Abstract

Background

Couple therapy for depression has the twofold aim of modifying negative interaction patterns and increasing mutually supportive aspects of intimate relationships, changing the interpersonal context of depression. Couple therapy is included in several guidelines among the suggested treatments for depression.

Objectives

1. The main objective was to examine the effects of couple therapy compared to individual psychotherapy for depression. 2. Secondary objectives were to examine the effects of couple therapy compared to drug therapy and no/minimal treatment for depression.

Search methods

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid) and PsycINFO (Ovid) were searched to 19 February 2018. Relevant journals and reference lists were checked.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials examining the effects of couple therapy versus individual psychotherapy, drug therapy, or no treatment/minimal treatment for depression were included in the review.

Data collection and analysis

We considered as primary outcomes the depressive symptom level, the depression persistence, and the dropouts; the relationship distress level was a secondary outcome. We extracted data using a standardised spreadsheet. Where data were not included in published papers, we tried to obtain the data from the authors. We synthesised data using Review Manager software version 5.3. We pooled dichotomous data using the relative risk (RR), and continuous data calculating the standardised mean difference (SMD), together with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We employed the random‐effects model for all comparisons and also calculated a formal test for heterogeneity, the natural approximate Chi2 test.

Main results

We included fourteen studies from Europe, North America, and Israel, with 651 participants. Eighty per cent of participants were Caucasian. Therefore, the findings cannot be considered as applicable to non‐Western countries or to other ethnic groups in Western countries. On average, participants had moderate depression, preventing the extension of results to severely depressed patients. Almost all participants were aged between 36 and 47 years.

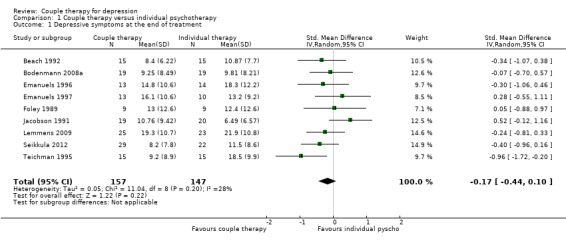

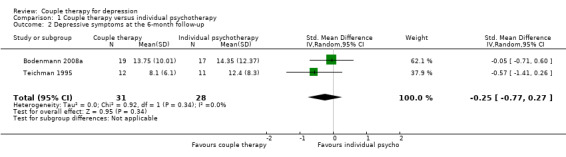

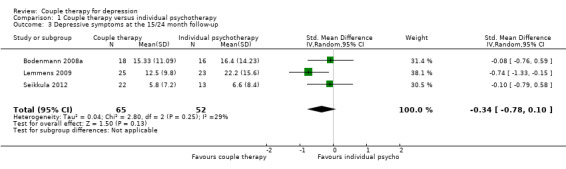

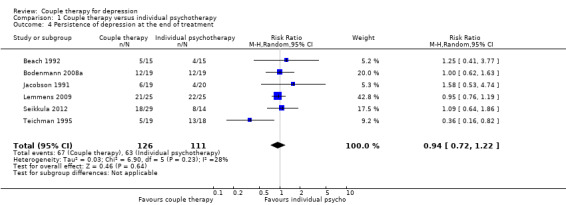

There was no evidence of difference in effect at the end of treatment between couple therapy and individual psychotherapy, either for the continuous outcome of depressive symptoms, based on nine studies with 304 participants (SMD −0.17, 95% CI −0.44 to 0.10, low‐quality evidence), or the proportion of participants remaining depressed, based on six studies with 237 participants (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.22, low‐quality evidence). Findings from studies with 6‐month or longer follow‐up confirmed the lack of difference between the two conditions.

No trial gave information on harmful effects. However, we considered rates of treatment discontinuation for any reason as a proxy indicator of adverse outcomes. There was no evidence of difference for dropout rates between couple therapy and individual psychotherapy, based on eight studies with 316 participants (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.41, low‐quality evidence).

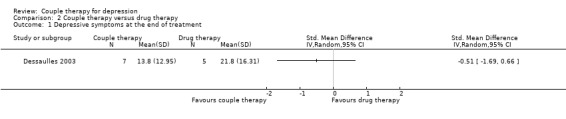

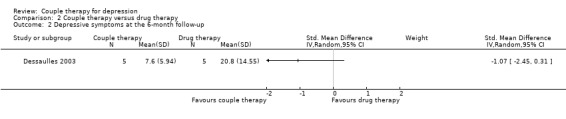

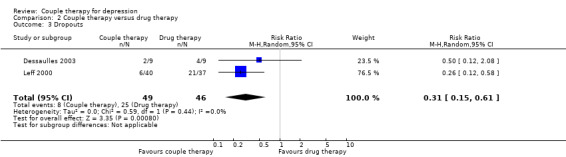

Few data were available for the comparison with drug therapy. Data from a small study with 12 participants showed no difference for the continuous outcome of depressive symptoms at end of treatment (SMD −0.51, 95% CI −1.69 to 0.66, very low‐quality evidence) and at 6‐month follow‐up (SMD −1.07, 95% CI ‐2.45 to 0.31, very low‐quality evidence). Data on dropouts from two studies with 95 participants showed a clear advantage for couple therapy (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.61, very low‐quality evidence). However, this finding was heavily influenced by a single study, probably affected by a selection bias favouring couple therapy.

The comparison between couple therapy plus drug therapy and drug therapy alone showed no difference in depressive symptom level, based on two studies with 34 participants (SMD −1.04, 95% CI ‐3.97 to 1.89, very low‐quality evidence) and on dropouts, based on two studies with 45 participants (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.07 to 15.52, very low‐quality evidence).

The comparison with no/minimal treatment showed a large significant effect favouring couple therapy both for depressive symptom level, based on three studies with 90 participants: (SMD −0.95, 95% CI −1.59 to −0.32, very low‐quality evidence) and persistence of depression, based on two studies with 65 participants (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.70, very low‐quality evidence). No data were available for dropouts for this comparison.

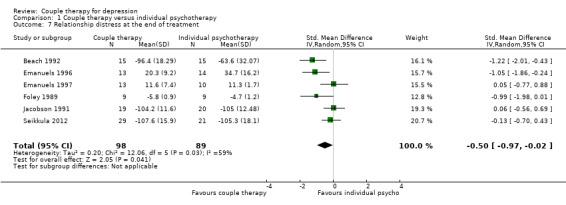

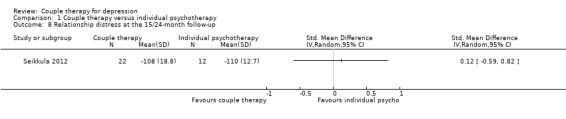

Concerning relationship distress, the comparison with individual psychotherapy showed that couple therapy appeared more effective in reducing distress level at the end of treatment, based on six studies with 187 participants (SMD −0.50, CI −0.97 to −0.02, very low‐quality evidence) and the persistence of distress, based on two studies with 81 participants (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.98, very low‐quality evidence). The quality of evidence was heavily affected by substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 59%). In the analysis restricted to studies including only distressed couples, no heterogeneity was found and the effect in distress level at the end of treatment was larger (SMD −1.10, 95% CI −1.59 to −0.61). Very few data on this outcome were available for other comparisons.

We assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE system. The results were weakened by the low quality of evidence related to the effects on depressive symptoms, in comparison with individual psychotherapy, and by very low quality evidence for all other comparisons and for the effects on relationship distress. Most studies were affected by problems such as the small number of cases, performance bias, assessment bias due to the non‐blinding outcome assessment, incomplete outcome reporting and the allegiance bias of investigators. Heterogeneity was, in particular, a problem for data about relationship distress.

Authors' conclusions

Although there is suggestion that couple therapy is as effective as individual psychotherapy in improving depressive symptoms and more effective in improving relations in distressed couples, the low or very low quality of the evidence seriously limits the possibility of drawing firm conclusions. Very few data were available for comparisons with no/minimal treatment and drug therapy. Future trials of high quality should test in large samples with a long follow‐up of the effects of couple therapy in comparison to other interventions in discordant couples with a depressed partner, considering the role of relationship quality as a potential effect mediator in the improvement of depression.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Middle Aged, Interpersonal Relations, Marital Therapy, Antidepressive Agents, Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use, Depression, Depression/epidemiology, Depression/therapy, Patient Dropouts, Patient Dropouts/statistics & numerical data, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Sex Factors

Plain language summary

Couple therapy for depression

Why is this review important?

Depression is a common mental disorder characterised by sadness, loss of pleasure in most activities, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, thoughts of death or suicide. Couple therapy has been suggested as a treatment for couples with a depressed partner on the basis of the association between depressive symptoms and relationship distress, the role of relational negative factors in onset and maintenance of depression, and the buffering effect of intimacy and interpersonal support. Couple therapy works by modifying negative interactional patterns and increasing mutually supportive aspects of relationships. It is important to know whether couple therapy can help people with depression.

Who will be interested in this review?

This review will be of interest to people with depression, their partners, and people involved in their care.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

This review aimed to assess evidence about the effects of couple therapy for couples with a depressed partner.

Which studies were included in the review?

We considered studies of couple therapy delivered in outpatient settings to couples in which a partner had a clinical diagnosis of depressive disorder. We included 14 studies with 651 participants .Thirteen of the studies were randomised controlled trials, where participants were assigned by chance alone to the couple therapy treatment group or usual care. However, one study was not completely randomised due to therapist availability.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

There was low‐quality evidence to suggest that couple therapy is as effective as individual psychotherapy in improving depression. People with depression might do better when receiving couple therapy compared with no treatment, but we are very uncertain about this effect because of the very low quality of studies. In comparison with treatment with antidepressant medication, limited data was available. Although data on few dropouts favour couple therapy, the very low quality of data seriously weakens this finding. The comparison between couple therapy plus antidpressant medication and antidepressants alone showed no difference in depressive symptom level, but the results were based on two small studies. Couple therapy was more effective in reducing relationship distress than individual psychotherapy and this effect was enhanced when distressed couples were considered separately. However, this result has to be considered with great caution, because of the very low quality of studies. Most studies were affected by small sample sizes, unclear sample representativeness, loss of participants at follow‐up, and investigators' allegiance bias. Moreover, there were few follow‐ups that went beyond 6 months post‐treatment. Only one study tested whether improvements in couple relationships led to improvement in depression, finding supporting evidence for that. However, the small sample of this study and the lack of other studies which investigated this hypothesis means we could not test in this review if this finding was supported. Although it is difficult to draw conclusions with any confidence on differences between couple therapy and other treatments for depression, the possibility of improvement in couple relationships may favour its choice when relationship distress is a major problem.

What should happen next?

We need good quality trials, testing in large samples with long follow‐up of the effects of couple therapy in comparison to other interventions, especially in distressed couples.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings for the comparison with individual psychotherapy.

| Couple therapy compared with individual psychotherapy for depression | ||||||

|

Patient or population: heterosexual adult couples aged > 18 with a partner having a clinical diagnosis of depressive disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: couple therapy Comparison: individual psychotherapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Individual psychotherapy | Couple therapy | |||||

|

Depressive symptoms at end of treatment Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). BDI is a self‐report inventory including 21 questions, each answer being scored from 0 to 3 with the total score ranging from 0 to 63. HDRS is an expert‐rated questionnaire including 17 items scored from 0 to 2 or 5 depending on the item, with the total score ranging from 0 to 50. In both scales, higher scores indicate more severe depression |

The mean depression level at post‐treatment in the intervention group was 0.17 standard deviations lower than in the control group (0.44 lower to 0.10 higher) |

304 (9 studies) |

Lowa ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

This is a small effect. No evidence that couple therapy reduced depression in participants, compared to individual psychotherapy. | ||

|

Persistence of depression at end of treatment Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) |

Study population | RR 0.94 (0.72 to 1.22) |

237 (6 studies) |

Lowb ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

No evidence that couple therapy reduced the rates of people remaining depressed, compared to individual psychotherapy. | |

| 568 per 1000 |

532 per 1000 (445 to 617) |

|||||

| Dropouts | Study population | RR 0.85 (0.51 to 1.41) |

364 (9 studies) |

Lowc ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

No evidence that couple therapy reduced the dropout risk, compared to individual psychotherapy. | |

| 223 per 1000 |

190 per 1000 (141 to 252) |

|||||

|

Relationship distress at end of treatment Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) or Maudsley Marital Questionnaire (MMQ). DAS is a self‐report inventory with 32 items, with the total score ranging from 0 to 151. Higher scores indicate less distress. MMQ is a self‐report questionnaire including 15 items covering relational and sexual adjustment, with the total score ranging from 0 to 120. Higher scores indicate more distress. |

The mean relationship distress level at post‐treatment in the intervention group was 0.50 standard deviations lower than in the control group (0.97 to 0.02 lower) |

187 (6 studies) |

Very lowd ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

This is a moderate effect. Couple therapy appeared to be more effective than individual psychotherapy in reducing relationship distress, but studies were of poor quality. | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the control group risk. The corresponding risk is based on the assumed risk in the treatment group and the relative effect of intervention. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the standardised mean difference of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; SMD: Standardised mean difference; RR; Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a High risk of bias in all trials due to lack of blinding of participants and in seven trials due to lack of blinding in outcome assessment. Conflict of interest raising the possibility of allegiance bias in three trials. Possible indirectness of evidence due to recruitment of populations to some extent not representative of clinical practice in four studies. Quality of evidence downgraded by two levels. The overall judgement about biases is likely to seriously affect the interpretation of results.

bHigh risk of bias in all trials due to lack of blinding of participants and in five trials due to lack of blinding in outcome assessment. Conflict of interest raising the possibility of allegiance bias in three trials. Possible indirectness of evidence due to recruitment of populations to some extent not representative of clinical practice in two studies. Quality of evidence downgraded by two levels. The overall judgement about biases is likely to seriously affect the interpretation of results.

c High risk of bias in all trials due to lack of blinding of participants and conflict of interest raising the possibility of allegiance bias. Possible indirectness of evidence due to recruitment of populations to some extent not representative of clinical practice in two studies. Very wide confidence interval. Quality of evidence downgraded by two levels.The overall judgement about biases is likely to seriously affect the interpretation of results.

d High risk of bias in all trials due to lack of blinding of participants and lack of blinding in outcome assessment. Conflict of interest raising the possibility of allegiance bias in two trials. Possible indirectness of evidence due to recruitment of populations to some extent not representative of clinical practice in two studies. Substantial statistical heterogeneity. Quality of evidence downgraded by three levels. The overall judgement about biases is likely to very seriously affect the interpretation of results.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings for the comparison with drug therapy.

| Couple therapy compared with drug therapy for depression | ||||||

|

Patient or population: heterosexual adult couples aged >18 with a partner having a clinical diagnosis of depressive disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: couple therapy Comparison: drug therapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Drug therapy | Couple therapy | |||||

|

Depressive symptoms at end of treatment Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). BDI is a self‐report inventory including 21 questions, each answer being scored from 0 to 3 with the total score ranging from 0 to 63. HDRS is an expert‐rated questionnaire including 17 items scored from 0 to 2 or 5 depending on the item, with the total score ranging from 0 to 50. In both scales, higher scores indicate more severe depression. |

The mean depression level at post‐treatment in the intervention group was 0.51 standard deviations lower than in the control group (1.69 lower to 0.66 higher) |

12 (1 study) |

Very lowa ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

No evidence that couple therapy reduced depression in participants, compared to drug therapy. | ||

| Persistence of depression at end of treatment | No data available | |||||

| Dropouts | Study population | RR 0.31 (0.15 to 0.61) |

95 (2 studies) |

Very lowb ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

Couple therapy appeared to be more effective than drug therapy in reducing dropout risk, but studies were of very poor quality. | |

| 543 per 1000 |

163 per 1000 (85 to 290) |

|||||

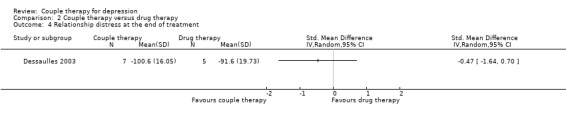

|

Relationship distress at post‐treatment Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) or Maudsley Marital Questionnaire (MMQ). DAS is a self‐report inventory with 32 items, with the total score ranging from 0 to 151. Higher scores indicate less distress. MMQ is a self‐report questionnaire including 15 items covering relational and sexual adjustment, with the total score ranging from 0 to 120. Higher scores indicate more distress. |

The mean relationship distress level at post‐treatment in the intervention group was 0.47 standard deviations lower than in the control group (1.64 lower to 0.70 higher) |

12 (1 study) |

Very lowa ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

No evidence that couple therapy reduced relationship distress in participants, compared to drug therapy. | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the control group risk. The corresponding risk is based on the assumed risk in the treatment group and the relative effect of intervention. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the standardised mean difference of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; SMD: Standardised mean difference; RR; Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a High risk of bias due to lack of blinding of participants. Conflict of interest raising the possibility of allegiance bias. A single trial with very few participants. Indirectness of evidence due to recruitment of a population possibly not representative of clinical practice. Quality of evidence downgraded by three levels. The overall judgement about biases is likely to very seriously affect the interpretation of results.

b High risk of bias due to lack of blinding of participants. Conflict of interest raising the possibility of allegiance bias. Two trials. Results heavily influenced by a single trial at high risk of bias showing indirectness of evidence due to recruitment of a population not representative of clinical practice. Quality of evidence downgraded by three levels. The overall judgement about biases is likely to very seriously affect the interpretation of results.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings for the comparison with no/minimal treatment.

| Couple therapy compared with no/minimal treatment for depression | ||||||

|

Patient or population: heterosexual adult couples aged > 18 with a partner having a clinical diagnosis of depressive disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: couple therapy Comparison: no/minimal therapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No/minimal treatment | Couple therapy | |||||

|

Depressive symptoms at the end of treatment Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). BDI is a self‐report inventory including 21 questions, each answer being scored from 0 to 3 with the total score ranging from 0 to 63. HDRS is an expert‐rated questionnaire including 17 items scored from 0 to 2 or 5 depending on the item, with the total score ranging from 0 to 50. In both scales, higher scores indicate more severe depression. |

The mean depression level at post‐treatment in the intervention group was 0.95 standard deviations lower than in the control group (1.59 to 0.32 lower) |

90 (3 studies) |

Very lowa ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

This is a large effect. Couple therapy appeared to be more effective than no/minimal treatment in reducing depression, but studies were of very poor quality. |

||

|

Persistence of depression at the end of treatment Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) |

Study population | RR 0.48 (0.32 to 0.70) | 65 (2 studies) |

Very lowb ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

Couple therapy appeared to be more effective than no/minimal treatment in reducing the rates of people remaining depressed, but studies were of very poor quality. | |

| 935 per 1000 | 441 per 1000 (289 to 606) | |||||

| Dropouts | No data available | |||||

|

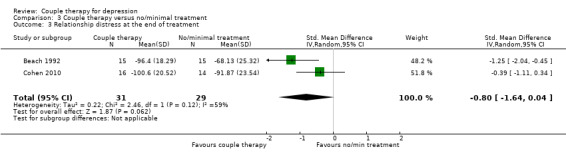

Relationship distress at the end of treatment Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) or Maudsley Marital Questionnaire (MMQ). DAS is a self‐report inventory with 32 items, with the total score ranging from 0 to 151. Higher scores indicate less distress. MMQ is a self‐report questionnaire including 15 items covering relational and sexual adjustment, with the total score ranging from 0 to 120. Higher scores indicate more distress. |

The mean relationship distress level at post‐treatment in the intervention group was 0.80 standard deviations lower than in the control group (1.64 lower to 0.04 higher) |

60 (2 studies) |

Very lowc ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

No evidence that couple therapy reduced relationship distress in participants, compared to no/minimal treatment. | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a High risk of bias due to lack of blinding of participants and of outcome assessment. Two out of three studies with high risk of conflict of interest raising the possibility of allegiance bias. Very wide confidence interval. Quality of evidence downgraded by three levels. The overall judgement about biases is likely to very seriously affect the interpretation of results.

b High risk of bias due to lack of blinding of participants and of outcome assessment. One study with high risk of conflict of interest raising the possibility of allegiance bias. One study reported incomplete outcome data. Quality of evidence downgraded by three levels. The overall judgement about biases is likely to very seriously affect the interpretation of results.

c High risk of bias due to lack of blinding of participants and of outcome assessment. Two out of three studies with high risk of conflict of interest raising the possibility of allegiance bias. Very wide confidence interval. Quality of evidence downgraded by three levels.The overall judgement about biases is likely to very seriously affect the interpretation of results.

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings for the comparison between couple therapy plus drug therapy and drug therapy alone.

| Couple therapy plus drug therapy compared with drug therapy alone for depression | ||||||

|

Patient or population: heterosexual adult couples aged > 18 with a partner having a clinical diagnosis of depressive disorder Settings: outpatient Intervention: couple therapy plus drug therapy Comparison: drug therapy alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Drug therapy alone | Couple therapy plus drug therapy | |||||

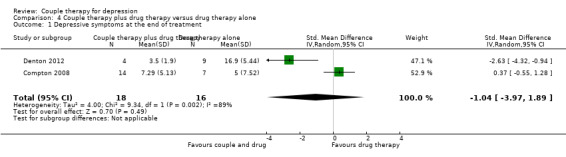

|

Depressive symptoms at the end of treatment Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). BDI is a self‐report inventory including 21 questions, each answer being scored from 0 to 3 with the total score ranging from 0 to 63. HDRS is an expert‐rated questionnaire including 17 items scored from 0 to 2 or 5 depending on the item, with the total score ranging from 0 to 50. In both scales, higher scores indicate more severe depression |

The mean depression level at post‐treatment in the intervention group was 1.04 standard deviations lower than in the control group (3.97 lower to 1.89 higher) |

34 (2 studies) |

Very lowa ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

No evidence that couple therapy plus drug therapy reduced depression in participants, compared to drug therapy alone. | ||

| Persistence of depression at the end of treatment | No data available | |||||

| Dropouts | Study population | RR 1.03 (0.07 to 15.52) | 45 (2 studies) |

Very lowa ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

No evidence that couple therapy plus drug therapy reduced droput risk in participants, compared to drug therapy alone. | |

| 158 per 1000 | 231 per 1000 (110 to 420) | |||||

|

Relationship distress at the end of treatment Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) or Quality of Marriage Index ‐ QMI. DAS is a self‐report inventory with 32 items, with the total score ranging from 0 to 151. Higher scores indicate less distress. QMI is a six‐item self‐rated inventory. Respondents answer the first five items on a 7‐point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The sixth item is answered on a 10‐point scale ranging from 1 (extremely low) to 10 (extremely high). Lower scores represent lower relational quality. A score of 28 or less corresponds to the cut‐off of DAS considered as a criterion for relationship distress. |

The mean relationship distress level at post‐treatment in the intervention group was 0.60 standard deviations lower than in the control group (1.35 lower to 0.14 higher) |

34 (2 studies) |

Very lowa ⊕⊝⊝⊝ |

No evidence that couple therapy plus drug therapy reduced relationship distress in participants, compared to drug therapy alone. | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a Data from two studies with small samples at high risk of bias. Very wide confidence interval. Substantial statistical heterogeneity. Quality of evidence downgraded by three levels. The overall judgement about biases is likely to very seriously affect the interpretation of results.

Background

Description of the condition

Depression is a common mental disorder primarily characterised by pervasive sadness with loss of interest or pleasure in most activities. It is often associated with changes in appetite, sleeping patterns, agitation or retardation, decreased energy, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, impairment in concentration, and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide. It is generally agreed that, according to current diagnostic criteria, depressive disorders can be ranged along a continuum by levels of symptom severity, number of mental or physical symptoms, and duration (APA 2000; WHO 1992).

Depression is present in all countries and all age groups. Its distribution is nonetheless different across countries, age groups and genders, probably reflecting cultural differences or variations in risk factors. In Western countries, one‐year prevalence rates of major depression in adults cluster around 5% and lifetime rates around 15% (Hasin 2005; Üstün 2004). Less reliable data are available for minor depressive disorders. However, recent estimates show a one‐year prevalence of chronic minor depression at about 2% (Waraich 2004). In many low and middle‐income countries, rates are even higher (Kessler 2013). One main feature of depression is the different distribution in the two genders. Depression in women is about twice as prevalent as it is in men (Üstün 2004). Although depression is often short‐lasting or self‐limiting, in a substantial number of cases, it follows a chronic, relapsing, or recurrent course. Recovery following a major depressive episode occurs within one year in about 50% of cases (Bland 1997). Moreover, about 60% of people who have recovered from a first episode of major depression will experience further depressive symptoms in the following five years (Mueller 1999).

Depression carries an overall increased mortality risk, with a high risk of suicide compared to the general population. A Canadian study observed a twofold standardised mortality rate for all causes (Newman 1991). A meta‐analysis estimated the lifetime suicide risk in depressed people at around 2% (Bostwick 2000). Depression can be a very disabling illness. Its symptoms interfere with daily functioning, social role performance, work productivity, and physical wellbeing. According to recent estimates (Vos 2000), the disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) rates per 1000 population for depression were 5.3 in males and 7.7 in females. Depression in 2010 has been estimated as the second most important cause of years lived with disability worldwide (Ferrari 2013).

Depression and other affective disorders impose a substantial economic burden on both developed and developing countries. In the United States, in 1998, it was estimated to cost around USD 65 billion (Berto 2000). In Europe, the annual cost of depression was estimated at EUR 118 billion in 2004 (Sobocki 2006). Direct costs alone totaled EUR 42 billion and indirect costs due to morbidity and mortality were estimated at EUR 76 billion. This makes depression the most costly among mental and neurological disorders in Europe, accounting for 33% of the total cost. The cost of depression corresponds to 1% of the total economy of Europe (Sobocki 2006). Hidden social and emotional costs, which are much more difficult to estimate, are relevant for patients, family members and caregivers (Goodman 1999).

Risk factors for depressive disorders are manifold, ranging from genetically‐based biological vulnerability to social and interpersonal factors. Childhood events, adverse life circumstances, and stressful relationships play a relevant role in the onset and maintenance of depression (Kendler 1999).

Description of the intervention

In addition to antidepressant drug therapy, a number of psychological interventions have shown to be effective as treatment for depression (Cuijpers 2008a). Psychological and pharmacological treatments are considered equally effective (Cristea 2017). Moreover, psychological treatments are increasingly becoming a focus of interest as a consequence of various factors, such as lower dropout rates, contraindications and side effects of medications, failure of many patients to comply with maintenance drug therapy, and patients' preference (Chilvers 2001; Cuijpers 2008b). Although the best evidence is available for cognitive‐behavioural therapies, other treatment models, such as interpersonal therapy, psychodynamic therapy based on psychoanalytical concepts, non‐directive counselling, and couple therapy have been included in most guidelines as possibly effective interventions (Malhi 2009; NICE 2009).

Couple therapy has been first suggested more than forty years ago as an approach for couples with a depressed spouse (Friedman 1975). It is a form of psychological intervention involving the presence of both partners of a committed relationship in sessions led by a trained therapist, with the twofold aim of modifying negative interactional patterns and promoting supportive aspects of a close relationship. The main focus of intervention is always on mutual relationship aspects (Lebow 2012).

A large body of evidence supports a close link between relationship variables and depression (Denton 2003). Community‐based epidemiological studies and surveys using self‐report questionnaires show a strong cross‐sectional association between depressive symptoms and marital dissatisfaction (Whisman 2001). Longitudinal studies show the reciprocal influence of depression and couple problems: either depressive symptoms predict later marital dissatisfaction or marital dissatisfaction predicts onset of depressive episodes (Kronmüller 2011); stressful relational events, such as partner infidelity or threats of disruption of a romantic relationship can precipitate or exacerbate depressive symptoms (Cano 2000); interactions in couples with one depressed partner are often characterized by criticism, hostility and overprotection, i.e. a highly expressed emotional style, known to be among the most important stressors involved in the causal chain leading to relapse of depressive episodes (Hooley 2007); by contrast, interpersonal support, enhanced intimacy, and help by a partner in implementing coping strategies have a buffering effect on depressive symptoms, thus facilitating recovery (Beach 1998).

A number of partly overlapping theories have been advanced to conceptualise the role of the relational processes in onset and maintenance of depression. Recent integrative approaches suggest that depressed mood and conflict in couples may be mutually influential: relationship dissatisfaction leads to depression by reducing social support and increasing stress and hostility, while behaviour of depressed individuals may elicit rejection from a partner and increase subjective and objective indicators of interpersonal stress, thus creating a vicious cycle in which disruptive interactional aspects and depression reinforce each other (Rehman 2008).

Such findings provide the logical foundation for the assumption that couple‐focused therapy should be more effective than an individual‐based treatment for patients with depression living with a regular partner, especially if there is a significant relationship distress.

How the intervention might work

Couple therapy, mainly based on social learning and systemic theories, has the twofold aim of modifying negative interactional patterns and increasing mutually supportive aspects of couple relationships. Although a variety of treatment models have been used, a number of common principles underlie all interventions: (a) altering the couple's view of the presenting problem to be more objective, contextualised, and related to the couple interactions ; (b) decreasing emotion‐driven, dysfunctional behaviour; (c) eliciting emotion‐based behaviour; (d) increasing constructive communication patterns; and (e) emphasising strengths and reinforcing gains (Benson 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

A number of controlled clinical trials examining the effectiveness of couple therapy for depression have been conducted. A number of authors have concluded that several forms of couple therapy can effectively treat depression (Baucom 1998). However, although some narrative reviews have been published (Denton 2006; Gilliam 2005; Gupta 2003; Hollon 2012; Whisman 2012), data from clinical trials have never been subjected to quantitative analyses. This review aimed at filling this gap, by appraising and summarising evidence from all the available studies, to provide an overall assessment of the role of couple therapy among psychosocial treatments for depression. The publication of new trials on this topic made it necessary to update the first edition of this review.

Objectives

1. The main objective was to examine the effects of couple therapy compared to individual psychotherapy for depression. 2. Secondary objectives were to examine the effects of couple therapy compared to drug therapy and no/minimal treatment for depression.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Wer considered for this review randomised controlled trials, including cluster trials, and quasi‐randomised controlled trials, in which treatment assignment was decided through methods such as alternation, rotation, or randomisation restricted by therapist availability, which has been used used in psychotherapy research (Cristea 2017). We did not consider naturalistic and observational studies.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

Heterosexual adult couples aged 18 years or more with a partner having a clinical diagnosis of depressive disorder. We included studies adopting any standardised and validated diagnostic criteria to define depressive disorder.

Diagnosis

Depressive disorder diagnosed by any of the following diagnostic systems: Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer 1978), criteria of the Present State Examination (Wing 1974), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM‐III) (APA 1980), DSM‐III‐Revised (R) (APA 1987), DSM‐Fourth Edition (IV) (APA 1994), DSM‐IV‐Text Revision (TR) (APA 2000), DSM‐5 (APA 2013), and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD−10) (WHO 1992).

Comorbidities

We included trials whether or not comorbidities were present in the sample.

Setting

We included studies conducted in any outpatient setting either in primary care or specialist services. We excluded studies conducted in inpatient settings. However, we included studies recruiting participants during inpatient admission if most of the intervention was delivered after discharge.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

Couple therapy, for the purpose of this review was defined as a structured psychological intervention in which a trained therapist meets both partners of a committed relationship, in regular face‐to‐face sessions, with the explicit aim of modifying dysfunctional patterns of interaction and enhancing positive relationships. Any treatment model delivered to couples was considered for inclusion. In addition to couple therapy alone, the combination of couple therapy and antidepressant drug therapy was also considered.

Excluded interventions

1. Studies that focused on family therapy, where the treatment was delivered to the whole family unit, including children.

2. Studies that were targeted to postnatal depression.

Comparator interventions

The main comparison was with individual psychotherapy. Any intervention defined by the authors as 'individual psychotherapy', irrespective of the treatment model, was included under this heading. We considered as suitable all models supported by evidence of efficacy in treatment of depression: cognitive, behavioural, interpersonal, psychodynamic, supportive, problem‐solving (Cuijpers 2008a).

Secondary comparisons were with antidepressant drug therapy and with no/minimal treatment. In accordance with the recent guidelines (Bauer 2013), the following drug categories were considered as suitable: tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, norepinephrine‐dopamine reuptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and atypical antidepressants. No/minimal treatment in psychotherapy research usually includes waiting lists or unspecific contacts. All studies included in this review providing comparison with no/minimal treatment used waiting list as a control condition.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Efficacy outcome. Depressive symptom level, presented as continuous (means and standard deviations) or dichotomous (persistence of depression versus remission or clinically significant improvement) data, measured through use of self‐rated questionnaires, such as Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1961), or clinician‐rated scales, such as the Hamilton Rating Scales for Depression (HRSD) (Hamilton 1960), and the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS‐C30) (Rush 1996).

2. Adverse events outcome. Proportion of dropouts or participants who discontinued treatment for any reason. This outcome was not considered in studies providing comparison with waitlist, because discontinuation of treatment does not make any sense in a no‐treatment condition.

Secondary outcomes

3. Relationship distress. Since modification of dysfunctional patterns of interaction is an aim of couple therapy, we considered measures of relationship distress according to standardised instruments. In couple therapy research, the most commonly used is by far the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) (MacIntosh 2014; Spanier 1976). We assessed relationship distress in two ways: as continuous (means and standard deviations) and dichotomous (significant versus not significant clinical improvement) data.

Timing of outcome assessment

We decided to assess end of treatment outcomes, short‐term and long‐term outcomes. After an examination of outcome research in psychotherapy of depression (Cuijpers 2008a), we decided to consider 6‐month follow‐up as 'short‐term' and 15 or more months follow‐up as 'long‐term'.

Hierarchy of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Depressive symptoms

Although the BDI (Beck 1961) is the most often used in psychotherapy research, we considered that this self‐report measure would carry a high risk of bias because, in all studies included in this review, the participants were aware of the assigned intervention. Therefore, when more than one scale was used, we preferred as a first choice the expert‐rated HRSD (Hamilton 1960), provided it was used by blind assessors. If assessment by HRSD was not blind, thus carrying a high risk of bias as well, we preferred BDI. Although operational criteria for remission have been suggested for both scales, through the identification of cut‐offs derived from studies on normative samples discriminating between mental health and psychopathology (Grundy 1996; Ogles 1995), there is no agreement on the exact definition of such cut‐offs. Therefore, we accepted the criteria indicated by the authors to define remission or clinical significant improvement.

We list below the main scales that provided data on this outcome:

Beck Depression Inventory ‐ BDI

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI, BDI‐II) is a 21‐question multiple‐choice self‐report inventory, one of the most widely used instruments for measuring the severity of major depression (Beck 1961; Beck 1996). Both the BDI and the BDI‐II contain 21 questions, each answer being scored on a scale value of 0 to 3. Higher total scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. The cut‐offs used in recent research are: 0 to 13: minimal depression; 14 to 19: mild depression; 20 to 28: moderate depression; and 29 to 63: severe depression. Depression can be thought of as having two components: the affective component (e.g. mood) and the physical or 'somatic' component (e.g. loss of appetite). The BDI‐II reflects this and can be separated into two subscales. The affective subscale contains eight items: pessimism, past failures, guilt feelings, punishment feelings, self‐dislike, self‐criticism, suicidal thoughts or wishes, and worthlessness. The somatic subscale consists of the other thirteen items: sadness, loss of pleasure, crying, agitation, loss of interest, indecisiveness, loss of energy, change in sleep patterns, irritability, change in appetite, concentration difficulties, tiredness and/or fatigue, and loss of interest in sex.

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression ‐ HRSD

The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) is a multiple item clinician‐rated questionnaire used to provide an indication of depression severity to evaluate treatment outcome (Hamilton 1960; Hamilton 1980). The original version contains 17 items to be rated (HRSD−17) (Hamilton 1980). Each item of the questionnaire is scored on a 3 or 5 point scale, depending on the item, and the total score is compared to the corresponding descriptor. A score of 0 to 7 is considered to be normal. Scores of 20 or higher indicate moderate, severe, or very severe depression, and are usually required for entry into a clinical trial. Questions 18 to 21 may be recorded to give further information about the depression (such as whether diurnal variation or paranoid symptoms are present), but are not part of the scale.

Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology‐IDS 30

The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology‐IDS 30 (Rush 1996), is a multiple item clinician‐rated inventory used to differentiate depression from euthymic states, to assess the depression severity and to evaluate change over time. It comprises 30 items scored on a 4 point scale. A score below 12 is considered to be normal, between 12 and 23 indicates mild depression, 24 to 36 moderate depression, 37 to 46 moderate to severe, and more than 46, severe depression.

Secondary outcomes

Relationship distress

If there were several measures used, we considered as a first choice the widely used DAS (Dyadic Adjustment Scale) (Spanier 1976), then the instrument with the more robust psychometric properties.

We list below the scales that provided data on this outcome:

Dyadic Adjustment Scale ‐ DAS

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier 1976), is currently the most widely utilized self‐report measure of relationship adjustment in the social and behavioural sciences. It is a 32‐item measure developed for couples in stable committed relationships. DAS often serves as a dependent measure of couple satisfaction or to classify 'distressed' versus 'nondistressed' couples in interaction task research. Scores range from 0 to 151, with higher scores indicating better adjustment. Scores below 95 are usually considered as indicators of relationship distress. In Spanier 1976, original factor analysis of the DAS identified four subscales, which he advised could each be used independently: Dyadic Consensus, Dyadic Satisfaction, Dyadic Cohesion, and Affectional Expression. Locke‐Wallace Marital Adjustment Scale ‐ LWMAS

The Locke Wallace Marital Adjustment Scale is a 15‐item self‐rated scale that assesses couple satisfaction (Locke 1976). The test has been widely used for the assessment of relational quality over the last forty years. The test consists of 15 items and it is quick to administer and score despite unequal weights for different items. For each item, there is an algorithm leading to one of three acuity ranges (i.e. Very Unhappy, Happy, Perfectly Happy). The logic for the user receiving specific feedback is included in the algorithms below each item. Total score is the sum of all items, with possible range from 2 to 158. For the total score, the following cut‐offs are proposed: 100 to 158 for high satisfaction; 85 to 99 for moderate satisfaction; 2 to 84 for low satisfaction. Maudsley Marital Questionnaire ‐ MMQ

The Maudsley Marital Questionnaire is a standardised and validated self‐rated questionnaire with 15 items relating to relational and sexual adjustment, with a nine‐point (0 to 8) scale appended to each question (Arrindell 1983). The MMQ defines satisfaction as the subjective evaluation of the emotional connection and the sexual relationship with the partner. Two subscales of the MMQ were identified: couple satisfaction (ten items) and sexual satisfaction (five items). Respondents are usually asked to indicate which point on the scale best described their situation over the previous 2 weeks. Items in each subscale are summed. Scores on the relational satisfaction subscale could range from 0 to 80 and on the sexual satisfaction subscale from 0 to 40, with a higher score indicating less satisfaction.

Quality of Marriage Index ‐ QMI

The Quality of Marriage Index is a standardised and validated six‐item self‐rated measure of marital satisfaction (Norton 1983). Respondents answer the first five items on a 7‐point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The sixth item is answered on a 10‐point scale ranging from 1 (extremely low) to 10 (extremely high). Lower scores represent lower relational quality. A score of 28 or less corresponds to the cut‐off of DAS considered as a criterion for relationship distress.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For the earlier version of this review, the Cochrane Common Mental Disorder's information specialist searched the specialised register (the CCMDCTR) in September 2005, using the following strategy:

Diagnosis = (Depressi* or Dysthymi*) and Intervention = ('Marital Therapy' or Couples or Family)

Details of the Group's specialised register can be found in Appendix 1.

The information specialist repeated the search in March 2010, using the same strategy, but ran additional searches on MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid) and PsycINFO (Ovid) (Appendix 2), as the register had fallen out of date at this time, due to the change over of staff at the editorial base.

Further update searches were performed on the Group's (up‐to‐date) specialised register in September 2014, May 2015 and February 2016 using the following search terms (across both the studies and references register):

#1 (depress* or dysthymi* or 'affective disorder*' or 'affective symptom*' or mood*):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #2 ((marital or marriage) NEAR relations*):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #3 ((*therap* or counsel* or treat* or intervention*) NEAR (marital or marriage or couple* or spouse* or partner*)):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #4 ((*therap* or counsel* or treat* or intervention*) and (partners near patients)):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #5 ('marital disput*' or 'conjoint therapy'):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #6 (#1 and (#2 or #3 or #4 or #5))

[Key to field tags. ti:title; ab:abstract; kw:keywords; ky:other keywords; mh:MeSH headings; mc:MeSH check words; emt:EMTREE headings]

The searches were further updated in February 2018. The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR ‒ both Studies and References), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid) and PsycINFO (Ovid) were searched on February 19th 2018. The search strategies are reported in Appendix 3.

No restrictions on date, language, or publication status were applied to the searches. The date of the latest search (results incorporated): 19 February 2018

The information specialist also searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO's trials portal (ICTRP) (all years to 19 February 2018).

Searching other resources

Handsearching

We handsearched and examined psychiatric and psychological journals identified as potentially including contributions relevant for this review. We checked all issues of the following journals between 1986 and February 2018:Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, Behavior Modification, Behaviour Therapy, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, Family Process, Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, Clinical Psychology Review, American Journal of Family Therapy, Journal of Family Therapy, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, Contemporary Family Therapy, Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy, Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice.

Reference lists

We checked the database of randomised controlled and comparative studies examining the effects of psychotherapy for adult depression run by the Department of Psychology of VU University Amsterdam (http://www.evidencebasedpsychotherapies.org). Moreover, we examined references from the text of reports of relevant trials and reviews for further trials not otherwise identified. We searched relevant books and chapters identified through reviews, trial bibliographies and electronic databases to identify trials published in books rather than journals.

Correspondence

We tried to obtain data not included in some of the published papers. We contacted the first author of the report with a standard letter, explaining the purposes of the review and the reasons for requesting additional data. In case of no answer in one month, we made an additional attempt. If no usable information was supplied, we excluded the study from the analysis related to the missing data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One reviewer (AB) screened the abstracts of all publications obtained by the search strategy, in order to identify the eligible studies. A first list of potentially eligible studies was drafted, and was cross‐checked by the second and third reviewer (BD, AP). We decided by mutual consensus on a final list of trials. No disagreement between reviewers was found about the trials to be included. We obtained and inspected all papers to assess their relevance to this review. We identified any additional report related to the trials, to search for data not found in the primary paper. All relevant papers are included in the reference to studies list (Included studies).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (AB and BD) independently evaluated trials for data extraction. Any discrepancy was resolved by resorting to the opinion of the third author (AP).

We used a data collection form to extract study characteristics and outcome data which had been piloted on at least one study in the review. Two review authors (AB and BD) extracted study characteristics and outcome data from the included studies. We considered the following study characteristics:

Methods: Study design, total duration of study, number of study centres and location, study setting, unit of allocation, withdrawals;

Participants: Number, mean age, age range, gender, ethnicity, severity of condition, diagnostic criteria, inclusion and exclusion criteria, social and demographic characteristics;

Interventions: Experimental and comparison treatments, duration of treatment;

Outcomes: Primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported;

Notes: Characteristics of therapists, treatment integrity assessment, notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

The 'Characteristics of included studies' tables report if outcome data were not provided in a usable way. We resolved any disagreement by consensus. One review author (AB) transferred data into the Review Manager (RevMan 2014). We double‐checked data by comparing the data presented in the systematic review with the study reports. A second review author (BD) spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the trial reports.

Main comparisons

1. Couple therapy versus individual psychotherapy.

2. Couple therapy versus antidepressant drug therapy;

3. Couple therapy versus no/minimal treatment;

4. Couple therapy plus drug therapy versus antidepressant drug therapy alone.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias by using the criteria described in the version 5.1.0 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The three review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for each study. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

The following domains were considered:

Random sequence generation;

Allocation concealment;

Blinding of participants and personnel;

Blinding of outcome assessment;

Incomplete outcome data;

Selective outcome reporting;

Other potential sources of bias.

We judged each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear, providing support for judgment in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarised the risk of bias across different studies for each of the domains listed. We considered blinding separately for outcomes, where necessary. Where information on risk of bias came from unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risk of bias for the studies that contributed to that outcome.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We combined dichotomous data by calculating the risk ratio (RR), with its 95% confidence interval (CI).

Continuous data

We pooled continuous data by calculating the standardised mean difference (SMD), together with 95% CI. We used the SMD to combine different scales for measuring depressive symptoms or relationship distress across studies.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not find any cluster randomised or cross‐over trials.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

In five out of 14 studies, couple therapy was compared with two control conditions (Beach 1992; Bodenmann 2008a; Jacobson 1991; Lemmens 2009; Teichman 1995). We first identified the control conditions relevant to our analysis, then for the two studies, Beach 1992 and Teichman 1995, in which two control conditions fulfilled our inclusion criteria, we performed two pairwise independent comparisons of couple therapy and each control condition.

Dealing with missing data

We checked for each study whether an intention‐to treat‐analysis was performed. If not, we checked the possibility of acceptable reasons for missing data. In the absence of any acceptable reason, we noted the risk of bias from incomplete outcome data in the 'risk of bias' table.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We estimated heterogeneity through the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic, to have an estimate of the percentage of variability not due to chance alone. We followed the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook, in which a rough guide to interpretation of I2 values is presented (Higgins 2011):

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: may represent considerable heterogeneity.

Moreover, we took into account that the importance of the observed value of I2 statistic depends on (i) magnitude and direction of effects and (ii) strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the chi2 test). If important heterogeneity emerged, we considered the investigation of the sources.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed the studies to identify selective outcome reporting. This has been considered as a source of bias and noted in the 'risk of bias' table.Concerning publication bias, we first considered performing an inspection of funnel plots, but the small number of studies available prevented us from using tests for funnel plot asymmetry.

Data synthesis

We used the random‐effects model to compute SMD and RR. The estimates produced through random‐effects models provide a conservative estimate of the average treatment effect, in contrast with fixed‐effect models, which provide the best estimate of the treatment effect (DerSimonian 1986). As we suspected heterogeneity among studies, we used the random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As previously mentioned, there is a consistent finding that relationship distress is a risk factor for depression and it has been suggested that reduction of relationship distress works as a mediator for improvement of depression. Therefore, our aim was to perform subgroup analyses by investigating separately the effects of couple therapy in distressed and nondistressed couples. However, we have not been able to conduct the planned analyses due to the lack of sufficient data.

We addressed and identified heterogeneity. When we found results showing substantial or considerable heterogeneity (i.e. substantial 50‐90%, considerable 75‐100%), we investigated whether heterogeneity substantially altered the results. If yes, we commented on this in the text.

Sensitivity analysis

The earlier version of this analysis did not include any sensitivity analysis. However, in this update we decided to perform two sensitivity analyses according to the following criteria:

1. Randomisation: Removal of the only quasi‐randomised study (Teichman 1995)

2. Eligibility: Removal of the studies in which the presence of relationship distress was not an inclusion criterion.

Summary of findings table

The first author (AB) prepared the 'Summary of findings' table for all comparisons, addressing the primary and secondary outcomes of depressive symptoms, persistence of depression, dropout rates and relationship distress. We rated the quality according to the GRADE Working Group grades of evidence (Higgins 2011). In the table, the primary and secondary outcomes are included. We calculated the assumed risk on the basis of the control groups' risk.

Results

Description of studies

See the Characteristics of included studies and the Excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

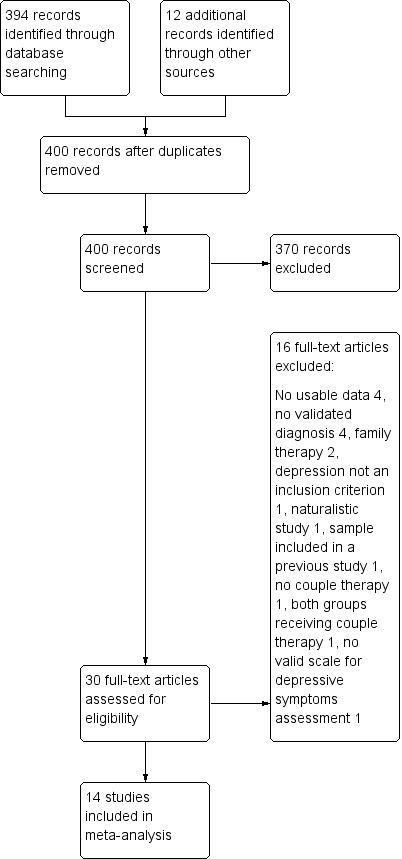

We conducted the first search for the first edition of this review in September 2005 and five further searches in March 2010, September 2014, May 2015, February 2016 and February 2018. After removing duplicates, we identified 400 records potentially relevant for our review. We excluded 370 records on the basis of information provided by titles and abstracts. We read the full text of 30 studies to assess their eligibility. We judged a total of 14 studies with 651 participants as eligible (Figure 1), adding six studies to those included in the earlier version.

1.

Study flow diagram

We sought information about unpublished or unclear data from the authors of the following studies: Beach 1992, Bodenmann 2008a, Dessaulles 2003, Emanuels 1996, Emanuels 1997, Jacobson 1991, Leff 2000, Seikkula 2012 and Teichman 1995. Beach 1992, Bodenmann 2008a, Seikkula 2012 and Teichman 1995 provided the requested information.

Included studies

Study design

All studies used a parallel group design. Thirteen of the included studies were randomised controlled trials. Teichman 1995 reported that assignment to treatment groups was random but restricted by therapist availability. Therefore, we considered this study as a quasi‐randomised trial.

Sample size

Fourteen studies randomised a total of 651 participants, ranging from 18 in Dessaulles 2003 and Foley 1989 to 83 in Lemmens 2009. The number of participants in each arm ranged between nine and 40.

Setting

All studies were conducted in outpatient mental health settings, although in Lemmens 2009, the treatment started during inpatient admission in some cases. Teichman 1995 was carried out in Israel, Leff 2000 in the United Kingdom, Bodenmann 2008a in Switzerland, Lemmens 2009 in Belgium, Seikkula 2012 in Finland, Dessaulles 2003 in Canada, two studies came from The Netherlands (Emanuels 1996; Emanuels 1997), and six studies came from the USA (Beach 1992; Cohen 2010; Denton 2012; Foley 1989; Jacobson 1991; Compton 2008).

Duration of follow‐up

In all studies, assessment was done at the end of the treatment. In addition, ten studies carried out follow‐up ranging from three months in Cohen 2010 and Dessaulles 2003 to two years (Leff 2000; Seikkula 2012). In four studies, follow‐up was longer than one year (Bodenmann 2008a; Leff 2000; Lemmens 2009; Seikkula 2012). However, in two studies it was not possible to ascertain whether the follow‐up period was intended after the end of treatment or did include the treatment itself (Lemmens 2009; Seikkula 2012). According to our definition, three studies (Bodenmann 2008a, Dessaulles 2003, Teichman 1995) provided data for short‐term follow‐up (6 months) and three studies (Bodenmann 2008a, Lemmens 2009, Seikkula 2012) provided data for long‐term follow‐up (15‐24 months).

Participants

Gender

Five studies included depressed women only in both experimental and control groups (Beach 1992; Cohen 2010; Denton 2012; Dessaulles 2003; Jacobson 1991). Eight studies included both men and women with depression (Bodenmann 2008a; Emanuels 1996; Emanuels 1997; Foley 1989; Leff 2000; Lemmens 2009; Seikkula 2012; Teichman 1995). In four studies, the proportion of women in the experimental group ranged from 50% (Bodenmann 2008a), to 64% (Lemmens 2009). In four studies, the proportion of women was reported for the full sample, without indicating the distribution by gender between the experimental and control groups. The proportion of women ranged from 53% (Emanuels 1996; Teichman 1995), to 72% (Foley 1989). Compton 2008 included couples with a depressed spouse, without giving any information on distribution by gender.

Age

The mean age of the participants was between 34 and 48 years, with the exception of the study by Compton 2008, which targeted older adults with a mean age of 68 years.

Diagnosis

Twelve studies included cases meeting criteria for major depressive disorder according to DSM‐III or DSM‐IV (Beach 1992; Bodenmann 2008a; Cohen 2010; Denton 2012; Dessaulles 2003; Emanuels 1996; Emanuels 1997; Jacobson 1991; Lemmens 2009; Compton 2008; Seikkula 2012; Teichman 1995). Among them, four studies included also participants with dysthymia (Beach 1992; Bodenmann 2008a; Cohen 2010; Teichman 1995). The study by Foley 1989 used the Research Diagnostic Criteria definition of depression (Spitzer 1978), and the study by Leff 2000 used the Present State Examination (Wing 1974).

Relationship distress

In seven studies, relationship distress was an inclusion criterion (Beach 1992; Denton 2012; Dessaulles 2003; Emanuels 1996; Foley 1989; Leff 2000; Compton 2008). In three studies that included either couples with and without relationship distress, the authors did not show the distribution according to this variable (Bodenmann 2008a; Cohen 2010; Lemmens 2009; Seikkula 2012). In the study by Jacobson 1991, in the treatment group 42% of couples showed relationship distress. In Emanuels 1997, couples were selected as showing no distress. In the study by Teichman 1995, the couples' status about relationship distress was not specified.

Recruitment

In five studies, the population was identified through a mix of newspaper advertisement and referral by general practitioners or mental health clinics (Dessaulles 2003; Emanuels 1996; Emanuels 1997; Jacobson 1991; Leff 2000); five studies recruited the participants from among those who sought treatment in mental health clinics (Cohen 2010; Foley 1989; Compton 2008; Seikkula 2012; Teichman 1995), two studies recruited participants from private practices (Bodenmann 2008a; Denton 2012). Lemmens 2009 included referrals to a psychiatric department of a university hospital and Beach 1992 relied on newspaper advertisements only.

Interventions

Intervention group

Although not all the papers described the treatment condition thoroughly, treatment models were defined as cognitive‐behavioural (Beach 1992; Bodenmann 2008a; Cohen 2010; Emanuels 1996; Emanuels 1997; Jacobson 1991; Compton 2008; Teichman 1995), emotion focused, based on integration of systemic and experiential approaches (Denton 2012; Dessaulles 2003), interpersonal (Foley 1989), and systemic (Leff 2000; Lemmens 2009; Seikkula 2012). The therapies in the Leff, Bodenmann and Denton studies were described according to manuals (Bodenmann 2004; Johnson 2004; Jones 1999). Denton assessed the therapists' adherence to the manual by using a fidelity scale (Denton 2009). The study by Emanuels 1997 was included, although the experimental treatment was defined by the authors as ‘spouse‐aided therapy’, not as couple therapy. However, spouse‐aided therapy is based on the concept of marital homeostasis and it has been defined as a form of couple therapy, because it was designed to enable spouses to identify and stop their contribution to the patient’s disorder (Hafner 1983). Moreover, papers on spouse‐aided therapy have been usually included in reviews of couple therapy (Denton 2003). Therefore, we concluded that this study met our inclusion criteria. In the study by Lemmens 2009, the experimental treatment was labelled as 'single family therapy'. However, a close examination of the paper showed that actually the intervention was couple therapy.

The treatment was delivered in weekly sessions, ranging between 15 and 20 in six studies (Beach 1992; Denton 2012; Dessaulles 2003; Emanuels 1996; Emanuels 1997; Teichman 1995). The study by Jacobson 1991 reported the number of 20 sessions, without specifying the interval between sessions. In the study by Compton 2008, the treatment was delivered in 26 weekly sessions, in the study by Bodenmann 2008a, in 10 biweekly sessions, in the study by Lemmens 2009, in six biweekly sessions plus one session after three months, in the study by Cohen 2010, in five weekly sessions. One study did not set up a fixed treatment length (Seikkula 2012), but set the minimum number of five sessions and reported that an average number of 11 sessions was delivered to the couple therapy group (range 5 to 33). The study by Leff 2000 reported a number of 12 to 20 sessions, without specifying the treatment length.

All studies reported that sessions were conducted by well‐trained expert therapists. Four studies assessed the treatment fidelity (Cohen 2010; Denton 2012; Dessaulles 2003; Jacobson 1991).

Control group

The control treatments were described as individual cognitive‐behavioural therapy in seven studies (Beach 1992; Bodenmann 2008a; Emanuels 1996; Emanuels 1997; Jacobson 1991; Lemmens 2009; Teichman 1995), and as interpersonal individual psychotherapy in the Foley 1989 study. Seikkula 2012 did not specify the individual psychotherapy model, but information from other papers by his research group led to the identification of a psychodynamic model. Two studies included, in addition to the individual therapy group, a no treatment/waiting list condition (Beach 1992; Teichman 1995). Three studies compared couple therapy with antidepressant drug therapy (Denton 2012; Dessaulles 2003; Leff 2000). The study by Denton was an augmentation study in which the couple therapy did receive antidepressant drugs as well. Cohen 2010 randomised the control group to the waiting list condition. Three studies also included an additional control condition not relevant to our analysis (Bodenmann 2008a; Jacobson 1991; Lemmens 2009).

In almost all studies, the number of sessions and treatment length were the same in the control group and in the intervention group. The only exception was the study by Bodenmann 2008a, in which the individual cognitive‐behavioural therapy was delivered in 20 weekly sessions, by contrast with 10 biweekly sessions of couple therapy.

All studies reported that individual therapy sessions were conducted by well‐trained expert therapists. Treatment fidelity was assessed in one study (Jacobson 1991).

Outcomes

We were able to extract data on mental health (i.e. depressive symptoms and persistence of depression), on study retention (i.e. dropouts), and on relationship distress.

For depression, seven studies used self‐rated questionnaires, i.e. the BDI (Beach 1992; Cohen 2010; Emanuels 1996; Emanuels 1997; Lemmens 2009; Teichman 1995), and the IDD (Dessaulles 2003). Three studies used clinician‐rated scales: Foley 1989 and Compton 2008 used the HRSD, and Denton 2012 the IDS‐C30. Four studies used both a self‐report (BDI) and a clinician rated (HRSD) scale (Bodenmann 2008a; Jacobson 1991; Leff 2000; Seikkula 2012). Three studies used recovery from depression as an outcome criterion (Beach 1998; Jacobson 1993; Teichman 1995), setting slightly different thresholds on BDI to define a participant as recovered. As far as relationship distress is concerned, the DAS was used in six studies (Beach 1992; Cohen 2010; Dessaulles 2003; Jacobson 1991; Compton 2008; Seikkula 2012). Foley 1989 used both the DAS and the LWMAS, but did not present usable data on the DAS global score. Therefore, we used data from the LWMAS for this analysis. Emanuels 1996 and Emanuels 1997 used the MMQ. Denton 2012 used the QMI. Lemmens 2009 assessed relationship distress by DAS in the study sample at baseline only. Leff 2000 included changes in relationship distress as an outcome criterion, but did not present data about this issue. Although values on relationship distress were usually presented as continuous, Beach 1992 and Jacobson 1991 computed a threshold to identify the full resolution of marital distress, thus allowing analyses of dichotomous data. Bodenmann 2008a used three measures to assess relational quality: Partnership Questionnaire (Hahlweg 1996), Dyadic Coping Inventory (Bodenmann 2008b) and Five‐Minute Speech Sample (Magaña 1986), failing to produce usable data for analysis.

Excluded studies

We excluded sixteen studies: one because the mothers' depression was part of a wider problem related to the presence of a disruptive child and the experimental group was treated by family therapy (Sanders 2000); three, reported by the same author (Waring 1990; Waring 1994; Waring 1995), because they did not give enough information to extract any data. We excluded the study by Jacobson 1993 because it reported a follow‐up of the sub‐sample of recovered participants already included in a previous clinical trial. We excluded the study by Friedman 1975 because primary diagnosis of depressive disorder was not settled according to an internationally validated diagnostic system, and it provided only poor description of the couple therapy offered. In the study of Dick‐Grace 1995, the intervention was cognitive therapy offered according to three modalities: individual, couple, and family, but useful data could not be extracted. Tilden 2010 used a naturalistic prospective design and the intervention was delivered during inpatient admission. The Swanson study tested an intervention entirely focused on the meaning of experience of miscarriage and did not adopt principles and methods of couple therapy (Swanson 2009). In Noorbala 2008, the intervention was cognitive therapy plus supportive therapy for infertility aiming at resolving symptoms in women undergoing infertility treatment. The comparison was between psychological treatment offered before and during infertility treatment. In Miller 2005, the experimental group was treated by family therapy in an inpatient setting. Moreover, data were given according to matching and mismatching of the assigned treatment to the clinicians' evaluation of the participants' needs and not according to randomisation. In four studies, no formal diagnosis of depression was made (Kröger 2012, Hajiheidari 2013; Hashemi 2017; Soltani 2014). In Shahverdi 2015, the primary outcome was improvement of general mental health, not depressive symptom level.

Ongoing studies

We did not identify any ongoing study.

Studies awaiting classification

We did not identify any study awaiting classification.

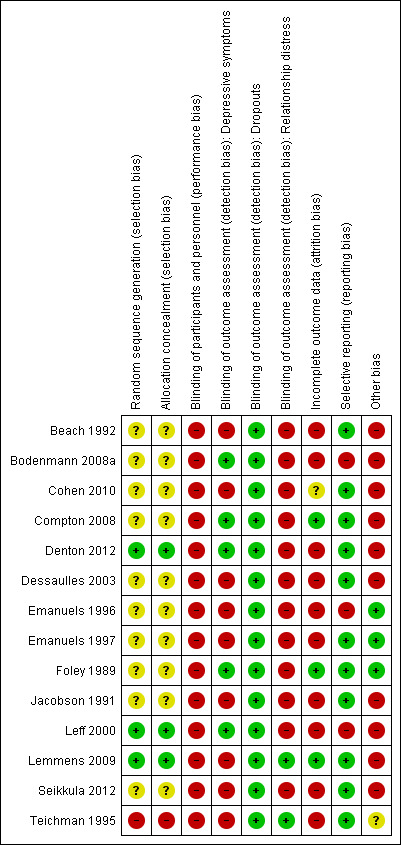

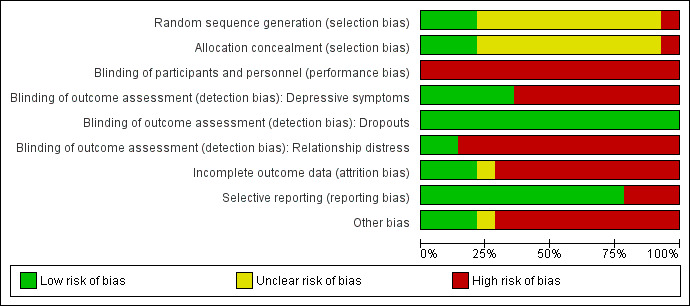

Risk of bias in included studies

See the Risk of Bias Table of each study in the Characteristics of included studies table and the summaries of the results in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation