Abstract

Background and Aims:

Findings of the association between racial discrimination and alcohol use and related consequences are inconsistent and the role of potential moderators in the association is largely unknown. This meta-analysis aimed to synthesize the discrimination-alcohol literature among Black Americans, estimate magnitude of associations, and explore differences as a function of sample characteristics.

Methods:

Empirical studies reporting the association of racial discrimination with alcohol-related behaviors in an all-Black sample were identified via systematic literature search. A random-effects meta-analysis was conducted using 33 effect sizes extracted from 27 studies, all of which used U.S. samples (n = 26,894).

Results:

Significant positive associations were found for racial discrimination with alcohol consumption (k = 9, CI = [0.08, 0.17], I2 = 49%, r = .12), heavy/binge drinking (k = 12, CI = [0.02, 0.10], I2 = 27%, r = .06), at-risk drinking (k = 4, CI = [0.06, 0.23], I2 = 0%, r = .14), and negative drinking consequences (k = 5, CI = [0.09, 0.25], I2 = 94%, r = .25), but not with alcohol use disorder (k = 3, CI = [−0.01, 0.20], I2 = 90%, r = .10). Only alcohol consumption and negative drinking consequences showed significant between-study heterogeneity and had a sufficient quantity of studies for moderation analysis (k ≥ 4). The positive association of racial discrimination with negative drinking consequences was stronger among younger samples; the association with alcohol consumption did not differ by age or proportion of men.

Conclusions:

Experiences of racial discrimination are associated with diverse alcohol-related behaviors among Black Americans, with a stronger association with problematic alcohol use particularly among younger individuals.

Keywords: racial discrimination, alcohol use, alcohol use disorder, alcohol screeners, negative drinking consequences, Black American

Alcohol-related behaviors among Black Americans substantially differ from other racial groups. Black Americans aged 18 and older report lower rates of past-year alcohol use (63%) than White Americans (74%; [1]), while drinking frequency increases at a faster rate among Blacks during the transition into adulthood [2]. Black adults also experience greater levels of negative drinking consequences compared to other racial groups [3], even after accounting for alcohol consumption levels [4–6]. Thus, although Blacks drink less than Whites, their drinking behaviors accelerate faster, are more stable across adulthood, and result in relatively greater consequences. Continued research is needed to identify racially-relevant contributors to this alcohol-related disparity, specifically among Black Americans [7].

Racial discrimination has been identified as a potential stressor contributing to alcohol-related behaviors among Black Americans [8–9]. Racial discrimination is defined as perceived and/or internalized beliefs, attitudes, institutional arrangements, and acts that denigrate Americans because of their racial group. A biopsychosocial stress-coping model [8] posits that the stress of experiencing discrimination results in heightened psychological stress responses and depleted coping resources, thus increasing engagement in maladaptive coping behaviors such as alcohol use. Consistent with this model, racial discrimination has been associated with negative mental and physical health outcomes (e.g., anxiety/depression, hypertension, substance use) in racially-diverse samples [11]. However, the extent to which racial discrimination affects Black Americans’ alcohol-related behaviors specifically warrants further investigation.

Individual differences within Blacks (versus differences between racial groups) have been relatively understudied in the discrimination and alcohol literature. Blacks show a distinct pattern of alcohol-related behaviors over the course of development [7] and a higher level of racial discrimination experiences [12–15] compared to other racial groups. The association between racial discrimination and alcohol-related behaviors is stronger among Blacks than racial counterparts [12, 16–17]. However, findings are mixed when assessing all-Black samples, with some studies reporting positive associations [12, 18] and others reporting null results [19–20]. Researchers have called for studies focusing solely on Black Americans in efforts to broaden our understanding of antecedents to alcohol use and consequences within this racial group in the U.S. [7].

Heterogeneity in the discrimination-alcohol literature may be explained by sample differences, including age and sex. Theoretical frameworks [8] posit that age may modify the discrimination-health outcome relationship, although the anticipated direction of effects remains uncertain. On one hand, Black youth may be more vulnerable to the harmful effects of racial discrimination due to underdeveloped coping resources [21]. On the other hand, older Black individuals may be more vulnerable due to accumulation of discrimination experiences over time and chronic stress exposure [8]. Regarding sex, Black men have consistently been shown to report more experiences of racial discrimination than Black women [12, 22–24]. Many studies investigating the discrimination-alcohol association have included both age and sex as covariates [25–27], bypassing investigation of how associations may differ by sociodemographic factors.

Existing Reviews

A number of qualitative and quantitative reviews have assessed the role of discrimination in specific health outcomes (e.g., cardiovascular [28] and mental [11] health) or a wide range of health outcomes (e.g., physical health, mental health, and health behaviors; [10, 29–30]) among Black individuals. A recent qualitative review [31] was the first to focus solely on the reportedly positive association of racial discrimination and alcohol-related behaviors. No meta-analytic synthesis has been conducted on racial discrimination and alcohol-related behaviors among Blacks, despite aforementioned heterogeneity of previous findings.

The Current Meta-Analysis

This study aimed to synthesize research on associations between racial discrimination and various alcohol-related behaviors (i.e., alcohol use frequency and quantity, alcohol use disorder, alcohol screeners and negative consequences) among Black Americans, as well as possible individual-level moderators (i.e., age and sex). This is the first synthesized meta-analytic review of racial discrimination and alcohol-related behaviors among Blacks, which may inform racially-tailored prevention/treatment efforts. This review was prepared in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [32]; the study was not registered and no funding was sought.

Methods

Literature Search

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify peer-reviewed empirical articles investigating the association of racial discrimination and alcohol-related behaviors among Blacks. Searches were conducted during August to September 2017 with the PubMed and PsychINFO online databases using the following search terms: (racial discrimination, racism, OR, prejudice) AND (Black or African-American) AND alcohol. Database selection is consistent with previous reviews of racial discrimination and health outcomes [29–31]. Additionally, the reference lists of the identified articles and relevant reviews/meta-analyses were hand-searched.

Inclusion Criteria and Study Selection

For inclusion in the present meta-analysis, studies needed to meet the following criteria: (a) investigating racial discrimination as an exposure variable (perceived racial discrimination [i.e., self-reported racism experienced based on one’s personal perception and interpretation of an incident or interaction] and internalized racism [i.e., the incorporation of racist attitudes and/or beliefs within an individual’s worldview]); (b) including an alcohol-related behavior as a dependent variable; (c) reporting quantitative data, and (d) having an all-Black sample. Studies that measured a composite substance use variable (that included but was not limited to alcohol use) were excluded. Study samples that were not comprised of all-Black individuals were included if a subset of analyses were conducted and sufficient statistical information was provided for an all-Black subsample. Elimination of articles was done through full-text review.

Alcohol Variables of Interest

Effect size estimates were extracted for five domains: alcohol consumption, binge/heavy drinking, at-risk drinking, alcohol use disorders (AUDs), and negative drinking consequences. The alcohol consumption domain (k = 9) was operationally defined as drinking quantity (k = 4), frequency (k = 2), and quantity multiplied by drinking frequency (k = 3). Binge/heavy drinking (k =12) domain included variables utilizing different definitions of binge drinking and heavy episodic drinking with the most common definition of consuming five or more drinks in a single sitting irrespective of sex. The at-risk drinking domain (k = 4) was operationally defined by a significant alcohol screener including the CAGE (k = 3) and the AUDIT-C (k = 1); the CAGE [33] is a 4-item screening measure and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Alcohol Consumption Questions [AUDIT-C, 34] is a 3-item screening measure. In the AUD domain (k = 9), all studies used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) criteria. Finally, the negative drinking consequences domain (k = 5) included multi-item self-report scales assessing an array of potentially negative physical, social, and behavioral consequences experienced from alcohol use, such as getting into a fight, hangovers, and getting into a car accident. For the alcohol consumption and at-risk drinking domains, summary effect sizes across different variables were calculated to increase power given the small number of studies of each specific alcohol variable.

Data Extraction

Data regarding participants, study design, discrimination measures, alcohol measures, and effect sizes were extracted from each study. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were used as the measure of effect size. Given that r does not follow the normal distribution, r was converted to Fisher’s z and then reconverted to r [35]. For studies reporting effect sizes other than r (e.g., Odds Ratio), their effect sizes were converted into r using the Campbell Collaboration web-based effect size calculator [36]. Given that few studies adjusted for the same covariates, unadjusted (as opposed to adjusted) effect sizes were used [35]. Cross-tabulations (2×2) of events and non-events (e.g., discrimination/no discrimination and drinking/no drinking) were converted to r. When multiple alcohol-related behaviors were reported, a separate effect size of each behavior was extracted. Corresponding authors were contact to retrieve relevant information as needed; requested data was obtained for four studies and effect sizes were included in analysis., A checklist by the Joanna-Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal tools for use in systematic reviews [37] was used to assess four domains of study quality: selection and description of participants, validity and reliability of exposure and outcome measures, confounding variables, and appropriate use of statistical analyses.

Data were extracted by two independent coders (JMD and PAG) using piloted forms. Inter-rater reliability was excellent for categorical variables (88% agreement) and continuous variables (median intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.98). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two coders.

Data Synthesis

Meta-analytic synthesis was conducted using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software, version 3.0 [35]. A random effects model was estimated in all analyses under the assumption that there was variation in the observed effect sizes due to between-study heterogeneity [35]. Between-study heterogeneity was estimated with two statistical indices. First, the Q-statistic is a null hypothesis significance test of the presence of heterogeneity across studies [32]. Second, the I2 statistic represents the extent to which heterogeneity exists across studies (i.e., percentage of total between-study variability), with 25%, 50%, and 75% representing low, moderate, and high variance, respectively [35, 38].

Moderation analyses.

When significant between-study heterogeneity was found, potential moderation by mean age and proportion of men in samples were examined for alcohol variables that had at least four effect sizes. Criteria for exploratory moderation analysis was implemented to insure sufficient power, consistent with a previous meta-analytic review [29]. Continuous moderators were tested through meta-regression using method-of-moments (also known as the DerSimonian and Laird method; [39]) for parameter estimation.

Publication bias.

Both funnel plot [35] and the Egger regression asymmetry test [40] were used to test potential publication bias.

Results

Study Selection

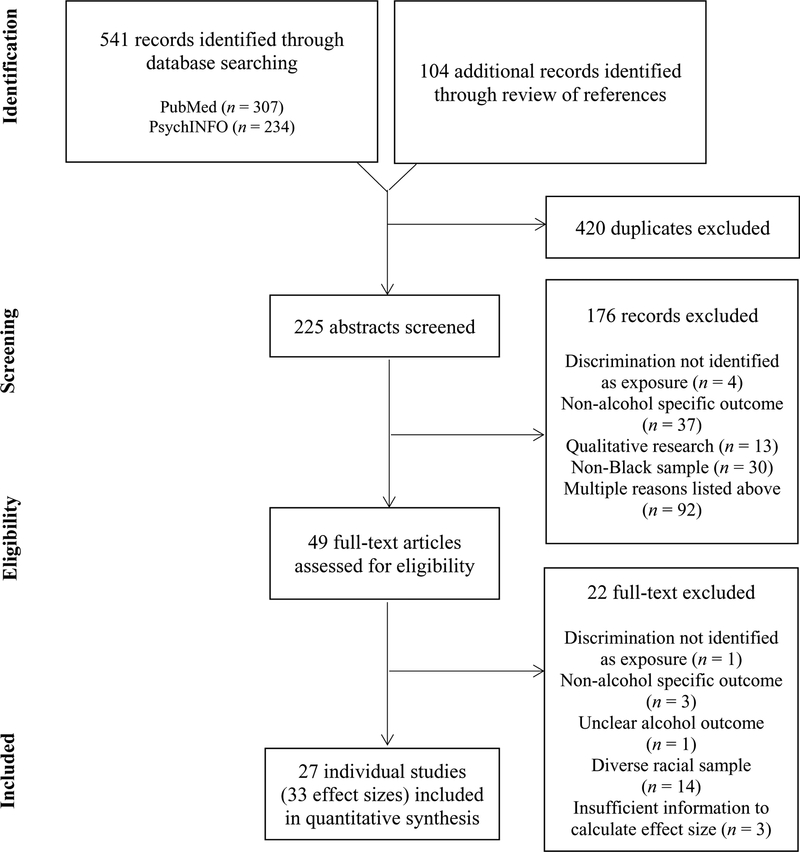

A flowchart of the study selection approach is displayed in Figure 1. Of the 645 articles identified as potentially relevant through initial searches, 420 were found to be duplicates, and the remaining 225 abstracts were screened for inclusion. Of the 225 abstracts screened, 176 were excluded due to violations of eligibility criteria and 49 remained for full-text review. Of 49 full-text articles assessed for eligibility, 22 studies were excluded due to their mixed racial samples (and no separate data for all-Black subsamples), composite substance use variable (and no separate alcohol variables), unavailable effect sizes (and insufficient information to calculate effect sizes), the use of discrimination as a non-exposure variable, and/or the use of the combination of the DSM-IV and CAGE for the AUD diagnosis. As a result, 33 effect sizes from 27 individual studies were included for meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of studies selected for meta-analysis. Diagram prepared in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA) guidelines [32].

Study Characteristics

Study characteristics and effect sizes are presented in Table 1. Modal publication years were 2013 and 2014 (33%). All included studies were conducted in the U.S.A., with most studies using community-based samples (77%), as opposed to school-based samples. Also, most studies were of a cross-sectional study design (85%), as opposed to a longitudinal design (with lengths of the follow-up assessment ranging from 30 days to 13 years). The most commonly investigated alcohol variable was heavy/binge drinking (44%), despite some differences in the definition; most defined it as consuming five or more drinks in a single sitting irrespective of sex [e.g., 19, 35], although some studies implemented a sex-specific criterion of four or more drinks for women and five or more for men [e.g., 11, 25]. The total number of participants included for this meta-analysis was 26,894 (range: n = 71 – 6,587 per study) with an average age of 33 years (range: 16 – 45 years). The median proportion of men was 45% (range: 0% – 100%).

Table 1.

Summary of Studies Included in Meta-Analysis (k = 27)

| Study | Study Design (length of follow-up) |

Recruitment Setting | n | Age M (SD) |

Male (%) | Alcohol-Related Variables |

Key Finding(s) |

Included Effect Size(s) Converted to r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borrell et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional | Community | 1839 | — | 47% | Heavy/binge | ns | 0.17 |

| Borrell et al., 2007 | Longitudinal (8yrs) | Community | 1507 | 40 (4) | 41% | Heavy/binge | + | 0.03 |

| Borrell et al., 2013 | Longitudinal (13yrs) | Community | 1169 | 40 (4) | 28% | Heavy/binge | ns | 0.02 |

| Boynton et al., 2014 | Cross-sectional | School | 619 | 20 (2) | 47% | Consumption; consequences | ns; + | 0.11; 0.47 |

| Caldwell et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional | Community | 332 | 37 (8) | 100% | Consumption | ns | 0.09 |

| Desalu et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional | School | 251 | 20 (4) | 34% | Heavy/binge; consequences | ns; + | −.01; 0.30 |

| Factor et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional | Community | 200 | 44 (15) | 46% | Consumption | + | 0.08 |

| Gibbons et al., 2014 | Longitudinal (~6yrs) | Community | 680 | 37 | 0% | Consequences | + | 0.17 |

| Hunte & Barry, 2012 | Cross-sectional | Community | 5008 | 42 | 44% | AUD | + | 0.01 |

| Hurd et al., 2014 | Longitudinal (4yrs) | School | 607 | 20 (0.65) | 47% | Consumption | + | 0.21 |

| Kwate et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional | Community | 139 | 34(8) | 0% | Heavy/binge; At-risk drinking | ns; + | −0.10; 0.07 |

| Kwate et al., 2003 | Cross-sectional | Community | 71 | 44 | 0% | Consumption | + | 0.40 |

| Madkour et al., 2015 | Cross-sectional | Community | 657 | 21 | 55% | Heavy/binge | + | 0.11 |

| McLaughlin et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional | Community | 6587 | — | — | AUD | + | 0.16 |

| Mulia & Zemore 2012 | Cross-sectional | Community | 504 | 44 | — | Heavy/binge; AUD | ns; NA | 0.05; 0.13 |

| O’Hara et al., 2015 | Longitudinal (30 days) | School | 441 | 20 (2) | 42% | Consumption | ns | 0.14 |

| Respress et al., 2013 | Cross-sectional | School | 514 | — | — | Heavy/binge | ns | −0.03 |

| Sanders-Phillips et al., 2014 | Cross-sectional | School | 567 | 16 (1) | 39% | Consumption | + | 0.06 |

| Shariff-Marco et al., 2009 | Cross-sectional | Community | 2361 | — | — | Heavy/binge | ns | 0.12 |

| Smith & Taylor, 2015 | Cross-sectional | School | 201 | — | 100% | Consumption | + | 0.12 |

| Squires et al., 2017 | Cross-sectional | Community | 203 | 44(12) | 68% | At-risk drinking | ns | 0.10 |

| Taylor & Jackson, 1990 | Cross-sectional | Community | 289 | — | 0% | Consumption | + | 0.10 |

| Thompson et al., 2016 | Cross-sectional | Community | 144 | 45 (16) | 48% | Heavy/binge; At-risk drinking | +; + | 0.07; 0.23 |

| Tran et al., 2010 | Cross-sectional | Community | 555 | — | 46% | Heavy/binge | ns | 0.12 |

| Yen et al., 1999(a) | Cross-sectional | Community | 477 | — | — | Consequences | + | 0.26 |

| Yen et al., 1999(b) | Cross-sectional | Community | 468 | — | — | Heavy/binge; At-risk drinking | +; + | 0.14; 0.19 |

| Zemore et al., 2011 | Cross-sectional | Community | 504 | 41 | — | Consequences | + | 0.09 |

Note. Consumption = alcohol consumption; AUD = alcohol use disorder; At-risk drinking measured by AUDIT-C or CAGE; length of assessment period of longitudinal studies indicated in parentheses; ns = non-significant; + = positive association; NA = not available (i.e., direct association not tested/reported)

Study Quality

The most common sources of methodological concern arose from unclear inclusion and exclusion criteria regarding the selection of study participants (see Supplemental Table 1). Specifically, 48% of studies did not include clear information about the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the participants in the study. All studies accounted for one or more confounding variables (e.g., sex, age) and all studies implemented appropriate statistical analyses to investigate research questions.

Discrimination-Alcohol Associations

Table 2 presents the summary effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between racial discrimination and each alcohol variable of the five domains. Forest plots are available to online as Supplemental materials (Supplemental Figures 1 – 5).

Table 2.

Effect Size and Heterogeneity Estimates from Random Effects Models by Alcohol-related behaviors

| Alcohol-Related Behaviors | k | r (95% CI) | Q | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Consumption | 9 | .12 (0.08, 0.17)*** | 15.79* | 49.35 |

| Heavy/binge Drinking | 12 | .06 (0.02, 0.10)** | 15.03 | 26.80 |

| At-Risk Drinking | 4 | .14 (0.06, 0.23)** | 2.43 | 0.00 |

| AUD | 3 | .10 (−0.01, 0.20) | 20.76*** | 90.37 |

| Negative Drinking Consequences | 5 | .25 (0.09, 0.42)** | 65.99*** | 94.00 |

Note. The Alcohol Consumption variable combines all effect sizes of alcohol use quantity, alcohol use frequency, and quantity*frequency measures. The At-Risk Drinking variable combines all effect sizes of the CAGE and AUDIT-C measures. A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis [35] was performed by iteratively removing 1 study at a time to confirm that our findings were not driven by any single study. All effect sizes remained stable across variables, with one exception; the association of AUD DSM-IV Criteria with racial discrimination became significant (r = .15 [0.10, 0.20], p < .05) upon removal of Hunte & Barry, 2012. CI: confidence interval.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Alcohol consumption.

A significant positive association was observed between racial discrimination and the overall alcohol consumption composite measure (r = .12, 95% CI [0.08, 0.17], k = 9, p = .000). Significant, low-to-moderate heterogeneity was observed across studies (Q8 = 15.79, p = .045, I2 = 49%).

Heavy/binge drinking.

A significant positive association was observed between racial discrimination and heavy/binge drinking (r = .06, 95% CI [0.02, 0.10], k = 12, p = .002), with no significant heterogeneity across studies (Q11 = 15.03, I2 = 27%).

At-risk drinking.

A significant positive association was observed between racial discrimination and the at-risk screener composite (r = .14, 95% CI [0.06, 0.23], k = 4, p = .001), with no heterogeneity across studies (Q3= 2.43, p = .49, I2 = 0%).

AUDs.

No significant association was observed between racial discrimination and presence of an AUD based on DSM-IV criteria (r = .10, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.20], k = 3, p = .08), although there was high heterogeneity across studies (Q2 = 20.76, p < .001, I2 = 90%).

Negative drinking consequences.

A significant positive association was observed between racial discrimination and negative drinking consequences (r = .25, 95% CI [0.09, 0.42], k = 5, p = .003), with high heterogeneity across studies (Q4 = 65.99, p < .001, I2 = 94%).

Moderation by Age and Sex

Although significant between-study heterogeneity was found for three alcohol measures (i.e., alcohol consumption composite, presence of an AUD, and negative drinking consequences), exploratory moderation analyses were conducted only for alcohol consumption composite (k = 9) and negative drinking consequences (k = 5) variables due to sufficient quantity of studies. Studies that did not include information on age and sex were excluded from analyses.

Age was not significantly associated with the magnitude of the relationship between racial discrimination and alcohol consumption (k = 7; b = 0.001; p = .76). However, significant moderation by age was observed for drinking consequences (k = 4; b = −0.02; p = .001), indicating stronger positive associations of racial discrimination with drinking consequences in studies of younger samples. Proportion of men was not significantly associated with the magnitude of the relationship between racial discrimination and alcohol consumption (k = 9; b = −0.002; p = .19). Only three studies assessing drinking consequences reported proportion of men, precluding moderation analysis.

Publication Bias

Funnel plots did not provide indications of asymmetry for all alcohol variables examined. These findings were supported by non-significant results of the Egger regression asymmetry tests for publication bias (t’s = 0.26 – 2.77; p’s = .16 – .81).

Discussion

The present meta-analysis examined the extent to which racial discrimination was associated with diverse alcohol variables among Black Americans. Data were extracted from 27 empirical articles with 33 effect sizes retained across all studies. Summary effect sizes revealed that racial discrimination was associated with alcohol consumption, heavy/binge drinking, at-risk drinking, and negative drinking consequences, but not alcohol use disorder. The magnitude of association with negative drinking consequences was stronger in younger samples. The magnitude of association with alcohol consumption did not differ across age or proportion of men in samples. Findings provide compelling quantitative evidence of the association between racial discrimination and alcohol-related behaviors, as well as moderators of these associations among Black Americans.

Findings support theoretical frameworks suggesting that individuals may use alcohol to cope with experienced racial discrimination [8]. Congruent with discrimination-alcohol literature [3, 7, 41], racial discrimination demonstrated the strongest association with negative drinking consequences (r = .25) as opposed to alcohol consumption measures. Racial discrimination was also significantly associated with the alcohol consumption (r = .12) and at-risk drinking (r = .14) composite; however, the low number of effect sizes included in the latter (k = 4) could also have potentially influenced the validity of such findings. The stress-dampening effects of consuming alcohol may negatively reinforce coping drinking behaviors, resulting in accelerated drinking rates and related problems over time [42–43].

The null finding in AUDs may be due to the small number of studies (k = 3 for AUDs) included, as well as high levels of heterogeneity (I2 = 90%) among these studies. Additionally, individuals who use alcohol to cope with stressors (e.g., racial discrimination) have demonstrated risk for consuming alcohol at greater quantities, versus greater frequency [44]. Previous literature suggests that it is common for Black individuals to be “diagnostic orphans” of AUDs (i.e., meet subthreshold levels of a disorder; [45, 46]). The DSM-IV criteria for AUDs may not have been sensitive enough to capture racially-unique manifestation among Blacks [47].

This study also elucidated age as a moderator of the association between racial discrimination and negative drinking consequences. Samples of young adults demonstrated stronger associations of racial discrimination with negative drinking consequences. Findings parallel theoretical frameworks suggesting that Black young adults (versus older adults) are more vulnerable to the harmful effects of racial discrimination, given relatively under-established adaptive coping resources [21]. However, college samples could have had an outsized effect on our findings on age as a moderator, given the alcohol-facilitating and heavy drinking milieu of college campuses. Future research may explore differences in the discrimination-alcohol association across college versus non-college individuals.

Regarding sex as a moderator, associations of racial discrimination with composite measures of alcohol consumption did not differ between males and females. Findings are congruent with previous meta-analyses on comparable topics of racism and health [21]. Analyses examined the proportion of men as a moderator (versus direct comparisons between male and female subsamples), which is a limitation necessitated by data available (several studies [k = 11] omitted demographic characteristics). Although sex differences are not observed in direct associations of racial discrimination with alcohol measures, there may be sex differences in pathways underlying the association [48]. High levels of racial discrimination experienced by young Black men warrants future exploration of the three-way interaction effects among age, sex and racial discrimination on alcohol-related behaviors.

Limitations with Existing Research and Future Directions

Assessment of racial discrimination.

Substantial differences in discrimination measures [53] likely contributed to heterogeneity across studies. Three studies employed a single-item measure [17, 20, 54] versus multi-item scales, which may yield highly conservative prevalence rates and poorer predictive validity and reliability [55]. Another unresolved issue is the assessment of unfair treatment based on race specifically (one-stage approach), versus race in combination of other sources (e.g., sex; two-stage approach). Competing approaches have generated debate regarding the optimal assessment of racial discrimination; however, no consensus has been reached [56]. A gold-standard, reliable racial discrimination measure grounded in theory may ameliorate inconsistencies in the literature.

Research investigating associations of distinct types of racial discrimination with alcohol variables among Blacks is lacking. Racial discrimination is a multidimensional concept and its assessment should provide comprehensive coverage of all relevant aspects, including racial microaggressions, internalized racism, and vicarious racial discrimination [9]. Only one study in the current investigation explored internalized racism [57]. Continuing to assess the extent to which racial discrimination impacts alcohol-related behaviors will require attention to the various types of racial discrimination.

Confounding or moderating variables.

Most studies only accounted for sex and/or age as confounding variables, thereby neglecting other variables potentially confounding the discrimination-alcohol association. Many studies did not assess socioeconomic status (SES), despite evidence that rates and types of racial discrimination [29] and alcohol use [58] vary across SES among Blacks. Ethnicity, nationality, and country of residence also warrant consideration in the association between racial discrimination and alcohol-related outcomes. Various ethnicities and nationalities exist within the Black race (e.g., Black African, African American, Black Caribbean, Afro-Latino) [59], with substantial differences in rates of racial discrimination and alcohol outcomes within Blacks [60–61]. All 27 studies were conducted with Black participants residing in the U.S., with only two reporting participant ethnicities [62, 63] and one explicitly including African-born immigrants [62]. Future studies of Black individuals should consider ethnicity/nationality compositions as a covariate or moderator in discrimination-alcohol associations. Replication in other countries is needed to investigate these associations within an international context.

Study designs.

Most studies included in this meta-analysis used a cross-sectional design. The few longitudinal studies included vary drastically by length of follow-up assessments (from 30 days to 13 years), precluding determination of optimal follow-up assessment intervals. Future studies would benefit from prospective study designs to resolve directionality of discrimination-alcohol associations and determine the optimal follow-up assessment interval to capture effects. Future research with experimental study designs may provide additional insight into the causal nature of the discrimination-alcohol relationship [64, 65].

Mechanisms.

Research investigating mechanisms by which racial discrimination impacts alcohol-related behaviors remains limited. Emerging research supports the role of affective (i.e., anger, depressive symptoms) and cognitive (i.e., coping motives) mediators in the association of racial discrimination and alcohol-related behaviors among Black college students [48; 49]. Notably, these studies were of cross-sectional designs, precluding assessment of causality and requiring replication with multi-wave prospective studies. Other potential mechanisms worth exploring include theoretically proximal antecedents of drinking behaviors (i.e., coping drinking motives, willingness to drink, and intention to drink [42]).

Clinical Implications

Culturally-specific interventions have been shown to be more successful than traditional interventions [68]. Treatment may aid with the emotional sequelae of discrimination (e.g., anger and aggression [69]) by validating individuals’ experiences while offering emotion regulation techniques. Clinicians may also encourage Black clients to obtain social support resources to cope with experiences of racial discrimination, as supportive social networks may provide a haven to share, explore, and heal from discrimination experiences [69]. While aforementioned approaches will not address the source of the problem (racial discrimination), unhealthy reactions may be improved.

Conclusion

Self-reported experiences of racial discrimination are positively associated with diverse alcohol-related behaviors among Black Americans, particularly with problematic alcohol use among younger individuals. This is the first meta-analysis to demonstrate associations of racial discrimination and diverse alcohol measures exclusively among Black Americans. There is a need for research exploring various forms of racial discrimination in relation to alcohol-related behaviors, as well as identifying mechanisms and protective factors to combat the detrimental effects of racial discrimination. This study contributes knowledge that may help remedy the disproportional experiences of negative drinking consequences faced by Blacks.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under award number R15 AA022496 to Aesoon Park.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest declaration (if none state ‘none’): None

References

- 1.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malone PS, Northrup TF, Masyn KE, Lamis DA, Lamont AE Initiation and persistence of alcohol use in United States Black, Hispanic, and White male and female youth. Addict Behav 2012; 37:299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caetano R Alcohol‐related health disparities and treatment‐related epidemiological findings among whites, blacks, and Hispanics in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003; 27:1337–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antai D, Lopez GB, Antai J, Anthony DS Alcohol drinking patterns and differences in alcohol-related harm: A population-based study of the United States. BIOMED RES INT 2014; 2014:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, & Zemore SE Disparities in alcohol‐related problems among White, Black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009; 33: 654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witbrodt J, Mulia N, Zemore SE, & Kerr WC Racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol-related problems: Differences by gender and level of heavy drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014; 38: 1662–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zapolski TC, Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM, & Smith GT Less drinking, yet more problems: Understanding African American drinking and related problems. Psychol Bull 2014; 140: 188–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark R Anderson NB, Clark VR, & Williams DR Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. Am Psychol 1999; 54: 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrell SP A multidimensional conceptualization of racism‐related stress: Implications for the wellbeing of people of color. Am J Orthopsychia 2000; 70: 42–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams DR, & Mohammed SA Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med 2009; 32:20–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pieterse AL, Todd NR, Neville HA, & Carter RT Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: A meta-analytic review. J Couns Psychol 2012; 59: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borrell LN, Roux AVD, Jacobs DR, Shea S, Jackson SA, Shrager S, & Blumenthal RS Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, smoking and alcohol consumption in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Prev Med 2010; 51: 307–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter RT, & Forsyth J Reactions to racial discrimination: Emotional stress and help-seeking behaviors. Psychol Trauma 2010; 2: 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaVeist TA, Rolley NC, & Diala C Prevalence and patterns of discrimination among US health care consumers. Int J Health Serv 2003; 33: 331–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pew Research Center. Discrimination and Racial Inequality [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/06/27/3-discrimination-and-racial-inequality/

- 16.Borrell LN, Kiefe CI, Diez-Roux AV, Williams DR, & Gordon-Larsen P Racial discrimination, racial/ethnic segregation, and health behaviors in the CARDIA study. Ethnic Health, 2013; 18: 227–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zemore SE, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Keithly S, & Mulia N Racial prejudice and unfair treatment: Interactive effects with poverty and foreign nativity on problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2011; 72: 361–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson AB, Goodman MS, & Kwate NOA Does learning about race prevent substance abuse? Racial discrimination, racial socialization and substance use among African Americans. Addict Behav 2016; 61: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caldwell CH, Antonakos CL, Tsuchiya K, Assari S, & De Loney EH Masculinity as a moderator of discrimination and parenting on depressive symptoms and drinking behaviors among nonresident African-American fathers. Psychol Men Masculin 2013; 14: 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Respress BN, Small E, Francis SA, & Cordova D The role of perceived peer prejudice and teacher discrimination on adolescent substance use: A social determinants approach. J Ethn Subst Abuse 2013; 12: 279–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, & Kelly Y A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Soc Sci Med 2013; 95: 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.English D, Lambert SF, Evans MK, & Zonderman AB Neighborhood racial composition, racial discrimination, and depressive symptoms in African Americans. Am J Commun Psychol 2014; 54: 219–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurd NM, Varner FA, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA Does perceived racial discrimination predict changes in psychological distress and substance use over time? An examination among Black emerging adults. Dev Psychol 2014; 50: 1910–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwate NOA, & Goodman MS Racism at the intersections: Gender and socioeconomic differences in the experience of racism among African Americans. Am J Orthopsychia 2015; 85: 397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borrell LN, Jacobs DR, Williams DR, Pletcher MJ, Houston TK, & Kiefe CI Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Adults Study. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 166: 1068–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Factor R, Williams DR, & Kawachi I Social resistance framework for understanding high-risk behavior among nondominant minorities: Preliminary evidence. Am J Public Health 2013; 103: 2245–2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madkour AS, Jackson K, Wang H, Miles TT, Mather F, & Shankar A Perceived discrimination and heavy episodic drinking among African-American youth: Differences by age and reason for discrimination. J Adolescent Health 2015; 57: 530–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brondolo E, Rieppi R, Kelly KP, & Gerin W Perceived racism and blood pressure: a review of the literature and conceptual and methodological critique. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2003; 25: 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, … & Gee G. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one 2015; 10: e0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carter RT, Lau MY, Johnson V, & Kirkinis K Racial discrimination and health outcomes among racial/ethnic minorities: A meta‐analytic review. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development 2017; 45: 232–259. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilbert PA, & Zemore SE Discrimination and drinking: A systematic review of the evidence. Social Science & Medicine 2016; 161: 178–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The Prisma Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ewing JA Detecting alcoholism: The CAGE Questionnaire. J Am Med Assoc 1984; 252: 1905–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Babor TF, Biddle-Higgins JC, Saunders JB, & Monteiro MG AUDIT: The alcohol use disorders identification test: Guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR Introduction to MetaAnalysis West Sussex, UK: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB Practical Meta-Analysis: Applied Social Research Methods Series Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Joanna Briggs Institute. System for the Unified Management of the Review and Assessment of Information. [Updated 2016; cited 2018]. Available from http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html

- 38.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DerSimonian R, & Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control clin trials 1986; 7:177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, & Minder C Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witbrodt J, Mulia N, Zemore SE, Kerr WC Racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol‐related problems: Differences by gender and level of heavy drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014; 38:1662–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, & Mudar P Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995; 69: 990–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sher KJ Stress response dampening In Blane HT & Leonard K, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. New York: Guilford; 1987. p. 227–271. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dawson DA, Grant BF, & Ruan WJ The association between stress and drinking: modifying effects of gender and vulnerability. Alcohol Alcoholism 2005; 40: 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harford TC, Yi HY, & Grant BF The five-year diagnostic utility of “diagnostic orphans” for alcohol use disorders in a national sample of young adults. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2010; 71: 410–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blazer DG, & Wu LT The epidemiology of alcohol use disorders and subthreshold dependence in a middle-aged and elderly community sample. Am J Geriat Psychiat 2011; 19: 685–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bradley KA, Boyd-Wickizer J, Powell SH, & Burman ML Alcohol screening questionnaires in women: A critical review. Jama 1998; 280: 166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boynton MH, O’Hara RE, Covault J, Scott D, & Tennen H A mediational model of racial discrimination and alcohol-related problems among African American college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2014; 75: 228–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Desalu JM, Kim J, Zaso MJ, Corriders SR, Loury JA, Minter ML, & Park A Racial discrimination, binge drinking, and negative drinking consequences among black college students: serial mediation by depressive symptoms and coping motives. Ethnic Health 2017; 38: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’hara RE, Armeli S, Scott DM, Covault J, & Tennen H Perceived racial discrimination and negative-mood–related drinking among African American college students. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs 2015; 76: 229–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hurd NM, Varner FA, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA Does perceived racial discrimination predict changes in psychological distress and substance use over time? An examination among Black emerging adults. Developmental psychology 2014; 50: 1910–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanders‐Phillips K, Kliewer W, Tirmazi T, Nebbitt V, Carter T, & Key H Perceived racial discrimination, drug use, and psychological distress in African American youth: A pathway to child health disparities. Journal of Social Issues 2014; 70: 279–297. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kressin NR, Raymond KL, & Manze M Perceptions of race/ethnicity-based discrimination: A review of measures and evaluation of their usefulness for the health care setting. J Health Care Poor U 2008; 19: 697–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mulia N, & Zemore SE Social adversity, stress, and alcohol problems: are racial/ethnic minorities and the poor more vulnerable? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2012; 73: 570–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, & Barbeau EM Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med 2005; 61: 1576–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shariff-Marco S, Breen N, Landrine H, Reeve BB, Krieger N, Gee GC, … & Liu B. Measuring everyday racial/ethnic discrimination in health surveys. Du Bois Rev 2009; 8: 159–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor J, & Jackson B Factors affecting alcohol consumption in black women. Part II. International Journal of the Addictions 1990; 25: 1415–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lo CC, & Cheng TC Race, employment disadvantages, and heavy drinking: A multilevel model. J Psychoactive Drugs 2015; 47: 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agyemang C, Bhopal R, & Bruijnzeels M Negro, Black, Black African, African Caribbean, African American or what? Labelling African origin populations in the health arena in the 21st century. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2005; 59: 1014–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibbs TA, Okuda M, Oquendo MA, Lawson WB, Wang S, Thomas YF, & Blanco C Mental health of African Americans and Caribbean blacks in the United States: results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. American journal of public health 2013; 103: 330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clark TT, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, & Whitfield KE Everyday discrimination and mood and substance use disorders: A latent profile analysis with African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Addictive Behaviors 2015; 40: 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tran AG, Lee RM, & Burgess DJ Perceived discrimination and substance use in Hispanic/Latino, African-born Black, and Southeast Asian immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 2010; 16: 226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hunte HE, & Barry AE Perceived discrimination and DSM-IV–based alcohol and illicit drug use disorders. American Journal of Public Health 2012; 102: e111–e117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gerrard M, Stock ML, Roberts ME, Gibbons FX, O’hara RE, Weng CY, & Wills TA Coping with racial discrimination: The role of substance use. Psychol Addict Behav 2012; 26: 550–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richman LS, Boynton MH, Costanzo P, & Banas K Interactive effects of discrimination and racial identity on alcohol-related thoughts and use. Basic Appl Soc Psych 2013; 35: 396–407. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Metcalfe J & Mischel W A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower. Psychol Rev 1999; 106: 3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gibbons FX, O’hara RE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng CY, & Wills TA The erosive effects of racism: Reduced self-control mediates the relation between perceived racial discrimination and substance use in African American adolescents. J Pers Soc Psychol 2012; 102: 1089–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Griner D & Smith TB Culturally adapted mental health intervention: A meta-analytic review. Psychother: Theor, Res 2006; 43: 531–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Richman LS & Leary MR Reactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism, and other forms of interpersonal rejection: A multimotive model. Psychol Rev 2013; 116: 365–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Linehan M Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bogart LM, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Klein DJ, Davies SL, Cuccaro PM, … & Schuster MA Association between perceived discrimination and racial/ethnic disparities in problem behaviors among preadolescent youths. Am J Public Health 2013; 103: 1074–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gibbons FX, Kingsbury JH, Weng CY, Gerrard M, Cutrona C, Wills TA, & Stock M Effects of perceived racial discrimination on health status and health behavior: A differential mediation hypothesis. Health Psychology 2014; 33: 11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kwate NOA, Meyer IH, Eniola F, & Dennis N Individual and group racism and problem drinking among African American women. Journal of Black Psychology 2010; 36: 446–457. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kwate NOA, Valdimarsdottir HB, Guevarra JS, & Bovbjerg DH Experiences of racist events are associated with negative health consequences for African American women. Journal of the National Medical Association 2003; 95: 450–460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Keyes KM Responses to discrimination and psychiatric disorders among Black, Hispanic, female, and lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. American Journal of Public Health 2010; 100: 1477–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith SM, & Taylor J The relationship between social stress and substance use among Black youths residing in South Florida. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse 2015; 24: 372–378. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Squires LE, Palfai TP, Allensworth-Davies D, Cheng DM, Bernstein J, Kressin N, & Saitz R Perceived discrimination, racial identity, and health behaviors among black primary-care patients who use drugs. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse 2017; 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yen IH, Ragland DR, Greiner BA, & Fisher JM Workplace discrimination and alcohol consumption: Findings from the San Francisco Muni Health and Safety Study. Ethnicity & Disease 1999a; 9: 70–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yen IH, Ragland DR, Greiner BA, & Fisher JM Racial discrimination and alcohol-related behavior in urban transit operators: Findings from the San Francisco Muni Health and Safety Study. Public Health Reports 1999b; 114: 448–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.