Abstract

Background

Major randomized trials assessing non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation generally excluded patients with hemoglobin <10 g/dL. This study evaluated the safety and effectiveness of NOACs in patients with atrial fibrillation and anemia.

Methods and Results

A cohort study based on electronic medical records was conducted from 2010 to 2017 at a multicenter healthcare provider in Taiwan. It included 8356 patients with atrial fibrillation who had received oral anticoagulants (age, 77.0±7.3 years; 48.0% women). Patients were classified into 2 subgroups: 7687 patients with hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL and 669 patients with hemoglobin <10 g/dL. A Cox regression analysis was performed to assess the risks of ischemic stroke/systemic embolism, bleeding, and death associated with NOAC versus warfarin in both subgroups, respectively. In patients with hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL, NOAC (n=4793) was associated with significantly lower risks of ischemic stroke/systemic embolism, major bleeding, and gastrointestinal tract bleeding than warfarin (n=2894); there was no difference in the risk of death. In patients with hemoglobin <10 g/dL, NOAC (n=390) was associated with significantly lower risks of major bleeding (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.30–0.62) and gastrointestinal tract bleeding than warfarin (n=279), but there was no difference in the risk of ischemic stroke/systemic embolism (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.53–1.17) or death. Subgroup analyses suggested that NOAC was associated with fewer bleeding events, irrespective of cancer or peptic ulcer disease history.

Conclusions

In patients with atrial fibrillation with hemoglobin <10 g/dL, NOAC was associated with lower bleeding risks than warfarin, with no difference in the risk of ischemic stroke/systemic embolism or death.

Keywords: anemia, anticoagulation, atrial fibrillation, bleeding, outcome

Subject Categories: Atrial Fibrillation, Cerebrovascular Disease/Stroke, Anticoagulants

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, compared with warfarin, were associated with a significantly lower risk of major bleeding or gastrointestinal tract bleeding, but there was no difference in ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, or death in anemic patients with atrial fibrillation patients and hemoglobin <10 g/dL.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant is a favorable alternative to warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and anemia, ≥65 years.

Introduction

Anemia is frequently observed in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), and it may be associated with an increased risk of new‐onset AF.1, 2 AF increases the risks of ischemic stroke (IS) and systemic embolism (SE). Vitamin K antagonists reduce the risks of IS/SE in AF but also increase the risk of bleeding, especially in patients with anemia.3, 4, 5 In anticoagulated patients with AF, anemic patients have a higher prevalence of comorbidities, greater CHA2DS2‐VASC (Congestive Heart Failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 Years [doubled], Diabetes Mellitus, Prior Stroke, Transient Ischemic Attack, or Thromboembolism [doubled], Vascular Disease, Age 65–74 Years, Sex Category) and HAS‐BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal Renal/Liver Function, Stroke, Bleeding History or Predisposition, Labile International Normalized Ratio, Elderly, Drugs/Alcohol Concomitantly) scores, and increased risks of major bleeding, mortality, and anticoagulant discontinuation than those without anemia.1, 6 Physicians are, thus, faced with a treatment dilemma when choosing anticoagulant therapies in patients with AF and anemia.

Anemia is closely associated with peptic ulcer disease and cancer‐related bleeding.7, 8 Peptic ulcer disease is the most common cause of bleeding in patients receiving long‐term warfarin therapy.9 Warfarin therapy in patients with a history of peptic ulcer bleeding raises management difficulties on the balance between the thromboembolic risk secondary to anticoagulation interruption and the hemorrhagic risk associated with a history of bleeding.9 Treating AF with oral anticoagulants in patients with cancer is also a challenge because cancer may result in an increased risk of thromboembolism or bleeding.10 Therefore, such patients may respond unpredictably to anticoagulant therapy; thus, thromboembolic and bleeding‐risk prediction scores may not be reliable.10 .

Non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are now widely used as alternatives to warfarin for preventing stroke in AF because NOACs are as effective as but safer than warfarin.11, 12, 13, 14 The working dosage of NOACs is generally easier to ascertain because there is less variation among individuals and the drugs have a faster action onset and offset and exhibit fewer drug‐food and drug‐drug interactions than warfarin does.15 However, most major randomized controlled trials of NOACs have excluded patients with hemoglobin <10 g/dL.11, 13, 14, 16 In addition, there is no specific recommendation for anticoagulant therapy in anemic patients with AF and hemoglobin <10 g/dL in current guidelines.17, 18, 19 Hence, the aim of the present study was to compare the safety and effectiveness of NOAC and warfarin when prescribed for stroke prevention in patients with AF and hemoglobin <10 g/dL.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

In this retrospective cohort study, patient data were collected from the Chang Gung Research Database, a deidentified database derived from the electronic medical records of the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital system in Taiwan. The Chang Gung Memorial Hospital is currently the largest Taiwanese medical care system, comprising 4 tertiary‐care medical centers and 3 major teaching hospitals. This medical care system, with >10 000 beds and >280 000 inpatients per year, provides ≈10% of all medical service used by the Taiwanese people annually.20, 21, 22 The hospital identification number of each patient was encrypted and deidentified to protect individuals’ privacy. The diagnoses and laboratory data could be linked and continuously monitored using consistent data encryption. The institutional review board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital approved the study protocol (approval serial No. 21080666B0). The institutional review board waived the need for informed consents from the patients and prentices/guardians because the database used in this study consists of unidentifiable, secondary data released to the public for research.

Study Cohort

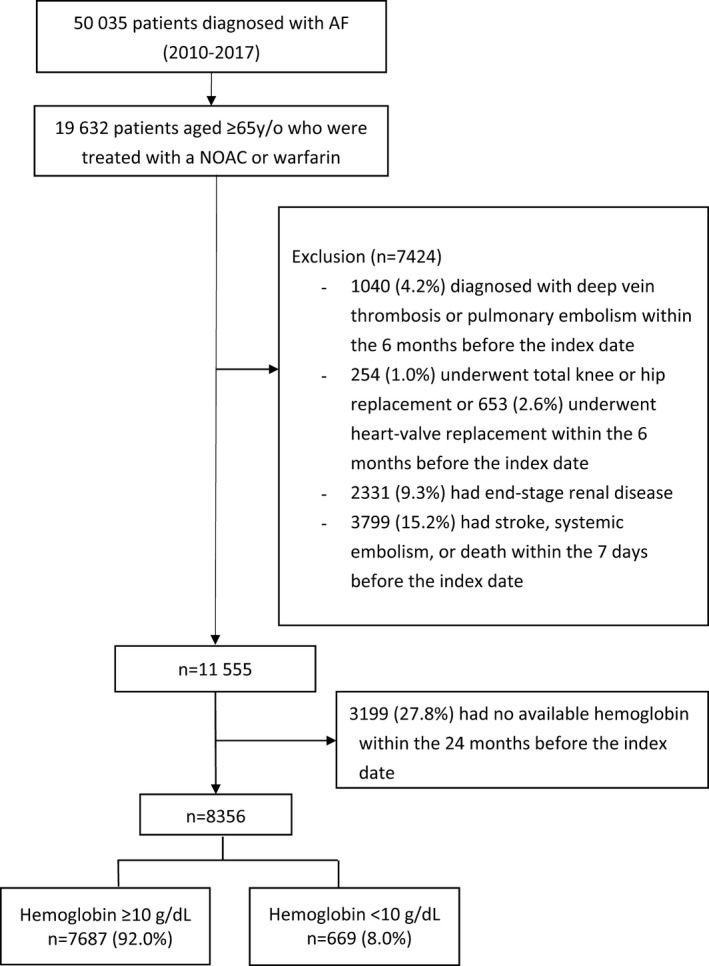

This study was conducted on the basis of electronic medical records in the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital system in Taiwan from 2010 to 2017. A total of 19 632 patients, aged ≥65 years, who had been diagnosed with AF (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD‐9], code 427.31 or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD‐10], codes I48.0, I48.1, I48.2, or I48.91) and had had at least 1 prescription filled for oral anticoagulant therapy after diagnosis were included. We enrolled patients with AF, aged ≥65 years, because the Taiwan National Health Insurance only reimburses for NOAC prescriptions for these patients. The oral anticoagulant therapy consisted of warfarin or an NOAC (apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban). Patients were excluded if they had the following: (1) had deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism up to 6 months before the index day (n=1040), (2) had received joint surgery (n=254) or a heart‐valve replacement (n=653) up to 6 months before the index date, (3) had end‐stage renal disease before the index date (n=2331), (4) had IS or SE or died up to 7 days after the index date (n=3799), or (5) had not had data on hemoglobin levels for the 2 years before the index date (n=3199). After the exclusion, 8356 patients remained eligible for the study, and these patients were divided into 2 subgroups: patients with hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL (n=7687, 92.0%) and those with hemoglobin <10 g/dL (n=669, 8.0%).9, 10, 11, 14 The Figure is the flowchart of the enrollment process and the subdivision of the eligible study cohort into the 2 subgroups. The index date was defined as the first date on which warfarin or NOAC therapy was initiated. The risks of IS/SE, bleeding, and death were compared between NOAC and warfarin therapies in these 2 subgroups of anticoagulated patients with AF. The identified patients were followed up until the outcome event or the end of 2017, whichever occurred first.

Figure 1.

Enrollment of patients, aged ≥65 years, with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF). From January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2017, this study evaluated a total of 7687 patients with hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL and 669 patients with hemoglobin <10 g/dL. NOAC indicates non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant.

Assessment of Other Covariates

Baseline comorbidities of the study cohort included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, and histories of heart failure, myocardial infarction, transient ischemic attack, IS, SE, bleeding, peptic ulcer disease, and cancer. Laboratory data included serum hemoglobin, platelet counts, estimated glomerular filtration rate, liver function tests, and lipid profiles. Baseline medications were identified from medical records for the 180‐day period before the index date, including antiplatelets, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, statins, amiodarone, digoxin, and proton pump inhibitors.

Outcome Measures

The efficacy end point was the occurrence of IS/SE or death. The safety end point was the occurrence of major bleeding or gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Major bleeding was defined as clinically overt bleeding associated with at least a 2‐g/dL decrease in hemoglobin or requiring a transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells or whole blood, fatal bleeding, or intracranial hemorrhage during the period of drug use or within the 14‐day period after the last day of drug use. Gastrointestinal tract bleeding was defined as hospitalization with a primary diagnosis of bleeding in any segment of the gastrointestinal tract, from the esophagus to the rectum, during the drug‐use period or within the 14‐day period after the last day of drug use. The follow‐up period was defined as the time from the index date to the first occurrence of any study outcome or the end date of the study period (December 31, 2017), whichever came first. The anticoagulant type was treated as a time‐dependent exposure. A 14‐day period was the censoring window for drug switches. If an event occurred during the initial therapy period or within the 14‐day period after the switch, the event and time were ascribed to the initial therapy. If an event occurred ≥15 days after the switch, the event and time were ascribed to the switch therapy. The diagnostic codes used to identify the study outcomes and the baseline covariates are summarized in Table S1.

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as the mean±SD or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and as proportions for categorical variables. Differences between continuous values were assessed using Wilcoxon's rank‐sum test. Differences between nominal variables were compared with a χ2 test. We calculated event rates as the number of events divided by 100 person‐years. The Cox proportional hazard regression with time‐dependent exposure (anticoagulant type) was used to compare event rates between NOAC and warfarin therapies in the 2 groups of patients. When comparing the risk of IS/SE, major bleeding, gastrointestinal tract bleeding, or death between NOAC and warfarin therapies, the analyses were adjusted for covariates, including patient characteristics, baseline comorbidities, laboratory information, and baseline medications. Statistical significance was based on the level of α=0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

We performed 3 sensitivity analyses to validate our findings and check for potential selection biases. First, given the high mortality risk in patients with AF and anemia, we reanalyzed the data accounting for competing risks of death. Second, we reanalyzed the data by using 7 days as a censoring window for drug switches to assess whether the primary findings would have been changed if differential censoring windows between drug switches had been used. Third, we reanalyzed the data after excluding patients with missing values of covariates in the models to determine if missing data would change the results. Subgroup analyses were performed to explore the effects of anticoagulant types in patient subgroups with and without a history of peptic ulcer disease or cancer.23, 24

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of anticoagulated patients with AF and different hemoglobin levels. The 7687 patients in the patient subgroup with hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL were a mean±SD age of 76.7±7.2 years, had a mean±SD CHA2DS2‐VASc score of 3.8±1.6, and had a mean±SD HAS‐BLED score of 3.1±1.1. The 669 patients in the patient subgroup with hemoglobin <10 g/dL were a mean±SD age of 79.4±7.6 years, had a mean±SD CHA2DS2‐VASc score of 4.3±1.8, and had a mean±SD HAS‐BLED score of 3.7±1.0. Of the 669 patients with hemoglobin <10 g/dL, 446 (66.7%), 184 (27.5%), 25 (3.7%), and 14 (2.1%) had hemoglobin levels of 9 to 9.9, 8 to 8.9, 7 to 7.9, and <7 g/dL, respectively. Both CHA2DS2‐VASc and HAS‐BLED scores were significantly higher in the patient subgroup with hemoglobin <10 g/dL. Patients with hemoglobin <10 g/dL tended to be older, to be women, and to have more comorbidities and a history of heart failure or stroke. In summary, patients with hemoglobin <10 g/dL were older and weaker than those with hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL. A separate comparison between NOAC and warfarin users in the patient subgroup with hemoglobin <10 g/dL is given in Table 2. Within the group, patients using NOAC or warfarin had similar demographic characteristics and comorbidities, except for older age in NOAC users.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Anticoagulated Patients With AF and Hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL and Hemoglobin <10 g/dL

| Characteristic | All Patients (n=8356) | Hemoglobin, g/dL | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥10 (n=7687) | <10 (n=669) | |||

| Age, y | 77.0±7.3 | 76.7±7.2 | 79.4±7.6 | <0.001 |

| Aged 65–74 y, n (%) | 3283 (39.3) | 3100 (40.3) | 183 (27.4) | |

| Aged 75–84 y, n (%) | 3670 (43.9) | 3372 (43.9) | 298 (44.5) | |

| Aged ≥85 y, n (%) | 1403 (16.8) | 1215 (15.8) | 188 (28.1) | |

| Women, n (%) | 4009 (48.0) | 3612 (47.0) | 397 (59.3) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity at index date, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2116 (25.3) | 1927 (25.1) | 189 (28.3) | 0.069 |

| Hypertension | 4789 (57.3) | 4430 (57.6) | 359 (53.7) | 0.047 |

| Chronic liver disease | 1427 (17.1) | 1335 (17.4) | 92 (13.8) | 0.018 |

| Heart failure | 3389 (40.6) | 3068 (39.9) | 321 (48.0) | <0.001 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1835 (22.0) | 1681 (21.9) | 154 (23.0) | 0.490 |

| Prior stroke | 1874 (22.4) | 1695 (22.1) | 179 (26.8) | 0.005 |

| Peripheral artery occlusive disease | 196 (2.4) | 165 (2.2) | 31 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| Prior transient ischemic attack | 305 (3.7) | 282 (3.7) | 23 (3.4) | 0.760 |

| Bleeding history | 3711 (44.4) | 3430 (44.6) | 281 (42.0) | 0.191 |

| Cancer | 1244 (14.9) | 1099 (14.3) | 145 (21.7) | <0.001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 2767 (33.1) | 2547 (33.1) | 220 (32.9) | 0.896 |

| CHA2DS2‐VASc score* | 3.9±1.7 | 3.8±1.6 | 4.3±1.8 | <0.001 |

| HAS‐BLED score† | 3.2±1.1 | 3.1±1.1 | 3.7±1.0 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 70.7±25.1 | 70.9±24.3 | 67.2±33.3 | 0.001 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, n (%) | 2275 (27.2) | 2026 (23.3) | 249 (37.2) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.0 (11.6–14.4) | 13.2 (12.0–14.5) | 9.3 (8.7–9.6) | <0.001 |

| Platelets, ×103/μL | 189 (152–234) | 188 (152–231) | 208 (149–283) | <0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 27 (21–36) | 27 (22–36) | 28 (21–41) | 0.109 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 20 (15–30) | 21 (15–30) | 18 (13–29) | <0.001 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | <0.001 |

| LDL‐C, mg/dL | 91.2±26.5 | 91.6±26.4 | 85.4±27.6 | 0.005 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 163.4±32.0 | 164.1±31.4 | 153.1±38.7 | <0.001 |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||

| Statins | 3039 (36.4) | 2873 (37.4) | 166 (24.8) | <0.001 |

| Amiodarone | 3181 (38.1) | 2909 (37.8) | 272 (40.7) | 0.150 |

| ß Blockers | 5724 (68.5) | 5275 (68.6) | 449 (67.1) | 0.421 |

| ACEIs or ARBs | 5748 (68.8) | 5326 (69.3) | 422 (63.1) | 0.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2914 (34.9) | 2667 (34.7) | 247 (36.9) | 0.247 |

| Loop diuretics | 4341 (52.0) | 3859 (50.2) | 482 (72.1) | <0.001 |

| Aspirin | 3572 (42.8) | 3314 (43.1) | 258 (38.6) | 0.023 |

| Digoxin | 2475 (29.6) | 2264 (29.5) | 211 (31.5) | 0.260 |

| Clopidogrel | 1697 (20.3) | 1539 (20.0) | 158 (23.6) | 0.027 |

| Ticagrelor | 154 (1.8) | 142 (1.9) | 12 (1.8) | 0.921 |

| Nonsteroid anti‐inflammatory drugs | 2972 (35.6) | 2756 (35.9) | 216 (32.3) | 0.065 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 2529 (30.3) | 2227 (29.0) | 302 (45.1) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin | 3173 (38.0) | 2894 (37.7) | 279 (41.7) | 0.038 |

| NOACs | 5183 (62.0) | 4793 (62.4) | 390 (58.3) | 0.038 |

| Dabigatran, 110 mg | 1635 (19.6) | 1569 (20.4) | 66 (9.9) | |

| Dabigatran, 150 mg | 238 (2.9) | 231 (3.0) | 7 (1.1) | |

| Rivaroxaban, 10 mg | 1183 (14.2) | 1088 (14.2) | 95 (14.2) | |

| Rivaroxaban, 15 mg | 2024 (24.2) | 1917 (24.9) | 107 (16.0) | |

| Rivaroxaban, 20 mg | 942 (11.3) | 886 (11.5) | 56 (8.4) | |

| Apixaban, 5 mg | 1768 (21.2) | 1611 (21.0) | 157 (23.5) | |

| Edoxaban, 30 mg | 701 (8.4) | 652 (8.5) | 49 (7.3) | |

| Edoxaban, 60 mg | 305 (3.7) | 298 (3.9) | 7 (1.1) | |

| Patients with anticoagulant switch, n (%) | 1459 (17.5) | 1397 (18.2) | 62 (9.3) | |

| No. of anticoagulant switches | ||||

| Warfarin to NOAC | 1705 | 1648 | 57 | |

| NOAC to warfarin | 624 | 609 | 15 | |

Values are given as mean±SD or median (interquartile range), except as noted. The CHA2DS2‐VASc score awards 1 point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, and female sex (sex category) and 2 points each for age ≥75 years and previous stroke or transient ischemic attack. The HAS‐BLED score awards 1 point each for hypertension, abnormal renal or liver function, stroke, bleeding history, labile international normalized ratio, age ≥65 years, and antiplatelet drug or alcohol use. ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; NOAC, non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant.

*Congestive Heart Failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 Years (doubled), Diabetes Mellitus, Prior Stroke, Transient Ischemic Attack, or Thromboembolism [doubled], Vascular Disease, Age 65–74 Years, Sex Category.

Hypertension, Abnormal Renal/Liver Function, Stroke, Bleeding History or Predisposition, Labile International Normalized Ratio, Elderly, Drugs/Alcohol Concomitantly.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of NOAC and Warfarin Users in Patients With Hemoglobin <10 g/dL

| Characteristic | NOAC Users (n=390) | Warfarin Users (n=279) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 81 (75–86) | 78 (72–83) | <0.001 |

| Aged 65–74 y, n (%) | 86 (22.1) | 97 (34.8) | |

| Aged 75–84 y, n (%) | 176 (45.1) | 122 (43.7) | |

| Aged ≥85 y, n (%) | 128 (32.8) | 60 (21.5) | |

| Women, n (%) | 229 (58.7) | 168 (60.2) | 0.70 |

| Comorbidity at index date, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 112 (28.7) | 77 (27.6) | 0.75 |

| Hypertension | 219 (56.2) | 140 (50.2) | 0.13 |

| Chronic liver disease | 59 (15.1) | 33 (11.8) | 0.22 |

| Heart failure | 175 (44.9) | 146 (52.3) | 0.06 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 98 (25.1) | 56 (20.1) | 0.13 |

| Peripheral artery occlusive disease | 19 (4.9) | 12 (4.3) | 0.73 |

| Prior stroke | 97 (24.9) | 82 (29.4) | 0.19 |

| Prior transient ischemic attack | 12 (3.1) | 11 (3.9) | 0.55 |

| Bleeding history | 167 (42.8) | 114 (40.9) | 0.61 |

| Cancer | 85 (21.8) | 71 (25.5) | 0.27 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 132 (33.9) | 88 (31.5) | 0.53 |

| CHA2DS2‐VASc score* | 4.3±1.7 | 4.3±1.9 | 0.67 |

| HAS‐BLED score† | 3.7±1.0 | 3.7±1.1 | 0.81 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 61 (45–85) | 55 (43–85) | 0.25 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, n (%) | 149 (38.2) | 100 (35.8) | 0.53 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 9.3 (8.8–9.7) | 9.2 (8.6–9.6) | 0.05 |

| Platelets, ×103/μL | 211 (163–284) | 200 (131–281) | 0.09 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 27 (21–37) | 29 (20–51) | 0.11 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 18 (13–29) | 18 (13–29) | 0.99 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.7 (0.4–0.9) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | 0.43 |

| LDL‐C, mg/dL | 83 (66–105) | 81 (65–95) | 0.20 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 150 (131–176) | 151 (125–179) | 0.84 |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Statins | 83 (21.3) | 83 (29.8) | 0.012 |

| Amiodarone | 134 (34.4) | 138 (49.5) | <0.001 |

| ß Blockers | 251 (64.4) | 198 (71.0) | 0.07 |

| ACEIs or ARBs | 224 (57.4) | 198 (71.0) | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 136 (34.9) | 111 (39.8) | 0.19 |

| Loop diuretics | 248 (65.6) | 234 (83.9) | <0.001 |

| Aspirin | 118 (30.3) | 140 (50.2) | <0.001 |

| Digoxin | 96 (24.6) | 115 (41.2) | <0.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 75 (19.2) | 83 (29.8) | 0.002 |

| Ticagrelor | 8 (2.1) | 4 (1.4) | 0.55 |

| Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs | 111 (28.5) | 105 (37.6) | 0.012 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 147 (37.7) | 155 (55.6) | <0.001 |

Values are given as mean±SD or median (interquartile range), except as noted. The CHA2DS2‐VASc score awards 1 point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, and female sex (sex category) and 2 points each for age ≥75 years and previous stroke or transient ischemic attack. The HAS‐BLED score awards 1 point each for hypertension, abnormal renal or liver function, stroke, bleeding history, labile international normalized ratio, age ≥65 years, and antiplatelet drug or alcohol use. ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; NOAC, non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant.

*Congestive Heart Failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 Years (doubled), Diabetes Mellitus, Prior Stroke, Transient Ischemic Attack, or Thromboembolism [doubled], Vascular Disease, Age 65–74 Years, Sex Category.

Hypertension, Abnormal Renal/Liver Function, Stroke, Bleeding History or Predisposition, Labile International Normalized Ratio, Elderly, Drugs/Alcohol Concomitantly.

Patients With Hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL

The crude event rates per 100 person‐years in the NOAC and warfarin groups were 5.10 and 6.67 for IS/SE, 7.35 and 12.36 for major bleeding, 4.27 and 5.76 for gastrointestinal tract bleeding, and 3.06 and 2.97 for death, respectively (Table 3, upper section). NOAC therapy (n=4793) was associated with significantly lower risks of IS/SE (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.68; 95% CI, 0.61–0.77; P<0.001), major bleeding (aHR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.46–0.56; P<0.001), and gastrointestinal tract bleeding (aHR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.59–0.77; P<0.001); and it showed no difference in the risk of death (aHR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.78–1.07; P=0.267) compared with warfarin therapy (n=2894).

Table 3.

Event Rate and Risk of IS/SE, Bleeding, and Death in Anticoagulated Patients With AF

| Variable | Event Rate/100 Person‐Years | Crude Data | Adjusted Dataa | Competing Riskb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOAC Users (n=4793) | Warfarin Users (n=2894) | HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL (n=7687) | ||||||||

| IS/SE | 5.10 | 6.67 | 0.62 (0.55–0.69) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.66–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.65–0.84) | <0.001 |

| Major bleeding | 7.35 | 12.36 | 0.46 (0.42–0.51) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.48–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.52 (0.46–0.58) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal tract bleeding | 4.27 | 5.76 | 0.58 (0.51–0.65) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.60–0.78) | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.59–0.77) | <0.001 |

| Death | 3.06 | 2.97 | 0.95 (0.81–1.10) | 0.492 | 1.05 (0.89–1.23) | 0.576 | ||

| Hemoglobin <10 g/dL (n = 669) | ||||||||

| IS/SE | 7.29 | 8.30 | 0.59 (0.41–0.86) | 0.006 | 0.71 (0.47–1.06) | 0.106 | 0.64 (0.42–0.97) | 0.035 |

| Major bleeding | 7.61 | 14.27 | 0.37 (0.25–0.52) | <0.001 | 0.41 (0.28–0.60) | <0.001 | 0.40 (0.28–0.59) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal tract bleeding | 3.76 | 7.18 | 0.37 (0.24–0.58) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.26–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.41 (0.25–0.67) | <0.001 |

| Death | 8.10 | 5.94 | 1.07 (0.73–1.56) | 0.743 | 1.11 (0.74–1.68) | 0.643 | ||

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; HR, hazard ratio; IS, ischemic stroke; NOAC, non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; SE, systemic embolism.

IS/SE or death, adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, history of heart failure, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, cancer, vascular disease, history of stroke, statins, hypertension medications, and antiplatelets; major bleeding or gastrointestinal tract bleeding, adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, history of heart failure, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, cancer, history of peptic ulcer disease, history of bleeding, history of stroke, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug, proton pump inhibitors, and antiplatelets.

Death was considered as a competing risk factor in the Cox model.

Patients With Hemoglobin <10 g/dL

The crude event rates per 100 person‐years in the NOAC and warfarin groups were 7.29 and 8.30 for IS/SE, 7.61 and 14.27 for major bleeding, 3.76 and 7.18 for gastrointestinal tract bleeding, and 8.10 and 5.94 for death, respectively (Table 3, lower section). NOAC therapy (n=390) was associated with lower risks of major bleeding (aHR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.30–0.62; P<0.001) and gastrointestinal tract bleeding (aHR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.28–0.71; P<0.001), with no significant differences in the risks of IS/SE (aHR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.53–1.17; P=0.249) and death (aHR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.66–1.48; P=0.951) compared with warfarin therapy (n=279).

Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

The results were similar for IS/SE and bleeding when death was treated as a competing risk factor in the Cox model (Table 3). We reanalyzed the data by using 7 days as a censoring window for drug switches and found similar results to those obtained with a 14‐day censoring window (Table S2). Table S3 shows the analysis results after excluding patients with missing values of covariates; the results were similar to the main results. For the subgroup analysis of patients with and without a history of cancer (Table 4) or peptic ulcer disease (Table 5), the results were generally consistent with the main results. The lower risks of major bleeding and gastrointestinal tract bleeding associated with NOAC therapy were similar in patients with and without a history of cancer or peptic ulcer disease. However, extreme caution needs to be taken when interpreting the subgroup analyses because of the limited sample size and number of events. The number of events is way below the general rule of thumb.

Table 4.

Event Rate and Risk of IS/SE, Bleeding, and Death in Anemic Patients With AF, Stratified by Cancer History

| Hemoglobin <10 g/dL | Events/Total Years | Event Rate/100 Person‐Years | Crude Data | Adjusted Dataa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOAC Users (n=390) | Warfarin Users (n=279) | NOAC Users (n=390) | Warfarin Users (n=279) | HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Patients with a history of cancer (n=145) | ||||||||

| IS/SE | 10/143 | 9/153 | 7.01 | 5.89 | 0.68 (0.27–1.74) | 0.393 | 1.12 (0.33–4.02) | 0.870 |

| Major bleeding | 8/117 | 24/110 | 6.83 | 21.88 | 0.21 (0.09–0.45) | <0.001 | 0.22 (0.08–0.53) | 0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal tract bleeding | 8/138 | 15/140 | 5.81 | 10.70 | 0.30 (0.12–0.70) | 0.007 | 0.19 (0.06–0.49) | 0.004 |

| Death | 13/147 | 19/138 | 8.87 | 13.73 | 0.50 (0.24–1.05) | 0.061 | 0.49 (0.20–1.15) | 0.194 |

| Patients without a history of cancer (n=524) | ||||||||

| IS/SE | 41/557 | 56/631 | 7.36 | 8.88 | 0.58 (0.39–0.88) | 0.010 | 0.75 (0.48–1.15) | 0.203 |

| Major bleeding | 39/500 | 66/521 | 7.80 | 12.67 | 0.43 (0.28–0.63) | <0.001 | 0.49 (0.32–0.75) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal tract bleeding | 20/607 | 45/696 | 3.29 | 6.47 | 0.39 (0.22–0.65) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.28–0.87) | 0.016 |

| Death | 49/619 | 34/754 | 7.92 | 4.51 | 1.37 (0.88–2.15) | 0.187 | 1.28 (0.80–2.06) | 0.321 |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; HR, hazard ratio; IS, ischemic stroke; NOAC, non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; SE, systemic embolism.

IS/SE or death, adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, history of heart failure, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, vascular disease, history of stroke, statins, hypertension medications, and antiplatelets; major bleeding or gastrointestinal tract bleeding, adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, history of heart failure, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, history of peptic ulcer disease, history of bleeding, history of stroke, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug, proton pump inhibitors, and antiplatelets.

Table 5.

Event Rate and Risk of IS/SE, Bleeding, and Death in Anemic Patients With AF, Stratified by Peptic Ulcer Disease History

| Hemoglobin <10 g/dL | Events/Total Years | Event Rate/100 Person‐Years | Crude Data | Adjusted Dataa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOAC Users (n=390) | Warfarin Users (n=279) | NOAC Users (n=390) | Warfarin Users (n=279) | HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease (n=220) | ||||||||

| IS/SE | 26/226 | 19/258 | 11.48 | 7.37 | 1.14 (0.62–2.14) | 0.685 | 1.62 (0.80–3.40) | 0.208 |

| Major bleeding | 24/185 | 38/127 | 12.98 | 29.82 | 0.32 (0.19–0.54) | <0.001 | 0.36 (0.21–0.61) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal tract bleeding | 11/253 | 25/235 | 4.35 | 10.62 | 0.30 (0.14–0.61) | 0.001 | 0.36 (0.16–0.74) | 0.010 |

| Death | 22/275 | 22/270 | 8.00 | 8.16 | 0.92 (0.49–1.72) | 0.791 | 0.80 (0.41–1.58) | 0.571 |

| Patients without a history of peptic ulcer disease (n=449) | ||||||||

| IS/SE | 25/474 | 46/526 | 5.28 | 8.75 | 0.40 (0.24–0.64) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.31–0.91) | 0.029 |

| Major bleeding | 23/432 | 52/503 | 5.32 | 10.33 | 0.35 (0.21–0.57) | <0.001 | 0.49 (0.29–0.82) | 0.006 |

| Gastrointestinal tract bleeding | 17/492 | 35/600 | 3.46 | 5.83 | 0.42 (0.23–0.75) | 0.004 | 0.51 (0.27–0.94) | 0.023 |

| Death | 40/490 | 31/622 | 8.16 | 4.98 | 1.15 (0.72–1.87) | 0.567 | 1.09 (0.66–1.82) | 0.742 |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation; HR, hazard ratio; IS, ischemic stroke; NOAC, non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; SE, systemic embolism.

IS/SE or death, adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, history of heart failure, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, cancer, vascular disease, history of stroke, hypertension medications, and antiplatelets; major bleeding or gastrointestinal tract bleeding, adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, history of heart failure, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, cancer, history of bleeding, history of stroke, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug, proton pump inhibitors, and antiplatelets.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are as follows: (1) Approximately 8% of patients with AF had a hemoglobin <10 g/dL when they were anticoagulated. (2) In patients with AF and hemoglobin <10 g/dL, NOAC therapy was associated with a significantly lower risk of major bleeding or gastrointestinal tract bleeding when compared with warfarin therapy, and there was no statistical difference between the 2 therapies in terms of their risk of IS/SE or death. This better safety profile of NOAC therapy was consistent with the results in patients with hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL. (3) In anemic patients, the differences between NOAC and warfarin therapies in their effects on IS/SE, bleeding, and mortality were similar in patients with and without a history of cancer or peptic ulcer disease.

These findings fill a knowledge void on the safety and effectiveness of NOAC therapy for patients with AF and hemoglobin <10 g/dL. Such patients were typically excluded from the major randomized controlled trials that have investigated the efficacy and safety of NOACs for preventing stroke in patients with AF, namely, the RE‐LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long Term Anticoagulant Therapy) trial, the ROCKET AF (Rivaroxaban Once‐Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared With Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation), the ENGAGE AF (Effective Anticoagulation With Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation) trial, and the AVERROES (A Phase III Study of Apixaban in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation).11, 12, 14, 16 The superiority of NOAC over warfarin for preventing stroke in patients with AF and mild anemia (hemoglobin, 9–12.9 g/dL in men and 9–11.9 g/dL in women) has been demonstrated in a post hoc analysis in the ARISTOTLE (Apixaban for the Prevention of Stroke in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation) trial.1 In that trial, patients with mild anemia were older, had higher CHADS2 (Congestive Heart Failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 Years, Diabetes Mellitus, Prior Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack or Thromboembolism [doubled]) and HAS‐BLED scores, and were more likely to have had prior bleeding events than those without anemia.1 Apixaban therapy resulted in similar reductions in stroke and bleeding events relative to warfarin therapy in patients with and without mild anemia.1 In patients with moderate anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dL), NOAC seems to be an equally effective but safer anticoagulant than warfarin for preventing stroke for anemic patients with AF and hemoglobin <10 g/dL. The lower risk of major bleeding associated with NOAC therapy was consistently observed in anemic patients with or without a history of cancer or peptic ulcer disease. For patients with a history of cancer or peptic ulcer disease, NOAC may be a better oral anticoagulant than warfarin.

Anemia is common in patients with AF,18 and the choices of anticoagulant for patients with AF and anemia have been puzzling. A sizable proportion of patients with AF would not have been eligible for the 4 major clinical trials of NOACs, and the most common reason for their exclusion from these trials was anemia (15.1%).25 In the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for managing AF, anemia is considered as a potentially modifiable bleeding risk factor; and it is an important predictor of bleeding in HEMORR2HAGES (hepatic or renal disease, ethanol abuse, Malignancy, Older Age, Reduced Platelet Count or Function, Rebleeding, Hypertension, Anemia, Genetic Factors, Excessive Fall Risk and Stroke), ATRIA (Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation), and ORBIT (Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation) scores.3, 4, 5, 17 Anemic patients with AF requiring anticoagulation were less likely to receive warfarin therapy because of bleeding concerns, and they more often discontinued warfarin therapy than nonanemic patients with AF.26 In a subgroup analysis of the J‐ROCKET AF (Japanese‐ROCKET AF) trial, baseline anemia with warfarin therapy was one of the independent predictors of bleeding events.6 In addition, patients with AF and anemia were also associated with a higher prevalence of stroke, a higher CHA2DS2‐VASc score, and a greater risk of IS/SE.1 Similar to the study of patients with mild anemia in the ARISTOTLE trial,1 the present study found that patients with hemoglobin <10 g/dL were older, more likely to be women, and more likely to have experienced prior heart failure and stroke than patients with hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL. Both CHA2DS2‐VASc and HAS‐BLED scores were significantly higher in the anemic group. In these patients, NOAC therapy resulted in a similar reduction in the event rates of IS/SE and death and a significantly lower risk of major bleeding or gastrointestinal tract bleeding than warfarin.

Anemic patients with AF receiving anticoagulant therapy require more extensive follow‐up because of their increased risks of bleeding and the high probability of anticoagulant interruptions. In the present cohort, 8% of the patients initiating oral anticoagulant therapy had a baseline hemoglobin level <10 g/dL. Before NOAC therapy can be initiated in such patients, their history of bleeding and clinical conditions that are likely to result in bleeding (ie, peptic ulcer disease, impaired renal or liver function, anemia, and thrombocytopenia) should be investigated, and corrected, if reversible.17, 18 Medications that could increase the risk of major bleeding, such as nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs or antiplatelets, should be avoided or balanced with the risk and benefit of anticoagulant therapy. For patients receiving an NOAC therapy, it may be recommended to follow up the hemogram 1 month after anticoagulant initiation and then every 6 to 12 months thereafter may be advisable. If hemoglobin levels remain stable, NOAC therapy can be continued.

Study Strengths

The strengths of our study include using a large, well‐defined population sample; available baseline hemoglobin, platelet count, renal function, and liver function data before the initiation of oral anticoagulant therapy; and a direct comparison of NOAC and warfarin therapies in patients with hemoglobin levels <10 g/dL and ≥10 g/dL. To our knowledge, this is 1 of the only 2 studies that have compared NOAC therapy and warfarin therapy in patients with AF and hemoglobin <10 g/dL.1

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, miscoding and misclassification are potential sources of biases in a database that relies on physician‐reported diagnoses. However, such miscoding and misclassification are unlikely to have differed systematically between the 2 subgroups of patients, and our findings that NOAC was safer than warfarin and equally effective in patients with hemoglobin ≥10 g/dL agreed with meta‐analysis and real‐world data.27, 28 Second, because this study was a retrospective data analysis rather than a randomized controlled trial, both selection bias and unmeasured confounders were evident, despite statistical adjustments. Third, we did not assess the quality of warfarin control by calculating the time in therapeutic range because there were many missing values for prothrombin time from the follow‐up period. In Taiwan, the measured time in the therapeutic range measured in one study is 56.6%,29 which is lower than for the white or Japanese populations. The observed benefit of lower bleeding risks in NOACs might disappear when they were compared with well‐managed warfarin.30 Further studies to generalize and apply the findings of this study to other populations are, thus, warranted. Fourth, the sample size for patients with hemoglobin <10 g/dL was only 669. The small sample may not be sufficient to establish the efficacy and safety of NOACs and limit the generalization of the results. Similarly, given the limited patient number and event number in each subgroup, extreme caution is needed in the interpretation of subanalysis results.

Conclusions

In patients with AF and hemoglobin <10 g/dL, NOAC therapy was associated with lower risks of major bleeding or gastrointestinal tract bleeding than warfarin therapy, and the 2 therapies showed no significant difference in the risk of IS/SE or death.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by research grants from the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CORPG3G0271) and the Chang Gung University (CIRPD1D0031), Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. ICD‐9‐CM and ICD‐10‐CM Codes Used to Define the Comorbidities and Outcomes

Table S2. Event Rate and Risk of IS/SE, Bleeding, and Death in Anticoagulated AF Patients Using 7 Days as a Censoring Window for Drug Switches.

Table S3. Hazard Ratio With 95% Confidence Interval of Outcomes (NOACs versus Warfarin) in Patients With Missing Values Included or Excluded

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the statistical assistance from the Research Services Center for Health Information, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan, and want to acknowledge the support of the Maintenance Project of the Center for Big Data Analytics and Statistics (grant CLRPG3D0044) at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for study design and monitoring and data analysis and interpretation. This study is based, in part, on data from the Chang Gung Research Database, provided by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent the position of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012029 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012029.)

References

- 1. Westenbrink BD, Alings M, Granger CB, Alexander JH, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Thomas L, Wojdyla DM, Hanna M, Keltai M, Steg PG, De Caterina R, Wallentin L, van Gilst WH. Anemia is associated with bleeding and mortality, but not stroke, in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial. Am Heart J. 2017;185:140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hu WS, Sung FC, Lin CL. Aplastic anemia and risk of incident atrial fibrillation—a nationwide cohort study. Circ J. 2018;82:1279–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gage BF, Yan Y, Milligan PE, Waterman AD, Culverhouse R, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Clinical classification schemes for predicting hemorrhage: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation (NRAF). Am Heart J. 2006;151:713–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, Borowsky LH, Pomernacki NK, Udaltsova N, Singer DE. A new risk scheme to predict warfarin‐associated hemorrhage: the ATRIA (Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O'Brien EC, Simon DN, Thomas LE, Hylek EM, Gersh BJ, Ansell JE, Kowey PR, Mahaffey KW, Chang P, Fonarow GC, Pencina MJ, Piccini JP, Peterson ED. The ORBIT bleeding score: a simple bedside score to assess bleeding risk in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3258–3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hori M, Matsumoto M, Tanahashi N, Momomura SI, Uchiyama S, Goto S, Izumi T, Koretsune Y, Kajikawa M, Kato M, Cavaliere M, Iekushi K, Yamanaka S. Predictive factors for bleeding during treatment with rivaroxaban and warfarin in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation—subgroup analysis of J‐ROCKET AF. J Cardiol. 2016;68:523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim BS, Li BT, Engel A, Samra JS, Clarke S, Norton ID, Li AE. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding: a practical guide for clinicians. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5:467–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dicato M, Plawny L, Diederich M. Anemia in cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 7):vii167–vii172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thomopoulos KC, Mimidis KP, Theocharis GJ, Gatopoulou AG, Kartalis GN, Nikolopoulou VN. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients on long‐term oral anticoagulation therapy: endoscopic findings, clinical management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1365–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farmakis D, Parissis J, Filippatos G. Insights into onco‐cardiology: atrial fibrillation in cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:945–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, Wang S, Alings M, Xavier D, Zhu J, Diaz R, Lewis BS, Darius H, Diener HC, Joyner CD, Wallentin L. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Berkowitz SD, Fox KA, Califf RM. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al‐Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A, Bahit MC, Diaz R, Easton JD, Ezekowitz JA, Flaker G, Garcia D, Geraldes M, Gersh BJ, Golitsyn S, Goto S, Hermosillo AG, Hohnloser SH, Horowitz J, Mohan P, Jansky P, Lewis BS, Lopez‐Sendon JL, Pais P, Parkhomenko A, Verheugt FW, Zhu J, Wallentin L. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Halperin JL, Waldo AL, Ezekowitz MD, Weitz JI, Spinar J, Ruzyllo W, Ruda M, Koretsune Y, Betcher J, Shi M, Grip LT, Patel SP, Patel I, Hanyok JJ, Mercuri M, Antman EM. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2093–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Di Minno A, Frigerio B, Spadarella G, Ravani A, Sansaro D, Amato M, Kitzmiller JP, Pepi M, Tremoli E, Baldassarre D. Old and new oral anticoagulants: food, herbal medicines and drug interactions. Blood Rev. 2017;31:193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C, Diener HC, Hart R, Golitsyn S, Flaker G, Avezum A, Hohnloser SH, Diaz R, Talajic M, Zhu J, Pais P, Budaj A, Parkhomenko A, Jansky P, Commerford P, Tan RS, Sim KH, Lewis BS, Van Mieghem W, Lip GY, Kim JH, Lanas‐Zanetti F, Gonzalez‐Hermosillo A, Dans AL, Munawar M, O'Donnell M, Lawrence J, Lewis G, Afzal R, Yusuf S. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:806–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, Castella M, Diener HC, Heidbuchel H, Hendriks J, Hindricks G, Manolis AS, Oldgren J, Popescu BA, Schotten U, Van Putte B, Vardas P. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2893–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr, Conti JB, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Murray KT, Sacco RL, Stevenson WG, Tchou PJ, Tracy CM, Yancy CW. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130:2071–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, Albaladejo P, Antz M, Desteghe L, Haeusler KG, Oldgren J, Reinecke H, Roldan‐Schilling V, Rowell N, Sinnaeve P, Collins R, Camm AJ, Heidbuchel H. The 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non‐vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:1330–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsai MS, Lin MH, Lee CP, Yang YH, Chen WC, Chang GH, Tsai YT, Chen PC, Tsai YH. Chang Gung Research Database: a multi‐institutional database consisting of original medical records. Biomed J. 2017;40:263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang CL, Wu VC, Kuo CF, Chu PH, Tseng HJ, Wen MS, Chang SH. Efficacy and safety of non‐vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation patients with impaired liver function: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009263 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang CL, Wu VC, Lee CH, Kuo CF, Chen YL, Chu PH, Chen SW, Wen MS, See LC, Chang SH. Effectiveness and safety of non‐vitamin‐K antagonist oral anticoagulants versus warfarin in atrial fibrillation patients with thrombocytopenia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2018. Available at: 10.1007/s11239-018-1792-1. Accessed April 18, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hsu CC, Hsu YC, Chang KH, Lee CY, Chong LW, Lin CL, Shang CS, Sung FC, Kao CH. Depression and the risk of peptic ulcer disease: a nationwide population‐based study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chew TW, Gau CS, Wen YW, Shen LJ, Mullins CD, Hsiao FY. Epidemiology, clinical profile and treatment patterns of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients in Taiwan: a population‐based study. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hughey AB, Gu X, Haymart B, Kline‐Rogers E, Almany S, Kozlowski J, Besley D, Krol GD, Ahsan S, Kaatz S, Froehlich JB, Barnes GD. Warfarin for prevention of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes of the “Real‐World” Michigan Anticoagulation Quality Improvement Initiative (MAQI2) registry to the RE‐LY, ROCKET‐AF, and ARISTOTLE trials. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2018;46:316–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pandya EY, Anderson E, Chow C, Wang Y, Bajorek B. Contemporary utilization of antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation: an audit in an Australian hospital setting. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9:97–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman EB, Deenadayalu N, Ezekowitz MD, Camm AJ, Weitz JI, Lewis BS, Parkhomenko A, Yamashita T, Antman EM. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta‐analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383:955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Forslund T, Wettermark B, Andersen M, Hjemdahl P. Stroke and bleeding with non‐vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant or warfarin treatment in patients with non‐valvular atrial fibrillation: a population‐based cohort study. Europace. 2018;20:420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shimada YJ, Yamashita T, Koretsune Y, Kimura T, Abe K, Sasaki S, Mercuri M, Ruff CT, Giugliano RP. Effects of regional differences in Asia on efficacy and safety of edoxaban compared with warfarin—insights from the ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 trial. Circ J. 2015;79:2560–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Denas G, Gennaro N, Ferroni E, Fedeli U, Saugo M, Zoppellaro G, Padayattil Jose S, Costa G, Corti MC, Andretta M, Pengo V. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulation with non‐vitamin K antagonists compared to well‐managed vitamin K antagonists in naive patients with non‐valvular atrial fibrillation: propensity score matched cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;249:198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. ICD‐9‐CM and ICD‐10‐CM Codes Used to Define the Comorbidities and Outcomes

Table S2. Event Rate and Risk of IS/SE, Bleeding, and Death in Anticoagulated AF Patients Using 7 Days as a Censoring Window for Drug Switches.

Table S3. Hazard Ratio With 95% Confidence Interval of Outcomes (NOACs versus Warfarin) in Patients With Missing Values Included or Excluded