Abstract

The Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation-specific Comorbidity Index (HCT-CI) was developed and validated to weigh the burden of pretransplant comorbidities and estimate their impact on post-transplant risks of non-relapse mortality (NRM). Recently, the HCT-CI was augmented by the addition of both age and values of three markers namely, ferritin, albumin, and platelet count. The HCT-CI research so far has been almost exclusively limited to recipients of allogeneic HCT from human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-matched grafts. To this end, we sought to investigate the discriminative capacity of an augmented comorbidity/age index among 724 recipients of allogeneic HCT from HLA-mismatched (MM, n=345), haploidentical (n=117), and umbilical cord blood (UCB, n=262) grafts between 2000 and 2013. In the overall cohort, the augmented comorbidity/age index had a higher c-statistic estimate for prediction of NRM compared to the original HCT-CI (0.63 versus 0.59). Findings were similar for recipients of HLA-mismatched (0.62 versus 0.59), HLA-haploidentical (0.60 versus 0.54), or UCB grafts (0.65 versus 0.61). Patients with scores of <4 had higher survival rates compared to those with scores of ≥4 and received HLA-mismatched (55% versus 39%, p<0.0008), HLA-haploidentical (58% versus 38%, p=0.01), or UCB grafts (67% versus 48%, p=0.004), respectively. Our results demonstrate the utility of the augmented comorbidity/age index as a valid prognostic tool among recipients of allogeneic HCT from alternative graft sources.

Keywords: HCT-CI, augmented comorbidity/age index, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, comorbidities, HLA-mismatched, umbilical cord blood, haploidentical, age, validation

INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a curative therapeutic modality for most malignant and non-malignant hematological disorders. However, this treatment could be associated with a substantial risk of subsequent non-relapse mortality (NRM). Pre-transplant comorbidities, as evaluated by the hematopoietic cell transplantation-specific comorbidity index (HCT-CI), have been shown to provide accurate estimates about post allogeneic HCT NRM [1]. The prognostic value of the HCT-CI was further augmented by the addition of a score of 1 for ages ≥40 years [2] and scores for values of serum levels of ferritin, albumin, and platelet count [3] (this index herein designated “augmented comorbidity/age”). Nevertheless, the prognostic validity of the comorbidities have been almost exclusively studied among recipients of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched donor grafts, both in retrospective and prospective multi-center studies with consistent agreement on its validity among the majority of these studies [4–7].

In the U.S., more than 12,000 patients are diagnosed annually with a life-threatening hematological disorder that necessitates a curative allogeneic HCT. According to data from the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP), a suitable HLA-matched family member is potentially available for only approximately 30% of allogeneic HCT candidates. The remaining 70% of patients are otherwise offered allogeneic HCT utilizing alternative graft sources. For those patients, cures could still be achieved by offering HLA-mismatched, haploidentical grafts, or umbilical cord blood (UCB). However, allogeneic HCT using previous graft sources is potentially associated with higher risks of NRM compared to HLA-matched allogeneic HCT due to several reasons. For example, utilization of HLA-mismatched and haploidentical grafts has been shown to carry higher risks of graft rejection and severe graft versus host disease (GVHD) [8,9]. The use of a cyclophosphamide-dependent conditioning regimen in part addressed these problems but at the expense of a higher rate of relapse [10]. Likewise, UCB grafts have been associated with relatively higher risks of delayed engraftment and subsequent infections given the potentially insufficient cell dose [11]. Currently, there are no sufficient data to support the superior use of one graft source over the other.

According to data from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), recipients of unrelated grafts, including HLA-mismatched and UCB grafts, constitute the largest group of allogeneic HCT recipients in the US. The expansion in this group compared to recipients of related donor grafts was most noticeable after 2006, with the gap between these two groups widening steadily thereafter on an annual basis. By further analysis it is noted that transplants performed utilizing UCB grafts during the period of 2008 to 2012 has also expanded compared to previous periods, constituting 40% and 10% of all donor sources for pediatric and adult patients, respectively. Additionally, the percentage of haploidentical grafts recipients has been steadily increasing between 2011 and 2015 [12]. Whether comorbidities could convey a prognostic influence on outcome to counsel patients as to their most suitable graft source is yet to be investigated. A limited number of studies have looked at the prognostic value of comorbidities among alternative donor grafts recipients [13,14], but none have investigated the impact of the incorporation of both lab values and age to the HCT-CI into a single model.

In the current analysis, we explored whether 1) an augmented comorbidity/age index could stratify outcomes after allogeneic HCT from UCB, HLA-mismatched, or HLA haploidentical donors; and 2) if this index could guide appropriate graft source selection for patients with no suitable HLA-matched donors.

METHODS

Patients

Eligible patients were those who were recipients of an allogeneic HCT from an HLA-mismatched donor, a haploidentical donor, or from an UCB graft at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Fred Hutch) between 2000 and 2013. Patients with any hematological diagnoses, including non-malignant diseases, were included. Patients from all age groups were included. We retrospectively identified 724 patients as eligible candidates for the study divided as follows; HLA-mismatched graft recipients (n=345), haploidentical graft recipients (n=117), and UCB recipients (n=262).

The following data were obtained by extensive review of the patients’ medical records: demographic data: patients’ age and sex, donors’ age and sex; Karnofsky performance status (KPS); disease-related data: type, date of diagnosis, risk category, status at time of transplantation; transplantation-related data: stem cell source, conditioning regimen intensity, GVHD prophylaxis protocol, cytomegalovirus (CMV) serostatus, date, pretransplant serum albumin, ferritin, and platelet count; and cause of mortality. Augmented comorbidity/age scores for all patients were calculated by a single investigator as per recent guidelines [15].

Transplantation details

Conditioning regimens were categorized as high-dose, reduced-intensity, or nonmyeloablative based on their respective intensity. The choice of a specific regimen was determined according to the active research protocols at Fred Hutch at the time of transplantation.

For recipients of HLA-mismatched grafts, high-dose regimens consisted of busulfan 4/cyclophosphamide (BU/CY), CY/high-dose total body irradiation (TBI) (1200–1440 cGy depending to the protocol), or etoposide/high-dose TBI. Reduced-intensity and nonmyeloablative regimens consisted of CY/low-dose TBI (200–450 cGy depending on the protocol), or FLU/low-dose TBI, or BU (2 days)/FLU. In this group, HLA typing was determined at all loci by high-resolution techniques and all donors were HLA-mismatched at one or two loci (9/10 or 8/10) (A, B, C, DRB1, and DQB1). The majority of donors (87%) were unrelated.

For recipients of UCB grafts, high-dose regimens consisted of BU/CY with or without melphalan or CY/high-dose TBI with or without FLU. Reduced-intensity and nonmyeloablative regimens consisted of treosulfan/FLU/low-dose TBI or CY/FLU/low-dose TBI. More than half of patients (58%) received two units with a level of HLA matching of 6/6, 5/6, or 4/6 in one or both units.

For recipients of haploidentical grafts, high-dose regimens consisted of BU/CY, CY/high-dose TBI, or thiotepa/FLU/high-dose TBI. Reduced-intensity and nonmyeloablative regimens consisted of CY/low-dose TBI or CY/FLU/low-dose TBI, or thiotepa/FLU/TBI. Related donors with HLA mismatches at more than two loci were categorized as haploidentical donors.

The vast majority of GVHD prophylaxis regimens consisted of a combination of calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) and methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil with or without sirolimus. Among haploidentical grafts recipients, post-transplantation CY (PTCY) was administered for T-cell depletion in 96% (112) of patients, while the remaining 5 patients received non PTCY alternatives. Donors and recipients were categorized as being CMV positive or negative on the basis of results of CMV IgG serostatus being positive or negative, respectively.

Definitions

Incidence of 2-year NRM is defined as the percentage of patients dying from the date of allogeneic HCT (day 0) until the completion of two years from causes other than disease relapse. Low disease risk included acute leukemia in first complete remission (CR), chronic myeloid leukemia in first chronic phase, chronic lymphocytic leukemia in CR, myelodysplasia-refractory anemia or refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts, lymphoma in CR at the time of HCT, and non-malignant disorders. All remaining other diagnoses were considered high-risk. Comorbidities were collected as per previously published guidelines [15]. The augmented comorbidity/age index was defined as the sum of the original HCT-CI scores with the addition of scores for age ≥40 and for pretransplant biomarkers, serum ferritin, platelets count, and serum albumin, as previously described (Table 1) [3]. Conditioning regimens were classified into high-dose, reduced- intensity, or nonmyeloablative based on previously published criteria [16].

Table 1.

Definitions of comorbidities included in the augmented comorbidity/age index and their corresponding scores

| Comorbidity | Definition | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCT-CI | |||

| Arrhythmia | Any type of arrhythmia that has necessitated the delivery of a specific anti-arrhythmia treatment at any time point in the patient’s past medical history. | 1 | |

| Cardiac | Coronary artery disease,§ congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, or EF ≤50% | 1 | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis requiring treatment at any time point in patient’s past medical history. | 1 | |

| Diabetes | Requiring treatment with insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents continuously for 4 weeks before start of conditioning | 1 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | Transient ischemic attack or cerebrovascular accident | 1 | |

| Psychiatric disturbance | Any disorder requiring continuous treatments for 4 weeks before start of conditioning | 1 | |

| Hepatic, mild | Chronic hepatitis, bilirubin > ULN to 1.5 × ULN, or AST/ALT> ULN to 2.5 × ULN; at least two values of each within 2 or 4 weeks before start of conditioning. | 1 | |

| Obesity | Patients with a body mass index >35 kg/m2 for patients older than 18 years or a BMI-for-age of ≥ 95th percentile for patients of ≤ 18 years of age | 1 | |

| Infection | Requiring antimicrobial treatment starting from before conditioning and continued beyond day 0 | 1 | |

| Rheumatologic | Requiring specific treatment at any time point in the patient’s past medical history | 2 | |

| Peptic ulcer | Based on prior endoscopic or radiologic diagnosis | 2 | |

| Moderate/severe renal | Serum creatinine > 2 mg/dl (at least two values of each within 2 or 4 weeks before start of conditioning), on dialysis, or prior renal transplantation | 2 | |

| Moderate pulmonary | Corrected DLco (via Dinakara equation) and/or FEV1 of 66%–80% or dyspnea on slight activity | 2 | |

| Prior malignancy | Treated at any time point in the patient’s past history, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer | 3 | |

| Heart valve disease | Of at least moderate severity, prosthetic valve, or symptomatic mitral valve prolapse as detected by echocardiogram | 3 | |

| Severe pulmonary | Corrected DLco (via Dinakara equation) and/or FEV1 ≤ 65% or dyspnea at rest or requiring oxygen | 3 | |

| Moderate/severe hepatic | Liver cirrhosis, bilirubin > 1.5 × ULN, or AST/ALT > 2.5 × ULN; at least two values of each within 2 or 4 weeks before start of conditioning | 3 | |

| Augmented comorbidity/age index: all of the above plus | |||

| High ferritin | Values of ≥2500 as measured the closest prior to start of conditioning | 1 | |

| Mild hypoalbuminemia | Values of <3.5–3.0 as measured the closest prior to start of conditioning | 1 | |

| Moderate gypoalbuminemia | Values of < 3.0 as measured the closest prior to start of conditioning | 2 | |

| Thrombocytopenia | Values of <100,000 as measured the closest prior to start of conditioning | 1 | |

| Age | ≥40 years | 1 | |

Abbreviations: EF = ejection fraction; ULN= upper limit of normal; DLco= diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide: FEV1= forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

One or more vessel-coronary artery stenosis requiring medical treatment, stent, or bypass graft

Statistical methods

Cumulative incidence estimates were used to evaluate NRM, while Kaplan–Meier estimates were used to assess survival. Relapse or progression of the primary disease was treated as a competing risk for NRM. Events were analyzed over the entire follow up period. Within each donor graft source, adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) of the augmented comorbidity/age scores for 2-year NRM were derived from multivariate models adjusting for known confounders, namely age (as a continuous variable), conditioning intensity (high-dose versus reduced-intensity versus nonmyeloablative), CMV serostatus (positive versus negative), disease risk (high versus low), KPS (≤80% versus >80%), and year of transplant (2000 to 2004, 2005 to 2009, and 2010 to 3013). Multivariate P-values were based on adjustment for all other variables in the model. All P-values were derived from Wald statistics and were two-sided. C-statistics were computed for prediction of NRM and OS by the two indices as continuous predictors using previously published methods [17]. Standard errors for the c-statistics and p-values comparing c-statistics between indices were estimated from 50 bootstrap samples. All calculations and analyses were carried out in SAS (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Patients were divided into three cohorts according to the sources of their grafts. A total number of 724 patients were included in this analysis, 345 received HLA-mismatched grafts, 117 received haploidentical grafts, and 262 received UCB grafts. Table 2 summarizes characteristics of the three patient cohorts. Among recipients of allogeneic HCT utilizing HLA-mismatched grafts, 66% received high-dose conditioning regimens. The majority of these patients (61%) had high-risk diseases. Fifty-two percent (52%) had augmented comorbidity/age scores ≥4 at time of transplant. The majority of patients in this cohort (88%) had a KPS of ≥80%.

Table 2.

Patients characteristics according to their graft sources

| HLA-mismatched grafts recipients (n=345) | Umbilical cord blood grafts recipients (n=262) | Haploidentical grafts recipients (n=117) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conditioning (%) | |||

| High-dose | 66 | 55 | 3 |

| Nonmyeloablative/reduced-intensity conditioning | 35 | 45 | 97 |

| ATG use | 4 | 18 | 0 |

| Age, median (range) | 45 (0.6–76) | 37 (0.4–73) | 37 (0.5–74) |

| < 40 | 37 | 61 | 45 |

| ≥ 40 | 63 | 39 | 55 |

| Disease risk (%) | |||

| Low | 39 | 49 | 34 |

| High | 61 | 51 | 66 |

| Cytomegalovirus status | |||

| Negative | 43 | 40 | 32 |

| Positive | 57 | 60 | 68 |

| Donor type (%) | |||

| Related | 13 | 100 | |

| Unrelated | 87 | 100 | |

| Stem cells source (%) | |||

| Peripheral blood stem cells | 73 | 80 | |

| Bone marrow | 27 | 20 | |

| Umbilical cord blood | — | 100 | — |

| Single unit | — | 42 | — |

| Two units | — | 58 | — |

| Augmented comorbidity/age index (%) | |||

| <4 | 48 | 52 | 43 |

| ≥ 4 | 52 | 48 | 57 |

| Median (range) | 4 (0–14) | 3 (0–13) | 4 (0–14) |

| Karnofsky performance status score (%) | |||

| > 80 | 88 | 89 | 81 |

| ≤ 80 | 13 | 11 | 19 |

| Year of transplant (%) | |||

| 2000 to 2004 | 43 | 6 | 14 |

| 2005 to 2009 | 38 | 40 | 45 |

| 2010 to 2010 | 29 | 55 | 41 |

| Follow-up of surviving patients, years | |||

| Median (range) | 8.0 (1.2–16.1) | 4.1 (1.7–12.9) | 5.0 (0.2–11.4) |

missing for 1 HLA-mismatched recipient and 6 cord blood recipients

HCT-CI = Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation-specific Comorbidity Index.

Allogeneic HCT recipients utilizing UCB grafts were notably younger with 61% of patients being less than 40 years of age. Patients in this cohort had a similar distribution of low- and high-risk disease at 49% and 51%, respectively. Patients with augmented comorbidity/age scores ≥4 constituted 48% with the majority of patients (89%) having a KPS of ≥80%.

Haploidentical graft recipients received almost exclusively nonmyeloablative and RIC regimens (97%). This cohort had the highest percentage of patients with high-risk diseases at 66%. Fifty-seven percent (57%) of patients within this cohort had augmented comorbidity/age scores ≥4.

The most predominant comorbidities among the three groups were moderate pulmonary comorbidity and infections. The frequency of various components of the augmented comorbidity/age index across the three alternative donor groups are presented in Table 3.

Table 3:

Distribution of the different components of the augmented comorbidity/age index among the three donor groups.

| HLA-MM (n=345) | UCB (n=262) | Haplo (n=117) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Augmented comorbidity/age index components | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) |

| Arrhythmia | 6 (20) | 5(12) | 7(8) |

| Cardiac | 10(33) | 7(18) | 8(9) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 0.2(1) | 0.7(2) | 0.9(1) |

| Diabetes | 8(29) | 7(19) | 5(6) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4(14) | 4(10) | 3(3) |

| Psychiatric disturbance | 21(71) | 15(40) | 23(27) |

| Hepatic, mild | 12(40) | 18(49) | 14(16) |

| Obesity | 7(25) | 6(16) | 8(9) |

| Infection | 22(76) | 35(93) | 26(30) |

| Rheumatologic | 0.6(2) | 2(5) | 0 |

| Peptic ulcer | 2(8) | 2(4) | 3(3) |

| Moderate/severe renal | 0.9(3) | 0.8(2) | 3(3) |

| Moderate pulmonary | 35(122) | 33(86) | 37(44) |

| Prior malignancy | 10(36) | 9(24) | 9(10) |

| Heart valve disease | 1(4) | 2(6) | 2(2) |

| Severe pulmonary | 16(56) | 16(43) | 26(31) |

| Moderate/severe hepatic | 3(11) | 3(7) | 0.9(1) |

| High ferritin | 3 (11) | 3 (8) | 8 (9) |

| Mild Hypoalbuminemia | 14 (50) | 11 (29) | 25 (29) |

| Moderate hypoalbuminemia | 7 (23) | 4 (11) | 6 (7) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 44 (152) | 30 (79) | 49 (57) |

| Age ≥40 years | 62 (215) | 39 (101) | 55 (64) |

Prognostic value of the augmented comorbidity/age index among the whole cohort of patients and relative to the HCT-CI alone

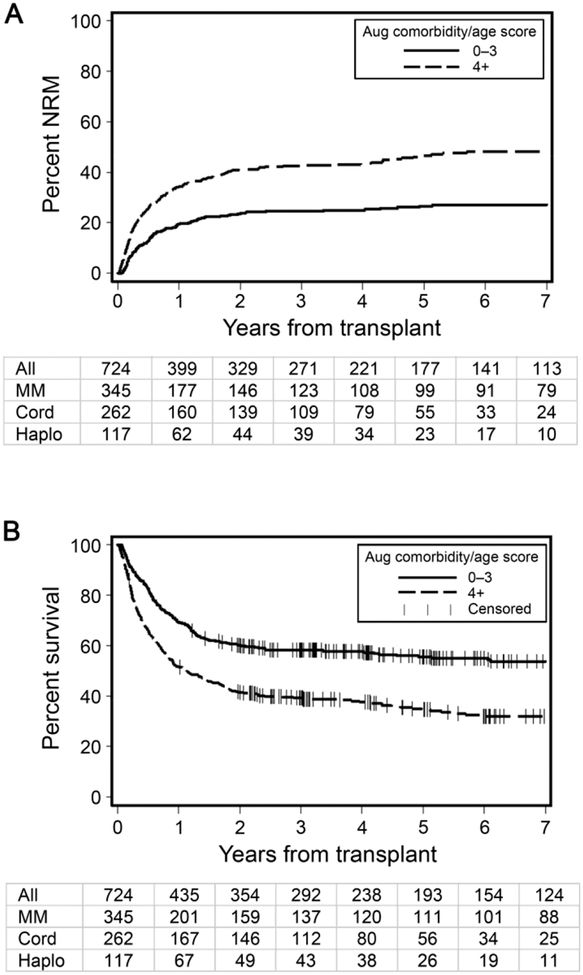

The prognostication of the augmented comorbidity/age index was compared to that of the original HCT-CI as determined by c-statistics estimates for different outcomes. Among the whole cohort, the augmented comorbidity/age index had higher c-statistics estimates for 2-year NRM compared to the original HCT-CI, 0.63 versus 0.59 (p = 0.0001), respectively. Similarly, the augmented comorbidity/age index provided better prognostication for 2-year OS compared to the original HCT-CI, c-statistic estimates of 0.60 versus 0.57 (p = 0.0001), respectively. C-statistic estimates were higher for the augmented comorbidity/age index as compared to original HCT-CI among individual donor groups as well (Table 4). Thus, we elected to utilize the augmented comorbidity/age index for the rest of the analysis. The scores of the augmented comorbidity/age index were collapsed into two binary risk groups with relatively equal patient sample distributions with scores <4 (48%) and ≥4 (52%) were considered low and high risk groups, respectively. Figures 1A and 1B illustrate the incidence of NRM and rate of OS and numbers of patients remaining at risk yearly following transplantation among the whole cohort of patients as stratified by the augmented comorbidity/age index.

Table 4.

c-statistic estimates (s.e.1) for the two risk indices among the whole cohort

| HCT-CI | Augmented comorbidity/age index | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-relapse mortality (266 events) | ||

| All donors (n=724) | 0.59 (0.02) | 0.63 (0.02) |

| Antigen mismatched (n=345) | 0.59 (0.02) | 0.62 (0.02) |

| Cord blood (n=262) | 0.61 (0.03) | 0.65 (0.03) |

| Haploidentical (n=117) | 0.54 (0.05) | 0.60 (0.04) |

| Overall survival (406 events) | ||

| All donors (n=724) | 0.57 (0.02) | 0.60 (0.02) |

| Antigen mismatched (n=345) | 0.58 (0.02) | 0.60 (0.02) |

| Cord blood (n=262) | 0.59 (0.03) | 0.61 (0.03) |

| Haploidentical (n=117) | 0.54 (0.03) | 0.59 (0.03) |

s.e. and p-value estimated from 50 bootstrap samples

Figure 1. Outcomes of the entire patient cohort as stratified by the augmented comorbidity/age index.

A) Cumulative incidences of non-relapse mortality (NRM) among the whole cohort of patients as stratified by the augmented comorbidity/age index. B) Rates of overall survival among the whole cohort of patients as stratified by the augmented comorbidity/age index. Table below each graph depicts the number of patients remaining at risk by year from HCT

Performance of the augmented comorbidity/age index among recipients of HLA-mismatched grafts

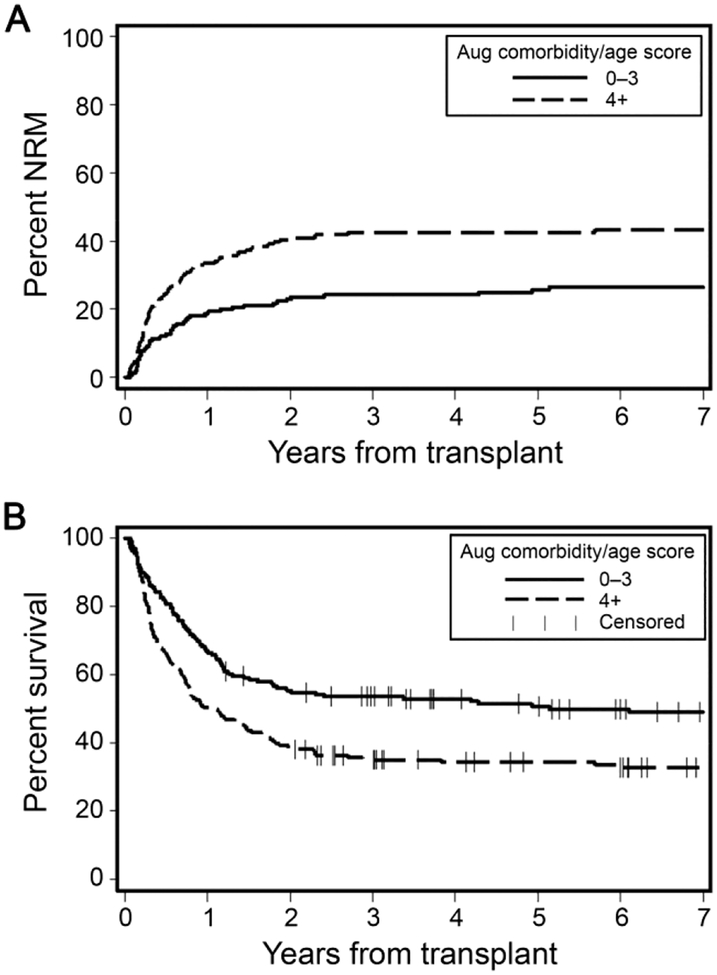

Higher augmented comorbidity/age index scores were statistically significantly associated with lower OS and higher NRM. Patients with scores ≥4 had almost double the risk of 2-year NRM compared to those with scores <4, 41% versus 23%, respectively (p<0.0001) (Figure 2A). Two-year OS rates were higher among patients with low-risk versus high-risk scores, 55% versus 39%, respectively, (p<0.0008) (Figure 2B). In regression models adjusted for conditioning intensity, age, CMV serostatus, disease risk, and KPS, and year of transplantation, hazards of 2-year NRM were significantly higher with increasing augmented comorbidity/age index scores, with a hazard ratio (HR)=1.52 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00–2.30, p=0.05]. Two-year OS had a HR=1.29 [95% CI 0.94–1.75, p=0.11] (Table 5). C-statistic estimates were 0.62 and 0.60 for 2-year NRM and 2-year OS, respectively, when the augmented comorbidity/age scores were treated as a continuous variable.

Figure 2. Outcomes of recipients of HLA-mismatched grafts as stratified by the augmented comorbidity/age index.

A) Cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality (NRM) among HLA-mismatched grafts recipients as stratified by augmented comorbidity/age index scores <4 versus ≥4. B) Rates of overall survival among HLA-mismatched grafts recipients as stratified by augmented comorbidity/age scores <4 versus ≥4.

Table 5.

*Multivariate regression model of the augmented comorbidity/age index among three sources of donor grafts

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-relapse mortality | ||

| HLA-mismatched | 1.52 (1.00–230) | 0.05 |

| Umbilical cord blood | 2.04 (1.20–3.47) | 0.008 |

| Haploidentical | 1.19 (0.62–2.29) | 0.60 |

| Overall survival | ||

| HLA-mismatched | 1.29 (0.94–1.75) | 0.11 |

| Umbilical cord blood | 1.49 (0.96–231) | 0.08 |

| Haploidentical | 1.66 (0.95–2.92) | 0.08 |

Augmented comorbidity/age index scores ≥4 compared to augmented comorbidity/age scores <4. Adjusted for conditioning (high-dose, reduced-intensity, or nonmyeloablative), age (<50, ≥50), cytomegalovirus serostatus (+, −), disease risk (low, high), and Karnofsky Performance Status score (≤80, >80), and year of transplant (2000 to 2004, 2005 to 2009, 2010to 2013).

Performance of the augmented comorbidity/age index among recipients of haploidentical grafts

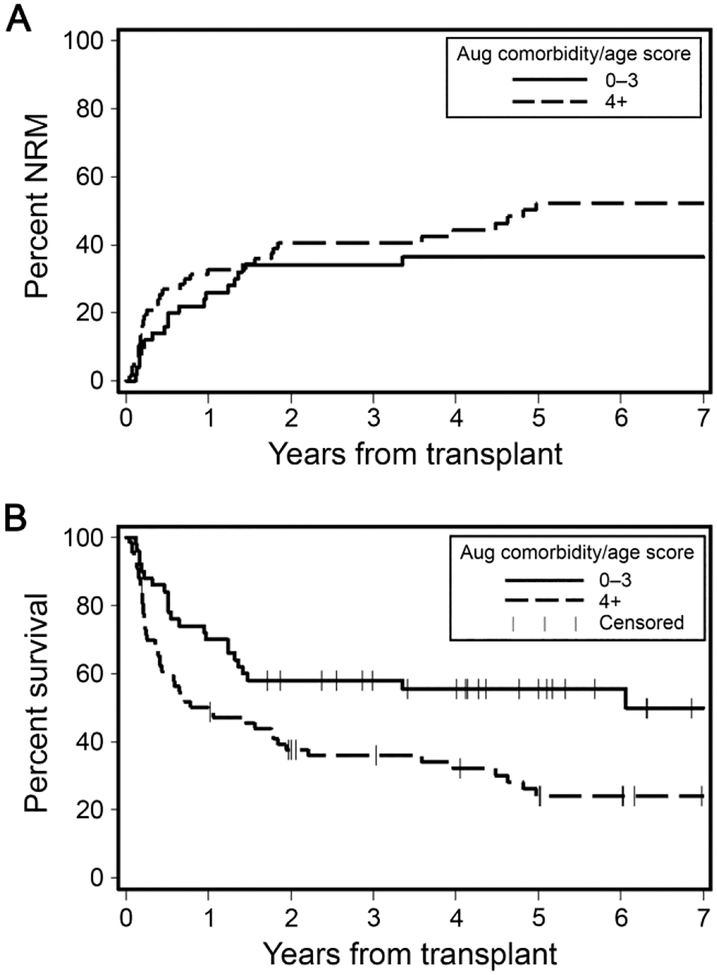

Cumulative incidences of 2-year NRM were not statistically significantly different among patients with lower (<4) versus those with higher (≥4) augmented comorbidity/age scores, 34% versus 41%, respectively (p=0.07) (Figure 3A). However, lower comorbidity burden was associated with significantly better rates of 2-year OS, 58% versus 38% for patients with augmented comorbidity/age scores <4 versus ≥4, respectively (p=0.01) (Figure 3B). In models adjusted for previous risk factors, higher augmented comorbidity/age scores were not associated with OS, HR=1.66 [95% CI 0.95–2.29, p0.08], or with NRM, HR=1.19 [95% CI 0.62–2.29, p0.60], for patients with scores ≥4 (Table 5). Continuous c-statistic estimates were the lowest among all three cohorts, 0.60 and 0.59, for NRM and OS, respectively.

Figure 3. Outcomes of recipients of haploidentical grafts as stratified by the augmented comorbidity/age index.

A) Cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality (NRM) among haploidentical grafts recipients as stratified by augmented comorbidity/age scores <4 versus ≥4. B) Rates of overall survival among haploidentical grafts recipients as stratified by augmented comorbidity/age scores <4 versus ≥4.

Performance of the augmented comorbidity/age index among recipients of UCB grafts

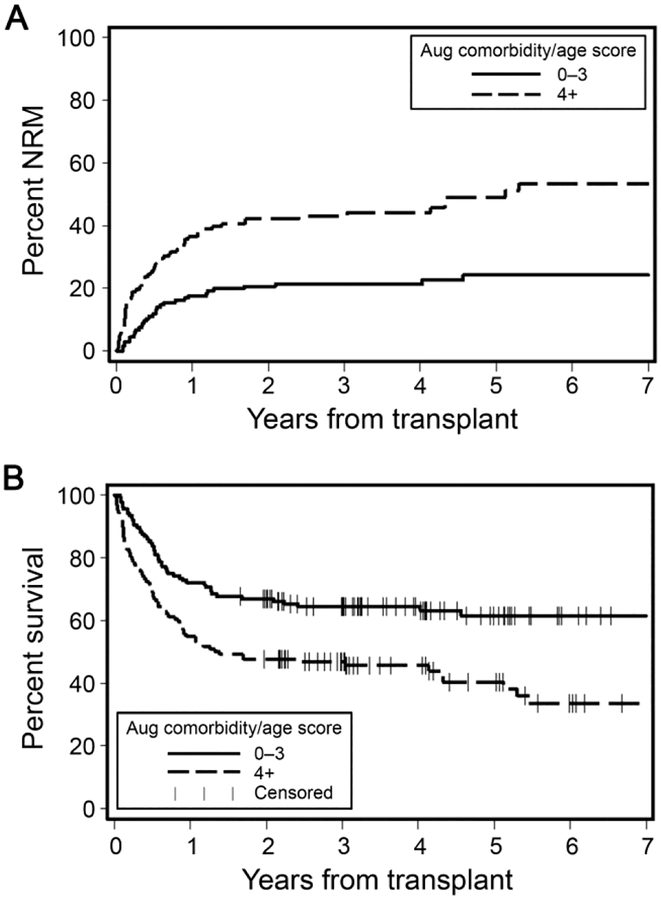

Cumulative incidences of 2-year NRM were 21% versus 42% for patients with augmented comorbidity/age scores <4 versus ≥4, respectively (p<0.0001) (Figure 4A). Lower augmented comorbidity/age scores <4 were associated with better 2-year OS compared to scores ≥4, 67% versus 48%, respectively (p=0.004) (Figure 4B). In multivariate regression models adjusted for previously mentioned factors, higher augmented comorbidity/age scores were associated with significantly higher hazards of 2-year NRM, HR= 2.04 [95% CI 1.20–3.47, p=0.008]. Two-year OS had an HR=1.49 [95% CI 0.96–2.31, p0.08] (Table 5). Continuous c-statistic estimates for the predictive power of the model for NRM and OS were 0.65 and 0.61, respectively.

Figure 4. Outcomes of recipients of umbilical cord blood grafts (UCB) as stratified by the augmented comorbidity/age index.

A) Cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality (NRM) UCB graft recipients as stratified by augmented comorbidity/age scores <4 versus ≥4. B) Rates of overall survival among UCB graft recipients as stratified by augmented comorbidity/age scores <4 versus ≥4.

Can the augmented comorbidity/age index be used to choose between graft sources?

In a separate multi-variate analysis, we compared the three graft sources in regards to NRM and survival within each of the low (<4) and high-risk groups (≥4) per the augmented comorbidity/age scores. There were no significant differences in outcomes among the three graft sources whether within the low- or high-risk groups (Table 6).

Table 6.

Adjusted hazard ratios for nonrelapse mortality and overall survival as stratified by augmented comorbidity/age index comparing alternative graft sources

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted* HR (95% CI) | Adjusted* p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonrelapse mortality with augmented comorbidity/age score <4 | ||||

| Antigen mismatched | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Cord blood | 0.87 (0.55–1.38) | 0.56 | 0.98 (0.59–1.62) | 0.94 |

| Haploidentical | 1.42 (0.82–2.47) | 0.21 | 1.24 (0.58–2.63) | 0.58 |

| Nonrelapse mortality with augmented comorbidity/age score ≥4 | ||||

| Antigen mismatched | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Cord blood | 1.06 (0.75–1.48) | 0.75 | 1.40 (0.88–2.24) | 0.16 |

| Haploidentical | 1.18 (0.78–1.77) | 0.43 | 1.48 (0.82–2.66) | 0.19 |

| Overall Survival with augmented comorbidity/age score <4 | ||||

| Antigen mismatched | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Cord blood | 0.73 (0.52–1.04) | 0.08 | 0.84 (0.58–1.23) | 0.37 |

| Haploidentical | 0.96 (0.61–1.51) | 0.86 | 0.99 (0.53–1.86) | 0.99 |

| Overall survival with augmented comorbidity/age score ≥4 | ||||

| Antigen mismatched | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Cord blood | 0.87 (0.65–1.17) | 0.36 | 0.94 (0.64–1.36) | 0.73 |

| Haploidentical | 1.16 (0.83–1.63) | 0.38 | 1.20 (0.76–1.91) | 0.43 |

Adjusted for conditioning (myeloablative, reduced-intensity, or nonmyeloablative), age (<50, ≥50), cytomegalovirus serostatus (+, −), disease risk (low, high), and Karnofsky Performance Status score (≤80, >80)

DISCUSSION

Outcome research studies focusing on recipients of allogeneic HCT from alternative graft sources are limited. Here, we were able to validate the discriminative capacity of a composite model combining an augmented HCT-CI and age among a group of patients receiving either HLA-mismatched, HLA-haploidentical, or UCB grafts. Patients with scores of ≥4 consistently had worse survival compared to patients with lower scores regardless of graft source. Findings are important in counseling patients in the clinic about risks of HCT. Further, within the limitation of a retrospective study, we could not find an advantage of one graft source versus the other within groups of patients with either low or high risk per comorbidity/age burden. Pending prospective randomized studies, results indicate that either graft source could be used for patients who have multiple comorbidities or older age.

In the present analysis, the prognostic validity of the augmented comorbidity/age index among recipients of alternative graft sources was evaluated. We added another layer of data to augment the prognostication provided by the HCT-CI through the inclusion of both serum lab values of ferritin, albumin, and platelets, and age as previously described [2,3]. The augmented comorbidity/age index consistently stratified outcomes across the three groups of alternative graft sources. The augmented comorbidity/age index scores were collapsed into low- and high-risk groups with significant differences in outcomes, with the exception of recipients of haploidentical grafts where the difference did not reach statistical significance for NRM. Additionally, we confirm an observation that was previously reported by our group and by others regarding the interpretation of prognostic data provided by the HCT-CI scores when utilized as two binary risk groups: the HCT-CI scores were meant to capture an association between worse overall survival and increased NRM with increasing scores; however, these associations are relative and not absolute [13,18,19].

The incidences of NRM and rates of OS and their respective hazard ratios at 2 years were comparable across recipients of HLA-mismatched, UCB, and haploidentical grafts recipients in each augmented comorbidity/age index risk group; however, it should be noted that this is a retrospective non-randomized analysis. Other variables, for example, minimal residual disease, could be utilized to compare outcomes across alternative graft sources [20]. Such a finding emphasizes the need for prospective randomized trials comparing outcomes between recipients of allogeneic HCT from alternative graft sources to provide data to counsel patients on their most suitable graft source. The augmented comorbidity/age index could be used here to adjust comparisons in outcomes among different graft sources in these trials. Currently there is an ongoing multi-center randomized clinical trial addressing the later question comparing double cord versus haploidentical grafts as sources for allogeneic HCT (BMTCTN1101) (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01597778). Evaluating outcomes per comorbidity risk groups could be important for individualized application of study results per comorbidity burden.

In the current study, the augmented comorbidity/age scores for all patients were assigned by a single investigator (M.E.) with significant inter-rater agreement with the principal investigator (M.L.S.) as measured by weighted kappa estimate of 0.95 (SE 0.03), indicating excellent agreement on comorbidity coding. This highlights the relevance of adapting consistent guidelines for comorbidity coding when validating the model as was previously described [15]. Additionally, the augmented comorbidity/age index risk groups had comparable numbers of patients among different patients’ cohorts, thus providing reliable results.

Nevertheless, our analysis has some limitations. First is the retrospective nature of our study. Second, the association between augmented comorbidity/age scores and NRM among the haploidentical grafts recipients was weak. This is probably attributed to the lower number of patients included in the analysis (n=117), since we have previously shown that the lowest number of patients required to validate the model is at least 200 patients [4]. Despite this limitation, our cohort is considered among the largest single center series of haploidentical grafts recipients. Future application on a large cohort of patients with HLA-haploidentical grafts is warranted.

Our results highlight the importance of incorporating comorbidity index into the design and interpretation of trial results. Future research should focus on testing the role of comorbidities in decision making about graft source selection in a large multi-center study.

HIGHLIGHTS.

An augmented comorbidity/age index comprising the HCT-CI, age, serum values of albumin, ferritin, and platelets has a higher predictive power for HCT outcomes among recipients of alternative donor grafts compared to the HCT-CI alone.

There were no significant differences in outcomes among the three graft sources whether within the low- or high-risk groups per the augmented comorbidity/age index suggesting suitability of the current practice of using any available alternative donor graft.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the many physicians, nurses, research nurses, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, data coordinators, and support staff who cared for our patients, and to the patients who allowed us to care for them and who participated in our ongoing clinical research. We also thank Helen Crawford for her help with manuscript preparation.

Financial disclosure. Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers P01 CA078902 (National Cancer Institute) and P01 HL122173 (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, which had no involvement in the in study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication. MLS was supported by funding from Pathway to Independence Grant HL088021 from the National Institutes of Health. AH was supported by funding from joint supervision grant from the Egyptian Ministry of Higher Education.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors have no conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106:2912–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorror ML, Storb RF, Sandmaier BM, et al. Comorbidity-age index: a clinical measure of biologic age before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3249–3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaughn JE, Storer BE, Armand P, et al. Design and validation of an augmented hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index comprising pretransplant ferritin, albumin, and platelet count for prediction of outcomes after allogeneic transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:1418–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ElSawy M, Storer BE, Pulsipher MA, et al. Multi-centre validation of the prognostic value of the haematopoietic cell transplantation-specific comorbidity index among recipients of allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2015;170:574–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorror ML, Logan BR, Zhu X, et al. Prospective validation of the predictive power of the hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index: a Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:1479–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raimondi R, Tosetto A, Oneto R, et al. Validation of the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation-Specific Comorbidity Index: a prospective, multicenter GITMO study. Blood. 2012;120:1327–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elsawy M, Sorror ML. Up-to-date tools for risk assessment before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:1283–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gyurkocza B, Rezvani A, Storb R. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: the state of the art. Expert Review of Hematology. 2010;3:285–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh LP, Chao N. Haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation (Review). Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2008;42 Suppl 1:S60–S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luznik L, O’Donnell PV, Fuchs EJ. Post-transplantation cyclophosphamide for tolerance induction in HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation. Seminars in Oncology. 2012;39:683–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker JN. Umbilical Cord Blood (UCB) transplantation: an alternative to the use of unrelated volunteer donors? (Review). Hematology. 2007;2007:55–61; 10.1182/asheducation-2007.1181.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Souza A, Zhu X. Current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT): CIBMTR Summary Slides, 2016. 2016:Available at: http://www.cibmtr.org.

- 13.Salit RB, Oliver DC, Delaney C, Sorror ML, Milano F. Prognostic value of the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Comorbidity Index for patients undergoing reduced-intensity conditioning cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23:654–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mo XD, Xu LP, Liu DH, et al. The hematopoietic cell transplantation-specific comorbidity index (HCT-CI) is an outcome predictor for partially matched related donor transplantation. American Journal of Hematology. 2013;88:497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorror M How I assess comorbidities prior to hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2013;121:2854–2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gyurkocza B, Sandmaier BM. Conditioning regimens for hematopoietic cell transplantation: one size does not fit all. Blood. 2014;124:344–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrell FE Jr., Califf RM, Pryor DB, Lee KL, Rosati RA. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. Jama. 1982;247:2543–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barba P, Piñana JL, Martino R, et al. Comparison of two pretransplant predictive models and a flexible HCT-CI using different cut points to determine low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups: the flexible HCT-CI is the best predictor of NRM and OS in a population of patients undergoing allo-RIC. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16:413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorror ML, Storer B, Storb R. Assignment of scores for the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation-Comorbidity Index: integer vs exact weights (Letter to the Editor). Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2011;46:464–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milano F, Gooley T, Wood B, et al. Cord blood transplant in patients with minimal residual disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375:944–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]