Abstract

Background

The tobacco industry has used the alleged negative impacts on economic livelihoods for tobacco farmers as a narrative to oppose tobacco control measures in low-and middle-income countries. However, there is still a paucity of rigorous empirical evidence to counter this argument. Accordingly, we assess how much money households earn from selling tobacco, and the costs they incur to produce the crop, including labour inputs. We also evaluate farmers’ decision to operate under contract directly with tobacco companies or as independent farmers.

Methods

A stratified random sampling method of carrying out a systematic nationally representative household-level economic survey of 585 households was designed and implemented across the three main tobacco growing regions in Kenya. The survey was augmented with focus group discussions to refine and enrich our interpretation of the findings.

Results

Tobacco farmers generally experience small margins per acre, with contract farmers operating at a loss. Even when family labour is excluded from the calculation, income levels are not high. Generally, tobacco farmers enter into contracts with tobacco companies because they have a “guaranteed” buyer for their tobacco leaf and receive the necessary agricultural inputs (fertilizer, seeds, herbicides, etc.) without paying cash up-front.

Conclusions

We conclude tobacco farming households contract with tobacco companies to meet perceived economic benefits. The narrative that tobacco farming is a lucrative economic undertaking for smallholder farmers in Kenya is inaccurate in the context of Kenya.

Introduction

The emergence, promotion and expansion of tobacco leaf cultivation in many low-and middle-income countries (LMIC) has been supported by the tobacco industry narrative that tobacco production is lucrative for the economies, including benefits to government and tobacco farmers1–9. This narrative is deployed against tobacco control measures, with arguments that such measures result in the loss of export earnings5,6,8, jobs for cigarette manufacturing workers7, tax earnings to governments as a result of reduction of tobacco consumption5,7 and, more pertinent to this research, that control measures can negatively affect the economic livelihoods of farmers dependent on tobacco as a cash crop.3,6 These arguments resonate with some governments like Malawi who have even challenged the novel tobacco control in international economic fora10 , which has been and have created a major barrier to tobacco control in many countries where tobacco is grown. Although there is a small emerging literature suggesting that smallholder tobacco farmers do not make adequate returns from tobacco farming8,9,11,12 and that tobacco’s earnings’ contribution to GDP is small13, there is still a paucity of empirical evidence across countries and time to systematically counter the prosperous livelihood narrative. Country-specific empirical studies are important because of policy makers’ increasing demand for country-specific evidence in order to justify enhancing tobacco control to their constituencies.

This research is a rigorous household-level economic assessment of tobacco farming in Kenya using a nationally representative sample. It builds on earlier work11,12,19 that assesses profits from tobacco farming and other crops in South Nyanza, Kenya. Unlike the previous research that covered only one region and was not based on an extensive household survey, this research utilizes original data from households in the three regions and over four counties where tobacco is most widely grown, making results nationally representative. The study also differs because it further elaborates the value chain that makes tobacco a more attractive commodity in regions where it is grown.

This research contributes to existing empirical evidence in three ways. First, it uses analysis of nationally representative data on the economics of tobacco farming to assist policy makers in developing a national policy on tobacco farming in Kenya. Second, and unusual in such studies, it accounts for production costs more comprehensively by systematically incorporating a monetized value of family labour. Finally, it builds upon other studies in low-and middle-income countries8 that examine both contract and independent farmers (see below) to help determine if there are differences in economic livelihoods between these two sets of smallholder tobacco farmers. It also seeks to explain why some farmers choose to engage in formal contracts with tobacco firms.

Tobacco Farming in Kenya

The number of tobacco farmers in Kenya has increased over time from 35,000 in 2007 to 55,000 in 201511–19 with most of the farming taking place in Western region where over 24,000 are involved in tobacco farming12. In recent years, British American Tobacco (BAT), Mastermind Kenya and Alliance One have been the major firms in tobacco leaf purchase from farmers and manufacturing of the same to cigarettes. However, Alliance One exited the market in 2016 because of divestment from flue-cured Virginia tobacco, the dominant tobacco leaf grown in Kenya. Smallholder tobacco farmers generally prefer to engage in tobacco production as contract farmers where they receive inputs and agricultural extension services from the tobacco companies, with input costs deducted from the earnings upon sale of the leaf16,17. Independent farmers source and pay for inputs and do not receive extension services from the tobacco companies. After harvest, independent farmers have the freedom to sell the tobacco leaf to any tobacco firm unlike contract farmers who can only sell to the firm that contracts them. The tobacco industry’s consistent narrative in Kenya as in other countries is that contract farming is a better economic choice for farmers8, but there has been little empirical research comparing contract and independent farmers’ economic livelihoods, and no rigorous examination of why some farmers choose to enter into contract while others remain independent.

Evidence from Kenya suggests that tobacco production is associated with serious social and environmental impacts. These include, among others, deforestation, poverty, negative ecological balance and food insecurity, with many farmers using most of their land in tobacco farming at the expense of food crops15,16,17,18. Tobacco was also found to be less profitable to farming households than other crops such as passion fruit, soybeans, water melon, pepper and pineapple, when cost and return analysis of different crops grown in the tobacco growing region of Kuria are compared19. Studies have also demonstrated that the socio-economic status of tobacco-growing households is relatively lower when compared to non-tobacco farming households in the same areas, with a higher prevalence of child labour, polygamy and large family sizes15. Despite having a well-developed value chain when compared to alternative crops in the same region, tobacco farming households have less access to financial resources and lower incomes and depend more on remittances from other family members employed in formal sectors locally and abroad than do non-tobacco farming households11,12,15. Accordingly, this research seeks to determine the impacts of tobacco farming on farmers’ economic welfare.

4.3. Research Design and Methods

To examine the economic conditions of tobacco growing in Kenya, we utilized mixed methods. First, we collected primary survey data. The survey was developed by a multi-disciplinary, international research team and implemented in January 2015 in three regions spread over four Kenyan counties where tobacco is most widely grown. Data was collected in Migori County in Nyanza region, in Bungoma and Busia Counties in Western region, and Meru Country in Eastern region. The areas were purposefully selected based on production data from the Ministry of Agriculture in Kenya. The survey used a multi-stage and stratified random sampling procedure where 200 tobacco farming households were selected randomly from each of the three tobacco-growing zones. The first step was to identify the main tobacco growing areas from production records from the Ministry of Agriculture. Afterwards, the area with the highest concentration of tobacco farming households was chosen and mapped, with enumerators beginning the household survey from a household that was randomly selected in the area, moving along a predetermined route, from one household to another. To determine the sample size, we first defined the population size N of tobacco farming households in Kenya to be 55,00011. We used a simple random sampling process adopting the conservative standard deviation to be 0.5, confidence level as 95% (Z=1.96), and allowed the margin of error e to be 4.5%.

| (1) |

Based on equation (1), the study established that the unadjusted sample size needed to be 494. To adjust for population size, equation (2) was then considered.

| (2) |

As the population size is large, the adjusted sample size remained at 494. Based on previous agricultural surveys in the country, the expected response rate was between 85% and 90%. Therefore, we sought to reach out to 600 tobacco farming households to reach our target sample size. In the end, we obtained a sample size of 585 (a response rate of ~97.5%). We implemented the study evenly across the three regions based on government statistics that suggest there are no large regional differences in tobacco growing in Kenya. The survey interviews were implemented by one team across all the counties over a period of one month. The team of 10 enumerators were trained in data collection including interviewing approach and ethics in data collection to standardize the data collection. The first author supervised the team during data collection to ensure correct implementation of protocols were observed. The data from the completed questionnaires was inputted into Stata.

Second, after the survey, we implemented focus group discussions (FGDs) with survey participants in each of the tobacco growing regions to contextualize and enhance our interpretation of the findings. Overall, we conducted a total of 3 FGDs across all regions (Migori, Busia and Meru), with each region having one FGD. The FGDs took place in a village center or school in the area with a high concentration of tobacco farmers with the farmers randomly selected from the area (n=10–15 farmers per FGD). An FGD tool was developed with the discussion transcribed by the research team.

For the analysis, we estimated two related but distinct types of profit. First, the perceived profit, where we estimated gross margins from tobacco growing enterprises that enumerated both the money earned from tobacco-related activity and all costs associated with growing tobacco, including all inputs, fees, penalties and, importantly, hired labour. Secondly, we conducted a cost-profit analysis that incorporates the monetized value of family labour based on the average earnings of agricultural day labourers to compute what we defined as the actual profits that the household earns from engaging in tobacco production.

While profits and lack of an economically viable livelihood option is the general motivation in engaging in tobacco production1,8, smallholder tobacco farmers have another choice as to whether they should grow tobacco as contract farmers or independent farmers. This choice determines the level of interaction they will have with tobacco firms including access to inputs and market, and therefore possibly the level of profit earned. To examine the variables associated with a farmer’s decision to engage in contract farming, we utilized a logistic regression with the dichotomous ‘contract farmer’ as the dependent variable. We included the following independent variables: age, experience, educational level, gender, and marital status of the household head, land size and legal entitlement of the land, amount of tobacco harvested, revenue from tobacco sold, and access to credit.

4.5. RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

The sample of 585 farmers comprised of independent farmers (n=107) and contracted farmers (n=478) from 3 major tobacco growing regions in Kenya. T-tests were conducted to establish the differences in the means of the two categories of the farmers with the significance levels highlighted. Results suggest that independent and contract farmers are similar in many socio-economic aspects. However, the results show that contract farmers are more experienced in tobacco farming with the average years of growing tobacco being 10 years compared to 7 years for independent farmers (p<0.05). Contract farmers also have larger land sizes: 3.67 acres, of which an average of 2.8 acres is cultivated land and 1.87 acres is devoted to tobacco. This compared to independent farmers who have an average of 3.03 acres, of which 2.4 acres is cultivated and 1.56 acres devoted to tobacco (p<0.05).

Profit Analysis

Table 2 presents the costs, prices and production of smallholder tobacco farmers. The average prices offered to the two groups varied, with contract farmers offered a higher price for tobacco leaf per kilogram, although the difference is not statistically significant. Farmers’ non-labour costs are also presented in Table 2. Note that for the input costs we include the principal variable costs such as tools, fertilizer, herbicide, pesticide and seeds, but not the fixed costs such as land rental (where applicable, though importantly, land rental is not a large part of most farmers’ production). Results indicate that contract farmers have 25.11 percent higher per-acre input costs than independent farmers. This difference was significant at p<0.05 for per acre input costs although not statistically significant for per/Kg costs. It is important to note that many of the farmers involved in the FGDs recognized the exploitative dependency the contractual relationship created for them: “Tobacco companies are in business. They make money from selling inputs to contract farmers. If you want to do business with them, even when you have the ability to purchase inputs, you have to be a contract farmer. Otherwise they won’t do business with you.”

Table 2:

Logistic Regression of Decision to Contract Farm tobacco leaf

| Variable | Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Education | 0.056* (0.033) | −0.009 to 0.122 |

| Gender | 0.266 (0.240) | −0.204 to 0.737 |

| Age | −0.035 *** (0.012) | −0.060 to −0.011 |

| Marital Status | 0.090 (0.102) | −0.109 to 0.289 |

| Household Size | 0.045 (0.038) | −0.030 to 0.120 |

| Land Size | 0.068 (0.063) | −0.056 to 0.192 |

| Legal Entitlement | 0.288 *** (0.088) | 0.116 to 0.460 |

| Need for Credit | 0.057 (0.208) | −0.352 to 0.465 |

| Tobacco Harvested | 0.000 * (5.63E-05) | −1.1E-04 to 1.07E-04 |

| Tobacco Revenue | 0.000* (8.51E-07) | −3.15E-06 to 1.86E-07 |

| Years of Growing Tobacco | 0.037 ***(0.015) | 0.007 to 0.067 |

| Constant | −0.689 (0.587) | −1.840 to 0.462 |

p<0.1,

p<0.05,

p<0.01

Results also indicate that contract farmers incur higher levies (local tax) per acre (p<0.05 for both per acre and per kg measures). Finally, transport costs are more for contract farmers in per acre measures but less per kg, although neither difference is statistically significant. Table 2 also presents the average labour hours – combined total of all household members – needed to produce an acre and a kilogram of tobacco leaf. Note that the kilogram measure used in this table is the amount actually sold in the 2013/2014 season (not necessarily the amount produced, which is typically more because some tobacco is not sold for a variety of reasons, which can include poor quality or a lack of demand). Per acre labour hours from household members are lower for contract farmers (253) than individual farmers (339), although this difference is not statistically significant.

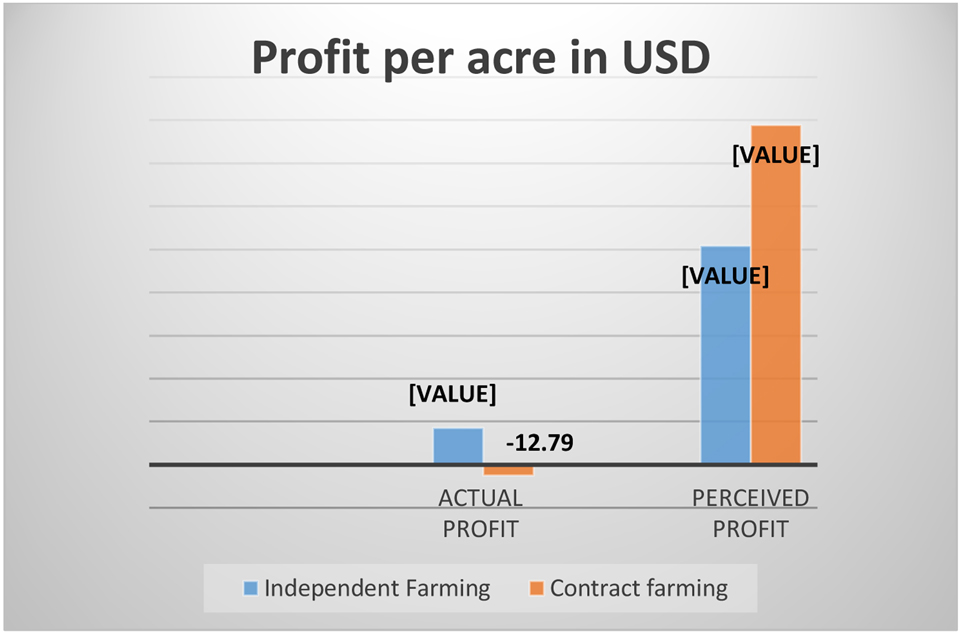

We calculated a profits-per-acre measure that includes personal and family labour so that we could compare the actual profit to the perceived profit of the tobacco farmers who, as our focus group research affirmed, were not typically incorporating this significant set of costs in their profit estimations. Monetization estimate for family labour was computed by first summing all of the labour hours dedicated to tobacco by all household members. We then multiplied these hours by the daily minimum wage in US$ (using Kenyan government and EIU exchange rates) based on 2013/2014 monthly agricultural minimum wage measures from the Ministry of Labour Office. While the two columns on the far right of Figure 1 suggest a perceived profit for contract farmers of US$254/acre and US$394/acre for independent farmers, the actual profits drop precipitously once labour is included: a US$13/acre net loss for contract farmers and a drop in profit for independent farmers to US$43.

Figure 1:

Profit per acre including family labour in US$.

Independent farmers versus Contract farmers – Decision to become a Contract farmer

Table 3 presents the results of a logistic regression of the decision to become a contract farmer. One of the most pronounced relationships between variables is that of experience in growing tobacco: the coefficient is positive (0.037) and statistically significant, suggesting that as a tobacco farmer increases growing experience by one year, the likelihood of him or her deciding to be a contract farmer increases by 3.7%. Experience growing tobacco seemed to be tied to the pursuit of a “guaranteed” buyer. Others confirmed the attraction of having a predictable and stable buyer:

“We have fixed expenses like school fees for the children. Having certainty in income, however low is better than no income at all.”

“Tobacco is the only crop in the area where farmers are assured of some income. Other crops in the area have no money or cannot sustain a family consistently. To draw income from tobacco you need to be a contract farmer.”

Legal entitlement of the farmer to the farm is also an important variable and its coefficient is positive (0.288) and statistically significant; land ownership increases the likelihood of a farmer being a contract farmer by 28.8%. The coefficient for education level is also positive and significant, a one increment change in education increases the likelihood of becoming a contract farmer by 5.6%. Finally, the coefficient for age is negative and significant; as age increases by one year, the likelihood of a farmer being a contract farmer decreases by 3.5%.

Discussion

The results provide important insights into the economic livelihoods of tobacco farmers in Kenya, including differences in contract versus independent tobacco farming. Tobacco farmers are predominantly male, are married, have primary level education and have farming as their primary source of income. Overall, in Kenya, from the survey, the average annual income earned from tobacco farming accounted for about 65% of the total household income earned by both sets of farmers.

Results suggest that farmers in contractual relationships with the tobacco companies generate limited actual profits, particularly when compared to their perceived profits, which implies little monetary reward for choosing to contract. The contract farmers also indicated significant dissatisfaction with the price that they received for the leaf that they sold, with less than a third reporting that they were receiving a fair price (p<0.05). This could be because the assignment of leaf grade and price is at the discretion of an official from the tobacco companies at the leaf buying centers, with the farmers or farmer representatives to the tobacco companies having no part in the decision. Evidence from Malawi has shown that prices are persistently and systematically lowered, with very little recourse for tobacco farmers23. Where a particular farmer voices disagreement with the grade and price allocated, the tobacco officials simply reject their produce, creating a situation where the farmer could either fail to sell his crop altogether or have his earnings delayed. Farmers in the FGDs indicated that contract farmers are given inputs at higher prices than they would ordinarily buy from shops. An example given was fertilizer where contract price was USD$ 40 compared to USD$ 20 in retail shops. This is consistent with previous research finding that tobacco companies inflate prices of inputs21,22.

Generally, both contract and independent farmers earn low gross margins from tobacco farming. Once accounting for family labour, independent farmers have slightly higher earnings than contract farmers. Three factors help explain the difference in the adjusted profit margins between the two categories of farmers: a) non-labour inputs, b) family labour, and c) tobacco leaf prices at the collection areas. The average tobacco price per acre for contract farmers is 12.8% higher than that of independent farmers. This suggests that tobacco companies might be encouraging all tobacco farmers to become contract farmers by purchasing their crop at higher prices, consistent with a finding from a study of tobacco farming in Malawi8. The logic of contract farming is also tied to efficiency and quality gains, where companies introduce structural supports – for example, by helping farmers with effective chemical applications (e.g. fertilizer, pesticide, herbicide, etc.) – to ensure that farmers are growing a higher quality product24. At the same time, tobacco leaf companies appear to be exploiting the farmers through downgrading the quality of tobacco leaf while also by increasing the profit margins on their sale of inputs to contracted farmers.

Results suggest that farmers who have more experience in growing tobacco and who have the legal and permanent title to their farmers are more likely to be contract farmers, possibly explained by a greater awareness of their likelihood of selling their crop compared to that of independent farmers.

Opportunity costs also play a part in the contracting decision of farmers. Notably, older farmers are less likely to be contract farmers while those with higher education levels are likely to be contract farmers. Older farmers generally not only have larger land sizes but also more experience in growing other crops which helps in income diversification, affording them financial security outside tobacco growing. This can be seen in Meru County, the most fertile tobacco growing area, where farmers participate in other economic activities that generate sizeable amounts of income when compared to tobacco, and where they reported relatively fewer complaints about the tobacco companies during the FGDs. With more education, farmers are generally more likely to be rational in making economic decision on farming tobacco as opposed to other crops. This is because tobacco growing areas are characterized by unstable markets for other alternative crops while farming tobacco ensures a guaranteed buyer.

Family labour forms a critical part of tobacco growing. Tobacco is a labour intensive crop that would generally be expensive to engage in if one depended purely on hired labour. Many household members actively contribute time towards tobacco growing activities, an aspect generally not considered when tobacco farmers or researchers compute the costs of tobacco production. By monetizing family labour as we have done in this study, we imply two things. First, that tobacco only becomes minimally profitable through use of free family labour versus paid labour, and secondly, that the profitability of tobacco firms is enhanced through unpaid exploitation of poor rural tobacco farmers. Our findings in this regard are particularly strong because our monetizing of this household labour is conservative and likely underestimates its value.

These findings illustrate an important labour dynamic. Tobacco companies are exploiting what amounts to “free” (to the companies) or at least unaccounted for – by the farmers – labor in small holder tobacco growing. Because farmers do not incorporate household labor into their cost calculations in any way, the perceived profits are much higher than if farmers were to incorporate even a fraction of such costs into their cost calculations. However, at the same time the exclusion of household labor costs in rural low and medium income countries is not unusual. This is particularly true when other sources of employment and other income opportunities are scarce. This is an important point for tobacco control proponents who are targeting the control of tobacco supply, whereby the local economy, which is of course tied to the global economy, must be considered a key factor in policy interventions aimed at creating opportunities for other sources of income. Research has found that local opportunities are key determinant of farmer’s decisions to pursue non-farm employment 25.

Conclusion

his study demonstrates that tobacco farming is not a particularly lucrative enterprise for most smallholder tobacco farmers in Kenya, either independent or contract. Most farmers are making only a tiny profit at best. Moreover, once farmers incorporate even a conservative estimate of the value of their labour, their actual profits diminish, suggesting that tobacco farming is even less lucrative than they are conceptualizing, leading to impoverishment of the farmers. This is exacerbated when we monetize the family labour costs and incorporate it in the computation of actual profits, with the end result suggesting earnings from tobacco faming is low and will not help farmers move out of poverty. Because family labour is not consciously considered as a cost of production and goes unpaid, it also indirectly contributes to high earnings in the tobacco firms. It therefore makes considerable economic sense for the government to aggressively seek viable alternative livelihoods in line with article 17 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. This includes improving supply and value chains for other agricultural products that the farmers grow locally, increasing farmers’ access to credit and improving agrarian and farm-management education for these households. Finally, while it is not possible to immediately provide a similar production model as one for the tobacco industry, farmers can organize themselves into formal groups and tap into existing agricultural development programs and demand services that would facilitate them to generate income and diversify their production systems.

Table 1:

Average Production, Costs, Price and Income

| Independent Farmers | Contract Farmers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kgs | Kgs | acre | ||

| Average Leaf Production | 822.72 | 1320.7 | ||

| Average Tobacco Sales | 765.06 | 1075.97 | ||

| Average Price (US$/kg) | 1.32 | 1.49 | ||

| US$/kg | US$/acre | US$/kg | US$/acre | |

| Average Income | 1.68 | 807.43 | 1.37 | 749.52 |

| Non-Labour Costs | US$/kg | US$/acre | US$/kg | US$/acre |

| Input costs | 0.83 | 257.31 | 0.82 | 321.93 |

| Levy | 0.17 | 7.26 | 0.96 | 39.02 |

| Transport | 0.24 | 10.24 | 0.03 | 13.33 |

| Interest | 1.53 | |||

| Total Non-Labour Costs | 1.24 | 274.81 | 1.81 | 375.81 |

| Labour Hours | 637.89 | 2.63 | 476.21 | 2.19 |

| Labour Costs | US$/kg | US$/acre | US$/kg | US$/acre |

| Hired Labour | 0.25 | 109.95 | 0.29 | 117.08 |

| Household Members | 0.56 | 338.72 | 0.35 | 252.87 |

| Total Labour Costs | 0.81 | 448.67 | 0.64 | 369.95 |

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Fogarty International Center and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01DA035158.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: IRB of Morehouse School of Medicine.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCE

- 1.Warner KE, Fulton GA. Importance of tobacco to a country’s economy: an appraisal of the tobacco industry’s economic argument. Tob Control 1995; 4:180–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee S, Ling PM, Glantz SA. The vector of the tobacco epidemic: tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes Control 2012; 23 (Suppl 1):117–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilmore AB, Fooks G, Drope J, et al. Exposing and addressing tobacco industry conduct in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2015; 385:1029–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenya Africa Tobacco Situation Analysis, Drope J. Kenya. In: Drope J, ed. Tobacco control in Africa: people, politics and policies. London, UK: Anthem Press and IDRC, 2011:149–166. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckhardt J, Holden C, Callard CD. Tobacco control and the World Trade Organization: mapping member states’ positions after the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Tob Control Published Online First: 19 Nov 2015. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otañez M, Graen L. Malawi. In: Leppan W, Lecours N, Buckles D, ed. Tobacco control and tobacco farming: separating myth from reality. Ottawa, ON: Anthem Press (IDRC), 2014: 61–95. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chavez JJ, Drope J, Lencucha R, & McGrady B. (2014) The political economy of tobacco control in the Philippines: trade, foreign direct investment and taxation. Quezon City: Action for Economic Reform, American Cancer Society. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makoka D, Drope J, Appau A, Labonte R, Li Q, Goma F, Zulu R, Magati P, & Lencucha R (2017). Costs, revenues and profits: an economic analysis of smallholder tobacco farmer livelihoods in Malawi. Tobacco Control. 26(6), 634–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naher F, Efroymson D. Tobacco cultivation and poverty in Bangladesh: issues and potential future directions. Dhaka: World Health Organization, 2007. (Ad Hoc Study Group on Alternative Crops). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magati PO, Kibwage JK, Omondi SG, Ruigu G, Omwansa W A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Substituting Bamboo for Tobacco: A Case Study of Smallholder Tobacco Farmers in South Nyanza, Kenya. Science Journal of Business Management 2012; 2(1): 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kibwage J, Netondo G, & Magati P Substituting Bamboo for Tobacco in South Nyanza Region, Kenya In: Leppan W, Lecours N, Buckles D, ed. Tobacco control and tobacco farming: separating myth from reality. Ottawa, ON: Anthem Press (IDRC), 2014: 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel P, Collin J & Gilmore AB “The law was actually drafted by us but the Government is to be congratulated on its wise actions”: British American Tobacco and public policy in Kenya. Tobacco Control 2007; 16(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mureithi LP “Tobacco-related issues in Kenya,” in Economic, Social and Health Issues in Tobacco Control - Report of a WHO international meeting at Kobe, Japan, 3-4 December 2003. Kobe, Japan: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kibwage JK, Odondo AJ & Momanyi GM Assessment of livelihood assets and strategies among tobacco and non-tobacco growing households in South Nyanza, Kenya. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2008; 4(4): 294–304 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kweyuh P Does tobacco growing pay? The case of Kenya In: Abedian I, van der Merwe R, Wilkins N, Jha P, eds. The economics of tobacco control: towards an optimal policy mix. Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town, 1998:245–50. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chacha BK From Pastoralists to Tobacco Peasants: The British American Tobacco (B.A.T) and Socio-ecological Change in Kuria District, Kenya, 1969–1999. Njoro: Egerton University 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kibwage JK, Momanyi GM & Odondo AJ Occupational health and safety issues among small holder tobacco farmers in South Nyanza region, Kenya. African Newsletter on Occupational Health and Safety 2007; 17(2): ISSN 0788–4877. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochola S , Kosura W Case Study on Tobacco Cultivation and Possible Alternative Crops-Kenya, Study conducted as a technical document for the first meeting of the Ad Hoc Study Group on Alternative crops established by the Conference of the Parties to the WHO Frame work Convention on Tobacco Control (February,2007). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wainaina PW, Okello JJ & Nzuma J Impact of Contract Farming on Smallholder Poultry Farmers’ Income in Kenya Proceedings of the International Association of Agricultural Economists (IAAE) Triennial Conference. Foz Do Iguacu, Brazil, 18–24 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Working Group, Robert Mayo. Current world fertilizer trends and outlook to 2018. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaaban Jad. In: Leppan W, Lecours N, Buckles D, ed. Tobacco control and tobacco farming: separating myth from reality. Ottawa, ON: Anthem Press (IDRC), 2014: 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otanez MG, Mamudu H, & Glantz SA Global leaf companies control the tobacco market in Malawi. Tobacco Control 2007, 16(4), 261–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrett CB, Bachke ME, Bellemare MF, Michelson HC, Narayanan S, & Walker TF Smallholder participation in contract farming: comparative evidence from five countries. World Development 2012; 40(4), 715–730. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alasia A, Weersink A, Bollman RD, & Cranfield J Off-farm labour decision of Canadian farm operators: Urbanization effects and rural labour market linkages. Journal of rural studies 2009; 25(1), 12–24. [Google Scholar]