Abstract

Background

Acute spinal cord injury is a devastating condition typically affecting young people, mostly males. Steroid treatment in the early hours after the injury is aimed at reducing the extent of permanent paralysis during the rest of the patient's life.

Objectives

To review randomized trials of steroids for human acute spinal cord injury.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register (searched 02 Aug 2011), The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials 2011, issue 3 (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE (Ovid) 1948 to July Week 3 2011, EMBASE (Ovid) 1974 to 2011 week 17, ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED) 1970 to Aug 2011, ISI Web of Science: Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐ Science (CPCI‐S) 1990 to Aug 2011 and PubMed [www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez/] (searched 04 Aug 2011) for records added to PubMed in the last 90 days). Files of the National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (NASCIS) were reviewed (NASCIS was founded in 1977 and has tracked trials in this area since that date). We also searched the reference lists of relevant studies and previously published reviews.

Selection criteria

All randomized controlled trials of steroid treatment for acute spinal cord injury in any language.

Data collection and analysis

One review author extracted data from trial reports. Japanese and French studies were found through NASCIS and additional data (e.g. SDs) were obtained from the original study authors.

Main results

Eight trials are included in this review, seven used methylprednisolone. Methylprednisolone sodium succinate has been shown to improve neurologic outcome up to one year post‐injury if administered within eight hours of injury and in a dose regimen of: bolus 30mg/kg over 15 minutes, with maintenance infusion of 5.4 mg/kg per hour infused for 23 hours. The initial North American trial results were replicated in a Japanese trial but not in the one from France. Data was obtained from the latter studies to permit appropriate meta‐analysis of all three trials. This indicated significant recovery in motor function after methylprednisolone therapy, when administration commenced within eight hours of injury. A more recent trial indicates that, if methylprednisolone therapy is given for an additional 24 hours (a total of 48 hours), additional improvement in motor neurologic function and functional status are observed. This is particularly observed if treatment cannot be started until between three to eight hours after injury. The same methylprednisolone therapy has been found effective in whiplash injuries. A modified regimen was found to improve recovery after surgery for lumbar disc disease. The risk of bias was low in the largest methyprednisolone trials. Overall, there was no evidence of significantly increased complications or mortality from the 23 or 48 hour therapy.

Authors' conclusions

High‐dose methylprednisolone steroid therapy is the only pharmacologic therapy shown to have efficacy in a phase three randomized trial when administered within eight hours of injury. One trial indicates additional benefit by extending the maintenance dose from 24 to 48 hours, if start of treatment must be delayed to between three and eight hours after injury. There is an urgent need for more randomized trials of pharmacologic therapy for acute spinal cord injury.

Plain language summary

Steroids for acute spinal cord injury

Every year, about 40 million people worldwide suffer a spinal cord injury. Most of them are young men. The results are often devastating. Various drugs have been given to patients in attempts to reduce the extent of permanent paralysis. Steroids have probably been used more for this purpose than any other type of drug. The review looked for studies that examined the effectiveness of this treatment in improving movement and reducing the death rate. Nearly all the research, seven trials, has involved just one steroid, methylprednisolone. The results show that treatment with this steroid does improve movement but it must start soon after the injury has happened, within no more than eight hours. It should be continued for 24 to 48 hours. Different dose rates of the drug have been given and the so‐called high‐dose rate is the most effective. The treatment does not, however, give back the patient a normal amount of movement and more research is necessary with steroids, possibly combining them with other drugs.

Background

It is estimated that acute spinal cord injury affects some 40 per million people each year (Bracken 1981), although estimates of incidence may vary considerably between countries. In all countries this is an injury affecting primarily young males, typically aged 20 to 35. (A 4:1 male to female ratio is common.) The permanent paralysis that follows leads to major disability, a shorter life expectancy and significant economic cost (Berkowitz 1992). Animal experimentation with pharmacologic therapy for acute spinal cord injury started in the late 1960s (Ducker 1969), became more common in the 1970s and led, in the USA, to the first National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (NASCIS 1) started in 1979 and completed in 1984 (Bracken 1984/85). As far as can be ascertained, this was the first randomized trial of any therapeutic modality for all aspects of spinal cord injury. The second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study followed (Bracken 1990/93). A multicenter trial from Japan (Otani 1994) and a single center trial from France (Petitjean 1998) both evaluated one of the treatment arms of NASCIS 2 which represents the first replication of a trial in this area. The third NASCIS trial has been reported (Bracken 1997/98).

Objectives

To assess the effects of steroids for acute spinal cord injury.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Patients admitted to medical centers with a diagnosis of acute spinal cord injury. This review includes trials of patients with whiplash injury and those being treated for lumbar disc disease, because of the possibility of spinal cord injury with these conditions. Different trials impose their own eligibility restrictions: for example, excluding patients of young age, with gunshot injuries or with severe co‐morbidity − particularly severe head trauma. Most acute spinal cord injury trials exclude patients with only nerve root damage or cauda equina.

Types of interventions

The review is restricted to treatment with steroids.

Types of outcome measures

Neurologic recovery of motor function at six weeks, six months and one year, mortality and incidence of infections form the primary outcome measures. Recovery of pinprick and light touch sensation or other sensory measures are not formally evaluated in this review.

Search methods for identification of studies

The search for trials was not restricted by language, date or publication status (i.e. published or unpublished).

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases;

Cochrane Injuries Group Specialised Register (searched 02 Aug 2011);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials 2011, issue 3 (The Cochrane Library);

MEDLINE (Ovid) 1948 to July Week 3 2011;

EMBASE (Ovid)1974 to 2011 week 17;

ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED) 1970 to Aug 2011;

ISI Web of Science: Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐ Science (CPCI‐S) 1990 to Aug 2011;

PubMed [www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez/] (searched 04 Aug 2011: records added to PubMed in the last 90 days).

The full search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all included studies and previously published relevant reviews. We contacted trial authors in the field for information on any further studies they may be aware of, whether published, unpublished or ongoing. The National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (NASCIS) was also consulted for relevant trials, the organization was founded in 1977 and has tracked trials in this area to the present date.

Data collection and analysis

The Injuries Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator ran the searches. Search results were then transferred to the author who assessed them for eligibility and extracted data where appropriate.

The quality of trials was assessed using methodology developed by the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group. This considers whether the intervention was blinded, whether people evaluating outcome are blinded, how many patients were followed up and the quality of the randomization process. More details can be found in Sinclair 1992.

Mortality and more prevalent clinical sequelae have been reported for each trial in the present review. The different treatment arms under study, as well as variation in the definition of sequelae, preclude any analysis across different trials, except for a comparison of 180‐day mortality in the two trials using very‐high‐dose methylprednisolone.

In the French trial (Petitjean 1998), additional information provided by the trial author has permitted calculation of bilateral neurologic improvement scores for motor function, and pinprick and touch sensation at one year. Standard deviations for the change scores were imputed using the method described in the Cochrane Handbook 3.02 (1997, pp 213‐7) (Follmann 1992). Additional information has also been obtained for the Japanese trial (Otani 1994) to permit calculation of motor function improvement, data from the right side are used. Data from the NASCIS trials (Bracken 1984/85; Bracken 1990/93; Bracken 1997/98) uses neurologic improvement scores from the right side of the body, which is also adjusted for each patient's baseline neurologic function, and so is identical to the change scores reported in the original publications. In the NASCIS trials, when right‐side data was unavailable (due to casts or amputation) the left‐side score for that data point was substituted. The standard deviations for the subgroup analyses were derived from the total change score for the same parameter at the same follow‐up period.

The weighted mean difference of neurologic improvement scores was computed with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For mortality and morbidity, the relative risk (RR) and 95% CIs were computed. A fixed‐effect model was assumed. The heterogeneity test was examined to assist in decisions whether or not to produce typical estimates of effect.

Results

Description of studies

All trials were randomized double‐blind placebo or active drug controlled trials, except Otani 1994 and Petitjean 1998, which used a randomized control group of patients who did not receive methylprednisolone.

The NASCIS and Japanese trials used an improvement score reflecting neurologic status at follow‐up, as changed from the same status measured in the emergency department. The French trial used the final bilateral total ASIA score which is very similar to NASCIS scoring (which has one additional segment) but did not compute a change score. The primary parameters were motor function and pinprick and light touch sensation. This review focuses on motor recovery scores. In the NASCIS 3 trial the functional independence measure (FIM) was also evaluated. Morbidity and mortality were examined in most trials. NASCIS used data from the right side of the body to evaluate neurologic outcomes in all trials and this review used right side data from Otani 1994 for comparison. The trial of whiplash injury used measures of disability, sick days and a sick‐leave profile. The trial of lumbar disc disease measured relief of back and radicular pain and length of hospital stay.

A small trial by Matsumoto 2001 only assessed complications after methylprednisolone therapy and no efficacy data were produced.

Methlyprednisolone sodium succinate (MPSS) is the most widely studied therapy and formed at least one arm in all three NASCIS studies. It is the only therapy to have been replicated in more than one trial. All trials have imposed some therapeutic window between injury and starting administration of treatment. This window has been shortened to initiating therapy within eight hours in the more recent trials, as evidence has accumulated that pharmacologic therapies appear to require rapid administration if they are to be effective.

Trials are described in more detail in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Six studies generated the randomisation sequence adequately and were at low risk of bias; in two studies the method for generating the randomisation sequence was unclear because it was not described.

Allocation

Six studies had adequate concealment of the randomisation sequence and are at low risk of bias; in two studies it was unclear if the allocation was concealed.

Blinding

Five studies had adequate performance and detection blinding but three were at high risk due to being unblinded.

Incomplete outcome data

Six studies were at low risk of bias and two were unclear.

Selective reporting

Four studies had adequate reporting and four were unclear.

Other potential sources of bias

Three studies had low risk of other reporting biases and four were unclear.

Effects of interventions

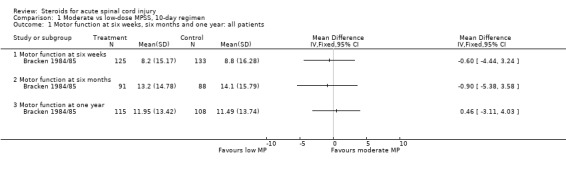

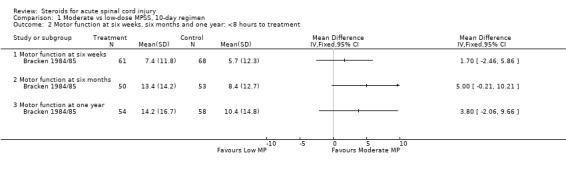

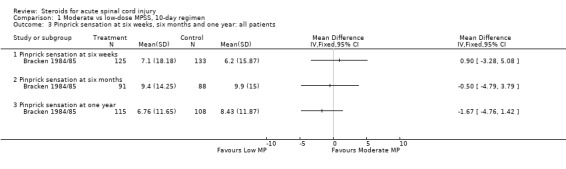

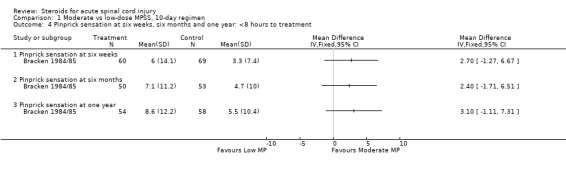

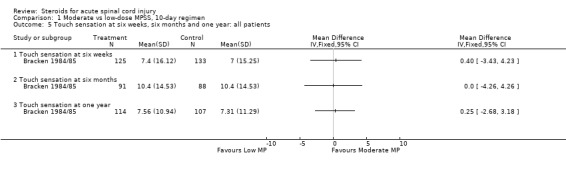

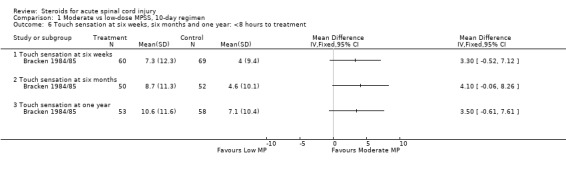

Moderate versus low‐dose methylprednisolone, 10‐day regimen (Comparison 01) One trial considered this therapeutic regimen (Bracken 1984/85). When the overall results for this trial are considered, there is no difference in the neurologic outcome scores at six weeks, six months or one year (Outcomes 01, 03, 05). Because of subsequent interest in the eight hour therapeutic window for commencing therapy, an ex‐post‐facto analysis of patients who initiated therapy within this time window is examined in this review (Outcomes 02, 04 ,06). There is a trend for patients treated with the high‐dose regimen to recover more than those on the low‐dose regimen at all three follow‐up periods and on all three neurologic parameters. None of these changes reached the nominal P < 0.05 level of statistical significance.

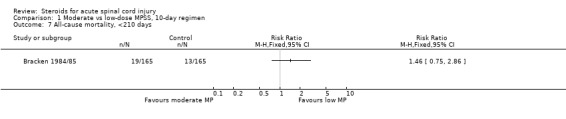

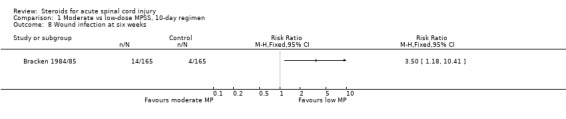

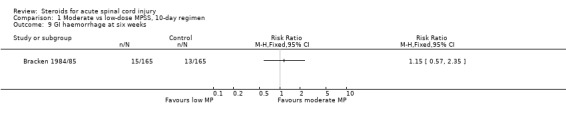

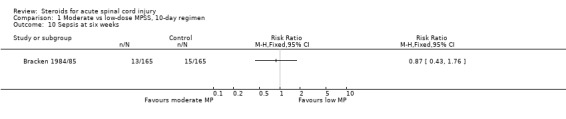

All‐cause mortality, wound infection, GI hemorrhage and sepsis were examined. Only wound infection was elevated in the high‐dose regimen (RR = 3.50, 95% CI 1.18 to 10.41) (Outcomes 07 to 10).

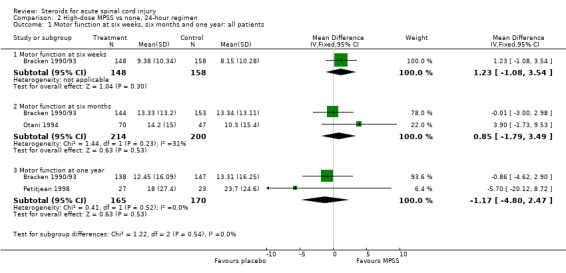

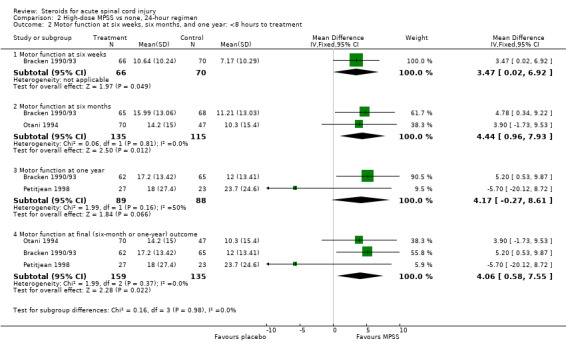

High‐dose methylprednisolone versus placebo or none, 24‐hour regimen (Comparison 02) Three trials are examined for this comparison (Bracken 1990/93, Otani 1994, Petitjean 1998). When the overall results are considered for motor function (Outcome 01) there is no effect of methylprednisolone. For the NASCIS 2 trial (Bracken 1990/93) an a‐priori hypothesis was proposed to examine patients treated early versus late. The eight hour window was established based on it being close to the median time to treatment. The other two trials restricted patient eligibility to entry within eight hours of injury. When the analysis is restricted to patients treated within the eight hour window (Outcome 02), high‐dose methylprednisolone resulted in greater motor function recovery at six weeks, six months and the final outcome (which differed among the trials as being 6 months or one year) (WMD = 4.06, 95% CI 0.58 to 7.55).

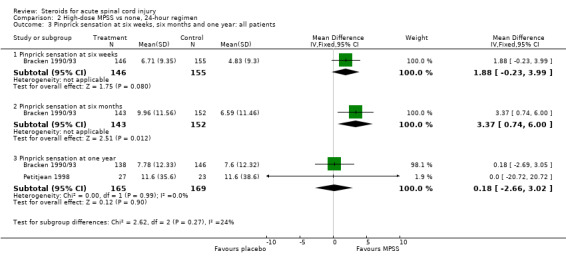

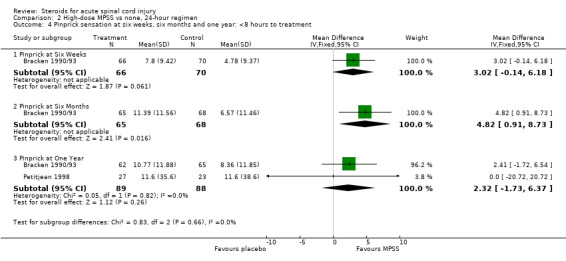

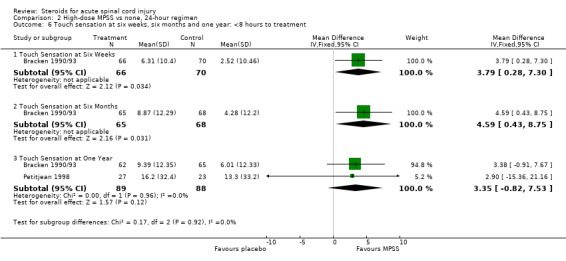

In one trial, pinprick sensation was significantly improved in all patients at six months (WMD = 3.37, 95% CI 0.74 to 6.00) but not at one year (Outcome 03). Among patients treated within eight hours these differences were enhanced at six months but were not different at one year (Outcome 04). Light touch sensation showed a similar pattern of results as pinprick (Outcomes 05 and 06).

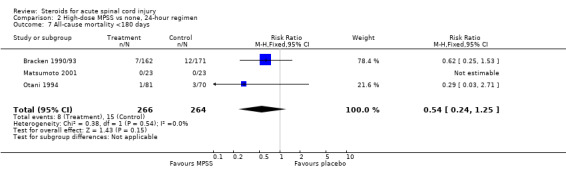

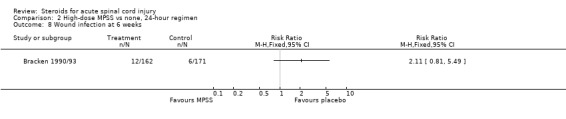

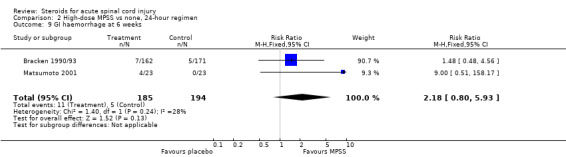

All cause mortality (3 trials), wound infection (1 trial) and GI hemorrhage (2 trials) did not differ between the two comparison groups (Outcomes 07 to 09).

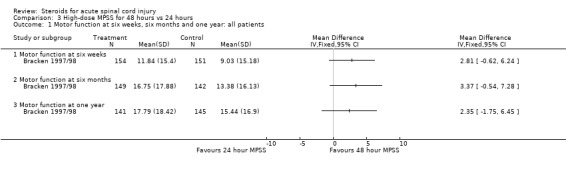

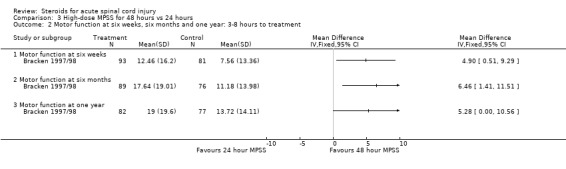

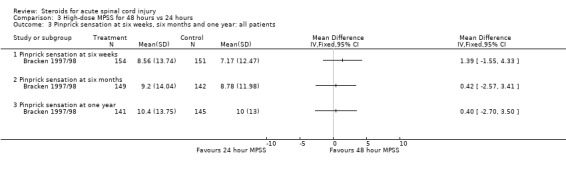

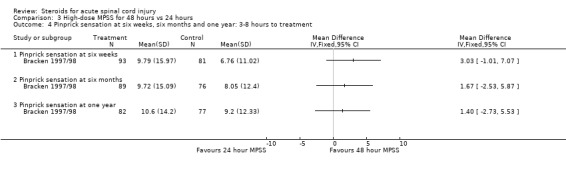

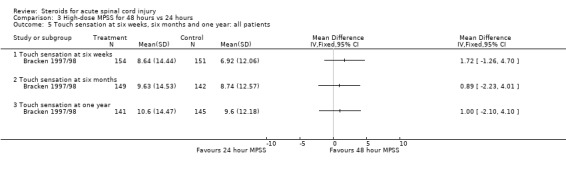

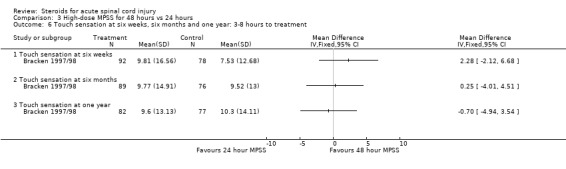

High‐dose methylprednisolone for 48 versus 24 hours (Comparison 03) One trial contributed to this analysis (Bracken 1997/98). There was a trend for greater motor function improvement in the 48‐hour treated patients (Outcome 01) but at none of the follow‐up periods did these differences reach statistical significance. In this trial, an a priori hypothesis proposed to examine patients initiating therapy early versus late within the overall eight hour window of eligibility. The median of three hours was selected for a cut‐off point. Patients treated within three hours after injury did not differ in their recovery from 24 or 48‐hour methylprednisolone (Bracken 1997/98). Patients treated within 3 to 8 hours improved more motor function if treated with 48‐hour methylprednisolone (Outcome 02). No meaningful differences were observed for pinprick or touch sensation in the full analysis or in those treated at 3 to 8 hours at any of the follow‐up periods (Outcomes 03 to 06).

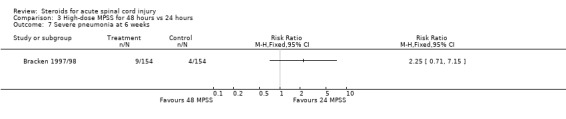

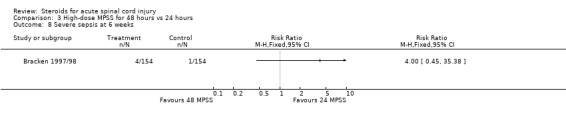

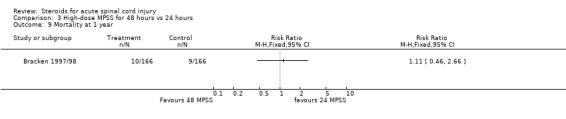

Severe pneumonia and severe sepsis tended to be elevated in the 48‐hour treated patients but overall mortality at one year was not (Outcomes 07 to 09).

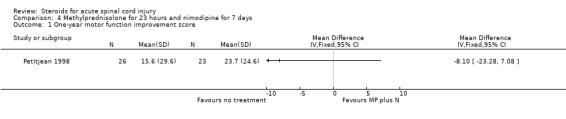

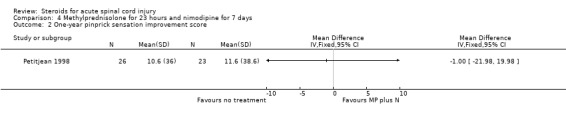

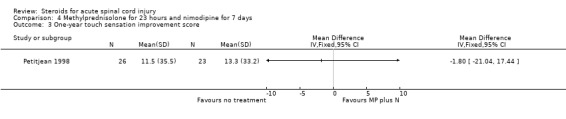

High‐dose methylprednisolone for 23 hours versus nimodipine for seven days (Comparison 04) One trial contributed to this analysis (Petitjean 1998). No meaningful observations could be made from these comparisons because of very high variability in the data (Outcomes 01 to 03).

Other trials In the whiplash trial (Pettersson 1998), the identical regimen of methylprednisolone to that administered in NASCIS 2 was found to result in fewer disabling symptoms (P = 0.047), fewer sick days (P = 0.01) and a healthier sick leave profile (P = 0.003) at six months post injury.

For patients treated with methylprednisolone at the time of their discectomy for lumbar disc disease, their hospital stay was significantly shorter than patients not so treated (1.4 versus 4.0 days, P = 0.0004) (Glasser 1993).

Discussion

Trials of steroid therapy for acute spinal cord injury are rare. Only eight trials were found in the literature, seven of methylprednisolone. Clearly, there is a critical need for more randomized trials to evaluate many aspects of management for this injury. The relatively low incidence of spinal cord injury may explain why trials have lagged behind many other clinical specialties but the fact that two large multi‐center trials were concurrently underway in the US during the early 1990s indicates that there has been, and will continue to be, opportunities for more trials in this area.

The first NASCIS trial (Bracken 1984/85) did not find any beneficial effect of methylprednisolone given at 1g per day for 10 days. In analyses completed for this review, which stratify the patients according to those treated within 8 hours, there is some modest evidence of potential benefit in patients treated early.

The second NASCIS trial (Bracken 1990/93) found significantly increased neurologic recovery among patients treated with very‐high‐dose methylprednisolone within eight hours of injury. This treatment has become a standard therapy in many countries. As shown by this review, additional trials (Otani 1994; Petitjean 1998) have only slightly moderated the conclusion that this regimen offers some neurologic benefit to some patients. This treatment regimen does not appear to be related to any significant increased risk of medical complication. A third NASCIS trial (Bracken 1997/98) contrasted the NASCIS 2 treatment with methylprednisolone with an extended 48‐hour regimen which was shown to further improve motor function and functional outcomes (not examined in this review), particularly if initiation of therapy could not start until three to eight hours post injury. The pharmacologic rationale for the effect of methylprednisolone and a review of the animal literature has been provided by Hall 1992.

The additional trials of Glasser 1993 and Pettersson 1998 provide some supportive evidence for a role for methylprednisolone in recovery from acute spinal cord injury, although it is likely that much of the recovery in those trials was due to nerve root function rather than spinal cord improvement per se.

A systematic review of almost 2500 patients in 51 trials of the use of high‐dose methylprednisolone versus placebo or nothing by Sauerland 2000 provides further reassurance of safety. High‐dose methylprednisolone was defined as any intravenous dose exceeding 15 mg/kg or 1g MPSS given as a single or repeated dose within a maximum of three days and discontinued afterwards. The trials included trauma and elective spine surgery. No evidence was found for any increased risk of gastro‐intestinal bleeding (RD = 0.3%, P = 0.4), wound complication (RD = 1%, P = 0.2), pulmonary complications (for which MPSS was significantly protective RD = ‐3.5%, P = 0.003) or death (also moderately protective RD = ‐0.9%, P = 0.10). No evidence of harm was found when spine surgery alone was considered. These results are discussed more in Bracken 2001. In another study long‐term follow‐up of avascular necrosis after high‐dose MPSS for acute spinal cord injury, diagnosed by MRI of femoral and humeral heads assessed blind to therapy, failed to find any increased risk (Wing 1998).

Only some of the analyses in this review have been adjusted for any potential imbalances in baseline factors observed at randomization, even though some imbalances were reported. However, none of the results reported in this review for any of the individual trials appear to be inconsistent with the data reported in the original trial reports.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Methylprednisolone sodium succinate has been shown to enhance sustained neurologic recovery in a phase three randomized trial, and to have been replicated in a second trial. Therapy must be started within eight hours of injury using an initial bolus of 30 mg/kg by IV for 15 minutes followed 45 minutes later by a continuous infusion of 5.4mg/kg/hour for 24 hours. Further improvement in motor function recovery has been shown to occur when the maintenance therapy is extended for 48 hours. This is particularly evident when the initial bolus dose could only be administered three to eight hours after injury.

Implications for research.

Methylprednisolone treatment improves neurologic recovery but is unlikely to bring a return to normal function unless there is minimal initial deficit. More research is needed to examine whether different MPSS protocols would achieve even more recovery. It is likely that future trials will be able to examine concurrent pharmacologic therapies (sometimes called drug cocktails) or sequential therapies which operate on different aspects of the secondary injury processes ranging from early neuron protection to nerve regeneration in the chronic patient.

Feedback

Steroids for acute spinal cord injury

Summary

Please note that this comment, and the subsequent reply from the reviewer, was originally about the first version of this review (Pharmacology in acute spinal cord injury). The review has subsequently been revised to the present version (Steroids for acute spinal cord injury).

Summary of comments and criticisms.

The author of the criticism refers to the papers by Coleman et al 2000, and Hurlbert RJ which disagree with the conclusions of this review. He would like the following points addressed (each comment has a number with a corresponding response from the reviewers in the reply section below):

1. "NASCIS II" implied that there was a positive result in the primary efficacy analysis for the entire 487 patient sample. However, this analysis was in fact negative. A positive result was only found in a secondary analysis of a small subgroup (62 + 67 patients) splitting the sample before and after 8 hours.

2. The placebo group treated before 8 hours did poorly, not only when compared with the methylprednisolone group treated before 8 hours, but even when compared with the placebo group treated after 8 hours. Thus the positive result may have been caused by a weakness in the control group rather than any strength of methylprednisolone.

3. Most of the combined improvement from all patients in the subgroup (62 + 67 patients) was due to differences in the changes in the patients with incomplete lesions. This comparison involved only 22 patients in the methylprednisolone group and 24 patients in the placebo group.

4. The NASCIS II and III reports embody specific choices of statistical methods that have strongly shaped the reporting of results but have not been adequately challenged or even explained.

5. In NASCIS III, a randomization imbalance occurred that allocated a disproportionate number of patients with no motor deficit (and therefore no chance for recovery) to the lower dose control group. When this imbalance is controlled for, much of the superiority of the higher dose group seems to disappear.

6. Perhaps one half of the NASCIS III sample may have had at most a minor deficit. Thus, we do not know whether the results of these studies reflect the severely injured population to which they have been applied.

7. The numbers, tables, and figures in the published reports are scant and are inconsistently defined, making it impossible even for professional statisticians to duplicate the analyses, to guess the effect of changes in assumptions, or to supply the missing parts of the picture.

8. Nonetheless, even 9 years after NASCIS II, the primary data have not been made public.

9. The reporting of the NASCIS studies has fallen short of the guidelines of the ICH/FDA, and of the Evidence‐based Medicine Group.

10. Despite the lucrative "off label" markets for methylprednisolone in Spinal Cord Injury, no Food and Drug Association indication has been obtained, and there has been no public process of validation.

11. These shortcomings have denied physicians the chance to use confidently a drug that many were enthusiastic about and have left them in an intolerably ambiguous position in their therapeutic choices, in their legal exposure, and in their ability to perform further research to help their patients.

12. Animal studies of the effect of Methylprednisolone and the human studies are different, and little work has been done to relate them explicitly. It is simply not true that the NASCIS studies either strongly confirm or are strongly confirmed by the animal studies.

In conclusion the use of methylprednisolone administration in the treatment of acute SCI is not proven as a standard of care, nor can it be considered a recommended treatment. Evidence of the drug's efficacy and impact is weak and may only represent random events. In the strictest sense, 24‐hour administration of methylprednisolone must still be considered experimental for use in clinical SCI. Forty‐eight‐hour therapy is not recommended. These conclusions are important to consider in the design of future trials and in the medico‐legal arena.

References: Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, Holford TR, Young W, Baskin DS et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal‐cord injury. Results of the Second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. N Engl J Med. 1990 May 17;322(20):1405‐11.

Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, et al Administration of Methylprednisolone for 24 or 48 hours or Tirilazad Mesylate for 48 hours in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Results of the third national acute spinal cord injury randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1997;277:1597‐1604.

Coleman WP, Benzel D, Cahill DW, Ducker T, Geisler F, Green B et al. A critical appraisal of the reporting of the National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Studies (II and III) of methylprednisolone in acute spinal cord injury. J Spinal Disord. 2000 Jun;13(3):185‐99.

Hurlbert RJ. Methylprednisolone for acute spinal cord injury: an inappropriate standard of care. J Neurosurg 2000 Jul;93(1 Suppl):1‐7.

Reply

Detailed responses to the comments reflected in the Criticism have been published elsewhere (1,2) and should be consulted by the interested reader.

1. The primary NASCIS 2 report (3) clearly stated that no benefit of methylprednisolone (MP) was observed in the total study group. In the a priori analysis of patients treated relatively quickly after injury (within 8 hours which was the modal time from injury to initiating therapy, and the only dichotomy analysed) patients treated with MP recovered significantly better than placebo treated patients. Examination of drug effect as a function of time to injury was a major hypothesis in the design of both NASCIS 2 and 3.

2. The comparison of placebo treated patients before versus after eight hours is not a randomized comparison and there is no reason to expect that these patients would be similar. The time taken to initiate therapy was largely a function of how quickly patients were admitted to hospital and there are many reasons why this may vary by severity of injury. The only valid comparisons for analysis are the ones reported, ie. comparisons of treatment (which was randomized) within the early and late time periods.

3. Statistically significant improvement in MP treated patients was observed and reported in both neurologically complete and incomplete patients as assessed in the emergency department.

4. The statistical procedure used to analyze NASCIS 2 and 3 was primarily analysis of covariance which is a standard form of analysis for randomized controlled trials. This methodology is described in any standard text.

5. In NASCIS 3 an imbalance at randomization was reported (4, table 2) which allocated somewhat more severely injured patients to Tiralazad mesylate. There was also a non‐significant baseline difference in the two MP groups. Baseline neurological function was controlled in all statistical analyses and, as expected, the multivariate analysis of the two MP groups showed reduced improvement differences when the baseline differences were taken into account. These "controlled" analyses form the primary published results.

6. The NASCIS 3 report (4) shows severity of injury of all patients in the trial. Overall, for motor function 35.2% were quadriplegic; 31.0% paraplegic; 13.4% quadriparetic; 4.0% paraparetic and 14.4% normal although all normal motor responses had some sensory loss. After accounting for trial exclusion criteria (gunshot wounds, etc), the study population reflects the pattern of spinal injury seen in hospital emergency departments. Both NASCIS 2 and 3 showed efficacy of MP in severely injured patients, defined as having complete neurological loss below the level of injury.

7. Professional biostatisticians are among the NASCIS investigators and authors, were part of the review process at NEJM and JAMA, and sat on NIH panels overseeing the trials. Standard statistical procedures were used (item 4) and the neurological and functional definitions used are standard criteria promulgated by the American Spinal Injury Association, endorsed by the International Medical Society of Paraplegia, and widely adopted for clinical and research purposes around the world.

8. NASCIS data sets are available to recognized authoritative agencies and groups who submit a proposal describing their intended use of the data and demonstrate that they have the technical, biostatistical and clinical expertise to understand and analyse these complex data sets in an unbiased manner. Since NASCIS investigators continue to be funded by NIH for analyses of NASCIS 2 and 3, there is concern that analyses not be done which pre‐empt publication of the same analyses by the initial investigators.

9. The ICH/FDA guidelines were published in 1996 but they enshrined principles and practices that have been evolving for many years. The NASCIS reports, even early ones, clearly meet both the spirit and intent of the recommendations.

10. The NASCIS studies are funded by the United States National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke. However, responsibility for seeking an indication for use in spinal injury from national drug regulatory agencies rests with the pharmaceutical company manufacturing the compound, Pharmacia‐Upjohn Inc. NASCIS data is available for purposes of seeking regulatory approval of MP in any country. To the best of our knowledge, FDA approval has not been sought but an indication has been sought and obtained in a large number of other countries.

11. Physicians in many countries confidently use MP for spinal cord injury and have done so since 1990. The NASCIS 2 data supporting use has not changed since 1990. Nothing from the NASCIS studies prevents further research in spinal cord injury just as therapeutic discoveries in other areas of medicine do not stop research either. If MP has no benefit, comparing therapies to it should not pose a problem in demonstrating a new drug's superiority. If MP does confer benefit, comparison with it is necessary.

12. Animal studies serve two roles in developing scientific evidence. They prompt testing of therapies in humans after successful trial in animals and they provide biologic plausibility to the human evidence once it has been gathered. The weight of evidence from cat and other models using MP, which led to the initial trials, is strongly supportive of the role of MP (5). New experimental studies of MP in enhancing neuro‐regeneration and playing other beneficial roles at the molecular level (6‐8) provide further additional evidence of plausibility to support the human trials. This is an extraordinarily difficult but critically important area of human research and it is cause for concern that more trials of MP and other therapies are not being conducted. Currently, primary evidence of efficacy and safety from three trials, and secondary evidence from trials of related clinical conditions and animal studies, as reported in this Cochrane Review, support use of MP in the management of spinal cord injury. There is no other pharmacologic therapy with sufficient evidence to support use at this time.

References

1. Bracken MB, Aldrich EF, Herr DL et al. Clinical measurement, statistical analysis and risk benefit: controversies from trials of spinal injury. J Trauma 2000; 48:558‐61.

2. Bracken MB. Methylprednisolone and spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg Spine 2000; 93:175‐8.

3. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF et al. A randomized controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury: results of the second national acute spinal cord injury study. New Engl J Med 1990; 322:1405‐11.

4. Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR et al. Methylprednisolone administered for 24 or 48 hours, or 48 hour tirilazad mesylate, in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury; results of the third national acute spinal cord injury randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1997; 277:1597‐1604.

5. Hall ED. The neuroprotective pharmacology of methylprednisolone. J Neurosurg 1992; 76:13‐22.

6. Oudega M, Vargas CA, Weber AB et al. Long‐term effects of methylprednisolone following transection of adult rat spinal cord. Eur J Neurosci 1999; 11:2453‐64.

7. Banik NL, Matzelle D, Terry E et al. A new mechanism of methylprednisolone and other corticoids action demonstrated in vitro: inhibition of a proteinase (calpain) prevents myelin and cytoskeletal protein degradation. Brain Res 1997; 748:205‐10.

8. Xu J, Fan G, Chen S et al. Methylprednisolone inhibition of TNF‐alpha expression and NF‐KB activation after spinal cord injury.

Contributors

Author of comment: Peter Mikkelsen Author of response: Michael Bracken

Steroids for acute spinal cord injury, 26 July 2018

Summary

Comment from Dr. Paul Hine: "Criticisms of the conduct of this review have appeared in the BMJ (BMJ 2013;346:f3830) and in greater depth by other authors (Evaniew, N., & Dvorak, M. (2016). Cochrane in CORR®: Steroids for Acute Spinal Cord Injury (Review). Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 474(1), 19–24. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11999‐015‐4601‐6) In short, the concerns raised are that Michael Bracken was allowed to serve as sole reviewer despite having declared financial and non‐financial conflicts of interest. This review should either be updated to respond to these high‐profile criticisms, or withdrawn. At present, its continued publication in the library may undermine the reputation of Cochrane." Cochrane comments system conflict of interest request: Do you have any affiliation with or involvement in any organisation with a financial interest in the subject matter of your comment? Conflict of interest declaration from Dr. Hine: "I have a non‐financial conflict of interest in that I am concerned about under‐reporting of non‐financial conflicts of interest."

Reply

This review was requested by the Cochrane Collaboration at a time when single author reviews were deemed acceptable. Several subsequent updates found no additional randomized trials had been conducted. The most recent systematic review and clinical guideline on this topic (1), which should be preferentially consulted, draws essentially the same conclusion as the Cochrane review: that the risk of bias is low in the largest trials and that 24 hour treatment of acute spinal cord injury with MPSS, if started within 8 hours of injury, is a treatment option. 1. A Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Spinal Cord Injury: Recommendations on the Use of Methylprednisolone Sodium Succinate. Fehlings MG, Wilson JR, Tetreault LA, Aarabi B, Anderson P, Arnold PM, Brodke DS, Burns AS, Chiba K, Dettori JR, Furlan JC, Hawryluk G, Holly LT, Howley S, Jeji T, Kalsi‐Ryan S, Kotter M, Kurpad S, Kwon BK, Marino RJ, Martin AR, Massicotte E, Merli G, Middleton JW, Nakashima H, Nagoshi N, Palmieri K, Skelly AC, Singh A, Tsai EC, Vaccaro A, Yee A, Harrop JS. Global Spine J. 2017 Sep;7(3 Suppl):203S‐211S. doi: 10.1177/2192568217703085. Epub 2017 Sep 5. PMID: 29164025

Contributors

Author of the comment: Dr. Paul Hine, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK Author of the response: Dr. Michael Bracken, Yale University, USA

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 September 2018 | Feedback has been incorporated | A response to feedback is included in the Feedback 2 section. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1998 Review first published: Issue 1, 1998

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 August 2012 | Review declared as stable | There are no ongoing RCTs in humans, and no new studies have been included in the review since 2004. The search will be updated in 2015. |

| 7 December 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The search was updated on 2nd August 2011. 531 (after de‐duplication) articles were retrieved. Studies were selected for further examination by screening titles and (in about half of the citations) the abstract. There were no new studies meeting the review's inclusion criteria. The results and conclusions of the review are unchanged. |

| 6 December 2011 | New search has been performed | The search for studies has been updated to 2 August 2011. |

| 11 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 1 September 2007 | New search has been performed | Searches were last updated in September 2007. An updated search on MEDLINE and CENTRAL was conducted in October 2004. No new studies for inclusion were found. One further excluded study (Yokota 1995) was identified. |

Notes

The review will be updated in 2019 with a second author, and will be reported according to Cochrane's current MECIR standards.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Peter Smith for his help with translating the Petitjean paper and Frances Bunn for technical assistance. Thanks to Dr Petitjean for providing additional information about the French trial.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

Cochrane Injuries Group Specialised Register (searched 02 August 2011) #1 (“spinal cord” or spinal‐cord* or spine or spinal) and (Broken or break* or fractur* or wound* or trauma* or injur* or damag* or lesion* or contusion* or laceration* or trauma or ischemi*)) #2 paraplegi* or paraparesis or qadriplegi* or quadriparesi* or tetraplegi* or tetraplagi* or tetraparesis #3 central cord injury syndrome #4 (myelopathy and (traumatic or post‐traumatic)) #5 (steroid* or glucocorticoid* or prednisolone* or betamethasone* or cortisone* or dexamethasone* or hydrocortisone* or methylprednisolone* or prednisone* or triamcinolone* or corticosteroid*) #6 #1 and #2 Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials 2011, issue 3 (The Cochrane Library) #1 paraplegi* or paraparesis #2 qadriplegi* or quadriparesi* #3 tetraplegi* or tetraplagi* or tetraparesis #4 (spine or spinal) near3 (Broken or break* or fracture* or wound* or trauma* or injur* or damag*) #5 (spinal cord) near3 (contusion or laceration or trauma or injur* or ischemi*) #6 (central cord injury syndrome) #7 (myelopathy near3 (traumatic or post‐traumatic)) #8 MeSH descriptor Central Cord Syndrome explode all trees #9 MeSH descriptor Spinal Cord Ischemia explode all trees #10 MeSH descriptor Spinal Fractures explode all trees #11 MeSH descriptor Spinal Cord Injuries explode all trees #12 MeSH descriptor Paraplegia explode all trees #13 MeSH descriptor Quadriplegia explode all trees #14 MeSH descriptor Spinal Cord explode all trees with qualifiers: SU,TH #15 MeSH descriptor Cervical Vertebrae explode all trees with qualifier: IN #16 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15) #17 MeSH descriptor Glucocorticoids explode all trees #18 MeSH descriptor Steroids explode all trees #19 steroid* or glucocorticoid* or prednisolone* or betamethasone* or cortisone* or dexamethasone* or hydrocortisone* or methylprednisolone* or prednisone* or triamcinolone* or corticosteroid* #20 (#17 OR #18 OR #19) #21 (#16 AND #20) MEDLINE (Ovid SP) 1948 to July Week 3 2011 1. exp Spinal Cord/su, th [Surgery, Therapy] 2. exp Spinal Cord Injuries/ 3. exp Spinal Cord Ischemia/ 4. exp Central Cord Syndrome/ 5. (myelopathy adj3 (traumatic or post‐traumatic)).ab,ti. 6. ((spine or spinal) adj3 (fracture* or wound* or trauma* or injur* or damag*)).ab,ti. 7. (spinal cord adj3 (contusion or laceration or transaction or trauma or ischemia)).ab,ti. 8. central cord injury syndrome.ab,ti. 9. central spinal cord syndrome.ab,ti. 10. exp Cervical Vertebrae/in [Injuries] 11. SCI.ab,ti. 12. exp Paraplegia/ 13. exp Quadriplegia/ 14. (paraplegi* or quadriplegi* or tetraplegi*).ab,ti. 15. or/1‐14 16. exp Glucocorticoids/ 17. exp Steroids/ 18. (steroid* or glucocorticoid* or prednisolone* or betamethasone* or cortisone* or dexamethasone* or hydrocortisone* or methylprednisolone* or prednisone* or triamcinolone* or corticosteroid*).ab,ti. 19. 16 or 17 or 18 20. 15 and 19 21. randomi?ed.ab,ti. 22. randomized controlled trial.pt. 23. controlled clinical trial.pt. 24. placebo.ab. 25. clinical trials as topic.sh. 26. randomly.ab. 27. trial.ti. 28. 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 29. (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 30. 28 not 29 31. 20 and 30 EMBASE 1974 to 2011 August (week 17) 1.exp Spinal Cord/su, th [Surgery, Therapy] 2.exp Spinal Cord Injury/ 3.exp Spinal Cord Ischemia/ 4.exp Central Cord Syndrome/ 5.(myelopathy adj3 (traumatic or post‐traumatic)).ab,ti. 6.((spine or spinal) adj3 (fracture* or wound* or trauma* or injur* or damag*)).ab,ti. 7.(spinal cord adj3 (contusion or laceration or transaction or trauma or ischemia)).ab,ti. 8.central cord injury syndrome.ab,ti. 9.central spinal cord syndrome.ab,ti. 10.exp Paraplegia/ 11.exp Quadriplegia/ 12.(paraplegi* or quadriplegi* or tertraplegi*).ab,ti. 13.SCI.ab,ti. 14.or/1‐13 15.exp Glucocorticoid/ 16.exp Steroid/ 17.(steroid* or glucocorticoid* or prednisolone* or betamethasone* or cortisone* or dexamethasone* or hydrocortisone* or methylprednisolone* or prednisone* or triamcinolone* or corticosteroid*).ab,ti. 18.or/15‐17 19.14 and 18 20.exp Randomized Controlled Trial/ 21.exp controlled clinical trial/ 22.randomi?ed.ab,ti. 23.placebo.ab. 24.*Clinical Trial/ 25.randomly.ab. 26.trial.ti. 27.20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 28.exp animal/ not (exp human/ and exp animal/) 29.27 not 28 30.19 and 29 ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED) 1970 to Aug 2011 ISI Web of Science: Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐ Science (CPCI‐S) 1990 to Aug 2011 #1 Topic=((“spinal cord” or spinal‐cord* or spine or spinal) NEAR (Broken or break* or fractur* or wound* or trauma* or injur* or damag* or lesion* or contusion* or laceration* or trauma or ischemi*)) OR Topic=(paraplegi* or paraparesis or qadriplegi* or quadriparesi* or tetraplegi* or tetraplagi* or tetraparesis) OR Topic=("central cord injury syndrome") OR Topic=((spine or spinal) NEAR (myelopathy NEAR (traumatic or post‐traumatic))) #2 Topic=((steroid* or glucocorticoid* or prednisolone* or betamethasone* or cortisone* or dexamethasone* or hydrocortisone* or methylprednisolone* or prednisone* or triamcinolone* or corticosteroid*)) #3 Topic=((clinical OR control* OR placebo OR random*) NEAR (trial* or group* or study or studies or placebo or controlled)) NOT Topic=(ANIMAL*) #4 #1 AND #2 AND #3 PubMed [www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez/] (searched 04 August 2011: limit: added to PubMed in the last 90 days) #1 (“spinal cord” or spinal‐cord* or spine or spinal) and (Broken or break* or fractur* or wound* or trauma* or injur* or damag* or lesion* or contusion* or laceration* or trauma or ischemi*)) #2 paraplegi* or paraparesis or qadriplegi* or quadriparesi* or tetraplegi* or tetraplagi* or tetraparesis #3 central cord injury syndrome #4 (spine or spinal) and (myelopathy and (traumatic or post‐traumatic)) #5 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 #6 (steroid* or glucocorticoid* or prednisolone* or betamethasone* or cortisone* or dexamethasone* or hydrocortisone* or methylprednisolone* or prednisone* or triamcinolone* or corticosteroid*) #7 #5 and #6 #8 ((randomized controlled trial[pt] OR controlled clinical trial[pt]) OR (randomized OR randomised OR randomly OR placebo[tiab]) OR (trial[ti]) OR ("Clinical Trials as Topic"[MeSH Major Topic])) NOT (("Animals"[Mesh]) NOT ("Humans"[Mesh] AND "Animals"[Mesh])) #9 #7 and #8

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Moderate vs low‐dose MPSS, 10‐day regimen.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Motor function at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Motor function at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Motor function at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Motor function at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Motor function at six weeks, six months and one year: <8 hours to treatment | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Motor function at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Motor function at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Motor function at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Pinprick sensation at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Pinprick sensation at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Pinprick sensation at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: <8 hours to treatment | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Pinprick sensation at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Pinprick sensation at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Pinprick sensation at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 Touch sensation at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Touch sensation at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Touch sensation at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: <8 hours to treatment | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 Touch sensation at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.2 Touch sensation at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.3 Touch sensation at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 All‐cause mortality, <210 days | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8 Wound infection at six weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9 GI haemorrhage at six weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 10 Sepsis at six weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Moderate vs low‐dose MPSS, 10‐day regimen, Outcome 1 Motor function at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Moderate vs low‐dose MPSS, 10‐day regimen, Outcome 2 Motor function at six weeks, six months and one year: <8 hours to treatment.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Moderate vs low‐dose MPSS, 10‐day regimen, Outcome 3 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Moderate vs low‐dose MPSS, 10‐day regimen, Outcome 4 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: <8 hours to treatment.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Moderate vs low‐dose MPSS, 10‐day regimen, Outcome 5 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Moderate vs low‐dose MPSS, 10‐day regimen, Outcome 6 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: <8 hours to treatment.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Moderate vs low‐dose MPSS, 10‐day regimen, Outcome 7 All‐cause mortality, <210 days.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Moderate vs low‐dose MPSS, 10‐day regimen, Outcome 8 Wound infection at six weeks.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Moderate vs low‐dose MPSS, 10‐day regimen, Outcome 9 GI haemorrhage at six weeks.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Moderate vs low‐dose MPSS, 10‐day regimen, Outcome 10 Sepsis at six weeks.

Comparison 2. High‐dose MPSS vs none, 24‐hour regimen.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Motor function at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Motor function at six weeks | 1 | 306 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.23 [‐1.08, 3.54] |

| 1.2 Motor function at six months | 2 | 414 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [‐1.79, 3.49] |

| 1.3 Motor function at one year | 2 | 335 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.17 [‐4.80, 2.47] |

| 2 Motor function at six weeks, six months, and one year: <8 hours to treatment | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Motor function at six weeks | 1 | 136 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.47 [0.02, 6.92] |

| 2.2 Motor function at six months | 2 | 250 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.44 [0.96, 7.93] |

| 2.3 Motor function at one year | 2 | 177 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.17 [‐0.27, 8.61] |

| 2.4 Motor function at final (six‐month or one‐year) outcome | 3 | 294 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.06 [0.58, 7.55] |

| 3 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Pinprick sensation at six weeks | 1 | 301 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.88 [‐0.23, 3.99] |

| 3.2 Pinprick sensation at six months | 1 | 295 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.37 [0.74, 6.00] |

| 3.3 Pinprick sensation at one year | 2 | 334 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.18 [‐2.66, 3.02] |

| 4 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: <8 hours to treatment | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Pinprick at Six Weeks | 1 | 136 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.02 [‐0.14, 6.18] |

| 4.2 Pinprick at Six Months | 1 | 133 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.82 [0.91, 8.73] |

| 4.3 Pinprick at One Year | 2 | 177 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.32 [‐1.73, 6.37] |

| 5 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: All patients | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 Touch Sensation at Six Weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Touch Sensation at Six Months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Touch Sensation at One Year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: <8 hours to treatment | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Touch Sensation at Six Weeks | 1 | 136 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.79 [0.28, 7.30] |

| 6.2 Touch Sensation at Six Months | 1 | 133 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.59 [0.43, 8.75] |

| 6.3 Touch Sensation at One Year | 2 | 177 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.35 [‐0.82, 7.53] |

| 7 All‐cause mortality <180 days | 3 | 530 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.24, 1.25] |

| 8 Wound infection at 6 weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9 GI haemorrhage at 6 weeks | 2 | 379 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.18 [0.80, 5.93] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High‐dose MPSS vs none, 24‐hour regimen, Outcome 1 Motor function at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High‐dose MPSS vs none, 24‐hour regimen, Outcome 2 Motor function at six weeks, six months, and one year: <8 hours to treatment.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High‐dose MPSS vs none, 24‐hour regimen, Outcome 3 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High‐dose MPSS vs none, 24‐hour regimen, Outcome 4 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: <8 hours to treatment.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High‐dose MPSS vs none, 24‐hour regimen, Outcome 5 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: All patients.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High‐dose MPSS vs none, 24‐hour regimen, Outcome 6 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: <8 hours to treatment.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High‐dose MPSS vs none, 24‐hour regimen, Outcome 7 All‐cause mortality <180 days.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High‐dose MPSS vs none, 24‐hour regimen, Outcome 8 Wound infection at 6 weeks.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High‐dose MPSS vs none, 24‐hour regimen, Outcome 9 GI haemorrhage at 6 weeks.

Comparison 3. High‐dose MPSS for 48 hours vs 24 hours.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Motor function at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Motor function at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Motor function at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Motor function at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Motor function at six weeks, six months and one year: 3‐8 hours to treatment | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Motor function at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Motor function at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Motor function at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Pinprick sensation at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Pinprick sensation at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Pinprick sensation at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: 3‐8 hours to treatment | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Pinprick sensation at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Pinprick sensation at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Pinprick sensation at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 Touch sensation at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Touch sensation at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Touch sensation at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: 3‐8 hours to treatment | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 Touch sensation at six weeks | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.2 Touch sensation at six months | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.3 Touch sensation at one year | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 Severe pneumonia at 6 weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8 Severe sepsis at 6 weeks | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9 Mortality at 1 year | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High‐dose MPSS for 48 hours vs 24 hours, Outcome 1 Motor function at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High‐dose MPSS for 48 hours vs 24 hours, Outcome 2 Motor function at six weeks, six months and one year: 3‐8 hours to treatment.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High‐dose MPSS for 48 hours vs 24 hours, Outcome 3 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High‐dose MPSS for 48 hours vs 24 hours, Outcome 4 Pinprick sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: 3‐8 hours to treatment.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High‐dose MPSS for 48 hours vs 24 hours, Outcome 5 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: all patients.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High‐dose MPSS for 48 hours vs 24 hours, Outcome 6 Touch sensation at six weeks, six months and one year: 3‐8 hours to treatment.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High‐dose MPSS for 48 hours vs 24 hours, Outcome 7 Severe pneumonia at 6 weeks.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High‐dose MPSS for 48 hours vs 24 hours, Outcome 8 Severe sepsis at 6 weeks.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High‐dose MPSS for 48 hours vs 24 hours, Outcome 9 Mortality at 1 year.

Comparison 4. Methylprednisolone for 23 hours and nimodipine for 7 days.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 One‐year motor function improvement score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 One‐year pinprick sensation improvement score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 One‐year touch sensation improvement score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Methylprednisolone for 23 hours and nimodipine for 7 days, Outcome 1 One‐year motor function improvement score.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Methylprednisolone for 23 hours and nimodipine for 7 days, Outcome 2 One‐year pinprick sensation improvement score.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Methylprednisolone for 23 hours and nimodipine for 7 days, Outcome 3 One‐year touch sensation improvement score.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bracken 1984/85.

| Methods | Multi‐center (n=9) double‐blind randomized trial. After ascertaining eligibility a 24‐hour telephone number called to learn which uniquely numbered drug packet (already delivered to the hospital) should be used. Each hospital given block of 6 (3 patients in each treatment arm). Double dummy technique used to mask study drugs. | |

| Participants | In all, 330 patients randomized within 48h of injury (165 to each treatment), 24 patients excluded from analysis for specified reasons (table 2). In this review morbidity and mortality use all randomized patients in denominator but conclusions remain unchanged. This review delineates those patients treated within 8h of injury. | |

| Interventions | Treatment arm 1: (n=165) Immediately after randomization a loading dose of 100 mg MPPS and 25 mg every six hours thereafter for 10 days. Treatment arm 2: (n=165) As above but 1000 mg LD and 250 mg thereafter. LD administered over 10 minutes. Maintenance doses administered using fluid administration set, either directly or through IV. |

|

| Outcomes | Neurological examinations and clinical status examined six weeks, six months and one year after injury. Neuroexam included motor function and pinprick and light touch sensation, all measured categorically and as continuous scales. All outcomes assessed blind. Clinical outcomes included: urinary tract infection, pneumonia, decubitus, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, wound infection, sepsis, arrythmia, thrombophlebitis, pulmonary embolus, paralytic ileus, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, angina pectoris and death < 14 days, 15‐28 days and at 1 year. |

|

| Notes | Historical note: This may be the first randomized controlled trial of any treatment modality for acute spinal cord injury. This trial is often referred to as NASCIS 1 (The first National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | See Methods |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | See Methods |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | patients, caregivers and statistical analysts blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients, caregivers blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 92% follow‐up at 6 weeks and 65% at 6 months, 100% survival analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Outcomes prespecified in protocol |

| Other bias | Low risk | Subgroups prespecified in protocol |

Bracken 1990/93.

| Methods | Multi‐center (n=10) double‐blind randomized trial. Three treatment arms in blocks of 9 (3 each arm) per center. Randomized by central telephone. Double‐dummy technique used to mask study drugs which were given by separate IV sites using flow rates and concentrations according to each patient's body mass. | |

| Participants | Eligible patients had a diagnosed spinal cord injury, gave consent, were randomized within 12 hours of injury, 13 years or older, and met other specified clinical and study criteria. In all 487 patients randomized to three arms and analysis followed intention‐to‐treat principle. | |

| Interventions | Treatment arm 1: (n=162) Methylprednisolone bolus of 30 mg/kg body weight followed by 5.4 mg/kg per hour for 23 hours. Treatment arm 2: (n=154) Naloxone bolus of 5.4 mg/kg of body weight followed by 4.0 mg/kg per hour for 23 hours. Treatment arm 3: (n=171) Placebo given by bolus and infusion using double‐dummy technique. | |

| Outcomes | Neurological function examined six weeks, six months and one year after injury using categorical and continuous scales to assess motor function, pin and light touch sensation. Morbidity evaluated at same times and included all outcomes studied in earlier (1984) NASCIS trial. Mortality assessed to 1 year after injury. All outcomes assessed blind. | |

| Notes | This trial is often referred to as NASCIS 2 (The second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | See Methods |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | See Methods |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients, caregivers and statistical analysts blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients and caregivers blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 98% follow‐up at 6 weeks and 96% at 6 months, 100% survival analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Outcomes prespecified in protocol |

| Other bias | Low risk | Subgroups prespecified in protocol |

Bracken 1997/98.

| Methods | Multi‐center (n=16) double‐blind randomized trial. After ascertaining eligibility a 24‐hour telephone number called to randomize. Three treatment arms in blocks of 9 (3 each arm per center). Double‐dummy techniques used to mask study drug which were given by IV using infusion rates and dose schedules according to each patient's body mass. | |

| Participants | Eligible patients had diagnosed spinal cord injury, gave consent, were randomized within 6 hours of injury to begin treatment within 8 hours, were 13 years or older, and met other specified clinical and study criteria. In all 499 patients were randomized (485 planned) to three arms and analysis used intent‐to‐treat and compliers (N=461) groups. | |

| Interventions | All patients received an IV bolus of methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg) before randomization. Patients in 24h regimen (N=166) received methylprednisolone infusion of 5.4 mg/kg/h for 24h, those in the 48h methylprednisolone group (n=167) received an infusion of 5.4 mg/kg/h for 48h, and those in a third group (n=166) received a 2.5 mg/kg bolus infusion of tirilazad mesylate every 6h for 48h. | |

| Outcomes | Motor function change between initial presentation and at 6 weeks and 6 months after injury, and functional independence measure (FIM) assessed at 6 weeks and six months and one year. Morbidity evaluated at six weeks and six months and included all outcomes assessed in earlier (1984 and 1990) NASCIS trials. Mortality assessed at six months and at one year post injury. All outcomes assessed blind. | |

| Notes | This trial is often referred to as NASCIS 3 (the third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study). Methylprednisolone is the sodium succinate preparation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | See Methods |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | See Methods |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients, caregivers and statistical analysts blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients and caregivers blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 97% follow‐up at 6 weeks and 94% at 6 months, 100% survival analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Outcomes prespecified in protocol |

| Other bias | Low risk | Subgroups prespecified in protocol |

Glasser 1993.

| Methods | Randomized single (patient) blind trial. Method of randomization not specified. | |

| Participants | Patients undergoing lumbar discetomy presenting with radicular symptoms and radiographically confirmed herniated nucleus pulposus. | |

| Interventions | 1) 160 mg IM Depo‐Medrol and 250 mg MPPS at start of procedure. Macerated fat graft soaked in 80 mg Depo‐Medrol placed over affected nerve root after discetomy. 30 ml 0.25% bupivacaine infiltrated to paraspinal muscles during closure (N=12). 2) Bupivacaine procedure only (N=10). 3) No corticoids or bupivacaine (N=10). | |

| Outcomes | Length of hospital stay; postpartum narcotic analgesia; back and radicular pain on post‐op day 1. | |

| Notes | Depo‐Medrol is methylprednisolone acetate. MPPS is methylprednisolone sodium succinate. This study may largely be assessing nerve roots rather than acute spinal cord injuty. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomization methods not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomization methods not stated |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | The study was not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | The study was not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 72% of patients were followed‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol not seen |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | None observed |

Matsumoto 2001.

| Methods | Single center randomized double blind trial. Method of randomization not specified. | |

| Participants | In all 46 patients with cervical spine injury. Exclusions were only nerve root injuries, cauda equina and gunshot victims. | |

| Interventions | Treatment arm 1: (n=23) MPSS given according to NASCIS 2 protocol. Treatment arm 2: (n=23) placebo (no details of placebo provided). | |

| Outcomes | Efficacy not studied. Complications assessed 8 weeks after injury. | |

| Notes | Some evidence for MPSS group to be more severely injured. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomization methods not stated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomization methods not stated |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients, caregivers and statistical analysts blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients and caregivers blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 100% follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Only selected data on complications reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | None observed |

Otani 1994.

| Methods | Patients allocated "by envelope method" and so assumed to be randomized. Blinding is not assumed since no placebo group. | |

| Participants | Multicenter trial in Japan including 15 neurosurgery, 27 orthopedic and 11 emergency centers. Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of loss of motor or sensory function from spinal cord injury; could receive treatment within 8 hours of injury; 16‐25 years of age; obtained informed consent; available for 6 month follow‐up. Excluded: root involvement or cauda equina only; serious co‐morbidity; corticosteroid use > 100 mg MPSS or equivalent before randomization; other prespecified clinical criteria. In all 158 patients randomized (82 MPSS, 76 control) of which 81 and 70, and 70 and 47 entered the safety and efficacy analyses respectively. Reasons for drop‐out are tabulated. It appears as if largest exclusions were for control patients. Baseline differentials suggest this occurred most frequently in severely injured controls. | |

| Interventions | 1. Treated group: MPSS as bolus of 30 mg/kg for 15 mins by infusion, 45 mins pause then 23 hr maintenance infusion by 5.4 mg/kg. (NB this is an exact replication of the NASCIS 2 MPSS protocol, see Bracken et al 1990). No other corticosteroid therapy. 2. Control group: standard treatment without any corticosteroid therapy. No placebo given. NB surgery appears to have been given as necessary but this is not entirely clear from text. | |

| Outcomes | Neurological follow‐up was at 24 and 48 hrs, one and six weeks, three and six months. Motor function, pin and light touch sensation were assessed using NASCIS 2 criteria and Frankel's classification (at 6 months). Urinary function and sphincter control were evaluated. A global improvement assessment was also used. A large number of laboratory values and vital signs were measured. | |

| Notes | A translation of this paper from the original Japanese has been provided by Pharmacia Upjohn Inc. Copies of the English translation are available from the editor of this review. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | See Methods |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | See Methods |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding in this study ‐ control is conventional therapy |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding in this study ‐ done by attending doctor |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 74% follow‐up at final six month outcome assessment |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Published reports concur with protocol expectations (reviewer has copy of protocol) |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Upjohn directly funded the study |

Petitjean 1998.

| Methods | Single center trial. Randomization methods: two numbers given each treatment and followed "table de permutation au hasard" and balanced every eight patients. Administration of intervention not masked. | |

| Participants | Eligible patients had a diagnosed spinal cord injury, gave consent, were hospitalized within 8h of injury, were aged 16 to 64, and met other clinical criteria. | |

| Interventions | 1) Methylprednisolone bolus of 30mg/kg over 1h followed by 5.4mg/kg/h for 23h (N=27). 2) Nimodipine 0.015mg/kg/h over 2h followed by 0.03mg/kg/h for 7days if MABP > 60mgHg (N=27). 3) Both of the above treatments given concurrently (N=27). 4) No pharmacologic treatment (N=25). | |

| Outcomes | Neurological examination using ASIA criteria at admission and 1year after injury. Outcome assessed blind. | |

| Notes | A translation of this paper from the original French is available from the Cochrane Injuries review Group. ASIA and NASCIS neurological examinations are identical except for one additional segment measured in NASCIS. Additional information obtained from author but N's slightly larger in published report. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization methods not stated but blocked at 8 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomization methods not stated |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding in this study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding in this study |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 94% follow‐up at 1 year final outcome assessment |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol not seen |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Protocol not seen |

Pettersson 1998.

| Methods | Randomized double blind trial. Method of randomization not specified. | |

| Participants | Men and women with whiplash injury Grade 2 and 3 by Quebec criteria and enrolled within 8 hours of injury. | |

| Interventions | (1) Methylprednisolone bolus of 30 mg/kg for 15 min, wait 45 min, then 5.4 mg/kg/h for 23h (N=20). (2) Placebo (N=20). | |

| Outcomes | Repeated neurological examinations, VAS‐scales and pain sketch form at baseline, 2 and 6 weeks and 6 months after injury. Number of sick days. Outcomes assessed blind. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomized by pharmacist |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomized by pharmacist |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients and caregivers blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Patients and caregivers blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 100% follow‐up at final 6 month assessment |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol not seen |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Protocol not seen |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Kiwerski 1992 | Patients not randomized to treatment. |

| Pointillart 2000 | Duplicate publication of Petitjean 1998. Translated into English, very minor changes to table 3 (numbers instead of per cent), and no reference in this paper to original French version. Change in first authorship. |