Abstract

Flavonoids are major plant constituents with numerous biological/pharmacological actions both in vitro and in vivo. Of these actions, their anti-inflammatory action is prominent. They can regulate transcription of many proinflammatory genes such as cyclooxygenase-2/inducible nitric oxide synthase and many cytokines/chemokines. Recent studies have demonstrated that certain flavonoid derivatives can affect pathways of inflammasome activation and autophagy. Certain flavonoids can also accelerate the resolution phase of inflammation, leading to avoiding chronic inflammatory stimuli. All these pharmacological actions with newly emerging activities render flavonoids to be potential therapeutics for chronic inflammatory disorders including arthritic inflammation, meta-inflammation, and inflammaging. Recent findings of flavonoids are summarized and future perspectives are presented in this review.

Keywords: Flavonoid, Chronic inflammation, Therapeutics, Inflammaging, Meta-inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Inflammation is the body defense mechanism against foreign insulting agents such as microbes. Some cellular components and metabolites can sometimes act as inflammatory insults to the body itself. Recent findings have suggested that high glucose level, obesity, aging, and body materials can produce autoantibodies to provoke inflammatory responses for a long period. Such chronic inflammation may lead to several disease states including gout, arthritis, vascular diseases, and late-stage cancers. Thus, long-term safe use of certain anti-inflammatory agents is necessary and agents that can inhibit these inflammatory conditions may have beneficial effect on the body. In this regard, plant-originated compounds might be potential candidates for this use.

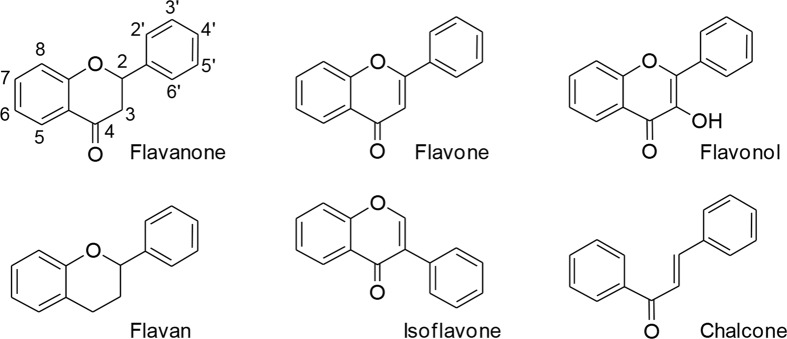

Flavonoids (Fig. 1) are one of large entities of plant constituents. Some flavonoids possess significant anti-inflammatory activity both in vitro and in vivo. There have been many reviews of the anti-inflammatory flavonoids and their action mechanisms. Previously, we have claimed that certain flavonoids can exert their anti-inflammatory action largely by modulating the expression of proinflammatory molecules such as proinflammatory enzymes including cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6 (Kim et al., 2004). In this respect, wogonin and its related molecules have shown the most potent activity among the flavonoids examined (Kim et al., 1999; Chi et al., 2001, 2003). The new flavonoid derivatives with anti-inflammatory action have been continuously found and the findings are culminated (Lim et al., 2009, 2011b). Among synthetic flavones, 8-pyridinyl flavonoid derivative can down-regulate the expression of COX-2 and iNOS (Lim et al., 2011a).

Fig. 1.

Some basic chemical structures of flavonoids.

Although certain flavonoids possess inhibitory effects on acute inflammatory responses both in vitro and in vivo, they are not expected to be desirable therapeutics against acute inflammation because currently used anti-inflammatory agents including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and indomethacin) or steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (SAIDs such as prednisolone and dexamethasone) show pharmacological effectiveness in these clinical conditions. Besides, flavonoids show much lower anti-inflammatory potency than NSAIDs and SAIDs. However, flavonoids are potential therapeutics for chronic inflammatory conditions mainly because they can act on several chronic inflammatory conditions without showing serious side effects for a prolonged time whereas long-term use of NSAIDs or SAIDs is not tolerated mainly due to their serious complications. Thus, due to limitations of currently used anti-inflammatory agents, flavonoids have clear advantages as new anti-inflammatory agents targeting chronic conditions.

Here, we summarize findings of anti-inflammatory flavonoids for chronic inflammatory disease conditions including arthritis, metabolic inflammation, and age-related inflammation. Some significant and important recent findings related to anti-inflammatory flavonoid researches since 2011 are also summarized and future perspectives are discussed.

EFFECTS OF FLAVONOIDS ON ANIMAL MODELS OF ARTHRITIS (JOINT INFLAMMATION)

Human joint inflammation is caused by various endogenous and exogenous insults. Examples include repeated pressure to the cartilage, cold weather, and joint infection by microbes. Several inflammatory disorders can also provoke joint inflammation. Among them, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA) are the most important. In these disease processes, continuous inflammatory stimulation provides deleterious effects on cells in joint space (Goldring and Otero, 2011; Choy, 2012). Synovial fibroblasts are important cells specially involved in RA. Activated synovial fibroblasts and macrophages in acute phases can be effectively controlled by oral and/or topical application of NSAIDs and SAIDs (Quan et al., 2008). In RA, many immunological parameters can lead to symptoms (edema, fever, pain, and cartilage breakdown) in various joints of the body. Neutrophils and lymphocytes in the synovial space are also involved (Fox et al., 2010). Although many derivatives positively affect acute inflammation in various animal models, only few flavonoids have been reported to be able to inhibit inflammatory responses and symptoms in animal models of RA. For instance, quercetin, genistein, apigenin, and kaempferol reduced arthritic inflammation in RA models such as collagen-induced arthritis (Li et al., 2013, 2016c; Haleagrahara et al., 2017; Pan et al., 2018). These inhibitory actions of flavonoids against animal models of RA might be attributed to their modulatory effects on neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes. Especially, quercetin could lower neutrophil recruitment to the joint in zymosan-induced arthritis (Guazelli et al., 2018). Impacts of flavonoids on these inflammatory cells have been well summarized (Middleton, 1998). Nonetheless, it is necessary to emphasize that flavonoids can differentially affect functions of macrophage types M1 and M2 (Saqib et al., 2018; Tong et al., 2018). This finding is important in that the switch of macrophage phenotype determines either pro- or anti-inflammatory process in inflammatory diseases. So far, there are few reports about protective effects by direct regulation of flavonoids focusing on macrophage polarization in arthritis model. However, it is reasonable that flavonoids might also have potential for treating arthritic inflammation due to roles of flavonoids such as quercetin, apigenin, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) as potent modulators of macrophage phenotype (Feng et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2016a; Machova Urdzikova et al., 2017). Effects of flavonoids on macrophage phenotype switching are described further in the section of inflammatory resolution. All these results indicate that some flavonoids can inhibit several aspects of animal models of RA. However, it remains unclear whether flavonoids can really alleviate acute and/or chronic inflammatory responses clinically in RA. On the other hand, certain flavonoids might be able to affect or prevent cartilage degradation through long-term use.

Early phase of OA is characterized by pain and cartilage breakdown. These symptoms progressively become severe upon aging. In the lesion, inflammation-related cells like neutrophils and macrophages are rarely recruited. Rather, some chondrocytes are dead by apoptosis and elevated levels of cartilage degrading enzymes are expressed (Goldring and Otero, 2011). Meanwhile, osteoarthritic joints would experience edema and swollen lesion later, leading to the acceleration of joint breakdown. So far, to prevent or slow down the progression of osteoarthritis, anti-inflammatory treatment using IL-1 or TNF-α specific antibodies or receptor antagonists and strategies to interfere with cartilage breakdown have been developed (Cohen et al., 2011; Wang, 2018; Wan et al., 2018). Thus, it is notable that some flavonoids not only exert anti-inflammatory activity as mentioned above, but also possess inhibitory action on the expression of cartilage breakdown enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS).

Chondrocytes residing in cartilage are important cells. They are responsible for degrading extracellular matrix (ECM) in joint space, especially under conditions of OA (Goldring, 2000). They can synthesize ECM materials such as collagen type II and aggrecan. They can also synthesize and secrete ECM metalloproteinases such as collagenases and aggrecanases that are proteolytic enzymes. MMPs are proteinases that can hydrolyze extracellular matrix proteins including collagens and elastins. Among 24 MMPs found in human, MMP- 1, -3, and -13 are collagenases, of which MMP-13 is the most important one in degrading cartilage collagens in normal ECM turnover process and/or in diseased-state such as OA (Wang et al., 2013). On the other hand, MMP-1 is major collagenase in the skin. It also participates in the turnover process of ECM materials of the cartilage. ADAMTS-4 and -5 are also pivotal ECM degrading enzymes. They are involved in normal turnover process in ECM generation, although they are some-what induced in disease conditions (Dancevic and McCulloch, 2014). Therefore, inhibitors and/or down-regulators of these enzymes might have beneficial effects against cartilage breakdown, a final step of OA. Actually, various MMPs and ADAMTS inhibitors have been developed and some of them are under clinical trial.

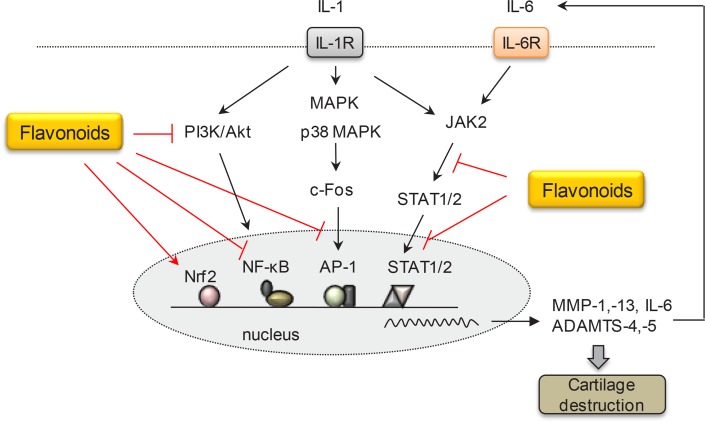

It is important to mention that certain flavonoids that can inhibit enzymatic activities of MMPs and/or suppress induction of several important MMPs involved in cartilage degradation have been found. Delphinidin (anthocyanin), flavonol derivatives (including quercetin, kaempferol, and hyperoside), and catechins with a galloyl moiety inhibit activities of gelatinases (MMP-2 and -9) and neutrophil elastase (MMP-12) (Melzig et al., 2001; Sartor et al., 2002; Im et al., 2014). Green tea polyphenols including EGCG, theaflavin, and proanthocyanidins also inhibit membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) (Oku et al., 2003; Zgheib et al., 2013; Djerir et al., 2018). On the other hand, when ultraviolet (UV)-irradiated human skin, UV-irradiated human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs), human vascular endothelial cells, and human synovial fibroblasts are treated with flavonoids, some flavonoids such as genistein, baicalein, quercetin, and nobiletin down-regulated MMP-1 expression (Kang et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2003; Sung et al., 2012; Yi et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2014). We have also found that some naturally-occurring flavonoids can inhibit MMP-1 expression in skin fibroblasts and interrupt c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)/c-Jun activation (Lim and Kim, 2007). It was also revealed that certain flavonoid derivatives inhibited MMP-13 induction in chondrocytes (Lim et al., 2011b). These reports have demonstrated that quercetin and kaempferol suppress MMP-1 expression via inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) activation in human skin fibroblasts without inhibiting MMP-13 expression in SW1353 cells, a chondrocyte cell line. Flavones such as apigenin and wogonin could decrease MMP-1 expression without affecting MAPK pathway in skin fibroblasts. Especially, the inhibitory effect of apigenin and 2′,3′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone on MMP-13 expression in chondrocytes was found to be mediated by the inhibition of c-Fos/AP-1 and janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/signal transducers and activators of transcription 1/2 (STAT1/2) pathway. As shown in these results, signaling pathways related to the expression of MMP-1 and MMP-13 are differentially regulated depending on types of flavonoid and cells or tissues. In addition, some flavonoids can inhibit ADAMTS-4 and -5 known to be key enzymes for aggrecan degradation during osteoarthritis (Majumdar et al., 2007). Recent studies have demonstrated that flavonoids such as silibinin, chrysin, baicalin, and wogonin suppressed MMP-1 and -13, but also suppressed ADAMTS-4 and/or -5 through signaling molecules such as phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt), nuclear transcription factor-κB (NF-κB), and nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) in animal OA model (Chen et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2017a, 2017b). Although clinical data are currently unavailable, it is certain that some flavonoids can act on animal models of joint inflammation. They might be especially protective against cartilage destruction probably through down-regulation of MMP expression (Fig. 2). This point should be verified further in the future.

Fig. 2.

Effects of flavonoids on the expression of MMP and ADAMTS in osteoarthritis. MMP and ADAMTS are enzymes that play crucial roles in ECM degradation in osteoarthritis progression. Flavonoids such as apigenin and 2′,3′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone inhibit MMP-13 expression via c-Fos/AP-1 and JAK2/STAT1/2 pathway in IL-1β-treated chondrocyte cell line. In animal OA model, flavonoids such as silibinin, chrysin, baicalin, and wogonin show protective effects by downregulation of ADAMTS-4 and/or -5 expression through PI3K/Akt, NF-κB and/or Nrf2 signaling pathways. IL-1R, IL-1 receptor; IL-6R, IL-6 receptor.

EFFECTS OF FLAVONOIDS ON AGING-RELATED INFLAMMATION (INFLAMMAGING)

Cellular aging process comprises various aspects of cellular metabolism. Cells become larger and eventually stop their division known as cellular senescence that prevents cancer formation in general. Thus, aging process is considered to provide some beneficial effects. However, recent studies have found that aged cells synthesize and secrete some inflammation-related molecules called senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), including inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, IL-1, and MMPs (Tchkonia et al., 2013). Serum IL-6 level in elderly humans has been found to be significantly elevated regardless of diseases (Bruunsgaard et al., 2001; Ferrucci et al., 2005). These secreted molecules affect nearby cells to provoke inflammatory responses, eventually producing aging-related chronic inflammation called inflammaging, one type of sterile persistent inflammation. Thus, long-term stimulation by SASP molecules induces various metabolic changes including cardiovascular changes (Franceschi and Campisi, 2014). Sometimes they lead to late-stage cancer (Campisi, 2013). Thus, blocking SASP production may be effective for achieving healthy aging. Many laboratories have been searching for agents to prevent the aging process itself. However, in our opinion, stopping cellular senescence may have other harmful effects on the body. Blocking cells to go into senescence cells means that they still have proliferating capacity, although they are old. This may deleteriously lead to cancer formation. In this respect, inhibition of SASP formation without affecting aging capacity (inhibition of inflammaging) seems to be a safe new target for healthy aging. To prove the beneficial effect of flavonoids on senescence and SASP production, we have evaluated several types of flavonoid derivatives, and found that apigenin and specific synthetic flavone can strongly inhibit SASP production without changing aging markers in both in vitro and in vivo models (Lim et al., 2015). Blocking SASP production by apigenin has been shown to be related to the interruption of NF-κB p65 activation and interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1)/IκBα signaling pathway in bleomycin-induced senescence of BJ fibroblasts (Lim et al., 2015). Moreover, apigenin strongly reduced gene and protein expression of IκBζ transcription factor both in vitro and in vivo. It has been previously shown that IκBζ is closely associated with SASP induction such as IL-6 and IL-8 (Alexander et al., 2013). Transcription factors such as NF-κB and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPβ) are known as signaling molecules regulating SASP production (Salminen et al., 2012; Huggins et al., 2013). Flavonoids such as baicalin and kaempferol inhibited the production of some cytokines through NF-κB signaling in aged rat (Kim et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2012). Signaling molecules such as protein kinase D1, p38 MAPK, MAPK-activated protein kinase-2 (MK2), and mixed-lineage leukemia 1 (MLL1) have been suggested to play essential roles in producing SASP molecules (Alimbetov et al., 2016; Capell et al., 2016; Su et al., 2018). Besides, several reports have demonstrated the regulation of SASP factors by some microRNAs (Panda et al., 2017).

In case of dietary flavonoids, cohort studies have suggested that flavonoid intake is inversely associated with age-related diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), neurodegeneration, and type 2 diabetes (Root et al., 2015; Grosso et al., 2017; Kim and Je, 2017; Lefèvre-Arbogast et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018). In studies investigating the underlying mechanism for this phenomena, administration of fisetin and rutin in animal models has shown protective activity by preventing increased production of IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in age-related disorders such as neurodegeneration and metabolic dysfunction (Li et al., 2016b; Singh et al., 2018). Uptake of luteolin, baicalin, genistein, and kaempferol also lowered the elevated level of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6 or NF-κB activation in aged animal model (Kim et al., 2010, 2011; Lim et al., 2012; Burton et al., 2016).

Inflammasome activation is also associated with the aging process. Many damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as uric acid and cholesterol crystal are increased with age, leading to chronic low-grade inflammation following inflammasome activation (Huang et al., 2015). Aging tissue has high degree of NF-κB activation. Aging can stimulate inflammasome activation to produce inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 (Song et al., 2016). With SASP, these cytokines may have more impacts on cells to accelerate the aging process. Expression of inflammasome gene modules including IL-1β is positively associated with human aging, especially in those aged over 85 years (Furman et al., 2017). For neutralization of IL-1β, treatment with IL-1β antibody for patients with myocardial infarction and low-grade inflammation reduces cardiovascular mortality (Ridker et al., 2018). Recent studies have demonstrated the role of inflammasome in metabolic disease such as human diabetes that is more likely to develop with age (Bauernfeind et al., 2016; Cordero et al., 2018). With respect to bacterial infection during aging, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment in aged rat can lead to long-lasting neuroinflammation through NF-κB activation and excessive IL-1β release in the hippocampus (Fu et al., 2014). In the liver of aged rats, the expression of Nod-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3)-related components such as NLRP3, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a C-terminal caspase recruitment domain (ASC), caspase-1, and IL-1β are apparently increased than those in young rats during LPS-induced endotoxemia (Chung et al., 2015). Increased level of IL-1β in adipose tissue could induce age-dependent overproduction of IL-6 through autocrine/paracrine action (Starr et al., 2015). In addition, due to elevation of NLRP3 inflammasome at basal level with age, it has been demonstrated that specific bacterial clearance does not properly work (Krone et al., 2013).

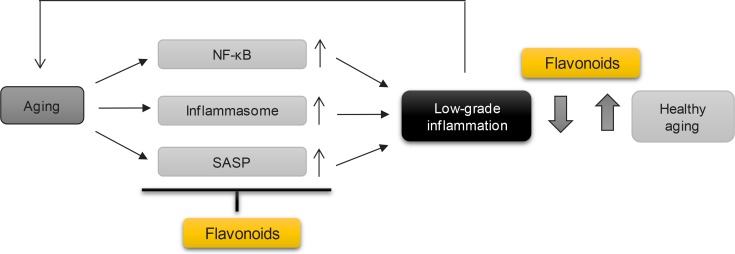

To develop a therapeutic tool to target inflammaging, it is necessary to find an inflammasome inhibitor that has the potential to suppress the expression of inflammasome components or directly block inflammasome activation itself. Since flavonoids have effects on SASP production and inflammasome activation associated with aging (Fig. 3), dietary uptake of flavonoids or flavonoid-rich food and vegetables could help reduce the level of age-related inflammation, ultimately leading to healthy aging.

Fig. 3.

Effects of flavonoids on inflammaging. Cellular aging causes low-grade chronic inflammation, called inflammaging. Some flavonoids have potential as therapeutic candidates for healthy aging by modulating the markers of aging-associated inflammation such as NF-κB activation, inflammasome activation and SASP production.

EFFECTS OF FLAVONOIDS ON OBESITY-ASSOCIATED INFLAMMATION (METABOLIC INFLAMMATION, META-INFLAMMATION)

Obesity causes chronic and persistent inflammation in adipose tissue which is closely linked to the development of metabolic disease such as insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and cancer (Divella et al., 2016; Saltiel and Olefsky, 2017). Adipocytes are known to secrete chemokines such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) that can induce macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue. Adipose tissue macrophages play a crucial role in obesity-associated inflammation and insulin resistance (Amano et al., 2014; Engin, 2017). Infiltrated macrophage is activated to M1 phenotype that secretes pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 to induce chronic inflammation. These cytokines can lead to the development of insulin resistance and apoptosis of pancreatic beta-cells (Appari et al., 2018). It is now clear that obesity produces inflammatory environment to the body that can lead to chronic inflammation and meta-inflammation, thus having deleterious effects on the body.

So far, many reports have demonstrated the anti-obesity activity of flavonoids by modulating the production of inflammatory molecules via affecting several cellular signaling pathways. In particular, there have been several reports concerning quercetin in obesity-associated inflammation. Quercetin inhibited the inflammatory response of macrophages via activation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) a1 phosphorylation and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) expression (Dong et al., 2014). Quercetin also reduced obesity-induced hypothalamic inflammation accompanied by heme oxygenase (HO)-1 induction in microglia (Yang et al., 2017). The effect of quercetin on HO-1 induction is correlated with macrophage phenotype switching effect in hepatic inflammation caused by obesity (Kim et al., 2016a). These effects of quercetin have been proven in vivo by the finding that supplementation with quercetin into mice for 18 weeks reduced the number of macrophages in adipose tissue (Kobori et al., 2016). Butein chalcone also induced HO-1 expression via p38 MAPK/Nrf2 pathway in adipocytes (Wang et al., 2017b).

Besides, EGCG reduced macrophage infiltration and insulin resistance in high-fat diet (HFD) animal model and suppressed toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) expression which is strongly associated with obesity-induced inflammation due to the first trigger-action (Bao et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2014; Kumazoe et al., 2017). Naringenin also inhibits macrophage infiltration involved in JNK pathway (Yoshida et al., 2014). A recent study has shown that apigenin attenuated metabolic inflammation via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPARγ) activation and lowered malondialdehyde, IL-1β, and IL-6 colonic levels in HFD mouse model (Feng et al., 2016; Gentile et al., 2018). Specific chalcone derivatives prevented HFD-induced heart and kidney injury via MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathway (Fang et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018). In addition, there have been several reports on anti-obesity effects of flavonoids such as isoflavone daidzein (Sakamoto et al., 2016), luteolin (Xu et al., 2014), chrysin (Feng et al., 2014b), and rutin (Gao et al., 2013) by suppressing inflammation.

Cohort studies on flavonoid intake and obesity have been continuously carried out (Bertoia et al., 2016; Marranzano et al., 2018). Considering with the anti-inflammatory effect of flavonoids, a recent cohort study has also shown that flavonoid intake is inversely associated with body mass index and level of C-reactive protein which is produced in response to inflammation (Vernarelli and Lambert, 2017). All these studies suggest that flavonoids can reduce obesity and obesity-related chronic inflammation.

EFFECTS OF FLAVONOIDS ON INFLAMMATORY RESOLUTION

To finish an inflammatory process in the body, inflammatory resolution should properly work. Inflammatory resolution is tightly regulated by cellular pathways involving many signaling molecules and factors in the pathological progress of inflammatory diseases. During resolution, not only pro-inflammatory mediators are negatively regulated, but also immune cell influx are stopped by the action of lipid mediators such as lipoxin A4 and resolvin E1 followed by clearance of recruited neutrophils from inflamed sites in the way of apoptosis or necrosis (Schett and Neurath, 2018). However, dysregulation of acute inflammatory resolution can lead to chronic inflammation in which the balance between innate and adaptive immunity is inadequately controlled (Fullerton and Gilroy, 2016). In particular, during inflammatory resolution, it has been demonstrated that the population of macrophage phenotype can specifically determine either deleterious or protective role depending on the type and state of inflammatory diseases (Anders and Ryu, 2011; Liu et al., 2014; Parisi et al., 2018).

Flavonoids are known to regulate macrophage polarization at post-resolution and down-regulate pro-inflammatory signals at initiation of resolution. Importantly, it has been found that chrysin induced anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype and decreased M1 phenotype in macrophages (Feng et al., 2014b). It has also been demonstrated that pentamethoxyflavanone inhibited M1 phenotype but increased M2 phenotype macrophages (Feng et al., 2014a). In line with these observations, quercetin can inhibit hepatic M1 macrophage and gene expression of M1-related inflammatory cytokines in carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis and obesity-induced hepatic inflammation (Dong et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2016a; Li et al., 2018). Apigenin reversed M1 macrophage into M2 via activation of PPARγ in HFD and ob/ob mice (Feng et al., 2016). Rutin also induced microglial polarization to M2 phenotype, suggesting its potential to possibly treat neurodegenerative disease (Bispo da Silva et al., 2017). Baicalin and naringenin reduced inflammatory symptom caused by M1 to M2 macrophage polarization in inflammatory bowel disease and atopic dermatitis, respectively (Karuppagounder et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2016).

Therefore, flavonoids can affect all phases of inflammatory responses. Since regulation of inflammatory resolution is important in chronic inflammatory disorders, it is suggested that flavonoids are promising agents that can alleviate symptoms of chronic inflammation.

NEW ANTI-INFLAMMATORY CELLULAR MECHANISMS OF FLAVONOIDS

Effects on TLR and inflammasome pathways

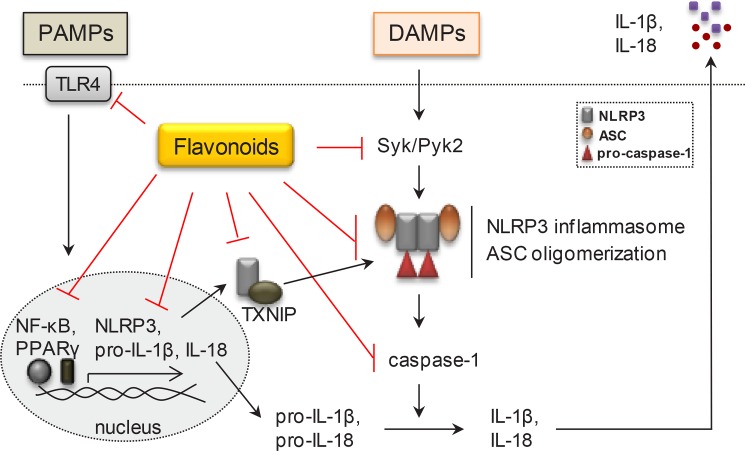

For inflammasome activation as first-line defense of innate immunity, a priming step via TLR is a prerequisite for subsequent activation step, leading to the production of pro-forms of IL-1β and IL-18 and NLRP3 protein through NF-κB activation (He et al., 2016b). Inhibitory effects of flavonoids such as anthocyanin, luteolin, hyperin, and alpinetin on inflammasome through TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway have been demonstrated in several reports (Chunzhi et al., 2016; He et al., 2016a; Zhang et al., 2017b; Cui et al., 2018). Until now, many flavonoids have been found to be able to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Studies on flavonoids having inhibitory effects on the inflammasome have been mainly focused on inhibition of the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome-related components such as IL-1β, IL-18, NLRP3, and caspase-1.

Quercetin inhibited kidney injury in rats via regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome (Wang et al., 2012). In case of protective effect of flavonoids on gout arthritis, effects of quercetin, hesperidin methylchalcone, EGCG, and morin in relation to NLRP3 inflammasome have been demonstrated in several animal models (Dhanasekar and Rasool, 2016; Jhang et al., 2016; Ruiz-Miyazawa et al., 2017, 2018). Luteolin as a caspase-1 enzyme inhibitor has shown cardioprotective effect by reducing the expression of NLRP3 and ASC protein both in in vitro and in vivo myocardial ischemia/reperfusion model (White et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2017b). Luteoloside down-regulated protein expression levels of NLRP3, matured IL-1β, and caspase-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (Fan et al., 2014). Rutin and morin also possess inhibitory effects on NLRP3 inflammasome in several animal models (Aruna et al., 2014; Dhanasekar and Rasool, 2016; Wang et al., 2017a).

It is evident that several types of flavonoids can inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome by decreasing the expression of inflammasome components and/or blocking inflammasome assembly such as ASC oligomerization. For instance, EGCG abundant in tea can inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome conjugation with thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) in THP-1 cells and ameliorate peritoneal inflammation by inhibiting NLRP3 expression and IL-1β release in monosodium urate (MSU) crystal-treated mice (Jhang et al., 2016). Quercetin can inhibit the expression of NLRP3 and IL-1β and caspase-1 activity in human colonic epithelial cells. It also has inhibitory effects on NLRP3 and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) inflammasome by preventing ASC oligomerization in both in vitro and in vivo mouse vasculitis model (Domiciano et al., 2017; Xue et al., 2017). Apigenin can reduce IL-1β and IL-18 release and NLRP3 expression in chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS)-induced rat brain (Li et al., 2016a). Isoliquiritigenin, a chalcone derivative, has shown similar dual activity in adipose tissue inflammation (Honda et al., 2014).

As noted above, some flavonoid derivatives can inhibit IL-1β production. However, most of them only reduce IL-1β production via inhibition of pro-IL-1β expression. Only a few flavonoids such as quercetin could reduce NLRP3 activation and ASC oligomerization. To clearly establish their pharmacological action on NLRP3 activation, many flavonoids have been further examined. In our previous study, several flavonoid derivatives have been found to be able to inhibit IL-1β production in MSU-treated THP-1 cells (Lim et al., 2018). Especially, apigenin, kaempferol, and 3′,4′-dichloroflavone reduced IL-1β production by inhibition of ASC oligomerization regardless of intracellular ASC level. The inhibitory effect of apigenin on activation of NLRP3 inflammasome has been proven to be attributed to spleen tyrosine kinase/protein tyrosine kinase 2 (Syk/Pyk2) pathway (Fig. 4). Furthermore, apigenin administration can inhibit the number of infiltrated inflammatory cells in MSU-induced peritonitis in mice (Lim et al., 2018). All these findings clearly indicate that some flavonoids can interrupt inflammasome production that could contribute to the anti-inflammatory activity of certain flavonoids both in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Effects of flavonoids on signaling pathway of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Many flavonoids possess anti-inflammatory activities by interrupting various signaling stages of NLRP3 inflammasome pathway both in vitro and in vivo. They inhibit the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome-related components such as IL-1β, IL-18, NLRP3, and caspase-1 and/or block inflammasome assembly which are mediated through signaling molecules such as TLR4/NF-κB/NLRP3, PPARγ, TXNIP and Syk/Pyk2, etc.

Recently, besides canonical inflammasome pathways, the importance of noncanonical pathways has been emerged in inflammasome activation accompanied by components such as caspase-8, -11, and P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) (Kayagaki et al., 2011; Gurung et al., 2014; Ousingsawat et al., 2018). It has been shown that apigenin supplementation can inhibit both caspase-1 and caspase-11 in chronic ulcerative colitis model (Márquez-Flores et al., 2016). However, in another report, the protective effect of apigenin against acute colitis has been suggested to be mediated by NLRP6 signaling pathway independent of caspase 1, 11, or ASC (Radulovic et al., 2018). Dihydroquercetin has hepatoprotective activity through P2X7R/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway (Zhang et al., 2018). Thus, whether flavonoids targeting inflammasome components in canonical pathway can also affect these components involved in noncanonical inflammasome pathways should be further studied.

Effects on autophagy

Autophagy maintains internal homeostasis by clearing damaged organelles, proteins, and intracellular pathogens through lysosomal degradative pathway (Glick et al., 2010). Impairment of autophagy can lead to many diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, infectious disease, and neurodegenerative disease (Jiang and Mizushima, 2014). Due to the protective role of autophagy in the pathophysiology, autophagy modulation has been focused as an important target to regulate these diseases (Rubinsztein et al., 2012).

Signaling molecules (such as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), AMPK, unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1/2 (ULK1/2), and LC3) and multiple transcription factors are involved in autophagy activation (Levy et al., 2017). Many reports have proven that flavonoids with antioxidant activity as one of their detoxification ability can stimulate autophagy through mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum and proteasome both in vitro and in vivo (Hasima and Ozpolat, 2014). In various cancer cell lines, flavonoids such as quercetin, apigenin, silibinin, and EGCG can increase the expression of Beclin-1, LC3-II, and several types of autophagy-related (ATG) (Jiang et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2018). However, depending on the type or stage of cancer cell, autophagy can either promote or suppress cancer cells (Gewirtz, 2014). Thus, cancer therapy targeting autophagy pathway using flavonoids requires accurate regulation under a precise understanding of autophagy.

It is important to note that some flavonoids can reduce abnormal protein aggregates such as β-amyloid peptides and hyperphosphorylated tau protein through autophagy pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Quercetin prevented β-amyloid aggregation by activating macroautophagy in Caenorhabditis elegans (Regitz et al., 2014). It has been shown that fisetin degraded phosphorylated tau through autophagy activation mediated by transcription factors such as transcription factor EB (TFEB) and Nrf2 (Kim et al., 2016b). EGCG also decreased phosphotau protein by increasing mRNA expression of autophagy adapter proteins in rat primary neuron culture (Chesser et al., 2016). For Parkinson’s disease (PD), treatment with baicalin and quercetin augments autophagic functions and leads to prevention against rotenone-induced neurotoxicity in an in vivo PD model (El-Horany et al., 2016; Kuang et al., 2017).

Flavonoids also have potential for cardioprotective therapy by activating cardiac autophagy. For instance, nobiletin has shown myocardial protective effect by restoring autophagy flux after acute myocardial infarction model in rats (Wu et al., 2017). Apigenin can relieve LPS-induced myocardial injury through modulation of autophagic components such as lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1), ATG5, p62, and TFEB (Li et al., 2017). Due to positive effects of vitexin, rutin, EGCG, and luteolin on autophagy regulation, therapeutic potential of flavonoids against cardiovascular disease have also been suggested (Hu et al., 2016; Xuan and Jian, 2016; Ma et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017a). In addition, flavonoids such as naringenin, baicalin, EGCG, and quercetin have protective effects against bacteria or virus infection by promoting autophagy activation (Tsai et al., 2017; Xue et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2018; Oo et al., 2018). All these newly found effects suggest that flavonoids could be promising candidates based on their ability to modulate autophagy for the treatment of degenerative diseases associated with defective autophagy.

LIMITATION OF FLAVONOIDS AS THERAPEUTIC AGENTS: BIOAVAILABILITY AND METABOLISM

As mentioned above, various flavonoid derivatives possess anti-inflammatory activity in a variety of animal models of inflammation. Nonetheless, it is apparent that flavonoids in general do not show strong effects by oral administration enough for a clinical trial. As reported by many researchers, most flavonoids possess low bioavailability by oral administration. In addition, they experience rapid metabolism in the body. After flavonoid ingestion as a form of daily food products or herbal remedy, maximum concentrations of flavonoids in the blood are expected to be generally very low (in micromolar ranges). Moreover, rapid metabolic conversion produces more hydrophilic flavonoid derivatives (flavonoid sulfates, glucuronates and/or glycosylates) that might be less active compared to their original molecules. In one study, actual plasma concentrations of orally administered flavonoids were found to be less than 1 μM except for several cases (Chen et al., 2005). Besides, low oral bioavailability of flavonoid ingestion has been demonstrated again and again. The maximum plasma concentration of quercetin therapeutically treated by oral administration to rats was less than 10 μM even if concentrations of various metabolites including methylated, sulfated, and glycosylated metabolites were combined (Tran et al., 2014). In one human study, plasma isoflavonoid (genistein) concentration in Japanese men having a high intake of genistein and genistin as soy products was approximately 0.3 μM (Adlercreutz et al., 1993). Several reviews have summarized findings of absorption and bioavailability of flavonoids (Ross and Kasum, 2002; Lotito and Frei, 2006). Generally, all these previous observations suggest that the low bioavailability and rapid metabolism of oral flavonoids limit their therapeutic use for acute inflammatory conditions since biologically meaningful effects of flavonoids on inflammatory response possibly will appear at concentration higher than 10 μM. Nonetheless, flavonoids may be promising therapeutics for chronic inflammatory conditions with less adverse effects as noted above since long-term administration is needed and few appropriate therapeutic agents are available in clinics to date.

An interesting notion is that some flavonoid glucuronides among glycosylated metabolites may show significant activity in the body by conjugation and deconjugation pathway (Perez-Vizcaino et al., 2012). In general, glucuronide conjugates of flavonoids are known to be less active in vivo than those of aglycone. However, it has been proposed that glucuronidated quercetin can act as precursor of aglycone in vivo which could be converted to active quercetin in situ by β-glucuronidase (Terao et al., 2011; Galindo et al., 2012). Genistein 7-O-glucuronide can be converted to genistein by β-glucuronidase in inflamed mouse skin of pseudoinfection model. Such glucuronide derivative can increase phagocytic activities of macrophage (Kaneko et al., 2017). Glucuronidated kaempferol derivatives can inhibit several protein kinases and retain target selectivity in HepG2 cell line, although their potency is lower than aglycone (Beekmann et al., 2016). These reports indicate that in therapeutic trial against inflammatory conditions, certain glucuronidated metabolites may play biologically meaningful roles by metabolic conversion in vivo.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

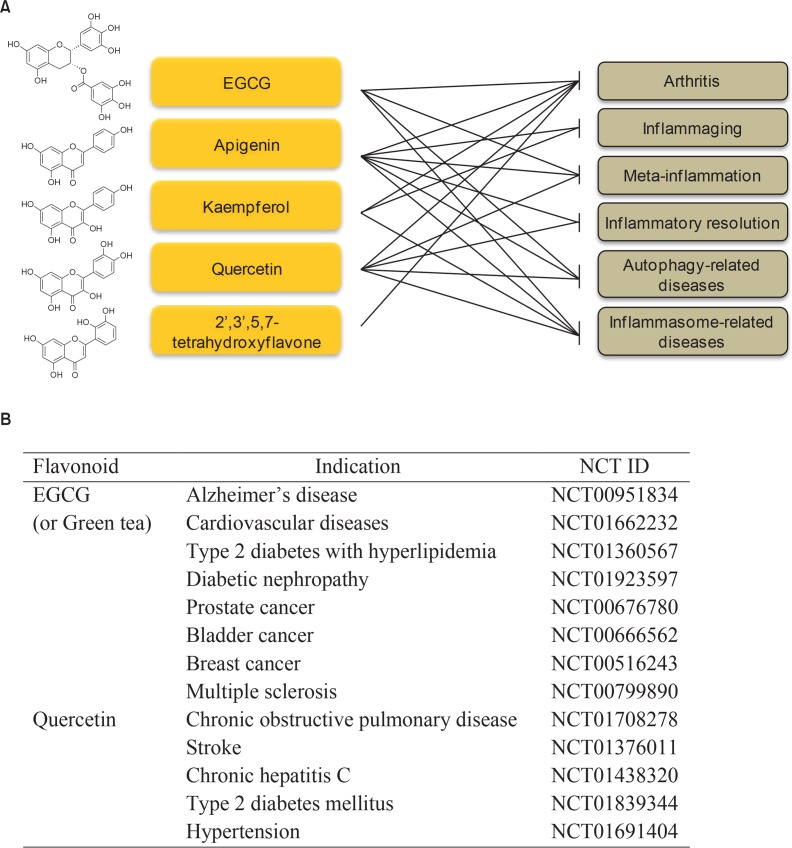

Flavonoids affect all phases of inflammatory processes. Although there are some limitations of flavonoids by using the oral route of administration, treatment against chronic inflammation for long-term use is possible. Moreover, high concentrations of flavonoids may be obtained more easily by local treatment. Especially, topical application through skin is one of plausible routes of flavonoid administration in human. Flavonoids may be efficiently used for skin inflammatory disorders topically if proper formulation such as nanoparticle or lipid nanocapsule is used (Chuang et al., 2017; Chamcheu et al., 2018; Hatahet et al., 2018). As noted above, applicable disorders by using flavonoid therapy are expanding. In particular, flavonoids may be used for healthy aging. Various aspects of molecular mechanisms are to be explored further. Clinical trial of certain flavonoids (Fig. 5) for these chronic inflammatory disorders is urgently needed.

Fig. 5.

The suggested flavonoids with core structures showing reasonable inhibitory action on chronic inflammatory responses and clinical trials of some flavonoids. Among a variety of flavonoids, flavonoids such as EGCG, apigenin, kaempferol, quercetin, and 2′,3′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone have shown anti-inflammatory activities in many previous reports. In particular, their inhibitory actions are effective for blocking chronic inflammatory mechanisms such as arthritis, inflammaging, meta-inflammation, inflammatory resolution, autophagy and inflammasome-related diseases (A). So far, clinical trials of some flavonoids such as EGCG and quercetin have been processed for several diseases but there is a necessity of more clinical trials for chronic disorders accompanying with these inflammatory responses. Some recent completed clinical trials of flavonoids, EGCG and quercetin, are demonstrated (B). N/A, Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Basic Research Program through the National Research Foundation (NRF2016R1A2B4007756) and BK21-plus from the Ministry of Education. The bioassay facility of New Drug Development Institute (KNU) was used.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Adlercreutz H, Markkanen H, Watanabe S. Plasma concentrations of phyto-oestrogens in Japanese men. Lancet. 1993;342:1209–1210. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92188-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander E, Hildebrand DG, Kriebs A, Obermayer K, Manz M, Rothfuss O, Schulze-Osthoff K, Essmann F. IκBζ is a regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype in DNA damage- and oncogene-induced senescence. J. Cell Sci. 2013;126:3738–3745. doi: 10.1242/jcs.128835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alimbetov D, Davis T, Brook AJ, Cox LS, Faragher RG, Nurgozhin T, Zhumadilov Z, Kipling D. Suppression of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in human fibroblasts using small molecule inhibitors of p38 MAP kinase and MK2. Biogerontology. 2016;17:305–315. doi: 10.1007/s10522-015-9610-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano SU, Cohen JL, Vangala P, Tencerova M, Nicoloro SM, Yawe JC, Shen Y, Czech MP, Aouadi M. Local proliferation of macrophages contributes to obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Cell Metab. 2014;19:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders HJ, Ryu M. Renal microenvironments and macrophage phenotypes determine progression or resolution of renal inflammation and fibrosis. Kidney Int. 2011;80:915–925. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appari M, Channon KM, McNeill E. Metabolic regulation of adipose tissue macrophage function in obesity and diabetes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018;29:297–312. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruna R, Geetha A, Suguna P. Rutin modulates ASC expression in NLRP3 inflammasome: a study in alcohol and cerulein-induced rat model of pancreatitis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2014;396:269–280. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Cao Y, Fan C, Fan Y, Bai S, Teng W, Shan Z. Epigallocatechin gallate improves insulin signaling by decreasing toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activity in adipose tissues of high-fat diet rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014;58:677–686. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind F, Niepmann S, Knolle PA, Hornung V. Aging-associated TNF production primes inflammasome activation and NLRP3-related metabolic disturbances. J. Immunol. 2016;197:2900–2908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekmann K, de Haan LH, Actis-Goretta L, van Bladeren PJ, Rietjens IM. Effect of glucuronidation on the potential of kaempferol to inhibit serine/threonine protein kinases. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016;64:1256–1263. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoia ML, Rimm EB, Mukamal KJ, Hu FB, Willett WC, Cassidy A. Dietary flavonoid intake and weight maintenance: three prospective cohorts of 124,086 US men and women followed for up to 24 years. BMJ. 2016;352:i17. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bispo da Silva A, Cerqueira Coelho PL, Alves Oliveira Amparo J, Alves de Almeida Carneiro MM, Pereira Borges JM, Dos Santos Souza C, Dias Costa MF, Mecha M, Guaza Rodriguez C, Amaral da Silva VD, Lima Costa S. The flavonoid rutin modulates microglial/macrophage activation to a CD150/CD206 M2 phenotype. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017;274:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruunsgaard H, Pedersen M, Pedersen BK. Aging and proinflammatory cytokines. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2001;8:131–136. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton MD, Rytych JL, Amin R, Johnson RW. dietary luteolin reduces proinflammatory microglia in the brain of senescent mice. Rejuvenation Res. 2016;19:286–292. doi: 10.1089/rej.2015.1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013;75:685–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Bao S, Yang W, Zhang J, Li L, Shan Z, Teng W. Epigallocatechin gallate prevents inflammation by reducing macrophage infiltration and inhibiting tumor necrosis factor-α signaling in the pancreas of rats on a high-fat diet. Nutr. Res. 2014;34:1066–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capell BC, Drake AM, Zhu J, Shah PP, Dou Z, Dorsey J, Simola DF, Donahue G, Sammons M, Rai TS, Natale C, Ridky TW, Adams PD, Berger SL. MLL1 is essential for the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Genes Dev. 2016;30:321–336. doi: 10.1101/gad.271882.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamcheu JC, Siddiqui IA, Adhami VM, Esnault S, Bharali DJ, Babatunde AS, Adame S, Massey RJ, Wood GS, Longley BJ, Mousa SA, Mukhtar H. Chitosan-based nanoformulated (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) modulates human keratinocyte-induced responses and alleviates imiquimod-induced murine psoriasiform dermatitis. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2018;13:4189–4206. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S165966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Zhang C, Cai L, Xie H, Hu W, Wang T, Lu D, Chen H. Baicalin suppresses IL-1β-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines via blocking NF-κB in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes and shows protective effect in mice osteoarthritis models. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017;52:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yin OQ, Zuo Z, Chow MS. Pharmacokinetics and modeling of quercetin and metabolites. Pharm. Res. 2005;22:892–901. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-4584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yu W, Li W, Zhang H, Huang W, Wang J, Zhu W, Fang Q, Chen C, Li X, Liang G. An anti-inflammatory chalcone derivative prevents heart and kidney from hyperlipidemia-induced injuries by attenuating inflammation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018;338:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesser AS, Ganeshan V, Yang J, Johnson GV. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate enhances clearance of phosphorylated tau in primary neurons. Nutr. Neurosci. 2016;19:21–31. doi: 10.1179/1476830515Y.0000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi YS, Cheon BS, Kim HP. Effect of wogonin, a plant flavone from Scutellaria radix, on the suppression of cyclooxygenase-2 and induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase in lipopolysaccharide-treated RAW 264.7 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001;61:1195–1203. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(01)00597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi YS, Lim H, Park H, Kim HP. Effect of wogonin, a plant flavone from Scutellaria radix, on skin inflammation: in vivo regulation of inflammation-associated gene expression. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;66:1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy E. Understanding the dynamics: pathways involved in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:v3–v11. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SY, Lin YK, Lin CF, Wang PW, Chen EL, Fang JY. Elucidating the skin delivery of aglycone and glycoside flavonoids: how the structures affect cutaneous absorption. Nutrients. 2017;9:E1304. doi: 10.3390/nu9121304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KW, Lee EK, Kim DH, An HJ, Kim ND, Im DS, Lee J, Yu BP, Chung HY. Age-related sensitivity to endotoxin-induced liver inflammation: implication of inflammasome/IL-1β for steatohepatitis. Aging Cell. 2015;14:524–533. doi: 10.1111/acel.12305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chunzhi G, Zunfeng L, Chengwei Q, Xiangmei B, Jingui Y. Hyperin protects against LPS-induced acute kidney injury by inhibiting TLR4 and NLRP3 signaling pathways. Oncotarget. 2016;7:82602–82608. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SB, Proudman S, Kivitz AJ, Burch FX, Donohue JP, Burstein D, Sun YN, Banfield C, Vincent MS, Ni L, Zack DJ. A randomized, double-blind study of AMG 108 (a fully human monoclonal antibody to IL-1R1) in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011;13:R125. doi: 10.1186/ar3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero MD, Williams MR, Ryffel B. AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Regulation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome during Aging. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2018;29:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui HX, Chen JH, Li JW, Cheng FR, Yuan K. Protection of anthocyanin from Myrica rubra against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury via modulation of the TLR4/NF-κB and NLRP3 pathways. Molecules. 2018;23:E1788. doi: 10.3390/molecules23071788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancevic CM, McCulloch DR. Current and emerging therapeutic strategies for preventing inflammation and aggrecanase-mediated cartilage destruction in arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2014;16:429. doi: 10.1186/s13075-014-0429-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasekar C, Rasool M. Morin, a dietary bioflavonol suppresses monosodium urate crystal-induced inflammation in an animal model of acute gouty arthritis with reference to NLRP3 inflammasome, hypo-xanthine phospho-ribosyl transferase, and inflammatory mediators. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016;786:116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divella R, De Luca R, Abbate I, Naglieri E, Daniele A. Obesity and cancer: the role of adipose tissue and adipo-cytokines-induced chronic inflammation. J. Cancer. 2016;7:2346–2359. doi: 10.7150/jca.16884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djerir D, Iddir M, Bourgault S, Lamy S, Annabi B. Biophysical evidence for differential gallated green tea catechins binding to membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase and its interactors. Biophys. Chem. 2018;234:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domiciano TP, Wakita D, Jones HD, Crother TR, Verri WA, Jr, Arditi M, Shimada K. Quercetin inhibits inflammasome activation by interfering with asc oligomerization and prevents interleukin-1 mediated mouse vasculitis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:41539. doi: 10.1038/srep41539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Zhang X, Zhang L, Bian HX, Xu N, Bao B, Liu J. Quercetin reduces obesity-associated ATM infiltration and inflammation in mice: a mechanism including AMPKα1/SIRT1. J. Lipid Res. 2014;55:363–374. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M038786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Horany HE, El-Latif RN, ElBatsh MM, Emam MN. Ameliorative effect of quercetin on neurochemical and behavioral deficits in rotenone rat model of Parkinson’s disease: modulating autophagy (quercetin on experimental Parkinson’s disease). J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2016;30:360–369. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engin A. The pathogenesis of obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017;960:221–245. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan SH, Wang YY, Lu J, Zheng YL, Wu DM, Li MQ, Hu B, Zhang ZF, Cheng W, Shan Q. Luteoloside suppresses proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e89961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Q, Wang J, Wang L, Zhang Y, Yin H, Li Y, Tong C, Liang G, Zheng C. Attenuation of inflammatory response by a novel chalcone protects kidney and heart from hyperglycemia-induced injuries in type 1 diabetic mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2015;288:179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Song P, Zhou H, Li A, Ma Y, Zhang X, Liu H, Xu G, Zhou Y, Wu X, Shen Y, Sun Y, Wu X, Xu Q. Pentamethoxyflavanone regulates macrophage polarization and ameliorates sepsis in mice. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014a;89:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Qin H, Shi Q, Zhang Y, Zhou F, Wu H, Ding S, Niu Z, Lu Y, Shen P. Chrysin attenuates inflammation by regulating M1/M2 status via activating PPARγ. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014b;89:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Weng D, Zhou F, Owen YD, Qin H, Zhao J, Wen Y, Huang Y, Chen J, Fu H, Yang N, Chen D, Li J, Tan R, Shen P. Activation of PPARγ by a natural flavonoid modulator, apigenin ameliorates obesity-related inflammation via regulation of macrophage polarization. EBioMedicine. 2016;9:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, Corsi A, Lauretani F, Bandinelli S, Bartali B, Taub DD, Guralnik JM, Longo DL. The origins of age-related proinflammatory state. Blood. 2005;105:2294–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DA, Gizinski A, Morgan R, Lundy SK. Cell-cell interactions in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2010;36:311–323. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014;69:S4–S9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu HQ, Yang T, Xiao W, Fan L, Wu Y, Terrando N, Wang TL. Prolonged neuroinflammation after lipopolysaccharide exposure in aged rats. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e106331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton JN, Gilroy DW. Resolution of inflammation: a new therapeutic frontier. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:551–556. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman D, Chang J, Lartigue L, Bolen CR, Haddad F, Gaudilliere B, Ganio EA, Fragiadakis GK, Spitzer MH, Douchet I, Daburon S, Moreau JF, Nolan GP, Blanco P, Déchanet-Merville J, Dekker CL, Jojic V, Kuo CJ, Davis MM, Faustin B. Expression of specific inflammasome gene modules stratifies older individuals into two extreme clinical and immunological states. Nat. Med. 2017;23:174–184. doi: 10.1038/nm.4267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo P, Rodriguez-Gómez I, González-Manzano S, Dueñas M, Jiménez R, Menéndez C, Vargas F, Tamargo J, Santos-Buelga C, Pérez-Vizcaíno F, Duarte J. Glucuronidated quercetin lowers blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats via deconjugation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e32673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Ma Y, Liu D. Rutin suppresses palmitic acids-triggered inflammation in macrophages and blocks high fat diet-induced obesity and fatty liver in mice. Pharm. Res. 2013;30:2940–2950. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1125-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile D, Fornai M, Colucci R, Pellegrini C, Tirotta E, Benvenuti L, Segnani C, Ippolito C, Duranti E, Virdis A, Carpi S, Nieri P, Németh ZH, Pistelli L, Bernardini N, Blandizzi C, Antonioli L. The flavonoid compound apigenin prevents colonic inflammation and motor dysfunctions associated with high fat diet-induced obesity. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0195502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz DA. The four faces of autophagy: implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2014;74:647–651. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Pathol. 2010;221:3–12. doi: 10.1002/path.2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring MB. The role of the chondrocyte in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1916–1926. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<1916::AID-ANR2>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring MB, Otero M. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2011;23:471–478. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349c2b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosso G, Micek A, Godos J, Pajak A, Sciacca S, Galvano F, Giovannucci EL. dietary flavonoid and lignan intake and mortality in prospective cohort studies: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017;185:1304–1316. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guazelli CFS, Staurengo-Ferrari L, Zarpelon AC, Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Ruiz-Miyazawa KW, Vicentini FTMC, Vignoli JA, Camilios-Neto D, Georgetti SR, Baracat MM, Casagrande R, Verri WA., Jr Quercetin attenuates zymosan-induced arthritis in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;102:175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung P, Anand PK, Malireddi RK, VandeWalle L, Van Opdenbosch N, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Green DR, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. FADD and caspase-8 mediate priming and activation of the canonical and noncanonical Nlrp3 inflammasomes. J. Immunol. 2014;192:1835–1846. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haleagrahara N, Miranda-Hernandez S, Alim MA, Hayes L, Bird G, Ketheesan N. Therapeutic effect of quercetin in collagen-induced arthritis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017;90:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasima N, Ozpolat B. Regulation of autophagy by polyphenolic compounds as a potential therapeutic strategy for cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1509. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatahet T, Morille M, Hommoss A, Devoisselle JM, Müller RH, Bégu S. Liposomes, lipid nanocapsules and smart-Crystals®: A comparative study for an effective quercetin delivery to the skin. Int. J. Pharm. 2018;542:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Wei Z, Wang J, Kou J, Liu W, Fu Y, Yang Z. Alpinetin attenuates inflammatory responses by suppressing TLR4 and NLRP3 signaling pathways in DSS-induced acute colitis. Sci. Rep. 2016a;6:28370. doi: 10.1038/srep28370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Hara H, Núñez G. Mechanism and regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016b;41:1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda H, Nagai Y, Matsunaga T, Okamoto N, Watanabe Y, Tsuneyama K, Hayashi H, Fujii I, Ikutani M, Hirai Y, Muraguchi A, Takatsu K. Isoliquiritigenin is a potent inhibitor of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and diet-induced adipose tissue inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2014;96:1087–1100. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0114-005RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, Wei F, Wang Y, Wu B, Fang Y, Xiong B. EGCG synergizes the therapeutic effect of cisplatin and oxaliplatin through autophagic pathway in human colorectal cancer cells. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015;128:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Man W, Shen M, Zhang M, Lin J, Wang T, Duan Y, Li C, Zhang R, Gao E, Wang H, Sun D. Luteolin alleviates post-infarction cardiac dysfunction by up-regulating autophagy through Mst1 inhibition. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016;20:147–156. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Xie Y, Sun X, Zeh HJ, Kang R, Lotze MT, Tang D. DAMPs, ageing, and cancer: the ‘DAMP Hypothesis’. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015;24:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins CJ, Malik R, Lee S, Salotti J, Thomas S, Martin N, Quiñones OA, Alvord WG, Olanich ME, Keller JR, Johnson PF. C/EBPγ suppresses senescence and inflammatory gene expression by heterodimerizing with C/EBPβ. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013;33:3242–3258. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01674-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im NK, Jang WJ, Jeong CH, Jeong GS. Delphinidin suppresses PMA-induced MMP-9 expression by blocking the NF-κB activation through MAPK signaling pathways in MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cells. J. Med. Food. 2014;17:855–861. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2013.3077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhang JJ, Lu CC, Yen GC. Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits urate crystals-induced peritoneal inflammation in C57BL/6 mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016;60:2297–2303. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K, Wang W, Jin X, Wang Z, Ji Z, Meng G. Silibinin, a natural flavonoid, induces autophagy via ROS-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction and loss of ATP involving BNIP3 in human MCF7 breast cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2015;33:2711–2718. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Mizushima N. Autophagy and human diseases. Cell. Res. 2014;24:69–79. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko A, Matsumoto T, Matsubara Y, Sekiguchi K, Koseki J, Yakabe R, Aoki K, Aiba S, Yamasaki K. Glucuronides of phytoestrogen flavonoid enhance macrophage function via conversion to aglycones by β-glucuronidase in macrophages. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2017;5:265–279. doi: 10.1002/iid3.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Chung JH, Lee JH, Fisher GJ, Wan YS, Duell EA, Voorhees JJ. Topical N-acetyl cysteine and genistein prevent ultraviolet-light-induced signaling that leads to photoaging in human skin in vivo. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;120:835–841. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuppagounder V, Arumugam S, Thandavarayan RA, Sreedhar R, Giridharan VV, Pitchaimani V, Afrin R, Harima M, Krishnamurthy P, Suzuki K, Nakamura M, Ueno K, Watanabe K. Naringenin ameliorates skin inflammation and accelerates phenotypic reprogramming from M1 to M2 macrophage polarization in atopic dermatitis NC/Nga mouse model. Exp. Dermatol. 2016;25:404–407. doi: 10.1111/exd.12962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N, Warming S, Lamkanfi M, Vande Walle L, Louie S, Dong J, Newton K, Qu Y, Liu J, Heldens S, Zhang J, Lee WP, Roose-Girma M, Dixit VM. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature. 2011;479:117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature10558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan NM, Haseeb A, Ansari MY, Devarapalli P, Haynie S, Haqqi TM. Wogonin, a plant derived small molecule, exerts potent anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective effects through the activation of ROS/ERK/Nrf2 signaling pathways in human osteoarthritis chondrocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;106:288–301. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CS, Choi HS, Joe Y, Chung HT, Yu R. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 with dietary quercetin reduces obesity-induced hepatic inflammation through macrophage phenotype switching. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2016a;10:623–628. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2016.10.6.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Cheon BS, Kim YH, Kim SY, Kim HP. Effects of naturally occurring flavonoids on nitric oxide production in the macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 and their structure-activity relationships. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;58:759–765. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HP, Son KH, Chang HW, Kang SS. Anti-inflammatory plant flavonoids and cellular action mechanisms. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;96:229–245. doi: 10.1254/jphs.CRJ04003X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Lee EK, Kim DH, Yu BP, Chung HY. Kaempferol modulates pro-inflammatory NF-kappaB activation by suppressing advanced glycation endproducts-induced NADPH oxidase. Age (Dordr.) 2010;32:197–208. doi: 10.1007/s11357-009-9124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Uehara Y, Choi YJ, Ha YM, Ye BH, Yu BP, Chung HY. Mechanism of attenuation of pro-inflammatory Ang II-induced NF-κB activation by genistein in the kidneys of male rats during aging. Biogerontology. 2011;12:537–550. doi: 10.1007/s10522-011-9345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Choi KJ, Cho SJ, Yun SM, Jeon JP, Koh YH, Song J, Johnson GV, Jo C. Fisetin stimulates autophagic degradation of phosphorylated tau via the activation of TFEB and Nrf2 transcription factors. Sci. Rep. 2016b;26:24933. doi: 10.1038/srep24933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Je Y. Flavonoid intake and mortality from cardiovascular disease and all causes: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 2017;20:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori M, Takahashi Y, Sakurai M, Akimoto Y, Tsushida T, Oike H, Ippoushi K. Quercetin suppresses immune cell accumulation and improves mitochondrial gene expression in adipose tissue of diet-induced obese mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016;60:300–312. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone CL, Trzciński K, Zborowski T, Sanders EA, Bogaert D. Impaired innate mucosal immunity in aged mice permits prolonged Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization. Infect. Immun. 2013;81:4615–4625. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00618-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang L, Cao X, Lu Z. Baicalein protects against rotenone-induced neurotoxicity through induction of autophagy. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2017;40:1537–1543. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b17-00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazoe M, Nakamura Y, Yamashita M, Suzuki T, Takamatsu K, Huang Y, Bae J, Yamashita S, Murata M, Yamada S, Shinoda Y, Yamaguchi W, Toyoda Y, Tachibana H. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate suppresses toll-like receptor 4 expression via up-regulation of E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase RNF216. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:4077–4088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.755959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefèvre-Arbogast S, Gaudout D, Bensalem J, Letenneur L, Dartigues JF, Hejblum BP, Fèart C, Delcourt C, Samieri C. Pattern of polyphenol intake and the long-term risk of dementia in older persons. Neurology. 2018;90:e1979–e1988. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy JMM, Towers CG, Thorburn A. Targeting autophagy in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017;17:528–542. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Lang F, Zhang H, Xu L, Wang Y, Zhai C, Hao E. Apigenin alleviates endotoxin-induced myocardial toxicity by modulating inflammation, oxidative stress, and autophagy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017;2017:2302896. doi: 10.1155/2017/2302896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Gang D, Yu X, Hu Y, Yue Y, Cheng W, Pan X, Zhang P. Genistein: the potential for efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013;32:535–540. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Wang X, Qin T, Qu R, Ma S. Apigenin ameliorates chronic mild stress-induced depressive behavior by inhibiting interleukin-1β production and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the rat brain. Behav. Brain Res. 2016a;296:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Chen S, Feng T, Dong J, Li Y, Li H. Rutin protects against aging-related metabolic dysfunction. Food Funct. 2016b;7:1147–1154. doi: 10.1039/C5FO01036E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Han Y, Zhou Q, Jie H, He Y, Han J, He J, Jiang Y, Sun E. Apigenin, a potent suppressor of dendritic cell maturation and migration, protects against collagen-induced arthritis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2016c;20:170–180. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Jin Q, Yao Q, Xu B, Li L, Zhang S, Tu C. The flavonoid quercetin ameliorates liver inflammation and fibrosis by regulating hepatic macrophages activation and polarization in mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:72. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HA, Lee EK, Kim JM, Park MH, Kim DH, Choi YJ, Ha YM, Yoon JH, Choi JS, Yu BP, Chung HY. PPARγ activation by baicalin suppresses NF-κB-mediated inflammation in aged rat kidney. Biogerontology. 2012;13:133–145. doi: 10.1007/s10522-011-9361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H, Kim HP. Inhibition of mammalian collagenase, matrix metalloproteinase-1, by naturally-occurring flavonoids. Planta Med. 2007;73:1267–1274. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-990220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H, Jin JH, Park H, Kim HP. New synthetic anti-inflammatory chrysin analog, 5,7-dihydroxy-8-(pyridine-4yl) flavone. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011a;670:617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H, Kim SB, Park H, Chang HW, Kim HP. New anti-inflammatory synthetic biflavonoid with C-C (6-6″) linkage: differential effects on cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2009;32:1525–1531. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-2104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H, Min DS, Park H, Kim HP. Flavonoids interfere with NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018;355:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H, Park H, Kim HP. Effects of flavonoids on matrix metalloproteinase-13 expression of interleukin-1β-treated articular chondrocytes and their cellular mechanisms: inhibition of c-Fos/AP-1 and JAK/STAT signaling pathways. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011b;116:221–231. doi: 10.1254/jphs.11014FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H, Park H, Kim HP. Effects of flavonoids on senescence-associated secretory phenotype formation from bleomycin-induced senescence in BJ fibroblasts. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015;96:337–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N, Sato T, Takayama Y, Mimaki Y, Sashida Y, Yano M, Ito A. Novel anti-inflammatory actions of nobiletin, a citrus polymethoxy flavonoid, on human synovial fibroblasts and mouse macrophages. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;65:2065–2071. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00203-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Tan D, Kan Q, Xiao Z, Jiang Z. The protective effect of naringenin on airway remodeling after Mycoplasma Pneumoniae infection by inhibiting autophagy-mediated lung inflammation and fibrosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2018:8753894. doi: 10.1155/2018/8753894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YC, Zou XB, Chai YF, Yao YM. Macrophage polarization in inflammatory diseases. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2014;10:520–529. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.8879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotito SB, Frei B. Consumption of flavonoid-rich foods and increased plasma antioxidant capacity in humans: Cause, consequence, or epiphenomenon? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;41:1727–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Yang L, Ma J, Lu L, Wang X, Ren J, Yang J. Rutin attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via regulating autophagy and apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017;1863:1904–1911. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machova Urdzikova L, Ruzicka J, Karova K, Kloudova A, Svobodova B, Amin A, Dubisova J, Schmidt M, Kubinova S, Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Jendelova P. A green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate enhances neuroregeneration after spinal cord injury by altering levels of inflammatory cytokines. Neuropharmacology. 2017;126:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar MK, Askew R, Schelling S, Stedman N, Blanchet T, Hopkins B, Morris EA, Glasson SS. Double-knockout of ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 in mice results in physiologically normal animals and prevents the progression of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3670–3674. doi: 10.1002/art.23027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Márquez-Flores YK, Villegas I, Cárdeno A, Rosillo MÁ, Alarcón-de-la-Lastra C. Apigenin supplementation protects the development of dextran sulfate sodium-induced murine experimental colitis by inhibiting canonical and non-canonical inflammasome signaling pathways. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016;30:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marranzano M, Ray S, Godos J, Galvano F. Association between dietary flavonoids intake and obesity in a cohort of adults living in the Mediterranean area. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018;69:1020–1029. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2018.1452900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzig MF, Löser B, Ciesielski S. Inhibition of neutrophil elastase activity by phenolic compounds from plants. Pharmazie. 2001;56:967–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton E., Jr Effect of plant flavonoids on immune and inflammatory cell function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998;439:175–182. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5335-9_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oku N, Matsukawa M, Yamakawa S, Asai T, Yahara S, Hashimoto F, Akizawa T. Inhibitory effect of green tea polyphenols on membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase, MT1-MMP. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003;26:1235–1238. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oo A, Rausalu K, Merits A, Higgs S, Vanlandingham D, Bakar SA, Zandi K. Deciphering the potential of baicalin as an antiviral agent for Chikungunya virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2018;150:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ousingsawat J, Wanitchakool P, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. Contribution of TMEM16F to pyroptotic cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:300. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0373-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D, Li N, Liu Y, Xu Q, Liu Q, You Y, Wei Z, Jiang Y, Liu M, Guo T, Cai X, Liu X, Wang Q, Liu M, Lei X, Zhang M, Zhao X, Lin C. Kaempferol inhibits the migration and invasion of rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes by blocking activation of the MAPK pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018;55:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda AC, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. SASP regulation by noncoding RNA. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2017;168:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi L, Gini E, Baci D, Tremolati M, Fanuli M, Bassani B, Farronato G, Bruno A, Mortara L. Macrophage polarization in chronic inflammatory diseases: killers or builders? J. Immunol. Res. 2018;2018:8917804. doi: 10.1155/2018/8917804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Vizcaino F, Duarte J, Santos-Buelga C. The flavonoid paradox; conjugation and deconjugation as key steps for the biological activity of flavonoids. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012;92:1822–1825. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan LD, Thiele GM, Tian J, Wang D. The development of novel therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2008;18:723–738. doi: 10.1517/13543776.18.7.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic K, Normand S, Rehman A, Delanoye-Crespin A, Chatagnon J, Delacre M, Waldschmitt N, Poulin LF, Iovanna J, Ryffel B, Rosenstiel P, Chamaillard M. A dietary flavone confers communicable protection against colitis through NLRP6 signaling independently of inflammasome activation. Mucosal. Immunol. 2018;11:811–819. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regitz C, Dußling LM, Wenzel U. Amyloid-beta (Aβ1–42)-induced paralysis in Caenorhabditis elegans is inhibited by the polyphenol quercetin through activation of protein degradation pathways. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014;58:1931–1940. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, MacFadyen JG, Everett BM, Libby P, Thuren T, Glynn RJ, CANTOS Trial Group Relationship of C-reactive protein reduction to cardiovascular event reduction following treatment with canakinumab: a secondary analysis from the CANTOS randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32814-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root M, Ravine E, Harper A. flavonol intake and cognitive decline in middle-aged adults. J. Med. Food. 2015;18:1327–1332. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2015.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JA, Kasum CM. Dietary flavonoids: Bioavailability, metabolic effects and safety. Ann. Rev. Nutr. 2002;22:19–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.111401.144957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein DC, Codogno P, Levine B. Autophagy modulation as a potential therapeutic target for diverse diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012;11:709–730. doi: 10.1038/nrd3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Miyazawa KW, Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Borghi SM, Staurengo-Ferrari L, Fattori V, Amaral FA, Teixeira MM, Alves-Filho JC, Cunha TM, Cunha FQ, Casagrande R, Verri WA., Jr Hesperidin methylchalcone suppresses experimental gout arthritis in mice by inhibiting NF-κB activation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:6269–6280. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Miyazawa KW, Staurengo-Ferrari L, Mizokami SS, Domiciano TP, Vicentini FTMC, Camilios-Neto D, Pavanelli WR, Pinge-Filho P, Amaral FA, Teixeira MM, Casagrande R, Verri WA., Jr Quercetin inhibits gout arthritis in mice: induction of an opioid-dependent regulation of inflammasome. Inflammopharmacology. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s10787-017-0356-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]