1. Chronic neurodegeneration after TBI: Epidemiological, clinical, and neuropathological evidence

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an acute neurological disorder that requires immediate medical attention to prevent poor outcome and reduce mortality (Carney et al., 2017; Jordan, 2013). However, secondary consequences can be long-lasting and may result in a chronic brain disorder (Wilson et al., 2017), referred in this review as “chronic” TBI, with increased risk for neurodegenerative disease. Progressive cognitive decline and cerebral atrophy are the strongest evidences for the underlying chronic neurodegenerative processes after TBI. Sustained cognitive impairment and emergence of psychiatric disorders is a major concern in long-term management of TBI patients. Many clinical symptoms of long-surviving TBI patients overlap the signs of brain dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), suggesting that chronic TBI and aging-related dementias affect similar neuronal circuits playing key roles in cognition and mood, and elicit similar molecular responses involving aggregation prone molecules. Alternatively, TBI in early adulthood may exacerbate aging-associated cognitive changes (Corkin et al., 1989).

1.1. Epidemiological links between TBI and chronic, age-related neurodegenerative diseases

Epidemiological studies implicate TBI as a risk factor for AD, Parkinsonism, and frontotemporal dementias (FTD) (Wilson et al., 2017). A meta-analysis of cohort and case-controlled studies of mild and severe TBI reported an overall 63% increase in risk for developing any dementia and a 51% increase in AD, comparing individuals with head injury (with or without loss of consciousness) to those without head injury (Li et al., 2017). Barnes (Barnes et al., 2014) examined >188,000 Veterans (mean age at test = 66.8 years) and reported that TBI was associated with ~60% increase in the risk of developing any dementia (including AD, vascular dementia, FTD, and Lewy body dementia) over a 9-year follow-up. A recent study assessed 2,133 individuals with clinical history of dementia and autopsy-confirmed definite AD, 197 with self-reported TBI>1 year before onset of clinical symptoms, and reported a ~3-3.5 year earlier AD age-of-onset in the TBI(+) compared to the TBI(−) group (Schaffert et al., 2018). In individuals with comorbid conditions, including epilepsy, neuroendocrine disorders, sleep disorders, and psychiatric disease (psychosis, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD) (Jorge, 2015; Masel et al., 2001; Motzkin and Koenigs, 2015), and those with genetic predisposition for age-related neurodegenerative disorders, progressive cognitive decline after TBI indicates an ongoing (chronic) pathology and neurological dysfunction that renders the brain more susceptible to subsequent neurological insults (e.g., another TBI) (Laurer et al., 2001) and chronic neurodegeneration.

1.2. Chronic clinical outcomes after TBI: risk for chronic neurodegenerative diseases

1.2.1. Single moderate-severe TBI

Severe TBI produces cognitive deficits that can worsen over time (Cristofori and Levin, 2015). Longitudinal neuropsychiatric evaluation of patients who sustained a moderate-severe TBI revealed substantial variability in cognitive decline or quality of life over 2-5 years, despite similar age-at-injury (~15% cognitive decline (Millis et al., 2001); 7% cognitive decline (Hammond et al., 2004); ~30% cognitive decline (Till et al., 2008); ~30% decreased quality of life (Olver et al., 1996)). Ruff and colleagues (Ruff et al., 1991) described three trajectories of cognition over 6-month and 1-year follow-ups in people who sustained a single moderate-severe TBI: no change, improvement followed by decline, or progressive improvement, demonstrating potential limitations of predicting long-term cognitive outcome using test results from as late as 6 months after injury. Moderate-severe TBI also resulted in long-term deficits in the ability to sustain attention (6 years after a moderate-severe TBI) (Dockree et al., 2004) or to access declarative knowledge (“mental slowness”, 3 years after a moderate-severe TBI) (Timmerman and Brouwer, 1999), suggesting impairment of frontoparietal networks which are vulnerable to pathology of AD (Morris and Price, 2001). Patients who suffered a moderate-severe TBI present clinically years later with comorbidities associated with aging and AD, such as depression (11-26% developing depression within 1-6 years after a moderate-severe TBI) (Hart et al., 2012; O’Donnell et al., 2016; Whelan-Goodinson et al., 2009), sleep disorders (daytime hypersomnia in patients 1-3 years after a moderate-severe TBI) (Masel et al., 2001), and anxiety/PTSD (O’Donnell et al., 2013). Persistent, complex neuropsychiatric sequelae warrant research into multimodal cognitive-behavioral management of individuals who sustained a moderate-severe TBI.

1.2.2. Repetitive mild TBI and blast TBI

Repetitive mild impact TBI (rmTBI) results from multiple concussion-inducing impacts to the head, and is a significant health concern for Veterans and for athletes participating in contact sport (Koliatsos and Xu, 2015; McKee et al., 2015; Stern et al., 2013). Compared to a single severe TBI, acute pathology after mild TBI is minimal, but could prime the brain for greater injury with each subsequent mild impact (Harmon et al., 2013). Clinical symptoms of individuals exposed to rmTBI include a constellation of cognitive, behavioral, mood, and motor abnormalities (Montenigro et al., 2015) often referred to as post-concussive syndrome (PCS), and often with PTSD (Bryant and Harvey, 1999; Mac Donald et al., 2014; Schneiderman et al., 2008). Blast (non-impact) TBI (bTBI) occurs when an individual is exposed to “overpressure” air pressure waves resulting from an explosion and subsequent shock waves reflected from surrounding masses, including the ground (Cernak, 2015; Cernak and Noble-Haeusslein, 2010). Clinical consequences of bTBI include PCS with PTSD-like symptoms (DePalma, 2015; Hoge et al., 2008; Rosenfeld et al., 2013) which persist for years (Marx et al., 2009). Symptoms of PCS after blast exposure interact complexly with PTSD (Troyanskaya et al., 2015) and have been tied to underlying neuropathology (termed chronic traumatic encephalopathy, CTE) in a subset of individuals, specifically to four stages of phosphorylated-tau (p-tau) pathology severity across brain regions (McKee et al., 2013), discussed in Section 1.3.2. Clinical symptoms in individuals exposed to a single or multiple blast have similarities to FTD and overlap mood disorders (Koliatsos and Xu, 2015) hampering preclinical research due to the uniquely human psychiatric consequences that are only approximated in experimental animals (Cernak et al., 2017). Experimental models of blast TBI need to more closely mimic blast levels and numbers of exposures reported in the military - some military personnel can be exposed to thousands of low level blast injuries (Carr et al., 2015). The timing and duration of therapy in preclinical experiments should also account for possible future exposures, because many of the military personnel exposed to low level blasts remain deployed, and athletes who have suffered multiple concussive injuries continue to participate actively in contact sports.

1.3. The role of pathological protein aggregates in chronic neurodegeneration after TBI

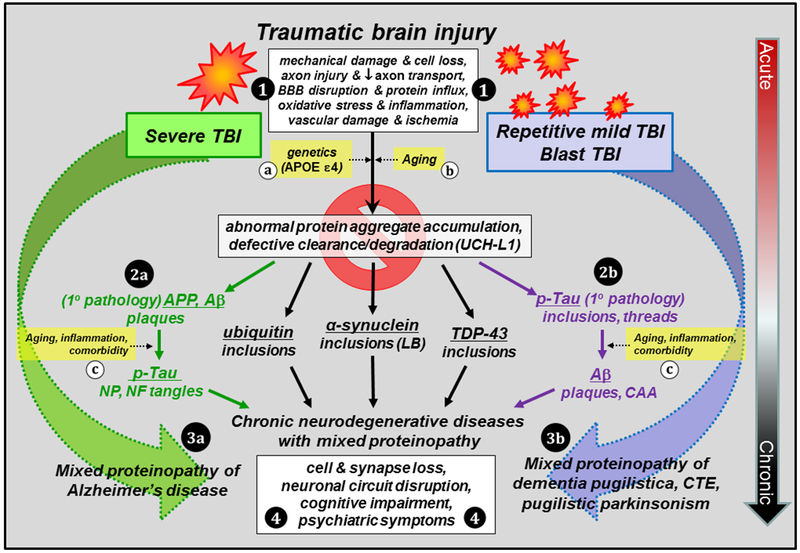

Accumulated pathological proteins involved in the hallmark lesions of chronic neurodegenerative dementing disorders (Aβ, p-tau, α-synuclein, TDP-43) are observed acutely after a severe TBI as well as after rmTBI but their connection to cognitive dysfunction and chronic neurodegeneration is not well understood. Emerging evidence suggests that different forms of TBI create unique environments conducive to aggregation of specific molecules which drive the pathogenesis of TBI-induced or -accelerated development of chronic neurodegenerative disorders (Figure 1). Answers to these questions will guide new therapy strategies to prevent chronic neurodegeneration after TBI. As highlighted in several excellent recent reviews, limitations of current clinicopathological investigations restrict the extent to which cause and effect conclusions can be made regarding the connection between TBI and the appearance of clinical dementia and associated neuropathology (Smith et al., 2013; Washington et al., 2016).

Figure 1. Consequences of single severe TBI and repetitive mild TBI: abnormal protein aggregation and risk for chronic neurodegenerative diseases.

TBI results in multiple pathological cascades involving acute cell loss, axonal injury, blood brain barrier (BBB) disruption, oxidative stress, inflammation, vascular damage and ischemia (1). There is considerable overlap in acute pathology in severe, rmTBI, and blast TBI despite the different injury mechanisms. All are characterized in part by accumulation of aggregation-prone molecules, however, the primary pathology of each depends on activation and propagation of different aggregated molecules chronically after TBI. Specifically, severe TBI is more closely associated with the activation of amyloidogenic pathway due to altered amyloid-β (Aβ) precursor protein (APP) metabolism and accumulation of Aβ peptides (2a), with secondary development of over-phosphorylated tau (p-tau) pathology, while the pathology of rmTBI and blast TBI is driven primarily by p-tau protein (2b) and secondary development of amyloidosis at more advanced age. In addition, aggregates of other proteins (ubiquitin; α-synuclein; transactive response DNA binding protein 43, TDP-43) can be initiated by all forms of TBI and contribute to the mixed proteinopathy of AD (3a) or dementia pugilistica, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and parkinsonism (3b). Development and progression of these pathologies can be influenced by genetic factors (a) and aging (b,c), inflammation and comorbidities (c; vascular disease, depression, substance abuse), as well as defective clearance mechanisms involving dysregulation of ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1 (UCH-L1) and the proteasome. Chronic neuronal injury combined with toxic intracellular inclusions ultimately results in cell death, loss of synapses and circuits, cognitive impairment, and psychiatric symptoms (4). Early intervention to prevent the initiation and/or propagation of pathological protein aggregates may be the key to breaking the link between TBI and chronic neurodegenerative diseases. Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; LB, Lewy bodies; NP, neuritic plaques; NF, neurofibrillary.

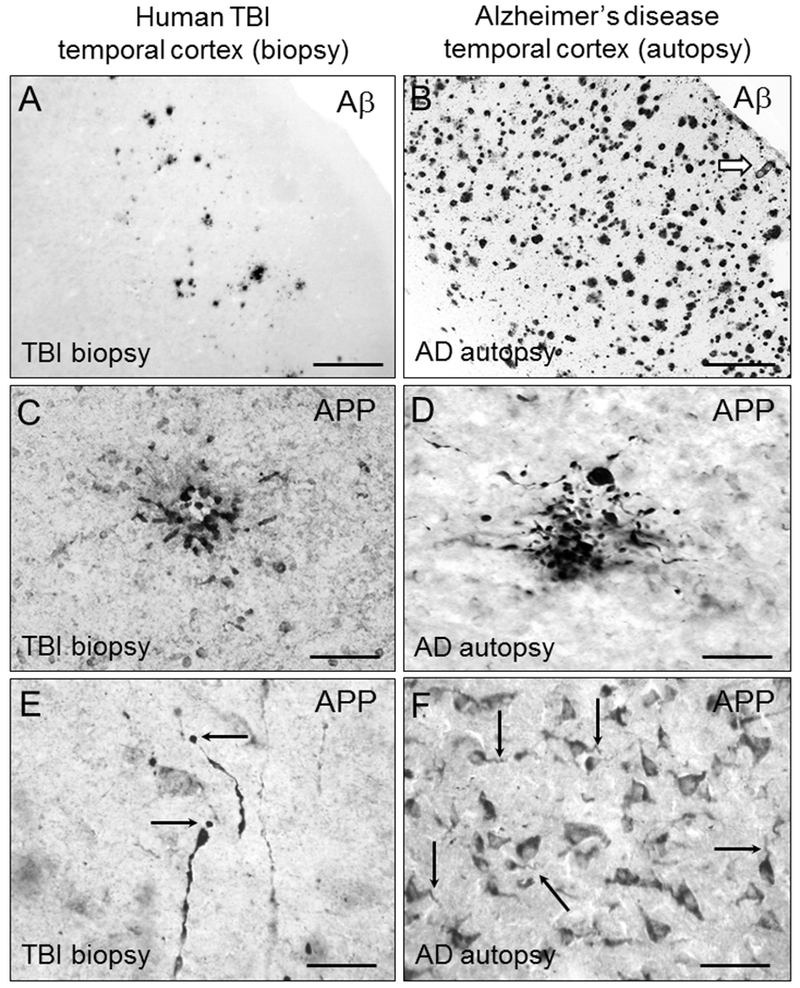

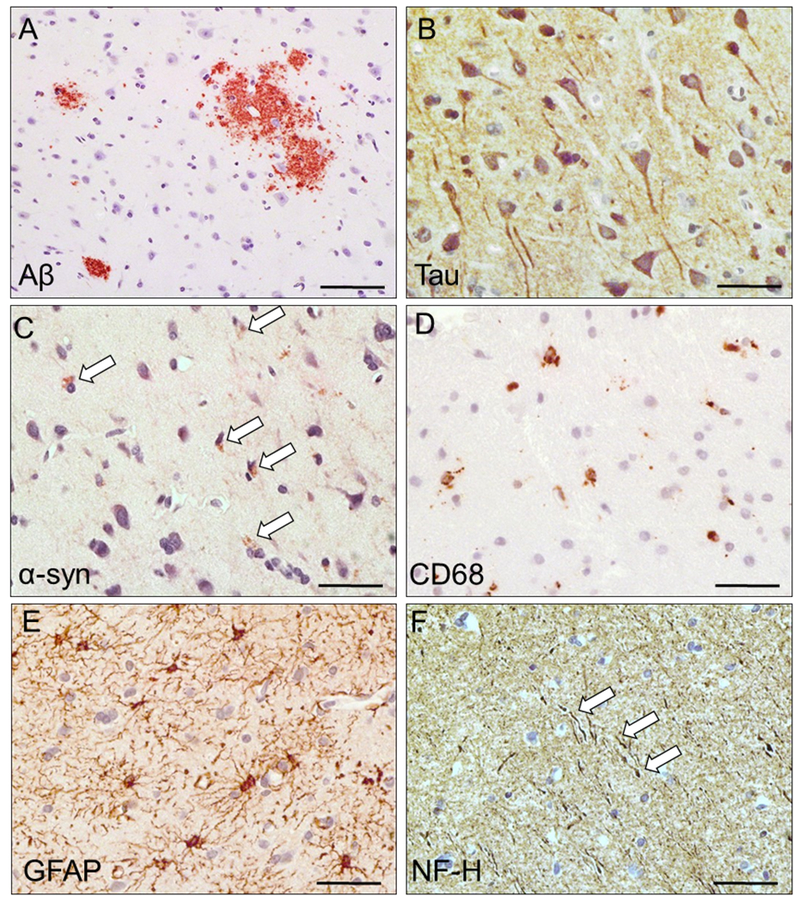

1.3.1. Accumulation of amyloid-β after TBI and risk for AD

Amyloid-β (Aβ) plays a central role in the pathogenesis of AD (Hardy and Allsop, 1991; Hardy and Higgins, 1992; Selkoe, 1991) where neuritic Aβ plaques are an AD histopathological hallmark (Mirra et al., 1991). Diffuse, Aβ42-containing neocortical plaques, similar to those described in cases of pathological aging and early stages of AD, and intracellular accumulation of Aβ precursor protein (APP) are detected ten hours after severe TBI (Figure 2) (Ikonomovic et al., 2017; Ikonomovic et al., 2004). These changes could be an acute response to injury: in a brain biopsy study of subjects with single severe TBI, neuronal APP was observed within hours to days after injury and was accompanied by diffuse Aβ42-containing plaques in ~30% of subjects regardless of age (Ikonomovic et al., 2004). The presence of Aβ plaques corresponded to greater brain concentration of soluble Aβ1-42 in the same biopsy samples (DeKosky et al., 2007) indicating an interplay between fibrillar (plaque-associated) and soluble oligomeric Aβ. In addition to plaques and neuronal APP accumulation, neurites and cells immunoreactive to p-tau, α-synuclein, and ubiquitin were detected in neocortical tissue from severe TBI patients (Ikonomovic et al., 2004). Figure 3 highlights the complex neuropathological response to severe TBI by illustrating co-existing aggregates of Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein, as well as activated microglia, astrogliosis, and axonal injury in a biopsy obtained eight hours after severe TBI. Years after single severe TBI, Aβ plaques were described as more frequent, resembling more closely compact, cored plaques of AD but with less extensive p-tau-containing neuritic processes (Johnson et al., 2012; Kenney et al., 2018).

Figure 2. Amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition and intracellular amyloid precursor protein (APP) accumulation in the temporal cortex after severe TBI and in AD.

Diffuse extracellular deposits of Aβ are scattered throughout the gray matter in a biopsy sample from an acute severe TBI patient (A), contrasting the more compact and numerous Aβ plaques in AD (B). The arrow in (B) marks an Aβ-immunoreactive blood vessel commonly observed in AD but not acutely after TBI. Intracellular APP immunoreactivity is present in clusters of dystrophic neurites in both severe TBI (C) and in AD (D). APP is also detected in damaged axons in severe TBI (E, arrows point at axonal bulbs) and in neuronal cell bodies in both TBI and AD (F, arrows point at corkscrew-appearing dendrites in AD). Illustrations are representative of results obtained in biopsy samples of temporal lobe from 20 subjects admitted to the University of Pittsburgh emergency department with severe closed head injury (GCS < 9). Brain specimens were obtained under the approval of the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board for the Clinical Core of the University of Pittsburgh’s Brain Trauma Research Center and for the University of Pittsburgh ADRC. All TBI patients underwent temporal lobe resection for decompressive craniectomy, either to relieve intractable cerebral swelling or for removal of severely traumatized brain tissue as described in (DeKosky et al., 2007; Ikonomovic et al., 2004). Time interval from injury to surgery averaged 11.25 hr ± 12.5 (range 2–72 hr). Aβ plaques were observed in eight (40%) subjects, confirming prior reports, while 16 subjects had APP aggregates in neuronal cell bodies and processes. Autopsy samples examined were middle temporal gyrus tissue from 10 cases of severe AD obtained from brain bank of the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). Neuropathological confirmation of AD diagnosis was made according to established criteria, with all cases categorized by a certified ADRC neuropathologist as Braak stage 6, with high frequency of neuritic plaques by CERAD criteria (definite AD) and high likelihood of AD by the NIA-Reagan Institute criteria. TBI patients/AD cases illustrated: biopsy sample of left temporal cortex obtained from a 39 y.o. male, 10 hours after TBI. AD autopsy sample obtained from a 77 y.o. female with a post mortem interval of 3 hr. All samples were fixed in paraformaldehyde, sectioned at 40 µm, and processed using chromogen-based immunohistochemistry using antibodies clone 4G8 (A,B; BioLegend #SIG-39220; Aβ) and clone anti-6 (C-F; gift from Athena Neurosciences; APP). Scale bar = 200 µm (A,B); 50 µm (C,D,F); 25 µm (E).

Figure 3. Complexity of acute pathological sequelae of acute severe TBI: potential seeds of chronic neurodegeneration.

Accumulation of amyloid-β (A; Aβ; diffuse extracellular plaques), tau (B; tau miss-sorting into dendrites and cell soma), and alpha-synuclein (C; α-syn; immunoreactive cells are marked by arrows), activated microglia expressing cluster differentiation factor 68 antigen (D; CD68; immunoreactive cells bodies) and increased astrocytosis (E; glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP; immunoreactive cell bodies and processes), and evidence of neurofilament disruption (F; NF-H; arrows mark dystrophic axons). See Figure 2 legend for details of sample acquisition. Patient illustrated: biopsy sample of left temporal cortex obtained from a 45 y.o. female, 8 hours after TBI. Samples were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded, sectioned at 8 µm, and processed using chromogen-based immunohistochemistry using antibodies clone 4G8 (BioLegend, Aβ), a polyclonal antibody against tau (Dako #0024), antibody clone LB509 (Abcam #ab27766, α-syn), antibody clone KP1 (Thermo #MA5-13324, CD68), a polyclonal antibody against GFAP (Dako #Z0334), and antibody clone SMI-32 (Millipore # NE1023, NF-H). Chromogen signal is brown and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (blue) to mark nuclei. Scale bar = 25 µm.

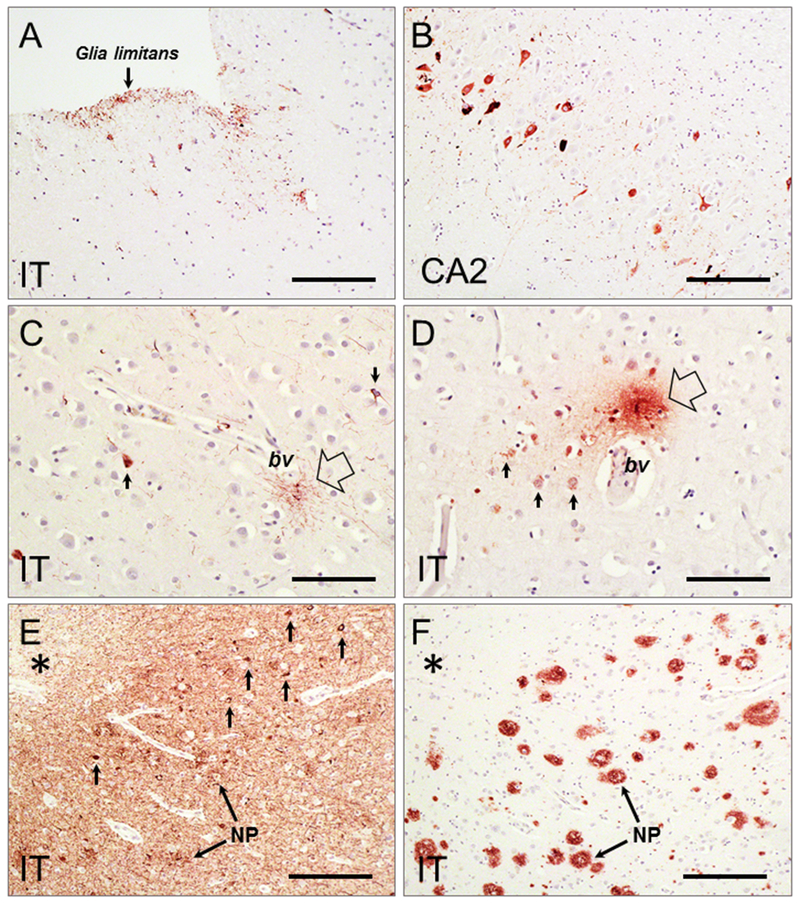

1.3.2. Accumulation of tau after TBI and risk for CTE

The microtubule-associated protein tau can undergo excessive phosphorylation and accumulate intracellularly as neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), another major pathological hallmark of AD (Braak and Braak, 1991). Unlike Aβ plaques, p-tau aggregates are not specific for AD, and are also present in neuronal and/or glial inclusions in non-AD “tauopathies” including progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), Pick disease (PiD), and CTE, the latter most closely associated with consequences of rmTBI (see Section 1.2.2.). Changes in p-tau after bTBI induction in experimental models (Goldstein et al., 2012; Huber et al., 2013) approximate observations in blast-exposed Veterans with CTE-like neuropathological changes. Perivascular tau inclusions are commonly observed after rmTBI and bTBI, as originally reported in boxers with dementia pugilistica (Geddes et al., 1999; Schmidt et al., 2001) and more recently in professional football players (McKee et al., 2009; Omalu et al., 2005). After rmTBI p-tau inclusions are also present in deep sulcal areas of the gray matter, and current neuropathological staging of CTE relies on these observations (McKee et al., 2015). Aβ plaques commonly accompany CTE neuropathology (McKee et al., 2015), either developing concomitantly with p-tau inclusions or as a secondary pathology during aging. The first reported cases of CTE in professional football players had “many diffuse amyloid plaques as well as sparse NFT and tau-positive neuritic threads in neocortical areas” (Omalu et al., 2005). Even in studies where inclusion criteria required neuropathologically diagnosed CTE (i.e., based on p-tau positivity type and distribution), Aβ plaques were frequently present, as reported by Stein and colleagues in a study of 114 neuropathologically diagnosed CTE cases of which over 50% had Aβ deposits (Stein et al., 2015). These findings are reminiscent of early reports and re-examinations of dementia pugilistica cases which emphasized presence of both p-tau and Aβ in the aftermath of rmTBI (Corsellis et al., 1973; Roberts et al., 1990). Distribution of p-tau inclusions after rmTBI differs from the typical AD NFT distribution pattern (Figure 4) (Geddes et al., 1999; Geddes et al., 1996; Hay et al., 2016; Hof et al., 1992). Other types of neuronal inclusions can be detected in individuals neuropathologically diagnosed with CTE or AD. For example, about 20% of CTE-diagnosed cases show α-synuclein positive Lewy bodies (McKee et al., 2013) and some have widespread TDP-43 inclusions in cortical and subcortical regions (McKee et al., 2010; McKee et al., 2013), resembling FTLD-TDP pathology. Disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and extravasation of blood-borne proteins could be closely tied to neuropathology detected after rmTBI (Johnson et al., 2018) as well as after severe TBI where disruption of the BBB can be long-lasting (Hay et al., 2016). A more comprehensive understanding of the complex “polyproteinopathy” of CTE (McKee et al., 2015; Washington et al., 2016) must be considered when designing multifunctional drug discovery experiments aiming to break the link between exposure to rmTBI and development of chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Studies tying neuropathological signatures of rmTBI to detailed, verified clinical history are currently ongoing (Edlow et al., 2018).

Figure 4. Diverse p-tau lesions characteristic of CTE in relation to AD pathology.

A-D: p-tau pathology (antibody clone PHF-1, gift from Dr. P. Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine) in inferior temporal cortex (IT) and hippocampal CA2 from a 59 y.o. male with a history of rmTBI (PMI = 5 hr). Samples were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded, sectioned at 8 µm, and processed using chromogen-based immunohistochemistry. Neuropathological evidence of CTE is detected as p-tau immunoreactive glial processes at subpial (A) and perivascular (empty arrow in C and D) locations, and p-tau immunoreactive neurons in hippocampus CA2 (B) and inferior temporal cortex (IT, arrows in C and D). No Aβ pathology was found in the same brain regions. E-F: Samples of IT cortex from a 62-year old case with AD (Braak stage VI; PMI = 4 hr) and a history of TBI were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded, sectioned at 8 µm, and processed using chromogen-based immunohistochemistry. Extensive p-tau pathology is detected at deep sulcal locations (E, asterisk) as dense neuropil threads, neuritic plaques (E, NP), and tangles (E, small arrows). Numerous Aβ plaques (F; antibody clone 4G8, Biolegend) are seen in a directly adjacent section (F). This illustrates the challenge faced in postmortem analyses when attempting to distinguish pathology specifically related to previous TBI in aged brains affected with advanced AD, due to overwhelming density of p-tau and Aβ pathology at time of death. Scale bar = 150 µm (A-C); 75 µm (D-F).

1.3.3. Accumulation of α-synuclein after TBI and risk for PD/movement disorders

Intracellular aggregates of α-synuclein comprise Lewy bodies (LB), the hallmark lesion in the substantia nigra in PD and in the cerebral cortex in Lewy body dementia (LBD) (Alafuzoff and Hartikainen, 2017). Exposure to TBI is a risk factor for PD, with increased age at injury, loss of consciousness, and severity of TBI contributing to greater risk (Crane et al., 2016; Gardner et al., 2014; Jafari et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2013). Genetic factors also link TBI and PD - presence of α-synuclein polymorphisms and polymorphic mixed-dinucleotide repeats were associated with reduced PD risk and improved cognitive outcome after mild TBI exposure (Goldman et al., 2012; Shee et al., 2016). An important role for α-synuclein in formation of the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex (Burre et al., 2010; Chandra et al., 2005) and regulation of presynaptic vesicular pools (Murphy et al., 2000) connects α-synuclein to neurotransmitter exocytosis, with implications for synaptic dysfunction related to dementia. Tremor and postural instability in PD and LBD are associated with impaired dopaminergic neurotransmission (Selnes et al., 2017) (reviewed by (Jankovic, 2008; Nikolaus et al., 2009)). Accumulation of α-synuclein aggregates in presynaptic terminals impairs synaptic function (Kramer and Schulz-Schaeffer, 2007; Schulz-Schaeffer, 2010) and this may contribute to chronic neurodegeneration after TBI exposure. Increased levels of α-synuclein were reported in cerebrospinal fluid of adults, infants and children in the days following a TBI (Mondello et al., 2013; Su et al., 2010), and α-synuclein immunoreactive neurons and increased oxidized α-synuclein immunoreactivity were seen in resected temporal cortical tissue hours after a severe TBI (Figure 3) (Ikonomovic et al., 2004) and in damaged axons days after a severe TBI (Newell et al., 1999; Smith et al., 2003; Uryu et al., 2007). Chronically after TBI exposure, α-synuclein positive LB were observed in a subset of CTE cases (McKee et al., 2013). Interestingly, cortical/subcortical α-synuclein positive LB were seen in the absence of amyloid and p-tau NFT in a case of self-reported TBI with loss of consciousness and clinical PD (Crane et al., 2016).

2. Experimental models of TBI-induced chronic neurodegeneration: utility and limitations

2.1. Animal models of chronic severe TBI, rmTBI, and blast TBI

Chronic behavioral dysfunction after TBI in experimental models were reviewed in Gold (Gold et al., 2013) and Osier (Osier et al., 2015) who emphasized the sparseness of studies with >2-3 months survival intervals. Four chronic (~12-month) studies reported deficits in neurological scores and spatial memory (Dixon et al., 1999; Meehan et al., 2012; Pierce et al., 1998; Shelton et al., 2008). More recently, studies reported spatial memory deficits ~12-24 months after rmTBI in C57Bl6 mice (Mouzon et al., 2014; Mouzon et al., 2018) and fluid percussion injury (FPI) in rat (Hausser et al., 2018; Sell et al., 2017), as well as PTSD-like behavioral changes 35 weeks after bTBI in rat (Perez-Garcia et al., 2018). A study using a human tau-expressing mouse reported spatial memory deficits (Morris water maze) 135 days after moderate FPI in rat (Kokiko-Cochran et al., 2018). Animal models of blast TBI are currently under development (Cernak et al., 2017; Huber et al., 2013) and several long term studies indicate chronic progressive neuropathology involving persistent expression of neuroinflammatory markers (Xu et al., 2016b) and tau (Goldstein et al., 2012; Huber et al., 2013), as well as damage to major myelinated fiber tracts (Koliatsos et al., 2011) in mouse models.

2.2. Animal models to study the role of Aβ and APP in TBI

Early studies of APP and Aβ changes after a TBI using rodent models were limited by the inability to measure the extremely low concentrations of Aβ in rodent brain. Additionally, rodent Aβ differs by three amino acids from human Aβ, complicating extrapolation to humans in the context of TBI exposure as a risk factor for AD. However, some insight into changes in this peptide were inferred by studying its parent molecule APP – these studies demonstrated marked and sustained increases in cellular APP-immunoreactivity in the rat CCI model (Ciallella et al., 2002; Murakami et al., 1998; Pierce et al., 1996). Studies of Aβ concentrations in animal models of TBI were facilitated using larger animal species (swine) which produce Aβ homologous to human, as well as human Aβ-expressing transgenic mice. In these models, sensitive anti-human Aβ antibodies are capable of detecting Aβ (and its changes) after a TBI (Abrahamson et al., 2006; Abrahamson et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2004; Smith et al., 1999). Rapid and sustained increases in Aβ concentrations were reported after moderate-severe TBI (Abrahamson et al., 2006; Abrahamson et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2004; Iwata et al., 2002; Smith et al., 1999; Uryu et al., 2002), leading to a surge of investigations examining acute (hours to days) to subacute (up to two months) time points after TBI induction using transgenic and wild type mice and rats, collectively assessed in a recent meta-analysis (Bird et al., 2016). Bird (Bird et al., 2016) emphasized the significance of acute increases in Aβ (up to one month) after experimental TBI, however, limitations were also noted, including the variability in protocols and antibodies used to measure Aβ, especially in wild type mice. In wild type rodents Aβ40 is more abundant than Aβ42 however both Aβ species are at the low detection limits of ELISA. Thus, although there has been an over emphasis on positive findings in the literature reviewed, negative findings using wild type animals (De Gasperi et al., 2012) should be interpreted with caution. Secondly, preclinical studies of APP/Aβ in rodent models should be standardized with respect to injury type, assay methodology, and age-at-injury, before definitive conclusions can be made regarding the fate of Aβ in chronic outcome after a TBI (Bird et al., 2016). Therapies to prevent or attenuate injury-induced overproduction of Aβ should be integrated into broader acting therapeutic regimen as has been done with tau (Kulbe and Hall, 2017).

2.3. Animal models to study the role of Tau protein in TBI

Due to the complexity of tau protein and variability of assay methods and antibodies employed (specifically, phospho-specific tau antibodies) the role of p-tau in the chronic outcome after a TBI is currently poorly understood (Abisambra and Scheff, 2014). Acute (24 hour and 7 days survival) moderate CCI studies using the 3×Tg mouse model of AD (human Aβ- and human tau-expressing) (Oddo et al., 2003) reported increased total tau protein in neuron soma and p-tau in axonal bulb-like structures in hippocampus and white matter (Tran et al., 2011a; Tran et al., 2011b). Suppression of Aβ production did not affect tau response to injury, suggesting the two pathologies may be driven by independent mechanisms (Tran et al., 2011a). Exposing aged human tau-expressing mice to rmTBI augmented p-tau pathology three weeks after the last impact (Ojo et al., 2013). In a subsequent study total tau and tau oligomers were found elevated in human tau mice exposed to two mTBI (Ojo et al., 2016). Several studies used wild type mice and rats to explore changes in total and p-tau at multiple time points after TBI, resulting in discrepant reports. For example, no changes in Aβ or p-tau 6-12 months after mild TBI were seen in a CHI model (Mouzon et al., 2014) and using weight drop in C57Bl/6 mice (Mannix et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2016a), in contrast to reports of Aβ, tau, and TDP-43 aggregation after rmTBI in the same mouse genotype (Petraglia et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). Recently, accumulation of cis Thr231-Pro motif tau was identified as a possible pathological form of tau early in AD and TBI (Albayram et al., 2017) - C57Bl6 mice subjected to weight-drop impact acceleration injury recovered better when this tau form was blocked (Kondo et al., 2015). Tau oligomers might also drive tau pathology observed after TBI in a rat FPI model (Gerson et al., 2016; Hawkins et al., 2013) and are an intriguing immunotherapeutic target.

2.4. Animal models to study the role of α-synuclein in TBI

Experimental TBI studies report alterations in normal and generation of pathological forms of α-synuclein. Acute generation of pathological forms of α-synuclein (conformational and nitrated α-synuclein) were observed in 24-month old mice in pericontusional cortex and axons 1 week following CCI, but limited immunoreactivity was detected at 9 or 16 weeks post-injury, or in injured, 4-month old mice (Uryu et al., 2003). Increased α-synuclein was observed in the substantia nigra in mice 1 month after CCI (Impellizzeri et al., 2016), at 2 and 6 months in rats subjected to CCI or FPI, respectively (Acosta et al., 2015; Hutson et al., 2011), and after rmTBI in mice (Levy Nogueira et al., 2017). Interestingly, α-synuclein oligomers bind to and sequester the SNARE protein synaptobrevin (Betzer et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2013), highlighting a possible mechanism by which both loss of normal α-synuclein and generation of its pathological forms impair behavioral performance in experimental models, and cognition after human TBI. Collectively, these observations suggest α-synuclein changes are important therapeutic target in TBI. We observed reduced α-synuclein in the hippocampus during the week following CCI (Carlson et al., 2017b), and reduced hippocampal synaptic abundance at 1 week after lateral FPI (Carlson et al., 2017a). In both studies, reduced levels of α-synuclein were associated with impaired SNARE complex formation. Targeting trauma-induced changes in α-synuclein at the synapse could be a promising strategy to restore normal synaptic function in the injured brain.

3. Therapies targeting aggregation-prone proteins for improved chronic recovery after TBI

Experimental TBI studies have identified pathophysiological mechanisms active during the acute/subacute phase after TBI that, to varying degrees, might progress during the chronic phase. These include excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, chronic neuroinflammation, apoptosis, and white matter degeneration in part due to calpain-mediated proteolysis of cytoskeletal proteins including tau (Bramlett and Dietrich, 2015). Changes in cerebral blood flow, epilepsy, and spreading depression could amplify secondary injury processes (Bramlett and Dietrich, 2015). Importantly, secondary injury mechanisms active after a TBI are also inducers of amyloidogenic processing of APP/Aβ and could influence p-tau and α-synuclein aggregation. Strategies using multifunctional drugs to simultaneously target different pathological pathways are more likely to improve chronic recovery from TBI than a monotherapeutic ‘magic bullet’ approach. This is particularly relevant in the context of age-related neurodegenerative disorders such as AD, where polypathology is common (Robinson et al., 2018). There is a pressing need for preclinical TBI testing of FDA-approved, repurposed drugs with pleiotropic actions targeting aggregation-prone molecules.

3.1. Targeted and multifunctional therapies for modulation of Aβ and APP in TBI

Strategies for preventing or attenuating increases in brain concentrations of Aβ peptides (and their aggregation into amyloid) include targeting of metabolic pathways involved in their production and/or aggregation directly (e.g., secretase enzymes inhibition), or indirectly using pleiotropic-acting drugs that target multiple pathological pathways initiated by TBI (e.g., neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, altered cerebral blood flow), modulation of which could also affect the production and aggregation state of Aβ peptides. Examples of both strategies are discussed below.

3.1.1. Secretase modulation of APP metabolism and Aβ production

APP is a 695-770 amino acid-long type I transmembrane protein involved in neuron development and synaptogenesis, protein trafficking, transmembrane signal transduction, and cell adhesion (Mattson, 1997). APP is cleaved sequentially by β- and γ-secretases to release Aβ peptides (amyloidogenic APP metabolism) as well as other bioactive molecules (Turner et al., 2003), or alternatively by α-secretase, precluding formation of Aβ (non-amyloidogenic APP metabolism; (Selkoe, 2001)) and releasing potentially neuroprotective/neurotrophic soluble APPα (Peron et al., 2018; Turner et al., 2003). APP mRNA and protein expression is upregulated acutely after experimental TBI (Ciallella et al., 2002; Murakami et al., 1998; Pierce et al., 1996), resulting in axonal accumulation of APP (Gentleman et al., 1993; Ikonomovic et al., 2004; McKenzie et al., 1994) which was linked to subsequent amyloidogenic processing (Chen et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2004; Iwata et al., 2002; Stone et al., 2002) and production of Aβ and other bioactive fragments, including soluble APPβ and APP intracellular domain (AICD), a C-terminal APP fragment with nuclear signaling functions (Haass et al., 2012). Secretases are also altered by TBI, with injury-associated increases in both β- and γ-secretases (Blasko et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2013; Cribbs et al., 1996; Nadler et al., 2008; Uryu et al., 2007), and potentially beneficial α-secretase (Del Turco et al., 2014). Targeting secretases to shift APP processing towards the non-amyloidogenic pathway is a logical therapeutic strategy for breaking the link between TBI and AD. However, experimental studies aiming to suppress β- and γ-secretases or enhance α-secretase after TBI have been only variably successful. For example, C57Bl6 mice (12 months old) deficient in BACE1 (BACE1−/−; (Cai et al., 2001)) had reduced spatial memory deficits and tissue loss after CCI (BACE1−/− vs BACE1+/+; (Loane et al., 2009)), not observed in younger mice (Mannix et al., 2011). Subacute (21-day) pharmacological inhibition of γ-secretase reduced tissue loss and attenuated spatial memory deficits after CCI in C57Bl6 mice (Loane et al., 2009) possibly involving Aβ-dependent and Aβ-independent effects (Winston et al., 2013). Several studies explored potentially neuroprotective effects of sAPPα (Mattson, 1997; Mockett et al., 2017; Plummer et al., 2016) and reported that sAPPα reintroduction was protective after experimental TBI in APP−/− mice (Corrigan et al., 2012a, b, c). Thornton (Thornton et al., 2006) also observed marked protective effects of sAPPα therapy in a rat weight drop model of TBI. In a study by Siopi and colleagues (Siopi et al., 2013), a single intraperitoneal injection of etazolate, an α-secretase activity enhancer currently in clinical trials for AD treatment (Vellas et al., 2011), administered in adult male Swiss mice exposed to CHI had protective effects sub-acutely (Siopi et al., 2013). The complexity of APP metabolism and the lesser known functions of non-Aβ APP C-terminus fragments, as well as detrimental effects of secretase inhibition in animal brain and spinal cord injury models (Mannix et al., 2011; Pajoohesh-Ganji et al., 2014) and inconclusive AD clinical trials targeting secretases (Barao et al., 2016) indicate the need for more sophisticated understanding of non-APP secretase substrates and the response of secretases and their substrates to brain trauma before effective therapies can be developed and integrated with comprehensive TBI management programs. Studies examining time points remote from experimental TBI with therapies targeting secretases are warranted, with attention paid to the timing and duration of treatment – these considerations will be in part determined by the experimental model used. For example, transgenic mouse models of cerebral amyloidosis often have presenilin mutation that enhances the activity of γ-secretase; in this scenario therapies targeting secretases would need to be administered continuously, due to continuous mutation-induced overactivity of γ-secretase. On the other hand, animals naturally producing physiological levels of human Aβ (e.g., swine) might respond well to more abbreviated secretase modulation therapy after TBI.

3.1.2. Aβ immunization and small molecule amyloid beta binding compounds (SMAβBA)

An attractive strategy to break the link between the consequences of a TBI and later development of AD-like amyloidosis is to target Aβ directly for removal using anti-Aβ immunization. Anti-Aβ vaccination and immunization with anti-Aβ antibodies were tested in AD clinical trials (van Dyck, 2018), but were problematic because of side effects (Liu et al., 2015b) due to trials being initiated late in the AD clinicopathological course. Risk of AD after severe or rmTBI indicates that patients with a history of head injury are a potential population for Aβ immunotherapy clinical trials; in this regard there is a need for robust, reliable, non-invasive biomarker assay/s to identify with high confidence TBI subpopulations at highest risk, keeping in mind that autopsy studies reported AD pathology only in ~30-40% of people with a history of severe TBI. A similar concept emerged in studies of rmTBI testing anti-tau (including tau immunization) therapies (Section 3.2). An alternative approach to optimizing Aβ immunization strategies is by combining them with other complementary drugs. One candidate family of compounds are derivatives of Congo red termed small amyloid-β binding agents (SMAβBA) that interfere with Aβ aggregation, reducing the pool of fibrillized Aβ in transgenic APP overexpressing mouse brain (Cohen et al., 2009), which could be combined with Aβ immunization to facilitate removal of Aβ from brain. As with secretase-modulation therapies, the timing/duration of treatment in experimental studies will in part be determined by choice of experimental model. Transgenic mice (over-) expressing APP and/or tau mutations may be more suitable for modeling TBI superimposed on genetically predisposed amyloidosis of AD or non-AD tauopathies, while human Aβ-producing non-transgenic species, such as swine, more closely model TBI as a risk for sporadic AD. These considerations raise important questions about the degree to which therapies must be individualized for optimal efficacy.

3.1.3. Multifunctional therapies with Aβ reducing effects in TBI

3.1.3.1. Statin therapy

Statins are FDA-approved drugs in clinical use to treat hypercholesterolemia (Taylor et al., 2013). Beneficial effects of statins in acute and chronic neurological disorders resulting from TBI and/or ischemia are associated with their broad-ranging mechanisms of action in the brain (Stuve et al., 2003). Statins inhibit HMG coenzyme A reductase to reduce cholesterol synthesis, but also reduce isoprenylation of Ras and Rho GTPases causing changes in cytoskeletal organization, adhesion of circulating chemokines, endocytosis, receptor signaling, cell cycle progression, and gene expression (Liao and Laufs, 2005). Beneficial effects of statins on secondary injury processes, including effects on Aβ, were reported in experimental models of AD and TBI, with statins rapidly reducing Aβ production in vitro and in vivo (Hoglund et al., 2006). Aβ-reducing effects of statins are associated with improved cerebral vascular perfusion (Paris et al., 2003) and reduced oxidative stress and inflammation (Wang et al., 2011). Thus, statin therapy is likely to produce anti-inflammatory, neuro-protective and neuro-regenerative effects, in addition to suppressing trauma-induced elevations in neurotoxic Aβ. Statins therapy was reported beneficial in experimental TBI models during the acute/subacute phase (15 days to 3 months) (Lim et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2004; Mahmood et al., 2009; Mountney et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2014; Vonder Haar et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2015), however, as noted by Peng (Peng et al., 2014), interpretation of many TBI/statin intervention studies are limited by poor methodology. Several studies examined the effects of statins administered in combination with other drugs and report synergistic effects of these combinations (Chauhan and Gatto, 2010; Chen et al., 2008; Darwish et al., 2014; Mahmood et al., 2008; Mahmood et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2014) underscoring the potential of multidrug therapy with pleiotropic drugs. We developed a preclinical model of TBI-induced elevation in brain Aβ in a genetically modified mouse wherein the human Aβ coding sequence is ‘knocked-in’ to the endogenous mouse APP gene controlled by its endogenous promoter (Reaume et al., 1996). In this humanized Aβ (hAβ) model, TBI-induced changes in human Aβ can be studied without confounding effects of constant APP/Aβ over-production characterizing transgenic APP-overexpressing mice. We administered by oral gavage 3 mg/kg simvastatin starting 24 hours after moderate/severe CCI injury (1.2mm depth) and daily thereafter for 14 days, and reported neuroprotection and reduced microglial activation (Abrahamson 2006) as well as reduced spatial memory deficits correlated with reduced brain soluble Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 peptides (Abrahamson et al., 2009). Additionally, reductions in regional cerebral blood flow after CCI in hAβ mice were blunted by simvastatin with concomitant Aβ-lowering effects (Figure 5) (Abrahamson et al., 2013). An important consideration in studies using statin therapy is potential adverse effects of chronic statin usage on brain cholesterol levels, as well as the possibility of prophylactic treatment with statins for individuals at high risk for exposure to TBI (e.g., military personnel and contact sport athletes). These considerations need to be explored in well-powered studies examining the chronic consequences of either single severe TBI or rmTBI.

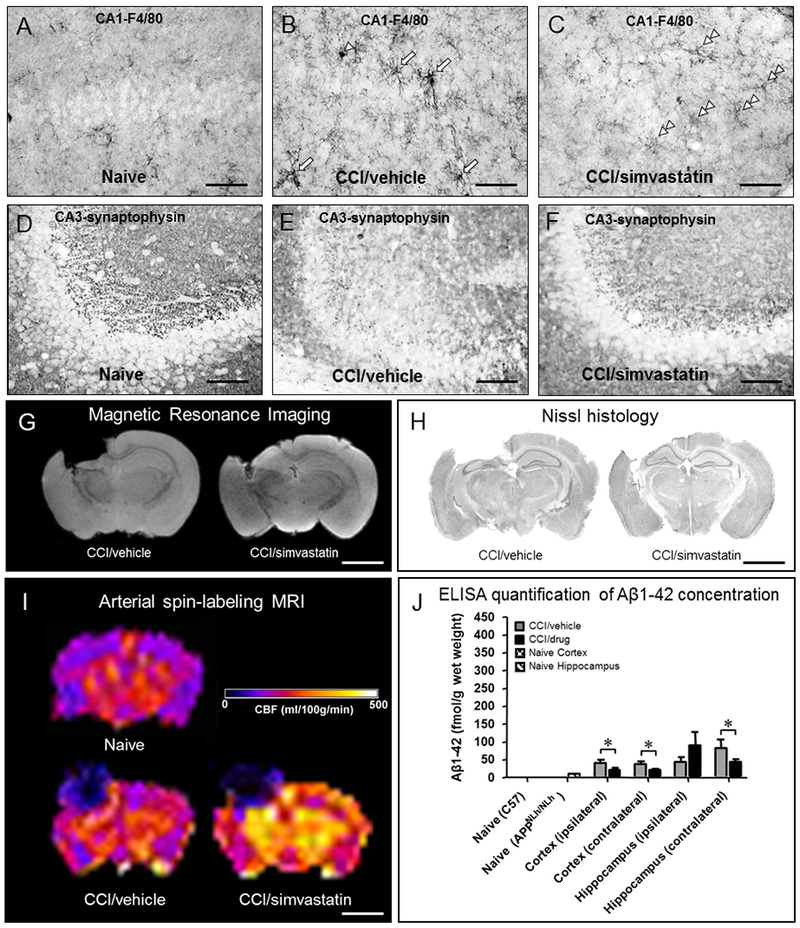

Figure 5. Multiple beneficial effects of simvastatin therapy after TBI in humanized Aβ mice.

Human amyloid-β (Aβ) mice (see text for description of mouse model) were exposed to vertically directed CCI injury and administered 3 mg/kg simvastatin (Merck) or vehicle (3% methylcellulose) daily by oral gavage. After a 14-day survival interval (A-F) whole brains from CCI-injured mice were preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde and assessed histopathologically in relation to non-surgically manipulated (Naïve) mice. Microglia activation (A-C; rat monoclonal antibody clone A3–1 against mouse macrophage glycoprotein F4/80; abcam #ab6640) induced in CA1 hippocampus after CCI injury (B; compare to naïve mice, A) is suppressed in mice receiving simvastatin. Simvastatin therapy also resulted in preservation of synaptic densities assessed using mouse monoclonal antibody clone SVP-38 (Sigma #S5768) in CA3 hippocampus after CCI injury (F) compared to a marked decrease in CCI-injured, vehicle-treated mice (E) relative to naïve mice (D). Simvastatin therapy also resulted in greater tissue preservation assessed in vivo using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; G) and ex vivo (Nissl histology; H). Arterial spin labeling MRI was used to assess cerebral blood flow (CBF) in CCI-injured relative to naïve mice 21 days after surgery; in this study, CCI-injured, simvastatin-treated mice had markedly higher regional CBF rates compared to CCI-injured, vehicle-treated and naïve mice (I). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) quantification of Aβ showed that CCI-induced elevations in Aβ concentration (relative to naïve) are suppressed by simvastatin treatment (*p<0.05) at 21 days after CCI injury. Collectively, these examples demonstrate how a single drug with pleiotropic actions can have beneficial effects on a wide range of pathology after brain injury, including effects on neuroinflammation, synaptic preservation, neuropil preservation, preserved/enhanced CBF, and suppression of aggregation prone Aβ peptides. Scale bar = 40 µm (A-F); 2 mm (G-I).

3.1.3.2. Environmental enrichment

Exposure of rodents to an enriched environment stimulates exploratory and social behavior, and increases sensory input, similar to multimodal physiotherapeutic intervention strategies used to treat patients who sustained a TBI, and is therapeutic in several experimental models of TBI (Bondi et al., 2014). EE exposure improves neurological recovery even after a delay between injury and therapy (Bondi et al., 2014) which has implications for treatment timing. Exposure of aged, naïve (non-injured) transgenic mouse models of cerebral amyloidosis to EE was reported to modify their AD phenotype by alleviating plaque burden, and lowering both Aβ concentration (Ambree et al., 2006; Costa et al., 2007; Herring et al., 2011; Lazarov et al., 2005) and accumulation of p-tau (Lahiani-Cohen et al., 2011). EE exposure also stimulates neurogenesis (Hu et al., 2010) and reduces cognitive deficits (Ambree et al., 2006; Lazarov et al., 2005), the latter correlating with reductions in brain Aβ load (Berardi et al., 2007; Costa et al., 2007; Cracchiolo et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2010; Lazarov et al., 2005; Maesako et al., 2012; Mainardi et al., 2014; Verret et al., 2013). Exposure of rats to 90 days of EE resulted in marked reductions in brain atrophy and improvement on the Barnes maze test of spatial memory following FPI in adult rat (Maegele et al., 2015) indicating that prolonged exposure to EE is a promising therapeutic strategy. As a non-invasive therapy approach, EE could be combined with pharmacotherapy for improved long-term recovery after TBI, as has been explored in several recent studies (Bondi et al., 2014), which would avoid potential drug interaction complications.

3.2. Therapies targeting tau in TBI

In contrast to the known accumulation of pathological p-tau as a consequence of TBI in humans, there is limited understanding and conflicting reports of the response of tau protein to TBI in preclinical models. Given the wide range of secondary injury processes activated by a TBI, it is unclear whether therapies targeting tau can improve outcome in humans who sustained a TBI. However, anti-tau therapy is applicable to rmTBI, where pathological consequences seem to center primarily around tau (CTE). Tau vaccination is only emerging as potential treatment strategy for tauopathies. Studies in the 3× transgenic mice (with mutations in APP, presenilin, and MAPT genes) immunized with p-tau extracts from autopsied AD brains have shown encouraging results (Dai et al., 2018), and immunization trials in humans are currently ongoing (Braczynski et al., 2017). If successful, tau immunization could be considered for treatment in early stages of CTE. Tau deletion in mice resulted in functional deficits and neurodegeneration, and was further exacerbated in brain injury (Dawson et al., 2010). However, reducing tau over-phosphorylation is a promising approach. Recent reports also indicate that specific tau forms could be pathologically active after a TBI, with potential benefits of cis p-tau antibody treatment for suppression of pathology and behavior deficits after TBI in mice (Albayram et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2016). Novel agents to stabilize microtubules and suppress dissociation of tau from microtubules are also promising and could be beneficial after TBI. For example, tau transgenic mice (uninjured) treated with epothilone D showed attenuated tau pathology and improved cognition compared to wild type mice (Brunden et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012a). Interestingly, memantine administered after rmTBI in adult C57Bl6 mice reduced markers of tau phosphorylated at Thr231 (Mei et al., 2018). Other studies report p-tau-reducing effects of antioxidants (Du et al., 2016), PP2A activation (Shultz et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2016), DHA treatment (Begum et al., 2014), endocannabinoids (Zhang et al., 2015), and JNK inhibition (Tran et al., 2012). Anti-phosphorylation strategies for prevention of tau aggregation need to be considered with caution as molecular pathways responsible for phosphorylation of tau also phosphorylate other proteins. In this regard, preclinical experiments targeting tau, or its phosphorylation, need to careful investigate timing and duration of treatment, to maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing potential side effects.

3.3. Therapies targeting α-synuclein in TBI

Therapeutic strategies to attenuate TBI-induced alterations in α-synuclein should be matched to the specific pathological response after TBI for maximum therapeutic effect. In the context of PD, utilizing small interfering RNA proved successful in reducing endogenous α-synuclein expression in mice and primates (Lewis et al., 2008; McCormack et al., 2010; Sapru et al., 2006). Such a therapeutic strategy utilizing RNA interference could prove efficacious in preventing or lowering chronic TBI-induced increased expression of α-synuclein and reducing neurodegeneration. However, a different therapeutic strategy may be needed to address TBI-induced reductions in hippocampal α-synuclein important for neurotransmitter exocyctosis (Carlson et al., 2017a; Carlson et al., 2017b). Daily lithium treatment increased wildtype α-synuclein abundance and improved SNARE complex formation in the hippocampus after CCI injury (Carlson et al., 2017b) and should be explored further in mouse models of amyloidosis. Another therapy potentially useful in preventing development of PD in chronic TBI targets dopamine hypofunction which has been hypothesized to contribute to cognitive morbidity after TBI (Bales et al., 2009). Impaired evoked dopamine release is a well-established response following experimental TBI. High-potassium evoked striatal dopamine release was impaired at 1 and 2 weeks following CCI injury (Shin et al., 2011; Shin and Dixon, 2011), and measurements of medial forebrain stimulation-evoked dopamine release revealed reduced striatal dopamine neurotransmission 2 weeks after CCI injury (Wagner et al., 2009), and up to 8 weeks following severe FPI (Chen et al., 2015). Mechanisms for persistent impaired of dopamine release have not been fully elucidated, but TBI-induced changes in the abundance and generation of pathological forms of α-synuclein may contribute to dopamine release dysfunction.

3.4. Therapies promoting degradation of pathological protein aggregates in TBI: UCH-L1 and the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway

The consequences of TBI and pathological processes in neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by accumulation of abnormal protein aggregates including APP/Aβ, p-tau, and α-synuclein. The ubiquitin proteasome pathway is responsible for removing abnormally folded proteins, preventing formation of protein aggregates. Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) is a multifunctional enzyme selectively expressed in neurons at high levels (Larsen et al., 1996). UCH-L1 plays a key role in the ubiquitin proteasome pathway (UPP) in neurons: it ligates ubiquitin to proteins prior to transport and hydrolyzes ubiquitin prior to these proteins entering the proteasome for degradation. UCH-L1 also plays an important role in repair of axons and neurons after injury by removal of abnormal proteins by the UPP (Bheda et al., 2010; Bilguvar et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2010). UCH-L1 closely interacts with proteins in the neuronal cytoskeleton, and may be an important component of the axonal transport system required to maintain axonal integrity (Genc et al., 2016). Mutation or disruption of UCH-L1 in mice leads to severe axonal pathology similar to neuritic plaques, and synaptic dysfunction (Castegna et al., 2004; Saigoh et al., 1999; Setsuie and Wada, 2007). UCH-L1 may also play an important role in Aβ deposition, as it ubiquinates β-secretase, tagging it for degradation (Zhang et al., 2012b). UCH-L1 null mice have higher levels of brain Aβ (Ichihara et al., 1995), while overexpression of UCH-L1 slows the deposition of Aβ and attenuates cognitive decline in a mouse model of AD (Zhang et al., 2012). The role of UCH-L1 in regulating synaptic function and long-term potentiation (Chen et al., 2010; Gong et al., 2006) is also important in the context of brain injury, since preservation of axonal integrity and synaptic function play a pivotal role in restoration of motor and cognitive function after TBI (Armstrong et al., 2016; Goldberg and Ransom, 2003). Thus, preservation of UCH-L1 function may be an effective strategy to maintain axonal and synaptic integrity and improve cognitive function after TBI. UCH-L1 function may be restored by transducing neurons with recombinant UCH-L1 protein constructs containing the prothrombin domain of the HIV TAT capsid protein (TAT-UCH-L1). TAT-UCH-L1 protects axons against damage produced by reactive lipids and protects neurons from cell death induced by hypoxia in vitro (Liu et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2015a). Systemically administered TAT UCH-L1 crosses the blood brain barrier and transduces neurons in vivo, and TAT-UCH-L1 fusion proteins can improve memory function in a mouse model of AD (Gong et al., 2006). After CCI in mice, intraperitoneal treatment with TAT-UCH-L1 decreased APP-immunoreactive damaged axons and had reduced hippocampal cell death and lesion volume (Liu et al., 2017). Similar approaches to enhance UCH-L1 function need to be explored in experimental models of both single moderate-severe TBI and rmTBI, particularly at chronic time points after injury. Given the rapid aggregation of molecules after TBI, successful strategies for their removal at later time points after TBI would obviate the need for immediate (acute) intervention targeting these pathological molecules.

4. Summary and conclusions

Development of multifunctional pharmaco-behavioral rehabilitative therapies to treat the consequences of TBI in the military, contact sport, and civilian arenas is of high priority given the high incidence of TBI and its connection, as a risk factor, with aging-related dementing disorders such as AD, movement disorders, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, and appearance of psychiatric symptoms of CTE and PTSD (Gardner et al., 2014). To break the link between TBI and dementia, targeting molecules central to chronic neurodegenerative disease (Aβ, p-tau, α-synuclein) is a desirable goal (Figure 1). Clinicopathological links of rmTBI to neurodegenerative disease are being revisited following rediscovery of high incidence of polypathology following rmTBI including bTBI and concussions in professional contact sport athletes (Goldstein et al., 2012; Mez et al., 2017; Stein et al., 2015; Tagge et al., 2018). It is unclear whether pathological protein aggregates cause, or result from, secondary injury processes in TBI. Better understanding of multiple pathological mechanisms involved in the chronic consequences of TBI, polypathology of different TBI forms, and improved preclinical models for each of these forms are required to address this question. The polypathology of CTE supports the need for therapies with a wide range of therapeutic mechanisms; targeting one aggregation prone molecule or pathway with monotherapeutic approach is unlikely to be effective.

The limitations of current animal models also need to be overcome. Chronic accumulation of pathological aggregated proteins is a unique future of human disease not observed in wild type animals, possibly due to difference between species’ life spans. The temporal course of aggregation of proteins implicated in human neurodegenerative disorders is on the order of years to decades (e.g. tau pathology in AD; (Morsch et al., 1999)), making it difficult to study these molecules in short-living animal models. Discrepancies regarding tau pathology in experimental wild type mice after TBI, as well as lack of neurofibrillary tangles despite presence of p-tau in human tau-expressing mice exposed to TBI, also create a roadblock to development of therapies to reduce emergent tau pathology in human TBI. As noted by Abisambra (Abisambra and Scheff, 2014), more studies of tau changes after experimental TBI are needed keeping in mind potential differences in response of tau to age-at-injury, injury severity, and anti-tau antibodies employed in immunohistochemical and biochemical assays. Similar to the challenges in developing a highly-specific tau-imaging PET ligands, the design of anti-tau therapies in chronic neurodegenerative disease needs to factor complexities of tau protein. There are six isoforms of tau identified in human brain (Goedert et al., 1989), with >20 specific mutations known. As in AD, tau deposits in CTE are comprised of a mixture of 3-repeat (3R) and 4-repeat (4R) tau isoforms, while other non-AD tauopathies are characterized mainly by 3R (Pick disease) or 4R (PSP and CBD) (Iqbal et al., 2016). Furthermore, the degree of tau phosphorylation varies significantly across and within disease states. A better understanding of aggregation-prone molecules in the context of brain injury is critical before novel strategies can be developed to overcome discussed limitations.

Despite these limitations, significant cortical and hippocampal atrophy observed chronically after TBI in rodent models closely mimics progressive structural changes reported in human TBI and indicates the need for novel therapies to promote cell and synapse regeneration during the chronic recovery period after TBI. There is a critical need for long-term, controlled (scientifically rigorous) experimental TBI studies in animals, to better understand the chronic clinical and neuropathological consequences of TBI and to identify promising avenues of therapy for improved chronic recovery after TBI (Bramlett and Dietrich, 2015; Gold et al., 2013; Osier et al., 2015). This is challenging as high price of long-term experimental studies and long wait for results of even a small-scale chronic survival TBI experiment compromise the practicality of these studies in current research funding frameworks.

5. Acknowledgment

We thank Lan Shao and William Paljug for expert technical assistance, and Dr. Ava Puccio for TBI tissue sample coordination. We are grateful to the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center and the Brain Trauma Research Center. Supported by VA RR&D grants 1I01RX000511, 101RX000952, and 1I01RX001778; NIH grants AG05133, NS30318, NS091062, and AG014449. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government.

7. References

- Abisambra JF, Scheff S, 2014. Brain injury in the context of tauopathies. J Alzheimers Dis 40, 495–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson EE, Foley LM, Dekosky ST, Hitchens TK, Ho C, Kochanek PM, Ikonomovic MD, 2013. Cerebral blood flow changes after brain injury in human amyloid-beta knock-in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33, 826–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson EE, Ikonomovic MD, Ciallella JR, Hope CE, Paljug WR, Isanski BA, Flood DG, Clark RSB, DeKosky ST, 2006. Caspase inhibition therapy abolishes brain trauma-induced increases in Abeta peptide: Implications for clinical outcome. Exp Neurol 197, 437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson EE, Ikonomovic MD, Dixon CE, DeKosky ST, 2009. Simvastatin therapy prevents brain trauma-induced increases in beta-amyloid peptide levels. Ann Neurol 66, 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta SA, Tajiri N, de la Pena I, Bastawrous M, Sanberg PR, Kaneko Y, Borlongan CV, 2015. Alpha-synuclein as a pathological link between chronic traumatic brain injury and Parkinson’s disease. J Cell Physiol 230, 1024–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alafuzoff I, Hartikainen P, 2017. Alpha-synucleinopathies. Handb Clin Neurol 145, 339–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albayram O, Kondo A, Mannix R, Smith C, Tsai CY, Li C, Herbert MK, Qiu J, Monuteaux M, Driver J, Yan S, Gormley W, Puccio AM, Okonkwo DO, Lucke-Wold B, Bailes J, Meehan W, Zeidel M, Lu KP, Zhou XZ, 2017. Cis P-tau is induced in clinical and preclinical brain injury and contributes to post-injury sequelae. Nat Commun 8, 1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambree O, Leimer U, Herring A, Gortz N, Sachser N, Heneka MT, Paulus W, Keyvani K, 2006. Reduction of amyloid angiopathy and Abeta plaque burden after enriched housing in TgCRND8 mice: involvement of multiple pathways. Am J Pathol 169, 544–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong RC, Mierzwa AJ, Marion CM, Sullivan GM, 2016. White matter involvement after TBI: Clues to axon and myelin repair capacity. Exp Neurol 275 Pt 3, 328–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales JW, Wagner AK, Kline AE, Dixon CE, 2009. Persistent cognitive dysfunction after traumatic brain injury: A dopamine hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33, 981–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barao S, Moechars D, Lichtenthaler SF, De Strooper B, 2016. BACE1 Physiological Functions May Limit Its Use as Therapeutic Target for Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends Neurosci 39, 158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DE, Kaup A, Kirby KA, Byers AL, Diaz-Arrastia R, Yaffe K, 2014. Traumatic brain injury and risk of dementia in older veterans. Neurology 83, 312–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum G, Yan HQ, Li L, Singh A, Dixon CE, Sun D, 2014. Docosahexaenoic acid reduces ER stress and abnormal protein accumulation and improves neuronal function following traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci 34, 3743–3755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardi N, Braschi C, Capsoni S, Cattaneo A, Maffei L, 2007. Environmental enrichment delays the onset of memory deficits and reduces neuropathological hallmarks in a mouse model of Alzheimer-like neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis 11, 359–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betzer C, Movius AJ, Shi M, Gai WP, Zhang J, Jensen PH, 2015. Identification of synaptosomal proteins binding to monomeric and oligomeric alpha-synuclein. PLoS One 10, e0116473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bheda A, Gullapalli A, Caplow M, Pagano JS, Shackelford J, 2010. Ubiquitin editing enzyme UCH L1 and microtubule dynamics: implication in mitosis. Cell Cycle 9, 980–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilguvar K, Tyagi NK, Ozkara C, Tuysuz B, Bakircioglu M, Choi M, Delil S, Caglayan AO, Baranoski JF, Erturk O, Yalcinkaya C, Karacorlu M, Dincer A, Johnson MH, Mane S, Chandra SS, Louvi A, Boggon TJ, Lifton RP, Horwich AL, Gunel M, 2013. Recessive loss of function of the neuronal ubiquitin hydrolase UCHL1 leads to early-onset progressive neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 3489–3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird SM, Sohrabi HR, Sutton TA, Weinborn M, Rainey-Smith SR, Brown B, Patterson L, Taddei K, Gupta V, Carruthers M, Lenzo N, Knuckey N, Bucks RS, Verdile G, Martins RN, 2016. Cerebral amyloid-beta accumulation and deposition following traumatic brain injury--A narrative review and meta-analysis of animal studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 64, 215–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasko I, Beer R, Bigl M, Apelt J, Franz G, Rudzki D, Ransmayr G, Kampfl A, Schliebs R, 2004. Experimental traumatic brain injury in rats stimulates the expression, production and activity of Alzheimer’s disease beta-secretase (BACE-1). J Neural Transm (Vienna) 111, 523–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi CO, Klitsch KC, Leary JB, Kline AE, 2014. Environmental enrichment as a viable neurorehabilitation strategy for experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 31, 873–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E, 1991. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82, 239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braczynski AK, Schulz JB, Bach JP, 2017. Vaccination strategies in tauopathies and synucleinopathies. J Neurochem 143, 467–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD, 2015. Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury: Current Status of Potential Mechanisms of Injury and Neurological Outcomes. J Neurotrauma 32, 1834–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunden KR, Zhang B, Carroll J, Yao Y, Potuzak JS, Hogan AM, Iba M, James MJ, Xie SX, Ballatore C, Smith AB 3rd, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, 2010. Epothilone D improves microtubule density, axonal integrity, and cognition in a transgenic mouse model of tauopathy. J Neurosci 30, 13861–13866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Harvey AG, 1999. Postconcussive symptoms and posttraumatic stress disorder after mild traumatic brain injury. J Nerv Ment Dis 187, 302–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burre J, Sharma M, Tsetsenis T, Buchman V, Etherton MR, Sudhof TC, 2010. Alpha-synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science 329, 1663–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Wang Y, McCarthy D, Wen H, Borchelt DR, Price DL, Wong PC, 2001. BACE1 is the major beta-secretase for generation of Abeta peptides by neurons. Nat Neurosci 4, 233–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SW, Henchir J, Dixon CE, 2017a. Lateral Fluid Percussion Injury Impairs Hippocampal Synaptic Soluble N-Ethylmaleimide Sensitive Factor Attachment Protein Receptor Complex Formation. Front Neurol 8, 532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SW, Yan H, Dixon CE, 2017b. Lithium increases hippocampal SNARE protein abundance after traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 289, 55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney N, Totten AM, O’Reilly C, Ullman JS, Hawryluk GW, Bell MJ, Bratton SL, Chesnut R, Harris OA, Kissoon N, Rubiano AM, Shutter L, Tasker RC, Vavilala MS, Wilberger J, Wright DW, Ghajar J, 2017. Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Fourth Edition. Neurosurgery 80, 6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr W, Yarnell AM, Ong R, Walilko T, Kamimori GH, da Silva U, McCarron RM, LoPresti ML, 2015. Ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase-l1 as a serum neurotrauma biomarker for exposure to occupational low-level blast. Front Neurol 6, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castegna A, Thongboonkerd V, Klein J, Lynn BC, Wang YL, Osaka H, Wada K, Butterfield DA, 2004. Proteomic analysis of brain proteins in the gracile axonal dystrophy (gad) mouse, a syndrome that emanates from dysfunctional ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L-1, reveals oxidation of key proteins. J Neurochem 88, 1540–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernak I, 2015. Blast Injuries and Blast-Induced Neurotrauma: Overview of Pathophysiology and Experimental Knowledge Models and Findings In: Kobeissy FH, (Ed), Brain Neurotrauma: Molecular, Neuropsychological, and Rehabilitation Aspects, Boca Raton (FL). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernak I, Noble-Haeusslein LJ, 2010. Traumatic brain injury: an overview of pathobiology with emphasis on military populations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30, 255–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernak I, Stein DG, Elder GA, Ahlers S, Curley K, DePalma RG, Duda J, Ikonomovic M, Iverson GL, Kobeissy F, Koliatsos VE, Leggieri MJ Jr., Pacifico AM, Smith DH, Swanson R, Thompson FJ, Tortella FC, 2017. Preclinical modelling of militarily relevant traumatic brain injuries: Challenges and recommendations for future directions. Brain Inj 31, 1168–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Gallardo G, Fernandez-Chacon R, Schluter OM, Sudhof TC, 2005. Alpha-synuclein cooperates with CSPalpha in preventing neurodegeneration. Cell 123, 383–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan NB, Gatto R, 2010. Synergistic benefits of erythropoietin and simvastatin after traumatic brain injury. Brain Res 1360, 177–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Sugiura Y, Myers KG, Liu Y, Lin W, 2010. Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 is required for maintaining the structure and function of the neuromuscular junction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 1636–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XH, Johnson VE, Uryu K, Trojanowski JQ, Smith DH, 2009. A lack of amyloid beta plaques despite persistent accumulation of amyloid beta in axons of long-term survivors of traumatic brain injury. Brain Pathol 19, 214–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XH, Siman R, Iwata A, Meaney DF, Trojanowski JQ, Smith DH, 2004. Long-term accumulation of amyloid-beta, beta-secretase, presenilin-1, and caspase-3 in damaged axons following brain trauma. Am J Pathol 165, 357–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XR, Besson VC, Beziaud T, Plotkine M, Marchand-Leroux C, 2008. Combination therapy with fenofibrate, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha agonist, and simvastatin, a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitor, on experimental traumatic brain injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 326, 966–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Huang EY, Kuo TT, Ma HI, Hoffer BJ, Tsui PF, Tsai JJ, Chou YC, Chiang YH, 2015. Dopamine Release Impairment in Striatum After Different Levels of Cerebral Cortical Fluid Percussion Injury. Cell Transplant 24, 2113–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SX, Zhang S, Sun HT, Tu Y, 2013. Effects of Mild Hypothermia Treatment on Rat Hippocampal beta-Amyloid Expression Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag 3, 132–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BK, Choi MG, Kim JY, Yang Y, Lai Y, Kweon DH, Lee NK, Shin YK, 2013. Large alpha-synuclein oligomers inhibit neuronal SNARE-mediated vesicle docking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 4087–4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciallella JR, Ikonomovic MD, Paljug WR, Wilbur YI, Dixon CE, Kochanek PM, Marion DW, DeKosky ST, 2002. Changes in expression of amyloid precursor protein and interleukin-1beta after experimental traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 19, 1555–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AD, Ikonomovic MD, Abrahamson EE, Paljug WR, Dekosky ST, Lefterov IM, Koldamova RP, Shao L, Debnath ML, Mason NS, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, 2009. Anti-Amyloid Effects of Small Molecule Abeta-Binding Agents in PS1/APP Mice. Lett Drug Des Discov 6, 437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkin S, Rosen TJ, Sullivan EV, Clegg RA, 1989. Penetrating head injury in young adulthood exacerbates cognitive decline in later years. J Neurosci 9, 3876–3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan F, Vink R, Blumbergs PC, Masters CL, Cappai R, van den Heuvel C, 2012a. Characterisation of the effect of knockout of the amyloid precursor protein on outcome following mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Res 1451, 87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan F, Vink R, Blumbergs PC, Masters CL, Cappai R, van den Heuvel C, 2012b. Evaluation of the effects of treatment with sAPPalpha on functional and histological outcome following controlled cortical impact injury in mice. Neurosci Lett 515, 50–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan F, Vink R, Blumbergs PC, Masters CL, Cappai R, van den Heuvel C, 2012c. sAPPalpha rescues deficits in amyloid precursor protein knockout mice following focal traumatic brain injury. J Neurochem 122, 208–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsellis JA, Bruton CJ, Freeman-Browne D, 1973. The aftermath of boxing. Psychol Med 3, 270–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa DA, Cracchiolo JR, Bachstetter AD, Hughes TF, Bales KR, Paul SM, Mervis RF, Arendash GW, Potter H, 2007. Enrichment improves cognition in AD mice by amyloid-related and unrelated mechanisms. Neurobiol Aging 28, 831–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cracchiolo JR, Mori T, Nazian SJ, Tan J, Potter H, Arendash GW, 2007. Enhanced cognitive activity--over and above social or physical activity--is required to protect Alzheimer’s mice against cognitive impairment, reduce Abeta deposition, and increase synaptic immunoreactivity. Neurobiol Learn Mem 88, 277–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Dams-O’Connor K, Trittschuh E, Leverenz JB, Keene CD, Sonnen J, Montine TJ, Bennett DA, Leurgans S, Schneider JA, Larson EB, 2016. Association of Traumatic Brain Injury With Late-Life Neurodegenerative Conditions and Neuropathologic Findings. JAMA Neurol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribbs DH, Chen LS, Cotman CW, LaFerla FM, 1996. Injury induces presenilin-1 gene expression in mouse brain. Neuroreport 7, 1773–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofori I, Levin HS, 2015. Traumatic brain injury and cognition. Handb Clin Neurol 128, 579–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai CL, Hu W, Tung YC, Liu F, Gong CX, Iqbal K, 2018. Tau passive immunization blocks seeding and spread of Alzheimer hyperphosphorylated Tau-induced pathology in 3 x Tg-AD mice. Alzheimers Res Ther 10, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish H, Mahmood A, Schallert T, Chopp M, Therrien B, 2014. Simvastatin and environmental enrichment effect on recognition and temporal order memory after mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 28, 211–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson HN, Cantillana V, Jansen M, Wang H, Vitek MP, Wilcock DM, Lynch JR, Laskowitz DT, 2010. Loss of tau elicits axonal degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 169, 516–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gasperi R, Gama Sosa MA, Kim SH, Steele JW, Shaughness MC, Maudlin-Jeronimo E, Hall AA, Dekosky ST, McCarron RM, Nambiar MP, Gandy S, Ahlers ST, Elder GA, 2012. Acute blast injury reduces brain abeta in two rodent species. Front Neurol 3, 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKosky ST, Abrahamson EE, Ciallella JR, Paljug WR, Wisniewski SR, Clark RS, Ikonomovic MD, 2007. Association of increased cortical soluble abeta42 levels with diffuse plaques after severe brain injury in humans. Arch Neurol 64, 541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Turco D, Schlaudraff J, Bonin M, Deller T, 2014. Upregulation of APP, ADAM10 and ADAM17 in the denervated mouse dentate gyrus. PLoS One 9, e84962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePalma RG, 2015. Combat TBI: History, Epidemiology, and Injury Modes() In: Kobeissy FH, (Ed), Brain Neurotrauma: Molecular, Neuropsychological, and Rehabilitation Aspects, Boca Raton (FL). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon CE, Kochanek PM, Yan HQ, Schiding JK, Griffith RG, Baum E, Marion DW, DeKosky ST, 1999. One-year study of spatial memory performance, brain morphology, and cholinergic markers after moderate controlled cortical impact in rats. J Neurotrauma 16, 109–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockree PM, Kelly SP, Roche RA, Hogan MJ, Reilly RB, Robertson IH, 2004. Behavioural and physiological impairments of sustained attention after traumatic brain injury. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 20, 403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X, West MB, Cheng W, Ewert DL, Li W, Saunders D, Towner RA, Floyd RA, Kopke RD, 2016. Ameliorative Effects of Antioxidants on the Hippocampal Accumulation of Pathologic Tau in a Rat Model of Blast-Induced Traumatic Brain Injury. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 4159357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlow BL, Keene CD, Perl D, Iacono D, Folkerth R, Stewart W, MacDonald CL, Augustinack J, Diaz-Arrastia R, Estrada C, Flannery E, Gordon W, Grabowski T, Hansen K, Hoffman J, Kroenke C, Larson E, Lee P, Mareyam A, McNab JA, McPhee J, Moreau AL, Renz A, Richmire K, Stevens A, Tang CY, Tirrell LS, Trittschuh E, van der Kouwe A, Varjabedian A, Wald LL, Wu O, Yendiki A, Young L, Zollei L, Fischl B, Crane PK, Dams-O’Connor K, 2018. Multimodal Characterization of the Late Effects of TBI (LETBI): A Methodological Overview of the LETBI Project. J Neurotrauma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RC, Burke JF, Nettiksimmons J, Kaup A, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, 2014. Dementia risk after traumatic brain injury vs nonbrain trauma: the role of age and severity. JAMA Neurol 71, 1490–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes JF, Vowles GH, Nicoll JA, Revesz T, 1999. Neuronal cytoskeletal changes are an early consequence of repetitive head injury. Acta Neuropathol 98, 171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes JF, Vowles GH, Robinson SF, Sutcliffe JC, 1996. Neurofibrillary tangles, but not Alzheimer-type pathology, in a young boxer. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 22, 12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genc B, Jara JH, Schultz MC, Manuel M, Stanford MJ, Gautam M, Klessner JL, Sekerkova G, Heller DB, Cox GA, Heckman CJ, DiDonato CJ, Ozdinler PH, 2016. Absence of UCHL 1 function leads to selective motor neuropathy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 3, 331–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman SM, Nash MJ, Sweeting CJ, Graham DI, Roberts GW, 1993. Beta-amyloid precursor protein (beta APP) as a marker for axonal injury after head injury. Neurosci Lett 160, 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerson J, Castillo-Carranza DL, Sengupta U, Bodani R, Prough DS, DeWitt DS, Hawkins BE, Kayed R, 2016. Tau Oligomers Derived from Traumatic Brain Injury Cause Cognitive Impairment and Accelerate Onset of Pathology in Htau Mice. J Neurotrauma 33, 2034–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA, 1989. Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 3, 519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]