Abstract

Amylin is an important gut-brain axis hormone. Since amylin and amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) share similar β sheet secondary structure despite not having the same primary sequences, we hypothesized that the accumulation of Aβ in the brains of subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) might compete with amylin for binding to the amylin receptor (AmR). If true, adding exogenous amylin type peptides would compete with Aβ and reduce the AD pathological cascade, improving cognition. Here we report that a 10-week course of peripheral treatment with human amylin significantly reduced multiple different markers associated with AD pathology, including reducing levels of phospho-tau, insoluble tau, two inflammatory markers (Iba1 and CD68), as well as cerebral Aβ. Amylin treatment also led to improvements in learning and memory in two AD mouse models. Mechanistic studies showed that an amylin receptor antagonist successfully antagonized some protective effects of amylin in vivo, suggesting that the protective effects of amylin require interaction with its cognate receptor. Comparison of signaling cascades emanating from AmR suggest that amylin electively suppresses activation of the CDK5 pathway by Aβ. Treatment with amylin significantly reduced CDK5 signaling in a receptor dependent manner, dramatically decreasing the levels of p25, the active form of CDK5 with a corresponding reduction in tau phosphorylation. This is the first report documenting the ability of amylin treatment to reduce tauopathy and inflammation in animal models of AD. The data suggest that the clinical analog of amylin, pramlintide, might exhibit utility as a therapeutic agent for AD and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Amylin, Amylin receptor, Alzheimer’s disease, Aβ, p-Tau, Neuroinflammation, Learning and memory, Therapeutic

1. Introduction

Amylin (also known as islet amyloid polypeptide or IAPP) is a highly conserved 37–amino acid peptide that functions as a gut-brain axis hormone (Lutz, 2013; Mietlicki-Baase, 2016; Nishi et al., 1989). Amylin is produced and secreted by the b-cells in pancreas and easily crosses the blood brain barrier (BBB) to bind to its receptor and function in the brain (Banks and Kastin, 1998; Banks et al., 1995; Olsson et al., 2007). The amylin receptor (AmR) is a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) (Hay et al., 2015) that mediates several important functions, including regulating glucose metabolism, modulating inflammatory reactions and probably enhancing neurogenesis (Edvinsson et al., 2001; Roth et al., 2013; Trevaskis et al., 2010; Westfall and Curfman-Falvey, 1995).

While an amylin gene polymorphism is associated with cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Roostaei et al., 2016), increased plasma amylin levels are associated with better cognition in humans (Qiu et al., 2014). Recent studies from two independent laboratories, including our own, find that peripheral treatment with human amylin or its clinically approved analog, pramlintide (Roth et al., 2012), reduced amyloid burden and improved cognitive impairment in multiple mouse models of AD (Adler et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2015). These positive results raise the possibility that the AmR could be effective targets for therapy of AD.

The mechanism for the beneficial effect of amylin in the AD brain is unclear. Amylin and amyloid-β peptide (Aβ), a major component of AD pathology (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002), share several features, including similar β-sheet secondary structures (Lim et al., 2008), binding to the same AmR (Fu et al., 2012) and being degraded by (Bennett et al., 2003; Qiu et al., 1998; Shen et al., 2006) or bound to insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) (de Tullio et al., 2013). We hypothesized that the elevated levels of Aβ that accumulate in AD could block the AmR, while administering exogenous amylin could provide neuroprotection by competing with Aβ at the AmR (Qiu and Zhu, 2014).

The pathological cascade in AD is thought to proceed from the accumulation of senile amyloid plaques to formation of neurofibrillary tangles with concurrent neuroinflammation, synaptic loss, neuronal death and clinical dementia. If amylin is an effective treatment for AD, the direct effects of amylin should interfere with the AD pathological cascade, inhibiting tauopathy and preventing cognitive decline in humans (Lee et al., 2011). To test whether AmR agonists could delay disease progression, we administered amylin without and with co-injection of its antagonist, AC253 (Coppock et al., 1999), to two different animal models of AD, 5XFAD, which develops only Aβ pathology, and the 3xTgAD model, which develops both Aβ and tau pathology. We chose to use human amylin for the treatments to allow better translation of our study to the pathological process in humans. Here we report that amylin delays disease progression in these models, decreasing phosphorylated tau protein (pTau), as well as reducing the accumulation of Aβ and neuroinflammation to arrest cognitive decline. Our study demonstrates that amylin-type peptides have the potential to be an effective therapeutic for AD and identifies the AmR as a novel drug target for the disease.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice and experimental treatments

Two AD mouse models, 1) 5XFAD mice, which are amyloid precursor protein (APP)/presenilin 1 (PS1) double transgenic mice with five familial AD mutations (Oakley et al., 2006) and 2) 3xTgAD mice, which are APP Swe/Tau P301L/PS1 triple transgenic mice (Oddo et al., 2003), and wild-type (WT) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All mice were maintained in a microisolator of the animal facility at Boston University School of Medicine, MA, USA. Human amylin was purchased from AnaSpec (Fremont, CA, USA), and AC-253 and AC187 were purchased from US Biologicals (Cary, NC, USA). Female 5XFAD mice aged 3.5 months and female 3xTgAD mice aged 9 months were used for the experiments. The mice were treated with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of amylin (200 μg/kg) vs. amylin (200 μg/kg) plus AC253 (200 μg/kg) vs. phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) once daily for 10 weeks. Experimental groups (n = 10 per cohort) were matched for age and weight. Blood draws were conducted to collect serum after the treatments were completed. To collect cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), the cisterna magna was exposed under anesthesia and then a pulled glass micro-pipette was used for lumbar puncture to obtain CSF in these mice. Generally, 20–30 μl of CSF was collected from each procedure. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Boston University Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry of mouse brains

Immunohistochemistry was used to characterize the mouse brain pathology (n = 10 in each treatment group). Mouse brains were removed, post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 h, treated with 30% sucrose (in PBS) for 24 h and then embedded in Tissue-Tek optimal cutting temperature compound. Serial coronal cryosections (8–10 μm) were cut and stored at 20 °C. After air drying and washing with PBS, quenching of endogenous peroxidase activity was performed by incubating the sections for 30 min in 0.3% H2O2 in methanol followed by PBS washes.

Slides were preincubated in blocking solution (5% [vol/vol] goat serum [Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA] and 0.3% [vol/vol] Triton-X 100 in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation in Mouse on Mouse Blocking Reagent (Vector Labs, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA, MKB-2213) for 1 h. Primary antibodies against different components were incubated individually with the slides overnight. For Aβ, mouse mAb 6E10 (S1G-39320,1:300, Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA) was used, and for human pTau, AT8 (Thermal Fisher, MN1020, 1:200) was used. Antibodies against the microglial markers CD68 (mouse anti-CD68 antibody [KP1], 1:300, ab955, Abcam) and 1ba1 (rabbit anti 1ba1, 1:500, WAKO) were used for microglial immunostaining. The secondary antibodies used were biotinylated mouse antibodies (Vector Labs, Inc.; 1:500) for immunohistochemistry. 1mmunobinding of primary antibodies was detected by biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies and a Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Labs, Inc.) using DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine; Vector Labs, 1nc.) as a substrate for peroxidase and counter-staining with hematoxylin. The end products were visualized as eight-bit RBG images using N1S Elements BR 3.2 software (Software/N1S-Elements-Br-Microscope-Imaging-Software) at a total magnification of × 40.

To evaluate the immunostaining results, 1mageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) was used. After adjusting for the threshold, ImageJ was used to count all plaques and to measure the area of the plaques, average size of the plaques and the percentage of total brain area occupied by plaques. The intensity × size values of the plaques were measured by analyzing average raw gray levels of the plaques in the image, normalizing them to the background of the slide not taken up by brain and multiplying by the average size of the plaques in the image. The brain area (cortex or hippocampus or thalamus) was outlined using the edit plane function. The number of plaques in the outlined structure was also recorded. To study tauopathy, after adjusting for the threshold, ImageJ was used to count all tau-positive signals, including cell number and optical intensities. To study microglial cells, the intensity × size values of the positive microglial cells were measured by analyzing average raw gray levels of the positive cells in the image, normalizing them to the background of the slide not taken up by brain and multiplying by the average size of positive cells in the image. The brain area (cortex or hippocampus or thalamus) was outlined using the edit plane function. Tau signals were counted by cell numbers. Data were pooled from three independent readers who were blind to the treatment for all three sections and averaged.

2.3. Western blots

All Western blot experiments for each brain were replicated by two researchers in the laboratory to confirm the results. Sarkosyl-insoluble fractionation was used to separate the soluble and insoluble fractions of brain extracts from 3XTg mice (n = 10 in each treatment group) (Petrucelli et al., 2004). Briefly, 3XTg mouse brain proteins were extracted by TBS followed by fractionation into two parts: (1) the TBS-soluble fraction (S1) and (2) the sarkosyl-insoluble fraction (P3), as described. 50 μg protein were used for each Western blot. The pTau levels were visualized and quantified using Western blots with a human pTau-specific antibody, AT8, after SDS-PAGE. The levels of pTau and total tau in the soluble fractions were also determined using Western blots, and the antibodies AT8 (Thermal Fisher, MN1020,1:1000) and total Tau (Santa Cruz, sc-32274, 1:1000) respectively, were used, while the actin level was used as the control in the experiment.

We also examined endogenous tau proteins in 5XFAD mice (n = 10 in each treatment group). Total brain proteins were extracted by TBS-X extraction of hemi-brain sucrose homogenates and 50 μg protein extracts were used for each Western blot. The pTau levels were detected using the CP-13 (monoclonal, 1:2000 dilution) and PHF-1 antibodies (monoclonal, 1:4000 dilution) in Western blots. The CP-13 and PHF-1 levels were quantified and compared. For identification of the CDK5-p35-p25 pathway, Western blots were used to detect CDK5 with a specific polyclonal antibody (1:5000 dilution, Cell Signaling, MA, USA), and the p35 and p25 proteins were detected with a specific monoclonal antibody against both proteins (1:5000 dilution, Cell Signaling, MA, USA) in the 5XFAD brain extracts. The amounts of CDK5, p35 and p25 were quantified and compared.

2.4. ELISA and RT-PCR assays

Total proteins from 5XFAD brains were extracted using TBS-X extraction of hemi-brain sucrose homogenates and 20 μg were used for each enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The Aβ levels in the total protein extracts, CSF and serum were assayed after the samples were collected and centrifuged. We used an ELISA method in which Aβ was trapped with Aβ1–42 (21F12) and then detected with biotin conjugation to the N-terminus of Aβ. A dilution of 6E10 was optimized to detect Aβ in the range of 50–800 pg protein in the brain samples. The dilution of serum and CSF samples was between 2 and 5-fold; the lowest detection level for each Aβ peptide in blood was 1.6 pg/ml as determined from a standard curve. Streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added and incubated, and the signal was amplified by adding alkaline phosphatase fluorescent substrate (Promega), which was then measured. Multiplex ELISA assays were used to examine the levels of 40 cytokines in brain protein extracts, CSF and serum samples from 5XFAD mice according to the manufacturer’s protocols (RayBiotech, GA, USA). Total RNA was extracted from brain extracts using an RNA extraction solution, QIAzol Lysis Reagent, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, CA, USA). RT-PCR was used to examine the mRNA levels of CD68 and Iba-1 in the brain samples.

2.5. Behavioral tests and data analysis

All behavioral experiments were conducted by a laboratory technician blinded to the treatment and the genotype of the mice. The Y maze test with spontaneous alternation performance (n = 10 per group) was performed three times with different groups of 5XFAD and 3XTg mice after different treatments. Each mouse was placed in the center of the symmetrical Y maze and was allowed to explore freely the maze during a 5-min session. The sequence and total number of arms entered were recorded. Percentage of alternation was determined as follows: number of trials containing entries into all three arms/maximum possible alternations × 100. The maximum possible alterations = total number of arms entered − 2. Behavioral data were analyzed using t-tests to examine the differences between different treatments.

Morris water maze test with spatial learning and memory performance was used with 5XFAD mice (n = 10 per group) after the completion of treatment. All mice underwent reference memory training with a hidden platform in one quadrant of the pool for 10 days with four trials per day. After the last trial of day 10, the mice did not have the training for 48 h and at day 12, the mice underwent the memory test for the hidden platform. Then after 24 h, the platform was removed, and each mouse received one 60 s swim probe trial to examine how long each mouse spends in the “target quadrant”. Other indices, including length of swim path, swim speed, percent of time in the outer zone, and percent of time and path in each quadrant of the pool were also recorded using an HVS image video tracking system.

2.6. Statistical analyses on the mouse experiments

The outcomes in mouse experiments, including amyloid plaques, tauopathy and microglia cells as well as Y maze behavior data, were compared between either treatment regimen and PBS by using ANOVA, followed with posthoc analysis by using a Tukey or Dunnett’s test. Mean ± SE and p value statistical significance were presented. For the human brain part of this study, a t-test was used to compare two different pathological subgroups and statistical significance with p < 0.05 was presented.

2.7. Human brain study

Brain tissues from the prefrontal lobe region were obtained from the neuropathology core; demographic data, ApoE4 allele and diabetes status, and Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores before death, as well as the data from the neuropathological examination, were obtained from the data core, Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Boston University (BU ADC). Neuropathological data included Braak stage, the number of neuritic plaques stained by using Bieschowsky silver stain, and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) immunostained by a pTau-specific antibody, AT8. Total RNA was extracted from brain samples using an RNA extraction kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, CA, USA). RT-PCR was used to examine the mRNA levels of Iba-1 and CD68 in the brain samples.

3. Results

3.1. Peripheral amylin treatment reduces amyloids and tauopathy in the brain and the amylin receptor antagonist reverses the effects

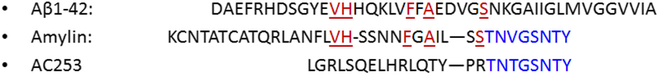

The sequences of Aβ, amylin and an amylin antagonist, AC253, are shown in Fig. 1. Although Aβ and amylin have similar secondary structure, their primary sequences are largely different. In contrast, C-terminals of amylin and AC253 are almost identical, but N-terminals of these two peptides are different. We first investigated whether amylin treatment could reduce the Aβ amyloid burden through binding to its cognate receptor. We used 5XFAD mice aged 3.5 months, which is an age when there are prominent Aβ deposits in the brain. The mice were given a 10 week course of daily i.p. injections of PBS saline, human amylin (200 μg/kg) or amylin plus equal molar concentrations of a competitive amylin receptor antagonist, AC-253 (n = 10 per group) (Fig. 2A). Amylin treatment significantly reduced the amyloid pathology in the cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 2B), using a measure for amyloid burden (average plaque size × plaque intensity) (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2C). Co-injection of amylin with AC-253 attenuated the effects of amylin on amyloid burden with statistical significance (Fig. 2B). Amylin treatment also reduced the levels of brain Aβ1–42 (p < 0.0001), as determined by ELISA; the effects of amylin on Aβ in the brain tended to be attenuated by co-injection of AC-253 (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 1. Primary amino acid sequences of Aβ, amylin and AC253.

Amino acid sequences of Aβl-42, amylin and AC253 are presented. Identical amino acids between Aβ and amylin are in red; identical amino acid sequences between amylin and AC253 are in blue. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 2. Amylin treatment reduces amyloid pathology in the brain, and an amylin receptor antagonist attenuates the effect.

5XFAD mice were used to study the effect of amylin treatment on amyloid components of AD pathology in the brain. Each treatment group had 10 mice and total brain proteins were extracted by using TBS-X extraction after completing the treatments. (A) Compared with PBS treatment, the amylin-treated mice had fewer amyloid plaques in the cortex and the hippocampus region as shown by immunostaining with an Aβ antibody, and co-treatment of amylin with AC-253 diminished the effect on the amyloid burden. (B) The amyloid burden for these mice was quantitated and calculated by the number of amyloid plaques × the size of each plaque in the brain regions and showed the group differences by using ANOVA (p < 0.0001). (C) Aβ1–42 in the brain extracts was measured by using a specific ELISA and showed the group differences by using ANOVA (p < 0.0001). The mean ± SE is shown, and statistical analyses were done on different conditions (ANOVA followed by Tukey test) to compare the PBS treatment and either the amylin or amylin plus AC253 treatment. The groups of amylin and amylin plus AC253 were also compared. Statistical significances *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

We next investigated whether amylin treatment could influence the other key component, tauopathy, in the AD brain. The first animal model used was 3xTgAD to investigate whether amylin protects against tau pathology. Beginning at 9 months, the mice were administered amylin daily (200 μg/kg, i.p.) for 10 weeks, at which point the mice were sacrificed and the brains either fixed or frozen. Quantification of tau pathology by immunostaining with the antibody AT8 (which detects phosphorylation at both S202 and pT205) showed a strong reduction of brain pathology (Fig. 3A). The results indicated that amylin treatment reduced tauopathy in the brain by approximately 50% (Fig. 3B). Next, we separated 3xTgAD brain extracts into soluble and insoluble fractions. We saw strong effects, with amylin treatment decreasing the level of AT8 reactive pTau in the insoluble fractions by over 60% after normalizing with the expression levels of actin (Fig. 3C and D, p < 0.0001).

Fig. 3. Amylin treatment reduces pTau and tauopathy in the brains of AD mouse models.

Brains from 3xTg mice (A–D) and 5XFAD mice (F–H) with different treatments were used to detect the effects of amylin on pTau and tauopathy. (A) The amygdala of 3xTg mice treated with either PBS (n = 10) or amylin (n = 10) were immunostained with the AT8 antibody. (B) Positive cells stained with AT8 in the region were counted. (C) Protein extracts from the brains were fractionated into soluble fraction by TBS extraction and insoluble fraction by the sarkosyl-extraction followed by Western blots with the AT8 antibody against pTau and quantitated. Total tau and actin in soluble fractions were detected by Western blots and are shown. (D) The quantitations of pTau in the insoluble fraction were shown. The mean ± SE is shown, and ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s testwas used to compare the PBS treatment and either the amylin in 3xTg mice (A–D). (E) Using Western blots, total brain protein extracts from 5XFAD mice treated with PBS, amylin or amylin plus AC253 (n = 10 in each treatment group) were detected with two specific antibodies, CP13 and PHF-1, against pTau, and one specific antibody against total tau. (F) Using actin expression levels as a control, the quantitation for pTau in each treatment group is shown. The ANOVA test for three group comparison was significant (p = 0.001 for CP13; p < 0.0001 for PHF-1). (G) Western blots for p35, p25 and CDK5 are shown, and (H) quantitation of p25 and CDK5 was normalized to actin levels for each treatment. The ANOVA test for three group comparison was significant (p = 0.001 for p25; p < 0.0001 for CDK5). The mean ± SE is shown, and ANOVA followed by Tukey test was used to compare the PBS treatment and either the amylin or amylin plus AC253 treatment. The groups of amylin and amylin plus AC253 were also compared. Statistical significance is shown as *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

Using the brain extracts from 5XFAD mouse model and normalizing with the expression levels of actin, similar results were observed for phosphorylated tau protein by using both antibodies, CP13 (S202) and PHF1 (S396/404), reactive pTau (Fig. 3E and F). Changed levels of soluble total tau did not reach statically significance, which suggests that amylin selectively protects against tau pathology through decreasing aggregation and phosphorylation of tau. Again, co-injection with AC-253 blocked the amylin effect on the pTau level detected by PHF1 (Fig. 3E and F, p < 0.01), indicating that the actions of amylin were mediated through the AmR.

3.2. Amylin selectively reduces activation of CDK5 pathway

The above data suggest that the AmR selectively inhibits the signaling pathway(s) that phosphorylate tau. To validate this hypothesis, we proceeded to examine effects of amylin treatment on two pathways that are putatively involved in tau phosphorylation: 1) the p35-p25-CDK5 pathway and 2) the AKT-GSK3-β pathway (Lee and Tsai, 2003). Immunoblotting lysates from the treated mice, we observed that amylin treatment dramatically decreased levels of the p25 proteins (p < 0.01), which is the cleavage product associated with CDK5 activation, after normalizing the expression levels of actin (Fig. 3G and H). Interestingly, amylin had little or no effect on AKT and GSK3-beta phosphorylation (supplement Fig. 1), suggesting that the actions of amylin were selective for the CDK5 pathway. The ability of amylin to reduce activation of the CDK5 pathway and co-injection of AC253 blocked the amylin effect on p25 (p < 0.01) supports a role for amylin in attenuating tau phosphorylation and tauopathy formation in the AD brain through binding to the AmR receptor.

3.3. Peripheral amylin treatment attenuates neuroinflammation in the AD brain

In order to determine the effects of amylin treatment on neuroinflammation in AD mouse models, two well-documented markers for activated microglia, ionized calcium-binding adaptor (Iba-1) (Ito et al., 2001) and CD68 (Sasaki et al., 1996), were examined with immunostaining. While amylin treatment significantly reduced the expression level and the number of Iba-1 + microglial cells in the cortex (p < 0.01), thalamus (p < 0.05) and hippocampus (p < 0.01), it modestly reduced the number of CD68+ microglia in the cortex (p < 0.05) of 5XFAD mice (Fig. 4A and B). Importantly, co-injection with AC253 attenuated the effects of amylin on Iba-1 expressed microglial cells in the brains of these mice (p ≤ 0.05).

Fig. 4. Amylin treatment reduces neuroinflammation in the AD brain.

Brains from 5XFAD mice (A–D) and 3XTg mice (E–H) that were treated with PBS, amylin or amylin plus AC253 (n = 10in each treatment group) were used to assess the effects of amylin on neuroinflammation. (A) Immunostaining of the brains from 5XFAD mice in different treatment groups with antibodies against Iba-1 and CD68. (B) For Iba-1 expression burden, quantitation of cell number × cell size in the whole brain is shown (ANOVA for three groups: p = 0.009 for the cortex; p = 0.11 for the thalamus and p = 0.03 for the hippocampus); for CD68, CD68+ cells in the cortex were counted and are shown. The mean ± SE is shown, and ANOVA followed by Tukey test was used to compare PBS treatment and either amylin treatment. The groups of amylin and amylin plus AC253 were also compared. (C) The 25 μg brain extracts, 10 μl CSF and 25 μl sera samples under different treatments were used for each ELISA. The amounts of INFγ in the brain extracts, CSF and sera samples under different treatments were measured by ELISA and are shown. (D) The amounts ofIL-1β the brain extracts, CSF and sera samples under different treatments were measured by ELISA and are shown. Amylin treatment tended to reduce the amount of IL-1β in the brain (p = 0.07). (E) Immunostaining of the brains from 3xTg mice with antibodies against Iba-1 or CD68 is shown. (F) While the expression burden (the number of cells × the size of each cell) of Iba-1 was reduced by amylin treatment, the expression burden of CD68 was not influenced by amylin treatment. (G) mRNA was quantitated by using RT-PCR. (H) CD68 mRNA was reduced by amylin treatment. The mean ± SE is shown, and ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used to compare PBS treatment and amylin treatment (C–G). Statistical significance is shown as *P ≤ 0.05; **P < 0.01.

We further measured and compared proinflammatory cytokines using multiplex ELISA assays and found that IFNγ (Fig. 4C) and IL-1β (Fig. 4D) levels were different between the amylin and PBS treatment groups in 5XFAD mice. Compared with PBS treatment, amylin treatment reduced the protein level of IFNγ in the brain extracts (p = 0.04) and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) (p = 0.03) but not in the serum. Amylin treatment showed a trend towards reduced the level of IL-1β in the brain extracts (p = 0.07) but not in the CSF and serum.

Next, we determined whether amylin treatment had any effects on microglial cells in 3xTgAD mice. Similar to the 5XFAD mice, amylin treatment reduced the number of Iba-1 + microglial cells in 3xTgAD mice (Fig. 4E and F), but CD68+ microglial cells were not influenced by amylin treatment. Despite not showing differences in cell density, measurement of CD68 mRNA levels indicated that amylin treatment decreased the transcriptional level of CD68 in 3xTgAD mice (Fig. 4G and H). The presence of a robust transcriptional response despite similar cell densities might reflect competing signaling by amylin and the pathological response at the protein level.

Using human brain tissues from the prefrontal lobe region (Supplement Table 1), we found that while amyloid plaques and tauopathy play key roles leading to cognitive decline in an early stage of AD, CD68 expression could have deleterious roles in the disease progression leading to clinical dementia in a late-stage of the disease (Supplement Fig. 2). Taken together, the amylin effects on the AD mouse models showed the relevance to the human AD pathology.

3.4. Peripheral amylin treatment improves learning and memory in AD mouse models in a manner dependent on the amylin receptor

Spontaneous alternation test in a Y-maze was conducted to investigate the effects of amylin on short-term memory. Amylin treatment significantly increased the average percentage of alternation in both AD mouse models, 5XFAD (p = 0.03) (Fig. 5A) and 3xTgAD mice (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5B), compared to PBS treatment. Co-injecting AC-253 with amylin in 5XFAD mice effectively reversed the amylin-mediated behavioral improvement (p = 0.03). The total number of arm visits in Y-maze test in each group did not show statistically differences (mean ± SE: 17.2 ± 2.15 in PBS vs. 19.1 ± 3.16 in amylin vs. 21.1 ± 1.67 in amylin plus AC253 groups, p = 0.17). Amylin treatment also improved more long-term spatial memory in Morris water maze test in 5XFAD mice (Fig. 7F). Escape latency (seconds) is reported in Fig. 7F. From day 8 to day 10 training, the groups of PBS and amylin treatments were separated (DF = 5, p = 0.03). After skipping the training at day 11, the two groups continued to be separated at day 12 and post 24 h after day 12 (probe trial) (DF = 3, p = 0.009). There was no difference of swimming speeds between the two treatment groups (data not shown).

Fig. 5. Amylin treatment improves short-term memory in AD mouse models.

Two AD mouse models, 5XFAD mice (A) and 3xTgAD mice (B), were used. A Y maze test was conducted with these mice after the treatment was completed, and the percentage of spontaneous alternation was recorded for each mouse. (A) 5XFAD mice (n = 10 for each treatment group) were treated with i.p. injection of PBS, amylin or amylin plus AC-253 daily for 10 weeks. ANOVA followed by Tukey test was used to compare the PBS treatment and either the amylin or amylin plus AC253 treatment. (B) 3xTgAD mice (n = 10 for each treatment group) were treated with i.p. injection of PBS or amylin daily for 10 weeks. ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used to compare PBS and amylin treatments. The average (mean ± SE) for each treatment group was calculated and p values are shown for the comparisons.

Fig. 7. Amylin treatment is specific for AD mouse models and has no effects on wild-type mice.

Wild-type (WT) mice treated with PBS vs. amylin (n = 10 in each treatment group). (A) The measurements of amyloid plaques in the cortex as shown by immunostaining with an Aβ antibody, 6E10, and (B) the amounts of Aβ1–42 in 50 μg extracted protein samples were measured by using ELISA assay. (C) Immunostaining of the brains from WT mice in different treatment groups with antibodies against Iba-1. (D) The measurements of CD68 and Iba-1 expression levels in total protein extracts (50 μg) of brain tissues were detected by using their specific antibodies in western blots and (E) quantitated. (F) The amylin treated 5XFAD mice, but not treated WT mice, illustrated improved cognition by showing shortened times in Morris water maze test in finding the hidden platform. When ANOVA analyses were used, the groups of PBS and amylin treatments were separated from day 8 to day 10 (DF = 5, p = 0.03); after skipping the training at day 11, the two groups continued to be separated at day 12 and post 24 h after day 12 (probe trial) (DF = 3, p = 0.009). Using t-test analyses, the two treatment groups in 5XFAD mice were separated at day 10 (D10) (p = 0.005), in memory at day 12 (D12) after the completion of training and skipping day 11 (p = 0.002), and in the probe trial (p = 0.03). The mean ± SE is shown. Statistical significances *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

3.5. Both agonistic and antagonistic properties of AC253 for amylin receptor

Since the C-terminal of AC253 has identical sequences as the C-terminal of amylin (Fig. 1), it is probable that AC253 could bind to the AmR and may play a role of partial agonist when using it alone; but could display both agonistic and antagonistic effects if the full ligand, amylin, is present. Indeed, AC253 (200 μg/kg) (n = 10 per group) alone treatment reduced the amyloid burden (Fig. 6A), but did not affect the expressions of PHF1 (S396/404) reactive pTau (Fig. 6B). AC253 alone also improved learning and memory measured by using Y-maze test (Fig. 6C) in 5XFAD mice. However, the effects of AC253 seemed less strong when compared to amylin treatment for 5XFAD mice. When amylin and AC253 were co-injected to the mice, it produced a net decrease in the effects observed with either amylin or AC253 alone, suggesting the antagonizing effects of AC253 in the presence of full agonist, amylin.

Fig. 6. AC253 plays a role of partial agonist and antagonist for amylin receptor in treating AD mouse model.

Compared with PBS treatment, 5XFAD mice treated with amylin, AC253 and amylin plus AC253 had the measurements of amyloid plaques in the cortex, the thalamus and the hippocampus region as shown by immunostaining with an Aβ antibody (A); had the measurements of pTau expression levels in total protein extracts of brain tissues detected by using PHF-1 antibody in western blots (B), and had a Y maze test after the treatment was completed with the percentage of alternation recorded for each mouse (C). The mean ± SE is shown, and ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test was used to compare the PBS treatment and either the amylin or AC253 or amylin plus AC253 treatment. Statistical significances *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001. When ANOVA followed by Tukey test was used, no statistical differences were found between the groups of AC253 alone and amylin + AC253.

3.6. Peripheral amylin treatment has no effect on wild-type mice

Because that Aβ and amylin share similar secondary structure (Fig. 1), it is possible that the beneficial effects of amylin treatment are specific for AD with amyloid pathology. Indeed, the same amylin treatment on WT mice did not cause amyloid pathology (Fig. 7A) and did not show any effects on the amount of Aβ1–42 (Fig. 7B). Additionally, the numbers of microglia stained by Iba-1 in the brain (Fig. 7C) and the expression levels of Iba-1 and CD68 (Fig. 7D and E) in the brain samples were similar between PBS and amylin treatments. Unlike in 5XFAD mice, peripheral amylin treatment did not change the outcomes of behavior test, Morres water maze, in WT mice (Fig. 7F). Taken together, the data suggests that the beneficial effects of amylin treatment for AD are probably through antagonizing Aβ through binding to the AmR.

4. Discussion

Recently a genome-wide interaction study showed tha a polymorphism in the amylin gene is associated with increased brain amyloid burden and cognitive impairment in AD (Roostaei et al., 2016). In addition, two studies found that AD patients have low concentrations of plasma amylin (Adler et al., 2014; Qiu and Zhu, 2014). The current study demonstrates that chronic, peripheral amylin treatment provides broad based neuroprotection acting on each of the three major arms of pathology in AD, amyloidopathy, tauopathy and inflammation. Competition experiments demonstrated that the benefits of amylin treatment in our AD models were mediated by the amylin receptor, resulting improvements in their learning and memory (Figs. 2–5). This broad based protection of amylin treatment raises the possibility that treatment with amylin or its clinically approved analogue, pramlinitide, will exhibit therapeutic utility for the treatment of AD.

Co-treatment with the amylin receptor antagonists AC253 attenuated or blocked the effects of amylin on AD, indicating a mechanism of action mediated by amylin receptor (Figs. 2–5). When used alone, AC-253 acted as a partial agonist (Fig. 6), which is consistent with the literature (Jhamandas et al., 2011; Kimura et al., 2012). Since amylin and AC253 have identical C-terminals (Fig. 1), the data suggests that AC253 has mixed antagonistic and partial agonistic effects for the amylin receptor. Amylin binds to its specific GPCR composed of the calcitonin receptor (CTR) complexed with different receptor-activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs) (Gebre-Medhin et al., 2000). Heterodimers between the CTR and either RAMP1 or RAMP3 preferentially bind amylin, and the brain predominantly expresses both RAMP1 and RAMP3 (Christopoulos et al., 1999; McLatchie et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2017). Understanding of the comparative roles of each RAMP protein is still evolving. A recent study from our laboratory demonstrates that microglia cells express only RAMP3, while other neuronal cells express both RAMP1 and RAMP3 (Wang et al., 2017). However, RAMP1 clearly has an impact on the immune system, e.g. knockout of RAMP1 produces a mouse with hypertension and a dysregulated immune response; in contrast, RAMP3 knockout mice appeared normal until old age, suggesting that RAMP3 knockout is relatively innocuous (Sexton et al., 2009). Several studies have shown that GPCRs were implicated in the pathogenesis of AD (Thathiah and De Strooper, 2011), but no specific GPCR has been identified as a target for the AD drug development. Because of the complexity of the GPCR superfamily and the overlap in GPCR signaling, it has been suggested that the rational design of ligands with increased specific efficacy and attenuated side effects may become the standard mode of drug development (Maudsley et al., 2007; Roth et al., 1998). We propose that amylin and its receptor are a specific target for the AD drug development, because amylin shares the secondary structure with both Aβ and tau (Kurnellas et al., 2013; Lim et al., 2008; Steinman et al., 2014), so that amylin can effectively rescue a GPCR pathway impacted by amyloid pathology.

The pathophysiology of AD is clearly pleitotropic, yet most attempts at disease-modification target a single component of AD pathology (Chiang and Koo, 2014; Doody et al., 2013; Imbimbo et al., 2012). The failure of clinical trials for multiple disease-modifying AD treatments inherently raises questions about the effectiveness of treatments that exclusively focus on one component/pathway. The current study (Figs. 2–5) demonstrates that amylin reduces multiple types of pathology founds in the AD brain, including amyloid pathology, aggregated p-tau and neuroinflammation, suggesting that the benefits of amylin type peptides extend beyond a simple amyloid-centric mechanism. Our studies of two main pathological pathways linked to tau, the CDK5 and GSK3β pathways, showed selective inhibition of the p35-p25-CDK5 pathway (Fig. 3)(Baumann et al., 1993; Tsai et al., 1993,1994). Taken together, we posit that amylin crosses the BBB and acts through the amylin receptor to antagonizing degenerative pathways linked to AD, providing neuroprotection for learning and memory.

Amylin treatment produced a striking reduction in inflammation in both animal models. Our data indicate that amylin treatment produced strong decreases in CD68+ and Iba-1+ (Fig. 3), both of which are accepted markers of microglia activity (Edison et al., 2008). Amylin also downregulated cytokines associated with the inflammatory response, including reductions in the expression of proinflammatory factors, such as INF-γ, in the AD mouse model brains. Although Iba-1 is present in both resting and activated microglia (Ahmed et al., 2007; Imai et al., 1996; Streit et al., 2009), its levels correlate with pTau pathology and neuronal apoptosis in the AD brain (Paquet et al., 2014; Zotova et al., 2013). CD68 is a microglial lysosomal protein that is an indicator of phagocytic activity (Rabinowitz and Gordon, 1989; Zotova et al., 2011). Human neuropathological studies show increased hippocampal expression of CD68 in AD, as well as in frontotemporal dementia (FTD) (Arnold et al., 2000). A recent study demonstrates that CD68+ and Iba-1+ microglia cells correlate with Aβ oligomers and reduced synaptic density in AD (Hong et al., 2016). The ability of amylin to reduce each of these markers demonstrates the strong anti-inflammatory actions.

The beneficial effects of amylin might be surprising to some because that some studies show neurotoxicity of amylin. While the concentration used to cause neurotoxicity in rat cortical neurons after two to four days’ exposure is 50 μM (May et al., 1993), the average fasting plasma amylin concentrations are in the range of 4–25 pmol/l in healthy humans (Nyholm et al., 1998), and the peak of amylin in the amylin treatment we conducted for the mice was ~1 nmol/l. In addition, the half-life of exogenous amylin or pramlintide is about 20–45 min in vivo (Colburn et al., 1996; Young, 2005) (our own data not shown). A recent paper demonstrates that low vs. high concentrations of amylin bind different receptors (Zhang et al., 2017). Thus the potential benefits of amylin type peptides as a neuropeptide or a drug against neurodegeneration are probably through its cognate receptor, which is a different receptor from the one binding to aggregated amylin (Qiu and Zhu, 2014).

The presence of amylin is found with amyloid deposits and the cerebrovascular system in AD (Jackson et al., 2013). However, increasing evidence suggests that while pathological deposits are good diagnostic markers for disease, they might not be the pathologically toxic species (Cohen et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2016). Amylin can have two forms, 1) monomeric amylin which can bind to the AmR and 2) aggregated amylin in the pancreas in type 2 diabetic patients (Opie, 1901) which probably cannot bind to the receptor. The amylin analog pramlintide was developed by substituting prolines at positions 25, 28 and 29 of human amylin, which prevent amylin from oligomerizing or aggregating (Roth et al., 2012). Pramlintide was approved by the FDA for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and its safe profile and successful use in clinic emphasizes the beneficial actions of amylin type peptides (Gebre-Medhin et al., 2000; Moriarty and Raleigh, 1999; Pencek et al., 2010). The importance of diabetes as a risk factor for AD (Lutz and Meyer, 2015) highlights yet another potentially beneficial action of the amylin cascade in AD. Our study suggests that pramlintide should be strongly considered for clinical testing as a repurposed amylin drug for treatment in AD (Zhu et al. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, Translational Research and Clinical Interventions, in press).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Alzheimer’s Disease Association, IIRG-13-284238; NIA, R21AG045757 and RO1AG-022476; and Ignition Award (W.Q.Q), and from BU ADC pilot grant 2011 (H.Z). Support was also provided through P30 AG13864 (N.K.).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.03.030.

References

- Adler BL, Yarchoan M, Hwang HM, Louneva N, Blair JA, Palm R, Smith MA, Lee HG, Arnold SE, Casadesus G, 2014. Neuroprotective effects of the amylin analogue pramlintide on Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and cognition. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Z, Shaw G, Sharma VP, Yang C, McGowan E, Dickson DW, 2007. Actin-binding proteins coronin-1a and IBA-1 are effective microglial markers for immunohistochemistry. J. Histochem. Cytochem. Off. J. Histochem. Soc 55, 687–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SE, Han LY, Clark CM, Grossman M, Trojanowski JQ, 2000. Quantitative neurohistological features of frontotemporal degeneration. Neurobiol. Aging 21, 913–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ, 1998. Differential permeability of the blood-brain barrier to two pancreatic peptides: insulin and amylin. Peptides 19, 883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Maness LM, Huang W, Jaspan JB, 1995. Permeability of the blood-brain barrier to amylin. Life Sci. 57, 1993–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann K, Mandelkow EM, Biernat J, Piwnica-Worms H, Mandelkow E, 1993. Abnormal Alzheimer-like phosphorylation of tau-protein by cyclin-dependent kinases cdk2 and cdk5. FEBS Lett. 336, 417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RG, Hamel FG, Duckworth WC, 2003. An insulin-degrading enzyme inhibitor decreases amylin degradation, increases amylin-induced cytotoxicity, and increases amyloid formation in insulinoma cell cultures. Diabetes 52, 2315–2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang K, Koo EH, 2014. Emerging therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 54, 381–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos G, Perry KJ, Morfis M, Tilakaratne N, Gao Y, Fraser NJ, Main MJ, Foord SM, Sexton PM, 1999. Multiple amylin receptors arise from receptor activity-modifying protein interaction with the calcitonin receptor gene product. Mol. Pharmacol 56, 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Paulsson JF, Blinder P, Burstyn-Cohen T, Du D, Estepa G, Adame A, Pham HM, Holzenberger M, Kelly JW, Masliah E, Dillin A, 2009. Reduced IGF-1 signaling delays age-associated proteotoxicity in mice. Cell 139, 1157–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colburn WA, Gottlieb AB, Koda J, Kolterman OG, 1996. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics ofAC137(25,28,29 tripro-amylin, human) after intravenous bolus and infusion doses in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes. J. Clin. Pharmacol 36, 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppock HA, Owji AA, Austin C, Upton PD, Jackson ML, Gardiner JV, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR, Smith DM, 1999. Rat-2 fibroblasts express specific adrenomedullin receptors, but not calcitonin-gene-related-peptide receptors, which mediate increased intracellular cAMP and inhibit mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. Biochem. J 338 (Pt 1), 15–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Tullio MB, Castelletto V, Hamley IW, Martino Adami PV, Morelli L, Castano EM, 2013. Proteolytically inactive insulin-degrading enzyme inhibits amyloid formation yielding non-neurotoxic abeta peptide aggregates. PloS One 8, e59113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody RS, Raman R, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, Kieburtz K, He F, Sun X, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Siemers E, Sethuraman G, Mohs R, 2013. A phase 3 trial of semagacestat for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med 369, 341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edison P, Archer HA, Gerhard A, Hinz R, Pavese N, Turkheimer FE, Hammers A, Tai YF, Fox N, Kennedy A, Rossor M, Brooks DJ, 2008. Microglia, amyloid, and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease: an [11C](R)PK11195-PET and [11C]PIB-PET study. Neurobiol. Dis 32, 412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvinsson L, Goadsby PJ, Uddman R, 2001. Amylin: localization, effects on cerebral arteries and on local cerebral blood flow in the cat. Sci. World J 1, 168–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W, Ruangkittisakul A, MacTavish D, Shi JY, Ballanyi K, Jhamandas JH, 2012. Amyloid beta (Abeta) peptide directly activates amylin-3 receptor subtype by triggering multiple intracellular signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem 287, 18820–18830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebre-Medhin S, Olofsson C, Mulder H, 2000. Islet amyloid polypeptide in the islets of Langerhans: friend or foe? Diabetologia 43, 687–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ, 2002. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Sci. (New York, NY) 297, 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DL, Chen S, Lutz TA, Parkes DG, Roth JD, 2015. Amylin: pharmacology, physiology, and clinical potential. Pharmacol. Rev 67, 564–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Beja-Glasser VF, Nfonoyim BM, Frouin A, Li S, Ramakrishnan S, Merry KM, Shi Q, Rosenthal A, Barres BA, Lemere CA, Selkoe DJ, Stevens B, 2016. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Sci. (New York, NY) 352, 712–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Ibata I, Ito D, Ohsawa K, Kohsaka S, 1996. A novel gene iba1 in the major histocompatibility complex class III region encoding an EF hand protein expressed in a monocytic lineage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 224, 855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbimbo BP, Ottonello S, Frisardi V, Solfrizzi V, Greco A, Seripa D, Pilotto A, Panza F, 2012. Solanezumab for the treatment of mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol 8, 135–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito D, Tanaka K, Suzuki S, Dembo T, Fukuuchi Y, 2001. Enhanced expression of Iba1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1, after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rat brain. Stroke; a J. Cereb. Circ 32, 1208–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K, Barisone GA, Diaz E, Jin LW, Decarli C, Despa F, 2013. Amylin deposition in the brain: a second amyloid in Alzheimer disease? Ann. Neurol 74, 517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhamandas JH, Li Z, Westaway D, Yang J, Jassar S, MacTavish D, 2011. Actions of beta-amyloid protein on human neurons are expressed through the amylin receptor. Am. J. Pathol 178, 140–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura R, MacTavish D, Yang J, Westaway D, Jhamandas JH, 2012. Beta amyloid-induced depression of hippocampal long-term potentiation is mediated through the amylin receptor. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci 32, 17401–17406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurnellas MP, Adams CM, Sobel RA, Steinman L, Rothbard JB, 2013. Amyloid fibrils composed of hexameric peptides attenuate neuroinflammation. Sci. Transl. Med 5, 179ra142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Tsai LH, 2003. Cdk5: one of the links between senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles? J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 5,127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VM, Brunden KR, Hutton M, Trojanowski JQ, 2011. Developing therapeutic approaches to tau, selected kinases, and related neuronal protein targets. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 1, a006437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YA, Ittner LM, Lim YL, Gotz J, 2008. Human but not rat amylin shares neurotoxic properties with Abeta42 in long-term hippocampal and cortical cultures. FEBS Lett. 582, 2188–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz TA, 2013. The interaction of amylin with other hormones in the control of eating. Diabetes, Obes. Metab 15, 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz TA, Meyer U, 2015. Amylin at the interface between metabolic and neurodegenerative disorders. Front. Neurosci 9, 216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maudsley S, Martin B, Luttrell LM, 2007. G protein-coupled receptor signaling complexity in neuronal tissue: implications for novel therapeutics. Curr. Alzheimer Res 4, 3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PC, Boggs LN, Fuson KS, 1993. Neurotoxicity of human amylin in rat primary hippocampal cultures: similarity to Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta neurotoxicity. J. Neurochem 61, 2330–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLatchie LM, Fraser NJ, Main MJ, Wise A, Brown J, Thompson N, Solari R, Lee MG, Foord SM, 1998. RAMPs regulate the transport and ligand specificity of the calcitonin-receptor-like receptor. Nature 393, 333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mietlicki-Baase EG, 2016. Amylin-mediated control of glycemia, energy balance, and cognition. Physiol. Behav [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty DF, Raleigh DP, 1999. Effects of sequential proline substitutions on amyloid formation by human amylin20–29. Biochem. (Mosc) 38, 1811–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi M, Sanke T, Seino S, Eddy RL, Fan YS, Byers MG, Shows TB, Bell GI, Steiner DF, 1989. Human islet amyloid polypeptide gene: complete nucleotide sequence, chromosomal localization, and evolutionary history. Mol. Endocrinol. Baltim. Md) 3, 1775–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyholm B, Fineman MS, Koda JE, Schmitz O, 1998. Plasma amylin immuno-reactivity and insulin resistance in insulin resistant relatives of patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Horm. Metab. Res. = Horm.-Stoffwechs. = Horm. metab 30, 206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, Guillozet-Bongaarts A, Ohno M, Disterhoft J, Van Eldik L, Berry R, Vassar R, 2006. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci 26, 10129–10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM, 2003. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron 39, 409–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M, Herrington MK, Reidelberger RD, Permert J, Arnelo U, 2007. Comparison of the effects of chronic central administration and chronic peripheral administration of islet amyloid polypeptide on food intake and meal pattern in the rat. Peptides 28, 1416–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opie EL, 1901. On the relation of chronic interstitial pancreatitis to the Islands of Langerhans and to diabetes melutus. J. Exp. Med 5, 397–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquet C, Amin J, Mouton-Liger F, Nasser M, Love S, Gray F, Pickering RM, Nicoll JA, Holmes C, Hugon J, Boche D, 2014. Effect of active Abeta immunotherapy on neurons in human Alzheimer’s disease. J. Pathol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pencek R, Roddy T, Peters Y, De Young MB, Herrmann K, Meller L, Nguyen H, Chen S, Lutz K, 2010. Safety of pramlintide added to mealtime insulin in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: a large observational study. Diabetes, Obes. Metab 12, 548–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrucelli L, Dickson D, Kehoe K, Taylor J, Snyder H, Grover A, De Lucia M, McGowan E, Lewis J, Prihar G, Kim J, Dillmann WH, Browne SE, Hall A, Voellmy R, Tsuboi Y, Dawson TM, Wolozin B, Hardy J, Hutton M, 2004. CHIP and Hsp70 regulate tau ubiquitination, degradation and aggregation. Hum. Mol. Genet 13, 703–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WQ, Au R, Zhu H, Wallack M, Liebson E, Li H, Rosenzweig J, Mwamburi M, Stern RA, 2014. Positive association between plasma amylin and cognition in a homebound elderly population. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WQ, Walsh DM, Ye Z, Vekrellis K, Zhang J, Podlisny MB, Rosner MR, Safavi A, Hersh LB, Selkoe DJ, 1998. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates extracellular levels of amyloid beta-protein by degradation. J. Biol. Chem 273, 32730–32738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WQ, Zhu H, 2014. Amylin and its analogs: a friend or foe for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease? Front. aging Neurosci 6, 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz S, Gordon S, 1989. Differential expression of membrane sialoglyco-proteins in exudate and resident mouse peritoneal macrophages. J. Cell Sci 93 (Pt 4), 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roostaei T, Nazeri A, Felsky D, De Jager PL, Schneider JA, Pollock BG, Bennett DA, Voineskos AN, 2016. Genome-wide interaction study of brain beta-amyloid burden and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Psychiatry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL, Willins DL, Kroeze WK, 1998. G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) trafficking in the central nervous system: relevance for drugs of abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 51, 73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JD, Erickson MR, Chen S, Parkes DG, 2012. GLP-1R and amylin agonism in metabolic disease: complementary mechanisms and future opportunities. Br. J. Pharmacol 166,121–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JD, Roth JD, Erickson MR, Chen S, Parkes DG, 2013. Amylin and the regulation of appetite and adiposity: recent advances in receptor signaling. neurobiology and pharmacology. GLP-1R and amylin agonism in metabolic disease: complementary mechanisms and future opportunities. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes, Obes 20, 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A, Nakazato Y, Ogawa A, Sugihara S, 1996. The immunophenotype of perivascular cells in the human brain. Pathol. Int 46,15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton PM, Poyner DR, Simms J, Christopoulos A, Hay DL, 2009. Modulating receptor function through RAMPs: can they represent drug targets in themselves? Drug Discov. today 14, 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Joachimiak A, Rosner MR, Tang WJ, 2006. Structures of human insulindegrading enzyme reveal a new substrate recognition mechanism. Nature 443, 870–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman L, Rothbard JB, Kurnellas MP, 2014. Janus faces of amyloid proteins in neuroinflammation. J. Clin. Immunol 34 (Suppl. 1), S61–S63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit WJ, Braak H, Xue QS, Bechmann I, 2009. Dystrophic (senescent) rather than activated microglial cells are associated with tau pathology and likely precede neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Berl 118, 475–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thathiah A, De Strooper B, 2011. The role of G protein-coupled receptors in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 12, 73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevaskis JL, Turek VF, Wittmer C, Griffin PS, Wilson JK, Reynolds JM, Zhao Y, Mack CM, Parkes DG, Roth JD, 2010. Enhanced amylin-mediated body weight loss in estradiol-deficient diet-induced obese rats. Endocrinology 151, 5657–5668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai LH, Delalle I, Caviness VS Jr., Chae T, Harlow E, 1994. p35 is a neural-specific regulatory subunit of cyclin-dependent kinase 5. Nature 371, 419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai LH, Takahashi T, Caviness VS Jr., Harlow E, 1993. Activity and expression pattern of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 in the embryonic mouse nervous system. Dev. Camb. Engl 119,1029–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E, Zhu H, Wang X, Gower AC, Wallack M, Blusztajn JK, Kowall N, Qiu WQ, 2017. Amylin treatment reduces neuroinflammation and ameliorates abnormal patterns of gene expression in the cerebral cortex of an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 56, 47–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall TC, Curfman-Falvey M, 1995. Amylin-induced relaxation of the perfused mesenteric arterial bed: meditation by calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors. J. Cardiovasc Pharmacol 26, 932–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A, 2005. Central nervous system and other effects. Adv. Pharmacol. (San Diego, Calif) 52, 281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Yang S, Wang C, Zhang J, Huo L, Cheng Y, Wang C, Jia Z, Ren L, Kang L, Zhang W, 2017. Multiple target of hAmylin on rat primary hippocampal neurons. Neuropharmacology 113, 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Wang X, Wallack M, Li H, Carreras I, Dedeoglu A, Hur JY, Zheng H, Li H, Fine R, Mwamburi M, Sun X, Kowall N, Stern RA, Qiu WQ, 2015. Intraperitoneal injection of the pancreatic peptide amylin potently reduces behavioral impairment and brain amyloid pathology in murine models of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Psychiatry 20, 252–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotova E, Bharambe V, Cheaveau M, Morgan W, Holmes C, Harris S, Neal JW, Love S, Nicoll JA, Boche D, 2013. Inflammatory components in human Alzheimer’s disease and after active amyloid-beta42 immunization. Brain a J. neurol 136, 2677–2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotova E, Holmes C, Johnston D, Neal JW, Nicoll JA, Boche D, 2011. Microglial alterations in human Alzheimer’s disease following Abeta42 immunization. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol 37, 513–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.