody responses. Immunity 2013;39:758–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Pallikkuth S, Fischl MA, Pahwa S. Combination antiretroviral therapy with raltegravir leads to rapid immunologic reconstitution in treatment-naive patients with chronic HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2013;208:1613–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pallikkuth S, Kanthikeel SP, Silva SY, Fischl M, Pahwa R, Pahwa S. Innate immune defects correlate with failure of antibody responses to H1N1/09 vaccine in HIV-infected patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:1279–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Pallikkuth S, Pilakka Kanthikeel S, Silva SY, Fischl M, Pahwa R, Pahwa S. Upregulation of IL-21 receptor on B cells and IL-21 secretion distinguishes novel 2009 H1N1 vaccine responders from nonresponders among HIV-infected persons on combination antiretroviral therapy. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md: 1950) 2011;186:6173–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Bentebibel SE, Lopez S, Obermoser G, Schmitt N, Mueller C, Harrod C, et al. Induction of ICOS + CXCR3 + CXCR5 + TH cells correlates with antibody responses to influenza vaccination. Sci Transl Med 2013;5:176ra32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Reber AJ, Chirkova T, Kim JH, Cao W, Biber R, Shay DK, et al. Immunosenescence and challenges of vaccination against influenza in the aging population. Aging Dis 3:68–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Deeks SG, Verdin E, McCune JM. Immunosenescence and HIV. Curr Opin Immunol 2012;24:501–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet 2008;372:293–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.High KP, Brennan-Ing M, Clifford DB, Cohen MH, Currier J, Deeks SG, et al. HIV and aging: state of knowledge and areas of critical need for research. A report to the NIH Office of AIDS research by the HIV and aging working group. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 60(Suppl 1):S1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Alcaide ML, Parmigiani A, Pallikkuth S, Roach M, Freguja R, Della Negra M, et al. Immune activation in HIV-infected aging women on antiretrovirals–implications for age-associated comorbidities: a cross-sectional pilot study. PloS one 2013;8:e63804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]