ABSTRACT

Ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) promotes homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DNA double-strand break repair. It was recently shown that the proteasomal shuttle factor UBQLN4 facilitates MRE11 degradation to repress HR. Surprisingly, the UBQLN4-MRE11 interaction is ATM-dependent, suggesting that the proximal DNA damage kinase ATM does not only initiate HR, but also limits excessive end resection.

KEYWORDS: DSB repair pathway choice, DNA end resection, HR, NHEJ, ATM, UBQLN4

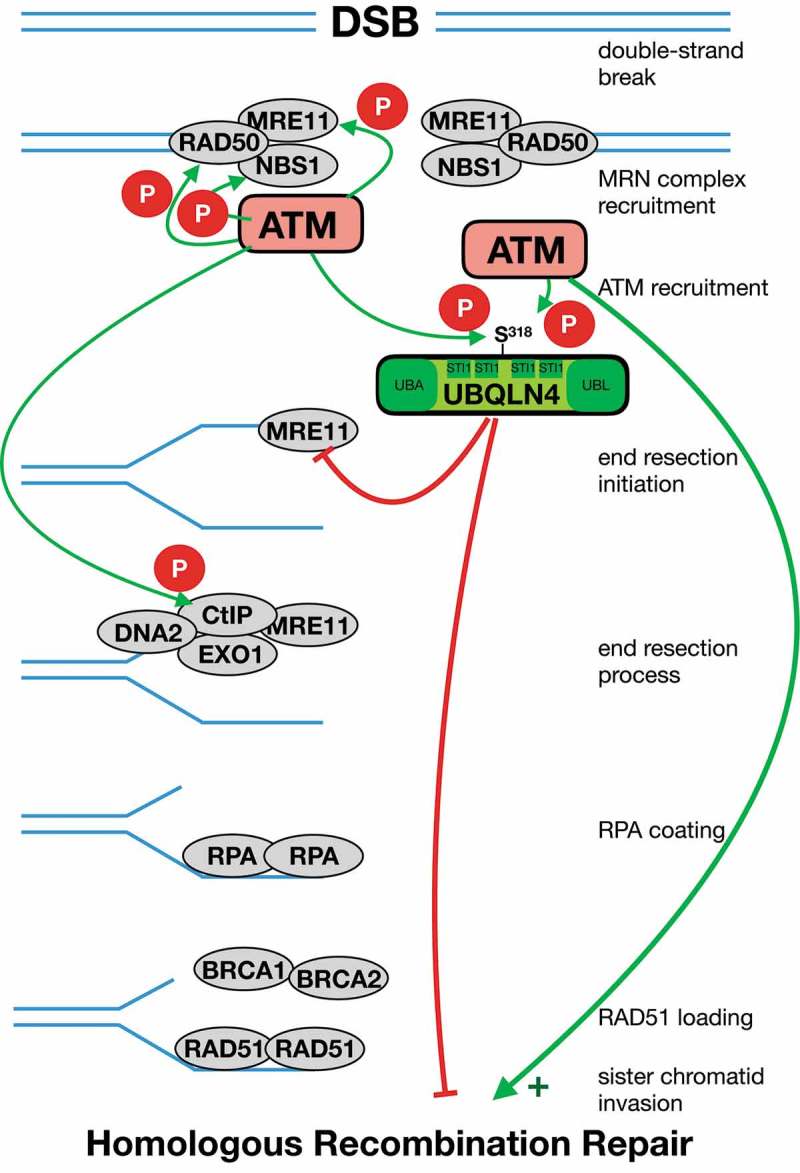

Accurate repair of DNA lesions is critical for all organisms. In response to genotoxic stress, the DNA damage response (DDR) activates cell cycle checkpoints, DNA repair pathways, and, if the damage is beyond repair capacity, triggers cell death pathways.1 DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) are potent activators of the DDR that require timely and accurate repair.2 Mammalian cells employ two main DSB repair pathways – the canonical non-homologous end-joining (cNHEJ) pathway and homologous recombination repair (HR). A fine-tuned balance between HR and cNHEJ is essential for correct DSB repair3 and imbalances between these two pathways, as for instance observed in HR-defective tumors, lead to a synthetic lethal toxicity with Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase 1 (PARP1) inhibitors.4 Error-prone cNHEJ operates throughout the cell cycle and directly ligates the processed DSB ends, whereas error-free HR is restricted to late S- and G2, when a replicated sister chromatid is available as a repair template.3 HR involves binding of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex to tether DSB ends and to recruit and activate the proximal DDR kinase ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) (Figure 1).2 ATM phosphorylates a plethora of substrates, such as CHK2, p53 (TP53), MDC1 and MRN complex components.2 Particularly, ATM-dependent phosphorylation of NBS1, RAD50 and MRE11 and downstream components of DNA end resection, such as CtIP contributes to the activation of HR and may also create a positive feedback loop that maintains ATM activity (Figure 1).2 The initiation process of the DNA end resection machinery is important, as it licenses DSB ends for the ability to perform HR. The nuclease MRE11 initiates a 5ʹ-3ʹ DSB end resection and thus places MRE11 at the heart of the cellular decision between HR and cNHEJ.5

Figure 1.

Homologous recombination (HR) is activated and auto-inhibited by ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM). ATM is recruited by the MRN (MRE11, RAD50, NBS1) complex and ATM thus promotes HR by activating phosphorylations. The initial step of the HR process creates a single-stranded 3′-DNA (ssDNA) overhang, which is subsequently coated by the ssDNA binding protein RPA and then replaced by RAD51 in an ATM/CHK2/BRCA1/BRCA2/PALB2-dependent fashion. The critical end resection step is mediated by a series of endo- and exonucleases, including MRE11, EXO1, and DNA2. MRE11 plays a key role in DNA end resection, specifically by promoting the initiation of the resection process, rather than driving resection processivity. ATM-dependent S318/UBQLN4 phosphorylation drives the proteasomal degradation of MRE11 thus limiting HR. Abbreviations: Ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain; heat shock chaperonin-binding (STI1) motif; Ubiquitin-like (UBL) domain.

Recently, we described a novel genome instability syndrome termed UBQLN4 deficiency syndrome, as the clinical correlate of a homozygous c.976C > T nonsense-mutation of the UBQLN4 gene. This mutation leads to loss of UBQLN4 protein in affected patients.6 We found that the proteasomal shuttle factor UBQLN4 binds to ubiquitylated MRE11 via its Ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain and promotes its degradation, thus limiting the initiation of DNA end resection.6 In affected patients, as well as in C. elegans ubql-1 mutants, the nematode ortholog of UBQLN4, we observed an increase of HR usage, fully in line with a functional defect of UBQLN4-mediated MRE11 turnover.6 In healthy individuals, overt accumulation of ubiquitylated MRE11 on damaged chromatin is prevented by UBQLN4. Intriguingly, the interaction of MRE11 and UBQLN4 is regulated by ATM. Within UBQLN4, we found a highly conserved S-S-Q-P amino acid sequence that contains the potential ATM substrate motif, S318-Q.1,6 DNA damage- and ATM-dependent phosphorylation of S318/UBQLN4 was mandatory for the interaction of UBQLN4 with MRE11 (Figure 1).6 S318/UBQLN4 is located between the second and third heat shock chaperonin-binding (STI1) motif, which are important for forming oligomers and in the recognition of substrates, such as heat shock proteins.7 Indeed, we observed that endogenous UBQLN4 forms homo-dimers or -polymers.6 It is intriguing to hypothesize that ATM-dependent S318/UBQLN4 phosphorylation relieves auto-inhibition and potentially exposes the UBQLN4 UBA domain to bind ubiquitylated MRE11, potentially also allowing an interaction with one of the ST1 domains. ATM plays an important role in initiating HR,2 thus the observation that UBQLN4 promotes MRE11 turnover at damaged chromatin in an ATM-dependent fashion is interesting, as it potentially suggests a negative feedback loop, in which ATM also limits HR activity through UBQLN4-mediated MRE11 removal from the break site.6 Previous studies have primarily highlighted positive feedback loops by ATM auto-phosphorylation on multiple sites, such as S1981, S367, S2996 and others, resulting in a retention of activated ATM at DSBs (also summarized in2). ATM is further activated through dephosphorylation events mediated by protein phosphatases, such as PP2A44 and PP5.2 Recent work has elucidated that ATM deficiency does not prevent DNA end resection but instead delays its kinetics.8 Utilizing immunofluorescence studies specifically looking at RPA foci formation, which serves as a marker for DNA end resection, Atm deficient cells displayed reduced intensity of RPA foci 1 h after continuous topotecan treatment.8 Moreover, after withdrawal of topotecan, RPA-focus intensity increased in Atm deficient cells, while RPA focus intensity decreased after topotecan withdrawal in wild-type cells, most likely due to replacement of RPA by RAD51 and ensuing HRR.8 But ATM function in regard to HR activity is not limited to promoting DNA end resection. Instead, it was suggested that ATM promotes HR also downstream of DNA end resection.9 This was particularly obvious when ATM was inhibited after the completion of MRE11-dependent DNA end resection in HeLa cells carrying a pDSRed-ISceI-GR reporter plasmid, which resulted in a reduction of HR efficiency by more than 50%.9 While DDR processes frequently share multiple modes of regulation (activating or inhibiting) at various points in their pathways, evidence suggests that HR is primarily inhibited by competing DNA repair pathways, such as cNHEJ. One such example is the nuclease Artemis, which prevents end resection and promotes cNHEJ and therefore directly competes with HR.10 The finding that UBQLN4 is part of an ATM-dependent negative feedback loop underscores the possibility of further auto-regulation events within the HR pathway that might be amenable for therapeutic exploitation.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the German-Israeli Foundation for Research and Development (I-65-412.20-2016 to HCR), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KFO-286-RP2/CP1 to HCR and JA2439/1-1 to RDJ), the Else Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung (2014-A06 to HCR, 2016_Kolleg.19 to RDJ), the Deutsche Krebshilfe (1117240 to HCR), the Hilde-Kopp Stiftung (to RDJ), Stiftung Kölner Krebsforschung (to RDJ) and the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF e:Med 01ZX1303A to HCR).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Competing interests

HCR received consulting and lecture fees (AstraZeneca, Merck, Celgene, Vertex). HCR received research funding from Gilead Pharmaceuticals. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Reinhardt HC, Yaffe MB.. Phospho-Ser/Thr-binding domains: navigating the cell cycle and DNA damage response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:563–580. doi: 10.1038/nrm3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiloh Y, Ziv Y.. The ATM protein kinase: regulating the cellular response to genotoxic stress, and more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:197–210. doi: 10.1038/nrm3546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dietlein F, Thelen L, Reinhardt HC. Cancer-specific defects in DNA repair pathways as targets for personalized therapeutic approaches. Trends Genet. 2014;30:326–339. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt ANJ, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nimonkar AV, Genschel J, Kinoshita E, Polaczek P, Campbell JL, Wyman C, Modrich P, Kowalczykowski SC. BLM-DNA2-RPA-MRN and EXO1-BLM-RPA-MRN constitute two DNA end resection machineries for human DNA break repair. Genes Dev. 2011;25:350–362. doi: 10.1101/gad.2003811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jachimowicz RD, Beleggia F, Isensee J, Velpula BB, Goergens J, Bustos MA, Doll MA, Shenoy A, Checa-Rodriguez C, Wiederstein JL, et al. UBQLN4 represses homologous recombination and is overexpressed in aggressive tumors. Cell. 2019;176:505–519 e522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flom G, Behal RH, Rosen L, Cole DG, Johnson JL. Definition of the minimal fragments of Sti1 required for dimerization, interaction with Hsp70 and Hsp90 and in vivo functions. Biochem J. 2007;404:159–167. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balmus G, Pilger D, Coates J, Demir M, Sczaniecka-Clift M, Barros AC, Woods M, Fu B, Yang F, Chen E, et al. ATM orchestrates the DNA-damage response to counter toxic non-homologous end-joining at broken replication forks. Nat Commun. 2019;10:87. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakr A, Oing C, Köcher S, Borgmann K, Dornreiter I, Petersen C, Dikomey E, Mansour WY. Involvement of ATM in homologous recombination after end resection and RAD51 nucleofilament formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:3154–3166. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Aroumougame A, Lobrich M, Li Y, Chen D, Chen J, Gong Z. PTIP associates with Artemis to dictate DNA repair pathway choice. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2693–2698. doi: 10.1101/gad.252478.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]