Abstract

Background

This is the third update of a review that was originally published in the Cochrane Library in 2002, Issue 2. People with cancer, their families and carers have a high prevalence of psychological stress, which may be minimised by effective communication and support from their attending healthcare professionals (HCPs). Research suggests communication skills do not reliably improve with experience, therefore, considerable effort is dedicated to courses that may improve communication skills for HCPs involved in cancer care. A variety of communication skills training (CST) courses are in practice. We conducted this review to determine whether CST works and which types of CST, if any, are the most effective.

Objectives

To assess whether communication skills training is effective in changing behaviour of HCPs working in cancer care and in improving HCP well‐being, patient health status and satisfaction.

Search methods

For this update, we searched the following electronic databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 4), MEDLINE via Ovid, Embase via Ovid, PsycInfo and CINAHL up to May 2018. In addition, we searched the US National Library of Medicine Clinical Trial Registry and handsearched the reference lists of relevant articles and conference proceedings for additional studies.

Selection criteria

The original review was a narrative review that included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled before‐and‐after studies. In updated versions, we limited our criteria to RCTs evaluating CST compared with no CST or other CST in HCPs working in cancer care. Primary outcomes were changes in HCP communication skills measured in interactions with real or simulated people with cancer or both, using objective scales. We excluded studies whose focus was communication skills in encounters related to informed consent for research.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials and extracted data to a pre‐designed data collection form. We pooled data using the random‐effects method. For continuous data, we used standardised mean differences (SMDs).

Main results

We included 17 RCTs conducted mainly in outpatient settings. Eleven trials compared CST with no CST intervention; three trials compared the effect of a follow‐up CST intervention after initial CST training; two trials compared the effect of CST and patient coaching; and one trial compared two types of CST. The types of CST courses evaluated in these trials were diverse. Study participants included oncologists, residents, other doctors, nurses and a mixed team of HCPs. Overall, 1240 HCPs participated (612 doctors including 151 residents, 532 nurses, and 96 mixed HCPs).

Ten trials contributed data to the meta‐analyses. HCPs in the intervention groups were more likely to use open questions in the post‐intervention interviews than the control group (SMD 0.25, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.48; P = 0.03, I² = 62%; 5 studies, 796 participant interviews; very low‐certainty evidence); more likely to show empathy towards their patients (SMD 0.18, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.32; P = 0.008, I² = 0%; 6 studies, 844 participant interviews; moderate‐certainty evidence), and less likely to give facts only (SMD ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐0.51 to ‐0.01; P = 0.05, I² = 68%; 5 studies, 780 participant interviews; low‐certainty evidence). Evidence suggesting no difference between CST and no CST on eliciting patient concerns and providing appropriate information was of a moderate‐certainty. There was no evidence of differences in the other HCP communication skills, including clarifying and/or summarising information, and negotiation. Doctors and nurses did not perform differently for any HCP outcomes.

There were no differences between the groups with regard to HCP 'burnout' (low‐certainty evidence) nor with regard to patient satisfaction or patient perception of the HCPs communication skills (very low‐certainty evidence). Out of the 17 included RCTs 15 were considered to be at a low risk of overall bias.

Authors' conclusions

Various CST courses appear to be effective in improving HCP communication skills related to supportive skills and to help HCPs to be less likely to give facts only without individualising their responses to the patient's emotions or offering support. We were unable to determine whether the effects of CST are sustained over time, whether consolidation sessions are necessary, and which types of CST programs are most likely to work. We found no evidence to support a beneficial effect of CST on HCP 'burnout', the mental or physical health and satisfaction of people with cancer.

Plain language summary

Do courses aimed at improving the way healthcare professionals communicate with people who have cancer impact on their physical and mental health?

What is the aim of this review? The aim of this Cochrane review was to find out if communication skills training (CST) for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer has an impact on how healthcare professionals communicate and on the physical and mental health of the patients. What types of studies did we include? We included only randomised trials (RCTs) that evaluated the impact of CST for healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses and other allied health professionals) who work with people with cancer. We included different types of CST and evaluated its impact on healthcare professionals and their patients, through the following reported outcomes: use of open questions, elicited concerns, delivery of appropriate information, empathy demonstration, use of fact contents, healthcare professional 'burnout' and patient anxiety.

What are the main results of the review? We found 17 RCTs comparing CST with no CST. The studies used encounters with real and simulated patients to measure the communication outcomes. The evidence on whether CST leads to an improvement of the use of open questions is very uncertain. However, we did show that CST probably improves healthcare professional empathy and reduces the likelihood of their giving facts only without individualising their responses to the patient's emotions or offering support. . CST probably does not have an effect on the ability of healthcare professionals to elicit concerns or to give appropriate information.

Evidence suggesting that CST might prevent healthcare professional 'burnout' is of low‐certainty and it is very uncertain whether CST has an effect on patient anxiety.

What do they mean? CST probably helps healthcare professionals to empathise more with their patients, and probably improves some aspects of their communication skills. These changes might lead to better patient outcomes; however, evidence on the latter is very uncertain and more research is needed.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. CST compared to control for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer.

| Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer | |||||

| Patient or population: Healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer Intervention: Communication skills training Comparison: No communication skills training | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Risk with CST | |||||

| Used open questions | SMD 0.25 higher (0.02 higher to 0.48 higher) | — | 796 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 1 2 3 | It is not clear whether communication skills training leads to an improvement of used open questions, because the certainty of the evidence is very low |

| Elicited concerns | SMD 0.24 higher (0.12 lower to 0.60 higher) | — | 221 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 2 | Communication skills training probably increases elicited concerns. |

| Gave appropriate information | SMD 0.08 lower (0.26 lower to 0.10 higher) | — | 489 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 3 | Communication skills training probably does not increase the delivery of appropriate information. |

| Showed empathy | SMD 0.18 higher (0.05 higher to 0.32 higher) | — | 844 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 2 3 | Communication skills training probably increases empathy demonstration |

| Gave facts only | SMD 0.26 lower (0.51 lower to 0.01 lower) | — | 780 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 2 3 4 | Communication skills training may decrease fact contents, but the certainty of this evidence is low |

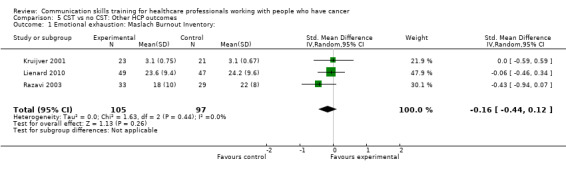

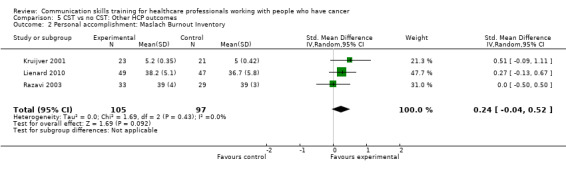

| Emotional exhaustion: Maslach Burnout Inventory: | SMD 0.16 lower (0.44 lower to 0.12 higher) | — | 202 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 2 3 | Communication skills training may decrease emotional exhaustion, but the certainty of this evidence is low |

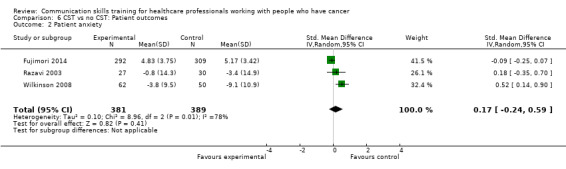

| Patient anxiety | SMD 0.17 higher (0.24 lower to 0.59 higher) | — | 770 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low 2 3 5 | It is not clear whether communication skills training leads to an improvement of patient anxiety, because the certainty of the evidence is very low |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 We downgraded two levels of certainty of evidence due to inconsistency because there are I2 = 74% in simulated patients and 43.4% between real and simulated patients 2 We downgraded one level of certainty of evidence due to imprecision because each end of confidence interval leads a different decision. 3 We downgraded one level of certainty of evidence due to risk of bias because most of trials have varied methodological limitations. 4 We downgraded one level of certainty of evidence due to inconsistency because there are I2 = 69% in simulated patients, I2 = 52% in real patients and 43,4% between real and simulated patients 5 We downgraded one level of certainty of evidence due to inconsistency evaluated with I2 = 72%

Background

This is an updated version of a review that was originally published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews in 2002 (Fellowes 2002) and updated in 2004 (Moore 2004) and 2013 (Moore 2013). Good communication between healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients is essential for high‐quality health care. Effective communication benefits the well‐being of patients and HCPs, influencing the rate of patient recovery, effective pain control, adherence to treatment regimens, and psychological functioning (Fallowfield 1990; Gattellari 2001; Stewart 1989; Stewart 1996; Vogel 2009). People with cancer have a high prevalence of psychological stress, and need emotional and social support. Hence, it is important that from the start there is adequate communication about the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment alternatives (Hack 2012). Furthermore, treatment of psychological stress may have a positive effect on quality of life (Girgis 2009).

Conversely, ineffective communication can leave patients feeling anxious, uncertain and generally dissatisfied with their care (Hagerty 2005), and has been linked to a lack of compliance with recommended treatment regimens (Turnberg 1997). Avoiding disclosing cancer as the diagnosis has been linked to higher rates of depression and anxiety and lower use of coping skills (Donovan‐Kicken 2011). Complaints about HCPs made by patients frequently focus, not on a lack of clinical competence per se, but rather on a perceived failure of communication and an inability to adequately convey a sense of care (Moore 2011; Lussier 2005). Communication issues are an important factor in litigation (Levinson 1997).

Ineffective communication is also linked to increased stress, lack of job satisfaction and emotional burnout amongst HCPs (Fallowfield 1995; Ramirez 1995). Self‐awareness, reflection and learning about communication skills may have benefits for health professionals, and prevent burnout.

Most people with cancer prefer a patient‐centred or collaborative approach (Dowsett 2000; Hubbard 2008; Tariman 2010); however, there is a minority who prefer a more task‐centred approach. Furthermore, patient preferences regarding the communication of bad news have been found to be culturally dependent (Fujimori 2009).This makes it imperative that HCPs understand the needs of the individual patient (Dowsett 2000; Sepucha 2010). The type of relationship that occurs in reality can be very different from that preferred by patients and doctors (Tariman 2010; Taylor 2011), and the literature suggests that people with cancer continue to have unmet communication needs (Hack 2005). Taylor 2011 reported that a majority of clinicians liked to include emotional issues during their interviews with people with cancer, however, clinical interviews tend to be predominated by biomedical discussion with only a minimal time dedicated to psychosocial issues (Hack 2012; Vail 2011).

The ability to communicate effectively is a pre‐condition of qualification for most HCPs (ACGME 2009; CanMEDS 2011; GMC 2009). As communication skills do not reliably improve with experience alone (Cantwell 1997), communication skills training (CST) is mandatory in many training programs, therefore, considerable effort and expense is being dedicated to CST.

There has also been increasing interest in the effect of training patients in communication skills prior to their consultation (Kinnersley 2007), including question prompts for people with cancer (Brandes 2015), and it has been suggested that it may be more effective to train both HCPs and patients in communication skills.

Description of the intervention

CST courses or workshops generally focus on communication between HCPs and patients during the formal assessment procedure (interview), and include emphasis on skills for building a relationship, providing structure to the interview, initiating the session, gathering information, explaining, planning and closure (Silverman 2005). Building a relationship may be particularly relevant with people with cancer where promoting a greater disclosure of individual concerns and feelings may enable optimum care. Breaking bad news and shared decision‐making have been other focuses of CST for HCPs involved in cancer care (Fallowfield 2004; Paul 2009).

Most approaches to teaching communication in health care incorporate cognitive, affective and behavioural components, with the general aim of promoting greater self‐awareness in the HCP. CST based on acquiring skills may be more effective than programmes based on attitudes or specific tasks (Kurtz 2005), and is considered to be more effective if experiential. The essential components that facilitate learning have been highlighted in guidelines (Gysels 2004; Stiefel 2010) and include the following.

Systematic delineation and definition of the essential skills (verbal, non‐verbal and paralinguistic). Skills that are effective in communication with people with cancer are defined (e.g. the use of open questions, incorporating a psychosocial assessment, demonstrating empathy). Pitfalls include leading questions, focusing only on the physical and failing to explore the more psychological issues and premature reassurance. However, some claim that the evidence base for this definition of essential skills is still weak (Cegala 2002; Paul 2009).

Observation of learners: through the use of learning techniques such as role‐play, participants are then given the opportunity to practice their communication skills using facilitating behaviours and avoiding blocking behaviours in a 'safe’ environment. Often, role‐playing is aided by the use of simulated patients trained to represent someone with cancer, and who can provide a range of cues and responses to communication in the role‐play, thus providing a safe opportunity for HCPs to practice communication skills without distressing patients (Aspegren 1999; Kruijver 2001; Nestel 2007).

Well‐intentioned, descriptive feedback, which may be verbal or written.

Video or audio‐recordings and review permitting self‐reflection.

Repeated practice.

Active small group or one‐to‐one 'learner‐centred' learning.

Facilitators with training and experience (Bylund 2009).

CST has been delivered in a variety of ways, for example, via sessions integrated into degree or diploma studies (e.g. Wilkinson 1999) or three‐ to five‐day workshops using actors as simulated patients (Fallowfield 1990; Heaven 1995; Razavi 2000). The optimal length for CST is under debate. Gysels 2004 argues that longer courses are more effective. However, in time‐pressured health care, there is an expectation to train effectively in less on‐site time. E‐learning (learning conducted via electronic media, typically on the Internet) and B‐learning (face‐to‐face training and online education) are methods that perhaps should be incorporated in CST. There has been some move towards a unified approach to teaching communication skills for professionals who work within the cancer field (Arraras 2015).

There is a wide variety of models and approaches to trials of CST and interpreting the data is often hampered by poor methodological quality (Fallowfield 2004), and difficulty in recruitment of HCPs (Gyawali 2015). There has been some debate about the current paradigm that supports research and education in this area (Salmon 2017; Silverman 2017) and increasing interest in including the views of patients and professionals in the design of the CST course (Solomon 2017). In 2013, the third version of this Cochrane review concluded, based on 15 randomised controlled trials, that CST courses appear to be effective in improving some types of HCP communication skills particularly related to information gathering and supportive skills, but there was insufficient evidence to determine whether the effects of CST are sustained over time, whether consolidation sessions are necessary, and which types of CST programs are most likely to work (Moore 2011) . Since then, other reviewers have reached the same conclusions in different ways (Barth 2011; Bylund 2010; Kissane 2012). Whilst some have suggested that these positive effects can be maintained over time, others have concluded that a strong evidence base for a significant effect on trial outcomes is lacking (Alvarez 2006), particularly for an effect on patient outcomes (Uitterhoeve 2010).

Why it is important to do this review

There has been much research in this area since the original Cochrane review was published, including several randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which were scant at the time of the original review. Other more recent reviews in the field have included a variety of studies with different study designs, however, none have conducted meta‐analyses of the results from RCTs. By undertaking this systematic review and keeping it up‐to‐date, we aim to critically evaluate all RCTs that have investigated the effectiveness of CST for HCPs working in cancer care, in order to enable evidence‐based teaching and practice in this important and expanding area. Furthermore, we hoped that a review and meta‐analysis of data from such RCTs would provide stronger evidence of any potential benefits that CST may have on HCP behaviour and provide guidance on the optimal methodology and length of training, as well as how to ensure that these newly acquired skills are transferred to the workplace.

Objectives

To assess whether communication skills training (CST) is effective in changing behaviour of healthcare professionals (HCPs) working in cancer care and in improving HCP well‐being, patient health status and satisfaction.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐randomised studies.

Types of participants

Types of healthcare professionals (HCPs): all qualified HCPs (medical, nursing and allied health professionals including residents (i.e. doctors on post‐graduate training courses) within all hospital, hospice and ambulatory care settings, working in cancer care. If a study included other non‐professionals but the percentage of professionals in the sample was more than 60%. If a study also included HCPs working in non‐cancer care and the percentage of HCPs working in cancer care was more than 60%. Training of intermediaries (e.g. interpreters, advocates, self‐help groups) was not considered.

Types of patients: men and women with a diagnosis of cancer, at any stage of treatment. If a study included people with other diagnoses but the people with cancer made up more than 60% of the study sample. We included studies that assessed interviews in both real and simulated patients (for definition see Appendix 1).

Types of encounters: consultations and interviews where the care of people with cancer is the main aim. We excluded trials that studied encounters where the aim was to improve the quality of informed consent or to disclose information for informed patient consent to participate in a RCT.

Types of interventions

We included only studies in which the intervention group had communication skills training (CST) (e.g. study days, teaching pack, distance learning, workshops; and including any mode of training such as audio‐tape feedback, videotape recording of interviews, role‐play, group discussion, didactic teaching), and in which the control group received nothing beyond the usual, or received an alternative training to the intervention group. We included all types and approaches to teaching, any length of training and any focus of communication between professionals and people with cancer within the context of patient care. We excluded studies whose focus was communication skills in encounters related to informed consent for research. This specific type of CST is under discussion as the subject of a separate Cochrane review.

Types of outcome measures

We included outcomes that measured changes in HCP behaviour or skills, other HCP outcomes and patient‐related outcomes at any time after the intervention. We anticipated that many of these outcomes would be measured by validated study‐specific observational rating scales and potentially subject to a high degree of inter‐trial methodological heterogeneity. Studies that only reported outcomes of changes in attitudes/knowledge on the part of the HCPs or patients without examining resulting changes in behaviour of HCPs were excluded from the review, as self‐perceived improvements have been shown to be over‐optimistic (Chant 2002; Dickson 2012).

Primary outcomes

HCP communication skills

Information‐gathering skills, such as open questions, leading questions, facilitation, clarifying and summarising

Discovering the patients perspective such as eliciting concerns

Explaining and planning skills such as giving the appropriate information, checking understanding, and negotiating procedures and future arrangements

Supportive, building relationship skills such as empathy, responding to emotions/psychological utterances; and offering support

Undesirable outcomes, including blocking behaviours such as interruptions and false reassurances, and providing facts only

Secondary outcomes

Other HCP outcomes

Burnout

Patient‐rated outcomes

-

Patient health status

Anxiety level/psychological distress

Quality of life

-

Patient Perception

Perception of HCP's communication skills: clarification, assessment of concerns, information, support, trust

Satisfaction

Outcomes of 'significant other'

-

Perception of significant other

Perception of HCP's communication skills: clarification, assessment of concerns, information, support, trust

Satisfaction

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For the original review, the following databases were searched.

CENTRAL (the Cochrane Library, 2001, Issue 3)

MEDLINE (1966 to November 2001)

Embase (1980 to November 2001)

PsycInfo (1887 to November 2001)

CINAHL (1982 to November 2001)

AMED (1985 to October 2001)

SIGLE (Start to March 2002) (Grey literature database held by British Library)

Dissertation Abstracts International (1861 to March 2002)

Evidence‐Based Medical Reviews (1991 to March/April 2001)

For the first and second updates of the review, the search strategy was modified by Jane Hayes (JH), Cochrane Gynaecological, Neuro‐oncology and Orphan Cancers (CGNOC), who extended the searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycInfo and CINAHL to Novemeber 2003 and Febuary 2012. In addition, JH searched the Database of Reviews of Effects (DARE) in the Cochrane Library in September 2011. No language restrictions were applied. (See Appendix 2, Appendix 3, Appendix 4 for search strategies).

For this (third update) review, we used the same search strategies. Jo Platt of the CGNOC extended the searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycInfo and CINAHL to May 2018:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 4)

MEDLINE via Ovid (February 2012 to May week 4 2018)

Embase via Ovid (February 2012 to 2018 week 22)

PsycInfo (February 2012 to May 2018)

CINAHL (February 2012 to May 2018)

No language restrictions were applied. We searched in Epistemonikos database for studies included in similar reviews.

Searching other resources

We searched the US National Library of Medicine Clinical Trial Registry (ClinicalTrials.gov) and handsearched the reference lists of relevant studies that we identified from the electronic searches and the conference abstracts of the annual International Psycho‐Oncology Society meetings.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the original review (Version 1), two of three review authors, Deborah Fellowes (DF), Susie Wilkinson (SW) and Philippa Moore (PM) independently applied inclusion criteria to each identified study. For the first and second update (Versions 2 and 3), two out of three review authors (PM and Solange Rivera Mercado (SRM) or Monica Grez Artigues (MGA)) independently evaluated identified studies for inclusion.

For this third update (Version 4), all articles found by the search strategy were submitted to the tool CollaboratronTM (Epistemonikos Foundation). The title and summary of all articles was reviewed independently by two of the review authors (PM, SRM, Gonzalo Bravo‐Soto (GB) or Camila Olivares (CO)) Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the review authors. We identified potentially eligible studies from the search abstracts and retrieved the full text of the articles if the review criteria were met, or if the abstract contained insufficient information to assess the review criteria.

Data extraction and management

For the original data extraction, two review authors recorded the methodology (including study design, participants, sample size, intervention, length of follow‐up and outcomes), quality and results of the included studies on a standardised data extraction form.

For the updated reviews, we designed a new data extraction form to include some specific outcomes and a 'Risk of bias' assessment. Two of the review authors extracted data independently (PM, SRM, MGA, GB, CO) and resolved any disagreement by discussion. We entered the data into Review Manager software Revman 5.3 (RevMan 2011) and checked for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The quality of eligible studies was assessed independently by three review authors (DF, SW, PM) for the original review, and by two of the review authors (PM, SRM, GB, CO) for the updates of the review. For included studies, we assessed the risk of bias as follows.

Selection bias: random sequence generation and allocation concealment

Detection bias: blinding of outcome assessment

Attrition bias: incomplete outcome data

Reporting bias: selective reporting of outcomes

Other possible sources of bias

For further details see Appendix 5.

Measures of treatment effect

Tools for assessing communication were diverse and usually consisted of validated questionnaires and scales. Data for all outcomes were continuous. We had planned to measure the mean difference (MD) between treatment arms, however most trials measured the same outcome using different scales, and so we used the standardised mean difference (SMD) for all meta‐analyses.

Unit of analysis issues

The units of analyses included the HCPs, their patients and significant others, and their encounters/conversations/interviews. Two of the review authors (PM, SRM MG, GB or CO) reviewed unit of analysis issues according to Higgins 2011, and differences were resolved by discussion. These included reports where there were multiple observations for the same outcome, e.g. several interviews involving the same HCP for the same outcome at different time points. When there were multiple time points for observation, we considered the data from the time point closest to the end of intervention as the post‐intervention measurement. This ranged from immediately post‐intervention to three months post‐intervention. We also analysed the longest follow‐up measurement for each study which ranged from two to 36 months.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted the level of attrition. Studies with greater than 20% attrition were considered at moderate to high risk of bias. For all outcomes, we attempted to carry out analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis. We did not impute missing outcome data. If data were missing or only imputed data were reported, we attempted to contact trial authors to request the missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the heterogeneity between studies by visual inspection of forest plots, by estimation of the percentage heterogeneity between trials (the I² statistic) (Higgins 2003), and by a formal statistical test of the significance of the heterogeneity (Deeks 2001). We considered a P value of less than 0.10 and an I² > 50% to represent substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We intended to examine funnel plots corresponding to meta‐analysis of the primary outcome to assess the potential for small study effects such as publication bias if a sufficient number of studies were identified, however, there were fewer than 10 studies in all meta‐analyses.

Data synthesis

We used the random‐effects model with inverse variance weighting for all meta‐analyses (DerSimonian 1986) and pooled the SMDs, presenting these results with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

To investigate heterogeneity, we carried out subgroup analyses of the primary outcomes according to staff group (e.g. doctors and nurses), patient type (e.g. real or simulated) and type of comparison (e.g. CST versus no‐CST or CST with follow‐up versus CST alone). We had intended to carry out subgroup analyses according to the type of CST e.g. didactic teaching, distance learning, role‐play workshops, however this was not possible due to the wide variety of interventions included. We will attempt subgroup analyses in future versions of this review.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis for the primary outcomes to investigate heterogeneity between studies. Three studies compared a CST intervention with no CST after giving preliminary CST to all HCP participants (intervention and control groups). Where any of these three studies contributed to meta‐analyses, we performed sensitivity analyses by excluding these data and compared the results.

Summary of findings

We presented an the overall certainty of the evidence for each outcome according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, which takes into account issues not only related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias), but also to external validity such as directness of results (Langendam 2013). We created a 'Summary of findings' table based on the methods described the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and using GRADEpro GDT. We used the GRADE checklist and GRADE Working Group certainty of evidence definitions (Meader 2014). We downgraded the evidence from 'high' certainty by one level for serious (or by two for very serious) concerns for each limitation.

High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The searches of the original review and the three updates combined retrieved 3969 records, which we subsequently screened by title and abstract. We assessed 250 full‐text papers for inclusion in this review. We excluded 175 of those articles for the reasons we have described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

In total, we included 17 trials (56 publications) that fulfilled our criteria (see the Characteristics of included studies table for details); two studies (Fallowfield 2002; Razavi 1993) from the original review (Fellowes 2002)), one additional study (Razavi 2002) from the first update (Moore 2004), and 12 from the second update (Moore 2013) (Butow 2008; Fujimori 2014 (previously Fujimori 2011); Goelz 2011; Heaven 2006; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Merckaert 2015 (previously Gibon 2011); Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007; Tulsky 2011; van Weert 2011; Wilkinson 2008;). In this third update, we included two new trials (Epstein 2017; Gorniewicz 2017) and six articles with new information of trials already included: Bragard 2010, in: Lienard 2010; Cavinet 2014, in: Razavi 2002; Fujimori 2014 and Fujimori 2014,in: Fujimori 2014; Merckaert 2015 and Leonard 2016, in: Merckaert 2015.

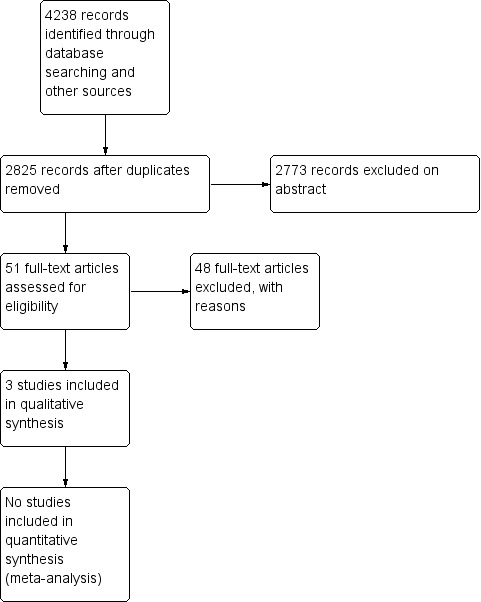

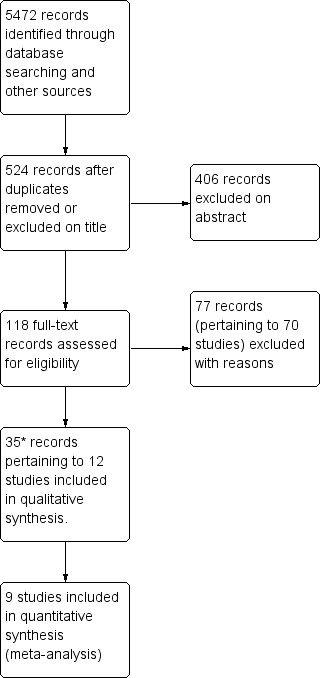

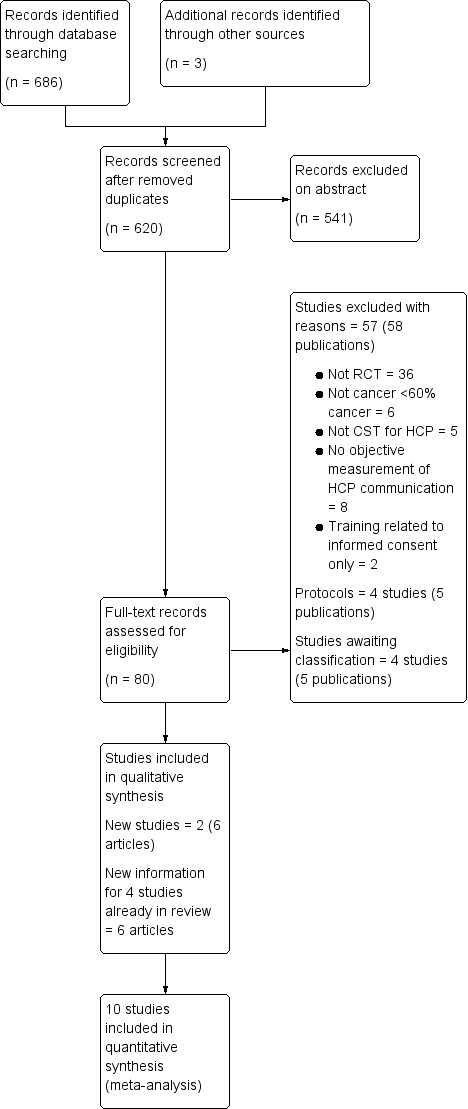

We have summarised the study selection processes in Figure 1; Figure 2; Figure 3

1.

Study flow diagram of original searches (November 2001 and November 2003)

2.

Study flow diagram of updated searches to 28 February 2012.

*Therefore, 15 studies and 44 records in total (updated search results plus original results)

3.

Study flow diagram of updated searches from February 2012 to June 2018

Included studies

We identified 17 trials in total (56 publications). All trials were published in full. We found four protocols of ongoing trials and contacted the authors but received no further information at the time of publication (Berger‐Höger 2015, De Figuereido 2015; Libert 2017; Parker 2016).

Eleven trials (Butow 2008; Fujimori 2014; Goelz 2011; Gorniewicz 2017; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; van Weert 2011; Wilkinson 2008) investigated the effect of communication skills training (CST) in the intervention group compared with a control group with no intervention.

Two trials (Epstein 2017; van Weert 2011) compared the effect of CST and patient coaching in the intervention group compared with a control group with no intervention.

One trial (Fallowfield 2002) compared two interventions in four comparative groups: CST or no training, and the provision of individual feedback or no feedback.

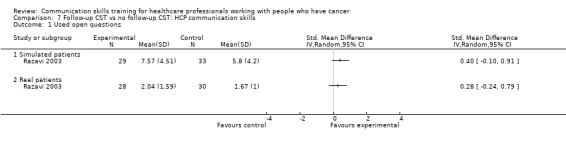

Three trials assessed the effect of a follow‐up intervention after initial training: six bi‐monthly consolidation workshops of three hours in length (Razavi 2003), four half‐day supervision sessions spread over four weeks (Heaven 2006), and CD‐ROM (Tulsky 2011).

One study compared different durations of CST (Stewart 2007).

Overall, the communication skills of 1249 healthcare professional (HCP) participants were reported in these studies and 2638 real patient encounters and 1605 simulated patient encounters were analysed. People with cancer were from various cancer care settings (63% women; mean age 61 years) and the studies enrolled the following HCPs.

Doctors (10 trials): Butow 2008 = 30 oncologists; Epstein 2017 = 38 oncologists; Fallowfield 2002 = 160 oncologists; Fujimori 2014 = 30 oncologists; Goelz 2011 = 41 mainly haematology/oncology doctors; Gorniewicz 2017 = 38 residents; Lienard 2010 = 113 residents; Razavi 2003 = 63 physicians (62% oncologists); Stewart 2007 = 51 doctors (18 oncologists, 17 family physicians and 16 surgeons); Tulsky 2011 = 48 oncologists.

Nurses (six studies): Heaven 2006 = 61 nurses; Kruijver 2001 = 53 nurses; Razavi 1993 = 72 nurses; Razavi 2002 = 116 nurses; van Weert 2011 = 48 nurses; Wilkinson 2008 = 172 nurses.

Other HCPs: one trial studied the effect of CST on radiotherapy teams, which included a mixed group of 96 doctors, nurses, physicists and secretaries (Merckaert 2015).

The majority of the trials were conducted in Europe, with the exception of Stewart 2007 (Canada), Butow 2008 (Australia); Fujimori 2014 (Japan) and Tulsky 2011; Epstein 2017; Gorniewicz 2017 (USA). The average age of the HCP participants (15 studies) was 38 years and the number of HCPs in the studies ranged from 30 to 172 (mean, 71). Women comprised approximately 36% of participants in the trials involving doctors and approximately 92% of those involving nurses. Their experience working with people with cancer ranged from < two years to 24 years. With regard to previous CST, one study reported that 47% of the participants had received > 50 hours of CST prior to the trial (Heaven 2006); two studies reported that participants had received no previous CST (Goelz 2011; Wilkinson 2008).

Most studies were conducted in the hospital outpatient setting except for two studies that involved professionals working in the community (primary care and hospices) (Heaven 2006; Wilkinson 2008) and four that involved HCPs working in an inpatient setting (Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Razavi 2002; van Weert 2011).

Type of intervention

The objective of most trials was to train the professionals in general communication skills (Fallowfield 2002; Fujimori 2014; Heaven 2006; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Stewart 2007; Wilkinson 2008). Two trials aimed to train professionals specifically to detect and respond to patients emotions (Butow 2008;Tulsky 2011). Four trials trained HCPs in giving bad news (Fujimori 2014; Gorniewicz 2017; Lienard 2010; Razavi 2003). Epstein 2017 and Goelz 2011 trained HCPs in addressing palliative care and the transition to palliative care, respectively. Kruijver 2001 concentrated on CST for nurses' admission interviews, and van Weert 2011 on CST for patient education on chemotherapy. Merckaert 2015 had a component of team communication training.

The patients' perspective was included in the design (one trial, Gorniewicz 2017) and videos of patients' perspectives were used in the intervention (two trials Gorniewicz 2017; Stewart 2007).

Most trials specified the use of learner‐centred, experiential, adult education methods by experienced facilitators (13 trials: Butow 2008; Epstein 2017; Fallowfield 2002; Fujimori 2014; Goelz 2011; Heaven 2006; Lienard 2010; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007; Tulsky 2011; van Weert 2011; Wilkinson 2008). Co‐teaching was stated in nine studies (Butow 2008; Epstein 2017; Fujimori 2014; Goelz 2011; Heaven 2006; Kruijver 2001; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2003). CST was taught in small groups (range three to 15 participants) in 12 trials (Butow 2008; Fallowfield 2002; Goelz 2011; Heaven 2006; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007; van Weert 2011; Wilkinson 2008). All small‐group studies used role‐play, although it was often unclear if the cases used were pre‐defined or true cases of the participants, and if the role‐play was between participants or with simulated patients. Two studies described individual on‐site training (Epstein 2017; Heaven 2006). Real patients were used in the preparation of one intervention (Gorniewicz 2017) and in video‐clips in van Weert 2011, but no trials used real patients during on‐site training.

Most interventions included written material (nine trials); Butow 2008; Fallowfield 2002; Goelz 2011; Kruijver 2001Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007; Wilkinson 2008), and short didactic lectures (10trials; Butow 2008; Fujimori 2014; Goelz 2011; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Wilkinson 2008). Eight trials specified the use of role‐modelling (Butow 2008; Gorniewicz 2017; Heaven 2006; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Stewart 2007; Tulsky 2011; Wilkinson 2008); and 13 trials specified the use of audio or video material (Butow 2008; Epstein 2017; Fallowfield 2002; Fujimori 2014; Goelz 2011; Gorniewicz 2017; Heaven 2006; Kruijver 2001; Razavi 1993; Stewart 2007; Tulsky 2011; van Weert 2011; Wilkinson 2008). Two trials described b‐learning: 1.5 hour video conferences as follow‐up after the CST (Butow 2008), and e‐learning prior to face‐to‐face session (van Weert 2011) Two trials described only e learning (Gorniewicz 2017; Tulsky 2011).

The participants received feedback from their tutors either verbally ;Butow 2008; Epstein 2017;Goelz 2011; Heaven 2006; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007; Tulsky 2011; Wilkinson 2008), or in writing (Epstein 2017; Fallowfield 2002). In addition, there was feedback from the simulated patients (two trials Butow 2008; Epstein 2017), and from the participants' peers (three trials Goelz 2011; Fujimori 2014; van Weert 2011; No study stated whether the feedback was structured using a checklist.

Duration of intervention

Three trials had very short training: one hour e‐learning Gorniewicz 2017 and short on‐site training with no follow‐up: Epstein 2017 (95 minutes); Stewart 2007 (six hours). Four trials included on‐site training that lasted 24 hours or less with no follow‐up intervention (10 hours: Fujimori 2014; 24 hours: Razavi 1993; 24 hours over three days:Fallowfield 2002 and Wilkinson 2008).

Seven trials included on‐site training of less than 24 hours but with follow‐up sessions, including:

three‐day course followed by four three‐hour weekly sessions with one‐to‐one supervision (Heaven 2006);

1.5‐day course followed by four 1.5‐hour monthly video conferences (Butow 2008);

one day course with a follow‐up meeting at six weeks (van Weert 2011);

19‐hour course followed by six three‐hour consolidation workshops (Razavi 2003);

18‐hour course with a follow‐up meeting at two months (Kruijver 2001);

11‐hour course followed by one‐to‐one coaching at 12 weeks (Goelz 2011);

one‐hour lecture followed by the use of a CD‐ROM for one month (Tulsky 2011).

Three trials had longer on‐site training: 38 hours (Merckaert 2015), 30 hours (Lienard 2010) and 105 hours (Razavi 2002).

Some on‐site training was on consecutive days (Fallowfield 2002: three‐day residential course; Wilkinson 2008: two days; Fujimori 2014); other on‐site training was spread over a longer period of time (Epstein 2017; Lienard 2010; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003), ranging from weekly for three weeks (Razavi 2003) to bimonthly over an eight‐month period (Lienard 2010).

Measurement of Outcomes

Primary Outcomes

Most studies measured outcomes before and after the CST (or no CST). Changes in HCP behaviour were measured in interviews involving simulated and/or real patients as follows:

simulated patients only: six trials (Butow 2008; Fujimori 2014; Goelz 2011; Gorniewicz 2017; Razavi 1993; Stewart 2007);

real patients only: five trials (Epstein 2017; Fallowfield 2002; Tulsky 2011; van Weert 2011; Wilkinson 2008);

real and simulated patients: six trials (Heaven 2006; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003).

One trial measured HCP behaviour in interviews with simulated patients only when real patients were not available, however, the data were analysed together (Wilkinson 2008). Investigators reported on a total of 1739 recordings of simulated patient encounters and 5662 recordings of real patient encounters.

The number of real patient interviews per HCP, assessed at each assessment point, ranged from one (Epstein 2017; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003) to six (Kruijver 2001). Interviews were mostly assessed using audio‐recording ( Epstein 2017; Heaven 2006; Lienard 2010; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007; Tulsky 2011), or video recording (Butow 2008; Fallowfield 2002; Goelz 2011; Kruijver 2001; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; van Weert 2011; Wilkinson 2008).

HCP communication skills were evaluated using a variety of scales (see Table 2). Almost every trial used its own unique scale; only three scales were used in more than one study: the Cancer Research Campaign Workshop Evaluation Manual (CRCWEM) (Booth 1991) (Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003); and LaComm, a French Communication Analysis Software (LaComm; Gibon 2010) (Merckaert 2015; Lienard 2010), and The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS) (Fujimori 2014; Kruijver 2001). Most studies mention that their scale had been validated. The scales had an average of 25 variables (range six to 84). Most studies used more than one rater, and the inter‐rater reliability was considered acceptable by the authors and ranged from 0.49 to 0.94.

1. Scales used to measure HCP communication skills.

| Abbreviation | Name of scale | Studies included in review that used scale | Validation reference (if any) |

| APPC | Active Patient Participating Coding | Epstein 2017 | Street 2003; Street 2007 |

| BBN | Breaking Bad News Skills rating form checklist | Gorniewicz 2017 | |

| CGAS | Common Ground Assessment Summary form | Gorniewicz 2017 | Lang 2004 |

| Com‐on | COMmunication challenges in ONcology | Goelz 2011 | Stubenrauch 2012 |

| CRCWEM | Cancer Research Campaign Workshop Evaluation Manual | Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003 | Booth 1991 |

| CSRS | Communication Skills Rating Scale | Wilkinson 2008 | Wilkinson 1991 |

| HPSD | Harvard Third Psychosociological Dictionary | Razavi 2002 | |

| LaComm | LaComm | Merckaert 2015; Lienard 2010; Razavi 2002 |

Gibon 2010 http://www.lacomm.be/index.php |

| MIARS | Medical Interview Aural Rating Scale | Heaven 2006 | Heaven 2001 |

| MIPS | Medical Interaction Process System | Fallowfield 2002 | Ford 2000 |

| MRID | Martindale Regressive Imagery Dictionary | Razavi 2002 | |

| PCCM | Patient Centred Communication Measure | Stewart 2007 | Brown 1995 |

| PTCC | Prognostic and Treatment Choices | Epstein 2017 | Back 2003;Shields 2009 |

| QUOTE | Quality of Care through Patient's Eyes | van Weert 2011 | van Weert 2009 |

| RIAS | Roter Interaction Analysis System | Kruijver 2001;Fujimori 2014 |

http://www.riasworks.com/background.html Roter 2002; Ong 1998; Ishikawa 2002 |

| SHARE | Fujimori 2014 | Fujimori 2007 | |

| Verona | Verona VR‐CoDES System | Epstein 2017 | Del Piccolo 2011;Zimmermann 2011 |

All the trials included measurement of outcomes relating to HCPs' supportive/building relationship skills (Table 3). One study measured supportive skills only for HCPs outcomes (Tulsky 2011). Other frequently measured outcomes related to:

2. Types of HCP communication skills *.

| Outcome | Definition | Examples |

| Information gathering skills | ||

| Open questioning techniques | Questions or statements designed to introduce an area of inquiry without unduly shaping or focusing the content of the response | "How are you doing?"; "Tell me how you've been getting on since we last met..." |

| Half‐open questioning techniques | Questions that limit the response to a more precise field | "What makes your headaches better or worse?" |

| Closed questioning technique | Questions for which a specific often one‐word answer such as yes or no is expected, limiting the response to a narrow field set by the questioner | "Do you have nausea?"; "How many days have you had the headaches for?" |

| Eliciting concerns | A combination of open and closed questions to make a precise assessment of the patients perspective | "Tell me more about it from the beginning..."; "What worries you the most?"; "What do you think might be happening?" |

| Clarifying/summarising | Checking out statements that are vague or need amplification and summarising (the deliberate step of making an explicit verbal summary to verify ones understanding of what the patient said) | "Could you explain what you mean by light headed?" "Can I just see if I have got it right? You have had headaches before, but over the last two week you have had a different sort of pain . . . " |

| Explanation and Planning | ||

| Giving appropriate information | The correct amount and type of information (procedural, medical, psychological) to address patient needs and facilitate understanding | ''There are three important things I want to explain today. First I want to tell you what I think is wrong, second what tests we should do, and third what treatment options are available'' |

| Checking understanding | Checking patients understanding by direct questions or asking the patient to restate in own words | "Do you understand what I mean?" |

| Negotiating | Negotiating procedure or future arrangements by taking into account the patient's concerns | ''Do you mind if I examine you today? Would you prefer it if your husband came with you?'' |

| Supportive or relationship building skills | ||

| Acknowledging concerns | Verbalising the thoughts and concerns expressed by the patient, and express acceptance | "I can see that you are worried by all this"; "I sense that you feel uneasy about having to come to see me ‐ that's ok, many people feel that way when they first come here" |

| Showing empathy | Verbalising the feelings and emotions expressed by the patient | ''I can sense how angry you have been feeling about your illness. I can understand that it must be frightening to think the pain will come back'' |

| Reassurance | To reassure appropriately about a potential discomfort or uncertainty without providing false reassurance | ''I will do my best to help you'' |

*Adapted from Silverman 2005 and LaComm.

information gathering e.g. open questions (10 studies: Butow 2008; Fallowfield 2002; Heaven 2006; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Wilkinson 2008); clarifying or summarising (eight studies: Fallowfield 2002; Goelz 2011; Gorniewicz 2017; Kruijver 2001; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003) ,and eliciting concerns (10 studies: Butow 2008; Epstein 2017; Goelz 2011; Gorniewicz 2017; Heaven 2006; Kruijver 2001; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007);

explaining and planning e.g. appropriate information giving (10 studies: (Epstein 2017; Fallowfield 2002; Fujimori 2014; Goelz 2011; Lienard 2010; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007; van Weert 2011: Wilkinson 2008), and negotiating (seven studies: Butow 2008; Heaven 2006; Lienard 2010; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007).

Secondary Outcomes

Other HCP outcomes that were measured in these studies included:

HCP health status (six trials: Butow 2008; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003);

HCP perception of the interview (three trials: Fallowfield 2002; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003);

HCP perception of their behaviour change (nine trials: Fallowfield 2002; Fujimori 2014; Lienard 2010; Merckaert 2015; Kruijver 2001; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Tulsky 2011; Wilkinson 2008);

HCP perception of their attitude change (eight trials: Butow 2008; Fallowfield 2002; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Wilkinson 2008).

We considered HCP perceptions to be very subjective outcomes and so excluded these from our review.

Patient outcomes were measured in 13 trials, 6166 patients (Butow 2008; Epstein 2017; Fallowfield 2002; Fujimori 2014; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007; Tulsky 2011; van Weert 2011; Wilkinson 2008) including:

patients' perception of the interview (11 trials: Epstein 2017; Fallowfield 2002; Fujimori 2014; Gorniewicz 2017: Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007; Tulsky 2011; Wilkinson 2008);

patients' trust in oncologist (Fujimori 2014; Tulsky 2011)

patient health status (10 trials: Butow 2008; Epstein 2017;Fallowfield 2002; Fujimori 2014; Gorniewicz 2017; Kruijver 2001; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 2003; Stewart 2007; Wilkinson 2008);

objective measure of patients communication (five trials: Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; van Weert 2011).

Two trials measured HCP communication with 'significant others' (Goelz 2011; Razavi 2003); one trial measured the satisfaction of 'significant others' (Razavi 2003).

All secondary outcomes except the objective measurement of patient communication were measured with questionnaires, most of which were developed locally and it was not always stated whether they had been previously validated (see Table 4 and Table 5). The following validated questionnaires were used:

3. Scales used for other HCP outcomes.

| Abbreviation | Name of scale | Studies included in review that used scale | Validation reference (if any) |

| MBI | Masslach Burnout inventory | Butow 2008; Fujimori 2014; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Razavi 2003 | Schaulell 1993 |

| NSS | Nursing Stress Scale | Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002 | Gray‐Toft 1981 |

| PPSB | Physician Psychosocial Belief questionnaire; | Fallowfield 2002 | Ashworth 1984 |

| SDAQ | Semantic Differential Attitude Questionnaire | Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002 | Silberfarb 1980 |

4. Scales for measuring patient outcomes.

| Abbreviation | Name of scale | Studies included in review that used scale | Validation reference (if any) |

| BSI | Brief Symptom Inventory | Stewart 2007 | Derogatis 1977 |

| CDIS | Cancer Diagnostic Interview Scale | Stewart 2007 | Roberts 1994 |

| EORTC QLQ‐C30: | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, Quality of Life Questionnaire‐Core 30 | Butow 2008; Kruijver 2001 | Aaronson 1993; Hjermstad 1995 |

| EORTCR | European Organisation of research and treatments of Cancer Outpatient Satisfaction with Care Questionaire | Merckaert 2015 | Poinsot 2006 |

| FACT | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale | Epstein 2017 | Cella 1993 |

| GHQ‐12 | General health Questionnaire | Fallowfield 2002; Wilkinson 2008 | Williams 1988 |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | Butow 2008; Fujimori 2014; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 2003 | Julian 2011; Snaith 1986 |

| HCCQ | Health Care Climate Questionairre | Epstein 2017 | Williams 1998 |

| McGill QOL | McGill Quality of Life Questionairre | Epstein 2017 | Cohen 1995 |

| NPIRQ | Netherlands Patient Information Recall Questionaire | van Weert 2011 | Jansen 2008 |

| PEPPI | Perceived Efficacy in Patient.Physician Interactions scale | Epstein 2017 | Maly 1998 |

| PIQ | Perception of Interview Questionnaire | Razavi 2003 | |

| PPPC | Patients perception of patient centeredness | Stewart 2007 | Henbest 1990 |

| PSCQ | Patient Satisfaction with Communication Questionnaire | Fallowfield 2002; Wilkinson 2008 | Ware 1983 |

| PSIAQ | Patient Satisfaction with Interview Assessment Questionnaire | Razavi 2002 | |

| PSQ‐C | Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ‐C) | Kruijver 2001 | Blanchard 1986 |

| SCNS | Supportive Care needs survey (Boyes) | Butow 2008 | Sanson‐Fisher 2000 |

| STAI‐S | State Trait Anxiety Inventory‐State | Razavi 2003; Wilkinson 2008 |

Speilberger 1983 http://www.theaaceonline.com/stai.pdf Julian 2011 |

| Single item ( Feel better?) | Stewart 2007 | Henbest 1990 | |

| THC | The Human Connection scale | Epstein 2017 | Mack 2009 |

HCP health status: Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Schaulell 1993 (used by Fujimori 2014; Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Razavi 2003);

Nursing Stress scale Gray‐Toft 1981 (used by Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002);

-

Patients' perception of satisfaction with the interview:

Patients perception of Patient Centredness Henbest 1990 (used by Stewart 2007);

Patient Satisfaction Questionairre (PSQ‐C) Blanchard 1986 (used by Kruijver 2001);

Patient Staisfaction with Communication Questionairre Ware 1983 (used by Fallowfield 2002; Wilkinson 2008);

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Outpatient Satisfaction with Care Questionairre Poinsot 2006 (used by Merckaert 2015);

Support Care Needs Survey Sanson‐Fisher 2000 (used by Butow 2008);

Perceived Efficacy of patient Physician Interaction (PEPPI) Maly 1998 (used by Epstein 2017);

The human connection scale Mack 2009 (used by Epstein 2017);

Helath Care Climate Questionairre Williams 1998 (used by Epstein 2017).

-

Patient health status:

General Health Questionnaire 12 or GHQ12 Williams 1988 (used by Fallowfield 2002; Wilkinson 2008);

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire‐30 or QLQ‐C30 Aaronson 1993; Hjermstad 1995 (used by Butow 2008; Kruijver 2001; Razavi 2002);

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Snaith 1986; Julian 2011 (used by Butow 2008; Fujimori 2014; Razavi 2003;

Speilberger's State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI‐S) Speilberger 1983 (used by Razavi 2003; Wilkinson 2008;

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale Cella 1993 (used by Epstein 2017);

McGill Quality of Life questionnaire Cohen 1995 (used by Epstein 2017);

Timing of the measurement of outcomes

Most studies measured communication skills prior to the intervention (within one to four weeks) and after a post‐intervention period (between one week and six months). Two studies had a further measurement at 12 and 15 months post‐intervention, respectively (Butow 2008; Fallowfield 2002). Three studies evaluated the effects of follow‐up CST interventions conducted between one and six months after the preliminary CST intervention (Heaven 2006; Razavi 2003; Tulsky 2011). One study measured patient outcomes for three years after intervention (Epstein 2017).

Excluded studies

We excluded 175 studies (183) articles after full‐text assessment because they did not meet our criteria for study design (see the 'Characteristics of excluded studies’ table); 132 of these studies were either not RCTs, or were not intervention studies of communication skills training. We excluded the remaining 43 RCTs for the following reasons:

13 trials not CST for HCPs;

11 CST in HCPs who did not work specifically in cancer care or where < 60% HCOs worked in cancer care;

3 trials CST was aimed at facilitating recruitment of patients to trials;

1 trial CST was only measured in the intervention group not the control group;

15 trials HCP behaviour change was not measured or was self‐assessed.

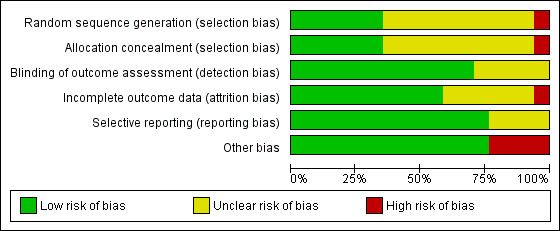

Risk of bias in included studies

We considered studies to be at a low risk of overall bias if we assessed the individual ’risk of bias’ criteria as ’low risk’ in 3/6 criteria. As a result, we considered 15 of the 17 included RCTs to be at a low risk of overall bias (Characteristics of included studies and Figure 4)

4.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Randomisation was computer‐generated in four trials (Goelz 2011; Lienard 2010; Tulsky 2011; Wilkinson 2008); by random number tables in two trials (Butow 2008; Stewart 2007); stratified block‐randomisation in one trial (Epstein 2017), and was not described in 10 trials.

Allocation concealment was described in six trials (Butow 2008; Epstein 2017; Razavi 1993; Stewart 2007; Tulsky 2011; Wilkinson 2008), and unclear (not described) in 11 trials.

Blinding

Blinding of participants was not possible in these trials, however, outcome assessment was clearly stated as blinded in 12 of the 17 trials. Most studies pre‐specified their outcomes and reported their pre‐specified primary outcomes. The following studies stated measuring some patient outcomes, however, did not report these results: Epstein 2017; Fallowfield 2002; Razavi 2002 and Razavi 2003.

Incomplete outcome data

Loss to follow‐up in relation to the primary outcomes was unclear in seven trials and considered 'low risk' in 10 trials with attrition rates ranging from 0% to 20%.

Selective reporting

In the majority of studies all pre‐specified outcomes were described. No protocols were available for Gorniewicz 2017 and Merckaert 2015. Merckaert 2015 did not report results of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire. Epstein 2017 did not report the results of all the patient questionnaires listed in the protocol.

Other potential sources of bias

Four studies reported differences between the study groups in baseline characteristics of the HCPs (Goelz 2011; Merckaert 2015; Tulsky 2011; Wilkinson 2008), or patients (Razavi 2003). In two studies that measured outcomes at several points in time, it was unclear which participant interviews were included in their analyses (Lienard 2010; van Weert 2011).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Communication skills training (CST) compared to no CST

Healthcare professionals (HCP) outcomes

Communication skills

Seven studies (Fujimori 2014; Lienard 2010; Merckaert 2015; Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003; Tulsky 2011) contributed data to these meta‐analyses: six of these studies contributed data to the 'simulated patients' subgroup and five contributed data to the 'real patients' subgroup. HCPs in these studies included 263 doctors (four studies (Fujimori 2014; Lienard 2010; Razavi 2003; Tulsky 2011), 188 nurses (Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002), and one mixed group or radiotherapy team of 80 HCPs (Merckaert 2015).

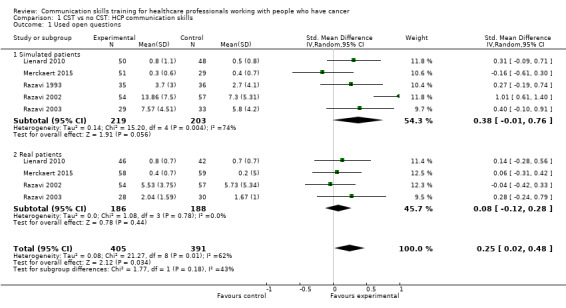

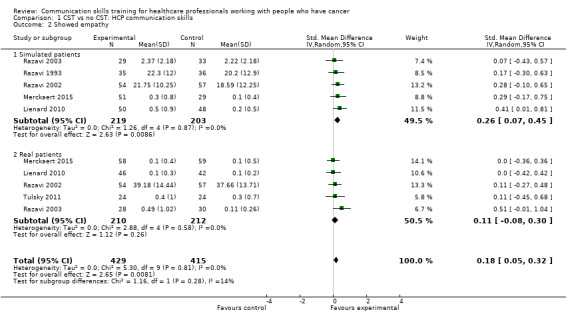

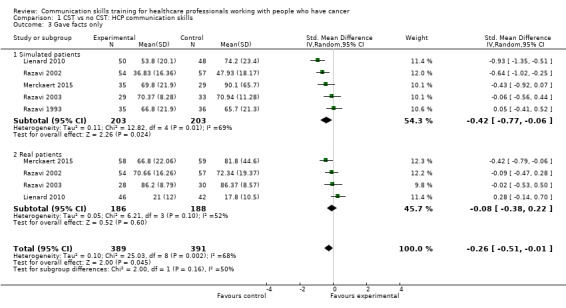

At the post‐intervention assessment, HCPs in the intervention group were more likely than the control group to:

use open questions (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.02 to 0.48; P = 0.03, I² = 62%; 5 studies, 796 participant interviews; very low‐certainty evidence Analysis 1.1;

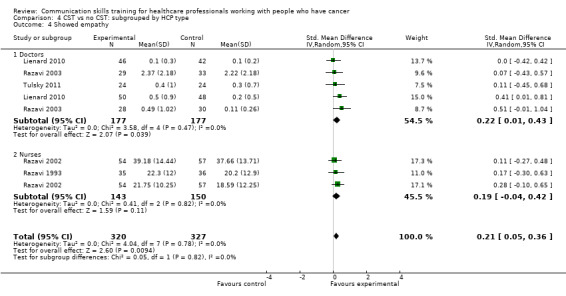

show empathy (SMD 0.18, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.32; P = 0.008, I² = 0%; 6 studies, 844 participant interviews) moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2;

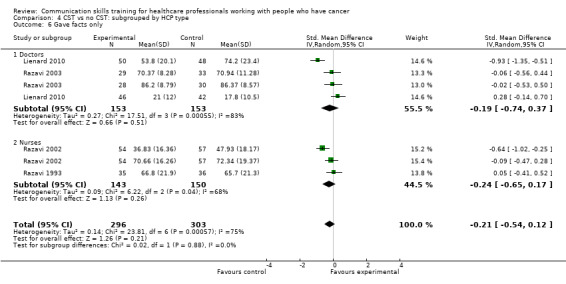

less likely to 'give facts only' without individualising their responses to the patient's emotions or offering support. (SMD ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐0.51 to ‐0.01; P = 0.05, I² = 68%; 5 studies, 780 participant interviews; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills, Outcome 1 Used open questions.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills, Outcome 2 Showed empathy.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills, Outcome 3 Gave facts only.

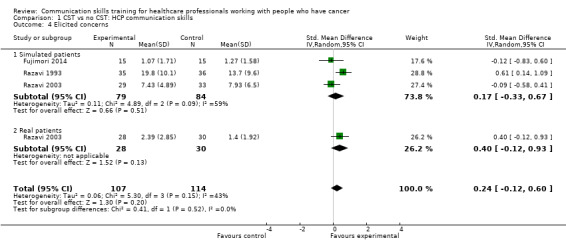

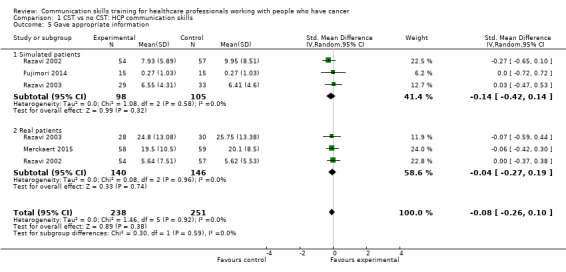

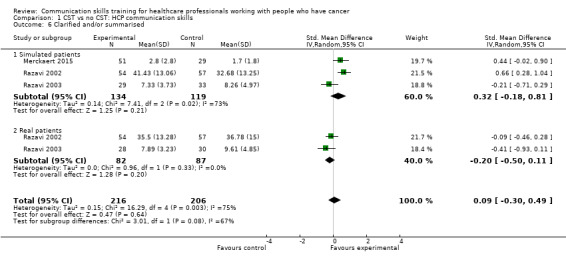

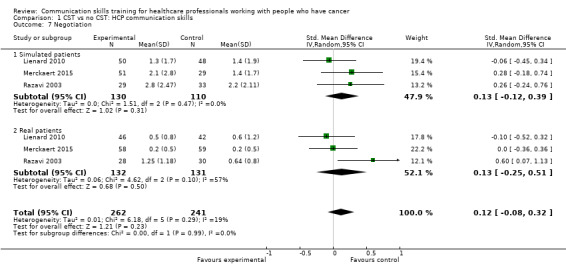

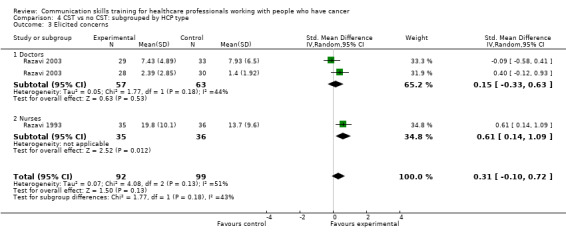

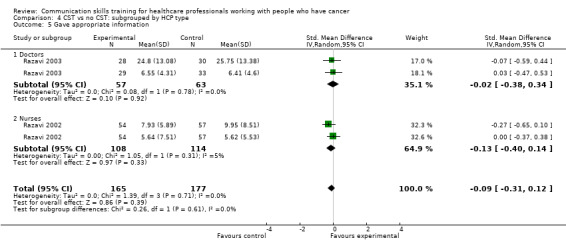

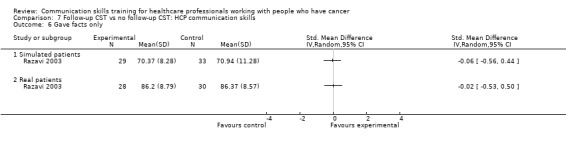

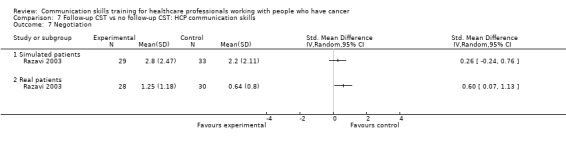

There were no differences between CST and no CST on eliciting patient concerns (Analysis 1.4) and providing appropriate information (Analysis 1.5); moderate‐certainty evidence, although eliciting concerns showed a tendency in favour of the CST intervention. No differences were found in the other HCP communication skills, including clarifying and/or summarising information, and negotiation (Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.7.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills, Outcome 4 Elicited concerns.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills, Outcome 5 Gave appropriate information.

1.6. Analysis.

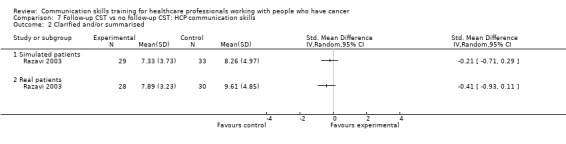

Comparison 1 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills, Outcome 6 Clarified and/or summarised.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills, Outcome 7 Negotiation.

Other HCP communication skills that were evaluated in some studies but that were either not included in our 'Types of outcome measures', or that gave insufficient data for inclusion in meta‐analyses (e.g. only gave P values), included the following.

Emotional depth: Merckaert 2015 and Kruijver 2001 reported significantly greater emotional depth in the intervention groups compared with the control groups, P = 0.03 and P = 0.05, respectively.

Empathy: Butow 2008 found less empathy in intervention group compared with the control group at six months post‐intervention (P = 0.024).

Checking that the patient understands: Kruijver 2001 reported significantly less checking of patient understanding in the CST group than in the control group; whereas Fallowfield 2002; Fujimori 2014 and Goelz 2011 reported no significant difference between the groups.

Appropriate information: there was less appropriate information giving in the CST groups than the control groups in Kruijver 2001 (P < 0.05), Lienard 2010 (P value < 0.001) and van Weert 2011 (P value < 0.01).

Team orientated focus: Merckaert 2015 reported greater team orientated focus in favour of the intervention group (P = 0.023).

Blocking behaviours: no significant effect of CST was found by Butow 2008 (P = 0.66), Heaven 2006 and Razavi 1993; whereas, Wilkinson 2008 found significantly less blocking behaviour in the intervention group (P = 0.001).

Global score: there was a significant intervention effect on global communication scores in the threes studies that measured this: Wilkinson 2008; (P value < 0.001) Goelz 2011 (P = 0.007) and Gorniewicz 2017 with a composite score (P = 0.001).

Preamble to 'Breaking bad news' (BBN): Fujimori 2014 reported a statistically significant intervention effect (P = <0.001). Gorniewicz 2017 found no effect using a composite score.

Several studies showed significant intervention effects on composite scores of different communication domains.

Epstein 2017 created a composite score of four pre‐specified communication measures (engaging, responding to patient emotions, informing patients about disease prognosis and treatments, balanced framing of decisions). His composite measure of patient‐centred communication showed a significant intervention effect (estimated adjusted intervention effect 0.34 95% CI 0.06 to 0.62; P = 0.02), but none of the four pre‐specified communication measures showed a significant difference between groups.

Fujimori 2014 found that three of four categories formed by 27 specific skills had statistically significant intervention effects (setting supportive environment P = 0.002, considering how to deliver bad news P = 0.001, emotional support P = 0.011). Only seven of the 27 specific skills showed significant intervention effects.

Gorniewicz 2017 found significant intervention effects in three composite scores on BBN: breaking bad news P = 0.004; communication related to patient emotions P = 0.034; 'determines patient readiness' to proceed P = 0.041; and four general communication composite scores: active listening (P = 0.011); addressing feelings (P value < 0.001); closing interview P = 0.002 and global P = 0.001.

van Weert 2011 found a significant intervention effect on one of seven dimensions from 67 specific communication skills: communicating realistic expectations P < 0.01. The dimension rehabilitation improvement was significantly better in the control group P value < 0.01.

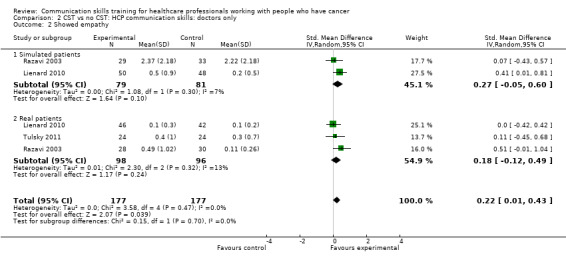

Doctors only

Four studies enrolling doctors contributed data to these subgroup analyses (Fujimori 2014; Lienard 2010; Razavi 2003; Tulsky 2011)); the results were consistent with the main findings. At the post‐intervention assessment, doctors in the intervention group were more likely than those in the control group to:

use open questions (SMD 0.27, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.50; P = 0.02, I² = 0%; 2 studies, 306 participant interviews; Analysis 2.1)

show empathy (SMD 0.22, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.43; P = 0.04, I² = 0% 3 studies, 354 participant interviews; Analysis 2.2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: doctors only, Outcome 1 Used open questions.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: doctors only, Outcome 2 Showed empathy.

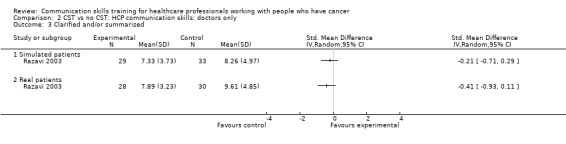

There were no differences between the intervention and control groups in the meta‐analyses of the following outcomes: clarifying and summarising, eliciting concerns, giving appropriate information and giving facts only (Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4; Analysis 2.5; Analysis 2.6).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: doctors only, Outcome 3 Clarified and/or summarised.

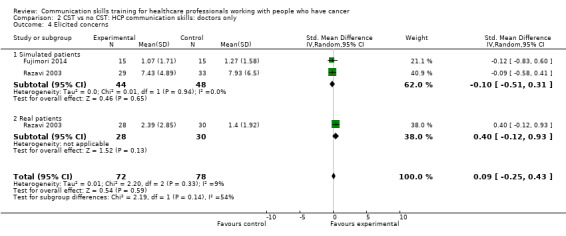

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: doctors only, Outcome 4 Elicited concerns.

2.5. Analysis.

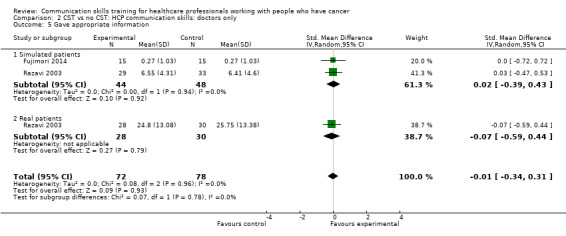

Comparison 2 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: doctors only, Outcome 5 Gave appropriate information.

2.6. Analysis.

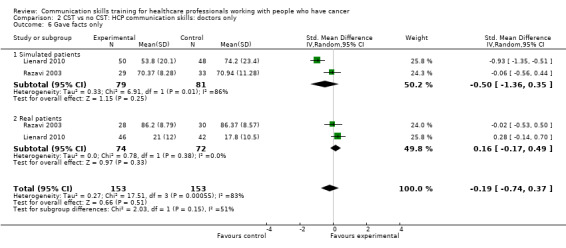

Comparison 2 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: doctors only, Outcome 6 Gave facts only.

Nurses only

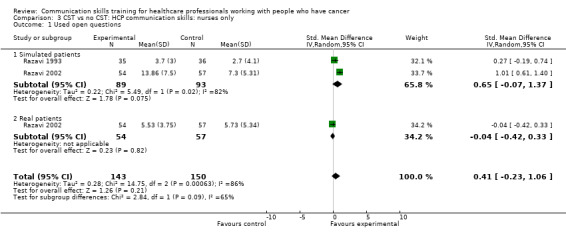

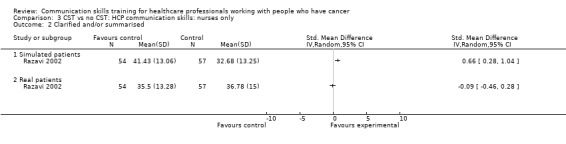

Only two studies contributed data to these subgroup analyses (Razavi 1993; Razavi 2002). At the post‐intervention assessment, there were no differences between the intervention and control groups in any of the meta‐analyses (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.4; Analysis 3.5; Analysis 3.6). For two outcomes (clarifying/summarising Analysis 3.2; and eliciting concerns Analysis 3.3), only one study contributed data (Razavi 2002)

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: nurses only, Outcome 1 Used open questions.

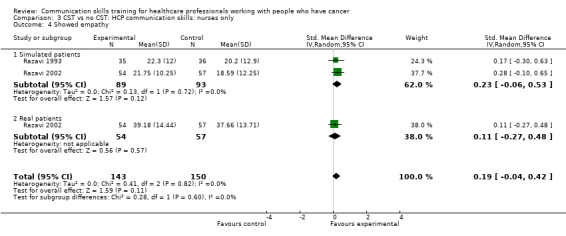

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: nurses only, Outcome 4 Showed empathy.

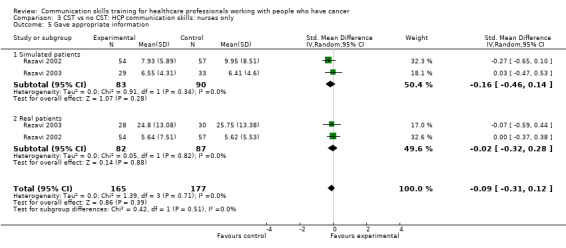

3.5. Analysis.

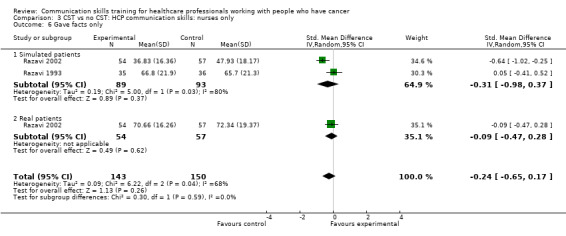

Comparison 3 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: nurses only, Outcome 5 Gave appropriate information.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: nurses only, Outcome 6 Gave facts only.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: nurses only, Outcome 2 Clarified and/or summarised.

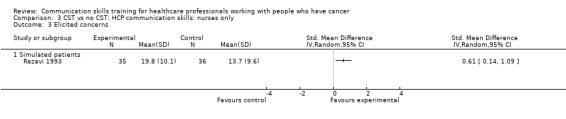

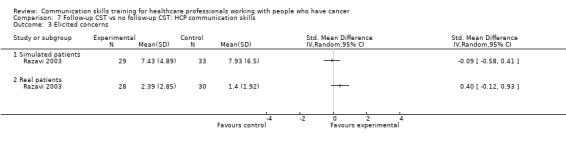

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 CST vs no CST: HCP communication skills: nurses only, Outcome 3 Elicited concerns.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses of our primary HCP outcomes to exclude studies that evaluated follow‐up interventions, i.e. Razavi 2003 and Tulsky 2011. We noted the following effects:

Analysis 1.1 the use of ’open questions’ no longer showed any difference when one study (Razavi 2003) was removed (4 studies, 676 participant interviews; SMD 0.23; 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.06; P = 0.69; I² = 71%);

Analysis 1.2: showing 'empathy' continued to show a small difference when two studies (Razavi 2003 and Tulsky 2011)were excluded (4 studies, 676 participant interviews; SMD 0.17 95% CI 0.02 to 0.32; P = 0.74; I² = 0%);

the results of the other primary analyses either remained either very similar to the original analyses, or they contained insufficient studies for meta‐analyses to be performed.

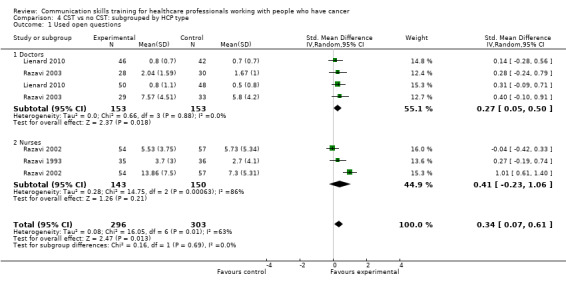

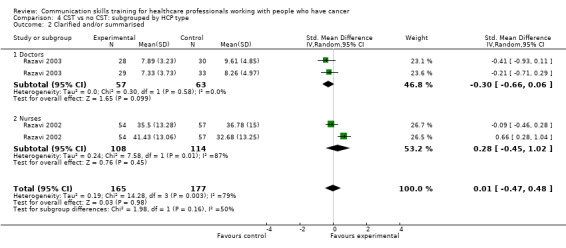

We also performed subgroup analyses to determine whether there were significant differences in primary outcomes between nurses and doctors participating in these trials (Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2; Analysis 4.3; Analysis 4.4; Analysis 4.5; Analysis 4.6), however, tests for subgroup differences were not significant.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 CST vs no CST: subgrouped by HCP type, Outcome 1 Used open questions.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 CST vs no CST: subgrouped by HCP type, Outcome 2 Clarified and/or summarised.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 CST vs no CST: subgrouped by HCP type, Outcome 3 Elicited concerns.

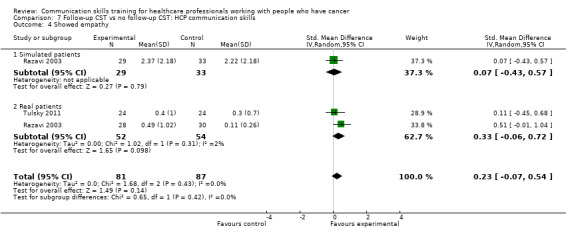

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 CST vs no CST: subgrouped by HCP type, Outcome 4 Showed empathy.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 CST vs no CST: subgrouped by HCP type, Outcome 5 Gave appropriate information.

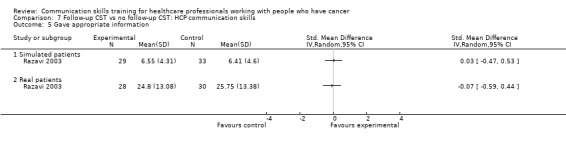

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 CST vs no CST: subgrouped by HCP type, Outcome 6 Gave facts only.

Other HCP outcomes

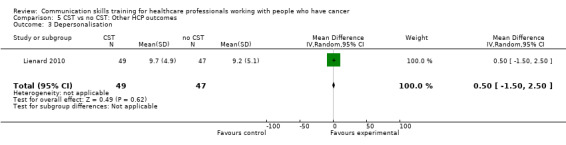

Three studies (Kruijver 2001; Lienard 2010; Razavi 2003) contributed data to meta‐analyses relating to HCP 'burnout'. Kruijver 2001 enrolled nurses and Lienard 2010 and Razavi 2003 enrolled residents (doctors in specialist postgraduate training) and doctors (62% were oncologists), respectively. Burnout was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). For the outcome 'emotional exhaustion' there was no difference in mean scores between the intervention and control groups (SMD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.44 to 0.12; P = 0.26, I² = 0%; 3 studies, 202 participant interviews: Analysis 5.1). For the outcome 'personal accomplishment' there was no difference between the intervention and control groups (SMD 0.24, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.52; P = 0.09, I² = 0%; 3 studies, 202 participant interviews; Analysis 5.2). For the outcome 'depersonalisation' with data from just one study (Lienard 2010), there was no difference between the intervention and control groups (mean difference (MD) 0.50, 95% CI ‐1.50 to 2.50; P = 0.62; 1 study, 96 participant interviews; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 5.3). Butow 2008 also reported 'burnout' and found no significant effect of CST on this outcome, however did not report these data in a usable form for this meta‐analysis.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 CST vs no CST: Other HCP outcomes, Outcome 1 Emotional exhaustion: Maslach Burnout Inventory:.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 CST vs no CST: Other HCP outcomes, Outcome 2 Personal accomplishment: Maslach Burnout Inventory.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 CST vs no CST: Other HCP outcomes, Outcome 3 Depersonalisation.

Patient outcomes

'Patient anxiety' was measured in two studies (Razavi 2003; Wilkinson 2008) using the Spielberger State of Anxiety Inventory (STAI‐S) and in one study (Fujimori 2014) using the HADS. Anxiety scores decreased in both groups in both studies after all the interviews; in Fujimori 2014 the mean reduction in anxiety scores (pre‐ and post‐interview) was significantly greater in the control group (SMD 0.17; 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.59; P = 0.41; I² = 78%, 3 studies, 770 participant interviews; very low‐certainty; Analysis 6.2).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 CST vs no CST: Patient outcomes, Outcome 2 Patient anxiety.

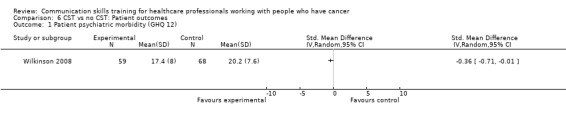

Wilkinson 2008 evaluated patient 'psychiatric morbidity', assessed by the GHQ 12 questionnaire, and found it to be significantly lower in the intervention group than the control group (one study, 127 participant interviews; SMD ‐0.36, 95% CI ‐0.71 to ‐0.01; Analysis 6.1; P = 0.05), however, this study reported significantly greater baseline anxiety in the control group.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 CST vs no CST: Patient outcomes, Outcome 1 Patient psychiatric morbidity (GHQ 12).

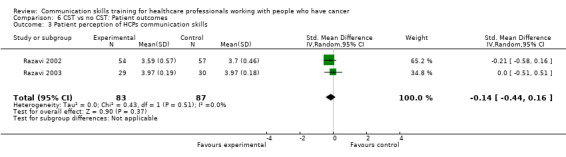

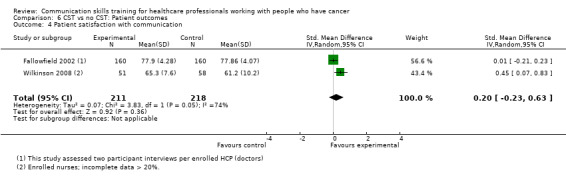

There were no differences in either the outcomes 'patient perception of HCP communication skills' (Razavi 2002; Razavi 2003) (2 studies, 170 participant interviews; SMD ‐0.14; 95% CI ‐0.44 to 0.16; P = 0.37; I² = 0% Analysis 6.3) nor 'patient satisfaction with communication' (Fallowfield 2002; Wilkinson 2008) (2 studies, 429 participant interviews; SMD 0.20; 95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.63; P = 0.36; I² = 74%; very low‐certainty; Analysis 6.4).

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 CST vs no CST: Patient outcomes, Outcome 3 Patient perception of HCPs communication skills.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 CST vs no CST: Patient outcomes, Outcome 4 Patient satisfaction with communication.

Patient outcomes that were either not included in our 'Types of outcome measures', or that gave insufficient data for inclusion in meta‐analyses (e.g. only gave P values), included the following.

Patient trust: two studies reported significantly greater patient trust in the intervention group (Fujimori 2014; Tulsky 2011) (P = 0.009 and P = 0.036, respectively).

Quallity of life: Kruijver 2001 found statistically significant improvement in only 1/30 items; and Butow 2008 found no significant differences. Epstein 2017 did not find any statistical difference using a single item scale nor on the McGill Quality of life Questionnaire nor on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale.

Anxiety: Butow 2008 reported a reduction in patient anxiety (telephone interviews) one week after the consultation in the intervention group (P = 0.021). This change was not maintained in telephone interviews three months later.

Depression: Butow 2008 found no difference in patient depression (telephone interviews) at one week after the consultation in the intervention group.

Distress: Fujimori 2014 reported that distress scores were 'significantly decreased' in the intervention group compared with the control group.

Satisfaction: Fujimori 2014 reported that distress scores were 'significantly decreased' in the intervention group compared with the control group. Merckaert 2015 reported no significant differences in satisfaction between patients of the intervention group and the control group when considering the whole team, but in relation to the nurses care, there was a higher level of satisfaction (P = 0.028) in the intervention group.

Health care utilisation: Epstein 2017 found no intervention effects in aggressive treatments and hospice use in the last 30 days of life.

Recall of information: van Weert 2011 reported a 'marginally significant' improvement in total patient recall following HCP CST. This was a composite score of six sub‐categories, only two of which has statistical difference between groups in favour of intervention.