Abstract

Background

People living in humanitarian settings in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) are exposed to a constellation of stressors that make them vulnerable to developing mental disorders. Mental disorders with a higher prevalence in these settings include post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive, anxiety, somatoform (e.g. medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS)), and related disorders. A range of psychological therapies are used to manage symptoms of mental disorders in this population.

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness and acceptability of psychological therapies versus control conditions (wait list, treatment as usual, attention placebo, psychological placebo, or no treatment) aimed at treating people with mental disorders (PTSD and major depressive, anxiety, somatoform, and related disorders) living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Wiley), MEDLINE (OVID), Embase (OVID), and PsycINFO (OVID), with results incorporated from searches to 3 February 2016. We also searched the World Health Organization (WHO) trials portal (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify any unpublished or ongoing studies. We checked the reference lists of relevant studies and reviews.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing psychological therapies versus control conditions (including no treatment, usual care, wait list, attention placebo, and psychological placebo) to treat adults and children with mental disorders living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises.

Data collection and analysis

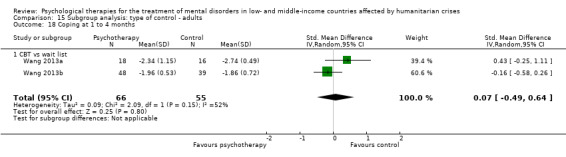

We used standard Cochrane procedures for collecting data and evaluating risk of bias. We calculated standardised mean differences for continuous outcomes and risk ratios for dichotomous data, using a random‐effects model. We analysed data at endpoint (zero to four weeks after therapy); at medium term (one to four months after therapy); and at long term (six months or longer). GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) was used to assess the quality of evidence for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety and withdrawal outcomes.

Main results

We included 36 studies (33 RCTs) with a total of 3523 participants. Included studies were conducted in sub‐Saharan Africa, the Middle East and North Africa, and Asia. Studies were implemented in response to armed conflicts; disasters triggered by natural hazards; and other types of humanitarian crises. Together, the 33 RCTs compared eight psychological treatments against a control comparator.

Four studies included children and adolescents between 5 and 18 years of age. Three studies included mixed populations (two studies included participants between 12 and 25 years of age, and one study included participants between 16 and 65 years of age). Remaining studies included adult populations (18 years of age or older).

Included trials compared a psychological therapy versus a control intervention (wait list in most studies; no treatment; treatment as usual). Psychological therapies were categorised mainly as cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) in 23 comparisons (including seven comparisons focused on narrative exposure therapy (NET), two focused on common elements treatment approach (CETA), and one focused on brief behavioural activation treatment (BA)); eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) in two comparisons; interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) in three comparisons; thought field therapy (TFT) in three comparisons; and trauma or general supportive counselling in two comparisons. Although interventions were described under these categories, several psychotherapeutic elements were common to a range of therapies (i.e. psychoeducation, coping skills).

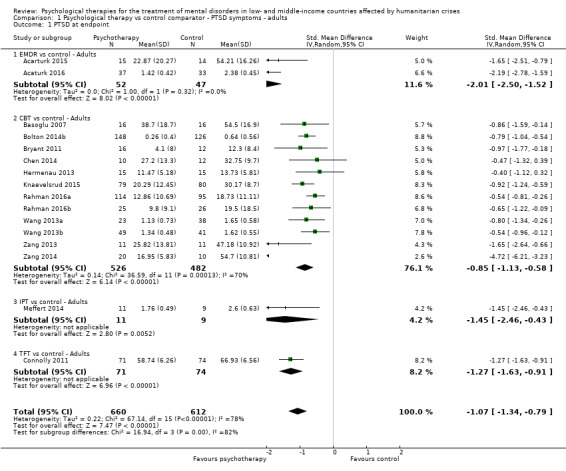

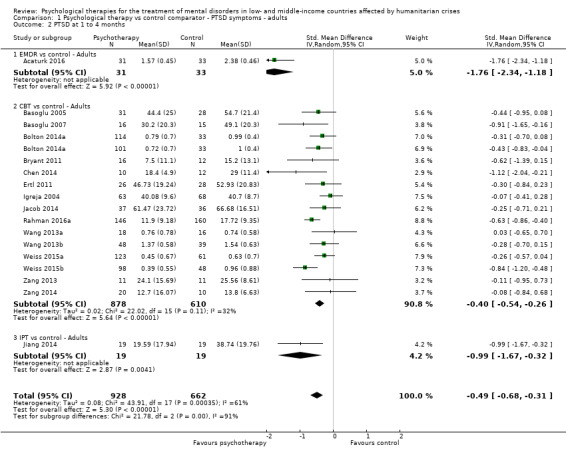

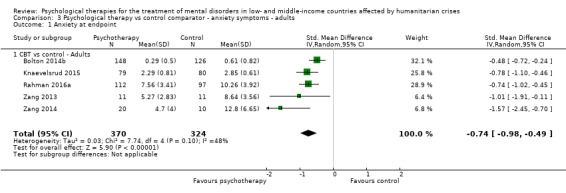

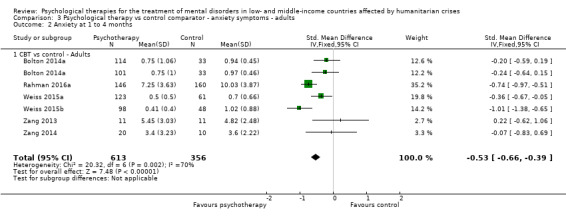

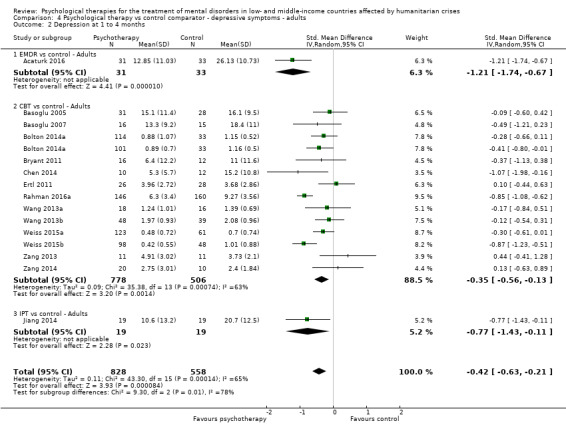

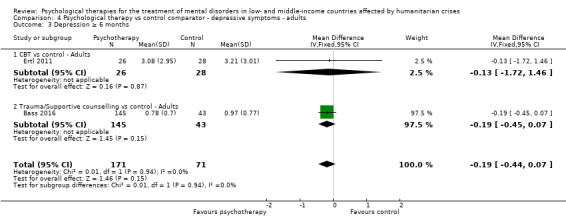

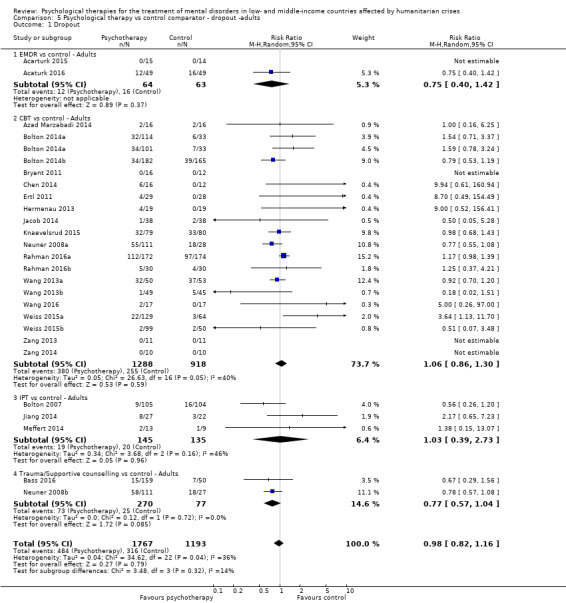

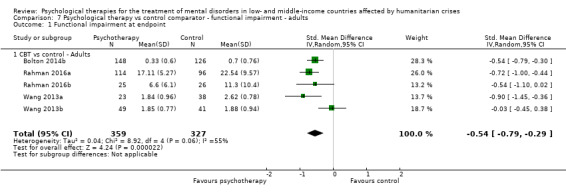

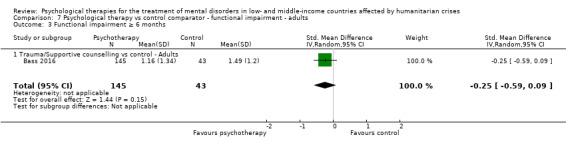

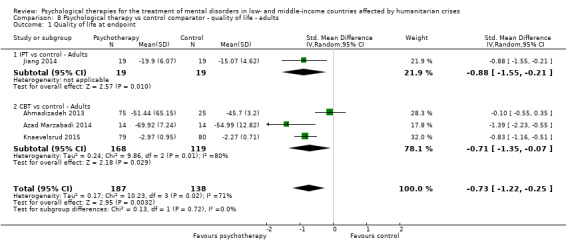

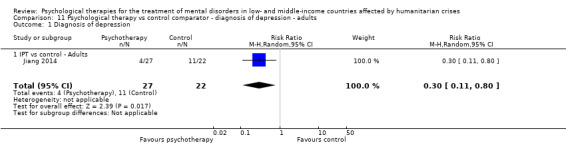

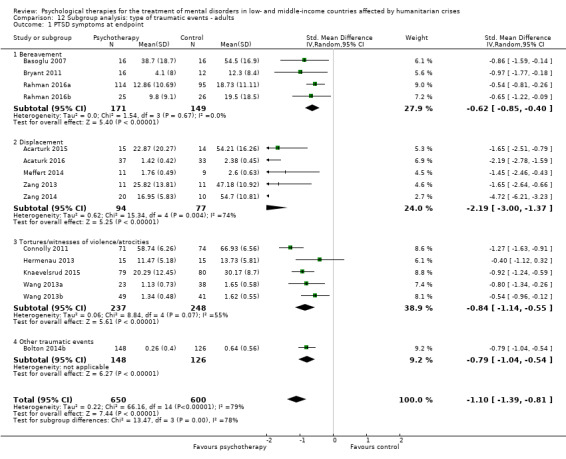

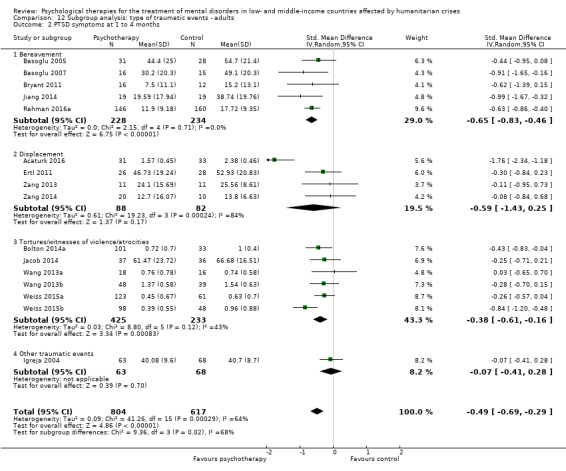

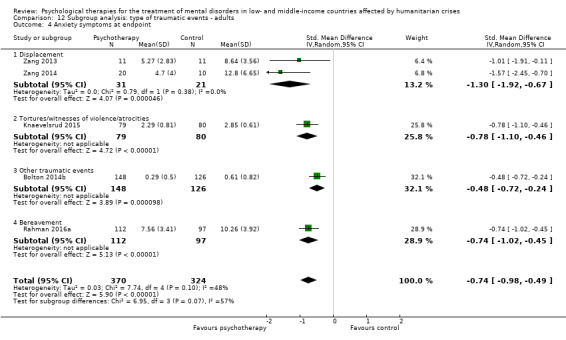

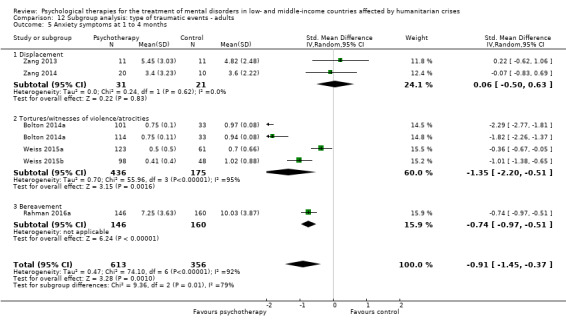

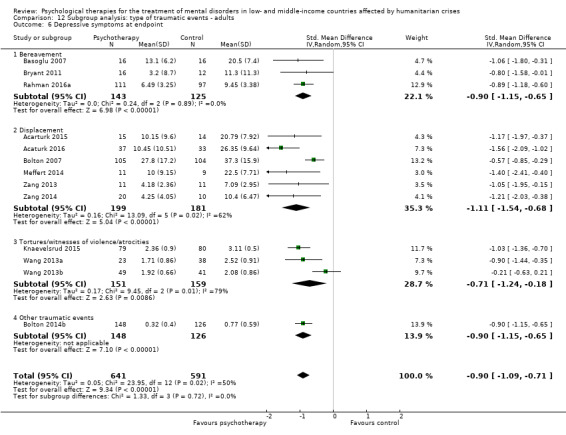

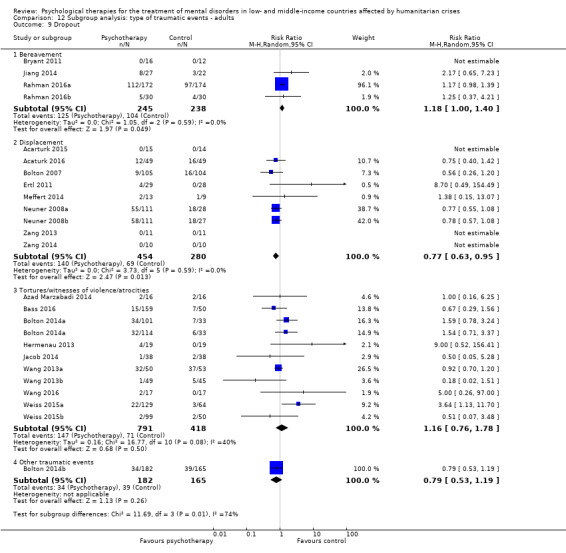

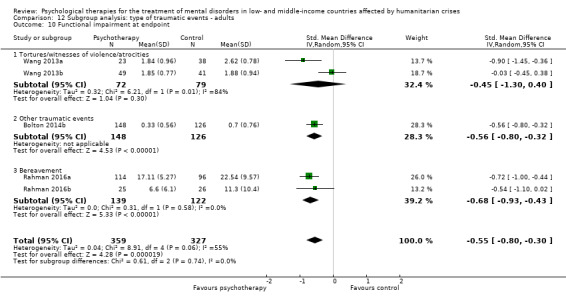

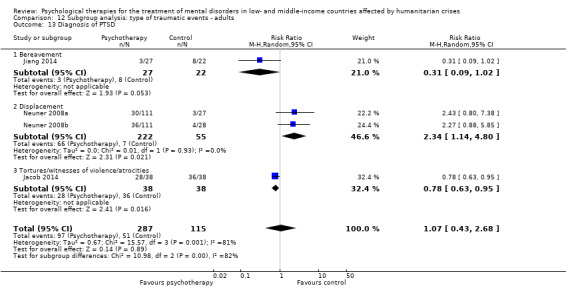

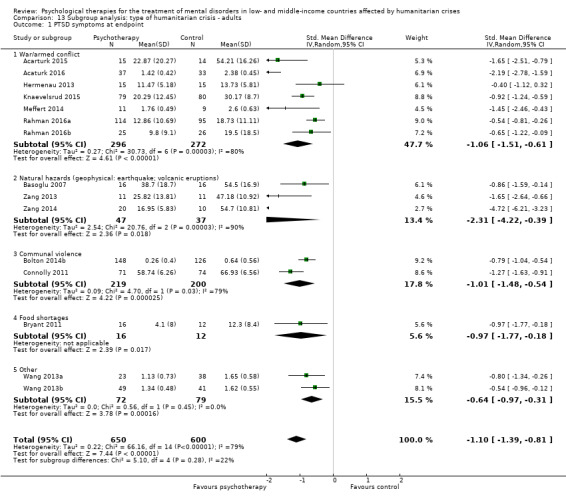

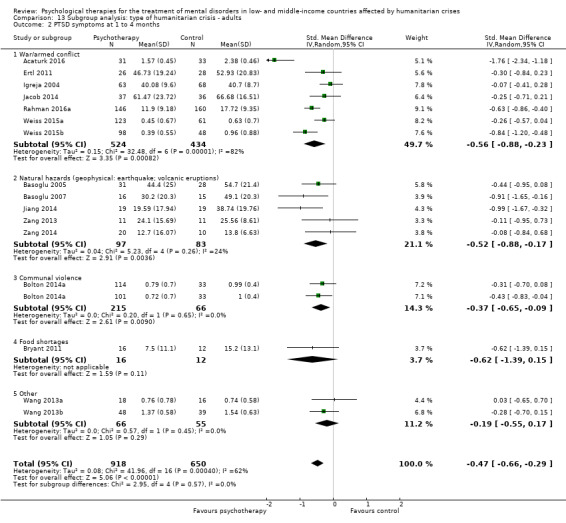

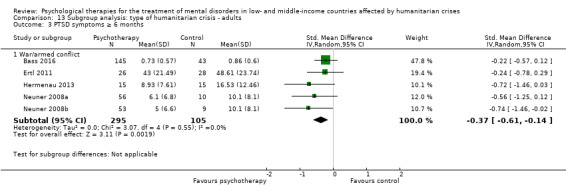

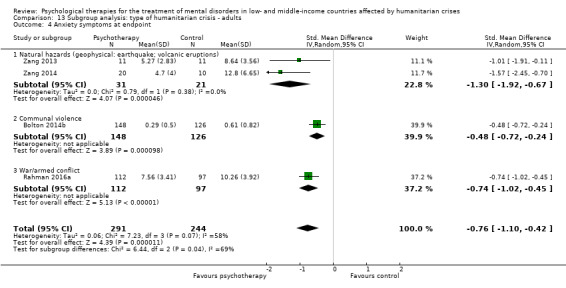

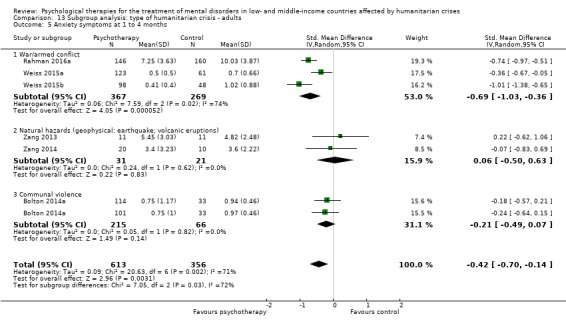

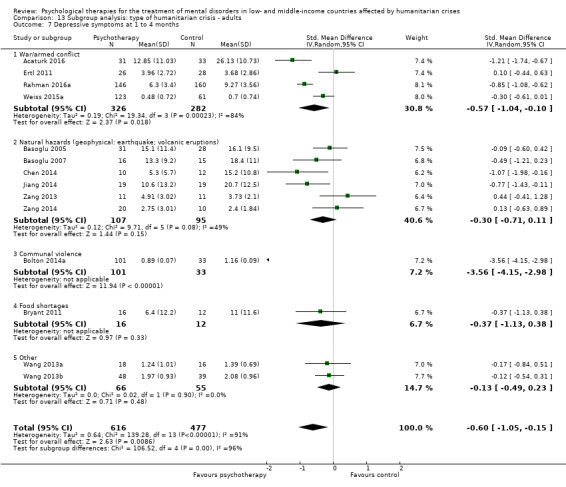

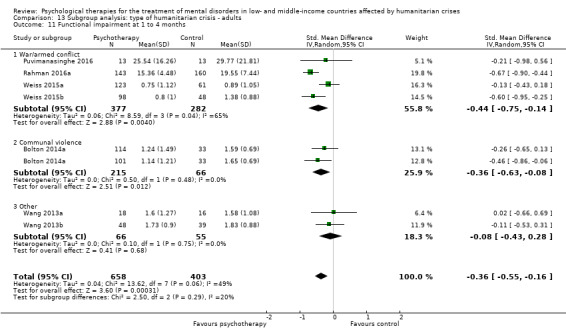

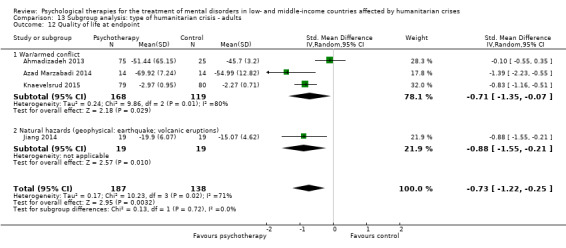

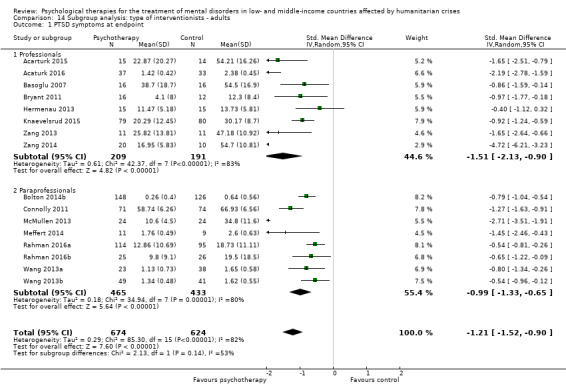

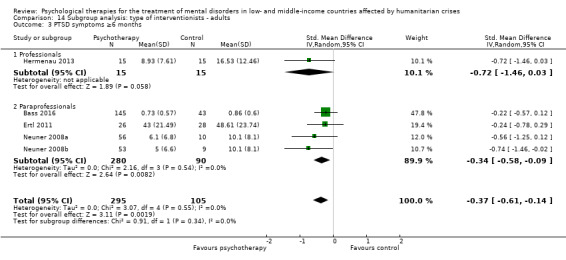

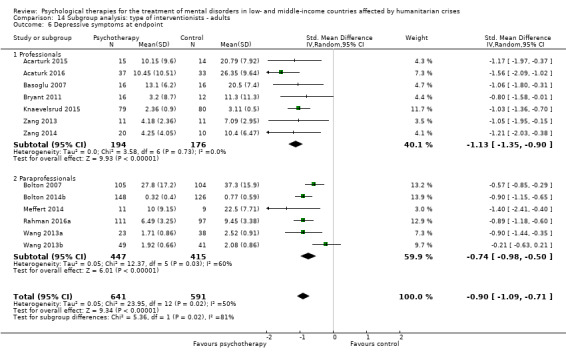

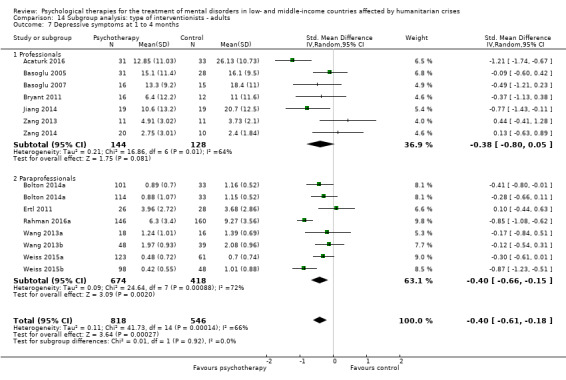

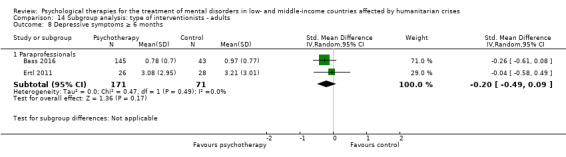

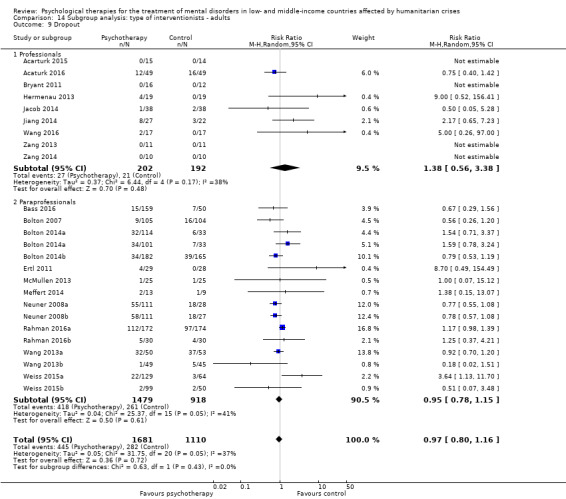

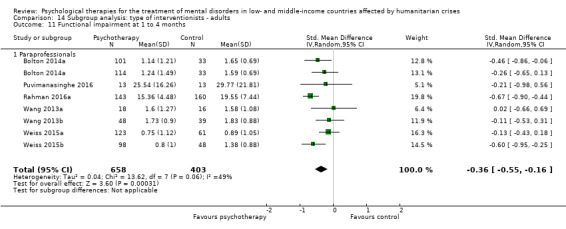

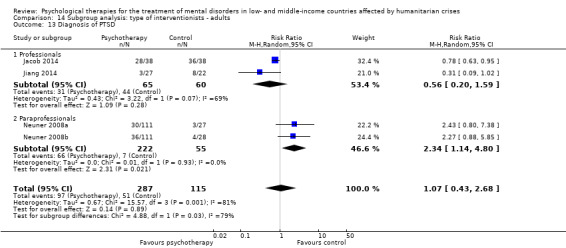

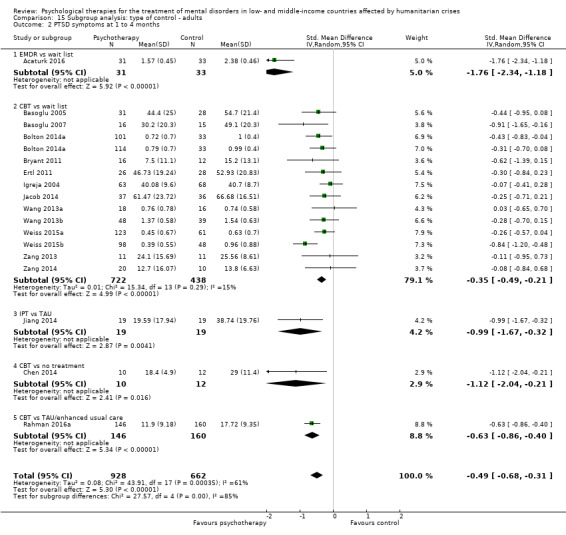

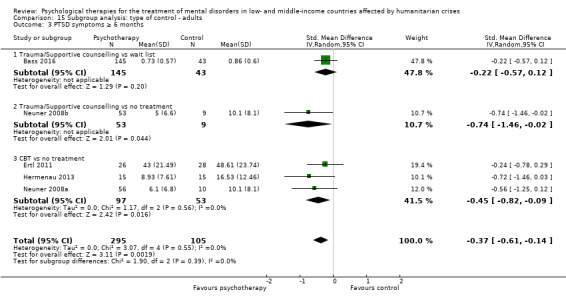

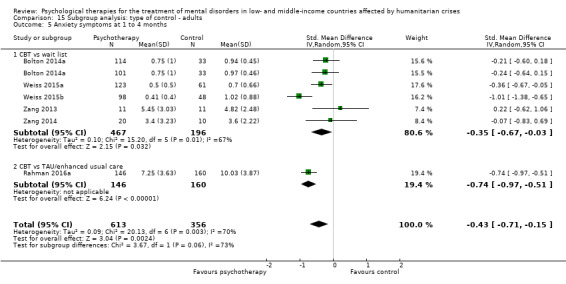

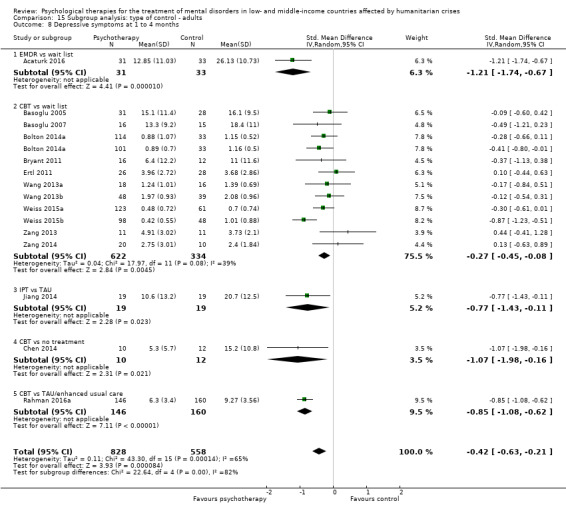

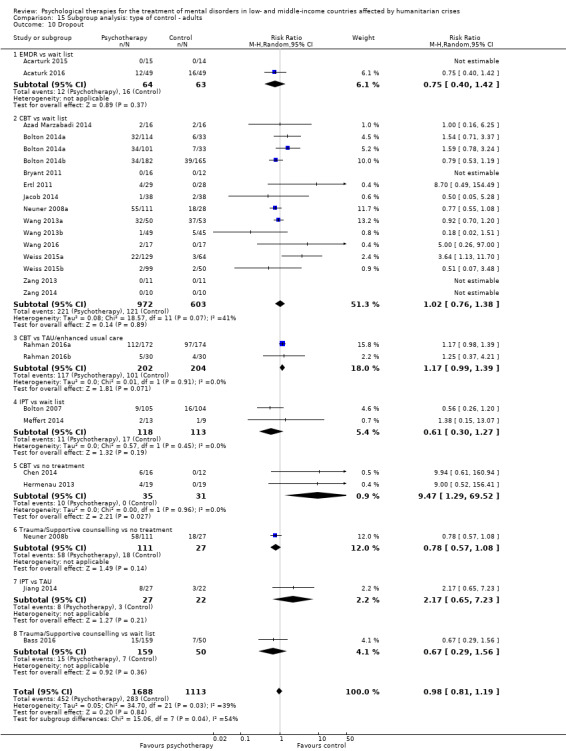

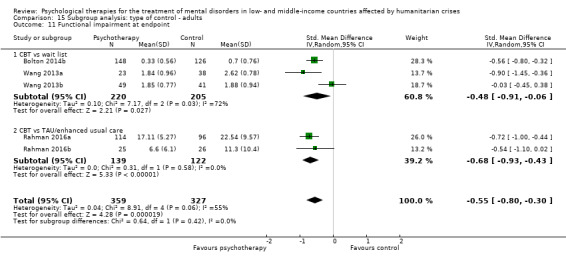

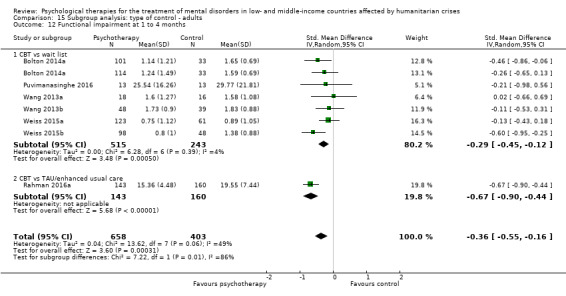

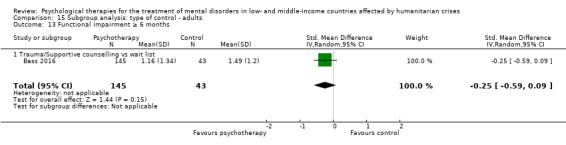

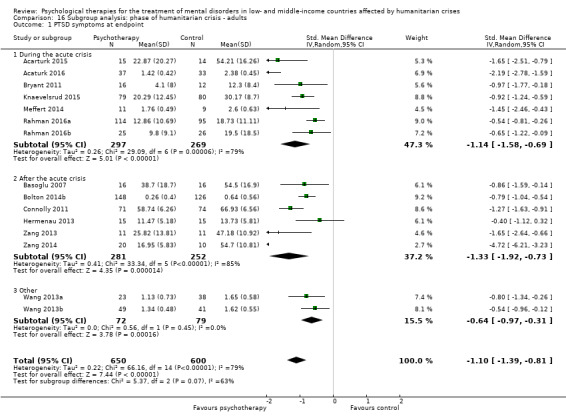

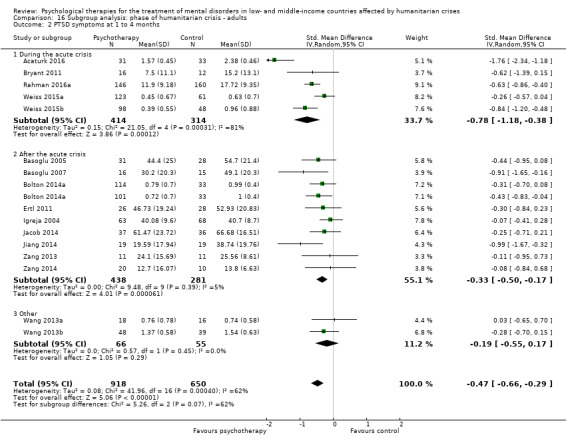

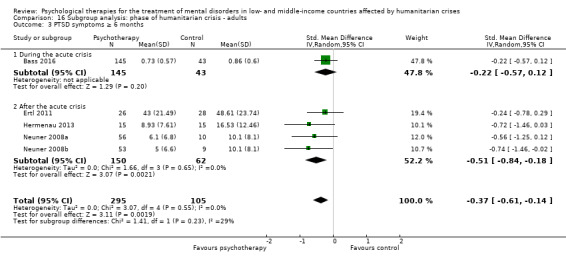

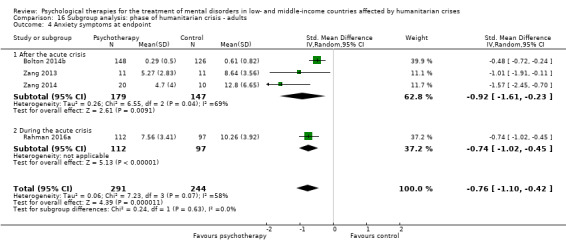

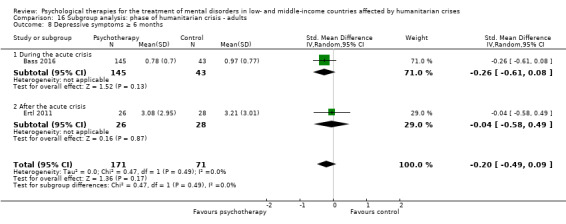

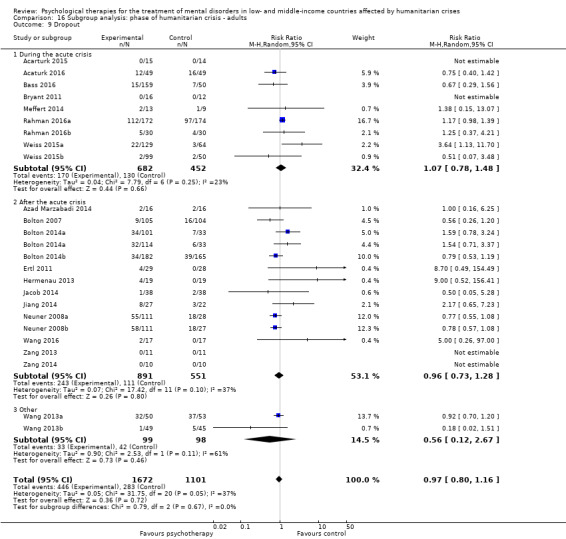

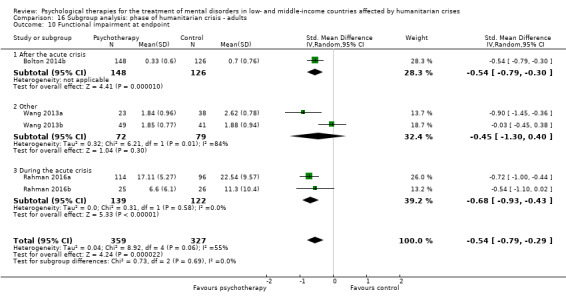

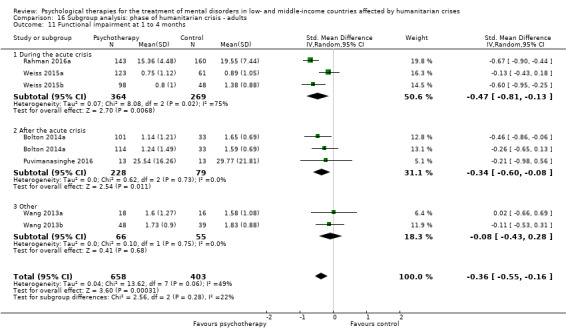

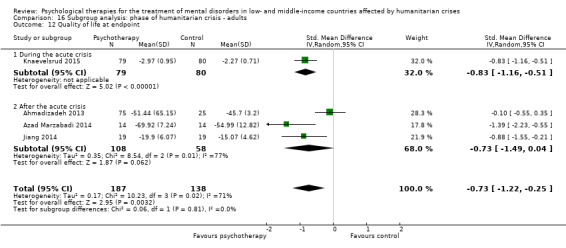

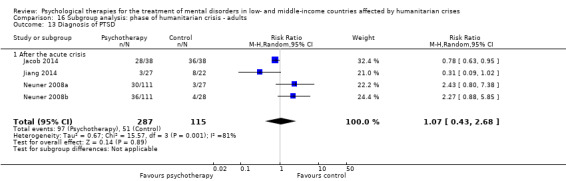

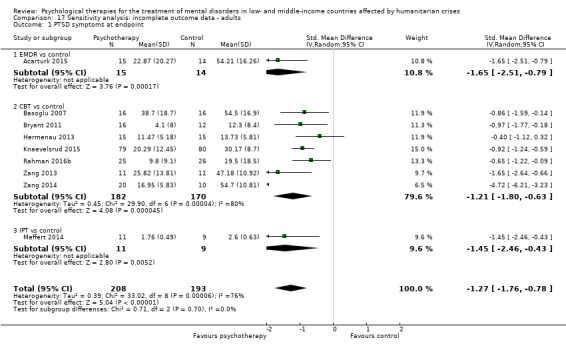

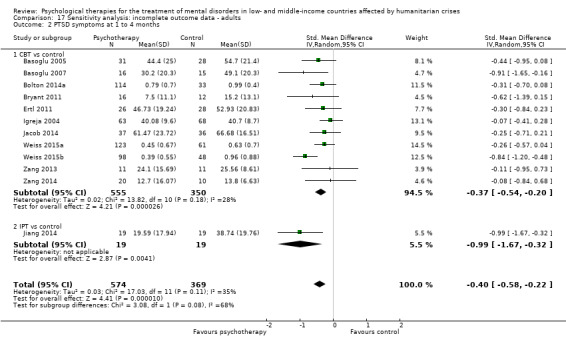

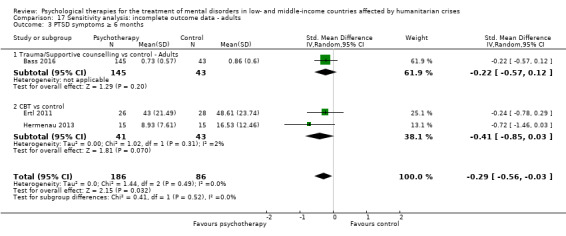

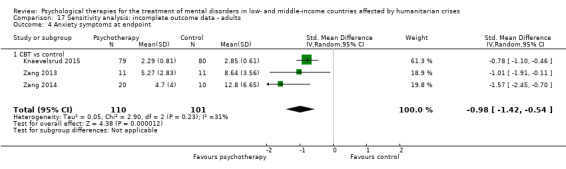

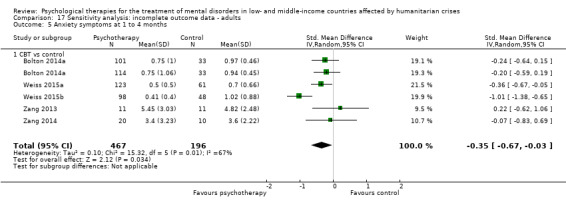

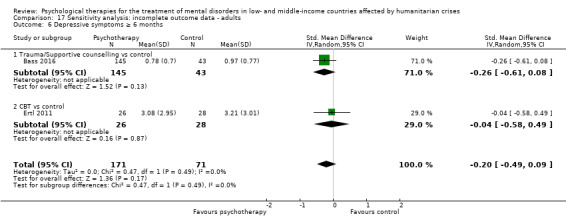

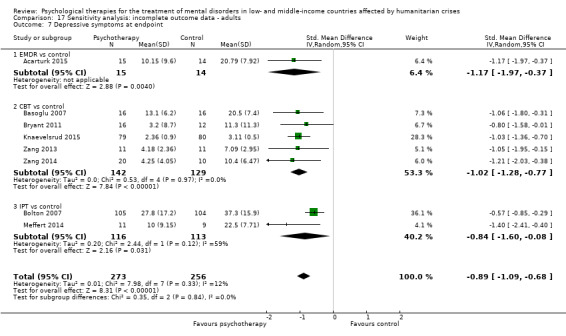

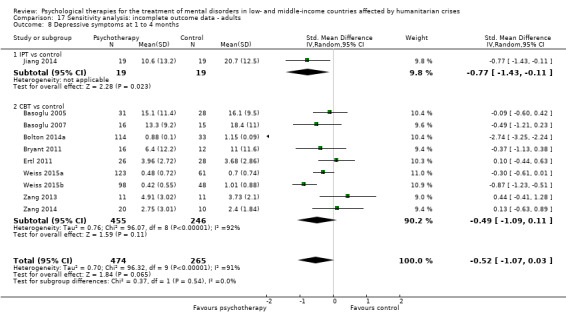

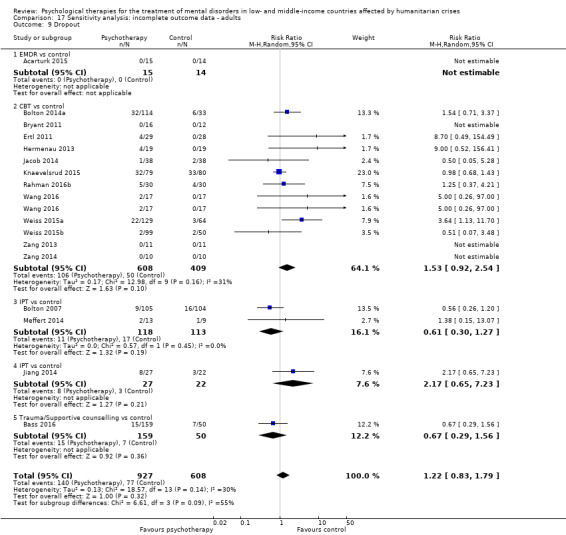

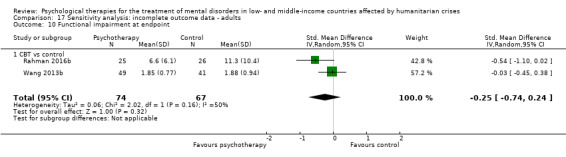

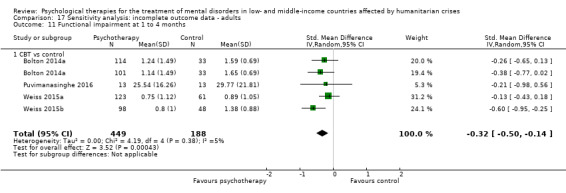

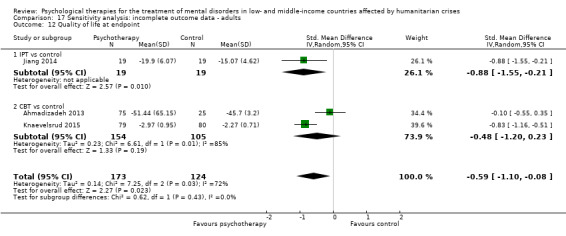

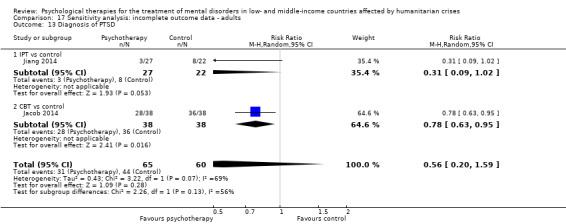

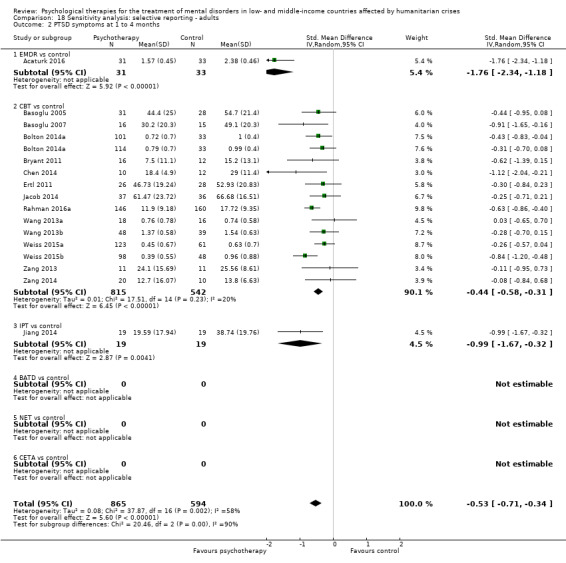

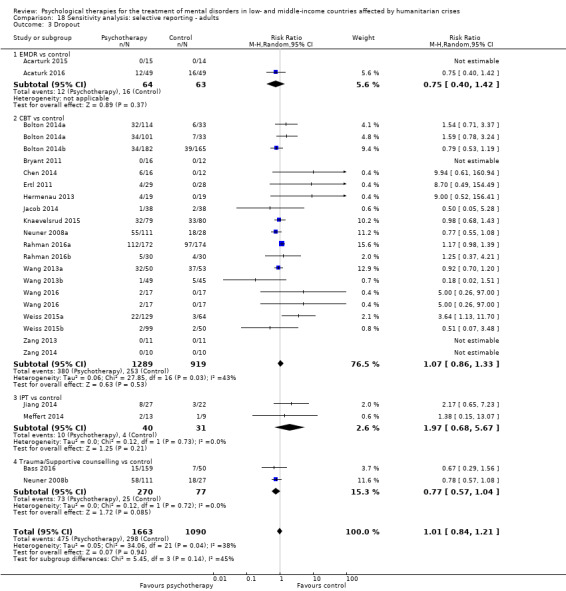

In adults, psychological therapies may substantially reduce endpoint PTSD symptoms compared to control conditions (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐1.07, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.34 to ‐0.79; 1272 participants; 16 studies; low‐quality evidence). The effect is smaller at one to four months (SMD ‐0.49, 95% CI ‐0.68 to ‐0.31; 1660 participants; 18 studies) and at six months (SMD ‐0.37, 95% CI ‐0.61 to ‐0.14; 400 participants; five studies). Psychological therapies may also substantially reduce endpoint depression symptoms compared to control conditions (SMD ‐0.86, 95% CI ‐1.06 to ‐0.67; 1254 participants; 14 studies; low‐quality evidence). Similar to PTSD symptoms, follow‐up data at one to four months showed a smaller effect on depression (SMD ‐0.42, 95% CI ‐0.63 to ‐0.21; 1386 participants; 16 studies). Psychological therapies may moderately reduce anxiety at endpoint (SMD ‐0.74, 95% CI ‐0.98 to ‐0.49; 694 participants; five studies; low‐quality evidence) and at one to four months' follow‐up after treatment (SMD ‐0.53, 95% CI ‐0.66 to ‐0.39; 969 participants; seven studies). Dropout rates are probably similar between study conditions (19.5% with control versus 19.1% with psychological therapy (RR 0.98 95% CI 0.82 to 1.16; 2930 participants; 23 studies, moderate quality evidence)).

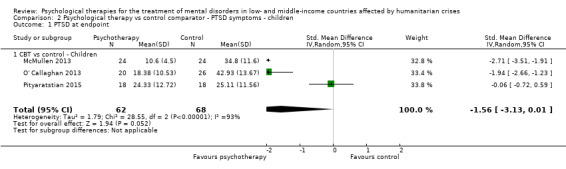

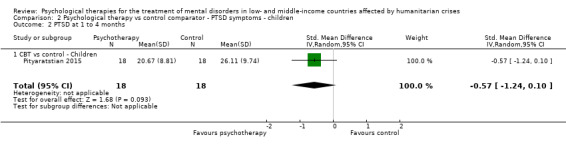

In children and adolescents, we found very low quality evidence for lower endpoint PTSD symptoms scores in psychotherapy conditions (CBT) compared to control conditions, although the confidence interval is wide (SMD ‐1.56, 95% CI ‐3.13 to 0.01; 130 participants; three studies;). No RCTs provided data on major depression or anxiety in children. The effect on withdrawal was uncertain (RR 1.87 95% CI 0.47 to 7.47; 138 participants; 3 studies, low quality evidence).

We did not identify any studies that evaluated psychological treatments on (symptoms of) somatoform disorders or MUPS in LMIC humanitarian settings.

Authors' conclusions

There is low quality evidence that psychological therapies have large or moderate effects in reducing PTSD, depressive, and anxiety symptoms in adults living in humanitarian settings in LMICs. By one to four month and six month follow‐up assessments treatment effects were smaller. Fewer trials were focused on children and adolescents and they provide very low quality evidence of a beneficial effect of psychological therapies in reducing PTSD symptoms at endpoint. Confidence in these findings is influenced by the risk of bias in the studies and by substantial levels of heterogeneity. More research evidence is needed, particularly for children and adolescents over longer periods of follow‐up.

Plain language summary

Talking therapy for the management of mental health in low‐ and middle‐income countries affected by mass human tragedy

Why is this review important?

Adults and children and adolescents living in humanitarian contexts (such as in the aftermath of a crisis triggered by natural hazards) in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) are exposed to multifaceted stressors that make them more vulnerable to developing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression, anxiety, and other negative psychological outcomes.

Who will be interested in this review?

People who are directly exposed to humanitarian crises and their families and caregivers will be interested in this review, as will healthcare professionals and paraprofessionals working both in LMICs and in high‐income settings. Moreover, policy makers, humanitarian programming staff, guideline developers, and agencies (such as non‐governmental organisations (NGOs)) working in health and non‐health sectors (e.g. those providing protection to populations living in humanitarian contexts) may be interested in this review.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

Are psychological therapies more effective than control comparator conditions (including no treatment, usual care, wait list, attention placebo, and psychological placebo) in reducing (symptoms of) PTSD and major depressive, anxiety, and somatoform and related disorders (conditions in which people present physical symptoms (e.g. pain) that cannot be explained medically) in people of any age, gender, or religion living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises?

Which studies were included in this review?

Review authors searched databases up to February 2016 to find and include all relevant published and unpublished trials. Studies had to include children and/or adults living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises. Studies also had to be randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which means that people were allocated at random (by chance alone) to receive the treatment or comparator condition.

We included 33 trials with a total of 3523 participants that examined a range of psychological therapies.

What does evidence presented in the review tell us?

In adults, low‐quality evidence shows greater benefit from psychological therapies than from control comparators in reducing (symptoms of) PTSD, major depression, and anxiety disorders. This evidence supports the approach of providing psychological therapies to populations affected by humanitarian crises, although we identified no studies that looked at the effectiveness or acceptability of psychological therapies for depressive and anxiety symptoms beyond six months. Only a small proportion of included trials reported data on children and adolescents, which provided very low‐quality evidence of greater benefit derived from psychological treatments. With regard to acceptability, moderate‐ to low‐quality evidence suggests no differences in dropout rates among adults and children and adolescents. Reviewers found no studies evaluating psychological treatments for (symptoms of) somatoform disorders or medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) in adults, nor in children or adolescents, respectively.

What should happen next?

Researchers should conduct higher‐quality trials to further evaluate the effectiveness of psychological therapies provided over longer periods to adults and to children and adolescents. Ideally, trials should be randomised, should use culturally appropriate and validated instruments to evaluate outcomes, and should assess correlates of reductions in treatment effects over time; in addition, researchers should make every effort to ensure high rates of follow‐up beyond six months after completion of therapy.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The term 'humanitarian crises' is used to refer to a broad group of emergencies, including those triggered by natural, technological, and industrial hazards, as well as armed conflicts (Tol 2011). Humanitarian crises are commonly defined as rapid and serious deteriorations in safety, with numerous victims or numerous people whose lives are in danger or who are in great distress, along with substantial material destruction, forced displacement or population movement, and great difficulty or incapacity of institutional management in handling the situation (Josse 2009). The most commonly affected populations live in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) (Guha‐Sapir 2014; Themner 2014). Humanitarian crises have a wide range of impacts on the mental health of individual survivors. Mental health consequences may include improved mental health (e.g. through post‐traumatic growth); maintained mental health and wellbeing despite exposure to adversity (i.e. resilience); transient acute stress reactions and bereavement; and a range of mental disorders (Kane 2017).

Mental health epidemiology in humanitarian settings has most commonly focused on disorders and conditions specifically associated with exposure to stressors, such as post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In classifying outcomes of interest, we followed the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐V) classification. Diagnostic criteria for PTSD include a history of exposure to a traumatic event that meets specific stipulations and symptoms from each of four symptom clusters: intrusion, persistent avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity associated with the traumatic event (APA 2013; O'Donnell 2014).

Moreover, studies have identified heightened prevalence of disorders that can occur in the absence of exposure to stressors, such as:

anxiety disorders, which include disorders that share features of excessive fear and anxiety and related behavioural disturbances;

depressive disorders, which are characterised by the presence of sad, empty, or irritable mood, and accompanied by somatic and cognitive changes that affect the individual's capacity to function (APA 2013); and

somatic symptom and related disorders (this is an umbrella term introduced in the DSM‐V that includes the conditions listed in the DSM‐IV as somatoform disorders), including medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) (APA 2013; van Dessel 2014).

Steel et al conducted a meta‐analysis of epidemiological studies with adult conflict‐affected populations across 181 surveys in 40 countries. In a subset of rigorous studies, prevalence rates were 15.4% for PTSD (30 studies using representative sampling and diagnostic interviews) and 17.3% for depression (26 studies using representative sampling and diagnostic interviews). Predictors of PTSD were torture, cumulative exposure to potentially traumatic events (PTEs), time since conflict, and level of political terror in the territory. For depression, predictors were number of PTEs, time since conflict, torture, and residency status (Charlson 2016).

Description of the intervention

The World Health Organization (WHO) Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) has developed guidelines specifically focused on the needs of people living in LMICs (WHO 2013; WHO 2016). Pharmacological treatments are available for individuals with PTSD (Hoskins 2015). However, psychological therapies, together with other types of psychosocial interventions, are generally considered the first‐line option according to mhGAP guidelines (e.g. for management of acute stress, PTSD, and bereavement) (WHO 2013; WHO 2016).

Psychological therapies are widely used in the management of (symptoms of) PTSD, anxiety, depression, somatoform disorders, MUPS, and related disorders, and are recommended in the mhGAP Intervention Guide (WHO 2016). mhGAP guidelines contain both recommendations on psychological interventions for adults and a specific section dedicated to treatment of children and adolescents. Different types of psychological therapies are available, such as different forms of cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT), including CBT with a trauma focus (CBT‐T), Brief Behavioural Activation treatment (BA), narrative exposure therapy (NET), and the common elements treatment approach (CETA); eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR); interpersonal therapy (IPT); thought field therapy (TFT); and psychodynamic therapy.

CBT is often used as an umbrella term that encompasses a wide range of therapeutic approaches, techniques, and systems that share some common elements. CBTs include psychological treatments that combine cognitive components (aimed at thinking differently, for example, by identifying and challenging unrealistic negative thoughts) and behavioural components (aimed at doing things differently, for example, by helping the person to participate in more rewarding activities) (WHO 2016). CBTs assume that psychopathology, or emotional disturbance, is the result of biased cognitions and unhelpful behaviour; these treatments aim to improve symptoms of anxiety by addressing these unhelpful cognitions and behaviours. They are used to treat individuals with depression and somatoform disorders (Allen 2010), and they are used in children and adolescents as well as in adults (James 2015; Olthuis 2015; Watts 2015).

CBT has been applied to all disorders of interest in this review (with various modifications/various emphases for different disorders).

These include the following.

-

CBT‐T (cognitive‐behavioural therapy with a trauma focus): based on the idea that people who were exposed to a traumatic event have unhelpful thoughts and beliefs related to that event and its consequences. These thoughts and beliefs result in unhelpful avoidance of reminders of the event and a sense of current threat. Treatment usually includes exposure to those reminders and to challenging unhelpful trauma‐related thoughts or beliefs (WHO 2016).

Among CBT‐Ts, NET (narrative exposure therapy) is a standardised short‐term approach to trauma‐related disorders based on the patient's construction of a narrative about his/her life from birth up to the present situation with focus on detailed exploration of the traumatic experience, while combining testimony therapy and CBT‐T exposure elements (Schauer 2011).

CETA (common elements treatment approach): transdiagnostic treatment approach specifically designed to be delivered in low‐resource settings, which allows therapists to combine evidence‐based treatment elements depending on individual symptom presentation, including psychoeducation, anxiety management, cognitive coping/restructuring, and elements of exposure (Murray 2014).

BA (Brief Behavioural Activation): a manualised type of CBT that is focused on reducing depressive symptoms by helping individuals engage in positive activities on a daily basis, according to the values and goals of that individual in multiple life areas (i.e. relationships, career, and spirituality) (Jakupcak 2010).

-

EMDR (eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing): based on the idea that negative thoughts, feelings, and behaviours result from unprocessed memories of traumatic events. Treatment involves standardised procedures that include focusing simultaneously on:

associations of traumatic images, thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations; and

bilateral stimulation that most commonly occurs in the form of repeated eye movements (WHO 2016).

IPT (interpersonal psychotherapy): helps people understand their feelings as useful signals of interpersonal encounters (Markowitz 2014). IPT is considered an evidence‐based therapy for major depression that focuses specifically on the connection between depressive symptoms and interpersonal problems (Dennis 2007;WHO 2016); it has also been evaluated in the treatment of anxiety disorders, PTSD, and somatoform and related disorders (Markowitz 2015; van Dessel 2014).

TFT (thought field trauma): brief trauma intervention that utilises a sequence of self‐tapping to stimulate specific acupuncture points while recalling a traumatic event or cue. It facilitates the relaxation response while the person experiences exposure to the problem by simply thinking about the problem (Callahan 2000).

Psychodynamic therapy: focused on integration of the traumatic experience into the life experience of the person as a whole, often considering childhood issues as important (Brom 1989).

Other interventions, such as generic, problem‐solving, or trauma‐focused counselling: commonly less structured than psychotherapies and targeting specific needs and problems as expressed by patients. Interventions may also focus on rebuilding skills and coping strategies in social situations while improving communication and social interaction skills, to reduce stress in everyday life (WHO 2016).

How the intervention might work

These different treatments are based on their own various theoretical models describing putative treatment mechanisms. Previous reviews of psychological treatments for PTSD ‐ Bisson 2013 and Gillies 2016, depression ‐ Cuijpers 2009,Gloaguen 1998,Rigmor 2010, and Watanabe 2007, and anxiety disorders ‐ Abbass 2014 found psychological treatments to be effective. For PTSD in adults, treatments that included specific elements focused on trauma were more effective than treatments that did not include such elements (Bisson 2013). In children and adolescents, CBT interventions appeared to be more effective than control conditions for PTSD (Gillies 2016), depression (Watanabe 2007), and anxiety disorders (James 2015).

For all clinical conditions considered in this review, the mechanism of action of CBT had been explored and categorised as follows.

Cognitive mechanisms: increase in adaptive cognitions that may occur through restructuring of maladaptive thought patterns, correction of misinterpretations, changes in attentional focus, and development of adaptive coping thoughts.

Behavioural mechanisms: increase in adaptive behavioural responses that may occur through habituation, extinction of maladaptive responses, behavioural activation, associative learning, and reinforcement of adaptive responding.

Physiological mechanisms: normalisation of physiological arousal that may occur through habituation, incompatible response training, or changes in autonomic nervous system activity (DePaulo 2014).

CBT for depression is based on the assumption that the person's mood is related to his or her patterns of thought (thoughts tend to be unrealistic or distorted); therefore CBT can help a person learn to recognise negative patterns of thought, to evaluate their validity, and to replace these thoughts with different and functional ways of thinking (Beck 1979;WHO 2016). CBT for anxiety addresses negative patterns/distortions related to the way we look at the world and at ourselves. This involves a cognitive component (focused on how negative thoughts, or cognitions, contribute to anxiety) and a behavioural component (focused on behaviours that trigger anxiety). CBT is based on the premise that fear and anxiety are learnt responses that can be 'unlearnt' (James 2015). CBT has also been used for somatoform‐related disorders (van Dessel 2014).

CBT‐T is based on the idea that people with PTSD have unhelpful thoughts and beliefs related to a traumatic event and its consequences, and that these beliefs result in unhelpful avoidance of reminders of the event with a sense of current threat. Cognitive‐behavioural interventions with a trauma focus usually work with imaginal and/or in vivo (real life) exposure treatment and/or direct challenging of unhelpful trauma‐related thoughts and beliefs (WHO 2013). CBT‐T protocols usually involve different components such as psychoeducation, anxiety management, exposure, and cognitive restructuring (Bisson 2013). NET is a type of CBT‐T that is thought to contextualise the particular associative elements of the fear network ‐ the sensory, affective, and cognitive memories of trauma ‐ to understand and process the memory of a traumatic event in the course of the patient's life. In NET, the patient (with the assistance of the therapist) constructs a chronological narrative of his life story with a focus on traumatic experiences. Fragmented reports of these traumatic experiences will be transformed into a coherent narrative. Empathic understanding, active listening, congruency, and unconditional positive regard are key components of the therapist’s behaviour (Schauer 2011). CETA is a transdiagnostic approach that tailors the selection of elements that are common to evidence‐based psychotherapies to each individual's symptom profile. It consists of delivering specific components tailored to the individual's needs and culture. Components are engagement, psychoeducation, anxiety management, cognitive restructuring, imaginal gradual exposure, in vivo exposure, safety, and alcohol use assessment (Murray 2014).

BA is a structured CBT program for depression that reinforces positive activities in different areas of an individual's life (e.g. talking and exchanging ideas with others; interacting with and helping other; working). Engagement in these activities is initially supported by the therapist (actively) and is intended to become more intrinsic as activities lead to more positive experiences and the satisfaction that comes from living according to one's own goals and values.

TFT is a brief treatment that identifies feelings elicited by thinking about the problem and asking the patient to rate the emotional intensity that he/she feels when thinking about the problem by stimulating selected acupoints on the surface of the skin in a sequence that is specific to the identified emotions. The theory behind TFT is that precisely encoded information becomes activated when an individual thinks about a problem, either subconsciously or consciously (Callahan 2000).

EMDR is based on the idea that negative thoughts, feelings, and behaviours are the result of unprocessed memories. Treatment involves standardised procedures that include simultaneous focus on spontaneous associations of traumatic images, thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations; and bilateral stimulation, most commonly in the form of repeated eye movements (WHO 2013).

IPT is an evidence‐based treatment for individuals with major depression. It is designed to help a person identify and address problems in relationships with family, friends, partners, and other significant people (WHO 2016). IPT addresses the person’s ability to assert his/her needs and wishes in interpersonal encounters, to validate the person’s anger as a normal interpersonal signal and to encourage its efficient expression, and to take appropriate social risks. Reviewing the person's accomplishments during treatment helps him/her feel more capable and independent (Markowitz 2004).

Psychodynamic therapies aim to resolve inner conflicts arising from the traumatic event by placing emphasis on the unconscious mind. These therapies have also been used in depression, anxiety disorders, and somatic symptom and related disorders.

Why it is important to do this review

Humanitarian crises impact a large part of the world's population, often affecting populations already beset by adversity (e.g. poverty, gender‐based violence, social marginalisation). For example, the Machel report states that just over 1 billion children globally are affected by armed conflicts (UN General Assembly 1996; UNICEF 2009). It is important to note that given the known high burden associated with mental disorders and conditions in these populations, application of treatments with known efficacy has the potential to improve individual functioning while widening wellbeing and economic productivity.

Mental health and psychosocial support interventions are becoming a standard part of humanitarian programmes. Although this was an ideologically divided field, agreement on best practices appears to be growing, as evidenced by international consensus‐based documents (IASC 2007; The Sphere Project 2011). These documents advocate for multi‐layered systems of care intended to address the diversity of mental health and psychosocial needs in humanitarian settings. As part of such systems of care, pharmacological and psychological treatments are intended to target more severe mental health problems. This review focuses on psychological therapies, given conflicting views in current guidelines on the benefits of pharmacological approaches for conditions specifically related to stress, such as PTSD (Forbes 2010;WHO 2013). In two parallel reviews, we will evaluate the effectiveness of psychosocial approaches in preventing mental disorders and promoting (positive aspects of) mental health and psychosocial well‐being.

Bisson et al conducted a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of individual CBT‐T, EMDR, CBT without a specific trauma focus, and other therapies (supportive therapy, non‐directive counselling, psychodynamic therapy, and present‐centred therapy), as well as group CBT‐T and group CBT for PTSD (70 studies; n = 4761) (Bisson 2013). Researchers found that CBT‐T and EMDR were effective in reducing clinician‐rated PTSD. Individual CBT‐T, EMDR, and CBT appeared to be equally effective immediately post treatment, and some evidence shows that CBT‐T and EMDR were superior to CBT at follow‐up. Individual CBT‐T, EMDR, and CBT are more effective than other therapies. A recent Cochrane review on PTSD in children and adolescents included 51 studies (n = 6201) with participants exposed to various kinds of traumatic events. Trial authors found evidence to support the effectiveness of psychological therapies for reducing PTSD in children and adolescents (Gillies 2016). However, even though informative, these reviews were not specifically focused on humanitarian settings in LMICs.

In summary, given the broad impact of humanitarian settings on mental health, this review aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness and acceptability of psychological treatments, across a range of disorders in children and adolescents as well as adults. In conducting this systematic review, we will follow the protocol that we published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Purgato 2015).

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness and acceptability of psychological therapies versus control conditions (wait list, treatment as usual, attention placebo, psychological placebo, or no treatment) aimed at treating people with mental disorders (PTSD and major depressive, anxiety, somatoform, and related disorders) living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs. We also included in the review trials employing a cross‐over design ‐ whilst acknowledging that this design is rarely used in psychological treatment studies ‐ using data from the first randomised stage only. We excluded quasi‐randomised trials, such as those allocating treatments on alternate days of the week. We considered cluster‐randomised trials as eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

We included participants of any age, gender, ethnicity, or religion. We conducted separate meta‐analyses for studies with children and adolescents (younger than 18 years) and for adults (18 years of age or older) on different trial outcomes. We categorised studies including mixed populations of children and adults according to the mean age of participants.

We have decided for the first version of this review to consider children and adolescents, as well as adults, according to the methods followed by Tol 2011.

Setting

We considered studies conducted in LMICs in humanitarian settings, that is, in contexts affected by armed conflicts or by disasters associated with natural, technological, or industrial hazards. We used World Bank criteria for categorising a country as low‐ or middle‐income (World Bank 2013). For 2016, low‐income economies were defined as those with a gross national income (GNI) per capita, as calculated using the World Bank Atlas method, of $1,025 or less in 2015; middle‐income economies as those with a GNI per capita between $1,026 and $12,475; and high‐income economies as those with a GNI per capita of $12,476 or more (www.worldbank.org/). We excluded studies undertaken in high‐income countries or focused on refugees currently living in high‐income countries. Therapies may be delivered in healthcare clinics or in other healthcare facilities, refugee camps, schools, communities, survivors’ homes, and detention facilities. We included studies recruiting inpatients and outpatients. We included studies with populations during humanitarian crises, as well as during the period after acute humanitarian crises (e.g. post‐conflict settings).

Diagnosis

We included studies that applied any standardised diagnostic criteria, including Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) III (APA 1980), DSM‐III‐R (APA 1987), DSM‐IV (APA 1994), DSM‐IV‐TR (APA 2000), DSM‐V (APA 2013), or International Classification of Diseases (ICD‐10) criteria (WHO 1992), for the following disorders.

PTSD.

Anxiety disorders (e.g. separation anxiety disorder, selective mutism, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), panic disorder, agoraphobia, substance/medication‐induced anxiety disorder).

Depressive disorders (e.g. major depressive disorder).

Somatoform symptom and related disorders, including medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS).

We included studies that assessed the presence of a mental disorder using a structured psychiatric diagnostic interview (e.g. the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan 1998)) or scoring above established cutoffs on commonly used rating scales (e.g. the Impact of Events Scale ‐ Revised, for PTSD (Weiss 1997); the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (Hamilton 1960); or the Beck Depression Inventory for Depression (Beck 1961). Earlier studies may have used ICD‐9 (WHO 1978), but ICD‐9 is not based on operationalised criteria, so we excluded from this review studies that used ICD‐9.

We excluded studies that had a primary focus on the following disorders: substance misuse; dissociative disorders; obsessive‐compulsive disorders; and child behavioural disorders. We recognise the importance of these disorders, but we found scant epidemiological data on their prevalence in LMIC humanitarian settings, and we assumed that few studies have evaluated psychological treatments for these disorders in humanitarian settings (Charlson 2016; WHO 2012).

WHO estimates that humanitarian crises may be associated with an increase of 1% to 2% in prevalence of (pre‐existing) severe neuropsychiatric disorders such as psychosis and epilepsy (WHO 2012). Although it is critical to recognise the importance of these severe neuropsychiatric disorders for humanitarian programming (Jones 2012), we do not discuss them as part of the current review.

Researchers have described the importance of culturally patterned descriptions of symptoms in humanitarian settings that do not fit current psychiatric classification systems. Such cultural concepts of distress have been the topic of epidemiological studies but have not commonly been part of outcome evaluation studies (Kohrt 2013); therefore we did not review them here.

Comorbidity

We included studies recruiting participants with mental disorder comorbidities (i.e. various combinations of the disorders listed above) and physical comorbidities. We conducted a subgroup analysis to investigate whether the presence of comorbidities affected trial results.

Types of interventions

Experimental interventions

Any psychological therapies aimed at treating patients with (symptoms of) PTSD or major depressive, anxiety, somatoform, or related disorders in humanitarian settings in LMICs.

CBT (BA and CBT‐T: NET, CETA, other CBT).

EMDR.

IPT.

TFT.

Psychodynamic therapy.

Other psychological therapies.

Comparators

Control comparators included the following.

No treatment.

Treatment as usual (TAU) (also called standard/usual care): Participants could receive any appropriate medical care during the course of the study on a naturalistic basis, as deemed necessary by the clinician.

Wait list (WL): delayed delivery of the intervention to the control group until after participants in the intervention group have completed treatment. As in TAU, participants in the WL condition could receive any appropriate medical care during the course of the study on a naturalistic basis.

Attention placebo: defined as a control condition that is regarded as inactive by both researchers and participants in a trial.

Psychological placebo: defined as a control condition that is regarded by researchers as inactive but is regarded by participants as active.

Participants may receive any appropriate medical care during the course of the study on a naturalistic basis, including pharmacotherapy, as deemed necessary by the healthcare staff. We documented any additional intervention(s) received naturalistically by participants allocated to both control and active arms. In the present review, we assessed the effectiveness of psychological therapies as delivered in typical clinical settings (not necessarily under ideal experimental conditions).

Format of psychological therapies

Psychological treatment may be delivered through any means, including, for example, face‐to‐face meetings, Internet, telephone, or self‐help booklets between participant(s) and trained professional(s) or para‐professional(s). Both individual and group psychological treatments were eligible for inclusion, with no limit applied to the number of sessions.

Excluded interventions

We excluded from this review pharmacological treatments, as well psychosocial interventions aimed at preventing mental disorders or promoting (positive aspects of) mental health and psychosocial well‐being. Separate parallel reviews have covered the latter two.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies that met the above inclusion criteria regardless of whether they reported on the following outcomes.

Primary outcomes

-

Efficacy outcome (symptom severity)

PTSD: mean change from baseline to study endpoint on the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) (Mollica 1992), the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist ‐ Civilian version (PCL‐C) (Weathers 1993), the Clinician‐Administered PTSD Scale for adults (CAPS) (Blake 1995), the Clinician‐Administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents (CAPS‐CA) (Nader 1996), or other rating scales

Anxiety disorders: mean change from baseline to study endpoint on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale ‐ Anxiety Subscale (HAD‐A) for adults (Zigmond 1983), the Screen for Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED‐5) for children and adolescents (Birmaher 1997), or any other commonly used rating scale

Major depressive disorder: mean change scores from baseline to study endpoint on the Depression Self‐Rating Scale (Birleson 1987), the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1961), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (Hamilton 1960), the Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979), or any other commonly used rating scale

Somatic symptom and related disorders: mean change scores from baseline to study endpoint on Somatic Symptom Scale‐8 (Gierk 2014), Patient Health Questionnaire‐15 (Kroenke 2002), or any other commonly used rating scale

-

Acceptability outcome

Number of participants who dropped out of psychological treatment for any reason

Secondary outcomes

Functional impairment: mean change scores from baseline to study endpoint on the Function Impairment Measure (Tol 2011a), the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHO 2010), the Global Assessment of Functioning (APA 2000), or other commonly used rating scales

Quality of life: mean change scores from baseline to study endpoint on the WHO Quality of Life Scale (WHO 1997), or on other commonly used rating scales

Presence or absence of a formal or clinical diagnosis of PTSD, anxiety disorders, depression, or somatic symptom and related disorders evaluated by psychiatric diagnostic interviews. If a psychiatric diagnostic interview was not used, we included studies that applied commonly used symptom checklists

Timing of outcome assessment

Our primary endpoint was assessed immediately after treatment (zero to four weeks after intervention). We also collected information on every other available follow‐up assessment. We categorised follow‐up data as follows: follow‐up immediately after treatment (at endpoint: zero to four weeks); follow‐up at one to four months; and follow‐up at six or more months.

Hierarchy of outcome measures

When more than one outcome measure was available in the domain of interest, as defined in outcomes, and both described the domain adequately, we chose the measure with the most detailed psychometric evaluation or that was used by other trials in the analysis. Secondarily, we chose any measure that trial authors stated was tested for suitability in the population of interest. For primary outcomes, if data from several commonly used rating scales were available, we used the following: for PTSD ‐ HTQ, PCL‐C, CAPS, and CAPS‐CA; for anxiety ‐ HAD‐A for adults (Zigmond 1983) and SCARED‐5 for children and adolescents (Birmaher 1997); for depression ‐ HDRS (Hamilton 1960); and for somatic symptom and related disorders ‐ Somatic Symptom Scale‐8 (Gierk 2014).

Search methods for identification of studies

Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR)

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group (CCMD) maintains two archived clinical trials registers at its editorial base in York, UK: a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCMDCTR‐References Register contains over 40,000 reports of RCTs in depression, anxiety, and neurosis. Approximately 50% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCMDCTR‐Studies Register, and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual, using a controlled vocabulary (please contact the CCMD Information Specialists for further details). Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 to 2016), Embase (1974 to 2016), and PsycINFO (1967 to 2016); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); and review‐specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trial registers via the WHO trials portal (the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)), pharmaceutical company websites, and handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings, and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCMD generic search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website, with an example of the core MEDLINE search used to inform the register displayed in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches

1. Cochrane Specialised Register

We cross‐searched the CCMDCTR‐Studies and References Register using terms to represent humanitarian crises in LMICs (only), as this is a specialist mental health database, so already indicative of the diagnosis (3 February 2016).

#1. (altruis* or humanitarian or human right*):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #2. (catastrophe* or disaster* or drought* or earthquake* or evacuation* or famine* or flood or floods or hurricane or cyclone* or landslide* or “land slide*” or “mass casualt*” or tsunami* or tidal wave* or volcano*):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #3. (genocide or “armed conflict*” or “mass execution*” or “mass violence”):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #4. ((war or conflict) NEAR2 (affect* or effect* or expos* or related or victim* or survivor*)):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #5. (displac* NEAR (internal or forced or mass or person* or people* or population*)):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #6. (“forced migration” or refugee*):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #7. (politic* NEAR (persecut* or prison* or imprison* or violen*)):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #8. (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7) #9. (bereav* or orphan* or widow*):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #10. (abuse* or conflict or persecut* or rape or torture or violen* or victim* or survivor* or war):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #11. (aid or relief or rescue or peace*):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #12. emergenc*:ti or (emergency NEXT (service* or setting)):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #13. (“critical incident” or “crisis intervention” or CISD):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc Lines #9 to #13 will be limited to LMIC countries, using a search filter developed by the Norwegian satellite of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (Appendix 2).

2. Other database searches

We conducted complementary searches on the following bibliographic databases in February 2015/2016 and September 2017, using relevant subject headings (controlled vocabularies) and search syntax, appropriate to each resource.

a. OVID PsycINFO (all years to 1/9/17).

b. ProQuest PILOTS database (Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress) (all years to 3/2/16).

c. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (all years to 2017, Issue 8).

d. OVID MEDLINE (1946 to 1/9/17).

e. OVID Embase (1974 to 1/9/17).

f. International Trial Registries (ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO ICTRP) (1/9/17).

We applied no restrictions on date, language, or publication status to the searches, however only studies identified from search results to 3 February 2016 have been fully incorporated into the qualitative and quantitative analysis. Studies identified in the 2017 update search have been placed in awaiting classification and will be incorporated into the next version of the revew as appropriate

In the update search (1 September 2017), we made a series of amendments and back‐dated where necessary. We added a list of demonyms to the LMIC search strategy (PsycINFO, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase) to denote the natives or inhabitants of a particular country, and appended terms for warfare to the searches. We also added keywords to identify resource‐poor settings (developing nations) (PsycINFO only). At this time we did not repeat the search of the PILOTS database or the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR), because the former search did not yield any unique studies in previous searches (to February 2016), and the latter had fallen out of date in the summer of 2016, with the move of the Editorial Group from Bristol to York.

We have reported the search strategies in Appendix 3.

4. We searched international trial registries via the WHO trials portal (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify unpublished and ongoing studies.

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We searched sources of grey literature, including dissertations and theses, humanitarian reports, evaluations published on websites, and clinical guidelines and reports from regulatory agencies (when appropriate). In addition, we searched key agencies and initiatives in this field for relevant reports.

Handsearching

We handsearched relevant conference proceedings and academic literature (titles not already indexed in Embase or PsycINFO, or already handsearched within the Cochrane Collaboration).

Reference lists

We checked the reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews (both Cochrane and non‐Cochrane) to identify additional studies missed by the original electronic searches (e.g. unpublished or in‐press citations). We also conducted a cited reference search on the Web of Science.

Correspondence

We contacted trialists and subject experts for information on unpublished and ongoing studies or to request additional trial data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MP, DP) independently screened titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria listed above for all studies identified by the search strategy for possible inclusion in the review. We added to a preliminary list all studies rated as possible candidates by either of the two review authors, and we retrieved their full texts. Moreover, we identified and recorded reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies.

We resolved any disagreements through discussion or, if required, by consultation with a third review author (CB). We identified and excluded duplicate records, and we collated multiple reports that related to the same study, so that each study rather than each report is the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram and Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection form that had been piloted on at least one study in the review to extract study characteristics and outcome data. Two review authors (MP, CG) independently extracted study characteristics and outcome data from included studies. We discussed any disagreements with an additional review author (CB), and when necessary, we contacted study authors to collect further information.

We extracted the following study characteristics.

Methods: phase of humanitarian crisis (ongoing, post‐conflict, etc.), type of humanitarian crisis, duration of psychological treatment, number of study centres and locations, study setting and dates of study, inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria.

Participants: N, mean age, age range, gender, baseline scores on commonly used rating scales, and type of psychological disorder.

Psychological therapies and comparisons (type of therapy administered, who administered therapy, etc.).

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported.

Notes: funding for trial and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

We extracted data for the following planned comparisons.

Psychological treatments versus control for adults.

Psychological treatments versus control for children/adolescents.

We analysed each comparison listed above separately for children and adolescents (younger than 18 years) and for adults (18 years or older) on the different outcomes. Moreover, we looked at whether the type of psychological therapy has an impact on the overall treatment effect by performing a subgroup analysis within each of the main comparisons for each disorder type.

We noted in the Characteristics of included studies table if outcome data were not reported in a usable way. We resolved disagreements by reaching consensus or by involving a third person (CB). Two review authors (CG, DP) working independently transferred data into the Review Manager 5.3 file. We double‐checked that data had been entered correctly by comparing data presented in the systematic review against the study reports. A third review author (MP) spot‐checked study characteristics and outcomes that had been extracted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (MP, CG) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving another review author (CB). We assessed risk of bias according to the following domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias.

We also included a set of cluster‐randomised trials, which we evaluated according to Section 16.3.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). In particular, we considered:

recruitment bias;

baseline imbalance;

loss of clusters;

incorrect analysis; and

comparability with individually randomised trials.

In particular for each cluster‐RCT, we verified, when possible, whether:

all clusters were randomised at the same time;

samples were stratified on variables likely to influence outcomes;

clusters were pair‐matched;

baseline comparability between interventions and control groups was evident.

Moreover, we included the following additional items in the 'Risk of bias' assessment (according to the review carried out by Patel 2014): therapist qualifications; treatment fidelity; therapist allegiance.

We judged each potential source of bias as high, low, or unclear, and we provided a supporting quotation from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarised 'Risk of bias' judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. When information on risk of bias was related to unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

Measures of treatment effect

We performed all comparisons between psychological therapy and no treatment, treatment as usual, attention placebo, and wait list.

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we calculated risk ratios (RRs) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). For statistically significant results, we calculated the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome and the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome.

Continuous data

We analysed continuous data as mean differences (MDs) when studies reported outcomes using the same rating scale. We used standardised mean differences (SMDs) when studies assessing the same outcome measured it by using different rating scales (Higgins 2011). We entered data presented as a scale with a consistent direction of effect. We narratively described skewed data reported as medians and interquartile ranges.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐RCTs

We included cluster‐RCTs when healthcare facilities, schools, or classes within schools rather than single individuals were the unit of allocation (Barbui 2011). Given that variation in response to psychological treatment between clusters may be influenced by cluster membership, we included, when possible, data adjusted with an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC). When the ICC was not reported or was not available from trialists, we assumed that it was 0.1 (Higgins 2011; Ukoumunne 1999).

Cross‐over trials

We included trials employing a cross‐over design. With cross‐over trials, there is the possibility of 'carry‐over' treatment effect from one period to the next. This means that the observed difference between treatments depends upon the order in which treatments were received; hence the estimated overall treatment effect will be affected (Higgins 2011). Whilst acknowledging that this design is rarely used in psychological treatment studies, we used data from the first randomised stage only.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

We included studies with two or more formats of the same therapy in meta‐analysis by combining group arms into a single group, as recommended in Section 16.5 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Conversely, we included studies with two or more different therapies in meta‐analysis without combining group arms of the study into a single group but while considering each intervention and each control group separately. To avoid inclusion of the same group of participants in the same meta‐analysis, we followed Section 16.5.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted investigators or study sponsors to verify key study characteristics and to obtain missing numerical outcome data when possible. We documented all correspondence with trialists and reported in the full review which trialists responded. For cluster‐RCTs, we contacted study authors for an ICC when data were not adjusted and could not be identified from the trial report. When ICCs were not available from trial reports nor from trialists directly, we assumed the ICC to be 0.1 (Higgins 2011; Ukoumunne 1999).

For continuous data: We applied an intention‐to‐treat analysis, whereby all participants with at least one post‐baseline measurement are represented by their last observations carried forward. When only the standard error, t‐statistics, or P values were reported, we calculated standard deviations according to Altman (Altman 1996).

For dichotomous data: We applied an intention‐to‐treat analysis, whereby we considered all dropouts not included in the analyses as negative outcomes (i.e. it was assumed they would have experienced the negative outcome by the end of the trial).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We quantified heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which calculates the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than to chance.

According to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we used the following thresholds for interpretation of I2.

0% to 40%: might not be important.

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100%: may represent considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of intervention effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (Higgins 2011; Purgato 2012).

Assessment of reporting biases

To the greatest degree possible, we minimised the impact of reporting biases by undertaking comprehensive searches of multiple sources and increasing efforts to identify unpublished material including protocols of randomised trials without language restrictions.

We used visual inspection of funnel plots to identify asymmetry in any of the comparisons between psychological treatments and comparators. We are aware that funnel plots are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes when we included 10 or fewer studies, or when all studies were of similar size. In other cases, when funnel plots were possible, we asked for statistical advice regarding their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We used a random‐effects model meta‐analysis, given the potential heterogeneity of psychological therapies. A random‐effects model has the highest generalisability in empirical examination of summary effect measures for meta‐analyses (Furukawa 2002), and this model is based on the assumption that different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects (this deserves particular attention as we included different types of psychological therapies) (der Simonian 1986). We examined the robustness of this summary measure by checking the results under a fixed‐effect model. We reported material differences between the models.

For dichotomous data, we calculated risk ratios with 95% CI. We analysed continuous scores from different rating scales using SMDs (with 95% CI).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We carried out the following subgroup analyses for primary outcomes.

Types of psychological therapies.

Diagnosis: PTSD; major depressive, anxiety, somatoform, and related disorders. Participants with different diagnoses might respond differently to trial interventions. When possible, we conducted separate analyses for participants with PTSD, major depressive, and anxiety disorders.

Presence of comorbidities, as symptoms related to other clinical conditions might influence the response to psychological therapies.

Type of traumatic event: We considered the following categories: bereavement, displacement, sexual and other forms of gender‐based violence, torture, witness of violence/atrocities, other traumatic events (IASC 2007). Different types of traumatic events might influence the effectiveness of therapies, as authors have identified different strength of association with negative psychological consequences (US Department of Health and Human Services 2014).

Type of humanitarian crisis: We considered the following categories: protracted emergencies such as wars and armed conflicts; communal violence; food shortages; disasters triggered by natural hazards such as geophysical (earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions), hydrological (floods, avalanches), climatological (droughts), meteorological (storms, cyclones), or biological hazards (epidemics, plagues); disasters triggered by technological and industrial hazards (e.g. nuclear accidents; oil spills) (reliefweb.int/). We hypothesised that the type of humanitarian crisis may differentially impact mental health outcomes as people's needs, vulnerabilities, and capacities (including their capacity to respond to psychological therapies) may vary according to the different humanitarian contexts in which they live (The Sphere Project 2011).

Phase of humanitarian crisis: We hypothesised that the phase of the humanitarian crisis may impact outcomes, as it influences individual vulnerability, capacity to use resources, and psychological reactions (Colliard 2014).

Type of interventionist (professional vs paraprofessional): We expected the types of interventionists delivering treatment to have an impact on outcomes. We noted debate in the literature regarding the role of professionals and paraprofessionals in delivering psychological interventions (Montgomery 2010). Given the cost of healthcare interventions and the minimal resources available in humanitarian settings in LMIC, it is important for researchers to investigate potential differences.

Type of control: no treatment, treatment as usual, wait list, attention placebo, and psychological placebo.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out the following sensitivity analyses.

Excluding trials with high risk of bias in the following domains: incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. These biases might impact trial results and interpretation in terms of an intervention's effectiveness estimate, in accordance with availability and completeness of outcome data from study participants,

Excluding trials with follow‐up performed immediately at the end of the psychological treatment. We kept only studies with at least one follow‐up after the first evaluation to assess the long‐term outcomes of psychological therapies.

'Summary of findings' tables

We employed the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Langendam 2013), and use of GRADEpro allowed us to import data from Review Manager 5.3 to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from studies included in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the psychological therapies examined, and the sum of available data on the outcomes considered. We adhered to standard methods for preparation and presentation of results as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

We included the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

PTSD.

Major depressive disorder.

Anxiety disorders.

Somatoform and related disorders (including MUPS).

Acceptability (dropout rate).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

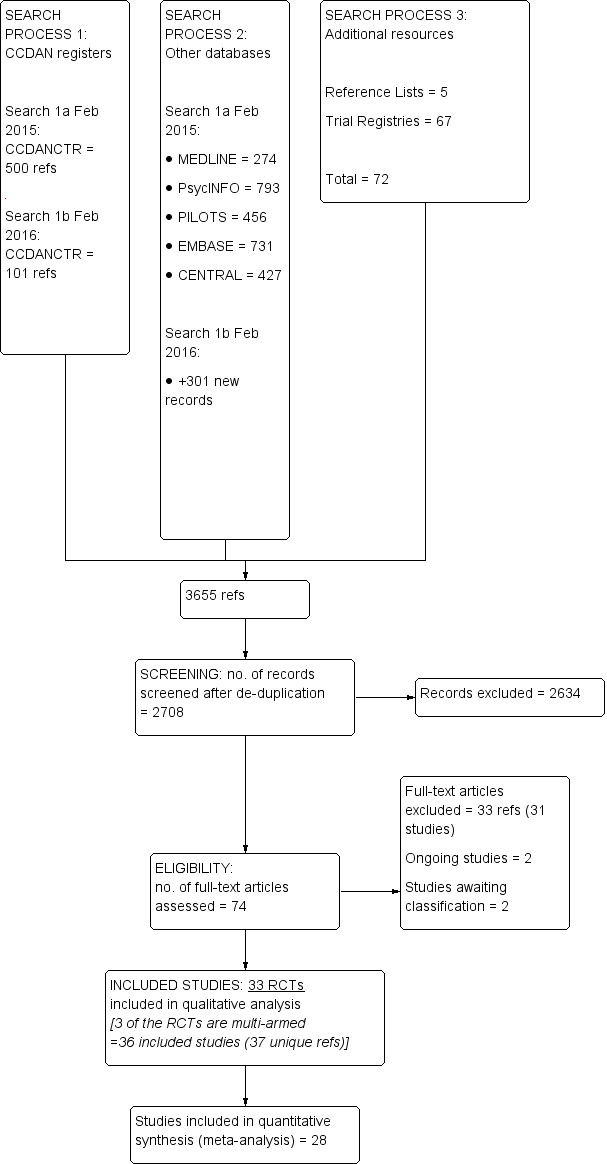

From 3655 records (identified from searches to February 2016), we identified 68 studies (33 RCTs for inclusion, 31 excluded studies, 2 awaiting classification and 2 ongoing) (see Figure 1 for the search flow diagram).

1.

Study flow diagram.

The update search in September 2017 retrieved 574 new records and after screening these we identified a further 8 studies which we've added to awating classification and 1 additional ongoing study. Only results of searches to 3 February 2016 have been formally incorporated into the analysis at this stage (and are reported in the PRISMA flow diagram).

We included 33 RCTs (36 studies, as 3 of the RCTs were multi‐armed trials) with a total of 3523 participants (see Characteristics of included studies) and excluded 31 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies). All included studies were RCTs. We identified no cluster‐randomised trials. We have not yet assessed 10 studies ‐ one because it requires translation, another because the full‐text was not available to determine eligibility for this review and the remaining studies are from the 2017 update search, which will be assessed for eligibility in the next version of the revew (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). We also identified a total of three ongoing studies (Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies.

Settings

Four of the included studies were done in Turkey (Acarturk 2015; Acaturk 2016; Basoglu 2005; Basoglu 2007); two in Iran (Ahmadizadeh 2013; Azad Marzabadi 2014); two in Kurdistan (Bass 2016; Bolton 2014a); two in Pakistan (Rahman 2016a; Rahman 2016b); one in Kosovo (Wang 2016); three in Thailand (Bolton 2014b; Bryant 2011; Pityaratstian 2015); one in Sri Lanka (Puvimanasinghe 2016); five in China (Chen 2014; Jiang 2014; Wang 2013a; Zang 2013; Zang 2014), and two in Iraq (Knaevelsrud 2015; Weiss 2015a). The remaining 11 studies were undertaken in Africa: three in Uganda (Bolton 2007; Ertl 2011; Neuner 2008a); three in Rwanda (Connolly 2011; Connolly 2013; Jacob 2014); three in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Hermenau 2013; McMullen 2013; O' Callaghan 2013); one in Mozambique (Igreja 2004); and one in Egypt (Meffert 2014).

We categorised humanitarian crises into five main categories: war or armed conflict (Acarturk 2015; Acaturk 2016; Ahmadizadeh 2013; Azad Marzabadi 2014; Bass 2016; Ertl 2011; Hermenau 2013; Igreja 2004; Jacob 2014; Knaevelsrud 2015; McMullen 2013; Meffert 2014; Neuner 2008a; O' Callaghan 2013; Rahman 2016a; Rahman 2016b; Weiss 2015a); disasters triggered by natural events (Basoglu 2005; Basoglu 2007; Chen 2014; Pityaratstian 2015; Zang 2013; Zang 2014); communal violence (Bolton 2014a; Bolton 2014b; Connolly 2011; Connolly 2013); food shortages (Bryant 2011); and other types (Puvimanasinghe 2016; Wang 2013a). The context of treatment varied across studies: 13 of the included studies delivered interventions in healthcare clinics or facilities (Ahmadizadeh 2013; Azad Marzabadi 2014; Bass 2016; Bolton 2014a; Bryant 2011; Jiang 2014; Meffert 2014; Rahman 2016a; Rahman 2016b; Wang 2016; Weiss 2015a; Zang 2013; Zang 2014); five in community settings (Basoglu 2005; Bolton 2014b; Ertl 2011; Hermenau 2013; Puvimanasinghe 2016); four in refugee camps (Acarturk 2015; Acaturk 2016; Bolton 2007; Neuner 2008a); three at school (Chen 2014; McMullen 2013; Pityaratstian 2015); two at home (Igreja 2004; Jacob 2014); and the remaining six in other settings (Basoglu 2007; Connolly 2011; Connolly 2013; Knaevelsrud 2015; O' Callaghan 2013; Wang 2013a). Most included studies delivered psychological treatments after the acute crisis period had ended.

Sample sizes

Included studies consisted of 3523 participants, and the number of participants in each trial ranged from 22 in Meffert 2014 to 347 in Bolton 2014b.

Participants

Included participants in four studies were children and adolescents between 5 and 18 years of age (Chen 2014; McMullen 2013; O' Callaghan 2013; Pityaratstian 2015). Three studies included mixed populations (two studies included participants between 12 and 25 years of age (Ertl 2011; mean age 18.66 years, standard deviation (SD) 3.77 in the CBT group; mean age 18.06 years, SD 3.55 years in the control group; Hermenau 2013; mean age of the whole sample 19 years, SD 2.02), and one study included participants between 16 and 65 years of age (Basoglu 2005; mean age of the whole sample 36.3 years, SD 11.5 years in the control group). Remaining studies included adult populations (18 years or older). In studies with mixed populations, we considered mean age and SD reported in the papers to categorise populations into children or adults for meta‐analysis.

In 24 studies, most (more than 50%) participants were female. In the remaining nine studies, most (more than 50%) participants were male.

Regarding types of traumatic events, participants were exposed to bereavement in four studies (Basoglu 2005; Basoglu 2007; Bryant 2011; Chen 2014); displacement in seven studies (Acarturk 2015; Acaturk 2016; Ertl 2011; Meffert 2014; Neuner 2008a; Zang 2013; Zang 2014); sexual and other forms of gender‐based violence in one study (O' Callaghan 2013); torture and witness to violence or atrocities in 11 studies (Ahmadizadeh 2013; Azad Marzabadi 2014; Bass 2016; Bolton 2014a; Connolly 2011; Connolly 2013; Hermenau 2013; Jacob 2014; McMullen 2013; Wang 2013a; Weiss 2015a); and compound stressors or other types of stressors in the remaining studies.

Regarding types of mental disorders, 25 studies included participants with PTSD, three with PTSD and/or depression, two with anxiety and/or depression and/or emotional distress, and three with depression.

Interventions and comparators

Included trials compared a psychological therapy versus a control intervention (wait list in most studies; no treatment; treatment as usual). The psychological therapy was categorised as belonging to a type of group CBT in 27 studies, that is, CBT in 16 studies (Ahmadizadeh 2013; Azad Marzabadi 2014; Basoglu 2005; Basoglu 2007; Bolton 2014a; Bryant 2011; Chen 2014; McMullen 2013; O' Callaghan 2013; Pityaratstian 2015; Rahman 2016a; Rahman 2016b; Wang 2013a; Wang 2013b; Wang 2016; Weiss 2015a), NET in eight studies (Ertl 2011; Hermenau 2013; Igreja 2004; Jacob 2014; Neuner 2008a; Puvimanasinghe 2016; Zang 2013; Zang 2014), BA in one study (Bolton 2014a), and CETA in two studies (Bolton 2014b; Weiss 2015b).

IPT was studied in three studies (Bolton 2007; Jiang 2014; Meffert 2014), TFT in two studies (Connolly 2011; Connolly 2013), EMDR in two comparisons (Acarturk 2015; Acaturk 2016), and trauma/supportive counselling in two comparisons (Bass 2016; Neuner 2008b). Although psychological therapies were grouped into these categories, several psychotherapeutic elements were common to a range of therapies. In particular, a focus on psychoeducation and/or coping skills was common to most interventions. Most included trials delivered psychological therapy at the individual level (24 studies); six compared group delivery or mixed delivery (individual and group) of psychological therapies versus control; and the remaining three studies were unclear about the type of delivery provided.

Interventionists were professionals (i.e. trained psychologists or psychiatrists) in 14 comparisons, and paraprofessionals (i.e. trained lay counsellors; community health workers) in the remaining trials.

Outcomes

At the end of the reviewing process, 28 RCTs provided data for meta‐analysis. For primary outcomes, 19 RCTs provided continuous data on PTSD at endpoint, 14 RCTs provided data on depression at endpoint, and five RCTs provided data on anxiety at endpoint. For the primary outcome of acceptability, 26 RCTs provided data on total dropouts for any cause.

Overall, 1402 participants were included in the efficacy analysis for the continuous outcome PTSD at endpoint (1272 adults and 130 children); 1254 were included in the efficacy analysis for the continuous outcome depression at endpoint (all adults: 651 participants randomised to psychological therapy and 603 randomised to control); and 694 participants were included in the continuous outcome anxiety at endpoint (all adults: 370 participants randomised to psychological therapy and 324 randomised to control). A total of 3098 participants were included in the primary outcome of acceptability (2960 adults and 138 children).

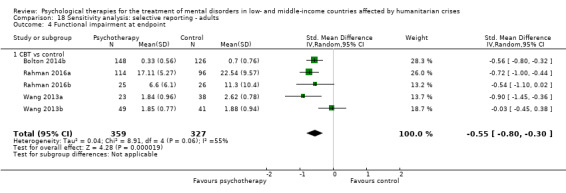

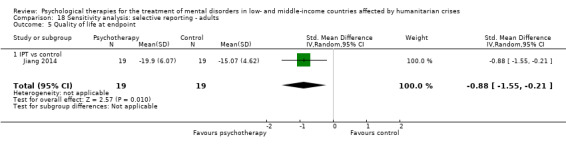

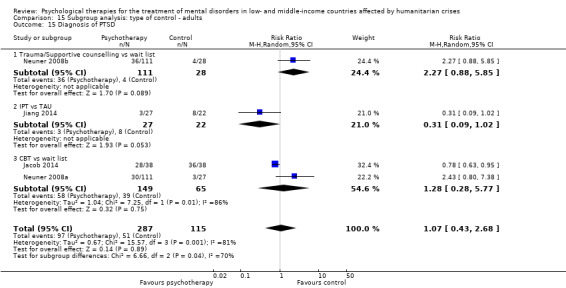

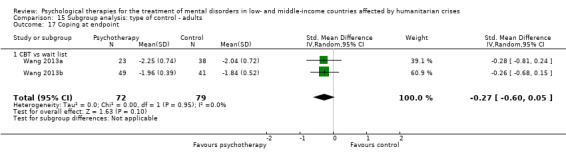

For secondary outcomes, 686 participants were included in the efficacy analysis for the continuous outcome function impairment at endpoint (359 participants randomised to psychological therapy and 327 randomised to control); 325 participants were included in the efficacy analysis for the continuous outcome quality of life at endpoint (187 participants randomised to psychological therapy and 138 randomised to control); and 440 participants were included in the efficacy analysis for the dichotomous outcome diagnosis of PTSD at endpoint (402 adults and 36 children).

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Thirty‐one studies initially selected did not meet our inclusion criteria and were excluded because of wrong setting (no humanitarian crisis in LMICs) for eight studies; wrong design (no RCT or incorrect randomisation procedure) for nine studies; and wrong comparison (no psychological therapy compared with control) for three studies. Moreover, we excluded 11 RCTs assessing the effectiveness of preventive psychosocial interventions. We will include these studies in the Cochrane review specifically focused on preventive psychosocial interventions in humanitarian settings in LMICs (Purgato 2016a).

Studies awaiting classification

We classified 10 records as awaiting classification, as we did not have the elements needed to evaluate their eligibility.

Ongoing studies

We classified three studies as ongoing: One is just finished, and results are planned to be published in 2018 (ISRCTN65771265), one is estimated to be completed in 2018 (NCT03012451), and one is at the beginning of the recruitment phase (NCT031090028). See Characteristics of ongoing studies.

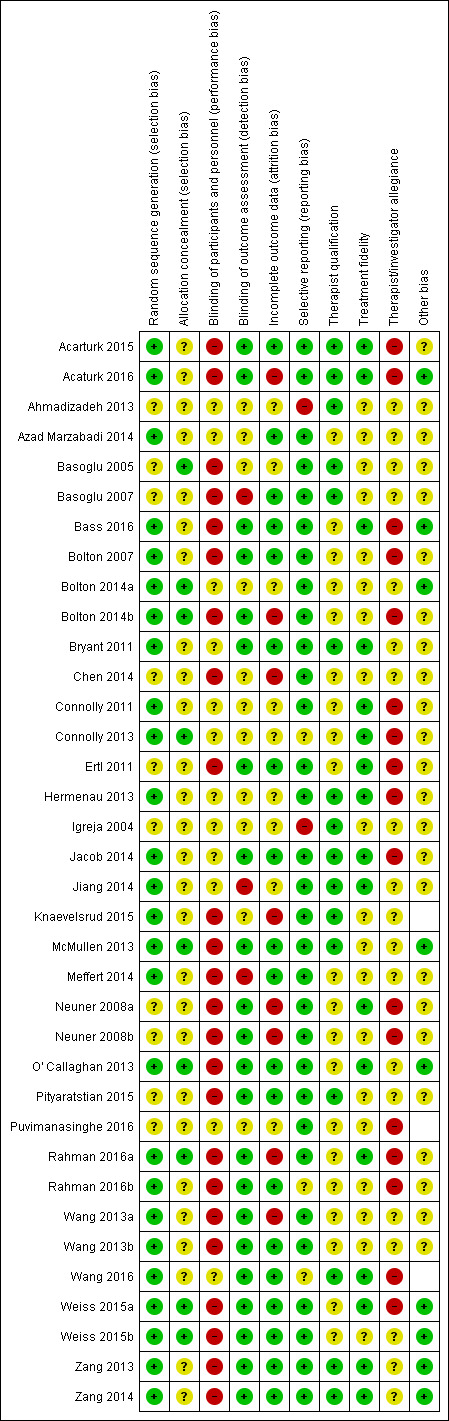

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies. For graphical representations of overall risk of bias in included studies, see Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Researchers described generation of a random sequence that we considered to lead to low risk of bias in 26 comparisons (Acarturk 2015; Acaturk 2016; Azad Marzabadi 2014; Bass 2016; Bolton 2007; Bolton 2014a; Bolton 2014b; Bryant 2011; Connolly 2011; Connolly 2013; Hermenau 2013; Jacob 2014; Jiang 2014; Knaevelsrud 2015; McMullen 2013; Meffert 2014; O' Callaghan 2013; Rahman 2016a; Rahman 2016b; Wang 2013a; Wang 2013b; Wang 2016; Weiss 2015a; Weiss 2015b; Zang 2013; Zang 2014) and to unclear risk of bias in the remaining studies. Regarding allocation concealment, we considered nine of the included trials to be at low risk (Basoglu 2005; Bolton 2014a; Bolton 2014b; Connolly 2013; McMullen 2013; O' Callaghan 2013; Rahman 2016a; Weiss 2015a; Weiss 2015b). The 24 remaining RCTs did not describe allocation concealment; we therefore rated them as having unclear risk.

Blinding

Performance bias

Participants (both personnel and study participants) would have been aware of whether they had been assigned to an intervention group or a control group in 24 trials (Acarturk 2015; Acaturk 2016; Basoglu 2005; Basoglu 2007; Bass 2016; Bolton 2007; Bolton 2014b; Chen 2014; Ertl 2011; Knaevelsrud 2015; McMullen 2013; Meffert 2014; Neuner 2008a; Neuner 2008b; O' Callaghan 2013; Pityaratstian 2015; Rahman 2016a; Rahman 2016b; Wang 2013a; Wang 2013b; Weiss 2015a; Weiss 2015b; Zang 2013; Zang 2014); therefore, we rated these studies as having high risk of performance bias. We rated the remaining trials as having unclear risk of performance bias.

Detection bias

We rated trials as having low risk of bias when researchers described blinded assessment of outcomes (Acarturk 2015; Acaturk 2016; Bass 2016; Bolton 2007; Bolton 2014b; Bryant 2011; Ertl 2011; Jacob 2014; McMullen 2013; Neuner 2008a; Neuner 2008b; O' Callaghan 2013; Pityaratstian 2015; Rahman 2016a; Rahman 2016b; Wang 2013a; Wang 2013b; Wang 2016; Weiss 2015a; Weiss 2015b; Zang 2013; Zang 2014). We rated three trials as having high risk of bias, as the assessors were likely to be aware of participant allocation (Basoglu 2007; Jiang 2014; Meffert 2014); we rated risk in the remaining trials as unclear (Ahmadizadeh 2013; Azad Marzabadi 2014; Basoglu 2005; Bolton 2014a; Chen 2014; Connolly 2011; Connolly 2013; Hermenau 2013; Igreja 2004; Knaevelsrud 2015; Puvimanasinghe 2016).

Incomplete outcome data

Risk of attrition bias was low in 19 studies, as researchers clearly reported low dropout rates (Acarturk 2015; Azad Marzabadi 2014; Basoglu 2007; Bass 2016; Bolton 2007; Bryant 2011; Ertl 2011; Jacob 2014; McMullen 2013; Meffert 2014; O' Callaghan 2013; Pityaratstian 2015; Rahman 2016b; Wang 2013b; Wang 2016; Weiss 2015a; Weiss 2015b; Zang 2013; Zang 2014). We considered eight trials to have high risk of attrition bias because researchers reported incomplete outcome data. We rated the remaining trials as having unclear risk.

Selective reporting

Even though the study protocol was not available for many of the included studies, most included studies showed consistency between Results and Methods sections (31 comparisons).

Other potential sources of bias

We rated risk of other bias as low in nine trials and as unclear in the remaining trials.

We visually inspected funnel plots to identify asymmetry in any of the comparisons between psychological treatments and comparators when we identified 10 or more studies. We did not identify any asymmetry in the distribution of studies.

We included in our risk of bias evaluation the following additional items.

Therapist qualification: We considered 16 trials as having low risk of bias with regard to the qualifications of therapists, as trained professionals in mental health (mainly psychologists or psychiatrists) delivered psychological therapy (Acarturk 2015; Acaturk 2016; Ahmadizadeh 2013; Basoglu 2005; Basoglu 2007; Bryant 2011; Hermenau 2013; Igreja 2004; Jacob 2014; Jiang 2014; Knaevelsrud 2015; McMullen 2013; Pityaratstian 2015; Wang 2016; Zang 2013; Zang 2014). For the remaining trials, we evaluated the risk as unclear.

Treatment fidelity: Sixteen trials described the system used to monitor treatment fidelity, and we rated their risk of bias as low (Acarturk 2015; Acaturk 2016; Bass 2016; Bryant 2011; Connolly 2011; Connolly 2013; Ertl 2011; Hermenau 2013; Jiang 2014; Neuner 2008a; O' Callaghan 2013; Rahman 2016a; Wang 2016; Weiss 2015a; Zang 2013; Zang 2014). We evaluated risk as unclear for the remaining trials because researchers provided no details about fidelity checks.

Therapist/investigator allegiance: We rated the risk of therapist or investigator allegiance as high in 17 trials and as unclear in the remaining trials.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Psychological therapy compared with control for treatment of adults with mental disorders in low‐ and middle‐income countries affected by humanitarian crises.

| Psychological therapy compared with control for treatment of adults with mental disorders in low‐ and middle‐income countries affected by humanitarian crises | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults exposed to traumatic events Setting: humanitarian settings in LMICs Intervention: psychological therapy Comparison: wait list; no treatment; treatment as usual | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with psychological therapy | |||||

| Post‐traumatic stress disorder at endpoint (measured with IES‐R; HTQ; CAPS; UCLA‐PTSD‐RI; PDS; PCL‐5) |

‐ | SMD 1.07 lower (1.34 lower to 0.79 lower) | ‐ | 1272 (16 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | This is a large effect according to Cohen 1992 |

| Depression at endpoint (measured with BDI‐II, HSCL‐25, HADS) |

‐ | SMD 0.86 SD lower (1.06 lower to 0.67 lower) | ‐ | 1254 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | This is a large effect according to Cohen 1992 |