Abstract

Background

Delirium is common after cardiac surgery and has been associated with morbidity, mortality, and cognitive decline. However, there are conflicting reports on the magnitude, trajectory, and domains of cognitive change that might be affected. We hypothesized that patients with delirium would experience greater cognitive decline at 1-month and 1-year after cardiac surgery compared to those without delirium.

Methods

Patients who underwent coronary artery bypass and/or valve surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass were eligible for this cohort study. Delirium was assessed using the Confusion Assessment Method. A neuropsychological battery was administered before surgery, at 1-month, and 1-year later. Linear regression was used to examine the association between delirium and change in composite cognitive Z-score from baseline to 1-month (primary outcome). Secondary outcomes were domain-specific changes at 1-month and composite and domain-specific changes at 1-year.

Results

The incidence of delirium in 142 patients was 53.5%. Patients with delirium had greater decline in composite cognitive Z-score at 1-month (greater decline by −0.29; 95%CI −0.54 to −0.05; p=0.020), and in the domains of visuoconstruction and processing speed. From baseline to 1-year, there was no difference between delirious and non-delirious patient in change in composite cognitive Z-score, although greater decline in processing speed persisted among the delirious patients.

Conclusions

Patients who developed delirium had greater decline in a composite measure of cognition and in visuoconstruction and processing speed domains at 1-month. The differences in cognitive change by delirium were not significant at 1-year, with the exception of processing speed.

INTRODUCTION

Delirium is a common complication after cardiac surgery that may occur in more than 50% of patients. 1 Delirium has been associated with long-term mortality, 2 perioperative morbidity, 3 increased duration of hospitalization, 4 and higher costs. 4 Delirium has further been associated with accelerated cognitive decline in a range of populations, including critically ill patients in the intensive care unit, 5 patients undergoing surgery, 6 and patients with dementia. 7 However, common methodological limitations to these reports, including insensitive delirium assessment, limited neuropsychological evaluation, and short follow-up, have restricted the characterization of the relationship between delirium and cognitive decline.

Postoperative cognitive change has been a subject of intense focus for patients undergoing surgery, particularly those undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). 8 A prior study in U.S. patients undergoing cardiac surgery identified delirium as an important risk factor for cognitive decline at 1-month, but not 1-year after cardiac surgery. 9 However, cognitive assessment was measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), a brief cognitive screening tool with known limitations. 10 A recent study using a more robust neuropsychological battery also found cognitive decline at 1-month but not 1-year among delirious patients using the Confusion Assessment Method 11 (CAM) and derivatives in a European cardiac surgery population. 12 In this study, the delirium incidence was substantially lower than in other studies, 1,9,13 due to either reduced sensitivity or operationalization of the delirium assessment. Our primary goal was to examine the association between delirium and cognitive change at 1-month after cardiac surgery in a U.S. population, using a sensitive delirium assessment and an expanded neuropsychological battery. As secondary outcomes, we also examined cognitive change at 1-year and domains of cognitive change at both time points. Our primary hypothesis was that delirium would be associated with decline in cognition at 1-month after cardiac surgery.

METHODS

IRB/Consent

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (Baltimore, MD) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. IRB approval of the parent study was granted on August 4, 2009. This manuscript adheres to the Strobe guidelines.

Study Design and Patients

This was a prospective observational study, nested in an ongoing trial that randomized patients to blood pressure targets during CPB based on cerebral autoregulation monitoring versus the usual practice where these targets are empirically chosen. 14,15 The parent trial was registered as NCT00981474. As the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the relationship between postoperative delirium and cognitive changes, and not to test hypotheses about blood pressure management during CPB, data from both groups were combined. Data on a portion of these patients have been reported previously in a paper examining hospital resources after delirium, but the primary hypothesis of this study has not previously been evaluated or reported. 4 Patients were included in this study if they were undergoing primary or re-operative coronary artery bypass (CAB) and/or surgery and/or aortic root surgery that required CPB and who were at high risk for neurologic complications (stroke or encephalopathy) as determined by a Johns Hopkins risk score composed of history of stroke, presence of carotid bruit, hypertension, diabetes, and age that generally excluded patients in the lowest quartile of risk. 16 Exclusion criteria were renal failure, hepatic dysfunction, non-English speaking, contraindications to MRI (e.g. pacemaker) and emergency surgery.

Perioperative Care

Patients received standard institutional monitoring, including radial arterial blood pressure monitoring. General anesthesia was induced with fentanyl, midazolam, and/or propofol and was maintained with isoflurane and a non-depolarizing muscle relaxant. Cardiopulmonary bypass was performed with a non-occlusive roller pump and a membrane oxygenator, and the circuit included a 40μm or smaller arterial line filter. Non-pulsatile flow was maintained between 2.1 – 2.4 L/min/m2. Patients were managed using alpha-stat pH management. Rewarming was based on institutional standards with a goal of maintaining nasal pharyngeal temperature < 37°C. After surgery, patients were sedated with a propofol infusion until they qualified for tracheal extubation or for 24 hours after surgery. Patients requiring more than 24 hours of mechanical ventilation received an infusion of fentanyl and/or midazolam.

Delirium Assessment (Primary Exposure) and Data Collection

Delirium was assessed using rigorous methodologies, including the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) 11 and CAM-ICU, 17 All research staff participating in delirium assessments were masked to randomization group in the parent study. The CAM assessment was performed in-person by formally trained research assistants and included a structured cognitive examination (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] 18, Digit Span Forwards/Backwards, and timed Months-of-the-Year Backwards). Research assistants also queried the patient, nurses, families, and medical records for evidence of delirium. Findings from this overall assessment were used to determine diagnosis of delirium. For intubated patients in the ICU, the validated CAM-ICU was used, which allows delirium assessment of non-verbal patients. For days on which patients could not be assessed in person due to either patient or staff availability, a validated chart review was used (sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 83%). 19 Coma was assessed using the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS), with a score of −4 or −5 indicating coma. Patients who were comatose on all assessments (regardless of sedation medication) were classified as having coma in this analysis.

The once-daily delirium assessments were limited to the first four postoperative days because of evidence that >90% of delirium occurs within this time. 20 For the analysis, delirium was defined as any CAM, CAM-ICU, or chart-review positive assessment during hospitalization.

Delirium assessors underwent formal training by a psychiatrist (KN), who is an expert in delirium diagnosis. Training included readings, videos, and delirium assessments of 10 patients with subsequent discussion. During the study, delirium assessors and the psychiatrist team member conducted co-ratings of patients every two weeks. Finally, research assistants met with delirium experts 1–2 times/month to discuss delirium assessments of non-study patients, to ensure consistent methods and judgment. During the study, we measured agreement among researchers and kappa statistics were between 0.7–0.8, which is consistent with substantial agreement. 4

Neuropsychological Battery

Neuropsychological testing was generally performed within 2 weeks of surgery and then 4–6 weeks and 1-year after surgery. The tests assessed a number of cognitive domains known to be affected by cardiac surgery. 21,22 The test battery consisted of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), 23 Rey Complex Figure Test (RCFT), 24 Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT), 25 Symbol Digits Modalities Test (SDMT), 26 Trail Making Tests A and B (TMT-A, TMT-B), 27 and Grooved Pegboard Test. 28 The tests were grouped into the following cognitive domains a priori by a neuropsychologist (VK : Attention (RAVLT I correct); Memory (RAVLT V correct, RAVLT IX correct); Visuoconstruction (RCFT copy trial score); Verbal Fluency (COWAT letters F, A, S); Processing Speed (SDMT correct, TMT-A); Executive Function (TMT-B), Fine Motor Speed (Grooved Pegboard dominant and non-dominant hand).

Statistical Analysis

The primary exposure was any positive delirium assessment. As a sensitivity analysis, we also added two patients who were comatose at all assessments and thus could not be assessed for delirium. The primary cognitive outcome was change in a composite cognitive Z-score from baseline to 1-month after surgery, as described and used previously by our group. 29,30 This score was obtained by first calculating Z-scores for individual tests at each testing time-point, using the mean and standard deviation(SD) of baseline tests of all patients in the parent study. Timed tests were multiplied by “−1” so that higher scores represented better performance. Next, individual test Z-scores were averaged at each time point and renormalized to generate a composite cognitive Z-score. Finally, the difference in composite Z-scores was calculated for each interval of interest. This method was also employed to calculate domain-specific cognitive scores, which we examined in exploratory analyses. Prior work has considered changes in composite Z-scores of 0.3–0.5 to be clinically significant based on epidemiologic data. 31,32

The sample size for this nested cohort study was determined by the number of patients with available delirium and cognitive assessments. Originally, we had calculated that 126 patients would be necessary to show a difference in change in composite cognitive Z-score from baseline to 1-month with 80% power, assuming an improvement in the non-delirious group of 0.1±0.4 and a decline in the delirious group of −0.1±0.4. Subsequently, in a post-hoc analysis using actual data, we also calculated that 126 patients would provide approximately 80% power to detect a difference in cognitive Z-score of 0.5 SD between delirium groups at 1-year.

Baseline patient characteristics were compared using Student t-tests, Wilcoxon rank sum tests, and chi-squared tests. Cognitive change was examined using linear regression. As advocated by others, 33 we did not account for learning effect or surgery, since we were interested in the difference between two groups of patients, both of whom underwent surgery and had the opportunity for learning effect. Accounting for learning effect may be most important with dichotomous cognitive outcomes, such as studies classifying patients according to a threshold of post-operative cognitive dysfunction. However, in our study, we examined continuous change in cognition without dichotomous categorizations. Variables for which to adjust were considered based on our review of the literature and prior to examining the data and included age, sex, race, education, and logistic EuroSCORE. We also examined characteristics from Table 1 for potential inclusion into the model, but did not include diabetes based on inclusion of potentially mediating effects in the logEuroSCORE. This analytic plan was based on prior methodology used by our research group 29 and was agreed upon prior to accessing the data. In the adjusted model with change in cognition as the outcome, we chose not to adjust for baseline cognitive scores due to the potential for bias that could be introduced. 34 We conducted a sensitivity analysis to account for missing 1-year follow-up cognitive data with multiple imputation using PROC MI in SAS (Carey, NC). Missing data (10 datasets) were imputed using age, gender, race, education, logEuroSCORE, and baseline and 1-month cognitive data. The regression model was fit using PROC MIANALYZE. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Entire Cohort (n=142) | No Delirium (n=66) | Delirium (n=76) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 70 (8) | 70 (7) | 70 (8) | 0.790a |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.096b | |||

| Male | 107 (75.4) | 54 (81.8) | 53 (69.7) | |

| Female | 35 (24.6) | 12 (18.2) | 23 (30.3) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.407d | |||

| Caucasian | 115 (81.0) | 56 (84.9) | 59 (77.6) | |

| African-American | 19 (13.4) | 8 (12.1) | 11 (14.5) | |

| Other | 8 (5.6) | 2 (3.0) | 6 (7.9) | |

| Education (years), median (IQR) | 16 (12–17) | 16 (12–17) | 16 (12–17) | 0.612c |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Prior stroke | 18 (13.0) | 9 (14.3) | 9 (12.0) | 0.691b |

| Hypertension | 132 (93.0) | 60 (90.9) | 72 (94.7) | 0.374b |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 34 (23.9) | 16 (24.2) | 18 (23.7) | 0.938b |

| Myocardial Infarction | 39 (27.5) | 18 (27.3) | 21 (27.6) | 0.962b |

| COPD | 11 (7.8) | 4 (6.2) | 7 (9.2) | 0.546d |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | 30 (21.3) | 15 (23.1) | 15 (19.7) | 0.629b |

| Tobacco (current) | 11 (7.8) | 5 (7.7) | 6 (7.9) | 0.964b |

| Diabetes | 64 (45.1) | 24 (36.4) | 40 (52.6) | 0.0520b |

| Anemia | 60 (42.6) | 28 (42.4) | 32 (42.7) | 0.977b |

| Logistic EuroSCORE, median (IQR) | 4.5 (2.3–9.0) | 4.3 (2.2–7.3) | 4.8 (2.5–10.4) | 0.196c |

| Surgery, n (%) | 0.408d | |||

| CAB | 66 (46.5) | 29 (43.9) | 37 (48.7) | |

| CAB +Valve | 24 (16.9) | 10 (15.2) | 14 (18.4) | |

| Valve | 50 (35.2) | 27 (40.9) | 23 (30.3) | |

| Other | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.6) | |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass duration (min), median (IQR) | 115 (89–146) | 118 (90–145) | 114 (85.5–153.5) | 0.872c |

| Aortic cross-clamp duration (min), median (IQR) | 73 (57–94) | 72.5 (59–91) | 73 (53–100) | 0.995c |

| Baseline Depression Score, median (IQR) | 7 (3–11) | 5 (3–10) | 8 (4–11) | 0.157c |

Abbreviations: SD= standard deviation; IQR=Inter-Quartile Range; COPD= chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CAB=coronary artery bypass

P-values are calculated by t-test.

P-values are calculated by chi-square test.

P-values are calculated by Wilcoxon rank sum test.

P-values are calculated by fisher exact test.

RESULTS

Patients

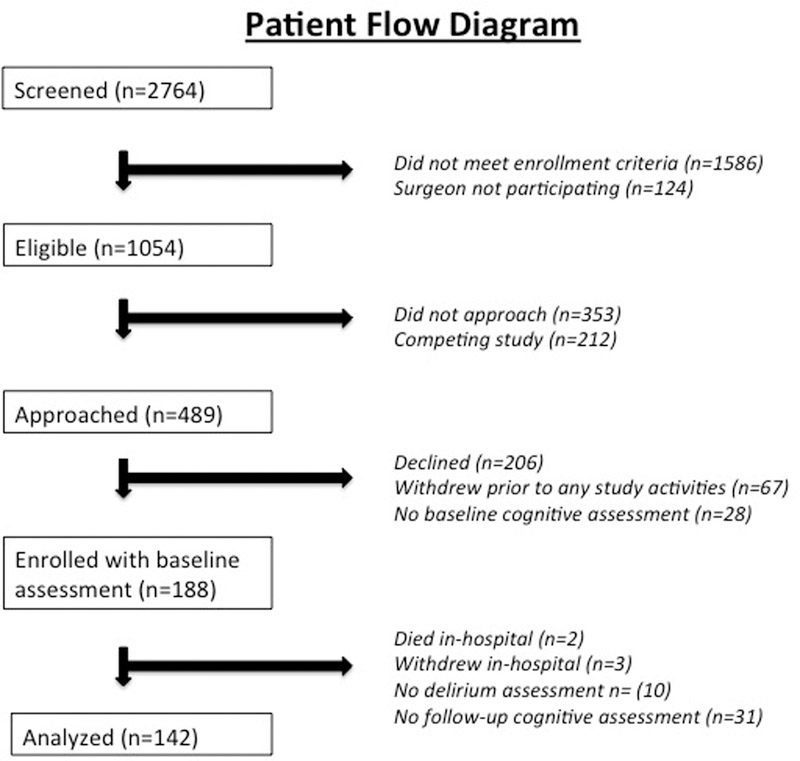

Data were available from 142 patients with delirium assessments and neuropsychological testing. Figure 1 shows a patient flow diagram. The number of patients completing follow-up neuropsychological testing at 1-month was 140 and at 1-year was 108. The reasons for missing follow-up testing at 1-month were patient refusal (2), and at 1-year were study withdrawal (13), lost to follow-up (20, of which 10 were subsequently noted to be alive at the time of 1-year follow-up), and death (1). Delirium was diagnosed in 76 (53.5%) patients. CAM assessments were performed in 69% of assessments, with the remaining being comatose (1.4%) or assessed with CAM-ICU (3%) or chart review (27%). The characteristics of patients by delirium status are shown in Table 1. The mean±SD age of the patients was 70±8 years, 75% were male and 81% Caucasian. Notably, there was no difference in patient age between patients with and without delirium. Patients with delirium had a lower composite cognitive Z-score (mean±SD) at baseline (−0.19±0.92) compared with patients who did not develop delirium (0.20±1.09; p=0.025). Delirium incidence was not different among patients with available cognitive data at 1-year (53% [57/108]) compared with those patients missing data at 1-year (56% [19/34]; p=0.752).

Figure 1:

Patient Flow Chart

Composite Cognitive Z-Scores

Baseline and follow-up

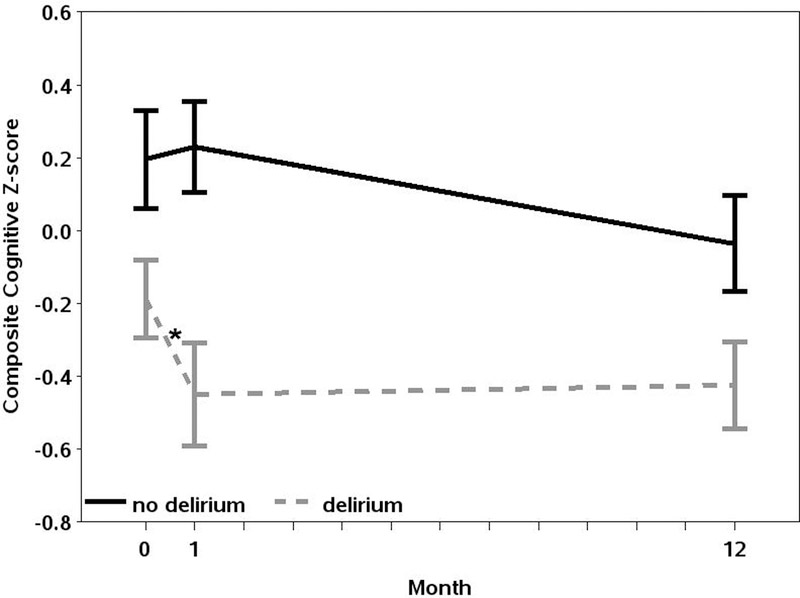

Composite cognitive Z-scores by delirium status at baseline, 1-month, and 1-year after surgery are shown in Table 2 and graphically in Figure 2. As expected, composite cognitive Z-scores were lower in patients with delirium compared to without delirium at all individual timepoints: baseline (−0.19±0.92 vs. 0.20±1.09; p=0.025), 1-month (−0.45±1.21 vs. 0.23±1.01, p<0.001), and 1-year after surgery (−0.42±0.90 vs. −0.04±0.94; p=0.033).

TABLE 2:

Composite cognitive Z-scores and interval changes in scores at baseline, 1-month, and 1-year after surgery

| All Patients (n=142) | No Delirium (n=66) | Delirium (n=76) | Difference between Delirium Groups* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-coefficient | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| Cognitive Z-score, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Baseline (n=142) | −0.009 (1.02) | 0.20 (1.09) | −0.19 (0.92) | −0.34 | −0.64, −0.04 | 0.025 |

| 1-month (n=140) | −0.13 (1.17) | 0.23 (1.01) | −0.45 (1.21) | −0.67 | −1.01, −0.33 | <0.001 |

| 1-year (n=108) | −0.24 (0.94) | −0.04 (0.94) | −0.42 (0.90) | −0.36 | −0.69, −0.03 | 0.033 |

| Change in cognitive Z-score, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Baseline to1-month (n=140) | −0.11 (0.72) | 0.035 (0.46) | −0.23 (0.87) | −0.29 | −0.54, −0.05 | 0.020 |

| Baseline to 1-year (n=108) | −0.33 (0.62) | −0.27 (0.54) | −0.39 (0.67) | −0.13 | −0.37, 0.11 | 0.298 |

| 1-month to 1-year (n=106) | −0.22 (0.66) | −0.28 (0.48) | −0.15 (0.80) | 0.13 | −0.14, 0.39 | 0.348 |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, logistic EuroSCORE

Figure 2:

Composite Cognitive Z-scores by Delirium Status at Baseline, 1-Month, and 1-Year after Cardiac Surgery. Error bars refer to standard deviation. There is a significant difference in decline from baseline to 1-month in patients with delirium compared to patients without delirium as indicated by the “*”.

Change in cognitive scores

However, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, the decline in composite cognitive Z-score from baseline to 1-month after surgery was greater among patients with delirium compared to patients without delirium (greater decline by −0.29; 95%CI −0.54 to −0.05; p=0.02). This model was adjusted for age (−0.002, 95%CI −0.02 to 0.02; p=0.818), sex (male vs. female: 0.009; 95%CI −0.29 to 0.31; p=0.951), race (black vs. white: −0.15; 95%CI −0.53 to 0.22; p=0.422, other vs. white: 0.13; 95%CI −0.41 to 0.66; p-value 0.638), education (>16 years vs. <12 years: 0.15; 95%CI −0.49 to 0.80; p-value 0.634, 12–16 years vs. <12 years: 0.30; 95%CI −0.32 to 0.91; p=0.342), and logistic EuroSCORE (0.008; 95%CI −0.01 to 0.03; p=0.444). On the other hand, from baseline to 1-year after surgery, there was no difference in adjusted decline from baseline in composite cognitive Z-score by delirium status (p=0.298). Using multiple imputation to account for missing cognitive data predominantly at 1-year, we found similar results, with delirious patients having greater cognitive decline at 1-month (−0.29; 95%CI −0.52 to −0.06; p=0.015) but not at 1-year (−0.11; 95%CI −0.33 to 0.12; p=0.14). Because cognitive change is non-linear during the first year after surgery, we also examined cognitive change from 1-month to 1-year and found no difference by delirium status. In a sensitivity analysis, we found no change in the results if patients with coma were included in the delirium group.

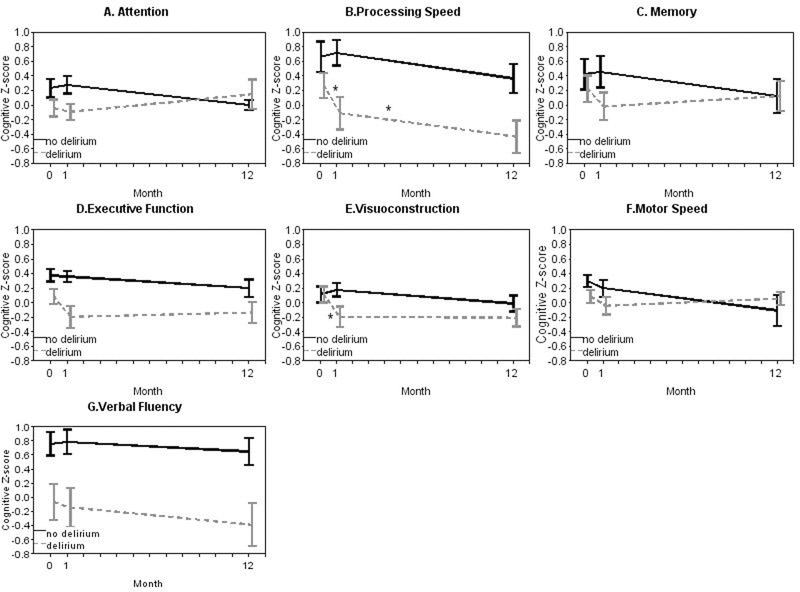

Domain-specific cognitive Z-scores

Domain-specific cognitive Z-scores by delirium status were examined in exploratory analysis and are shown at baseline, 1-month, and 1-year after surgery in Table 3 and Figure 3. Visual inspection of domain-specific trajectories of cognitive Z-scores generally demonstrated a decline across domains from baseline to 1-month. However, adjusted decline was only greater in the delirium compared to the non-delirium group in the domains of visuoconstruction (greater decline by −0.45; 95%CI −0.78 to −0.13; p=0.007) and processing speed (greater decline by −0.53; 95%CI −0.96 to −0.09; p=0.018). From baseline to 1-year, adjusted decline in the domain of processing speed was greater in the delirium group compared to the non-delirium group (greater decline by −0.58; 95%CI −0.95 to −0.22; p=0.002). There were no other cognitive domains that showed differences in cognitive trajectories from baseline to 1-year by delirium status. There were also no statistical differences in recovery of cognition from 1-month to 1-year by delirium status. The predominant pattern from 1-month to 1-year was greater recovery in the delirium group, with the exception of the domains of processing speed and verbal fluency, which did not fit this general pattern and showed similar trajectories between the delirium and non-delirium groups.

Table 3:

Domain-specific cognitive Z-scores and interval changes in scores at baseline, 1-month, and 1-year after surgery

| No Delirium (n=66) | Delirium (n=76) | Difference between Delirium Groups* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-coefficient | 95% CI | p-value | |||

| Attention | |||||

| Cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline | 0.23 (1.05) | −0.04 (1.00) | −0.28 | −0.61, 0.05 | 0.095 |

| 1-month | 0.28 (0.97) | −0.09 (0.96) | −0.40 | −0.72, −0.08 | 0.015 |

| 1-year | −0.0001 (0.48) | 0.15 (1.50) | 0.20 | −0.24, 0.64 | 0.360 |

| Change in cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline to 1-month | 0.05 (0.94) | −0.02 (1.05) | −0.09 | −0.43, 0.26 | 0.621 |

| Baseline to 1-year | −0.32 (0.74) | 0.06 (1.67) | 0.49 | −0.01, 1.00 | 0.056 |

| 1-month to 1-year | −0.22 (0.71) | 0.22 (1.60) | 0.49 | −0.007, 0.98 | 0.053 |

| Memory | |||||

| Cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline | 0.42 (1.70) | 0.23 (1.55) | −0.29 | −0.83, 0.24 | 0.284 |

| 1-month | 0.46 (1.74) | −0.02 (1.61) | −0.52 | −1.06, 0.02 | 0.060 |

| 1-year | 0.12 (1.69) | 0.12 (1.52) | −0.04 | −0.68, 0.59 | 0.889 |

| Change in cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline to 1-month | 0.03 (1.04) | −0.24 (1.35) | −0.22 | −0.64, 0.20 | 0.294 |

| Baseline to 1-year | −0.36 (1.60) | −0.33 (1.33) | 0.06 | −0.54, 0.65 | 0.846 |

| 1-month to 1-year | −0.30 (1.32) | −0.02 (1.36) | 0.26 | −0.28, 0.80 | 0.335 |

| Visuoconstruction | |||||

| Cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline | 0.11 (0.88) | 0.11 (0.92) | 0.08 | −0.20, 0.35 | 0.579 |

| 1-month | 0.18 (0.75) | −0.19 (1.19) | −0.37 | −0.70, −0.04 | 0.025 |

| 1-year | −0.01 (0.75) | −0.21 (0.92) | −0.13 | −0.45, 0.19 | 0.427 |

| Change in cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline to 1-month | 0.08 (0.86) | −0.35 (0.96) | −0.45 | −0.78, −0.13 | 0.007 |

| Baseline to 1-year | −0.13 (0.76) | −0.37 (0.78) | −0.23 | −0.54, 0.08 | 0.142 |

| 1-month to 1-year | −0.21 (0.87) | −0.15 (0.77) | 0.09 | −0.24, 0.42 | 0.608 |

| Verbal Fluency | |||||

| Cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline | 0.93 (2.71) | −0.07 (2.22) | −0.90 | −1.71, −0.08 | 0.031 |

| 1-month | 0.96 (2.80) | −0.14 (2.36) | −1.01 | −1.84, −0.17 | 0.019 |

| 1-year | 0.84 (2.78) | −0.39 (2.30) | −1.13 | −2.12, −0.14 | 0.026 |

| Change in cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline to 1-month | 0.03 (1.44) | −0.03 (1.63) | −0.06 | −0.60, 0.47 | 0.814 |

| Baseline to 1-year | −0.33 (1.76) | −0.54 (1.66) | −0.22 | −0.91, 0.46 | 0.523 |

| 1-month to 1-year | −0.40 (1.55) | −0.37 (1.72) | 0.01 | −0.66, 0.68 | 0.976 |

| Processing Speed | |||||

| Cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline | 0.66 (1.69) | 0.27 (1.42) | −0.30 | −0.73, 0.13 | 0.174 |

| 1-month | 0.72 (1.40) | −0.11 (1.87) | −0.83 | −1.36, −0.31 | 0.002 |

| 1-year | 0.37 (1.40) | −0.43 (1.66) | −0.76 | −1.29, −0.22 | 0.006 |

| Change in cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline to 1-month | 0.06 (0.81) | −0.42 (1.51) | −0.53 | −0.96, −0.09 | 0.018 |

| Baseline to 1-year | −0.19 (0.93) | −0.82 (0.98) | −0.58 | −0.95, −0.22 | 0.002 |

| 1-month to 1-year | −0.38 (0.96) | −0.52 (1.01) | −0.13 | −0.53, 0.27 | 0.519 |

| Executive Function | |||||

| Cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline | 0.37 (0.67) | 0.09 (0.87) | −0.24 | −0.48, 0.01 | 0.063 |

| 1-month | 0.36 (0.58) | −0.19 (1.22) | −0.51 | −0.83, −0.19 | 0.002 |

| 1-year | 0.20 (0.86) | −0.13 (1.04) | −0.37 | −0.72, −0.01 | 0.044 |

| Change in cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline to 1-month | −0.03 (0.41) | −0.23 (0.86) | −0.18 | −0.42, 0.06 | 0.139 |

| Baseline to 1-year | −0.12 (0.55) | −0.32 (0.90) | −0.24 | −0.54, 0.07 | 0.127 |

| 1-month to 1-year | −0.11 (0.60) | −0.19 (0.89) | −0.14 | −0.44, 0.17 | 0.380 |

| Motor Speed | |||||

| Cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline | 0.30 (0.63) | 0.09 (0.70) | −0.23 | −0.46, 0.01 | 0.065 |

| 1-month | 0.20 (0.90) | −0.04 (0.89) | −0.23 | −0.57, 0.11 | 0.189 |

| 1-year | −0.11 (1.42) | 0.06 (0.60) | 0.17 | −0.26, 0.59 | 0.435 |

| Change in cognitive Z-score | |||||

| Baseline to 1-month | −0.08 (0.53) | −0.13 (0.63) | −0.07 | −0.31, 0.17 | 0.558 |

| Baseline to 1-year | −0.16 (0.48) | −0.07 (0.47) | 0.04 | −0.17, 0.25 | 0.714 |

| 1-month to 1-year | −0.22 (1.00) | 0.01 (0.54) | 0.28 | −0.06, 0.62 | 0.110 |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, logEUROScore

Figure 3:

Domain-Specific Cognitive Z-scores by Delirium Status at Baseline, 1-Month, and 1-Year after Cardiac Surgery. Error bars refer to standard deviation. There is a significant difference, indicated by the “*” in decline in the domains of processing speed and visuoconstruction from baseline to 1-month, and in the domain of processing speed from baseline to 1-year, in patients with delirium compared to patients without delirium.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate that patients with delirium have greater decline from baseline in a composite measure of cognitive function 1-month after surgery compared to patients without delirium. In exploratory analysis, the domains of psychomotor speed and visuoconstruction were most negatively affected by the presence of postoperative delirium. One-year after surgery, patients with delirium had a greater decline in processing speed compared to patients without delirium. There were no differences in decline from baseline in any other specific cognitive domain, or in the composite measure of cognitive function, by delirium status at 1-year after surgery.

Our results from this study support findings from other studies suggesting that delirium after surgery is associated with non-linear changes in postoperative cognition. 9,35 In particular, delirium appears to be associated with “delayed neurocognitive recovery”, a term used in new nomenclature to describe early postoperative cognitive change. 36 Interestingly, non-linear changes in cognition after cardiac surgery have been consistently described over the past two decades, 8,37 most prominently by Newman et al. who reported an incidence of cognitive decline of 24% at 6-months and 42% at 5-years after cardiac surgery. 8 Our results add to this literature by clarifying a role for delirium in explaining heterogeneity in cognitive trajectories. In particular, our results confirm the results of Sauer et al. 12 who examined a European cohort of patients undergoing cardiac surgery using a robust neuropsychological battery. These investigators found that patients with delirium had greater cognitive decline at 1-month, but not 1-year after cardiac surgery compared to patients without delirium. Importantly, the incidence of delirium was only 12.5% in their study, likely due to operationalization of the delirium assessment and/or reduced sensitivity. 38 Our study extends the results of Sauer et al. by using a more sensitive delirium examination and showing similar findings. Thus, the association of delirium and postoperative cognitive change is not limited to the most severe or clinically obvious forms of delirium, an observation that emphasizes the importance of screening for and preventing even mild cases of postoperative delirium.

Saczynski et al. 9 also reported in a study of 225 patients cardiac surgery patients that cognitive decline measured with MMSE was greater among patients with delirium in the weeks to months after surgery compared to patients without delirium. By 1-year there was recovery of MMSE scores in each group, with the delirium group still having lower scores (p=0.06). Although frequently used as a global measure of cognitive function, there is no ideal cognitive test for all populations, and the MMSE can be limited by a ceiling effect (i.e. it may not detect cognitive decline in patients who are high-performing at baseline), limited sensitivity to change in some populations, and limited ability to examine specific cognitive domains. 10 In this study, the incidence of delirium was 46% (similar to the incidence in our study). The consistency of our results, and those of Saczynski et al. 9 and Sauer et al., 12 demonstrate that the association of delirium and cognitive change is robust to heterogeneous methods of delirium and cognitive assessment. Furthermore, in a non-cardiac surgery population screened for delirium using clinical tools, delirium was associated with a greater likelihood of developing mild cognitive impairment or dementia at follow-up. 39

It is important to note however, that the association between delirium and cognitive decline has not been consistent across all studies and surgical populations. For example, in a secondary analysis of 850 patients from Franck et al., 40 delirium after non-cardiac surgery did not affect the incidence of POCD at 1-week and 3-months follow-up, although delirium in the immediate post-anesthesia period and within 7 days was associated with worse cognitive outcomes. In this study, POCD was classified as a binary diagnosis, which may have limited the power to detect a difference between groups and contributed to the negative results of the study.

The majority of studies assessing the effects of postoperative delirium on cognition have followed patients only to 1-year after surgery. However, participants enrolled in the SAGES study 35 underwent neuropsychological testing up to 3-years postoperatively. In that non-cardiac surgery population, a similar biphasic pattern in cognition was seen with steeper cognitive decline in patients with delirium from baseline to 1-month compared to patients without delirium. At 1-year, there was recovery in both groups with no difference in cognitive decline by delirium status. Subsequently, slopes of cognitive change diverged, with delirious patients having accelerated cognitive decline. These results suggest that it may be important to measure cognitive outcomes longer than 1-year after surgery, and thus our findings of no difference in cognition at 1-year by delirium group cannot be extrapolated to longer-term outcomes..

Understanding the mechanism for associations between delirium and cognitive decline is critically important, and several possibilities exist. Delirium might be a “stress test” for the brain identifying patients at high risk for subsequent cognitive decline and who might benefit from rehabilitation strategies. Obtaining preoperative cognitive trajectories would help illuminate this question; however, these data are difficult to obtain prior to surgery. In hospitalized patients with dementia, longitudinal studies of cognition have shown accelerated cognitive decline after delirium, suggesting a potential contribution from delirium.7

Another explanation for the relationship between delirium and cognitive decline is that perioperative insults may contribute independently to both delirium and longer-term cognitive decline. For example, neuroinflammation 41,42 and changes in cerebral blood flow 43,44 have been hypothesized to contribute to short and long-term brain dysfunction, and provide plausible mechanisms for the observed findings of this and other studies. 45 Finally, the ramifications of delirium (such as decreased mobility 46 or altered sleep-wake cycles 47) might lead to subsequent cognitive change. Understanding the pathophysiologic basis for the observed association between delirium and cognitive decline will be crucial for developing targeted strategies for treatment and prevention.

Our findings of differences in the specific cognitive domains are exploratory but may be hypothesis-generating for future studies. Processing speed is an important component of cognitive tasks which are critical to navigate the post-surgical recovery period. Impairments in processing speed have been correlated with impaired functional status, 48 including activities of daily living such as managing finances, nutrition, and medications. 49 Observational studies have suggested that delirium is associated with changes in white matter integrity, 50 and further that white matter integrity is associated with measures of processing speed, 51 thus providing a potential mechanistic hypothesis for our observed results. The changes in processing speed may also suggest a sub-cortical injury consequence from delirium. In contrast, there were no differences by delirium status in memory or attention, which may involve more cortical processes. These findings may influence the design of future neuroimaging and molecular imaging studies to examine mechanisms for cognitive decline after delirium. Visuoconstruction refers to the coordination of fine motor skills with spatial abilities, and may substantially impact tasks such as driving and writing. 52 Our findings may be particularly important for older adults, in whom the preservation of these tasks is critically important. Interestingly, our findings corroborate those of prior results 8 which demonstrated short-term decline in domains of processing speed and visuoconstruction after cardiac surgery and suggest that delirium may provide one explanation.

Strengths of this study include rigorous assessment of delirium and a comprehensive neuropsychological battery with assessment of domain-specific change. As a sensitivity analysis, we also examined coma and delirium together to account for the contribution of severe brain dysfunction, in accord with prior methodology. 53 We were able to adjust for several important confounding variables. However, there are limitations to consider in interpreting the results. First, the study was observational by necessity, which makes it difficult to attribute causality, and further studies are needed to assess the extent to which the relationship between delirium and cognitive change reflects association, mediation, or causation. Second, we did not measure cognitive trajectories prior to surgery, so cannot exclude that delirious patients were already declining in cognition. Third, our delirium methods are generally sensitive, so may identify cases of delirium that would not be clinically evident. Fourth, we followed patients up to 1-year after surgery but do not have cognitive data at later time points. Our sample size may also be underpowered to detect differences by group smaller than 0.5 SD at 1-year. Finally, our analyses with regard to domains of cognition are exploratory given the multiple comparisons and should be considered hypothesis-generating.

The results of this study support a growing body of literature suggesting that delirium is associated with cognitive decline 1-month after cardiac surgery. Preservation of cognitive status in the weeks to months after cardiac surgery is an important patient-centered goal to facilitate prompt return to pre-surgical functional status, such as living independently with normal social engagement. With the exception of processing speed, there is recovery to normal in most cognitive domains by 1 year after surgery. Further studies are needed to clarify longer-term cognitive outcomes and to elucidate mechanisms for these findings in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

6. Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Core within the Department of Anesthesiology & Critical Care Medicine, the Johns Hopkins Center on Aging and Health, and the Older Americans Independence Center for contributions to this manuscript.

10. Funding

CB: Supported by grants from: NIH/NIA (K-76 AG057020, K23 AG051783), International Anesthesia Research Society, Johns Hopkins Clinician Scientist Award, Older Americans Independence Center Research Career Development Award (P30 AG021334).

VK: Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (KL2TR001077)

Footnotes

11. Conflicts of Interest

CB: Consulted for and received grant support from Medtronic in unrelated areas

KN: Has received research funding from Hitachi Medical Corporation

YN: Has received funding from Medtronic in unrelated areas

CH: Consulted for and received grant support from Medtronic in unrelated areas

4. Clinical Trial Number

N/A

5. Prior Presentations

The association of delirium and cognitive change was examined in a small number of patients and presented as an abstract at the 2014 meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. The abstract was selected for the session “Best Abstracts: Clinical Science”. Presented 10/14/2014 in New Orleans, LA

9. Summary Statement: Does not appear to be applicable for this category of manuscript

REFERENCES

- 1.Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Levkoff SE, Rockett C, Inouye SK, Sellke FW, Khuri SF, Lipsitz LA, Ramlawi B, Levitsky S, Marcantonio ER. Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2009;119(2):229–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottesman RF, Grega MA, Bailey MM, Pham LD, Zeger SL, Baumgartner WA, Selnes OA, McKhann GM. Delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery and late mortality. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(3):338–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin BJ, Buth KJ, Arora RC, Baskett RJ. Delirium as a predictor of sepsis in post-coronary artery bypass grafting patients: A retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2010;14(5):R171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown CH 4th, Laflam A, Max L, Lymar D, Neufeld KJ, Tian J, Shah AS, Whitman GJ, Hogue CW. The impact of delirium after cardiac surgical procedures on postoperative resource use. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(5):1663–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, Brummel NE, Hughes CG, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani AK, Moons KG, Geevarghese SK, Canonico A, Hopkins RO, Bernard GR, Dittus RS, and Ely EW for the BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(2):185–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacLullich AM, Beaglehole A, Hall RJ, Meagher DJ. Delirium and long-term cognitive impairment. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(1):30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross AL, Jones RN, Habtemariam DA, Fong TG, Tommet D, Quach L, Schmitt E, Yap L, Inouye SK. Delirium and long-term cognitive trajectory among persons with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1324–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newman MF, Kirchner JL, Phillips-Bute B, Gaver V, Grocott H, Jones RH, Mark DB, Reves JG, Blumenthal JA, Neurological Outcome Research Group and the Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology Research Endeavors Investigators. Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(6):395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, Fong TG, Gross A, Inouye SK, Jones RN. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):30–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devenney E, Hodges JR. The mini-mental state examination: Pitfalls and limitations. Pract Neurol. 2017;17(1):79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: The confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauer AC, Veldhuijzen DS, Ottens TH, Slooter AJC, Kalkman CJ, van Dijk D. Association between delirium and cognitive change after cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119(2):308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudolph JL, Inouye SK, Jones RN, Yang FM, Fong TG, Levkoff SE, Marcantonio ER. Delirium: An independent predictor of functional decline after cardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):643–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brady K, Joshi B, Zweifel C, Smielewski P, Czosnyka M, Easley RB, Hogue CW Jr. Real-time continuous monitoring of cerebral blood flow autoregulation using near-infrared spectroscopy in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Stroke. 2010;41(9):1951–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshi B, Ono M, Brown C, Brady K, Easley RB, Yenokyan G, Gottesman RF, Hogue CW. Predicting the limits of cerebral autoregulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(3):503–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKhann GM, Grega MA, Borowicz LM Jr, Bechamps M, Selnes OA, Baumgartner WA, Royall RM. Encephalopathy and stroke after coronary artery bypass grafting: Incidence, consequences, and prediction. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(9):1422–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Dittus R, Speroff T, Gautam S, Bernard GR, Inouye SK. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: Validation of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1370–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inouye SK, Leo-Summers L, Zhang Y, Bogardus ST Jr, Leslie DL, Agostini JV. A chart-based method for identification of delirium: Validation compared with interviewer ratings using the confusion assessment method. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson TN, Raeburn CD, Tran ZV, Angles EM, Brenner LA, Moss M. Postoperative delirium in the elderly: Risk factors and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2009;249(1):173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Dijk D, Keizer AM, Diephuis JC, Durand C, Vos LJ, Hijman R. Neurocognitive dysfunction after coronary artery bypass surgery: A systematic review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;120(4):632–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stump DA. Selection and clinical significance of neuropsychologic tests. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59(5):1340–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell JB, Cripe LI, Dodrill CB. Assessment of brain impairment with the rey auditory verbal learning test: A comparison with other neuropsychological measures. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1991;6(4):241–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyers JE, Meyers KR. Rey complex figure test under four different administration procedures. Clin Neuropsychol 1995;9(1):63–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lezak M Neuropsychological Assessment. New York, Oxford University Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reitan R, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. Tucson, AZ, Neuropsychology Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costa LD, Vaughan HG Jr., Levita E, Farber N. Purdue Pegboard as a predictor of the presence and laterality of cerebral lesions. J Consult Psychol 1963; 27: 133–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown CH 4th, Morrissey C, Ono M, Yenokyan G, Selnes OA, Walston J, Max L, LaFlam A, Neufeld K, Gottesman RF, Hogue CW. Impaired olfaction and risk of delirium or cognitive decline after cardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(1):16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selnes OA, Grega MA, Borowicz LM Jr, Royall RM, McKhann GM, Baumgartner WA. Cognitive changes with coronary artery disease: A prospective study of coronary artery bypass graft patients and nonsurgical controls. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(5):1377–84; discussion 1384–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKhann GM, Goldsborough MA, Borowicz LM Jr, Selnes OA, Mellits D, Enger C, Quaskey SA, Baumgartner WA, Cameron DE, Stuart RS, Gardner TJ. Cognitive outcome after coronary artery bypass: A one-year prospective study. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63(2):510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selnes OA, Grega MA, Bailey MM, Pham L, Zeger S, Baumgartner WA, McKhann GM. Neurocognitive outcomes 3 years after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A controlled study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84(6):1885–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadelson MR, Sanders RD, Avidan MS. Perioperative cognitive trajectory in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112(3):440–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Robins JM. When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? an example with education and cognitive change. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inouye SK, Marcantonio ER, Kosar CM, Tommet D, Schmitt EM, Travison TG, Saczynski JS, Ngo LH, Alsop DC, Jones RN. The short-term and long-term relationship between delirium and cognitive trajectory in older surgical patients. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(7):766–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evered LA, Silbert B, Knopman D, Scott DA, DeKosky S, Oh E, Rasmussen L, Crosby G, Berger M, Eckenhoff R, and the nomenclature consensus working party. Recommendations for the nomenclature of cognitive change associated with anaesthesia and surgery. 2018. Br J Anaesth. Accepted Oct 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evered L, Scott DA, Silbert B, Maruff P. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction is independent of type of surgery and anesthetic. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(5):1179–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neufeld KJ, Leoutsakos JS, Sieber FE, Joshi D, Wanamaker BL, Rios-Robles J, Needham DM. Evaluation of two delirium screening tools for detecting post-operative delirium in the elderly. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(4):612–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sprung J, Roberts RO, Weingarten TN, Cavalcante AN, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Hanson AC, Schroeder DR, Warner DO. Postoperative delirium in elderly patients is associated with subsequent cognitive impairment. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119(2):316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franck M, Nerlich K, Neuner B, Schlattmann P, Brockhaus WR, Spies CD, Radtke FM. No convincing association between post-operative delirium and post-operative cognitive dysfunction: A secondary analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2016;60(10):1404–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Munster BC, Aronica E, Zwinderman AH, Eikelenboom P, Cunningham C, Rooij SE. Neuroinflammation in delirium: A postmortem case-control study. Rejuvenation Res. 2011;14(6):615–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Noble JM, Manly JJ, Schupf N, Tang MX, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA. Association of C-reactive protein with cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(1):87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siepe M, Pfeiffer T, Gieringer A, Zemann S, Benk C, Schlensak C, Beyersdorf F. Increased systemic perfusion pressure during cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with less early postoperative cognitive dysfunction and delirium. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40(1):200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolters FJ, Zonneveld HI, Hofman A, van der Lugt A, Koudstaal PJ, Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Heart Brain Connection Collaborative Research Group. Cerebral perfusion and the risk of dementia: A population-based study. Circulation. 2017;136(8):719–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughes CG, Patel MB, Pandharipande PP. Pathophysiology of acute brain dysfunction: What’s the cause of all this confusion? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18(5):518–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao E, Tranovich MJ, Wright VJ. The role of mobility as a protective factor of cognitive functioning in aging adults: A review. Sports Health. 2014;6(1):63–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spira AP, Chen-Edinboro LP, Wu MN, Yaffe K. Impact of sleep on the risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(6):478–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bezdicek O, Stepankova H, Martinec Novakova L, Kopecek M. Toward the processing speed theory of activities of daily living in healthy aging: Normative data of the functional activities questionnaire. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28(2):239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goverover Y, Genova HM, Hillary FG, DeLuca J. The relationship between neuropsychological measures and the timed instrumental activities of daily living task in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13(5):636–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morandi A, Rogers BP, Gunther ML, Merkle K, Pandharipande P, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Thompson J, Shintani AK, Geevarghese S, Miller RR 3rd, Canonico A, Cannistraci CJ, Gore JC, Ely EW, Hopkins RO; VISIONS Investigation, VISualizing Icu SurvivOrs Neuroradiological Sequelae. The relationship between delirium duration, white matter integrity, and cognitive impairment in intensive care unit survivors as determined by diffusion tensor imaging: The VISIONS prospective cohort magnetic resonance imaging study*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(7):2182–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turken A, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Bammer R, Baldo JV, Dronkers NF, Gabrieli JD. Cognitive processing speed and the structure of white matter pathways: Convergent evidence from normal variation and lesion studies. Neuroimage. 2008;42(2):1032–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dawson JD, Uc EY, Anderson SW, Johnson AM, Rizzo M. Neuropsychological predictors of driving errors in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(6):1090–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Herr DL, Maze M, Girard TD, Miller RR, Shintani AK, Thompson JL, Jackson JC, Deppen SA, Stiles RA, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW. Effect of sedation with dexmedetomidine vs lorazepam on acute brain dysfunction in mechanically ventilated patients: The MENDS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2644–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]