Abstract

Background

Dental pain can have a detrimental effect on quality of life. Symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess are common causes of dental pain and arise from an inflamed or necrotic dental pulp, or infection of the pulpless root canal system. Clinical guidelines recommend that the first‐line treatment for teeth with these conditions should be removal of the source of inflammation or infection by local, operative measures, and that systemic antibiotics are currently only recommended for situations where there is evidence of spreading infection (cellulitis, lymph node involvement, diffuse swelling) or systemic involvement (fever, malaise). Despite this, there is evidence that dentists frequently prescribe antibiotics in the absence of these signs. There is concern that this could contribute to the development of antibiotic‐resistant bacterial colonies within both the individual and the community. This review is an update of the original version that was published in 2014.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of systemic antibiotics provided with or without surgical intervention (such as extraction, incision and drainage of a swelling, or endodontic treatment), with or without analgesics, for symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess in adults.

Search methods

Cochrane Oral Health's Information Specialist searched the following databases: Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register (to 26 February 2018), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 1) in the Cochrane Library (searched 26 February 2018), MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 26 February 2018), Embase Ovid (1980 to 26 February 2018), and CINAHL EBSCO (1937 to 26 February 2018). The US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (ClinicalTrials.gov) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform were searched for ongoing trials. A grey literature search was conducted using OpenGrey (to 26 February 2018) and ZETOC Conference Proceedings (1993 to 26 February 2018). No restrictions were placed on the language or date of publication when searching the electronic databases.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of systemic antibiotics in adults with a clinical diagnosis of symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess, with or without surgical intervention (considered in this situation to be extraction, incision and drainage or endodontic treatment) and with or without analgesics.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors screened the results of the searches against inclusion criteria, extracted data and assessed risk of bias independently and in duplicate. We calculated mean differences (MD) (standardised mean difference (SMD) when different scales were reported) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for continuous data. A fixed‐effect model was used in the meta‐analysis as there were fewer than four studies. We contacted study authors to obtain missing information.

Main results

We included two trials in this review, with 62 participants included in the analyses. Both trials were conducted in university dental schools in the USA and compared the effects of oral penicillin V potassium (penicillin VK) versus a matched placebo when provided in conjunction with a surgical intervention (total or partial pulpectomy) and analgesics to adults with acute apical abscess or symptomatic necrotic tooth. The patients included in these trials had no signs of spreading infection or systemic involvement (fever, malaise). We assessed one study as having a high risk of bias and the other study as having unclear risk of bias.

The primary outcome variables reported in both studies were participant‐reported pain and swelling (one trial also reported participant‐reported percussion pain). One study reported the type and number of analgesics taken by participants. One study recorded the incidence of postoperative endodontic flare‐ups (people who returned with symptoms that necessitated further treatment). Adverse effects, as reported in one study, were diarrhoea (one participant, placebo group) and fatigue and reduced energy postoperatively (one participant, antibiotic group). Neither study reported quality of life measurements.

Objective 1: systemic antibiotics versus placebo with surgical intervention and analgesics for symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess Two studies provided data for the comparison between systemic antibiotics (penicillin VK) and a matched placebo for adults with acute apical abscess or a symptomatic necrotic tooth when provided in conjunction with a surgical intervention. Participants in one study all underwent a total pulpectomy of the affected tooth, while participants in the other study had their tooth treated by either partial or total pulpectomy. Participants in both trials received oral analgesics. There were no statistically significant differences in participant‐reported measures of pain or swelling at any of the time points assessed within the review. The MD for pain (short ordinal numerical scale 0 to 3) was ‐0.03 (95% CI ‐0.53 to 0.47) at 24 hours; 0.32 (95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.86) at 48 hours; and 0.08 (95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.54) at 72 hours. The SMD for swelling was 0.27 (95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.78) at 24 hours; 0.04 (95% CI ‐0.47 to 0.55) at 48 hours; and 0.02 (95% CI ‐0.49 to 0.52) at 72 hours. The body of evidence was assessed as at very low quality.

Objective 2: systemic antibiotics without surgical intervention for adults with symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess We found no studies that compared the effects of systemic antibiotics with a matched placebo delivered without a surgical intervention for symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess in adults.

Authors' conclusions

There is very low‐quality evidence that is insufficient to determine the effects of systemic antibiotics on adults with symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess.

Plain language summary

The effects of antibiotics on toothache caused by inflammation or infection at the root of the tooth in adults

This Cochrane Review has been produced to assess the effects of antibiotics on the pain and swelling experienced by adults in two conditions commonly responsible for causing dental pain. The review set out to assess the effects of taking antibiotics when provided with, or without, dental treatment.

Background

Dental pain is a common problem and can arise when the nerve within a tooth dies due to progressing decay or injury. Without treatment, bacteria can infect the dead tooth and cause a dental abscess, which can lead to swelling and spreading infection, which can occasionally be life threatening.

The recommended treatment for these forms of toothache is removal of the dead nerve and associated bacteria. This is usually done by extraction of the tooth or root canal treatment (a procedure where the nerve and pulp are removed and the inside of the tooth cleaned and sealed). Antibiotics are only recommended when there is severe infection that has spread from the tooth into the surrounding tissues. However, some dentists still routinely prescribe oral antibiotics to patients with acute dental conditions who have no signs of spreading infection, or without dental treatment to remove the infected material.

Use of antibiotics contributes to the development of antibiotic‐resistant bacteria. It is therefore important that antibiotics are only used when they are likely to result in benefit for the patient. Dentists prescribe approximately 8% to 10% of all primary care antibiotics in high‐income countries, and therefore it is important to ensure that dentists have good information about when antibiotics are likely to be beneficial for patients.

Study characteristics

The evidence on which this review is based was up‐to‐date as of 26 February 2018. We searched scientific databases and found two trials, with 62 participants included in the analysis. Both trials were conducted at dental schools in the USA and evaluated the use of oral antibiotics in the reduction of pain and swelling reported by adults after having the first stage of root canal treatment under local anaesthetic. The antibiotic used in both trials was penicillin VK and all participants also received painkillers.

Key results

The two studies included in the review reported that there were no clear differences in the pain or swelling reported by participants who received oral antibiotics compared with a placebo (a dummy treatment) when provided alongside the first stage of root canal treatment and painkillers. However, the studies were small and produced poor quality evidence, and therefore we cannot be certain if the results are correct. Neither study examined the effect of antibiotics on their own, without surgical dental treatment.

One trial reported side effects among participants: one person who received the placebo medication had diarrhoea and one person who received antibiotics experienced tiredness and reduced energy after their treatment.

Quality of evidence

We judged the quality of evidence to be very low. There is currently insufficient evidence to be able to determine the effects of antibiotics in these conditions.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Systemic antibiotics with a surgical intervention and analgesics for managing symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess in adults.

| Systemic antibiotics with a surgical intervention and analgesics for managing symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with a symptomatic necrotic tooth or localised acute apical abscess (no signs of spreading infection or systemic involvement) Settings: university dental schools, USA Intervention: systemic antibiotics, partial or total pulpectomy and analgesics Comparison: matched placebo, partial or total pulpectomy and analgesics | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Matched placebo, partial or total pulpectomy and analgesics | Systemic antibiotics, partial or total pulpectomy and analgesics | |||||

| Pain at 24 hours Short ordinal numerical scale. Scale from: 0 to 3 | The mean pain at 24 hours ranged across control groups from: 1.0 to 1.68 | The mean pain at 24 hours in the intervention groups was 0.03 lower (0.53 lower to 0.47 higher) | ‐ | 61 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1, 2, 3 | ‐ |

| Pain at 48 hours Short ordinal numerical scale. Scale from: 0 to 3 | The mean pain at 48 hours ranged across control groups from: 0.8 to 0.95 | The mean pain at 48 hours in the intervention groups was 0.32 higher (0.22 lower to 0.86 higher) | ‐ | 61 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1, 2, 3 | ‐ |

| Pain at 72 hours Short ordinal scale. Scale from: 0 to 3 | The mean pain at 72 hours ranged across control groups from: 0.3 to 0.82 | The mean pain at 72 hours in the intervention groups was 0.08 higher (0.38 lower to 0.54 higher) | ‐ | 61 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1, 2, 3 | ‐ |

| Swelling at 24 hours Different short ordinal numerical scales | The mean swelling at 24 hours in the control groups was 0.594 | The mean swelling at 24 hours in the intervention groups was 0.27 standard deviations higher (0.23 lower to 0.78 higher) | ‐ | 62 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1, 2, 3 | This converts back into a 36% increase (95% CI 31% decrease to 105% increase) of control mean for antibiotics (based on 1 study at unclear risk of bias) |

| Swelling at 48 hours Different short ordinal numerical scales | The mean swelling at 48 hours in the control groups was 0.734 | The mean swelling at 48 hours in the intervention groups was 0.04 standard deviations higher (0.47 lower to 0.55 higher) | ‐ | 61 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1, 2, 3 | This converts back into a 4% increase (95% CI 49% decrease to 58% increase) of control mean for antibiotics (based on 1 study at unclear risk of bias) |

| Swelling at 72 hours Different short ordinal numerical scales | The mean swelling at 72 hours in the control groups was 0.594 | The mean swelling at 72 hours in the intervention groups was 0.02 standard deviations higher (0.49 lower to 0.52 higher) | ‐ | 61 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1, 2, 3 | This converts back into a 2% increase (95% CI 55% decrease to 59% increase) of control mean for antibiotics (based on 1 study at unclear risk of bias) |

| Adverse effects | During the 3‐day follow‐up period in Fouad 1996, 1 participant in the placebo group reported diarrhoea and 1 participant in the antibiotic group reported fatigue and reduced energy postoperatively | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

11 study with high risk of bias and small group sizes. 21 study with unclear risk of bias and small group sizes. 3Different surgical interventions employed. Participants in 1 study had partial or total pulpectomy (there was no way of distinguishing between the 2 treatment modalities) while participants in the other all had total pulpectomy. 4Re‐expressed from the standardised mean difference into the short ordinal numerical scale used by Henry 2001. Results should be interpreted with caution since back‐translation of the effect size is based on the results of only 1 study.

Background

Description of the condition

Dental pain can have a detrimental effect on an individual's social functioning and quality of life (Pau 2005; Reisine 1995). In the UK Adult Dental Health Survey of 2009, 29% of individuals reported experiencing dental pain "occasionally" or "fairly/very often" during the preceding 12 months. The overall prevalence of dental pain among survey respondents was 9%, with higher values reported for younger individuals and those from lower socioeconomic groups (Steele 2011). Among adults presenting with acute dental conditions, approximately 16% will have symptomatic apical periodontitis and a further 20% will have an acute apical abscess (Cope 2016).

Apical periodontitis arises following injury to the pulpal tissues of a tooth caused by dental caries, tooth fracture, trauma, or iatrogenic damage. While the dental pulp can recover from reversible pulpitis resulting from a mild to moderate injury, persistent or extensive damage results in irreversible levels of inflammation within the pulpal tissues. Should this occur, an individual might experience symptoms of irreversible pulpitis. Without treatment, irreversibly inflamed teeth then undergo pulpal necrosis and bacterial colonisation of the root canal system (Abbott 2004; Bergenholtz 2010).

Apical periodontitis (also known as periapical periodontitis) is an inflammatory lesion of the periradicular tissues that arises principally due to the egress of irritants, such as bacteria and toxins, from an inflamed or necrotic pulp (Torabinejad 1994). Its evolutionary role is protective: to contain the root canal bacteria and prevent the spread of infection. While the vast majority of cases are asymptomatic, exacerbations of apical periodontitis can present as symptomatic apical periodontitis or an acute apical abscess(Bergenholtz 2010).

Symptomatic apical periodontitis can arise either from a formerly healthy tooth that has subsequently undergone pulpal breakdown or from a tooth with a previously asymptomatic apical periodontitis. It is characterised by a dull or throbbing pain that is exacerbated by biting. The affected tooth usually has a negative or delayed positive response to vitality testing and is often highly sensitive to percussive forces (Bergenholtz 2010).

It should be noted that in determining the health of pulpal tissues, the term 'vitality testing' is commonly used. True 'vitality' tests attempt to examine the presence of pulp blood flow, while 'sensibility' tests employ the use of thermal or electrical stimuli to elicit a response from innervated tissue (Chen 2009). Although neither can definitively indicate the health of the dental pulp, they remain useful diagnostic aids, commonly used in both clinical practice and scientific studies.

Acute apical abscesses develop in the presence of a pre‐existing apical periodontitis (Carrotte 2004). The persistent presence of infective material within the pulpless root canal system and around the apex of a tooth can lead to a massive influx of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the periradicular tissues, leading to tissue liquefaction and pus formation (Bergenholtz 2010). Also known as a periapical, dentoalveolar, or alveolar abscess, an apical abscess is characterised by the accumulation of pus in the periradicular tissues and can present as either an acute or a chronic lesion. Individuals with acute apical abscesses typically complain of a rapid onset, spontaneous pain, tenderness of the tooth to pressure, pus formation, and swelling of associated tissues (Glickman 2009). Left untreated, the abscess may spread, resulting in a potentially serious head and neck infection accompanied by fever, malaise, and lymph node involvement (Abbott 2004). Since symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess represent a continuum of the same disease process, it is appropriate to consider both conditions in this review (Sutherland 2004).

Description of the intervention

Clinical guidelines currently recommend that the first‐line treatment for teeth with either symptomatic apical periodontitis or an acute apical abscess is the removal of the source of inflammation or infection by local, operative measures (Glenny 2004; SDCEP 2016). This could involve extraction of the offending tooth or extirpation (removal) of the pulpal tissues, possibly in combination with the incision and drainage of any swelling present.

Systemic antibiotics are currently only recommended for situations where there is evidence of spreading infection (cellulitis, lymph node involvement, diffuse swelling) or systemic symptoms (fever, malaise) (Palmer 2015; SDCEP 2016). Despite this, there is evidence that antibiotics are often prescribed by dentists to patients with symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess in the absence of these signs (Cope 2016; Germack 2017; Segura‐Egea 2010; Yingling 2002). In a study, 69% of individuals attending a British out‐of‐hours dental clinic with symptomatic apical periodontitis received a prescription for systemic antibiotics, many in the absence of a surgical intervention (Dailey 2001).

How the intervention might work

Doctors and dentists may prescribe systemic antibiotics to minimise the signs and symptoms of symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess, and to treat or prevent the development of a serious orofacial swelling with systemic involvement. Antibiotics can be prescribed as an adjunctive or stand‐alone treatment. People prescribed antibiotics may be given analgesics at the same time.

Why it is important to do this review

There is international concern about the overuse of antibiotics and the emergence of antibiotic‐resistant bacterial strains (World Health Organization 2000). Since dentists prescribe approximately 8% to 10% of antibiotics dispensed in primary care in high‐income countries, it is important not to underestimate the potential contribution of the dental profession to the development of antibiotic resistance (Al‐Haroni 2007; Halling 2017; Holyfield 2009). The use of antibiotics in situations where their use is not indicated not only drives antibiotic resistance, it is a misuse of resources, increases the risk of potentially fatal anaphylactic reactions and exposes people to unnecessary side effects (Costelloe 2010; Gonzales 2001). Furthermore, antibiotic prescribing for common medical problems may increase patient expectations for antibiotics, leading to a vicious cycle of increased prescribing in order to meet expectations (Coenen 2006; Little 1997).

It is important that antibiotics are prescribed for patients only when they are likely to result in clinical benefit. If systemic antibiotics are effective in the treatment of symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess then it is important that the nature of any benefits are quantified. However, if antibiotics are ineffective, patients are being unnecessarily exposed to harmful side effects and the increased possibility of developing antibiotic‐resistant bacterial colonies. Therefore, the objective of this review was to evaluate the effects of systemic antibiotics for symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess in adults. This is an update of the original version that was published in 2014 (Cope 2014).

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of systemic antibiotics provided with or without surgical intervention (such as extraction, incision and drainage of a swelling, or endodontic treatment), with or without analgesics, for symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with parallel group design in the review. We excluded cluster RCTs.

Types of participants

Studies of adults (18 years of age or older), male or female, who presented with a single tooth with a clinical diagnosis of either symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess.

Types of interventions

Active intervention

Administration of any systemic antibiotic (either oral or intravenous) at any dosage prescribed in the symptomatic phase of apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess with or without analgesics, and with or without surgical intervention (extraction, incision and drainage or endodontic treatment).

Control

Administration of a matched placebo prescribed in the symptomatic phase of apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess with or without analgesics, and with or without surgical intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Measures of participant‐reported pain and swelling, gauged on either a continuous scale, such as visual analogue scale (VAS), or using binary or dichotomous outcomes.

Clinician‐reported measures of infection, such as swelling, temperature, trismus (reduced mouth opening), regional lymphadenopathy or cellulitis. These outcomes may have be reported as continuous, categorical or dichotomous variables.

Secondary outcomes

Participant‐reported quality of life measures.

Type, dose and frequency of analgesics used.

Any adverse effects or harm (hypersensitivity or other reactions) attributed to antibiotics or analgesics, complications of surgical treatment or hospitalisations.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Oral Health's Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions:

Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register (searched 26 February 2018);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 1) in the Cochrane Library (searched 26 February 2018);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 26 February 2018);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 26 February 2018);

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to 26 February 2018);

OpenGrey (to 26 February 2018);

ZETOC Conference Proceedings (1993 to 26 February 2018).

Subject strategies were modelled on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE Ovid. Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chapter 6 (Lefebvre 2011).

The full search strategies used for each database can be found in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

The following trial registries were searched for ongoing studies:

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 26 February 2018);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 26 February 2018).

We checked the reference lists of all included and excluded studies to identify any further trials.

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions used, we considered adverse effects described in included studies only.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (Anwen L Cope (ALC) and Ivor G Chestnutt (IGC)) independently assessed the titles and abstracts (where available) of the articles identified by the search strategy and made decisions regarding eligibility. The search was designed to be sensitive and include controlled clinical trials, these were filtered out early in the selection process if they were not randomised. Full‐text versions were obtained for all articles being considered for inclusion, as were those with insufficient information in the title or abstract to make a clear decision. We resolved any disagreements by discussion. We excluded studies later found not to meet the inclusion criteria and recorded them in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

We entered study details into the Characteristics of included studies table. ALC and IGC independently extracted the outcome data from the included studies using a standard data extraction form. The review authors discussed the results and resolved any disagreements. In cases where uncertainties persisted, we contacted the study authors for clarification.

We extracted the following characteristics of the studies.

Study methodology: study design, methods of allocation, method of randomisation, randomisation concealment, blinding, time of follow‐up, loss to follow‐up, country conducted in, number of centres, recruitment period and funding source.

Participants: sampling frame, diagnostic criteria, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, number of participants in each group, baseline group demographics and clinical diagnosis.

Intervention: type of antibiotic, dose, frequency and duration of course. Information about co‐interventions, for example, surgical treatment or analgesia.

Outcomes: primary outcomes at 24, 48 and 72 hours and 7 days, and secondary outcomes as previously described (see Primary outcomes; Secondary outcomes).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (ALC and IGC) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies and resolved any disagreements by discussion. We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each included study following the recommended methods for assessing the risk of bias in studies included in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This was a two‐part tool addressing specific key domains including sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other bias. We tabulated relevant information describing what happened, as reported in the study or revealed by correspondence with the study authors, for each included study, along with a judgement of low, high or unclear risk of bias for each individual domain.

A summary assessment of the risk of bias of each included study was made as follows:

low risk of bias (plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results) if we assessed all key domains to be at low risk of bias;

unclear risk of bias (plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results) if we assessed one or more key domains as unclear;

high risk of bias (plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results) if we assessed one or more key domains to be at high risk of bias.

We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each included study. We also presented the results graphically.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, we expressed the estimate of effect of the intervention as risk ratios (RR) together with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For continuous outcomes (such as mean VAS scores), we reported mean differences (MD) (or standardised mean differences (SMD) when different scales measuring the same concept) and their corresponding 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

We anticipate that, by the nature of the outcome variables being recorded, studies included in future updates may involve repeat observations. Results from more than one time point for each study cannot be combined in a standard meta‐analysis without a unit‐of‐analysis error. Therefore, we assessed outcomes at 24, 48 and 72 hours and 7 days postoperatively, as the data allowed.

We included no clustered trials in the review.

Given the nature of the conditions and intervention under review, it is high unlikely any cross‐over trials will be suitable for inclusion in the future.

In updates, we will consider multi‐arm studies for inclusion in the review, in accordance with recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), we will combine all relevant experimental groups and considered them as a single group and compared them with a combined group of all the control groups, if present.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the original investigators in cases of missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to assess heterogeneity using the Chi2 test (P value < 0.10 regarded as statistically significant). For studies judged as clinically homogeneous, we test heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The I2 statistic describes the percentage of variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. An I2 of 0% to 40% might not be important, 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, 50% to 90% may have substantial heterogeneity, and 75% to 100% studies has substantial heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We examined within‐study selective outcome reporting as a part of the overall risk of bias assessment and contacted study authors for clarification.

If there had been at least 10 studies included in a meta‐analysis, we would have assessed between‐study reporting bias by creating a funnel plot of effect estimates against their standard errors. If we had found asymmetry of the funnel plot by inspection and confirmed this by statistical tests, we would have considered possible explanations and taken into account in the interpretation of the overall estimate of treatment effects.

Data synthesis

We only carried out meta‐analysis where studies of similar comparisons, reported similar outcomes, for people with similar clinical conditions. We combined MDs (or SMDs where studies had used different scales) for continuous outcomes, and combined RRs for dichotomous outcomes, using a fixed‐effect model if there were only two or three studies, or a random‐effects model if there were four or more studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to investigate clinical heterogeneity by examining the following subgroups should sufficient data have been available.

Different antibiotic class (e.g. penicillins versus macrolides).

The effects of accompanying surgical intervention (extraction, incision and drainage or endodontic treatment).

Sensitivity analysis

Provided there were sufficient studies for each outcome and intervention, we had planned to undertake sensitivity analysis based on trials judged to be of low risk of bias.

Presentation of main results

We developed a 'Summary of findings' table for the primary outcomes of this review using GRADEPro software (GRADEpro GDT 2015), with the GRADE assessment of the quality of the body of evidence.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

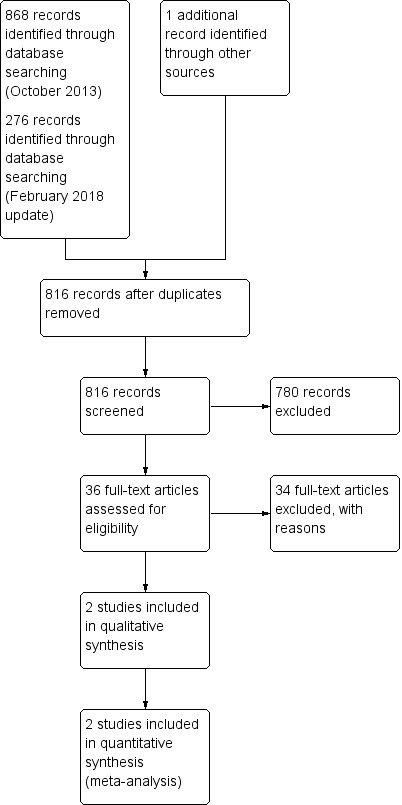

After de‐duplication, the electronic searches conducted in 2013 yielded 625 references. We identified one additional trial by checking the bibliographies of the selected trials and reviews (Al‐Belasy 2003). After examination of the titles, and abstracts where available, we excluded 590 references from further analysis. We obtained full‐text copies of the remaining 36 trials, translated them where required, and subjected them to further evaluation. At this stage, we excluded 34 studies and recorded their characteristics (Characteristics of excluded studies).

After de‐duplication, the electronic searches conducted for the current update (February 2018) yielded an additional 190 references not included in the previously published version. We retrieved no additional citations from other sources. After examination of the titles and abstracts where available, we excluded all 190 references from further analysis (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) satisfied the inclusion criteria (Fouad 1996; Henry 2001). See Characteristics of included studies table for further details.

Characteristics of trial designs and settings

Both studies were of parallel group design, one had three arms (Fouad 1996), and the other had two arms (Henry 2001). Both studies were conducted at university dental schools in the USA and based at a single centre. One study was supported by a university research fund and the other did not declare funding sources. Neither study reported sample size calculations.

Characteristics of participants

We included 62 participants in the analysis for this review, with 21 people analysed in Fouad 1996, and 41 people analysed in Henry 2001. Both studies were conducted on otherwise healthy adults.

Participants in one study had a mean age of 36 years (standard deviation (SD) 13.7 years) and had a clinical diagnosis of acute apical abscess with pulpal necrosis, periapical pain or swelling, or both (Additional Table 2; Fouad 1996). Potential participants were excluded if their temperature was elevated (judged by investigators to be above 100 °F (37.8 °C) or if they had was malaise or fascial space involvement.

1. Baseline characteristics for penicillin and placebo trial arms (Fouad 1996).

| Trial arm | Penicillin (n = 13) | Placebo (n = 15) | P value |

| Gender | 4W:8Ma | 6W:7Mb | ‐ |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 34.92 (17.33) | 37.17 (9.40) | 0.696 |

| Mean baseline pain (SD) | 2.40 (1.08) | 2.00 (1.10) | 0.410 |

| Mean baseline swelling (SD) | 1.91 (1.51) | 2.00 (1.48) | 0.866 |

M: men; n: number in group; SD: standard deviation; W: women. Unpublished data from personal communication. aGender of 1 participant not recorded. bGender of 2 participants not recorded.

Participants in the other study had a mean age of 37 years (SD 16.5 years) in the penicillin arm and 38 years (SD 18.8 years) in the placebo arm (Additional Table 3; Henry 2001). All had a symptomatic necrotic tooth with a periapical radiolucency and no mucosal sinus tract (Henry 2001).

2. Baseline characteristics for penicillin and placebo trial arms (Henry 2001).

| Variable | Penicillin (n = 19) | Placebo (n = 22) | P value |

| Age in years (SD) | 37 (16.5) | 38 (18.8) | 0.884 |

| Gender | 10W:9M | 10W:12M | 0.647 |

| Weight in pounds (SD) | 172 (28.4) | 170 (41.3) | 0.874 |

| Estimated lesion area in mm (SD) | 14.0 (16.5) | 24.8 (22.6) | 0.105 |

| Median baseline pain (SD) | 2.00 (2.00) | 2.00 (1.00) | 0.463 |

| Median baseline percussion pain (SD) | 2.00 (2.00) | 2.00 (2.00) | 0.868 |

| Median baseline swelling (SD) | 1.00 (2.00) | 0 (1.00) | 0.097 |

M: men; n: number in group; SD: standard deviation; W: women.

One trial had more male participants (Fouad 1996) and the other had similar numbers of male and female participants (Henry 2001). There were no significant differences in the intra‐study baseline characteristics of participants (Additional Table 2; Additional Table 3).

Characteristics of intervention

Objective 1: systemic antibiotics versus a matched placebo provided in conjunction with a surgical intervention

In one trial, participants underwent total or partial pulpectomy under local anaesthesia with temporary restoration at the baseline visit (Fouad 1996). In the other trial, all participants underwent total pulpectomy with temporary restoration at the baseline visit (Henry 2001).

In the study by Fouad 1996, participants in the penicillin group received oral penicillin (phenoxymethyl) VK 1 g following treatment and then 500 mg, every 6 hours for 7 days. Participants in the placebo group received an oral matched placebo taken according to the same regimen. In the trial by Henry 2001, participants in the penicillin group received 500 mg oral penicillin VK tablets (Wyeth Laboratories, Philadelphia, PA) which they were instructed to take every 6 hours for 7 days. Participants in the placebo group received an oral matched placebo (lactose) taken according to the same regimen.

In one trial, all participants also received ibuprofen 600 mg immediately before treatment, on four occasions during the next 24 hours, and then as required (Fouad 1996). In the other trial, all participants received a bottle of ibuprofen 200 mg tablets (Advil, Whitehall Laboratories, New York, NY) with instructions to take two tablets every 4 to 6 hours as required. Each participant also received a labelled bottle of paracetamol (acetaminophen) with codeine (Tylenol #3, McNeil Consumer Products, Fort Washington, PA) with dosing instructions, to take if two ibuprofen did not relieve their discomfort. One participant was given Percocet (oxycodone plus paracetamol (acetaminophen)) instead (Henry 2001).

Objective 2: systemic antibiotics versus a matched placebo provided without a surgical intervention

We found no studies comparing systemic antibiotics versus a matched placebo provided without a surgical intervention.

Heterogeneity of interventions

There was heterogeneity with respect to the operative treatment, doses of antibiotics given to participants in the intervention arms and type, dose and frequency of analgesics provided to participants between the two studies.

Characteristics of the outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Both studies reported participant‐reported pain. Both utilised a short ordinal numerical scale graded from 0 to 3. In Fouad 1996, this score was determined by converting the value from a VAS on the post‐treatment card into a whole number rank. Pain was measured at the following data points:

6 hours, 12 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours (Fouad 1996);

day 1, day 2, day 3, day 4, day 5, day 6, day 7 (Henry 2001).

Both studies also reported participant‐reported swelling. In Henry 2001, investigators utilised a short ordinal numerical scale graded from 0 to 3. In Fouad 1996, increase or decrease in swelling compared with baseline was recorded on a short ordinal numerical scale graded from 0 to 4. Swelling was measured at the following data points:

6 hours, 12 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours (Fouad 1996);

day 1, day 2, day 3, day 4, day 5, day 6, day 7 (Henry 2001).

One study included percussion pain (Henry 2001). This was measured on a short ordinal numerical scale graded from 0 to 3.

One study included incidence of endodontic flare‐up (Fouad 1996). This was measured dichotomously and was clinician‐assessed based on the presence of: no relief or an increase in the severity of pain; no resolution or an increase in the size of swelling, fever, trismus or difficulty swallowing; signs of a drug allergy or any other abnormal symptoms.

Secondary outcomes

One study included the number and type of analgesics required (Henry 2001). In Fouad 1996, participants recorded whether they required additional analgesia; however, this information was not reported and was not available after contacting the investigators.

One study reported adverse effects (Fouad 1996).

Handling of data/data assumptions made in the review

For objective 1, we compared pain and swelling scores at 24, 48 and 72 hours and 7 days postoperatively. For the purposes of the analysis, we made the assumption that the data points from Henry 2001 (day 1, day 2 and day 3) were sufficiently analogous to those measure in Fouad 1996 to be combined.

Excluded studies

We excluded the majority of references as they were not RCTs. Other excluded studies did not report relevant health outcomes, had no placebo control or had other characteristics that did not satisfy the inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies table).

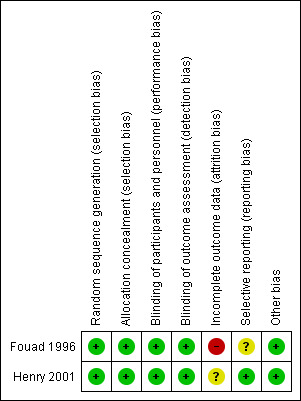

Risk of bias in included studies

The review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study are given in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Randomisation

We considered both studies to be at low risk of bias for random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment

We assessed both studies to have adequate concealment of allocation prior to assignment. In Fouad 1996, individuals enrolling participants into the trial were not aware of the upcoming allocation sequence; envelopes were sequentially numbered, opaque and sealed; envelopes for the penicillin and placebo groups were identical in appearance and weight and were only opened after being assigned to the participant. In Henry 2001, participants were given sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance in accordance with the randomisation sequence produced prior to the experiment.

Blinding

We judged both studies to have employed adequate measures to ensure that active and placebo tablets had identical appearance, and, therefore, we considered risk of performance bias to be low for both studies. Similarly, we considered both studies to have low risk of detection bias as blinding was unlikely to have been broken.

Incomplete outcome data

We considered Fouad 1996 to be at high risk of attrition bias. Rates of withdrawal were in excess of 20% in across groups, with higher rates of withdrawal from the placebo than the penicillin group. We judged differential attrition as likely to be related to treatment outcomes. In Henry 2001, we were unable to judge risk of bias due to insufficient reporting of relative attrition rates and reasons for withdrawal and, therefore, this risk for this domain is 'unclear'.

Selective reporting

We judged one study to be at unclear risk of reporting bias, as investigators did not report whether the need for additional analgesia differed between the two trial arms, although this information was collected on the post‐treatment card (Fouad 1996). There was no evidence of selective reporting within Henry 2001 and all expected outcomes were presented. We judged this study to be at low risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged both trials to be at low risk of other potential sources of bias.

Overall risk of bias

One study had high overall risk of bias (Fouad 1996), and one had unclear risk of bias (Henry 2001) (Figure 2).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Objective 1: systemic antibiotics versus a matched placebo provided in conjunction with a surgical intervention

Two studies, one at unclear risk of bias (Henry 2001), and one at high risk of bias (Fouad 1996), provided data for this comparison. Both compared oral penicillin V potassium K (penicillin VK) against a matched placebo when provided alongside partial or total pulpectomy for adults with localised acute apical abscess or symptomatic necrotic tooth in otherwise healthy adults.

Primary outcomes

Pain

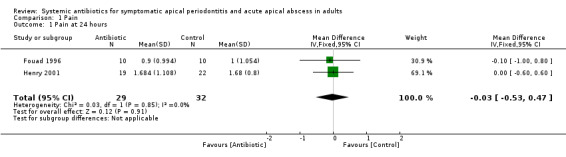

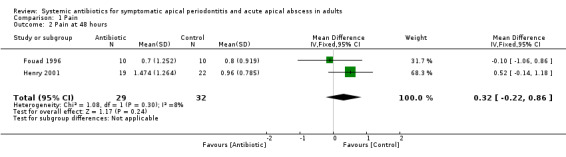

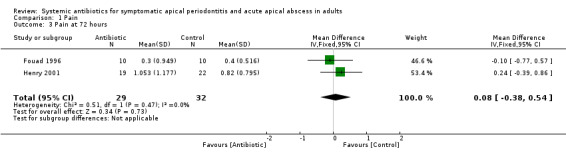

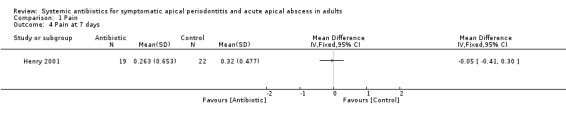

The analysis of participant‐reported pain at data points 24, 48 and 72 hours was based on data from two studies (61 participants), one at high risk of bias (Fouad 1996), and one at unclear risk of bias (Henry 2001). Analysis of the 7‐day time point was based on data from one study (41 participants) at unclear risk of bias (Henry 2001).

For the antibiotic group:

mean difference (MD) at 24 hours ‐0.03 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.53 to 0.47);

MD at 48 hours 0.32 (95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.86);

MD at 72 hours 0.08 (95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.54);

MD at 7 days ‐0.05 (95% CI ‐0.41 to 0.30, P value = 0.77).

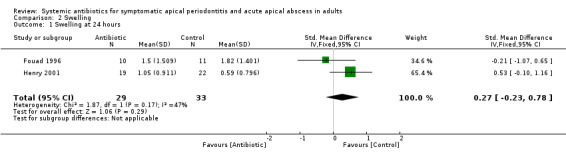

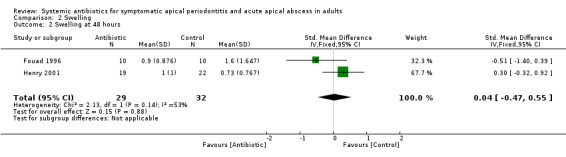

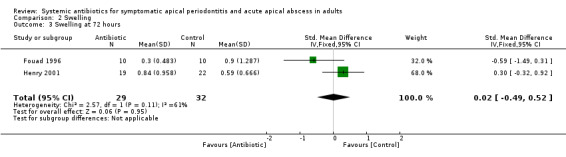

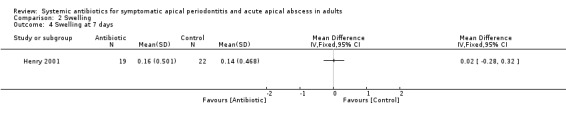

Swelling

The analysis of participant‐reported swelling at data points 24 hours (61 participants), 48 hours (62 participants) and 72 hours (61 participants) was based on data from two studies, one at high risk of bias (Fouad 1996), and one at unclear risk of bias (Henry 2001). Analysis of 7‐day time point was based on data from one study at unclear risk of bias (Henry 2001). Standardised mean difference (SMD) was used to combine the different scales used for the 24‐, 48‐ and 72‐hour data points.

For the antibiotic group:

SMD at 24 hours 0.27 (95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.78). This converts back into a 36% increase (95% CI 31% decrease to 105% increase) of control mean for antibiotics. Re‐expressed from the SMD into the short ordinal numerical scale used by Henry 2001. Results should be interpreted with caution since back‐translation of the effect size was based on the results of only one study;

SMD at 48 hours 0.04 (95% CI ‐0.47 to 0.55). This converts back into a 4% increase (95% CI 49% decrease to 58% increase) of control mean for antibiotics. Re‐expressed from the SMD into the short ordinal numerical scale used by Henry 2001. Results should be interpreted with caution since back‐translation of the effect size was based on the results of only one study;

SMD at 72 hours 0.02 (95% CI ‐0.49 to 0.52). This converts back into a 2% increase (95% CI 55% decrease to 59% increase) of control mean for antibiotics. Re‐expressed from the SMD into the short ordinal numerical scale used by Henry 2001. Results should be interpreted with caution since back‐translation of the effect size was based on the results of only one study;

MD at 7 days 0.02 (95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.32, P value = 0.90).

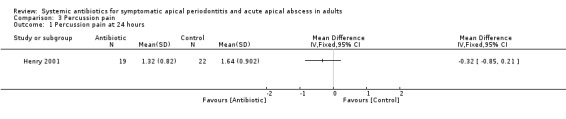

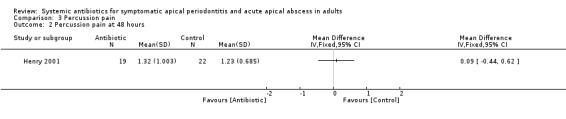

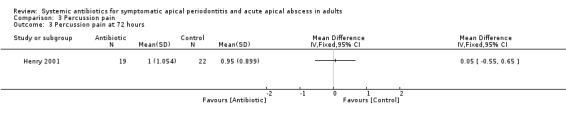

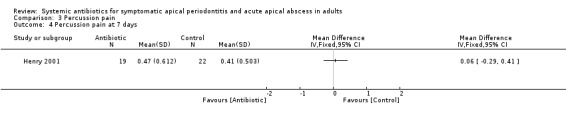

Percussion pain

The analysis of participant‐reported percussion data at data points 24, 48 and 72 hours was based on data from one study (41 participants) at unclear risk of bias (Henry 2001).

For the antibiotic group:

MD at 24 hours ‐0.32 (95% CI ‐0.85 to 0.21, P value = 0.24);

MD at 48 hours 0.09 (95% CI ‐0.44 to 0.62, P value = 0.74);

MD at 72 hours 0.05 (95% CI ‐0.55 to 0.65, P value = 0.87);

MD at 7 days 0.06 (95% CI ‐0.29 to 0.41, P value = 0.73).

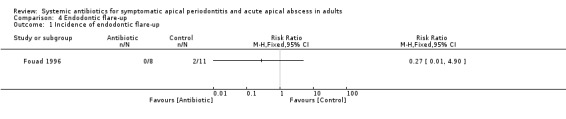

Endodontic flare‐up

The analysis of clinician‐assessed incidence of endodontic flare‐up over 3‐day follow‐up period was based on data from one study at high risk of bias (20 participants) (Fouad 1996).

For the antibiotic group:

risk ratio (RR) of endodontic flare‐up 0.27 (95% CI 0.01 to 4.90, P value = 0.37).

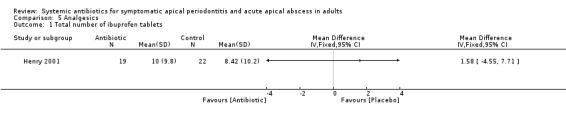

Secondary outcomes

Analgesics

The analysis of the number of analgesic tablets required during the 7‐day follow‐up period was based on data from one study (41 participants) at unclear risk of bias (Henry 2001).

For the antibiotic group:

MD for total number of ibuprofen tablets 1.58 (95% CI ‐4.55 to 7.71, P value = 0.62).

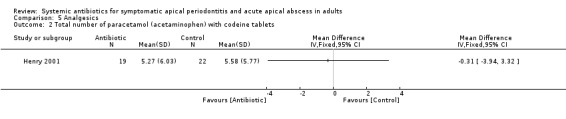

MD for total number of paracetamol (acetaminophen) with codeine tablets ‐0.31 (95% CI ‐3.94 to 3.32, P value = 0.87).

Adverse effects

During the 3‐day follow‐up period in Fouad 1996 (20 participants, high risk of bias), one participant in the placebo group reported diarrhoea and one participant in the antibiotic group reported fatigue and reduced energy postoperatively.

Objective 2: systemic antibiotics versus a matched placebo provided without a surgical intervention

We found no studies comparing systemic antibiotics versus a matched placebo provided without a surgical intervention.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The review process identified two studies suitable for inclusion, both of which assessed the effects of penicillin VK compared with a matched placebo in adults with localised apical abscess or a symptomatic necrotic tooth (no signs of spreading infection or systemic involvement) when provided in conjunction with partial or total pulpectomy conducted under local anaesthesia, and oral analgesics. There were no statistically significant differences in primary outcomes (participant‐reported pain, swelling or percussion pain or incidence of endodontic flare‐up) or secondary outcomes (analgesic use or incidence of adverse events) between participants who had received antibiotics and participants who had received a matched placebo. We considered this body of evidence (two studies, one at unclear risk of bias and one at high risk of bias) to be of very low quality and therefore the results should be interpreted with caution.

We found no studies that reported the effects of systemic antibiotics versus a matched placebo for symptomatic apical periodontitis when provided in conjunction with a surgical intervention. We found no studies that reported the effects of systemic antibiotics versus a matched placebo for symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess when provided without a surgical intervention.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We employed a comprehensive search strategy and we are confident that the majority of published trials are included in this review. We made efforts to identify all relevant studies and excluded no studies due to language.

The two included trials partially addressed the first of the two objectives (Fouad 1996; Henry 2001), which both investigated the effect of systemic antibiotics for acute apical abscess or symptomatic necrotic tooth provided in conjunction with total or partial pulpectomy in adults. However, there were no trials that assessed the effects of antibiotics for symptomatic apical periodontitis when used in conjunction with a surgical intervention. Furthermore, we found no trials assessing the second objective, which sought to compare antibiotics and a placebo for symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess when provided without a surgical intervention.

The participants included in the two trials can be considered broadly representative of people who would consult a dentist due to an acute apical abscess or symptomatic necrotic tooth who do not have evidence of spreading infection or systemic involvement: participants came from a wide age range, were about equal gender mix and the majority had moderate pain at the baseline visit. However, both the trials excluded participants with co‐morbidities or who may have been immunocompromised. Therefore, the results of this review may not be generalisable to a group of people who may be at higher risk of infection. While future trials should endeavour to obtain a representative sample, it is unlikely to be feasible or ethical to conduct placebo‐controlled trials in these groups of people.

One trial excluded participants with signs of spreading infection and systemic involvement (Fouad 1996), and the other trial included only a small number of participants with evidence of severe infections at baseline (Henry 2001). Therefore, the results of this review may not be generalisable to people with severe swelling or other signs of spreading infection or systemic involvement.

Both of the included studies were conducted at university dental schools and, in both trials, endodontic treatment was completed by practitioners who either worked in the Department of Endodontics (Fouad 1996), or were senior endodontic graduate students (Henry 2001). It would be reasonable to consider that both groups of practitioners had endodontic skills in excess of those of an average primary care dentist. The specialist settings in which the trials were conducted were also unlikely to face the time constraints encountered in routine clinical practice. Therefore, the intervention provided within these studies may only have limited applicability to the treatment routinely provided at emergency appointments in general dental practice, where treatment decisions are often dictated by time pressures (Palmer 2000). Therefore, more trials in a primary care setting would enhance the evidence base for answering the questions posed by this review.

We found no trials assessing the effect of other surgical interventions, such as dental extraction, or incision and drainage of a swelling. Since dental extraction is a common treatment for both symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess (Cope 2016), the effects of this intervention could be considered in future trials.

The outcomes reported by the two trials measured the harms as well as the benefits of interventions. This is important as antibiotics can have adverse effects such as hypersensitivity reactions, gastrointestinal upset, and the risk of development of antibiotic‐resistant bacterial colonies. Many of the outcome measures in the two included trials were participant‐centred, such as pain, percussion pain and swelling. Since both pain and discomfort are known to impact an individual's quality of life (Skevington 1998), future trials should also consider formally measuring oral health‐related quality of life outcomes to assess the beneficial and harmful effects of this intervention in more detail.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence, as summarised in Table 1 for the main comparison, was rated as very low.

Given the considerable number of antibiotics prescribed by dentists to adults with acute dental conditions and the problems associated with indiscriminate use of antibiotics, the paucity of high‐quality trials evaluating the effects of systemic antibiotics in the management of symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess is disappointing. Only two studies met the inclusion criteria for this review; we judged one to be at high risk of bias and the other to be of unclear risk of bias. Both had methodological flaws with respect to attrition bias, and the overall quality of evidence was very low. Furthermore, small group sizes mean that both studies were likely to lack the statistical power to detect differences between intervention and placebo groups. Sample size calculations were not reported in either study. Therefore, caution should be exercised when interpreting the results presented in this review.

Potential biases in the review process

Two independent review authors extracted data and assessed the methodological quality of each study, minimising potential bias.

We are confident that the extensive literature search used in this review has captured relevant literature and minimised the likelihood that we missed any relevant trials. We applied no language or publication restrictions in our search.

In the event of incomplete or unclear reporting of trial data, we contacted the trial authors to obtain any unpublished data or clarification of results.

Despite these efforts, it must be acknowledged that there is a small possibility that there were additional studies (published and unpublished) that we did not identify. It is possible that additional literature searches, such as searching non‐English language databases and handsearching relevant journals, would have found additional studies.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Systematic reviews of the emergency management of acute apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess in the permanent dentition were published in 2003 (Matthews 2003; Sutherland 2003). These reviews had wider inclusion criteria and included trials of analgesics, local pharmacotherapeutics and surgical interventions in addition to antibiotic trials. Sutherland 2003 concluded that "the use of antibiotics in the management of AAP [acute apical periodontitis] is not recommended" and Matthews 2003 recommended that "the use of antibiotics in the management of localized AAA [acute apical abscess] over and above establishing drainage of the abscess, is not recommended".

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Based on the current available data, which are of very low quality, there was insufficient evidence to determine the effects of the administration of systemic antibiotics to adults with symptomatic apical periodontitis or acute apical abscess.

Since antibiotic use is recognised as a major contributor to antimicrobial resistance, dental professionals should be judicious in their use of these agents and should refer to evidence‐based best practice guidelines when managing people with acute dental conditions.

Implications for research.

Large‐scale, adequately powered and well‐designed randomised controlled trials are needed to clarify the effectiveness of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess. However, all future trials should be carefully designed to ensure the potential benefits of providing systemic antibiotics to participants outweigh risks associated with antibiotic usage, both adverse effects and the possible contribution to antibiotic resistance.

Future studies should consider both utilising validated participant‐ and clinician‐reported outcome measures, and report results according to CONSORT guidelines (www.consort‐statement.com/).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 August 2018 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions are the same. Change of review authors. |

| 26 February 2018 | New search has been performed | Searches updated. No additional eligible studies identified. |

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the following help in the conduct of the review.

Anne Littlewood, Information Specialist of Cochrane Oral Health, who provided invaluable support in constructing and running the search strategies.

Mala Mann, Specialist Unit for Review Evidence, Cardiff University, who was involved in the original review. Mala drafted the protocol, screened search results, extracted the data, performed risk of bias assessment and was involved in writing the final report of the 2014 review.

Dr Rebecca Payle, Senior Lecturer in Medical Statistics at Cardiff University School of Dentistry, who gave advice on the statistical elements of the protocol.

Anwen L Cope would like to acknowledge the financial support received from a Clinical Research Time Award from Health and Care Wales.

The assistance of several colleagues who helped with translating articles during the selection of studies.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register search strategy

From October 2013, searches of Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register were conducted for this review using the Cochrane Register of Studies and the search strategy below:

1. ((antibiotic* or anti‐biotic* or "anti biotic*" or antibacterial* or anti‐bacterial* or "anti bacterial*" or antiinfect* or anti‐infect* or "anti infect*" or antimicrobial* or anti‐microbial* or "anti microbial*"):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 2. ((penicillin* or amoxicillin or amoxycillin or co‐amoxiclav or ampicillin or erythromycin or clindamycin*):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 3. ((doxycycline* or metronidazole or azithromycin or co‐amoxiclav or oxytetracycline or cefalexin or cephalexin or cefradine or cephradine or clarithromycin):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 4. ((tetracycline or actimoxi or amoxicilline or amoxil or BRL‐2333 or clamoxyl or hydroxyampicillin or penamox or polymox or trimox or wymox or amoxi‐clav or amoxi‐clavulanate or augmentin or BRL‐25000):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 5. ((clavulanate or clavulin or coamoxiclav or spektramox or synulox or phenoxymethylpenicillin or apocillin or beromycin or berromycin or betapen or fenoxymethylpenicillin or "Pen VK" or "v‐cillin K" or vegacillin or clont or danizol ):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 6. ((trichazol* or trichapol or trivazol or satric or metrogyl or flagyl or gineflavir or metrodzhil or nidagyl or chlolincocin or chlorlincocin or cleocin or "dalacin c"):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 7. (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6) AND (INREGISTER) 8. ((abscess* or periapical or peri‐apical or “peri apical”):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) 9. (#7 and #8) AND (INREGISTER)

A previous search of Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register was conducted in June 2012, using the Procite software and the search strategy below:

((antibiotic* or anti‐biotic* or "anti biotic*" or antibacterial* or anti‐bacterial* or "anti bacterial*" or antiinfect* or anti‐infect* or "anti infect*" or antimicrobial* or anti‐microbial* or "anti microbial*" or penicillin* or amoxicillin or amoxycillin or co‐amoxiclav or ampicillin or erythromycin or clindamycin* or doxycycline* or metronidazole or azithromycin or co‐amoxiclav or oxytetracycline or cefalexin or cephalexin or cefradine or cephradine or clarithromycin or tetracycline or actimoxi or amoxicilline or amoxil or BRL‐2333 or clamoxyl or hydroxyampicillin or penamox or polymox or trimox or wymox or amoxi‐clav or amoxi‐clavulanate or augmentin or BRL‐25000 or clavulanate or clavulin or coamoxiclav or spektramox or synulox or phenoxymethylpenicillin or apocillin or beromycin or berromycin or betapen or fenoxymethylpenicillin or "Pen VK" or "v‐cillin K" or vegacillin or clont or danizol or trichazol* or trichapol or trivazol or satric or metrogyl or flagyl or gineflavir or metrodzhil or nidagyl or chlolincocin or chlorlincocin or cleocin or "dalacin c") AND abscess* or periapical or peri‐apical or "peri apical"))

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Anti‐Infective Agents explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Penicillins explode all trees #3 (antibiotic* in All Text or anti‐biotic* in All Text or "anti biotic*" in All Text) #4 (antibacterial* in All Text or anti‐bacterial* in All Text or "anti bacterial*" in All Text) #5 (antiinfect* in All Text or anti‐infect* in All Text or "anti infect*" in All Text) #6 (antimicrobial* in All Text or anti‐microbial* in All Text or "anti microbial*" in All Text) #7 (penicillin* in All Text or amoxicillin in All Text or amoxycillin in All Text or co‐amoxiclav in All Text or ampicillin in All Text or erythromycin in All Text or clindamycin* in All Text or doxycycline* in All Text or metronidazole in All Text or azithromycin in All Text or co‐amoxiclav in All Text or oxytetracycline in All Text or cefalexin in All Text or cephalexin in All Text or cefradine in All Text or cephradine in All Text or clarithromycin in All Text or tetracycline in All Text) #8 (actimoxi in All Text or amoxicilline in All Text or amoxil in All Text or BRL‐2333 in All Text or clamoxyl in All Text or hydroxyampicillin in All Text or penamox in All Text or polymox in All Text or trimox in All Text or wymox in All Text or amoxi‐clav in All Text or amoxi‐clavulanate in All Text or augmentin in All Text or BRL‐25000 in All Text or clavulanate in All Text or clavulin in All Text or coamoxiclav in All Text or spektramox in All Text or synulox in All Text) #9 (phenoxymethylpenicillin in All Text or apocillin in All Text or beromycin in All Text or berromycin in All Text or betapen in All Text or fenoxymethylpenicillin in All Text or "Pen VK" in All Text or "v‐cillin K" in All Text or vegacillin in All Text) #10 (clont in All Text or danizol in All Text or trichazol* in All Text or trichapol in All Text or trivazol in All Text or satric in All Text or metrogyl in All Text or flagyl in All Text or gineflavir in All Text or metrodzhil in All Text or nidagyl in All Text) #11 (chlolincocin in All Text or chlorlincocin in All Text or cleocin in All Text or "dalacin c" in All Text) #12 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11) #13 MeSH descriptor Periapical diseases explode all trees #14 (dental* in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) #15 ( (tooth in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) or (teeth in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) ) #16 ( (periapical in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) or (peri‐apical in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) or (apical in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) ) #17 ( (periapical in All Text near/5 periodont* in All Text) or (peri‐apical in All Text near/5 periodont* in All Text) or (apical in All Text near/5 periodont* in All Text) ) #18 ( (periapical in All Text near/5 inflam* in All Text) or (peri‐apical in All Text near/5 inflam* in All Text) or (apical in All Text near/5 inflam* in All Text) ) #19 ( (periapical in All Text near/5 infect* in All Text) or (peri‐apical in All Text near/5 infect* in All Text) or (apical in All Text near/5 infect* in All Text) ) #20 ( (dentoalveol* in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) or (dento‐alveol* in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) or (alveol* in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) ) #21 ( (periradicular in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) or (peri‐radicular in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) or (radicular in All Text near/5 absces* in All Text) ) #22 (#13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21) #23 (#12 and #22)

MEDLINE Ovid search strategy

1. exp Anti‐Infective Agents/ 2. exp Penicillins/ 3. (antibiotic$ or anti‐biotic$ or "anti biotic$").tw. 4. (antibacterial$ or anti‐bacterial$ or "anti bacterial$").tw. 5. (antiinfect$ or anti‐infect$ or "anti infect$").tw. 6. (antimicrobial$ or anti‐microbial$ or "anti microbial$").tw. 7. (penicillin$ or amox?cillin or co‐amoxiclav or ampicillin or erythromycin or clindamycin$ or doxycycline$ or metronidazole or azithromycin or co‐amoxiclav or oxytetracycline or cefalexin or cephalexin or cefradine or cephradine or clarithromycin or tetracycline).tw. 8. (actimoxi or amoxicilline or amoxil or BRL‐2333 or clamoxyl or hydroxyampicillin or penamox or polymox or trimox or wymox or amoxi‐clav or amoxi‐clavulanate or augmentin or BRL‐25000 or clavulanate or clavulin or coamoxiclav or spektramox or synulox).tw. 9. (phenoxymethylpenicillin or apocillin or beromycin or berromycin or betapen or fenoxymethylpenicillin or "Pen VK" or "v‐cillin K" or vegacillin).tw. 10. (clont or danizol or trichazol$ or trichapol or trivazol or satric or metrogyl or flagyl or gineflavir or metrodzhil or nidagyl).tw. 11. (chlolincocin or chlorlincocin or cleocin or "dalacin c").tw. 12. or/1‐11 13. exp Periapical diseases/ 14. (dental$ adj5 absces$).tw. 15. ((tooth or teeth) adj5 absces$).tw. 16. ((periapical adj5 absces$) or (peri‐apical adj5 absces$) or (apical adj5 absces$)).tw. 17. ((periapical adj5 periodont$) or (peri‐apical adj5 periodont$) or (apical adj5 periodont$)).tw. 18. ((periapical adj5 inflam$) or (peri‐apical adj5 inflam$) or (apical adj5 inflam$)).tw. 19. ((periapical adj5 infect$) or (peri‐apical adj5 infect$) or (apical adj5 infect$)).tw. 20. ((dentoalveol$ adj5 absces$) or (dento‐alveol$ adj5 absces$) or (alveol$ adj5 absces$)).tw. 21. ((periradicular adj5 absces$) or (peri‐radicular adj5 absces$) or (radicular adj5 absces$)).tw. 22. or/13‐21 23. 12 and 22

The above subject search was linked to the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (CHSSS) for identifying randomised trials (RCTs) in MEDLINE: sensitivity maximising version (2008 revision) as referenced in Chapter 6.4.11.1 and detailed in box 6.4.c of theCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) (Lefebvre 2011).

1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. controlled clinical trial.pt. 3. randomized.ab. 4. placebo.ab. 5. drug therapy.fs. 6. randomly.ab. 7. trial.ab. 8. groups.ab. 9. or/1‐8 10. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 11. 9 not 10

Embase Ovid search strategy

1. exp Antiinfective agent/ 2. exp Penicillin derivate/ 3. (antibiotic$ or anti‐biotic$ or "anti biotic$").tw. 4. (antibacterial$ or anti‐bacterial$ or "anti bacterial$").tw. 5. (antiinfect$ or anti‐infect$ or "anti infect$").tw. 6. (antimicrobial$ or anti‐microbial$ or "anti microbial$").tw. 7. (penicillin$ or amox?cillin or co‐amoxiclav or ampicillin or erythromycin or clindamycin$ or doxycycline$ or metronidazole or azithromycin or co‐amoxiclav or oxytetracycline or cefalexin or cephalexin or cefradine or cephradine or clarithromycin or tetracycline).tw. 8. (actimoxi or amoxicilline or amoxil or BRL‐2333 or clamoxyl or hydroxyampicillin or penamox or polymox or trimox or wymox or amoxi‐clav or amoxi‐clavulanate or augmentin or BRL‐25000 or clavulanate or clavulin or coamoxiclav or spektramox or synulox).tw. 9. (phenoxymethylpenicillin or apocillin or beromycin or berromycin or betapen or fenoxymethylpenicillin or "Pen VK" or "v‐cillin K" or vegacillin).tw. 10. (clont or danizol or trichazol$ or trichapol or trivazol or satric or metrogyl or flagyl or gineflavir or metrodzhil or nidagyl).tw. 11. (chlolincocin or chlorlincocin or cleocin or "dalacin c").tw. 12. or/1‐11 13. exp Tooth periapical disease/ 14. (dental$ adj5 absces$).tw. 15. ((tooth or teeth) adj5 absces$).tw. 16. ((periapical adj5 absces$) or (peri‐apical adj5 absces$) or (apical adj5 absces$)).tw. 17. ((periapical adj5 periodont$) or (peri‐apical adj5 periodont$) or (apical adj5 periodont$)).tw. 18. ((periapical adj5 inflam$) or (peri‐apical adj5 inflam$) or (apical adj5 inflam$)).tw. 19. ((periapical adj5 infect$) or (peri‐apical adj5 infect$) or (apical adj5 infect$)).tw. 20. ((dentoalveol$ adj5 absces$) or (dento‐alveol$ adj5 absces$) or (alveol$ adj5 absces$)).tw. 21. ((periradicular adj5 absces$) or (peri‐radicular adj5 absces$) or (radicular adj5 absces$)).tw. 22. or/13‐21 23. 12 and 22

This subject search was linked to an adapted version of the Cochrane Centralised Search Project filter for identifying RCTs in Embase Ovid (see www.cochranelibrary.com/help/central‐creation‐details.html for information):

1. random$.ti,ab. 2. factorial$.ti,ab. 3. (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).ti,ab. 4. placebo$.ti,ab. 5. (doubl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. 6. (singl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. 7. assign$.ti,ab. 8. allocat$.ti,ab. 9. volunteer$.ti,ab. 10. CROSSOVER PROCEDURE.sh. 11. DOUBLE‐BLIND PROCEDURE.sh. 12. RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.sh. 13. SINGLE BLIND PROCEDURE.sh. 14. or/1‐13 15. (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.) 16. 14 NOT 15

CINAHL EBSCO search strategy

S1 (MH "Antiinfective Agents+") S2 (MH "Penicillins+") S3 (antibiotic* or anti‐biotic* or "anti biotic*") S4 (antibacterial* or anti‐bacterial* or "anti bacterial*") S5 (antiinfect* or anti‐infect* or "anti infect*") S6 (antimicrobial* or anti‐microbial* or "anti microbial*") S7 (penicillin* or amoxicillin or amoxycillin or co‐amoxiclav or ampicillin or erythromycin or clindamycin* or doxycycline* or metronidazole or azithromycin or co‐amoxiclav or oxytetracycline or cefalexin or cephalexin or cefradine or cephradine or clarithromycin or tetracycline) S8 (actimoxi or amoxicilline or amoxil or BRL‐2333 or clamoxyl or hydroxyampicillin or penamox or polymox or trimox or wymox or amoxi‐clav or amoxi‐clavulanate or augmentin or BRL‐25000 or clavulanate or clavulin or coamoxiclav or spektramox or synulox) S9 (phenoxymethylpenicillin or apocillin or beromycin or berromycin or betapen or fenoxymethylpenicillin or "Pen VK" or "v‐cillin K" or vegacillin) S10 (clont or danizol or trichazol* or trichapol or trivazol or satric or metrogyl or flagyl or gineflavir or metrodzhil or nidagyl) S11 (chlolincocin or chlorlincocin or cleocin or "dalacin c") S12 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 S13 (MH "Periapical Diseases") S14 (dental* N5 absces*) S15 ((tooth N5 absces*) or (teeth N5 absces*)) S16 ((periapical N5 absces*) or (peri‐apical N5 absces*) or (apical N5 absces*)) S17 ((periapical N5 periodont*) or (peri‐apical N5 periodont*) or (apical N5 periodont*)) S18 ((periapical N5 inflam*) or (peri‐apical N5 inflam*) or (apical N5 inflam*)) S19 ((periapical N5 infect*) or (peri‐apical N5 infect*) or (apical N5 infect*)) S20 ((dentoalveol* N5 absces*) or (dento‐alveol* N5 absces*) or (alveol* N5 absces*)) S21 ((periradicular N5 absces*) or (peri‐radicular N5 absces*) or (radicular N5 absces*)) S22 S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 or S18 or S19 or S20 or S21 S23 S12 and S22

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (ClinicalTrials.gov) search strategy

dental abscess* AND antibiotic* dental abscess* AND penicillin* dental abscess* AND antibacterial* dental abscess* AND antimicrobial* dental abscess* AND antiinfect* periapical abscess* AND antibiotic* periapical abscess* AND penicillin* periapical abscess* AND antibacterial* periapical abscess* AND antimicrobial* periapical abscess* AND antiinfect*

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform search strategy

dental abscess AND antibiotic dental abscess AND penicillin dental abscess AND antibacterial dental abscess AND antimicrobial dental abscess AND antiinfectious periapical abscess AND antibiotic periapical abscess AND penicillin periapical abscess AND antibacterial periapical abscess AND antimicrobial periapical abscess AND antiinfectious

OpenGrey search strategy

dental abscess* AND antibiotic* dental abscess* AND penicillin* dental abscess* AND antibacterial* dental abscess* AND antimicrobial* dental abscess* AND antiinfect* periapical abscess* AND antibiotic* periapical abscess* AND penicillin* periapical abscess* AND antibacterial* periapical abscess* AND antimicrobial* periapical abscess* AND antiinfect*

ZETOC Conference Proceedings search strategy

dental abscess* AND antibiotic* dental abscess* AND penicillin* dental abscess* AND antibacterial* dental abscess* AND antimicrobial* dental abscess* AND antiinfect* periapical abscess* AND antibiotic* periapical abscess* AND penicillin* periapical abscess* AND antibacterial* periapical abscess* AND antimicrobial* periapical abscess* AND antiinfect*

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Pain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain at 24 hours | 2 | 61 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.53, 0.47] |

| 2 Pain at 48 hours | 2 | 61 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [‐0.22, 0.86] |

| 3 Pain at 72 hours | 2 | 61 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [‐0.38, 0.54] |

| 4 Pain at 7 days | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 1 Pain at 24 hours.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 2 Pain at 48 hours.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 3 Pain at 72 hours.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pain, Outcome 4 Pain at 7 days.

Comparison 2. Swelling.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Swelling at 24 hours | 2 | 62 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.27 [‐0.23, 0.78] |

| 2 Swelling at 48 hours | 2 | 61 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.04 [‐0.47, 0.55] |

| 3 Swelling at 72 hours | 2 | 61 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.49, 0.52] |

| 4 Swelling at 7 days | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Swelling, Outcome 1 Swelling at 24 hours.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Swelling, Outcome 2 Swelling at 48 hours.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Swelling, Outcome 3 Swelling at 72 hours.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Swelling, Outcome 4 Swelling at 7 days.

Comparison 3. Percussion pain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Percussion pain at 24 hours | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Percussion pain at 48 hours | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Percussion pain at 72 hours | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Percussion pain at 7 days | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Percussion pain, Outcome 1 Percussion pain at 24 hours.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Percussion pain, Outcome 2 Percussion pain at 48 hours.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Percussion pain, Outcome 3 Percussion pain at 72 hours.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Percussion pain, Outcome 4 Percussion pain at 7 days.

Comparison 4. Endodontic flare‐up.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of endodontic flare‐up | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Endodontic flare‐up, Outcome 1 Incidence of endodontic flare‐up.

Comparison 5. Analgesics.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total number of ibuprofen tablets | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Total number of paracetamol (acetaminophen) with codeine tablets | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Analgesics, Outcome 1 Total number of ibuprofen tablets.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Analgesics, Outcome 2 Total number of paracetamol (acetaminophen) with codeine tablets.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Fouad 1996.