Abstract

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are the second most common congenital malformations in humans affecting the development of the central nervous system. Although NTD pathogenesis has not yet been fully elucidated, many risk factors, both genetic and environmental, have been extensively reported. Classically divided in two main sub-groups (open and closed defects) NTDs present extremely variable prognosis mainly depending on the site of the lesion. Herein we review the literature on the histological and pathological features, epidemiology, prenatal diagnosis and prognosis, based on the type of defect, with the aim of providing important information based on NTDs classification for clinicians and scientists.

Keywords: Neural Tube Defects, Spina bifida, Anencephaly

Development of Neural Tube Defects

Neural Tube Defects (NTDs) arise secondary to abnormal embryonic development of the future central nervous system. The two most common types of NTDs are spina bifida and anencephaly, affecting different levels of the brain and spine, normally reflecting alterations of the embryonic processes that form these structures. Birth defects such as NTDs are relatively uncommon, with a global prevalence among live births in the US of 1 in 1200, and a worldwide prevalence ranging from 1 in 1,000 (in Europe and the Middle East) to 3–5 in 1,000 (in northern China as of 2014 with folate supplementation campaigns, bringing the prevalence down from 10 per 1,000 for years 2000–2004) (Blencowe, Kancherla, Moorthie, Darlison, & Modell, 2018; Khoshnood et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016; Salih, Murshid, & Seidahmed, 2014). Despite their public health significance, surprisingly little is known about the etiology of NTDs in humans.

The central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) is formed in vertebrates during a process known as neurulation. This process occurs in human embryos between days 17 and 28 post-fertilisation. In the previous developmental phase (gastrulation), the ectoderm is formed, which will thicken in response to specific molecular signals released by the underlying notochord, giving rise to the neural plate. This plate of ectodermal cells will form the neural tube by elevating, juxtaposing and fusing along the midline (primary neurulation) of the body axis. In the caudal region, neurulation (secondary) involves cellular condensation and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition to close the neural tube (Saitsu, Yamada, Uwabe, Ishibashi, & Shiota, 2004). In mammals, primary neurulation is a multi-site process and recent evidence suggest that in humans two closure sites are recognisable (one at the prospective cervical region and one over the mesencephalon-rombencephalic boundary) (Copp, Stanier, & Greene, 2013; Nakatsu, Uwabe, & Shiota, 2000). Mammalian neurulation is tightly regulated and energetically highly demanding, involving the formation of an anterior (ANP) and posterior neuropore (PNP). These neuropores or openings will progressively reduce in size until final fusion completes the process of neural tube closure (NTC) (Figure 1).

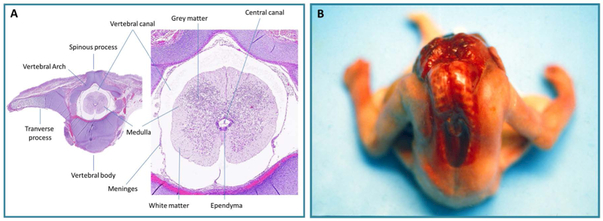

Figure 1.

A: Transverse section of normal fetal vertebra with typical spinal cord section. B. Craniorachischisis. Note the absence of the cranial vault, the defect extends to vertebral arch into upper dorsal area, resulting in anencephaly and spina bifida

Different types of NTDs reflect the site of the interrupted neurulation. For example, craniorachischisis, which affects the brain and spinal cord, results from a failure of the initial closure site resulting in an open brain and spine, while anencephaly arises from abnormalities in the cranial neurulation process, and spina bifida results from incomplete caudal neurulation

Epidemiology and risk factors

Chromosomal anomalies such as trisomy 13, trisomy 18 and triploidy represent less than 10% of all NTDs cases (Kennedy, Chitayat, Winsor, Silver, & Toi, 1998), while non-syndromic isolated cases represent the vast majority of NTDs, exhibiting a sporadic pattern of occurrence (Copp et al., 2015). The prevalence of the different types of NTDs is not always reported in publications, given the difficulties in data ascertainment following legal pregnancy terminations and spontaneous abortions. The prevalence of NTDs in miscarriage or stillbirths appears higher than in term pregnancies (Padmanabhan, 2006), and the estimated prevalence reflects temporal, regional and ethnic variations (Blom, Shaw, den Heijer, & Finnell, 2006; Wallingford1, Niswander, Shaw, & Finnell, 2013). For example, the NTD prevalence in Mexico (~3.2 in 2000 births) is higher than in the United States, (CDC 2000), while the prevalence in some regions of China are 20 times higher than in the United States (Li et al., 2006). Interestingly, the different prevalence of NTD cases between ethnic groups persists after migration of the racial groups to other geographical areas, indicating a genetic contribution to NTD susceptibility (Leck, 1974; Shaw, Velie, & Wasserman, 1997).

In terms of genetic predisposition, women who have had an affected fetus have an empirical recurrence risk of 3% in any subsequent pregnancy, yet this risk only rises to approximately 10% after conceiving a second NTD embryo (Copp et al., 2015). This underscores the fact that while genetic factors are important, one cannot ignore the impact of the environment on the development of the NTD phenotype. In twins, the NTDs’ concordance rates among monozygotics is reported to be 7.7%, significantly higher than the rate for dizygotic twins (4.4%).

Finally, a gender predisposition has been reported for some types of NTDs: a female excess has been reported for neural tube defects, possibly due to a sex-related genetic or epigenetic effect. Despite the decades long attempts to elucidate genetic factors causative of NTDs in humans, no conclusive evidence has been identified. In studies based on vertebrate animal models, a great number of genes have been implicated in the causation of NTDs. In the mouse, for example, more than 400 genes have been found responsible for failed NTC (Harris & Juriloff, 2010; Wallingford1 et al., 2013). Some of these genes are highly evolutionarily conserved, and their role in neurulation has been shown in multiple vertebrate animal models (Wallingford, 2005). In humans cohort studies of NTDs, genetic variants have been associated with increased risk (N. D. E. Greene, Stanier, & Copp, 2009). However, some variants are present in different NTDs subtypes and some have also been reported in healthy patients, highlighting the difficulties of finding a clear genotype/phenotype association in humans.

Many factors, both genetic and non-genetic, are involved in the abnormal closure of the neural tube, suggesting that multi-factorial causes lead to the development of NTDs (Copp et al., 2015). It is likely that each factor individually is insufficient to disrupt normal NTC; however, together these genetic and non-genetic factors produce synergistic effects leading to failed NTC and the abnormal embryonic phenotype. This working hypothesis represents the so-called “multifactorial threshold model” (Harris & Juriloff, 2007).

Non-genetic risk factors include exposure to a broad range of environmental exposures such as air pollution (Brender, Felkner, Suarez, Canfield, & Henry, 2010; Carmichael et al., 2014; Cordier et al., 1997; Hutchins et al., 1996; Zhiwen Li et al., 2011; Lupo et al., 2011; Padula et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2011; Righi et al., 2012) and maternally toxic factors including disease, nutrition, exposure to occupational chemicals or physical agents and abuse of substance (Table 1).

Table 1:

Modifiable risk factors for NTDs

| Risk Factor | Action | Risk | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal diabetes | Teratogenic effect due to embryonic exposure to high glucose concentrations leading to increased cell death in the neuroepithelium | 2-10-fold increase | (Ray, 2001; Shaw et al., 2003; Yazdy, Mitchell, Liu, & Werler, 2011) |

| Maternal obesity | Teratogenic effect due to embryonic exposure to hyperinsulinemia, metabolic syndrome, and oxidative stress related to adiposity | 1.5-3.5-fold increase. The risk increases with increased maternal body mass index |

(Anderson et al., 2005; Carmichael, Rasmussen, Lammer, Ma, & Shaw, 2010; Dietl, 2005; Hendricks, Nuno, Suarez, & Larsen, 2001; Shaw, Velie, & Schaffer, 1996; Werler, Louik, Shapiro, & Mitchell, 1996) |

| Maternal Hyperthermia (sauna, hot water tube, fever) | Teratogenic effect due to embryonic exposure to heat stress | 2-fold increase | (Moretti, Bar-Oz, Fried, & Koren, 2005; Suarez, Felkner, & Hendricks, 2004; Waller et al., 2017) |

| Drugs (particularly valproate) | Teratogenic effect due to embryonic exposure to valproate action as inhibitor of histone deacetylases, disturbing the balance of protein acetylation and deacetylation, leading to neurulation failure | 10-fold increase | (Kanai, Sawa, Chen, Leeds, & Chuang, 2004; Lammer, Sever, & Oakley, 1987; Meador et al., 2006; Pai et al., 2015; Yildirim et al., 2003) |

| Inadequate maternal nutritional status | Teratogenic effect due to embryonic exposure to low folate intake, low methionine intake, low zinc intake, low serum vitamin B12 level, low vitamin C level, caffeine abuse, alcohol use, smoking, all conditions disturbing the folate-related metabolism | Undetermined | (Grewal, Carmichael, Ma, Lammer, & Shaw, 2008; Kirke et al., 1993; Ray & Blom, 2003; Schmidt et al., 2009; Suarez, Hendricks, Felkner, & Gunter, 2003; Velie et al., 1999) |

Physical characteristics of neural tube defects

NTDs have been classically divided into open defects such as craniorachischisis, exencephaly-anencephaly and myelomeningoceles, and closed defects, including encephalocele, meningocele and spina bifida occulta (Copp & Greene, 2013; McComb, 2015). In general, open defects are characterized by the external protrusion and/or exposure of neural tissue. Closed defects have an epithelial covering (either full or partial skin thickness) without exposure of neural tissue (McComb, 2015). Biochemically, during pregnancy open defects are detectable due to the high levels of amniotic fluid α-fetoprotein and amniotic fluid acetylcholinesterase, whereas closed defects do not deviate from normal levels of amniotic fluid α-fetoprotein or acetylcholinesterase. Clinically, open defects trend towards having worse functional neurological outcomes in children, compared to closed defects.

Open neural tube defects

Craniorachischisis

Definition.

Craniorachischisis is a defect of NTC that involves both the cranial and spinal portions of the neural tube (Golden & Harding, 2004). It is the most severe expression of an open NTD.

Epidemiology.

This is a very rare congenital malformation of the central nervous system whose actual prevalence is not known. Reported prevalence is about 0.1 per 10,000 live births for cases of 20 weeks gestation or greater in Atlanta, a prevalence that had been adjusted upward 30% to account for prenatal terminations (Moore et al., 1997); 0.51 per 10,000 births in a Texas-Mexico border population whose prevalence ascertainment included prenatal terminations (Johnson, Suarez, Felkner, & Hendricks, 2004); 10.7 per 10,000 births in Northern China and 0.9 per 10,000 births in Southern China (Moore et al., 1997).

Gross Dysmorphology.

The neural tube is open from the midbrain to the spine. The defect of the skull and vertebral arch results both in anencephaly and an open spina bifida (Figure 1). Fetuses show absence of the cranial vault, with the defect extending with various degree to the vertebrae. The neck may be short or absent, facial dysmorphisms may be present and include a broad nose, exopthalamos, low-set and folded ears. Typically, posterior telencephalon, hindbrain and spinal cord tissue is externally exposed.

Histology.

In these cases, both the brain and spinal cord are exposed to the intra-amniotic environment resulting in destruction of the nervous tissues due to the inherent toxicity of the amniotic fluid. The same histological characteristics of anencephaly and myelomeningocele are detectable in these specimens (see below).

Prenatal diagnosis.

Absence of the cranial vault and spinal dysraphism is detectable by ultrasound. A disorganized mass of cerebral tissue is visible and cervical hyperextension may also be observed. Differential diagnosis includes: nuchal tumors (such as teratomas and lymphangiomas), Klippel–Feil syndrome (a disease caused by a failure of segmentation of the cervical vertebrae during early fetal development), and Jarcho–Levin syndrome, also known as spondylocostal dysostosis, an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by a shortened trunk, opisthotonus position of the head, short neck, barrel-shaped thorax, multiple wedge-shaped and block vertebrae, spina bifida, and rib anomalies (Chen, 2007).

Prognosis.

Craniorachischisis is a lethal condition: there is no cure or surgical intervention and the death of the newborn is unavoidable.

Anencephaly

Definition.

When the primary defect involves failure to close just the cranial portion of the neural tube, the defect is refered to as exencephaly (anencephaly). The degeneration of the cerebral-neural tissues due to the destructive exposure of the brain to the intra-amniotic environment converts the exencephaly defect to anencephaly (Golden & Harding, 2004; Timor-Tritsch, Greenebaum, & Monteagudo, 1996; Wilkins-Haug & Freedman, 1991)

Epidemiology.

The Center for Disease Control and preventin (CDC) estimates that each year, about 3 pregnancies per every 10,000 births in the United States will be affected by anencephaly.

Gross Dysmorphology.

Anencephaly is a defect in which there is absence of the structures derived from the forebrain and the skull. The calvarium is generally absent, the parietal, frontal and squama of the temporal and occipital bones appears as rudimentary fragments; the base of the skull is nearly normal (Goldstein & Filly, 1988) but is thick and flattened; the sphenoidal bone is abnormally shaped (Golden & Harding, 2004) resembing a “bat with folded wings” (Marin-Padilla, 1965). The facial bones appear normal and the face is generally normally structured (Figure 2), although the eyes often appear to protrude because of the shallowness of the orbits and the forehead is absent or shortened. Moreover, other associated facial abnormalities have been reported such as flattened nasal bridge and low-set ears (Stumpf et al, 1990).

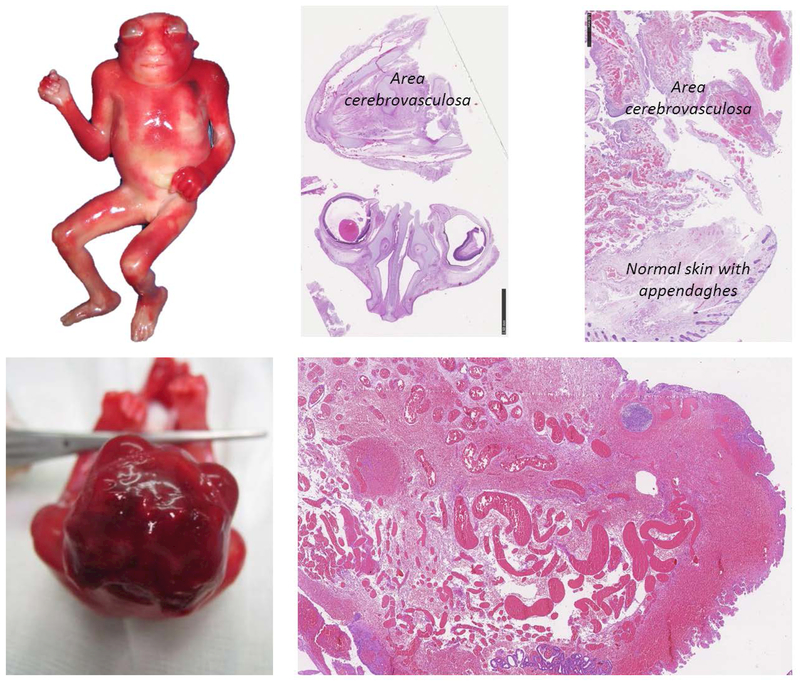

Figure 2.

Macroscopic and histologic features of anencephaly. The cranial vault is absent, the brain is not covered with bones, the skin is in continuity with the nervous tissue and the nervous tissue, called area cerebrovasculosa, is a mass of degenerated tissue. Histologically the typical aspect of area cerebrovasculosa are shown with the enlarged venous vessels with various dimension immersed in nervous tissues.

The brain remnants is called the area cerebrovasculosa (Figure 2). Its macroscopic aspect appears as a dark brown undifferentiated mass (Anand, Javia, & Lakhani, 2015); the residual amount of brain tissues varies, generally there is an absence of the structures of the forebrain (both diencephalon and telencephalon structures including thalamus and cerebrum) and midbrain, whereas the brainstem may appear to have been spared, or less severely involved. The pituitary is present, but it is hypoplastic and without the intermediate and posterior lobes.

Histology.

The residual cerebral tissue appears as an irregular mass containing vascular tissue, glia, and some neuroblasts or neurons surrounded by meninges (Golden & Harding, 2004) although some authors failed to find neurons in the area cerebrovasculosa (Ashwal et al., 1990). The overview shows a poorly structured mass consisting of blood vessels (Figure 2) scattered with connective tissue and islets of nervous tissue including interspersed astroglial cells, nerve cells, and cavities surrounded by the epithelium (Anand et al., 2015). The exposed cerebral area is covered by non-keratinising squamous epithelium that laterally is continuous with epidermis (Figure 2) (Golden & Harding, 2004). Interestingly, even though there is a severe rostral neural tube abnormality, the spinal cord in the anencephalic foetuses appears structurally normal (Anand et al., 2015).

Prenatal diagnosis.

The diagnosis is primarily based on the absence of a normally formed calvarium and brain above the orbital line (Goldstein & Filly, 1988). The area cerebrovasculosa may be detected as fluctuant echogenic tissue. Often polyhydramnios are present. The differential diagnosis between anencephaly and other causes of an absence of the cranial vault may include cases of head destruction related to amniotic bands (Stumpf et al., 1990). This distinction is very important for counseling families, because the destruction related to amniotic bands represents a sporadic event which would have a very low recurrence risk, whereas the presence of anencephaly increases the risk of occurrence of another NTD in any subsequent pregnancy. The differential diagnosis between these two entity with an of absence of the cranial vault relies on the presence or absence of othe malformations as anencephalic infants are usually isolated with no other associated malformations. Moreover, the cranial defect in cases of amniotic bands syndrome is asymmetric, whereas in the case of anencephaly it is symmetric (Goldstein & Filly, 1988; Keeling & Kjaer, 1994).

Prognosis.

Anencephaly is a lethal condition. Detection of anencephaly during early gestation is generally followed by legal interruption of the pregnancy. In cases of pregnancies that continue to term, most anencephalic newborns die within the first day or two post-parturition (Stumpf et al., 1990).

Myelomeningocele

Definition.

In myelomeningocele, the developmental defect involves the failure to close the posterior spinal portion of the neural tube, more frequently the lumbar portion is the region which fails to fuse. In this defect, the meningeal sac herniates through a bony defect of the vertebral arch (Figures 3–4). In some cases, a clear open defect that involves the spinal cord, but without a protruding meningeal sac, is defined as a myelocele. Therefore, a myelocele is an open defect without the cystic component (Figure 3–4).

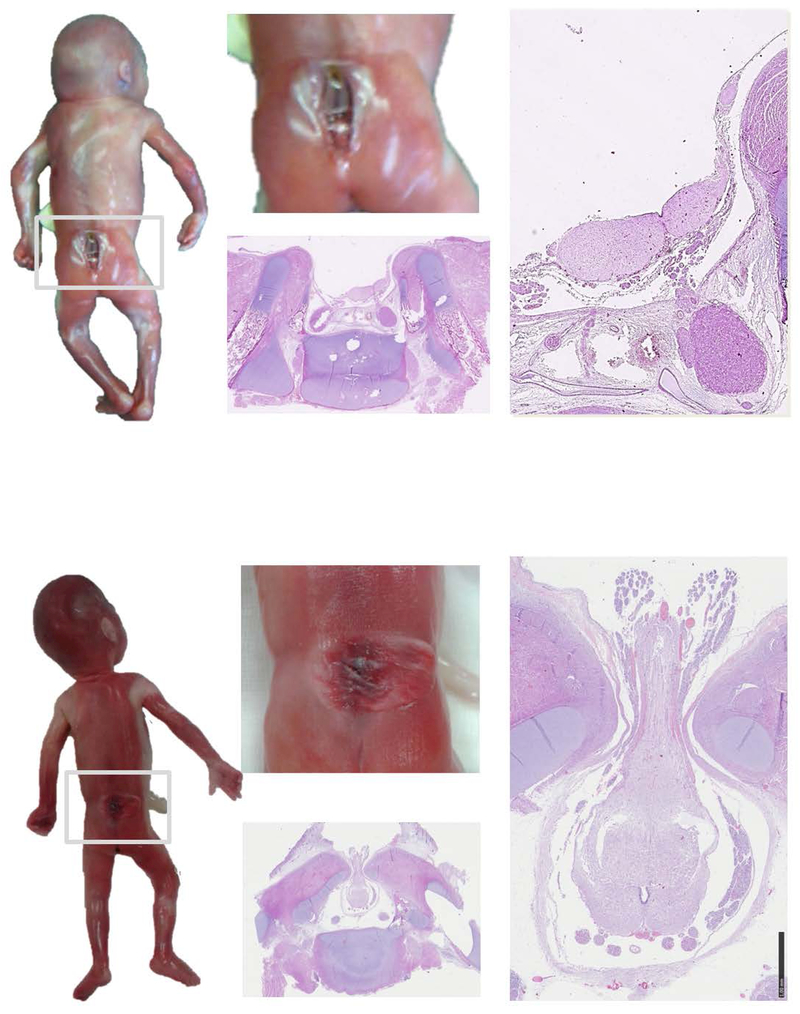

Figure 3.

Macroscopic and histologic aspect of myelocele (upper panel) and myelomeningocele (lower panel).

In myelocele the foetus presented a clear open defect in the lumbar-sacral region. The spinal cord is displayable in the depth of the cleft. The defect is open and no meningeal sac is protruding. The histological sections show the bone defect of the vertebral arches and the exposed spinal cords. In this case the spinal cord is not closed in its typical shape but is divided in two halves appearing as an “open book”. The remnant of the ependymal layer is visible at the surface, covering the center of the two halves.

In myelomeningocele the foetus presented a clear meningeal cystic sac that contains cerebro-spinal fluid and nervous tissue. Note the translucent appearance of the nervous tissue. The histological sections show the protrusion of the medulla through the bone defect of the vertebral arches. Meninges are also herniated forming the cystic mass.

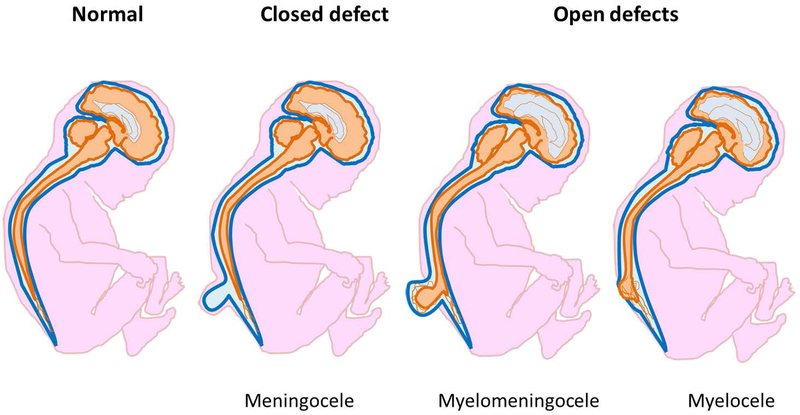

Figure 4.

Schematic representations of central nervous system appearance in normal foetus, meningocele, myelocele and myelomeningocele.

In meningocele meninges are displaced through a bone defect of the vertebral arches; spinal cord is not involved in the protrusion and the brain is normal.

In cases with myelocele and melomeningocele the neural tube defect is associated with Chiari malformation type II, characterised by the herniation of cerebellar vermis through the foramen magnum

Epidemiology.

It is the most common form of spina bifida aperta in humans, with an estimated incidence according to the CDC of 1.8 per 10,000 live births in the United States.

Gross Dysmorphology.

In myelomeningocele, a cystic mass protruding though a bony defect in the vertebral arches is detectable. The size and shape of the lesion can vary significantly and may include cerebrospinal fluid drainage. The neural tissues appears translucent through the protruded meningeal sac and the neural placode, a segment of flat, non-neurulated embryonic neural tissue, is externally shown and protrudes above skin surface (Figure 4). In case of myelocele the cystic mass is absent and the neural tissue is clearly detectable though the vertebral cleft and the placode is flush with the surface of the skin (Figure 4). The spinal cord above the defect may be distorted in position and shape, but it is not overtly malformed (John L. Emery & Lendon, 1973; Naik & Emery, 1968).

Myelomeningecele and myelocele are usually associated with Chiari malformation type II (Figures 4–5), because of the traction of the brain stem from below due to tethering of the open spinal cord through the vertebral defect. Indeed, the brain stem is elongated, there is caudal elongation of the medulla and the fourth ventricle, cerebellar vermis is displaced into the foramen magnum (Figures 4–5). As a result, the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid through the ventricles is compromised, resulting secondarily in hydrocephalus. There is also an abnormal orientation of the cervical nerve roots that lack their usual downward oblique orientation. Moreover, in these cases, the cerebellum appears smaller than the normal dimension and presents an altered contour (Del Bigio, 2010).

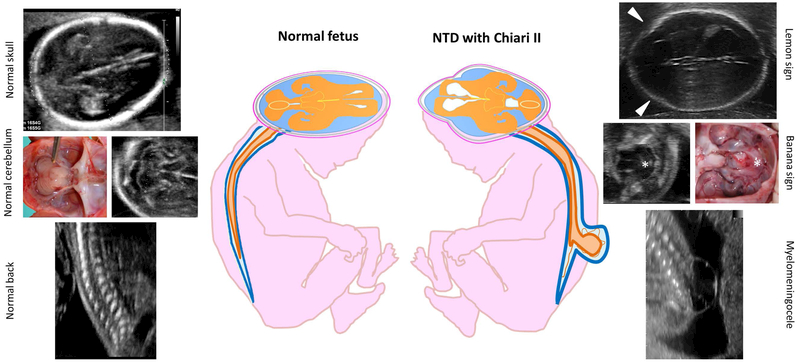

Figure 5.

Prenatal signs of open neural tube defects

Differences between the normal fetus and fetus affected by open neural tube defects are shown. Note the appearance of the transverse section of cerebellum at the ultrasound scan in normal fetus (typical butterfly shape) and the appearance of the herniated cerebellum in Chiari malformation type II (characteristic banana shape, asterisk). Note also the appearance of the transverse section of the skull comparing the shape of the normal fetus with the lemon shaped skull of the NTD fetus. Lemon sign represents the scalloping of the frontal bones (arrows).

Histology.

The meningeal cystic sac contains cerebrospinal fluid, nerve roots and spinal cord. Both spinal cord and meninges are damaged and displaced through the bony opening (Figure 3). Histologically, the medulla is generally hypervascularised and abnormal: in some cases the spinal cord could be closed with dilated central canal, while in other cases the spinal cord appears open as a flat mass (Golden & Harding, 2004). In Chiari malformation type II, the cerebellar structure appears modified due to its flattened elongation that extend downward below the level of the foramen magum: the structure may be atrophied with decreased neurons and chronic astroglial changes (Del Bigio, 2010). Historical studies based on cell count demonstrated that in these cases, the central lobes of the cerebellum develop normally but subsequently acquire an irregular degeneration and arrest of growth (J L Emery & Gadsdon, 1975). This cerebellar local atrophy might depend on local ischemia (Poretti, Prayer, & Boltshauser, 2009).

Prenatal diagnosis.

The detection rate of this type of open spina bifida by ultrasound is very high (virtually 100%) thanks to the indirect cranial signs including the “lemon” and the “banana” sign (Figure 5) (Nicolaides, Gabbe, Campbell, & Guidetti, 1986). The lemon sign describes the shape of the skull and represents the scalloping of the frontal bones: loss of the convex outward shape of the frontal bones with mild flattening. It is present in virtually all fetuses with myelomeningocele between 16 and 24 weeks of gestation. The banana sign describes the shape of the cerebellum and is due to the downward traction of the cerebellum, most likely related to the leakage of spinal fluid from the open spinal defect. Foetal repair of myelomeningocele has been shown to reverse the cerebellar and brainstem displacement (Adzick et al., 2011).

Direct findings of open spina bifida may be also detected by ultrasound or fetal MRI: sections of the spine demonstrates vertebral dysraphism with an associated fluid-filled posterior bulging of meninges forming the cystic sac often containing internal septations. Sometimes spinal dysraphism without posterior cyst may be observed; this is the case of myelocele. During pregnancy a progressive deterioration of leg movements may be observed due to the damage of the spinal cord and nerves. Clubfoot, which is a deformity characterized by abnormal foot position in which the foot is internally rotated, is virtually always detectable.

Prognosis.

In the absence of other additional serious congenital malformations, newborns with myelomeningocele or myelocele survive with various degree of neurological impairment. Although controversial, cesarean section may be indicated to prevent additional neurological defects related to the mode of delivery (Thompson, 2009). Clinical characteristics depend on the level of the lesion: motor and sensorial deficit occur at levels below the spinal lesion and may be associated with bladder and rectal incontinence (Golden & Harding, 2004) and sexual dysfunction (Thompson, 2009). Intellectual disability is relatively infrequent (20–25% of cases) and generally related to hydrocephalus (Copp et al., 2015). According to the results of the Management of Myelomeningocele Study trial (MOMS), to improve the prognosis of the affected foetuses, pre-delivery surgical solutions may be offered in selected cases, performing an in utero surgical intervention. In fact, the results of the MOMS study show that surgery performed prior to 26 weeks of gestation may preserve neurologic function, reverse the hindbrain herniation of Chiari II malformation, and decrease the need to place postnatally a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt (Adzick et al., 2011). However, the prenatal surgery increases the risk of premature rupture of the membranes and preterm delivery (Adzick et al., 2011).

Closed neural tube defects

Encephalocele

Definition.

Encephalocele is a herniation such as a sac-like protrusion of the brain and/or the meninges through an opening in the skull. According to the type of tissue involved in the herniation, cephaloceles are classified as meningocele (herniation of meninges), encephalomeningocele (herniation of meninges and brain), and encephalomeningocystocele (herniation of meninges, brain and ventricle) (Figure 6) (Pilu, Buyukkurt, Youssef, & Tonni, 2014).

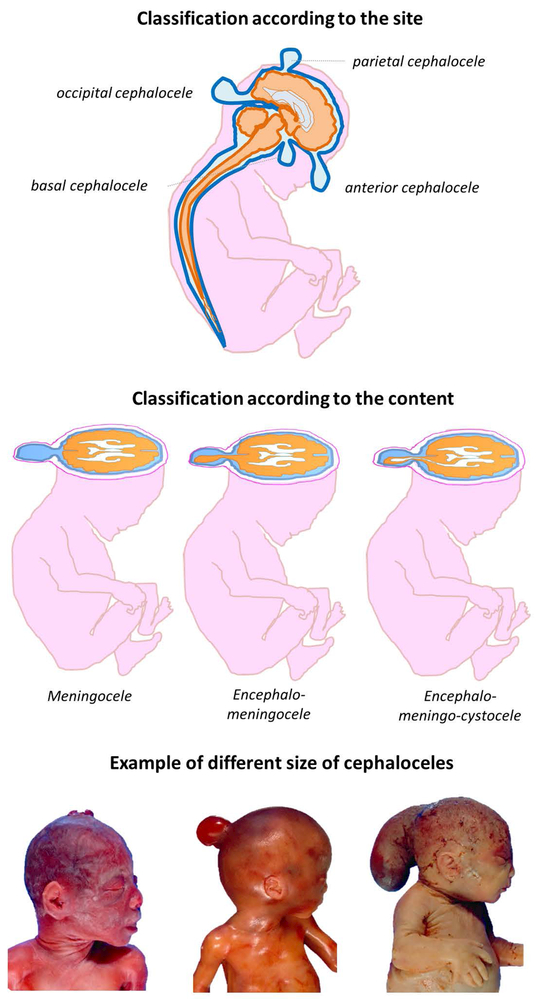

Figure 6.

Type and site of cephalocele

Upper panel shows a schematic representation of possible cephalocele localization.

Middle panel shows a schematic representation of different type of cephalocele classified according to the content of the herniated mass.

Lower panel shows macroscopic aspect of human fetuses affect by cephalocele.

Epidemiology.

CDC estimates that each year about 1 out of every 10,000 babies are born with an encephalocele in the United States.

Gross Dysmorphology.

Encephaloceles can occur in any part of the cranial vault; cystic mass passes through a cleft of the calvarium squamae and approximately 90% of cases involve the midline. According to the site of the herniation, encephaloceles are classified as: anterior, with lesion located between the bregma and the anterior aspect of the ethmoid bone; parietal, with lesion located between the bregma and the lambdoid suture; occipital, with lesion located between the lambdoid suture and foramen magnum (Figure 6). This location is the most common, involving almost 75% of all encephaloceles.

The anterior encephalocele is further sub-classified into frontal, sincipital and basal varieties, according to the localisation of the defect. The frontal encephaloceles are external lesions that cause craniofacial abnormalities and are typically found near the glabella, the root of the nose. They are subdivided into naso-frontal, naso-ethmoid and naso-orbital types. Basal encephaloceles are internal lesions which occur within the nose, the pharynx, or the orbit. They are normally classified into three types: spheno-orbital, spheno-maxillary and spheno-pharyngeal (Pilu et al., 2014).

The occipital encephalocele may occur in association with a Chiari III malformation. The Chiari type III malformation is characterised by occipital and/or high cervical encephalocele associated with caudal displacement of the lower brain stem into the spinal canal, and herniation of the cerebellar tissues into the herniated sac.

The macroscopic aspect of the encephalocele is a round, soft, compressible nodule with sub-scalp localisation (Figure 6) (Gao, Massimi, Rogerio, Raybaud, & Di Rocco, 2014). The mass may appear solid or cystic according to the content of the herniation, and it is generally covered by alopecic skin that could be surrounded by a ring of hair determining the so called “hair collar signs” (Gao et al., 2014), although sometimes hypertrichosis may be present over the lesion (Sewell, Chiu, & Drolet, 2015). Sometimes the surface of encephalocele appears bluish, translucent or glistening, and capillary malformations are detectable (Sewell et al., 2015)

Due to its patent intracranial communication, encephaloceles modify its dimension (enlargement/reduction) with the modification of intracranial pressure: it enlarges during increase of pressure such as during Valsalva maneuver (Sewell et al., 2015) including crying and suction.

Histology.

Solid variants results from the proliferation of neuroglial and fibrous tissues and hyperplasia of the meningeal cells. The herniated mass may contain various types of tissues including cerebral and cerebellar portion, ventricles with choroid plexus, gray matter heterotopias. Brain tissues involved in the herniation are generally nonfunctional and appears abnormal with gliosis, necrosis, reactive astrocytosis. Meningeal inflammation has been detectable (Castillo, Quencer, & Dominguez, 1992; Isik, Elmaci, Silav, Celik, & Kalelioglu, 2009; Ivashchuk, Loukas, Blount, Tubbs, & Oakes, 2015). Aberrant deep veins and ectopic venous sinuses are also often observed (Ivashchuk et al., 2015). Cystic variants contain cerebro-spinal fluid (Gao et al., 2014).

Prenatal diagnosis.

A sac protruding through a bony defect may be detected by ultrasound. Associated brain abnormalities may include cerebral ventriculomegaly and microcephaly (Cameron & Moran, 2009). In case of a Chiari III malformation, a protrusion through a defect of the occipital squama and or the arch of the first cervical vertebra may be observed, associated with a small posterior cranial fossa with low tentorial attachment, scalloping of the clivus and herniation of the cerebellum into the defect and hydrocephalus (Caldarelli, Rea, Cincu, & Di Rocco, 2002; Ivashchuk et al., 2015). In the absence of identifying a skull defect, the differential diagnosis includes a wide range of craniofacial mass, according to the site of the lesion, such as a teratoma, a lynphangiona, a haemangioma, nasolacrimal duct cyst, neuroglia heterotopia, lipoma (Cameron & Moran, 2009; Connor, 2010).

Prognosis.

Clinical characteristic depends on the localisation and content of the herniated mass. The more rostral the site, the better the prognosis (Thompson, 2009). Moreover, the underlying brain involvement and hydrocephalus affects the prognosis. In cases with mechanical effects of distortion and traction of the brain stem thought the herniation, various degree of developmental delay, epilepsy and motor and sensorial nerve dysfunction may occur (Caldarelli et al., 2002; Gao et al., 2014). The treatment of encephaloceles requires a surgical correction.

Meningocele.

Definition.

Although macroscopically similar to a myeolomeningocele (Figure 3), meningocele is a closed spina bifida, comparable to encephalocele, whereby the defect consists in herniation of meninges through the vertebral column. Although the herniation of the meninges through the vertebral arch defect, the spinal cord resides within the spinal canal (McComb, 2015). Differences between meningocele, myeolomeningocele and myelocele are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2:

Differential diagnosis between meningocele, myelomeningocele and myelocele

| Meningocele | Myelomeningocele | Myelocele | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of defect | Closed | Open | Open |

| Ultrasound aspects | |||

| Posterior anechogenic cystic mass (sac-like protrusion) from the spine | + | + | − |

| Presence of septa in the sac | − | + | // |

| Abnormality of vertebral bones (absence of the arches) | + | + | + |

| Abnormal shape of skull (lemon sign) | − | + | + |

| Abnormal shape of cerebellum (banana sign) | − | + | + |

| Association with Chiari type II malformation | − | + | + |

| Association with hydrocephalus | − | + | + |

| Association with clubfoot | − | + | + |

| Macroscopic aspects of the lesion | |||

| Absence of vertebral arches | + | + | + |

| Meningeal herniation though the bones defect | + | + | − |

| Presence of neural tissues in the meningeal sac (medulla and/or nerves) | − | + | // |

| External exposition of placode | − | + | + |

| Covered by skin | + | − | − |

Although macroscopically similar, meningocele and myelomeningocele represent two opposite types of spina bifida, a closed and open defect respectively with different prognosis. Because of the similar macroscopic aspect of the herniated sac, prenatal ultrasound differentiation of the cystic lesion may be difficult.

In contrast, myelomeningocele and myelocele are macroscopically different but they represent the same type of spina bifida, an open defect, with the same clinical implications. The macroscopic distinction between myelomeningocele and myelocele is based on the location of the neural placode. When the placode is pushed out of the confines of the canal and through the vertebra, and a cutaneous defect is created by expansion of the subarachnoid space, a myelomeningocele is present. Otherwise, in case of myelocele, the subarachnoid space is not expanded, the placode remains in plane with or deep to the cutaneous surface

Epidemiology.

The actual incidence of meningoceles is unknown.

Gross Dysmorphology.

In meningocele, the dura and the arachnoid herniate through the vertebral arch defect whereas the spinal cord remains in the normal position into the spinal canal. The herniated mass is covered by skin that is characterised by atrophic epidermis without skin appendages (Golden & Harding, 2004). Sometimes the skin may display different degree of dysplasia (McComb, 2015). The lesion is peduncolated to varying degrees and is generally easily compressible and well transilluminable.

Histology.

A protrusion in continuity with epidermal tissue is detectable. The protruded mass is formed by extremely thick meninges and generally contains vascularized stromal tissue. The surface of the herniated mass generally does not presented skin appendages.

Prenatal diagnosis.

By ultrasound may be seen spinal dysraphism with an associated cystic mass. The characteristics of the cystic mass are comparable with that of the myelomeningocele, although they lack septa in the herniated mass, and the cranial anatomy is unremarkable (Ghi et al., 2006).

Prognosis.

Cases with meningocele generally have normal neurologic examination without deformity of the lower extremities or sphincter dysfunction (McComb, 2015). The treatment of meningocele is a surgical correction.

Spina bifida occulta.

Definition.

Spina bifida occulta represents a spectrum of a spinal cord abnormalities related to abnormal development of the embryonic tail bud. The defect involves the low lumbar and sacral regions, and results in closed defects with incomplete vertebral arches. Spina bifida occulta is often associated with other skeletal defects including sacral agenesis.

Epidemiology.

The actual incidence of spina bifida occulta is unknown (Hertzler, DePowell, Stevenson, & Mangano, 2010).

Gross Dysmorphology.

The presence of cutaneous stigmata of the low back may be the only signs of occult spina bifida. Cutaneous markers include nevi, lumps, depigmented region, subcutaneous lipomas, capillary hemangiomas, hair tufts (localized hypetricosis) and dermal sinus tract (Hertzler et al., 2010; Sewell et al., 2015). Structural abnormalities may also been detected such as an asymmetrical gluteal cleft, scoliosis and leg length discrepancy.

Prenatal diagnosis.

No secondary cranial findings are detectable thus the prenatal diagnosis is hard and in such cases is a challenge (Coleman, Langer, & Horii, 2014). The commonest form of closed spinal dysraphism detectable in utero is the type associated with intradural lipoma. Its aspect may affect the sensitivity of differential diagnosis and the ability of the correct identification during the prenatal diagnosis: during intra-uterine life, meningoceles and lipomas have a very similar appearance and may be very difficult or impossible to distinguish (Pierre-Kahn & Sonigo, 2003). In fact, by ultrasound, lipomas typically appear as echogenic masses (Ghi et al., 2006) much like a meningocele. Post-natally, high resolution ultrasound may be employed until the 6th month of life, before the ossification of the vertebral body, but the sensitivity is low, especially in cases of a subcutaneous mass (Sewell et al., 2015). The more appropriate diagnostic technique is magnetic resonance, but this procedure is limited by its cost, availability, and the need for sedation for many children.

Prognosis.

This group of defects represents a less severe form of malformation: more often, this problem may be detected only later in life, because nerves and the spinal cord are not affected and therefore it does not usually result in disabilities. In other cases spinal cord anomalies may occur and include hydromyelia (overdistension of the central canal), diplomyelia (longitudinal duplication of the spinal cord), diastematomyelia (longitudinal split of the spinal cord) and tethering of the lower end of the cord (Golden & Harding, 2004). Neurological symptoms start when the damage and/or traction of the cord occurs. During the intrauterine life, the spinal cord grows slower than the spinal column. The caudal spinal cord (also called conus medullaris) reaches its normal level only after birth, and the symptoms may start through the extrauterine life when the cord is insulted (Sewell et al., 2015). Sometimes this occurs in childhood, other times this occurs later in life, in case of thickening of filum terminale (increased fibrosis leading to progressive loss of elasticity), increased physical activity, development of spinal stenosis or occurrence of lumbar trauma (Hertzler et al., 2010). Neurosurgical intervention is the therapy of choice in cases of symptomatic patients with neurological deterioration.

Prevention of Neural Tube Defects

NTDs are known as one of the few birth defects in which primary preventive strategies are available and effective. Pioneering studies by Smithells and colleagues in the UK (Smithells et al., 1980; Smithells, Sheppard, & Schorah, 1976) showed the importance of vitamin intake during pregnancy with respect to NTD outcome. Subsequently, a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was initiated in 1991 by the UK Medical Council (MRC Vitamin Study Research Group, 1991). This study demonstrated that supplementation with 4 mg folic acid per day resulted in a threefold reduction in NTD recurrence risk. Together with several non-randomised trials, this data indicate that folic acid supplementation during pregnancy in a dose range of ~0.4–5 mg per day prevents NTD births. The biological and molecular mechanisms of this prevention are yet to be elucidated, despite the large number of studies conducted using animal studies to test various hypotheses mechanistically (Blom et al., 2006), as folate plays a pivotal role in numerous cellular reactions, including purines and thymidylate production and SAM synthesis (S-adenosyl-methionine), which is the cellular methyl donor used in methylation reactions for DNA, proteins including histones and lipids (Crider, Yang, Berry, & Bailey, 2012).

Maternal folic acid periconceptional supplementation strategies have been implemented in a number of countries (Blom et al., 2006) however epidemiological studies have shown that not all NTDs are prevented and a sub-group of “folic acid-resistant” NTDs still occur (Mosley et al., 2009; MRC Vitamin Study Research Group, 1991). Among other possible supplements fundamental for correct neural tube closure, inositol may represent a tool for those non folate responsive NTDs. Indeed, in non-randomszed studies supported by experimental evidence on animal models (Copp et al., 2013; N. Greene & Copp, 1997), inositol supplementation appears to reduce NTDs recurrence. In a recent randomised, placebo-controlled trial no recurrence was observed in women supplemented both with folic acid and inositol (N. D. E. Greene et al., 2016). Larger and statistically powerful studies are expected to investigate this possible new preventive strategy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors appreciate the financial support of the various funding agencies that contributed to this effort. RHF was supported by NIH grants HD081216, HD067244, HD083809, as well as support from the March of Dimes (16-FY16–169). VM was supported by Università degli studi di Milano grant (Linea 2–2017).

Footnotes

There is no conflict of interest to be disclosed

REFERENCES

- Adzick NS, Thom EA, Spong CY, Brock JW 3rd, Burrows PK, Johnson MP, … Farmer DL (2011). A randomized trial of prenatal versus postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. The New England Journal of Medicine, 364(11), 993–1004. 10.1056/NEJMoa1014379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand MK, Javia MD, & Lakhani CJ (2015). Development of brain and spinal cord in anencephalic human fetuses. Anatomy, 9(2), 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JL, Waller DK, Canfield MA, Shaw GM, Watkins ML, & Werler MM (2005). Maternal obesity, gestational diabetes, and central nervous system birth defects. Epidemiology, 16(1), 87–92. 10.1097/01.ede.0000147122.97061.bb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwal S, Peabody JL, Schneider S, Tomasi LG, Emery JR, & Peckham N (1990). Anencephaly: Clinical determination of brain death and neuropathologic studies. Pediatric Neurology, 6(4), 233–239. 10.1016/0887-8994(90)90113-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe H, Kancherla V, Moorthie S, Darlison MW, & Modell B (2018). Estimates of global and regional prevalence of neural tube defects for 2015: A systematic analysis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 10.1111/nyas.13548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom HJ, Shaw GM, den Heijer M, & Finnell RH (2006). Neural tube defects and folate: case far from closed. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 7(9), 724–31. 10.1038/nrn1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brender JD, Felkner M, Suarez L, Canfield MA, & Henry JP (2010). Maternal Pesticide Exposure and Neural Tube Defects in Mexican Americans. Annals of Epidemiology, 20(1), 16–22. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldarelli M, Rea G, Cincu R, & Di Rocco C (2002). Chiari type III malformation. Child’s Nervous System, 18(5), 207–210. 10.1007/s00381-002-0579-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron M, & Moran P (2009). Prenatal screening and diagnosis of neural tube defects. Prenatal Diagnosis. 10.1002/pd.2250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael SL, Rasmussen SA, Lammer EJ, Ma C, & Shaw GM (2010). Craniosynostosis and nutrient intake during pregnancy. Birth Defects Research Part A - Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 88(12), 1032–1039. 10.1002/bdra.20717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael SL, Yang W, Roberts E, Kegley SE, Padula AM, English PB, … Shaw GM (2014). Residential agricultural pesticide exposures and risk of selected congenital heart defects among offspring in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Environmental Research, 135, 133–138. 10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo M, Quencer RM, & Dominguez R (1992). Chiari III malformation: Imaging features. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 13(1), 107–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CP (2007). Prenatal diagnosis of iniencephaly. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 10.1016/S1028-4559(08)60021-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman BG, Langer JE, & Horii SC (2014). The Diagnostic Features of Spina Bifida: The Role of Ultrasound. Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy, 37, 179–196. 10.1159/000364806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor SEJ (2010). Imaging of skull-base cephalocoeles and cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Clinical Radiology. 10.1016/j.crad.2010.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copp AJ, Adzick NS, Chitty LS, Fletcher JM, Holmbeck GN, & Shaw GM (2015). Spina Bifida. Nature Reviews, Disease Primers, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copp AJ, & Greene NDE (2013). Neural tube defects-disorders of neurulation and related embryonic processes. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology. 10.1002/wdev.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copp AJ, Stanier P, & Greene NDE (2013). Neural tube defects: Recent advances, unsolved questions, and controversies. The Lancet Neurology. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70110-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordier S, Bergeret A, Goujard J, Ha M-C, Aymé S, Bianchi F, … Scarpelli A (1997). Congenital malformations and maternal occupational exposure to glycol ethers. Epidemiology, 8(4), 355–363. 10.1097/00001648-199707000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crider KS, Yang TP, Berry RJ, & Bailey LB (2012). Folate and DNA methylation: a review of molecular mechanisms and the evidence for folate’s role. Advances in Nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 3(1), 21–38. 10.3945/an.111.000992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bigio MR (2010). Neuropathology and structural changes in hydrocephalus. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 10.1002/ddrr.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietl J (2005). Maternal obesity and complications during pregnancy. Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 10.1515/JPM.2005.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery JL, & Gadsdon DR (1975). A quantitative study of the cell population of the cerebellum in children with myelomeningocele. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. Supplement, (35), 20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery JL, & Lendon RG (1973). The local cord lesion in neurospinal dysraphism (meningomyelocele). The Journal of Pathology, 110(1), 83–96. 10.1002/path.1711100110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Massimi L, Rogerio S, Raybaud C, & Di Rocco C (2014). Vertex cephaloceles: A review. Child’s Nervous System. 10.1007/s00381-013-2249-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghi T, Pilu G, Falco P, Segata M, Carletti a, Cocchi G, … Rizzo N (2006). Prenatal diagnosis of open and closed spina bifida. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology : The Official Journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 28(January), 899–903. 10.1002/uog.3865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden JA, & Harding BN (2004). Pathology and Genetics: Developmental Neuropathology. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RB, & Filly RA (1988). Prenatal diagnosis of anencephaly: Spectrum of sonographic appearances and distinction from the amniotic band syndrome. American Journal of Roentgenology, 151(3), 547–550. 10.2214/ajr.151.3.547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene N, & Copp A (1997). Inositol prevents folate-resistant neural tube defects in the mouse. Nature Medicine, 3(1), 60–66. 10.1038/nm0197-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene NDE, Leung K-Y, Gay V, Burren K, Mills K, Chitty LS, & Copp AJ (2016). Inositol for the prevention of neural tube defects: a pilot randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Nutrition, 1–10. 10.1017/S0007114515005322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene NDE, Stanier P, & Copp AJ (2009). Genetics of human neural tube defects. Human Molecular Genetics, 18(R2). 10.1093/hmg/ddp347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal J, Carmichael SL, Ma C, Lammer EJ, & Shaw GM (2008). Maternal periconceptional smoking and alcohol consumption and risk for select congenital anomalies. Birth Defects Research Part A - Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 82(7), 519–526. 10.1002/bdra.20461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MJ, & Juriloff DM (2007). Mouse mutants with neural tube closure defects and their role in understanding human neural tube defects. Birth Defects Research Part A - Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 10.1002/bdra.20333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MJ, & Juriloff DM (2010). An update to the list of mouse mutants with neural tube closure defects and advances toward a complete genetic perspective of neural tube closure. Birth Defects Research Part A - Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 10.1002/bdra.20676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks KA, Nuno OM, Suarez L, & Larsen R (2001). Effects of hyperinsulinemia and obesity on risk of neural tube defects among Mexican Americans. Epidemiology, 12(6), 630–635. 10.1097/00001648-200111000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzler D. a, DePowell JJ, Stevenson CB, & Mangano FT (2010). Tethered cord syndrome: a review of the literature from embryology to adult presentation. Neurosurgical Focus, 29(July), E1 10.3171/2010.3.FOCUS1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins GM, Meuli M, Meuli-Simmen C, Jordan MA, Heffez DS, & Blakemore KJ (1996). Acquired spinal cord injury in human fetuses with myelomeningocele. Pediatric Pathology & Laboratory Medicine : Journal of the Society for Pediatric Pathology, Affiliated with the International Paediatric Pathology Association, 16(5), 701–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isik N, Elmaci I, Silav G, Celik M, & Kalelioglu M (2009). Chiari malformation type III and results of surgery: a clinical study: report of eight surgically treated cases and review of the literature. Pediatric Neurosurgery, 45(1), 19–28. 10.1159/000202620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivashchuk G, Loukas M, Blount JP, Tubbs RS, & Oakes WJ (2015). Chiari III malformation: a comprehensive review of this enigmatic anomaly. Child’s Nervous System. 10.1007/s00381-015-2853-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KMK, Suarez L, Felkner MM, & Hendricks K (2004). Prevalence of Craniorachischisis in a Texas-Mexico Border Population. Birth Defects Research Part A - Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 70(2), 92–94. 10.1002/bdra.10143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai H, Sawa A, Chen RW, Leeds P, & Chuang DM (2004). Valproic acid inhibits histone deacetylase activity and suppresses excitotoxicity-induced GAPDH nuclear accumulation and apoptotic death in neurons. Pharmacogenomics Journal, 4(5), 336–344. 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling JW, & Kjaer I (1994). Diagnostic distinction between anencephaly and amnion rupture sequence based on skeletal analysis. Journal of Medical Genetics, 31(11), 823–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy D, Chitayat D, Winsor EJT, Silver M, & Toi A (1998). Prenatally diagnosed neural tube defects: Ultrasound, chromosome, and autopsy or postnatal findings in 212 cases. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 77(4), 317–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshnood B, Loane M, Walle H De, Arriola L, Addor M, Barisic I, … Dolk H (2015). Long term trends in prevalence of neural tube defects in Europe : population based study. British Medical Journal, 351, 1–6. 10.1136/bmj.h5949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirke PN, Molloy AM, Daly LE, Burke H, Weir DG, & Scott JM (1993). Maternal plasma folate and vitamin B12 are independent risk factors for neural tube defects. The Quarterly Journal of Medicine, 86(11), 703–8. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8265769 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammer EJ, Sever LE, & Oakley GPJ (1987). Teratogen update: valproic acid. Teratology, 35(3), 465–473. 10.1002/tera.1420350319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leck I (1974). Causation of neural tube defects: Clues from epidemiology. British Medical Bulletin, 30(2), 158–163. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Ren A, Zhang L, Ye R, Li S, Zheng J, … Li Z (2006). Extremely high prevalence of neural tube defects in a 4-county area in Shanxi Province, China. Birth Defects Research.Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 76(4), 237–240. 10.1002/bdra.20248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhang L, Ye R, Pei L, Liu J, Zheng X, & Ren A (2011). Indoor air pollution from coal combustion and the risk of neural tube defects in a rural population in shanxi province, China. American Journal of Epidemiology, 174(4), 451–458. 10.1093/aje/kwr108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhang L, Li Z, Jin L, Zhang Y, Ye R, … Ren A (2016). Prevalence and trend of neural tube defects in five counties in Shanxi province of Northern China, 2000 to 2014. Birth Defects Research. Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 106(4), 267–274. 10.1002/bdra.23486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupo PJ, Symanski E, Kim Waller D, Chan W, Langlois PH, Canfield MA, & Mitchell LE (2011). Maternal exposure to ambient levels of Benzene and Neural tube defects among offspring: Texas, 1999–2004. Environmental Health Perspectives, 119(3), 397–402. 10.1289/ehp.1002212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M (1965). Study of the skull in human cranioschisis. Acta Anatomica (Basel), 62, 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McComb JG (2015). A practical clinical classification of spinal neural tube defects. Child’s Nervous System: ChNS: Official Journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery, 31(10), 1641–1657. 10.1007/s00381-015-2845-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador KJ, Baker GA, Finnell RH, Kalayjian LA, Liporace JD, Loring DW, … Wolff MC (2006). In utero antiepileptic drug exposure: Fetal death and malformations. Neurology, 67(3), 407–412. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000227919.81208.b2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CA, Li S, Li Z, Hong SX, Gu HQ, Berry RJ, … Erickson JD (1997). Elevated rates of severe neural tube defects in a high-prevalence area in northern China. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 73(2), 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti ME, Bar-Oz B, Fried S, & Koren G (2005). Maternal hyperthermia and the risk for neural tube defects in offspring: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 10.1097/01.ede.0000152903.55579.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosley BS, Cleves MA, Siega-Riz AM, Shaw GM, Canfield MA, Waller DK, … Hobbs CA (2009). Neural tube defects and maternal folate intake among pregnancies conceived after folic acid fortification in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 169(1), 9–17. 10.1093/aje/kwn331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. (1991). Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. Lancet, 338(8760), 131–137. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90133-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAIK DR, & EMERY JL (1968). The Position of the Spinal Cord Segments Related to the Vertebral Bodies in Children with Meningomyelocele and Hydrocephalus. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 10, 62–68. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1968.tb04848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu T, Uwabe C, & Shiota K (2000). Neural tube closure in humans initiates at multiple sites: Evidence from human embryos and implications for the pathogenesis of neural tube defects. Anatomy and Embryology, 201(6), 455–466. 10.1007/s004290050332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaides KH, Gabbe SG, Campbell S, & Guidetti R (1986). ULTRASOUND SCREENING FOR SPINA BIFIDA: CRANIAL AND CEREBELLAR SIGNS. The Lancet, 328(8498), 72–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91610-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan R (2006). Etiology, pathogenesis and prevention of neural tube defects. Congenital Anomalies. 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2006.00104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padula AM, Tager IB, Carmichael SL, Hammond SK, Yang W, Lurmann F, & Shaw GM (2013). Ambient air pollution and traffic exposures and congenital heart defects in the san joaquin Valley of California. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 27(4), 329–339. 10.1111/ppe.12055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai YJ, Leung KY, Savery D, Hutchin T, Prunty H, Heales S, … Greene NDE (2015). Glycine decarboxylase deficiency causes neural tube defects and features of non-ketotic hyperglycinemia in mice. Nature Communications, 6 10.1038/ncomms7388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre-Kahn A, & Sonigo P (2003). Lumbosacral lipomas: In utero diagnosis and prognosis. Child’s Nervous System, 19(7–8), 551–554. 10.1007/s00381-003-0777-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilu G, Buyukkurt S, Youssef A, & Tonni G (2014). Cephalocele. Visual Encyclopedia of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology - VISUOG. [Google Scholar]

- Poretti A, Prayer D, & Boltshauser E (2009). Morphological spectrum of prenatal cerebellar disruptions. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2008.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray JG (2001). Preconception care and the risk of congenital anomalies in the offspring of women with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. QJM, 94(8), 435–444. 10.1093/qjmed/94.8.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray JG, & Blom HJ (2003). Vitamin B12 insufficiency and the risk of fetal neural tube defects. QJM - Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians, 96(4), 289–295. 10.1093/qjmed/hcg043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren A, Qiu X, Jin L, Ma J, Li Z, Zhang L, … Zhu T (2011). Association of selected persistent organic pollutants in the placenta with the risk of neural tube defects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(31), 12770–5. 10.1073/pnas.1105209108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righi E, Bechtold P, Tortorici D, Lauriola P, Calzolari E, Astolfi G, … Aggazzotti G (2012). Trihalomethanes, chlorite, chlorate in drinking water and risk of congenital anomalies: A population-based case-control study in Northern Italy. Environmental Research, 116, 66–73. 10.1016/j.envres.2012.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitsu H, Yamada S, Uwabe C, Ishibashi M, & Shiota K (2004). Development of the posterior neural tube in human embryos. Anatomy and Embryology, 209(2), 107–117. 10.1007/s00429-004-0421-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salih MA, Murshid WR, & Seidahmed MZ (2014). Epidemiology, prenatal management, and prevention of neural tube defects. Saudi Medical Journal. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RJ, Romitti PA, Burns TL, Browne ML, Druschel CM, & Olney RS (2009). Maternal caffeine consumption and risk of neural tube defects. Birth Defects Research Part A - Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 85(11), 879–889. 10.1002/bdra.20624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewell MJ, Chiu YE, & Drolet BA (2015). Neural tube dysraphism: Review of cutaneous markers and imaging. Pediatric Dermatology. 10.1111/pde.12485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GM, Quach T, Nelson V, Carmichael SL, Schaffer DM, Selvin S, & Yang W (2003). Neural tube defects associated with maternal periconceptional dietary intake of simple sugars and glycemic index. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78(5), 972–8. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14594784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GM, Velie EM, & Schaffer D (1996). Risk of neural tube defect-affected pregnancies among obese women. Journal of the American Medical Association, 275(14), 1093–1096. 10.1001/jama.275.14.1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw GM, Velie EM, & Wasserman CR (1997). Risk for neural tube defect-affected pregnancies among women of Mexican descent and White women in California. American Journal of Public Health, 87(9), 1467–1471. 10.2105/AJPH.87.9.1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithells RW, Sheppard S, & Schorah CJ (1976). Vitamin deficiencies and neural tube defects. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 51(12), 944–50. 10.1136/adc.51.12.944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithells RW, Sheppard S, Schorah CJ, Seller MJ, Nevin NC, Harris R, … Fielding DW (1980). POSSIBLE PREVENTION OF NEURAL-TUBE DEFECTS BY PERICONCEPTIONAL VITAMIN SUPPLEMENTATION. The Lancet, 315(8164), 339–340. 10.1016/S0140-6736(80)90886-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumpf DA, & Anencephaly T medical T. F. on. (1990). The infant with anencephaly. New England Journal of Medicine, 322(10), 669–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez L, Felkner M, & Hendricks K (2004). The effect of fever, febrile illnesses, and heat exposures on the risk of neural tube defects in a Texas-Mexico border population. Birth Defects Research Part A - Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 70(10), 815–819. 10.1002/bdra.20077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez L, Hendricks K, Felkner M, & Gunter E (2003). Maternal serum B12 levels and risk for neural tube defects in a Texas-Mexico border population. Annals of Epidemiology, 13(2), 81–8. 10.1016/S1047-2797(02)00267-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DNP (2009). Postnatal management and outcome for neural tube defects including spina bifida and encephalocoeles. Prenatal Diagnosis. 10.1002/pd.2199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Greenebaum E, & Monteagudo A (1996). Exencephaly-anencephaly sequence: Proof by ultrasound imaging and amniotic fluid cytology. Journal of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, 5(4), 182–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velie EM, Block G, Shaw GM, Samuels SJ, Schaffer DM, & Kulldorff M (1999). Maternal supplemental and dietary zinc intake and the occurrence of neural tube defects in California. American Journal of Epidemiology, 150(6), 605–616. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller DK, Hashmi SS, Hoyt AT, Duong HT, Tinker SC, Gallaway MS, … Canfield MA (2017). Maternal report of fever from cold or flu during early pregnancy and the risk for noncardiac birth defects, National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997–2011. Birth Defects Research. 10.1002/bdr2.1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallingford JB (2005). Neural tube closure and neural tube defects: Studies in animal models reveal known knowns and known unknowns. In American Journal of Medical Genetics - Seminars in Medical Genetics (Vol. 135 C, pp. 59–68). 10.1002/ajmg.c.30054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallingford1 JB, Niswander LA, Shaw GM, & Finnell RH (2013). The Continuing Challenge of Understanding, Preventing, and Treating Neural Tube Defects. Science, 339, 1048–1054. 10.1038/nrn1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werler MM, Louik C, Shapiro S, & Mitchell AA (1996). Prepregnant weight in relation to risk of neural tube defects. Journal of the American Medical Association, 275(14), 1089–1092. 10.1001/jama.275.14.1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins-Haug L, & Freedman W (1991). Progression of exencephaly to anencephaly in the human fetus--an ultrasound perspective. Prenatal Diagnosis, 11(4), 227–233. 10.1002/pd.1970110404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdy MM, Mitchell AA, Liu S, & Werler MM (2011). Maternal dietary glycaemic intake during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 25(4), 340–346. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01198.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim E, Zhang Z, Uz T, Chen CQ, Manev R, & Manev H (2003). Valproate administration to mice increases histone acetylation and 5-lipoxygenase content in the hippocampus. Neuroscience Letters, 345(2), 141–143. 10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00490-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]