Abstract

Stakeholder participation is now widely viewed as an essential component of environmental management projects, but limited research investigates how practitioners perceive the major challenges and strategies for implementing high-quality participation. In order to address this gap, we present findings from a survey and interviews conducted with managers and advisory committee leaders in a case study of United States and binational (US and Canada) Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Our findings suggest that recruiting and integrating participants and sustaining participation over the long term present distinctive ongoing challenges that are not fully recognized in existing conceptualizations of the process of implementing participation. For example, it can be difficult to recruit active stakeholders to fill vacant “slots,” to integrate distinctive interests and perspectives in decision-making processes, and to keep participants involved when activity is low and less visible. We present strategies that emerged in the survey and interviews for addressing these challenges, emphasizing the building and leveraging of relationships among stakeholders themselves. Such strategies include balancing tight networks with an openness to new members, supplementing formal hearings with social gatherings, making participation socially meaningful, and dividing labor between managers and advisory committees.

Keywords: Stakeholder participation, environmental project, Great Lakes, Area of Concern, relationship-building, engagement process

1. Introduction

Stakeholder participation has become widely accepted as an essential component of environmental management projects. The idea is now commonplace that decision-making can benefit from the participation of both technical experts and ordinary citizens. Fiorino (1990) categorized the benefits of citizen participation as substantive (bringing distinctive and valuable knowledge into the project), normative (honoring democratic rights), and instrumental (making decisions more legitimate and effective). Research suggests that effective participatory processes can generate improved decisions and other beneficial outcomes, including learning, increased trust, and reduced conflict (e.g., Beierle and Konisky, 2001; Danielson, 2016; Reed, 2008; Sterling et al., 2017). However, successful participation depends on both the design of the process and several contextual factors (e.g., Baker and Chapin 2018; de Vente et al., 2016; Reed et al., 2018; Sterling et al., 2017). In some cases, the difficulty of realizing these benefits and the risks of generating negative outcomes have generated disillusionment about participation (e.g., Moon et al., 2017; Staddon et al., 2015).

Consequently, a key question for environmental management is how to design and implement stakeholder participation processes of high quality. A growing literature addresses dimensions of these processes, including identifying and characterizing stakeholders (e.g., Colvin et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 1997), structuring levels and degrees of participation (e.g., Davidson 1998; Reed et al., 2018), implementing participatory techniques (e.g., Van Asselt et al., 2001), and evaluating participatory processes (e.g., Rowe and Frewer, 2000; Luyet et al., 2012). However, as Mease et al. (2018, p. 149) point out, little research focuses on “the experiences, perceptions, and stated needs of practitioners themselves”: that is, those who coordinate, manage, and implement participation in practice. We contend that the perspectives of these practitioners help build not only deeper understanding of practical obstacles to realizing the benefits of participation, but also richer conceptualizations of stakeholder participation as a process. This study addresses this gap with the following research question: how do practitioners perceive their biggest challenges for implementing high-quality stakeholder participation and the most effective strategies for overcoming these challenges?

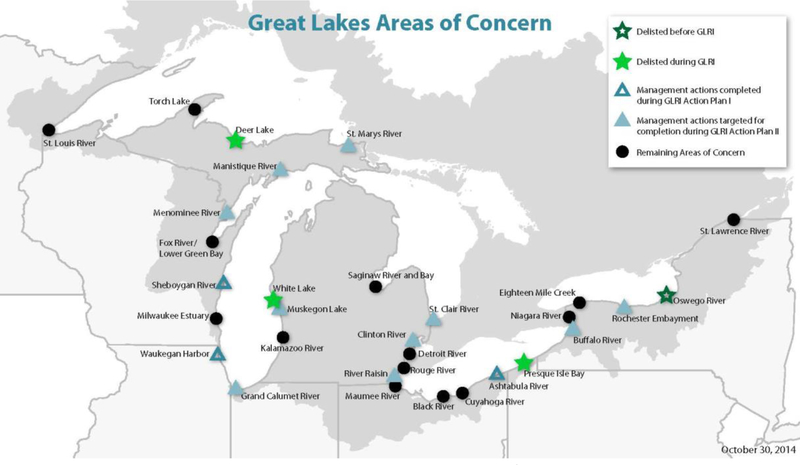

In order to investigate this question, we analyze surveys and interviews conducted with a sample of managers and citizen advisory committee leaders in a case study of the Great Lakes Areas of Concern program. This program, which originated as an annex to a 1987 Protocol that amended the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement of 19781 between the US and Canada, designated 43 “severely degraded geographic areas” as Areas of Concern (AOCs) (International Joint Commission, 2018). At each AOC, the objective is to develop a Remedial Action Plan (RAP) to have the area delisted, based on eliminating adverse impacts known as beneficial use impairments, or BUIs (International Joint Commission, 2018). The most recent version of the Agreement directs the two countries to develop these plans “in cooperation and consultation with State and Provincial Governments, Tribal Governments, First Nations, Métis, Municipal Governments, watershed management agencies, other local public agencies, and the Public,” and stakeholder participation is a central tenet in their implementation (GLWQA 2012, p. 22). In the US, the program is implemented at each AOC by a state agency in cooperation with a public advisory body. As of 2018, four US AOCs and three Canadian AOCs have been delisted, so in both countries most AOCs remain active.

Although the Areas of Concern program is in many ways unique, the diversity of sites in the program and its distinctive, longstanding emphasis on participation make it an important case for research. Each AOC encompasses a unique mix of biophysical attributes, agency priorities, and public support, but all include attempts to implement a similar process of remediation and restoration. In addition, the creation and implementation of RAPs represent a departure from traditional regulatory approaches, by making public consultation integral to environmental improvement (Jetoo et al., 2015; Muldoon, 2012). The Great Lakes community of resource managers, scholars, and activists considers the RAPs to be a long-running experiment in participatory governance (Muldoon, 2012; Williams, 2015). Numerous other studies have examined dimensions of stakeholder or public involvement in Great Lakes AOCs (e.g., Beierle and Konisky, 2001; Grover and Krantzberg, 2012; Hartig and Law, 1994; Hartig et al., 1998; Krantzberg, 2003; Krantzberg et al., 2015; Landre and Knuth, 1993a, 1993b; MacKenzie, 1993, 1996; Sproule-Jones, 2002). However, most of these studies are over fifteen years old—activity on the US side of the border has increased substantially since the passage of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI)2 in 2010. Finally, changes in funding and agency support over time have resulted in uneven implementation (Jetoo et al., 2015).

Through this Great Lakes case study, our primary objectives are to develop an expanded conceptual model of the process of stakeholder participation and, using this model, to contribute to the development of key principles and strategies for implementing high-quality participation. We begin by introducing the conceptual framework that we propose to expand—distinctive in that it divides the implementation of stakeholder participation into discrete components (Luyet et al., 2012)—and the most relevant recent research on principles and strategies of stakeholder participation. After describing our methodology, we present our major findings, suggesting that the key challenges and strategies perceived by practitioners pertained to three major components of implementation: recruiting active stakeholders, integrating them into decision-making processes, and sustaining their long-term participation. We conclude by proposing an expansion and modification of the Luyet et al. (2012) model, comparing and contrasting our results with pertinent recent findings, and suggesting topics for future research. Among these topics, we call for special attention to social relationships among stakeholders, which emerged in our case study as significant to all stages of implementation. Despite the uniqueness of the Areas of Concern program, we suggest that the expanded model and best practices are applicable in a wide variety of environmental management situations.

2. Conceptualizing the implementation of stakeholder participation

In order to characterize key challenges and strategies for implementing high-quality stakeholder participation, it is useful to disaggregate the multiple components that together make up the participation process. While other frameworks emphasize types and levels of participation and their relationships with decisions and outcomes (see Reed, 2008), Luyet et al. (2012) introduce a distinctive and useful model representing the main stages in the practical implementation of participation.

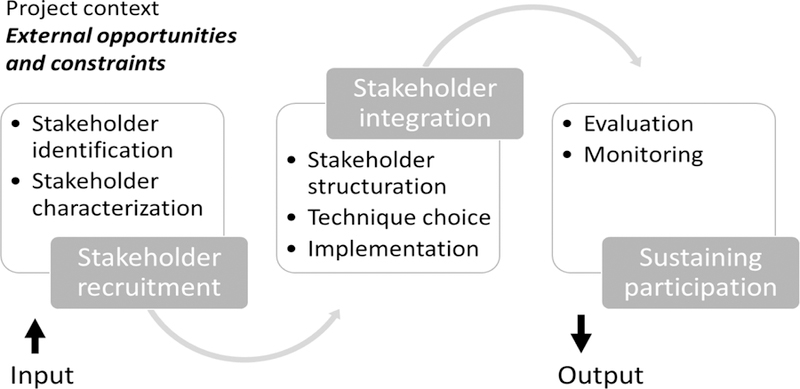

Luyet et al. (2012, p. 214) conceptualize stakeholder participation—distinguished from more general “public participation” by its emphasis on distinctive stakeholder groups—as a “system with inputs (e.g. environmental policy), outputs (decisions) and processes.” In their framework, six processes constitute the major components: stakeholder identification, stakeholder characterization, stakeholder structuration, choice of participatory techniques, implementation of participatory techniques, and evaluation. Stakeholder analysis, geared toward identifying and characterizing appropriate stakeholders, has become a well-established field (e.g., Colvin et al., 2016; Reed et al., 2009). As Luyet et al. (2012, p. 215) describe it, the task of structuration is “to structure the identified stakeholders into homogeneous groups and to give each group a specific degree of involvement.” Arnstein’s (1969) well-known “ladder of participation” provides the classic model for specifying degrees of involvement; however, recent scholarship suggests replacing the ladder metaphor with a “wheel,” which involves a more complex relationship between levels of involvement and the structure in which participation takes place (Davidson, 1998; Mease et al., 2018; Reed et al., 2018). Once managers have integrated stakeholders into a project, their next steps are to determine and implement appropriate participatory techniques, which includes devising methods and forums for communication and interaction (Rowe and Frewer, 2000). Finally, managers evaluate the process in order to inform and improve the implementation of stakeholder participation in subsequent projects.

Each of these processes brings different challenges and different strategies for overcoming them. Among the most common challenges associated with stakeholder identification, for example, is the need to include and accommodate under-represented groups and addressing inequities (Butler and Adamowski, 2015; Mease et al., 2018). Managers have come to recognize that the range of interests and constituencies represented within a stakeholder group makes a difference for how the process works (Butler and Adamowski, 2015; Glicken, 2000; Mitchell et al., 1997). Stakeholder characterization may also involve the difficult task of characterizing the barriers to participation that these groups face, along with the political conflicts and power differences that may condition their participation (Luyet et al., 2012). In some contexts, such power relations may render a more inclusive, “bottom-up” structure to stakeholder participation ineffective (Reed et al., 2018). As for implementing participatory techniques, an example of a common obstacle is the legal requirement to emphasize public hearings, which practitioners have long regarded as ineffective (Mease et al., 2018; Rowe and Frewer, 2000). With respect to evaluation, one of the greatest challenges is the lack of efficient and inexpensive tracking metrics (Mease et al., 2018).

Among recent studies of stakeholder participation in environmental management, Mease et al. (2018) are exceptional in their focus on the perceptions and experiences of practitioners. Their study, based on interviews with resource managers in fisheries in the US, Australia, and Canada, identifies lists of goals and principles of stakeholder engagement; strategies and metrics for fulfilling the principles and achieving the goals; and guidelines for best practices. Although the study’s findings and recommendations are valuable, further research is necessary both to confirm its results in other resource management contexts and to identify challenges and strategies that may not have surfaced in its analysis. In the discussion section that follows our findings below, we compare and contrast the findings of the fisheries study with our own.

3. Methodology

Conducting a case study focused on the Great Lakes Areas of Concern (AOC) program allows us to test both the applicability of the Luyet et al. (2012) framework and the principles and strategies identified by Mease et al. (2018) in a specific, distinctive context. The case study research method is appropriate when the object under investigation cannot be separated from its context (Yin, 2014). Our first method for gathering data was an online survey, conducted in the spring of 2014, of representatives from three groups: Remedial Action Plan coordinators from state agencies, local RAP coordinators, and local stakeholder organizations usually called citizen, community, or public advisory committees or councils. In order to ensure their relevance and appropriateness, we developed the survey questions in collaboration with staff from the Great Lakes National Program Office in the US Environmental Protection Agency and from regional Sea Grant agencies with extensive experience in the AOC program. We distributed the survey to the Great Lakes Commission’s entire list of coordinators from all but one of the US AOCs (we omitted Oswego, which was delisted in 2006) and the AOCs along the US-Canada border (Figure 1). Although we excluded the AOCs that are entirely within Canada, we included Canadian coordinators at binational AOCs. Out of 90 invited representatives, and after following up to encourage non-respondents to participate, we received 57 responses (63%), 49 of which completed the entire survey (54%). Personnel from state agencies were best represented (33% of the completed surveys), followed by “other” (including academics and a few identifying “private citizens”); the rest were from local government, other government or intergovernmental agencies, or nonprofit organizations. Out of thirty US and binational AOCs included in the survey, we received at least one response from 24 AOCs, and we received two or more responses from 12 of these (i.e., in some cases, more than one person from an AOC submitted a response).

Figure 1.

US and binational Great Lakes Areas of Concern (Courtesy of US Environmental Protection Agency)

We followed up the survey in the summer of 2014 with a series of 18 telephone interviews with survey respondents who agreed to an interview. Our interviews were semi-structured, in that we asked a set of questions to all participants, but also asked questions about the unique circumstances at each AOC or about themes salient for the participant. Interviewees represented 14 different AOCs, including two binational AOCs. Three AOCs had either two or three respondents each, and in all we had three respondents from Canada. A few interview participants had coordinated stakeholder participation at more than one AOC, which meant that they could bring a comparative perspective to their interviews. We coded and analyzed the interviews with the assistance of NVivo qualitative data analysis software.3

It is important to recognize the limitations to our approach. First, the survey sample was too small for extensive quantitative analysis, and respondents in both the survey and interviews were self-selected. We did not receive responses from all US or binational AOCs, and it is possible that perceptions are different at the AOCs that did not respond. Consequently, we cannot generalize our findings to the entire population of AOCs. Second, the expressed perceptions of these coordinators and advisory committee leaders provide a limited and decidedly partial perspective on the state of stakeholder participation at AOCs. A more complete picture would need not only to address the perceptions of the full range of stakeholders, but also to apply other measures that move beyond expressed perceptions. Nonetheless, we contend that the intimate familiarity of our respondents with both the stakeholder participation process and the AOCs themselves makes their perceptions extremely valuable for developing conceptual models of the implementation of stakeholder participation, which can in turn be tested and modified in studies of other environmental management projects.

4. Stakeholder participation at AOCs: challenges and strategies

4.1. Introduction: General perceptions

In general, survey respondents perceived stakeholder participation in AOCs as healthy overall, although not all held this view. Almost all respondents (48 out of 49 who responded to the question) reported an organized, active stakeholder/citizen participation group in their AOCs. Most noted that these groups had been in existence over twenty years, and in many cases since the origins of the AOC program in the 1980s. Respondents suggested that these groups meet regularly—typically a few times a year (50%), more than monthly (4.2%), or monthly (37.5%)—and are involved in virtually all aspects of RAPs. Only four (8.3%) reported that groups met only occasionally, with no regular meeting. In addition, most (27 out of 46, or 58.7%) characterized the involvement of stakeholders in recent years as “sustained/steady,” and eleven out of 46 (23.9%) characterized this involvement as “increasing,” while only eight out of 46 (17.4%) characterized it as “decreasing/declining.”

According to survey respondents, the most active stakeholders in the remediation and restoration of US and binational AOCs are state agencies, but active stakeholders fall into a wide range of categories. As Table 1 shows, almost all respondents classified state government or agencies as “very active,” and none classified them as “not active.” A second tier consisted of environmental NGOs, federal government agencies, and municipal government, which a majority of respondents classified as “very active” or “somewhat active.” Residential and recreational users were classified by roughly equal numbers as “very active,” “somewhat active,” or “occasionally active,” and industry/business was the most likely to be reported as “occasionally active.” Tribal governments and ports were the most likely to be reported as “not active,” but this largely reflects the absence of these groups at many AOCs. Only a few AOCs intersect directly with the territory of American Indian reservations or First Nations reserves. Several AOCs reported tribal/indigenous governments as “very active,” while ports were the least likely to be reported as “very active.”

Table 1:

Reported levels of stakeholder activity (number of responses; totals vary)

| Very | Somewhat | Occasionally | Not active | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State government or agencies | 43 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Environmental NGOs | 23 | 12 | 4 | 4 |

| Federal government agencies | 21 | 14 | 7 | 3 |

| Municipal governments* | 21 | 15 | 9 | 0 |

| Residential property owners | 14 | 11 | 12 | 7 |

| Recreational users | 14 | 14 | 15 | 1 |

| Industry/business/utilities | 13 | 9 | 19 | 4 |

| Tribal government or agencies** | 12 | 3 | 5 | 22 |

| Other | 11 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| Ports** | 3 | 14 | 10 | 15 |

Including sewer and park districts

Tribal governments and ports are not present at all AOCs, so the figures for “not active” also include “not applicable” for these categories.

Another question asked respondents to report on the different ways that stakeholder groups participate in RAPs. Responses suggested that state agency personnel—who in the US have the lead role in managing remediation and restoration activities—are not only the most involved, but also involved in the largest variety of ways (Table 2). According to respondents, this group is the most likely to attend meetings regularly, to provide funding or donations, to host events, and to plan and implement projects. Most respondents reported that environmental organizations and municipal governments regularly attend meetings; close to half of respondents reported the same for residential, federal, and industry stakeholders. Our respondents reported that state, federal, and municipal government agencies take the lead in planning and implementing projects, although many reported that environmental NGOs, industry, tribal governments, and ports also take part. Other reported stakeholder activities included stewardship activities, political/policy activism and advocacy for particular delisting goals, and general collaboration. As for members of the general public, one interviewee characterized the level of participation as “extraordinary,” but emphasized that “participation” meant very different things to different people:

Many people only get involved with a stewardship role. You know, so there’d be something like a planting or cleanup or something along those lines […]. But they wouldn’t come to a meeting. Some people only come to meetings. Some people might only get involved in one particular project because geographically it’s near them. (Interview 2).

Table 2:

Reported types of involvement, by stakeholder

| Regularly attends meetings | Provides funding or donations | Volunteers time and service | Hosts events and speakers | Plans and implements projects | Other | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State government | 42 | 39 | 10 | 26 | 37 | 11 | 165 |

| Environmental NGOs | 31 | 11 | 27 | 23 | 24 | 11 | 127 |

| Federal government | 21 | 38 | 4 | 13 | 32 | 10 | 118 |

| Municipal governments | 31 | 12 | 16 | 12 | 30 | 15 | 116 |

| Industry/business/utilities | 21 | 15 | 11 | 9 | 18 | 11 | 85 |

| Recreational users | 20 | 2 | 29 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 76 |

| Residential property owners | 24 | 2 | 28 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 67 |

| Tribal government or agencies* | 14 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 12 | 7 | 47 |

| Other | 11 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 46 |

| Ports* | 8 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 11 | 3 | 38 |

Again, tribal governments and ports are not present at all AOCs, and this is reflected in the lower totals.

Despite this overall positive perception, respondents in both the survey and interviews reported enduring challenges and barriers to stakeholder participation. In the survey, a majority highlighted four major barriers: lack of time (32 out of 44), lack of awareness (30), lack of interest (26), and lack of funding (24). A minority reported other barriers, including “perception that the problems have largely been solved” (13), “difficulty with effective communication strategies” (11), “lack of existing networks or organizations to facilitate involvement” (11), “lack of support from government agencies and officials” (8), and “other” (10). A text box permitted respondents to identify other challenges, which included the following:

“competing priorities” and “minority – low income – not as high a priority as job, housing and caring for kids”;

“scientific nature of the problems/solutions does not resonate or mean anything to the general public”;

“inadequate leadership and facilitation skills”;

“AOC cleanup effort takes too long […] decades to get results. Citizens cannot maintain efforts over that long a time period” and “Decrease in interest because of complexity and slow progress of EPA Superfund process and responsible parties”;

“Stakeholder involvement fluctuates based on their level of interest in an issue”;

“Lack of long term funding commitments for volunteer support”;

“Conflict with target goals”;

“Members control local media, units of government… in order to push their agenda.”

Only two respondents selected “none of these are significant barriers,” suggesting that despite the general health of stakeholder participation, most coordinators still see important challenges for making participation work.

Although our findings focus on challenges over which local coordinators have some control, respondents also reported overarching shared challenges over which they normally have little to no direct control. For example, the competing priorities and commitments of potential participants present inevitable constraints on recruiting stakeholders and volunteers. Perhaps the most obvious perceived challenge beyond the control of local coordinators is one of the top four reported in the survey: the lack of funding adequate to support stakeholder activities and paid staff members focused on coordinating participation. Although coordinators can apply for grants or request money for projects, they typically cannot control the availability of funds, particularly at the levels of state/provincial or federal government. Levels of funding are in turn connected with political changes and attendant shifts in policies and priorities, which emerged as a theme in several interviews.4

Among the most important and visible results of shifting political and funding trajectories at AOCs are fluctuating levels of remedial activity. As several respondents noted, prolonged periods of inactivity due to lack of funding or changing policy priorities can dampen public and stakeholder interest. According to one state agency official, “[They] had a very diverse group, and then when nothing was happening in their Area of Concern, you know, nobody was moving anywhere […]. They just quit coming to meetings” (Interview 16). Similarly, a Citizen Advisory Committee (CAC) chair remarked, “As far as stakeholder participation, I think it helps to actually have something going on […]. That was tough for a while, there were all these plans about what needed to happen, but there really wasn’t any movement for a long period of time” (Interview 14).

The difficulties associated with low activity at an AOC can be amplified by the sheer length of time involved in the remediation process. Some AOCs began remedial action planning in the mid-1980s. A Canadian participant said, “[R]emedial Action Plans have been going on for so long, people have come and gone, and sometimes they even forget that it’s a program that’s […] happening” (Interview 5). Another interviewee who reported levels of participation as “high, but declining recently,” discussed the variety of challenges in sustaining long-term participation:

We’ve had people pass away, and […] we went through three or four governors, we went through three or four [state regulatory agency] representatives, federal representatives. […] Some people’s careers […] have solely been working on this. […] Just because it took twenty years, you can’t expect people, citizens, to be totally excited about it for twenty years. (Interview 7)

Again, an AOC coordinator can do little about high-level political shifts and the fluctuating levels of funding that accompany them. But when funding is adequate, and policy is favorable, more challenges may fall within the local manager’s control; we turn to these in the sections that follow.

4.2. Recruiting active and representative stakeholders

In general, our respondents did not report stakeholder identification and characterization as major difficulties; however, many discussed challenges with the next step: recruiting a mix of stakeholders who are both active and appropriately representative of the full range of affected constituencies. Several reported that constituencies or “slots” they had identified as important were under-represented. A number attributed this to low visibility and awareness, and they discussed a range of communication strategies for getting an appropriate number and range of stakeholders involved.

4.2.1. Representation on stakeholder committees

Identifying an appropriate range of stakeholder “slots” for participation in an AOC remedial planning project does not guarantee that they will be easy to fill. Several interviewees described how they had defined the appropriate composition of non-technical stakeholder groups.5 One interviewee from a binational AOC, for example, listed 14 different sectors:

agriculture, business/industry, citizens at large, community groups, conservation and environment, education, fisheries, health, labor, shipping, tourism, recreation, four agency reps, Native and federal government (Interview 13).

Another interviewee described the Citizen Advisory Committee as “evenly divided between general environmental interests and general business economic interests” (Interview 1). However, the same interviewee described their advisory committee as “about half-full” (Interview 1). A different interviewee from the same AOC also suggested that efforts to secure widespread representation on the Citizen Advisory Committee had largely failed: “we have tried to organize it so we get representation from many different sectors. That just didn’t go anywhere […]” (Interview 14). In addition, even when the slots are full or almost full, this does not guarantee active participation. As an interviewee from another AOC noted, “right now we have a couple of vacancies [but] some of these folks don’t come to the meetings” (Interview 6).

According to our respondents, some slots are more difficult to fill than others. In the survey, 39 respondents reported at least one group as potentially under-represented in stakeholder participation, which underscores the idea that attracting and recruiting an adequately representative mix of stakeholders is a common problem. However, the groups perceived as under-represented varied among AOCs, and there was no clear pattern. The group most commonly reported as under-represented was business/industry (16 responses). Next were municipal or other local governments (9, including one specifying a local sewerage district and other governments from “geographic areas downstream”). One interviewee noted that “at times with some of our projects it’s been somewhat difficult to get the municipalities on board,” in part because the AOC “covers a lot of jurisdictions” (Interview 2). Another characterized “the ones we have a harder time getting” as “the elected officials and municipal type people” (Interview 3). One factor that complicates efforts to involve local and municipal governments is that different stages of the remedial process may require different actors and agencies. For example, one interviewee discussed the need to change the mix of stakeholders in the transition from planning to implementation (Interview 11). The issue could be that local governments simply have insufficient staff and too many other priorities, but confirming this will require additional research.

Six survey respondents characterized tribal or aboriginal governments as under-represented, and an interviewee from a binational AOC identified this group as the most difficult to attract: “the challenging one that I think we’ve made a lot of headway on is Native. Generally they don’t participate” (Interview 13). Another state agency representative noted that they invited a nearby tribal government, but “because all of the projects are outside the reservation, they were not interested in participating” (Interview 1). In contrast, others reported tribal/First Nations governments to be very active in all aspects of the remediation: “I work with [a nearby tribe] and their reservation. They’re very supportive” (Interview 3). In one case, the respondent described a tribe affected by the AOC as highly involved, but explained that their outreach was limited by territorial boundaries (Interview 17). An interviewee from a binational AOC noted the importance of recognizing the cultural and legal differences pertaining to indigenous communities, noting that the First Nations active in remedial planning at the AOC preferred to be regarded as governments rather than “stakeholders” (Interview 5). Clearly, the involvement of reservation/reserve governments and communities varies depending on the circumstances of the AOC. Some respondents discussed specific strategies for effective collaboration with indigenous communities, which we present in a subsequent section.

Only a few survey respondents characterized citizens and non-government constituencies as under-represented in AOC stakeholder groups: residents/residential property owners (9 respondents), recreational users (4), citizens/general public (3), and NGOs (3). A few other groups appeared once each within the responses: the philanthropic community/donors; education; health; minorities; and in one case, “everyone else” besides the group dominating the process. Only one interviewee discussed the under-representation of urban communities of color, but emphasized that at their AOC this was the greatest challenge: “We have tried many different ways to outreach to them: partnering with them, working with them, and providing some programming where it is hand in hand” (Interview 15). This interviewee suggested that partnerships with organizations like the Boy Scouts were beginning to help diversify public participation; another indicated similar results from partnerships with “faith communities” (Interview 18). Overall, however, most respondents did not mention the under-representation of people of color or other minority groups. This may reflect the relatively homogeneous demographics at several AOCs, but in some cases efforts to reach and include under-represented communities may have been unsuccessful or non-existent. This, too, is an issue that will require further research.

Another kind of under-representation reported in the survey and interviews was generational. One survey respondent suggested that “over-represented” stakeholders at their AOC were homogeneous in more ways than one: “old white guys…with interest and time on their hands.” Although gender did not emerge as a theme in the interviews, age came up multiple times. One respondent explained that some people were involved since the beginning in the 1980s and that “a lot of us are retired now” (Interview 12). Another noted that when she started, she was in her fifties and “still felt like one of the youngsters” (Interview 14). An agency representative explained, “there probably is greater representation of the baby boomers that haven’t stopped working on these things, and there’s less […] participation by younger groups” (Interview 5).

On the one hand, there are positives in the greater representation from what one interviewee (12) called the “old timers,” since this group brings not only a high level of commitment, but also the experience, perspective, and knowledge that come from years of involvement. On the other hand, for AOCs not yet close to delisting, there are risks in the lower involvement of younger people. The interviews suggested that several factors might be at play in the perceived generation gap in the AOC program, including the distant origins of the AOC program and the additional time and resources that older adults might have at their disposal.

4.2.2. Filling vacancies: Attracting stakeholders

Given the wide range of constituencies reported in the survey as “under-represented,” we asked our interviewees to discuss barriers to filling these slots, as well as strategies for overcoming these barriers. According to our participants, one of the biggest challenges is the lack of local awareness. Several interviewees noted that potential stakeholders and the wider community are frequently unaware of the AOC. One AOC Coordinator remarked that she would ask people about the AOC while out in the community, but “nobody’s heard of it” (Interview 16). A Citizen Advisory Committee Chair from a different AOC hypothesized, “because this is still a heavily industrialized river, a little bit more industrial activity didn’t catch anybody’s attention” (Interview 14). Even an interviewee who reported very high rates of participation acknowledged that public awareness has been a major challenge, describing the AOC as “the best kept secret in town,” and noted that “it is really hard to get the word out that broadly” (Interview 2).

As multiple interviewees noted, one barrier to greater local awareness is the low visibility of both the work and the contamination. One described two years of cleanup dredging activity, which they thought “would probably get people’s attention, there was plenty press coverage of it locally. But still, I talked to people they had no idea what was going on” (Interview 14). Not only had the company routed transportation to minimize the impact on the community, but also: “the dredging equipment was right next to the shipyard, [and] a lot of people are used to seeing heavy equipment next to the river anyway” (Interview 14). Just as dredging activity can easily become “invisible” in an industrialized area, so too it is difficult to pay attention to remediation when the contaminants themselves are invisible or hidden: “You can’t see the contamination, it was 20 feet below the river […]; physically it’s very difficult to see the change” (Interview 7). Of course, such issues are not unique to AOCs; many environmental projects have similarly low visibility.

Our interviewees shared differing opinions about the most effective ways of reaching potential stakeholders and participants in such circumstances. When visibility of the work is low, it can be challenging to attract people to face-to-face meetings and workshops, which a large majority of survey respondents rated as the “most effective” method for communicating with stakeholders. One interviewee contended that “[t]he best outreach really is word-of-mouth through our committee members” (Interview 1). As several interviewees pointed out, this kind of outreach is more difficult when the AOC program has no officials or representatives present within a community. One respondent from a binational AOC contended that it can be particularly challenging “trying to whip up enthusiasm when you’re based out of […] another community, like two hours away. You’re not approachable, you know” (Interview 17). While acknowledging that local volunteers can mitigate some of the challenges, the interviewee contended that “you still need to have [some] sort of a contact based within the community who’s, you know, going out there and doing your stuff” (Interview 17). The same respondent attributed a higher level of participation on the Canadian side of this binational AOC in part simply to having a local presence: “I think it’s just because you have someone right here in the community” (Interview 17). Another interviewee suggested that an effective yet underutilized approach to recruiting younger participants is visiting high school and college classrooms (Interview 15).

After word-of-mouth, the next most popular method of communication in the survey was email lists, which 19 respondents rated as “most effective” and 18 as “somewhat effective.” One interviewee described email as “our biggest communication tool,” which they use to share meeting invitations, meeting minutes, and “other interesting facts” with local stakeholders as well “agency folks and other interested parties” (Interview 1). Other methods that a majority rated as either “most effective” or “somewhat effective” included web sites/blogs, educational presentations, and traditional media (TV, newspapers, etc.). The same interviewee quoted above also suggested that website design can make an important difference in navigation; “it’s easy to get lost on state agency sites because there’s a million pages,” so the AOC has a separate web site using the state extension service “that’s a lot easier to navigate,” and “it’s really easy to get stuff posted” (Interview 1).

A few survey respondents also rated onsite interpretive exhibits and social media as “somewhat effective” means of outreach, although these were the least likely to be rated “most effective.” Social media emerged as a topic of discussion in several interviews. One interviewee argued that moving towards increased use of social media was essential for attracting younger people: “We’re not getting the younger people, and […] we’re not reaching them on the media that they like to be reached on, like Twitter” (Interview 16). However, the use of social media can be complicated by restrictions faced by government agency personnel: “As a state agency, we have restrictions. DNR has an official Twitter and an official Facebook page, […] but it’s official. […] It’s just not the right fit, me broadcasting something statewide that’s very local and very specific” (Interview 1). Others pointed out that social media pertaining to an AOC need not come from official government agency sources, and as of 2018 several advisory committees have their own AOC-specific Twitter or Facebook accounts. Still, our interviewees suggested that the social media profile of AOCs is not as high as it could be.

A few interviewees emphasized that one key to raising awareness and attracting participants is putting people in direct physical contact with the AOC. For example, one described the use of boat tours and canoeing or kayaking events to recruit participants: “We want to keep connecting our target audience with the water” (Interview 3). The events then become opportunities to hand out “fact sheets, and brochures, and […] giveaway bags or goodies for people” (Interview 3). Another cited a canoe trip that successfully attracted low-income and minority communities—and helped generate a culturally diverse group of interns—by combining education and recreation (Interview 15).

Even though few survey respondents identified traditional news media as a “most effective” form of communication, some interviewees stressed the importance of conventional media in their outreach efforts. Some cited relationships with local media outlets as crucial for countering the lack of public awareness and boosting stakeholder participation. In one AOC, a Public Advisory Council member explained that they invited newspaper and TV stations to their regular meetings and, “we try to […] point out all of our successes at every meeting, every quarterly meeting. […] And that’s, I think, really encouraged businesses to come in and help” (Interview 9). Another interviewee contended that press coverage was worth the effort even if it did not result in increased participation: “We got a lot of mileage with regards to—we were in the newspaper, we were on public access cable television” (Interview 4). However, others pointed out that the unglamorous nature of work at AOCs made it difficult for them to attract conventional media attention. For example, one state AOC coordinator described a failed effort to publicize events in which students removed invasive species for different AOC projects: “We put out a press release with a couple of nice photos and sent it to the local newspaper, and we could not get them to run it” (Interview 1).

Although the expressed perceptions of our survey and interview respondents cannot provide conclusive evidence on the most effective methods of outreach, they suggest a variety of important directions for future research on stakeholder recruitment, which we will revisit in the conclusion. Moreover, a few interviewees pointed out that the goal is not necessarily to attract large numbers of people to participate directly in the RAP decision-making process. One emphasized that for meetings oriented toward planning and decision-making, smaller groups are often more effective (Interview 17). Others distinguished between the need for stakeholders in the RAP decision-making process and the need for volunteers in the many cleanup and restoration activities that make the AOC program distinctive. For example, one Public Advisory Committee Chair explained, “We are not looking for members to come to the meetings, but we do put on cleanups” that require volunteers (Interview 4). In combination, our respondents suggested that the goal of stakeholder recruitment is not to recruit as many stakeholders as possible, but to attract a committed, active core group with an optimal size for collaborative decision-making. This objective hints at the task of integrating stakeholders successfully within the decision-making process, to which we turn in the next section.

4.3. Integrating stakeholders into decision-making processes

In some cases, integrating stakeholders into decision-making may be relatively straightforward, but some respondents noted that it becomes a challenge if particular interests or viewpoints become dominant or “over-represented” within stakeholder advisory committees. On the one hand, a majority of respondents to a survey question about this issue (19 out of 32, or 59%) regarded no groups as over-represented, and there was little indication that our respondents perceived this a widespread problem. Four respondents identified some variant of the general public or “concerned citizens” as over-represented, although two of these noted that they did not see this as a problem. Three viewed environmental non-profits as over-represented; however, an equal number viewed them as under-represented.

On the other hand, some survey respondents and interviewees suggested that problems can emerge when particular groups become over-represented or dominant in the process. Over-representation of a particular constituency may be rare, but it becomes a risk when membership on advisory committees is open to all interested parties. Although most interviewees reported a range of specific sectors whose representation they sought, they also emphasized that advisory committees were open to all. As one put it, “anyone who really wanted to get involved could get involved” (Interview 10). However, with open membership, questions may arise about how to determine when stakeholders should be included in votes on significant decisions. One state agency official proposed the concern: “What if a whole bunch of people showed up to a meeting and everyone voted against [a major policy decision]?” (Interview 1). The quote suggests the perceived need to strike a balance between open membership and rules determining which members can vote.

As one interview demonstrated, open membership can enable a single interest group to take over the process and wield disproportionate power over decision-making. In this unique instance, it initially appeared that the stakeholder group for the AOC would be widely representative. However, according to the interviewee, one group with a strong interest in rapid delisting of the AOC quickly assumed control of the RAP process and changed the nature of the committee: “They pushed the other people out. The recreational or environmental folks. They didn’t allow press to their meetings” (Interview 16). With the passage of time, the dynamic has changed: “It seems like now we’ve got some interest in the community, into forming a group like a watershed council, which will have the AOC interests as part of it” (Interview 16). Although this AOC is unique, it demonstrates the need for balance between openness on advisory committees, which can invite motivations at odds with the AOC program, and the need to adhere to the constraints, requirements, and objectives of the RAP process.

Several interviewees suggested that they found ways to prevent such problems by developing and incorporating rules or customs for integrating stakeholders into RAP decision-making processes. Some described formal bylaws and procedures as key mechanisms for balancing open membership with the need to avoid over-representation: “We put together these bylaws in these categories to try to maintain a balance on the committee, in an effort to control who can vote on committee support issues” (Interview 1). In other cases, the approach is less formal, but interested parties must demonstrate commitment and receive the support of the committee before gaining access to voting membership. Overall, the interviews suggest no “one-size-fits-all” solution to balancing open membership with an appropriate mix of active stakeholders in decision-making, but they also suggest that rules of some kind—whether formal or informal—are a necessary component.

Interviewees described other considerations for efforts to integrate tribal and First Nations governments and communities into remedial planning. One is recognizing that members cannot typically speak for a community without official approval from their own council. As one Canadian interviewee described it:

Only the Band can speak on behalf of the First Nations [government]. So when the members come in, they are basically representing their Band [and must get approval from their council]. (Interview 13)

The same interviewee described how on one occasion the federal government agency seeking to carry out a survey overlooked the protocol for gaining approval through consultation with the First Nations government; as a result, the survey was significantly delayed. Another consideration is the need for decision-making processes to recognize cultural differences in the impacts of beneficial use impairments, as well as the criteria for delisting them. An interviewee at another binational site pointed out that contaminated fish, for example, has more far-reaching implications when indigenous communities are impacted:

They do all of their planning on a seven-generation approach. […] Their economic livelihood has really been damaged because they had an eel fishery, they had a lot of other things that they were able to glean from the river, and that’s all gone. You can’t eat the fish, and the eels are virtually nonexistent at this point. We’re working on that now, but things like that… really impacted them in a way that it didn’t impact other people. […] And I think it was a real eye-opener for, you know, all of us who didn’t grow up on [the Reserve] to hear […] [what] being a contaminated area means to them, and has meant to them, and what their expectations are in terms of trying to clean it up. (Interview 17)

Although indigenous communities may not be directly affected by all environmental projects, it is nonetheless important that procedures for integrating constituents into decision-making processes must recognize and accommodate such legal and cultural differences.

In short, integrating different constituencies and communities into participation in remediation introduces additional challenges. AOC leaders and coordinators must consider how to keep one group from dominating the process, how to incorporate different individuals and groups into voting and other decision-making procedures, and how to ensure that remedial action planning respects both the legal and cultural distinctions of affected indigenous communities.

4.4. Sustaining participation: challenges

Just as recruiting and integrating stakeholders present distinctive challenges for those who coordinate participation, so too does sustaining their participation over the long term. Although only eight survey respondents out of 46 characterized the involvement of stakeholders in recent years as “decreasing/declining” (see above), a few commented that participation had “waxed and waned” over the years, fluctuating alongside changes in support and “perceived urgency.” In addition, several interviewees discussed the challenges of sustaining participation. Three key themes emerged in our interviews: (1) getting things done; (2) attracting participants who are committed, skillful, and well-connected; and (3) making participation meaningful, by fostering social relations and opportunities for participants. In this section, we consider each of these in turn.

4.4.1. Getting things done

Several interviewees emphasized that simply getting things done was one key to sustaining participation. As one remarked, “There’s nothing that succeeds like success” (Interview 2). Ongoing reporting to the community enhanced visibility, “in that we spent the time, the effort, and we fed back to the communities, and I think they saw that we were listening, and that we’re considering their input” (Interview 5). Others also highlighted such successes as major factors in keeping stakeholders and participants involved and interested.

Although the ability to get things done depends on funding and policy priorities beyond local control, AOC coordinators and committees have the power to prioritize, which some interviewees argued is another essential factor in sustaining participation. Some suggested that one key is ensuring that the list of tasks is both manageable and fully within the scope of the AOC program. For example, a state agency representative explained, “We don’t want to have one project hold the whole thing up. You know, it’s been 25 years plus of litigation and restoration […]” (Interview 1).

Another respondent emphasized, however, that it can be challenging for some stakeholders to prioritize, to acknowledge the limitations of funding, or to accept that complete restoration and remediation are beyond the scope of the AOC program (Interview 10). The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) has created an opportunity to improve the Great Lakes ecosystem that may lead stakeholders to expand the list of priorities; “[s]ome groups have seen GLRI as […] a mechanism for them to do what they want to do” (Interview 1). Some interviewees emphasized the need to clarify for stakeholders that the AOC program has a limited mandate and that other “wish lists” will require looking at other programs and funding sources. While they perceived successes as important for sustaining interest and enthusiasm, they also counseled pragmatism about what a RAP can achieve. One survey respondent indicated that the GLRI had helped foster this pragmatism:

New GLRI funding also brought a new focus to work on only those projects that would lead to BUI [beneficial use impairment] removal rather than ancillary projects that were done simply because there was funding and stakeholders wanted to feel that they were accomplishing things. (Survey response)

The flip side of successes is that they can also create an impression that the AOC no longer needs attention. One interviewee explained that stakeholder participation declined after the successful removal of contaminated sediments from the river (Interview 5). Because of water quality improvements over the 30 years since the 1987 Amendments to the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, the challenge at this AOC and others was to keep people interested when the primary task shifted from remediation to research and documentation. One agency official remarked, “The challenge is to now collect the information to prove the case and get people on board to agree that the issues have been addressed” (Interview 5). Other participants pointed out that participation waxes and wanes based on the task to be completed: “[W]hen the PCB [polychlorinated biphenyl] clean-up plan was being developed, participation by paper industries and sewage districts was high. Once the plan was adopted and clean-up began, participation dropped off” (Survey response).

Our interviews suggest consistently that getting things done is important to sustaining interest and participation, but managing perceptions and expectations of participants and the wider community can play an equally important role. For example, at some AOCs citizens are confused between legacy contaminant sources (i.e., historic industry) and present water quality challenges: “A lot of people… think that because they’re cleaning up the PCBs out of the river, … the water is fine” (Interview 3). In contrast, other AOCs struggle with the perception that nothing has changed or improved. In the words of an agency official: “It’s hard going here, because people still think the river is too polluted to be on or in” (Interview 11). Although such issues are in many ways distinctive to AOCs, they nonetheless resonate with problems that complicate stakeholder participation at long-term environmental projects more generally.

4.4.2. Committed and connected: “Champions” and core groups

To sustain long-term participation, interviewees suggested that recruitment must go beyond simply filling representative “slots.” A second important theme in the interviews was the need for stakeholder groups that are not only representative and appropriately sized, but also led by and composed of individuals with the right combination of skills, time, commitment, and connections. Interviewees described successful groups as composed of “people that are willing to come in and dedicate their time to resolving the issues” (Interview 4) or of “dynamic people who are very interested in community improvement […] the willingness to work together was vital” (Interview 7).

Some cited the involvement of “champions,” or “committed and strong local leaders,” as an essential element for sustaining participation (e.g., Interview 12). As other scholarship has suggested, champions bring energy, enthusiasm, and vision, but might also function as the informal experts who have experience, knowledge, and commitment (Adams et al., 2004; Bryson et al., 2013). Their ability to build partnerships not only contributes to their success, but also to maintain progress. Both agency staff and advisory committee leaders identified a number of qualities of champions, including the capacity to “drive the project” and “get things done,” the ability to gain the “respect of both sides” when stakeholders hold conflicting interests, and the skills “to keep things on an even keel” in meetings (Interviews 4 and 12). Another interviewee described the need for champions not only for the RAP process as a whole, but also for specific projects within the AOC (Interview 16). Enough of these “focused champions” can help constitute a core group capable of getting things done and sustaining participation over a longer term.

4.4.3. Connections with other AOCs

Even though such champions and core groups frequently build strong connections and networks within their own AOCs, some interviewees suggested that they had more difficulties forging connections with other AOCs. One agency official remarked, “We aren’t terribly well connected with each other” (Interview 17). This issue also came up with specific reference to binational AOCs, which by virtue of their shared problems might benefit from closer connection: “We’ve never had [three binational] AOCs talk to each other (Interview 13).” In contrast, Michigan is unique in having a Statewide Public Advisory Council run by the Great Lakes Commission. One respondent commented that the Council

definitely helps the Michigan AOCs to be successful, because they can participate in the statewide PAC [Public Advisory Council] and have access to sitting around and shooting the bull with a state person who might be able to help them as far as funds. (Interview 2)

Developing stronger networks of AOCs, whether based on regional interests or shared characteristics (e.g., crossing borders, dealing with similar problems, etc.), could potentially help individual AOCs—especially those in states with only one AOC—sustain long-term stakeholder participation. However, with limited funding and time, local AOC coordinators may not be able to prioritize such network-building. One coordinator commented: “It’s just a matter of priority… I have to look and see where I can make the biggest bang for my bucks which is right here” (Interview 13). In order for networks of AOCs to help overcome challenges to sustaining participation, there needs to be careful attention to how to make networking relevant and worthwhile, especially given the costs sometimes associated with it.

4.4.4. Making participation meaningful: social relations and opportunities

Another important ingredient for sustaining long-term participation that emerged in our interviews was fostering meaningful social relations and opportunities. A Community Advisory Committee Chair noted that the AOC community is now tackling the question of how to orient stakeholder participation not just toward achieving outcomes at the AOC, but also toward making participation beneficial and meaningful for stakeholders themselves. In order to keep stakeholders engaged “both initially and long-term,” she suggested “making sure they make connections with other people, enhance their network, kind of provide them with professional development (whatever that may be) or new knowledge, those types of things” (Interview 18). In addition, several interviewees suggested that some of the most successful stakeholder groups have leveraged existing long-term friendships and professional relationships. The “champion” at one AOC had built the core group by building on such relationships:

She started the PAC [Public Advisory Council] […] and convinced all of her environmental friends to get on it eventually. And some non-environmental friends, who might represent some geographic areas that we needed better coverage. (Interview 2)

In addition, the group tries to keep the stakeholder group friendly and social, rather than aloof or combative: “we’re friendly and nice and not adversarial – but without any compromise of what we think needs to get done. […] Just like, you know, we go out for drinks afterwards and those kinds of things. […] We don’t expect it to be a tug of war” (Interview 2). As another interviewee noted, “It took a lot of meetings with a tight group of people before we could get it bigger, you know” (Interview 16).

A few interviewees suggested that one key to making participation meaningful is transforming business meetings into social events. One interviewee provided an instructive example from a partnership with a First Nations community within the AOC:

They said, “Look, you always invite us to come over there, but you don’t know what we’re about.” … They said: this is how we conduct meetings over here. […]. We had to have corn soup, and we had to have a full meal, and you know, do it the way they suggested, and it worked. (Interview 17)

Although formal meetings with limited interaction will likely continue to have an important place in participatory environmental management, the example suggests that highly interactive cultural exchanges—conducted over a meal and scheduled regularly—may be a more effective way of forging relationships and sustaining effective stakeholder participation over a longer term.

Having regular events oriented specifically toward building relationships may also help solve the problem of attracting younger people to participate. One interviewee reported that younger people may be attracted to specific projects or events, but these may not be enough to keep them coming back: “If we have a specific project they are very enthusiastic, but keeping them coming to meetings and everything, I haven’t had much luck with that” (Interview 14). As another interviewee noted, it may also be challenging to create a sense of connection to AOCs in younger people who did not experience the establishment of the AOCs in the first place, especially after they are delisted: “People today do not understand what happened in the ‘80s, and then don’t understand the rationale for the AOCs. […] It’s just history to you, and so I want to make sure that it’s going to be meaningful and current” (Interview 13). There are no simple answers to the question of how to overcome the generation gap, which is a critical issue for sustaining participation in long-term remedial projects. But our interviews suggested that in addition to experimenting with newer forms of communication, AOC coordinators may benefit from investing in events that can go beyond offering interesting one-time experiences, by fostering meaningful and lasting relationships.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Although the Great Lakes AOC Program is in many ways unique, we contend that it nonetheless provides insights and raises questions of significance for a wider array of environmental management projects. First, our results carry implications for how to conceptualize the components or stages of stakeholder engagement. Instead of replacing the conceptual model developed by Luyet et al. (2012), we propose to supplement and develop their framework by incorporating the three processes that emerged as significant within our findings: recruiting stakeholders, integrating them into the process, and sustaining the participation of stakeholders over long periods of time (Figure 2). First, we propose adding the stage of stakeholder recruitment after stakeholder identification and characterization. Second, we propose reframing the stages of structuration, choosing techniques, and implementing techniques as part of a broader process of integration. Finally, we propose adding the process of sustaining participation in a stage that also includes evaluation and monitoring. The expanded model we propose preserves the constraints, pressures, barriers, and opportunities offered by what Luyet et al. (2012) identify as the “project context”: for example, political changes and the attendant shifts in policy and funding priorities.

Figure 2.

Proposed expansion of Luyet et al. (2012) framework for stakeholder participation, with our additions in gray (modification of Figure 1 from Luyet et al. 2012)

The two stages that we add to the model—recruiting and sustaining—both suggest topics that merit additional research. Although the processes of stakeholder identification and characterization have received considerable attention in environmental management and governance, our findings make it clear that identifying potential stakeholders is not the same as recruiting and attracting actual stakeholders. Several interviewees, for example, described their challenges in filling the vacant “slots” in advisory groups. Our respondents suggested that face-to-face contact, direct contact with the environmental project, and both conventional and social media all have key roles to play, but there is a need for more systematic research to examine what strategies work best. Methods for recruiting stakeholders have been a topic of investigation in other fields, such as medical research (e.g., Valerio et al., 2016), but very few studies in environmental management and governance have given close attention to the question of how to recruit identified stakeholders and enroll them in active participation (see, e.g., Flint, 2013; Samuelson et al., 2005).

Another dimension of stakeholder participation that requires additional research is the challenge of sustaining participation over a long period of time. As the experience of the AOCs illustrates, major environmental projects can last years or even decades, often making sustained participation difficult. The long-term nature of many environmental projects can lead to declining enthusiasm and trust, particularly if participants do not see tangible results of their efforts (Butler and Adamowski, 2015; Pahl-Wostl and Hare, 2004). As Butler and Adamowski (2015) note, the time commitments required by long-term projects also present greater challenges for marginalized communities, who often face significant constraints on their time and availability. This presents the risk that long-term participation in environmental projects will be homogeneous, and that participation will favor privileged individuals and groups with more time and resources (Brookfield et al., 2013). Additional research, drawing on the expertise and experience of practitioners and stakeholders alike, can help expand knowledge of best practices for overcoming such challenges.

Second, our expanded conceptual framework for the implementation of stakeholder participation provides a basis for comparing and contrasting our study with the recent study by Mease et al. (2018) of stakeholder participation in fisheries management. This is the only recent study that shares our focus on the perceptions and experiences of practitioners, so it lends itself well to comparison. Mease et al. (2018, p. 251) found in their interviews with resource managers that the principle of stakeholder participation cited most frequently among the nine they identified was “relationship-building,” and the goals cited most frequently among the ten that emerged in their interviews were “building trust between stakeholders and resource managers, and engaging under-represented populations.” Although these findings are largely consistent with ours, there are some important points of divergence.

For example, with respect to the stages of stakeholder identification and recruitment, “females, youth, and racial and ethnic minorities were repeatedly identified” in their interviews as under-represented in the decision-making process (Mease et al. 2018, p. 251). Our participants mentioned youth frequently and minorities in one case, but none—including the women who made up 10 of our 18 interviewees—mentioned women as under-represented. Our findings also point to different kinds of constituencies perceived to be under-represented, such as business and industry or local governments. These divergences may reflect a difference between fisheries management and environmental remediation, and it suggests that groups likely to be under-represented vary depending on the setting and type of project. This suggests a need for more comparative research investigating how barriers to and successful strategies for recruiting commonly under-represented constituencies differ across programmatic areas and international context.

As for participatory techniques and integration, the two most frequently cited strategies by participants in the Mease et al. (2018) study are “advisory groups” and “key communicators,” followed by websites, public hearings, and electronic newsletters. The two leading strategies clearly resonate with our findings from Great Lakes AOCs. Since all AOCs already have stakeholder advisory groups as an integral part of the process, these did not emerge as a separate theme in our interviews. However, what Mease et al. (2018) call “key communicators” correspond closely with what our participants called “champions.” The AOC program suggests an important distinction between formal and informal strategies: advisory committees and their bylaws are a formal part of the AOC program, while champions and their networks constitute an emergent, informal structure. Many other of the 22 strategies on their list also appeared in our interviews, but others—such as fishing gear shops—are more context-specific. Among newer communication strategies, Mease et al. (2018) mention that one of the reported risks of social media is that it might miss particular audiences, but our interviews suggest an additional challenge: the restrictions that government personnel might face in using it for outreach. Again, strategies that work for one kind of environmental project may not work for another, but it is clear that some fit a variety of management contexts. In combination, these findings suggest a need for comparative research investigating variations among characteristics of successful advisory groups, strategies for cultivating “champions” or “key communicators,” and effective methods of communication with current and potential stakeholders.

Finally, with respect to all stages in the conceptual model, our interviews suggest conceiving of the significance of relationship-building for stakeholder participation in a somewhat broader way. Mease et al. (2018) emphasize the significance of building relationships and trust between managers and stakeholders, which also emerged in our interviews. They also briefly mention the importance of fostering broader “relationships between managers, key communicators, and communities” (2018, p. 254); however, our interviews also highlighted the importance of relationships among stakeholders themselves. This means, on the one hand, building on existing networks and relationships in order to recruit participants and sustain their participation, and on the other, cultivating stakeholder engagement as an opportunity for stakeholders to build new social connections and deepen existing relationships. Managers often perceive this kind of relationship-building as expensive, time-consuming, or too difficult to quantify. However, cultivating relationships does not necessarily mean burdening government agency personnel—tasked above all with “getting things done”—with new or additional responsibilities. As the case of AOCs suggests, adequately empowered and well-designed public advisory committees can often take on the work of relationship-building among stakeholders. This cooperative model did not emerge spontaneously; it evolved over the past thirty years as the AOC program has matured. Nonetheless, it provides a powerful example for how the leading strategies of advisory councils and key communicators/champions can be linked.

The idea that successful stakeholder participation involves cultivating social relationships has important implications for the various stages of stakeholder participation identified in our expanded conceptual model. First, although building on existing relationships can help recruit identified stakeholders to active involvement, managers must take care in the phases of stakeholder characterization and integration to ensure that tight networks do not take over or dominate the decision-making process. Second, some participation techniques lend themselves better than others to the development of relationships among stakeholders, and high-quality stakeholder participation might require moving beyond conventional “toolboxes” for participation. For example, traditional public hearings and formal meetings might need to be supplemented or replaced by stakeholder meetings as social gatherings—such as the meal cited by our interviewee working with an indigenous community, or parties and picnics where the business of the management project is combined with opportunities for informal socializing. Finally, sustaining successful stakeholder engagement requires balancing strong social ties with an openness to new participants, especially from younger people and other under-represented groups, and fresh ideas and perspectives. It also requires working to ensure that stakeholder participation is not only productive and efficient—that it helps get things done—but also socially meaningful over the long term. Again, we suggest that the role of social interaction and relationships in high-quality, long-term stakeholder participation is an important avenue for further research, and we contend that the AOC program’s division of labor between government personnel and public advisory committees provides a valuable model for cooperation. But we also contend that making social relationships central to stakeholder participation has the potential to produce benefits that go beyond improved decisions, by fostering close-knit communities dedicated to environmental stewardship and sustainability.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Recruiting for stakeholder participation demands carefully targeted outreach

Integrating stakeholders requires attention to dominant and minority groups alike

Champions and relationship-building can help sustain long-term participation

Relationship-building among stakeholders should be prioritized

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and assistance of Caitlin Nigrelli, John Perrecone, and Jane Harrison in developing this study, and Katie Rademacher for assistance with transcription. We also thank Deborah Augsburger, the three anonymous reviewers, and our survey and interview participants. We also acknowledge Kate Preiner for her efforts to disseminate the information to the AOC community.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.09.081.

The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement of 1978 replaced the original 1972 Agreement; it was updated in 2012 (International Joint Commission, 2018).

The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) is a federal funding program through which the Great Lakes Interagency Task Force “strategically targets” environmental threats and “accelerates progress” toward long-term ecosystem goals (USEPA, 2018, n.p.).

For longer versions of interview quotations, please see the Supplementary Material online.

Several respondents discussed the difference that GLRI funding has made for stakeholder participation. We address this aspect of AOC remediation elsewhere.

At most AOCs, the Public or Citizens’ Advisory Committee or Council is distinct from the Technical Advisory Committee or Council, which normally consists of technical experts and consultants.

References

- Adams WM, Perrow MR, Carpenter A 2004. Conservatives and champions: River managers and the river restoration discourse in the United Kingdom. Environment and Planning A, 36(11), 1929–1942. 10.1068/a3637 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein S 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35 (4), 216–224. 10.1080/01944366908977225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S, Chapin III FS 2018. Going beyond “it depends:” The role of context in shaping participation in natural resource management. Ecology and Society, 23(1), Art. 20. 10.5751/ES-09868-230120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beierle TC, Konisky DM 2001. What are we gaining from stakeholder involvement? Observations from environmental planning in the Great Lakes. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 19(4), 515–527. 10.1068/c5s [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield K, Bloodworth A, Mohan J 2013. Engaging residents’ groups in planning using focus groups. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Engineering Sustainability (Vol. 166, No. 2, pp. 61–74). Thomas Telford Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson JM, Quick KS, Slotterback CS, Crosby BC, 2013. Designing public participation processes. Public Administration Review, 73(1). 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02678.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler C, Adamowski J 2015. Empowering marginalized communities in water resources management: Addressing inequitable practices in Participatory Model Building. Journal of Environmental Management, 153, 153–162. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin RM, Witt GB, Lacey J 2016. Approaches to identifying stakeholders in environmental management: Insights from practitioners to go beyond the ‘usual suspects’. Land Use Policy, 52, 266–276. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.12.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]