Abstract

Irritability has gained recognition as a clinically significant trait in youth and adults that when persistent and severe, predicts poor outcomes throughout life. However, its definition, measurement, and relationship to similar constructs remain poorly understood. In a community sample of adults (N=458; 19–74 years; M=40.5), we sought to identify a unitary irritability factor from independently constructed self-reported measures of irritability distinct from the related constructs of aggression, depression, and anxiety, and whether it was associated with face emotion identification deficits and hostile interpretation biases previously established in clinical pediatric samples. The three measures of irritability generated a common factor characterized by a rapid, angry response to provocation. This irritability factor had unique associations with tendencies to judge ambiguous stimuli as reflecting hostility, but not with face emotion identification performance. These findings clarify the nature of irritability and its associations with neurocognitive phenomenon.

Keywords: irritability, hostile interpretation bias, emotion identification, reactive aggression

Introduction

Research into the mechanisms underlying irritability is hampered by two challenges. First, researchers debate how to define irritability, especially how to distinguish it from similar constructs (Avenevoli, Blader, & Leibenluft, 2015; Toohey & DiGiuseppe, 2017) which may share associations with candidate mechanisms, such as social interpretation bias. Second, whether irritability-related mechanisms found in children (Brotman, Kircanski, Stringaris, Pine, & Leibenluft, 2017) are present in adults is unknown. Relevant to both issues, studies of adults may facilitate research on irritability. Relative to reports of irritability by parents and children, adult self-reported irritability may more accurately assess internal experience. The present study measures irritability and related constructs in a large sample of adults and its associations with social cue interpretation patterns observed in irritable children.

Irritability and Related Constructs

Current definitions of irritability include a proneness to anger, an increased sensitivity to provocation, and increased likelihood of behavioral outbursts that may or may not include aggressive behaviors (Holtzman, O’Connor, Barata, & Stewart, 2014; Toohey & DiGiuseppe, 2017). Trait anger and reactive aggression are also defined by a proclivity towards negative affect (Fite, Raine, Stouthamer-Loeber, Loeber, & Pardini, 2009; Xu, Farver, & Zhang, 2009) and share similar longitudinal outcomes and cognitive biases with irritability (Stoddard, Scelsa, & Hwang, 2018). However, there are important conceptual differences between these constructs. Trait anger is defined as a proneness to experience anger but does not necessarily capture the outbursts or reactivity that characterizes irritability. Both reactive aggression and irritability describe extreme responses to provocations. Whereas, reactive aggression is defined by aggressive behaviors (i.e., behaviors intended to harm others), irritability is not defined as a tendency towards aggression (Stoddard et al., 2018). Recent empirical work suggests that irritability and aggression are distinct constructs (Bettencourt, Talley, Benjamin, & Valentine, 2006; Bolhuis et al., 2017). For example, reactive aggression and irritability were dissociable in a study of children with cyclothymia (Van Meter et al., 2016). However, we are unaware of any empirical research that has distinguished trait anger and irritability. Indeed, empirical work in the personality field categorizes traits related to anger and irritability together as part of a “volatility” facet of neuroticism (DeYoung, Quilty, & Peterson, 2007). Developmental work on temperament parallels this conceptualization, linking irritability and anger together as a subconstruct of negative affect called “irritable distress” that predicts aggression and is distinct from “fearful distress” (Rothbart, 2007; Shiner & Caspi, 2003). Finally, little empirical research has examined common and unique features of trait anger, reactive aggression, and irritability together, impeding a clear understanding of the discriminant validity of each construct.

Face Emotion Processing in Irritability and Related Constructs

Differentiating anger, reactive aggression, and irritability are important when investigating mechanisms independently associated with each construct. Here we focus on the identification of emotion expressions and interpretation of hostility in ambiguous social stimuli which have been associated with all three constructs. Disentangling these relationships has implications for mechanistic theories (Crick & Dodge, 1996; Wilkowski & Robinson, 2008) and experimental treatments based on them (Penton-Voak et al., 2013; Stoddard et al., 2016).

Children with clinically significant irritability mislabel emotional expressions (Guyer et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2013; Rich et al., 2008) and tend to perceive ambiguous faces as being hostile (hostile interpretation bias; HIB)(Brotman et al., 2010; Stoddard et al., 2016). However, these studies did not consider aggression or anger which have been associated with both face emotion identification deficits and HIB of a variety of ambiguous stimuli (Crick & Dodge, 1996; De Castro, Veerman, Koops, Bosch, & Monshouwer, 2002; Penton-Voak, Munafo, & Looi, 2017). Therefore, tendencies towards anger or aggression may be confounds in studies of face processing in irritability. Conversely, existing face processing studies in trait anger or aggression have not accounted for irritability or tendencies towards affective disturbance. Indeed, the strongest associations between aggressive constructs and HIB are in reactive aggression (De Castro et al., 2002), an affectively-driven aggression with close conceptual ties to irritability.

Depression and anxiety are associated with irritability (Savage et al., 2015; Stringaris, Zavos, Leibenluft, Maughan, & Eley, 2012), face emotion identification impairments (Demenescu, Kortekaas, den Boer, & Aleman, 2010), and interpretation biases (Hirsch, Meeten, Krahe, & Reeder, 2016). The importance of accounting for affective confounds was illustrated recently when specific types of face emotion identification deficits in severely irritable children were associated with co-occurring depression symptoms (Vidal-Ribas et al., 2018).

Current Study

The present study had three goals: (1) to distill a core, self-report construct of irritability, (2) to test the similarity between this construct and potentially related measures, and (3) to test the associations between this irritability construct and social processing impairments previously observed in the literature. Towards those goals, a large (N=458) sample of adults completed questionnaires assessing irritability, anger, aggression, depression, and anxiety. Three well-validated and independently constructed measures of irritability were selected to represent irritability. All items from these were entered into an exploratory bifactor analysis to empirically determine a general factor of irritability. We hypothesized that this irritability factor would be significantly dissimilar from aggression, anger, depression, and anxiety but associated with face emotion identification and HIB.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). Eligibility criteria included: at least 18 years of age; approval ratings of ≥90% on at least 100 prior MTurk tasks; current United States residents, and native English speaker. This study was approved by the [masked for blind review]. Participants provided consent at the start of the study. Exclusion criteria for the bifactor analysis included incomplete irritability questionnaires and incorrectly answering >2 “catch” items. Of the 721 participants who consented, 458 participants (265 female), ages 19–74 years (M=40.5; SD=11.4; see supplemental online material (SOM) A for sample characteristics) met these inclusion criteria. Most attrition occurred when participants were directed to complete the behavioral HIB task in a new browser window. Excluded individuals were younger with greater clinical symptomatology than included individuals (see discussion and SOM B for a detailed discussion of study procedures, participant attrition, and a participant flow diagram).

Procedure

Participants completed: the two face emotion tasks (order was randomized); the vocabulary test; the self-reported HIB measure; depression, aggression, and irritability questionnaires (order was randomized); and demographic questions. Participation lasted 30–60 minutes. Participants received $3 for participation.

Questionnaires

Irritability was assessed using the Affective Reactivity Index (ARI)(Stringaris, Goodman, et al., 2012), the Brief Irritability Test (BITe)(Holtzman et al., 2014), and the Caprara Irritability Scale (CIS)(Caprara et al., 1985). Aggression was measured using the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ)(Buss & Perry, 1992) and the Proactive-Reactive Aggression Questionnaire (RPQ)(Raine et al., 2006). Depression and anxiety were assessed using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS; (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Self-reported hostile interpretation bias (HIB) was measured using the hostile attribution subscale (16 items) of the Social Information Processing-Attribution and Emotional Response Questionnaire (SIP-AEQ; (Coccaro, Noblett, & McCloskey, 2009). Four “catch” trials were embedded in the questionnaires to identify individuals who were not paying attention to the task. For parallel investigations of irritability, sleep, and social and emotional function, participants also completed questionnaires about emotion regulation, sleep, personality, interpersonal functioning, and menstrual cycle that are not discussed further.

Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET)

Participants completed the RMET as a measure of face-emotion identification ability (Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, Raste, & Plumb, 2001). Participants view 36 photographs of the eye region and choose from four possible emotion choices for each image. Participants with accuracy rates ≤ 25% were excluded from RMET analyses (n=3). To account for the language demands of the RMET, participants completed a vocabulary test (Richler, Wilmer, & Gauthier, 2017).

Interpretation Bias Test (IBT)

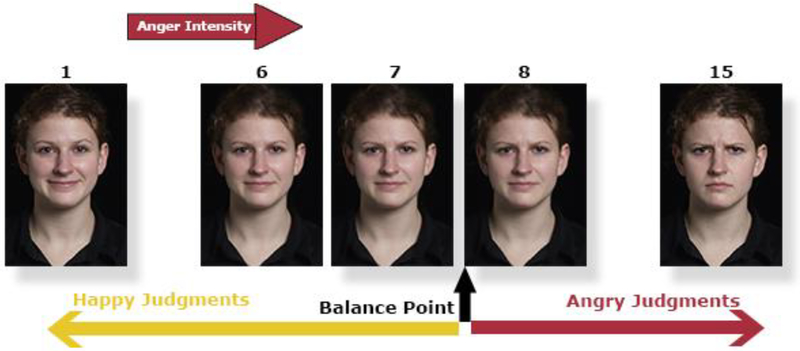

The IBT was based on published paradigms (Penton-Voak et al., 2013; Stoddard et al., 2016). Details about the stimuli and IBT analyses are included in supplemental material (SOM C). Briefly, each participant viewed 15 ambiguous images (“morphs”) generated by morphing angry and happy expressions from a single individual (Figure 1). Each morph was presented three times in random order. Given prior evidence that non-emotional features of faces may influence judgments (Stoddard et al., 2016), each participant viewed morphs derived from one of 16 actors. During each trial, participants viewed a single face stimulus for (200ms), a visual mask (200ms), and finally a “?” until keypress (“c” for happy and “m” for angry). No feedback was provided.

Figure 1.

Sample morphs from the IBT task and sample balance point. The image on the left represents a 100% prototypical happy expression. The image on the right represents at 100% prototypical angry expression. 13 additional morphs between these extremes were created for each of 16 models. The sample balance point represents the proportion of happy judgments scaled to the morph continuum.

Our primary measure of HIB on IBT was the “indifference point” which is the point on the happy-angry morph continuum (1–15) at which participants have 0.5 probability of judging a morph as angry. Lower values reflect tendencies to judge images as angry at lower anger expression intensity levels. The indifference point was estimated from a four-parameter logistic curve fit to a participant’s judgments of morphs ordered from happy to angry (Pollak & Kistler, 2002). An easily calculated, popular estimate of indifference point called “balance point” is the proportion of happy judgments scaled to the morph continuum (Figure 1). Balance point was an exploratory measure of HIB. Indifference and balance points are theoretically related and have a high correlation (r=.89, p<.001; see Stoddard et al. 2016).

IBT analyses were based on 376 individuals who had matching questionnaire data (SOM B), accuracy on the extreme morphs < 75%, and no response times ≥1 minute. Trials with response times > 3 seconds were excluded from analyses.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were done in R v.3.4.3 with packages psych v.1.8.4, GPArotation v. 2014.11–1, lme4 v.1.1–15, pvclust v.2.0–0, relaimpo v.2.2–3, and car v.3.0–0.

Exploratory bifactor analysis was conducted in package pscyh with the biquartimin rotation (Jennrich & Bentler, 2011) as implemented in psych and GPArotation. Fits used weighted least squares. All ARI, BITe, and CIS items were entered (no missing items). The general factor and 3 group factors were chosen as a limit. The first 6 eigenvalues were >1. The eigenvalues scree plot suggested that the most variance will be explained with 2–3 factors. More than three groups led to uninterpretable groupings. The general factor from the three-group solution was remarkably stable to modifications of the model. Vector cosine (e.g., Tucker index) was 1.00, between the final model general factor and the general factor from: higher group solutions, fit with maximum likelihood, and a confirmatory bifactor model. Factor scores were extracted using the Ten Berge method. The general factor scores were considered an individual’s degree of irritability, called “Irritability” hereafter.

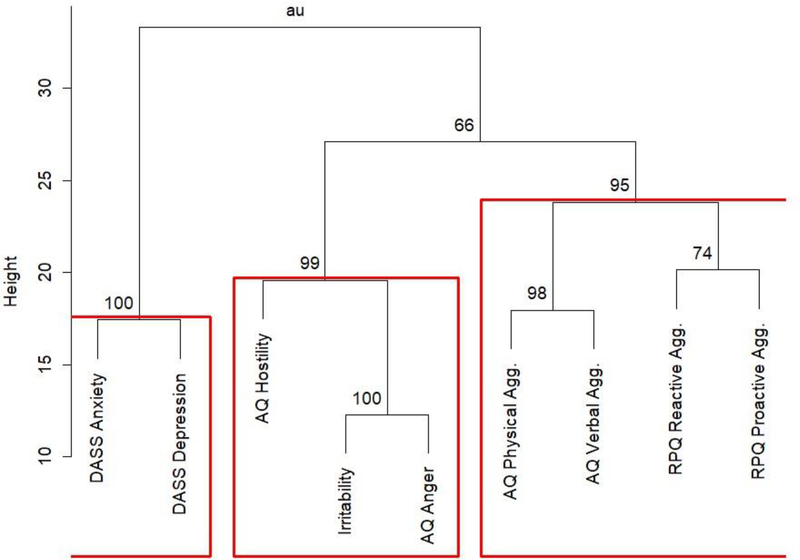

To examine the similarity between Irritability, aggression, anger, depression, and anxiety constructs, Irritability and individual subscale scores from the AQ, RPQ, and DASS were scaled and converted to a Euclidean distance matrix. These were subjected to Ward’s hierarchical clustering as implemented by (Murtagh & Legendre, 2014). This is a common method for empirically comparing similarity between measures. The method compares pairwise distances (similarity) between everyone’s scores on all measures. Starting with the assumption that all measures are equally dissimilar, the method progressively builds optimal groupings by testing all combinations of measure distances. Results are typically displayed with a dendrogram (Figure 2) which shows groupings (defined by a horizontal line, or edge) as a function of distance (height). Significant differences among groups were estimated via multiscale bootstrap resampling as implemented in pvclust.

Figure 2:

Cluster Dendrogram of Irritability Factor and Related Scales. Edge probability values (%) are approximate unbiased (au) estimates by multiscale bootstrapping (Shimodaira, 2004). Measures or lusters with a 95% or greater probability of grouping together are supported by the data, indicated by red boxes to reflect maximally inclusive groupings. Irritability=Irritability Factor from bifactor analysis; RPQ=Reactive and Proactive Aggression Questionnaire; DASS = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; AQ=Aggression Questionnaire.

Associations between Irritability and the RMET, IBT, and SIP-AEQ hostile attribution bias subscale were probed using linear regressions. Given our focus on Irritability and to account for collinearity among affective constructs, the following strategy was adopted for all analyses. Of the questionnaire-based measures, only Irritability was entered as a predictor. If a significant association with Irritability was found, relevant constructs based on prior literature/theory to the specific phenomenon were added to the regression model following a test of collinearity. For RMET, depression was added to the model. For measures of HIB, anxiety and reactive aggression were added. Anger was not included due to collinearity (variance inflation factor ≥ 4; see discussion). Depression was not included because it is associated with sad rather than hostile interpretation bias (Hirsch et al., 2016).

Age, vocabulary, gender, and the interactive effects of Irritability and gender were entered as additional predictors in the original models for RMET and SIP-AEQ variables. For IBT variables, we accounted for the random effects of face identity using a mixed effects model with the random participant characteristics (e.g., Irritability and age) nested in face identity. The fixed effects were the fully interactive effects of Irritability, gender, and the gender of the face stimulus. Age was a covariate. The R code for all models is in SOM D.

Results

Irritability in Self-Report Measures

Table 1 depicts the exploratory bifactor solution that had a good fit to the data (RMSE=0.066, 90%CI=.060–0.069, Tucker Lewis Index = 0.9). All items, except one CIS item, loaded onto the general (Irritability) factor with correlations >0.3. The Irritability factor explained 40% of response variance on all items. Items with the strongest Irritability factor loadings indicate increased sensitivity to provocation and towards temper loss.

Table 1:

Factor Structure

| Scale | Item | Irritability | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Communality (h2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BITe | Other people have been getting on my nerves | 0.73 | 0.46 | 0.76 | ||

| BITe | I have been feeling irritable | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.85 | ||

| BITe | I have been feeling like I might snap | 0.71 | 0.37 | 0.69 | ||

| BITe | Things have been bothering me more than they normally do | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.73 | ||

| BITe | I have been grumpy | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.76 | ||

| ARI | I often lose my temper | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.75 | ||

| ARI | I lose my temper easily | 0.69 | 0.43 | 0.68 | ||

| ARI | I get angry frequently | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.76 | ||

| ARI | I am easily annoyed by others | 0.67 | 0.21 | 0.55 | ||

| ARI | I stay angry for a long time | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.46 | ||

| ARI | I am angry most of the time | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.62 | ||

| CIS | I easily fly off the handle with those who don’t listen or understand | 0.79 | 0.63 | |||

| CIS | I am often in a bad mood | 0.76 | 0.72 | |||

| CIS | I often feel like a powder keg about to explode | 0.75 | 0.61 | |||

| CIS | I think I am rather touchy | 0.74 | 0.60 | |||

| CIS | It takes very little for things to bug me | 0.72 | 0.52 | |||

| CIS | Sometimes when I am angry I lose control over my actions | 0.66 | 0.53 | |||

| CIS | I can’t help being a little rude to people I don’t like | 0.63 | 0.49 | |||

| CIS | I don’t think I am a very tolerant person | 0.63 | 0.42 | |||

| CIS | Sometimes I shout, hit and kick and let off steam | 0.62 | 0.43 | |||

| CIS | Some people irritate me if they just open their mouth | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.71 | ||

| CIS | Sometimes people bother me just by being around | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.69 | ||

| CIS | It makes my blood boil to have somebody make fun of me | 0.60 | 0.45 | |||

| CIS | When I am irritated I can’t tolerate discussions | 0.60 | 0.42 | |||

| CIS | Sometimes I really want to pick a fight | 0.59 | 0.40 | |||

| CIS | When I am irritated I want to vent my feelings immediately | 0.55 | 0.37 | |||

| CIS | When someone raises his voice I raise mine higher | 0.51 | 0.34 | |||

| CIS | When I am tired I easily lose control | 0.51 | 0.28 | |||

| CIS | Whoever insults me or my family is looking for trouble | 0.47 | 0.38 | |||

| CIS | It is others who provoke my aggression | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.30 | ||

| CIS | When I am right, I am right | 0.16 | ||||

| Proportion of Variance | .40 | .06 | .05 | .04 | ||

Note: ARI=Affective Reactivity Index; CIS=Caprara Irritability Scale; BITe=Brief Irritability Test; Irritability=the general factor score generated from the bifactor analysis; Groups =group factors generated by the bifactor analysis.

The three Group factors explained a minority of response variance (15%). Groups 1 and 2 reflect either some facet of irritability or shared method variance represented by the BITe and ARI, respectively. Group 3 had the highest loadings from CIS items reflecting interpersonal sensitivity. Consistent with the hypothesis that all items reflect a latent structure representing irritability as understood by adults, the item with the highest communality was “I have been feeling irritable” from the BITe (h2=.85).

Bivariate associations between Irritability scores and other self-report scales are presented in SOM E. Irritability scores did not differ by gender, t(452)=0.58, p=0.56. Nonirritability scales with the highest associations with Irritability are the AQ-Anger (r=.83) and AQ-Hostility (r=.67), which empirically cluster with Irritability in Ward hierarchical clustering. At p<.05, aggression and affective items cluster together in separate groups apart from Irritability (Figure 2).

Face Emotion Identification

RMET performance was predicted by vocabulary and gender (increased accuracy in females), but not Irritability or the Irritability × Gender interaction (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors of RMET Performance

| Variable | Estimate | Standard Error | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 76.74 | 0.68 | 113.62*** |

| Irritability | 0.51 | 0.68 | 0.75 |

| Gender | −2.11 | 1.06 | −1.99* |

| Vocabulary | 1.58 | 0.15 | 10.43*** |

| Age | −.06 | 0.05 | −1.16 |

| Irritability × Gender | −1.54 | 1.05 | −1.47 |

| R2 | 0.22 | ||

| F5,445 | 24.55*** |

Note. N=451.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p < .001.

HIB during IBT

IBT indifference point (i.e., the point on the morph continuum where a participant has a 50% probability of making a happy or angry judgment) was negatively associated with irritability at a trend level (Table 3; p=.084).

Table 3.

Fixed Effects of IBT Indifference Point

| Variable | Estimate | Standard Error | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 8.05 | 0.21 | 38.24*** |

| Irritability | −0.20 | 0.12 | −1.74 |

| Gender | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.90 |

| Stimulus Genderŧ | 0.51 | 0.30 | 1.70 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.38 |

| Irritability × Gender | −0.04 | 0.18 | −0.22 |

| Irritability × Stimulus Gender | 0.17 | 0.17 | 1.04 |

| Gender × Stimulus Gender | −0.03 | 0.27 | −0.10 |

| Irritability × Gender × Stimulus Gender | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.54 |

Note. N=372.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p < .001.

refers to the gender of the face stimulus presented during the IBT.

IBT balance point (the proportion of happy judgments) was negatively associated with Irritability across models and adjusting for the participant and stimulus gender as well as age (Table 4; p=.032). When DASS-Anxiety and RPQ-Reactive Aggression were included, no terms were significant, though there was a trend towards a DASS-Anxiety by participant gender interaction (b=.06, se=0.3, p=.054).

Table 4.

Fixed Effects of IBT Balance Point

| Variable | Estimate | Standard Error | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 7.57 | 0.23 | 33.04*** |

| Irritability | −0.26 | 0.12 | −2.15* |

| Gender | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.33 |

| Stimulus Genderŧ | 0.39 | 0.33 | 1.19 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.84 |

| Irritability × Gender | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.95 |

| Irritability × Stimulus Gender | 0.21 | 0.18 | 1.17 |

| Gender × Stimulus Gender | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.16 |

| Irritability × Gender × Stimulus Gender | −0.08 | 0.27 | −0.29 |

Note. N=373.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p < .001.

refers to the gender of the face stimulus presented during the IBT.

HIB of Ambiguous Social Scenarios

Irritability (b=2.20, se=.41, p<.001) and vocabulary (b=−.50, se=.64, p<.001) predicted SIP-AEQ Hostile Attribution Bias scores. When DASS-Anxiety and RPQ-Reactive Aggression were entered, DASS-Anxiety, Irritability, and vocabulary were significant predictors (Table 5). Of R2=19.82%. In this model, Irritability explained 25.3%, DASS-Anxiety 33.2%, vocabulary 31.2%, and RPQ-Reactive Aggression 6.3%.

Table 5.

Predictors of SIP-AEQ Hostile Attribution Bias Scores

| Variable | Estimate | Standard Error | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −0.35 | 0.41 | −.86 |

| Irritability | 1.37 | 0.56 | 2.46* |

| Gender | 0.71 | 0.64 | 1.11 |

| Anxiety | 0.25 | 0.07 | 3.78*** |

| Reactive Aggression | 0.01 | 0.13 | −0.10 |

| Vocabulary | −0.47 | 0.09 | −5.23*** |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.24 |

| Irritability × Gender | −0.32 | 0.87 | −0.37 |

| Anxiety × Gender | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.69 |

| Reactive Aggression × Gender | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.86 |

| R2 | 0.20 | ||

| F9,444 | 12.37*** |

Note. N=454.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

Difficulties defining and differentiating irritability from related constructs has hampered understanding of this clinically significant symptom (Avenevoli et al., 2015; Toohey & DiGiuseppe, 2017). The present study provides empirical evidence for a single irritability factor representing increased sensitivity to provocation and temper loss that is significantly dissimilar from aggression, depression, and anxiety. It is associated with a greater tendency to interpret hostility in ambiguous social scenarios and make angry judgments of facial expressions. Unlike prior work in pathologically irritable children, we did not detect an effect of normative irritability in adults on face emotion identification or HIB of ambiguous faces. These findings advance the field by distinguishing irritability and reactive aggression and providing the first evidence for the unique effects of irritability, with respect to anxiety and reactive aggression, on hostile interpretations of face emotions and ambiguous scenarios. This has notable implications for mechanistic work in irritability. Hypotheses about irritability-related mechanisms may be informed by prior work on depression, anxiety, and aggression; however, direct tests of irritability are necessary since these constructs are not identical.

Irritability as an Increased Sensitivity to Provocation and Temper Loss

Difficulties distinguishing irritability from aggression, especially reactive aggression, depression and anxiety represent a significant challenge to the field of irritability (Avenevoli et al., 2015). The bifactor analysis identified a single irritability factor characterized by lowered thresholds for temper loss and experiencing negative mood, especially anger. Importantly, it was distinguished empirically from reactive aggression, depression, and anxiety. These findings join emerging empirical evidence distinguishing irritability and aggression in pediatric samples (Bolhuis et al., 2017; Van Meter et al., 2016) and support future investigations into irritability as a unique construct.

Irritability clustered with hostility and anger, with irritability most closely associated with the AQ Anger subscale. This is consistent with prior empirical work in personality and temperament which groups anger and irritability together as sub-constructs of negative emotionality/neuroticism (DeYoung et al., 2007; Rothbart, 2007; Shiner & Caspi, 2003). Further study of the relationship between irritability and the experience of anger are needed. The AQ Anger scale represents temper loss (e.g., “Sometimes I fly off the handle for no good reason”) and has item overlap with Caprara Irritability Scale (e.g., “I sometimes feel like a powder keg ready to explode”). This overlap may account for the lack of differentiation between measures and represents a study limitation. Future research using more precise measures of the experience, expression, and control of anger and their relationship to irritability are needed.

Irritability, Face Emotion Identification, and Hostile Interpretation Biases

Irritability was positively associated with HIB of ambiguous scenarios even after accounting for constructs independently associated with HIB (Crick & Dodge, 1996; De Castro et al., 2002; Penton-Voak et al., 2017). Both self-reported irritability and anxiety were uniquely associated with HIB. Although some HIB studies include anxiety as a covariate (Stoddard et al., 2016), others do not (Hiemstra, De Castro, & Thomaes, 2018; Maoz et al., 2016; Penton-Voak et al., 2013). Future research should ensure that irritability-related patterns do not reflect contributions of anxiety.

Irritability was not significantly related to the point on the morph continuum where the participant has a 50% probability of making either happy or an angry judgment. In an exploratory analysis, it was positively associated with the proportion of angry face judgments overall. This effect existed across face stimuli, accounting for the random effects of non-emotional features observed in a prior study (Stoddard et al., 2016). However, the association was undetectable once anxiety and reactive aggression were included. Accounting for random effects limited our power to detect significant effects and interactions of these constructs. Therefore, additional research into irritability and HIB in faces is needed.

Unlike prior work in children (Guyer et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2013; Rich et al., 2008), irritability was unrelated to face emotion identification. This may reflect Type II error or the possibility that face emotion identification impairments are limited to clinical or pediatric samples. Future work with adults with clinically significant irritability is necessary.

Limitations

Completion of the task online allowed us to recruit a large and diverse sample that contrasts with much of the published literature. However, individuals with higher irritability and aggression, low frustration tolerance, or different monetary incentives may have discontinued the study, limiting the generalizability of our findings (SOM B). In addition, the number of women in the sample exceeded the number of men. Although participant gender was included in all statistical models, it is possible that gender differences in face emotion identification processes (Hoffmann, Kessler, Eppel, Rukavina, & Traue, 2010; Montagne, Kessels, Frigerio, de Haan, & Perrett, 2005; Wirsen, Klinteberg, Levander, & Schalling, 1990) may have impacted our ability to detect associations between irritability and RMET performance.

We did not include all published irritability scales in our analyses. However, items from two commonly used scales (Born, Koren, Lin, & Steiner, 2008; Craig, Hietanen, Markova, & Berrios, 2008) were evaluated during the BITe development and did not improve the fit of the data (Holtzman et al., 2014). Therefore, while future work should replicate our findings using other irritability measures, the items considered in the present study represent a fairly comprehensive selection of existing measures.

Conclusion

Improved identification and treatment of irritability relies on clear definitions of this construct. The present study advances the field by providing empirical support for irritability as an increased sensitivity to provocation and temper loss that is dissimilar from related constructs and related to hostile interpretations of ambiguous stimuli.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by internal funds from Wellesley College to C.D. and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, (K23MH113731) to J.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: none

References

- Avenevoli S, Blader JC, & Leibenluft E (2015). Irritability in Youth: An Update. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(11), 881–883. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Hill J, Raste Y, & Plumb I (2001). The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(2), 241–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt BA, Talley A, Benjamin AJ, & Valentine J (2006). Personality and aggressive behavior under provoking and neutral conditions: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 751–777. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis K, Lubke GH, van der Ende J, Bartels M, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Lichtenstein P, … Tiemeier H (2017). Disentangling Heterogeneity of Childhood Disruptive Behavior Problems Into Dimensions and Subgroups. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(8), 678–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born L, Koren G, Lin E, & Steiner M (2008). A new, female-specific irritability rating scale. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience: JPN, 33(4), 344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Kircanski K, Stringaris A, Pine DS, & Leibenluft E (2017). Irritability in Youths: A Translational Model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 520–532. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16070839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman MA, Rich BA, Guyer AE, Lunsford JR, Horsey SE, Reising MM, … Leibenluft E (2010). Amygdala activation during emotion processing of neutral faces in children with severe mood dysregulation versus ADHD or bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(1), 61–69. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Cinanni V, Dimperio G, Passerini S, Renzi P, & Travaglia G (1985). Indicators of Impulsive Aggression - Present Status of Research on Irritability and Emotional Susceptibility Scales. Personality and Individual Differences, 6(6), 665–674. doi:10.1016/0191–8869(85)90077–7 [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Noblett KL, & McCloskey MS (2009). Attributional and emotional responses to socially ambiguous cues: validation of a new assessment of social/emotional information processing in healthy adults and impulsive aggressive patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(10), 915–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig KJ, Hietanen H, Markova IS, & Berrios GE (2008). The Irritability Questionnaire: a new scale for the measurement of irritability. Psychiatry Research, 159(3), 367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Dodge KA (1996). Social information-processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development, 67(3), 993–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Castro BO, Veerman JW, Koops W, Bosch JD, & Monshouwer HJ (2002). Hostile attribution of intent and aggressive behavior: A meta-analysis. Child Development, 73(3), 916–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demenescu LR, Kortekaas R, den Boer JA, & Aleman A (2010). Impaired Attribution of Emotion to Facial Expressions in Anxiety and Major Depression. PLoS One, 5(12). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CG, Quilty LC, & Peterson JB (2007). Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the big five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 880–896. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fite PJ, Raine A, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, & Pardini DA (2009). Reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent males: Examining differential outcomes10 years later in early adulthood. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(2), 141–157. doi: 10.1177/0093854809353051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, McClure EB, Adler AD, Brotman MA, Rich BA, Kimes AS, … Leibenluft E (2007). Specificity of facial expression labeling deficits in childhood psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(9), 863–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01758.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiemstra W, De Castro BO, & Thomaes S (2018). Reducing Aggressive Children’s Hostile Attributions: A Cognitive Bias Modification Procedure. Cognitive Therapy and Research. doi: 10.1007/s10608-018-9958-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch CR, Meeten F, Krahe C, & Reeder C (2016). Resolving Ambiguity in Emotional Disorders: The Nature and Role of Interpretation Biases. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 281–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann H, Kessler H, Eppel T, Rukavina S, & Traue HC (2010). Expression intensity, gender and facial emotion recognition: Women recognize only subtle facial emotions better than men. Acta Psychologica (Amst), 135(3), 278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman S, O’Connor B, Barata P, & Stewart DE (2014). A measure of irritability for use among men and women. Assessment. doi: 10.1177/1073191114533814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennrich RI, & Bentler PM (2011). Exploratory bi-factor analysis. Psychometrika, 76(4), 537–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P, Arizpe J, Rosen BH, Razdan V, Haring CT, Jenkins SE, … Leibenluft E (2013). Impaired fixation to eyes during facial emotion labelling in children with bipolar disorder or severe mood dysregulation. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 38(6), 407–416. doi: 10.1503/jpn.120232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond SH, & Lovibond PF (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety & stress scales (2nd ed.). Sydney, Australia: Psychology Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Maoz K, Adler AB, Bliese PD, Sipos ML, Quartana PJ, & Bar-Haim Y (2016). Attention and interpretation processes and trait anger experience, expression, and control. Cognition & Emotion, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1231663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagne B, Kessels RP, Frigerio E, de Haan EH, & Perrett DI (2005). Sex differences in the perception of affective facial expressions: do men really lack emotional sensitivity? Cognitive Processing, 6(2), 136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh F, & Legendre P (2014). Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: which algorithms implement Ward’s criterion? Journal of Classification, 31(3), 274–295. [Google Scholar]

- Penton-Voak IS, Munafo MR, & Looi CY (2017). Biased Facial-Emotion Perception in Mental Health Disorders: A Possible Target for Psychological Intervention? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(3), 294–301. doi: 10.1177/0963721417704405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penton-Voak IS, Thomas J, Gage SH, McMurran M, McDonald S, & Munafo MR (2013). Increasing recognition of happiness in ambiguous facial expressions reduces anger and aggressive behavior. Psychological Science, 24(5), 688–697. doi: 10.1177/0956797612459657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, & Kistler DJ (2002). Early experience is associated with the development of categorical representations for facial expressions of emotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(13), 9072–9076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Dodge K, Loeber R, Gatzke-Kopp L, Lynam D, Reynolds C, … Liu J (2006). The Reactive-Proactive Aggression Questionnaire: Differential Correlates of Reactive and Proactive Aggression in Adolescent Boys. Aggressive Behavior, 32(2), 159–171. doi: 10.1002/ab.20115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich BA, Grimley ME, Schmajuk M, Blair KS, Blair RJ, & Leibenluft E (2008). Face emotion labeling deficits in children with bipolar disorder and severe mood dysregulation. Development and Psychopathology, 20(2), 529–546. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler JJ, Wilmer JB, & Gauthier I (2017). General objective recognition is specific: Evidence from novel and familiar objects. Cognition, 166, 42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK (2007). Temperament, development, and personality. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(4), 207–212. doi:DOI 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00505.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savage J, Verhulst B, Copeland W, Althoff RR, Lichtenstein P, & Roberson-Nay R (2015). A genetically informed study of the longitudinal relation between irritability and anxious/depressed symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(5), 377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimodaira H (2004). Approximately unbiased tests of regions using multistep-multiscale bootstrap resampling. Annals of Statistics, 32(6), 2616–2641. doi: 10.1214/009053604000000823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner R, & Caspi A (2003). Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: Measurement, development, and consequences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44(1), 2–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard J, Scelsa V, & Hwang S (2018). Irritability and disruptive behaviors In Roy AK, Brotman MA, & Leibenluft E (Eds.), Irritability in pediatric psychopathology. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard J, Sharif-Askary B, Harkins EA, Frank HR, Brotman MA, Penton-Voak IS, … Leibenluft E (2016). An Open Pilot Study of Training Hostile Interpretation Bias to Treat Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R, Ferdinando S, Razdan V, Muhrer E, Leibenluft E, & Brotman MA (2012). The Affective Reactivity Index: a concise irritability scale for clinical and research settings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(11), 1109–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02561.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Zavos H, Leibenluft E, Maughan B, & Eley TC (2012). Adolescent irritability: phenotypic associations and genetic links with depressed mood. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(1), 47–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toohey MJ, & DiGiuseppe R (2017). Defining and measuring irritability: Construct clarification and differentiation. Clinical Psychology Review, 53, 93–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Meter A, Youngstrom E, Freeman A, Feeny N, Youngstrom JK, & Findling RL (2016). Impact of Irritability and Impulsive Aggressive Behavior on Impairment and Social Functioning in Youth with Cyclothymic Disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(1), 26–37. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Ribas P, Brotman MA, Salum GA, Kaiser A, Meffert L, Pine DS, … Stringaris A (2018). Deficits in emotion recognition are associated with depressive symptoms in youth with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Depression & Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.22810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkowski BM, & Robinson MD (2008). The cognitive basis of trait anger and reactive aggression: An integrative analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(1), 3–21. doi: 10.1177/1088868307309874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirsen A, Klinteberg BA, Levander S, & Schalling D (1990). Differences in Asymmetric Perception of Facial Expression in Free-Vision Chimeric Stimuli and Reaction-Time. Brain and Cognition, 12(2), 229–239. doi:Doi 10.1016/0278-2626(90)90017-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Farver JA, & Zhang Z (2009). Temperament, harsh and indulgent parenting, and Chinese children’s proactive and reactive aggression. Child Development, 80(1), 244–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.