Abstract

Background

Diagnoses reflect clear cell morphologies when tumor cells have clear cytoplasm in many organs, and the nature of such clear cells is typically identified. Colorectal tubular adenoma or adenocarcinoma, conversely, rarely show clear cells, the reason for which remains uncertain. We report 2 colon tumors with clear cell components (Case 1: adenoma; Case 2: adenocarcinoma) and investigate the nature of the clear cells.

Case presentation

Case 1 was a 75-year-old man with a superficial elevated polyp detected in the rectum for whom endoscopic submucosal dissection was performed. Microscopically, 10% of the tumor showed dysplastic columnar epithelium with clear cytoplasm forming tubular structures accompanied by conventional tubular adenoma. Case 2 was a 58-year-old man with a pedunculated polyp found in his sigmoid colon for which polypectomy was performed. Microscopically, 90% of the tumor showed dysplastic columnar epithelium with clear cytoplasm forming fused glands or cribriform structures adjacent to the ordinal tubular adenocarcinoma. In both cases, clear and ordinary tumor cells were negative for CK7 and positive for CK20 and CDX2, consistent with findings of colorectal origin. Different results were found for CEA and CD10 staining. CEA was positive on the luminal side of the conventional area in contrast diffuse cytoplasmic staining of the clear cell area in both cases. CD10 was only positive for the clear cell component of case 2. The clear cell components were negative for Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), Alcian blue, and mucicarmine staining and AFP immunohistochemistry. An ultrastructural examination found multiple cytoplasmic lipid-like vacuoles in the clear cell component that were predominantly negative for adipophilin by immunoelectron microscopy.

Conclusions

We investigated tubular adenoma and tubular adenocarcinoma with clear cell components. The accompanying conventional tubular adenoma or adenocarcinoma cells helped us to evaluate the atypia of the clear cells. Diffuse cytoplasmic staining of CEA and CD10 suggested that the clear cell component might harbor malignant potential. We were unable to verify the well-known causes of clear cytoplasm, such as an accumulation of glycogen, lipid, or mucin and enteroblastic differentiation. The causes of clear cells in the colorectal region remain uncertain; however, possible explanations include autolysis and carbohydrate elution.

Keywords: Colon, Adenocarcinoma, Clear cell change, Electron microscopy

Background

In many organs, including the ovary, uterus, kidney, salivary gland, thyroid gland, skin, and breast, when tumor cells show clear cytoplasm, the diagnoses reflect the clear cell morphology, such as clear cell adenocarcinoma (CCA), clear cell carcinoma, glycogen-rich adenocarcinoma, lipid-rich adenocarcinoma, and other clear cell variants of each tumor [1]. These diagnoses tend to be used when the clear cell nature of the tumor is evident [1]. In colorectal tubular adenoma or adenocarcinoma, conversely, clear cells are rarely observed, the reason for which remains uncertain [2–26]. Herein, we report an additional case of tubular adenoma and of tubular adenocarcinoma, both of which have a clear cell component. We describe a thorough investigation of its clear cell etiology and review the literature.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 75 years old man with a past history of gastric cancer was introduced to Oita Prefectural Hospital for a routine colonoscopy examination. An 18 × 12 mm superficial elevated polyp was detected in the rectum and resected endoscopically.

Microscopically, 90% of the tumor cells showed dysplastic columnar epithelium with hyperchromatic short spindle nuclei regularly arranged in the basal portion and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 1a and b). We diagnosed it as conventional tubular adenoma with low grade dysplasia. Additionally, 10% of the tumor cells had dysplastic columnar epithelium with randomly arranged pyknotic polygonal nuclei and clear cytoplasm (Fig. 1a and b).

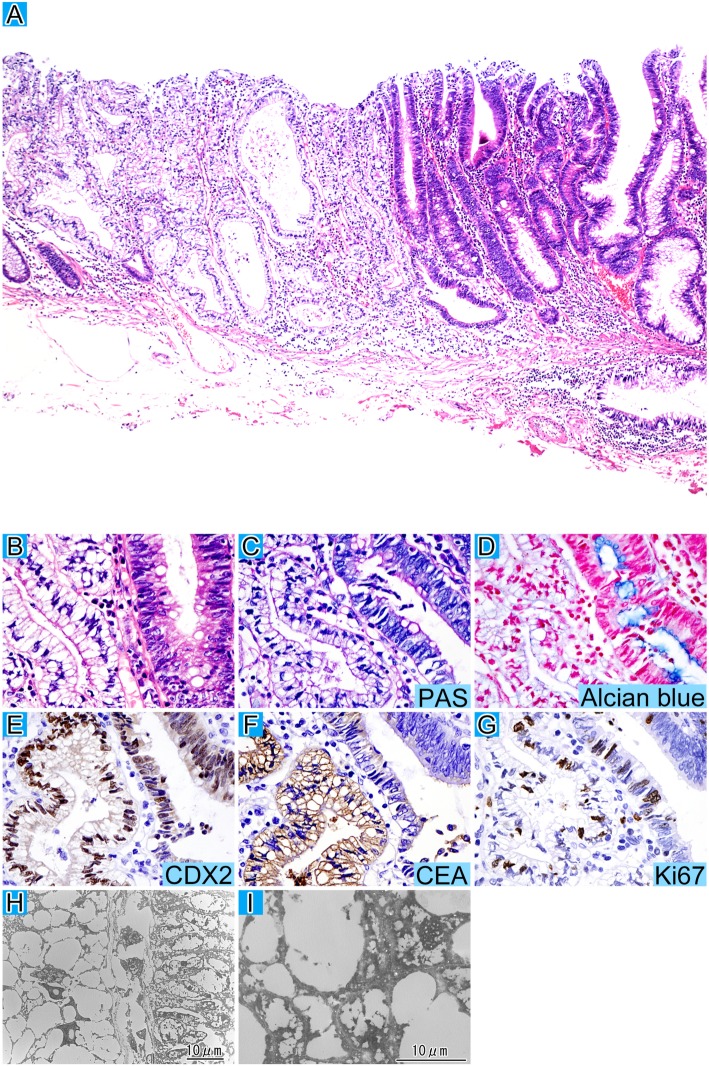

Fig. 1.

Tubular adenoma with clear cell change. The striking tubule structures of the clear cells are accompanied by conventional tubular adenoma cells at low magnification with HE staining (a). The boundary between the clear cell and conventional components at high magnification with HE staining (b). The clear cell component is negative for PAS (c) and alcian blue staining (d). Both components are positive for CDX2 staining (e). The localization of CEA (f) expression is diffusely cytoplasmic for the clear cell component, and luminal cell apical for the conventional one. Ki67 labeling (g) is slightly lower in the clear cell component. d-g represent immunohistochemistry. Ultrastructural examination (h) of the boundary between the clear cell area (left) and the conventional adenoma (right) at low magnification is shown and multiple cytoplasmic lipid-like vacuoles surround the nuclei in the clear cells (i)

Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), PAS diastase (PAS-D), Alcian blue, and mucicarmine staining were all negative for the clear cell component (Fig. 1c and d). The antibodies used in this study are listed in Table 1. Immunohistochemically, both tumor components were negative for CK7, focally positive for CK20, and positive for CDX2 (Fig. 1e). A difference in results was observed following staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (Fig. 1f). Positive CEA staining was found on the luminal side in the conventional area of the tumor; however, diffuse cytoplasmic staining was observed in the clear cell area. MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC6, CD10, AFP, AR, perilipin, and adipophilin were all negative for clear cell components. The Ki67 (Fig. 1g) labeling index (LI) was 83.7 and 73.8% for conventional and clear cell components, respectively. Electron microscopic examination found multiple lipid-like vacuoles in the clear cell component but not in the conventional component (Fig. 1h and i). He received regular follow-up and did not have a recurrence for 4 years.

Table 1.

Antibody information

| Antibody | Clone | Company | Dilution | Conditioning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK7 | OV-TL 12/30 | DAKO, Santa Clara, USA | 1:50 | Protease |

| CK20 | Ks 20.8 | DAKO, Santa Clara, USA | 1:50 | Protease |

| CDX2 | AMT28 | Novus Biologicals, Newcastle, UK | 1:50 | pH 9.0 |

| CEA | II-7 | DAKO, Santa Clara, USA | 1:40 | pH 6.0 |

| CD10 | 56C6 | Novocastra, Newcastle, UK | 1:50 | pH 6.0 overnight |

| MUC2 | Ccp58 | Novocastra, Newcastle, UK | 1:100 | pH 6.0 |

| MUC5AC | CLH2 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK | 1:1000 | |

| MUC6 | CLH5 | Novocastra, Newcastle, UK | 1:100 | pH 6.0 |

| AFP | N1501 | DAKO, Santa Clara, USA | diluted | |

| Glypican3 | 1G12 | Nichirei Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan | diluted | pH 9.0 |

| AR | AR441 | DAKO, Santa Clara, USA | 1:25 | pH 6.0 |

| Perilipin | GP29 | PROGEN, Heidelberg, Germany | 1:200 | pH 6.0 |

| Adipophilin | AP125 | Acris Antibodies, Herford, Germany | 1:10 | pH 6.0 |

| Ki67 | MIB-1 | DAKO, Santa Clara, USA | 1:50 | pH 6.0 |

| COX2 | CX-294 | DAKO, Santa Clara, USA | 1:100 | pH 9.0 |

| APC | CC-1 | Oncogene, California, USA | 1:20 | pH 6.0 |

CK Cytokeratin, CDX2 Caudal type homeobox 2, CEA Carcinoembryonic antigen, CD Cluster differentiation, MUC Mucin, AFP Alpha fetoprotein, AR Androgen receptor, COX2 Cyclooxygenase 2, APC Adenomatous polyposis coli

Case 2

A 58-year-old man was admitted to Oita University Hospital for the medical examination of an abnormality. The contrast CT examination showed a wall thickness of the sigmoid colon and a colonoscopy was performed. There were multiple polyps detected in the sigmoid colon and a 25 mm in size pedunculated polyp was endoscopically resected. Microscopically, 10% of the tumor cells were conventional tubular adenocarcinoma with hyperchromatic oval nuclei regularly arranged in the basal portion and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 2a, b, c, and d). The other tumor cells displayed dysplastic columnar epithelium with large epithelioid or polygonal nuclei randomly arranged and clear or vacuolated cytoplasm, showing cribriform or fused tubular structures and desmoplastic reaction was seen in the surrounding stroma (Fig. 2b). These findings were thought to be invasion. Tumor invaded into submucosa (pT1b).

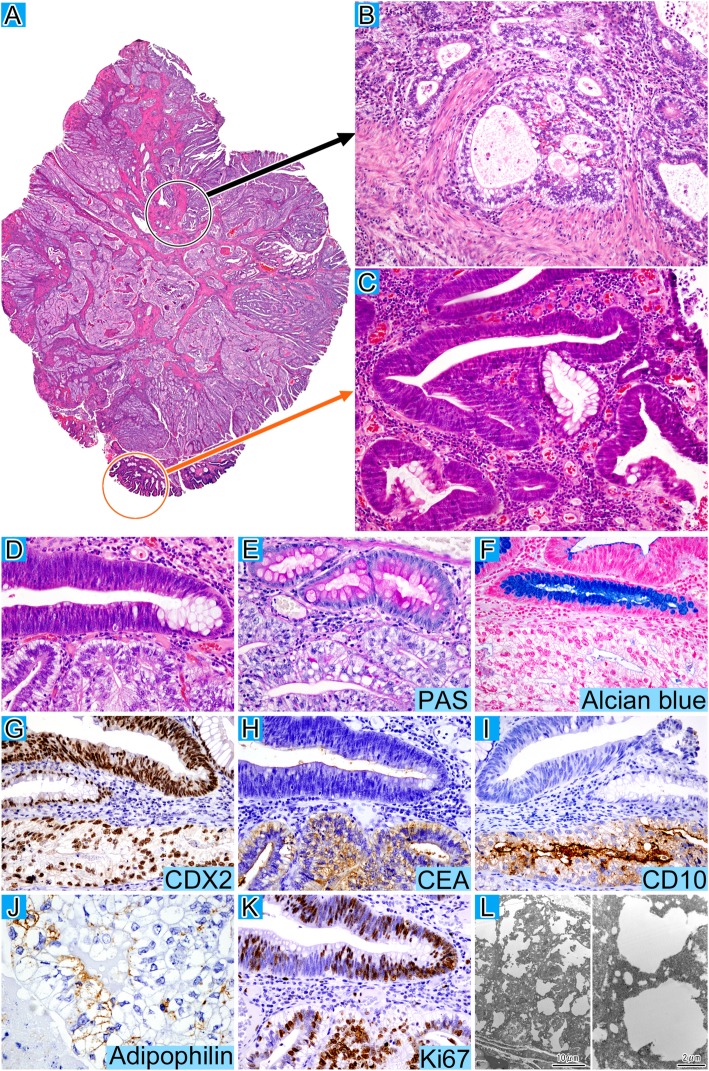

Fig. 2.

Clear cell adenocarcinoma. Low magnification (a) and high magnification of the clear cell (b) and conventional components (c) with HE staining. The boundary (d) between the clear cell and conventional components at high magnification with HE staining. The clear cells are negative for PAS (e) and alcian blue staining (f), whereas both components of the tumor are positive for CDX2 (g). The localization of CEA (h) expression is diffusely cytoplasmic for the clear cell component and luminal cell apical for the conventional component. CD10 (i) and adipophilin (j) expression is confined to the clear component and Ki67 labeling (k) is higher in the clear cell component. g-k represent immunohistochemistry. Immunoelectron microscopy analysis (l) at low (left) and high magnification (right) reveals multiple cytoplasmic lipid-like vacuoles in clear cells that are negative for adipophilin

PAS, PAS-D, Alcian blue, and mucicarmine staining were all negative for the clear cell component (Fig. 2e and f). Immunohistochemically, both tumor components were negative for CK7, focally positive for CK20, and positive for CDX2 (Fig. 2g) and MUC2. The differences in results between the two components were staining for CEA (Fig. 2h) and CD10 (Fig. 2i). Positive CEA staining was observed for the luminal aspect in the conventional component; however, there was diffuse cytoplasmic staining in the clear cell component. CD10 was only positive for the clear cell part and adipophilin (Fig. 2j) was only focally positive for clear cell component. MUC5AC, MUC6, AFP, glypican 3, perilipin, and AR were all negative. COX2 and APC were weakly diffuse cytoplasmic staining for both components, but the staining of APC seemed to attenuate or disappear in invasive areas. The Ki67 LI (Fig. 2k) was 80.0% and almost 100% for conventional and clear cell components, respectively. An immunoelectron microscopic examination was performed according to procedures described in a previous study [27] and showed that the nuclei were surrounded by multiple cytoplasmic lipid-like vacuoles similar to case 1 and they were mostly negative for adipophilin (Fig. 2l). Postoperative follow-up testing such as a laboratory examination, CT imaging, and endoscopic examination didn’t show any sign of recurrence and he was free from the disease for 1 year and a half.

Discussion and conclusions

A clear cell colorectal tumor was first described by Hellstrom’s report of a physaliferous variant of colon adenocarcinoma [10]. Clear cells were then detected in colorectal tubular adenoma, hyperplastic polyps, and tubular adenocarcinoma [2–9]. Domoto et al. [5] retrospectively analyzed the probability of clear cell tubular adenoma and its incidence was only 0.086%.

To date, there have been 44 cases of clear cell of colorectal epithelial tumors reported, composed of 20 adenomas (Table 2) and 24 adenocarcinomas (Table 3) [2–26]. The median age was 57.2 and 58.6 years for adenoma and adenocarcinoma, respectively. Both tumors showed a male predilection (adenoma: 11/17, adenocarcinoma: 18/23) and occurred mostly in the left-side colon (adenoma: 14/19, adenocarcinoma: 16/24). Some cases had multiple polyps at the same time [3, 7, 9, 11, 14, 16, 20] and two cases had multiple tubular adenomas with a clear cell component [7, 9]. Case 2 reported here had multiple polyps; however, no other polyps had clear cell components.

Table 2.

Clinicopathological information for 20 colorectal adenomas with clear cell components

| AuthorRef | Age | Sex | Location | Size (cm) | PAS | Alcian blue | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reed et al. [2] | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Jewell et al. [3] | 61 | F | R | 2 | – | – | Alive |

| Suzuki et al. [4] | 62 | M | D | 1.4 | – | – | Alive |

| Domoto et al. [5] | 54 | M | S | 6 | – | Scattered | |

| 45 | M | T | 6 | – | Scattered | ||

| 44 | M | S | 10 | – | Scattered | ||

| Eloy et al. [6] | 48 | F | T | 2.5 | ND | – | |

| 68 | F | S | 0.5 | ND | – | ||

| 84 | M | S | 1.8 | ND | – | ||

| Shi et al. [7] | ND | ND | ND | 0.8 | ND | ND | |

| 61 | M | S | 1.5 | ND | ND | ||

| ND | ND | ND | 1.8 | ND | ND | ||

| 63 | F | As | 0.5 | – | ND | ||

| 63 | M | R | 1.4 | – | ND | ||

| 68 | F | ND | 3.5 | – | ND | ||

| 30 | F | S | 1.4 | – | ND | ||

| 35 | M | S | 1.3 | ND | ND | ||

| Yao [8] | 48 | M | S | 0.8 | – | – | |

| Miyasaka et al. [9] | 63 | M | As, D, R | ND | – | – | |

| Present study | 75 | M | R | 1.8 | – | – | Alive |

M Male, F Female, As Ascending colon, T Transverse colon, D Descending colon, S Sigmoid colon, R Rectum, ND No data

Table 3.

Clinicopathological information for 24 colorectal adenocarcinomas with clear cell components

| AuthorRef | Age | Sex | Location | Size (cm) | PAS | Alcian blue | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hellstrom and Fisher [10] | 67 | M | R | 2 | −/+ | – | Alive |

| Reed et al. [2] | 71 | M | T | 7 | + | ND | |

| Jewell et al. [3] | 75 | M | S | 0.1 | – | – | Died |

| 56 | F | S | 6 | ND | – | ND | |

| Watson [11] | 58 | M | AC | 3.5 | + | – | Died |

| Rubio [12] | 68 | M | D | 6 | −/+ | – | Died |

| Furman and Lauwers [13] | ND | ND | R | ND | + | ND | ND |

| Braumann et al. [14] | 89 | M | T | 2.2 | – | – | Died |

| Mallik and Katchy [15] | 36 | F | R | 5 | + | + | ND |

| Ko et al. [16] | 62 | M | S | 1.5 | ND | ND | ND |

| Hao et al. [17] | 37 | M | D | 12 | + | – | Alive |

| Barisella et al. [18] | 54 | M | As | 0.9 | ND | ND | Alive |

| Soga et al. [19] | 71 | F | S | 0.8 | – | – | ND |

| Bressenot et al. [20] | 84 | F | D | 3.5 | – | – | Alive |

| Shi et al. [7] | 52 | M | R | 0.9 | – | ND | ND |

| 51 | M | S | 1.4 | – | ND | ND | |

| Furuya et al. [21] | 81 | M | As | 9.5 | + | ND | Died |

| Barrera-Maldonado et al. [22] | 41 | F | D | 3.4 | ND | ND | ND |

| Wang et al. [23] | 26 | M | T | 12 | ND | ND | Died |

| Thelin et al. [24] | 25 | M | As | 3 | ND | ND | Died |

| Remo et al. [25] | 58 | M | As | 7 | ND | ND | Died |

| 79 | M | As | 4.5 | ND | ND | Died | |

| Tochio et al. [26] | 48 | M | D | 0.7 | – | – | Alive |

| This study | 58 | M | S | 2.5 | – | – | Alive |

M Male, F Female, As Ascending colon, T Transverse colon, D Descending colon, S Sigmoid colon, R Rectum, AC Anal canal, ND No data

Histologically, the clear cells of colorectal tumors characteristically have pyknotic polygonal nuclei not confined to the basal portion but randomly arranged and clear or vacuolated cytoplasm [5]. In our cases, it was difficult to assess the nuclear atypia of clear cells, however, conventional tubular adenoma or adenocarcinoma cells accompanied them and there was a transition between both components. This helped us to recognize the clear cell components as the atypical equivalent to adenoma or adenocarcinoma. Moreover, it may be misleading to diagnose metastatic carcinoma if the clear cell component accounts for the vast majority of the tumor. Therefore, it is important to confirm a colorectal origin by immunohistochemical analysis of CK7, CK20, and CDX2 [7]. Our cases were CK7 negative, CK20 focally positive, and CDX2 diffusely positive, consistent with a colorectal origin.

Differences in staining results between the conventional and clear cell component were found for CEA and CD10. The localization of CEA is associated with tumor differentiation; thus, luminal cell apical expression of CEA is seen in well-differentiated tumors and, in contrast, cytoplasm expression is seen in poorly differentiated tumors [28]. The tumor cell phenotype correlates with tumor aggressiveness and biological behavior in several cancers. The expression of CD10 suggests colorectal adenocarcinoma with small intestinal differentiation, which is associated with higher venous invasion than large intestinal phenotype of colorectal adenocarcinoma [29]. The diffuse cytoplasmic expression of CEA and the confined expression of CD10 seen in clear cell areas may indicate that these clear cell components harbor greater malignant potential.

Generally, an accumulation of glycogen, mucin, and lipid, as well as enteroblastic differentiation, are well-known examples of the etiology or substances of clear cells in HE specimens. Colorectal tubular adenoma and adenocarcinoma with clear cell components were reported as tubular adenoma with clear cell change (TAC) and CCA, respectively [2–26]. In TAC, an accumulation of glycogen, mucin, and enteroblastic differentiation have never been verified by PAS, Alcian blue staining, or AFP immunostaining [2–9]. Case 1 is negative for those stains, in accord with previous TAC reports. In CCA, on the other hand, some cases are either positive for PAS [2, 11, 13, 15, 17, 21], Alcian blue staining [15], or AFP immunohistochemistry [21]; however, other cases are negative for these stains [3, 10, 12, 14, 19, 20, 26]. It seems that some heterogeneity exists among CCA cases [2, 3, 7, 10–26]. Case 2 is negative for PAS, Alcian blue staining, and AFP immunostaining and corresponds to previously reported negative-result cases. The pathogenesis of TAC and some CCA cases, including our cases, remains unclear. It may be more appropriate to diagnose Case 2 and those previously reported negative-result cases as tubular adenocarcinoma with clear cell change, corresponding with the malignant counter part of TAC, rather than CCA.

Electron microscopic examination revealed multiple cytoplasmic lipid-like vacuoles in the clear cells of both cases, and this finding corresponded to previous reports [3, 5, 10–12]. These vacuoles were described as autolysis or elution of glycogen granules during processing or fixation [5, 10], glycogen-like material with lipid to a lesser extent [11], and degeneration due to lipid accumulation [6, 9]. Miyasaka et al. [9] recently reported one case of TAC positive for adipophilin immunostaining and described that lipid accumulation might be responsible for its clear cell nature. In our report, Case 1 was negative for adipophilin but case 2 showed focal positive staining for it, which caused us to consider lipid accumulation; however, the immunoelectoron microscopy results were mostly negative for adipophilin. Bressenot et al. [20] reported a CCA and described that they could not detect glycogen in formalin sections but found it in frozen sections. In our study, we could not determine what caused the clear cells in the colorectal tumors; however, autolysis or carbohydrate elution remain possible explanations.

Conclusions

We report two colorectal tumors with a clear cell component. Accompanying components of conventional tubular adenoma or adenocarcinoma helped us to evaluate the atypia of the clear cells. Differences in staining results for CEA and CD10 were observed and the clear cell component might harbor malignant potential. We tested for the well-known causes of clear cells; however, none were detected. An electron microscopic examination found multiple cytoplasmic lipid-like vacuoles in the clear cell component; however, they were largely negative for adipophilin by immunoelectron microscopy. The causes of clear cells in the colorectal region remain uncertain.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Takashi Yao, professor of Juntendo University, for reviewing our case and giving us important diagnostic advice.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CCA

Clear cell adenocarcinoma

- CEA

carcinoembryonic antigen

- LI

Labeling index

- PAS

Periodic acid-Schiff

- PAS-D

PAS diastase

- TAC

Tubular adenoma with clear cell change

Authors’ contributions

YO made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and drafted the manuscript. TK, HK, MA, and KO assisted in the analysis and interpretation of the data. JW and SU made substantial contributions to the acquisition of data. HN and TD critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for this version to be published.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study was carried out according to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the institutional review board of Oita University Hospital, which determined that our retrospective study did not require additional informed consent. We removed any details that might disclose the identities of the subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuzo Oyama, Email: y-oyama@oita-u.ac.jp.

Haruto Nishida, Phone: +81-97-586-5683, Email: nharuto@oita-u.ac.jp.

Takahiro Kusaba, Email: t-kusaba@oita-u.ac.jp.

Hiroko Kadowaki, Email: hiro-kado@oita-u.ac.jp.

Motoki Arakane, Email: marakane@oita-u.ac.jp.

Kazuhisa Okamoto, Email: kokamoto@oita-u.ac.jp.

Junpei Wada, Email: wadajunpei@gmail.com.

Shogo Urabe, Email: s-urabe@oitapref-hosp.jp.

Tsutomu Daa, Email: daatom@oita-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Kwon TJ, Ro JY, Mackay B. Clear-cell carcinoma: an ultrastructural study of 57 tumors from various sites. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1996;20:519–527. doi: 10.3109/01913129609016356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reed R, Love G, Harkin J. Consultation case. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:597–601. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198309000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jewell LD, Barr JR, McCaughey WT, Nguyen GK, Owen DA. Clear-cell epithelial neoplasms of the large intestine. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1988;112:197–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki H, Ohta S, Tokuchi S, Moriya J, Fujioka Y, Nagashima K. Adenoma with clear cell change of the large intestine. J Surg Oncol. 1998;67:182–185. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199803)67:3<182::AID-JSO7>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domoto H, Terahata S, Senoh A, Sato K, Aida S, Tamai S. Clear cell change in colorectal adenomas: its incidence and histological characteristics. Histopathology. 1999;34:250–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eloy C, Lopes JM, Faria G, Moreira H, Brandao A, Silva T, et al. Clear cell change in colonic polyps. Int J Surg Pathol. 2009;17:438–443. doi: 10.1177/1066896908319211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi C, Scudiere JR, Cornish TC, Lam-Himlin D, Park JY, Fox MR, et al. Clear cell change in colonic tubular adenoma and corresponding colonic clear cell adenocarcinoma is associated with an altered mucin core protein profile. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1344–1350. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ec0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao T. Adenoma of clear cell change. Pathol Clin Med. 2016;34:1072–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyasaka C, Ishida M, Ohe C, Uemura Y, Ando Y, Fukui T, et al. Tubular adenomas with clear cell change in the colorectum: a case with four lesions and a review of the literature. Pathol Int. 2018;68:256–258. doi: 10.1111/pin.12628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellstrom HR, Fisher ER. Physaliferous variant of carcinoma of colon. Cancer. 1964;17:259–263. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196402)17:2<259::AID-CNCR2820170217>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson PH. Clear-cell carcinoma of the anal canal: a variant of anal transitional zone carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:350–352. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90237-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubio CA. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the colon. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:1142–1144. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.12.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furman J, Lauwers GY. Clear cell change in colonic adenocarcinoma: an equally unusual finding. Histopathology. 1999;35:476–477. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.035005476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braumann C, Schwabe M, Ordemann J, Jacobi CA. The clear cell adenocarcinoma of the colon: case report and review of the literature. Int J Color Dis. 2004;19:264–267. doi: 10.1007/s00384-003-0545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallik AA, Katchy KC. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the rectum. Med Princ Pract. 2005;14:58–60. doi: 10.1159/000081926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko YT, Baik SH, Kim SH, Min BS, Kim NK, Cho CH, et al. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon. Int J Color Dis. 2007;22:1543–1544. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0257-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hao LS, Zhu X, Zhao LH, Qian K, Zhou Y, Bu J, et al. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of colorectum: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2007;70:235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barisella M, Lampis A, Perrone F, Carbone A. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the colon is a unique morphological variant of intestinal carcinoma: case report with molecular analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6575–6577. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soga K, Konishi H, Tatsumi N, Konishi C, Nakano K, Wakabayashi N, et al. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the colon: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1137–1140. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bressenot A, Marcon N, Montagne K, Plenat F. Clear cell adenocarcinoma: a rare variant of primary colonic tumour. Int J Color Dis. 2008;23:137–138. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuya Y, Wakahara T, Akimoto H, Kishimoto T, Hiroshima K, Yanagie H, et al. Clear cell adenocarcinoma with enteroblastic differentiation of the ascending colon. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e647–e649. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.9670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrera-Maldonado CD, Wiener I, Sim S. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the colon: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2014;2014:905478. doi: 10.1155/2014/905478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang W, Li X, Qu G, Leng T, Geng J. Primary clear cell adenocarcinoma of the colon presenting as a huge extracolic mass: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:1873–1875. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thelin C, Alquist CR, Engel LS, Dewenter T. Primary clear cell adenocarcinoma of the colon: a case report and review. J La State Med Soc. 2014;166:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Remo A, Grillo F, Mastracci L, Fassan M, Sina S, Zanella C, et al. Clear cell colorectal carcinoma: time to clarify diagnosis. Pathol Res Pract. 2017;213:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tochio T, Mukai K, Baba Y, Asakawa H, Nose K, Tsuruga S, et al. Early stage clear cell adenocarcinoma of the colon examined in detail with image-enhanced endoscopy: a case report. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2018;11:465–469. doi: 10.1007/s12328-018-0889-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yano S, Kashima K, Daa T, Urabe S, Tsuji K, Nakayama I, et al. An antigen retrieval method using an alkaline solution allows immunoelectron microscopic identification of secretory granules in conventional epoxy-embedded tissue sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:199–204. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’brien M, Zamcheck N, Burke B, Kirkham S, Saravis C, Gottlieb L. Immunocytochemical localization of carcinoembryonic antigen in benign and malignant colorectal tissues: assessment of diagnostic value. Am J Clin Pathol. 1981;75:283–290. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/75.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao T, Tsutsumi S, Akaiwa Y, Takata M, Nishiyama K, Kabashima A, et al. Phenotypic expression of colorectal adenocarcinomas with reference to tumor development and biological behavior. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:755–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb01158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.