Abstract

Objective

This pivotal phase III study, SIAXI, investigated the efficacy and safety of incobotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of chronic sialorrhea due to Parkinson disease (PD), atypical parkinsonism, stroke, or traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Methods

Adult patients with PD (70.7%), atypical parkinsonism (8.7%), stroke (19.0%), or TBI (2.7%) were randomized (2:2:1) to double-blind treatment with placebo (n = 36), or total doses of incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U (n = 74) or 100 U (n = 74), in a single treatment cycle. The coprimary endpoints were change in unstimulated salivary flow rate from baseline to week 4, and patients' Global Impression of Change Scale score at week 4. Adverse events were recorded throughout.

Results

A total of 184 patients were randomized. Both incobotulinumtoxinA dose groups showed reductions in mean unstimulated salivary flow rate at week 4, with a significant difference vs placebo in the incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U group (p = 0.004). Patients' Global Impression of Change Scale scores also improved at week 4, with a significant difference vs placebo in the incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U group (p = 0.002). A lasting effect was observed at week 16 post injection. The most frequent treatment-related adverse events in the incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U and 100 U groups were dry mouth (5.4% and 2.7% of patients) and dysphagia (2.7% and 0.0% of patients).

Conclusions

IncobotulinumtoxinA 100 U is an effective and well-tolerated treatment of chronic sialorrhea in adults.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

NCT02091739.

Classification of evidence

This study provides Class I evidence that incobotulinumtoxinA reduces salivary flow rates in patients with chronic sialorrhea due to PD, atypical parkinsonism, stroke, or TBI.

Intractable sialorrhea (drooling; overflowing saliva from the mouth, over the lip margin, or through the pharynx) is a troublesome and disabling symptom resulting from various causes, such as swallowing problems or an inability to retain saliva in the mouth. Sialorrhea is frequently associated with underlying diseases including cerebral palsy,1 Parkinson disease (PD),2,3 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS),4 traumatic brain injury (TBI),5 stroke, and various degenerative brain disorders.6

Prevalence rates for sialorrhea in patients with PD range from 32% to 74%.3 The effects of sialorrhea range from adverse effects on caregiver quality of life7 and patient quality of life, ranging from difficulty eating and speaking with social and emotional consequences,2,8,9 to an increased risk of morbidity and mortality associated with perioral skin breakdown and aspiration pneumonia.10 Treatment approaches are based on multidisciplinary management of drooling and, at the time this study was conducted, no pharmacologic agents had US Food and Drug Administration or European Medicines Agency approval for the treatment of chronic sialorrhea in adults. However, botulinum neurotoxin type A (BoNT/A) had been effectively used to reduce saliva production in patients with sialorrhea since 1999,11,12 and numerous studies had demonstrated the safety and efficacy of BoNT/A and /B formulations for sialorrhea in patients with PD and ALS.13–22 This pivotal phase III study investigated the efficacy and safety of incobotulinumtoxinA (75 U and 100 U) for the treatment of sialorrhea due to PD, atypical parkinsonism, stroke, or TBI. Results from a single treatment cycle in the placebo-controlled main period (MP) are reported.

Methods

Study design

SIAXI (Sialorrhea in Adults Xeomin Investigation) was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter study conducted over 33 sites (12 sites in Germany and 21 sites in Poland).

After an initial clinical screening visit to determine the patient's eligibility for inclusion in the study, patients were randomly assigned (2:2:1) in a double-blind manner (using an interactive web response system) to receive total doses of incobotulinumtoxinA (BoNT/A free from complexing proteins; Xeomin, Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) 75 U or 100 U or placebo in a single treatment (MP), and incobotulinumtoxinA doses of 75 U or 100 U in 3 further treatments (extension period) at 16-week intervals, each of them followed by regular monitoring during 16 ± 2 weeks of observation for a total of 64 weeks. Only the data from the placebo-controlled MP are presented here.

In each cycle, treatment was administered in 4 injections, bilaterally into the parotid and submandibular salivary glands (one injection for each gland, guided by ultrasound23 or anatomical landmarks) as follows:

In the 75 U group, 22.5 U (0.6 mL) and 15 U (0.4 mL), respectively, per side

In the 100 U group, 30 U (0.6 mL) and 20 U (0.4 mL), respectively, per side

Equivalent volumes were injected into each gland in the placebo group. Placebo contained excipients of incobotulinumtoxinA injection, sucrose, and human serum albumin to control for any physiologic effects of these carrier molecules in the standard incobotulinumtoxinA preparation.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The study was registered in the database of the US National Library of Medicine (clinicaltrials.gov), record number NCT02091739, and the EU Clinical Trials Register (eudract.ema.europa.eu/), EudraCT record number 2012-005539-10, and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol, informed consent forms, and other study-related documents were reviewed and approved by the local independent ethics committees and institutional review boards. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients; if patients were physically unable to give written consent, oral consent was confirmed in writing by an impartial witness.

Study population

Adult patients with a documented diagnosis (≥6 months prior to screening) of idiopathic or familial PD (according to the United Kingdom Parkinson's Disease Brain Bank [parkinsons.org.uk] diagnostic criteria), atypical parkinsonism (comprising multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, or corticobasal degeneration), stroke, or TBI were included in this study. Patients were required to have chronic troublesome sialorrhea related to their primary neurologic diagnosis continuously for ≥3 months prior to screening, defined as a Drooling Severity and Frequency Scale (DSFS) sum score of ≥6 points; a score of ≥2 points for each item of the DSFS; and a score of ≥3 points on the modified Radboud Oral Motor Inventory for Parkinson's Disease (mROMP) drooling Item A at screening and baseline. In addition, patients were required to have a score of ≤2 and ≤3 points on the mROMP swallowing symptoms Items A and C, respectively, at screening and baseline. The original ROMP questionnaire24 was developed by the Radboud University Medical Centre in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, and was modified to implement small changes in wording (to extend the use of the scale in patients with sialorrhea in general, including those with stroke and TBI) resulting from patient interviews during linguistic validation in US English. mROMP is a 24-item inventory in which the domains of speech symptoms, swallowing symptoms, and drooling are assessed using a 5-point Likert scale. Permission to use the questionnaire for this study was granted by the Radboud University Medical Centre. Results of the analysis of mROMP data are reported separately.

The main exclusion criteria were secondary causes of sialorrhea other than parkinsonism, stroke, or TBI; drug treatment for sialorrhea within 4 weeks prior to baseline or planned during the MP; unstable concomitant medication that may influence sialorrhea; changes to antiparkinsonian medication within 4 weeks of screening; a history of recurrent aspiration pneumonia; prior recent treatment with, or hypersensitivity to, BoNT (within 1 year for sialorrhea or 14 weeks for other indications); and surgery (previous or planned) for sialorrhea.

Outcome measures

The coprimary endpoints were the change in unstimulated salivary flow rate (uSFR) from study baseline to week 4, and the patients' Global Impression of Change Scale (GICS) score at week 4. The change in uSFR from study baseline to weeks 8 and 12, and patients' GICS score at weeks 1, 2, 8, and 12 were assessed as secondary endpoints. The change in uSFR from study baseline to week 16 and patients' GICS score at week 16 were assessed as other efficacy variables.

Unstimulated salivary flow rate

The uSFR was measured from direct saliva collection using the swab method. Briefly, 1 hour before the measurement, the patient's teeth were brushed and the patient was not allowed to eat or smoke until after the measurement had been taken. Patients were offered a drink of mineral water 30 minutes before the measurement.

For the measurement, 4 adsorbent Salimetrics Oral Swabs (2-mL capacity; Salimetrics, Carlsbad, CA) were placed at the orifices of the salivary glands (between cheek and gum, and between tongue and gum at each side of the mouth) and left for 5 minutes to absorb the saliva produced. The weight increase of the swabs was used to calculate the salivary flow rate in grams/minute (based on a precision of 0.01 g and a real-time duration in minutes and seconds). The procedure was repeated after 30 minutes and the average of 2 results was calculated.

Global Impression of Change Scale

The patients' and carers' GICS score was measured on a 7-point Likert scale that ranged from −3 (very much worse) to +3 (very much improved) in response to the following self-administered questions:

For patients: “Compared to how you were doing just before the last injection into your salivary gland, what is your overall impression of how you are functioning now as a result of this treatment?”

For caregivers: “Compared to how the patient was doing just before the last injection into his/her salivary gland, what is your overall impression of how he/she is functioning now as a result of this treatment?”

Other endpoints

Investigators rated the change in drooling severity and frequency from study baseline to all posttreatment visits using the DSFS.25 DSFS comprises 2 subscales for drooling severity, measured on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (dry; never drools) to 5 (profuse; hands, tray, and objects wet) and drooling frequency, measured on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (constantly). The DSFS sum score was calculated from the sum of the 2 subscales, maximum score 9.

The occurrence of adverse events (AEs), AEs related to treatment, AEs of special interest (AESIs) possibly indicative of toxin spread, and serious AEs, based on MedDRA (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities) version 19.1, was recorded.

Statistical analysis

A total of 180 treatment-naive patients were planned to be randomized in order to achieve 95% power to show a statistically significant difference between the active treatment groups and placebo for both of the coprimary endpoints and to have at least 100 patients treated with incobotulinumtoxinA and observed over 1 year (anticipating a 30% dropout rate over 1 year).

Efficacy analyses were based on the full analysis set, defined as all patients who were treated and had at least a baseline value for uSFR. Safety data were based on the safety evaluation set, defined as all patients who received incobotulinumtoxinA or placebo during the MP, and analyzed using descriptive statistics.

A fixed-sequence test procedure was performed for the coprimary efficacy variables, first comparing the incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U treatment group with placebo, followed by comparison of the 75 U group with placebo if results of the first tests were significant. Changes from baseline in coprimary and secondary efficacy variables were assessed by a mixed model repeated measurement (MMRM) analysis; p values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Independent variables were defined as treatment group, etiology, use of ultrasound injection guidance, country and sex as fixed factor, visit * treatment as interaction term, and visit as repeated factor. The DSFS sum score was analyzed analogously to the coprimary efficacy variables.

Confirmatory analyses were conducted using comparison of least squares means (LS-means) of the MMRM model, and sensitivity analyses were performed using analysis of covariance models and nonparametric tests.

Classification of evidence

This prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study assessed the efficacy and safety of incobotulinumtoxinA (75 and 100 U) for reduction of salivary flow rate, and severity and frequency of chronic, troublesome sialorrhea. This study provides Class I evidence that incobotulinumtoxinA reduces salivary flow rates in patients with chronic sialorrhea due to PD, atypical parkinsonism, stroke, or TBI.

Data availability

No individual deidentified participant data are shared. Key elements of the study protocol, study design, and statistical analysis plan were deposited in the database of the US National Library of Medicine, record number NCT02091739, and the EU Clinical Trials Register, EudraCT record number 2012-005539-10. All relevant information is contained within this report and supplemental materials.

Results

Study population

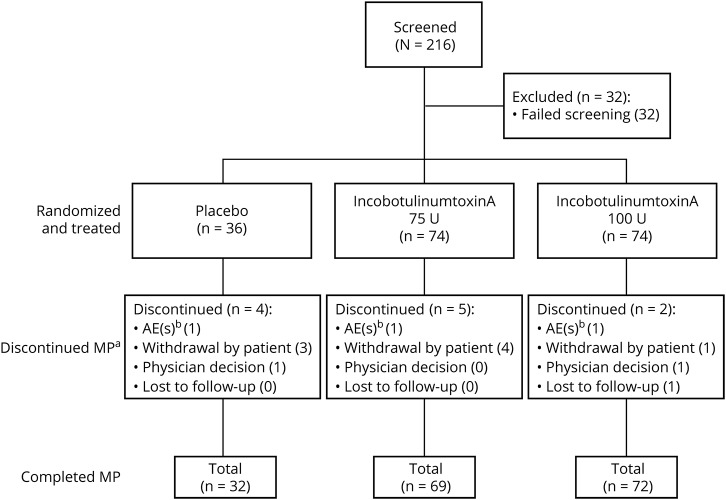

A total of 184 patients were randomized in the study and received either placebo (n = 36), or incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U (n = 74) or 100 U (n = 74) (figure 1). Overall, 11 patients (6.0%) discontinued and 173 patients (94.0%) completed the MP. The reasons for discontinuation were withdrawal by patient (n = 8), AEs not related to treatment (n = 3), physician decision (n = 2), and/or lost to follow-up (n = 1); multiple reasons for withdrawal could be listed (figure 1).

Figure 1. Disposition of patients for the MP of the study.

An AE leading to discontinuation occurring in one placebo patient was not considered a treatment-emergent AE (AE with onset or worsening at or after treatment). aMultiple reasons for withdrawal could be listed; bAEs were not treatment-related. AE = adverse event; MP = main period.

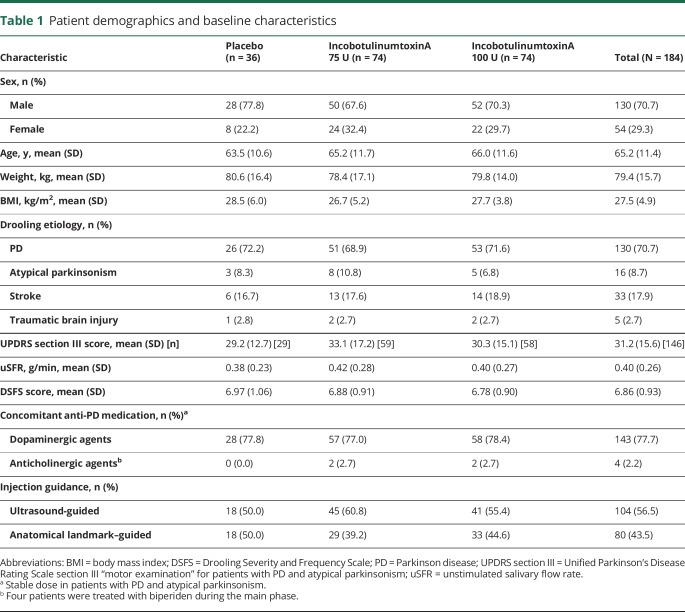

Baseline characteristics for each treatment group and the total population are summarized in table 1. Drooling etiology and baseline demographics were similar in all treatment groups. Most patients (130 [70.7%]) had sialorrhea due to PD; sialorrhea was due to atypical parkinsonism, stroke, and TBI in 16 (8.7%), 33 (17.9), and 5 (2.7%) patients, respectively. Among 146 patients with PD or atypical parkinsonism, the mean (SD) Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale section III “motor examination” score was 31.2 (15.6) at baseline, indicating moderate to severe impairment. The salivary flow rate was in the normal expected range for this patient population: at baseline, the mean (SD) uSFR was 0.40 (0.26) g/min and the mean (SD) DSFS score was 6.86 (0.93) (table 1) indicating moderate to severe troublesome sialorrhea on average.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

Salivary glands were localized and injections were administered using ultrasound guidance in 56.5% of patients in the total population and at least 50.0% in each treatment group, with no difference in baseline demographics or severity of sialorrhea in patients who received ultrasound or anatomical landmark–guided injection (data not shown).

As expected in this patient population, the most frequent comorbidities in the placebo, incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, and incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U groups were nervous system disorders (94.4%, 94.6%, and 87.8%, respectively), vascular disorders (61.1%, 58.1%, and 56.8%, respectively), metabolism and nutrition disorders (38.9%, 52.7%, and 41.9%, respectively), and musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (41.7%, 41.9%, and 41.9%, respectively).

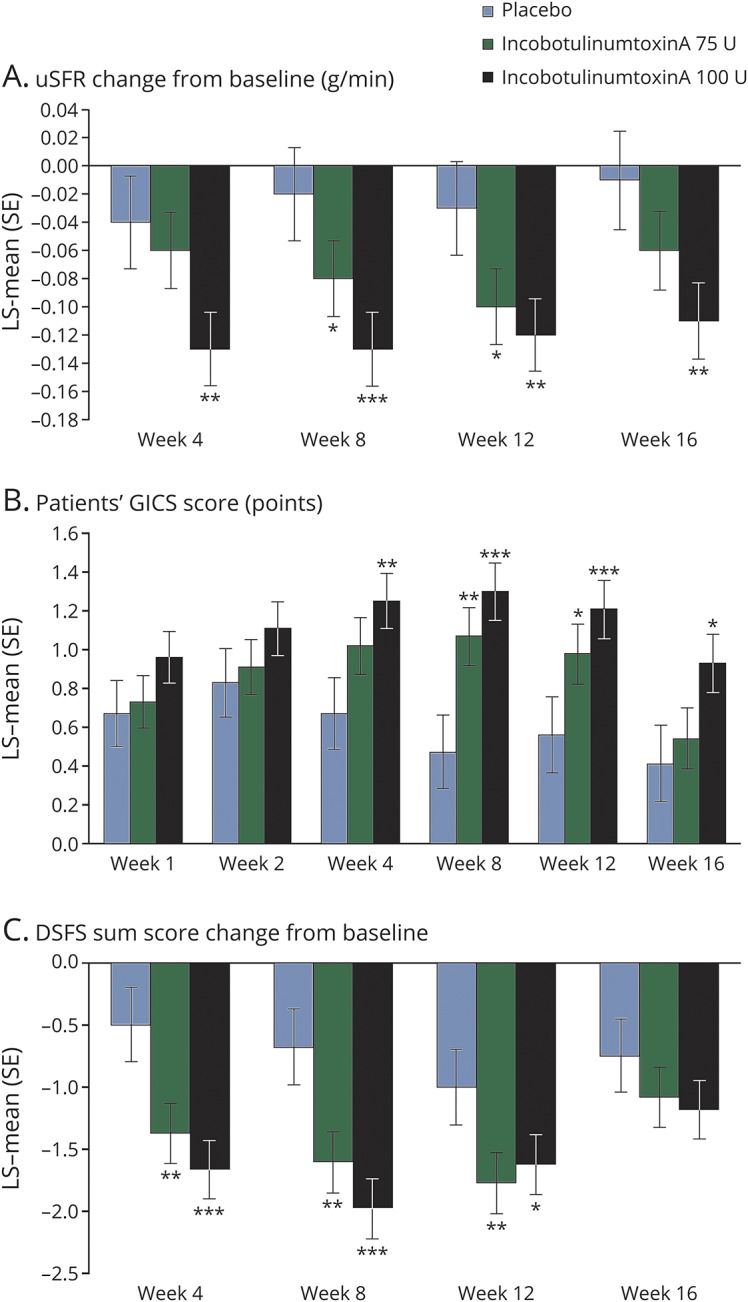

Unstimulated salivary flow rate

Compared with placebo, both active treatment groups showed a numerical reduction in mean uSFR at week 4 (figure 2A). From baseline to 4 weeks post treatment, the LS-mean (standard error [SE]) difference vs placebo was −0.02 (0.030; p = 0.542, MMRM analysis) and −0.09 (0.031; p = 0.004, MMRM analysis) g/min in the incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U and incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U groups, respectively. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the efficacy of the 100 U dose. The use of ultrasound guidance, included as an independent variable in statistical analysis, did not confound results.

Figure 2. Clinical outcomes over time.

(A) Change in uSFR from baseline to weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16; (B) patients' GICS score at weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16; and (C) change in DSFS sum score from baseline to weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16 post treatment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, mixed model repeated measurement analysis based on change from baseline vs placebo in panels A and C, and the rating at each posttreatment assessment vs placebo in panel B. Reduction in uSFR and DSFS indicates improvement. GICS score: −3 (very much worse), −2 (much worse), −1 (minimally worse), 0 (no change in function), +1 (minimally improved), +2 (much improved) to +3 (very much improved). DSFS = Drooling Severity and Frequency Scale; GICS = Global Impression of Change Scale; LS-mean = least squares mean; SE = standard error; uSFR = unstimulated salivary flow rate.

Secondary analyses revealed reductions in uSFR from baseline to 8 and 12 weeks post treatment in both active treatment groups (figure 2A). Significant reductions in uSFR compared with placebo were noted in both active treatment groups at week 8 (LS-mean [SE] difference vs placebo: incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, −0.07 [0.029] g/min; p = 0.022, and incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U, −0.12 [0.030] g/min; p < 0.001, MMRM analysis) and week 12 (LS-mean [SE] difference vs placebo: incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, −0.07 [0.031] g/min; p = 0.019, and incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U, −0.09 [0.031] g/min; p = 0.004, MMRM analysis). In patients treated with incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U, significant reductions vs placebo were maintained at the last observation point at week 16 (LS-mean [SE] difference vs placebo: incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, −0.04 [0.033] g/min; p = 0.180, and incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U, −0.10 [0.033] g/min; p = 0.002, MMRM analysis) (figure 2A).

GICS score

Compared with placebo, both active treatment groups showed greater improvement as measured by patients' GICS score at week 4 (figure 2B). The LS-mean (SE) difference vs placebo was 0.35 (0.181; p = 0.055, MMRM analysis) and 0.58 (0.183; p = 0.002, MMRM analysis) in the incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U and 100 U groups, respectively. Sensitivity analyses supported these results. The use of ultrasound guidance, included as an independent variable in statistical analysis, did not confound results.

Secondary analyses showed improvement with incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U vs placebo at 1 and 2 weeks post treatment as measured by patients' GICS score. Significant improvements vs placebo were shown in both active treatment groups at week 8 (LS-mean [SE] difference vs placebo: incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, 0.61 [0.190]; p = 0.002, and incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U, 0.84 [0.192]; p < 0.001, MMRM analysis) and week 12 (LS-mean [SE] difference vs placebo: incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, 0.42 [0.200]; p = 0.035, and incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U, 0.65 [0.201]; p = 0.001, MMRM analysis). In patients treated with incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U, significant improvements vs placebo were maintained at the last observation point at week 16 (LS-mean [SE] difference vs placebo: incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, 0.13 [0.203]; p = 0.531, and incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U, 0.52 [0.203]; p = 0.011, MMRM analysis) (figure 2B).

DSFS sum score

Significant improvements from baseline in DSFS sum score compared with placebo were noted in both active treatment groups at week 4 (LS-mean [SE] difference vs placebo: incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, −0.88 [0.275]; p = 0.002, and incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U, −1.17 [0.278]; p < 0.001, MMRM analysis; figure 2C). Significant improvements vs placebo were maintained at week 8 (LS-mean [SE] difference vs placebo: incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, −0.93 [0.289]; p = 0.002, and 100 U, −1.29 [0.291]; p < 0.001, MMRM analysis) and week 12 post treatment (LS-mean [SE] difference vs placebo: incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, −0.77 [0.284]; p = 0.008, and 100 U, −0.63 [0.286]; p = 0.030, MMRM analysis) (figure 2C).

Safety

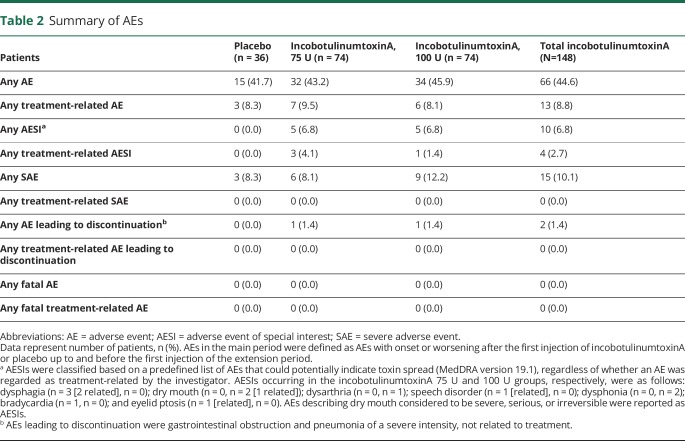

AEs were reported in 15 (41.7%), 32 (43.2%), and 34 (45.9%) patients in the placebo, incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, and 100 U groups, respectively. Serious AEs, none of which were deemed to be related to treatment, were reported in 3 (8.3%), 6 (8.1%), and 9 (12.2%) patients, respectively.

AEs that were deemed to be related to treatment occurred in 3 (8.3%), 7 (9.5%), and 6 (8.1%) patients in the placebo, incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U, and 100 U groups, respectively (table 2); all were nonserious and of mild or moderate intensity. The most frequent treatment-related AEs were dry mouth (occurring in 4 [5.4%] and 2 [2.7%] patients in the incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U and 100 U groups, respectively) and dysphagia (occurring in 2 [2.7%] patients in the incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U group and no patients in the 100 U group). All patients who experienced treatment-related dry mouth and treatment-related dysphagia had sialorrhea due to PD. No patients receiving concomitant anticholinergic medication reported dry mouth.

Table 2.

Summary of AEs

Five patients each (6.8%) in the incobotulinumtoxinA 75 U and 100 U groups experienced AESIs, including dysphagia (3 patients [4.1%] in the 75 U group), dry mouth and dysphonia (2 patients each [2.7%] in the 100 U group), dysarthria (1 patient [1.4%] in the 100 U group), speech disorder, bradycardia, and eyelid ptosis (one patient each [1.4%] in the 75 U group). Of these, 2 events of dysphagia, and one of dry mouth, speech disorder, and eyelid ptosis were deemed related to treatment. One event each of dysphonia and dysarthria were of severe intensity but not deemed related to treatment. No patients in the placebo group experienced AESIs. All patients who experienced dysphagia as an AESI had PD, and 2 of the 3 patients had preexisting dysphagia.

AEs led to discontinuation in 2 patients: pneumonia in one patient in the 75 U group and gastrointestinal obstruction in one patient in the 100 U group. Both events were of severe intensity, were not related to treatment, and were resolved with sequelae (gastrostomy and tracheotomy, and substantial problems walking following surgery for inguinal hernia, respectively) at the end of the study. No fatal events occurred.

Discussion

The results presented here provide Level I evidence in support of incobotulinumtoxinA as an effective targeted treatment for chronic sialorrhea in adults. The reduction in uSFR and improvement in GICS score compared with placebo 4 weeks post treatment (coprimary endpoints) reached statistical significance for the incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U group, with efficacy confirmed by secondary and other endpoints. In addition, both doses of incobotulinumtoxinA (75 U and 100 U) were well tolerated, with a similar incidence of treatment-related AEs to the placebo group. These data led to the recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U for the treatment of chronic sialorrhea in adult patients.26

Until recently, treatment approaches were based on a multidisciplinary management of symptoms, including speech therapy, oral motor training, swallowing training, oral anticholinergics, and BoNT injections in the salivary glands to reduce the amount of saliva produced daily.27–29 In therapy-resistant cases, irradiation or salivary gland surgery can be used to reduce functional salivary gland tissue or to relocate salivary ducts.27 Anticholinergics, used to reduce the motor symptoms of PD, reduce saliva production by inhibiting the action of acetylcholine at muscarinic receptors. For example, glycopyrrolate is recommended for the treatment of sialorrhea for up to 1 week.29 However, the nonspecific, systemic activity of these treatments is associated with frequently observed adverse effects (including cognitive impairment, drowsiness, and urinary retention), limiting their use for the treatment of chronic sialorrhea.27,29 Following positive reports of BoNT/A in the treatment of sialorrhea,17,18 the efficacy and safety of incobotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of sialorrhea of various causes has been investigated in small pilot studies or case reports.30–34

The findings of this large, pivotal, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study are consistent with those of previous small exploratory studies that showed a reduction of sialorrhea in adults with neurologic disorders including PD and ALS treated with onabotulinumtoxinA, at a mean dose of 76.6 U per patient18 or 50 U per parotid gland,15 incobotulinumtoxinA at ≤100 U,31,32 or onabotulinumtoxinA or incobotulinumtoxinA up to 100 U total dose into 2, 3, or 4 glands.35 A similar subjective improvement in sialorrhea measured by DSFS was reported in a placebo-controlled study of 36 patients with advanced-phase PD treated with rimabotulinumtoxinB 4,000 U.16 Conversely, a recent small crossover study reported a lack of superiority of incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U vs placebo 1 month post injection for treatment of drooling in patients with PD.36 However, we have shown persistence of efficacy at week 16 post injection, suggesting that a crossover design may not be appropriate within this time frame.

In the present study, treatment with incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U resulted in improvement in sialorrhea symptoms measured by uSFR, GICS, and DSFS 4 weeks post treatment that was greater than placebo and maintained at weeks 8 and 12. A lasting effect greater than placebo was also observed at week 16 (the last observation point in the MP), suggesting a duration of efficacy of incobotulinumtoxinA of at least 16 weeks and benefit to the patient that may extend beyond 4 months after the initial injection. The results of a similarly designed placebo-controlled study showed significant improvement from baseline vs placebo in uSFR and global impression of change, measured using the Clinical Global Impression of Change scale, 4 weeks post treatment with 2,500 U or 3,500 U rimabotulinumtoxinB.37 The authors noted that significant improvements in uSFR (measured by collection of expectorated saliva in preweighed paper cups, rather than by direct collection using absorbent swabs as in the present study) in those treated with 3,500 U, and differences in the Clinical Global Impression of Change in those treated with 2,500 U, were maintained up to week 13.37

In the present study, the effects of incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U were clear for the coprimary endpoints; the efficacy of the 75 U dose was less pronounced and may be delayed, reaching a response threshold at a later time point, compared with the 100 U dose. Significant improvements in uSFR and differences in patients' GICS score occurred at 8 and 12 weeks post treatment, potentially indicating a dose-dependent efficacy profile and a viable treatment option in clinical practice.

This pivotal phase III study showed that incobotulinumtoxinA (75 U and 100 U) was well tolerated for the treatment of sialorrhea in neurologic disorders. Treatment-related AEs occurred at a similar frequency in patients who received placebo and incobotulinumtoxinA 75 and 100 U. The most frequently observed treatment-related AEs in the active treatment groups were dry mouth and dysphagia, which occurred at low frequency despite being common complications in patients with PD.28,38,39 The slightly higher incidence of dry mouth and dysphagia in the 75 U group compared with 100 U may reflect the patients' underlying medical history and preexisting conditions. Of note, patients on concomitant anticholinergics did not report dry mouth; an additive effect was not obvious. Furthermore, there was no increased incidence of AESIs potentially indicative of toxin spread with increasing incobotulinumtoxinA dose, and no new safety concerns were reported.

The strengths of the current study include the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study design and the inclusion of 2 incobotulinumtoxinA doses. One limitation of the present study was the patient selection. It was initially intended that the study population should contain at least 20% of patients from each of the etiologic subgroups (PD and atypical parkinsonism; stroke; TBI) and specialized study centers were selected to achieve this balance. However, patients with non-PD neurologic conditions, such as atypical parkinsonism disorders (including multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy), may experience a wider spectrum of other symptoms, decreased mobility, and falls40 that may affect their participation in such studies. Therefore, as incobotulinumtoxinA treatment for sialorrhea is not specific to a particular disease type, and to achieve the planned sample size, this initial restriction was not enforced, and hence, as expected, the majority of patients had sialorrhea due to PD. Low numbers of patients with sialorrhea due to stroke or ALS were also included in previous small pilot studies.31,32

The data presented here support the utility of incobotulinumtoxinA 100 U as an effective and well-tolerated treatment of chronic sialorrhea in adult patients. The high remaining efficacy at 16 weeks post injection suggests a duration of efficacy and benefit to the patients lasting at least 16 weeks.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the patients and study investigators. Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was funded by Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

Glossary

- AE

adverse event

- AESI

adverse event of special interest

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- BoNT

botulinum neurotoxin

- DSFS

Drooling Severity and Frequency Scale

- GICS

Global Impression of Change Scale

- LS-means

least squares means

- MMRM

mixed model repeated measurement

- MP

main period

- mROMP

modified Radboud Oral Motor Inventory for Parkinson's Disease

- PD

Parkinson disease

- SIAXI

Sialorrhea in Adults Xeomin Investigation

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- uSFR

unstimulated salivary flow rate

Footnotes

Class of Evidence: NPub.org/coe

Author contributions

W.H. Jost, A. Friedman, J. Slawek, B. Flatau-Baqué, J. Csikós, and A. Blitzer were involved in the study concept and design, and the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of study data. They have also been involved in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. O. Michel, C. Oehlwein, A. Bogucki, S. Ochudlo, M. Banach, and F. Pagan were involved in the acquisition and interpretation of study data, and have been involved in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. C.J. Cairney was involved in the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final version for submission.

Study funding

This study was supported by Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Disclosure

W.H. Jost was the principal investigator in the SIAXI study and served as a consultant for AbbVie, Allergan, Bial, Ipsen, Merz Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and Zambon. A. Friedman was an investigator in the SIAXI study and served as a consultant for AbbVie, GE, and Roche. O. Michel was a Data Safety Monitoring Committee member in the SIAXI study and served as a speaker for Merz Pharmaceuticals. C. Oehlwein was an investigator in the SIAXI study and reports no other disclosures. J. Slawek was an investigator in the SIAXI study and served as a consultant and speaker for Merz Pharmaceuticals, Allergan, and Ipsen. A. Bogucki was an investigator in the SIAXI study and served as a consultant for AbbVie, GE, UCB, and EVER. S. Ochudlo was an investigator in the SIAXI study and reports no other disclosures. M. Banach was an investigator in the SIAXI study and served as a consultant for Merz Pharmaceuticals. F. Pagan was an investigator in the SIAXI study. He has received research grants from US World Meds and Teva Neuroscience; educational grants from Medtronic; acted as a consultant for Acadia, Adamas, Merz Pharmaceuticals, and Teva Neuroscience; was a speaker for Acadia, Adamas, Teva, Merz Pharmaceuticals, and US World Meds. B. Flatau-Baqué is an employee of Merz Pharmaceuticals. J. Csikós is an employee of Merz Pharmaceuticals. C.J. Cairney is an employee of CMC CONNECT, a division of McCann Health Medical Communications Ltd. Glasgow, UK. Medical writing support was funded by Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH. A. Blitzer was an investigator in the SIAXI study. He received research funding from Allergan and Merz Pharmaceuticals; acted as a consultant for Merz Pharmaceuticals. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Parkes J, Hill N, Platt MJ, Donnelly C. Oromotor dysfunction and communication impairments in children with cerebral palsy: a register study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2010;52:1113–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalf JG, Smit AM, Bloem BR, Zwarts MJ, Munneke M. Impact of drooling in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol 2007;254:1227–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalf JG, de Swart BJ, Borm GF, Bloem BR, Munneke M. Prevalence and definition of drooling in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. J Neurol 2009;256:1391–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGeachan AJ, Hobson EV, Shaw PJ, McDermott CJ. Developing an outcome measure for excessive saliva management in MND and an evaluation of saliva burden in Sheffield. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2015;16:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko SH, Shin YB, Min JH, Shin JH, Shin YI, Ko HY. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of drooling in tetraplegic patients with brain injury. Ann Rehabil Med 2013;37:796–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hockstein NG, Samadi DS, Gendron K, Handler SD. Sialorrhea: a management challenge. Am Fam Physician 2004;69:2628–2634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozdilek B, Gunal DI. Motor and non-motor symptoms in Turkish patients with Parkinson's disease affecting family caregiver burden and quality of life. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012;24:478–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ou R, Guo X, Wei Q, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of drooling in Parkinson disease: a study on 518 Chinese patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2015;21:211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leibner J, Ramjit A, Sedig L, et al. The impact of and the factors associated with drooling in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2010;16:475–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banfi P, Ticozzi N, Lax A, Guidugli GA, Nicolini A, Silani V. A review of options for treating sialorrhea in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Respir Care 2015;60:446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatia KP, Münchau A, Brown P. Botulinum toxin is a useful treatment in excessive drooling in saliva. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;67:697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jost WH. Treatment of drooling in Parkinson's disease with botulinum toxin. Mov Disord 1999;14:1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Intiso D, Basciani M. Botulinum toxin use in neuro-rehabilitation to treat obstetrical plexus palsy and sialorrhea following neurological diseases: a review. Neurorehabilitation 2012;31:117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson CE, Gronseth G, Rosenfeld J, et al. Randomized double-blind study of botulinum toxin type B for sialorrhea in ALS patients. Muscle Nerve 2009;39:137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagalla G, Millevolte M, Capecci M, Provinciali L, Ceravolo MG. Botulinum toxin type A for drooling in Parkinson's disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord 2006;21:704–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lagalla G, Millevolte M, Capecci M, Provinciali L, Ceravolo MG. Long-lasting benefits of botulinum toxin type B in Parkinson's disease-related drooling. J Neurol 2009;256:563–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipp A, Trottenberg T, Schink T, Kupsch A, Arnold G. A randomized trial of botulinum toxin A for treatment of drooling. Neurology 2003;61:1279–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porta M, Gamba M, Bertacchi G, Vaj P. Treatment of sialorrhoea with ultrasound guided botulinum toxin type A injection in patients with neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;70:538–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa J, Rocha ML, Ferreira J, Evangelista T, Coelho M, de Carvalho M. Botulinum toxin type-B improves sialorrhea and quality of life in bulbar-onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol 2008;255:545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazlan M, Rajasegaran S, Engkasan JP, Nawawi O, Goh KJ, Freddy SJ. A double-blind randomized controlled trial investigating the most efficacious dose of botulinum toxin-A for sialorrhea treatment in Asian adults with neurological diseases. Toxins 2015;7:3758–3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinnapongse R, Gullo K, Nemeth P, Zhang Y, Griggs L. Safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin type B for treatment of sialorrhea in Parkinson's disease: a prospective double-blind trial. Mov Disord 2012;27:219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guidubaldi A, Fasano A, Ialongo T, et al. Botulinum toxin A versus B in sialorrhea: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, crossover pilot study in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2011;26:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jost WH. The option of sonographic guidance in botulinum toxin injection for drooling in Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm 2016;123:51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalf JG, Borm GF, de Swart BJ, Bloem BR, Zwarts MJ, Munneke M. Reproducibility and validity of patient-rated assessment of speech, swallowing, and saliva control in Parkinson's disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:1152–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas-Stonell N, Greenberg J. Three treatment approaches and clinical factors in the reduction of drooling. Dysphagia 1988;3:73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merz Pharmaceuticals LLC. Highlights of prescribing information—Xeomin®. 2018. Available at: accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/125360s073lbl.pdf. Accessed October 2, 2018.

- 27.McGeachan AJ, Mcdermott CJ. Management of oral secretions in neurological disease. Pract Neurol 2017;17:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srivanitchapoom P, Pandey S, Hallett M. Drooling in Parkinson's disease: a review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20:1109–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seppi K, Weintraub D, Coelho M, et al. The Movement Disorder Society evidence-based medicine review update: treatments for the non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2011;26(suppl 3):S42–S80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huss K, Berweck S, Schroder AS, Mall V, Borggräfe I, Heinen F. Interventional-neuropaediatric spectrum of treatments with botulinum toxin neurotoxin type A, free of complexing proteins: effective and safe application: three exemplary cases. Neuropediatrics 2008;39:P077. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kossmehl P, Freudenberg B, Wissel J. Experience with a new botulinum toxin type A formulation in the treatment of sialorrhoea. Abstract presented at the 4th Annual Congress of the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ISPRM); June 12–15, 2007; Seoul.

- 32.Castelnovo G, de Verdal M, Renard D, Boudousq V, Collombier L. Comparison of different sites of injections of incobotulinumtoxin (XEOMIN®) into the major salivary glands in drooling. Mov Disord 2013;28:S167. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez Abarca F, Ayala Valenzuela F. Experiencia con toxina botulinica tipo A para el tratamiento de la silorrea en edad pediatrica [in Spanish]. Rev Mex Neuroci 2012;13:111. [Google Scholar]

- 34.South A, Kumar H, Hall L, Jog M. Pilot study of new formulation of BoNT-A injection for sialorrhea in PD. Mov Disord 2011;26:S140. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Restivo DA, Panebianco M, Casabona A, et al. Botulinum toxin A for sialorrhoea associated with neurological disorders: evaluation of the relationship between effect of treatment and the number of glands treated. Toxins 2018;10:E55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narayanaswami P, Geisbush T, Tarulli A, Raynor S, Tarsy D, Gronseth G. Drooling in Parkinson's disease: a randomized controlled trial of incobotulinum toxin A and meta-analysis of Botulinum toxins. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;30:73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Isaacson S, Jackson C, Molho E, Trosch R, Ondo W, Clinch T. MYSTICOL: a multisite, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of rimabotulinumtoxinB for the treatment of sialorrhea in Parkinson's disease (PD) and other neurological conditions. Neurology 2017:P3.026. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bagheri H, Damase-Michel C, Lapeyre-Mestre M, et al. A study of salivary secretion in Parkinson's disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 1999;22:213–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clifford T, Finnerty J. The dental awareness and needs of a Parkinson's disease population. Gerodontology 1995;12:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erkkinen MG, Kim MO, Geschwind MD. Clinical neurology and epidemiology of the major neurodegenerative diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2018;10:a033118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No individual deidentified participant data are shared. Key elements of the study protocol, study design, and statistical analysis plan were deposited in the database of the US National Library of Medicine, record number NCT02091739, and the EU Clinical Trials Register, EudraCT record number 2012-005539-10. All relevant information is contained within this report and supplemental materials.