Abstract

Background

Patient satisfaction with therapy is an important metric of care quality and has been associated with greater medication persistence. We evaluated the association of patient satisfaction with warfarin therapy to other metrics of anticoagulation care quality and clinical outcomes among patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

Methods and Results

Using data from the ORBIT‐AF (Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation) registry, patients were identified with AF who were taking warfarin and had completed an Anti‐Clot Treatment Scale (ACTS) questionnaire, a validated metric of patient‐reported burden and benefit of oral anticoagulation. Multivariate regressions were used to determine association of ACTS burden and benefit scores with time in therapeutic international normalized ratio range (TTR; both ≥75% and ≥60%), warfarin discontinuation, and clinical outcomes (death, stroke, major bleed, and all‐cause hospitalization). Among 1514 patients with AF on warfarin therapy (75±10 years; 42% women; CHA 2 DS 2‐VASc 3.9±1.7), those most burdened with warfarin therapy were younger and more likely to be women, have paroxysmal AF, and to be treated with antiarrhythmic drugs. After adjustment for covariates, ACTS burden scores were independent of TTR (TTR ≥75%: odds ratio, 1.01 [95% CI, 0.99–1.03]; TTR ≥60%: odds ratio, 1.01 [95% CI, 0.98–1.05]), warfarin discontinuation (odds ratio, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97–1.01), or clinical outcomes. ACTS benefit scores were also not associated with TTR, warfarin discontinuation, or clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

In a large registry of patients with AF taking warfarin, ACTS scores provided independent information beyond other traditional metrics of oral anticoagulation care quality and identified patient groups at high risk for dissatisfaction with warfarin therapy.

Keywords: anticoagulation, atrial fibrillation, patient‐reported outcome, patient‐centered care, warfarin

Subject Categories: Atrial Fibrillation

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Patients reporting the most burden from warfarin therapy, as determined by the Anti‐Clot Treatment Scale questionnaire, were younger and more likely to be women, have paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, and be treated with antiarrhythmic drugs.

Patient quartiles reporting the least burden from warfarin therapy had higher 1‐year time in therapeutic international normalized ratio range and less warfarin discontinuation, although there was no association after multivariate adjustment.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Anti‐Clot Treatment Scale scores provide independent information beyond other traditional metrics of oral anticoagulation care quality.

With several available alternatives to warfarin therapy, patient‐reported care satisfaction with warfarin therapy should be proactively assessed.

Introduction

Patient‐centered care has been increasingly recognized as an important aspect of healthcare delivery, incorporated into contemporary healthcare reform efforts,1 and associated with superior clinical outcomes in certain contexts.2 Mechanisms for association between patient‐centered care and clinical outcomes include higher treatment persistence, which may mediate an association between patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes. For oral anticoagulation (OAC) with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), time in therapeutic international normalized ratio (INR) range (TTR)3 has been associated with lower risk of thromboembolism and bleeding.4, 5 While there are many contributors to TTR, patient satisfaction with anticoagulation may significantly influence warfarin adherence and persistence. However, to date, there are few data assessing the impact of patient‐reported OAC outcomes on clinical outcomes. Additionally, there are currently several alternatives to warfarin therapy including the non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants that could be considered for use among individuals with low satisfaction with warfarin therapy. Therefore, understanding the extent of patient satisfaction (or lack thereof) with warfarin therapy and characterization of these groups would be of value.

Using data from ORBIT‐AF (Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation) and the Anti‐Clot Treatment Scale (ACTS) questionnaire, the objectives of these analyses were to: (1) describe characteristics of patients with high and low satisfaction with warfarin therapy, and (2) determine whether patient satisfaction with warfarin therapy is associated with TTR, warfarin discontinuation, and clinical outcomes.

Methods

ORBIT‐AF is an outpatient‐based registry of patients with incident or prevalent AF who were enrolled from June 29, 2010, to August 9, 2011, in the United States. Patients were enrolled from geographically diverse settings and care models (ie, primary care, cardiology, and/or electrophysiology managed patients in academic, private, and/or government healthcare settings) to create a representative sample of patients with AF. An adaptive design was used to ensure a representative cohort by geography and care model. Study initiation and coordination was overseen by the Duke Clinical Research Institute. Methods for registry design and execution have been previously described in detail.6, 7, 8 The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.

Patients who met registry criteria were enrolled consecutively from participating sites. Registry inclusion criterion was electrocardiographic evidence of AF. Exclusion criteria were: (1) age younger than 18 years; (2) AF from a reversible cause (eg, cardiac surgery, thyroid disease); (3) life expectancy <6 months; and (4) inability to provide informed consent or follow‐up. A preplanned patient‐reported outcomes substudy targeted enrollment of ≈1500 patients. All sites were eligible to participate in the substudy. Registry data collection was primarily derived from patient medical records with outcomes of interest collected at 6‐month intervals with central adjudication.

Patients included in the patient‐reported outcomes substudy completed the ACTS questionnaire at the time of registry enrollment. The ACTS is a 15‐item instrument that is summarized as 2 scales that represent both negative (limitations, inconveniences, burdens) and positive (confidence, reassurance, satisfaction) aspects of anticoagulation treatment: ACTS burdens (12 items), and ACTS benefits (3 items). For each item, patient experience with anticoagulation treatment is rated on a 5‐point Likert scale from “Not at all” to “Extremely.” The 12 items of ACTS burdens are reverse coded (scored 5 to 1), whereas the 3 items of ACTS benefits are coded normally (scored 1–5), so that higher scores indicate greater patient satisfaction. The first burden question is “During the past 4 weeks how much does the possibility of bleeding as a result of anti‐clot treatment limit you from taking part in vigorous physical activities (eg, exercise, sports, dancing)?” The first benefit question is “During the past 4 weeks how confident are you that your anti‐clot treatment will protect your health (eg, prevent blood clots, stroke, heart attack, deep vein thrombosis, embolism)?” The full questionnaire is available in Table S1. Item scores are summed across domains to give an ACTS Burdens score ranging from 12 to 60 and an ACTS benefits score ranging from 3 to 15. A patient must have data for all items of a scale for the scale to be calculated.

The ACTS was built on the conceptual framework of the Duke Anticoagulation Satisfaction Scale and was developed to assess both warfarin therapy and non–vitamin K antagonist OACs. In validation studies, the ACTS has been shown to consistently satisfy traditional psychometric criteria for questionnaire acceptability, scaling assumptions, reliability, and validity across cultures and languages.9, 10, 11 The ACTS has also been used in the ROCKET AF (Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation) clinical trial, which evaluated rivaroxaban versus warfarin therapy.12

The primary predictors (independent variables) were the ACTS scores (burden and benefit) in patients treated with warfarin. The primary outcomes (dependent variables) were TTR between INR 2.0 to 3.0 and warfarin discontinuation over a 1‐year period after completing the ACTS questionnaire. We choose TTR ≥75% and ≥60% as thresholds in our analysis, as these represent the desired TTR threshold that maximizes effectiveness and safety and minimum threshold to demonstrate benefit of warfarin over aspirin, respectively.4, 13 TTR was calculated using the modified Rosendaal method of linear interpolation and its calculation in the ORBIT‐AF registry has been previously described.14 Warfarin discontinuation was assessed at 6 and 12 months, ascertained at patient follow‐up visits. We also evaluated clinical outcomes of death, ischemic stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA) or systemic embolism, major bleed,15 and all‐cause hospitalization.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were compared between patient quartiles of ACTS burden and benefit scores. Continuous variables are presented as median (25th–75th percentile) or mean and SD where noted, with differences assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables are presented as frequency (percentage) with differences assessed using chi‐square test. We determined the Pearson correlation coefficient between patients’ ACTS burden and benefit scores.

The frequency (percentage) of TTR ≥75%, TTR ≥60%, and warfarin discontinuation are presented by patient quartiles of ACTS burden and benefit scores. The frequency and incidence rate of clinical outcomes per 100‐patient years of follow‐up are also presented by quartile.

Logistic regression was used to determine the association between TTR ≥75%, TTR ≥60%, and ACTS scores with generalized estimating equations included to account for site variation. Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine the association between both warfarin discontinuation and clinical outcomes and ACTS scores, with a robust covariance estimate included to account for site variation. ACTS scores were treated as a continuous variable in all regressions. Warfarin discontinuation time was treated as discrete, with follow‐up at either 6 or 12 months. We performed sensitivity analyses by stratifying patients into low to moderate and high stroke risk by CHA2DS2‐VASc score, defined as scores <4 and ≥4, respectively. Both unadjusted and multivariate‐adjusted models were performed. Multivariate analysis included covariates, selected based on face validity, for demographics, medical history, AF history, medications, functional status, care model, and region, with the full covariate list provided in Table S2. All continuous covariates were tested for a linear association with each outcome, and any nonlinear relationship was accounted for using linear splines. Missing covariate data were handled by multiple imputation using Markov chain Monte Carlo or regression methods. Final estimates and standard errors reflect the combined analysis over 5 imputed data sets.

The present study and the ORBIT‐AF registry were approved by Duke University's institutional review board, and each site received equivalent approval subject to local regulation. All patients provided written, informed consent. The senior author had full access to all study data and takes responsibility for its integrity and the data analysis. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute).

Results

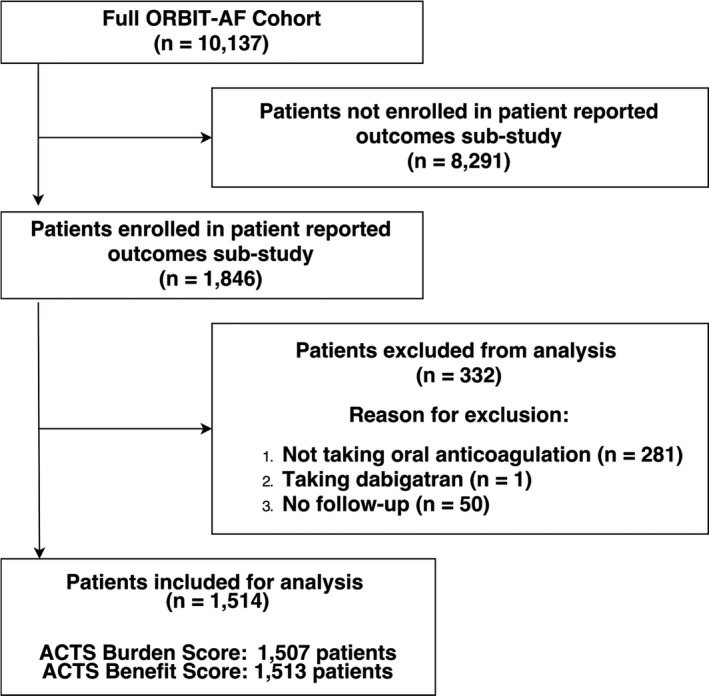

The overall ORBIT‐AF registry included 10 137 patients of whom 1514 (15%) completed ACTS questionnaires (ACTS burden: 1507 patients; ACTS benefit: 1513 patients), were taking warfarin, and completed follow‐up (Figure). As compared with patients from ORBIT‐AF taking warfarin who were excluded (5701), included patients (1514) were similar by age and sex, had slightly lower CHA2DS2‐VASc scores (3.9±1.7 versus 4.1±1.7; P<0.001), and were slightly less likely to have nonparoxysmal AF (48.5% versus 51.4%, P<0.001) (Table S3).

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria used to select analysis cohort. ACTS indicates Anti‐Clot Treatment Scale; ORBIT‐AF, Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation.

The analysis cohort of 1514 patients had a mean age of 75±10 years, 42% were women, and a mean CHA2DS2‐VASc score of 3.9±1.7 (CHA2DS2‐VASc <4: 581 patients; CHA2DS2‐VASc ≥4: 933 patients). As highlighted in Table 1, for the ACTS burden score, the patient quartiles reporting more burden from warfarin therapy were younger and more likely to be women, have paroxysmal AF, and be treated with antiarrhythmic drugs. For the ACTS benefit score, baseline characteristics were similar across score quartiles. Mean ACTS burden score was 53.7±7.0 (possible range 12–60) with means of 59.6±0.5 and 43.5±6.4 for the quartiles least and most burdened by warfarin therapy (P<0.001), respectively. Mean ACTS benefit score was 10.7±3.4 (possible range 3–15), with means of 14.8±0.4 and 5.2±1.9 for quartiles with the highest and lowest benefit (P<0.001), respectively (Table S4). Patients’ ACTS burden and benefit scores were weakly correlated (r=0.12, P<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by ACTS Burden Score Quartile

| ACTS Burden Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=1507) | Quartile 1 (n=371) | Quartile 2 (n=418) | Quartile 3 (n=288) | Quartile 4a (n=430) | P Valueb | |

| ACTS score, mean±SD | 53.7±7.0 | 43.5±6.4 | 53.9±1.7 | 57.5±0.5 | 59.6±0.5 | <0.001 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, mean±SD | 74.5±9.8 | 72.6±10.5 | 74.1±9.8 | 75.1±9.2 | 76.2±9.2 | <0.001 |

| Women | 637 (42.3) | 167 (45.0) | 194 (46.4) | 135 (46.9) | 141 (32.8) | <0.001 |

| Race | 0.499 | |||||

| White | 1371 (91.0) | 337 (90.8) | 381 (91.2) | 264 (91.7) | 389 (90.5) | |

| CHADS2 score group | 0.059 | |||||

| 0 or 1 | 399 (26.5) | 112 (30.2) | 109 (26.1) | 75 (26.0) | 103 (24.0) | |

| ≥2 | 1108 (73.5) | 259 (69.8) | 309 (73.9) | 213 (74.0) | 327 (76.0) | |

| CHADS2 score | 2.3±1.3 | 2.2±1.3 | 2.3±1.3 | 2.3±1.3 | 2.3±1.2 | 0.480 |

| CHA2DS2‐VASc score | 3.9±1.7 | 3.9±1.8 | 4.0±1.7 | 4.0±1.8 | 3.9±1.5 | 0.771 |

| Nonparoxysmal AF | 729 (48.4) | 162 (43.7) | 193 (46.2) | 133 (46.2) | 241 (56.1) | 0.015 |

| Heart failure | 426 (28.3) | 123 (33.2) | 119 (28.5) | 71 (24.7) | 113 (26.3) | 0.070 |

| CKD | 523 (34.7) | 115 (33.7) | 161 (41.7) | 107 (41.5) | 140 (35.8) | 0.071 |

| CAD | 473 (31.4) | 124 (33.4) | 131 (31.3) | 76 (26.4) | 142 (33.0) | 0.204 |

| Myocardial infarction | 210 (13.9) | 51 (13.8) | 55 (13.2) | 35 (12.2) | 69 (16.1) | 0.461 |

| Stroke/TIA | 251 (16.7) | 54 (14.6) | 77 (18.4) | 56 (19.4) | 64 (14.9) | 0.195 |

| PAD | 183 (12.1) | 40 (10.8) | 60 (14.4) | 35 (12.2) | 48 (11.2) | 0.400 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 414 (27.5) | 98 (26.4) | 112 (26.8) | 77 (26.7) | 127 (29.5) | 0.729 |

| Hypertension | 1262 (83.7) | 319 (86.0) | 341 (81.6) | 237 (82.3) | 365 (84.9) | 0.300 |

| Anemia | 225 (14.9) | 54 (14.6) | 75 (17.9) | 38 (13.2) | 58 (13.5) | 0.220 |

| Gastrointestinal bleed | 100 (6.6) | 24 (6.47) | 27 (6.46) | 20 (6.94) | 29 (6.74) | 0.993 |

| Care model | ||||||

| Payor/insurance | <0.001 | |||||

| Medicaid/Medicare | 1111 (73.7) | 242 (65.2) | 316 (75.6) | 213 (74.0) | 340 (79.1) | |

| Private | 318 (21.1) | 109 (29.4) | 78 (18.7) | 60 (20.8) | 71 (16.5) | |

| Other | 78 (5.2) | 20 (5.4) | 24 (5.7) | 15 (5.2) | 19 (4.4) | |

| OAC management | ||||||

| Home INR monitoring | 46 (3.1) | 12 (3.2) | 14 (3.4) | 9 (3.1) | 11 (2.6) | 0.913 |

| Anticoagulation clinic | 598 (39.7) | 146 (39.4) | 179 (42.8) | 112 (38.9) | 161 (37.4) | 0.437 |

| Cardiology care | 1260 (83.6) | 320 (86.3) | 353 (84.5) | 221 (76.7) | 366 (85.1) | 0.005 |

| Medication use | ||||||

| Prior warfarin usec | 1392 (92.4) | 345 (93.0) | 379 (90.7) | 271 (94.1) | 397 (92.3) | 0.371 |

| β‐Blockers | 1012 (67.2) | 239 (64.4) | 282 (67.5) | 193 (67.0) | 298 (69.3) | 0.568 |

| Calcium channel blockersd | 249 (16.5) | 72 (19.4) | 74 (17.7) | 35 (12.2) | 68 (15.8) | 0.076 |

| Digoxin | 385 (25.6) | 98 (26.4) | 104 (24.9) | 64 (22.2) | 119 (27.7) | 0.397 |

| Amiodarone | 125 (8.3) | 32 (8.6) | 49 (11.7) | 18 (6.3) | 26 (6.1) | 0.012 |

| Rhythm control agents | 383 (25.4) | 111 (29.9) | 120 (28.7) | 72 (25.0) | 80 (18.6) | <0.001 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 554 (36.8) | 143 (38.5) | 152 (36.4) | 98 (34.0) | 161 (37.4) | 0.671 |

| Statins | 784 (52.0) | 177 (47.7) | 213 (51.0) | 158 (54.9) | 236 (54.9) | 0.163 |

Values are expressed as mean±SD or number (percentage). AF indicates atrial fibrillation; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; INR, international normalized ratio; OAC, oral anticoagulation; PAD, peripheral artery disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Anti‐Clot Treatment Scale (ACTS) score quartile with least burden.

Differences between quartiles assessed using chi‐square test and Kruskal–Wallis test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Before enrollment in ORBIT‐AF (Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation).

Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.

Quality of Warfarin Therapy

For the ACTS burden score, patient quartiles reporting less burden from warfarin therapy had higher 1‐year rates of TTR (TTR ≥75% quartile 4: 41.5% versus quartile 1: 34.2% [P=0.017]; TTR ≥60% quartile 4: 62.0% versus quartile 1: 57.3% [P=0.035]), and no significant difference in warfarin discontinuation (quartile 4: 17.8% versus quartile 1: 23.2% [P=0.096]) (Table 2). In multivariate analyses, being less burdened by warfarin therapy was not associated with TTR (TTR ≥75%: odds ratio [OR], 1.01; 95% CI, 0.99–1.03 [P=0.153]; TTR ≥60%: OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.99–1.03 [P=0.208]) or warfarin discontinuation (OR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.97–1.01 [P=0.157]) (Table 3). When patients were stratified by CHA2DS2‐VASc score, univariate association between burden score and TTR ≥75% was limited to patients with CHA2DS2‐VASc ≥4. However, after multivariate adjustment this association did not reach significance (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.00–1.05 [P=0.072]) (Table S5). For the ACTS benefit score, there were no differences across score quartiles for TTR (both ≥75% and ≥60%) and warfarin discontinuation (Table 2). In multivariate analyses, there were no associations between benefit score and TTR or warfarin discontinuation in the full cohort, patients with CHA2DS2‐VASc <4, or patients with CHA2DS2‐VASc ≥4 (Table 3) (Tables S5 and S6).

Table 2.

Incidence of Warfarin and AF Outcomes by ACTS Quartile

| ACTS Benefit Score | Total (N=1513) | Quartile 1 (n=310) | Quartile 2 (n=379) | Quartile 3 (n=492) | Quartile 4a (n=332) | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTR ≥75%, No. (%)c | 503 (40.4) | 94 (36.4) | 119 (39.1) | 174 (42.8) | 116 (41.9) | 0.184 |

| TTR ≥60%, No. (%)c | 753 (62.8) | 153 (59.3) | 186 (61.2) | 269 (66.1) | 175 (63.2) | 0.100 |

| Warfarin discontinuation, No. (%)c | 300 (20.4) | 61 (20.5) | 76 (20.5) | 100 (20.8) | 63 (19.4) | 0.867 |

| Overall mortality (IR) | 160 (4.6) | 41 (5.7) | 32 (3.7) | 55 (4.8) | 32 (4.1) | 0.357 |

| Cardioembolic event (IR)d | 44 (1.3) | 6 (0.8) | 14 (1.6) | 16 (1.4) | 8 (1.0) | 0.847 |

| Major bleed (IR) | 106 (3.1) | 33 (4.8) | 21 (2.5) | 31 (2.8) | 21 (2.8) | 0.115 |

| All‐cause hospitalization (IR) | 810 (34.2) | 176 (37.5) | 214 (37.1) | 245 (31.0) | 175 (32.7) | 0.089 |

AF indicates atrial fibrillation, IR, incidence rate per 100 patient‐years of follow‐up; TTR, time in therapeutic range.

Anti‐Clot Treatment Scale (ACTS) score quartile with least burden or greatest benefit.

Differences between quartiles assessed using the chi‐squared test and Kruskal–Wallis test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Over 1 year.

Stroke, systemic embolism, transient ischemic attack.

Table 3.

Association of ACTS Scores With Warfarin and AF Outcomes

| Univariatea | Multivariatea , b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR/HRc (95% CI) | P Value | OR/HRc (95% CI) | P Value | |

| ACTS burden score | ||||

| TTR ≥75%d | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.018 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.153 |

| TTR ≥60%d | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.017 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.208 |

| Warfarin discontinuation | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 0.017 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.157 |

| Overall mortality | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.557 | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.515 |

| Cardioembolic evente | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | 0.206 | 1.05 (0.99–1.10) | 0.081 |

| Major bleed | 0.99 (0.96–1.01) | 0.349 | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.486 |

| All‐cause hospitalization | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.032 | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 0.141 |

| ACTS benefit score | ||||

| TTR ≥75%d | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 0.189 | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 0.446 |

| TTR ≥60%d | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | 0.160 | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 0.432 |

| Warfarin discontinuation | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 0.440 | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | 0.839 |

| Overall mortality | 0.97 (0.93–1.02) | 0.244 | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 0.682 |

| Cardioembolic evente | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) | 0.897 | 1.04 (0.95–1.13) | 0.427 |

| Major bleed | 0.96 (0.91–1.01) | 0.146 | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | 0.435 |

| All‐cause hospitalization | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.163 | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 0.830 |

Logistic regression: time in therapeutic range (TTR); Cox proportional hazard regression: warfarin discontinuation, overall mortality, cardioembolic event, major bleed, all‐cause hospitalization.

Covariates: patient demographics, medical history, atrial fibrillation (AF) history, medications, functional status, care model, and region (see Table S2 for full covariate list).

Odds ratio (OR)/hazard ratio (HR) per 1‐point increase in Anti‐Clot Treatment Scale (ACTS) scores.

Over 1 year.

Stroke/transient ischemic attack or systemic embolism.

Clinical Outcomes

After a mean follow‐up of 27.8±9.6 months, for the ACTS burden score, patient quartiles reporting less burden with warfarin therapy had a higher unadjusted incidence rate of ischemic stroke/transient ischemic attack or systemic embolism (quartile 4: 1.9 versus quartile 1: 1.0 per 100 patient‐years; P=0.026) and similar rates of overall mortality (quartile 4: 5.1 versus quartile 1: 4.4 per 100 patient‐years; P=0.450), major bleeds (quartile 4: 3.1 versus quartile 1: 3.2 per 100 patient‐years; P=0.893), and all‐cause hospitalization (quartile 4: 34.0 versus quartile 1: 37.7 per 100 patient‐years; P=0.517) (Table 2). In multivariate analyses, patient‐reported burden with warfarin therapy was not associated with clinical outcomes in the full cohort, patients with CHA2DS2‐VASc <4, or patients with CHA2DS2‐VASc ≥4 (Table 3) (Tables S5 and S6). For the ACTS benefit score, clinical outcomes were similar across score quartiles (Table 2) and, in multivariate analyses, the score was not associated with clinical outcomes in the full cohort (Table 3). For patients with CHA2DS2‐VASc ≥4, there was a borderline association between benefit score and overall mortality (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91–1.00 [P 0.047]) (Table S5). However, there was no association with benefit score and TTR or warfarin discontinuation to explain how a reduction in mortality would be mediated (Table 3) (Tables S5 and S6).

Discussion

In patients with AF taking warfarin in the ORBIT‐AF registry, patients most burdened by warfarin therapy were younger and more likely to be women, have paroxysmal AF, and be treated with antiarrhythmic drugs. ACTS burden and benefit scores were not associated with INR control, medication persistence, or clinical outcomes, suggesting that ACTS scores provide independent information beyond other traditional metrics of anticoagulation care quality.

Subjective burden of OAC is variable, influenced by patient values, preferences, and OAC strategy.16, 17, 18 Recognition of patient groups at high risk for dissatisfaction with warfarin therapy has the potential to improve quality‐adjusted life gains by increasing the chance that therapies are selected that reduce patient burden while improving outcomes. Whether patients at high risk for dissatisfaction with warfarin therapy, identified in our cohort, would be more satisfied with non–vitamin K antagonist OACs or left atrial appendage exclusion is currently unknown. However, higher ACTS scores for patients taking non–vitamin K antagonist OACs, as compared with warfarin, have been previously reported in various cohorts.19, 20, 21

TTR, a quality metric for warfarin therapy3 and determinant of outcomes,4, 5 is highly variable at the patient and site level,14 even within integrated healthcare systems.22 Low TTR has been associated with patient comorbidities and care pathways,14 with little investigation into the relationship between patient‐reported satisfaction with warfarin and TTR, which may be mediated through adherence. In ORBIT‐AF, patient quartiles reporting less burden from warfarin therapy had higher TTR. However, after multivariate adjustment, the association was not significant. Although one interpretation of these findings is that the ACTS score has limited utility to predict TTR over the subsequent year, clinicians cannot perform in‐office multivariate adjustment and the ACTS score may be a more realistic and convenient method to predict high TTR over the subsequent year. Patients predicted to have low TTR could receive more intensive INR monitoring or be considered for alternate strategies to reduce stroke risk. However, it is important to acknowledge that low TTR, caused by factors other than patient dissatisfaction, may be driving patient dissatisfaction.

ACTS scores were not associated with warfarin discontinuation, suggesting that factors other than patient satisfaction with warfarin therapy drive changes in OAC strategy. Potentially, provider preference may be the primary determinant of changes in OAC strategy, which is influenced by bleeding risk and events, frequent falls and frailty, and adherence and monitoring issues.23 Without mediation through higher TTR and less warfarin discontinuation, patient satisfaction with warfarin therapy was not associated with clinical outcomes. Importantly, higher unadjusted risk of stroke in quartiles reporting less burden is likely attributable to the older age of patients in these quartiles, with no association between ACTS burden score and stroke in the multivariate analysis.

Study Limitations

There are several important limitations to this study. The ACTS questionnaire is not designed to provide information on individual domains of patient satisfaction and we could not assess for associations between patient acceptance (of disease or therapy), self‐efficacy, or awareness and outcomes. Residual measured and unmeasured confounding could have influenced some of these findings, eg, duration of warfarin therapy before ACTS questionnaire administration. Importantly, patients’ perceived benefit and burden of OAC could have changed during follow‐up, which was not accounted for by our analytic methods. Finally, the ORBIT‐AF patient‐reported outcomes subcohort, despite baseline characteristics suggesting similarity with all patients treated with warfarin in the ORBIT‐AF cohort, may not be reflective of patients with AF at large.

Conclusions

In ORBIT AF, patient satisfaction was not associated with measurable differences in traditional metrics of anticoagulation care quality or clinical outcomes. Although patient satisfaction with warfarin does not appear to be a marker or target for improvements in TTR or warfarin discontinuation, determining patient satisfaction (or lack thereof) with OAC strategies is necessary to select therapies that minimize patient burden while improving clinical outcomes. Patients identified to be at high risk for dissatisfaction with warfarin therapy were younger and more likely to be women, have paroxysmal AF, and to be treated with antiarrhythmic drugs.

Sources of Funding

ORBIT‐AF is sponsored by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC (Raritan, NJ).

Disclosures

Turakhia receives research grants from Janssen, Medtronic Inc., AstraZeneca, Veterans Health Administration, and Cardiva Medical Inc; research support from AliveCor Inc., Amazon, Zipline Medical Inc., iBeat Inc., and iRhythm Technologies Inc.; and honoraria from Abbott, Medtronic Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim, Precision Health Economics, iBeat Inc., Akebia, Cardiva Medical Inc., and Medscape/theheart.org. Gersh serves as a consultant for Janssen, Cipla Limited Data Safety Monitoring Board for Mount Sinai St. Lukes, Boston Scientific, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, St. Jude Medical, Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Thrombosis Research Institute, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University, Kowa Research Institute, and the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Fonarow serves as a consultant for Janssen. Go receives research support from Johnson & Johnson. Hylek receives honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim and Bayer and serves as a consultant for Daiichi Sankyo, Ortho‐McNeil‐Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb. Kowey serves as a consultant for Johnson & Johnson, Daiich‐Sankyo, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Singer receives research support from Daiichi Sankyo and serves as a consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, and Sanofi‐Aventis. Thomas receives research support form Novartis, Boston Scientific, Gilead Sciences Inc., and Janssen. Steinberg receives research support from Boston Scientific and Janssen and serves as a consultant for Biosense‐Webster. Peterson receives research support from Janssen and Eli Lilly and serves as a consultant for Janssen and Boehringer Ingelheim. Piccini receives research support from Abbott, ARCA biopharma, Boston Scientific, Gilead, Janssen, and Verily. Mahaffey receives research support from Abbott, Afferent, Amgen, Apple Inc., AstraZeneca, Cardiva Medical Inc., Daiichi, Ferring, Johnson & Johnson, Luitpold, Medtronic, Merck, NIH, Novartis, Sanofi, Tenax, and Verily and serves as a consultant for Abbott, Ablynx, AstraZeneca, Baim Institute, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Elsevier, Glaxo Smith Kline, Johnson & Johnson, Medergy, Medscape, Mitsubishi, Myokardia, National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Portola, Radiometer, Regeneron, Springer Publishing, and University of California, San Francisco. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Table S1. ACTS Questionnaire

Table S2. Multivariate Model Covariates

Table S3. Baseline Characteristics of Patients in ORBIT‐AF (Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation) on Warfarin by Study Inclusion Status*

Table S4. Baseline Characteristics by ACTS Benefit Score Quartile

Table S5. Association of ACTS Scores With Warfarin and AF Outcomes in Patients With CHA2DS2‐VASc ≥4

Table S6. Association of ACTS Scores With Warfarin and AF Outcomes in Patients With CHA2DS2‐VASc <4

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011205 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011205.)

References

- 1. Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient‐centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:351–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rose AJ, Hylek EM, Ozonoff A, Ash AS, Reisman JI, Berlowitz DR. Risk‐adjusted percent time in therapeutic range as a quality indicator for outpatient oral anticoagulation: results of the Veterans Affairs Study to Improve Anticoagulation (VARIA). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Connolly SJ, Pogue J, Eikelboom J, Flaker G, Commerford P, Franzosi MG, Healey JS, Yusuf S; ACTIVE W Investigators . Benefit of oral anticoagulant over antiplatelet therapy in atrial fibrillation depends on the quality of international normalized ratio control achieved by centers and countries as measured by time in therapeutic range. Circulation. 2008;118:2029–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. White HD, Gruber M, Feyzi J, Kaatz S, Tse HF, Husted S, Albers GW. Comparison of outcomes among patients randomized to warfarin therapy according to anticoagulant control: results from SPORTIF III and V. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Piccini JP, Fraulo ES, Ansell JE, Fonarow GC, Gersh BJ, Go AS, Hylek EM, Kowey PR, Mahaffey KW, Thomas LE, Kong MH, Lopes RD, Mills RM, Peterson ED. Outcomes registry for better informed treatment of atrial fibrillation: rationale and design of ORBIT‐AF. Am Heart J. 2011;162:606–612.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cullen MW, Kim S, Piccini JP Sr, Ansell JE, Fonarow GC, Hylek EM, Singer DE, Mahaffey KW, Kowey PR, Thomas L, Go AS, Lopes RD, Chang P, Peterson ED, Gersh BJ; ORBIT‐AF Investigators . Risks and benefits of anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation: insights from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT‐AF) registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:461–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steinberg BA, Kim S, Piccini JP, Fonarow GC, Lopes RD, Thomas L, Ezekowitz MD, Ansell J, Kowey P, Singer DE, Gersh B, Mahaffey KW, Hylek E, Go AS, Chang P, Peterson ED; ORBIT‐AF Investigators and Patients . Use and associated risks of concomitant aspirin therapy with oral anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT‐AF) Registry. Circulation. 2013;128:721–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cano SJ, Lamping DL, Bamber L, Smith S. The Anti‐Clot Treatment Scale (ACTS) in clinical trials: cross‐cultural validation in venous thromboembolism patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bamber L, Wang MY, Prins MH, Ciniglio C, Bauersachs R, Lensing AW, Cano SJ. Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction with oral rivaroxaban versus standard therapy in the treatment of acute symptomatic deep‐vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:732–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prins MH, Bamber L, Cano SJ, Wang MY, Erkens P, Bauersachs R, Lensing AW. Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction with oral rivaroxaban versus standard therapy in the treatment of pulmonary embolism; results from the EINSTEIN PE trial. Thromb Res. 2015;135:281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Berkowitz SD, Fox KA, Califf RM, ROCKET AF Investigators . Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wieloch M, Sjalander A, Frykman V, Rosenqvist M, Eriksson N, Svensson PJ. Anticoagulation control in Sweden: reports of time in therapeutic range, major bleeding, and thrombo‐embolic complications from the national quality registry AuriculA. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2282–2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pokorney SD, Simon DN, Thomas L, Fonarow GC, Kowey PR, Chang P, Singer DE, Ansell J, Blanco RG, Gersh B, Mahaffey KW, Hylek EM, Go AS, Piccini JP, Peterson ED; Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators . Patients’ time in therapeutic range on warfarin among US patients with atrial fibrillation: results from ORBIT‐AF registry. Am Heart J. 2015;170:141–148, 148.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schulman S, Kearon C; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis . Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non‐surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:692–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilke T, Bauer S, Mueller S, Kohlmann T, Bauersachs R. Patient preferences for oral anticoagulation therapy in atrial fibrillation: a systematic literature review. Patient. 2017;10:17–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gage BF, Cardinalli AB, Owens DK. The effect of stroke and stroke prophylaxis with aspirin or warfarin on quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1829–1836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wyld ML, Clayton PA, Morton RL, Chadban SJ. Anti‐coagulation, anti‐platelets or no therapy in haemodialysis patients with atrial fibrillation: a decision analysis. Nephrology. 2013;18:783–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coleman CI, Haas S, Turpie AG, Kuhls S, Hess S, Evers T, Amarenco P, Kirchhof P, Camm AJ; XANTUS Investigators . Impact of switching from a vitamin K antagonist to rivaroxaban on satisfaction with anticoagulation therapy: the XANTUS‐ACTS substudy. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39:565–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hanon O, Chaussade E, Gueranger P, Gruson E, Bonan S, Gay A. Patient‐reported treatment satisfaction with rivaroxaban for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. A French observational study, the SAFARI Study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Contreras Muruaga MD, Vivancos J, Reig G, Gonzalez A, Cardona P, Ramirez‐Moreno JM, Marti J, Fernandez CS; ALADIN Study Investigators . Satisfaction, quality of life and perception of patients regarding burdens and benefits of vitamin K antagonists compared with direct oral anticoagulants in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Comp Eff Res. 2017;6:303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Razouki Z, Ozonoff A, Zhao S, Jasuja GK, Rose AJ. Improving quality measurement for anticoagulation: adding international normalized ratio variability to percent time in therapeutic range. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:664–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. O'Brien EC, Simon DN, Allen LA, Singer DE, Fonarow GC, Kowey PR, Thomas LE, Ezekowitz MD, Mahaffey KW, Chang P, Piccini JP, Peterson ED. Reasons for warfarin discontinuation in the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT‐AF). Am Heart J. 2014;168:487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. ACTS Questionnaire

Table S2. Multivariate Model Covariates

Table S3. Baseline Characteristics of Patients in ORBIT‐AF (Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation) on Warfarin by Study Inclusion Status*

Table S4. Baseline Characteristics by ACTS Benefit Score Quartile

Table S5. Association of ACTS Scores With Warfarin and AF Outcomes in Patients With CHA2DS2‐VASc ≥4

Table S6. Association of ACTS Scores With Warfarin and AF Outcomes in Patients With CHA2DS2‐VASc <4