Abstract

Despite impressively initial clinical responses, the majority of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients treated with sorafenib eventually develop resistance to this drug. It is well-known that microRNA (miRNA) plays a critical role in HCC progression and sorafenib resistance. However, the potential mechanism by which miRNA contributes to the human HCC cells to sorafenib resistance is still unknown. Herein, we identify miR-374b/hnRNPA1/PKM2 axis serving as an important mechanism for acquired sorafenib resistance of HCC cells. By establishing a sorafenib-resistant HCC model, we demonstrated that miR-374b reduces the expression of hnRNPA1 by binding to its 3’ untranslated region, which subsequently decreases levels of PKM2. The suppression of PKM2 by miR-374b re-sensitizes sorafenib-resistant HCC cells and mouse xenografts to sorafenib treatment by antagonizing glycolysis pathway. Clinically, hnRNPA1 and PKM2 expression are upregulated and inversely associated with miR-374b expression level in sorafenib-resistant HCC patients. Moreover, sorafenib significantly induces the expression of hnRNPA1, which serves as an important mechanism for the acquired sorafenib resistance in HCCs. Thus, our data suggest that targeting the alternative splicing of the PKM by miR-374b overexpression may have significant implications in overcoming the resistance to sorafenib therapy.

Keywords: MiR-374b, sorafenib, PKM2, hepatocellular carcinoma, hnRNPA1

Introduction

Sorafenib is an oral multikinase inhibitor initially demonstrated to target wild-type BRAF, V599E mutant BRAF, Raf-1, VEGFR-2/3, PDGFR-β, Flt3, and c-KIT, thereby inhibiting angiogenesis and tumor cell proliferation [1]. Studies have also reported that sorafenib can also target the RAF independent signaling pathways, such as apoptotic and cell cycle-related pathways [2]. Although sorafenib has been established as an excellent treatment tool for advanced stages of hepatocellular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, and thyroid cancer [3], it is well-known that the individual patient response towards sorafenib is drastically different [4]. Therefore, the number of HCC patients with complete response to sorafenib is very low [5]. The explanations for these different responses may include epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), genetic heterogeneity of HCC patients, tumor stem cells, switching to compensatory pathways, hindering pro-apoptotic signals, and tumor microenvironment [6,7]. Considering the emerging sorafenib resistance crisis in HCC, future studies are urgently needed to drug resistance. Noncoding RNA (ncRNA) has recently emerged as a significant regulator in signaling pathways involved in HCC drug resistance [8], therefore pharmacologically targeting these ncRNAs might be a novel and promising stratagem to reverse drug resistance.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of short, highly conserved endogenous noncoding RNAs (18-22 nucleotides) and implicated in the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expressions by binding to the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) of target messenger RNA [9]. Substantial facts and evidence are looming that particular miRNA alterations are associated with HCC initiation, progression, and recurrence [10]. Furthermore, miRNAs have been indicated to be promising and emerging target to tackle mechanisms of chemoresistance in different cancers [6]. Recently, altered expression of specific miRNAs is linked to the development of anticancer drug resistance [11]. Additionally, miRNAs can be used to sensitize tumors to chemotherapy [12]. Therefore, exploiting the therapeutic potential of miRNAs for overcoming anticancer drug resistance is of prime importance in various cancers. However, miRNAs as sorafenib response biomarkers, the mechanistic aspect, and therapeutic potential of miRNAs for sorafenib response in HCC are still not clear.

The critical goal of the present study was to understand sorafenib resistance in HCC cells and to uncover multiple targets that may overcome this problem. Herein, we identified a novel cancer-related regulator, miR-374b. We further indicated that miR-374b inhibits the expression of hnRNPA1 and PKM2, and re-sensitizes sorafenib-resistant HCC cells to sorafenib treatment by antagonizing glycolysis pathway. The current findings underline the significance of developing modulators of this pathway to combat sorafenib resistance in HCC.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transient transfection

HEK293T and human HCC cell lines (Hep3B, HepG2, and HCCLM3) were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells are sorafenib-resistant clones developed as previously described [13]. Briefly, the parental Hep3B and HCCLM3 cells were exposed to increasing sorafenib concentrations, and the surviving resistant Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells were cultured in DMEM containing 5 mM glucose supplemented with sodium pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and L-glutamine. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used for transient transfection according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Control siRNA and siPKM2 were purchased from Santa Cruz.

Western blotting

Briefly, lysates from cultured cells or tissues were prepared in modified RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1% Triton, 0.5% deoxycholate) plus 25 μg ml-1 leupeptin, 10 μg ml-1 aprotinin, 2 mM EDTA and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. The protein concentrations were determined by using a BCA Protein Assay Reagent kit (Pierce Biotechnology, USA). The protein extracts were then separated through SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore). The membranes were incubated with indicated primary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Then PVDF membranes were washed with TBST buffer (0.1%) before incubation with indicated secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 hour. Finally, the target proteins were assayed using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate reaction kit (Thermo Scientific) based on the manufacturer’s instructions. And the quantification of bands intensities was performed.

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake

Indicated cells were cultured in 12-well plates, then detached, and subsequently incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in 500 μl of DMEM with 4 μCi/mL of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG). Pellets were collected and washed twice with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline. Then cell lysates were collected with 500 μl of 0.1 M NaOH. Finally, the radioactivity of the cell lysates was measured with a well γ-counter. The readouts were normalized based on the corresponding protein amounts.

Lactate production, glucose uptake, ATP production, and oxygen consumption rate analysis

According to the manufacturer’s instruction, we measured the extracellular lactate with Lactate Colorimetric Assay Kit (Sigma). The levels of ATP were analyzed using an ATP Colorimetric/Fluorometric Assay Kit (Sigma). Briefly, 2×105 indicated cells were cultured in a 24-well plate. Then the cells were washed, centrifuged, and lysed after 24 hours. Indicated cells were cultured in 12-well plates, then detached, and subsequently incubated with 4 μCi/mL of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) in 500 μl of DMEM for 1 hour at 37°C. Then pellets were washed with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) twice and collected with 500 μl of 0.1 M NaOH. Finally, a well γ-counter was used to measure the radioactivity of the samples. Based on the matched protein amounts, the readouts were normalized. All assays were performed in triplicates. Intracellular glucose uptake was monitored with Glucose Colorimetric/Fluorometric Assay Kit. (Sigma). Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was assayed through the Seahorse XF24 analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). Briefly, indicated cells were plated in a 24-well plate overnight. 30 min before the analysis, the medium was removed and the Seahorse assay medium containing 2 mM L-glutamine or 5 mM glucose was added. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, OCR was carried out.

Clonogenic assay

Briefly, 750 HCC cells were plated on a 24-well plate. 24 h later, HCC cells were transfected with control miRNA or anti-miR-374b. Another 2 weeks later, HCC cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained with crystal violet. The colonies were counted and all experiment was repeated at least three times.

Tumor xenograft study

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Anhui Province Hospital approved all these procedures of this project. Briefly, indicated HCC cells (2×106 cells per mice in 3 μl total) with or without miR-374b overexpression. Then these cells were injected into five-week-old male SCID mice (n = 6 per group). After eight days, an IVIS Lumina Imaging System (Xenogen) was used to measure the tumors by bioluminescence.

RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation

The Magna RNA-binding Protein Immunoprecipitation (RIP) Kit (Millipore) was used to perform RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation with an anti-AGO2 antibody (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, qRT-PCR was used to analyze the precipitated RNAs.

The luciferase reporter assays

http://www.microrna.org (miRanda algorithm) was used to predict the putative miRNA binding sites on the hnRNPA1 3’-UTR. The pGL3 Luciferase Reporter Vectors for the 3’-UTR region of hnRNPA1 were purchased from Promega. HEK239T cells and lipofectamine 2000 reagent were used to transfect a miR-374b mimic or a scrambled control (100 nM; Ambion) along with WT-HnRNPA1 or its MUT 3’-UTR reporter and Renilla luciferase vector control vector (phRL-TK). 24 h after transfection, a microplate luminometer was used to moniter the luciferase activity with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System Kit (Sigma). Against the phRL-TK control, luciferase activity was normalized. The data obtained were further normalized against the scrambled control.

CCK-8 assay

The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Sigma) was used to examine the cell survival rate. Cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 5000 cells per well. 24 hours later, DMEM containing 10% FBS and drugs were used at the indicated concentrations. After 24 h culture, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well. And the cells were further cultured for 2 hours. Absorbance was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader. To calculate IC50, the indicated cells were cultured with increasing sorafenib concentrations. The IC50 value was assayed with the GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software.

Quantitative real-time (RT)-PCR

The RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) was used to isolate total RNA. Then cDNA from 1 mg of RNA was synthesized by using a Verso cDNA Kit (Thermo Scientific). Indicated mRNA levels were measured by using a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). For miRNA quantification, total RNA was isolated using a mirVana miRNA isolation kit (Ambion, USA) per the manufacturer’s instructions. For quantification of pri-miRNA and mature miRNA, Taqman miRNA assays (Life Technologies) were used and real-time PCR was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primer sequences used for qRT-PCR were as follows: miR-374b (forward, 5’-TCAGCGGATATAATACAACCTGC-3’ and reverse, 5’-TATCGTTGTTCTCCACTCCTTCAC-3’); PKM1 (forward, 5’-GCCTCCAGTCACTCCACAGA-3’ and reverse, 5’-CAGCACGGCATCCTTACACA; PKM2 (forward, 5’-CAGCACCT GATTGCCCGAGA-3’ and reverse-3’ and reverse, 5’-CCAGACTTGGTGAGCACGATA-3’); HIF-1a (forward, 5’-TGCTCATCAGTTGCCACTTC-3’ and reverse, 5’-TCCTCACACGCAAATAGCTG-3’); hnRNPA1 (forward, 5’-GCCCAGTCCATCACAATCAC-3’; and reverse, 5’-GATGCTGGCCGAGTAGGAG-3’); RNU6B (forward, 5’-ATTGGAACGATACAGAGAAGATT-3’ and reverse, 5’-GGAACGCTTCACGAATTTG-3’; GAPDH (forward, 5’-GAAATCCCATCACCATCTTCCAGG-3’ and reverse, 5’-GAGCCCCAGCCTTCTCCATG-3’). RNU6B (for mature miRNAs) served as the internal control for miR-374b expression, and GAPDH served as the internal control for mRNA expression. Relative expression was analyzed using the 2-∆∆Ct method.

HCC patient samples

All HCC samples enrolled in this study were collected from patients undergoing HCC resection from January 2008 to May 2014 at the Anhui province Hospital. The diagnosis of HCC was based upon the criteria of World Health Organization. The clinical typing of liver cancers was determined according to the International Union against Cancer tumor-node-metastasis classification system. The Edmondson grading system was used to determine the tumor differentiation. HCC patients are divided into several groups. To perform this classification, the expression of miR-374b in clinical samples was detected by real-time RT-PCR, and the mean value of miR-374b expression was calculated. The samples that had miR-374b expression equal to or greater than mean value were divided into high miR-374b expression group. The samples that had miR-374b expression lower than mean value were divided into low miR-374b expression group. The levels of PKM2, and hnRNPA1 is considered only in the cancer part but not in the matched non-cancer tissue. Also, the expression of PKM2, and hnRNPA1 are quantified at the protein level using immunohistochemistry. Ethical approval for using human samples was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Anhui province Hospital with the informed consent of patients.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by using Prism Software (GraphPad). The data from experiments are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) which rests from at least three independent experiments. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate the OS rates with the log-rank test for comparison. The correlations between various protein expressions level was calculated using Spearman’s rank assay. The Fisher’s exact test, X2 test, or Student’s t-test was used for comparisons between groups. The asterisks P < 0.05 (*) indicates that two-sided p-value is statistically significant along with P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), and P < 0.01 (***).

Results

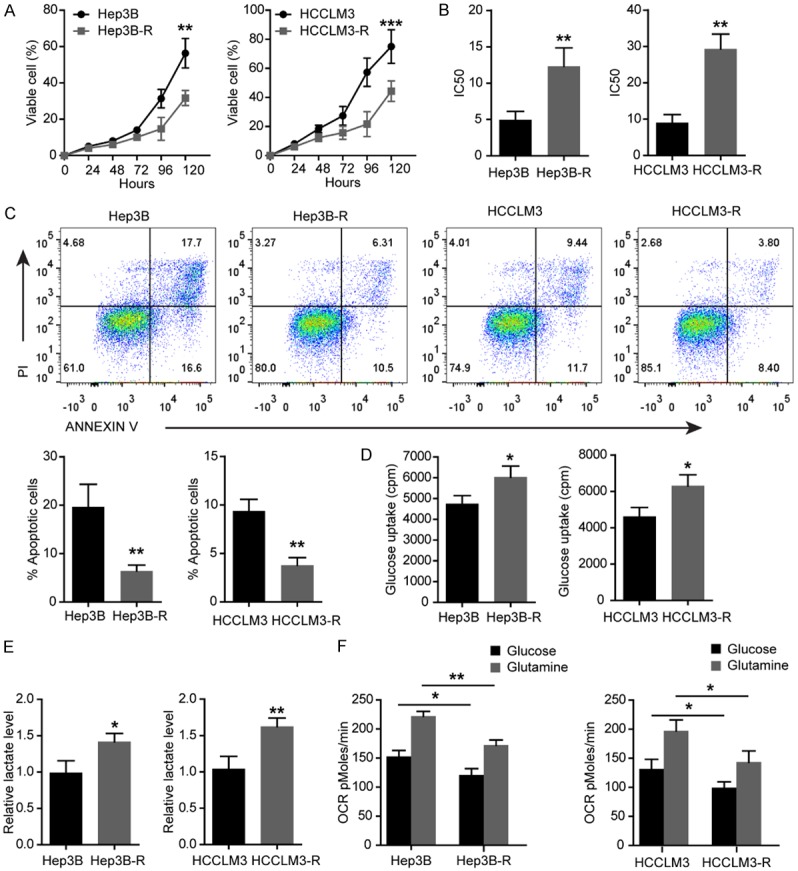

Sorafenib-resistant Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells have elevated glycolysis and decreased apoptosis compared with their parental cell lines

To study the sorafenib-resistant mechanisms of HCC cells, we firstly treated Hep3B and HCCLM3 cells with increasing concentrations of sorafenib in culture medium for screening sorafenib-resistant HCC cells. After 6 months, two resistant cell clones (Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R) were obtained from their parental cell lines and then were used for subsequent experiments.

As shown in Figure 1A, Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells displayed a decreased growth rate compared with Hep3B and HCCLM3 parental cell lines. To confirm the resistance to sorafenib, the CCK8 assay was performed. Interestingly, the IC50 of sorafenib was 13.33 ± 1.45 nM in Hep3B-R cells and 4.97 ± 0.66 nM in Hep3B cells whereas the IC50 of sorafenib in HCCLM3-R cells was 29.33 ± 2.33 nM and 8.78 ± 1.29 nM in HCCLM3 cells (Figure 1B). To compare the survival capacity of Hep3B-R and Hep3B cells, the number of apoptotic cells was measured by flow cytometry. Hep3B-R cells displayed a decreased apoptosis compared with Hep3B cells as incubated 24 h with 10 nM Sorafenib (Figure 1C), so as HCCLM3-R cells.

Figure 1.

Elevated glycolysis and decreased apoptosis in sorafenib-resistant Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells. A. The viability of Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells determined by CCK8 assays compared with their parental cell lines. B. Comparing IC50 for sorafenib in indicated HCC cells after sorafenib treatment for 48 h. C. Comparing apoptosis in indicated HCC cells treated with 10 nM sorafenib for 48 h and its representation in bar format. D. Analysis of glucose uptake in Hep3B and Hep3B-R cells. E. Lactate production rate detected in indicated HCC cells. F. OCR in indicated HCC cells using glucose or glutamine as the carbon source. n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were calculated with student’s t-test.

Since glycolysis promotes the chemoresistance [14], we assessed the glycolysis and mitochondrial function in Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells and their parental cell lines. It was observed that both Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells showed a significant increase in glucose uptake (Figure 1D) and lactate production (Figure 1E) compared with Hep3B and HCCLM3 cells respectively. To examine the mitochondrial function, the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured using glucose or glutamine as the carbon source. As shown in Figure 1F, Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells showed a significantly reduced oxidative ability when glucose or glutamine was used as a carbon source.

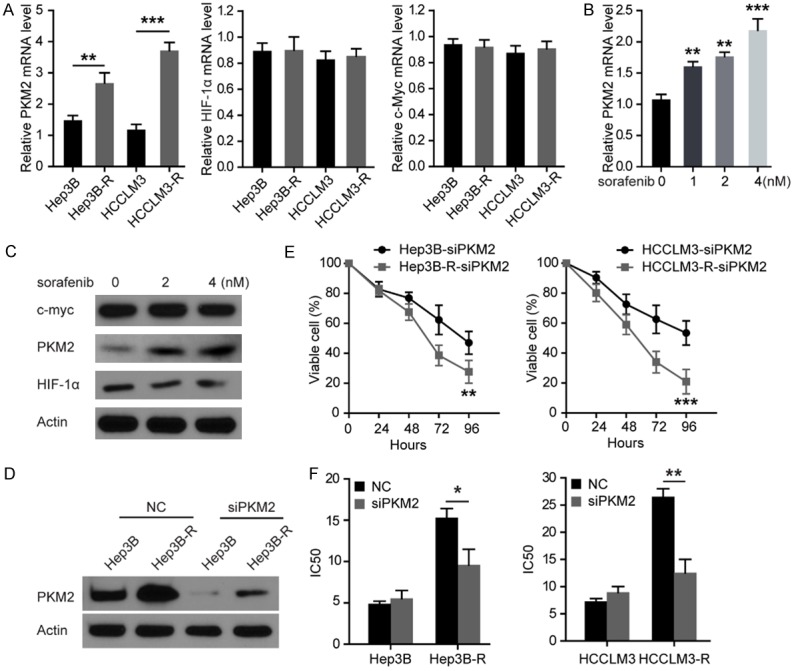

Silencing PKM2 restores Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells’ sensitivity to sorafenib

The above results suggest that the sorafenib resistance in Hep3B and HCCLM3 cells might be associated with suppressed oxidative phosphorylation and increased glycolysis. As HIF-1a, myc and PKM2 are the most important regulators of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation [10], their expression levels were examined in these HCC cells treated with sorafenib for 48 h. It was found that PKM2, not HIF1α and myc mRNA and protein levels were markedly increased in Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells compared to Hep3B and HCCLM3 cells (Figure 2A-C). In addition, sorafenib increased PKM2 not HIF1a and myc protein expression in a dose-dependent manner in Hep3B cells (Figure 2B and 2C), and overexpression of PKM2 reduces Hep3B and HCCLM3 cells’ sensitivity to sorafenib (Figure S1). These results suggest that PKM2 plays an important role in sorafenib resistance in HCC cells. As the expression of PKM2 was increased in Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells, we hypothesized that the down-regulation of PKM2 by siRNA might re-sensitize Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells to sorafenib. To this end, PKM2 was suppressed with siRNA in Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells (Figure 2D), and these cells were cultured with different concentrations of sorafenib. As shown in Figure 2E, cell survival rate was decreased in these HCC cells with suppressed PKM2. Moreover, silencing PKM2 significantly inhibited survival rate of Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells more than their parental cells respectively. Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells also showed increased sensitivity to sorafenib compared to their parental cells (Figure 2F). These results indicate that sorafenib resistance is associated with increased PKM2 expression and that knockdown of PKM2 may re-sensitize Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells to sorafenib.

Figure 2.

Silencing PKM2 restores Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells’ sensitivity to sorafenib. A. Comparative analysis of mRNA levels of HIF-1α, myc and PKM2 in indicated HCC cells. B. The mRNA levels of PKM2 were detected by qRT-PCR under increasing concentrations of sorafenib in indicated HCC cells. C. Western blot performed with antibodies against HIF1a, myc, PKM2 and GAPDH on cell lysates from Hep3B cells treated with increasing concentrations of sorafenib for 48 h. D. Western blot performed with antibodies against PKM2 on cell lysates from indicated HCC cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (NC) or PKM2 siRNA. E. Cell survival rate determined by CCK8 assay after treatment of indicated HCC cells with PKM2 siRNA. F. IC50 for sorafenib in indicated HCC cells after treatment for 48 h with sorafenib. Inhibition of PKM2 restored Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cell sensitivity to sorafenib. n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were calculated with student’s t-test.

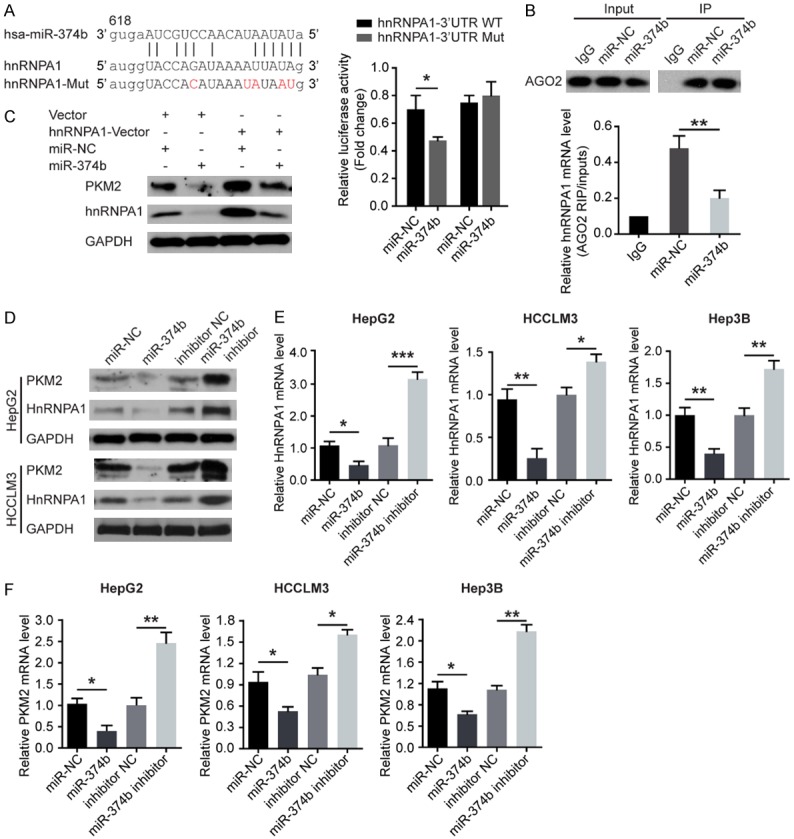

Mir-374b inhibits PKM2 expression by directly binding to hnRNPA1 in HCC cells

Earlier studies indicated that two isoforms PKM1 and PKM2 result from mutually exclusive alternative splicing of the PKM pre-mRNA [15], reflecting the inclusion of either exon 9 (PKM1) or exon 10 (PKM2). HnRNPA1 was shown to bind repressively to sequences flanking exon 9, resulting in exon 10 inclusion and thus ensuring a high PKM2/PKM1 ratio [16]. Given that miRNA can regulate the mRNA and protein expression [9], we reasoned that PKM2 expression could be regulated by miRNAs via targeting hnRNPA1 and that sorafenib might downregulate this miRNA, thus leading to elevated PKM2 expression and sorafenib-resistance of HCC cells. To test this idea, we sought to identify the miRNAs that potentially downregulate hnRNPA1 expression. The target prediction programs such as miRanda, miRBase, and TargetScan were used to predict the possible miR-374b targeting hnRNPA1 [8]. Given that miR-374b is closely involved in cancer cell growth [17] and the 3’-UTR of hnRNPA1 contains a putative target sequence for miR-374b, thus we focused on miR-374b (Figure 3A). To confirm that hnRNPA1 was directly inhibited by miR-374b, we inserted the potential binding sites into a dual luciferase reporter vector (Figure 3A). It was found that miR-374b inhibited significantly the reporter activity of the wild-type (WT) hnRNPA1 3’-UTR but not the mutant 3’-UTR plasmids (Figure 3A), suggesting that miR-374b inhibited hnRNPA1 expression via binding to the 3’-UTR of hnRNPA1.

Figure 3.

MiR-374b inhibits PKM2 expression by directly binding to hnRNPA1 in HCC cells. A. Graphic of the seed sequence of miR-374b matched with the 3’-UTR of the hnRNPA1 gene, and the design of wild-type or mutant hnRNPA1 3’-UTRs containing reporter constructs. Luciferase reporter assays in HCC cells after co-transfection of cells with wild-type or mutant hnRNPA1 3’-UTR and miR-374b. B. AGO2 protein was immunoprecipitated from cell extracts with an AGO2 antibody, or IgG. And the amount of hnRNPA1 mRNA bound to AGO2 or IgG was assayed using qRT-PCR in the presence of miR-374b mimics or control. C. The effect of miR-374b overexpression on hnRNPA1 and PKM2 protein expression after cells were transfected with the hnRNPA1 plasmid or empty vector. D. Western blot of hnRNPA1 and PKM2 expression 48 hours after cells were transfected with miR-374b or with anti-miR-374b. E. qRT-PCR of hnRNPA1 mRNA expression 48 hours after transfection. F. qRT-PCR of PKM2 mRNA expression 48 hours after transfection. n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were calculated with student’s t-test.

Next, we examined the possible interaction between hnRNPA1 and miR-374b using RIP assays. It was observed that hnRNPA1 mRNA formed a complex with AGO2 (Figure 3B, up-panel). Furthermore, once HCC cells were treated with miR-374b mimics, the levels of HnRNPA1 mRNA in AGO2 complexes significantly increased, indicating that the effect of miR-374b on the hnRNPA1 expression might be through the RISC (Figure 3B, low-panel).

Therefore, we examined the expression of hnRNPA1 mRNA and protein in miR-374b-overexpressing or miR-374b-silencing HCC cells, respectively. As expected, the overexpression of miR-374b significantly reduced the levels of the endogenous hnRNPA1 mRNA and protein, while anti-miR-374b has the opposite effects in HCC cells (Figure 3C-E). Furthermore, miR-374b overexpression inhibited the endogenous expression of PKM2 protein, whereas anti-miR-374b has the opposite effects in HCC cells (Figure 3C-E). And the expression of miR-374b indeed inversely affect the mRNA levels of PKM2 (Figure 3F). These results revealed that miR-374b inhibits PKM2 expression by directly binding to hnRNPA1 in HCC cells.

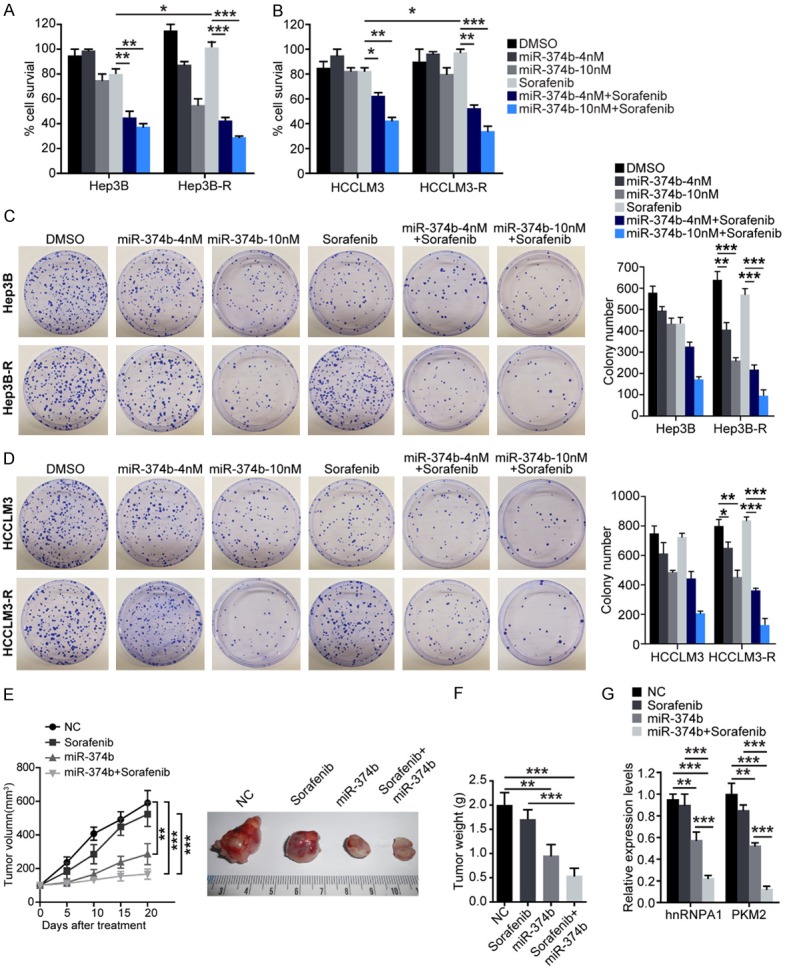

Mir-374b overexpression re-sensitizes sorafenib-resistant HCC cells to sorafenib treatment

Based on the results that miR-374b suppresses PKM2 levels, we analyzed whether it can re-sensitize sorafenib-resistant HCC cells to sorafenib. We treated Hep3B and Hep3B-R or HCCLM3 and HCCLM3-R cells with miR-374b and sorafenib either singly or in combination for two days and analyzed cell survival. As shown in Figure 4A, treatment with miR-374b overexpression or sorafenib alone suppressed the survival of both Hep3B and Hep3B-R cells slightly, while the combination of miR-374b with sorafenib significantly suppressed HCC cell survival in both of cells. Similar results were obtained with the HCCLM3 cells (Figure 4B). Moreover the apoptotic cell percentage increased slightly after miR-347b-overexpressing in Hep3B and HCCLM3 cells, but more severely in Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells (Figure S2), indicating that miR-374b re-sensitizes sorafenib-resistant cells to sorafenib treatment.

Figure 4.

Combination treatment with miR-374b and sorafenib re-sensitizes resistant HCC cells to sorafenib treatment in vitro and in vivo. Hep3B and Hep3B-R (A) and HCCLM3 and HCCLM3-R (B) cells were treated with 4 or 10 nM miR-374b and 20 nM sorafenib either singly or in combination and cell survival was analyzed. Hep3B and Hep3B-R (C) and HCCLM3 and HCCLM3-R (D) cells were treated with 4 or 10 nM miR-374b and 20 nM sorafenib either singly or in combination for 24 h and the clonogenic ability of the surviving cells was analyzed. Right panels show quantification of the numbers of colonies formed by cells in the respective treatment groups. (E) 2×106 Hep3B-R were injected sub-cutaneously into both flanks of SCID mice, and tumor growth was monitored. And the mice were randomly divided into 4 groups (n = 6/group) and treated with: 1) vehicle, 2) 25 mg/kg sorafenib via oral gavage daily for 5 days/week, 3) miR-374b transfection, and 4) a combination of miR-374b and sorafenib daily for 5 days/week. Tumors (n = 6/group) were monitored twice a week and were harvested and weighed at the end of 3 weeks. Tumor volumes (E) and weights (F) of tumors treated with the combination of miR-374b and sorafenib were significantly decreased. (G) Total RNAs from the tissues were measured by qRT-PCR for the expression levels of hnRNPA1 and PKM2. n = 3 (except E); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. P values were calculated with student’s t-test.

Next, we analyzed whether treatment with the combination of miR-374b and sorafenib affects the anchorage-dependent clonogenic ability of sorafenib-resistant cells. As shown in Figure 4C and 4D, the results showed that miR-374b exerts a more significant suppressive effect on the clonogenic ability of sorafenib-resistant Hep3B-R cells compared to the parental Hep3B cells, which may be due to the ability of miR-374b to antagonize the generation of PKM2 by suppressing the expression of hnRNPA1 (Figure 4C). The clonogenic ability of sorafenib-resistant Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells (Figure 4D) was greatly reduced by treatment with a combination of miR-374b and sorafenib, indicating that miR-374b may re-sensitize sorafenib-resistant cells to sorafenib by downregulation of the levels of PKM2.

Then we performed mouse xenograft assays to assess the synergism between miR-374b and sorafenib in vivo. 2×106 Hep3B-R cells were injected sub-cutaneously into both flanks of SCIDmice, and tumor growth was monitored. When the tumors were palpable, the xenografts were treated with miR-374b and sorafenib either singly or in combination for 3 weeks, and tumor growth was monitored. As shown in Figure 4E and 4F, sorafenib did not have a significant effect on the growth of Hep3B-R xenografts, while miR-374b alone was able to suppress tumor growth. In addition, treatment with the combination of miR-374b and sorafenib abolished Hep3B-R tumors almost completely. qRT-PCR (Figure 4G) was performed to confirm the downregulation of hnRNPA1 and PKM2 mRNA levels in the tumor tissues. This result indicated that treatment with the combination of miR-374b and sorafenib significantly suppressed the proliferation of Hep3B-R xenografts significantly. Therefore, our findings collectively demonstrate that miR-374b may synergize with sorafenib and may re-sensitize sorafenib-resistant HCC cells to sorafenib treatment.

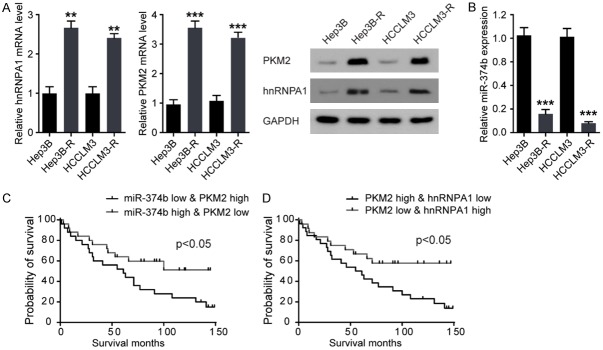

hnRNPA1 and PKM2 expression are upregulated and inversely associated with miR-374b level in in sorafenib-resistant HCC cells

To analyze the physiological relevance of miR-374b, hnRNPA1, and PKM2 expression in sorafenib-resistant HCC, we analyzed their protein levels in two sorafenib-sensitive (Hep3B and HCCLM3) and resistant pairs of HCC cell lines (Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R) (Figure 5A). It was found that the levels of hnRNPA1 and PKM2 were higher in Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R resistant cells than in their parental cells, while the expression of miR-374b was lower in Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R resistant cells than in their parental cells (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

HnRNPA1 and PKM2 expression are upregulated and inversely associated with miR-374b expression level in in sorafenib-resistant HCC cells and patients. A. HnRNPA1 and PKM2 mRNA expression were lower in sorafenib-sensitive parental HCC cell lines, compared with its resistant derivatives (left-panel). (Right-panel) HnRNPA1 and PKM2 protein levels were increased in sorafenib-resistant HCC cell lines. B. miR-374b expression levels were lower in sorafenib-resistant HCC cell lines than in sensitive cell lines. n = 3; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs their parental cell lines respectively. P values were calculated with student’s t-test. C and D. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients from the patients with HCC. OS (defined as the interval in months from the date of initial surgical resection to the date of death or last follow-up) for patients (Training and Validation sets) with high-grade serious HCC classified according to the expression of PKM2, miR-374b, and hnRNPA1. P values were calculated with Log-rank (Mantel-cox) test.

We then investigated the expression patterns of hnRNPA1, PKM2, and miR-374b in sorafenib-sensitive and resistant HCC patients and performed Kaplan-Meier survival analyses of the patients grouped by the levels of hnRNPA1, PKM2, and miR-374b in the tumor tissues. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients whose cancers expressed a low level of PKM2 and a high level of miR-374b uncovered a significantly longer overall survival (OS) than in those whose cancers expressed a high level of PKM2 and a low level of miR-374b (Figure 5C). A significantly longer OS was observed in patients with both low levels of hnRNAP1 and PKM2 than in those with high levels of hnRNAP1 and PKM2 (Figure 5D). These data proved the fact that regulation of hnRNPA1 by miR-374b controls the expression of PKM2 in sorafenib-resistant HCC patients.

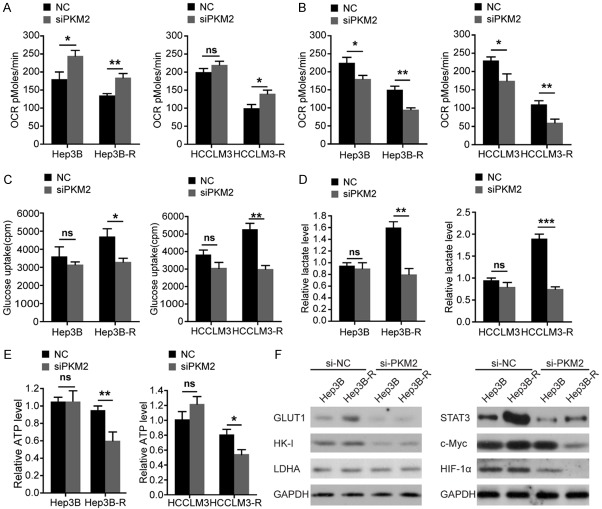

Overcoming the sorafenib resistance of Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells by PKM2 knockdown is attributed to glycolysis inhibition

Given that PKM2 has been shown to have other functions other than glycolysis, we further assessed whether suppression of PKM2 re-sensitizes Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells to sorafenib by blocking glycolysis. As shown in Figure 6A, when glucose was chosen as a carbon source, silencing PKM2 increased OCR in Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells compared with their parental cells. When glutamine was chosen as a carbon source, PKM2 siRNA inhibited glutamine oxidation more effectively in drug-resistant cells (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Overcoming the sorafenib resistance of Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells by PKM2 knockdown is attributed to glycolysis inhibition. A. OCR in indicated HCC cells treated by siPKM2 for 48 h using glucose as the carbon source. B. OCR in indicated HCC cells treated by siPKM2 for 48 h using glutamine as the carbon source. C. Glucose uptake in indicated HCC cells transfected with si-PKM2. The indicated cells were cultured in DMEM with 18F-FDG for 1 hour, and the radioactivity was examined by the well γ-counter. D. Lactate production rate determined in indicated HCC cells 48 h post-transfection with si-PKM2. E. Measurement of ATP levels in cells 48 h post-transfection with si-PKM2. F. Effects of si-PKM2 on the expression of GLUT1, HK-I, and LDHA 48 h post-transfection (left-panel). (Right-panel) Effects of si-PKM2 on the expression of c-Myc, STAT3, and HIF-1α 48 h post-transfection. n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ns: no significant difference. P values were calculated with student’s t-test.

Glucose uptake and lactate generation ability are the most important indicators of cell glycolytic activity. We found that knockdown of PKM2 significantly decreased glucose uptake and lactate production in Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells (Figure 6C and 6D). Then we examined the role of PKM2 knockdown in ATP generation. We observed that silencing PKM2 significantly reduced ATP production in HCCLM3-R and Hep3B-R cells. However, no effects were found on the ATP production in HCCLM3 and Hep3B cells (Figure 6E). Therefore, targeting PKM2 in HCCLM3-R and Hep3B-R cells by inhibited glycolysis can re-sensitize sorafenib-resistant cells.

Next, we analyzed the effect of silencing PKM2 on the expression of the glycolytic enzyme lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), HK-I, and glucose transporter1 (GLUT1) (Figure 6F). We found that silencing PKM2 significantly decreased the levels of GLUT1 and HK-I but not LDHA in Hep3B and Hep3B-R cells. The levels of HIF-1α, STAT3, and c-Myc, three major transcription factors which promoted GLUT1 expression, were also investigated. Interestingly, silencing PKM2 significantly inhibited the c-Myc expression compared to untreated control in Hep3B-R while it was not the case in Hep3B cells (Figure 6F). And this treatment also decreased the levels of HIF-1α and STAT3 in Hep3B and Hep3B-R cells (Figure 6F). Therefore, the glycolysis was inhibited more significantly in sorafenib-resistant HCC cells by silencing PKM2.

Discussion

Sorafenib resistance in HCC therapy represents an insidious barrier which demands further research. In this study, the role of miR-374b in acquired sorafenib resistance in HCC cells was investigated. In comparison to sorafenib-sensitive cells, miR-374b expression was decreased in sorafenib-resistant cells. Overexpression of miR-374b or silencing PKM2 or hnRNPA1 increased the sensitivity of sorafenib-resistant cells to sorafenib. Compared to sorafenib-sensitive cells, Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells displayed higher sensitivity to miR-374b or PKM2 glycolysis inhibitor. Besides, treating cells with the combination of sorafenib and miR-374b exhibited an increased inhibitory effect on Hep3B-R and HCCLM3-R cells when compared to single-agent therapy. New mechanisms predicted by our model suggest that combined use of miR-374b or hnRNPA1 or PKM2 inhibitor may overcome sorafenib resistance in HCC via regulating the glycolysis pathways.

Although deregulated miRNA profile has been reported in many literatures on sorafenib-resistance, target genes of these deregulated miRNAs remain unknown and need to be identified. Therefore, further study to interrelate miRNAs, genes, and sorafenib was definitely necessary. Vaira et al. reported the elevated level of miR-17-92 cluster members in HCC patients could limit the anticancer efficacy of sorafenib and that targeting these miRNAs could restore the sensitivity of HCC cells to sorafenib [18]. In addition, expression of ERK, MCL1, PI3K, P38MAPK, STAT3, WIP1, JAK-2, AKT, E2F1, which belong to the EGFR/IL-6 pathway members, have reported previously to be critical in mediating sorafenib-resistance [18]. And all of them are the targets of miR-17-92 cluster. On the contrary, current study indicated that a lower expression of miR-374b could limit the anticancer efficacy of sorafenib in HCC patients by promoting glycolysis. This novel finding has important translational significance in HCC treatment because our goal was aimed to determine synergistic effect of miR-374b mimics or hnRNPA1 or PKM2 inhibitor on sorafenib-resistant HCC cells. Consistent with our findings, it has become a practical option for modulating various human pathologies by using miRNA-based drugs either as mimics or inhibitors to target miRNA function.

The mechanisms underlying the regulation of the RNA-binding protein hnRNPA1 expression and its role in cancer progression are not well understood. It has been suggested that miRNAs and RNA-binding proteins interplay under several physiological conditions or in response to external stimuli [19]. For example, the Drosha-mediated processing of miR-18a required hnRNPA1 [19]. Also, hnRNPA1 blocks the binding of KSRP to let-7a and promotes let-7a biogenesis [20]. In turn, miRNA can regulate the expression of hnRNPA1 [21]. Therefore, we hypothesize that a circuit of miRNAs’ regulation might exist between oncogenic and tumor-suppressor miRNAs, which might be under the direct control of hnRNPA1 expression. Supporting this idea, we currently demonstrated the interactions of miR-374b and hnRNPA1 and their relevance for PKM2-mediated glycolysis in sorafenib-resistant ovarian HCC. However, we still do not know whether hnRNPA1 affects the expression of miR-374b in HCC. Further study is required to elucidate this possible feedback mechanism. We believe that to fully elucidate this complicated mechanism will demonstrate the importance of miRNA-hnRNPA1 circuits’ regulation and evaluate their roles as therapeutics target.

High levels of PKM2 in tumor or cancer-initiating cells are attributed to the switch of PKM gene splicing from PKM1 to PKM2, which promotes aerobic glycolysis and tumor formation [22]. The PKM1/M2 splicing switch is affected by many factors, such as c-Myc and hnRNPA1 [23]. However, the mechanism underlying the PKM1 switch to PKM2 in sorafenib-resistant HCC cells is not studied well. Previous studies also have indicated that the Warburg effect contributes to drug resistance of cancer cells [14]. However, the molecular mechanisms remain largely unclear. Our results not only support the notion above but also for the first time demonstrate that miR-374b downregulation potentially affects PKM1/PKM2 splicing by modifying hnRNPA1 expression in sorafenib-resistant HCC cells. We also indicate that the sorafenib-resistance of HCC cells is associated with increased glycolysis. Therefore, miR-374b is a potentially therapeutic target for HCC treatment. Given that the effects of PKM2 on HCC progression could be modulated in multiple ways, it will be necessary to fully elucidate these mechanisms in future studies.

In summary, the present study shows that miR-374b/hnRNPA1/PKM2 axis functions as an important mechanism in sorafenib resistance, with sorafenib-induced miR-374b downregulation and subsequently elevated glycolysis. Therefore, although our understanding of the mechanisms about sorafenib-resistance so far remains incomplete, this novel finding uncovers a valuable information for developing targeted therapies for sorafenib-resistance and highlight the importance of this axis in sorafenib resistance. We believe that further investigation of the crosstalk between miRNAs and their associated pathways will lead to the important breakthroughs in HCC therapy and further enhance our understanding of the mechanisms on sorafenib-resistance.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Zunyi Medical University Grant and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 31371512).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Lee J, Lee JH, Yoon H, Lee HJ, Jeon H, Nam J. Extraordinary radiation super-sensitivity accompanying with sorafenib combination therapy: what lies beneath? Radiat Oncol J. 2017;35:185–188. doi: 10.3857/roj.2017.00262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowolik CM, Lin M, Xie J, Overman LE, Horne DA. NT1721, a novel epidithiodiketopiperazine, exhibits potent in vitro and in vivo efficacy against acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2016;7:86186. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rimassa L, Abbadessa G, Personeni N, Porta C, Borbath I, Daniele B, Salvagni S, Van Laethem JL, Van Vlierberghe H, Trojan J. Tumor and circulating biomarkers in patients with second-line hepatocellular carcinoma from the randomized phase II study with tivantinib. Oncotarget. 2016;7:72622. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riedel M, Struve N, Müller-Goebel J, Köcher S, Petersen C, Dikomey E, Rothkamm K, Kriegs M. Sorafenib inhibits cell growth but fails to enhance radio-and chemosensitivity of glioblastoma cell lines. Oncotarget. 2016;7:61988. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardini AC, Santini D, Aprile G, Silvestris N, Felli E, Foschi FG, Ercolani G, Marisi G, Valgiusti M, Passardi A. Antiangiogenic agents after first line and sorafenib plus chemoembolization: a systematic review. Oncotarget. 2017;8:66699. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong X, Song R, Song H, Zheng T, Wang J, Liang Y, Qi S, Lu Z, Song X, Jiang H. PTEN antagonises Tcl1/hnRNPK-mediated G6PD pre-mRNA splicing which contributes to hepatocarcinogenesis. Gut. 2014;63:1635–1647. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qu C, He , Lu X, Dong L, Zhu Y, Zhao Q, Jiang X, Chang P, Jiang X, Wang L, Zhang Y, Bi L, He J, Peng Y, Su J, Zhang H, Huang H, Li Y, Zhou S, Qu Y, Zhao Y, Zhang Z. Salt-inducible Kinase (SIK1) regulates HCC progression and WNT/β-catenin activation. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1076–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He D, Huang C, Zhou Q, Liu D, Xiong L, Xiang H, Ma G, Zhang Z. HnRNPK/miR-223/FBXW7 feedback cascade promotes pancreatic cancer cell growth and invasion. Oncotarget. 2017;8:20165. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He D, Miao H, Xu Y, Xiong L, Wang Y, Xiang H, Zhang H, Zhang Z. MiR-371-5p facilitates pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and decreases patient survival. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Guo X, Feng X, Wang T, Hu Z, Que X, Tian Q, Zhu T, Guo G, Huang W. MiRNA-543 promotes osteosarcoma cell proliferation and glycolysis by partially suppressing PRMT9 and stabilizing HIF-1α protein. Oncotarget. 2017;8:2342. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaibori M, Sakai K, Ishizaki M, Matsushima H, De Velasco MA, Matsui K, Iida H, Kitade H, Kwon AH, Nagano H. Increased FGF19 copy number is frequently detected in hepatocellular carcinoma with a complete response after sorafenib treatment. Oncotarget. 2016;7:49091. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soriano A, París-Coderch L, Jubierre L, Martínez A, Zhou X, Piskareva O, Bray I, Vidal I, Almazán-Moga A, Molist C. MicroRNA-497 impairs the growth of chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells by targeting cell cycle, survival and vascular permeability genes. Oncotarget. 2016;7:9271. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomonari T, Takeishi S, Taniguchi T, Tanaka T, Tanaka H, Fujimoto S, Kimura T, Okamoto K, Miyamoto H, Muguruma N. MRP3 as a novel resistance factor for sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:7207. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song R, Song H, Liang Y, Yin D, Zhang H, Zheng T, Wang J, Lu Z, Song X, Pei T. Reciprocal activation between ATPase inhibitory factor 1 and NF-κB drives hepatocellular carcinoma angiogenesis and metastasis. Hepatology. 2014;60:1659–1673. doi: 10.1002/hep.27312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang W, Lu Z. Nuclear PKM2 regulates the Warburg effect. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:3154–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.26182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen M, David CJ, Manley JL. Concentration-dependent control of pyruvate kinase M mutually exclusive splicing by hnRNP proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:346–54. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qu R, Hao S, Jin X, Shi G, Yu Q, Tong X, Guo D. MicroRNA-374b reduces the proliferation and invasion of colon cancer cells by regulation of LRH-1/Wnt signaling. Gene. 2018;642:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Awan FM, Naz A, Obaid A, Ikram A, Ali A, Ahmad J, Naveed AK, Janjua HA. MicroRNA pharmacogenomics based integrated model of miR-17-92 cluster in sorafenib resistant HCC cells reveals a strategy to forestall drug resistance. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11448. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11943-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michlewski G, Guil S, Cáceres JF. Regulation of microRNAs. Springer; 2010. Stimulation of pri-miR-18a processing by hnRNP A1; pp. 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michlewski G, Cáceres JF. Antagonistic role of hnRNP A1 and KSRP in the regulation of let-7a biogenesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1011–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez-Aguayo C, Monroig PDC, Redis RS, Bayraktar E, Almeida MI, Ivan C, Fuentes-Mattei E, Rashed MH, Chavez-Reyes A, Ozpolat B, Mitra R, Sood AK, Calin GA, Lopez-Berestein G. Regulation of hnRNPA1 by microRNAs controls the miR-18a-K-RAS axis in chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer. Cell Discov. 2017;3:17029. doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2017.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen M, Zhang J, Manley JL. Turning on a fuel switch of cancer: hnRNP proteins regulate alternative splicing of pyruvate kinase mRNA. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8977–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.David CJ, Chen M, Assanah M, Canoll P, Manley JL. HnRNP proteins controlled by c-Myc deregulate pyruvate kinase mRNA splicing in cancer. Nature. 2010;463:364. doi: 10.1038/nature08697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.