Key Points

Question

How may consensus be reached in developing outcome measurement tools for evaluating the quality of care provided to pediatric patients with facial palsy?

Findings

In this study involving 21 health care professionals, researchers, and patient representatives, a standard set of outcome measurements was established, including patient-, clinician-, and patient proxy–reported clinimetric and psychometric tools deemed essential to determining the outcomes most important to children with facial palsy.

Meaning

Comprehensive outcome measurement is considered essential to evaluating different interventions, facilitating benchmarking of clinicians, and introducing value-based reimbursement strategies in the pediatric facial palsy field.

Abstract

Importance

Standardization of outcome measurement using a patient-centered approach in pediatric facial palsy may help aid the advancement of clinical care in this population.

Objective

To develop a standardized outcome measurement set for pediatric patients with facial palsy through an international multidisciplinary group of health care professionals, researchers, and patients and patient representatives.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A working group of health care experts and patient representatives (n = 21), along with external reviewers, participated in the study. Seven teleconferences were conducted over a 9-month period between December 3, 2016, and September 23, 2017, under the guidance of the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement, each followed with a 2-round Delphi process to develop consensus. This process defined the scope, outcome domains, measurement tools, time points for measurements, and case-mix variables deemed essential to a standardized outcome measurement set. Each teleconference was informed by a comprehensive review of literature and through communication with patient advisory groups. Literature review of PubMed was conducted for research published between January 1, 1981, and November 30, 2016.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The study aim was to develop the outcomes and measures relevant to children with facial palsy as opposed to studying the effect of a particular intervention.

Results

The 21 members of the working group included pediatric facial palsy experts from 9 countries. The literature review identified 1628 papers, of which 395 (24.3%) were screened and 83 (5.1%) were included for qualitative evaluation. A standard set of outcome measurements was designed by the working group to allow the recording of outcomes after all forms of surgical and nonsurgical facial palsy treatments among pediatric patients of all ages. Unilateral or bilateral, congenital or acquired, permanent or temporary, and single-territory or multiterritory facial palsy can be evaluated using this standard set. Functional, appearance, psychosocial, and administrative outcomes were selected for inclusion. Clinimetric and psychometric outcome measurement tools (clinician-, patient-, and patient proxy–reported) and time points for measuring patient outcomes were established. Eighty-six independent reviews of the standard set were completed, and 34 (85%) of the 40 patients and patient representatives and 44 (96%) of the 46 health care professionals who participated in the reviews agreed that the standard set would capture the outcomes that matter most to children with facial palsy.

Conclusions and Relevance

This international collaborative study produced a free standardized set of outcome measures for evaluating the quality of care provided to pediatric patients with facial palsy, allowing benchmarking of clinicians, comparison of treatment pathways, and introduction of value-based reimbursement strategies in the field of pediatric facial palsy.

Level of Evidence

NA.

This study describes the complete process, outcomes, and advantages of developing a standard set of outcome measures for children who undergo treatments for facial palsy.

Introduction

Facial palsy can profoundly affect the functional and psychosocial well-being of patients.1 In the pediatric population, this burden is borne by both the affected children and their family. Efforts to evaluate outcomes within this patient group have generated a vast spectrum of measurement tools.2,3 Despite extensive efforts to create a universal instrument with which to evaluate the outcomes of patients with facial palsy, lack of consensus on the optimal tool remains.4

Patient outcomes play a central role in value-based health care.5 In this model, the value of care delivered considers both the outcomes achieved and the costs incurred in delivering them.6 In applying the value-based health care model, disease-specific outcomes that matter most to patients must first be defined and then applied to the end point of care, considering both clinical and psychosocial patient well-being.

Defining the most relevant outcome domains necessitates a collaborative approach between patients and health care professionals. This process can be facilitated by the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM; http://www.ichom.org), a nonprofit organization that aims to unlock the potential of value-based health care across the globe. The consortium works with leading physicians, outcome researchers, and patient advocates to define a core set of outcomes per medical condition that matter most to patients. Currently, 23 ICHOM standard sets have been produced that cover 53.7% of the global disease burden.7,8,9,10,11,12,13

To date, no consensus guidelines exist on which outcome domains and measurement tools best assess the quality of care delivered to children with facial palsy. This study presents a standardized outcome measurement set for pediatric facial palsy created through an international, multidisciplinary approach involving both patients and health care professionals.

Methods

The study protocol was reviewed by the ICHOM Institutional Review Board (IRB) and was subsequently exempted from IRB oversight. Participation in the study was voluntary, and each participant signed an informed consent form.

Standard Set Development

The process of developing a standardized set of outcome measures for pediatric facial palsy was initiated by ICHOM. An international working group of health care professionals, researchers, and patient advocates was convened. Within the working group was a core group of 5 individuals who coordinated the activities of the working group. Emphasis was placed on creating a standardized outcome measurement set that could be used in routine, day-to-day clinical practice anywhere in the world. Through a series of seven 90-minute teleconferences between December 3, 2016, and September 23, 2017, the working group followed a structured process under the guidance of ICHOM. This process involved defining the patient population, outcome domains, associated measurement tools and time points for their measurement, and relevant case-mix variables to aid patient stratification and comparison.

The contents of each teleconference were informed by a comprehensive review of the existing literature and through communication with patient advisory groups. Literature review of PubMed was conducted for research published between January 1, 1981, and November 30, 2016. The following search terms were used: facial palsy OR facial paralysis, AND paediatric OR pediatric OR congenital or developmental, AND outcome or outcomes. In addition, relevant studies identified through review of the reference lists of the articles found from the PubMed search were included.

The outcome measurement tools selected could be clinician reported, patient reported, patient proxy reported, or based on administrative data. The tools were systematically evaluated on psychometric quality (using the International Society for Quality of Life Research criteria), feasibility of measurement, and implementation. If no suitable existing outcome measurement tool was identified, the working group generated relevant yes-or-no questions to evaluate the domain in question. Binominal answers were selected to make data actionable and facilitate a clinical decision-making process. Efforts were made to balance comprehensiveness with practicality when determining the breadth of outcome domains and measurement tools to be included in the standard set.

Working Group Consensus and Patient Participation

After each teleconference, a 2-round modified Delphi process was undertaken to reach consensus on proposals.14 Each proposal required that at least 80% of the working group scored a proposal item 7 to 9 points on a 9-point Likert scale. All inconclusive domains were presented again to the group for voting, along with the feedback and the analysis of the distribution of the working group votes for each item. If no consensus was reached, the item was reevaluated by the core group and a new proposal put to the working group. An 80% response rate from the working group was required for each survey to be considered valid. This method was used to generate consensus on the outcome domains, measurement tools, and case-mix variables. Patient representatives participated in the entire process as working group members. All outcomes deemed essential from patients and patient representatives were discussed during the teleconference and submitted for a new Delphi process if not initially selected by the working group.

To ensure that the recommendations of the working group reflected what is important to patients, ICHOM ran 3 patient advisory groups. Patients were invited to participate through patient organizations. The patient advisory groups comprised adult patients with a facial palsy diagnosis during their childhood or parents of children with facial palsy. The teleconferences were conducted in the English language. Participant confidentiality was protected through deidentification of the data, and only the themes drawn from the advisory group discussion were presented to the working group.

The proposed list of outcomes was reviewed through an online anonymized survey (available in English or Spanish), which was distributed through national and international patient organizations (Facial Paralysis and Bell’s Palsy Foundation, Changing Faces UK, and Patients for Patient Safety of the World Health Organization). Participants were asked to rate the importance of each outcome on a 9-point Likert scale (1 indicating no agreement, and 9 indicating strong agreement) with the option of including additional outcomes in text form.

Standard Set Appraisal by Health Care Experts

Health care professionals with expertise in pediatric facial palsy were invited to review the completed standard set and complete an online survey. The web link to the survey was distributed by working group members to their contacts in the pediatric facial palsy field, at medical conferences, and through the facial palsy–specific Sir Charles Bell Society.

Results

The working group comprised 21 members. Pediatric facial palsy experts from Australia, Canada, Finland, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States participated in the process. The group included 3 patient advocates as well as plastic surgeons, a neurologist, physiotherapists, a sociologist, facial retraining specialists, occupational therapists, a psychologist, otolaryngologists, and oculoplastic and maxillofacial surgeons. All of these members completed at least 80% of the online surveys. The literature review identified 1628 papers. Of these studies, 395 (24.3%) were screened and 83 (5.1%) were included for qualitative evaluation.

Standard Set Scope

The standard set can be applied to all patients younger than 18 years who present with a facial palsy of any duration. The facial palsy can be either congenital or acquired and unilateral or bilateral. Both single-territory and multiterritory facial nerve palsy are eligible for inclusion. The working group elected that the standard set would not be suitable for patients whose facial palsy was part of a wider cognitive, systemic, or neurological disorder because the condition would make comparisons unreliable or require specific treatment interventions.

The treatment options that can be evaluated with the standard set are medical treatment, surgical treatment, eye protection intervention, physical therapy, psychological therapy, speech therapy, and botulinum toxin treatment.

Outcome Domains

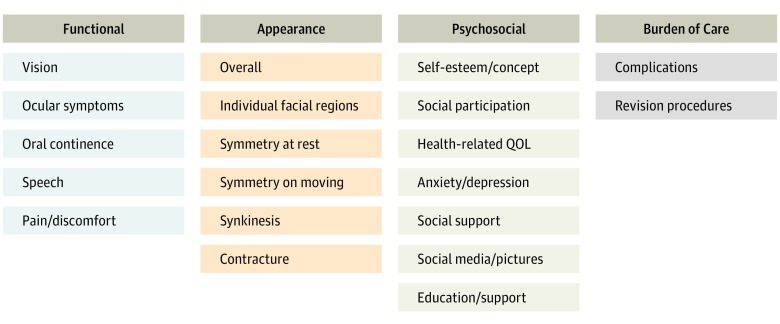

The domains selected for inclusion in the standard set are shown in Figure 1. The patient advisory group encouraged the inclusion of a domain that evaluated the patient’s comfort in engaging with photographs and social media, and this inclusion was supported by the working group. Furthermore, the working group believed there would be value in collecting data on the extent of written and verbal information provided about the patient’s condition and treatment and the resources available to support those affected (Education/Support domain).

Figure 1. Outcome Domains Evaluated by the Standard Set.

QOL indicates quality of life.

A number of administrative outcome domains were put forward in the initial proposal to the working group; these domains included length of stay and number of hospital appointments. It was decided that these items did not warrant inclusion in a core standard set because they were likely to be affected by clinician preference and the practicalities of the health care system in question and would, therefore, not add value to the set. The complications were grouped into bleeding, infection, wound healing, and general medical (Box).

Box. Complications and Case-Mix Variables.

Complications Recorded in the Standard Set

Bleeding Complication

Hematoma

Bleeding requiring return to operating room

Infectious Complication

Cellulitis

Abscess

Prosthetic material infection

Wound Healing Complication

Partial dehiscence

Complete dehiscence

Skin flap necrosis

Parotid fistula

Reexploration of flap

Flap failure

Hypertrophic/keloid scar

General Medical Complication

Disease-specific mortality

Case-Mix Variables Recorded for Risk Stratification

Demographic Variables

Age at presentation

Sex

Insurance status

Parent education

Transfer of care

Previous loss to follow-up

Clinical Variables

Origin of facial palsy

Permanent vs resolving facial palsy

Comorbidities

Baseline Condition Variables

Severity of facial palsya

Single-territory or multiterritory facial palsy

Unilateral vs bilateral facial palsy

Treatment Variablesb

Ocular protection

Steroid or antiviral medication

Static procedures

Facial nerve reconstruction

Regional muscle transfer

Free functional muscle transfer

Botulinum toxin

Psychological therapy

Facial rehabilitation

Speech therapy

Outcome Measurement Tools

The clinimetric and psychometric tools selected for inclusion in the standard set are shown in the Table. With the standard set being patient-centric, emphasis was placed on selecting a patient-reported or patient proxy–reported outcome measurement when an appropriate tool existed. The FACE-Q Kids patient-reported instrument16 is aimed at evaluating the functional, appearance, and psychosocial outcomes within a pediatric population with facial differences. Designed for children aged 8 years or older, the FACE-Q Kids has a mouth function scale and a face overall appearance scale deemed applicable to a pediatric facial palsy population. Given that the instrument was designed for use in patients 8 years of age or older, the working group designed yes-or-no questions that corresponded to those in the FACE-Q Kids scales to be completed by a patient proxy for those younger than 8 years.

Table. Outcome Measurement Tool for Each Domain.

| Domain Group | Tool | Data Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age <8 y | Age ≥8 y | ||

| Functional | |||

| Vision | Snellen chart (for age ≥6 y)a | Snellen chart | Clinician |

| Ocular symptoms | Y/N questions | Y/N questions | Patient or parentb |

| Oral continence | Y/N questions matched to FACE-Q Kids scale | FACE-Q Kids mouth function scale | Patient or parentb |

| Speech | Y/N questions | Y/N questions | Patient or parentb |

| Pain/discomfort | Numeric VAS (for age ≥4 y) | Numeric VAS | Patient |

| Appearance | |||

| Overall | Nil | FACE-Q Kids overall face appearance scale | Patient |

| Rest of appearance domain | eFACE (for age ≥4 y) | eFACE | Clinician |

| Psychosocial | |||

| Photographs/social media | Y/N questions | Y/N questions | Patient or parentb |

| Education/support | Y/N questions | Y/N questions | Patient or parentb |

| Rest of psychosocial domain | PROMIS Global Health (for age ≥4 y)c | PROMIS Global Health | Patient or parentb |

| PROMIS Peer Relationships (for age ≥4 y)c | PROMIS Peer Relationships | ||

| Burden of care | |||

| Complications | Clinical records | Clinical records | Clinician |

| Revision procedures | Clinical records | Clinical records | Clinician |

Abbreviations: PROMIS, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; VAS, visual analog scale; Y/N, yes/no.

In patients younger than 5 years, alternative methods for visual acuity assessment should be used according to departmental policy, but this test result does not need to be recorded in the data collected for the standard set.

In patients younger than 8 years, a parent or guardian would be asked to complete the response as a proxy.

The proxy PROMIS measurement tools would be used in patients between 4 and 8 years of age and would be completed by a parent or guardian.

A large number of clinician-reported facial nerve function measurement tools were considered by the working group,15,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 and attention focused on the broader practices of those managing patients with facial palsy.4 The digital eFACE instrument was selected for its intuitive user interface, easy availability on a mobile device, and data demonstrating its reliability and validity.15,26,27 The experience of the working group members was that a child aged 4 years or older could follow instructions to complete a clinician-reported facial nerve function measurement instrument such as the eFACE system. To date, no validated clinician-reported measurement tools exist that would allow the assessment of facial nerve function in those younger than 4 years. This admission was acceptable to the working group given that minimal interventions would be planned for patients younger than 4 years.

To our knowledge, no validated patient-reported or patient proxy–reported tools designed to measure psychosocial outcomes in a pediatric facial palsy population exist. The PROMIS Pediatric Scale v1.0 Global Health-7 and PROMIS Pediatric Short Form v2.0—Peer Relationships 8a were selected for inclusion in the standard set to evaluate the psychosocial outcome domains. Although not validated within a pediatric facial palsy population, both measures have demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in a pediatric population with and without health conditions.28,29,30,31 Furthermore, both tools have an equivalent validated patient proxy–reported outcomes measurement that allows assessment of those aged 4 to 8 years.32 The PROMIS tools selected are free to use and easy to access. The yes-or-no questions selected for inclusion can be found on the ICHOM website within the complete standard set document (http://www.ichom.org/medical-conditions/facial-palsy/).

Time Points for Outcome Measurement

The time points at which outcome measurements should be completed were selected to assess short- and long-term outcomes through a complete cycle of care. The time points were also designed to capture a change in clinical status in response to a change in treatment. A balance between comprehensive and feasible data collection was also sought.

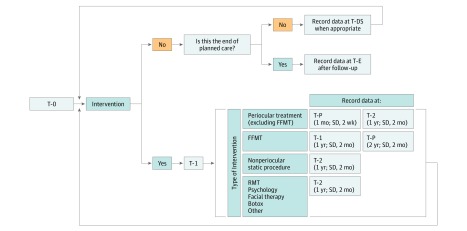

This standard set proposes that outcomes be measured at first presentation (T-0), before each new treatment (T-1), after each new treatment, at key pediatric developmental stages (T-DS), and at the end of care (T-E) (Figure 2). In recognition of the different points at which maximal treatment benefit would be expected after periocular interventions and free functional muscle transfer, a flexible posttreatment time point was created (T-P) in addition to the 1-year posttreatment time point (T-2). For periocular interventions, a relevant selection of outcome measurements should be collected 1 month after treatment. An additional outcome measurement time point at 2 years should be completed after free functional muscle transfer.

Figure 2. Suggested Time Points for Outcome Measurements Collection.

FFMT indicates free-functional muscle transfer; RMT, regional muscle transfer; T-0, patient first encounter or visit; T-1, before new treatment (any invasive or noninvasive intervention); T-2, 1 year after treatment; T-DS, developmental stage (age 5-11 years); T-E, end of care and should be completed at the end of pediatric care (age 16-18 years) or when no further treatments are planned (allow for >1 year of follow-up). T-P, variable after-treatment point to reflect the time of maximum treatment value.

To account for the different health care systems and clinical settings in which the standard set will be applied, outcome measurement time points were given a designated range in which recordings could be taken. Furthermore, the T-1 time point is valid for 6 months in recognition that multiple new interventions may be initiated within a short period, during which completion of a new T-1 time point for each intervention would incur a substantial response burden.

Case-Mix Variables and External Review

Case-mix variables were selected to allow for comparison between different clinicians and treatment categories. Twenty-eight variables were presented to the working group, and 23 (82%) were selected for inclusion. These variables were grouped into demographic, clinical, baseline condition, and treatment variables (Box). Socioeconomic status has been shown to be an important case-mix variable but can be difficult to assess.33 As a result, parental education was chosen as a surrogate marker of socioeconomic status.33 The clinical and baseline condition variables were selected to give a broad overview of the patient’s clinical status and expected prognosis. The treatment variables chosen would allow clinicians to record the interventions given and facilitate a comparison of outcomes according to treatment.

After completion of the standard set, external opinion was sought from patients or patient representatives and health care professionals; 86 independent reviews of the standard set were completed. Of the 40 participants who completed the online review survey aimed at patients and patient representatives, 34 (85%) believed that the proposed set captured the most important outcomes from the perspective of patients and their families. A total of 46 health care professionals completed the online survey between August 1, 2017, and December 31, 2017. Of those practitioners, 44 (96%) expressed confidence that the standard set represented a comprehensive overview of the essential outcomes relevant to patients with pediatric facial palsy.

Discussion

This article presents a standardized set of outcome measurements for children with facial palsy. The standard set was developed with a structured approach involving a multidisciplinary group of health care professionals, researchers, and patient representatives. It was designed to allow the recording of outcomes after the provision of surgical and nonsurgical facial palsy treatments to pediatric patients of all ages. Unilateral or bilateral, congenital or acquired, permanent or temporary, and single-territory or multiterritory facial palsy can be evaluated using this standard set. In addition, the set provides adequate risk-adjusted outcome data for making meaningful comparisons between clinicians, institutions, and treatment pathways. It may also be used to introduce value-based reimbursement strategies.

To ensure that the standard set can be used in day-to-day clinical practice, the core set of outcomes that matter most to patients was identified and included. This standard set does not aim to provide a comprehensive evaluation of all outcomes relevant to the pediatric facial palsy population. To do so would impose a substantial response burden on both the patients and health care professionals and would likely be associated with poor uptake of the standard set.

The set does not aim to be a didactic guide on the upper limit of outcomes that should be measured in a pediatric patient with facial palsy. For meaningful comparisons to be drawn, however, the timing and breadth of measurements should meet the minimum frequency and scope laid out in this standard set.

In addition to adapting the standard set according to the experiences gained during its implementation phase, information should be collated that generates insights into the psychometric validity of combining the selected series of patient-reported, patient proxy–reported, and clinician-reported outcome measures and responses to yes-or-no questions. Each of the individual patient-reported, patient proxy–reported, and clinician-reported outcome measures have been validated, but the combination of multiple clinimetric and psychometric tools in a single set requires evaluation.

A number of challenges were presented to the working group during the process of creating the standard set of outcome measurements. To our knowledge, currently, no pediatric facial palsy registries or outcome measurement sets exist. As a result, the working group had to rely on clinical expertise and data from the literature to inform its decision-making process. A further challenge arose from the lack of validated patient-reported tools specific to facial palsy in the pediatric population.34,35 Furthermore, the rapid development occurring within a pediatric population meant that the age range for which the proposed tools had been validated was often not comprehensive for the standard set’s entire population. The PROMIS psychosocial measurement tools selected offer a validated patient proxy–reported outcome measure that is directly linked to the patient-reported tools and, therefore, allow comparison across the full range of pediatric care.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the working group was led by surgeons with expertise in pediatric facial palsy. These surgeons could have biased the contents of the standard set toward metrics of most interest to a surgical cohort. Efforts to minimize this potential included the use of a Delphi process that considered each working group member’s opinion equally, as well as the regular input of patient representatives. Second, because no patient-reported tools validated for use specifically in pediatric facial palsy are available, measurement tools that are not validated for this population were chosen. Furthermore, to reduce response burden, some of the patient-reported tools were reduced, which may affect their psychometric properties. The rigorous process of considering the opinions of both health care professionals and patients or their representatives is aimed at minimizing this risk. It is hoped that future use of the standard set at multiple treatment centers will allow the recruitment of a suitable cohort of pediatric patients with facial palsy with whom the outcome measures can be validated. The adoption of this standard set in routine clinical practice is likely to present a challenge to many health care practitioners. However, the routine collection of patient-reported outcome data has been shown to improve patient-clinician communication.36 This standard set can, therefore, add value at both the individual patient and patient population levels.

The next phase of this study is the introduction of the standard set within clinical departments affiliated with members of the working group, This introduction is intended to demonstrate proof of concept and evaluate the feasibility of the standard set. After the implementation phase, adoption of the standard set by a wider pool of clinicians caring for children with facial palsy and by national regulatory bodies will be encouraged. With the ongoing collection of data, validation of the standard set and patient stratification according to different case-mix variables will become possible. Subsequently, meaningful comparison between different treatment interventions and clinicians can be performed to identify best practice.

Conclusions

This international collaborative study has created a freely available standardized set of outcome measures designed to evaluate the quality of care provided to pediatric patients with facial palsy. This set may help allow the benchmarking of clinicians, comparison of treatment pathways, and the introduction of value-based reimbursement strategies within the field of pediatric facial palsy.

Footnotes

Facial palsy severity is designated using the eFACE measurement tool composite Smile score.15

Treatment variables are recorded at the relevant T-1 time point (before new treatment).

References

- 1.Bogart KR, Briegel W, Cole J. On the consequences of living without facial expression In: Müller C, Cienki A, Fricke E, Ladewig SH, McNeill D, Tessendorf S, eds. Handbook of Body – Language – Communication: An International Handbook on Multimodality in Human Interaction. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter; 2013:1969-1982. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fattah AY, Gurusinghe AD, Gavilan J, et al. ; Sir Charles Bell Society . Facial nerve grading instruments: systematic review of the literature and suggestion for uniformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(2):569-579. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niziol R, Henry FP, Leckenby JI, Grobbelaar AO. Is there an ideal outcome scoring system for facial reanimation surgery? a review of current methods and suggestions for future publications. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68(4):447-456. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fattah AY, Gavilan J, Hadlock TA, et al. Survey of methods of facial palsy documentation in use by members of the Sir Charles Bell Society. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(10):2247-2251. doi: 10.1002/lary.24636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477-2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter ME, Kaplan RS. How to pay for health care. Harv Bus Rev. 2016;94(7-8):88-98, 100, 134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zerillo JA, Schouwenburg MG, van Bommel ACM, et al. ; Colorectal Cancer Working Group of the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) . An international collaborative standardizing a comprehensive patient-centered outcomes measurement set for colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(5):686-694. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ong WL, Schouwenburg MG, van Bommel ACM, et al. A standard set of value-based patient-centered outcomes for breast cancer: the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) initiative. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(5):677-685. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin NE, Massey L, Stowell C, et al. Defining a standard set of patient-centered outcomes for men with localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;67(3):460-467. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salinas J, Sprinkhuizen SM, Ackerson T, et al. An international standard set of patient-centered outcome measures after stroke. Stroke. 2016;47(1):180-186. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNamara RL, Spatz ES, Kelley TA, et al. Standardized outcome measurement for patients with coronary artery disease: consensus from the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM). J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(5):e001767. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.001767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clement RC, Welander A, Stowell C, et al. A proposed set of metrics for standardized outcome reporting in the management of low back pain. Acta Orthop. 2015;86(5):523-533. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2015.1036696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgans AK, van Bommel AC, Stowell C, et al. ; Advanced Prostate Cancer Working Group of the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement . Development of a standardized set of patient-centered outcomes for advanced prostate cancer: an international effort for a unified approach. Eur Urol. 2015;68(5):891-898. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prinsen CA, Vohra S, Rose MR, et al. Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative: protocol for an international Delphi study to achieve consensus on how to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a ‘core outcome set’. Trials. 2014;15:247. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banks CA, Bhama PK, Park J, Hadlock CR, Hadlock TA. Clinician-graded electronic facial paralysis assessment: the eFACE. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(2):223e-230e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wickert NM, Wong Riff KWY, Mansour M, et al. Content validity of patient-reported outcome instruments used with pediatric patients with facial differences: a systematic review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2018;55(7):989-998. doi: 10.1597/16-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(2):146-147. doi: 10.1177/019459988509300202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanagihara N. Grading of facial nerve palsy. In: Fisch U, ed. Facial Nerve Surgery, Proceedings: Third International Symposium on Facial Nerve Surgery. Birmingham, AL; Aesculapius Publishing; 1977:533–535. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vrabec JT, Backous DD, Djalilian HR, et al. ; Facial Nerve Disorders Committee . Facial nerve grading system 2.0. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(4):445-450. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murty GE, Diver JP, Kelly PJ, O’Donoghue GM, Bradley PJ. The Nottingham System: objective assessment of facial nerve function in the clinic. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;110:156-161. doi: 10.1177/019459989411000203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kayhan FT, Zurakowski D, Rauch SD. Toronto facial grading system: interobserver reliability. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(2):212-215. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70241-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu WL, Ross B, Nedzelski J. Reliability of the Sunnybrook facial grading system by novice users. J Otolaryngol. 2001;30(4):208-211. doi: 10.2310/7070.2001.20148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coulson SE, Croxson GR, Adams RD, O’Dwyer NJ. Reliability of the “Sydney,” “Sunnybrook,” and “House Brackmann” facial grading systems to assess voluntary movement and synkinesis after facial nerve paralysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132(4):543-549. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neely JG, Cherian NG, Dickerson CB, Nedzelski JM. Sunnybrook facial grading system: reliability and criteria for grading. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(5):1038-1045. doi: 10.1002/lary.20868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burres S, Fisch U. The comparison of facial grading systems. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;112(7):755-758. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1986.03780070067015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banks CA, Jowett N, Hadlock TA. Test-retest reliability and agreement between in-person and video assessment of facial mimetic function using the eFACE facial grading system. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19(3):206-211. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2016.1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banks CA, Jowett N, Azizzadeh B, et al. Worldwide testing of the eFACE facial nerve clinician-graded scale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(2):491e-498e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forrest CB, Bevans KB, Pratiwadi R, et al. Development of the PROMIS® pediatric global health (PGH-7) measure. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(4):1221-1231. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0581-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forrest CB, Tucker CA, Ravens-Sieberer U, et al. Concurrent validity of the PROMIS pediatric global health measure. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(3):739-751. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1111-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dewalt DA, Thissen D, Stucky BD, et al. PROMIS pediatric peer relationships scale: development of a peer relationships item bank as part of social health measurement. Health Psychol. 2013;32(10):1093-1103. doi: 10.1037/a0032670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kashikar-Zuck S, Carle A, Barnett K, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of patient-reported outcomes measurement information systems measures in pediatric chronic pain. Pain. 2016;157(2):339-347. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varni JW, Thissen D, Stucky BD, et al. Item-level informant discrepancies between children and their parents on the PROMIS pediatric scales. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(8):1921-1937. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0914-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shavers VL. Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(9):1013-1023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kahn JB, Gliklich RE, Boyev KP, Stewart MG, Metson RB, McKenna MJ. Validation of a patient-graded instrument for facial nerve paralysis: the FaCE scale. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(3):387-398. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200103000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.VanSwearingen JM, Brach JS. The Facial Disability Index: reliability and validity of a disability assessment instrument for disorders of the facial neuromuscular system. Phys Ther. 1996;76(12):1288-1298. doi: 10.1093/ptj/76.12.1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]