Abstract

Introduction

With advances in treatments among patients with lung cancer, it is increasingly important to understand patients’ values and preferences to facilitate shared decision making.

Methods

Prospective, multicenter study of patients with treated stage I lung cancer at time of study participation which occurred 4-6 months after treatment. Value clarification and discrete choice methods were used to elicit participants’ values and treatment preferences regarding stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) and surgical resection using only treatment attributes.

Results

Among 114 participants, mean age was 70 years (Standard Deviation= 7.9), 65% were male, 68 (60%) received SBRT and 46 (40%) received surgery. More participants valued independence and quality of life (QOL) as “most important” compared to survival or cancer recurrence. Most participants (83%) were willing to accept lung cancer treatment with a 2% chance of periprocedural death for only one additional year of life. Participants also valued independence more than additional years of life as most (86%) were unwilling to accept either permanent placement in a nursing home or being limited to a bed/chair for four additional years of life. Surprisingly, treatment discordance was common as 49% of participants preferred the alternative lung cancer treatment than what they received.

Conclusions

Among participants with early stage lung cancer, maintaining independence and QOL were more highly valued than survival or cancer recurrence. Participants were willing to accept high periprocedural mortality, but not severe deficits affecting QOL when considering treatment. Treatment discordance was common among participants who received SBRT or surgery. Understanding patients’ values and preferences regarding treatment decisions is essential to foster shared decision making and ensure treatment plans are consistent with patients’ goals. Clinicians need more resources to engage in high quality communication regarding lung cancer treatment.

Keywords: lung cancer, shared decision making, decision making, patient values and preferences, quality of life, treatment concordance, surgical resection, radiation therapy

1.0. Introduction

Among those with early stage lung cancer, the primary focus of treatment is to improve survival while maintaining quality of life (QOL). However, these aims are not always congruent. Among long-term cancer survivors, patients with lung cancer scored lowest in health care utility (i.e., worst QOL) with reduced physical ability and depressive symptoms,1 factors known to reduce survival.2,3 Among patients with lung cancer five years after treatment, significant symptom burden persisted and more than one-third reported a significant decline in QOL following treatment.4 QOL was also substantially reduced two years after surgery among those with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).5 Preservation of QOL is important when considering treatment options, especially among older patients, whose underlying comorbidities and disabilities can be exacerbated as they often experience a significant decline in QOL or independence following treatment.6 These considerations are particularly salient among those diagnosed via lung cancer screening, as screening guidelines include octogenarians.7

Shared decision making (SDM) is an approach where clinicians and patients engage in a discussion that incorporates information exchange and patients’ values/preferences are elicited to reach a medical decision. Lung cancer screening guidelines are unique, compared to other Medicare cancer screening guidelines, as SDM is a requirement for payment.8 Patient participation in medical decision making is more widely advocated in the current medical climate than ever before.9–12 SDM is particularly important in decisions regarding cancer treatments as they often involve significant trade-offs between potential benefits (e.g., survival) and harms (e.g., reduced QOL) where the “best” choice is sensitive to patients’ values and priorities. Additionally, patients with cancer desire active roles in treatment decision making.13‘15

Surgery is the current “standard of care” among those with early stage NSCLC16 as it is associated with improved 5-year survival when retrospectively compared to stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).17 However, in practice, a sizable percentage of patients are non-operable due to high perioperative mortality risk related to advanced age and/or comorbidities.18–22 Determining an acceptable surgical mortality cut-off is arbitrary and when surveyed, lung cancer specialists disagree about the evidence regarding treatment of early stage NSCLC.23 Even among operative candidates, thoracotomy is associated with complications in up to 31% of patients,24 including perioperative mortality (i.e., death within 90 days of surgery) 2-3 times higher than SBRT.17,25 Surgical risks may be reduced with less invasive approaches such as video-assisted thorascopic surgery (VATS).24,26 Three separate trials of surgery versus SBRT closed early due to low recruitment, but pooled analyses of two trials suggested improved recurrence-free and overall survival at three years with SBRT.27 As a result of insufficient clinical evidence and potential risks, clinical equipoise between SBRT and surgery exists for many patients diagnosed with early stage disease.

When equipoise exists, choosing the best treatment should depend more on the values and preferences of patients.28 Therefore, it is increasingly important to elicit and understand patients’ values and treatment preferences in order to engage in high-quality SDM regarding lung cancer treatment. In the present study, we sought to determine the values and preferences regarding SBRT and surgical resection among patients with early stage lung cancer. Specifically, we used value clarification, standard gamble and discrete choice experiment methodologies to examine decision-making. We hypothesized patients would value QOL and survival highest, and there would be a high degree of self-reported treatment discordance related to decisional conflict, the quality of clinician communication and health-related QOL.

2.0. Methods

This was a prospective, observational, multicenter study of patients with pathologically or clinically confirmed stage I NSCLC treated at health centers in the U.S. Pacific Northwest representing academic and community-based medical centers: Veterans Affairs (VA) Portland Health Care System, Oregon Health & Science University, Legacy Health; Providence Health & Services, Peace Health, Tuality Healthcare and Kaiser Permanente. All centers provide comprehensive, multidisciplinary lung cancer treatment for patients with early stage disease including SBRT and surgical resection. We conducted this study at participants’ 4-6-month follow-up survey following receipt of lung cancer treatment (either SBRT or surgery), as part of a larger longitudinal study.29

Participants were asked a series of questions, by trained research assistants using a standardized guide, pertaining to their values and decision making regarding cancer treatment. Participants were eligible at baseline, before they received cancer treatment, if they were considered for curative treatment of clinical stage INSCLC, with a plan for SBRT or surgical resection. The treatment received was based on the treating clinician(s)’s recommendations; in general, participants who were considered inappropriate operative candidates for surgical resection were referred for SBRT. Participants who scored less than 17/30 on the St. Louis University Mental State Examination (SLUMS),30 indicating severe cognitive impairment, were excluded. Survey Flesch-Kincaid reading level was grade 7.5 (grade 8 ensures content can be read by 80% of Americans). For this study, we limited the sample to participants who received SBRT or surgical resection. Other exclusions were non-English speakers, a lung cancer history within 5 years, or history of severe, uncontrolled schizophrenia, dementia, or severe hearing impairment. All surveys were conducted via telephone using a standardized form to obtain sociodemographic characteristics, self-reported comorbidities, and tobacco use. Trained chart reviewers used a chart abstraction report form to collect cancer diagnosis and treatment information from participants’ electronic health records (EHR). Complications were considered treatment-related and acute if they occurred around the time of treatment in consultation with participants’ clinicians. This study received IRB approval (#10340).

2.1. Values

Participants were asked a series of closed-ended questions regarding values clarification, which is the process of determining what matters most to an individual relevant to a given health decision.32 Participants were asked to rate each statement using an elicitation procedure called prioritization.32 Values presented were informed by those suggested for measuring value in cancer care33 along with those reported among lung cancer patients.34–36

| Values Questions |

| 1. When considering lung cancer treatment what is important to you? |

| (Please label each of the following M= most important, L= least important, N= not important) |

| a. ______staying away from regular visits to doctors and hospitals |

| b. ______costs of treatment |

| c. ______physical side effects of treatment |

| d. ______emotional side effects of treatment |

| e. ______staying away from intensive medical care (ICU care) |

| f. ______being able to take care of myself |

| g. ______chance the lung cancer returns |

| h. ______being a burden to my spouse, family or friends |

| i. ______being able to remain in my own home |

| j. ______additional years of life |

In the next set of questions, we examined the extent to which participants’ valued length of life versus the potential for periprocedural death. Participants were presented with a hypothetical scenario of an unnamed lung cancer treatment (with similar characteristics as surgical resection) with a chance of periprocedural death, and if they were willing to accept this percent chance for an additional year of life. Participants were told “Without the treatment, you won’t be alive after 18 months and the last six months you would have a low QOL” which is consistent with prognosis in untreated patients.36 The percent chance of periprocedural death: two, five, ten or 20%, for additional years of life: one, two, three or four years, were adjusted based on participants’ responses. See example below. Yes/no responses were recorded for four scenarios.

| 1st Question: Would you accept a 2 out of 100 chances of immediate death for 1 additional year of life? |

Response= YES

Response= YES

|

| 2nd Question: Would you accept a 5 out of 100 chances of immediate death for 1 additional year of life? |

Response= NO

Response= NO

|

| 3rd Question: Would you accept a 5 out of 100 chances of immediate death for 2 additional years of life? |

The next series of questions examined the extent to which participants valued length of life versus QOL. Questions concerned possible outcomes after a hypothetical lung cancer treatment that had similar characteristics as surgical resection using techniques similar to standard gamble methods, which is recommended for understanding individuals’ preferences under uncertainty.37,38 QOL statements were adapted from research that described life with lung cancer among patients limited by lung disease with a focus on functional states and physical limitations.36 Participants were asked whether they would accept any one of six functional limitations for additional years of life. For example, participants were asked “Would you accept loss of independence through permanent placement in a nursing home for one additional year of life. For “No” responses the additional years of life were increased to determine patient thresholds.

| Would you accept (insert phrase a-f) for 1 additional year of life? |

|---|

| a. Increased shortness of breath where I can walk only 2 blocks without stopping |

| b. Oxygen dependence where I may be on oxygen all or most of the day |

| c. Reduction of current activity level by half |

| d. Assistance with things like bathing, dressing, and being able to move from one place to another (bed to couch) |

| e. Loss of independence through permanent placement in a nursing home |

| f. Being limited to a bed or chair all of the time |

2.2. Discrete Treatment Choice Questions

Participants answered discrete choice questions39“42 offering a choice between two unnamed lung cancer treatments that described the potential harms and benefits of these treatment options: i) less serious complications affecting QOL, but higher rate of recurrence (i.e., similar to SBRT) and ii) chance of periprocedural death with better chance for cure (i.e., similar to surgery). Discrete choice methods assess the value of an option determined by the values of its attributes.40,43‘45 Discrete choice experiments (DCEs) are increasingly being used in healthcare applications46 and among patients with lung cancer.35 In DCEs, a pairwise comparison of hypothetical alternatives is presented and participants are asked to choose between them.47 DCEs are practical as participants are forced to make trade-offs between attributes and their levels, which mimic trade-off decisions which are part of everyday life. For cancer treatments, this means that the outcomes of a treatment can be described by their attributes and the extent to which an individual values the treatment, depends on how much they value the attributes.39,40,42

| When considering lung cancer treatment, would you prefer a treatment with: (choose A or B): | ||

|---|---|---|

| A. Serious complications including death and a better chance to be cured | OR | B. Less serious complications that may only reduce your quality of life like shortness of breath, but more of a chance the cancer may come back in a few years |

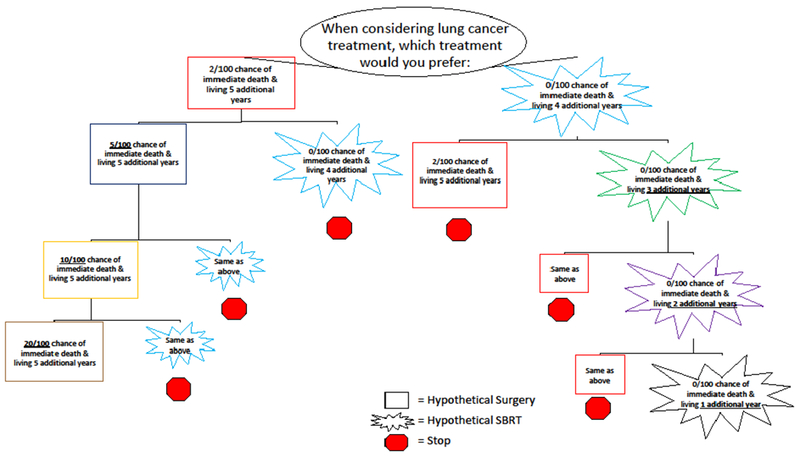

In the second set of DCE questions, the strength of participants’ treatment preference was assessed between descriptions of two unnamed lung cancer treatments (i.e., that were similar to SBRT and surgery) by varying the attributes and risks associated with these treatment options. In the follow-up series of questions, these attributes were adjusted to determine participants” strength of treatment preference. (Figure 1) For instance, if a participant initially selected the surgery description, the percent chance of periprocedural death, associated with this option, was increased in the next set of question options to make the alternative treatment (i.e., SBRT), which was unchanged from the previous scenario, seem more desirable. The DCE ended when a participant switched their treatment choice or chose the same treatment in four consecutive scenarios, scores ranged from 1-4.

| When considering lung cancer treatment, which treatment would you prefer: (choose A or B): | ||

|---|---|---|

| A. 2 out of 100 chances of immediate death and living 5 additional years | OR | B. 0 out of 100 chances of immediate death and living 4 additional years |

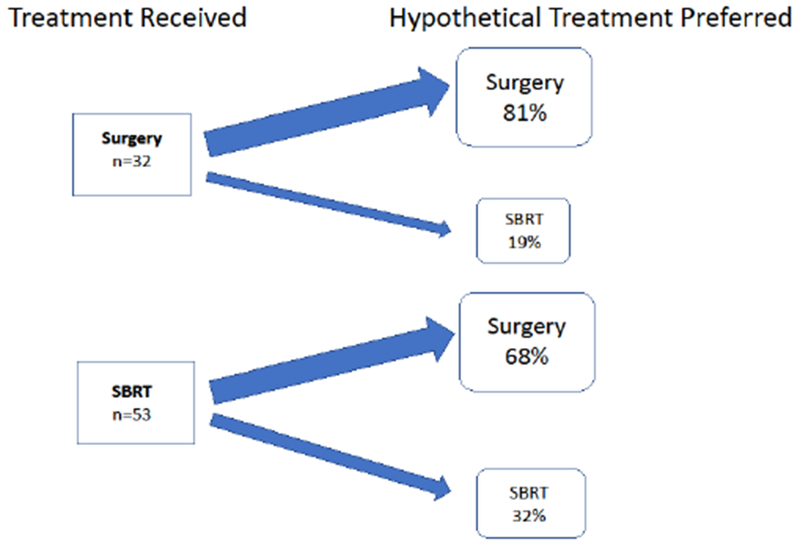

Figure 1.

Treatment Discordance: Disagreement between Treatment Received and Hypothetical Treatment Preferred among Patients with Early Stage Lung Cancer

Almost half of all patients (49%) preferred the alternative hypothetical lung cancer treatment compared to what they received. Treatment discordance was higher among patients who received SBRT (68%) compared to those who received surgery (19%). There were 29 missing responses (15 SBRT and 14 surgery patients). Abbreviation: SBRT= stereotactic body radiation therapy

2.3. Decisional Conflict, Communication Quality and Health-related Quality of Life

These measures were evaluated at participants’ baseline and 4-6 month visits, and were included as they were thought to potentially influence participants’ values and preferences. These measures were part of the larger, longitudinal study and reflected actual lung cancer care received, not hypothetical scenarios. Decisional conflict was measured using the Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS), a multi-dimensional tool of 16 items divided into five subscales: personal uncertainty, deficits of feeling uninformed, unclear values, inadequate support, and perception that an ineffective choice has been made. Items are scored using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree).48,49 Scores < 25 indicate no decision making difficulty and scores > 37.5 suggest delayed decision making or uncertainty about decision-making. Quality of self-reported clinician communication regarding lung cancer treatment options and subsequent follow-up care was measured using the patient-centered communication (PCC) tool.50 Overall communication quality was measured using participants’ response to the statement “The overall quality of communication with your clinician is excellent” (question 6A) on the PCC.51 Responses are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 0-7, from “very strongly agree” to “very strongly disagree”; lower scores indicate a higher degree of communication quality. Health-related QOL (HRQOL) was assessed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30).52 The EORTC QLQ-C30 contains 30 items covering health issues relevant for cancer patients, 24 of which are aggregated into scales measuring functioning, symptoms and global health, and quality of life. A higher score indicates a better level of functioning or global QOL.53,54

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and bivariate analyses were conducted using t-tests with continuous and chi-squared tests with categorical variables, as appropriate (Table 1: categories were collapsed where indicated). To address hypotheses related to participants’ values, three patient value responses were possible (most important, least important or not important). We weighted the responses as follows: most important= +2, least important= +1 and not important= 0. All patient responses were summed and values were ranked based on total summary scores. Sensitivity analyses were conducted (i) weighting participants’ responses to values as most important= +2, least important= +1 and not important= −1 and (ii) the percentage of participants’ responses to values as most, least, or not important were calculated. Findings were similar to the primary analysis.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Treatment Received

| Treatment Received | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| SBRT n=68 | Surgery n=46 | p value | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 73 (8.1) | 67 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| Sex, male | 47 (69%) | 27 (59%) | 0.25 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.32 | ||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 63 (93%) | 40 (87%) | |

| Black/Hispanic/Asian/Other | 5 (7%) | 6 (13%) | |

| Education | 0.15 | ||

| High School Degree or Less | 22 (32%) | 13 (28%) | |

| Some College | 27 (40%) | 26 (57%) | |

| College or Post-Graduate Degree | 19 (28%) | 7 (15%) | |

| Employment | 0.15* | ||

| Full or Part-Time | 8 (12%) | 10 (22%) | |

| Retired or Not Working | 55 (81%) | 27 (59%) | |

| Disabled | 5 (7%) | 9 (20%) | |

| Marital Status | 0.03 | ||

| Married | 22 (32%) | 28 (61) | |

| Not Married | 46 (68%) | 18 (39) | |

| Household Income ($) | 0.27* | ||

| <30,000 | 32 (48%) | 17 (37%) | |

| 30,000-59,999 | 23 (34%) | 14 (30%) | |

| ≥60,000 | 11 (16%) | 13 (28%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (3%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Tobacco Smoking Status | 0.25* | ||

| Past | 47 (69%) | 36 (78%) | |

| Current | 18 (26%) | 8 (17%) | |

| Never | 3 (4%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Comorbidities# | |||

| COPD | 38 (56%) | 18 (39%) | 0.08 |

| Depression | 10 (15%) | 15 (33%) | 0.02 |

| Health System | 0.003 | ||

| VA Portland Health Care System | 35 (51%) | 20 (43%) | |

| Oregon Health & Science University Hospital | 10 (15%) | 19 (41%) | |

| Community Hospital | 23 (34%) | 7 (15%) | |

| Who First Discussed Treatment Options | 0.002* | ||

| Pulmonologist | 30 (44%) | 19 (41%) | |

| Thoracic Surgeon | 9 (13%) | 18 (39%) | |

| Oncologist | 8 (12%) | 3 (7%) | |

| Primary Care Clinician | 6 (9%) | 3 (7%) | |

| Radiation Oncologist/Other | 9 (13%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Not Applicable/Unknown | 6 (9%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Written Treatment Materials Provided | 0.50 | ||

| Yes | 8 (13%) | 10 (24%) | |

| No | 17 (27%) | 11 (26%) | |

| Can’t recall | 8 (13%) | 5 (13%) | |

| Not Applicable | 30 (48%) | 16 (38%) | |

| Decisional Conflict Scale score, mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 14.6 (11.8) | 15.0 (12.1) | 0.87 |

| Current Visit | 13.3 (14.4) | 8.9 (9.6) | 0.09 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 Global score, mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 70.6 (22.2) | 76.2 (19.3) | 0.16 |

| Current Visit | 70.5 (22.2) | 75.6 (22.7) | 0.26 |

| Patient-Centered Communication score, mean (SD) | |||

| Baseline | 2.34 (0.82) | 2.39 (0.69) | 0.70 |

| Current Visit | 2.34 (0.84) | 2.35 (0.79) | 0.97 |

| 1-Year Mortality | 6 (9%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Cancer-related | 3 (4%) | - | |

| Other | 2 (3%) | - | |

| Unknown | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | |

Collapsed low frequency categories

self-reported. Abbreviations: COPD= Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, EORTC QLQ-C30= European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30, SBRT= stereotactic body radiation therapy and SD=standard deviation.

For the subsequent value questions, we examined the percent of participants who were willing to accept the statement given the potential trade-off (i.e., chance for periprocedural death or QOL scenario) for additional years of life. Based on responses, these questions were modified to determine patient thresholds- either the chance for periprocedural death or additional years of life were increased based on participants’ responses. Treatment concordance was defined as exact agreement between cancer treatment received and the hypothetical cancer treatment preferred that was most similar in attributes to SBRT or surgical resection. To compare participants’ mean decisional conflict, communication quality and QOL by treatment concordance, univariate linear regression was used. Strength of treatment preference was recorded as a numeric indicator for the switch-point (i.e., choice when a patient switched their treatment preference) higher scores indicated stronger strength of treatment preference. Missing responses were <27% to any single question and characteristics of participants with missing responses were similar to the cohort without missing responses. All analyses were performed using STATA version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and two-sided statistical significance was defined as a resultant p-value of <0.05.

3.0. Results

Among the 114 participants studied, mean age was 70 years (SD 7.9). The majority were male (65%), white (91%) and past cigarette smokers (73%). (Table 1) Among all participants, 68 (60%) received SBRT and 46 (40%) received surgery. Among these two groups, participants who received SBRT compared to surgery were older 73 (SD 8.1) versus 67 (SD 6.4) years-old, and less likely to be married (32% versus 61%, respectively) (all p<0.05). Participants who received SBRT compared to surgery were less likely to discuss treatment options first with a thoracic surgeon (13% versus 39%, respectively), or to be depressed (15% versus 33%, respectively) (all p<0.05). Compared to those who received surgery, participants who received SBRT had similar 4-6 month visit decisional conflict scale scores (13.3 versus 8.9, respectively), clinician communication quality scores (2.34 versus 2.35, respectively) and EORTC QLQ-C30 global health scores (70.5 versus 75.6, respectively) (means, all p>0.05).

Based on review of the EHR, 16 (24%) participants who underwent SBRT experienced one or more acute complications which were mostly fatigue and chest wall/rib pain. Two (3%) participants experienced one or more chronic complications which were increased dyspnea or increased oxygen needs. Regarding treatment-related surgery complications, 18 (39%) participants experienced one or more acute complications which included persistent lung air-leak, re-intubation, pneumonia, atrial fibrillation, hospital re-admission, sepsis, delirium, and urinary tract infection. Among those who received SBRT, one participant was hospitalized for five days and spent a day in the ICU for a pneumothorax with persistent air-leak. Among those who received surgery, mean hospital and ICU LOS were 4.4 (SD 2.8) and 2.1 (SD 2.2) days, respectively.

3.1. Values

Participants reported “being able to remain in my own home” and “being able to take care of myself” as most important on 75% and 66% of surveys, respectively. (Table 2) Participants also reported survival and cancer recurrence as most important on 55% and 44% of surveys, respectively. After rank ordering participants’ responses to determine those of highest and lowest value, “being able to remain in my own home”, “being able to take care of myself”, “additional years of life” and “chance the lung cancer returns” were the four highest weighted values. The lowest weighted values were “staying away from regular visits to doctors and hospitals” and “costs of treatment”. Among both groups, the highest weighted value was the same: “being able to remain in my own home”. However, participants who received surgery reported “chance the lung cancer returns” while those who received SBRT reported “being able to take care of myself” as the second most important weighted value. Both groups reported “costs of treatment” as the lowest weighted value. The remaining value statement rankings were similar between groups.

Table 2.

Patients’ Values when Considering Lung Cancer Treatment, by Group

| Treatment Received | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Value Statement | All Patients Rating Score (rank) | SBRT Group Rating Score (rank) | Surgery Group Rating Score (rank) |

| n=l 14 | n=68 | n=46 | |

| Being able to remain in my own home | 183 (1) | 114 (1) | 69 (1) |

| Being able to take care of myself | 162 (2) | 104 (2) | 58 (4) |

| Additional years of life | 147 (3) | 88 (3) | 59 (3) |

| Chance the lung cancer returns | 138 (4) | 78 (4) | 60 (2) |

| Being a burden to my spouse, family or friends | 126 (5) | 69 (5) | 57 (5) |

| Physical side effects of treatment | 106 (6) | 56 (6) | 50 (6) |

| Staying away from intensive medical care | 74 (7) | 54 (7) | 20 (8) |

| Emotional side effects of treatment | 64 (8) | 30 (8) | 34 (7) |

| Staying away from regular visits to doctors and hospitals | 51 (9) | 32 (9) | 19 (9) |

| Costs of treatment | 44 (10) | 28 (10) | 16 (10) |

Score= total summed score from all patient responses was weighted as follows: most important=+2, least important +1 and not important=0. Abbreviations: SBRT= stereotactic body radiation therapy

Participants placed a higher value on additional years of life versus the surgical complication of periprocedural death. Overall, 76/92 (83%) of participants were willing to accept a 2% chance of periprocedural death for 1 additional year of life (89% among SBRT and 74% among surgery participants). Additionally, 59/92 (64%) participants were willing to accept a 10% chance of periprocedural death for 1 additional year of life and 48/92 (52%) participants were willing to accept a 20% chance of periprocedural death for 1 additional year of life. Only 10/92 (11%) participants were unwilling to accept a 2% of periprocedural death for 4 additional years of life, the lowest risk for the maximum benefit offered. Differences between treatment groups appeared to be minimal as there was only a 12-15% difference/question by group. However, participants who received SBRT consistently valued length of life more as they were willing to accept a high chance of periprocedural death for few additional years of life.

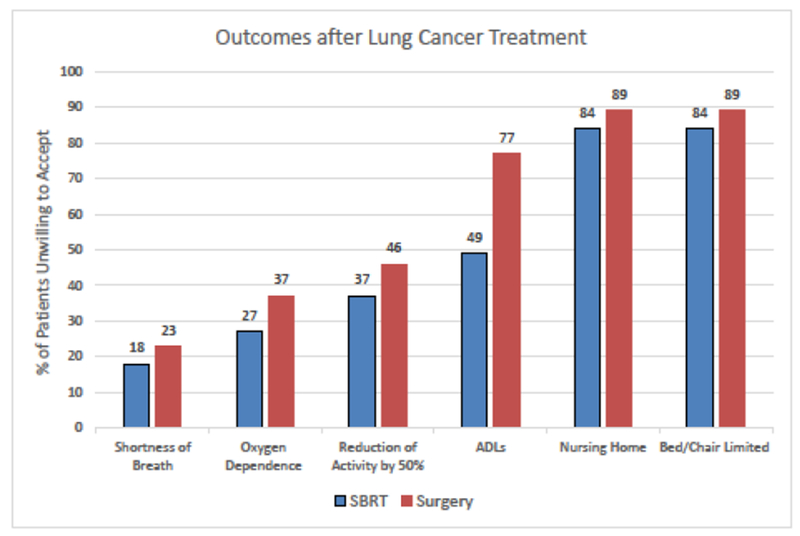

Participants generally valued QOL more than length of life, as most participants were unwilling to accept needing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) as a potential outcome of cancer treatment. Participants were more willing to accept increased shortness of breath, oxygen dependence or reduction in current activity level; however, assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), permanent placement in a nursing home or being limited to a bed/chair were not acceptable to most participants for additional years of life. (Figure 3) In fact, 86% of participants were unwilling to accept either permanent placement in a nursing home and being limited to a bed/chair for the maximum number of additional years of life offered. Participants who received SBRT consistently valued length of life more, as they were more willing to accept changes in QOL for additional years of life. The largest difference between groups was unwillingness to accept assistance with ADLs for four additional years of life gained (SBRT=49% versus surgery=77%).

Figure 3.

Patients’ Unwillingness to Accept Possible Outcomes after Lung Cancer Treatment

The percent of participants who received SBRT or surgery (y-axis) who were unwilling to accept the potential outcomes (x-axis) after lung cancer treatment for an additional 4 years of life (maximum value offered). Overall, participants who received surgery (red bars) were more risk averse, as they were less likely to accept any of the potential outcomes compared to participants who received SBRT (blue bars). Complete “outcomes after lung cancer treatment” statements: Shortness of Breath= Increased shortness of breath where I can walk only 2 blocks without stopping, Oxygen Dependence= Oxygen dependence where I may be on oxygen all or most of the day, Reduction of Activity by 50%= Reduction of my current activity level by half, ADLs= Assistance with things like bathing, dressing, and being able to move from one place to another, Nursing Home= Loss of independence through permanent placement in a nursing home, and Bed/Chair Limited= Being limited to a bed or chair all the time. Abbreviations: ADLs= Activities of Daily Living and SBRT= stereotactic body radiation therapy. (Adapted from Cykert S, et al. Chest. 2000 Jun;117(6):1551-9.)35

3.2. Treatment Preferences

Overall, 42 (49%) participants reported they preferred the alternative hypothetical lung cancer treatment than what they actually received. (Figure 1) Treatment concordance was lower among participants who received SBRT (32%) compared to participants who received surgery (81%). Treatment-related complications did not seem to be associated with increased discordance as 37% of concordant participants experienced ≥1 acute complication compared to 21% of discordant participants. Treatment concordance was not associated with decisional conflict, communication quality or HRQOL (all p>0.05).

Overall, participants’ strength of treatment preference was weak as 22 (58%) participants who chose surgery and 37 (73%) participants who chose SBRT initially, switched their treatment preference within the first two follow-up DCE questions. (Table 3) (Figure 2) A higher switch-point means a higher strength of preference for a particular treatment. Among treatment groups, mean strength of preference for SBRT (mean switch-point by group, SBRT=1.9 and surgery=1.9) and surgery (mean switch-point by group, SBRT=2.3 and surgery=2.7) were similar. Among the entire cohort, strength of preference was higher for surgery compared to SBRT as the mean switch-point was 2.4 (SD 1.2) versus 1.9 (1.2).

Table 3.

Strength of Treatment Preferences among Patients with Early Stage Lung Cancer, by Group

| Treatment Received | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients n=89 n(%) | SBRT n=53 n(%) | Surgery n=36 n(%) | |

| Choose Hypothetical Surgery* (2% chance of immediate death & living 5 additional years) | 38 (43) | 23 (43) | 15 (42) |

| Switch-point to SBRT | |||

| 1st Choice (dark blue cloud) (5% chance of immediate death & living 5 additional years) | 10 (26) | 7 (30) | 3 (20) |

| 2nd Choice (yellow cloud) (10% chance of immediate death & living 5 additional years) | 12 (32) | 7 (30) | 5 (33) |

| 3rd Choice (brown cloud) (20% chance of immediate death & living 5 additional years) | 4 (11) | 3 (13) | 1 (7) |

| Always choose Surgery (4 choices) | 11 (29) | 5 (22) | 6 (40) |

| NA | 1 (3) | 1 (4) | - |

| Switch-point from hypothetical surgery to hypothetical SBRT, mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.2) |

| Choose Hypothetical SBRT* (0% chance of immediate death & living 4 additional years) | 51 (57) | 30 (57) | 21 (58) |

| Switch-point to Surgery | |||

| 1st Choice (green zap) (0% chance of immediate death & living 3 additional years) | 24 (47) | 14 (47) | 10 (48) |

| 2nd Choice (purple zap) (0% chance of immediate death & living 2 additional years) | 13 (25) | 8 (27) | 5 (24) |

| 3rd Choice (black zap) (0% chance of immediate death & living 1 additional years) | 5 (10) | 2 (7) | 3 (14) |

| Always choose SBRT (4 choices) | 7 (14) | 5 (17) | 2 (10) |

| NA | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 1 (5) |

| Switch-point from hypothetical SBRT to hypothetical surgery, mean (SD) | 1.9 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.1) | 1.9 (1.0) |

No lung cancer treatment names were used, only treatment attributes similar surgical resection or SBRT. There were 25 missing responses (17 SBRT and 8 surgery patients). Abbreviations: SBRT= stereotactic body radiation therapy, SD=standard deviation, and NA=not applicable (patients did not answer subsequent questions after an initial choice)

Figure 2.

Question Tree for Strength of Treatment Preference among Patients with Early Stage Lung Cancer

When determining participants’ strength of hypothetical treatment preference, choice options were modified in a series of questions based on participants’ responses. As below, if a participant chose A (i.e., surgery), then the chance of immediate death was increased from 2 to 5% in the hypothetical treatment option, that was similar to surgical resection, and the options were represented to the participant. This series of questions determined the strength of participants’ preference for the hypothetical treatment initially selected. The switch-point is the choice option when participants switched their choice from one treatment to the other (e.g., A to B). All choice option modifications are bolded and underlined. Choices are color-coded (i.e., all red boxes represent identical choice options)

4.0. Discussion

Among participants with early stage lung cancer who received either SBRT or surgical resection for curative intent, more participants valued QOL and independence highly compared to survival or cancer recurrence. Participants were willing to accept a high chance of periprocedural death for only one additional year of life, but were not willing to accept significant deficits in QOL for four additional years of life. SBRT participants were more likely to accept both periprocedural death or deficits in QOL compared to surgery participants. Considerable discordance exists regarding lung cancer treatments, as about half of all participants preferred the hypothetical alternative treatment than what they received. However, overall strength of treatment preference for either group was weak. Clinical guidelines for early stage lung cancer treatment could be more patient-centered by increasing the emphasis on patient – centered outcomes that patients value (i.e., QOL). Treatment decision conversations, especially when clinical equipoise exists, should focus on eliciting patients’ values and preferences to ensure decisions are consistent with patients’ priorities and goals.

When examining value and preference differences among patients who receive SBRT or surgery, it is important to understand possible differences between these groups. According to American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) guidelines, SBRT has a significant role to play in treating early stage NCSLC, particularly for patients ineligible for surgical resection.55 As a result, in our cohort, most participants who received SBRT were not operable candidates as they were older, had more comorbidities and lower HRQOL compared to surgery participants. Loss aversion and prospect theory,56,57 people’s tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains, may help explain why participants who received surgery were less willing to accept periprocedural death or deficits in QOL compared to SBRT participants, as participants who received surgery were younger with higher HRQOL (i.e., better QOL), compared to those who received SBRT. Older patients are thought to be less risk averse than younger patients,58,59 however, age did not fully explain differences in our study.

Overall, more participants in each group reported higher value for independence and QOL compared to survival or cancer recurrence when considering treatment options. Previously, qualitative studies have suggested survival was more important than QOL,60 however, studies were limited by small sample size limitations and mostly focused on patients with advanced lung cancer. Previous studies in patients with advanced disease do demonstrate the high value patients place on symptom control, which impacts QOL, when considering treatment.35,61 Unfortunately, evidence-based guidelines often overemphasize survival when weighing the potential benefits of lung cancer treatment,16,17 while largely ignoring QOL outcomes. This dichotomy is important, as there was no association between QOL and progression-free survival among cancer patients.62 In the future, randomized controlled trials of lung cancer treatment should be powered to assess differences in patient-centered outcomes such as QOL.

Surprisingly, about half of the participants experienced treatment discordance, preferring the hypothetical alternative treatment that what they received, based on the descriptions of treatment attributes. This finding may highlight the feasibility of a trial examining these treatments among patients with early stage lung cancer. There are many factors that may have contributed to this finding. In a previous study from the Netherlands, patients with early stage NSCLC reported a lack of knowledge about the advantages and disadvantages of treatment options, however, 74% still felt they were sufficiently involved in decisionmaking.15 Additionally, our study occurred sometime after treatment receipt, participants had time to weigh treatment options that were less affected by the information overload that often occurs around the time of diagnosis,63 which may have affected preferences. Most SBRT participants in our study were not operable candidates and this may have manifested as psychological reactance, the motivation to regain a freedom after it has been lost or threatened.64 However, only attributes of treatments and not actual treatment names were used, reducing the influence of reactance. Neither actual treatment complications nor outcomes likely affected treatment discordance, as both were similar among concordant and discordant participants. Improving health literacy is an important strategy to improve the quality of SDM,65,66 however, almost three-quarters of our cohort had a high educational level including some college which may limit the effectiveness of this approach. Treatment discordance may have resulted from under-informed participants as few participants in our cohort received written materials regarding their lung cancer treatment options, however, few evidence-based resources exist.

Decision support tools such as decision aids for cancer treatment have been found to reduce decisional conflict, increase patient knowledge and satisfaction, encourage active patient involvement in decision-making, and decrease levels of anxiety and distress among patients with breast67 and prostate cancer.68 The use of written materials and/or decision aids in early stage lung cancer may help reduce treatment discordance and improve the decision making process, although resources are scarce. Developing effective written materials and/or decision aids must consider several factors. Choices must be made about how to present the risks and benefits of treatment options and how to elicit patient values. For example, when presenting treatment options, framing (i.e., the way outcomes are described) can affect patient preferences.69 The same outcome data presented in terms of probability of death (i.e., mortality) or probability of living (i.e., survival) affect patients’ choices regarding lung cancer treatment.70 A common misconception is that any written materials or decision aids simply need to be designed to “reveal” the stable, inherent preferences that patients have regarding medical treatments and the risk and benefits thereof. Contemporary research from a variety of domains suggests that in many cases this common conception is false and individuals, in fact, construct preferences in the moment of choice.71 In other words, for many important life decisions people do not have stable preferences that can be readily applied and preferences must be constructed at the moment making them very sensitive to current internal states (e.g., emotions) and the structure of the environment or context (e.g., exactly how options, risks and benefits are presented).72 This idea of constructed preferences and the lack of resources available to patients around the time of cancer diagnosis, may help explain the relatively weak strength of treatment preference patients demonstrated in our study. Without reliable resources to assist in decision making, patients likely did not have a clear foundation on which to base these difficult treatment decisions. This is not to say that everything is constructed and people have no stable preferences at all.73 It does suggest, however, that the developers of written materials and decision aids within this and any domain should think carefully about how to present information to facilitate a process of preference construction that is in the best interest of patients.

This study has limitations. Participants were surveyed 4-6 months following lung cancer treatment and preferences may have changed, however, once established, preferences are thought to be stable over time.74 Patients completed surveys via phone with a trained research assistant using a standardized question guide, however, participants’ understanding of concepts and numeracy are important factors in decision making.75 Our high survey completion rate may have been partially attributable to participants’ high level of education and results may not be generalizable. Imputation for missing responses was not done given the complex nature of value clarification and DCEs. Multiple steps are involved in the structure, design and evaluation of a DCE, for the present study some aspects were derived from previous sources. Values clarification were closed-ended, meaning participants could not add concerns that were not already listed, limiting the scope of comparisons. Assessing patients’ decision making and preferences are typically employed when uncertainty exists prior to decision-making, however, these techniques are also effective when employed after treatment decisions have already been made among patients with lung cancer,76 consistent with our study design. We acknowledge important next steps are to study treatment discordance among treatment-naive patients with early stage lung cancer.

4.1. Conclusion

Traditional clinical trial metrics of cancer treatment superiority, survival and cancer recurrence, were less highly valued among participants with early stage lung cancer than metrics often ignored, maintaining independence and QOL. Participants who received either SBRT or surgery were willing to accept high periprocedural mortality, but not significant deficits to their QOL as a trade-off for additional years of life. Surprisingly, considerable treatment discordance exists among participants with early stage lung cancer as about half preferred the alternative treatment. It is essential to elicit and understand patients’ values and preferences regarding potentially life-altering medical decisions, such as lung cancer treatment. Clinicians likely need more resources to foster high-quality shared decision making and ensure choices are consistent with patients’ values, preferences and goals.

Highlights:

More patients valued independence and QOL compared to survival and recurrence

49% of early stage patients had treatment discordance, preferring the alternative

Resources are needed to aid clinicians during lung cancer treatment discussions

Understanding patients’ values and is essential to foster shared decision-making

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank all the patient participants that contributed to this study. This study is the result of work supported by resources from the Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Portland, Oregon. The Department of Veterans Affairs did not have a role in the conduct of the study, in the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of data, or in the preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Funding: Dr. Sullivan is supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K07CA190706. This study is supported by an award from the Radiation Oncology Institute (ROI2013-915, Radiation Therapy & Patient-Centered Outcomes among Lung Cancer Patients) and by resources from the VA Portland Health Care System, Portland, Oregon. Dr. Slatore was supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (CDA 09-025) while the study was ongoing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors whose names are listed above certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sugimura H, Yang P. Long-term survivorship in lung cancer: A review. Chest. 2006; 129(4): 1088–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sloan JA, Zhao X, Novotny PJ, et al. Relationship between deficits in overall quality of life and nonsmall-cell lung cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13): 1498–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan DR, Forsberg CW, Ganzini L, et al. Longitudinal changes in depression symptoms and survival among patients with lung cancer: A national cohort assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(33):3984–3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang P, Cheville AL, Wampfler JA, et al. Quality of life and symptom burden among long-term lung cancer survivors. JThorac Oncol. 2012;7(1):64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenny PM, King MT, Viney RC, et al. Quality of life and survival in the 2 years after surgery for non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(2):233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics. Monitoring the nation’s health, trends in health and aging, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/agingact.htm 2018.

- 7.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final update summary: Lung cancer: Screening, July 2015 https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/lung-cancer-screening Published July 2015.

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Center for Clinical Standards and Quality. Decision memo for screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT). . 2015;CAG-00439N. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patient protection and affordable care act. . 2010;Public Law 111–148, 42 U.S.C. 18001 et seq. [Google Scholar]

- 11.LungCAN. Proposed decision memo for screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT). http://lungcan.org/2014/11/18/proposed-decision-memo-for-screening-for-lung-cancer-with-low-dose-computed-tomography-ldct. Accessed Dec 20, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheridan SL, Harris RP, Woolf SH, Shared Decision-Making Workgroup of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Shared decision making about screening and chemoprevention. a suggested approach from the U.S. preventive services task force. Am JPrevMed. 2004;26(1):56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tariman JD, Berry DL, Cochrane B, Doorenbos A, Schepp K. Preferred and actual participation roles during health care decision making in persons with cancer: A systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(6): 1145–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G. Patient preferences for shared decisions: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):9–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mokhles S, Nuyttens JJME de Mol M, et al. Treatment selection of early stage non-small cell lung cancer: The role of the patient in clinical decision making. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):79-018-3986-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Non-small cell lung cancer, 2017. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2018.

- 17.Bryant AK, Mundt RC, Sandhu AP, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy versus surgery for early lung cancer among US veterans. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(2):425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang CY, Lin YS, Tzao C, et al. Comparison of charlson comorbidity index and kaplan-feinstein index in patients with stage I lung cancer after surgical resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32(6):877–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhai R, Yu X, Shafer A, Wain JC, Christiani DC. The impact of coexisting COPD on survival of patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer undergoing surgical resection. Chest. 2014;145(2):346–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kravchenko J, Berry M, Arbeev K, Lyerly HK, Yashin A, Akushevich I. Cardiovascular comorbidities and survival of lung cancer patients: Medicare data based analysis. Lung Cancer. 2015;88(1):85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.British Thoracic Society, Society of Cardiothoracic Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland Working Party. BTS guidelines: Guidelines on the selection of patients with lung cancer for surgery. Thorax. 2001;56(2):89–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stokes WA, Bronsert MR, Meguid RA, et al. Post-treatment mortality after surgery and stereotactic body radiotherapy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(7):642–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lammers A, Mitin T, Moghanaki D, et al. Lung cancer specialists’ opinions on treatment for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: A multidisciplinary survey. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2018;3(2): 125–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitson BA, Groth SS, Duval SJ, Swanson SJ, Maddaus MA. Surgery for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review of the video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus thoracotomy approaches to lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(6):2008–16; discussion 2016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell HA, Tata LJ, Baldwin DR, Stanley RA, Khakwani A, Hubbard RB. Early mortality after surgical resection for lung cancer: An analysis of the english national lung cancer audit. Thorax. 2013;68(9):826–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laursen LO, Petersen RH, Hansen HJ, Jensen TK, Ravn J, Konge L. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy for lung cancer is associated with a lower 30-day morbidity compared with lobectomy by thoracotomy. Eur JCardiothorac Surg. 2016;49(3):870–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang JY, Senan S, Paul MA, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus lobectomy for operable stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: A pooled analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(6):630–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dubey S, Brown RL, Esmond SL, Bowers BJ, Healy JM, Schiller JH. Patient preferences in choosing chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Support Oncol. 2005;3(2): 149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nugent SM, Golden SE, Thomas CR,Jr, et al. Patient-clinician communication among patients with stage I lung cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5): 1625–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH 3rd, Morley JE Comparison of the saint louis university mental status examination and the mini-mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder--a pilot study. Am JGeriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.FLESCH R A new readability yardstick. JApplPsychol. 1948;32(3):221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witteman HO, Scherer LD, Gavaruzzi T, et al. Design features of explicit values clarification methods: A systematic review. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(4):453–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramsey S, Schickedanz A. How should we define value in cancer care? Oncologist. 2010;15 Suppl 1:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blinman P, Alam M, Duric V, McLachlan SA, Stockler MR. Patients’ preferences for chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review. Lung Cancer. 2010;69(2): 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muhlbacher AC, Bethge S. Patients’ preferences: A discrete-choice experiment for treatment of nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Eur JHealth Econ. 2015;16(6):657–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cykert S, Kissling G, Hansen CJ. Patient preferences regarding possible outcomes of lung resection: What outcomes should preoperative evaluations target? Chest. 2000; 117(6): 1551–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torrance GW, Thomas WH, Sackett DL. A utility maximization model for evaluation of health care programs. Health Serv Res. 1972;7(2): 118–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gafni A The standard gamble method: What is being measured and how it is interpreted. Health Serv Res. 1994;29(2):207–224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blinman P, King M, Norman R, Viney R, Stockler MR. Preferences for cancer treatments: An overview of methods and applications in oncology. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(5): 1104–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lancaster KJ. A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy. 1966;74:132–157. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bryan S, Dolan P. Discrete choice experiments in health economics. for better or for worse? Eur J Health Econ. 2004;5(3):199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryan M, Farrar S. Using conjoint analysis to elicit preferences for health care. BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1530–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McFadden D Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior In: Zarembka P, ed. Frontiers in econometrics. New York: Academic Press; 1974:105–142. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salkeld G, Solomon M, Butow P, Short L. Discrete-choice experiment to measure patient preferences for the surgical management of colorectal cancer. Br JSurg. 2005;92(6):742–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.King MT, Viney R, Hossain I, et al. Survival gains needed to justify the side effects of treatment for localized prostate cancer. JCO. 2009;27(15):5119. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M. Using discrete choice experiments to value health and health care. Dordrecht: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ben-Akiva ME, Lerman SR. Discrete choice analysis: Theory and application to travel demand. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995; 15(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Connor AM. User manual—Decisional conflict scale. . 1993, updated 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty JL, Lambert M, Poitras ME. Measuring patients’ perceptions of patient-centered care: A systematic review of tools for family medicine. Ann FamMed. 2011. ;9(2): 155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ. 2001;323(7318):908–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The european organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dinescu FV, Tiple C, Chirila M, Muresan R, Drugan T, Cosgarea M. Evaluation of health-related quality of life with EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35 in romanian laryngeal cancer patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(9):2735–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bergman B, Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Kaasa S, Sullivan M. The EORTC QLQ-LC13: A modular supplement to the EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30) for use in lung cancer clinical trials. EORTC study group on quality of life. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A(5):635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Videtic GMM, Donington J, Giuliani M, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for early-stage nonsmall cell lung cancer: Executive summary of an ASTRO evidence-based guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017;7(5):295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47(2):263–291. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kahneman D, Tversky A. Choices, values, and frames. Am Psychol. 1984;39(4):341–350. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mather M, Mazar N, Gorlick MA, et al. Risk preferences and aging: The “certainty effect” in older adults’ decision making. Psychol Aging. 2012;27(4):801–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fehr-Duda H, Bruhin A, Epper T, Schubert R. Rationality on the rise: Why relative risk aversion increases with stake size J Risk Uncertain. 2010;40(2): 147–180. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmidt K, Damm K, Prenzler A, Golpon H, Welte T. Preferences of lung cancer patients for treatment and decision-making: A systematic literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016;25(4):580–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bridges JF, Mohamed AF, Finnern HW, Woehl A, Hauber AB. Patients’ preferences for treatment outcomes for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A conjoint analysis. Lung Cancer. 2012;77(1):224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kovic B, Jin X, Kennedy SA, et al. Evaluating progression-free survival as a surrogate outcome for health-related quality of life in oncology: A systematic review and quantitative analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12): 1586–1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jensen JD, Carcioppolo N, King AJ, Scherr CL, Jones CL, Niederdieppe J. The cancer information overload (CIO) scale: Establishing predictive and discriminant validity. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(1):90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brehm JW. A theory of psychological reactance. Oxford, England: Academic Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Legare F, Ratte S, Stacey D, et al. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(5):CD006732. doi(5):CD006732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katz SJ, Belkora J, Elwyn G. Shared decision making for treatment of cancer: Challenges and opportunities. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(3):206–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zdenkowski N, Butow P, Tesson S, Boyle F. A systematic review of decision aids for patients making a decision about treatment for early breast cancer. Breast. 2016;26:31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin GA, Aaronson DS, Knight SJ, Carroll PR, Dudley RA. Patient decision aids for prostate cancer treatment: A systematic review of the literature. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(6):379–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211(4481):453–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McNeil BJ, Pauker SG, Sox HC Jr, Tversky A On the elicitation of preferences for alternative therapies. NEngl J Med. 1982;306(21):1259–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.The construction of preference. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. Accessed 2018/10/02 10.1017/CBO9780511618031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Halpern SD, Loewenstein G, Volpp KG, et al. Default options in advance directives influence how patients set goals for end-of-life care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):408–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Warren C, McGraw AP, Van Boven L. Values and preferences: Defining preference construction. WIREs Cogn Sci. 2011;2(2):193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singh JA, Sloan JA, Atherton PJ, et al. Preferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: A pooled analysis of studies using the control preferences scale. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(9):688–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Apter AJ, Paasche-Orlow MK, Remillard JT, et al. Numeracy and communication with patients: They are counting on us. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):2117–2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leighl NB, Shepherd FA, Zawisza D, et al. Enhancing treatment decision-making: Pilot study of a treatment decision aid in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(11): 1769–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]