Abstract

Objectives:

In 2015, Malawi piloted the HIV diagnostic assistant (HDA), a cadre of lay health workers focused primarily on HIV testing services. Our objective is to measure the effect of HDA deployment on country-level HIV testing measures.

Design:

Interrupted time series analysis of routinely collected data to assess immediate change in absolute numbers and longitudinal changes in trends.

Methods:

Data from all HDA sites were divided into two periods: predeployment (October 2013 to June 2015) and postdeployment (July 2015 to December 2017). Monthly rates of several key HIV testing measures were evaluated: HIV testing, including all tests done, new positives, and confirmatory testing. Syphilis testing at antenatal clinic (ANC) and early infant diagnosis were also assessed.

Findings:

The number of patients tested for HIV per month increased after HDA deployment across all sex, age, and testing subgroups. The number of tests immediately increased by 35 588 (P = 0.031), and the postintervention trend was significantly greater than the preintervention slope (+3442 per month, P = 0.001). Of 7.4 million patients tested for HIV in the postdeployment period, 2.6 million (34%) were attributable to the intervention. The proportion of new positives receiving confirmatory tests increased from 28% preintervention to 98% postintervention (P < 0.0001). Syphilis testing rates at ANC improved, with 98% of all tests attributable to HDA deployment. The number and proportion of infants receiving DNA-PCR testing at 2 months experienced significant trend increases (P < 0.0001).

Interpretation:

HDA deployment is associated with significant increases in total HIV testing, identification of new positives, confirmatory testing, syphilis testing at ANC, and early infant diagnosis testing.

Keywords: Africa, healthcare, healthcare human resources, HIV diagnostic tests, models/projections

Introduction

The UNAIDS 90–90–90 targets call for 90% of all people living with HIV to know their status, 90% of people diagnosed with HIV to receive antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90% of those on ART to be virally suppressed by 2020 [1]. In regions with a generalized epidemic, achieving these targets requires providing HIV testing services (HTS) frequently and reliably to large groups of individuals. Only by ensuring consistent and widespread access to HIV testing can the downstream outcomes in the HIV treatment cascade be realized.

This has been proven to be challenging in high-burden settings, where human resources are often limited. Of all the ‘90's,’ the first 90 – the proportion of people living with HIV who know their status – has seen the slowest increase [2]. Although highly accurate point-of-care rapid tests are now widely available, testing still relies on the foundational elements of any health system – namely, adequate infrastructure and a pool of trained healthcare workers – that are often in short supply in countries bearing the heaviest burden [3,4].

Since the beginning of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa, control efforts have been defined by shortages of healthcare workers [4]. This prompted innovative solutions through task-shifting of responsibilities – the delegation of medical responsibilities to health workers with less formal training. Examples of this include the provision of ART by nurses instead of doctors, and the deployment of lay counsellors to perform HIV testing and counselling. Task shifting has been a cornerstone in the success of the response to the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa [5,6].

Malawi, a country of 19 million in sub-Saharan Africa, has a strong track record of innovative task shifting. The use of lay counselors has been a cornerstone of this innovation and has allowed Malawi to rapidly and efficiently scale up HTS and ART services [7–9]. However, lay counselors often have other competing responsibilities, and many providers cite an inadequate number of trained counselors as a major barrier to testing more patients [10]. To further improve HTS, Malawi introduced the HIV diagnostic assistant (HDA), a specialized cadre that would focus on HIV diagnostic testing. By limiting the scope of responsibilities, the aim was to develop a cadre of health workers that could be rapidly trained and deployed, who would focus on HIV testing services without competing clinical demands.

There is no published evidence describing the impact of this cadre on HIV testing measures in Malawi. We aimed to explore whether HDA deployment has affected the trend and level of key HTS measures.

Methods

Setting

Malawi is a resource-limited landlocked country of 19 million people in sub-Saharan Africa [11]. The HIV prevalence is 10.6%. Of HIV-positive adults, an estimated 73% know their status, and of these 87% report current ART use. Among those on ART, 91% are virally suppressed [12].

HIV-related services in Malawi

The Malawi Ministry of Health (MOH) Department of HIV/AIDS (DHA) was established in 2001 and supports the provision of HIV testing services (HTS) at 761 facilities country-wide. Current guidelines recommend offering HIV testing to all adults attending health facilities for any reason, unless they were tested in the last 3 months or are already confirmed to be HIV-positive. Most tests are done at the point-of-care using whole blood obtained by fingerprick, following a serial testing algorithm using antibody-based tests (Determine 1/2 followed by Uni-Gold, if positive). Testing falls into several categories: provider-initiated testing and counselling (PITC), an opt-out approach to testing in which a health provider (lay or professional) initiates testing in an individual; family referral slip (FRS) in which a client accesses HIV testing services after being invited by a family member or sexual contact who has previously undergone HIV testing; and voluntary testing and counselling, where individuals request testing.

Confirmatory testing is recommended prior to ART initiation using the same tests in parallel. Eligibility to receive ART was limited to the following conditions prior to August 2016: CD4+ cell count 500 cells/μl or less or WHO clinical stage 3 or 4 condition; pregnant and breastfeeding women; children under 5 years of age. Expansion to universal treatment eligibility began gradually in August 2016. First-line treatment is a single fixed-dose combination of efavirenz, tenofovir, and lamivudine.

Other services coordinated by DHA include early infant diagnosis and syphilis testing at antenatal clinic (ANC). Infants born to HIV-infected mothers are recommended to receive DNA-PCR testing by 2 months of age by dried blood spot (DBS). Samples are transported to central reference laboratories for analysis. Guidelines call for syphilis testing of all pregnant women presenting for ANC at least once during pregnancy, and is done by Determine syphilis rapid tests.

HIV diagnostic assistant deployment

Planning and deployment of HDAs was done by the DHA and other nongovernmental partners and was not part of a planned study. HDAs were recruited according to selection criteria outlined in the 2015 Malawi HIV Testing and Counseling Guidelines, including a minimum education level of a high-school degree equivalent, at least 18 years of age, 1-year working experience in Malawi. HDAs were required to complete 3 weeks of didactic training and 1 week of practical training. The 3 weeks of classroom theory cover a range of topics including HDA roles and responsibilities, essentials of HIV testing and counseling, patient confidentiality, and documentation. Practical training consists of a week of laboratory technician-supervised attachments to health facilities, with observations of HIV testing and counseling encounters by experienced providers as well as observations of trainees’ provision of HIV testing and counseling, proficiency testing, and quality control sessions. HDAs are responsible for a range of activities in addition to provision of rapid HIV and syphilis tests. These additional duties include collection of blood samples for early infant diagnosis (EID) and viral load as well as sample tracking, delivery of results, documentation, supply chain monitoring, and quality assurance for rapid HIV and syphilis testing, EID, and viral load testing.

Deployment began in July 2015. HDAs are seconded to health facilities by nongovernmental organizations, with salary ranges recommended by DHA and MOH to align HDA salaries with those of other similar government-supported lay cadres. Performance is monitored by facility and district-level HTC supervisors in addition to DHA-led quarterly supervisions.

Sites were prioritized for deployment by DHA through a participatory approach in consultation with implementing partners. Sites were prioritized according to the estimated potential to increase HTS and new ART initiations based on the performance during the preceding period and projected burden of HIV in the facility's catchment area. The number of HDAs deployed by site was determined through a consultative process with DHA based on a combination of factors: facility cohort size, gap to reaching facility HIV testing targets, the number of clinical service delivery points requiring access to HTS, and ensuring a minimum staffing level of two HDAs per facility. This resulted in the gradual deployment over a 1-year period of 2–10 HDAs per site. Overall, an estimated 1159 HDAs were deployed to 457 (60%) of 761 facilities across all districts of Malawi, resulting in approximately 6.4 HDAs per 100 000 population. Other than the shift to universal ART eligibility in August 2016, no major policy shifts occurred during the study period that would plausibly affect testing measures.

Data sources

Details of all adult HIV testing, including characteristics of the patient (age, sex) and test result (new negative, confirmatory positive, etc.), are recorded in dedicated paper registers at each site. ART, syphilis testing, and DNA-PCR testing are recorded in a similar fashion in corresponding dedicated registers. On a quarterly basis, the DHA performs site supervision during which data for the preceding quarter is aggregated and reported in publicly available datasets. Data concerning ART is aggregated by quarter, whereas all other measures are by month. For HIV testing, we excluded all testing not performed at the facility (e.g. community outreach or standalone testing sites) because the HDA cadre was conceptualized to be facility-based. This study did not require ethical approval.

On the basis of the terms of reference for the HDA position, we focused our analysis on several key measures that the cadre would plausibly affect: all HIV testing; other diagnostic testing (confirmatory HIV testing, syphilis testing at ANC, DNA-PCR for infants at age 2 months); and new ART initiations. We also evaluated yield of testing and the proportion of individuals who have previously been tested (defined as individuals who self-reported ever having been tested).

Empirical strategy

We used panel data containing sequential monthly information before compared with after HDA deployment. Our sample was divided into two distinct periods: before implementation (October 2013 to June 2015) and after (July 2015 to December 2017). This resulted in 51 monthly time points for all measures except ART initiations, for which data is aggregated quarterly, and 17 time points were available. Total testing measures were aggregated for all deployment sites. We used all available data, and as a result, data is not distributed equally before and after implementation.

We evaluated HDA deployment through single-group interrupted time series analysis (ITSA) using ordinary least-squares regression and Newey–West standard errors. ITSA is a quasi-experimental regression-based approach that allows assessment of an intervention's effect on both the level and trend of health system metrics, and accounts for preexisting trends [13]. This approach is termed interrupted time-series analysis as the intervention is expected to ‘interrupt’ the trend and/or level of the outcome variable. By analyzing the effect on the linear trend of the outcome variable, this approach can quantify a deflection that an intervention has on the slope of the outcome of interest. In this way, ITSA measures not only the immediate change in the outcome after implementation but also the more durable effect on long-term trends. In this article, a change in trend refers to the difference in slope associated with the intervention, whereas a change in level refers to a change in the absolute number of the outcome variable.

This approach was selected because of the increasing trend of most measures predeployment that could predispose to type I error with simple preintervention/postintervention measures alone. Single-group analysis was chosen as it can estimate causality in the absence of an appropriate control group. A control group was not available in our study as the deliberate selection of sites for HDA deployment resulted in significant differences between deployment and nondeployment sites (data not shown).

Our hypothesis was that testing measures would experience a small increase in level followed by a gradual long-term improvement in testing trends as HDAs became integrated as facility staff and new HDAs were trained and deployed. We used the following equation for analysis:

where Yt is the monthly rate of each measure at time point t. Tt is the time since the beginning of the study, and Xt is a dummy binary variable for the intervention, such that Xt = 0 and Xt = 1 during predeployment and postdeployment periods, respectively. XtTt is an interaction term. β0 is the level of the corresponding measure at the beginning of study period, β1 is the predeployment slope, β2 is the change in level immediately after deployment, and β3 is the difference in trend after deployment. The postdeployment slope is equivalent to β1 + β3.

The trend of testing measures before implementation projected into the postintervention period represents the counterfactual outcome, had HDAs not been deployed. Finally, we estimated the total number of excess tests that occurred after the onset of HDA deployment by projecting the predeployment trend into the postdeployment period, and calculating the difference between these values and the fitted postdeployment regression. All calculations were done in Stata Special Edition version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

We included all available data from 457 HDA sites that reported monthly facility-level data during the 51-month study period, resulting in 22 670 observations. The average number of sites reporting monthly data was higher in the postdeployment period (447 vs. 440, P < 0.0001). Most sites (94%, 431/457) were public facilities, the majority (60%, 273/457) were located in the Southern Region, and the mean catchment area population was 29 100 [95% confidence interval (CI) 26 600–31 600).

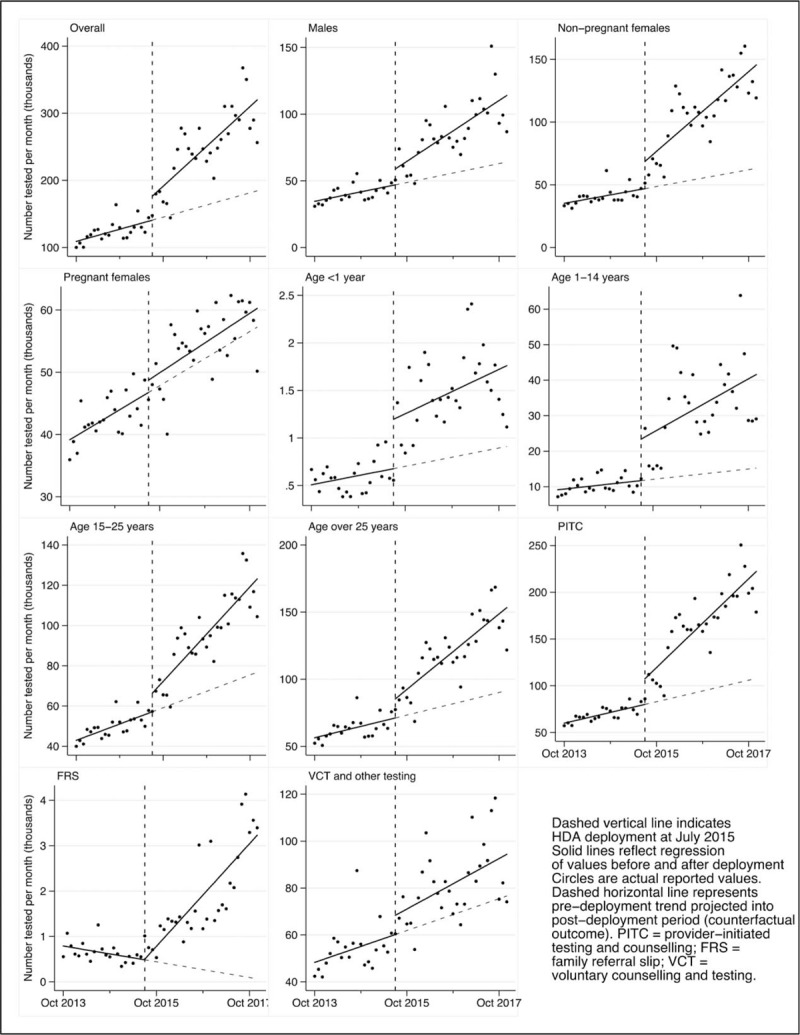

Among sites that reported data both before and after HDA deployment, 96% (436/452) of intervention sites experienced higher average monthly testing numbers in the postintervention period, a difference that was significant at 92% (399/436) of these sites. The number of patients tested monthly increased after the deployment across all sexes, age groups, and testing types (Fig. 1). The trend for all patients increased by 3442 (P = 0.001) with an immediate increase in level of 35 588 (P = 0.031; Table 1). Of the estimated 7.4 million patients tested for HIV in the postdeployment period, 2.6 million of these (34%) were attributable to the intervention (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Number of patients tested for HIV.

Table 1.

Monthly HIV testing trends before and after HIV diagnostic assistant deployment.

| Trend before deployment | Trend after deployment | Trend difference | p | Level difference | p | |

| Patients tested for HIV overall | 1508 | 4950 | 3442 | 0.001 | 35588 | 0.031 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 589 | 1901 | 1312 | 0.006 | 11913 | 0.063 |

| Female nonpregnant | 558 | 2652 | 2095 | <0.0001 | 21699 | 0.017 |

| Female pregnant | 362 | 397 | 35 | 0.804 | 1975 | 0.381 |

| Age category | ||||||

| Less than 1 year | 8 | 19 | 11 | 0.331 | 519 | 0.002 |

| 1–14 years | 122 | 628 | 506 | 0.102 | 11700 | 0.024 |

| 15–25 years | 677 | 1958 | 1282 | <0.0001 | 9185 | 0.058 |

| Older than 25 years | 702 | 2344 | 1643 | <0.0001 | 14183 | 0.045 |

| Type of testing | ||||||

| PITC | 956 | 3959 | 3002 | <0.0001 | 27403 | 0.011 |

| FRS | −14 | 94 | 108 | <0.0001 | 14 | 0.934 |

| VCT and other | 566 | 897 | 331 | 0.442 | 8172 | 0.212 |

| New positive results | 6 | −11 | −17 | 0.736 | 2050 | 0.011 |

| Confirmatory tests done | 49 | 279 | 230 | 0.002 | 3485 | 0.006 |

| Percentage previously tested | 0.22 | 0.2 | −0.02 | 0.781 | −1.3 | 0.214 |

| Yield of testing | −0.08 | -0.1 | −0.02 | 0.244 | −0.18 | 0.357 |

| New ART initiations | 118 | 694 | 576 | 0.336 | 234 | 0.933 |

| ANC patients tested for syphilis | −120 | 1229 | 1349 | <0.0001 | 6640 | 0.001 |

| New positive syphilis results | −0.2 | 10.6 | 10.8 | <0.0001 | 63 | 0.04 |

| Number of infants receiving DNA-PCR by 2 months | 1 | 67 | 65 | <0.0001 | −266 | 0.05 |

| Percentage of infants receiving DNA-PCR by 2 months | −0.26 | 1.77 | 2.02 | <0.0001 | −5.2 | 0.225 |

Note that change in trend refers to difference in slope associated with the intervention. Change in level refers to immediate change in absolute number of the outcome variable when the intervention was introduced. ANC, antenatal clinic; ART, antiretroviral therapy; FRS, family referral slip; HAD, HIV diagnostic assistant; PITC, provider-initiated testing and counselling; VCT, voluntary counselling and testing.

Table 2.

Total HIV testing attributable to intervention.

| Total postdeployment n | Amount attributable to deployment n (% of total) | |||||

| Patients tested for HIV overall | 7 442 327 | 2 564 910 (34%) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 2 594 403 | 928 211 (36%) | ||||

| Female nonpregnant | 3 212 966 | 1 562 089 (49%) | ||||

| Female pregnant | 1 634 958 | 74 611 (5%) | ||||

| Age category | ||||||

| Less than 1 year | 44 359 | 20 531 (46%) | ||||

| 1–14 years | 975 039 | 571 273 (59%) | ||||

| 15–25 years | 2 842 042 | 833 091 (29%) | ||||

| Older than 25 years | 3 580 887 | 1 140 017 (32%) | ||||

| Type of testing | ||||||

| PITC | 4 945 938 | 2 128 114 (43%) | ||||

| FRS | 55 964 | 47 700 (85%) | ||||

| VCT and other | 2 440 425 | 389 097 (16%) | ||||

| New positive results | 321 857 | 54 272 (17%) | ||||

| Confirmatory tests done | 318 279 | 204 611 (64%) | ||||

| New ART initiations | 287 033 | 28 262 (10%) | ||||

| ANC patients tested for syphilis | 803 667 | 785 794 (98%) | ||||

| New positive syphilis results | 10 577 | 6559 (62%) | ||||

| Infants receiving DNA-PCR by 2 months | 47 689 | 20 420 (43%) | ||||

ANC, antenatal clinic; ART, antiretroviral therapy; FRS, family referral slip; HDA, HIV diagnostic assistant; PITC, provider-initiated testing and counselling; VCT, voluntary counselling and testing.

Testing trends among men and nonpregnant women – but not pregnant women – increased significantly. Further analysis demonstrated that at the time of deployment, 91% of pregnant women attending ANC had their HIV status ascertained (data not shown). Among all patients tested during the postdeployment period, 36% of testing in men (0.9 million/2.6 million) and 49% in nonpregnant women (1.6 million/ 3.2 million) was attributable to HDA deployment.

Analysis by age category demonstrated that the 15–25 and over 25 age categories both experienced highly significant increases in testing trends. Testing among children less than 1 year and between 1 and 14 years exhibited significant increases in level (519 and 11 700, P = 0.002 and P = 0.024, respectively) but not trend. Subgroup analysis of type of testing demonstrated that PITC exhibited the largest and most significant increase in trend associated with deployment (3002, P < 0.0001) compared with family referral slip testing (FRS) and voluntary counselling and testing (VCT).

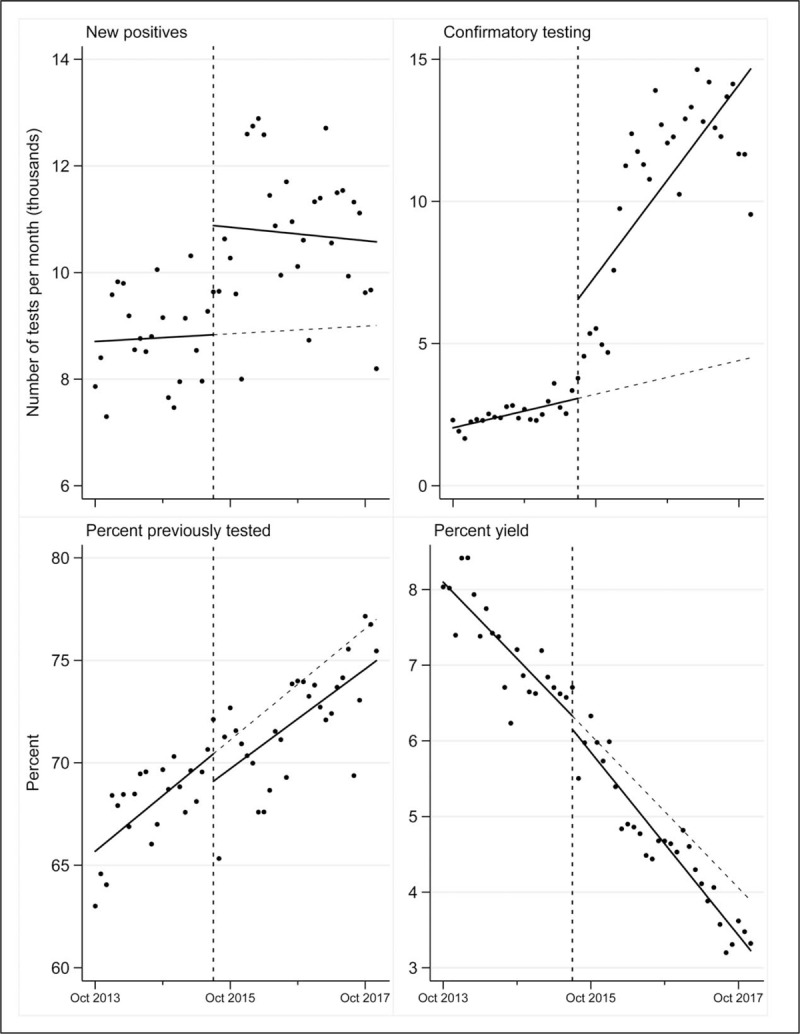

The trend of monthly new positives experienced an immediate increase of 2050 (P = 0.011) and was sustained at this level throughout postdeployment period; no significant change in trend was observed (Fig. 2). Of all new positive tests in the postdeployment period, approximately one in five (54 272/321 857, 17%) was attributable to the intervention. Both the trend and level of confirmatory testing experienced significant increases, and 64% (204 611/318 279) of all confirmatory testing in the postdeployment period was attributable to the intervention. The estimated proportion of new positives that received confirmatory testing increased significantly after deployment (28 vs. 98%, P < 0.0001). The yield of testing decreased, and the percentage of patients previously tested increased throughout the study period; neither of these measures were affected by deployment.

Fig. 2.

Other testing measures.

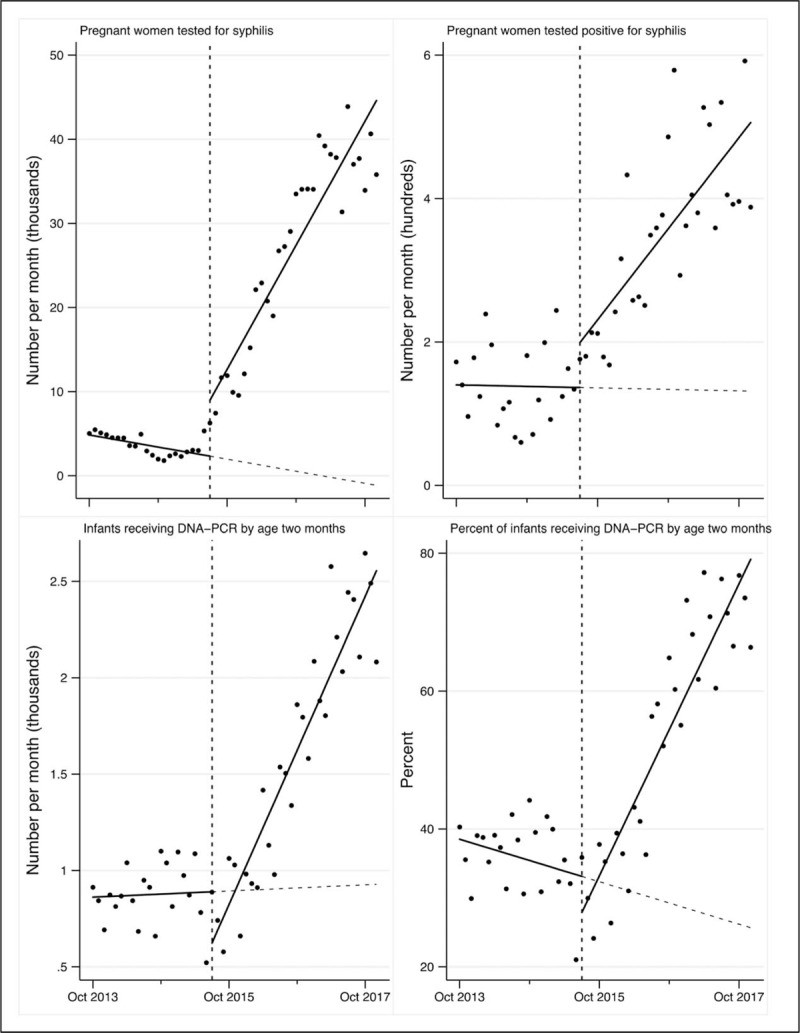

The trend of pregnant women tested for syphilis monthly at ANC clinic increased by 1349 (P < 0.0001), and the trend of those testing positive also increased by 11 (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3). Almost all (98%, 785 794/803 667) of syphilis testing in the postintervention period was attributable to HDA deployment. The number and proportion of infants receiving DNA-PCR testing at 2 months experienced trend increases, but visual inspection suggests there was a delay in this effect (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Syphilis testing at ANC and DNA-PCR testing for exposed infants.

Regression of quarterly ART initiations was limited by fewer time points (ART data is reported quarterly, not monthly like HIV testing data) and significant dispersion of values. No significant predeployment or postdeployment trend was able to be calculated (P = 0.768 and P = 0.115, respectively); as a result, the effect of the deployment was not significant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the impact of the HDA cadre on HIV and other diagnostic testing. Our findings suggest that HDA deployment has led to significant gains in overall HIV testing, identification of new positives, confirmatory testing, syphilis testing at ANC, and DNA-PCR at 2 months for early infant diagnosis.

Among patients tested for HIV, men and nonpregnant women saw the most significant gains, whereas measures in pregnant women did not exhibit a significant increase. This likely reflects the excellent coverage already achieved at ANC clinic, as 91% of pregnant women had their HIV status ascertained when HDAs were deployed.

Although new positive tests did not exhibit a significant increase in trend, deployment was associated with an increase in level that was sustained throughout the postdeployment period. In other words, deployment led to higher numbers of new positive test results per month that was sustained throughout the postintervention period. This occurred despite a decrease in yield during the study period, from 8% in 2013 to 3% in 2017, and is likely a consequence of an increased amount of HIV testing. These findings highlight the challenges of a maturing HIV epidemic in Malawi, where considerable increases in total HIV testing is required to maintain a given rate of new positive diagnoses.

The declining yield of HIV testing highlights the importance of confirmatory testing. As yield decreases, so does the test's positive predictive value, and the likelihood of a false positive diagnosis increases. Our study suggests that the response to the changing nature of the HIV epidemic in Malawi has matured, with almost all new positives receiving a confirmatory test during the postdeployment period, compared with roughly one in four predeployment. Further, almost two-thirds of all confirmatory testing in the postdeployment period was attributable to the intervention.

Some of the most impressive gains were made in testing of pregnant women for syphilis. Almost all syphilis testing in the postdeployment period was attributable to HDAs, and the change in trend was highly associated with HDA deployment (P < 0.0001). This notable increase in testing led to a significant increase in the number of syphilis-positive clients identified at ANC clinic, and for the first time the reported proportion of positive syphilis results is close to that projected based on surveillance data [14]. HIV testing coverage at ANC was already very high prior to HDA deployment, and syphilis testing is supposed to be done at the same time HIV testing is conducted. However, there is a very large volume of HIV tests that need to be performed at ANC. Previously with limited human resources, perhaps syphilis testing was cut out, and this was ameliorated by the infusion of HDAs throughout the health system.

Both the number and percentage of exposed infants receiving DNA-PCR testing at 2 months of age were highly associated with HDA deployment. However, visual inspection of the data suggests that there was a time lag before these gains were fully appreciated. It is unclear whether this reflects a delayed effect of HDA deployment, or a confounder that we were unable to measure.

Our study has several important limitations. The lack of an appropriate control group because of the nature of implementation introduces a level of uncertainty into our results. We considered using nonintervention sites as controls, however, the nonrandom distribution of HDAs caused these sites to differ substantially from intervention sites to an intolerable extent. The use of single-group ITSA introduces the possibility that other unmeasured events may influence trends. Further, this approach is limited when data is over-dispersed and fewer time points are available. These limitations are highlighted by our attempted analysis of ART initiations. As this particular measure is reported on a quarterly basis, the smaller number of time points significantly limited analysis. Further, the high level of dispersion, and several significant positive outliers (likely reflecting the change to universal ART eligibility) precluded drawing any conclusions from this data.

However, we feel that our utilization of ITSA, while imperfect, represents the most pragmatic and precise approach to measuring the impact of a large, countrywide public health intervention; indeed, this approach is increasingly being used in similar settings and is gaining recognition as an appropriate methodology [15,16]. Future work should include evaluation and accounting of costs that would help determine sustainability and generalizability to other African settings, questions that are outside the scope of the current study.

Conclusion

Deployment of HDAs was highly associated with significant gains in HIV testing and other diagnostic testing, and is a promising approach to increase testing coverage in pursuit of the UNAIDS 90–90–90 targets.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the clients and health workers in participating facilities, as well as implementing partners and other stakeholders who have supported the deployment of HIV diagnostic assistants through the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). We thank the Malawi Ministry of Health for their partnership in this endeavor, and the Baylor College of Medicine Children's Foundation Malawi for their support.

Author contributions: R.J.F., conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation, visualization, writing of original draft, review and editing of final draft; K.R.S. and M.H.K., conceptualization, methodology, visualization, writing of original draft, review, and editing of final draft; R.N. and K.M., data curation and project administration; E.K., J.M., P.N.K., M.H., S.A., A.S., and J.T. review and editing of final draft.

Funding statement: This study was made possible by support from the USAID cooperative agreement number 674-A-00-10-00093-00. MHK was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01 TW009644. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 90–90–90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Ending AIDS: progress towards the 90–90–90 targets. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirschhorn LR, Oguda L, Fullem A, Dreesch N, Wilson P. Estimating health workforce needs for antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. Hum Resour Health 2006; 4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO). The World Health Report 2006 - working together for health. Geneva: WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanjana P, Torpey K, Schwarzwalder A, Simumba C, Kasonde P, Nyirenda L, et al. Task-shifting HIV counselling and testing services in Zambia: the role of lay counsellors. Hum Resour Health 2009; 7:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zachariah R, Ford N, Philips M, Lynch S, Massaquoi M, Janssens V, Harries AD. Task shifting in HIV/AIDS: opportunities, challenges and proposed actions for sub-Saharan Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2009; 103:549–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bemelmans M, Baert S, Goemaere E, Wilkinson L, Vandendyck M, van Cutsem G, et al. Community-supported models of care for people on HIV treatment in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2014; 19:968–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCollum ED, Preidis GA, Kabue MM, Singogo EB, Mwansambo C, Kazembe PN, Kline MW. Task shifting routine inpatient pediatric HIV testing improves program outcomes in urban Malawi: a retrospective observational study. PLoS One 2010; 5:e9626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MH, Ahmed S, Buck WC, Preidis GA, Hosseinipour MC, Bhalakia A, et al. The Tingathe programme: a pilot intervention using community health workers to create a continuum of care in the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) cascade of services in Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc 2012; 15 Suppl 2:17389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed S, Schwarz M, Flick RJ, Rees CA, Harawa M, Simon K, et al. Lost opportunities to identify and treat HIV-positive patients: results from a baseline assessment of provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling (PITC) in Malawi. Trop Med Int Health 2016; 21:479–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Populations Prospects 2017. New York: United Nations; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Government of Malawi Ministry of Health. Malawi Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment (MPHIA) 2015-2016. Summary sheet: preliminary findings. Lilongwe, Malawi: Government of Malawi; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linden A. Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single- and multiple-group comparisons. Stata Journal 2015; 15:480–500. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Government of Malawi Ministry of Health. Integrated HIV Program Report July-September 2017. Lilongwe, Malawi: Government of Malawi; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laliotis I, Ioannidis JPA, Stavropoulou C. Total and cause-specific mortality before and after the onset of the Greek economic crisis: an interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet Public Health 2016; 1:e56–e65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002; 27:299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]