Abstract

We present the case of a 69-year-old male, alcohol consumer, who was brought in by the ambulance for language impairment with onset two days prior to presentation in our hospital. Medical history revealed therapeutically neglected gout and colchicine allergy. On neurological exam, the patient presented predominantly motor aphasia with poor verbal fluency and anomic elements, mild right-sided hemiparesis 4/5 MRC and right-sided Babinski sign. Still, he was conscious and cooperative, and denied any recent head trauma or headache. Based on clinical picture, an acute cerebrovascular event was suspected, and the patient was hospitalized. However, brain CT revealed a late subacute subdural hematoma in the left hemisphere, with maximum thickness of 20 mm and displacement of median structures by 12 mm to the right (subfalcine herniation). The patient was then rapidly transferred to a Neurosurgical department for appropriate treatment and care.

Keywords:aphasia, subacute subdural hematoma, alcohol consumption.

Abbreviations (in alphabetical order)

BP Blood pressure

CSF Cerebrospinal fluid

CT Computer tomography

HDL High density lipoprotein

HR Heart rate

MRC Medical Research Council

rt-PA recombinant tissue Plasminogen Activator

SDH Subdural hematoma

INTRODUCTION

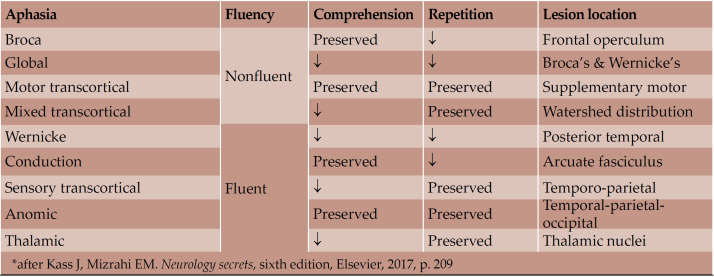

Aphasia represents an impairment in language production and/or comprehension, due to an acquired brain lesion (1). Aphasias are classically subdivided into anterior (motor/non-fluent), if the lesion is in the frontal lobe, and posterior (sensory/fluent), if the lesion is in the parietal or temporal lobes (2). Neurologists should be able to determine the type of aphasia, based on the following clinical features: (a) if speech is fluent or not, (b) if comprehension is preserved, and (c) if the patient is able to repeat (Table 1) (3).

Case presentation

A 69-year-old male was brought in by the ambulance for language impairment with onset two days prior to presentation in our hospital. Although conscious and cooperative, he presented poor spontaneous speech and had difficulties in finding his words. He was known with gout (affecting mainly the right lower limb), which he therapeutically neglected, and was allergic to colchicine. He denied smoking, but admitted chronic alcohol use, without specifying exactly how much he was drinking. Even so, this was important, alcohol consumption being known to favor development of high BP, atrial fibrillation and/or liver damage, thus being an important risk factor for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

Apart from palpable liver, general clinical exam was normal, with a BP of 130/80 mmHg and a HR of 73 bpm rhythmic. Neurological exam revealed predominantly motor aphasia with poor verbal fluency and anomic elements, mild right-sided hemiparesis 4/5 MRC and right-sided Babinski sign. He was able to execute simple commands, but not complex ones.

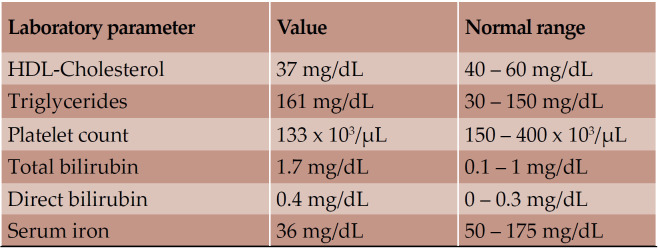

Based on clinical presentation, an acute cerebrovascular event was suspected, and the patient was hospitalized. Laboratory findings indicated slight dyslipidemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated bilirubin levels and hyposideremia (Table 2).

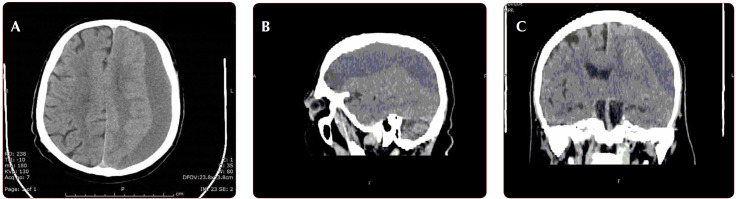

The cerebral CT scan showed the presence of a subdural hematoma in the left hemisphere, with maximum thickness of 20 mm and displacement of median structures by 12 mm to the right (subfalcine herniation) (Figure 1 A, B, C). Based on its density, the hematoma appeared to be late subacute.

The patient denied any recent head trauma or headache, and on admission, presented a GCS of 15. We then got in contact with the nearest Neurosurgery department and the patient was rapidly transferred for appropriate treatment and care.

DISCUSSION

Few points regarding the etiology of subdural hematomas (SDHs), which are worth to be mentioned, are further described.

The most common cause of SDH is head trauma, most often due to falls and sudden acceleration or deceleration movements of the head, with subsequent tearing of subdural bridging veins (4). In our case, the patient denied any head trauma prior to symptom development.

However, high risk factors for SDH have been noted, especially cerebral atrophy, which occurs in older patients or chronic alcohol consumers (as in the case of our patient). In cerebral atrophy, there is stretching of the subdural bridging veins, which can rupture even with minor trauma (5). As many as 58% of alcoholic patients may have cerebral atrophy, the degree of which correlates with duration of alcohol consumption (6). Likewise, decreased CSF pressure can cause downward displacement of the brain with subsequent traction of anchoring structures (bridging veins), followed by rupture and SDH (7). In one paper regarding the relation between SDH and low CSF pressure, spinal CSF leakage was described in seven out of 27 non-geriatric patients who underwent surgical intervention for chronic SDH (8). Conversely, in another study, SDH was found in eight out of 40 patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension and it was associated with male gender, headache worsening and neurologic deficits (9). Finally, in one study involving 93 patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension, of which 25 presented SDH, the following risk factors for SDH development were found: male gender, advanced age, longer clinical course and MRI presence of dural enhancement and venous distension sign (10).

Antithrombotic therapy has also been shown to favor SDH development. One case-control study compared 121 warfarin-treated patients who developed intracranial hemorrhage (of which 44 SDH cases) with 363 warfarin-treated controls, and found that a prothrombin time ratio above 2.0 was an independent risk factor for SDH development (11). Regarding antiplatelet therapy, it is unclear if aspirin increases the risk for SDH. In a metanalysis of nine trials, there was a 1.6-fold increased risk, which was not statistically significant. The incidence of SDHs did vary however with patient age, from 0.02 per 1000 patient-years in primary prevention trials of middle-aged individuals to 1-2 per 1000 patient- years in older patients with atrial fibrillation (12). Moreover, another meta-analysis of 11 trials comparing clopidogrel plus aspirin to aspirin alone, found that chronic dual antiplatelet therapy significantly increased the risk for SDH, although the absolute rate of SDH remained low (1.1 per 1000 patient-years) (13).

SDHs have also developed in the setting of thrombolysis. In the “Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction, Phase II pilot and clinical trial”, iv rt-PA (in combination with heparin and aspirin) was used for acute myocardial infarction at doses of 150 mg vs 100 mg. Intracranial bleeding was reported, particularly intracerebral hemorrhage (1.3% vs 0.4%), but also SDH (0.2% vs 0.1%) (14).

There is also the possibility of non-traumatic SDHs to be produced by the rupture of a cortical artery at the site of adhesion with dura mater. In Japan, a study of 116 patients with acute SDH found an incidence of 2.6% for spontaneous atraumatic SDHs, in all cases the source of bleeding being a cortical artery (15). A few cases of spontaneous SDH involving ruptured cortical artery aneurysms have also been described (16). Acute non-traumatic SDHs can rarely complicate meningiomas. In such cases, the prognosis is usually poor, with high mortality rates (17). Subdural hematomas can also complicate systemic cancer disease through dural metastases and obstruction of dural vessels by neoplastic cells (18). Finally, one case of spontaneous acute SDH due to cocaine abuse has also been described (19).

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

Financial support: none declared.

TABLE 1.

Types of aphasia and their characteristics*

TABLE 2.

Modified blood parameters

FIGURE 1 .

Unenhanced CT evaluation. A: axial plane; B: sagittal reconstructed; C: coronal reconstructed – Hypodense extra-parenchymal juxta-osseous collection with crescent shape, located in the left fronto-parieto-temporal region with mass effect on the cortical layer and left anterior ventricular horn, suggestive for subacute subdural hematoma

Contributor Information

Ioan-Cristian LUPESCU, Neurology Department, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania.

Vlad-Claudiu STEFANESCU, Radiology and Imaging Department, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania.

Ioana-Gabriela LUPESCU, Radiology and Imaging Department, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania; “Carol Davila“ University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania.

Adriana Octaviana DULAMEA, Neurology Department, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania; “Carol Davila“ University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allan HR, Martin AS, Joshua PK. Disorders of Speech and Language. In: Allan HR, Martin AS, Joshua PK. Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology. McGraw-Hill Educational. 2014. p. 487.

- 2.Morris J, Jankovic J. Aphasia. In: Morris J, Jankovic J. Neurological Clinical Examination, CRC Press. 2012. p. 91.

- 3.Arora G, Schulz PE. Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Neurology. In: Kass JS, Mizrahi EM. Neurology secrets – Sixth edition, Elsevier. 2017. p. 208.

- 4.Iliescu IA. Current diagnosis and treatment of chronic subdural haematomas. Journal of Medicine and Life. 2015;3:278–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty DL. Posttraumatic cerebral atrophy as a risk factor for delayed acute subdural hemorrhage. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;7:542–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lusins J, Zimberg S, Smokler H, Gurley K. Alcoholism and cerebral atrophy: a study of 50 patients with CT scan and psychologic testing. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1980;4:406–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1980.tb04840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim BW, Jung YJ, Kim MS, Choi BY. Chronic subdural hematoma after spontaneous intracranial hypotension: a case treated with epidural blood patch on c1-2. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;3:274–276. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2011.50.3.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck J, Gralla J, Fung C, et al. Spinal cerebrospinal fluid leak as the cause of chronic subdural hematomas in nongeriatric patients. J Neurosurg. 2014;6:1380–1387. doi: 10.3171/2014.6.JNS14550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai TH, Fuh JL, Lirng JF, et al. Subdural haematoma in patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension. Cephalalgia. 2007;2:133–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia P, Hu XY, Wang J, et al. Risk factors for subdural haematoma in patients with spontaneous intracranial hypotension. PLoS One. 2015;4:e0123616. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hylek EM, Singer DE.. Risk factors for intracranial hemorrhage in outpatients taking warfarin. Ann Intern Med. 1994;11:897–902. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-11-199406010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connolly BJ, Pearce LA, Kurth T, et al. Aspirin therapy and risk of subdural hematoma: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;4:444–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakheet MF, Pearce LA, Hart RG. Effect of addition of clopidogrel to aspirin on subdural hematoma: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Int J Stroke. 2015;4:501–505. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gore JM, Sloan M, Price TR, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral infarction, and subdural hematoma after acute myocardial infarction and thrombolytic therapy in the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Study. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction, Phase II, pilot and clinical trial. Circulation. 1991;2:448–459. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.2.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komatsu Y, Uemura K, Yasuda S, et al. (Acute subdural hemorrhage of arterial origin: report of three cases). No Shinkei Geka. 1997;9:841–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sung SK, Kim SH, Son DW, Lee SW. Acute spontaneous subdural hematoma of arterial origin. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;2:91–93. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.51.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hambra DV, Danilo de P, Alessandro R, et al. Meningioma associated with acute subdural hematoma: A review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5:S469–S471. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.143724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergmann M, Puskas Z, Kuchelmeister K. Subdural hematoma due to dural metastasis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1992;3:235–240. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(92)90095-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alves OL, Gomes O. Cocaine-related acute subdural hematoma: an emergent cause of cerebrovascular accident. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2000;7:819–821. doi: 10.1007/s007010070098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]