Abstract

Objective:

Postponing childbearing is becoming increasingly common among higher education students. The awareness about the extent of the age-related decline in female fertility is unknown in Saudi Arabia. The main aim of the study was to assess fertility awareness, particularly age-related fertility decline, and attitudes toward parenthood.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted utilizing a self-administered questionnaire which was filled by 248 female students in multiple colleges at King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Science (KSAU-HS). The questionnaire adapted from the Swedish Fertility Awareness Questionnaire; it contains 31 items that can be grouped into five categories: Sociodemographic characteristics, the future intention of having children, important circumstances for the decision to have children, which have seven items, participant perception regarding motherhood impact on life, and knowledge about fertility issues.

Results:

Nearly 80% of undergraduate female students want to have children. They have a positive attitude toward parenthood. On the other hand, 85% of the respondents plan to postpone having children until they finish their studies and have a stable career.

Conclusion:

The study revealed that most of the students are concerned about childbearing. However, the participants are not aware of the decline in fertility caused by aging. More effort should be directed toward spreading awareness regarding age-related fertility decline among health profession students and the general population.

Keywords: Attitudes, Awareness, Female students, Fertility, Parenthood

Introduction

Maturation of female reproductive cells “germ cells” is called oogenesis, which begins before birth, and by the 5th month of gestation, the number of these cells reaches its maximum of about 6–7 million.[1] At birth, the estimated number of germ cells varies from 600,000 to 800,000 cells. Only 40,000 of these remain until puberty, and fewer than 500 are released from the ovaries.[2] The number of germ cell follicles is the best indicator of women’s natural capability to produce offspring, which is known as fertility.[3] Starting from their late 20 s to 30 s, the number of germ cell follicles decreases. At the age of 40 years, fertility capacity decreases more rapidly and might lead to infertility.[3] According to the WHO, infertility is a disease of the reproductive system defined as the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse.[4] Furthermore, women in their late 30 s and 40 s have a higher chance of birth-related complications and genetic abnormalities.[1]

According to the general authority for Statistics in Saudi Arabia, the fertility rate has dropped sharply the past few years.[5] This was depicted by the fertility rate curve for Saudi women, as the average number of live births delivered by a woman who passed the climacteric age (45–49) was 4.9 live children. In the other hand, today number of live children delivered by a Saudi woman reaches 2.4.[5]

There are many international studies related to fertility awareness, but to the best our knowledge, little information is found in Saudi Arabia. For instance, a current study conducted in Riyadh among King Saud University women revealed that education played a major role on fertility as it affected age at marriage, ideal family size, intended number of children, and contraception use.[6] In addition, Saudi Arabia has a well-known cultural and traditional values of high fertility.[6]

However, with the revolution of women’s education, there has been a delay in marriages, limitation or a delay in birth, and use of the contraceptive method. Thus, the level of women’s education in addition to the absence of awareness regarding their fertility window and the consequences behind delaying or postponing childbirth affected the fertility rate in Saudi Arabia.[6]

For international studies, there were multiple across different countries conducted in a Danish, Swedish, and Iraqi universities among male and female students to assess their awareness and knowledge about fertility and willingness for parenthood. It was concluded that most of the students want to have children in the future, so they believe that becoming a parent is important. However, most of these students lack knowledge of female fertility rate reduction as she gets older. As a result, students wanted to have their first child during their late 20 s or later, and only a minority were aware of the decrease in women’s fertility in their late 20 s. Therefore, they tend to overestimate age where fertility declines assuming that the decline begins after the age of 45 years.

Furthermore, they had optimistic thoughts regarding the help of in vitro fertilization (IVF) in attempting successful pregnancy.

Most students believed that there are some conditions which are important before approaching parenthood; such as a stable relationship, maturity, responsibility sharing with a partner, a good economy, access to childcare, and a job that is flexible and accommodates.[7-10]

Similarly, the results of studies conducted among American, Australian, and Ukrainian university students to assess fertility awareness, intentions, and expectations for future parenthood were similar regarding the knowledge of female fertility age reduction, which showed that 9 in 10 participants want to have children in the future, and viewed parenthood as a highly important aspect of their future lives.

On the other hand, results demonstrated an overestimation of the age at which women experience declines in fertility. Most of the students underestimated the impact of female and male age on fertility decline (>75% and >95%, respectively).[12] Furthermore, many students in these studies expected to achieve several life goals including career completion before becoming parents.[11-13]

Other studies conducted in fertility clinics in the United States (US), among women working in the labor force, have concluded that there is an association between the postponement of the first child and the mother’s education degree or career.[14] This association is due to multiple factors, including the awareness of IVF techniques and overestimating their effectiveness.

In addition, avoidance of motherhood wage penalty, having unstable income, and multiple partners were all contributing factors in the postponement of the first child and the eventual consequence of involuntary decreased fertility, or worse infertility.[14,15]

Among unmarried Chinese undergraduate students, results showed that they overestimate the optimal age of fertility, and underestimated the decline in fertility before the age of 30 years. Furthermore, when asked to rate the importance of having children, they scored lower compared to previous studies, for instance, American, Australian, and Ukrainian students.

Probably, people who live in a developed country such as China have the most significant low intention of fertility due to lifestyle demands, career seeking goals, and ensuring economic stability. Furthermore, the age at which Chinese students wanted to have their first child is approximately 30 years, and the age at which they plan to have their last child is around mid-thirties.[16]

For the above reasons, postponing childbirth is becoming more common among young-aged college students who have reached childbearing age. However, it seems that these students are not fully aware of the age-related decline in female fertility.

The main aim of this study is to assess awareness about the age-related decline in fertility, identifying intentions concerning childbearing among medical students, as well as other health professions students who are enrolled at King Saud bin Abdulaziz University in Riyadh.

Methods

Study setting and participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted among female undergraduate students at King Saud bin Abdulaziz University in Riyadh.

The study was carried out from January 2017 to April 2017. We assumed a 5% margin of error and a confidence level of 95%, and with the help of Raosoft sample size calculator 13, the minimum number of students to be included was 248.[17] Inclusion criteria were: Saudi females, ≥18-years-old, enrolled at King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Science (KSAUHS) and registered as an active student in 2016–2017. Exclusion criteria were: Pre-health science students.

Measures

The study was conducted utilizing a self-administrated questionnaire adapted and modified from a Swedish published study, and permission was gained from the author.[11] The questionnaire was modified to fit the local cultural background and pilot tested among 10 students from the five colleges (College of Medicine, College of Nursing, College of Pharmacy, College of Dentistry, and College of Applied Medical Sciences). As a result, instruments have shown good validity, reliability, and established consistency (Cronbach’s alpha >0.7). The questionnaire is comprised 31 items that can be grouped into five categories. These categories include sociodemographic characteristics, the future intention of having children, important circumstances for the decision to have children, which have seven items, participant perception regarding motherhood impact on life, and knowledge about fertility issues.

Procedures

After validation, questionnaires were distributed through convenient sampling technique by the coinvestigators (six female medical students) who were assigned to different colleges, two for the medical college, one for nursing, one for dentistry, one for pharmacy, and one for applied medical sciences. The total sample collected was 322.

The questionnaires were filtered according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 64 questionnaires which do not meet the eligibility criteria or were incompletely filled were excluded. The net sample used was 248, and the response rate was calculated by dividing the number of responses by the total number of distributed questionnaires.

Descriptive analysis was used to describe the data, and the mean standard deviation (SD) was used to describe parametric continuous variables. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. Students’ perception of fertility issues at different ages was calculated and compared between the students from different colleges. The Chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical data. P < 0.05 was considered to show a statistically significant difference. Data were analyzed using the SPSS database (IBM SPSS Statistics, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

Ethical considerations

Consent form was provided to students. All students’ responses were only identified by researchers, providing full confidentiality and anonymity of collecting information in a manner that avoided identifying information, such as students’ names. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board in King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre.

Results

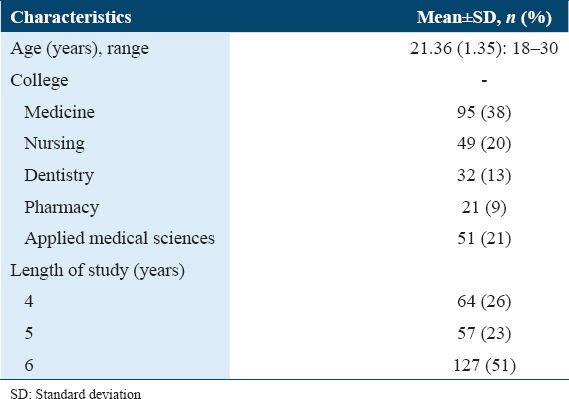

A total of 248 female students from five different colleges responded to the questionnaire. Of these, 95 (38%) were from the College of Medicine, 51 (21%) were from the College of Applied Medical Sciences, 32 (13%) were from the College of Dentistry, 49 (20%) were from the College of Nursing, and 21 (9%) were from the College of Pharmacy. The demographic characteristics of the students are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants, female participants (n=248)

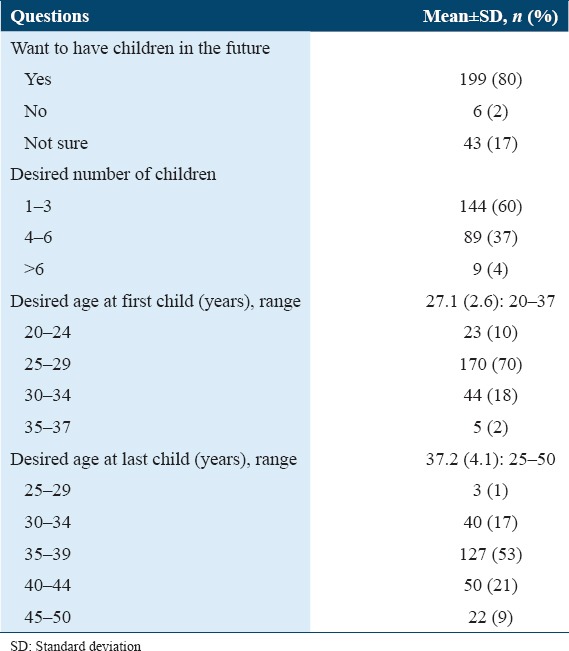

The mean age of the enrolled students was 21.3 years (SD = 1.35). As shown in Table 2, most students (80%) expressed that they wanted to have children sometime in the future, while 17% were not sure and 2% do not consider having children.

Table 2.

Intentions of having children, female participants (n=248)

Majority of the students (60%) desired to have between 1 and 3 children. Moreover, most of the students (70%) wanted to have their first child between the ages of 25–29 years (27.1 ± 2.6) and the last child at 35–39 years (mean age 37.2 ± 4.1).

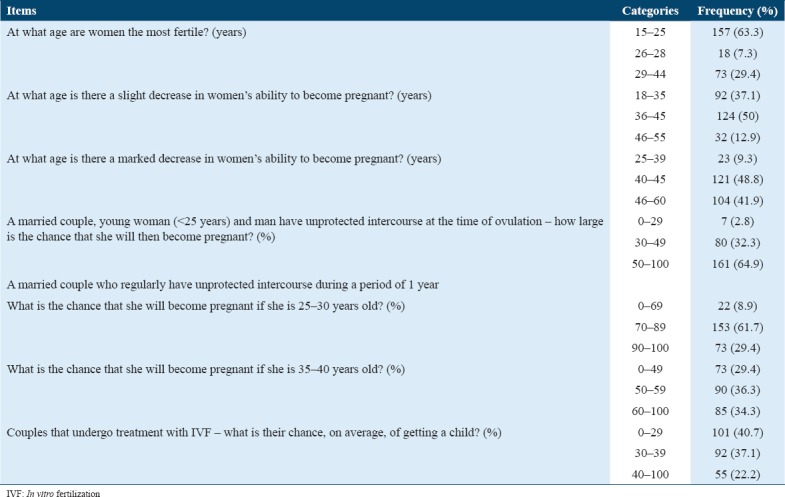

As explained in Table 3, students’ perceptions about the most fertile and infertile age are considerable, as the majority of 157 (63%) believe that the most fertile age is 15–25 years. However, a large percentage around (29%) 73 considers 29–44 years to be the most fertile age. Regarding a married couple with unprotected intercourse, 161 (65%) students believe in that if the women age is (<25 years) there is a high chance of getting pregnant.

Table 3.

Student’s awareness of fertility issues, female participants (n=248)

During a period of 1 year of unprotected intercourse, 153 (62%) students agreed that a woman has a 70–100% chance to become pregnant if she is 25–30-years-old, compared to only 85 (34%) of students think that the chance will be 60–100% if she is 35–40 years old. 55 (22%) students overestimate the success rate of IVF treatment.

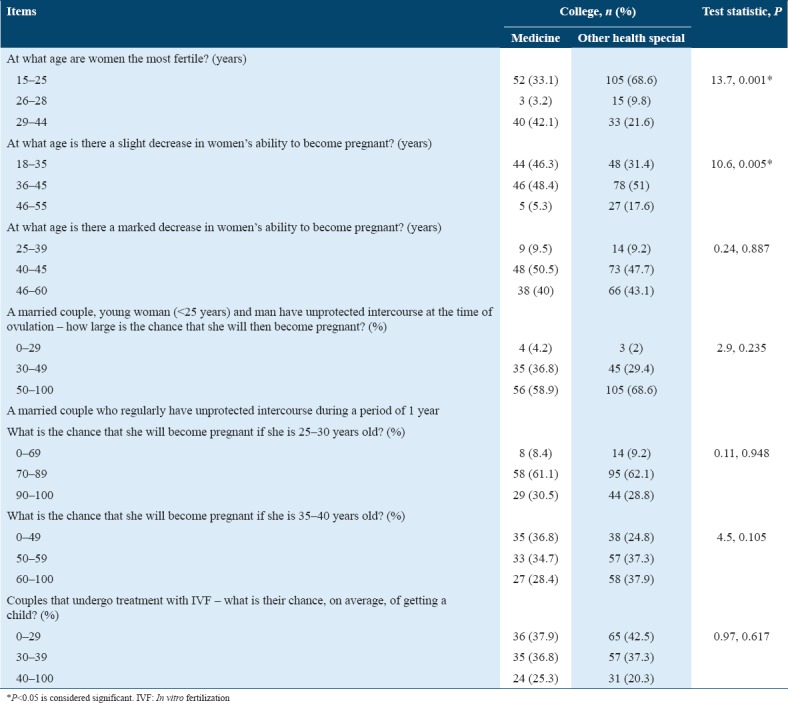

Table 4 shows the differences in awareness of fertility issues by students in the college of medicine and other health professions students. Surprisingly, medical students are less aware of the age at which a woman is most fertile, as only 52 (33.1%) of medical students believe that a woman is most fertile at 15–25 years old, whereas the percentage is 68.6% in other health specialties (P = 0.001). Medical students agreed that there is a slight decrease in women fertility by age 18–35 years (46.3%), while in other colleges this proportion was 31.4% of the students (P = 0.005). Students’ knowledge is about the chance of having a child for couples that used IVF treatment is similar; 37% in both cases.

Table 4.

Student’s awareness of fertility issues by colleges, female participants (n=248)

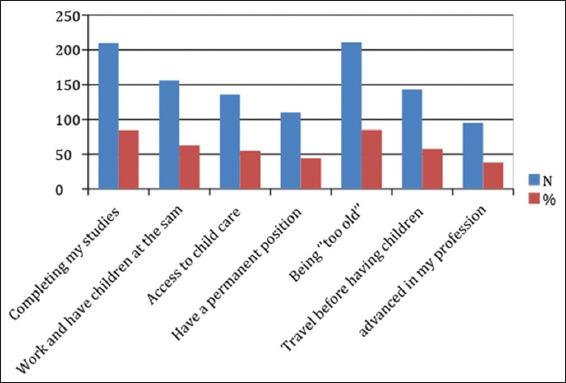

The students reported circumstances likely to affect their decision to have children [Figure 1]. 210 (85%) students out of 248 considered having children only after completing their studies, 156 (63%) students desired to have children only if they can balance work and child responsibilities at the same time.

Figure 1.

Important circumstances for students’ decision to have children

Furthermore, 110 (44.4%) students want a permanent job position before having children. A total of 211 (85.1%) and 143 (58%) students emphasized having children before they get too old and having the opportunity to travel and do things that might be difficult to do with children, respectively. Access to childcare is an essential condition before having children for 136 (55%) students. A total of 95 (38%) students want to have children after they have advanced in their career.

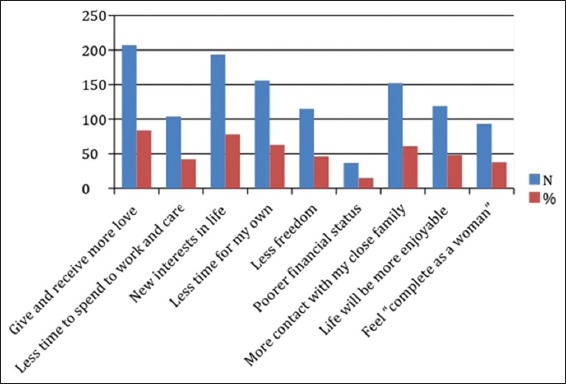

Figure 2 illustrated that student’s opinions on the impact of motherhood. Most of the students highly expect that motherhood would affect their lives in multiple aspects, such as giving and receiving more love and having new interests in their lives, which may limit freedom and work time.

Figure 2.

Student’s opinion on the impact of motherhood

Only 37 (15%) students presumed that motherhood would affect their financial status poorly, and 119 (48%) students believed that their life as a mother would be pleasant. Furthermore, 93 (38%) students believed that being a mother does not mean being complete as a woman.

Discussion

This study assessed fertility awareness (particularly age-related fertility decline) among health professions female students. The study also identified intentions concerning childbearing and assessed the attitude toward parenthood among study participants. After conducting a cross-sectional study among female undergraduate students, the results were compared to similar studies done previously in Iraq and Sweden.[7,11] All of these studies report an overestimation of female fertility.

Results of our study show that the majority of the health-care professions students in KSAU-HS showed a positive attitude and strong desire to have children, as most students expressed that they wanted to have children in the future. This is in contrast to a study done among Chinese undergraduate students, which demonstrated a much lower desire to have children.[10]

Students wanted to have from one to three children and stated that they desired to have their first child in their late 20 s. However, they also want to have the last child in their late 30 s, an age at which fertility is decreased. This result is similar to the findings of studies done in Sweden, Iraq, and the US.[7,8,11] Moreover, the majority of the students expected that motherhood would affect their lives, which influenced more students to adopt the choice of having children after they have advanced in their career. Furthermore, students in the study have many considerations that they regard as important in the decision to have children, some of which might further delay childbearing to the time where fertility is decreased.

For example, the clear majority of students considered study completion, the ability to combine work and child responsibility, and advancing in their career as important circumstances before having children. This affects fertility and obstetric and perinatal outcomes.

The participants believe that women are most fertile between 15 and 25 years old, which indicates good knowledge regarding women fertility. Regarding having a child through IVF, the students’ opinion is reasonable not overestimated as other studies that were done in Iraq, Sweden, Hong Kong, and the US.

Conclusion/Recommendation

The findings of this study revealed that most medical and other health profession students are concerned about childbearing and their decision to have children is considered according to important circumstances for them. For example, they prefer to complete their study before having children. Most participants plan to have children at ages when female fertility is decreased without being sufficiently aware of the age-related decline in fertility.

Education regarding fertility issues is necessary to help men and women make informed reproductive decisions that are based on accurate information rather than incorrect perceptions. Therefore, it is important to give more effort, especially for health profession students, who are concerned about higher education.

References

- 1.Sherwood L. Human Physiology. Australia: Thomson/Brooks/Cole; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadler T, Langman J. Langman's Medical Embryology. Philadelphia: Lippincott William and Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matlin M. The Psychology of Women. Australia: Wadsworth Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zegers FH, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, Ishihara O, Mansour R, Nygren K, et al. The International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) Revised Glossary on ART Terminology. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.General Authority for Statistics. Saudi Arabia: 2016. [[Last accessed on 2018 Dec 02]]. Available from: https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/en-demographic-research-2016_2.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khraif RM, Salam AA, Al-Mutairi A, Elsegaey I, Al Jumaah A. Education's impact on fertility:The case of king Saud university women, Riyadh. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2017;22:125–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sørensen NO, Marcussen S, Backhausen MG, Juhl M, Schmidt L, Tydén T, et al. Fertility awareness and attitudes towards parenthood among Danish university college students. Reprod Health. 2016;13:146. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0258-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khalil N, Hassan I, Saeed H. Fertility awareness among medical and non-medical undergraduate university students in Al-Iraqia University, Baghdad. Iraq Am J Med Sci. 2015;3:74–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tydén T, Svanberg AS, Karlström PO, Lihoff L, Lampic C. Female university students'attitudes to future motherhood and their understanding about fertility. Eur J Contracept Reprod. 2006;11:181–9. doi: 10.1080/13625180600557803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lampicc W, Svanberg A, Karlström P, Tydén T. Fertility awareness, intentions concerning childbearing, and attitudes towards parenthood among female and male academics. Hum Reprod. 2005;21:558–64. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson BD, Pirritano M, Tucker L, Lampic C. Fertility awareness and parenting attitudes among American male and female undergraduate university students. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1375–82. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prior E, Lew R, Hammarberg K, Johnson L. Fertility facts, figures and future plans:An online survey of university students. Hum Fertil. 2018;13:1–8. doi: 10.1080/14647273.2018.1482569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mogilevkina I, Stern J, Melnik D, Getsko E, Tydén T. Ukrainian medical students'attitudes to parenthood and knowledge of fertility. Euro J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21:189–94. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2015.1130221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dougall K, Beyene Y, Nachtigall RD. Age shock:Misperceptions of the impact of age on fertility before and after IVF in women who conceived after age. Hum Reprod. 2013;2:350–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills M, Rindfuss R, McDonald P, Velde E. Why do people postpone parenthood?Reasons and social policy incentives. Hum Reprod. 2011;17:848–60. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan C, Chan T, Peterson B, Lampic C, Tam M. Intentions and attitudes towards parenthood and fertility awareness among Chinese university students in Hong Kong:A comparison with Western samples. Hum Reprod. 2014;30:364–72. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raosoft.com. Sample size calculator by Raosoft, Inc 2018. [[Last accessed on 2018 Feb 03]]. Available from: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html .