Abstract

Molecular mechanisms of dark-to-light state transitions in flavoprotein photoreceptors have been the subject of intense investigation. Blue-light sensing flavoproteins fall into three general classes that share aspects of their activation processes: LOV domains, BLUF proteins and cryptochromes. In all cases, light-induced changes in flavin redox, protonation and bonding states result in hydrogen-bond and conformational rearrangements important for regulation of downstream targets. Physical characterization of these flavoprotein states can provide valuable insights into biological function, but clear conclusions are often not trivial to obtain owing to challenges in data collection and interpretation. In this chapter, we briefly review the three classes of flavoprotein photoreceptors and provide basic methods for their recombinant production, reconstitution with flavin cofactor, and characterization. We then relate best practices and special considerations for applying several types of spectroscopies, redox potential measurements, and X-ray scattering experiments to this family of flavoprotein. The methods presented are generally accessible to most laboratories.

Keywords: Protein purification, Visible spectroscopy, EPR spectroscopy, X-ray scattering, Crystallography

1. INTRODUCTION

Blue-light-sensing flavoproteins comprise a family of photoreceptors that are widely recognized for diverse physiological roles and an increasing number of applications in the realm of optogenetics. For example, blue-light regulatory responses in plants, such as entrainment of the circadian clock, phototropism, chloroplast movement, stomatal opening, flowering, and growth and repair, rely upon flavoprotein photoreceptors (Christie et al., 1998; Conrad, Manahan, & Crane, 2014; Crosson, Rajagopal, & Moffat, 2003; Losi & Gärtner, 2012, 2017). In addition, archaea, prokaryotes, bacteria, fungi, animals, and protists utilize flavoprotein light sensors for regulation of phototaxis, DNA repair, stress response, and metabolic processes, among other functions (Becker, Zhu, & Moxley, 2011; Losi & Gärtner, 2012; Losi, Polverini, Quest, & Gärtner, 2002; Singh, Doerks, Letunic, Raes, & Bork, 2009). Despite this breadth of physiological activity, the primary light-sensing mechanisms of the flavin-containing domains fall into a few general categories. Excitation of the flavin cofactor can induce hydrogen-bond rearrangements, redox chemistry, or covalent bond formation (Becker et al., 2011; Conrad et al., 2014; Losi & Gärtner, 2012) that lead to proximal conformational and structural changes in the local protein environment. The signals eventually propagate toward the protein surface and elicit alterations in protein-protein interactions to affect downstream signaling and ultimately biological behavior.

Although flavoprotein light sensors share a chromophore, the isoalloxazine ring, differences in photochemical responses are tuned by the protein environment, which makes understanding the specific molecular mechanism of signal activation, conversion, and transduction all the more critical for understanding biological function and enabling the rational design of responses in optogenetic applications. Of particular challenge is the characterization of transient intermediary states of the chromophore and protein conformation during photoconversion. Continued investigation of these properties will necessitate the use of robust spectroscopic methods and redox measurements. Such techniques often utilize the flavin cofactor as a spectroscopic handle to follow the unique properties of each redox state. Herein we discuss several biophysical methods useful for understanding how the flavin cofactor influences protein conformational state. As with other chromophoric systems, an armamentarium of spectroscopic techniques have been applied to flavoprotein photoreceptors; we do not attempt to be comprehensive in our coverage and instead focus on methods used extensively in our laboratory. Notable omissions are ultra-fast and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopies, for which we refer the reader elsewhere (Kennis & Groot, 2007; Li, Wang, & Zhong, 2013; Zoltowski & Gardner, 2011).

1.1. Classes of flavoprotein photoreceptors

Blue-light photoreceptors are grouped into three major classes based on the overall protein fold and mechanism of flavin activation: light-oxygen-voltage (LOV) domains, cryptochrome/photolyases, and blue light sensing using FAD (BLUF) domains.

1.1.1. Light-oxygen-voltage domains

LOV domains, typically found in plants and fungi and predicted to exist in animals (Krauss et al., 2009), are sensors for blue-light responses. These domains are a subset of the Per-Arnt-Sim superfamily and non-covalently bind to a molecule of either flavin mononucleotide (FMN) or flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD). LOV domains were first discovered in the plant phototropins (phot-1 and phot-2) in Arabidopsis and were determined to be important for phototropism in Arabidopsis (Christie et al., 1998; Christie, Swartz, Bogomolni, & Briggs, 2002; Crosson et al., 2003). Since their discovery, these domains have garnered steady interest, most recently in regard to engineering light-mediated signal transduction processes and optogenetics through the coupling LOV domains to effector domains (Ziegler & Möglich, 2015) and designing photoresponsive molecules (Seifert & Brakmann, 2018).

The canonical LOV photocycle forms a covalent cysteinyl-thioether adduct bond between a strictly conserved cysteine on the Eα helix and the C4a carbon of the flavin isoalloxazine ring. Whereas it is generally accepted that flavin excitation results in the singlet S1 state, which intersystem crosses to the triplet T* state, the subsequent steps to form the adduct state remain somewhat unclear. It was first proposed that the triplet state becomes protonated to form an ionic, charge-separated species between the C4a carbon and N5 nitrogen that then facilitates nucleophilic attack by the negatively-charged cysteinyl thiolate (Swartz et al., 2001). However, this suggestion has been contested by several electron spin resonance (ESR) and transient spectroscopy studies, claiming presence of a transient radical pair intermediate (Bauer, Rabl, Heberle, & Kottke, 2011; Kutta, Magerl, Kensy, & Dick, 2015; Schleicher et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2016). Regardless, subsequent cysteinyl-thioether bond formation and N5 nitrogen protonation cause conformational flipping of the conserved glutamine residue and hydrogen-bond reorganization that induces the release and unfolding of adjacent helices (Christie, Blackwood, Petersen, & Sullivan, 2015; Ganguly, Thiel, & Crane, 2017; Jones, Feeney, Kelly, & Christie, 2007; Peter, Dick, & Baeurle, 2012; Yee et al., 2015).

The mechanism of signal transduction encompasses a broad range of conformational changes within the protein (Herrou & Crosson, 2011). In phototropins, adduct formation is followed by release of the Jα helix and activates the serine/threonine kinase effector domain. In Vivid (VVD), a circadian clock fungal protein in Neurospora crassa, the adduct state causes rearrangement of the N-cap and formation of a rapidly exchanging dimer (Zoltowski et al., 2007; Zoltowski & Crane, 2008) that then represses the primary blue-light photoreceptor White Collar-1 (Chen, DeMay, Gladfelter, Dunlap, & Loros, 2010; Hunt, Thompson, Elvin, & Heintzen, 2010). Still other LOV-LOV interactions can result in the rotation or unfolding of the Jα helix to change interactions between effector domains, as in the stress response protein YtvA in Bacillus subtilis (Herrou & Crosson, 2011).

1.1.2. Blue light sensing using FAD domains

BLUF domains are primarily found in bacteria and play important roles in nucleotide metabolism, phototaxis, photosystem synthesis, and biofilm formation (Gomelsky & Klug, 2002; Jung et al., 2005; Kanazawa et al., 2010; Masuda, 2013; Masuda & Bauer, 2002). Unlike LOV domains, spectral changes between the dark and the lit states are minimal, with blue light excitation producing a reversible red-shift of ~ 10 nm, and both dark and lit states comprise the fully oxidized FAD (Masuda & Bauer, 2002). Crystal and solution state structures indicate that the domain has a ferrodoxin-like fold (Anderson et al., 2005; Grinstead et al., 2006; Jung et al., 2005; Jung, Reinstein, Domratcheva, Shoeman, & Schlichting, 2006), with the cofactor lying in between two parallel alpha helical chains and surrounded by a hydrogen-bonding network with four conserved, neighboring residues: Tyr, Gln, Trp, and Met, all of which have been established by mutagenesis to be essential for function (Dragnea, Waegele, Balascuta, Bauer, & Dragnea, 2005; Laan et al., 2006; Masuda, Hasegawa, & Ono, 2005b; Masuda, Hasegawa, Ohta, & Ono, 2008; Unno, Masuda, Ono, & Yamauchi, 2006).

Time-resolved spectroscopic studies have led to many proposed photochemical mechanisms that have been complicated by conflicting interpretations of spectroscopic and structural data. Spectroscopic experiments have suggested rapid formation of a transient flavin radical via proton-coupled electron transfer from an adjacent, conserved Tyr on the ultrafast timescale (Bonetti et al., 2008; Gauden et al., 2006), and other studies have demonstrated that the rate of electron transfer can be modulated by tuning the redox potential of flavin and Tyr (Mathes, Van Stokkum, Stierl, & Kennis, 2012). However, not all photoactive BLUF domain proteins generate this charge-separated species (Lukacs et al., 2014), and the role of the biradical state is still unclear. Additional Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) studies observed a downshift of the C4 carbonyl stretch by ~ 20 cm−1 after photoexcitation that points to changes in the hydrogen bond at the oxygen (Masuda, Hasegawa, Ishii, & Ono, 2004; Masuda, Hasegawa, & Ono, 2005a; Mathes & Götze, 2015) and is suspected to correspond to the red-shifted UV-Vis spectrum (Hasegawa, Masuda, & Ono, 2005). Rotation of the conserved Gln and keto-enol tautomerism to an imidic acid results in hydrogen-bond rearrangements that instigate Trp and Met conformational changes, which have been proposed to propagate the signal through a β-strand toward the attached effector region (Anderson et al., 2005; Domratcheva, Grigorenko, Schlichting, & Nemukhin, 2008; Masuda et al., 2005b).

1.1.3. Cryptochromes/photolyases

Cryptochromes (CRYs) and photolyases (PLs) are structurally homologous, both consisting of an N-terminal nucleotide-interacting Rossmann-fold domain and a C-terminal α-helical FAD-binding domain (Sancar, 2000); however, their functionalities vary distinctly. PLs have an additional light-harvesting antenna cofactor (typically a pteridine or deazaflavin moiety) that transfers light energy to the two-electron reduced flavohydroquinone (FADH–) during DNA repair (Ganguly et al., 2016; Mees et al., 2004; Sancar, 1994; Weber, 2005). The excited state of the FADH− then donates electrons to break the UV-generated cross-linked pyrimidine dimers via a cyclic electron-transfer reaction (Kao, Saxena, Wang, Sancar, & Zhong, 2005; Liu et al., 2011).

CRYs, on the other hand, are central signaling components in the circadian clock of animals and plants and exhibit other functions in other kingdoms (Cashmore, 2003; Cashmore, Jarillo, Wu, & Liu, 1999). Excitation of flavin cofactor is generally followed by electron transfer from the surface of the protein via a tryptophan chain or tetrad (Lin, Top, Manahan, Young, & Crane, 2018; Müller, Yamamoto, Martin, Iwai, & Brettel, 2015), reducing the cofactor to either the anionic semiquinone (ASQ) or following proton transfer from an adjacent Asp, Glu, or Asn (Hense, Herman, Oldemeyer, & Kottke, 2015; Iwata, Zhang, Hitomi, Getzoff, & Kandori, 2010; Kottke, Batschauer, Ahmad, & Heberle, 2006), the neutral semiquinone (NSQ), which ultimately causes the C-terminal extension or tail (CTT) to undergo a conformational change.

The different functionalities of CRYs and PLs are grouped into several subclasses: cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) PLs; 6–4 PLs; CRY-DASH; plant CRYs; and animal CRYs (Lin & Todo, 2005). In Drosophila CRY (dCRY), light excitation of the flavin cofactor results in the anionic semiquinone (ASQ) that is purported to alter the protonation state of a nearby His and induces the release of the CTT (Ganguly et al., 2016). dCRY then binds to the circadian clock co-repressor Timeless (TIM) and recruits Jetlag (JET), an E3-ubiquitin ligase, causing degradation of TIM and dCRY, which photoentrains and resets the circadian clock (Crane & Young, 2014). Presently though, it is uncertain which redox state (oxidized or ASQ) of animal-type CRY exists in vivo and contributes to downstream signaling (Öztürk, Song, Selby, & Sancar, 2008), although recent data show a strong correlation between flavin photoreduction and biological activity (Lin et al., 2018). Moreover, CRY has continued fervent interest owing to it being implicated in magnetoreception via generation of a radical pair upon photoactivation (Biskup et al., 2009; Foley, Gegear, & Reppert, 2011; Gegear, Foley, Casselman, & Reppert, 2010; Liedvogel & Mouritsen, 2010; Rodgers & Hore, 2009; Solov’yov, Chandler, & Schulten, 2007) and its possible applications in optogenetics for mammalian systems (Müller & Weber, 2013; Pathak, Vrana, & Tucker, 2013; Tischer & Weiner, 2014).

2. RECOMBINANT EXPRESSION AND PURIFICATION OF FLAVOPROTEINS

Obtaining properly folded protein samples is often not trivial. We have outlined several methods to improve the yield of soluble, flavin-incorporated proteins, including expression with CmpX13 cells (which are engineered to express the riboflavin transporter RibM), reconstitution with excess flavin, insect cell expression, and refolding from inclusion bodies.

2.1. Overexpression of proteins in Escherichia coli

2.1.1. Materials

BL21-DE3 cells (New England Biolabs) or CmpX13 cells (C41(DE3) manX::ribM) (Mehlhorn et al., 2013)

8 L of LB-Miller media

100 mM stock of isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)

Riboflavin

DNA constructs cloned into a T7 expression vector

Antibiotics to select for cells transformed with plasmid

Transform competent E. coli cells with the plasmid of choice and grow a 150-mL inoculation culture overnight (~ 16 h) in LB with the selective antibiotic at 37 °C.

Dilute an equivalent amount of inoculation culture into four flasks with 2 L of autoclaved LB-Miller media and antibiotic. Add 50–100 mg of riboflavin directly to each 2 L of media. Grow to an optical density at 600 nm (O.D.600) of 0.6–0.8 before reducing the temperature of the culture if necessary. Induce with 2 mL of 100 mM IPTG stock per flask. Express for the desired period of time. Note that the temperature and expression duration can be optimized through small-scale growths and visualization by SDS-PAGE. These conditions are highly dependent on the construct; for instance, VVD and dCRY express at 17 °C for 16 h, while BAT-LOV* and WC-1 (356–507) express at 37 °C for 3 h.

Collect cells by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 10 m and remove spent media. Store at − 20 °C until ready for next steps.

2.2. Isolation and purification of soluble proteins

2.2.1. Materials

Gel filtration buffer (GFB), pH buffered and passed through a 0.22-μm filter

Affinity column; Ni-NTA resin for His6 tags.

1 M stock of imidazole, pH 7

Resuspend cells in GFB. Lyse the cells on ice using a sonic dismembrator (2 s pulse at 30% power followed by 2 s pause, 4 m total time per cycle; 3 cycles in total). In the case of dCRY the cells were sonicated in 50 mM HEPES (pH 8), 400 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v), 10 mM imidazole, 0.5% Triton X-100 (v/v), 0.5 mM TCEP (fresh), and protease inhibitor. 10% glycerol acts as a stabilizing agent for some proteins and can be important to use throughout the purifications.

Centrifuge the mixture at 20,000 RPM for 1 h at 4 °C to remove cell detritus.

Flow supernatant through an affinity column. For a Ni-NTA column, wash the resin with 5 mL of GFB + 20 mM imidazole to remove nonspecifically bound proteins and then elute with 10 mL of GFB + 200 mM imidazole. Concentrate down the elution using centrifugal filter units.

Further purify the protein using an isocratic elution through a size-exclusion column (SEC) 26/100, collecting 6-mL fractions in the region of interest.

If the purity is still poor, the protein is likely highly unstable and changes to the buffer may help (glycerol, sodium chloride, adjusting the pH, etc.). An additional polishing step can be applied by using an anion or cation exchange column (Hi-Prep Q XL 16/10 or HiPrep CMFF 16/10, respectively). Elution with a gradual linear gradient (0–100%) of ionic strength can separate charged species.

Check for flavin incorporation by UV-Vis. Some constructs, such as BAT-LOV*, can bind to free flavin. For these proteins, add approximately 1 molar equivalent of free FAD or FMN to the solution with protein and incubate overnight at 4 °C. Exchange the buffer using a centrifugal filter unit until the flow through is colorless and free of flavin.

2.3. Isolation and purification of insoluble proteins

2.3.1. Materials

Lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol)

Denaturation buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT))

Refolding buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150–500 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, pH 7.5)

After lysing the cells in lysis buffer (see Step 1 in Section 2.2) and centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 m, white inclusion bodies will be visible at the bottom of the centrifugal tube. Wash the inclusion bodies by resuspending the pellet in lysis buffer + 1% (w/v) Triton-X and centrifuging at 12,000 × g for 10 m to remove the spent buffer. Remove all traces of the wash buffer by resuspending the pellet in lysis buffer and centrifuging again for 10 m. Resuspend the resultant pellet in denaturation buffer with dithiothreitol (DTT) to keep the thiol moieties reduced. Centrifuge the solution briefly to remove undissolved particulates.

Further purification can be accomplished by running the solubilized, denatured protein through a Ni-NTA column, washing and eluting the bound protein with denaturation buffer + imidazole.

Completely dissolve 1–3 mM of free FAD or FMN into the protein solution and slowly drip into 250 mL of refolding buffer with constant stirring at 4 °C. The dripping can be facilitated and controlled by placing the protein solution into a separatory funnel, anchoring it to a ring stand above the beaker, and gradually opening the stopcock until a slow, continuous drip is attained (1 drop per 5–10 s).

After the entire sample of denatured protein is added, stir at 4 °C for ~ 2–16 h. Remove precipitated protein by gravity filtration. Collect soluble protein either by affinity resin or by concentrating with a centrifugal filter. Remove excess flavin by buffer-exchange or dialysis. Check for flavin binding by looking for the three distinct vibronic peaks centered at 450 nm or for features of the reduced state using UV-Vis spectroscopy and test for photoreduction activity.

Note: Many variables go into the successful reconstitution of protein. Inclusion bodies must be unfolded to a degree that allows free flavin to interact and bind with the domain. However, if proteins are completely denatured, refolding to its native state is nigh impossible. As such, some studies recommend monitoring the unfolding behavior by circular dichroism and fluorescence. Other factors, including the protein concentration, refolding buffer, and temperature, can play critical roles on success and yield (Hefti, Vervoort, & Van Berkel, 2003). Additives, like arginine, in the refolding buffer have also been determined to aid in the refolding of flavoproteins from inclusion bodies (Cafaro et al., 2002; Leartsakulpanich, Antonkine, & Ferry, 2000). Also, use of phosphate buffers may be problematic when refolding flavin proteins, for the interaction of the backbone phosphate moieties directs binding of the isoalloxazine ring and free phosphate molecules may interfere with the binding kinetics, as in the case of apoflavodoxin (Hefti et al., 2003; Murray, Foster, & Swenson, 2003).

2.4. Insect cell expression

Cryptochrome proteins are often best expressed from insect cells. For Drosophila cryptochrome, the following protocols were followed:

Clone gene of interest into vector pFastBac-HTa (Invitrogen). The resultant plasmid provides for protein expression, with an N-terminal His6 tag and a TEV protease cleavage site under the control of a baculovirus-specific promoter.

Amplify the baculovirus by infecting Sf9 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.02 and incubation for 96 h at 27 °C using serum-free culture medium F900-II (Life Technologies Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) and a cell density at infection of 106 cells per mL. Collect culture supernatant containing the high-titer virus after centrifugation at 3000 × g for 10 m. at 4 °C and filter sterilized using a 0.2-μm sterile filter unit. The virus can be stored at 4 °C protected from exposure to direct light. The virus titer can be determined using a standard plaque enumeration assay by plating dilutions of the virus onto monolayers of Sf9 cells. By applying an agarose overlay, the plaques can be read after a 7 day incubation at 27 °C. Generally cells are grown for 72 h post infection. Cell pellets from 10 L productions were aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C.

Pellets from 2 L dCRY cultures are sonicated briefly in ca. 50 mL lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 5 mM imidazole, 300 mM NaCl and 10% (v/v) glycerol, pH 8.0). Sonication is conducted using a Fisher 550 sonic dismembrator at power level 6 for 1 m (2 s on, 2 s off). Centrifuge the lysate for 1 h at 58,000 × g and incubate the supernatant for 1 h with 2 mL of Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) with gentle rocking on ice. Transfer resin to a column, wash with lysis buffer and elute the protein eluted in lysis buffer supplemented with 100 mM imidazole, a lower concentration of NaCl (150 mM) and 2 mM DTT. Cleave the His6 tag by treating at 4 °C overnight with TEV protease. Cleaved protein can then be further purified by a Superdex 200 prep grade (SEC 26/60; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, pH 8.0. The yield is typically 40 mg of purified protein from 2 L of culture. Protein preparation should be carried out under red light or in the dark so as to minimize blue light exposure.

3. PHOTOREDUCTION/PHOTOACTIVATION OF FLAVOPROTEIN PHOTORECEPTORS

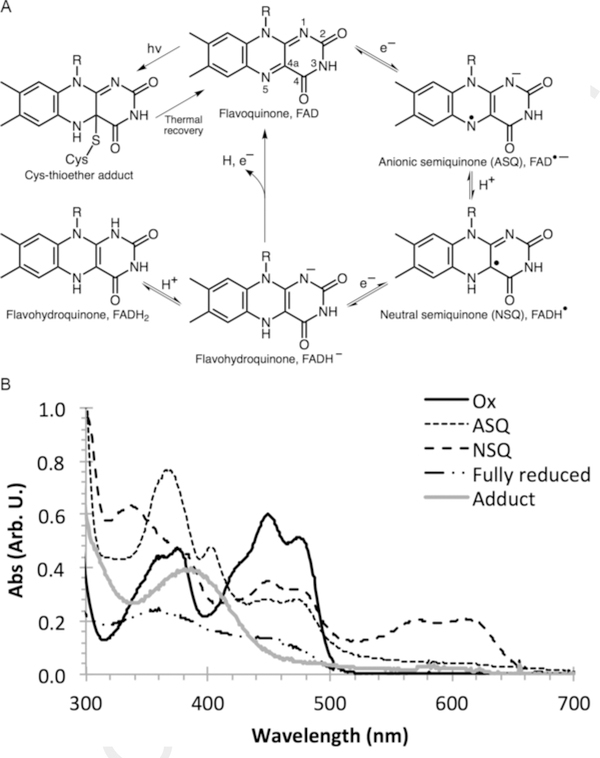

The flavin chromophore can be reduced or converted to one of several states (Fig. 1). These conversions are readily observed by irradiating free flavin in solution using blue light under anaerobic conditions with 10 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) as an extrinsic reductant (Frisell, Chung, & Mackenzie, 1958; Massey, Stankovich, & Hemmerich, 1978). The lifetime of these states can be extended by stabilizing the chromophore in a protein scaffold to regulate solvent accessibility and the rate of quenching.

Fig. 1.

(A) Redox states of flavin. Numbering convention is indicated in the oxidized flavoquinone structure. (B) Representative UV-Vis spectra of each flavin state.

Each redox state exhibits a unique, spectrophotometric handle. In general, excitation by UVA or blue light leads to an excited triplet state that then generates one of three reduced states. Recovery of the oxidized state requires the removal of H+ and 2e− and can be catalyzed by the presence of base, as in the case of LOV domain proteins (Alexandre, Arents, Van Grondelle, Hellingwerf, & Kennis, 2007; Zoltowski, Vaccaro, & Crane, 2009).

The decay of the 450 nm peak intensities can be followed to observe the kinetics of photoproduct formation. However, photobleaching is a pervasive concern with prolonged, intense light irradiation. Thus, it is recommended to also observe the development of new species and compare the rates of formation to the decay at 450 nm. Notably, some flavoproteins exhibit marked fluorescence during photoreduction, causing a broad, negative UV-Vis peak from ~ 475 nm to 600 nm that can interfere with absorption measurements, and so observation at these wavelengths should be avoided. Also worth noting, in the case of LOV-domain proteins, the apparent adduct-state lifetimes, which can be monitored through the return of the oxidized flavin spectrum from that of the adduct 390-nm species by UV/Vis spectroscopy, are strongly dependent on the frequency of data acquisition. Rapid sampling of LOV spectra with broad spectrum monitoring light causes net photo-induced repopulation of the adduct state. It is advisable to report lifetimes for the longest separation between sampling times after which no change in lifetime is observed (Zoltowski & Crane, 2008). Rates and lifetimes can be obtained by fitting the time traces to exponential curves using curve-fitting programs, such as MatLab (MathWorks) and MagicPlot (MagicPlot Systems, LLC).

The applications of photochemical studies in the flavoprotein field are ubiquitous and diverse. We have found UV-Vis spectroscopy to be most useful in comparing the photoactivity of different protein constructs. For instance, in the protein BAT-LOV*, we implemented a single Trp → Phe mutation that increased the quantum yield and rate of photoreduction to the NSQ state. Under similar light excitation conditions, an analogous active-Cys-less VVD variant was found to photoreduce at a slower rate (Yee et al., 2015).

3.1. Kinetics experiments by UV-Vis spectroscopy

3.1.1. Materials

UV-Vis spectrophotometer with an open top and temperature control (HP Agilent 8453 UV-Visible Spectrophotometer & Peltier Controller Module)

Microcuvette (Quartz, Starna cells, path-length of 0.2–1 cm only requires 10–80 μL of sample)

Laser source (World Star Tech laser; 30 mW; λ = 448 nm)

Neutral density filter

Ring stand and clamps

Using a ring stand for support, clamp the laser orthogonal to the UV-Vis observation path, aiming the center of the laser beam directly above the sample well of the microcuvette such that the entire sample is ideally fully illuminated to minimize diffusion effects from the lack of stirring. If the light does not irradiate the entire sample, the beam size can be broadened using an intervening diffuser or diverging lens (Fig. 2).

Set temperature controller to room temperature or lower depending on protein stability or if studying thermal effects.

Collect kinetics data, observing at 450 nm and at the spectroscopic features of the photoreduced species (e.g., 365 nm and 403 nm for ASQ). Optimize the cycle time so that fast photoreduction events are collected and unwanted chromophore photoreduction by the probe light is minimized. Collect recovery data similarly.

Fig. 2.

Collection of photoreduction kinetics by UV-Vis spectrophotometer. A small laser diode is mounted orthogonal to the detector observation path.

For example, in the case of dCRY 10 μL of protein (~ 15 mg/mL) in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v) and 2 mM TCEP as solvent reductant is measured in quartz cuvettes with 2 mm path-length, which gives an absorbance around 0.35 at 450 nm. Kinetics of photoreduction are measured every 2 s at 365 nm, 403 nm and 450 nm under blue laser. Neutral density filters (Thorlabs) can be used to adjust the intensity of light source.

3.2. Transient absorption measurements

To observe transient spectrophotometric features, setups necessitate rapid detection speeds. For this reason, spectroscopic systems are often home-built and utilize photomultiplier tubes (PMTs), charge-coupled device (CCD) sensors, or streak cameras for detection. Pump-probe systems rely on a rapid laser excitation pulse followed by irradiation with broad-spectrum white light to collect the absorption spectrum. Time resolution is obtained by implementing a time delay between the excitation and collection events.

3.2.1. Materials

Laser capable of emitting at 450 nm (Nd:YAG; Opotek; 1–20 Hz, 5 mJ, 8 ns pulse width).

Optical table (Thorlabs).

Mirrors, lenses, neutral density filters.

Broad-spectrum arc lamp (75–300-W xenon and/or mercury source; Oriel).

Photonic multichannel analyzer (PMA; Hamamatsu).

Digital Delay/Pulse generator (DG535).

Computer with PMA interface software and Glotaran analysis program.

Cuvette (either microcuvette (0.2-cm or 1-cm path-length; Starna) or a demountable O-Shaped Circular Dichroism Cuvette; FireflySci).

Setup the system as depicted in Fig. 3 for unidirectional microcuvettes and flat circular dichroism cuvettes. The probe light is directed at a shallow angle relative to the laser excitation axis through the use of two concave mirrors with a center hole (Thorlabs). The laser travels unperturbed through the hole in the mirrors to excite the sample and the diffuse probe light is then focused on the sample along the same axis to be collected by the photonic multichannel analyzer (PMA). Alternatively, if using a fluorescence cuvette (glass or quartz on all sides), the arc lamp can be directed perpendicular to the excitation axis. The latter geometry is generally preferable to minimize stray laser light from overloading the PMA; however, this step may require greater sample volume.

Fig. 3.

Schematic of a home-built transient absorption setup. Laser light and probe lights are arranged either parallel and opposite to each other or at a shallow angle, with the focused beams crossing and overlapping at the center of the sample.

The Q-switch of the laser is used as an external trigger to synchronize the PMA and light shutters. Time delays can be implemented through the PMA software and the delay generator. As the trigger and t0 are not necessarily the same times, an initial delay needs to be set to account for instrument response time and omit any intense fluorescence/scattering signals that may overwhelm the detector. A helpful, slow-decaying sample such as zinc protoporphyrin (10−5 M anaerobic solution in 50% ethanol and 50% phosphate buffer, 10 mM, pH 7; Feitelson & Barboy, 1986) can be ideal for this purpose, as the triplet state only develops after laser excitation. Each spectrum is collected at time t0 + x, where x is the user input delay time, with a time resolution determined by the selected gate width. For every time point, a reference spectrum of the un-excited sample is collected with the probe light and averaged to improve signal-to-noise. Subsequently, a similar excitation measurement is obtained with both laser and probe light. Difference spectra are calculated as –log[data/ref]. Unfortunately, repetitive irradiation pulses without recovery time in the dark will cause samples to photobleach over time and the difference spectra to lose signal intensity and detail. As flavoproteins are particularly susceptible to bleaching, fresh samples are often exchanged in between time point collections. PMA software programs may have a pause option, which closes the physical light shutters for a period of time to allow for sample replacement.

Small cuvette volumes allow fresh samples to be manually exchanged with a micropipettor in between measurements without requiring a large quantity of sample. Some less laborious methods employ flow-cells coupled to a peristaltic pump that slowly circulates fresh sample through the excitation path to swap out photobleached sample (Bauer et al., 2011; Lewis & Kliger, 1993); however, this technique can require milliliters of concentrated protein. Other options include using a larger, mL-cuvette that can accommodate a stir bar. A pulsed stirring mechanism can then dissipate bleached protein through the rest of the non-irradiated cuvette in between measurements. Bleaching can also be reduced by adjusting the intensity of the probe light through the neutral density filter in front of the shutter (Fig. 3) and reducing the repetition frequency of the laser to 1 Hz or less to increase recovery time in between spectra acquisitions. The disadvantage of reducing the probe light intensity is a reduced signal for fast time resolution. With a 75-W Xe lamp, a time resolution of 1 μs is the minimum that can be used to detect clear, spectral detail for most samples. Despite this limitation, we can easily discern a prominent bleach of the oxidized flavoquinone and adduct formation in a VVD sample at 10 μs after laser excitation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Transient absorption spectrum of VVD (~ 400 μM) 10 μs after excitation at 450 nm, with a time resolution of 5 μs. Adduct formation is observed at 400 nm and concurs with spectra collected on LOV2 proteins (Swartz et al., 2001).

Analysis of the set of time resolved data is accomplished using a global and target analysis software (Glotaran (Snellenburg, Laptenok, Seger, Mullen, & van Stokkum, 2012)), which applies singular value decomposition (SVD) methods on time-resolved data sets in order to model the spectral components and respective concentrations. Thus, the rate of growth and decay of a particular species of interest can be monitored as a function of time. Glotaran also provides a clear graphical interface and visual modeling, which can facilitate careful inspection of fits and residuals.

4. ELECTRON PARAMAGNETIC RESONANCE SPECTROSCOPY

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), also known as electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy, and related techniques such as electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) are powerful magnetic resonance techniques to probe unpaired electrons spins, such as the semiquinone radical found in flavoproteins. Generally, in the absence of an external magnetic field the unpaired electron spin states are degenerate, whereas in the presence of a magnetic field (B0) this spin state degeneracy is removed, and the energy levels split, i.e., Zeeman splitting. This difference in energy levels between spin states directly depends on the magnetic field applied and is given by the following expression for a free electron, ΔE = hν = geβeB0, ge is the g-factor of the electron, βe is the Bohr magneton and B0 is the magnitude of the external magnetic field applied. Additionally, the presence of nuclei carrying a non-zero magnetic moment around the electron spin can lead to further splitting of the electronic spin states; this splitting due to the coupling of the nuclear to electronic spin states is referred to as the hyperfine (hf) coupling. The hf coupling constant (A) provides information about the strength of the interaction between the electron and nuclear spin, which relates to the delocalization of the electron spin over the radical (Weil, Bolton, & Wertz, 1994).

An electron with spin of ½ is split into two energy levels in the presence of a magnetic field (Fig. 5). These two electronic spin states are further split into three energy levels each due to hf coupling with a nuclear spin of 1. The differences in these spin states can be probed by irradiating the sample in the EPR spectrometer with microwave (mw) radiation, the frequencies of microwaves absorbed can reveal information about the environment of the electron spin such as the hf interactions. The linewidths of EPR peaks can also reveal information about the local dynamics and the electronic structure at the site of the electronic spin.

Fig. 5.

(A) The electron spin energy level diagram for an electron spin (S = ½) coupled to a nuclear spin (I = 1). (B) Setup of a standard EPR experiment. The main magnetic field (B0), the microwave radiation (B1), and the UV/Vis radiation are applied along the z-, y-, x-directions respectively.

Most molecules found in nature are diamagnetic and are therefore not EPR active; this is advantageous as EPR spectra have little background signal. Further, EPR can be used to study sub-micromolar spin concentrations. These low spin concentrations are particularly important when studying flavoproteins that are difficult to express and/or prone to light degradation. This sensitivity is also advantageous when only a small amount of FAD radicals are formed due to low quantum yield. Of the three redox states found of FAD, only the semiquinone state is EPR active, while the quinone and hydroquinone states are EPR silent. This makes EPR-based methods suited to study light induced changes to the redox states of FAD. Furthermore, EPR experiments are carried out using microwave radiation, and this provides two major advantages: (a) UV/ vis radiation does not affect the EPR measurements and therefore can be used to irradiate samples directly in the EPR cavity and (b) mw radiation is not scattered by cells, opening up the possibility to study the flavoproteins both in vitro as well as in vivo (Hoang et al., 2008; Yee et al., 2015). In this chapter, we will address three important EPR based methods (a) continuous wave (cw)-EPR, (b) pulsed dipolar spectroscopy (PDS), and (c) ENDOR.

4.1. Continuous-wave EPR

cw-EPR has been extensively used to probe FAD and other related flavin based radicals in a variety of systems (Hoang et al., 2008; Kay et al., 1999; Müller, Hemmerich, Ehrenberg, Palmer, & Massey, 1970; Schleicher, Bittl, & Weber, 2009; Yee et al., 2015). In cw-EPR experiments, a continuous microwave field of constant frequency is applied on the sample while the magnetic field (B0) is swept until the resonance condition is met. The cw-EPR spectrum is recorded by observing the reflected microwave radiation (see Fig. 5) as a function of the magnetic field. An amplitude modulation typically with a frequency of 100 kHz of the magnetic field is carried out to obtain better signal to noise. This additional modulation leads to the characteristic first derivative line shapes observed in cw-EPR. There are three parameters that can be readily obtained upon analysis of cw-EPR spectra: (a) field position, (b) hyperfine interactions, and (c) linewidth. The field positions can be used to calculate the g-factor values for the electron spin, which reveals the nature of the radical species formed and can be considered analogous of the chemical shift in NMR spectroscopy. In the case of flavoproteins, two kinds of EPR active FAD radicals are possible—the anion semiquinone (ASQ) or the neutral semiquinone form (NSQ). Both these FAD radical forms have a g-factor of ~ 2.003 (Fuchs et al., 2002) indicative of a semiquinone radical. Further, the hf interactions can reveal information about the localization of the electron spin on the FAD moiety. However, for FAD radicals the hyperfine (hf) interactions are relatively small (with the strongest interaction being ~ 8 G) (Barquera et al., 2003; Kay et al., 1999) and are typically hidden by the broad linewidth of these radicals. These hf couplings can however be resolved by ENDOR as discussed below. Finally, the peak-to-peak linewidth (ΔBpp, measured as the field value difference between the crest and the trough of the peak) can reveal key properties of the radical. Generally, the NSQ radicals (ΔBpp ~ 16–21 G) are broader than the ASQ radicals (ΔBpp ~ 12–16 G), due to the additional broadening provided by the extra hydrogen atom on the isoalloxazine ring of FAD. Fig. 6 shows the FAD radical formed by two flavoproteins (CRY and VVD) upon photoexcitation by blue light, as can be seen clearly the NSQ forming VVD (ΔBpp ~ 20.2 G) has broader line shapes than the ASQ forming CRY (ΔBpp ~ 14.7 G). Additional cw-EPR measurements also reveal that ASQ radical of CRY is formed instantaneously upon photoexcitation while NSQ radical in VVD forms roughly after ~ 2 m of photoexcitation (data not shown here).

Fig. 6.

The photoinduced radical formation in two flavoproteins—CRY and VVD. The experiments were carried out at ~ 9.4 GHz (X-band) at 5 °C with a modulation amplitude of 2 G.

4.2. Electron nuclear double resonance

The ENDOR technique involves simultaneously irradiating the sample with radiofrequency (rf) and microwave (mw) fields. The result is observation of the nuclear spin transitions (like NMR), but through its coupling to the electron spin, i.e., via the hf interaction. The details of the ENDOR experiment have been extensively reviewed elsewhere (Hoffman, 1991; Kulik et al., 2009; Kwiram, 1971). ENDOR is extremely sensitive to small hyperfine coupling constants that are usually broadened out in the cw-EPR and thereby allows detection of small changes to the environment around a free radical. In FAD, the strongest hf-couplings are from the nitrogen and hydrogen atoms on the isoalloxazine ring of the FAD moiety; therefore ENDOR can be used to distinguish between the NSQ and the ASQ forms of the FAD radical. Additionally, the presence of solvent molecules, as well as atoms on the protein backbone and sidechains that are coupled to the FAD radical, also contributes the ENDOR signal. ENDOR has been extensively used to study the flavin radical formed by FAD upon photooxidation in the bacterial photolyase system (Kay et al., 1999) as well as the mammalian circadian clock protein CRY (Hoang et al., 2008).

4.3. Pulsed dipolar ESR spectroscopy

Pulsed dipolar ESR spectroscopy (PDS) has become a powerful tool for the measurement of nanometer range distances in biological systems (Banham, Timmel, Abbott, Lea, & Jeschke, 2006; Borbat & Freed, 2007; Park et al., 2006; Schiemann & Prisner, 2007). This technique is analogous to fluorescence-based methods such as Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET). Currently, PDS has been used to study 1–16 nm distances in a range of biological macromolecules (e.g., membrane proteins, RNA, DNA). PDS utilizes the weak dipolar interactions between two spin probes (SA; SB) attached to a biomolecule to identify distance distributions between the biomolecules (Borbat, Costa-Filho, Earle, Moscicki, & Freed, 2001). The frequency of the coupling between the two electron spins is given by the where ħ is the reduced Planck’s constant, γe is the gyromagnetic ratio of the electronic spin, r is the distance between the dipoles. The dipolar frequency between the two spins is detected by observing the effect of flipping SB on a series of appropriately spaced spin echoes of SA. The details of the PDS experiment are beyond the scope of this review; however interested readers are pointed to the following reviews (Borbat & Freed, 2007, 2013; Casey & Fanucci, 2015; Jeschke, 2012; Misra & Freed, 2011). PDS has been used to study the distance between two flavin (ASQ) radicals in the homodimer formed by the bacterial aerotaxis protein—Aer (Samanta, Widom, Borbat, Freed, & Crane, 2016). The distance between the two flavin moieties was determined to be ~ 4.2 nm, which agrees well with homology models for this protein. PDS was also used to study the light-induced dimerization of circadian clock LOV-protein VVD from Neurospora. In VVD (Fig. 7), the distance between the flavin radicals (NSQ) was found to be ~ 37 Å, which agrees well with the prediction for the light adapted dimer (Yee et al., 2015).

Fig. 7.

(A) The structure of the light state dimer of VVD showing that the inter-flavin distance is ~ 3.7 nm. (B) The PDS distance distribution obtained for two flavin radicals on light irradiated VVD from Neurospora (Yee et al., 2015).

4.4. Transient EPR

Transient EPR (trEPR) (Bittl & Weber, 2005) is an infrequently used, but potentially impactful tool where an EPR spectrum is recorded within nanoseconds of light irradiation of samples using a pulsed laser of a defined wavelength. The EPR spectra can be recorded in either pulse or cw-EPR mode; however, pulse transient EPR has gained popularity due to its higher spectral and temporal resolution. In transient EPR, radicals formed by laser excitations will initially have non-Boltzmann population distributions; this leads to a phenomenon called chemically induced dynamic electron polarization (CIDEP). CIDEP is developed in trEPR mainly by the triplet (TM) or radical pair (RPM) mechanisms. CIDEP can manifest itself in the form of enhanced absorption (A) and/or stimulated emission (E) peaks in the EPR spectra (Van Willigen, Levstein, & Ebersole, 1993). The E/A shape of the EPR peaks depends not only on the radical formation mechanism (TM vs RPM) but also on the time between the laser pulse and the EPR measurement. Given sufficient time after the laser pulse, the developed radicals (if not decayed) will relax to the Boltzmann population states and any EPR spectra measured after this time will have steady-state EPR line shapes. Therefore, the time dependence of all the spectral parameters: frequencies, amplitudes, line widths, and phases (E/A) of all the peaks, is carried out to identify critical intermediates and the kinetics of the radical formation.

TrEPR has been applied to the study of radical propagation in flavoproteins, particularly with respect to electron transfer reactions between the flavin ring and amino acid radicals of tryptophan or tyrosine. For example, Weber et al. have shown that the electron donation to FAD in the Xenopus laevis (6–4) photolyase occurs from a tyrosine site rather than a tryptophan site as initially hypothesized (Weber et al., 2002). These measurements would not have been possible with conventional cw-EPR methods because the electron hole (formed by electron transfer from the protein sidechain to flavin moiety) would have reacted with solvent in the time scale of a cw experiment.

4.5. Some practical considerations for EPR

Typical ESR concentrations are in the range of ~ 10–50 μM of protein (~ 5 mg/mL) and usually only 20–100 μL of sample is required for obtaining spectra with a good signal to noise ratio.

The flavin radicals can be observed both in aqueous (5 °C or room temperature) and in frozen state (100 K). For samples in frozen state, it is important to have a cryoprotectant included in the buffer such as ~ 20% (w/v) of glycerol.

Both PDS and pulse ENDOR measurements are carried out in the frozen state (~ 60 K). Deuterated buffers (including deuterated glycerol, i.e., d8-glycerol) are recommended for pulse measurements as they reduce spin-spin relaxation rates allowing longer accumulation times. Deoxygenating sample buffers before use will also help with reducing spin relaxation in addition to increasing the lifetime of the flavin radical.

For cw-EPR measurements use a modulation amplitude of ~ 4 G (the recommended modulation amplitude ~ 1/3 of the peak to peak linewidth of the flavin signal).

For ENDOR measurements, there are two pulse experiments available: (a) Mims—for small hyperfine coupling constants and (b) Davies—for large hyperfine coupling constants. Strongly coupled nuclei may not be visible in a Mims experiment.

The radical lifetime is limited in aqueous solution, so measurements need to be carried out immediately after photoexcitation and/or in the presence of photoexcitation. However, if photoexcitation is carried out in the cavity, it can lead to sample heating and loss of sample tuning. Therefore, when photoexcitation is performed, it is also important to maintain the temperature in the EPR cavity using a variable temperature unit.

To carry out measurements on FAD photoexcitation in the frozen state, it is important to photo reduce the sample in aqueous state before flash freezing the sample in liquid nitrogen. The formation of the semiquinone radical is greatly reduced when the photoexcitation is performed in frozen samples.

5. MEASUREMENT OF FLAVOPROTEIN REDOX POTENTIALS

We have applied a spectroscopic method (Massey, 1991) to measure the redox potential of flavoprotein photoreceptors by equilibrating them with a reference dye that has a similar redox potential to the flavoprotein but gives an absorbance change different from that of the flavin cofactor. Below is the procedure used for Drosophila cryptochrome dCRY (Lin et al., 2018).

100 μL dCRY (4 mg/mL) was prepared in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7) with 5% glycerol and added to quartz cuvettes with 1-cm path-length (A450 ~ 0.4)

dCRY solution was equilibrated with 30 μM methyl viologen and 300 μM xanthine.

10 mM glucose, 25 μg/mL glucose oxidase, and 50 μg/mL catalase were prepared fresh and added to protein solution. The cuvette with protein solution was placed in glove box for 15 m to remove oxygen from protein solution.

The cuvette was sealed with a septum to maintain low oxygen concentration and taken out of the glove box to be measured with UV-Vis spectrum.

A syringe with a sharp needle was used to inject 100–200 nM xanthine oxidase through the septum to initiate the chemical reduction. The absorbance changes at 450 nm for FAD and 498 nm for safranin T were measured every 10 s (Fig. 8A). The change at 450 nm caused by the reduction of safranin T was calculated according to its relation with the absolute change at 498 nm (Fig. 8B and C). The slow and simultaneous reduction of dCRY and the reference dye over 1 h was achieved by adjusting the concentration of xanthine oxidase and MV.

When no major absorbance changes were observed, 5 mM sodium dithionite was added to complete the reduction.

Fig. 8.

Electrochemistry of dCRY. (A) The solution of dCRY and reference dye safranin T (E°′ = − 289 mV, pH 7 vs SHE) are reduced by xanthine/xanthine oxidase simultaneously. The absorbance at wavelength 450 and 498 nm decreases as reduction proceeds. UV/Vis spectra are shown for every 2 m over 1 h. (B) Safranin T is reduced by xanthine/ xanthine oxidase with absorbance decrease at both 450 and 498 nm. UV/Vis spectra are shown for every 2 m, and the last spectrum is completed by adding sodium dithionite. (C) Absorbance change at wavelength 450 and 498 nm is related for safranin T. (D) Nernst plot of safranin T (E°′ = − 289 mV vs SHE) vs dCRY WT.

As described (Lin et al., 2018), if the reduction is slow enough that equilibrium conditions are met, the protein redox potential can be calculated from the reference dye. The potential will be related to the standard redox potential of FADox/FAD•−, as in Eq. (1), where R is the gas constant (in J × K−1 mol−1), T is the absolute temperature (293 K during the experiment), F is the Faraday constant (in C × mol−1), n is the number of moles of electrons transferred during the reaction, E° is the standard reduction potential, Eø is the reduction potential at nonstandard conditions, and D and P indicate the dye and protein, respectively.

| (1) |

Thus,

| (2) |

where

and ΔA means the change of absorbance.

Since nD = 1 for safranin T and nP = 1 for dCRY, according to Eq. (2), 58 × log ([oxidized]/[reduced]) of safranin T is plotted as a function of 58 × log([oxidized]/[reduced]) for dCRY. The y-intercept indicates the difference of standard redox potential at pH 7 between dCRY and safranin T (Fig. 8D), and the slope 0.87 is close to 1, as expected for a one-electron process. Thus, the standard redox potential of dCRY is − 316 mV vs SHE. Note that a dye must be chosen with a potential in range of that of the protein of interest (± 60 mV), and any means of reduction (including photochemical) can be applied to drive the reaction.

6. PROTEIN CRYSTALLOGRAPHY

Protein crystallography is a mature method that has been applied with great impact to all classes of flavin-containing photoreceptors. Special considerations arise in attempts to characterize the structures of reactive states and/or photocycle intermediates. A good example is structural characterization of the light-induced adduct state of LOV proteins, which has limited lifetimes and is sensitive to photoinduced reduction, as are the other redox states of protein-bound flavins. In characterizing such states, one must first achieve a sufficient population of the light state in the crystal, and second, the state must be protected from beam damage. To accumulate the light-state, several strategies have been employed. When light-activated states are long lived, they can be crystallized (Circolone et al., 2012; Vaidya, Chen, Dunlap, Loros, & Crane, 2011). In the case of the clock protein VVD, residue substitutions were made to raise the flavin potential and thereby stabilize the cysteine-adduct (which can be considered a reduced form of the flavin ring) for days (Vaidya et al., 2011). Continual or periodic irradiation during crystallization is also effective if light states are sufficiently long-lived and quantum yields are relatively high (Crosson & Moffat, 2002; Heintz & Schlichting, 2016; Pudasaini et al., 2017). The advantage of crystallizing light states directly is that light-activation is often accompanied by large-scale conformational changes that would not be tolerated by conversion within a crystal lattice composed of the dark state (Heintz & Schlichting, 2016; Vaidya et al., 2011). Nonetheless, irradiation of crystals followed by rapid cryo-cooling can trap photocycle intermediates and coupled conformational changes that are relatively small in amplitude and local to the flavin-binding pocket (Crosson & Moffat, 2002; Fedorov et al., 2003; Möglich & Moffat, 2007; Zoltowski et al., 2007). Once formed, a high occupancy light state is sensitive to beam reduction. X-ray beams liberate secondary electrons that are mobile even at cryogenetic temperatures (Ravelli & Garman, 2006). The radiation required to generate such photoelectrons can be an order of magnitude less than what would cause noticeable deterioration of crystal diffraction (Yano et al., 2005). Radiation damage is most often mitigated by spreading a complete diffraction data set over multiple crystals, or more ideally, several positions on the same crystal (Fedorov et al., 2003; Heintz & Schlichting, 2016; Zoltowski et al., 2007). Modern, sensitive, fast-framing detectors coupled to efficient detection strategies can also limit X-ray dose (Wojdyla et al., 2018). In general, damage depends on the total radiation exposure (Murray et al., 2005; Ravelli & Garman, 2006). Procedures have been developed to predict diffraction decay, thereby minimizing damage and optimizing data collection (Bourenkov & Popov, 2010; Heintz & Schlichting, 2016; Wojdyla et al., 2018). Furthermore, extrapolation methods based on the progressive collection of redundant diffraction spots can be used to extrapolate the recorded intensities to values at time zero (Diederichs, McSweeney, & Ravelli, 2003). Advances in synchrotron-based serial crystallography (Huang et al., 2015), where thousands of microcrystals are used to compile a complete data set at room temperature, offer great promise for photosensitive and photoactivatable samples (Huang et al., 2015; Selikhanov, Fando, Dontsova, & Gabdulkhakov, 2018). Although the principles of such data collection were pioneered at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELS) in so-called “diffract and destroy” experiments (Selikhanov et al., 2018; Spence, Weierstall, & Chapman, 2012), similar procedures are now operative at third-generation synchrotron sources (Owen, Juanhuix, & Fuchs, 2016; Zander et al., 2015). These experiments offer the advantages of room-temperature data collection and minimal beam exposure, but also rely on crystal homogeneity. Finally, when possible, it is advisable to confirm the flavin redox in the crystal by use of microspectrophotometric measurements on the crystals, a capability that is available at many synchrotron beam lines (Ellis, Buffey, Hough, & Hasnain, 2008).

7. SMALL-ANGLE X-RAY SCATTERING

Small-angle X-ray scattering is a synchrotron radiation technique that provides information on molecular mass, shape, and flexibility for samples in solution at ambient temperatures (Mertens & Svergun, 2010; Putnam, Hammel, Hura, & Tainer, 2007; Skou, Gillilan, & Ando, 2014). The method is particularly useful in determining oligomeric states, characterizing conformational transitions in response to stimuli (e.g., light absorption), and testing the arrangement of domain constituents in full-length proteins and higher-order complexes (Mertens & Svergun, 2010; Putnam et al., 2007; Skou et al., 2014). For the case of photoactive proteins, SAXS provides a means to compare the overall structural changes of light vs dark states and even follow such perturbations in a time-resolved manner (Conrad, Bilwes, & Crane, 2013; Lamb, Zoltowski, Pabit, Crane, & Pollack, 2008; Lamb et al., 2009; Vaidya et al., 2013). Size-exclusion chromatography coupled to SAXS (SEC-SAXS) effectively separates complex mixtures (Skou et al., 2014), which can be extremely useful if light activation causes alterations in oligomeric state (Conrad et al., 2013; Lamb et al., 2008, 2009). In some cases, light activation only perturbs equilibria among different association states and even with SEC separation, the resulting species can be challenging to delineate (Zoltowski & Crane, 2008). Computational methods invoking evolving factor analysis show promise to deconvolute closely related components of such mixtures (Meisburger et al., 2016). Several comprehensive software packages have been developed to analyze SAXS data and extract information on molecular size, shape and flexibility (Franke et al., 2017; Hopkins, Gillilan, & Skou, 2017).

With flavin-containing photoreceptors, SAXS is often used to determine differences between light and dark states (Conrad et al., 2013; Heintz & Schlichting, 2016; Lamb et al., 2008, 2009; Purcell, McDonald, Palfey, & Crosson, 2010; Rollen, Granzin, Batra-Safferling, & Stadler, 2018; Vaidya et al., 2013). As with crystallography, photobleaching, reduction, and beam damage are considerations to heed. At the Cornell Synchrotron’s BioSAXS line, samples are typically robotically loaded into a 2-mm path-length capillary tube from a 96-well PCR plate (Conrad et al., 2013; Vaidya et al., 2013). To reduce radiation damage during SAXS data collection, the liquid sample plug is oscillated in the X-ray beam using a computer-controlled syringe pump. Six or more sequential exposures are used to assess possible radiation damage. Light samples are irradiated both before and after loading into the sample capillary, with continuous irradiation during data collection also possible. For each sample, a protein-absent buffer background image is usually acquired first, followed by an image of the photoreceptor in buffer in the “dark” state. Samples are then appropriately irradiated and images of the photoreceptor in the “light” state acquired immediately after exposure. Finally, a second buffer background image is taken. Scattering profiles for the photoreceptor can then be obtained by subtracting the scattering of the protein-absent or background profiles from the protein-present profiles. Changes in scattering between dark and light photoreceptors are often small, and thus replicate experiments with different samples are recommended.

Another advantage of SAXS is the ability to carry out time-resolved experiments. With the VVD protein, a flow cell format was used to follow its light-induced dimerization reaction (Lamb et al., 2008, 2009). A continuous flow cell made of a 1-mm polyester tube through which both an excitation laser and the probe X-ray beam are passed to allow for relatively long exposures on samples that are being continually replenished. The X-ray beam was focused with a glass capillary for better position definition. The laser focal point was then moved against the direction of fluid flow to introduce time delay. Time delays are limited by beam size, positioning, and flow rate, which can all be altered to produce different intervals. In the case of VVD, time delays in the range of 20 ms to 10 s were recorded (Lamb et al., 2008, 2009). Importantly, a PIN diode mounted onto the X-ray beam-stop measures beam intensity so that the diffraction patterns can be normalized for beam fluctuations. More recent advances in beam-line technology have extended time-resolved SAXS on photoreceptors to the microsecond timescale (Cho et al., 2010; Takala et al., 2014).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The EPR measurements for this manuscript were collected at ACERT (Cornell University) supported by the NIH/NIGMS Grant P41GM103521. This work supported by NSF grant MCB 1715233 and NIH grant to R35GM066775 B.R.C.

REFERENCES

- Alexandre MTA, Arents JC, Van Grondelle R, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JTM, 2007. A base-catalyzed mechanism for dark state recovery in the Avena sativa phototropin-1 LOV2 domain. Biochemistry 46 (11), 3129–3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S, Dragnea V, Masuda S, Ybe J, Moffat K, Bauer C, 2005. Structure of a novel photoreceptor, the BLUF domain of AppA from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry 44 (22), 7998–8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banham JE, Timmel CR, Abbott RJM, Lea SM, Jeschke G, 2006. The characterization of weak protein-protein interactions: Evidence from DEER for the trimerization of a von Willebrand factor A domain in solution. Angewandte Chemie—International Edition 45 (7), 1058–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barquera B, Morgan JE, Lukoyanov D, Scholes CP, Gennis RB, Nilges MJ, 2003. X- and W-band EPR and Q-band ENDOR studies of the flavin radical in the Na +-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase from Vibrio cholerae. Journal of the American Chemical Society 125 (1), 265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer C, Rabl CR, Heberle J, Kottke T, 2011. Indication for a radical intermediate preceding the signaling state in the LOV domain photocycle. Photochemistry and Photobiology 87 (3), 548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DF, Zhu W, Moxley MA, 2011. Flavin redox switching of protein functions. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling 14 (6), 1079–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskup T, Schleicher E, Okafuji A, Link G, Hitomi K, Getzoff ED, et al. , 2009. Direct observation of a photoinduced radical pair in a cryptochrome blue-light photoreceptor. Angewandte Chemie—International Edition 48 (2), 404–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittl R, Weber S, 2005. Transient radical pairs studied by time-resolved EPR. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Bioenergetics 1707 (1), 117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti C, Mathes T, Van Stokkum IHM, Mullen KM, Groot ML, Van Grondelle R, et al. , 2008. Hydrogen bond switching among flavin and amino acid side chains in the BLUF photoreceptor observed by ultrafast infrared spectroscopy. Biophysical Journal 95 (10), 4790–4802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbat PP, Costa-Filho AJ, Earle KA, Moscicki JK, Freed JH, 2001. Electron spin resonance in studies of membranes and proteins. Science 291 (5502), 266–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbat PP, Freed JH, 2007. Measuring distances by pulsed dipolar ESR spectroscopy: Spin-labeled histidine kinases. Methods in Enzymology 423, 52–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbat PP, Freed JH, 2013. Pulse dipolar electron spin resonance: Distance measurements In: Timmel CR, Harmer JR (Eds.), Structure and bonding. Vol. 152, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bourenkov GP, Popov AN, 2010. Optimization of data collection taking radiation damage into account. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography 66, 409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cafaro V, Scognamiglio R, Viggiani A, Izzo V, Passaro I, Notomista E, et al. , 2002. Expression and purification of the recombinant subunits of toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase and reconstitution of the active complex. European Journal of Biochemistry 269 (22), 5689–5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey TM, Fanucci GE, 2015. Spin labeling and double electron-electron resonance (DEER) to deconstruct conformational ensembles of HIV protease In: Methods in enzymology. Vol. 564, Academic Press, London,; San Diego, CA; Waltham, MA; Kidlington, Oxford, pp. 153–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashmore AR, 2003. Cryptochromes: Enabling plants and animals to determine circadian time. Cell 114 (5), 537–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashmore AR, Jarillo JA, Wu Y-J, Liu D, 1999. Cryptochromes: Blue-light receptors for plants and animals. Science 284 (5415), 760–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-H, DeMay BS, Gladfelter AS, Dunlap JC, Loros JJ, 2010. Physical interaction between VIVID and white collar complex regulates photoadaptation in Neurospora. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (38), 16715–16720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HS, Dashdorj N, Schotte F, Graber T, Henning R, Anfinrud P, 2010. Protein structural dynamics in solution unveiled via 100-ps time-resolved x-ray scattering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (16), 7281–7286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Blackwood L, Petersen J, Sullivan S, 2015. Plant flavoprotein photoreceptors. Plant and Cell Physiology 56 (3), 401–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Reymond P, Powell GK, Bernasconi P, Raibekas AA, Liscum E, et al. , 1998. Arabidopsis NPH1: A flavoprotein with the properties of a photoreceptor for phototropism. Science 282 (5394), 1698–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie JM, Swartz TE, Bogomolni RA, Briggs WR, 2002. Phototropin LOV domains exhibit distinct roles in regulating photoreceptor function. The Plant Journal 32 (2), 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Circolone F, Granzin J, Jentzsch K, Drepper T, Jaeger KE, Willbold D, et al. , 2012. Structural basis for the slow dark recovery of a full-length LOV protein from Pseudomonas putida. Journal of Molecular Biology 417 (4), 362–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KS, Bilwes AM, Crane BR, 2013. Light-induced subunit dissociation by a light-oxygen-voltage domain photoreceptor from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry 52, 378–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KS, Manahan CC, Crane BR, 2014. Photochemistry of flavoprotein light sensors. Nature Chemical Biology 10 (10), 801–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane BR, Young MW, 2014. Interactive features of proteins composing eukaryotic circadian clocks. Annual Review of Biochemistry 83 (1), 191–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosson S, Moffat K, 2002. Photoexcited structure of a plant photoreceptor domain reveals a light-driven molecular switch. Plant Cell 14, 1067–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosson S, Rajagopal S, Moffat K, 2003. The LOV domain family: Photoresponsive signaling modules coupled to diverse output domains. Biochemistry 42 (1), 2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederichs K, McSweeney S, Ravelli RBG, 2003. Zero-dose extrapolation as part of macromolecular synchrotron data reduction. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography 59, 903–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domratcheva T, Grigorenko BL, Schlichting I, Nemukhin AV, 2008. Molecular models predict light-induced glutamine tautomerization in BLUF photoreceptors. Biophysical Journal 94 (10), 3872–3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragnea V, Waegele M, Balascuta S, Bauer C, Dragnea B, 2005. Time-resolved spectroscopic studies of the AppA blue-light receptor BLUF domain from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry 44 (49), 15978–15985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis MJ, Buffey SG, Hough MA, Hasnain SS, 2008. On-line optical and X-ray spectroscopies with crystallography: An integrated approach for determining metallo-protein structures in functionally well defined states. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 15, 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov R, Schlichting I, Hartmann E, Domratcheva T, Fuhrmann M, Hegemann P, 2003. Crystal structures and molecular mechanism of a light induced signaling switch: The Phot-LOV1 domain from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biophysical Journal 84 (4), 2474–2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feitelson J, Barboy N, 1986. Triplet-state reactions of zinc protoporphyrins. Journal of Physical Chemistry 90 (2), 271–274. [Google Scholar]

- Foley LE, Gegear RJ, Reppert SM, 2011. Human cryptochrome exhibits light-dependent magnetosensitivity. Nature Communications 2, 356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke D, Petoukhov MV, Konarev PV, Panjkovich A, Tuukkanen A, Mertens HDT, et al. , 2017. ATSAS 2.8: A comprehensive data analysis suite for small-angle scattering from macromolecular solutions. Journal of Applied Crystallography 50, 1212–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisell WR, Chung CW, Mackenzie CG, 1958. Catalysis of oxidation coenzymes of nitrogen compounds in the presence of light. Journal of Biological Chemistry 234 (5), 1297–1302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs MR, Schleicher E, Schnegg A, Kay CWM, Törring JT, Bittl R, et al. , 2002. G-tensor of the neutral flavin radical cofactor of DNA photolyase revealed by 360-GHz electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 106 (34), 8885–8890. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly A, Manahan CC, Top D, Yee EF, Lin C, Young MW, et al. , 2016. Changes in active site histidine hydrogen bonding trigger cryptochrome activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113 (36), 10073–10078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly A, Thiel W, Crane BR, 2017. Glutamine amide flip elicits long distance allosteric responses in the LOV protein vivid. Journal of the American Chemical Society 139 (8), 2972–2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauden M, van Stokkum IH, Key JM, Luhrs DC, van Grondelle R, Hegemann P, et al. , 2006. Hydrogen-bond switching through a radical pair mechanism in a flavin-binding photoreceptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (29), 10895–10900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegear RJ, Foley LE, Casselman A, Reppert SM, 2010. Animal cryptochromes mediate magnetoreception by an unconventional photochemical mechanism. Nature 463 (7282), 804–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomelsky M, Klug G, 2002. BLUF: A novel FAD-binding domain involved in sensory transduction in microorganisms. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 27 (10), 497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinstead JS, Hsu STD, Laan W, Bonvin AMJJ, Hellingwerf KJ, Boelens R, et al. , 2006. The solution structure of the AppA BLUF domain: Insight into the mechanism of light-induced signaling. Chembiochem 7 (1), 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa K, Masuda S, Ono TA, 2005. Spectroscopic analysis of the dark relaxation process of a photocycle in a sensor of blue light using FAD (BLUF) protein Slr1694 of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Plant and Cell Physiology 46 (1), 136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefti MH, Vervoort J, Van Berkel WJH, 2003. Deflavination and reconstitution of flavoproteins: Tackling fold and function. European Journal of Biochemistry 270 (21), 4227–4242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintz U, Schlichting I, 2016. Blue light-induced LOV domain dimerization enhances the affinity of Aureochrome 1a for its target DNA sequence. eLife 5, e11860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hense A, Herman E, Oldemeyer S, Kottke T, 2015. Proton transfer to flavin stabilizes the signaling state of the blue light receptor plant cryptochrome. Journal of Biological Chemistry 290 (3), 1743–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrou J, Crosson S, 2011. Function, structure and mechanism of bacterial photosensory LOV proteins. Nature Reviews Microbiology 9 (10), 713–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang N, Schleicher E, Kacprzak S, Bouly JP, Picot M, Wu W, et al. , 2008. Human and Drosophila cryptochromes are light activated by flavin photoreduction in living cells. PLoS Biology 6 (7), 1559–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BM, 1991. Electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) of metalloenzymes. Accounts of Chemical Research 24 (6), 164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins JB, Gillilan RE, Skou S, 2017. BioXTAS RAW: Improvements to a free open-source program for small-angle X-ray scattering data reduction and analysis. Journal of Applied Crystallography 50, 1545–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Olieric V, Ma PK, Panepucci E, Diederichs K, Wang MT, et al. , 2015. In meso in situ serial X-ray crystallography of soluble and membrane proteins. Acta Crystallographica Section D, Structural Biology 71, 1238–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt SM, Thompson S, Elvin M, Heintzen C, 2010. VIVID interacts with the WHITE COLLAR complex and FREQUENCY-interacting RNA helicase to alter light and clock responses in Neurospora. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (38), 16709–16714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata T, Zhang Y, Hitomi K, Getzoff ED, Kandori H, 2010. Key dynamics of conserved asparagine in a cryptochrome/photolyase family protein by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry 49 (41), 8882–8891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke G, 2012. DEER distance measurements on proteins. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 63 (1), 419–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MA, Feeney KA, Kelly SM, Christie JM, 2007. Mutational analysis of phototropin 1 provides insights into the mechanism underlying LOV2 signal transmission. Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 (9), 6405–6414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung A, Domratcheva T, Tarutina M, Wu Q, Ko W-H, Shoeman RL, et al. , 2005. Structure of a bacterial BLUF photoreceptor: Insights into blue light-mediated signal transduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (35), 12350–12355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung A, Reinstein J, Domratcheva T, Shoeman RL, Schlichting I, 2006. Crystal structures of the AppA BLUF domain photoreceptor provide insights into blue light-mediated signal transduction. Journal of Molecular Biology 362 (4), 717–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa T, Ren S, Maekawa M, Hasegawa K, Arisaka F, Hyodo M, et al. , 2010. Biochemical and physiological characterization of a BLUF protein-EAL protein complex involved in blue light-dependent degradation of cyclic diguanylate in the purple bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Biochemistry 49 (50), 10647–10655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao Y-T, Saxena C, Wang L, Sancar A, Zhong D, 2005. Direct observation of thymine dimer repair in DNA by photolyase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (45), 16128–16132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay CWM, Feicht R, Schulz K, Sadewater P, Sancar A, Bacher A, et al. , 1999. EPR, ENDOR, and TRIPLE resonance spectroscopy on the neutral flavin radical in Escherichia coli DNA photolyase. Biochemistry 38 (51), 16740–16748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennis JTM, Groot ML, 2007. Ultrafast spectroscopy of biological photoreceptors. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 17 (5), 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottke T, Batschauer A, Ahmad M, Heberle J, 2006. Blue-light-induced changes in Arabidopsis cryptochrome 1 probed by FTIR difference spectroscopy. Biochemistry 45 (8), 2472–2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss U, Minh BQ, Losi A, Gärtner W, Eggert T, Von Haeseler A, et al. , 2009. Distribution and phylogeny of light-oxygen-voltage-blue-light-signaling proteins in the three kingdoms of life. Journal of Bacteriology 191 (23), 7234–7242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulik LV, Rapatsky LL, Pivtsov AV, Surovtsev NV, Adichtchev SV, Grigor’ev IA, et al. , 2009. Electron-nuclear double resonance study of molecular librations of nitroxides in molecular glasses: Quantum effects at low temperatures, comparison with low-frequency Raman scattering. The Journal of Chemical Physics 131 (6), 064505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutta RJ, Magerl K, Kensy U, Dick B, 2015. A search for radical intermediates in the photocycle of LOV domains. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences 14 (2), 288–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiram AL, 1971. Electron nuclear double resonance. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 22 (1), 133–170. [Google Scholar]

- Laan W, Gauden M, Yeremenko S, Van Grondelle R, Kennis JTM, Hellingwerf KJ, 2006. On the mechanism of activation of the BLUF domain of AppA. Biochemistry 45 (1), 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb JS, Zoltowski BD, Pabit SA, Crane BR, Pollack L, 2008. Time-resolved dimerization of a PAS-LOV protein measured with photocoupled small angle X-ray scattering. Journal of the American Chemical Society 130 (37), 12226–12227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb JS, Zoltowski BD, Pabit SA, Li L, Crane BR, Pollack L, 2009. Illuminating solution responses of a LOV domain protein with photocoupled small-angle X-ray scattering. Journal of Molecular Biology 393 (4), 909–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leartsakulpanich U, Antonkine ML, Ferry JG, 2000. Site-specific mutational analysis of a novel cysteine motif proposed to ligate the 4Fe-4s cluster in the iron-sulfur flavoprotein of the thermophilic methanoarchaeon Methanosarcina thermophila. Journal of Bacteriology 182 (19), 5309–5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JW, Kliger DS, 1993. Microliter flow cell for measurement of irreversible optical absorbance transients. Review of Scientific Instruments 64 (10), 2828–2833. [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Wang LJ, Zhong DP, 2013. Ultrafast dynamics of flavins and flavoproteins In: Hille R, Miller S, Palfey B (Eds.), Handbook of flavoproteins: Complex flavoproteins, dehydrogenases and physical methods. Vol. 2, De Gruyter, Berlin, pp. 393–428. [Google Scholar]

- Liedvogel M, Mouritsen H, 2010. Cryptochromes—A potential magnetoreceptor: What do we know and what do we want to know?. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 7 (Suppl. 2), S147–S162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Todo T, 2005. The cryptochromes. Genome Biology 6 (5), 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]