Abstract

Background: Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) promote immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment, support tumor growth and survival, and may contribute to immunotherapy resistance. Recent studies showed that tumor-derived exosomes (TDEs) can induce MDSCs accumulation and expansion, the mechanisms of which are largely unknown.

Methods: The morphologies and sizes of the exosomes was observed by using a JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope. MicroRNA(miR)-107 and ARG1, DICER1, PTEN, PI3K, AKT, mTOR, and NF-kB mRNAs were quantified by quantitative reverse tanscription PCR. Dual-Luciferase Reports Assay were used to examine the expression of genes which was targeted by miR-107. The expression of proteins were analyzed by using western blot.

Results: MiR-107 was not only overexpressed in gastric cancer cells but also enriched in their secreted TDEs. Also, these miR-107 enriched TDEs could be taken up by HLA-DR-CD33+MDSCs, where miR-107 was able to target and suppress expression of DICER1 and PTEN genes. Dampened DICER1 expression supported expansion of MDSCs , while decreased PTEN led to activation of the PI3K pathway, resulting in increased ARG1 expression. Furthemore, gastric cancer-derived miR-107 TDEs, when dosed intravenously into mice, were also capable of inducing expansion of CD11b+Gr1+/high MDSCs in mouse peripheral blood and altering expression of DICER1, PTEN, ARG1, and NOS2 in the MDSCs.

Conclusions: Our findings demonstrate for the first time that gastric cancer-secreted exosomes are able to deliver miR-107 to the host MDSCs where they induce their expansion and activition by targeting DICER1 and PTEN genes, thereby may provide novel cancer therapeutics target for gastric cancer.

Keywords: exosome, miRNA-107, myeloid-derived suppressor cell, arginase 1, gastric cancer

Background

Exosomes are membrane-bound extracellular vesicles secreted by all types of cells including tumor cells that can contain bioactive molecules such as proteins, lipids, mRNAs, and miRNAs.1 Being able to stably transfer their contents to distant sites, TDEs play a key role in the intercellular communication between cancer cells and host microenvironments to facilitate tumor growth, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, and immune suppression.2–6 TDEs found in neoplastic lesions or biologic fluids of cancer patients contain immunosuppressive molecules that can mediate immune escape via inhibition of immune cell activation, maturation, differentiation, as well as induction of immunosuppressing cells such as Treg and MDSCs.2,3,5,7–10

MDSCs are a heterogenous population of immature myeloid cells that expands and negatively regulates immune responses during cancer progression, inflammation, and infection.11 Since they lack the expression of lineage markers specific for B, T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, or macrophages, they were not originally classified and thus were called “null” cells.11–13 MDSCs promote tumor evasion by inhibiting T-cell response and inducing other immunosuppressive cells such as Tregs, mechanisms of which may involve depletion of essential amino acids from the tumor microenvironment required for T cell proliferation; alternatively, they may involve oxidative stress by generating NO and reactive oxygen species (ROS) that inhibit T cell recruitment; and finally, they may produce anti-inflammatory cytokines such as TGF-b and IL-10 amongst other immunosuppressive factors.11–14 Additionally, MDSCs can directly promote tumor proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis through non-immunological mechanisms.12,15,16

MicroRNAs are small non-coding RNAs of approximately 18–24 nucleotides in length in their mature form that is involved in post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. The physiological and pathological roles of miRNAs in immune system regulation have been widely studied.17 Particularly, multiple miRNAs have been implicated in the expansion, activation, and functional regulation of MDSCs in the tumor microenvironment.8,10,18,19 Nevertheless, the mechanisms by which tumors deliver miRNAs to MDSCs in the microenvironment, and the means by which these tumor-derived miRNAs modulate MDSCs growth and activity, are largely unknown. Previous studies showed that TDEs could be taken up by MDSCs and that molecular cargos delivered by TDEs were capable of promoting accumulation and activation of MDSCs, which consequently enhanced tumor progression.8,10 Whether MDSC-modulating miRNAs could be delivered via TDEs, and how these exogenous miRNAs regulate the expansion and function of MDSCs, remained to be determined.

In this study, we show that miR-107, one of the highly expressed miRNAs in gastric cancers,20,21 is able to be transferred from tumor cells to HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs via gastric cancer-secreted TDEs, where it targets DICER1 and PTEN genes to promote expansion and activity of MDSCs. Furthermore, miR-107-enriched TDEs, when given to mice intravenously, are able to induce accumulation of CD11b+Gr1+/highMDSCs in the peripheral blood. Together, these findings provide evidence of how tumor cells modulate the immunosuppressive microenvironment by secreting miRNA-enriched TDEs, and identify a novel mechanism by which tumor-derived miR-107 promotes MDSCs accumulation and activity, hence suggesting the targeting of tumor-derived miR-107 as an approach to block the cross-talk between cancer cells and host MDSCs to inhibit tumor growth and augment immunotherapy efficacy.

Methods

Animals, cell lines and reagents

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) guidelines with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Drug Safety Evaluation Center of the First Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Chinese Medicine (protocol number YFYDW2015013). BALB/c mice (~20 g, female) were provided by the Laboratory Animal Center of Zhengzhou University (License number: 41003100002475), and maintained under an SPF (Specific Pathogen Free) level of care. The human gastric cancer cell lines MGC-803, BGC-823, SGC-7901, and gastric epithelial cell line GES-1 were purchased from the Shanghai Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences, and cultured in RPMI-1640 complete medium (Solarbi Co., Beijing, China), containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone), 10 ng/mL rhGM-CSF (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). Human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T was purchased from Shanghai Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences, and cultured in DMEM complete medium containing 10% FBS (Solarbi Co.).

Exosome isolation and transmission electron microscopy

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all subjects gave written informed consent to participate. The Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Chinese Medicine approved the study (protocol number 2016HL-085). Serum was separated from the peripheral blood, aliquoted (150 μl/tube) and frozen at −80 °C. Exosomes (TDEs) were then isolated using the PureExo® Exosome Isolation kit for serum or plasma (101bio, california, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To obtain exosomes secreted by gastric cancer cells, human gastric cancer cell lines MGC-803, BGC-823 and SGC-7901 were serum-starved for 48 hrs, and the culture media were then collected for exosome extraction using the PureExo® Exosome Isolation kit for cell culture media (101bio).

To quality control the isolated exosomes, a JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope (TEM) (JEOL Inc., Peabody, MA, USA) was used to observe the morphologies and sizes of the exosomes. The exosomes were prepared using the Exosome Preparation kit for transmission electron microscopy (101bio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein contents of exosomes were analyzed by a BCA protein assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA). The exosomes were also labeled with CD9 and CD63 antibodies (Abgent, San Diego, CA, USA) and analyzed by western blot.

MDSCs isolation and culture

To obtain peripheral blood nucleated cells, FACS hemolysing solution (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) (diluted 1:10 with deionized water) was added into EDTA-treated human whole blood. The mixture was then incubated at room temperature for 10 min, centrifuged at 20 °C for 5 min, washed twice with PBS to remove red blood cells. To obtain HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs, PBMCs were washed with precooled autoMACS® Running Buffer (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), incubated with anti-HLA-DR microbeads, and HLA-DR− cells were separated on a autoMACS® separator using the Depletion program following manufacturer’s instructions. To separate the CD33+ population, HLA-DR− cells were co-incubated with CD33 microbeads, and HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs were collected using a Positive Selection program. Cell viability of sorted HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs was analyzed using trypan blue staining; the purity was then validated on a FACS Canto II flow cytometer using an APC-conjugated anti-CD33 antibody (BD Biosciences). Sorted HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs were maintained in vitro in RPMI-1640 complete medium supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 20 mM 2-ME, 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin/streptomycin, and 40 ng/ml hGM-CSF, at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs and exosome co-culture

HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs isolated from peripheral blood were co-cultured with exosomes extracted from the serum of gastric cancer patients, SGC-7901, or HEK293T cell culture media (5 μg exosomes for 1×105 cells). In a separate experiment, HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs were co-cultured with SGC-7901 cells (SGC-7901: MDSCs =1:4) for 3, 24, 48 and 96 hrs before being labeled with CFSE and analyzed on a BD FCSCantoTMII flow cytometer for cell proliferation. After 96 hrs of co-culture, HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs were also collected for mRNA and protein extraction for downstream applications.

Flow cytometry and antibodies

For flow cytometry a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer and FACSDivaTM analysis were used. The following antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences: anti-HLA-DR-PE-Cy7, anti-CD33-APC, anti-CD11b-APC-Cy7, anti-CD14-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD15-PE-Cy7 and anti-ARG-1-FITC; and their corresponding isotype negative control antibodies: mouse IgM-PE-Cy7, mouse IgG1-APC, rat IgG2b APC-Cy7, mouse IgG2a-PerCP-Cy5.5, and mouse IgM-PE-Cy7.

Detecting intracellular ARG1 in MDSCs subgroups by flow cytometry

Immune cells in peripheral blood were labeled with anti-HLA-DR-PE and anti-CD33-APC fluorescent antibody. The mixture was then centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 15 mins at 18 °C and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was then mixed with 100 μl of cytomembrane punching reagent 1 (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), which was mixed gently, and incubated for 15 mins without light at 25 °C. Cells were then washed with normal saline (NS) and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 mins. The supernatant was then discarded and the pellet mixed with 100 μl of cytomembrane punching reagent 2. This was incubated for 5 mins without light at 25 °C. Then, 5 μl of ARG1-FITC was added and incubated for 15 mins without light at 25 °C. Next, 1ml of was added and the mixture centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 mins. The supernatant was then discarded and the labelled cells resuspended in 500 μl of FCM buffer solution for detection.

Mature miRNA and pre-miRNA purification and real-time quantitative PCR

To extract miRNAs from cultured cells and serum, a NucleoSpin® miRNA column (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Duren, Germany) was used. To extract exosomal miRNAs and pre-miRNAs, a SeraMir Exosome RNA purification kit (Systems Biology Institute, Tokyo, Japan) was used following manufacturer’s instructions. miRNA real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed using miRACLE PCR Primers and a miRACLE RT-qPCR Detection Kit (both from Genetimes Technology Inc., Shanghai, People's Republic of China). For ARG1, DICER1, PTEN, PI3K, AKT, mTOR, and NF-kB mRNAs, the SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Japan) was used instead. Primers for detecting all mRNAs are included in Table S1. All qPCR reactions were run on an ABI 7,500 system (Applied Biosystems, California, USA), and analyzed using the 2−△△Ct method.

Table S1.

The primers for detecting all the mRNAs

| Genes | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| ARG1 | Forward ACTTAAAGAACAAGAGTGTGATGTG Reverse GTCCACGTCTCTCAAGCCAA |

| Dicer1 | Forward GAACGCTTTTGTGCTGCTGA Reverse CACAGGGCTCTAAAGTGGGG |

| PTEN | Forward TTTGAGAGTTGAGCCGCTGT Reverse ATGCTTTGAATCCAAAAACCTTAC |

| PI3K | Forward ACTCTCAGCAGGCAAAGACC Reverse ATTCAGTTCAATTGCAGAAGGAG |

| Akt | Forward GAAGGACGGGAGCAGGC Reverse AAGGTGCGTTCGATGACAGT |

| mTOR | Forward CTTAGAGGACAGCGGGGAAG Reverse TCCAAGCATCTTGCCCTGAG |

| NF-kB | Forward GGGCAGGAAGAGGAGGTTTC Reverse TATGGGCCATCTGTTGGCAG |

| GAPDH | Forward CGAGATCCCTCCAAAATCAA Reverse TTCACACCCATGACGAACAT |

miRNA target gene luciferase reporter assay and knockdown

To generate pmiR-RB-Report™-hDICER1 and pmiR-RB-Report™-hPTEN dual luciferase reporter plasmids, 3ʹUTRs of DICER1 and PTEN were PCR-amplified using HEK293T genomic DNA as a template and cloned into the pmiR-RB-REPORT™ dual luciferase reporter vector (RiuboBio Co. Ltd., Guangzhou, China.). To generate reporter plasmids with mutated miR-107 binding sequences, site-directed mutagenesis was performed to mutate “ATGCTGC” to “TACGACG” on hDICER1 3ʹUTRs, and “ATGCTGC” to “TACGACG” on PTEN 3ʹUTR. To validate the target genes of hsa-miR-107, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with hsa-miR-107 mimic (50 nM), together with pmiR-RB-Report™-hDICER1 or pmiR-RB-Report™-hPTEN plasmids (1 μg) using Lipofectamine 2000® Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Transfected cells were then cultured for 24 hrs before being analyzed for reporter expression using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promage corporation, Wisconsin, USA ).

To knock down DICER1 or PTEN in MDSCs, hDICER1 siRNA (50 nM) or hPTEN siRNA (50 nM) was transfected into HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs using Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

miRNA-107 overexpression and knockdown

To determine the effect of has-miR-107 overexpression or knockdown on MDSC proliferation, HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs were transfected with hsa-miR-107 mimic (50 nM) or hsa-miR-107 inhibitor (100 nM) using Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific), cultured for 3, 24, 48 and 96 hrs before being labeled with CFSE and analyzed with a flow cytometer as described above. After 96 hrs of culture, mRNA and protein were also extracted from transfected HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs for RT-qPCR and western blot, respectively.

Western blot analysis

To extract total proteins, HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs were lysed by RIPA solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.4), 1%(v/v) Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM leupeptin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na3VO4, and then centrifuged at 13,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The protein quantity was determined by a BCA protein kit (Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Total protein lysate of 60 μg was separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The PVDF membrane was then incubated with one of the following primary antibodies overnight at 4° C: anti-DICER1, anti-PTEN, anti-ARG1, anti-NOS2, Anti-AKT, anti-mTOR, anti-NF-kB, anti-p-AKT (ser473), anti-p-mTOR (ser2448), anti-p65-NF-kB (ser536) (1:1000 dilution), and anti-β-actin (1:5000) antibodies. Membranes were then incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (diluted 1:2000) for 2 hrs at room temperature (all antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, California, USA), followed by a standard chemiluminescent detection procedure. Image J software was used to determine relative protein expression quantitatively.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) guidelines with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Drug Safety Evaluation Center of The First Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Chinese Medicine (protocol number YFYDW2015013). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all subjects gave written informed consent to participate. The Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Chinese Medicine approved the study (protocol number 2016HL-085).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated in at least 3 independent studies. The data were presented as mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. Student’s t-test was used for all comparisons and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

miR-107 expression was elevated in gastric cancer cells, their secreted exosomes, and serum of gastric cancer patients

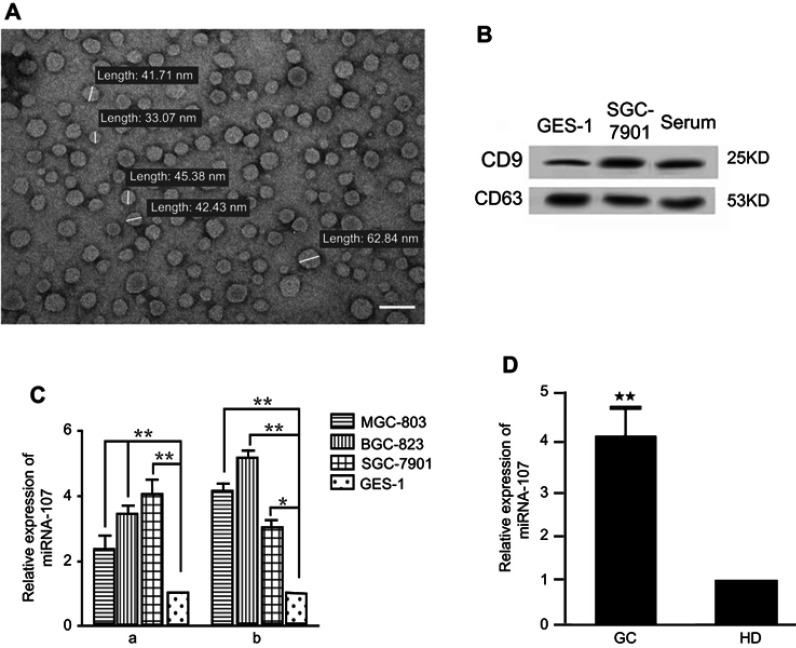

Previous studies showed that miR-107, among other miRNAs, was up-regulated in gastric cancer tissues, and its expression was correlated with disease prognosis, tumor invasion, and metastasis.20–22 However, whether miR-107 is over-represented in TDEs secreted by gastric cancer cells has remained elusive. TDEs were isolated from MGC-803, BGC-823, SGC-7901 gastric cancer cell lines, GES-1 normal gastric epithelial cell line, and serum samples. We examined the morphologies and sizes of the exosomes under a transmission electron microscope, JEM-1400. The sizes of these TDEs ranged from 30 to 100 nm in diameter (Figure 1A). In addition, we found enriched expression of exosomal surface markers CD9 and CD63 in isolated exosomes from gastric cell line and serum samples (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

miR-107 expression in gastric cancer cells, exosomes, and serum of gastric cancer patients.

Notes: (A) Gastric TDEs under a transmission electron microscope. The size of TDEs ranges from 30–100 nm (images are at ×20,000). (B) Detection of exosomal surface markers CD9 and CD63 by Western blot in normal gastric epithelial cell, gastric cancer cell lines, and patient serum. (C) Increased miR-107 levels in gastric cancer cell lines and their TDEs. (a) Relative miR-107 expression in gastric cancer cell lines MGC-803, BGC-823, and SGC-7901 cells, normalized to that in the normal gastric epithelial GES-1 cell. (b) Relative miR-107 expression in TDEs, normalized to that in the GES-1-secreted exosomes. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n=6). (D) Increased miRNA-107 levels in serum from gastric cancer patients and healthy donors. miR-107 expression was determined by real-time quantitative PCR. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n=16). *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: GC, gastric cancer; HD, healthy donor.

To determine miR-107 expression, we performed RT-qPCR on total RNAs extracted from MGC-803, BGC-823, SGC-7901, and GES-1 cell lines. As shown in Figure 1C-a, miR-107 expression was 2–4 fold higher in gastric cells than that of the normal GES-1 cells (P<0.01). This result corroborates previous findings that gastric cancer cells have elevated expression of miR-107.20–22 More importantly, we found that miR-107 content in TDEs derived from these 3 gastric cancer cell lines was 3–5 fold higher than in exosomes from GES-1 cells (P<0.01) (Figure 1C-b), suggesting that miR-107 is not only overexpressed in gastric cancer cells, but also enriched in TDEs secreted by these cells. To determine whether enriched miR-107 could also be found in the exosomes isolated from the peripheral blood of gastric cancer patients, we performed miR-107 RT-qPCR on miRNAs extracted from the serum of cancer patients and healthy volunteers. We found that miR-107 expression was significantly higher in the serum of gastric cancer patients than those of healthy subjects (P<0.01) (Figure 1D). In summary, our data shows that miR-107 was not only overexpressed in gastric cancer cell lines, but also over-represented in the TDEs secreted by these cells as well as in those found in the peripheral blood of gastric cancer patients.

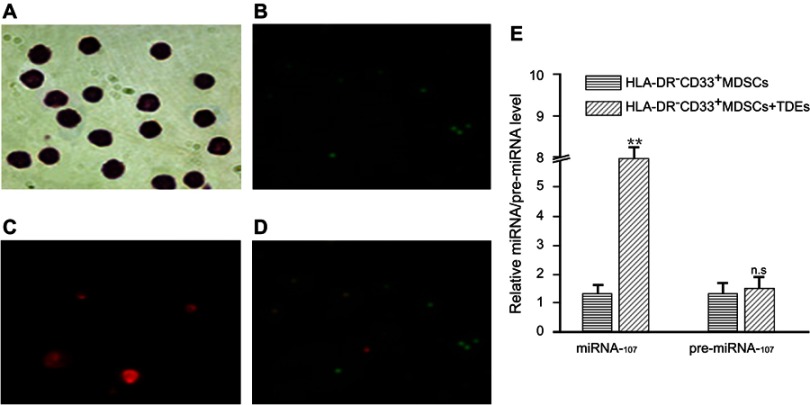

Gastric cancer cells can deliver miR-107 into HLA-DR-CD33+ MDSCs via TDEs in vitro

To determine whether miR-107 in the gastric cancer cell-derived TDEs could be delivered into HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs, we transfected the gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901 with a Cy3-conjugated miR-107. We extracted TDEs as described in the Materials and Methods. We then incubated HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs with the TDEs for 6 hrs before examining for Cy3 expression. As shown in Figure 2A–D, in vitro incubation with the TDEs was sufficient to deliver Cy3-labled miR-107 into MDSCs. To determine the amount of miR-107 delivered into MDSCs via TDEs, we incubated HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs with the TDEs for 24 hrs before examining for miR-107 expression by RT-qPCR. As shown in Figure 2E, incubation with gastric cancer cell-derived TDEs increased miR-107 expression by more than 4 fold as compared with that in the unincubated MDSCs (P<0.01). To exclude the possibility that the increased miR-107 expression was due to upregulation of the endogenous miR-107 gene in the MDSCs, we measured the level of precursor miR-107 (pre-miR-107) by RT-qPCR. We found that, unlike mature miR-107, there was no significant difference in pre-miR-107 expression (fold change =1.14; P>0.05) between unincubated MDSCs and MDSCs exposed to miR-107-containing TDEs (Figure 2E), suggesting that the increased miR-107 in MDSCs was from the exogenous gastric cancer cell-derived TDEs.

Figure 2.

miR-107 delivery into HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs via TDEs secreted by gastric cancer cells.

Notes: HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs were incubated with TDEs containing Cy3-labeled miR-107 for 6 hrs prior to examination for miR-107 internalization. Shown here are Wright stained image, magnification × 400, (A), CFSE proliferation dye, magnification × 100 (B, Cy3-miR-107 , magnification × 400 (C), and a merged image of CFSE and Cy3, magnification × 100 (D) showing internalization of miR-107 into proliferating HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs. (E) HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs were incubated with TDEs containing miR-107 for 24 hrs prior to collection for real-time quantitative PCR analysis. Shown here is relative expression of miR-107 and pre-miR-107 in the MDSCs. The data are presented as mean ± SD (n=6). **P<0.01.

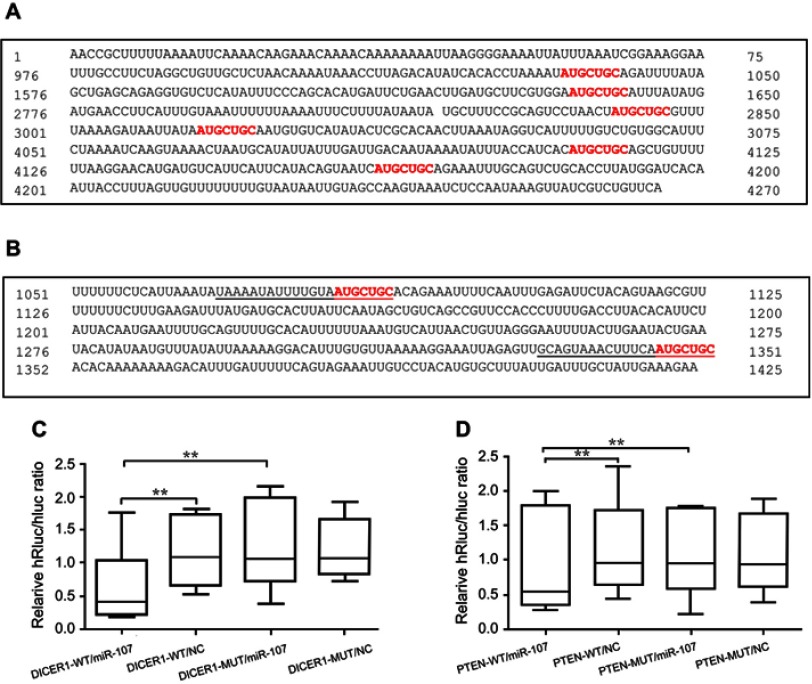

miR-107 targets 3ʹUTRs’s of DICER1 and PTEN mRNAs in a “seed” sequence-specific manner

Binding of a mature miRNA to its target gene depends mainly on a 6-8bp “seed region” with a nearly perfect complementary sequence to that within, in most cases, the 3ʹUTRs of the target mRNA.23 In order to confirm that DICER1 and PTEN could be targeted by miR-107, we performed TargetScan,24 PicTar,25 and miRanda26 (microrna.org and miRBase) to search for potential miR-107-binding sequences (“seed” sequence: UACGACGA) within the 3ʹUTRs of these 2 genes. Six possible binding sites were found in the DICER1 mRNA-3ʹUTR (Figure 3A) and two possible binding sites were found in the PTEN mRNA-3ʹUTR (Figure 3B). To verify target engagement of miR-107 to the 3ʹUTRs of DICER1 and PTEN mRNAs, we generated 2 luciferase reporter plasmids, pmiR-RB-Report™-hDICER1 and pmiR-RB-Report™-hPTEN, and transfected them into HEK293T cells together with a miR-107 mimic. We found that the miR-107 mimic was capable of interfering with luciferase reporter expression in the presence of intact miR-107 “seed” binding sequences within the 3ʹUTR of either DICER1 (P<0.05) (Figure 3C) or PTEN (P<0.05) (Figure 3D) mRNAs. However, decreased reporter expression was not found in the cells transfected with mutant miR-107 binding sequences, nor in cells without miR-107 mimic (Figure 3C and D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that miR-107 is able to target the 3ʹUTRs of both DICER1 and PTEN mRNA’s and these interactions are highly dependent upon the presence of intact sequences in the 3ʹUTRs complementary to the “seed” sequence of mature miR-107.

Figure 3.

Sequence-specific targeting of DICER1 and PTEN 3ʹUTRs by miR-107.

Notes: (A) Software-predicted miR-107 binding sites within the 3ʹUTR of DICER1 mRNA. (B) Software-predicted miR-107 binding sites within the 3ʹUTR of PTEN mRNA. (C–D) Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay in HEK293T cells transfected with luciferase reporter constructs as indicated, including pmiR-RB-Report™-hDICER1 (C) or pmiR-RB-Report™-hPTEN (D), together with miR-107 mimics or negative control (NC). **P<0.01.

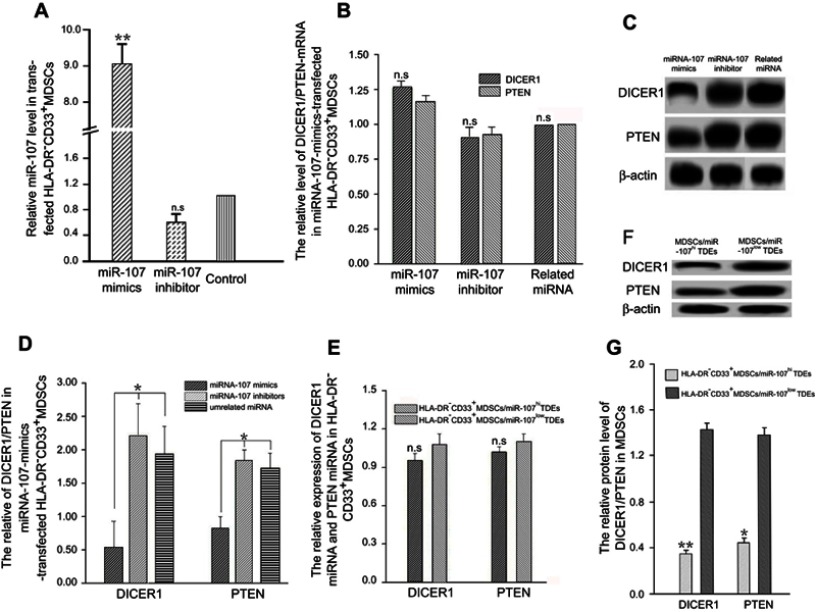

Exosomal miR-107 derived from gastric cancer cells down-regulates DICER1 and PTEN expression in MDSCs

To validate that DICER1 and PTEN expression in the HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs is post-transcriptionally regulated by miR-107, we performed gain- and loss-of-function studies in which we transiently transfected synthetic miR-107 mimics, miR-107 inhibitors (anti-miR) and an unrelated control miRNA into the MDSCs and determined their effects on DICER1 and PTEN expression. As shown in Figure 4A, the miR-107 mimic increased expression of miR-107 up to 9 fold (P<0.01) compared with that in cells transfected with control miRNA, while the anti-miR decreased miR-107 expression around 40%. Notably, neither miR-107 mimic nor inhibitor significantly changed the target gene expression at the mRNA level as determined by RT-qPCR (P>0.05) (Figure 4B). On the other hand, miR-107 mimic reduced while the inhibitor increased expression of both DICER1 and PTEN at the protein level (P<0.05) (Figure 4C–D).

Figure 4.

Down-regulation of DICER1 and PTEN in MDSC by exosomal miR-107 derived from gastric cancer cells.

Notes: (A) miR-107 mimic, inhibitor, and an unrelated control miRNA were transfected into MDSCs and miR-107 expression was determined using RT-qPCR. (B) DICER1 and PTEN mRNA expression in miR-107-transfected MDSCs. (C) DICER1 and PTEN protein expression in miR-107-transfected MDSCs. (D) Quantification of protein expression in (C). (E) DICER1 and PTEN mRNA expression in MDSCs incubated with miR-107hi or miR-107low TDEs. (F) DICER1 and PTEN protein expression in MDSCs incubated with miR-107hi or miR-107low TDEs. (G) Quantification of protein expression in (F). *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: n.s., not significant; RT-qPCR, real-time quantitative PCR.

To further determine whether miR-107 derived from TDEs is capable of regulating target gene expression in MDSCs, we transiently transfected SGC-7901 gastric cancer cells with miR-107 mimic to generate miR-107-high exosomes (miR-107hi TDEs), or miR-107 inhibitor to generate miR-107-low exosomes (miR-107low TDEs), for co-incubation with HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs. After incubation for 96 hrs with TDEs, we collected MDSCs for RT-qPCR and Western blot analyses. As shown in Figure 4E, there was no significant difference in DICER1 or PTEN mRNA levels in MDSCs exposed to TDEs containing either the miR-107 mimic or the inhibitor (P>0.05). However, both DICER1 and PTEN proteins were significantly reduced in MDSCs incubated with the miR-107 mimic as compared with those with the anti-miR (P<0.05) (Figure 4F–G). In summary, these data suggest that miR-107 can be functionally delivered from gastric cancer cells to MDSCs via TDEs and that miR-107 regulates its target gene DICER1 and PTEN expression at the protein but not mRNA level.

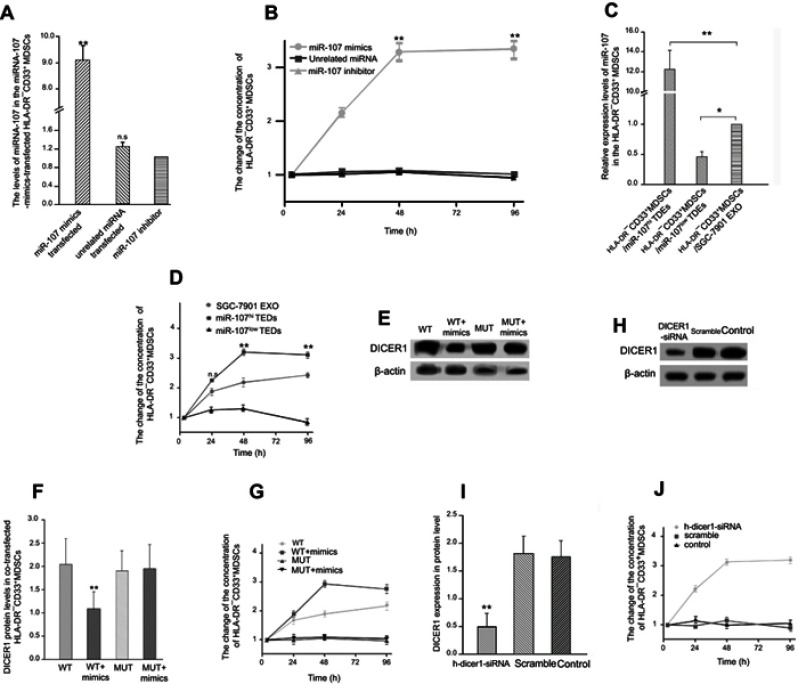

Exosomal miR-107 promotes HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs expansion by dampening DICER1 expression

To determine the effect of exogenous miRNA-107 on MDSCs, we separately transfected miR-107 mimic, inhibitor and an unrelated miRNA into HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs isolated from healthy human peripheral blood. We then confirmed the expression of miRNA-107 in transfected HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs by qRT-PCR. As shown in Figure 5A, miR-107 was markedly increased in MDSCs transfected with the mimic (fold change >8; P<0.01), while the miR-107 anti-miR did not show an obvious effect on miR-107 expression. To determine the effect of miR-107 mimic and anti-miR on MDSCs proliferation, we labeled transfected MDSCs with PE-Cy7 anti-HLA-DR and APC anti-CD33 antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. We found that the number of HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs transfected with miR-107 mimic was significantly higher than that in the control group (fold change >2; P<0.05), while the number of MDSCs transfected with anti-miR was significantly reduced (fold change <0.5; P<0.05) (Figure 5B). These results suggest that exogenous miR-107 induces proliferation of HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs.

Figure 5.

Expansion of HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs induced by exosomal miR-107-mediated DICER1 suppression.

Notes: (A) miR-107 mimic, inhibitor, or an unrelated control miRNA were transfected into MDSCs, and miR-107 expression was determined using RT-qPCR. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=6). (B) Number of MDSCs was determined at 3, 24, 48, 72 and 96 hrs after transfection with miR-107 mimic, inhibitor, or unrelated miRNA. Data were normalized to the MDSCs amount at 3 hrs. (C) miR-107 expression in MDSCs incubated for 96 hrs with miR-107hi, miR-107low TDEs or control TDEs from SGC-7901. (D) Relative number of MDSCs incubated with miR-107hi, miR-107low TDEs or control TDEs from SGC-7901. (E) WT or mutant DICER1 mRNA 3ʹUTR plasmids were separately transfected into HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs with the miR-107 mimic, and DICER1 protein expression determined by Western blot. (F) Quantification of protein expression in (E). (G) Relative number of MDSCs co-transfected with miR-107 mimic and WT or mutant DICER1 mRNA 3ʹUTR plasmids. (H) DICER1 or scrambled siRNAs were transfected into MDSC, and DICER1 protein expression determined by Western blot. (I) Quantification of protein expression in (H). (J) Relative number of MDSCs transfected with DICER1 or scrambled siRNAs. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: n.s., not significant; RT-qPCR, real-time quantitative PCR.

We next sought to determine whether miR-107 delivered via gastric cancer cell-derived exosomes were capable of inducing MDSCs proliferation. We extracted SGC7901-derived miR-107hi TDEs and miR-107low TDEs and co-incubated them with the sorted HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs for 96 hrs, using MDSCs co-incubated with parental SGC-7901 TDEs as a negative control. miR-107 expression in MDSCs after co-incubation with miR-107hi TDEs dramatically increased (fold change >12; P<0.01), while those with miR-107low TDEs showed significantly lower miR-107 expression (fold change <0.5; P<0.05) (Figure 5C). To determine the effect of TDE-delivered miR-107 on the proliferation of MDSCs, We analyzed co-incubated MDSCs by flow cytometry. Compared with those exposed to control TDEs, HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs co-cultured with miR-107hi TDEs were significantly increased (P<0.05), and the effect lasted up to 96 hrs of culture (Figure 5D). On the contrary, HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs with miR-107low TDEs were significantly decreased compared to the control group (P<0.05) (Figure 5D). These data suggest that miR-107 derived from SGC-7901 TDEs can induce the proliferation of HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs.

We showed that miR-107 suppressed DICER1 expression by targeting its mRNA 3ʹUTR (Figure 3C), and that exosomal miR-107 was able to induce MDSCs expansion (Figure 5D). To determine whether the effect of miR-107 on MDSCs proliferation was dependent upon its ability to target the DICER1 mRNA 3ʹUTR, we separately transfected WT and mutant DICER1-3ʹUTR plasmids into HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs, together with the miR-107 mimic. After 96 hrs, the amount of DICER1 protein and MDSCs proliferation were determined by Western blot and flow cytometry, respectively. miR-107 mimic significantly decreased expression of DICER1 protein in MDSCs co-transfected with WT DICER1-3ʹUTR (fold change <0.6; P<0.05), but not those co-transfected with mutant DICER1-3ʹUTR (Figure 5E and F). Furthermore, co-transfection of miR-107 mimic and WT DICER1-3ʹUTR dramatically increased the number of HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs in culture, an effect that was absent in mutant DICER1-3ʹUTR-transfected MDSCs (Figure 5G). To further support the notion that inhibition of the DICER1 gene can lead to proliferation of HLA-DR−CD33+ MDSCs, we transfected siRNAs targeting DICER1 into the MDSCs. DICER1 knockdown by siRNA significantly inhibited DICER1 protein expression in MDSCs (fold change <0.3; P<0.01) (Figure 5H and I). In addition, siRNA significantly increased the number of HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs (fold change >2; P<0.05) (Figure 5J). These results suggest that DICER1 knockdown increases proliferation of HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs and that miR-107 induces MDSCs expansion by targeting the DICER1 3ʹUTR.

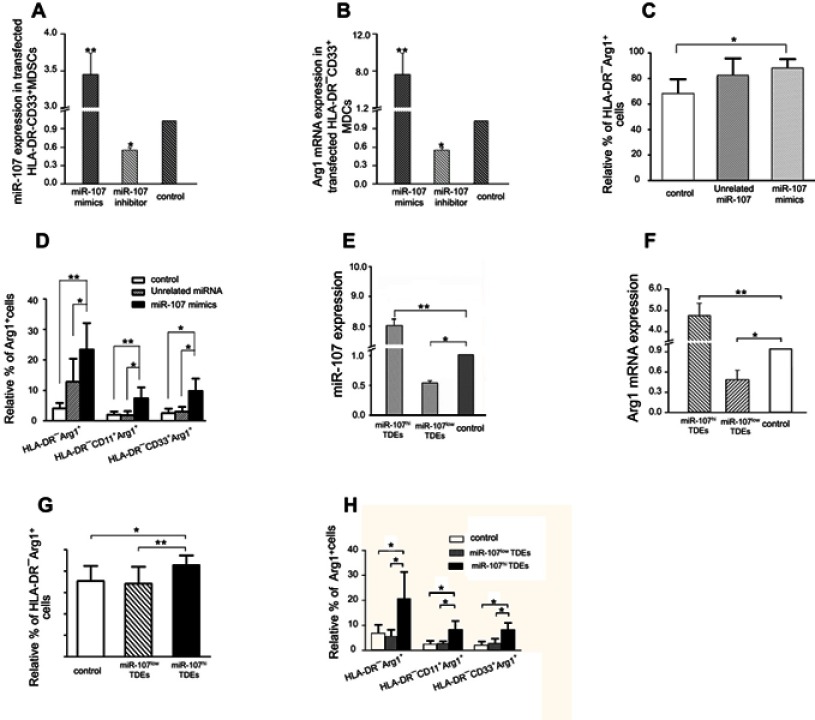

Exosomal miR-107 increases ARG1 expression in HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs

To determine the effect of exogenous miR-107 on ARG1 expression in HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs in vitro, we separately transfected miR-107 mimic, inhibitor and a control miRNA into MDSCs, and verified their effects on miR-107 expression by RT-qPCR (fold change >3; P<0.05) (Figure 6A). We found that MDSCs transfected with the miR-107 mimic showed a significant increase in expression of ARG1 after 96 hrs of culture (fold change >8; P<0.01) (Figure 6B). Furthermore, we confirmed the expression of ARG1 at the protein level by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 6C and D, miR-107 mimic increased ARG1 protein expression in HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs (fold change >3; P<0.05), while the effect was absent in MDSCs transfected with either the anti-miR or unrelated control miRNA. We next sought to determine whether miR-107 derived from SGC-7901 TDEs had the same effect on ARG1 expression in MDSCs. We generated miR-107high and miR-107low TDEs and co-incubated with HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs before measuring miR-107 and ARG1 expression by RT-qPCR. As shown in Figure 6E, miR-107 expression was significantly higher in miR-107high TDE-co-incubated cells (fold change >3; P<0.05), while those with miR-107low TDEs showed lower miR-107 expression compared to that of the control group. In addition, expression of ARG1 mRNA was increased in MDSCs co-incubated with miR-107high TDEs (fold change >4; P<0.01) (Figure 6F), as well as ARG1 protein as determined by flow cytometry (fold change >3; P<0.01) (Figure 6G and H). These data support that miR-107 in gastric cancer cell-derived exosomes is capable of increasing ARG1 expression in HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs.

Figure 6.

Exosomal miR-107 increases ARG1 expression in HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs.

Notes: (A) miR-107 mimic, inhibitor, or an unrelated control miRNA were transfected into MDSCs, and miR-107 expression determined using RT-qPCR. (B) Relative ARG1 mRNA expression in transfected MDSCs. (C-D) Relative % of ARG1-positive cells within HLA-DR−, HLA-DR−CD11b+ or HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs population after transfection with miR-107 mimic, inhibitor or an unrelated control miRNA. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=6). (E) miR-107 expression in MDSCs incubated for 24 hrs with miR-107hi, miR-107low TDEs or control TDEs from SGC-7901. (F) ARG1 mRNA expression in MDSCs incubated with miR-107hi, miR-107low TDEs or control TDEs. (G–H) Relative % of ARG1-positive cells within HLA-DR−, HLA-DR−CD11b+ or HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs population after transfection with miR-107hi, miR-107low TDEs or control TDEs from SGC-7901. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=6). *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Abbreviation: RT-qPCR, real-time quantitative PCR.

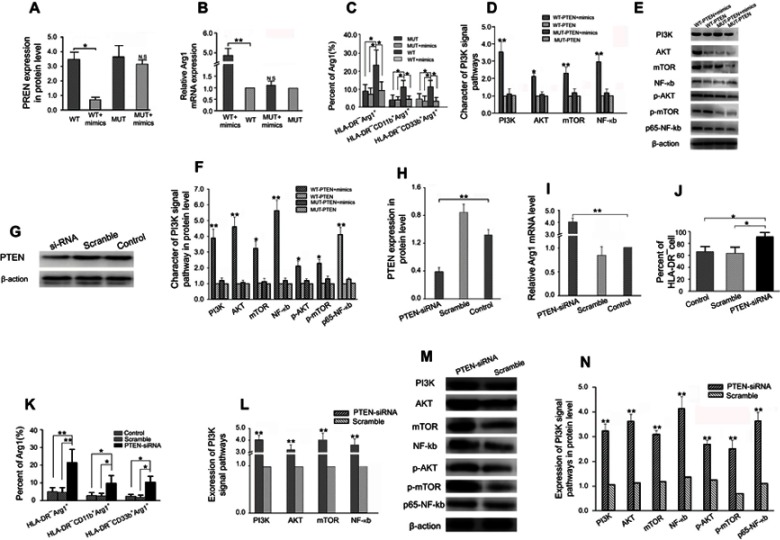

miR-107 induces ARG1 expression in MDSCs by inhibiting PTEN

We demonstrated that miR-107 could target the 3ʹUTR of PTEN mRNA to decrease its expression (Figure 3D), and that exosomal miR-107 was able to induce ARG1 expression (Figure 6). To determine whether the effect of miR-107-promoted ARG1 expression was dependent upon its ability to target the PTEN mRNA 3ʹUTR, we co-transfected miRNA-107 mimic with WT or mutant PTEN-3ʹUTR plasmid into HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs, and determined expression of ARG1 and PTEN. miR-107 mimic significantly decreased expression of PTEN protein in MDSCs co-transfected with WT PTEN-3ʹUTR (fold change <1.0; P<0.05), but not those co-transfected with mutant PTEN-3ʹUTR (Figure 7A). Additionally, we found expression of both ARG1 mRNA (fold change >3.0; P<0.05) (Figure 7B) and protein (P<0.05) (Figure 7C) significantly increased in cells co-transfected with miR-107 mimic and WT but not mutant PTEN-3ʹUTR. Since PTEN is one of the most important negative regulators of the PI3K pathway, it is therefore of interest to determine whether miR-107-induced PTEN suppression has an impact on PI3K pathway activation and if this change leads to induction of ARG1 expression as observed in miR-107-transfected MDSCs. As shown in Figure 7D, MDSCs co-transfected with miR-107 mimic and WT PTEN-3ʹUTR showed increased mRNA expression of PI3K, AKT, mTOR, and NF-kB, as compared to the expression in MDSCs without transfected miR-107 mimic (P<0.05); whereas miR-107 mimic failed to induce expression of the 4 mRNAs when in the presence of a mutant PTEN-3ʹUTR. Furthermore, co-transfection with miR-107 mimic and WT PTEN-3ʹUTR not only induced protein expression of PI3K, AKT, mTOR, and NF-kB, but also increased phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT), p-mTOR and the NF-kB subunit p65 (P<0.05) (Figure 7E and F). To determine if PTEN inhibition can lead to increased ARG1 expression in MDSCs, we transfected siRNA targeting PTEN into HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs and determined levels of PTEN and ARG1 after 96 hrs in culture. As shown in Figure 7G and H, PTEN-targeting siRNA decreased PTEN protein expression compared to that of scrambled siRNA. Also, MDSCs transfected with PTEN siRNA also showed decreased expression of ARG1 both in mRNA (Figure 7I) and protein (Figure 7J and K) levels. Importantly, PTEN knockdown by siRNA in MDSCs also led to activation of the PI3K pathway, which was implicated by increased mRNA expression of its downstream effectors AKT, mTOR, and NF-kB (Figure 7L), as well as AKT, mTOR, NF-kB, p-AKT, p-mTOR proteins (Figure 7M and N). In summary, we show that miR-107 is able to suppress PTEN expression via targeting its mRNA 3ʹUTRs, which leads to activation of the PI3K pathway, and that PTEN knockdown induces expression of ARG1 in HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs.

Figure 7.

Increased ARG1 expression in HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs induced by exosomal miR-107-mediated PTEN suppression and PI3K pathway activation.

Notes: (A) MDSCs were co-transfected with WT PTEN-3ʹUTR or mutant PTEN-3ʹUTR together with miR-107 mimic. PTEN protein expression was then determined by Western blot. (B) ARG1 mRNA expression in co-transfected MDSCs determined by RT-qPCR. (C) Relative % of ARG1-positive cells within HLA-DR−, HLA-DR−CD11b+ or HLA-DR−CD33+MDSC population determined by flow cytometry after co-transfection with WT or mutant PTEN-3ʹUTR and miR-107 mimic. (D) mRNA expression of PI3K, AKT, mTOR, and NF-kB in co-transfected MDSCs. (E) PI3K, AKT, mTOR, NF-kB, p-AKT, p-mTOR and p65 subunit of NF-kB protein expression was determined by Western blot. (F) Quantification of protein expression in (E). (G) PTEN or scrambled siRNAs were transfected into the MDSCs, and PTEN protein expression was determined by Western blot. (H) Quantification of protein expression in (G). (I) Relative ARG1 mRNA expression in MDSCs transfected with PTEN or scrambled siRNAs. (J–K) Relative % of ARG1-positive cells within HLA-DR−, HLA-DR−CD11b+ or HLA-DR−CD33+MDSC population after transfection with PTEN or scrambled siRNAs. (L) mRNA expression of PI3K, AKT, mTOR and NF-kB in MDSCs transfected with PTEN or scrambled siRNAs. (M) PI3K, AKT, mTOR, NF-kB, p-AKT, p-mTOR and p65 subunit of NF-kB protein expression in MDSCs transfected with PTEN or scrambled siRNAs. (N) Quantification of protein expression in (M). *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Abbreviations: n.s., not significant; RT-qPCR, real-time quantitative PCR.

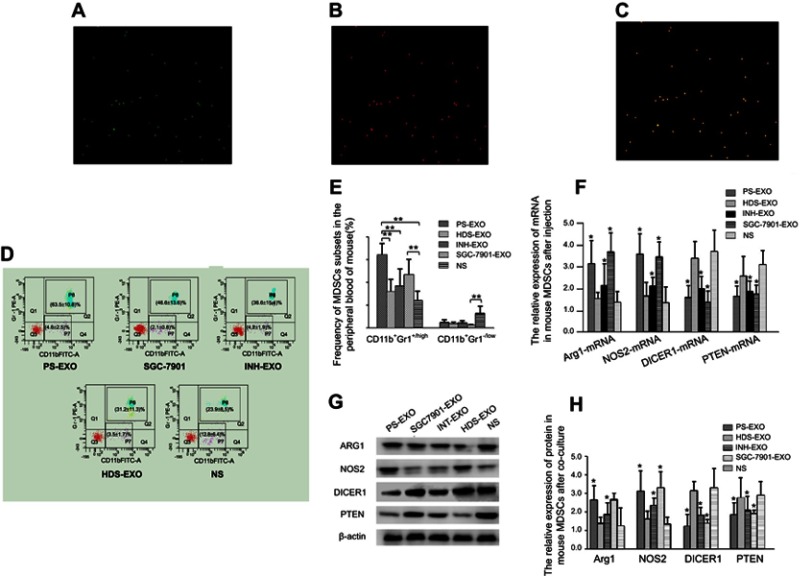

Exosomal miR-107 promotes CD11b+Gr1+/high MDSCs expansion in vivo

To determine whether gastric cancer cell-derived exosomes can deliver molecular cargos to MDSCs in vivo, we transfected SGC-7901 cells with Cy3-labeled miR-107 mimic, extracted the TDEs, and injected them intravenously into the tail vein of mice. After 72 hrs, we collected whole blood from the tail vein and isolated CD11b+Gr1+/high MDSCs using MACS separation. The MDSCs were also labeled with CFSE proliferation dye (green fluorescent). As shown in Figure 8A–C, we observed co-localization of CFSE dye and Cy3-labeled miR-107 mimic in almost all the isolated mouse MDSCs, suggesting SGC-7901 TDEs can deliver the mimic into MDSCs in vivo. We then asked whether miR-107 delivered by the TDEs can induce MDSCs expansion in the animals. For this purpose, TDEs from parental SGC-7901 cells (SGC-7901-EXO) or those transfected with miR-107 inhibitor (INH-EXO) were isolated, and injected into tail veins of mice with a bolus of 20 μg exosomes every other day for 7 times. Also included in the study were exosomes from healthy volunteer serums (HDS-EXO) and TDEs from gastric cancer patient serums (PS-EXO), the latter of which were shown to contain miR-107 TDEs (Figure 1D). Seventy-two hrs after the last dose, whole blood was withdrawn from the abdominal vein of mice, and the percentage of CD11b+Gr1+/highMDSCs was analyzed by flow cytometry using FITC anti-Gr-1 and PE anti-CD11b antibodies. We found a significantly higher percentage of CD11b+Gr1+/highMDSCs, but not CD11b+Gr1−/low cells, in mice injected with SGC-7901 TDEs or cancer patient TDEs than that in animals injected with miR-107-depleted TDEs or healthy donor exosomes (Figure 8D and E), demonstrating that miR-107 delivered via gastric cancer TDEs is able to induce expansion of MDSCs in vivo.

Figure 8.

Exosomal miR-107 induces mouse CD11b+Gr1+/highMDSCs expansion in vivo.

Notes: (A–C)magnification × 100 SGC-7901-secreted TDEs containing Cy3-labeled miR-107 mimic was injected intravenously into tail veins of mice. After 72 hrs, CD11b+Gr1+/highMDSCs were collected and labeled with CFSE proliferation dye (A). Also shown are MDSCs labeled by Cy3-labeled miR-107 mimic (B), and a merged image of (A) and (B). (D) Flow cytometry analyses of MDSCs from mice injected with normal saline (NS), TDEs from parental SGC-7901 cells (SGC-7901-EXO), those transfected with miR-107 inhibitor (INH-EXO), exosomes from healthy volunteer serums (HDS-EXO) and TDEs from gastric cancer patient serums (PS-EXO), showing the percentage of CD11b+Gr1+/high and CD11b+Gr1−/low populations of cells within each group. (E) Quantification of flow cytometry data in (D). (F) mRNA expression of ARG1, NOS2, DICER1 and PTEN in MDSCs isolated from exosome-injected mice. (G) Western blot showing relative protein expression of ARG1, NOS2, DICER1 and PTEN in MDSCs isolated from exosome-injected mice. (H) Quantification of protein expression in (G). *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

We showed that exosomal miR-107 from gastric cancer cells is capable of suppressing DICER1 and PTEN and inducing ARG1 in isolated MDSCs in vitro. We then asked whether expression of DICER1, PTEN, ARG1, and NOS2 in CD11b+Gr1+/highMDSCs can also be modulated by exosomal miR-107 in vivo. Thus, we isolated CD11b+Gr1+/highMDSCs by MACS sorting from animals injected with SGC-7901-EXO, INH-EXO, PS-EXO, HDS-EXO, and saline negative control (NS), and determined expression of DICER1, PTEN, ARG1, and NOS2 genes by RT-qPCR and Western blot. We found significantly lower expression of ARG1 and NOS2, while expression of DICER1 and PTEN was higher in MDSCs from mice injected with either SGC-7901-EXO or PS-EXO (P<0.05), but not with INH-EXO, HDS-EXO, or NS (Figure 8F). We saw the same effects in protein levels for these genes (P<0.05) (Figure 8G and H). These data suggest that miR-107 delivered via gastric cancer TDEs to mouse CD11b+Gr1+/high MDSCs is able to induce ARG1 and NOS2 and suppress DICER1 and PTEN gene expression in vivo, validating our in vitro observations in cultured HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs.

Discussion

The major focus of oncology drug development in past decades has been to identify cancer-specific targets and to develop novel therapeutic strategies to efficiently eliminate cancer cells while sparing their normal counterparts. While these efforts resulted in a number of promising treatments, the efficacy was generally limited by intrinsic clonal heterogeneity and the presence of complex tumor microenvironments,27 which are composed of extracellular matrix, signaling molecules, blood vessels, and various normal tissue cells such as endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and immune cells.28 Interactions of tumor cells with components in the microenvironments add an additional layer of complexity and difficulty in the design of therapeutics against these cancers. Therefore, a better understanding of intercellular communications between cancer and normal cells will be key to success in future oncology drug development.

Exosomes are a type of extracellular vesicle released by all cell types including those of cancer and normal tissues, such as epithelial cells, dendritic cells, B lymphocytes, cytotoxic T cells, platelets, reticulocytes, mast cells, and adipocytes.29 Exosomes are capable of transmitting signaling molecules to target cells, representing an important intercellular communicator in both physiological and pathological conditions.30–33 Multiple studies have shown that tumor cells can utilize the secreted exosomes to transmit molecular signals to cells in the microenvironment to support cell migration, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis.7,34–36 In addition, TDEs delivered into immune cells can result in host immunosuppression through inhibition of anti-tumor responses from dendritic cells, NK cells, and T cells, as well as through induction of immunosuppressive responses from MDSCs, Tregs, and Bregs.2,37 TDEs can carry genomic DNA, mRNA, proteins, and miRNAs. Particularly, miRNAs delivered by TDEs to tumor microenvironment were shown to play an important role in supporting tumor progression via multiple mechanisms, including but not limited to promoting tumor immune escape.27

Previous studies showed that miR-107 was overexpressed in gastric cancers and its expression was associated with a poor prognosis in gastric cancer patients;20 furthermore, miR-107 was shown to regulate gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis by targeting the DICER1 gene.21 Our findings, however, reveal a previously unknown mechanism by which miR-107 contributes to tumorigenesis. We show that in addition to regulating local gene expression in cancer cells, miR-107 is also able to be transmitted to bone marrow-derived immune cells in the tumor microenvironment to support cancer immune escape. Interestingly, we found that miR-107 delivered via TDEs is also capable of modulating expression of the DICER1 gene in HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs, much like it does in gastric cancer cells.21 DICER1, an RNase III endoribonuclease that is involved in the cleavage and maturation of miRNAs from pre-miRNAs, plays a key role in global miRNA biogenesis.38 It has been shown that impairment of miRNA maturation enhanced transformation in cancer cells, and that global down-regulation of miRNAs was functionally relevant to oncogenesis; therefore, it was not surprising that DICER1 was identified as a tumor suppressor in human cancers,21,39,40 and that miR-107-mediated DICER1 down-regulation resulted in tumor progression.21 On the other hand, the role of DICER1 suppression in MDSCs within the tumor microenvironment was relatively undefined. Nevertheless, several transgenic animal studies showed that DICER1 deletion results in de-repression of stem cell self-renewal genes in myeloid-committed progenitor cells, abnormal myeloid differentiation, and myeloid dysplasia, a precancerous growth of myeloid cells.41 Our data shows that exogenous miR-107 from gastric cancer-derived TDEs suppresses DICER1 expression, leading to expansion of MDSCs, implicating that in pathological conditions, DICER1 could also promote myeloid cell proliferation and survival. Furthermore, the horizontal transfer of miR-107 from gastric cancer cells to MDSCs suggests that the level of miR-107 would not be affected by global loss of miRNA biogenesis caused by DICER1 down-regulation, by passing a potential feedback regulatory mechanism between miR-107 and DICER1.42

While the role of PTEN in tumor suppression is well documented,43,44 its importance in other disease such as diabetes, infectious diseases, inflammation and neurodevelopmental disorders, has been relatively less studied.45,46 Apparently, in the context of infectious diseases such as pneumococcal pneumonia, PTEN blockade results in the dampening of inflammation in the lung and prolonging of animal survival post-bacterial infection.46 To elucidate the molecular mechanisms of PTEN-mediated anti-inflammatory responses, researchers exposed PTEN-deficient myeloid cells to pathogens and searched for genes that were differentially expressed as compared to those in wild-type myeloid cells, and found that loss of PTEN, or activation of PI3K signaling, led to decreased expression of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines.47 In the same study, ARG1 was also identified as one of the differentially expressed genes in the PTEN-deficient myeloid cells; ARG1 expression was markedly induced by PTEN deletion in macrophages, leading to a hypo-inflammatory environment.48 ARG1, a key player in the urea cycle, converts arginine to urea; therefore, myeloid cell-derived ARG1 is capable of depleting arginine from the environment under inflammatory conditions. As a result, a shortage of arginine blocks proliferation of T cells leading to T cell anergy and prevents T helper cell functions.49,50 Like myeloid cells undergoing an inflammatory response, MDSCs within the tumor microenvironment are also capable of suppressing immune responses via a series of inhibitory mechanisms, which contributes to tumor growth. Studies showed that tumor cell-derived prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) induced up-regulation of ARG1 in MDSCs, and ultimately led to cell cycle arrest in T cells.12,51 However, unlike that under inflammatory conditions, the connection between PTEN regulation and ARG1 expression has not been well defined for MDSCs within the tumor microenvironment. In this study, we demonstrated that gastric cancer cell-derived miR-107 could suppress MDSCs, which led to markedly increased ARG1 expression and immune suppression. These findings also raise further questions as to whether regulation of ARG1 expression in MDSCs is controlled by multiple complementary or redundant mechanisms (such as PTEN and PGE2-mediated regulation), and whether other PTEN-targeting miRNAs (such as miR-21, miR-181b, and miR-494) also contribute to ARG1 expression in MDSCs.19 Nonetheless, we showed that siRNA targeting PTEN increased ARG1 expression in MDSCs more than 4 fold as compared to that of control siRNA-treated cells, suggesting that the ARG1 level was directly modulated by PTEN status in the MDSCs (Figure 7I–K).

Undoubtedly, the tumor microenvironment is one of the indispensable components for tumor growth and survival, and inside it there are a large number of tumor-secreted molecules that contribute to the development of cancerous growth. Being able to stably transfer their molecular cargos to target cells, exosomes have been proven to be an effective and efficient intercellular communication vehicle between cancer cells and other cells in the tumor microenvironment.52 Our study provides evidences that gastric cancer-secreted TDEs can carry miR-107 and deliver it into HLA-DR−CD33+MDSCs to promote host immunosuppression that facilitates tumor progression.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings demonstrate for the first time that gastric cancer-secreted exosomes are able to deliver miR-107 to the host MDSCs, meanwhile we found that by suppressing both DICER1 and PTEN genes in MDSCs, gastric cancer-derived miR-107 was able to promote MDSCs expansion as well as induce its immunosuppressive function via increasing ARG1 expression. These findings not only broaden our understanding of how cancer cells may mediate immune escape at a distant site from the primary tumor, but also provide useful insights into development of MDSC-targeting therapeutic agents that may dramatically increase anti-cancer immunotherapy efficacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the patients and healthy donors for their donation of samples. This work was supported by grants from Colleges and Universities Key Scientific Research Project Plan Basic Research Special of Henan Province (Grant number 19zx009), Basic and Frontier Technology Research Program of Henan Province (Grant number 132300410448), Science and Technology Project for Tackling Key Problems of Henan Province (Grant number 182102311172), and Science and Technology Innovation Talent Program of Henan Province (Grant number 154100510019).

Abbreviation list

ARG1, arginase 1; GC, gastric cancer; MDSCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells; NOS2, nitric oxide synthase2; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; TDEs, tumor-derived exosomes; miR, microRNA; Treg, regulatory T cells.

Data sharing statement

The data and materials of this study are available from the corresponding authors for reasonable requests.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Gu Y, Cao X. The exosomes in tumor immunity. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(9):e1027472. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1027472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor DD, Gercel-Taylor C. Exosomes/microvesicles: mediators of cancer-associated immunosuppressive microenvironments. Semin Immunopathol. 2011;33(5):441–454. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0234-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valenti R, Huber V, Iero M, Filipazzi P, Parmiani G, Rivoltini L. Tumor-released microvesicles as vehicles of immunosuppression. Cancer Res. 2007;67(7):2912–2915. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteside TL. Tumor-derived exosomes and their role in tumor-induced immune suppression. Vaccines (Basel). 2016;4(4):35. doi: 10.3390/vaccines4040035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C, Robbins PD. The roles of tumor-derived exosomes in cancer pathogenesis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:842849. doi: 10.1155/2011/842849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whiteside TL. Tumor-derived exosomes and their role in cancer progression. Adv Clin Chem. 2016;74:103–141. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2015.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiang X, Poliakov A, Liu C, et al. Induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by tumor exosomes. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(11):2621–2633. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khaled YS, Ammori BJ, Elkord E. Increased levels of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in peripheral blood and tumour tissue of pancreatic cancer patients. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:879897. doi: 10.1155/2014/879897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, De Veirman K, De Beule N, et al. The bone marrow microenvironment enhances multiple myeloma progression by exosome-mediated activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6(41):43992–44004. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talmadge JE, Gabrilovich DI. History of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(10):739–752. doi: 10.1038/nrc3581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motallebnezhad M, Jadidi-Niaragh F, Qamsari ES, Bagheri S, Gharibi T, Yousefi M. The immunobiology of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(2):1387–1406. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4477-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(3):162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khaled YS, Ammori BJ, Elkord E. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer: recent progress and prospects. Immunol Cell Biol. 2013;91(8):493–502. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toh B, Wang X, Keeble J, et al. Mesenchymal transition and dissemination of cancer cells is driven by myeloid-derived suppressor cells infiltrating the primary tumor. PLoS Biol. 2011;9(9):e1001162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang L, DeBusk LM, Fukuda K, et al. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(4):409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connell RM, Rao DS, Chaudhuri AA, Baltimore D. Physiological and pathological roles for microRNAs in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(2):111–122. doi: 10.1038/nri2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen S, Zhang Y, Kuzel TM, Zhang B. Regulating tumor Myeloid-derived suppressor cells by MicroRNAs. Cancer Cell Microenviron. 2015;2(1):e637. doi: 10.14800/ccm.637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Gazzar M. microRNAs as potential regulators of myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion. Innate Immun. 2014;20(3):227–238. doi: 10.1177/1753425913489850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue T, Iinuma H, Ogawa E, Inaba T, Fukushima R. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of microRNA-107 and its relationship to DICER1 mRNA expression in gastric cancer. Oncol Rep. 2012;27(6):1759–1764. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Zhang Y, Shi Y, et al. MicroRNA-107, an oncogene microRNA that regulates tumour invasion and metastasis by targeting DICER1 in gastric cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(9):1887–1895. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01194.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng Q, Chen C, Guan H, Kang W, Yu C. Prognostic role of microRNAs in human gastrointestinal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(28):46611–46623. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price C, Chen J. MicroRNAs in cancer biology and therapy: current status and perspectives. Genes Dis. 2014;1(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115(7):787–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37(5):495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(11):e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neviani P, Fabbri M. Exosomic microRNAs in the tumor microenvironment. Front Med (Lausanne). 2015;2:47. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2015.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Challagundla KB, Fanini F, Vannini I, et al. microRNAs in the tumor microenvironment: solving the riddle for a better diagnostics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2014;14(5):565–574. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2014.922879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(8):569–579. doi: 10.1038/nri855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ratajczak J, Miekus K, Kucia M, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived microvesicles reprogram hematopoietic progenitors: evidence for horizontal transfer of mRNA and protein delivery. Leukemia. 2006;20(5):847–856. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Liu D, Chen X, et al. Secreted monocytic miR-150 enhances targeted endothelial cell migration. Mol Cell. 2010;39(1):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hannafon BN, Ding WQ. Intercellular communication by exosome-derived microRNAs in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(7):14240–14269. doi: 10.3390/ijms140714240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shao Y, Shen Y, Chen T, Xu F, Chen X, Zheng S. The functions and clinical applications of tumor-derived exosomes. Oncotarget. 2016;7(37):60736–60751. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grange C, Tapparo M, Collino F, et al. Microvesicles released from human renal cancer stem cells stimulate angiogenesis and formation of lung premetastatic niche. Cancer Res. 2011;71(15):5346–5356. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skog J, Wurdinger T, van Rijn S, et al. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(12):1470–1476. doi: 10.1038/ncb1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whiteside TL. Exosomes and tumor-mediated immune suppression. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(4):1216–1223. doi: 10.1172/JCI81136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rupaimoole R, Slack FJ. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(3):203–222. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar MS, Pester RE, Chen CY, et al. Dicer1 functions as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2009;23(23):2700–2704. doi: 10.1101/gad.1848209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merritt WM, Bar-Eli M, Sood AK. The dicey role of Dicer: implications for RNAi therapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:(7)2571–2574. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alemdehy MF, Erkeland SJ. Stop the dicing in hematopoiesis: what have we learned? Cell Cycle. 2012;11(15):2799–2807. doi: 10.4161/cc.21077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forman JJ, Legesse-Miller A, Coller HA. A search for conserved sequences in coding regions reveals that the let-7 microRNA targets Dicer within its coding sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(39):14879–14884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803230105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steck PA, Pershouse MA, Jasser SA, et al. Identification of a candidate tumour suppressor gene, MMAC1, at chromosome 10q23.3 that is mutated in multiple advanced cancers. Nat Genet. 1997;15(4):356–362. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pulido R. PTEN: a yin-yang master regulator protein in health and disease. Methods. 2015;77-78:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schabbauer G, Matt U, Gunzl P, et al. Myeloid PTEN promotes inflammation but impairs bactericidal activities during murine pneumococcal pneumonia. J Immunol. 2010;185(1):468–476. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gunzl P, Bauer K, Hainzl E, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of the PI3K pathway are mediated by IL-10/DUSP regulation. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88(6):1259–1269. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0110001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sahin E, Haubenwallner S, Kuttke M, et al. Macrophage PTEN regulates expression and secretion of arginase I modulating innate and adaptive immune responses. J Immunol. 2014;193(4):1717–1727. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munder M, Schneider H, Luckner C, et al. Suppression of T-cell functions by human granulocyte arginase. Blood. 2006;108(5):1627–1634. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-010389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ibanez-Vea M, Zuazo M, Gato M, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment: current knowledge and future perspectives. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 201. 8;66(2):113-123. doi: 10.1007/s00005-017-0492-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodriguez PC, Ochoa AC. Arginine regulation by myeloid derived suppressor cells and tolerance in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:180–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00608.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen W, Jiang J, Xia W, Huang J. Tumor-related exosomes contribute to tumor-promoting microenvironment: an immunological perspective. J Immunol Res. 2017;2017:1073947. doi: 10.1155/2017/1073947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]