Abstract

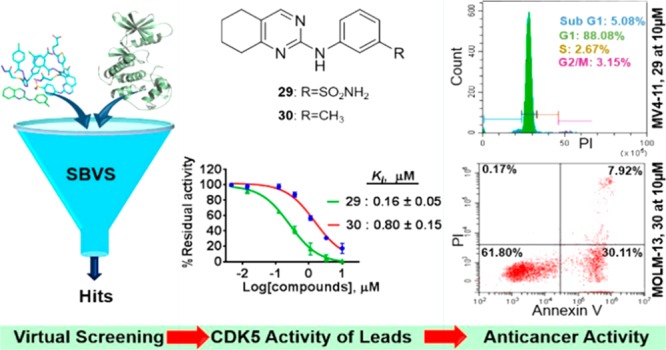

Specific abrogation of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) activity has been validated as a viable approach for the development of anticancer agents. However, no selective CDK5 inhibitor has been reported to date. Herein, a structure-based in silico screening was employed to identify novel scaffolds from a library of compounds to identify potential CDK5 inhibitors that would be relevant for drug discovery. Hits, representatives of three chemical classes, were identified as inhibitors of CDK5. Structural modification of hit-1 resulted in 29 and 30. Compound 29 is a dual inhibitor of CDK5 and CDK2, whereas 30 preferentially inhibits CDK5. Both leads exhibited anticancer activity against acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells via a mechanism consistent with targeting cellular CDK5. This study provides an effective strategy for discovery of CDK5 inhibitors as potential antileukemic agents.

Keywords: AML, apoptosis, CDK5, CDK5 inhibitors, cell cycle, virtual screening

A growing body of evidence supports cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) as highly attractive molecular targets for the development of anticancer drugs.1−3 CDKs are members of the serine/threonine family of protein kinases with the primary functions of regulating the cell cycle and transcription.1,4 The majority of these CDKs are highly deregulated in human malignancies, and a number of recently discovered small-molecule CDK inhibitors, including palbociclib, abemaciclib, and ribociclib, are instrumental in target validation and drug development.1,5,6 This has driven significant research efforts to exploit CDKs for the development of a new generation of targeted cancer therapeutic agents.

CDK5 is an atypical member of the mammalian CDKs, which has long been known for its role in the central nervous system.7,10 It has been attracting considerable attention as its selective inhibition could offer an exciting therapeutic benefit in clinical oncology.7,10 CDK5 is unique within its family members because it is activated by the noncyclin proteins, p35 and p39, and their respective truncated products, p25 and p29.8 These activators are abundantly expressed in the brain, making CDK5 an important regulator of the development of the central nervous system (CNS) and its various functions, including neuronal migration, and survival.9 However, CDK5 is a well-established kinase that mediates the pathophysiology of common neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.9 Recently, aberrant expression of CDK5 and its activators has been observed in multiple solid and hematological malignancies,10 but not in healthy tissues.11,12 In most cancers studied so far, there is strong evidence supporting the specific targeting of CDK5 as a viable strategy for the discovery of anticancer therapeutic agents that possibly circumvent the apparent drawbacks of the currently available therapies; in particular, the lack of efficacy, drug resistance, and toxicity to healthy tissues.13,14 However, the discovery of pharmacologic inhibitors of CDK5 with sufficient potency and selectivity remains a highly challenging task. This is linked to a high amino-acid sequence similarity between CDK5 and other CDKs, particularly CDK2, where the two kinases differ in their ATP binding pockets by only two amino-acid residues.15,16 Roscovitine (seliciclib) and dinaciclib are currently the prototype examples of inhibitors in clinical trials that target multiple kinases including CDK5 (Figure S1). This in turn leads to serious off-target toxicities. Several phase I and phase II clinical trials in cancer patients have been completed for these inhibitors.10 A recent Phase III clinical trial demonstrated the potential anticancer activity of dinaciclib.17 There are currently no specific CDK5 inhibitors at any stage of drug development despite very strong demand to investigate and unravel the role of CDK5 in the growth and proliferation of cancer cells.

In this study, we report the identification of CDK5 inhibitory molecular scaffolds using structure-based virtual screening and optimization. Evaluation of 28 virtual screening hits (Table S2) with our in-house CDK5 biochemical assay (Table S1) revealed three hits with moderate inhibition, and their antiproliferative effects were confirmed in MV4-11 and MOLM-13 AML cell lines. Medicinal chemistry optimization of a selected hit generated a series of compounds, which led to the rapid identification of two lead molecules, 29 and 30, which were confirmed to target CDK5 in MV4-11 AML cells by Western blot analysis. The results demonstrated a successful application of structure-based approach in identifying CDK5-targeting scaffolds that can form the basis for medicinal chemistry optimization.

In this study, initially, the ChemBridge library containing 1.1 million drug-like molecules was screened using the Glide docking module of the Schrödinger suite. The crystal structure of active CDK5 protein bound with its ligand roscovitine (PDB ID: 1UNL) was used as a template for the screening. Figure 1A is the schematic representation of the screening process. The ligand library was first screened using Glide high throughput virtual screening (HTVS), which was subsequently followed by Glide standard precision (SP) and Glide extra precision (XP) (Supporting Information). The top 2700 molecules from the XP screening were filtered for exclusion of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) and chosen for inspection. These molecules were clustered based on their calculated tanimoto coefficient using the 2D fingerprint in Schrödinger Canvas 2.8. Subsequently, based on the analysis of physicochemical properties, docking scores, and consideration of Lipinski’s rule of five, 250 molecules were chosen for further analysis. From these 250 molecules, 28 were selected based on visual inspection for biochemical kinase screening at 10 μM against CDK5 using the ADP-Glo kinase assay (Table S1). The compounds were found to inhibit CDK5 with varying strength encompassing moderate (>60%) to weak (<60%) inhibitory activities (Table S2). Ki values were further determined for the compounds that showed ≥60% inhibition. The compounds hit-1, hit-2, and hit-3, the representative of three chemical classes, i.e., N-phenyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinazolin-2-amine, N-(3-(pyrrolidin-1-ylmethyl)phenyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide, and N-phenyl-6,7-dihydro-5H-cyclopenta[d]pyrimidin-2-amine (Figure 1B), inhibited CDK5 with Ki values of 0.88, 2.03, and 1.72 μM, respectively. These compounds were profiled against other members of the CDK family including CDKs 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, and 9 in which hit-1 showed higher potency and selectivity for CDK5 compared to the other two (Figure 1C). Finally, their antiproliferative activities against MV4-11 and MOLM-13 AML cells were confirmed (Figure 1D). To provide additional insight into our findings, the binding modes of the three hits, roscovitine and an inactive compound hit-16 as a negative control were studied using Glide XP docking. Hit-1 forms two hydrogen bonds with the amino and carbonyl of Cys83 residue in the hinge region of CDK5 (Figure 2A). A similar type of interaction was observed with hit-2 and hit-3 (Figure S2). Hit-16, however, does not reach the hinge region, rather it forms a hydrogen bond with Asn144 (Figure 2A). The hits have been found to exhibit a similar binding mode as roscovitine, with the exception that the latter formed one extra interaction with Gln130, which is a likely explanation for its enhanced inhibitory activity against CDK5 (Figure S1, IC50 of 0.27 μM for roscovitine vs 1.76 μM for hit-1).

Figure 1.

Hit identification. (A) Schematic representation of the high throughput virtual screening steps. (B) CDK5 inhibition potency of the three hits and chemical structures of inactive hit-16. (C) Selectivity for CDK5 over other members of CDK family at a concentration of 10 μM. (D) Antiproliferative effects in MOLM-13 and MV4-11 leukemia cell lines. GI50 was determined by a 72 h resazurin assay and represents mean ± SD of three independent experiments. 5/p25, CDK5/p25; 1/B1, CDK1/Cyclin B1; 2/A, CDK2/Cyclin A; 4/D1, CDK4/Cyclin D1; 6/D3, CDK6/Cyclin D3; 7/HMAT, CDK7/Cyclin H/MAT1; 9/T1, CDK9/Cyclin T; GI50, the concentration for 50% inhibition of cell proliferation. Ki values were obtained from three independently repeated experiments.

Figure 2.

Binding modes of compounds with CDK5/p25 (PDB: 1UNL) (A–C) and CDK2/A (PDB: 4NJ3) (D). (A) Hit-1 (green) and hit-16 (yellow, Table S2), (B) roscovitine (gray), (C) 29 (blue) and 30 (pink); (D) 29 and 30 in CDK2. All representations are predicted by Glide XP docking in Schrödinger suite.

Next, the chemical scaffold N-phenyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinazolin-2-amine of hit-1 was selected for further optimization due to its better selectivity profile and potency toward CDK5. Hit-1 is a topological structure of quinazoline, which resulted in EGFR inhibitors including gefitinib and erlotinib. It also consists of an aminopyrimidine moiety that has been an important scaffold to generate kinase inhibitors, e.g., abemaciclib, imatinib, etc.2 However, the kinase activity of our scaffold has not been reported so far. Therefore, exploration of the current scaffold may lead to the identification of potent and selective inhibitors. The docking of hit-1 to CDK5 revealed the presence of unoccupied space around its aniline and tetrahydroquinazoline rings. This enabled substitution with various functional groups that can potentially target amino acid residues in the immediate vicinity (Figure 2A). For example, Asp84 and Asp86 in CDK5 can be targeted by introducing substitutions around the aniline ring, and Ile10 and Phe80 can be targeted by modifying the cyclohexane moiety. Moreover, our previous studies of a class of N-phenyl-4-(thiazol-5-yl)pyrimidin-2-amine derivatives revealed that meta-substitution, e.g., m-SO2NH2 and m-NO2, on the aniline ring was important for CDK2 inhibition.18 Since CDK5 has high sequence similarity with CDK2, these substituents might facilitate CDK5 inhibitory activity. Therefore, in the current study, we explored the SAR through the synthesis of compounds 29–45 (Table 1 and SI), with different groups at the ortho, meta, and para positions of the aniline ring. The compounds were first screened for their % inhibition against CDK5/p25 and CDK2/A at 10 μM. Compounds achieving ≥70% inhibition of CDK5/p25 were then chosen for Ki determination and cellular antiproliferative activity study. Interestingly, compounds with meta-substituent aniline at the 2C-position of 5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinazolin; e.g. 29 (R2 = SO2NH2), 30 (R2 = CH3), 31 (R2 = OCH3), 32 (R2 = NO2), and 33 (R2 = CH2CH3) inhibited CDK5 in a range of 78–98% (Table 1), with the exception of 34 (R2 = CF3), which shows little activity. All other derivatives with ortho- or para-substituted aniline, e.g., 35–39 and 41–44 showed low activity against both enzymes. However, 40 (R1 = CH3) and 45 (R3 = CH3) achieved 82% and 77% inhibition against CDK5, respectively. Overall, there is a similar trend of CDK5 and CDK2/A inhibition, and the meta-substituted aniline was favorable for both CDK5 and CDK2 inhibition. Further evaluation of the selected compounds (% inhibition ≥70%) showed that 29, 30, and 40 inhibited CDK5 activity potently with Ki value ≤1 μM, whereas the rest (31–33 and 45) has a Ki value ≥1 μM (Table 2). Compound 29 was identified as the most potent inhibitor with a Ki = 0.16 μM. However, 29 was not selective for CDK5/p25 over CDK2/A.

Table 1. Structure–Activity Relationships of N-Phenyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinazoline-2-amine Derivatives.

| % inhibition

(10 μM) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd | R1 | R2 | R3 | 5/p25 | 2/A |

| 29 | H | SO2NH2 | H | 98 | 95 |

| 30 | H | CH3 | H | 87 | 72 |

| 31 | H | OCH3 | H | 85 | 93 |

| 32 | H | NO2 | H | 83 | 87 |

| 33 | H | CH2CH3 | H | 78 | 39 |

| 34 | H | CF3 | H | 5 | 7 |

| 35 | CH3 | NHSO2CH3 | H | 63 | NDa |

| 36 | OCH3 | H | H | 22 | 2 |

| 37 | OCH2CH3 | H | H | 4 | 2 |

| 38 | OCF3 | H | H | 9 | NAb |

| 39 | CF3 | H | H | 10 | 8 |

| 40 | CH3 | H | H | 82 | 54 |

| 41 | OCH3 | H | Cl | 45 | NAb |

| 42 | OCH3 | F | OCH3 | 21 | 7 |

| 43 | H | H | OCH3 | 1 | 3 |

| 44 | H | H | CF3 | 6 | 7 |

| 45 | H | H | CH3 | 77 | 58 |

Not determined.

Not active.

Table 2. CDK Selectivity Profiles.

| CDK

inhibition Ki,a μM |

cytotoxicityb (GI50), μM | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd | 5/p25 | 1/B | 2/A | 2/E | 4/D1 | 6/D3 | 7/HMAT1 | 9/T1 | MV4-11 |

| 29 | 0.16 | 2.61 | 0.27 | 1.0 | > 5 | 3.01 | >5 | 1 | 2.55 ± 0.14 |

| 30 | 0.80 | 2.36 | 3.32 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | 3.29 ± 0.17 |

| 31 | 1.01 | >5 | 1.11 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | 2.28 ± 0.00 |

| 32 | 1.26 | >5 | 1.10 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | 3.50 ± 0.70 |

| 33 | 1.23 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | 2.60 ± 0.11 |

| 40 | 0.99 | >5 | 4.12 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >10 |

| 45 | 1.44 | >5 | 4.54 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | >5 | 6.00 ± 0.40 |

The Ki values show the average of at least two experiment. % residual activity for Ki values >5 is presented in Table S5.

Cytotoxicity (GI50) was determined by a 72 h resazurin assay and represents mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Compound 30 inhibited CDK5/p25 with a Ki value of 0.8 μM and exhibited more than 4-fold increase in potency for CDK5/p25 over CDK2/A (p < 0.05, Table S3). Interestingly, all these compounds demonstrated considerable selectivity for CDK5/p25 over CDK2/E as well as other CDKs such as 1/B, 4/D1, 6/D3, 7/H, and 9/T1. The compounds were tested for their antiproliferative activity in MV4-11 cells, showing GI50 in the range of 2.28–6.0 μM, with the exception of 40 (GI50 > 10 μM). Compounds 29 (most potent) and 30 (most selective) were selected for further studies of their binding modes and anticancer mode of action. To understand the difference in potency and selectivity observed with 29 and 30, we analyzed the binding modes of 29 and 30 in CDK5/p25 (PDB: 1UNL) and CDK2/A (PDB: 4NJ3). It was observed that both compounds bind with Cys83 at the hinge region of CDK5 via two hydrogen bonds as shown earlier by hit-1. However, 29 formed one extra hydrogen bond with Asp84 of CDK5, which might account for the improved potency when compared to hit-1 and 30 (Figure 2C). It also showed similar binding mode in CDK5 and CDK2/A, which correlated with comparable potencies against both enzymes (Table 2). In contrast, 30 in CDK2/A2 formed a hydrogen bond with Val64 (Figure 2D). This finding is in agreement with the in vitro results where 30 was found to be more potent for CDK5/p25 over CDK2/A. In addition to these, the subtle differences in the conformation and plasticity of the active site of the two enzymes might also play a role.19

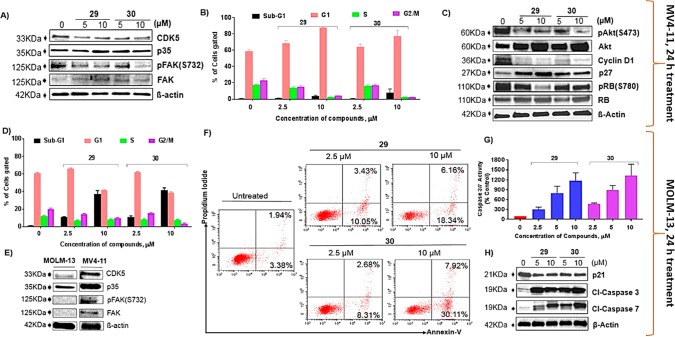

Following this, target confirmation study in cellular context was undertaken for 29 and 30 by monitoring the level of phosphorylation status of FAK at Serine 732.20,21 This was assessed in MV4-11 AML cells using Western blot analysis. Incubation of the cells with 29 or 30 for 24 h suppressed the level of FAK phosphorylation (Figure 3A) in a concentration-dependent manner. Our data confirmed the ability of these compounds to inhibit cellular CDK5 kinase activity. Next, the antiproliferative effects of 29 and 30 were measured with cell viability assays after 72 h of treatment by employing resazurin and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) in leukemia and adherent (solid tumor) cell lines, respectively. Of note, both compounds showed potent antiproliferative activity against MOLM-13 and MV4-11 AML cells with GI50 values ranging from 2.16 to 3.29 μM (Table S4). As both cell lines are carrying FLT3-ITD mutation, 29 and 30 were subsequently tested in FLT3-ITD kinase assays, showing IC50 = 1.48 μM for 29 and >10 μM for 30. In addition, we have shown that both compounds did not target cellular FLT3 using Western blot analysis (Figure S3). However, in this type of AML cells, the high proliferation rate induced by oncogenes, e.g., MYC or FLT3-ITD can lead to the phenomenon called replicative stress.22 This in turn causes a high degree of genomic instability and upregulation of DNA damage repair machineries including ataxia–telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and p53, both of which are known targets of CDK5. This might be the cause of preferential sensitivity of MV4-11 and MOLM-13 cells toward the inhibition of CDK5 compared to solid cancer cells and FLT3 wild-type AML cells lines (Table S4). Nevertheless, their activity in solid tumor cell lines was comparable to that of roscovitine.23 The advantage of our compounds over roscovitine is their improved selectivity for CDK5 over other members of the CDK family.

Figure 3.

Primary target confirmation and anticancer mechanisms of 29 and 30. (A) Compounds 29 and 30 inhibit CDK5 in MV4-11 cells. (B,D) Effects of 29 and 30 on cell cycle progression in MV4-11 and MOLM-13 cell lines, respectively. (C) Molecular mechanisms of cell cycle arrest by 29 and 30 in MV4-11 cells. (E) Comparison of CDK5 and related proteins expression in MOLM-13 and MV4-11 cells. (F) Induction of apoptosis in MOLM-13 cells. (G) Caspase 3/7 activity in MOLM-13 cells. (H) Western blot analysis showing mechanism of cell death in MOLM-13 cells. All the data were generated from at least two independently repeated experiments, and numerical data in panels B, D, and G represent the mean value.

In the study of potential anticancer mechanisms of 29 and 30, we observed that the compounds, at concentrations of 2.5 and 10 μM, arrested MV4-11 cells in the G1-phase of the cell cycle (Figure 3B) after 24 h of treatment. Interestingly, both compounds caused a substantial accumulation of MOLM-13 cells in sub-G1 phase at the higher concentration, i.e., 10 μM (Figure 3D), and this is consistent with the effects of CDK5 inhibition in other cancers.10 In Western blot analysis, we found that 29 and 30 reduced the protein levels of pAkt (S473), pRB(S780), and Cyclin D1 and increased that of p27KIP1 in MV4-11 cells (Figure 3C) and MOLM-13 cells (Figure S4), which is consistent with the observed G1 cell cycle effects. Our findings are supported by literature reports that CDK5 knockout/down by siRNA/shRNA abrogated the phosphorylation of Akt at S473, leading to G1 cell cycle arrest in the cancer of prostate, breast, and ovary.10,24 Intriguingly, the PI3K-Akt pathway has been established as the primary mediator of an early adaptation and resistance of cancer cells during the clinical use of CDK4/6 inhibitors,1,7 suggesting CDK5 inhibitor as potential new therapy to overcome this problem. Furthermore, AnnexinV and PI double staining shows that both compounds increased the proportion of apoptotic MOLM-13 cells (Figure 3F) but had little effect on the MV4-11 cells (Figure S5). Similarly, other groups reported that knockout/down of CDK5 through SiRNA/shRNA caused apoptosis in cells derived from solid tumors including breast, prostate, and ovarian cancers.7,10,25 However, given the very high genetic and mutational similarity between the two leukemic cell lines, it was surprising to see such a discrepancy in response to 29 and 30. A very recent study demonstrated AML cells with low level FAK expression are more susceptible to killing by suppressed FAK activity.24 Similarly, we and others26 found that MOLM-13 cells express a low level of FAK protein (Figure 3E) compared to MV4-11 cells, and this could be one of the reasons for the increased susceptibility of MOLM-13 cells to killing by 29 and 30. Finally, the molecular mechanisms of 29 and 30 mediated killing effects were analyzed in MOLM-13 cells. Past evidence revealed caspase activation as one of the major mechanisms of apoptosis induction by CDK5 inhibition,23,25,27 and thus, we assessed caspase activity by Apo-ONE Homogeneous Caspase-3/7 Glo Assay. Treatment of MOLM-13 cells with 29 or 30 at the concentrations shown for 24 h resulted in a robust increase in caspase 3/7 activity (Figure 3G). Moreover, caspases 3 and 7 were activated as demonstrated by the massive increase in the cleaved (Cl) caspase 3 and 7 bands in Western blot analysis (Figure 3H). This might be linked to down regulation of p21CIP1 protein (Figure 3H) following CDK5 inhibition by 29 and 30. It has recently been reported that p21CIP1 appears to play an important role in protecting cells from apoptosis beyond its conventional tumor suppressive role. In the cytoplasm, p21CIP1 forms complexes with antiapoptotic elements such as procaspase 3 and renders them inactive to ensure the survival of cancer cells.28,29 Thus, inhibition of p21CIP1 releases pro-caspases from the complex resulting in cell death. Previously, downregulation of p21CIP1 has been observed in a mouse model of thyroid carcinoma in which CDK5 kinase activity has been suppressed.10 This might support that inactivation of the PI3K-Akt pathway as a result of CDK5 inhibition caused a downregulation of p21CIP1, which in turn activates caspases to trigger apoptosis. Our findings in the CDK5-targeted cellular mode of action are consistent with what others had reported using CDK5 knockout/down cells in colorectal, prostate, ovarian, and breast cancers.7,10,20,25,27

In summary, we have employed the approaches of structure-based in silico screening and medicinal chemistry optimization to identify a new class of CDK5 inhibitors. The initial hit-1, hit-2, and hit-3 inhibited CDK5/p25 with Ki values of 0.88–2.03 μM. Further structure-guided design and optimization of the hit-1 resulted in a series of 5,6,7,8-tetrahydroquinazolin derivatives that enabled us to establish the structure–activity relationship. Lead compounds 29 and 30 exhibited potent activity against CDK5/p25, and the latter also demonstrated an appreciable selectivity for CDK5/p25 over other members of the CDK family. Cellular mechanistic investigation confirmed that 29 and 30 targeted cellular CDK5 and caused cell cycle arrest and substantial apoptotic cell death in AML cells. Taken together, this study describes an effective strategy to identify CDK5 inhibitors that have potential to be developed as antileukemic agents.

Acknowledgments

N.Z.K. and J.L.L. acknowledge the support from the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- ATM

ataxia–telangiectasia mutated

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- GSK-3β

glycogen synthase kinase-3 β

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HTVS

high throughput virtual screening

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PAINS

pan assay interference compounds

- RB

retinoblastoma protein

- SP

standard precision

- XP

extra precision

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00029.

Experimental procedure for the synthesis and characterization of compounds; molecular modeling methods; procedures for biological evaluation; additional tables and figures (PDF)

Author Contributions

† These authors contributed equally to this work. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Asghar U.; Witkiewicz A. K.; Turner N. C.; Knudsen E. S. The history and future of targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2015, 14, 130–146. 10.1038/nrd4504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malínková V.; Vylíčil J.; Kryštof V. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors for cancer therapy: a patent review (2009 – 2014). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2015, 25, 953–970. 10.1517/13543776.2015.1045414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyressatre M.; Prével C.; Pellerano M.; Morris M. C. Targeting Cyclin-Dependent Kinases in Human Cancers: From Small Molecules to Peptide Inhibitors. Cancers 2015, 7, 179–237. 10.3390/cancers7010179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casimiro M. C.; Crosariol M.; Loro E.; Li Z.; Pestell R. G. Cyclins and Cell Cycle Control in Cancer and Disease. Genes Cancer 2012, 3, 649–657. 10.1177/1947601913479022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCain J. First-in-Class CDK4/6 Inhibitor Palbociclib Could Usher in a New Wave of Combination Therapies for HR+, HER2– Breast Cancer. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 40, 511–520. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hortobagyi G. N.; Stemmer S. M.; Burris H. A.; Yap Y.-S.; Sonke G. S. Ribociclib as First-Line Therapy for HR-Positive, Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1738–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1609709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo K.; Bibb J. A. The Emerging Role of Cdk5 in Cancer. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 606–618. 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhavan R.; Tsai L.-H. A decade of CDK5. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 749–591. 10.1038/35096019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes J. P.; Agostinho P. Cdk5: Multitasking between physiological and pathological conditions. Prog. Neurobiol. 2011, 94, 49–63. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenjisa J. L.; Tadesse S.; Khair N. Z.; Wang S. CDK5 in oncology: recent advances and future prospects. Fut. Med. Chem. 2017, 9, 1995–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami E.; Gao J.; Dogrusoz U.; Gross B. E.; Sumer S. O. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: An Open Platform for Exploring Multidimensional Cancer Genomics Data. Cancer Discovery 2012, 2, 401–404. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes D. R.; Yu J.; Shanker K.; Varambally R.; Ghosh D. ONCOMINE: A Cancer Microarray Database and Integrated Data-Mining Platform. Neoplasia. 2004, 6, 1–6. 10.1016/S1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merk H.; Zhang S.; Lehr T.; Ulrich M.; Bibb J. A.; Liebl J. Inhibition of endothelial Cdk5 reduces tumor growth by promoting non-productive angiogenesis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 6088–6104. 10.18632/oncotarget.6842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich S. M.; Liebl J.; Ardelt M. A.; Lehr T.; De Toni E. N. Targeting cyclin dependent kinase 5 in hepatocellular carcinoma – A novel therapeutic approach. J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 102–13. 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A.; Cutler S. J.; Doerksen R. J.; Khan I. A.; Williamson J. S. Discovery of thienoquinolone derivatives as selective and ATP non-competitive CDK5/p25 inhibitors by structure-based virtual screening. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 6409–6421. 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helal C. J.; Sanner M. A.; Cooper C. B.; Gant T.; Adam M. Discovery and SAR of 2-aminothiazole inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase 5/p25 as a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 14, 5521–5525. 10.1002/chin.200514225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghia P.; Scarfo L.; Pathiraja K.; Derosier M.; Small K. A Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Dinaciclib Compared to Ofatumumab in Patients with Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 2015, 126, 4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClue S. J.; Blake D.; Clarke R.; Cowan A.; Wang S. In vitro and in vivo antitumor properties of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor CYC202 (R-roscovitine). Int. J. Cancer 2002, 102, 463–468. 10.1002/ijc.10738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry D.; Guzi T.; Shanahan F.; Davis N.; Wiswell D. Dinaciclib (SCH 727965), a Novel and Potent Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 2344–2353. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H.; Shi S.; Foley D. W.; Lam F.; Abbas A. Y.; Liu X.; Huang S.; Jiang X.; Baharin N.; Fischer P. M.; Wang S. Synthesis, structure–activity relationship and biological evaluation of 2,4,5-trisubstituted pyrimidine CDK inhibitors as potential anti-tumour agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 70, 447–455. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Tan V. B. C.; Lim K. M.; Tay T. E. Molecular dynamics simulations on the inhibition of Cyclin-dependent kinases 2 and 5 in the presence of activators. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2006, 20, 647–671. 10.1007/s10822-006-9081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroline M.; Robb S. K.; Jacob I. C.; Ekta A.; Smitha K. Characterization of CDK(5) inhibitor, 20–223 (aka CP668863) for colorectal cancer therapy. Oncotarget. 2018, 9, 5216–5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vymetalová L.; Havlíček L.; Šturc A.; Skrášková Z.; Kryštof V. 5-Substituted 3-isopropyl-7-[4-(2-pyridyl)benzyl]amino-1(2)H-pyrazolo[4,3-d]pyrimidines with anti-proliferative activity as potent and selective inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 110, 291–301. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghelli Luserna di Rora’ A.; Iacobucci I.; Martinelli G. The cell cycle checkpoint inhibitors in the treatment of leukemias. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 77. 10.1186/s13045-017-0443-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F.; Lee J. T.; Navolanic P. M.; Steelman L. S.; Shelton J. G. Involvement of PI3K/Akt pathway in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and neoplastic transformation: a target for cancer chemotherapy. Leukemia 2003, 17, 590–603. 10.1038/sj.leu.2402824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NavaneethaKrishnan S.; Rosales J. L.; Lee K.-Y. Loss of Cdk5 in breast cancer cells promotes ROS-mediated cell death through dysregulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Oncogene 2018, 37, 1788–1804. 10.1038/s41388-017-0103-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter B. Z.; Mak P. Y.; Wang X.; Yang H.; Andreeff M. Focal Adhesion Kinase as a Potential Target in AML and MDS. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 1133–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartel A. L.; Tyner A. L. The Role of the Cyclin-dependent Kinase Inhibitor p21 in Apoptosis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002, 1, 639–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas T.; Dutta A. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 400–414. 10.1038/nrc2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.