Abstract

Background

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding due to stress ulcers contributes to increased morbidity and mortality in people admitted to intensive care units (ICUs). Stress ulceration refers to GI mucosal injury related to the stress of being critically ill. ICU patients with major bleeding as a result of stress ulceration might have mortality rates approaching 48.5% to 65%. However, the incidence of stress‐induced GI bleeding in ICUs has decreased, and not all critically ill patients need prophylaxis. Stress ulcer prophylaxis can result in adverse events such as ventilator‐associated pneumonia; therefore, it is necessary to evaluate strategies that safely decrease the incidence of GI bleeding.

Objectives

To assess the effect and risk‐benefit profile of interventions for preventing upper GI bleeding in people admitted to ICUs.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to 23 August 2017, using relevant search terms: MEDLINE; Embase; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; Latin American Caribbean Health Sciences Literature; and the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Disease Group Specialised Register, as published in the Cochrane Library (2017, Issue 8). We searched the reference lists of all included studies and those from relevant systematic reviews and meta‐analyses to identify additional studies. We also searched the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform search portal and contacted individual researchers working in this field, as well as organisations and pharmaceutical companies, to identify unpublished and ongoing studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs with participants of any age and gender admitted to ICUs for longer than 48 hours. We excluded studies in which participants were admitted to ICUs primarily for the management of GI bleeding and studies that compared different doses, routes, and regimens of one drug in the same class because we were not interested in intraclass effects of drugs.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures as recommended by Cochrane.

Main results

We identified 2292 unique records.We included 129 records reporting on 121 studies, including 12 ongoing studies and two studies awaiting classification.

We judged the overall risk of bias of two studies as low. Selection bias was the most relevant risk of bias domain across the included studies, with 78 studies not clearly reporting the method used for random sequence generation. Reporting bias was the domain with least risk of bias, with 12 studies not reporting all outcomes that researchers intended to investigate.

Any intervention versus placebo or no prophylaxis

In comparison with placebo, any intervention seems to have a beneficial effect on the occurrence of upper GI bleeding (risk ratio (RR) 0.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.39 to 0.57; moderate certainty of evidence). The use of any intervention reduced the risk of upper GI bleeding by 10% (95% CI ‐12.0% to ‐7%). The effect estimate of any intervention versus placebo or no prophylaxis with respect to the occurrence of nosocomial pneumonia, all‐cause mortality in the ICU, duration of ICU stay, duration of intubation (all with low certainty of evidence), the number of participants requiring blood transfusions (moderate certainty of evidence), and the units of blood transfused was consistent with benefits and harms. None of the included studies explicitly reported on serious adverse events.

Individual interventions versus placebo or no prophylaxis

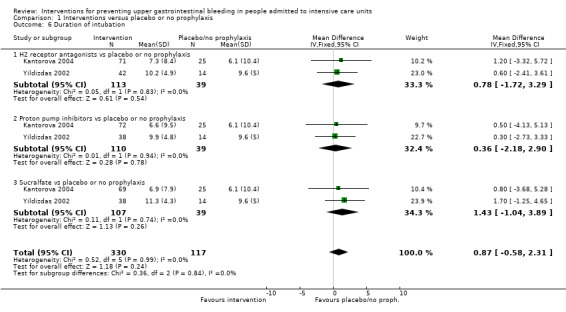

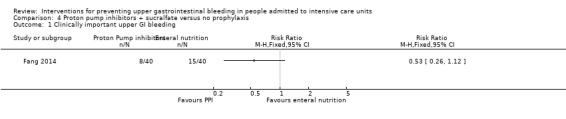

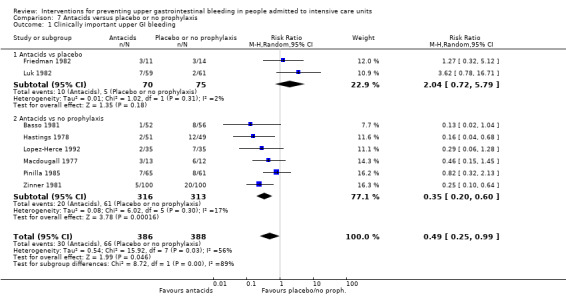

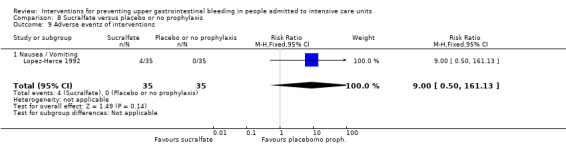

In comparison with placebo or no prophylaxis, antacids, H2 receptor antagonists, and sucralfate were effective in preventing upper GI bleeding in ICU patients. Researchers found that with H2 receptor antagonists compared with placebo or no prophylaxis, 11% less developed upper GI bleeding (95% CI ‐0.16 to ‐0.06; RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.70; 24 studies; 2149 participants; moderate certainty of evidence). Of ICU patients taking antacids versus placebo or no prophylaxis, 9% less developed upper GI bleeding (95% CI ‐0.17 to ‐0.00; RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.99; eight studies; 774 participants; low certainty of evidence). Among ICU patients taking sucralfate versus placebo or no prophylaxis, 5% less had upper GI bleeding (95% CI ‐0.10 to ‐0.01; RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.88; seven studies; 598 participants; moderate certainty of evidence). The remaining interventions including proton pump inhibitors did not show a significant effect in preventing upper GI bleeding in ICU patients when compared with placebo or no prophylaxis.

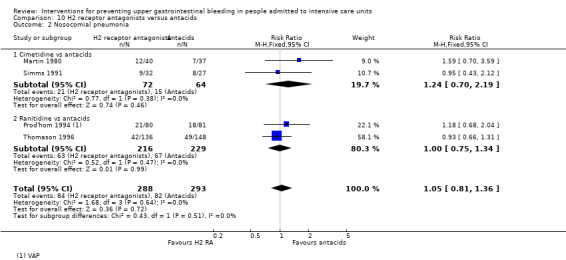

Regarding the occurrence of nosocomial pneumonia, the effects of H2 receptor antagonists (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.48; eight studies; 945 participants; low certainty of evidence) and of sucralfate (RR 1.33, 95% CI 0.86 to 2.04; four studies; 450 participants; low certainty of evidence) were consistent with benefits and harms when compared with placebo or no prophylaxis. None of the studies comparing antacids versus placebo or no prophylaxis provided data regarding nosocomial pneumonia.

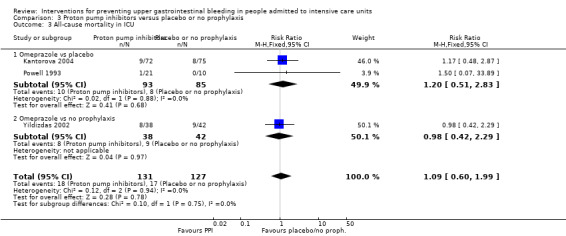

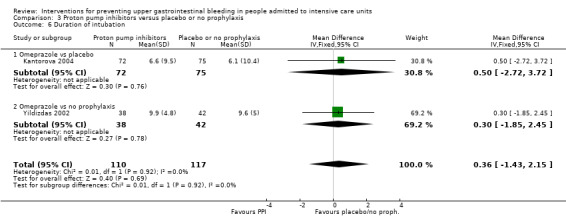

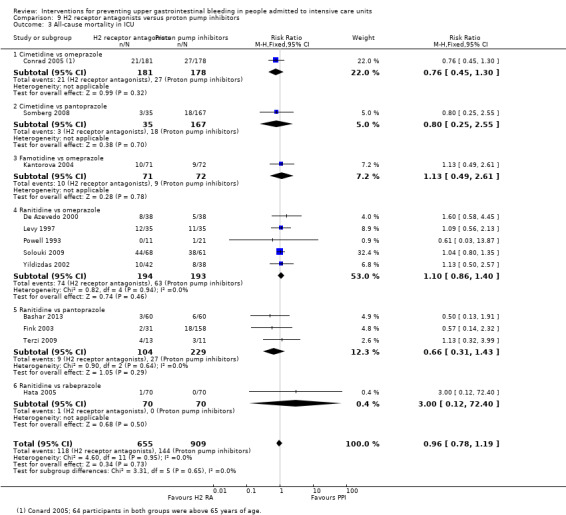

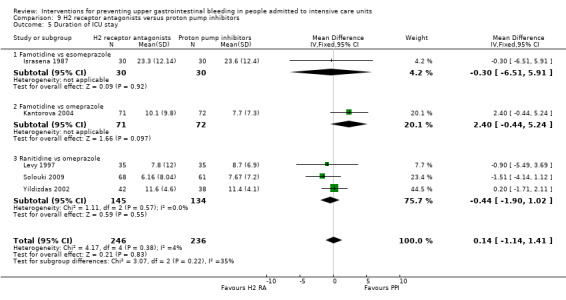

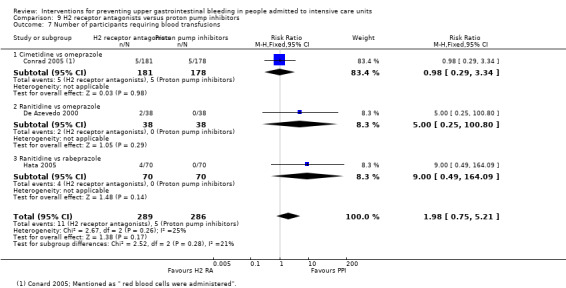

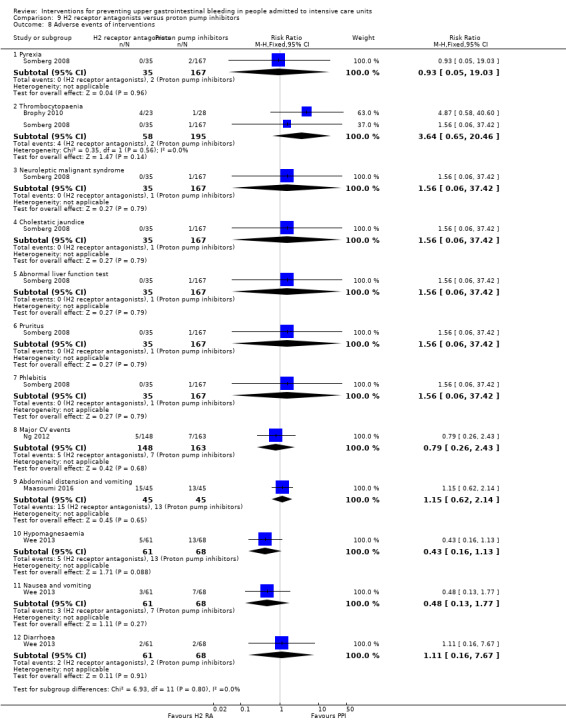

H2 receptor antagonists versus proton pump inhibitors

H2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors are most commonly used in practice to prevent upper GI bleeding in ICU patients. Proton pump inhibitors significantly more often prevented upper GI bleeding in ICU patients compared with H2 receptor antagonists (RR 2.90, 95% CI 1.83 to 4.58; 18 studies; 1636 participants; low certainty of evidence). When taking H2 receptor antagonists, 4.8% more patients might experience upper GI bleeding (95% CI 2.1% to 9%). Nosocomial pneumonia occurred in similar proportions of participants taking H2 receptor antagonists and participants taking proton pump inhibitors (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.35; 10 studies; 1256 participants; low certainty of evidence).

Authors' conclusions

This review shows that antacids, sucralfate, and H2 receptor antagonists might be more effective in preventing upper GI bleeding in ICU patients compared with placebo or no prophylaxis. The effect estimates of any treatment versus no prophylaxis on nosocomial pneumonia were consistent with benefits and harms. Evidence of low certainty suggests that proton pump inhibitors might be more effective than H2 receptor antagonists. Therefore, patient‐relevant benefits and especially harms of H2 receptor antagonists compared with proton pump inhibitors need to be assessed by larger, high‐quality RCTs to confirm the results of previously conducted, smaller, and older studies.

Plain language summary

Interventions for preventing upper gastrointestinal bleeding in people on intensive care units

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about benefits and harms of interventions to prevent clinically important upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Background

Stress ulcers are seen as superficial damage in the mucous lining of the stomach or intestines that can occur as the result of shock, sepsis, or trauma. Depending on the severity of the damage, afflicted areas may become sore and may start to bleed to varying degrees. Upper GI bleeding due to stress ulcers is a major contributor to increased severity of illness and death among people admitted to ICUs. However, standards of care have improved, and the incidence of upper GI bleeding in ICUs has decreased. Thus, not all critically ill patients need preventive treatment.

Stress ulcer prophylaxis can result in negative effects such as ventilator‐associated pneumonia (VAP). VAP is a lung infection caused by bacteria in people who are being mechanically ventilated. VAP usually manifests as fever, cough, and purulent sputum. The risk for VAP is increased in patients with severe illness, increased length of hospital stay, or use of stress ulcer prophylaxis. Hence, it is necessary to evaluate strategies that safely decrease the incidence of upper GI bleeding.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to August 2017. We included 106 studies with a total of 15,027 critically ill participants of any age and any gender.

Key results

Relevant effects were found for the following drugs: H2 receptor antagonists, antacids, sucralfate, and proton pump inhibitors.

H2 receptor antagonists inhibit gastric acid secretion by blocking histamine receptors but can cause a small number of blood platelets (thrombocytopaenia), inflammation of the kidney (interstitial nephritis), and confusion. Antacids neutralise stomach acid but may cause diarrhoea or constipation. Proton pump inhibitors inhibit the final stage of gastric acid production, and it has been found that they may be associated with increased risk of Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Ulcer protective agents, such as sucralfate, create a barrier between the gastric acid and the gastric mucosa by coating it. They may, however, cause constipation and interfere with the absorption of certain antibacterial agents.

In comparison with placebo or no preventive treatment, H2 receptor antagonists, antacids, and sucralfate might be effective in preventing clinically important upper GI bleeding in ICU patients. Hospital‐acquired pneumonia was most likely to occur in ICU patients taking either H2 receptor antagonists or sucralfate when compared with patients given placebo or no preventive treatment.

Evidence of low certainty suggests that proton pump inhibitors were more effective than H2 receptor antagonists in preventing upper GI bleeding in ICU patients. With proton pump inhibitors, 25 of 1000 people were likely to develop upper GI bleeding, and with H2 receptor antagonists, 73 of 1000 people (95% confidence interval 46 to 115 people) were likely to develop upper GI bleeding. The effect of H2 receptor antagonists versus proton pump inhibitors with respect to the risk for developing hospital‐acquired pneumonia was consistent with benefits and harms.

Quality of the evidence

Our certainty in the evidence ranged from low to moderate. For effects of different interventions compared with placebo or no prophylaxis, the certainty of evidence was moderate (H2 receptor antagonists) or low (antacids and sucralfate). For effects of H2 receptor antagonists compared with placebo or no preventive treatment on risk of hospital‐acquired pneumonia, the certainty of evidence was low. For effects of H2 receptor antagonists compared with proton pump inhibitors on hospital‐acquired pneumonia, the certainty of evidence was also low.

Summary of findings

Background

A glossary of the medical terms used in this review can be found in Appendix 1.

Description of the condition

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding due to stress ulcers is a major contributor to increased morbidity and mortality in people admitted to intensive care units (ICUs). Stress ulceration refers to GI mucosal injury related to the stress of being critically ill. The injury may vary from diffuse superficial ulcers to deep, bleeding lesions (Neligan 2006). The incidence of bleeding related to stress ulcers in critically ill people on mechanical ventilators ranges from less than 1% to 6% of patients admitted to ICU (Alhazzani 2013; Bardou 2015; Krag 2015). A study using the HEmorrhage MEasurement Tool (HEME) to assess GI bleeding in ICU patients observed that 5.2% of those with stress ulcers had major bleeds (Arnold 2007). ICU patients with major bleeding as a result of stress ulceration had mortality rates approaching 40% to 50% (Bardou 2015). Over the past few decades, however, with improved standards of care, the incidence of stress‐induced GI bleeding in ICUs and related mortality has decreased (Krag 2015). Hence, not all critically ill patients need prophylaxis (Penner 2005). Gastric bleeding can be diagnosed from a drop in blood pressure necessitating blood transfusion and a rapid heart rate (haemodynamic instability), 'coffee ground' aspiration, vomiting of blood (haematemesis), or passage of dark stools (melena) (Dorland 1995).

Bleeding from stress ulcers

Bleeding from stress ulcers may be trivial or profuse. Trivial bleeds may be detected only through laboratory tests, and profuse bleeding results in overt manifestations. Cook 1998a defined a clinically important bleed as overt bleeding with one of four features reflecting haemodynamic instability and blood loss. These include the following.

Drop in systolic or diastolic blood pressure (blood pressure during heart contractions or between two heartbeats) of 20 mmHg or more within 24 hours after upper GI bleeding.

Postural decrease in systolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg and accelerated pulse rate of 20 beats per minute; or evidence of significant blood loss (this may be difficult to demonstrate in intubated patients).

A drop in haemoglobin concentration of at least 2 g/dL needing two units of packed cell transfusion within 24 hours of the bleed.

Failure of a rise in haemoglobin concentration (in g/dL) of at least the number of units of blood transfused minus two.

Risk factors

Prophylaxis is often recommended for patients with major risk factors. These include:

patients who have a coagulopathy (a disorder of blood clotting); and

patients who require mechanical ventilation for longer than 48 hours.

In addition, prophylaxis is often recommended for patients who have two or more of the following risk factors for stress ulcers (AHSP 1999; Pfeffer 2007).

ICU stay longer than one week.

Sepsis or abnormally low blood pressure (hypotension).

Failure of the liver or kidneys.

History of peptic ulcer disease.

Use of high‐dose steroids (> 250 mg/d of hydrocortisone or equivalent).

Burns over > 35% of total body surface area.

Immediately after organ transplantation.

Head trauma with Glasgow Coma Scale score < 10.

Multiple trauma.

Occult bleeding for six days or longer.

Pathophysiology of stress ulcers

The aetiology ‐ cause or set of causes for a disease ‐ and pathophysiology of stress ulcers in ICU patients appear to be multi‐factorial. Normally, the splanchnic microcirculation and the gastric mucosa protect the mucosal epithelium ‐ the tissue lining the outer surface of organs ‐ from gastric acids, wherein bicarbonate ions secreted by the mucosa neutralise hydrogen ions. Reduced blood flow due to splanchnic hypoperfusion in critically ill patients, with resultant ischaemia and impaired cell oxygenation, releases nitric oxide (by increased levels of enzyme nitric oxide synthase) and oxygen free radicals and reduces prostaglandin synthesis. These mechanisms result in inflammation and cell death. Reperfusion hyperaemia due to elevated nitric oxide levels contributes to further cell death. Slowed upper gastric mobility and reduced secretion of bicarbonate by the gastric mucosa with resultant prolonged exposure of the damaged mucosa to gastric acids, as well as a decrease in mucosal repair mechanisms, also contribute to ulceration (Dorland 1995; Spirt 2006).

Consequences of upper GI bleeding

Major GI bleeding can be life‐threatening and can result in death. Minor bleeding can result in an increased need for blood transfusion and its attendant risks. It is therefore necessary to evaluate strategies that decrease the incidence of GI bleeding.

Complications of stress ulcer prophylaxis: ventilator‐associated pneumonia

Ventilator‐associated pneumonia is a common complication in mechanically ventilated patients. The reported incidence of ventilator‐associated pneumonia ranges from 1% to 28% (Chastre 2002; Rahbar 2006). A systematic review of observational studies and randomised studies revealed that the incidence of ventilator‐associated pneumonia ranged from 10% to 20% in people undergoing mechanical ventilation for longer than 48 hours (Safdar 2005).

Risk factors for ventilator‐associated pneumonia

The risk of ventilator‐associated pneumonia increases with the duration of mechanical ventilation continuing over 48 hours, but the risk is additionally elevated in people with contributory medical conditions. Additional sources of infection from tubes passing the trachea (endotracheal) or ventilator circuits and other feeding tubes, or from improper measures to prevent nosocomial infection in ICU staff, increase the risk of ventilator‐associated pneumonia (Augustyn 2007; CDC 2003; Masterton 2008).

The disadvantage of stress ulcer prophylaxis is that many of the interventions used for suppression of gastric acid raise the pH of gastric contents, alter gastric flora, and promote tracheobronchial colonisation and gastric colonisation of pathogenic bacteria ‐ the aspiration of which causes nosocomial pneumonia or ventilator‐associated pneumonia (Atherton 1978; Cook 1998b; Craven 1986). In addition to increasing mortality in critically ill patients, the afore mentioned effects can prolong length of hospital stay and increase costs (Safdar 2005). The elevated risk of developing ventilator‐associated pneumonia associated with stress ulcer prophylaxis may therefore offset the potential benefits of such therapy.

Diagnosis of ventilator‐associated pneumonia

The criteria used to establish the diagnosis of ventilator‐associated pneumonia vary. Traditionally, clinical features (fever, cough, and purulent sputum) combined with radiological evidence for pneumonia (new lung infiltrates or progression of infiltrates) and elevated white blood cell count in a patient on mechanical ventilation provide suggestive evidence. Confirmatory cultures from sputum or aspirates from the trachea or pleural fluid in such individuals increase the sensitivity of the diagnosis of bacterial causes of pneumonia. However, these traditional methods are not specific in ventilator‐associated pneumonia, and blood cultures are reported to have low sensitivity. Standardised techniques used in clinical research studies have included quantitative culture of specimens obtained from endotracheal aspirates and use of protected specimen brush (PSB) specimens after bronchoalveolar lavage ‐ a medical procedure to examine the lungs for lung disease ‐ or via blind catheterisation (non‐bronchoscopic protected bronchoalveolar lavage or protected specimen brush specimens). These techniques have improved the sensitivity and specificity of the diagnosis of ventilator‐associated pneumonia (CDC 2003; Masterton 2008).

Criteria commonly used to diagnose ventilator‐associated pneumonia include the clinical pulmonary infection score (CPIS), which has evolved from the original four criteria (fever, leucocytosis, positive sputum culture, and worsening chest X‐ray changes) to six criteria (plus increased oxygen requirement and semi‐quantitative cultures of tracheal aspirates with or without Gram stain). Criteria added to the CPIS help practitioners in selecting, modifying, and monitoring therapy, although their diagnostic accuracy is similar to that of traditional criteria (Masterton 2008).

Mortality from ventilator‐associated pneumonia

Individuals who contract ventilator‐associated pneumonia are already critically ill; therefore the death rate from ventilator‐associated pneumonia is high. Reported mortality rates range from 24% to 76%, with higher mortality attributed to specific situations (such as underlying disease and organ failure) or types of causative organisms (such as Pseudomonas or Acinetobacter) (CDC 2003; Chastre 2002). Mortality is doubled in critically ill patients with ventilator‐associated pneumonia when compared with those without ventilator‐associated pneumonia (Safdar 2005).

It is considered prognostically important to distinguish early‐onset from late‐onset ventilator‐associated pneumonia. The Working Party on Hospital Acquired Pneumonia of the British Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy defined the former as occurring during the first four days, and the latter as occurring five or more days after the start of mechanical ventilation. Early‐onset ventilator‐associated pneumonia is usually less severe and carries a better prognosis than late‐onset ventilator‐associated pneumonia (Chastre 2002; Masterton 2008).

Description of the intervention

Several pharmacological interventions are used for treatment and prevention of gastric ulcers, such as those that block histamine‐2 receptors (H2 receptor antagonists) (ranitidine, cimetidine, famotidine, etc.), proton pump inhibitors (esomeprazole, rabeprazole, omeprazole, lansoprazole, etc.), prostaglandin analogues (misoprostol), anticholinergics (pirenzepine, propantheline, etc.), antacids (sodium bicarbonate, magnesium hydroxide, etc.), and ulcer protectives (sucralfate, bismuth, etc.). Non‐pharmacological interventions such as enteral nutrition and early removal of tubes can also be used.

How the intervention might work

The interventions used in stress ulcer prophylaxis differ with respect to their mechanism of action, additional protective effects on the gastric mucosa, and effects on increasing gastric luminal pH and resultant potential to increase gastric bacterial colonisation, as well as their side effect profile (Mutlu 2001).

Antacids neutralise gastric acid in a dose‐dependent manner and raise the gastric pH. They have other beneficial cytoprotective effects but may cause an increase in magnesium and diarrhoea (magnesium‐based antacids) or may reduce phosphates and cause constipation (aluminium‐based antacids). Nursing costs are also increased owing to the need to administer antacids at frequent intervals (often hourly).

H2 receptor antagonists are believed to inhibit gastric acid secretion by blocking histamine receptors but have no additional cytoprotective effects and can cause thrombocytopaenia, interstitial nephritis, and confusion (especially in the elderly). Rapid intravenous infusions can cause bradycardia ‐ a slow heart rate ‐ and abnormally low blood pressure (hypotension), and many cytochrome P‐450‐mediated drug interactions and effects may occur (particularly with cimetidine).

Proton pump inhibitors act by inhibiting the final stage of gastric acid production but provide no additional cytoprotective effects on the gastric mucosa and do confer cytochrome P‐450‐mediated effects. However, it has been found that proton pump inhibitors may be associated with increased risk of Clostridium difficile diarrhoea (Arriola 2016; Cunningham 2003; Kwok 2012; Mutlu 2001). Yet, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have reported very few data on this adverse event (Alhazzani 2017).

Prostaglandin analogues inhibit acid secretion and promote mucus and bicarbonate secretion that makes gastric contents alkaline, meaning that the pH is greater than 7, but they can cause diarrhoea and abdominal pain. However, they need to be administered four times daily.

Ulcer protective agents, such as sucralfate and colloidal bismuth subcitrate, create a barrier between gastric acid and the gastric mucosa by coating the mucosa. These agents have additional cytoprotective effects and do not effectively alter gastric pH, but they may cause constipation and may interfere with the absorption of certain antibacterial agents, such as tetracyclines and quinolones (Mutlu 2001).

Enteral nutrition may be delivered orally or through a feeding tube and helps to maintain gut integrity, modulate stress and the systemic immune response, and attenuate disease severity. Enteral nutrition might also reduce bacterial translocation and infective complications by maintaining the structural integrity of the gut. In addition, enteral nutrition is considered an effective means of providing stress ulcer prophylaxis, although it may raise gastric pH and theoretically increase rates of nosocomial infection or neutralise the effects of ulcer protective agents (Hinds 1999; McClave 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

ICU patients are at risk of developing stress ulcers. A proportion of these patients will develop clinically important bleeding, and the mortality rate in such patients is high (48.5% to 65%). Several RCTs, non‐randomised studies, and cohort studies have studied the role of different stress ulcer prophylactic drugs and strategies for prevention of stress ulcers and thereby upper GI bleeding. Stress ulcer prophylaxis is, however, a risk factor for the development of ventilator‐associated pneumonia. Thus the benefits of stress ulcer prophylaxis need to be balanced against this risk.

Previous systematic reviews and meta‐analyses were narrowed to comparisons of two interventions, were inconclusive, or generated conflicting results (Cook 1994b; Cook 1995b; Cook 1996; Lin 2010; Messori 2000). These systematic reviews did not include commonly used proton pump inhibitors. Several more recent systematic reviews investigated the risk‐benefit profile of bleeding prophylaxis in ICU patients (Alquraini 2017; Alshamsi 2016; Krag 2014; Pilkington 2012). They most often investigated the effects of a single drug class versus another drug class.

Guidelines for the management of hospital‐acquired pneumonia in the United Kingdom have been produced by the working party on hospital‐acquired pneumonia of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (Masterton 2008). This group considered the results of a systematic review ‐ Collard 2003 ‐ and a narrative synthesis of seven meta‐analyses (Cook 1991; Cook 1995; Cook 1996; Messori 2000; Tryba 1991; Tryba 1991b; Tryba 1995). Analyses yielded discordant results but overall suggested that risk of developing ventilator‐associated pneumonia was reduced when patients were given sucralfate compared with H2 receptor antagonists (although not when compared with placebo), and evidence from one study suggested that risk of clinically significant bleeding was increased when sucralfate was given to prevent upper GI bleeding compared with H2 receptor antagonists. Guidelines recommended that stress ulcer prophylaxis should be avoided in people on mechanical ventilation to preserve gastric function and reduce ventilator‐associated pneumonia. If stress ulcer prophylaxis is indicated, then the advantage of sucralfate in reducing the incidence of ventilator‐associated pneumonia needs to be balanced with its increased risk of clinically significant upper GI bleeding (Masterton 2008).

A guideline for stress ulcer prophylaxis in the intensive care unit provided by the Danish Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine recommended, first, that stress ulcer prophylaxis should not be used as a routine measure in all critically ill patients and, second, that proton pump inhibitors should be used over H2 receptor antagonists (Rorbaek Madsen 2014).

A guideline from 1999 released by the American Society of Health‐System Pharmacists recommended that antacids, H2 receptor antagonists, or sucralfate should be administered to prevent stress ulcers in adults (Armstrong 1999). An updated version of the guideline is expected in 2018. The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma released a guideline in 2008 that recommended use of H2 receptor antagonists, cytoprotective agents, and some proton pump inhibitors as prophylactic treatment against stress ulcers and recommended against use of antacids (Guillamondegui 2008).

Still, a review of current evidence on different pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions for prophylaxis of upper GI bleeding comparing them versus no active treatment or other active treatments is needed to provide a comprehensive and systematic overview of the research evidence and the benefits and harms of bleeding prophylaxis in patients admitted to the ICU.

Objectives

To assess the effect and the risk‐benefit profile of interventions used to prevent upper GI bleeding in people admitted to level two and level three ICUs. These levels include all sick patients requiring support for organ failure/dysfunction in the ICU (Goldhil 2002).

Level two ICUs are for patients requiring detailed observation or intervention including support for a single failing organ system or postoperative care and patients stepping down from higher levels of care.

Level three ICUs are for patients requiring advanced respiratory support alone or basic respiratory support together with support for at least two organ systems.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We followed methods as described in the review protocol (George 2010). We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised controlled studies.

Types of participants

People (any age and gender) admitted to level two or level three ICUs for longer than 48 hours. We excluded studies in which participants were admitted to the ICU primarily for management of upper GI bleeding.

Types of interventions

We compared the following interventions administered by any route and at any dose.

Drugs that reduce gastric acid secretion

H2 receptor antagonists: ranitidine, cimetidine, famotidine, roxatidine, nizatidine, loxatidine, etc.

Proton pump inhibitors: esomeprazole, rabeprazole, omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, dexlansoprazole, etc.

Prostaglandin analogues: misoprostol, enprostil, rioprostil, etc.

Anticholinergics: pirenzepine, propantheline, oxyphenonium, doxepin, trimipramine, etc.

Potassium‐competitive acid blockers

Drugs that neutralise gastric acid (antacids)

Systemic: sodium bicarbonate, sodium citrate

Non‐systemic: magnesium hydroxide, magnesium trisilicate, aluminium hydroxide gel, magaldrate, calcium carbonate

Ulcer protectives

Sucralfate

Colloidal bismuth subcitrate

Ulcer healing drugs

Carbenoxolone sodium, deglycyrrhizinated liquorice

Others

Enteral and parenteral nutrition

Any other intervention used to reduce upper GI bleeding

Combinations of interventions (e.g. omeprazole‐bicarbonate combinations)

No prophylaxis

Placebo

We compared each class of drugs versus placebo or no prophylaxis (e.g. H2 receptor antagonists vs placebo or no prophylaxis), and we compared all classes of drugs against one another (e.g. H2 receptor antagonists vs proton pump inhibitors). We did not compare different drugs within a single class versus one another (e.g. ranitidine vs cimetidine) because this type of comparison did not fall within the focus of this review.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Clinically important GI bleeding

For the purposes of this review, we used the definition used by study authors to define clinically important upper GI bleeding. We recorded details of the definition used

Secondary outcomes

Nosocomial pneumonia

Nosocomial pneumonia including ventilator‐associated pneumonia is defined as pneumonia contracted in a hospital (nosocomial) by a patient on mechanical ventilatory support (by endotracheal tube or tracheostomy) for longer than 48 hours (Masterton 2008; Mayhall 2001)

Criteria used in the review for the diagnosis of ventilator‐associated pneumonia will be those used by study authors. This outcome also includes incidence of nosocomial pneumonia because definitions used varied across study reports

Mortality

All‐cause mortality in ICU

All‐cause mortality in hospital

Duration of ICU stay

Duration of intubation

This also includes duration of mechanical ventilation because definitions varied across study reports.

Blood transfusion

Number of participants requiring transfusion

Number of units of blood transfused

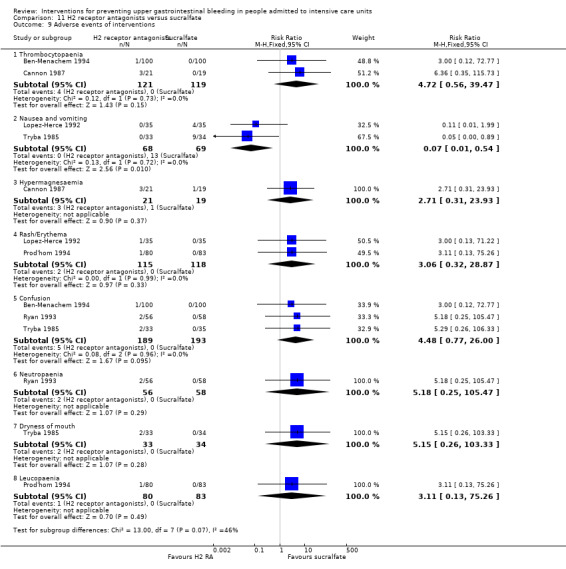

Adverse events of interventions

Serious adverse events leading to discontinuation of treatment, prolongation of ICU stay, or disability

Any other adverse event (e.g. thrombocytopaenia related to H2 receptor antagonists, any other adverse event).

Search methods for identification of studies

We attempted to identify all relevant RCTs and quasi‐randomised studies (in which allocation to interventions was attempted but could be predicted) for inclusion, regardless of date or language of publication or publication status (published, unpublished, or in press) We also looked for ongoing studies.

We excluded non‐randomised studies.

Electronic searches

With the help of the Cochrane Information Specialist, we searched the following databases up to 23 August 2017, using the search terms listed in Appendix 2: MEDLINE; Embase; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), published in the Cochrane Library (2017, Issue 8); the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Disease Group Specialised Register; and Latin American Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of all included studies and of relevant systematic reviews and meta‐analyses to identify relevant studies. We also searched the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform search portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) for ongoing clinical studies up to 23 August 2017. In addition, we searched all available conference proceedings until 2012 for relevant RCTs from the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Medicine (http://www.world‐critical‐care.org/) and the World Gastroenterology Organisation (http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/about‐wgo.html) websites. We contacted individual researchers working in this field, as well as organisations and pharmaceutical companies, to identify unpublished and ongoing studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors from a pool of four (ATG, IT, LEF, and RK) independently screened each citation and abstract yielded by the search strategy to identify potentially eligible studies. Two review authors from a pool of four (IT, LEF, PT, and JVP) independently checked the list of excluded studies to verify the appropriateness of reasons for their exclusion. We obtained and assessed full reports of potentially eligible studies for inclusion in the review based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If eligibility was unclear because information was inadequate or unclear, we attempted to contact study authors for clarification. Two review authors (IT, JJM) arranged for abstracts of articles written in non‐English languages to be translated for assessment against inclusion. We resolved disagreements through discussion and scrutinised each study report to ensure that RCTs with multiple publications were included only once by linking additional reports to the original study report included in the reference list of included studies. We documented reasons for exclusion of studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors from a pool of four (IT, LEF, ATG, and RK) independently extracted data from studies using pre‐tested data extraction forms. We resolved disagreements related to data extraction by referring to the study report and by having discussions. When available, we extracted data on the following.

Population characteristics

Type of ICU care (level two or three); inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants, as well as their age and gender and the number of participants randomised to each group and included in the study overall.

Interventions

Details of interventions given (dose, route, duration); additional interventions used in each arm (e.g. enteral feeds, antibiotics).

Outcomes

Definitions or criteria used for the diagnosis of clinically significant upper GI bleeding (and the source of bleeding), pneumonia (and types of pathogens and sensitivity patterns, if available) and ventilator‐associated pneumonia; number of participants experiencing each outcome; and numbers of dropouts and withdrawals with reasons. When data were insufficient or missing, we attempted to contact the study authors.

For continuous outcomes, we extracted arithmetic mean values, standard deviations, and number of participants in each study arm for whom the outcome was assessed. We noted whether numbers assessed in the study were the numbers of participants who completed the study or the numbers randomised. If medians were reported, we attempted to extract ranges or interquartile ranges.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors from a pool of six (IT, LEF, ATG, RK, PT, and JVP) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study. We resolved disagreements by referring to the study report, by corresponding with the authors of the report, and by having discussions. We assessed each study on the domains of sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting; and other sources of bias. We judged the risk of bias as 'high', 'low', or 'unclear', using guidelines (Higgins 2011) to make these judgements. We recorded this information for each included study in a 'Risk of bias' table in Review Manager (RevMan) 5.2 and summarised the risk of bias for each study in a summary figure and graph. We classified a study's overall risk of bias as high if the study had high risk of bias in any domain. Likewise, we classified the risk of bias as unclear if the study had no high risk of bias and had unclear risk of bias in any domain. Last, we classified a study's overall risk of bias as low if the study had low risk of bias in all domains.

We judged all included studies as being at low risk for detection bias for objectively determined outcomes of 'clinically important GI bleeding' and 'nosocomial pneumonia' if detected through a clear definition mentioned in the study, or if blinding of outcome assessors was clearly described. For other outcomes of interest, we judged the studies as having low risk of detection bias if these outcomes were mainly objective in nature. We judged studies as having unclear risk of detection bias on an outcome basis if they did not address upper GI bleeding or nosocomial pneumonia.

We classified studies that did not include a placebo arm and used different modes of administering study interventions as having high risk of performance bias, as it would not have been possible to blind study personnel and participants.

Measures of treatment effect

We used risk ratios for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences for continuous outcomes, with their respective 95% confidence intervals.

Unit of analysis issues

When outcomes were reported both at baseline and at follow‐up or at study endpoints, we used endpoint data preferentially over scores of the mean change from baseline because the standard deviation of this mean change for each treatment group often was not reported. Had only change scores been available from any study, we would have combined endpoint and change scores.

If studies had reported count data, we would have extracted the total number of events in each group, the total extent of person‐time at risk in each group, and the total number of participants in each group. If this information had not been available, we would have attempted to extract alternative summary statistics such as rate ratios and confidence intervals, if available. If count data had been presented as dichotomous outcomes, we would have extracted the number of participants in each intervention group and the number of participants in each intervention group who experienced at least one event. If count data were presented as continuous outcomes or as time‐to‐event outcomes, we would have attempted to extract the same information as outlined for continuous and time‐to‐event outcomes.

In case we would have identified any cluster‐randomised studies, and if their results had been adjusted for clustering, we would have combined the adjusted measures of effects. If results were not adjusted for clustering, we would have attempted to adjust the results by multiplying standard errors of the estimates by the square root of the design effect when the design effect was calculated as DEff = 1 + (M ‐ 1) ICC, where M is the average cluster size and ICC is the intracluster coefficient. If this was not possible, we would not have combined them in a meta‐analysis but would have presented these results in an additional table.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to obtain missing data from study authors. When possible, we extracted data to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis in which all randomised participants would be analysed in the groups to which they were originally assigned. Our primary analysis was a complete case analysis. If we noted a discrepancy in the numbers randomised and the numbers analysed for each treatment group, we calculated the percentage lost to follow‐up in each group and reported this information. If dropouts exceeded 10% for any study, we assigned the worst outcome to those lost to follow‐up for dichotomous outcomes and assessed the impact of this by performing sensitivity analyses.

For continuous data that were missing standard deviations, we calculated these from other available data such as standard errors, or we imputed them using the methods suggested in Deeks 2011. We did not make any assumptions about loss to follow‐up for continuous data, and we will analyse results for those who complete the study.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity between studies by visually examining the forest plot to check for overlapping confidence intervals and by using the Chi² test for homogeneity with a 10% level of significance and the I² statistic. Although we acknowledge that this cutoff is arbitrary, we interpreted I² values from 0% to 40% as possibly not important, from 30% to 60% as moderate heterogeneity, from 50% to 90% as substantial heterogeneity, and from 75% to 100% as considerable heterogeneity, depending on whether inconsistency in results was due to differences in the direction of effect estimates between studies rather than to differences in the magnitude of effect estimates favouring an intervention, as well as the strength of evidence for heterogeneity seen in the P value for the Chi² test for heterogeneity (Deeks 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

Apart from assessing the risk of selective outcome reporting considered under Assessment of risk of bias in included studies, we assessed the likelihood of potential publication bias by using funnel plots, provided that at least 10 studies were included in a meta‐analysis.

Data synthesis

We first compared interventions used to prevent upper GI bleeding versus placebo or no intervention in people admitted to intensive care units. We stratified analyses according to drug class of the active intervention used versus placebo or no treatment. We included three‐armed studies in these comparisons by splitting the comparison arm in two, as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We then compared specific interventions or combinations of interventions grouped under drug classes. For three‐armed studies, we considered only the two relevant arms in comparisons of drug classes.

We synthesised comparable data using the Mantel‐Haenszel method to derive pooled, weighted risk ratios in fixed‐effect meta‐analyses. We combined continuous data summarised by arithmetic means and standard deviations using the weighted mean difference. We used the random‐effects model for data synthesis when we identified heterogeneity as significant (see above) and found that it could not be explained by subgroup analyses (see below).

Had continuous data been summarised using geometric means, we would have combined them on the log scale using the generic inverse variance method and would have reported them on the natural scale. We would have compared count data using rate ratios when the total number of events in each group and the total extent of person‐time at risk in each group were available, or by using relative risks or weighted mean differences when data were presented in dichotomous or continuous form, respectively. We would have combined hazard ratios from survival data on the log scale by using the inverse variance method and would have presented them on the natural scale.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If data permitted, we intended to carry out the following subgroup analyses for each comparison.

Presence or absence of bleeding disorders (e.g. coagulopathies, defined as thrombocyte count < 50/nL, partial thromboplastin time (PTT) > 2 times the upper limit of the normal range, international normalised ratio (INR) > 1.5).

Pneumonia at the time of ICU admission.

Adults (≥ 18 years to 65 years) versus older adults (≥ 65 years) versus children and adolescents (< 18 years).

Use of co‐interventions that may affect outcomes (e.g. enteral feeds, prophylactic antibiotics, other measures used for selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD)).

For the outcome of nosocomial pneumonia, we planned to further subgroup data by development of early‐onset nosocomial pneumonia (within four days on ventilation) or late‐onset nosocomial pneumonia (five or more days on ventilation), or by rating data as unclear (if this subgrouping is not possible by using information in the report or by contacting study authors). We identified no studies within the same comparison that distinguished between early and late onset of pneumonia and determined that a subgroup analysis was not feasible.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses to investigate robustness of results for the primary outcome by evaluating outcomes in studies with low risk of bias versus outcomes in studies with high or unclear risk of bias. We also undertook sensitivity analyses if studies reported dropout rates of 10% or greater, to ascertain differences in outcomes of intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis and analysis of completers. We assessed robustness of results using published and validated criteria to diagnose clinically important bleeding and nosocomial pneumonia.

Summarising results

We imported data for the following outcomes from Review Manager (RevMan) 5.2 into the Guideline Development Tool (GRADEpro 2015) and used this information to construct 'Summary of findings' (SoF) tables and to guide the conclusions of this review. We considered the following outcomes as critically important or important for clinical decisions for inclusion in these summary tables.

Clinically important upper GI bleeding.

Nosocomial pneumonia.

All‐cause mortality in ICU.

Duration of ICU stay.

Number of participants requiring blood transfusions.

Serious adverse events.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies,Characteristics of excluded studies,Characteristics of ongoing studies, and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

We retrieved 2802 records through database searching between July 2010 and August 2017. We identified 43 additional records from other sources, which included review of our personal files and records, correspondence with experts in the field, and review of bibliographies of review articles. After resolving duplicates, the final list included 2292 records. After discarding reports that clearly were not relevant, we identified 199 records as potentially eligible for inclusion. In the end, we included in the review 129 records reporting on 121 studies, of which 12 were ongoing studies and two were awaiting classification. We excluded 71 records. The process of study selection is described in Figure 1.

1.

PRISMA flow chart of included studies.

Included studies

We have described in the Characteristics of included studies tables the 107 competed studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review and have summarised them below. All studies took place in an ICU setting and included critically ill adults or children or both.

Participants, interventions, and comparisons

The 107 studies randomised a total of 15,057 participants to 27 comparisons involving 14 different treatment modalities. Most studies specifically mentioned that they randomised individuals who had no history of GI haemorrhage or peptic ulcer or gastritis or were not undergoing treatments for any of these conditions. The included studies included participants admitted to intensive care units, although the level of ICU into which participants were admitted was not clearly mentioned. Neither was a duration of ICU admission ≥ 48 hours ‐ a necessary inclusion criterion across studies. Among the included studies were five exclusively paediatric studies (Behrens 1994; Kuusela 1997; Lacroix 1986; Lopez‐Herce 1992; Yildizdas 2002); six quasi‐randomised studies (Borrero 1984; Borrero 1985; Borrero 1986; Brophy 2010; Martin 1980; Weigelt 1981); and seven studies reported as conference abstracts only (Fink 2003; Fogas 2013; Larson 1989; Luk 1982; Phillips 1998; Selvanderan 2016; Wee 2013).

Interventions versus placebo or no prophylaxis

We included a total of 32 studies involving 2151 individuals in any interventional arm (H2 receptor antagonists, antacids, sucralfate, proton pump inhibitors, prostaglandin analogues, or anticholinergics) (n = 1249) or in the placebo or no prophylaxis arms (n = 902).

H2 receptor antagonists versus placebo or no prophylaxis

We included a total of 26 studies involving 2210 individuals in the H2 receptor antagonist (ranitidine, cimetidine, or famotidine) arm (n = 1123) or in the placebo or no prophylaxis arm (n = 1087) (Apte 1992; Basso 1981; Ben‐Menachem 1994; Burgess 1995; Chan 1995; Darlong 2003; Friedman 1982; Groll 1986; Halloran 1980; Hanisch 1998; Kantorova 2004; Karlstadt 1990; Kaushal 2000; Lacroix 1986; Larson 1989; Lopez‐Herce 1992; Luk 1982; Martin 1993; Metz 1993; Peura 1985; Powell 1993; Reusser 1990; Rohde 1980; van den Berg 1985; Yildizdas 2002; Zinner 1981). Enteral feeding/nasogastric feeding/parenteral feeding was administered to many participants in the following studies: Apte 1992; Ben‐Menachem 1994; Darlong 2003; Halloran 1980; Kantorova 2004; Karlstadt 1990; Martin 1993; Peura 1985; and van den Berg 1985.

Proton pump inhibitors versus placebo or no prophylaxis

We included a total of five studies randomising 482 individuals to a proton pump inhibitor (omeprazole or pantoprazole) (n = 141) or to placebo or no prophylaxis (n = 133) (Ali 2016; Kantorova 2004; Powell 1993; Selvanderan 2016; Yildizdas 2002). Enteral feeds were administered alone in Kantorova 2004. Selvanderan 2016 did not report how many participants were randomised to each arm, so we were unable to add a total of 214 participants to the total numbers of participants in respective study arms.

Proton pump inhibitors plus sucralfate versus no prophylaxis

One study randomised 80 participants to receive proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole or lansoprazole) plus sucralfate (n = 40) or no prophylaxis (n = 40). Participants who did not receive prophylaxis did receive enteral nutrition (Fang 2014).

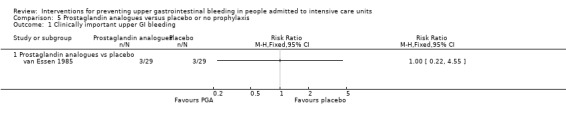

Prostaglandin analogues versus placebo or no prophylaxis

One study randomised 58 individuals to receive either a prostaglandin analogue (n = 29) or placebo (n = 29) (van Essen 1985).

Anticholinergics versus placebo or no prophylaxis

A total of two studies involving 131 individuals who received an anticholinergic (n = 59) or a placebo or no prophylaxis (n = 72) were included in the analysis (Hanisch 1998; Krakamp 1989). Ranitidine was administered to both arms in one study (Krakamp 1989).

Antacids versus placebo or no prophylaxis

A total of eight studies involving a total of 774 individuals in the antacid arm (n = 386) or placebo or no prophylaxis arm (n = 388) were included in the analysis (Basso 1981; Friedman 1982; Hastings 1978; Lopez‐Herce 1992; Luk 1982; Macdougall 1977; Pinilla 1985; Zinner 1981).

Sucralfate versus placebo or no prophylaxis

A total of seven studies involving a total of 598 individuals in the sucralfate arm (n = 302) and in the placebo or no prophylaxis arm (n = 296) were included in the analysis (Ben‐Menachem 1994; Darlong 2003; Eddleston 1994; Kantorova 2004; Kaushal 2000; Lopez‐Herce 1992; Yildizdas 2002). Enteral feeds/nasogastric feeding/parenteral feeds were administered to many participants in the following studies: Ben‐Menachem 1994 and Kantorova 2004.

Interventions compared with one another

H2 receptor antagonists versus proton pump inhibitors

We included a total of 20 studies involving 2370 individuals given H2 receptor antagonists (ranitidine, cimetidine, or famotidine) (n = 1037) or proton pump inhibitors (esomeprazole, omeprazole, rabeprazole, or pantoprazole) (n = 1333) (De Azevedo 2000; Bashar 2013; Brophy 2010; Conrad 2005; Fink 2003; Fogas 2013; Hata 2005; Kantorova 2004; Lee 2014; Levy 1997; Maasoumi 2016; Ng 2012; Phillips 1998; Powell 1993; Solouki 2009; Somberg 2008; Tabeefar 2012; Terzi 2009; Wee 2013; Yildizdas 2002). Enteral feeds/nasogastric feeding/parenteral feeds were administered to many participants in the following studies: Brophy 2010,Conrad 2005,Kantorova 2004,Solouki 2009, and Somberg 2008. Somberg 2008 randomised participants to four different intermittent dosing regimens of pantoprazole. These arms were combined to form a common interventional arm versus the H2 receptor antagonist, as the review did not aim to investigate efficacy of the same drug based on dose or mode of administration. Fogas 2013 did not report details on the H2 receptor antagonist and proton pump inhibitor used. One study did not report any outcomes of relevance for this review (Tabeefar 2012).

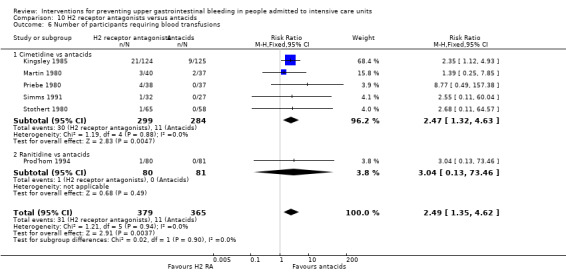

H2 receptor antagonists versus antacids

We included a total of 18 studies involving 1795 individuals in H2 receptor antagonist (ranitidine, cimetidine, or famotidine) (n = 957) or antacid interventional arms (n = 835) (Basso 1981; Cannon 1987; Friedman 1982; Kingsley 1985; Lamothe 1991; Lopez‐Herce 1992; Luk 1982; Martin 1980; Noseworthy 1987; Poleski 1986; Priebe 1980; Prod'hom 1994; Simms 1991; Stothert 1980; Thomason 1996; Tryba 1985; Weigelt 1981; Zinner 1981). Tryba 1985 administered 50 mg of pirenzipine daily to all randomised participants. Enteral feeds were administered to many participants (Cannon 1987; Simms 1991; Tryba 1985). Lamothe 1991 included four arms (ranitidine, cimetidine, famotidine, and antacids); H2 receptor antagonists were combined to form a common interventional arm versus antacids, as the review did not aim to investigate intraclass efficacy among included interventions.

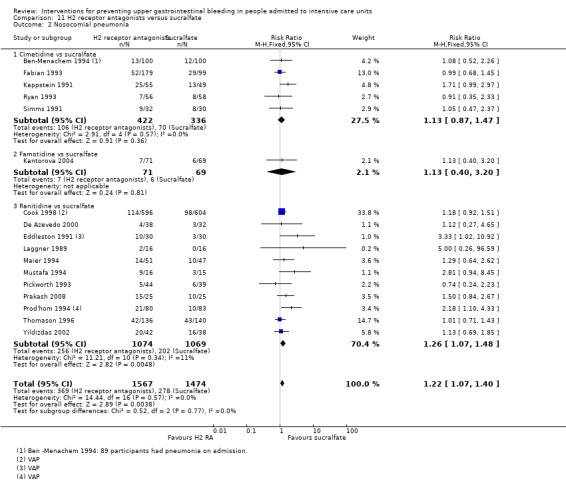

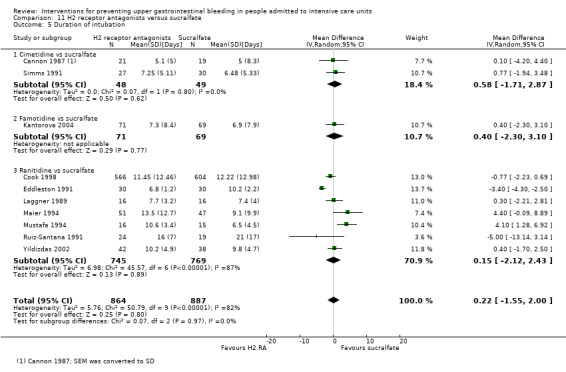

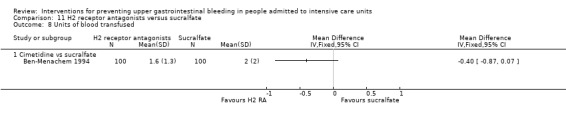

H2 receptor antagonists versus sucralfate

We included a total of 26 studies involving 3352 individuals given H2 receptor antagonists (ranitidine, cimetidine, or famotidine) (n = 1772) or sucralfate (n = 1647) (Ben‐Menachem 1994; Cannon 1987; Cook 1998; Darlong 2003; De Azevedo 2000; Eddleston 1991; Fabian 1993; Kantorova 2004; Kappstein 1991; Kaushal 2000; Laggner 1988; Laggner 1989; Lopez‐Herce 1992; Maier 1994; Mustafa 1994; Ortiz 1998; Pickworth 1993; Prakash 2008; Prod'hom 1994; Ruiz‐Santana 1991; Ryan 1993; Simms 1991; Stoehr 2006; Thomason 1996; Tryba 1985; Yildizdas 2002). Tryba 1985 administered 50 mg of pirenzipine daily to all randomised participants. Enteral feeds/nasogastric feeding/parenteral feeds were administered to many participants in the following studies: Ben‐Menachem 1994,Cannon 1987,Cook 1998,Kantorova 2004,Mustafa 1994,Prod'hom 1994,Ruiz‐Santana 1991,Simms 1991, and Tryba 1985. Two studies randomised participants to more than one arm of H2 receptor antagonists (cimetidine bolus and continuous infusion) (Fabian 1993; Ortiz 1998). These arms were combined to form a common interventional arm versus sucralfate, as the review did not aim to investigate efficacy of the same drug based on dose or mode of administration.

H2 receptor antagonists versus anticholinergics

A total of four studies involved 599 individuals given H2 receptor antagonists (ranitidine or famotidine) (n = 307) or anticholinergics (n = 292) (Barandun 1985; Behrens 1994; Hanisch 1998; Tryba 1988). Parenteral nutrition was given at the time of endoscopy to participants in the second study alone.

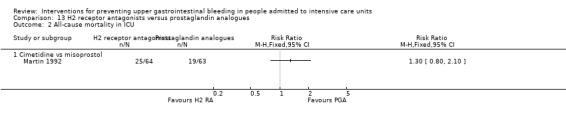

H2 receptor antagonists versus prostaglandin analogues

One study randomised 127 individuals to receive H2 receptor antagonists (cimetidine) (n = 64) or a prostaglandin analogue (misoprostol) (n = 63) (Martin 1992).

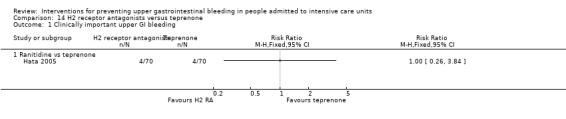

H2 receptor antagonists versus teprenone

One study randomised 140 individuals to receive ranitidine (n = 70) or teprenone (n = 70) (Hata 2005).

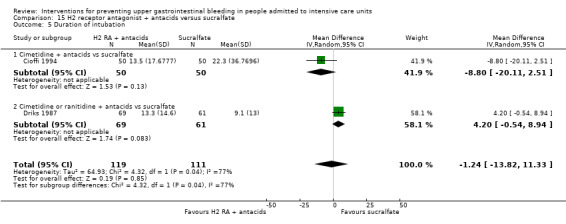

H2 receptor antagonist + antacids versus sucralfate

A total of three studies involving 281 individuals in an interventional arm that combined H2 receptor antagonists with antacids (n = 144) or in the sucralfate arm (n = 137) were included in the analysis (Cioffi 1994; Driks 1987; Sirvent 1994). Enteral feeding/ parenteral nutrition was administered in Cioffi 1994 and Sirvent 1994. Conventional therapy with antacids, H2 receptor antagonists (cimetidine or ranitidine), or both was administered in Driks 1987; cimetidine was given in the first study and ranitidine in the third study.

Proton pump inhibitors versus teprenone

Hata 2005 randomised 140 individuals to receive rabeprazole (n = 70) or teprenone (n = 70).

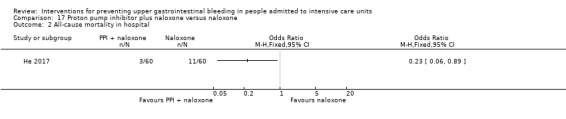

Proton pump inhibitors plus naloxone versus naloxone

He 2017 randomised 120 participants to receive pantoprazole plus naloxone (n = 60) or naloxone alone (n = 60).

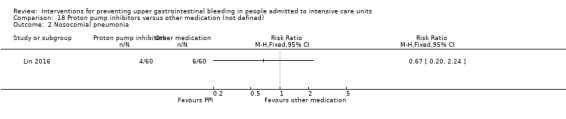

Proton pump inhibitors versus other medication

Lin 2016 randomised 120 individuals to receive lansoprazole (n = 60) or another medication not further specified (n = 60).

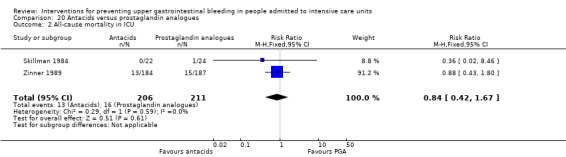

Antacids versus prostaglandin analogues

Skillman 1984 and Zinner 1989, which included 417 individuals in the antacid arm (n = 206) or the prostaglandin analogue arm (n = 211), were included in the analysis.

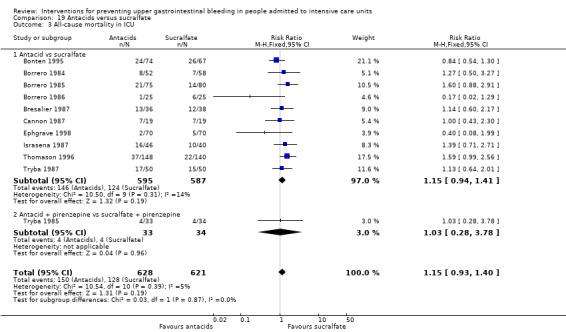

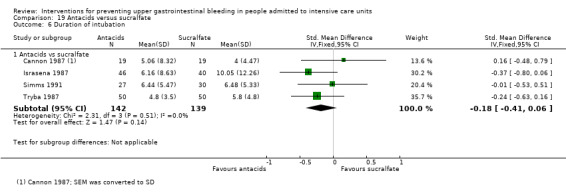

Antacids versus sucralfate

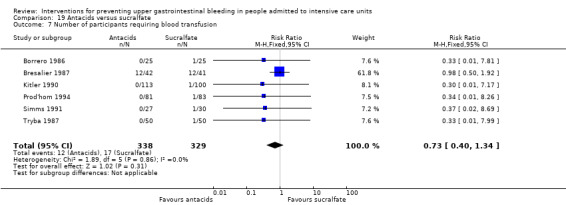

We included a total of 16 studies involving 1772 individuals given antacids (n = 884) or sucralfate (n = 888) (Bonten 1995; Borrero 1984; Borrero 1985; Borrero 1986; Bresalier 1987; Cannon 1987; Ephgrave 1998; Israsena 1987, Kitler 1990; Lopez‐Herce 1992; Mahul 1992; Prod'hom 1994; Simms 1991; Thomason 1996; Tryba 1987; Tryba 1985). Tryba 1985 administered 50 mg of pirenzipine daily to all randomised participants. Enteral feeds/nasogastric feeding/parenteral feeds were administered to many participants in the following studies: Bonten 1995,Cannon 1987,Ephgrave 1998,Mahul 1992,Prod'hom 1994,Simms 1991, and Tryba 1985.

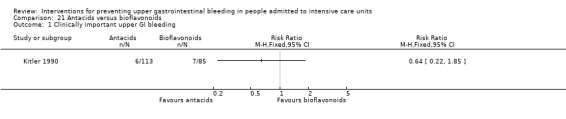

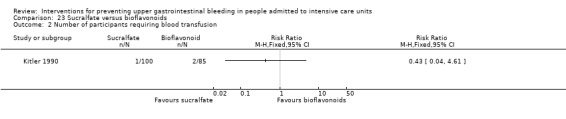

Antacids versus bioflavonoids

Kitler 1990 randomised 198 individuals to receive an antacid (n = 113) or a bioflavonoid ('Maciadanol') (n = 85).

Sucralfate versus proton pump Inhibitors

We included a total of four studies involving a total of 424 individuals given sucralfate (n = 205) and a proton pump inhibitor (omeprazole, pantoprazole) (n = 219) (De Azevedo 2000; Kantorova 2004; Khorvash 2014; Yildizdas 2002). Enteral feeds/nasogastric feeding/parenteral feeds were administered to many participants in one study (Kantorova 2004).

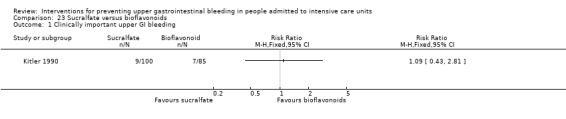

Sucralfate versus bioflavonoids

Kitler 1990 randomised 198 individuals to receive sucralfate (n = 113) or a bioflavonoid ('Maciadanol') (n = 85).

Non‐pharmacological interventions

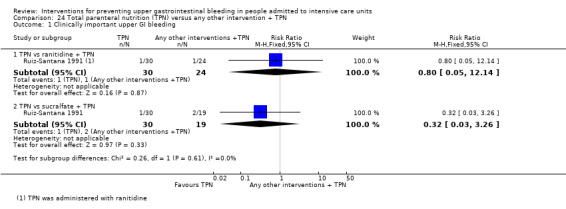

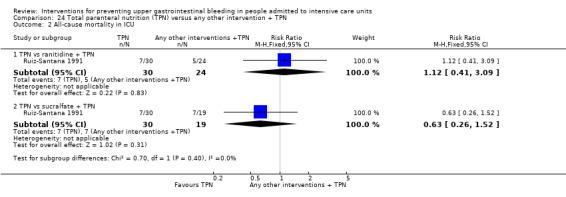

Total parenteral nutrition versus any other interventions plus total parenteral nutrition

Ruiz‐Santana 1991 randomised 73 individuals to receive total parenteral nutrition (n = 30), total parenteral nutrition plus ranitidine (n = 24), or total parenteral nutrition plus sucralfate (n = 19).

Bowel stimulation protocol versus no prophylaxis

Wang 2015 randomised 100 individuals to receive treatment through a bowel stimulation protocol including abdominal massage, rectal digital stimulation, and enema (n = 50) or no prophylaxis (n = 50).

Nasojejunal nutrition versus nasogastric nutrition

Davies 2012 randomised 180 individuals to nasojejunal (n = 91) or nasogastric nutrition (n = 89).

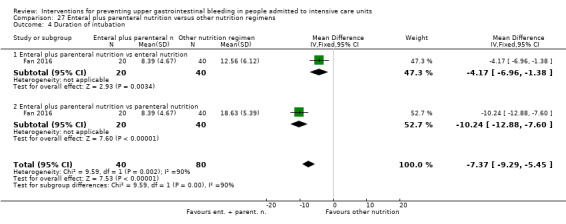

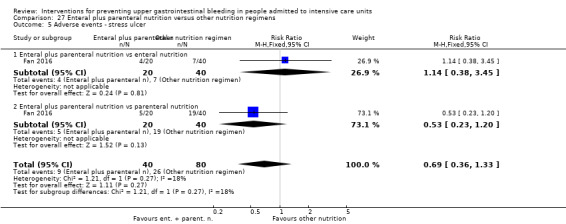

Enteral plus parenteral nutrition versus other nutrition regimens

Fan 2016 randomised 120 evenly to receive enteral plus parenteral nutrition or enteral nutrition alone or parenteral nutrition alone.

Funding sources

Most study reports that included information about funding sources mentioned that researchers had received funding from pharmaceutical companies that were involved in production of the tested interventions (23 studies). A total of 17 studies reported institutional funding from, for example, the hospitals involved in the study. Sixty studies provided no information about funding.

Excluded studies

We excluded 71 records from the review mainly for these reasons: 30 studies assessed the efficacy of drugs within the same class, 15 studies were not RCTs, participants in 15 studies were not admitted to the ICU or had an indication that did not fit our inclusion criteria, six studies assessed no health outcomes that were of relevance for the review, and five studies did not take place in an ICU setting. We have mentioned the reasons for exclusion more elaborately under Characteristics of excluded studies.

Ongoing studies

We retrieved 12 ongoing studies that might be relevant to this review and will be included in the next update.

Studies awaiting classification

We were unable to obtain the full text of two studies and classified them as studies awaiting classification (Labattut 1992; Morris 2001).

We retrieved from study registries 12 studies that were ongoing or finished with no publication identified (ACTRN12616000481471; EUCTR2015‐000318‐24‐DK; EudraCT 2007‐006102‐19; IRCT201104134578N2; ISRCTN12845429; Krag 2016; NCT00590928; NCT00702871; NCT02157376; NCT02290327; NCT02718261; NCT03098537).

Risk of bias in included studies

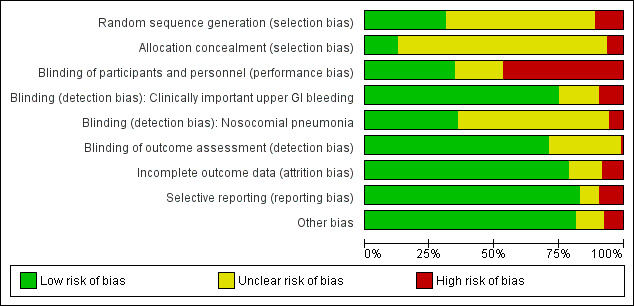

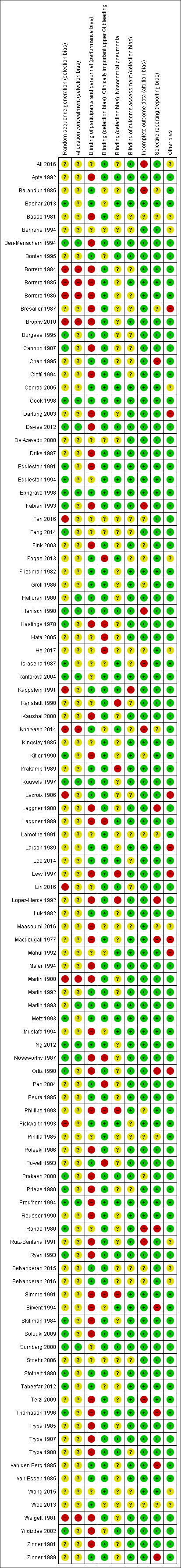

Assessments regarding risk of bias for all included studies are depicted in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

A total of 33 studies clearly mentioned the method employed for generating a random sequence (Bashar 2013; Ben‐Menachem 1994; Burgess 1995; Cannon 1987; Cook 1998; Davies 2012; Eddleston 1991; Eddleston 1994; Ephgrave 1998; Fabian 1993; Fang 2014; Hanisch 1998; Hastings 1978; Israsena 1987; Kantorova 2004; Kitler 1990; Kuusela 1997; Metz 1993; Ng 2012; Noseworthy 1987; Ortiz 1998; Prakash 2008; Priebe 1980; Prod'hom 1994; Rohde 1980; Ryan 1993; Skillman 1984; Solouki 2009; Somberg 2008; Stothert 1980; Tabeefar 2012; Thomason 1996; Yildizdas 2002). Thirteen studies mentioned the method employed to conceal the allocation, ensuring that they were clearly free from any selection bias (Ben‐Menachem 1994; Cook 1998; Davies 2012; Ephgrave 1998; Halloran 1980; Hanisch 1998; Kantorova 2004; Kuusela 1997; Martin 1993; Ng 2012; Noseworthy 1987; Prod'hom 1994; Somberg 2008).

Seven studies were quasi‐randomised studies and therefore were judged to have higher risk of selection bias compared with the other studies, which had unclear risk for the domains of 'sequence generation' and 'allocation concealment' (Borrero 1984; Borrero 1985; Borrero 1986; Brophy 2010; Martin 1980; Pickworth 1993; Weigelt 1981).

Blinding

Performance bias

Thirty‐seven studies clearly mentioned the methods employed for blinding participants and personnel across all outcomes, and so review authors judged their risk of performance bias as low (Barandun 1985; Bashar 2013; Bonten 1995; Burgess 1995; Chan 1995; Conrad 2005; Cook 1998; Ephgrave 1998; Fogas 2013; Friedman 1982; Groll 1986; Halloran 1980; Hanisch 1998; Kappstein 1991; Khorvash 2014; Krakamp 1989; Kuusela 1997; Lacroix 1986; Larson 1989; Lee 2014; Luk 1982; Martin 1992; Martin 1993; Metz 1993; Ng 2012; Pan 2004; Peura 1985; Pickworth 1993; Powell 1993; Selvanderan 2015; Selvanderan 2016; Stothert 1980; Tabeefar 2012; van den Berg 1985; van Essen 1985; Wee 2013; Zinner 1989).

Detection bias

Eighty studies reported that researchers used a clear definition for detection of upper GI bleeding, and review authors judged these studies as having low risk of detection bias for this outcome (Ali 2016; Apte 1992; Basso 1981; Ben‐Menachem 1994; Borrero 1984; Borrero 1985; Borrero 1986; Bresalier 1987; Brophy 2010; Burgess 1995; Cannon 1987; Chan 1995; Cioffi 1994; Conrad 2005; Cook 1998; Darlong 2003; Davies 2012; Driks 1987; Eddleston 1991; Eddleston 1994; Ephgrave 1998; Fabian 1993; Fink 2003; Friedman 1982; Groll 1986; Halloran 1980; Hanisch 1998; Kantorova 2004; Kappstein 1991; Karlstadt 1990; Kaushal 2000; Kingsley 1985; Kitler 1990; Krakamp 1989; Kuusela 1997; Lacroix 1986; Laggner 1988; Lamothe 1991; Larson 1989; Lee 2014; Levy 1997; Lin 2016; Lopez‐Herce 1992; Luk 1982; Macdougall 1977; Maier 1994; Martin 1980; Martin 1992; Martin 1993; Metz 1993; Ng 2012; Ortiz 1998; Peura 1985; Pickworth 1993; Pinilla 1985; Poleski 1986; Prakash 2008; Priebe 1980; Prod'hom 1994; Reusser 1990; Rohde 1980; Ruiz‐Santana 1991; Ryan 1993; Selvanderan 2015; Selvanderan 2016; Skillman 1984; Solouki 2009; Somberg 2008; Stothert 1980; Terzi 2009; Thomason 1996; Tryba 1985; Tryba 1987; Tryba 1988; van den Berg 1985; van Essen 1985; Wang 2015; Weigelt 1981; Zinner 1981; Zinner 1989). Thirty‐eight studies reported that researchers used a clear definition for detection of nosocomial pneumonia, and review authors judged their risk of detection bias as low (Apte 1992; Bashar 2013; Ben‐Menachem 1994; Bonten 1995; Cioffi 1994; Conrad 2005; Cook 1998; Davies 2012; Driks 1987; Eddleston 1991; Eddleston 1994; Ephgrave 1998; Fabian 1993; Fogas 2013; Hanisch 1998; Israsena 1987; Kantorova 2004; Kappstein 1991; Khorvash 2014; Laggner 1989; Lee 2014; Lin 2016; Mahul 1992; Maier 1994; Martin 1993; Metz 1993; Mustafa 1994; Pickworth 1993; Prakash 2008; Prod'hom 1994; Ryan 1993; Sirvent 1994; Solouki 2009; Somberg 2008; Thomason 1996; Tryba 1987; Tryba 1988; Yildizdas 2002).

Incomplete outcome data

High risk of attrition bias was suspected in eight studies (Barandun 1985; Fabian 1993; Hanisch 1998; Israsena 1987; Khorvash 2014; Rohde 1980; Ruiz‐Santana 1991; Terzi 2009). Although two studies conducted per‐protocol analyses for outcomes of interest and excluded participants, reports show an imbalance between interventional arms with respect to final numbers of participants (Fabian 1993; Ruiz‐Santana 1991). Therefore, review authors judged the likelihood of attrition bias as high. Only one strata of the study was available for analysis (Rohde 1980), and 16% of participants were not accounted for in two studies, respectively (Barandun 1985; Terzi 2009).

Fourteen studies, which reported that researchers conducted a per‐protocol analysis for outcomes of interest and excluded participants, showed no imbalance between interventional arms with respect to final numbers of participants (Bresalier 1987; Hanisch 1998; Kantorova 2004; Lopez‐Herce 1992; Poleski 1986; Prod'hom 1994; Reusser 1990; Skillman 1984; Stothert 1980; Thomason 1996; van den Berg 1985; van Essen 1985; Yildizdas 2002; Zinner 1989). Therefore review authors judged the likelihood of bias due to attrition as low.

The following studies were unclear on the numbers of participants initially randomised to the interventional arms: Fink 2003,Groll 1986,Kitler 1990,Phillips 1998, and Prakash 2008. Therefore review authors determined that they had unclear risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

All studies analysed and reported intended outcomes except the following.

Barandun 1985 and Laggner 1988 were unclear on reporting of adverse events of interventions.

Ortiz 1998 and Chan 1995 showed selective or unclear reporting on secondary outcomes of interest.

Rohde 1980 reported outcomes for only one strata of the study (participants with polytrauma); all other strata were excluded from analysis.

Thomason 1996 conducted an intention‐to‐treat analysis for the outcomes of pneumonia and all‐cause mortality only.

Sirvent 1994, van den Berg 1985, Lopez‐Herce 1992, and Macdougall 1977 did not report all‐cause mortality separately for each intervention arm.

Zinner 1989 was unclear on the total number of participants in each arm when reporting adverse events due to interventions.

Chan 1995 reported more outcomes than initially proposed in the Methods section.

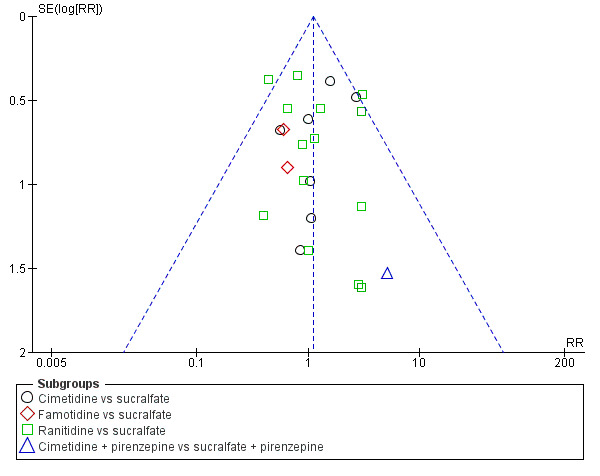

We evaluated risk of reporting bias for clinical upper GI bleeding for the following comparisons: any intervention versus no prophylaxis or placebo, H2 receptor antagonists versus no prophylaxis or placebo, H2 receptor antagonists versus proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor antagonists versus antacids, H2 receptor antagonists versus sucralfate, and antacids versus sucralfate. These were the only comparisons that involved at least 10 studies. Visual inspection of funnel plots revealed no evidence of reporting bias (Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6; Figure 7; Figure 8; Figure 9).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Interventions versus placebo or no prophylaxis, outcome: 1.1 Clinically important upper GI bleeding.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 H2 receptor antagonists versus placebo or no prophylaxis, outcome: 2.1 Clinically important upper GI bleeding.

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 9 H2 receptor antagonists versus proton pump inhibitors, outcome: 9.1 Clinically important upper GI bleeding.

7.

Funnel plot of comparison: 10 H2 receptor antagonists versus antacids, outcome: 10.1 Clinically important upper GI bleeding.

8.

Funnel plot of comparison: 11 H2 receptor antagonists versus sucralfate, outcome: 11.1 Clinically important upper GI bleeding.

9.

Funnel plot of comparison: 19 Antacids versus sucralfate, outcome: 19.1 Clinically important upper GI bleeding.

Other potential sources of bias

Review authors classified 20 studies as having unclear or high risk of bias, as reports were unclear on the baseline characteristics of randomised participants (Ali 2016; Basso 1981; Behrens 1994; Bresalier 1987; Conrad 2005; Darlong 2003; Fogas 2013; He 2017; Lacroix 1986; Larson 1989; Levy 1997; Maasoumi 2016; Macdougall 1977; Mahul 1992; Ortiz 1998; Ruiz‐Santana 1991; Selvanderan 2015; Selvanderan 2016; Wang 2015; Wee 2013). Three studies were published only as conference abstracts and did not report enough data for assessment of other biases (Fogas 2013; Selvanderan 2016; Wee 2013). These reasons are elaborately described in the risk of bias tables for these respective studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Interventions compared with placebo or no prophylaxis for preventing upper gastrointestinal bleeding in people admitted to intensive care units.

| Any intervention compared with placebo or no prophylaxis for preventing upper gastrointestinal bleeding in people admitted to intensive care units | ||||||

| Patient or population: people admitted to intensive care units Setting: ICU Intervention: any intervention Comparison: placebo or no prophylaxis | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no prophylaxis | Risk with Interventions | |||||

|

Clinically important upper GI bleeding Follow‐up: 15 days† |

Study population | RR 0.47 (0.39 to 0.57) | 3207 (30 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | ||

| 188 per 1000 | 88 per 1000 (73 to 107) | |||||

|

Nosocomial pneumonia Follow‐up: 48 hours after extubation‡ |

Study population | RR 1.15 (0.90 to 1.48) | 1331 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | ||

| 143 per 1000 | 164 per 1000 (129 to 211) | |||||

|

All‐cause mortality in ICU Follow‐up: 4 weeks§ |

Study population | RR 1.10 (0.90 to 1.34) | 2159 (19 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,d | ||

| 152 per 1000 | 168 per 1000 (137 to 204) | |||||

|

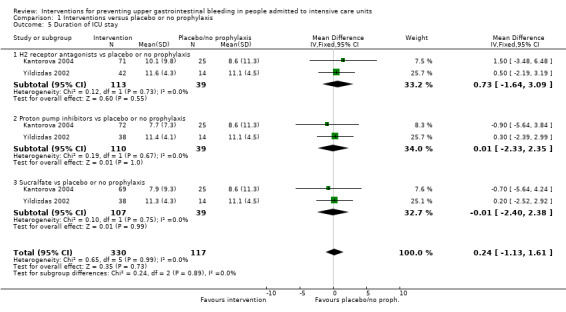

Duration of ICU stay Follow‐up: not reported |

Mean duration of ICU stay ranged from 8.6 to 11.1 days | MD 0.24 days higher (1.13 days lower to 1.61 higher days) | ‐ | 447 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,e | |

|

Number of participants requiring blood transfusion Follow‐up: 48 hours after discharge‡ |

Study population | RR 0.63 (0.41 to 0.97) | 981 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEf | ||

| 96 per 1000 | 60 per 1000 (39 to 93) | |||||

| Serious adverse events | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

‡Duration of follow‐up reported in one study. †Duration of follow‐up reported in four studies. §Duration of follow‐up reported in five studies. CI: confidence interval; GI: gastrointestinal; ICU: intensive care unit; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level for risk of bias because of high risk of selection bias in one study, high risk of performance bias in nine studies, high risk of detection bias in five studies, high risk of attrition bias in four studies, high risk of reporting bias in five studies, and high risk of other biases in four studies.

bDowngraded by one level for imprecision because effect estimate and 95% CI were compatible with benefit and harm.

cDowngraded by one level for risk of bias because of high risk of performance bias in three studies, high risk of detection bias in one study, and high risk of attrition bias in two studies.

dDowngraded by one level for risk of bias because of high risk of performance bias in seven studies and high risk of attrition bias in two studies.

eDowngraded by one level for risk of bias because of high risk of performance bias in one study.

fDowngraded by one level for risk of bias because of high risk of selection bias in one study, high risk of performance bias in two studies, high risk of attrition bias in one study, high risk of reporting bias in one study, and high risk of other biases in one study.

Summary of findings 2. H2 receptor antagonists compared with placebo or no prophylaxis for preventing upper gastrointestinal bleeding in people admitted to intensive care units.

| H2 receptor antagonists compared with placebo or no prophylaxis for preventing upper gastrointestinal bleeding in people admitted to intensive care units | ||||||

| Patient or population: people admitted to intensive care units Setting: ICU Intervention: H2 receptor antagonists Comparison: placebo or no prophylaxis | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or no prophylaxis | Risk with H2 receptor antagonists | |||||

|

Clinically important upper GI bleeding Follow‐up: 15 days/weeks† |

Study population | RR 0.50 (0.36 to 0.70) | 2149 (24 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEa | ||

| 182 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (65 to 127) | |||||

|

Nosocomial pneumonia Follow‐up: 48 hours after extubation‡ |

Study population | RR 1.12 (0.85 to 1.48) | 945 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,c | ||

| 146 per 1000 | 164 per 1000 (124 to 216) | |||||

|

All‐cause mortality in ICU Follow‐up: 4 weeks§ |

Study population | RR 1.12 (0.88 to 1.42) | 1428 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,d | ||

| 145 per 1000 | 162 per 1000 (127 to 205) | |||||

|

Duration of ICU stay Follow‐up: not reported |

Mean duration of ICU stay ranged from 8.6 to 11.1 days | MD 0.73 days higher (0.92 days lower to 2.38 days higher) | ‐ | 230 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOWb,e | |

|

Number of participants requiring blood transfusions Follow‐up: 48 hours after extubationǁ |

Study population | RR 0.58 (0.36 to 0.95) | 655 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATEf | ||

| 112 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 (40 to 107) | |||||

| Serious adverse events | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

†Duration of follow‐up reported in four studies. ‡Duration of follow‐up reported in two studies. §Duration of follow‐up reported in five studies. ǁDuration of follow‐up reported in one study. CI: confidence interval; GI: gastrointestinal; ICU: intensive care unit; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level for risk of bias because of high risk of selection bias in one study, high risk of performance bias in eight studies, high risk of attrition bias in two studies, high risk of reporting bias in four studies, and high risk of other biases in three studies.

bDowngraded by one level for imprecision because 95% CI was compatible with benefit and harm.

cDowngraded by one level for risk of bias because of high risk performance bias in three studies and high risk of attrition bias in one study.

dDowngraded by one level for risk of bias because of high risk of performance bias in three studies and high risk of attrition bias in one study.