Abstract

Although the neurotransmitter, 5–hydroxytryptamine (serotonin, 5–HT), has been implicated as a mediator of learning and memory, the specific role of 5–HT receptors in rodents requires further delineation. In this study, 5–HT2C receptor ligands of varying relative intrinsic efficacies were tested in a mouse learning and memory model called autoshaping-operant. On day 1, mice were placed in experimental chambers and presented with a tone on a variable interval schedule. The tone remained on for 6 s or until a nose-poke response occurred to produce a dipper with Ensure solution. Mice were then injected with saline, MK212 (full agonist), m-chlorophenylpiperazine (partial agonist), mianserin, and SB206 553 (inverse agonists), and methysergide and (+)-2-bromo lysergic acid diethylamide (+)-hydrogen tartrate (neutral antagonists). Each compound was injected after either 1 or 2–h acquisition sessions on day 1 to investigate the role of acquisition session length on consolidation. Day 1 injection of the 5–HT2C inverse agonist mianserin produced greater retrieval impairments of the autoshaped operant response on day 2 than any other agent tested. Furthermore, decreasing the length of the acquisition session to 1 h significantly increased the difficulty of the autoshaping task further modulating the consolidation effects produced by the 5–HT2C ligands tested.

Keywords: 5-HT2C receptors, autoshaping-operant, consolidation, learning, memory, mouse, serotonin

Introduction

There has been a long-standing interest in the role of the indoleamine 5–hydroxytryptamine (serotonin, 5–HT) in both associative and nonassociative learning in species as diverse as Aplysia to humans (for review see Meneses, 2003). More recently, the role of 5–HT in learning and memory processes has been investigated in rats using a paradigm called autoshaping (Meneses, 2001b, 2007; Meneses et al., 2004). Most autoshaping tasks combine both Pavlovian and instrumental conditioning and are sensitive to small increases or decreases in behavioral parameters, sign tracking, and goal tracking (Meneses, 2003). In most autoshaping procedures, a food-restricted animal is exposed to a visual or audible stimulus that predicts the presentation of food. The repeated pairing of stimulus with food (Pavlovian conditioning) soon elicits a behavioral response from the animal to obtain the food (instrumental conditioning) (Brown and Jenkins, 1968). For autoshaping to occur, an animal requires an intact hippocampus, septum, and cortex (Oscos-Alvarado et al., 1985; Meneses, 2003). Exposure to the autoshaping procedure produces changes in the expression of 5–HT receptors as labeled by [3H]-5–HT presynaptically in the raphe nucleus and postsynaptically in the hippocampus, in various regions of the cortex and in the amygdala areas (Meneses et al., 2004).

Pharmacologically, a number of different 5–HT subtypes seem to be involved in autoshaped learning. In the rat autoshaping procedure, a series of 5–HT2C/1B piperazine derivatives such as m-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP) were injected after the acquisition session on day 1 and impaired memory consolidation (Meneses and Hong, 1997); this impairment was reversed with 5–HT2B/2C antagonist SB200 646 (Meneses, 2002a) and 5–HT1B inverse agonist SB 224289 (Meneses, 2001a). The 5–HT2A receptor agonist (+/-)[−1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodo-phenyl)-aminopropane]-hydrochloride and the 5–HT2A/2C receptor antagonist ketanserin injected after the day 1 session both facilitated the consolidation of the auto-shaped response, whereas the selective 5–HT2A antago-nist MDL 100907 blocked the facilitatory effects of (+/-)-[1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-aminopropane]-hydro-chloride and ketanserin (Meneses, 2002a). Using the autoshaping procedure to study both short-term and long-term memory, the nonselective antagonist cyprohepta-dine, injected after the day 1 session, facilitated the consolidation of short-term memory but not long-term memory (Meneses et al., 2007). Furthermore, cyprohep-tadine impaired acquisition and retention in a passive avoidance task (Ma and Yu, 1993) suggesting the effects of cyproheptadine are task dependent or the injection interval before or after the task may be an important variable for the outcome of the study. 5–HT1B receptors are also involved in learning such that 5–HT1B inverse agonist SB 224289 facilitated consolidation in auto-shaping that was reversed by a 5–HT1B/1D antagonist GR 127935. In other studies, 5–HT1A KO mice show deficits in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory tests (Sarnyai et al., 2000) and 5–HT1B KO mice show enhanced platform acquisition and probe trial perfor-mance in the Morris water maze (Buhot et al., 2000).

Clearly there are many different 5–HT receptors involved in learning and memory processes; however the pharma-cology of these effects may be complex. Reports have described in-vitro conditions under which a proportion of 5–HT2C receptors can be shown to be constitutively active; that is, they are capable of initiating signal transduction and increasing basal effector activity in the absence of any agonist ligands (Barker et al., 1994; Westphal and Sanders-Bush, 1994; Berg et al., 1999; Hietala et al., 2001). There seems to be some evidence suggesting that constitutively active 5–HT2C or 5–HT2A receptors may regulate normal behavior and learning. For example, 5–HT agonists, such as d-lysergic acid diethylamide and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine, facilitate the acquisition of a classically conditioned response in rabbits (Harvey et al., 1982, 1983; Welsh et al., 1998b; Aloyo et al., 2009). Some 5–HT2 antagonists inhibit the acquisition of the conditioned response and impair the performance of the unconditioned response. These data suggest that antagonists, such as mianserin, pizotifen, ritanserin and MDL 11 939 may be inverse agonists (Ginn and Powell, 1986; Welsh et al., 1998a; Romano et al., 2000). Proposed 5–HT2C neutral antagonist (+)-2-bromo lysergic acid diethylamide hydrogen tar-trate (BOL) failed to alter the unconditioned effects or the rate of conditioned response acquisition in rabbits (Harvey et al., 1982, 1983; Romano et al., 2000), yet BOL blocked the decrease in response magnitude produced by the inverse agonist mianserin. In the 5–HT2C receptor system, there seems to be some evidence for a hypothesis that inverse agonists may impede learning while agonists could facilitate learning. These studies suggest that constitutive activation of the 5–HT2C or 5–HT2A receptor may have important implications for learning and motor performance in vivo (Harvey et al., 1999).

Therefore, in this study, we examined a series of agonists (MK212, mCPP), neutral antagonists (BOL, methyser-gide), and inverse agonists (mianserin, SB206 553) with affinity for 5–HT2C receptors for their effects on the consolidation process in an autoshaping-operant proce-dure for mice (Vanover and Barrett, 1998) modified to emphasize the instrumental response component of the task (Davenport, 1974). 5–HT agonists can produce hypophagia and under some conditions 5–HT inverse agonists can produce hyperphagia (Kennett and Curzon, 1988; Kennett et al., 1997; De Vry and Schreiber, 2000).

Therefore, to separate the effects of motivation to earn food from learning per se, all compounds were injected immediately after the acquisition session on day 1. Specifically, as observed in the rabbit classically condi-tioned response paradigm described above, we predicted that agonists would facilitate learning and inverse agonists would impair learning. To delineate further the effects of these agents on consolidation, we decreased the amount of time the mice were allowed to acquire the autoshaped operant response from 2 to 1 h, specifically to increase the difficulty of the task. We therefore predicted a greater magnitude of change on consolidation for the drugs after the 1-h acquisition session.

Methods

Animals

Male, Swiss–Webster mice (N = 145) weighing 20–35 g were obtained from ACE Animals, Inc., (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA). Mice arrived group-housed in plastic cages and were allowed to acclimate to the temperature and humidity-controlled facility for 7 days. Mice had free access to food and water during this time. All mice were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Temple University and the ‘Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research’ (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2003). The highest standards of animal welfare were maintained throughout these studies and the experiments were specifically designed to reduce the number of mice required.

Apparatus

Six mouse operant experimental chambers (21.6× 17.8×12.7 cm, Model ENV–307W, MED Associates, St. Albans, Vermont, USA) were used. Each chamber was housed within a sound-attenuating enclosure and connected to a computer-driven interface (Model SG–502, MED Associ-ates) that controlled the experimental conditions and collected the data. One wall of the chamber contained three receptacles: one large dipper hole in the center (ENV–313M) and two smaller nose-poke holes on the left and right (ENV–313W). The opposite wall featured a house light that illuminated the chamber during the session. Each chamber was also equipped with an audible tone device (Sonalert, 2900 Hz, Mallory Sonalert, In-dianapolis, Indiana, USA) that would emit a tone on a variable interval schedule. Nose-pokes into each hole were detected by a photocell head entry detector (ENV–303HD) and recorded. A dipper lever and dipper well was located behind the center dipper hole.

Autoshaping-operant procedure

The autoshaping-operant procedure was modified from the method described earlier for mice by Vanover and Barrett, (1998) and Davenport (1974) for rats. Briefly, after a 1-week acclimation period, mice (n = 5–12/group) were separated into individual cages, weighed and food restricted for 24 h before the experimental session. On day 1 of the autoshaping-operant procedure, mice were weighed and then placed inside the experimental chambers for a 15 min habituation period before the session started.

At the start of each session the house light illuminated the chamber and the mice were presented with a tone on a variable interval schedule (mean of 45 s, range 4–132 s), with the tone remaining on for 6 s or until a nose-poke response occurred. If a mouse made a dipper hole, nose-poke during the tone, a dipper with 50 : 50 Ensure : water solution was presented and the tone was turned off. Each 2-h session on day 1 lasted for 2 h or until 20 reinforced nose-pokes were recorded and each 1-h session lasted for 1 h or until 10 reinforced nose-pokes were recorded. All mice were kept inside the chambers until the res-pective 1-h or 2-h sessions expired, regardless of whether individual mice had finished their sessions. This was done to standardize the injection intervals as they were administered after the day 1 sessions. In this between-groups design, each group of mice was injected just once intraperitoneally with varying doses of MK212, mCPP, mianserin, SB206 553, BOL, methysergide or saline.

After the injections, mice were fed 1.5 g of food and returned to their cages until testing again 24 h later. On day 2, all mice were placed back into the chambers. After the 15 min habituation period, the autoshaping-operant session lasted for 2 h for all mice or until 20 nose-pokes were recorded, regardless of the length of their initial session.

Drugs

MK212 hydrochloride, mCPP hydrochloride, and methy-sergide maleate (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, Missouri, USA), mianserin hydrochloride, SB 206 553 hydrochloride (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), and BOL (National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). All drugs were dissolved with either saline or sterile water for injection and injected intraperitoneally. SB 206 553 was dissolved in a few drops of Tween 80 before adding sterile water and then the entire solution was sonicated.

Data and statistical analysis

Each nose-poke into the center nose-poke hole in concert with the audible tone elicited the presentation of the dipper of Ensure and was recorded as a reinforced response (up to a maximum of 20 in each 2–h session or 10 in each 1-h session). The main measure of acquisition and retention of this behavior was the mean adjusted latency, in seconds, of the latency to respond for the tenth reinforcer minus the latency to respond for the first reinforcer (L10–L1). With this adjustment, the unequal opportunity for each mouse to achieve the first reinforcer because of the variable schedule of the tone stimulus is corrected. In essence, the mean adjusted latency represents the elapsed time, in seconds, from the first reinforcer earned to the tenth (Vanover and Barrett, 1998). To calculate the rate of dipper nose-poke hole responding per second, the total number of dipper nose-pokes made during the session – regardless of the presence or absence of the tone – was recorded and divided by the total session time in seconds for each mouse. This dipper rate measure serves as a guide to whether differences in mean adjusted latency were dependent or independent of overall rate of responding. The number of nose-pokes into the left and right nose poke holes was also recorded as a measure of general activity and represented as a rate of responding in seconds. All mice were included in acquisition measures from the day 1 sessions. However, any mouse that failed to make at least 10 reinforced responses on day 1 of 2-h testing or at least five reinforced responses on day 1 of 1-h testing was excluded from the latency measures on day 2. The rationale for this exclusion is that it was not appropriate to evaluate day 2 retention of a response that was insufficiently reinforced, or not reinforced at all, on day 1 (Vanover and Barrett, 1998). If the mouse did not obtain the tenth reinforcer on day 1, a value of 7200 s was assigned to L10 and the latency to the first reinforcer was subtracted from that value for the individual mean adjusted latency. The data from this mouse would not be included in the day 2 mean adjusted latency data. If a mouse did not respond at all on day 1, a value of 7200 s was assigned as the mean adjusted latency and the data from this mouse would not be included in the day 2 mean adjusted latency data. In the entire study, 12 of 145 total mice were excluded from the day 2 mean adjusted latency data analysis. Two-way analysis of variance was used to evaluate the effect of drugs and session length on performance measures. Bonferroni post-hoc tests were used if significance was indicated. Paired t-tests were used to compare day 1 versus day 2 measures within groups.

Results

Saline control experiments

On day 1, mice acquired the nose-poke response into the dipper well in the presence of the tone with a mean-adjusted latency of 1500 ± 290 s, after a 1-h acquisition session in the experimental chambers, and responded into the dipper well with an average response rate of 0.18 ± 0.026 response/s (Table 1) for the entire session. The rate of responding into the nonreinforced left and right nose-poke holes was 0.012 ± 0.0031 response/s during the day 1 session. Saline injections were adminis-tered to all mice immediately following this 1-h acquisi-tion session and the mice were placed into their home cages. On day 2, the mice were placed back into the experimental chambers without additional injections and the experimental conditions proceeded exactly as on day 1 except that the day 2 session lasted for 2 h. Mice responded into the dipper well in the presence of the tone with a mean-adjusted latency of 690 ± 230 s, which although faster than the day 1 mean-adjusted latency, was not significantly different (Table 1). However, the dipper response rate increased significantly to 0.51 ± 0.078 response/s on day 2 from day 1 (P≤ 0.002), and the nonreinforced response rate decreased significantly to0.0029 ± 0.0012 on day 2 from day 1 (P ≤ 0.02).

Table 1.

Effects of acquisition session duration on days 1 and 2 performances (mean ± SEM) in the autoshaping-operant procedure

| 1 h acquisition | 2 h acquisition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 2 | P value | Day 1 | Day 2 | P value | |

| Mean-adjusted latency (s) | 1500 ± 290 | 690 ± 230 | NS | 2600 ± 620 | 720 ± 210 | 0.03 |

| Reinforced responding (response/s) | 0.18 ± 0.026 | 0.51 ± 0.078 | 0.002 | 0.055 ± 0.021 | 0.44 ± 0.065 | 0.0001 |

| Nonreinforced responding (response/s) | 0.012 ± 0.0031 | 0.0029 ± 0.0012 | 0.02 | 0.0057 ± 0.00065 | 0.0013 ± 0.00019 | 0.0001 |

NS, not significant; SEM, standard error of mean.

A different group of mice exposed to a 2-h acquisition session on day 1 acquired the nose-poke response into the dipper well in the presence of the tone with a mean-adjusted latency of 2600 ± 620 s and a response rate into the dipper well of 0.055 ± 0.021 response/s (Table 1). The rate of responding into the nonreinforced left and right nose-poke holes was 0.0057 ± 0.00057 response/s. These mice were injected with saline immediately after their day 1 session and then placed back into their home cages. On day 2, during the 2-h session, the mice responded into the dipper well in the presence of the tone with a mean-adjusted latency of 720 ± 210 s, which was significantly faster than their day 1 latency (P r 0.05). The overall dipper response rate regardless of the presence of the tone significantly increased to0.44 ± 0.065 response/s (P < 0.001) and the nonrein-forced nose-poke rate significantly decreased to 0.0013 ± 0.00019 (P < 0.001). In summary, the mice exposed to a 2-h acquisition session showed a significantly decreased mean-adjusted latency to respond in the dipper well nose-poke in the presence of the audible tone while the mice allowed only a 1-h acquisition session responded with similar latencies on days 1 and 2. Both groups of mice showed significant increases in dipper well nose-poke responding on day 2 compared with day 1. Both groups also showed a significant decrease in nonre-inforced left and right nose-poke responding on day 2 versus day 1 although the magnitude of these day 2 differences was greater in the mice exposed to a 2-h acquisition session (Table 1).

5–HT2C receptor ligands

Groups of mice were injected with 5–HT compounds after the acquisition session on day 1. The mean ± SEM responding on day 1 across the groups in the 1-h acquisition session was as follows: mean-adjusted latency (1540 ± 132 s), dipper response rate (0.15 ±0.019 response/s), and nonreinforced response rates(0.0079 ± 0.0015 response/s). The mean ± SEM respond-ing on day 1 across the groups in the 2-h acquisition session was as follows: mean-adjusted latency (1779 ± 213 s), dipper response rate (0.21 ± 0.018 response/s), and nonreinforced response rates (0.0091 ± 0.00079 response/s). Analysis of variance revealed that the length of the acquisition session contributed to the differences seen in the day 2 mean-adjusted latency measures (F(1,115) = 4.83, P≤ 0.05) independently of any particu-lar drug injected after the day 1 acquisition session. The acquisition session length, however, did not alter the magnitude of effect between the overall reinforced dipper well nose-poke responding or the nonreinforced left and right nose-poke responding on day 2. Mice exposed to either a 1-h or 2-h acquisition session and sub-sequently treated with either MK212, mCPP, 10 mg/kg mianserin, SB206 553 (3.2 and 10 mg/kg), BOL or methysergide did not differ significantly from saline in mean-adjusted latency of reinforced responding on day 2 (Fig. 1, left panel). Although the day 2 mean-adjusted latencies of the mCPP, 10 mg/kg mianserin, SB206 553, BOL and methysergide groups were higher after the 1-h acquisition session than the saline controls, none achieved statistical significance. However, the mice treated with 32 mg/kg mianserin after the day 1 acquisi-tion session each responded with significantly longer latencies on day 2 compared with saline controls. The mice exposed to the 1-h acquisition session had the greatest magnitude increase (P < 0.001), with the mice allowed a 2-h acquisition session slightly faster (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1, left panel). In addition to the differences relative to saline controls, injection with 32 mg/kg mianserin immediately after the 2-h day 1 session produced longer mean-adjusted latencies than MK212 (P < 0.05), mCPP (P < 0.05), 10 mg/kg mianserin (P < 0.05), 10 mg/kg SB206 553 (P < 0.05), BOL (P < 0.05) and methyser-gide (P < 0.05). Mice injected with 32 mg/kg mianserin immediately after the 1-h acquisition session produced longer mean-adjusted latencies than those mice injected with MK212 (P < 0.01), 3.2 and 10 mg/kg SB206 553 (P < 0.01), BOL (P < 0.05) and methysergide (P < 0.01).

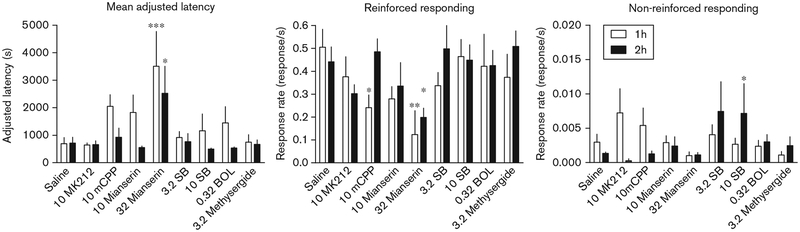

Fig. 1.

Effects of saline and 5–HT2C ligands on the consolidation of autoshaped-operant reinforced and nonreinforced responding in mice after 1-h (white bars) and 2-h (black bars) acquisitions sessions on day 1. Vertical axis: left panel, mean-adjusted latency defined as the latency to the tenth minus the latency to the first reinforced response; middle panel, rate of overall dipper hole nose-poke responses per second; right panel, rate of left and right nose-poke responding as a measure of nonreinforced activity. Horizonrtal axis: saline, drugs and doses in mg/kg, administered intraperitoneally. 1-h acquisition session: 32 mg/kg mianserin increased day 2 mean latency relative to saline controls (P < 0.001), MK212 (P < 0.01), SB206 553 (P < 0.01), BOL (P < 0.05) and methysergide (P < 0.01) (left panel); reduced rates of reinforced responding relative to saline (P < 0.01) and 10 mg/kg SB206 553 (P < 0.01) (middle panel); MK212 increased nonreinforced response rates relative to 32 mg/kg mianserin (P < 0.05) and methysergide (P < 0.05) (right panel). 2-h acquisition session: 32 mg/kg mianserin increased day 2 mean latency relative to saline controls (P < 0.05) and all other agents tested (P < 0.05) (left panel); reduced rates of reinforced responding compared with saline controls (P < 0.05), m-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP) (P < 0.01), 3.2 mg/kg SB206 553 (P < 0.05) and methysergide (P < 0.01) (middle panel); 10 mg/kg SB206 553 significantly altered rates of nonreinforced responding relative to saline controls, (P < 0.05), MK212 (P < 0.01), mCPP (P < 0.05) and 32 mg/kg mianserin (P < 0.05) (right bars). Number of mice tested during the 1- and 2-h acquisition session, respectively: saline (n = 11, 10), MK212 (n = 5, 5), mCPP (n = 11, 12), (10 mg/kg n = 6, 6; 32 mg/kg n = 6, 9), SB206 553 (3.2 mg/kg n = 6, 4; 10 mg/kg n = 11, 5), BOL (n = 5, 7), and methysergide (n = 5, 9). Twelve mice failed to earn five (1 h) or 10 (2 h) reinforcers during the day 1aquisition session. Vertical bars represent SEM *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Mice exposed to either a 1-h or 2-h acquisition session and subsequently treated with either MK212, 10 mg/kg mianserin, SB206 553, BOL or methysergide did not differ significantly from saline controls in overall rate of responding in the dipper well on day 2 (Fig. 1, middle panel). Mice injected with mCPP after a 1-h acquisition session responded in the dipper well at a significantly slower rate than saline controls (P < 0.05). However, this difference after the 1-h acquisition session was not present relative to any of the other drugs tested and mCPP did not affect overall rates of dipper well responding after the 2-h session. Mice injected with 32 mg/kg mianserin after either a 1-h or 2-h acquisition session showed lower overall rates of responding in the dipper well on day 2 compared with saline controls (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively). The day 2 response rate of the mice treated with 32 mg/kg mianserin after the 1-h session was also significantly lower than that of the mice treated with 10 mg/kg SB206 553 (P < 0.01). The mice treated with 32 mg/kg mianserin after a 2-h acquisition session also responded significantly slower on day 2 than those treated with mCPP (P < 0.01), 3.2 mg/kg SB206 553 (P < 0.05) or methysergide (P < 0.01) after a 2-h acquisition session.

Analysis of day 2 nonreinforced left and right nose-poke response rates revealed that mice treated with 10 mg/kg SB206 553 after a 2-h acquisition session responded at significantly higher rates than saline controls (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1, right panel). This increased response rate was also evident relative to mice treated with MK212 (P < 0.05), mCPP (P < 0.05), and 32 mg/kg mianserin (P < 0.05) after a 2-h acquisition session. Of those animals exposed to a 1-h acquisition session, none were different from saline controls in their rates of nonreinforced left and right nose-poke responding. However, mice treated with MK212 after a 1-h acquisition session responded at a significantly higher rate than mice treated with 32 mg/kg mianserin (P < 0.05) and methysergide (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Although previous studies have examined the role of 5–HT and 5–HT receptors in learning of a Pavlovian/instrumental autoshaping task in rats (Meneses, 2003), the present experiment is the first to use a variation of the autoshaping-operant procedure to study the effects of 5–HT2C ligands in mice. Earlier, in our laboratory, we showed that mice can readily acquire an autoshaped-operant response on day 1 and retrieve the response on day 2 after being exposed to a 2-h acquisition session (Foley et al., 2008) similar to data collected earlier (Vanover and Barrett, 1998). Furthermore, this response was disrupted by scopolamine but not methylscopol-amine, showing that drugs must cross the blood–brain barrier to disrupt this autoshaped responding (Foley et al., 2008). In this study, we showed that by decreasing the day 1 acquisition session from 2–1 h, the mice took significantly longer on day 2 to retrieve the autoshaped-operant response independent of the drug injection after the day 1 session. In the 1-h acquisition session, the mice had the opportunity to earn 10 reinforcers compared with the 2-h acquisition session in which the mice had the opportunity to earn 20 reinforcers. Therefore, the autoshaping-operant model is similar to a number of Pavlovian and instrumental procedures that show the number of unconditioned stimuli or reinforcers can impact the final asymptote or rate of learning despite the complexities of these relationships (Nachman and Ashe, 1973; Polenchar et al., 1984; Skjoldager et al., 1993).

In the autoshaping-operant model, we tested ligands reported earlier in vitro to range in intrinsic efficacy at 5–HT2C receptors: MK212, an agonist (Santini et al., 2001); mCPP, a partial agonist (Santini et al., 2001; Schlag et al., 2004); methysergide and BOL, neutral antagonists (Westphal and Sanders-Bush, 1994; Herrick-Davis et al., 1997); and SB206 553 and mianserin, inverse agonists (Barker et al., 1994; Devlin et al., 2004; Schlag et al., 2004). As observed in the rabbit eyeblink model (for review see Aloyo et al., 2009), we observed the greatest impairment of consolidation after the injection of 5–HT2C inverse agonist mianserin. Specifically, an injection of 32 mg/kg mianserin administered after the day 1 acquisition significantly increased the mean-adjusted latencies to earn reinforcers on day 2 and simultaneously decreased rates of reinforced responding independent of the length of acquisition session relative to the saline control values as well as most of the other 5–HT2C ligands. Similarly, the 5–HT2A inverse agonists clozapine and AC-90179 impaired autoshaped responding using similar procedure in mice (Vanover et al., 2004). Potentially, mianserin impaired consolidation by suppressing basal activity at 5–HT2C receptors as would be expected by an inverse agonist. In this study, however, the other 5–HT2C inverse agonist studied, SB206 553, failed to alter latency values or rates of reinforced responding. SB206 553 did increase the rate of responding in the incorrect nose-poke holes on day 2 which suggests a disruption of discriminative control. SB200 646, a 5–HT2B/2C antagonist (Kennett et al., 1994) similar to SB206 553, failed to modify autoshaped responding in rats although it did block the memory impairments produced by mCPP (Meneses, 2002b). The observation that mianserin produced con-solidation deficits but SB206 553 did not, suggests that mianserin may be a stronger inverse agonist than SB206 553. However, in vitro, mianserin and SB206 553 suppressed basal inositol phosphate formation, increased cell surface expression of 5–HT2C receptors, and were reversed by neutral antagonist SB242 084 under similar conditions suggesting mianserin and SB206 553 are inverse agonists with at least similar magnitudes of intrinsic efficacy (Chanrion et al., 2008). Therefore, the difference observed between mianserin and SB206 553 observed in this study may be related to additional activities for mianserin such as blockade of a2-adrenergic or histamine receptors or suppression of norepinephrine reuptake (Millan, 2006). Further study is required to understand the complex role that mianserin may play in learning and memory.

In the rabbit eyeblink procedure, agonists with affinity for 5–HT2A/2C receptors such as d-lysergic acid diethyl-amide and (−)-2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine fa-cilitated conditioned responding (Aloyo et al., 2009). However, in the mouse autoshaped-operant task, agonists MK212 and mCPP did not facilitate acquisition despite the fact that 10 mg/kg MK212 and mCPP are behaviorally relevant doses in a number of other learning tasks (Meneses, 2002b; Walker et al., 2005). In the 1-h acquisition session, injections of mCPP actually impaired consolidation as measured by reinforced response rates similar to autoshaping results obtained earlier in rats with mCPP (Meneses, 2002b). However, mCPP impaired consolidation in mice only after the 1-h acquisition session when the task was more difficult. The 5–HT2C full agonist MK212 failed to facilitate or impair con-solidation in the autoshaping-operant procedure by any measure. Similarly, pretreatment of MK212, BOL, or mianserin failed to alter acquisition of a LiCl-induced conditioned taste aversion in mice perhaps because of the rapid pairings of this classically conditioned response (Meneses, 2002b; Walker et al., 2005). The autoshaping-operant procedure like the LiCl-induced conditioned taste aversion procedure may be limited by floor effects to detect improvements in learning despite the increased difficulty of a shorter acquisition session. Alternatively, the 5–HT2C agonists may not facilitate learning in the same manner as observed earlier for the 5–HT2A agonists.

Altogether, these data suggest that 5–HT2C receptors may in fact play a role in memory consolidation. The neutral antagonists methysergide and BOL failed to alter learning in mice on any measure in this study. Similarly, BOL did not alter learning in the rabbit eyeblink model but BOL did block the retardation of learning produced by mianserin (Romano et al., 2000) confirming the notion that BOL is a neutral antagonist in our autoshaping-operant model. Therefore, similar to other studies, the inverse agonist mianserin (but not SB206 553) delayed learning but the neutral antagonists BOL and methyser-gide failed to significantly alter learning in this autoshap-ing procedure. Finally, this study shows that the difficulty of the learning task can further modulate the consolida-tion effects produced by the 5–HT2C ligands.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by National Institute of Drug Abuse Grant DA14673.

References

- Aloyo VJ, Berg KA, Spampinato U, Clarke WP, Harvey JA (2009). Current status of inverse agonism at serotonin2A (5–HT2A) and 5–HT2C receptors. Pharmacol Ther 121:160–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker EL, Westphal RS, Schmidt D, Sanders-Bush E (1994). Constitutively active 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptors reveal novel inverse agonist activity of receptor ligands. J Biol Chem 269:11687–11690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KA, Stout BD, Cropper JD, Maayani S, Clarke WP (1999). Novel actions of inverse agonists on 5–HT2C receptor systems. Mol Pharmacol 55:863–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PL, Jenkins HM (1968). Auto-shaping of the pigeon’s key-peck. J ExpAnal Behav 11:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhot MC, Martin S, Segu L (2000). Role of serotonin in memory impairment. Ann Med 32:210–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanrion B, Mannoury la Cour C, Gavarini S, Seimandi M, Vincent L, Pujol JF, et al. (2008). Inverse agonist and neutral antagonist actions of antidepres-sants at recombinant and native 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptors: differ-ential modulation of cell surface expression and signal transduction. Mol Pharmacol 73:748–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport JW (1974). Combined autoshaping-operant (AO) training: CS-UCS interval in rats. Bull Psychomonic Soc 3:383–385. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin MG, Smith NJ, Ryan OM, Guida E, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A (2004). Regulation of serotonin 5–HT2C receptors by chronic ligand exposure. Eur J Pharmacol 498:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vry J, Schreiber R (2000). Effects of selected serotonin 5–HT(1) and 5–HT(2) receptor agonists on feeding behavior: possible mechanisms of action. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 24:341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley JJ, Raffa RB, Walker EA (2008). Effects of chemotherapeutic agents 5-fluorouracil and methotrexate alone and combined in a mouse model of learning and memory. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 199:527–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginn SR, Powell DA (1986). Pizotifen (BC-105) attenuates orienting and Pavlovian heart rate conditioning in rabbits. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 24:677–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey JA, Gormezano I, Cool VA (1982). Effects of d-lysergic acid diethylamide, d-2-bromolysergic acid diethylamide, dl-2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine and d-amphetamine on classical conditioning of the rabbit nictitating membrane response. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 221:289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey JA, Gormezano I, Cool-Hauser VA (1983). Effects of scopolamine and methylscopolamine on classical conditioning of the rabbit nictitating membrane response. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 225:42–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey JA, Welsh SE, Hood H, Romano AG (1999). Effect of 5–HT2 receptor antagonists on a cranial nerve reflex in the rabbit: evidence for inverse agonism. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 141:162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick-Davis K, Egan C, Teitler M (1997). Activating mutations of the serotonin 5–HT2C receptor. J Neurochem 69:1138–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hietala J, Kuonnamaki M, Palvimaki EP, Laakso A, Majasuo H, Syvalahti E (2001). Sertindole is a serotonin 5–HT2c inverse agonist and decreases agonist but not antagonist binding to 5–HT2c receptors after chronic treatment. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 157:180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennett GA, Curzon G (1988). Evidence that hypophagia induced by mCPP and TFMPP requires 5–HT1C and 5–HT1B receptors; hypophagia induced by RU 24969 only requires 5–HT1B receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 96:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennett GA, Wood MD, Glen A, Grewal S, Forbes I, Gadre A, Blackburn TP (1994). In vivo properties of SB 200646A, a 5–HT2C/2B receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol 111:797–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennett GA, Ainsworth K, Trail B, Blackburn TP (1997). BW 723C86, a 5–HT2B receptor agonist, causes hyperphagia and reduced grooming in rats. Neuropharmacology 36:233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma TC, Yu QH (1993). Effect of 20(S)-ginsenoside-Rg2 and cyproheptadine on two-way active avoidance learning and memory in rats. Arzneimittelforschung 43:1049–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses A, Hong E (1997). Role of 5–HT1B, 5–HT2A and 5–HT2C receptors in learning. Behav Brain Res 87:105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses A (2001a). Could the 5–HT1B receptor inverse agonism affect learning consolidation? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 25:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses A (2001b). Role of 5–HT6 receptors in memory formation. Drug News Perspect 14:396–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses A (2002a). Involvement of 5–HT(2A/2B/2C) receptors on memory formation: simple agonism, antagonism, or inverse agonism? Cell Mol Neurobiol 22:675–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses A (2002b). Tianeptine: 5–HT uptake sites and 5–HT(1–7) receptors modulate memory formation in an autoshaping Pavlovian/instrumental task. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 26:309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses A (2003). A pharmacological analysis of an associative learning task: 5–HT(1) to 5–HT(7) receptor subtypes function on a pavlovian/instrumental autoshaped memory. Learn Mem 10:363–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses A, Manuel-Apolinar L, Rocha L, Castillo E, Castillo C (2004). Expression of the 5–HT receptors in rat brain during memory consolidation. Behav Brain Res 152:425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses A (2007). Do serotonin(1–7) receptors modulate short and long-term memory? Neurobiol Learn Mem 87:561–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses A, Manuel-Apolinar L, Castillo C, Castillo E (2007). Memory consolidation and amnesia modify 5–HT(6) receptors expression in rat brain: an autoradiographic study. Behav Brain Res 178:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ (2006). Multi-target strategies for the improved treatment of depressive states: Conceptual foundations and neuronal substrates, drug discovery and therapeutic application. Pharmacol Ther 110:135–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachman M, Ashe JH (1973). Learned taste aversion in rats as a function of administration of LiCl. Physiol Behav 10:73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oscos-Alvarado A, Camacho JL, Meneses A, Aleman V (1985). The post-trial effect of amphetamine in memory and in cerebral protein amino acid incorporation in the rat In: McGaugh JL, editor. Contemporary psychology: biological processes and theoretical issues. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science; pp. 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Polenchar BE, Romano AG, Steinmetz JE, Patterson MM (1984). Effects of US parameters on classical conditioning of cat hindlimb flexion. Animal Learning and Behavior 12:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Romano AG, Hood H, Harvey JA (2000). Dissociable effects of the 5–HT(2) antagonist mianserin on associative learning and performance in the rabbit. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 67:103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini E, Muller RU, Quirk GJ (2001). Consolidation of extinction learning involves transfer from NMDA-independent to NMDA-dependent memory. J Neurosci 21:9009–9017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnyai Z, Sibille EL, Pavlides C, Fenster RJ, McEwen BS, Toth M (2000). Impaired hippocampal-dependent learning and functional abnormalities in the hippocampus in mice lacking serotonin(1A) receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:14731–14736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlag BD, Lou Z, Fennell M, Dunlop J (2004). Ligand dependency of 5-hydroxytryptamine 2C receptor internalization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310:865–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjoldager P, Pierre PJ, Mittleman G (1993). Reinforcer magnitude and progressive ratio responding in the rat: effects of increased effort, prefeeding, and extinction. Learn Motiv 24:303–343. [Google Scholar]

- Vanover KE, Barrett JE (1998). An automated learning and memory model in mice: pharmacological and behavioral evaluation of an autoshaped response. Behav Pharmacol 9:273–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanover KE, Harvey SC, Son T, Bradley SR, Kold H, Makhay M, et al. (2004). Pharmacological characterization of AC-90179 (2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-(4-methyl-benzyl)-N-(1-methyl-piperidin-4-yl)-aceta mide hydrochloride): a selective serotonin 2A receptor inverse agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310:943–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Kohut SJ, Hass RW, Brown EK Jr, Prabandham A, Lefever T (2005). Selective and nonselective serotonin antagonists block the aversive stimulus properties of MK212 and m-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP) in mice. Neuropharmacology 49:1210–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh SE, Kachelries WJ, Romano AG, Simansky KJ, Harvey JA (1998a). Effects of LSD, ritanserin, 8-OH-DPAT, and lisuride on classical conditioning in the rabbit. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 59:469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh SE, Romano AG, Harvey JA (1998b). Effects of serotonin 5–HT(2A/2C) antagonists on associative learning in the rabbit. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 137:157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal RS, Sanders-Bush E (1994). Reciprocal binding properties of 5-hydroxytryptamine type 2C receptor agonists and inverse agonists. Mol Pharmacol 46:937–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]