Abstract

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes, account for 72% of all global deaths, with 78% of all NCDs taking place in low- and middle-income countries. Among these four main groups of NCDs, CVDs are taking the highest death toll at 17.9 million or 44% of all NCD mortality. This paper suggests that the complex interplay of NCD risk factors and their underlying social and commercial determinants requires active cooperation with the private sector to bring about policy change, pool resources and generate innovative solutions by capitalizing on each partner’s strengths. However, such partnerships can only be successful if safeguards are in place to define the rules of engagement, align incentives to achieve shared public health objectives and manage potential conflicts of interest.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease (CVD), multi-stakeholder partnerships, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), private sector, WHO

Introduction

Public health challenges are complex, and addressing them requires complex solutions involving multiple actors. A multisectoral approach, entailing collaboration among multiple stakeholder groups (e.g., government, civil society, and private sector), as well as across different sectors (e.g., health, education, agriculture, finance, environment), is particularly important to prevent and control noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and their risk factors. A multi-stakeholder approach to addressing NCDs has been advocated for some time now as a means of raising awareness, establishing common goals, optimizing resources and avoiding the duplication of efforts for effective planning and implementation of NCD programmes (1). Although the engagement of multiple stakeholders in the public sector has not been disputed, the interactions between the public and corporate sectors have often been seen as less straightforward. However, the public sector’s limitations in comprehensively responding to the growing NCD epidemic, including the lack of resources and sometimes inefficient management, necessitates collaboration between the public and private sectors. This collaboration could potentially be a win-win, when the public sector delivers on its mandate to offer public good, and the private sector facilitates reaching this goal via mutually agreed roles and principles (2).

This perspective paper is intended to explore relevant opportunities of engagement with the private or corporate sector (the terms are used interchangeably in the paper) to address the growing NCD challenge. Clarity on some ethical and procedural issues of working with the corporate sector is critical as governments strive to achieve universal health coverage and to reach the NCD and the NCD-related targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

NCDs: a growing global health threat

NCDs, including cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes, are now the leading causes of death in all regions of the world except sub-Saharan Africa. In 2016, there were 56 million deaths worldwide from all causes. NCDs contributed 41 million to this mortality, with CVDs taking the highest death toll at 17.9 million (44% of all NCD deaths), followed by cancers (9 million deaths), respiratory diseases, including asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3.8 million deaths), and diabetes (1.6 million deaths). The four main groups of NCDs accounted for 72% of all global deaths in 2016 with 78% of all NCD deaths taking place in low-income and middle-income countries (3).

The increased prevalence of risk factors for CVDs and other chronic NCDs in low-income countries, including tobacco use, unhealthy diets, reduced physical activity and harmful use of alcohol, has contributed to a major shift of the NCD burden to the low-income, less developed regions once considered at a lower risk of NCDs. This shift has been accelerated by industrialization, globalization and urbanization, significantly influencing global changes in behaviors and lifestyle (4).

It is common knowledge that addressing CVDs and other NCDs in low-income and middle-income countries is particularly challenging due to poor infrastructure of national health systems, critical shortage of health care workers and other health system barriers to identifying and treating high-risk individuals (3). The complexity of the challenge is not confined to the health system bottlenecks alone. The underlying social determinants of NCDs, or the “causes of the causes,” as well as the economic and political structures and accompanying ideologies, are also shaping the adverse circumstances negatively influencing health (5).

In addition, the division of countries by income level masks the reality that there are subsets of vulnerable populations in every country or region, with different levels of exposure to NCDs and their risk factors. For example, countries experiencing rapid economic growth sometimes face an increase in the level of CVDs due to early adoption of more “affluent and modern lifestyles” (6).

Key risk factors of NCDs are strongly associated with patterns of consumption and unhealthy choices that are often influenced by the corporate sector. The commercial determinants of health, defined as “strategies and approaches used by the private sector to promote products and choices that are detrimental to health,” are increasingly being recognized as major drivers of the NCD epidemic. Corporate influence is usually exerted through four main channels: marketing, particularly, marketing to children and adolescents to increase the appeal and acceptability of unhealthy products; lobbying, which can negatively influence policies related to plain packaging and minimum drinking ages; corporate social responsibility strategies, which attempt to enhance the positive image of the corporate sector; and extensive supply chains, which help to extend the influence of the corporate sector all over the world. Hence, “the rise of NCDs is a manifestation of a global economic system that currently prioritises wealth creation over health creation”, and it has therefore become paramount to engage with the private sector in order to focus the fight against NCD risk factors and prevent CVDs (7).

To engage or not to engage? The relevance of the private sector in preventing and controlling CVDs

Engagement between the public and private sectors in preventing and controlling NCDs continues to be a topic of debate. In many low- and middle-income countries, prevalent political ideologies have led to public policies that prohibit or limit engagement with the private sector in all its forms. At the other extreme, in some countries powerful corporations have strong influence on the government health agenda. While more and more countries are opening up to the participation of non-state actors, including civil society and the private sector, the lack of prior experience with effective collaboration between the public and private sectors may still be a barrier (8).

Engagement with the private sector as provider of services

The evidence is mounting that prohibiting the private sector’s involvement in healthcare is very unlikely to succeed, and regulatory approaches are difficult to implement in low- and middle-income countries, where health care services are increasingly being delivered by private sector providers. For example, it is well documented that in Cambodia and India the vast majority of people turn to providers outside the public health system for services (9). In general, there is more acceptance of the private sector as a provider of services, since the private sector has a large and expanding role in health systems in low- and middle-income countries, often filling the gaps in the public sector.

As countries move toward universal health coverage as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, there is more room for targeted interventions in the private sector to address quality, improve efficiency and encourage provision of specific services to address the most pressing needs or conditions that may be beyond the basic universal entitlement. However, transition to UHC in pluralistic health systems facing the growing burden of chronic NCDs will require policies that recognize the links between the public and private sectors and the various roles they play in health system strengthening (10).

Broader engagement with industry to address CVDs and other NCDs

There has been less openness to engagement with industry due to concerns about the failure of large corporations to deliver social benefits on a sustainable basis (11). The complex interplay of NCD risk factors and their underlying social and commercial determinants throughout the life course brought the role of industry as a major driver of the NCD pandemic into the spotlight. In recognition of the role of industry in preventing NCDs, the 2011 United Nations General Assembly High-level Meeting Political Declaration called on the private sector to (I) follow the WHO recommendations and limit marketing of unhealthy foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children; (II) promote healthy diets and reformulate products for healthier options that are affordable; (III) ensure appropriate food labelling, including information on sugars, salt and fats; (IV) promote and create tobacco-free workplaces, workplace wellness programs and health insurance plans; (V) reduce the use of salt by the food industry to lower sodium consumption; and (VI) contribute to efforts to ensure access to and affordability of medicines and technologies to prevent and control NCDs (12).

To implement the recommendations of the Political Declaration specifically for CVDs, a wide range of industries within the private sector could be engaged: the food industry (producers, manufacturers, distributors, retailers and associations), pharmaceutical and health technology industries, sporting goods and fitness industries, and industries responsible for built environments. Other industries, including the media and information technologies, are also increasingly exerting both positive and negative influences on health, such as by encouraging sedentary lifestyles or by providing technological innovations (e.g., mobile technologies) to facilitate access to information and ensure remote monitoring (13).

In 2014, the second UN General Assembly High-Level Meeting noted that limited progress had been made toward the recommendations of the Political Declaration (14). This was partly due to the lack of clear governance structure to engage effectively and efficiently with industry in the area of NCDs. National governments are increasingly open to working with the private sector for political, economic or health goals, but there are inevitably concerns about the potential conflicts of interest, as well as about weak regulatory systems in many countries to ensure that partnerships do not compromise governments’ normative functions and broader development policy objectives.

On the other hand, irrespective of the fact that industry certainly has many opportunities to make a difference in public health, businesses need to see a clear benefit to their bottom line, as their ultimate responsibility is not to maximize the public good but to generate profits for their owners and shareholders. There are many arguments for private sector action on NCDs that fall into the following categories: profit motive (the drain of NCDs on country economies will threaten future profits), employees (minimizing NCDs helps keep the workplace healthy and reduce absenteeism), and ‘beyond business’ (doing the right thing strengthens the reputation of the private sector) (13). However, there is little agreement on how to address the potential risks and engage with the private sector.

From private sector engagement to multi-stakeholder partnerships: the new rules of the game

Awareness and willingness to engage with the private sector is the first step towards working with corporations. The private sector can draw on its business and scientific expertise, focusing on strong results-based operations, whereas the public sector can bring its experience in advancing public health interests and ensuring equity. Governments can also help align private sector incentives with national NCD strategies and plans through the use of taxes, subsidies and reduced compliance costs (15).

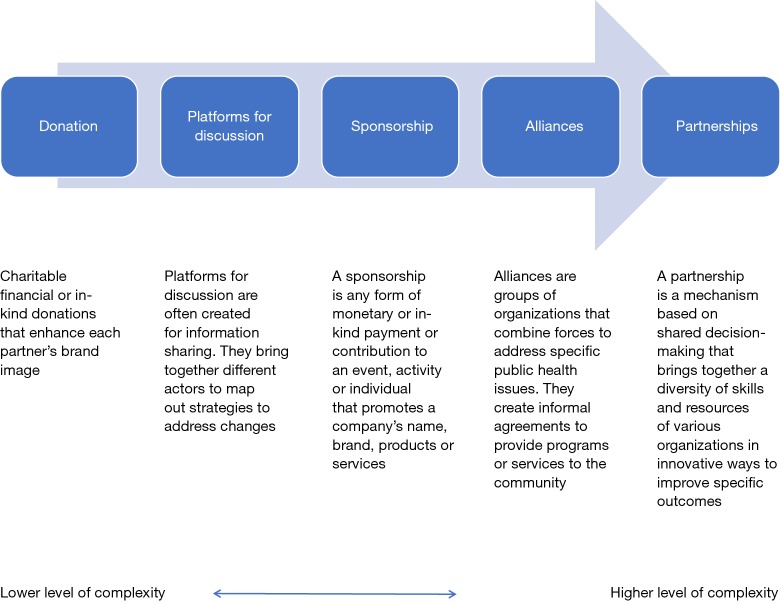

It is important to understand that the rules of engagement depend on the nature of the task and may take different forms. The term “partnerships” is often used loosely to define any kind of interaction, including corporate sponsorships and policy dialogues (16). We suggest that different forms of engagement be thought of as a continuum. For example, “a platform for discussion” is often created to share information and expertise, but in this case, there is no formal governance structure. Hence, this form of engagement is at the lower level of engagement, along with donations (Figure 1) (17). On the other hand, “partnerships” are more formal, high complexity engagements and include elements, such as having shared goals and agreed divisions of labor, resources and expertise; mutual accountability; and joint decision-making. Partnerships often require written agreements that specify the rights and obligations of each partner, the objectives of the partnership and how the partnership will be governed. Partnerships can only work if all participating parties benefit from the relationship (17).

Figure 1.

Forms of engagement with the private sector. Source: Multisectoral Partnerships Task Group [2013]. Public-Private Partnerships with the Food Industry.

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) in global public health are not new. They have been appearing since the early 2000s. PPPs have been defined as “an arrangement when at least one representative from government and one from the private, for-profit sector work together to achieve a shared public health objective based on some degree of shared decision-making”. Most of them (e.g., GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, Global Fund to Fight HIV/AIDs, Malaria and Tuberculosis) were set up as new structures outside UN auspices to address narrowly defined health issues and disease priorities by ensuring access to medicines, vaccines and diagnostics to treat them (17).

However, the complexity of the NCD challenge requires a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach and a broader understanding of partnerships involving multiple stakeholders across sectors, such as civil society, the private sector, the public sector, academia, philanthropies, and the media. Multi-stakeholder partnerships to tackle NCDs are important to bring about policy change, pool resources, and generate innovative solutions by capitalizing on each partner’s strengths.

Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which now includes an NCD target (SDG 3.4) of one third reduction of premature mortality from NCDs and enhancing mental health and well-being, acknowledges the interconnected nature of all development goals and stresses the role of the Global Partnership (Goal 17) to implement the Agenda (18).

In the post-SDG era, should the rules of engagement in partnerships be redefined to address NCDs? What should be the appropriate roles of all stakeholders, including the private sector, in preventing NCDs, while simultaneously avoiding any potential conflicts of interest and misleading expectations?

To ensure successful implementation of the 2030 Agenda, OECD proposes a 10-step policy framework “to make partnerships effective coalitions for action” (Box 1) (19). This framework could equally be applied to facilitate multi-stakeholder partnerships for NCDs.

As for private sector engagement, Michael Porter introduced a new approach for businesses to highlight the importance of creating shared value, defined as “policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company which simultaneously advance the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates” (20). This approach sounds like a win-win. However, it underscores the need for focused leadership and collaboration between public and private sectors, and currently many low- and middle-income countries lack the capacity and governance structures to coordinate multi-stakeholder and multisectoral partnerships to address NCDs. WHO and other United Nations institutions have an important role to play in assisting countries to select, screen and approve the best private partners, to identify the actual substance or content of the interaction, and to define the form of collaboration to avoid fragmentation of long-term development policies and ensure recipients remain in the driver’s seat (16).

WHO’s engagement with non-state actors

Understanding how to align incentives and build cooperation is critical to success. WHO started to elaborate its thinking about PPPs in the late 1990s. In 1998, after the election of Dr. Gro Harlem Brundtland as WHO’s Director-General, engagement with the corporate sector became an important part of the organizational policy (16). Collaboration with the private sector has grown in importance with the growing political movement to address NCDs. The new WHO Director-General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has also signalled the openness of WHO to engage with industry while safeguarding its impartiality and ensuring WHO’s transparency regarding the organization’s relationship with the corporate sector, including the guiding principles of such relationships.

WHO believes that it is not possible to align incentives with the tobacco or arms industries, and therefore the agency does not engage with these industries in any form. There are large volumes of well-documented evidence revealing the tobacco industry’s efforts to undermine not only the efforts of WHO to control tobacco use, but the reputation of the organization itself (16).

WHO Global Coordination Mechanism as an innovative platform for multi-stakeholder engagement

In 2014, the WHO Global Coordination Mechanism (GCM/NCD) was established by WHO Member States precisely with the aim of addressing the need for multisectoral and multi-stakeholder response to NCDs. The GCM/NCD works to “enhance coordination of activities, multi-stakeholder engagement and action across sectors at the local, national, regional and global levels” (21). The strategic foundations for the establishment of the GCM/NCD were laid by the two landmark United Nations high-level meetings on NCDs in 2011 and 2014.

Currently, GCM/NCD participants include over 350 partners, comprising all WHO Member States, United Nations funds, programs and agencies, other intergovernmental organizations and non-state actors (NGOs, academia, philanthropic foundations and the private sector). These partners engage with the GCM/NCD through a variety of channels: working groups, global multi-stakeholder dialogue meetings, an extensive network of communities of practice, webinars, integrated country initiatives, and knowledge dissemination and advocacy at global, regional and country levels. The GCM/NCD also works to accelerate action for the achievement of the nine voluntary global targets of the Global NCD Action Plan and attain SDG target 3.4 and other NCD-related targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The rules of engagement with the GCM/NCD are guided by the WHO Framework of Engagement with Non-State Actors (FENSA), a resolution adopted by the World Health Assembly in 2016. The FENSA resolution recognizes the risk of potential conflicts of interest from engagement with industry, including undue influence in setting or applying policies, norms and standards. FENSA proposes mechanisms to avoid these risks through due diligence, risk assessment, transparency and accountability. FENSA also stresses the importance of engaging with non-State actors when such collaboration demonstrates a clear benefit to public health and is in line with WHO’s constitution, mandate and General Programme of Work (22). So far, the GCM/NCD has been a successful engagement model at the global level, but there is a need of replicating it at country level to accelerate the implementation of national NCD responses and meet SDG 3.4 and other related targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Conclusions

The public health community may not always be at ease working with the private sector, and more research will be needed to continue refining modes of engagement and managing conflicts of interest. It will also be important to continue putting safeguards in place, such as monitoring and accountability systems and transparent communication and agreements. In this regard, in an era of proliferation of global health actors and complicated global health architecture, strengthening WHO’s influence as the only agency with an explicit mandate to ensure “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition” for all people, is paramount (23).

Box 1 Policy framework for post-2015 partnerships.

| 1. Secure high-level leadership |

| 2. Ensure partnerships are country led and context specific |

| 3. Avoid duplication of efforts and fragmentation |

| 4. Make governance inclusive and transparent |

| 5. Apply the right type of partnership for the challenge |

| 6. Agree on principles, targets, implementation plans and enforcement mechanisms |

| 7. Clarify roles and responsibilities |

| 8. Maintain a clear focus on results |

| 9. Measure and monitor progress towards goals and targets |

| 10. Mobilize the required financial resources and use them effectively |

Source: Development co-operation report 2015: Making partnerships effective coalitions for action. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Acknowledgements

The technical contribution of Dina Tadros to early drafts of this paper is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the World Health Organization.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Salunke S, Lai DK. Multisectoral approach for promoting public health. Indian J Public Health 2017;61:163-8. 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_220_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishtar S. Public-private partnerships in health – a global call to action. Health Res Policy Syst 2004;2:5 10.1186/1478-4505-2-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Global Health Estimates 2016: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and Region, 2000-2016. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeates K, Lohfeld L, Sleeth J, et al. A global perspective on cardiovascular diseases in vulnerable populations. Can J Cardiol 2015; 31:1081-93. 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.06.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raphael D. The Social Determinants of Non-communicable Diseases: A Political Perspective. In: McQueen DV. editor. Global Handbook on Noncommunicable Diseases and Health Promotion. 2013:95-113. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand SS, Yusuf S. Stemming the global tsunami of cardiovascular disease. Lancet 2011;377:529-32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62346-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kickbusch I, Allen L, Franz C. The commercial determinants of health. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e895-6. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30217-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett S, Hanson K, Kadama P, et al. Discussion Paper 2: Working with non-state sector to achieve public health goals. World Health Organization, 2005.

- 9.Forsberg BC, Montagu D, Sundwell J. Moving towards in-depth knowledge on the private sector in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan 2011;26 Suppl 1:i1-3. 10.1093/heapol/czr050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McPake B, Hanson K. Managing the public-private mix to achieve universal health coverage. Lancet 2016; 388:622-30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00344-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montagu D, Goodman C. Prohibit, constrain, encourage, or purchase: how should we engage with the private health-care sector? Lancet 2016;388:613-21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30242-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations General Assembly A/RES/66/2. UN High-level Political Declaration on the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Paragraph 44, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hancock C, Kingo L, Raynaud O. The private sector, international development and NCDs. Global Health 2011;7:23. 10.1186/1744-8603-7-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United Nations General Assembly A/RES/68/300. Outcome document of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the comprehensive review and assessment of the progress achieved in the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. Paragraph 26, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen L, Bloomfield A. Engaging the private sector to strengthen NCD prevention and control. Lancet 2016;4:e897-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ollila E. Global Health-related Public-Private Partnerships and the United Nations. Globalism and Social Policy Programme Policy Brief, 2003.

- 17.Multisectoral Partnerships Task Group. Public-Private Partnerships with the Food Industry. Discussion Paper, 2013. Available online: https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2015/ppptg-discussion-paper.PDF. Accessed 21 June 2018.

- 18.United Nations General Assembly. A/RES/70/1. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 2015.

- 19.Development co-operation report 2015: Making partnerships effective coalitions for action. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2015; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/dac/development-co-operation-report-20747721.htm. Accessed 21 June 2018.

- 20.Porter M, Kramer MR. Creating shared value – how to reinvent capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harv Bus Rev 2011;89:62-77. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Assembly. A67/14 Add1. Terms of reference of the global coordination mechanism on the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. 2014.

- 22.World Health Organization. Framework of Engagement with non-State Actors (FENSA). Sixty-Ninth World Health Assembly, 2016. May 28, 2016 A69/10. Available online: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_R10-en.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 9 May 2018.

- 23.Constitution of the World Health Organization, 1948. Available online: www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf. Accessed 9 May 2018.