Abstract

Background

Shared decision making (SDM) is a process by which a healthcare choice is made by the patient, significant others, or both with one or more healthcare professionals. However, it has not yet been widely adopted in practice. This is the second update of this Cochrane review.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of interventions for increasing the use of SDM by healthcare professionals. We considered interventions targeting patients, interventions targeting healthcare professionals, and interventions targeting both.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and five other databases on 15 June 2017. We also searched two clinical trials registries and proceedings of relevant conferences. We checked reference lists and contacted study authors to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

Randomized and non‐randomized trials, controlled before‐after studies and interrupted time series studies evaluating interventions for increasing the use of SDM in which the primary outcomes were evaluated using observer‐based or patient‐reported measures.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

We used GRADE to assess the certainty of the evidence.

Main results

We included 87 studies (45,641 patients and 3113 healthcare professionals) conducted mainly in the USA, Germany, Canada and the Netherlands. Risk of bias was high or unclear for protection against contamination, low for differences in the baseline characteristics of patients, and unclear for other domains.

Forty‐four studies evaluated interventions targeting patients. They included decision aids, patient activation, question prompt lists and training for patients among others and were administered alone (single intervention) or in combination (multifaceted intervention). The certainty of the evidence was very low. It is uncertain if interventions targeting patients when compared with usual care increase SDM whether measured by observation (standardized mean difference (SMD) 0.54, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.13 to 1.22; 4 studies; N = 424) or reported by patients (SMD 0.32, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.48; 9 studies; N = 1386; risk difference (RD) ‐0.09, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.01; 6 studies; N = 754), reduce decision regret (SMD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.39 to 0.19; 1 study; N = 212), improve physical (SMD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.36; 1 study; N = 116) or mental health‐related quality of life (QOL) (SMD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.46; 1 study; N = 116), affect consultation length (SMD 0.10, 95% CI ‐0.39 to 0.58; 2 studies; N = 224) or cost (SMD 0.82, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.22; 1 study; N = 105).

It is uncertain if interventions targeting patients when compared with interventions of the same type increase SDM whether measured by observation (SMD 0.88, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.37; 3 studies; N = 271) or reported by patients (SMD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.24; 11 studies; N = 1906); (RD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.08; 10 studies; N = 2272); affect consultation length (SMD ‐0.65, 95% CI ‐1.29 to ‐0.00; 1 study; N = 39) or costs. No data were reported for decision regret, physical or mental health‐related QOL.

Fifteen studies evaluated interventions targeting healthcare professionals. They included educational meetings, educational material, educational outreach visits and reminders among others. The certainty of evidence is very low. It is uncertain if these interventions when compared with usual care increase SDM whether measured by observation (SMD 0.70, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.19; 6 studies; N = 479) or reported by patients (SMD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.20; 5 studies; N = 5772); (RD 0.01, 95%C: ‐0.03 to 0.06; 2 studies; N = 6303); reduce decision regret (SMD 0.29, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.51; 1 study; N = 326), affect consultation length (SMD 0.51, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.81; 1 study, N = 175), cost (no data available) or physical health‐related QOL (SMD 0.16, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.36; 1 study; N = 359). Mental health‐related QOL may slightly improve (SMD 0.28, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.49; 1 study, N = 359; low‐certainty evidence).

It is uncertain if interventions targeting healthcare professionals compared to interventions of the same type increase SDM whether measured by observation (SMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐1.19 to 0.59; 1 study; N = 20) or reported by patients (SMD 0.24, 95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.58; 2 studies; N = 1459) as the certainty of the evidence is very low. There was insufficient information to determine the effect on decision regret, physical or mental health‐related QOL, consultation length or costs.

Twenty‐eight studies targeted both patients and healthcare professionals. The interventions used a combination of patient‐mediated and healthcare professional directed interventions. Based on low certainty evidence, it is uncertain whether these interventions, when compared with usual care, increase SDM whether measured by observation (SMD 1.10, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.79; 6 studies; N = 1270) or reported by patients (SMD 0.13, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.28; 7 studies; N = 1479); (RD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.19; 2 studies; N = 266); improve physical (SMD 0.08, ‐0.37 to 0.54; 1 study; N = 75) or mental health‐related QOL (SMD 0.01, ‐0.44 to 0.46; 1 study; N = 75), affect consultation length (SMD 3.72, 95% CI 3.44 to 4.01; 1 study; N = 36) or costs (no data available) and may make little or no difference to decision regret (SMD 0.13, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.33; 1 study; low‐certainty evidence).

It is uncertain whether interventions targeting both patients and healthcare professionals compared to interventions of the same type increase SDM whether measured by observation (SMD ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐1.17 to 0.60; 1 study; N = 20); (RD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.04; 1 study; N = 134) or reported by patients (SMD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.32 to 0.32; 1 study; N = 150 ) as the certainty of the evidence was very low. There was insuffient information to determine the effects on decision regret, physical or mental health‐related quality of life, or consultation length or costs.

Authors' conclusions

It is uncertain whether any interventions for increasing the use of SDM by healthcare professionals are effective because the certainty of the evidence is low or very low.

Plain language summary

A review of activities to help healthcare professionals share decisions about care with their patients

What is the aim of this review?

Healthcare professionals often do not involve their patients in decision making about their care. With shared decision making, healthcare professionals inform patients about their choices and invite them to choose the option that reflects what is important to them, including the option not to proceed with treatment. Shared decision making is said to be desirable because patient involvement is accepted as a right and patients in general want more information about their health condition and prefer to take an active role in decisions about their health. The aim of this review was to find out if activities to increase shared decision making by healthcare professionals are effective or not. Examples of these activities are training programs, giving out leaflets, or email reminders. Cochrane researchers collected and analyzed all relevant studies to answer this question, and found 87 studies.

Key messages

A great variety of activities exist to increase shared decision making by healthcare professionals, but we cannot be confident about which of these activities work best because the certainty (or the confidence) of the evidence has been assessed as very low.

What was studied in the review?

Our review examined the 87 studies that tested what kind of activities work best to help healthcare professionals involve their patients more in decision making about their care. We also examined the effect of these activities on decision regret, physical or mental health‐related quality of life, length of the consultation, and cost.

The studies were so different that these activities were difficult to compare.

First, we divided the studies into ones that used outside observers to measure shared decision making and ones that used patients to measure shared decision making.

We then divided studies into ones that looked at activities a) for healthcare professionals only (e.g. training), b) for patients only (e.g. giving them a decision aid, which is a pamphlet explaining options and inviting them to think about their values and preferences), and c) for both healthcare professionals and patients (e.g. training plus a decision aid).

Finally, we subdivided each of these three categories into studies that compared the activity with usual care and studies that compared the activity with another activity.

We also looked at how certain the evidence was for our primary outcome (the extent to which healthcare professionals involve their patients more in decision making about their care) and secondary outcomes (decision regret, physical or mental health‐related quality of life, length of the consultation, and cost) of interest.

What are the main results of the review?

Forty‐four studies looked at activities for patients only, while 28 studies looked at activities for both healthcare professionals and patients, and 15 studies looked at activities for healthcare professionals only.

While studies in all three categories had tested many different activities to increase shared decision making by healthcare professionals, overall we cannot be confident in the effectiveness of these activities because the certainty of the evidence was weak. This is because there were many possible sources of error (e.g. not making sure the tested activities were not also provided to the comparison groups), and often poor reporting of results (i.e. not providing enough information to judge the quality of the evidence).

Although it was hard to come to any firm conclusions, we can say that compared to no activity at all, activities for healthcare professionals may slightly improve mental health‐related quality of life, but make little or no difference to physical health‐related quality of life (two studies). We can also say that activities targeting both healthcare professionals and patients may make little or no difference to decision regret (one study).

How up‐to‐date is this review?

We searched for studies published up to June 2017.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

There is increasing recognition of the ethical imperative to share important decisions with patients (Salzburg Global Seminar 2011). Shared decision making (SDM) can be defined as an interpersonal, interdependent process in which health professionals, patients and their caregivers relate to and influence each other as they collaborate in making decisions about a patient’s health (Charles 1997; Légaré 2011; Légaré 2013; Towle 1999). It is considered the crux of patient‐centered care (Weston 2001). Briefly, SDM depends on knowing and understanding the best available evidence about the risks and benefits across all available options while ensuring that the patient's values and preferences are taken into account (Charles 1997; Elwyn 1999; Towle 1999).

Although SDM represents a complex set of behaviors that must be achieved by both members of the patient‐healthcare professional dyad (LeBlanc 2009), it is possible to specify behaviors that both parties must adopt for SDM to occur in clinical practice (Frosch 2009; Légaré 2007a). A systematic review of SDM as a concept identified 161 definitions and summarized the key elements into one integrative model of SDM in medical encounters (Makoul 2006). This model identifies nine essential elements that can be translated into specific SDM‐related behaviors that healthcare professionals need to demonstrate during consultations with patients:

define and explain the healthcare problem,

present options,

discuss pros and cons (benefits, risks, costs),

clarify patient values and preferences,

discuss patient ability and self‐efficacy,

present what is known and make recommendations,

check and clarify the patient's understanding,

make or explicitly defer a decision, and

arrange follow‐up.

Description of the intervention

A variety of interventions have been designed to change healthcare professionals' behavior. Based on the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy of interventions (EPOC 2015), these interventions aim at changing the performance of healthcare professionals through interactions with patients, or information provided by or to patients. Interventions may include, but are not limited to, the distribution of printed educational materials, educational meetings, audit and feedback, reminders, educational outreach visits and patient‐mediated interventions. In the context of SDM it is possible to identify three overarching categories of implementation intervention: 1) interventions targeting patients, 2) interventions targeting healthcare professionals, and 3) interventions targeting both.

How the intervention might work

Theoretical and empirical evidence about behavior change in healthcare professionals (Godin 2008) and complex behavior change frameworks (Michie 2009) allow us to make certain hypotheses regarding the mechanisms by which interventions might promote SDM. For example, the distribution of printed educational materials may improve professionals' attitudes to SDM by reinforcing their intention to engage in SDM (Giguère 2012). The training of professionals in SDM through educational meetings may increase professionals' perceptions of self‐efficacy, or their belief in their ability to succeed in a situation, which is one of the key determinants of behavior (Godin 2008). Patient‐mediated interventions could be a discussion with a nurse, a patient education program, or a decision aid, for example. Decision aids are tools (they can be pamphlets or online modules) that help patients become involved in decision making. They help patients clarify the decision that needs to be made, and give information about options and outcomes. They also invite patients to articulate their personal values and preferences regarding the options (Stacey 2017). In turn, the habits of healthcare professionals may change when patients themselves take the initiative to engage more in the decision‐making process, as this may increase health professionals’ knowledge and use of emerging evidence in their area of expertise (Brouwers 2010).

Regarding the association between SDM and patient outcomes, some authors have shown that communication between healthcare professionals and patients, including SDM, can lead to improved health outcomes in direct but also in indirect ways (Street 2009). Thus, according to an adapted conceptual framework linking clinician‐patient communication to health outcomes, SDM can have an impact on affective‐cognitive outcomes (e.g. knowledge, understanding, satisfaction, trust), behavioral outcomes (treatment decisions, adherence to recommended treatments and adoption of health behaviors), as well as health outcomes (e.g. quality of life, self‐rated health and biological measures of health) (Shay 2015).

Why it is important to do this review

Policy makers perceive SDM as desirable (Shafir 2012) because: a) patient involvement is accepted as a right (Straub 2008); b) patients in general want more information about their health condition and prefer to take an active role in decisions about their health (Alston 2012; Kiesler 2006); c) SDM may reduce the overuse of options not clearly associated with benefits for all and increase the use of options clearly associated with benefits for the vast majority of the concerned population (Mulley 2012); d) SDM may reduce unwarranted healthcare practice variations (Wennberg 2004); and e) SDM may foster the sustainability of the healthcare system by increasing patient ownership of their own health care (Coulter 2006).

Nonetheless, SDM has not yet been widely implemented in clinical practice. A systematic review of 33 studies using the Observing Patient Involvement in Decision Making instrument (OPTION) showed low levels of patient‐involving behaviors (Couët 2013). The rationale for this review of interventions for increasing use of SDM among healthcare professionals is to determine what kinds of intervention have been shown to increase patient‐involving behaviors among healthcare professionals.

This is the second update of a previously published Cochrane review. The review was first undertaken in 2010 (Légaré 2010) and updated in 2014 (Légaré 2014). As the demand for SDM training programs for healthcare professionals is increasing internationally (Diouf 2016), we considered a second update was important to keep abreast of developments.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of interventions for increasing the use of SDM by healthcare professionals. We considered interventions targeting patients, interventions targeting healthcare professionals, and interventions targeting both and compared them with usual care or other type of interventions by target group.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

This review considered:

randomized trials;

non‐randomized trials;

controlled before‐after studies (CBAs); and

interrupted time series (ITS) analyses.

To be included as a CBA, the Cochrane EPOC group (Effective Practice and Organisation of Care) requires the study to have a minimum of two intervention sites and two control sites. For ITS studies, there needs to be a clearly defined point in time when the intervention occurred and at least three data points before and three after the intervention (EPOC 2017).

Types of participants

Participants could be any healthcare professional (e.g. physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers), including professionals in training (for example, medical residents). We defined professionals as being licensed or registered to practice or, in the case of physicians in training, as having completed their basic pre‐licensure education. Participants could also be patients, including healthcare consumers and simulated patients. However, studies that included simulated patients were deemed eligible only if the outcome was observer‐reported.

Types of interventions

We included studies that evaluated an intervention designed to increase the use of SDM. Interventions were organized into three target categories using the EPOC taxonomy of interventions (EPOC 2015):

interventions targeting patients (for example, patient‐mediated interventions);

interventions targeting healthcare professionals (for example, distribution of printed educational material, educational meetings, audit and feedback, reminders and educational outreach visits);

interventions targeting both patients and healthcare professionals (for example, a patient‐mediated intervention combined with an intervention targeting healthcare professionals).

Patient decision aids were considered a patient‐mediated intervention since one of their purposes is to foster patient participation in decisions during the clinical encounter (Stacey 2017). Studies that evaluated patient‐mediated interventions (for example, patients' use of patient decision aids in preparation for or during their consultation with a healthcare professional) were considered only if these studies directly assessed the healthcare professional‐related outcome of interest, that is their use of SDM (see Types of outcome measures).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Use of SDM, using objective observer‐based outcome measures (OBOMs) or patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs). OBOMs are instruments used by a third observer to capture the decision‐making process during an encounter between a healthcare professional and a patient/family caregiver when facing health treatment or screening decisions. They are only used in the reporting of observable concepts (e.g. signs or behaviors). Unlike clinician‐reported outcome measures, OBOMs are reported by people (e.g. teachers or caregivers) who do not have professional training relevant to the measurement being made (Velentgas 2013). PROMs are instruments that collect information directly from patients. The measurement is recorded without amendment or interpretation by a clinician or other observer. The measurement can be recorded by the patient directly, or recorded by an interviewer, provided that the interviewer records the patient's response exactly (Velentgas 2013).

Secondary outcomes

Patient outcomes

Affective‐cognitive outcomes

Knowledge

Satisfaction (satisfaction with care, with the choice, with the decision‐making process, with the intervention, helpfulness of the intervention)

Decisional conflict

Decision regret

Patient‐clinician communication

Self‐efficacy

Empowerment

Behavioral outcomes

Match between preferred and actual level of participation in decision making

Match between preferred option and decision made

Adherence to decision made

Health outcomes

Health status (generic instrument types)

Health‐related quality of life (generic instrument types)

Anxiety

Depression

Stress

Distress

Process outcomes

Consultation length

Costs

Equity

Adverse effects (potential harms of interventions)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched for studies published up to 15 June 2017. Searches were not restricted by language. The following electronic databases were searched for primary studies.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 5) in the Cochrane Library

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA; 2016, Issue 4) in the Cochrane Library

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED; 2015, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library

PubMed

Embase Ovid (1974 to 14 June 2017)

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1980 to 15 June 2017)

PsycINFO Ovid (1967 to June Week 1 2017)

All search strategies used are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

Trial registries

We searched:

ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Institutes of Health (NIH) at http://clinicaltrials.gov/ (search performed in week 1, August 2017);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/ (search performed in week 1, August 2017).

We also:

handsearched the proceedings of the International Conference on Shared Decision Making (from 2003 to 2017)(Appendix 2);

handsearched the proceedings of the annual North American meetings of the Society for Medical Decision Making (from 2004 to 2016) (Appendix 3); we intended to search the European Association for Communication in Healthcare (EACH) but were unable to obtain detailed information either online or in paper form);

reviewed reference lists of all included studies, relevant systematic reviews (Appendix 4) and primary studies (Appendix 5); and

contacted authors of relevant studies or reviews to clarify reported published information and to seek unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

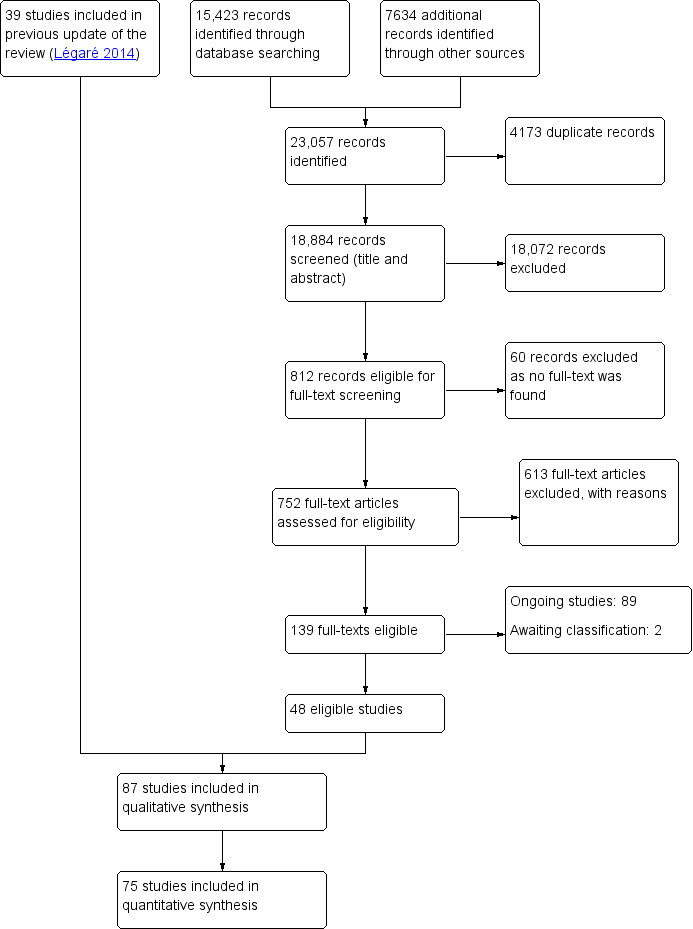

Review author Rhéda Adekpedjou (RA), and graduate students Jessica Hébert (JH), Élodie Chenard (EC), Alexandrie Boucher (AB), Lionel Adisso (LA) ‐ (see Acknowledgements) independently screened each title and abstract to find studies that met the inclusion criteria. Studies were only selected if published in English or French. We retrieved full‐text copies of all studies that might be relevant or for which the inclusion criteria were not clear in the title or abstract. In this update, when more than one publication described the same study but each presented new and complementary data, we included them all. Any disagreements about selection were resolved by discussion with two review authors (ST, FL). For more details about study selection, see Figure 1.

1.

Flow diagram of Cochrane update on interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals (up to 15 June 2017)

Data extraction and management

To extract data, we designed a form derived from the EPOC Review Group data collection checklist (EPOC 2017b). At least two review authors (including RA and ST) independently extracted data from eligible studies. We reached consensus about discrepancies, and any disagreement was adjudicated by discussion among the review authors (FL, RA, DS, ST, JK, IDG, AL, MCP, RT, GE, NDB). We entered data into Review Manager Software (RevMan 5) and checked for accuracy. When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact the study authors of to ask them to provide further details.

In addition to EPOC's standardized data collection checklist, we extracted the following characteristics of the settings and interventions.

Level of care: primary or specialized care (as defined by the type of provider).

Setting of care: ambulatory or non‐ambulatory care (e.g. hospitalized patients in acute‐care or long‐term care facilities).

Conceptual or theoretical underpinnings of the intervention (i.e. study authors stated that the intervention was based on a theory or at least referred to a theory).

Barriers assessment (i.e. study authors stated that a barriers assessment was conducted and the intervention was designed to overcome identified barriers).

Number of components included in the intervention based on the EPOC taxonomy (when a barriers assessment was mentioned it was considered a component of the intervention).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

At least two review authors (including RA and ST) independently assessed the risk of bias in each included study using the criteria outlined in the suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews (EPOC 2017c) and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) for ITS designs. For blinding, incomplete data, and baseline outcome measurement, we assessed the primary outcomes and secondary outcomes that were selected for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' table (see below for details of selection process). Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with FL. Each risk of bias criterion was assessed as 'Low risk', 'High risk' or 'Unclear'. The 10 standard criteria as suggested for all randomized trials and CBA studies are listed below.

Random sequence generation (protection against selection bias)

Concealment of allocation (protection against selection bias)

Protection against contamination.

Blinded assessment (protection against detection bias)

Baseline outcome measurement

Patient baseline characteristics

Healthcare professional baseline characteristics

Selective reporting outcome

Incomplete data outcome

Other risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We structured data analysis using statistical methods developed for EPOC by Grimshaw and colleagues (Grimshaw 2004). For each study, we reported results for categorical and continuous primary outcomes separately and in natural units. When included studies assessed SDM using an adaptation of the Control Preference Scale (Degner 1992), we dichotomized into SDM versus no SDM (Légaré 2012).

For categorical measures, we calculated the difference in risk between the intervention of interest and the control intervention. We calculated standardized mean difference (SMD) for continuous measures by dividing the mean score difference of the intervention and comparison groups in each study by the pooled estimate standard deviation for the two groups. When possible, for categorical and continuous outcomes, we constructed 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to compare groups before and after the intervention, according to the recommendations in RevMan 5. The absence of a '0' value in the CI indicated that the baselines differed or that the intervention had a positive effect compared to the control intervention or to usual care. When the baseline was different between the two groups, we used the size of the difference and its associated standard error to compare them. When there were not enough quantitative data available to make these calculations, we extracted a direct quote from the primary study on the effectiveness of the intervention and on confounding factors, if available. When no baseline was reported, we considered groups to be similar prior to the intervention.

For the analysis, we divided the studies into six comparison categories: 1) interventions targeting patients compared with usual care; 2) interventions targeting healthcare professionals compared with usual care; 3) interventions targeting both patients and healthcare professionals compared with usual care; 4) interventions targeting patients compared with other types of interventions targeting patients; 5) interventions targeting healthcare professionals compared with other types of interventions targeting healthcare professionals; 6) interventions targeting both patients and healthcare professionals compared with other types of interventions targeting both patients and healthcare professionals.

We performed a meta‐analysis if there were enough studies in each of the six comparison categories. When the study reported repeated measurements for an outcome for the same participants, only the measure closest in time to the consultation was kept in the meta‐analysis. When studies with more than two arms reported several comparisons of different outcomes or different interventions, we kept only the comparisons that most reduced the heterogeneity of the comparison group in the meta‐analysis. We considered a SMD of 0.2 as small, 0.5 as medium, and 0.8 as large (Cohen 1988).

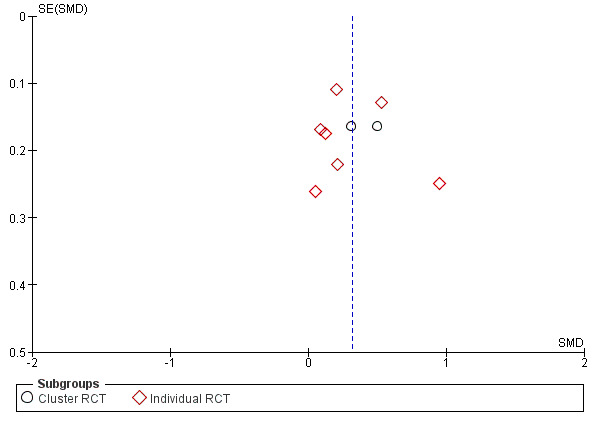

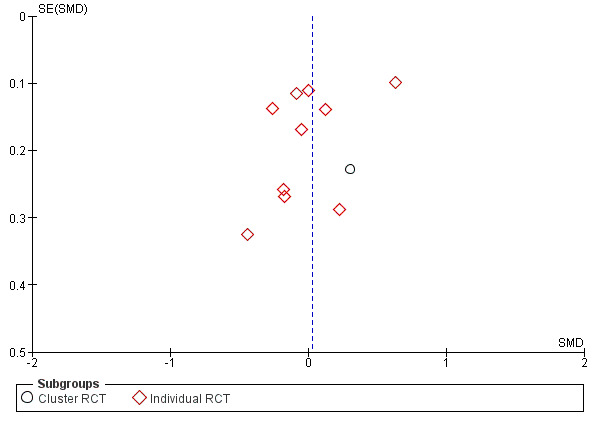

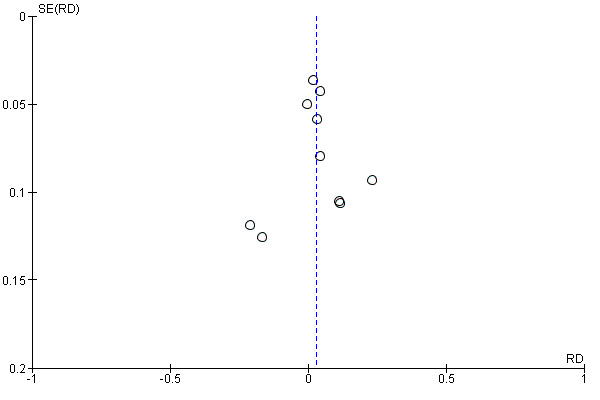

Unit of analysis issues

We included cluster‐randomized trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomized trials. Comparisons that randomize or allocate clusters (groups of healthcare professionals or organizations) but do not account for clustering during the analysis have potential unit of analysis errors that can produce artificially significant P values and overly narrow CIs (Ukoumunne 1999). Therefore, when possible, we contacted study authors for missing information and attempted to re‐analyze studies with potential unit of analysis errors. When missing information was unavailable, we reported only the point estimate.

Assessment of heterogeneity

To explore heterogeneity, we designed tables that compared SMDs of the studies and their risk differences. We considered the following variables as potential sources of heterogeneity in the results of the included studies: type of intervention; characteristics of the intervention (e.g. duration); clinical setting (primary care versus specialized care); type of healthcare professional (physicians versus other healthcare professionals); level of training of healthcare professionals (e.g. in training versus in practice).

Data synthesis

We estimated a weighted intervention effect with 95% confidence intervals. For continuous measures, we used SMDs; for dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk difference. We analyzed all data with a random‐effects model because of the diverse nature of the studies being combined and then anticipated variability in the populations and interventions of the included studies. We summarized all of the results for the primary and selected secondary outcomes and rated the strength of evidence using GRADE (Andrews 2013), and then presented these results in the 'Summary of findings' tables (Higgins 2011). As the non‐randomized evidence has a high level of uncertainty and that there are few non‐randomized trials, we reported only the results of randomized trials in the Summary of findings' tables. For studies not included in the quantitative synthesis, we assessed how their results could have impacted the pooled estimate of the effect size regarding the direction of the effect (Appendix 6).

'Summary of findings' tables

We evaluated the certainty of the evidence according to the GRADE guidelines (Guyatt 2011) and the methods described in Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011). We assessed primary and selected secondary outcomes in all six comparison categories. For each outcome, we rated conclusions as follows:

high: this research provides a very good indication of the likely effect; the likelihood that the effect will be substantially different is low;

moderate: this research provides a good indication of the likely effect; the likelihood that the effect will be substantially different is moderate;

low: this research provides some indication of the likely effect; however, the likelihood that it will be substantially different is high;

very low: this research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect; the likelihood that the effect will be substantially different is very high).

From starting score of certainty of evidence according to the study design, we downgraded the rating if one or more of the five following criteria were present: study limitation, indirect evidence, inconsistency, imprecision of the observed effect and publication bias. A review author (RA) and a graduate student (AB) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence and reached consensus in collaboration with FL.

As the use of SDM is the only primary outcome of this review, we assessed this outcome using the GRADE approach and included it in the 'Summary of findings' tables. We used the method proposed in EPOC Worksheets (EPOC 2017d) to determine which secondary outcomes should be assessed and included in the 'Summary of findings' tables. First, the study co‐authors generated a list of relevant secondary outcomes for the review. Then we independently selected outcomes important enough to be included in the 'Summary of findings' tables by rating them on a 9‐point scale ranging from 1 (not important) to 9 (critical), and came to a consensus. Then we calculated the median of the scores we had attributed to each secondary outcome and agreed to include all that scored above 7. The selected secondary outcomes were: decision regret, health‐related quality of life (mental and physical), consultation length and cost.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Analysis was pre‐defined using a subgroup analysis approach, and we did not combine data from observer‐based outcome measures (OBOMs) with patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) as they measured different concepts. In addition, within each comparison category, we explored how individually‐randomized trials compared to cluster‐randomized trials regarding our primary outcome when applicable. We further investigated heterogeneity by exploring how the study design (cluster‐randomized trials versus individually‐randomized trials) affected statistical heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

Sensitivity analysis

No sensitivity analysis were performed.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

We identified 23,057 new potentially relevant records and excluded 18,072 during abstract screening. We retrieved 752 full‐text publications for more detailed screening and excluded another 613 records based on the identified inclusion criteria. We were not able to find the full text of 60 records for assessment . We included 87 studies in the review, 48 of which were newly identified for this update (Figure 1).

Included studies

This update search added 48 new studies (Adarkwah 2016; Almario 2016; Ampe 2017; Barton 2016; Branda 2013; Causarano 2014; Cooper 2013; Cox 2017; Coylewright 2016; Davison 2002; Eggly 2017; Epstein 2017; Feng 2013; Fiks 2015; Hamann 2011; Hamann 2014; Hamann 2017; Härter 2015; Hess 2016; Jouni 2017; Kennedy 2013; Koerner 2014; Köpke 2014; Korteland 2017; LeBlanc 2015a; LeBlanc 2015b; Maclachlan 2016; Maindal 2014; Maranda 2014; Mathers 2012; Perestelo‐Perez 2016; Pickett 2012; Rise 2012; Sanders 2017; Schroy 2016; Sheridan 2012; Sheridan 2014; Smallwood 2017; Tai‐Seale 2016; Thomson 2007; Tinsel 2013; van der Krieke 2013; van Roosmalen 2004; van Tol‐Geerdink 2016; Vestala 2013; Warner 2015; Wilkes 2013; Wolderslund 2017) to the 39 original studies for a total of 87 studies.

We identified 89 ongoing studies through trial registration databases, proceedings of conferences and protocols published in electronic databases (see Characteristics of ongoing studies). For two studies, we were unable to decide whether to include them or not because not enough information was available (See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

All the studies were randomized trials except for four: three non‐randomized controlled trials (Almario 2016; Barton 2016; Deinzer 2009) and a controlled before‐after study (CBA) (Ampe 2017). Among the randomized trials, 21 were cluster‐randomized trials (Branda 2013; Cox 2017; Elwyn 2004; Epstein 2017; Feng 2013; Hamann 2007; Haskard 2008; Kennedy 2013; Koerner 2014; LeBlanc 2015a; Légaré 2012; Loh 2007; Mathers 2012; O'Cathain 2002; Perestelo‐Perez 2016; Sanders 2017; Tai‐Seale 2016; Tinsel 2013; van Roosmalen 2004; Wetzels 2005; Wilkes 2013).

Settings and participants

Of the 87 included studies, 44 evaluated interventions targeting patients, 15 evaluated interventions targeting health professionals, and 28 targeted both patients and health professionals. The four most represented countries were the USA (37 studies), Germany (15 studies) and Canada (eight studies) and the Netherlands (eight studies). There were two studies by international collaborations. The level of care was primary care in 44 studies, specialized care in 36 studies and both primary and specialized care in one study. In six studies, the level of care was unclear. In 49 studies, the healthcare professionals involved were licensed; in 16 studies they were licensed and in training; in 22 studies their level of training was unclear. The three most frequent clinical conditions studied were cancer (22 studies), cardiovascular diseases (14 studies) and psychiatric conditions (11 studies) (see Characteristics of included studies).

Target categories

Interventions targeting patients (44 studies)

Most of the 44 studies of interventions targeting patients were conducted in Europe or the USA (36 studies). There was one study from Africa. Specialized care was the most frequent care setting (22 studies), and all but eight studies were conducted in and recruited patients in an ambulatory setting. Studies varied greatly regarding the number of patients involved, ranging from 26 (Lalonde 2006) to 913 (Hess 2016). Most of the studies did not report the number of healthcare professionals involved. The most common clinical conditions were oncologic (14 studies), cardiovascular (eight studies) and psychiatric (six studies).

Interventions targeting healthcare professionals (15 studies)

The majority of the studies of interventions targeting healthcare professionals were conducted in Europe or the USA (14 studies). There was one study by an international collaboration. The care setting was mainly primary care (11 studies), with most of the participants recruited in ambulatory care (11 studies). Among the 12 studies that used non‐simulated patients, the number of patients involved ranged from 298 (Cox 2017) to 10,070 (O'Cathain 2002). Two studies did not report the number of patients involved, and three did not report the number of healthcare professionals involved. The clinical condition was different in every study.

Interventions targeting both patients and healthcare professionals (28 studies)

The majority of the 28 studies of interventions targeting both patients and healthcare professionals were conducted in Europe or the USA (27 studies). There was one study by an international collaboration. The most common care setting was primary care (16 studies), with most of the participants recruited in ambulatory care (23 studies). Among the 26 studies that used non‐simulated patients, a total of 12,078 patients were enrolled, with a minimum of 60 (Fiks 2015) and a maximum of 4349 (Wolderslund 2017). Twenty‐five studies reported participating healthcare professionals, ranging from 10 per study (Bieber 2006) to 156 per study (Haskard 2008).The most common clinical condition was cancer (seven studies), followed by cardiovascular diseases (four studies), psychiatric conditions (four studies) and type‐2 diabetes (four studies).

Characteristics of interventions and comparisons

Some studies reported more than one comparison. For such studies, we extracted only data for the comparisons that corresponded to one or more of the six comparison categories in our review. In each category of comparison, no study was counted twice for the analysis. For details, see Characteristics of included studies.

Interventions targeting patients

Twenty‐four studies compared interventions targeting patients with usual care (Almario 2016; Cooper 2011; Deen 2012; Eggly 2017; Hamann 2014; Haskard 2008; Korteland 2017; Krist 2007; Landrey 2012; LeBlanc 2015a; LeBlanc 2015b; Maclachlan 2016; Maranda 2014; Murray 2001; van Peperstraten 2010; Perestelo‐Perez 2016; Pickett 2012; Sheridan 2014; Tai‐Seale 2016; van der Krieke 2013; van Tol‐Geerdink 2016; Vestala 2013; Vodermaier 2009; Wolderslund 2017). All but one study compared patient‐mediated interventions to usual care. Patient‐mediated interventions included decision aids, patient activation, question prompt lists and training for patients. The interventions were administered alone (single interventions) or in combination (multifaceted intervention).

Twenty‐eight studies presented comparisons of interventions targeting patients with other interventions targeting patients ( Adarkwah 2016; Barton 2016; Butow 2004; Causarano 2014; Davison 1997; Davison 2002; Deen 2012; Deschamps 2004; Dolan 2002; Eggly 2017; Hamann 2011; Hamann 2017; Jouni 2017; Kasper 2008; Köpke 2014; Krist 2007; Lalonde 2006; Montori 2011; Nannenga 2009; Raynes‐Greenow 2010; Schroy 2011; Schroy 2016; Smallwood 2017; Stiggelbout 2008; Street 1995; Thomson 2007; van Roosmalen 2004; Wolderslund 2017). Of these, 18 studies compared a single intervention (these included decision aid, consultation preparation package, empowerment sessions, brochure, training of patients in shared decision making (SDM), interactive‐4‐hour education program, literacy‐appropriate medication guide) to another single intervention (these included decision aid, booklets, information packages, patient activation, pamphlets, cognitive training, 4‐hour Multiple Sclerosis specific stress management program, existing medication guide); 10 studies compared a multifaceted intervention (these included decision aid and patient activation, decision aid and literacy‐appropriate medication guide, decision aid and risk assessment tool, question prompt list and assistance of a communication coach) to a single intervention (these included decision aid, question prompt list, literacy‐appropriate medication guide, existing medication guide) and three studies compared a multifaceted intervention (these included decision aid and information booklet about immunotherapy, conventional risk and genetic risk information and decision aid) to another multifaceted intervention (these included decision aid and standard information package, conventional risk information and decision aid).

Four studies reported basing their intervention on a barriers assessment (Hamann 2011; Jouni 2017; Korteland 2017; van Peperstraten 2010).

Interventions targeting healthcare professionals

Fifteen studies compared interventions targeting the healthcare professionals with usual care ( Ampe 2017; Bernhard 2011; Cooper 2011; Cox 2017; Fossli 2011; Kennedy 2013; Koerner 2014; LeBlanc 2015b; Légaré 2012; O'Cathain 2002; Sanders 2017; Shepherd 2011; Stacey 2006; Tinsel 2013; Wilkes 2013). Of these, seven studies compared a single intervention (educational meeting, distribution of educational material, educational outreach visit, and reminder) to usual care and eight studies compared a multifaceted intervention (educational meeting and audit and feed‐back; educational meeting and distribution of educational material; educational meeting and audit and feedback and distribution of educational material; distribution of educational materials and educational meeting and audit and feedback and barriers assessment) to usual care.

Two studies compared an intervention targeting the healthcare professional (educational meeting, reminder) with one targeting the patient (decision aid, patient coaching by community health workers) (Cooper 2011; LeBlanc 2015b).

Three studies compared interventions targeting the healthcare professional with other interventions targeting the healthcare professional (Elwyn 2004; Feng 2013; Krones 2008 (ARRIBA‐Herz)). Of these, one study compared a multifaceted intervention (educational meeting and audit and feedback focusing on SDM skills) to another multifaceted intervention (educational meetings and audit and feedback focusing on risk communication skills), one study compared a single intervention (distribution of educational material) to another single intervention (distribution of educational material), and one study compared a multifaceted intervention (educational meeting, audit and feedback, distribution of educational material, and an educational outreach component) to a single intervention (educational meeting).

Four studies reported the performance of a barriers assessment and based their interventions on the identified barriers (Ampe 2017; Bernhard 2011; Murray 2010; Stacey 2006).

Interventions targeting both patients and healthcare professionals

Seventeen studies compared an intervention targeting patients and healthcare professionals with usual care (Branda 2013; Cooper 2011; Coylewright 2016; Epstein 2017; Hamann 2007; Härter 2015; Haskard 2008; Hess 2012; Hess 2016; Leighl 2011; Loh 2007; Mathers 2012; Murray 2010; Rise 2012; Tai‐Seale 2016; Wetzels 2005; Wilkes 2013). Of these, 11 studies presented interventions that used educational meetings and patient‐mediated interventions; one study presented a patient‐mediated intervention with educational outreach visits; one study presented an arm with an intervention that used a combination of a patient‐mediated intervention, distribution of educational material and educational meetings (Haskard 2008); one study presented an arm with a patient‐mediated intervention and a distribution of educational material (Wilkes 2013); one study presented an arm with a patient‐mediated intervention and a reminder; one study presented an arm with a combination of educational meeting, audit and feedback, distribution of educational material, educational outreach visit and barriers assessment; one study presented interventions that used educational meetings, patient‐mediated interventions and distribution of educational material.

Seven studies compared interventions targeting both patients and healthcare professionals with interventions targeting patients alone (Bieber 2006; Cooper 2011; Deinzer 2009; Mullan 2009; Sheridan 2012; Tai‐Seale 2016; Warner 2015). Of these, six studies compared educational meetings and patient‐mediated interventions with patient‐mediated interventions alone; one study compared interventions that used educational meetings, patient‐mediated interventions and distribution of educational material with patient‐mediated interventions alone.

Five studies compared interventions targeting both patients and healthcare professionals with interventions targeting healthcare professionals alone (Cooper 2011; Feng 2013; Fiks 2015; Maindal 2014; Roter 2012). Of these, two studies compared patient‐mediated interventions and the distribution of educational materials with the distribution of educational materials alone; two study compared educational meetings and patient‐mediated interventions with educational meetings alone; and one study compared patient‐mediated interventions and reminders with reminders alone.

Three studies compared an intervention targeting both patients and healthcare professionals with another intervention targeting both patients and healthcare professionals (Cooper 2013; Myers 2011; Tai‐Seale 2016). Of these, one study compared a multifaceted intervention including a patient‐mediated intervention, educational outreach visit, distribution of educational material and audit and feedback with another multifaceted intervention including a patient‐mediated intervention, educational outreach visit and distribution of educational material; one study compared a multifaceted intervention including a patient‐mediated intervention and reminders with another multifaceted intervention also including a patient‐mediated intervention and reminders; and one study compared a multifaceted intervention including educational meetings, patient‐mediated interventions and distribution of educational material with another multifaceted intervention including educational meetings, patient‐mediated interventions and distribution of educational material.

Three studies reported the performance of a barriers assessment and based its interventions on identified barriers (Cooper 2013; Coylewright 2016; Epstein 2017).

Conceptual framework

Thirty‐one out of the 87 studies included in this update used or referred to a conceptual framework. Six studies referred to the Ottawa Decision Support Framework (Causarano 2014; Murray 2010; Raynes‐Greenow 2010; Schroy 2011; Stacey 2006; van Peperstraten 2010); two studies referred to the RE‐AIM framework (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) (Branda 2013; LeBlanc 2015a); two studies referred to the Four Habits model (Fossli 2011; Tai‐Seale 2016); and two studies referred to the UKMRC framework (Medical Research Council guidance) (Köpke 2014; Mathers 2012). Five studies used a conceptual model but did not describe it (Bernhard 2011; Butow 2004; Hamann 2011; Hamann 2014; Loh 2007). The 14 other studies each referred to a different conceptual model, including the 4E Model (Haskard 2008); the Empowerment Model by Conger and Kanungo (Davison 1997); the LEAPS (Listen, Educate, Assess, Partner and Support) framework (Roter 2012); the Markov Model (Stiggelbout 2008); the Model of Interpersonal Interaction (Elwyn 2004); the SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) (Wetzels 2005); the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Légaré 2012); the Framework for Accountable Decision‐Making (FADM) (Maranda 2014); the Integrative Theory, Protection Motivation Theory and Self‐Determination Theory (Sheridan 2014); the WISE (Whole System Informing Self‐management Engagement) Model (Kennedy 2013); the NIH PROMIS framework (Almario 2016); the three‐step model for SDM (Ampe 2017); the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) Model (Cox 2017); and the Bandura’s social cognitive theory of self‐efficacy (Maclachlan 2016) .

Outcome measures

Primary outcome (use of shared decision making)

Of 87 studies, 59 reported patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs), 19 reported observer‐based outcome measures (OBOMs), and nine reported both OBOMs and PROMs. PROMs were used to measure patient or family caregiver’s self‐reported experiences of participating in the decision‐making process when facing health treatment or screening decisions. Among 68 studies using PROMs, 30 unique scales or subscales were used to measure the use of SDM from a patient'S perspective. In 29 studies, PROMs were the “perceived level of control in decision making” or “role assumed during the consultation” (adaptation of the Control Preference Scale (Degner 1992). Two other PROMs were the SDMQ‐9 (Kriston 2010), and the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) (Hibbard 2004; Hibbard 2005). Twenty‐seven additional unique scales or subscales were used in the studies analyzed. For more details, see Characteristics of included studies. Among the 28 studies that used OBOMs, 16 unique scales or subscales were used to measure the use of SDM from an observer‐based perspective. Study authors reporting observer‐based outcomes used the OPTION scale (Elwyn 2003) in 15 studies, and OPTION‐5 (Barr 2015) in two studies. Fourteen additional unique scales or subscales were used in the studies analyzed. For more details, see Characteristics of included studies.

Secondary outcomes

Study authors reported most on affective‐cognitive outcomes, followed by health outcomes, behavioral outcomes and process outcomes. Adverse events were seldom reported. None of the studies assessed distress or equity.

Excluded studies

After full‐text assessment of articles for eligibility, we initially excluded 613 articles. The reasons for exclusion were related to the design of the study, the type of participants, the type of outcome measure, the content of the intervention, and the language. Main reasons for exclusion of the 39 studies listed in Excluded studies are presented under Characteristics of excluded studies.

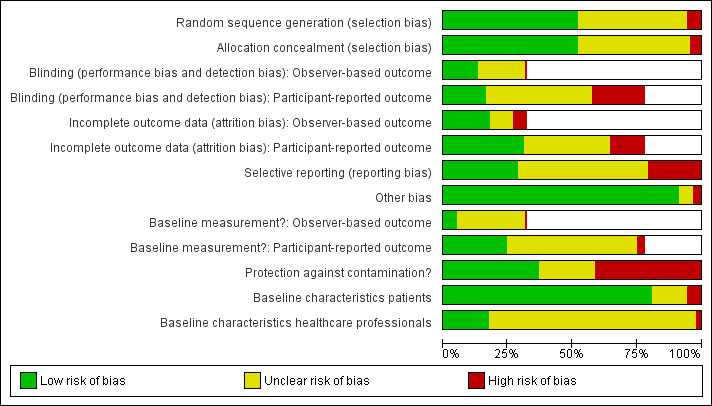

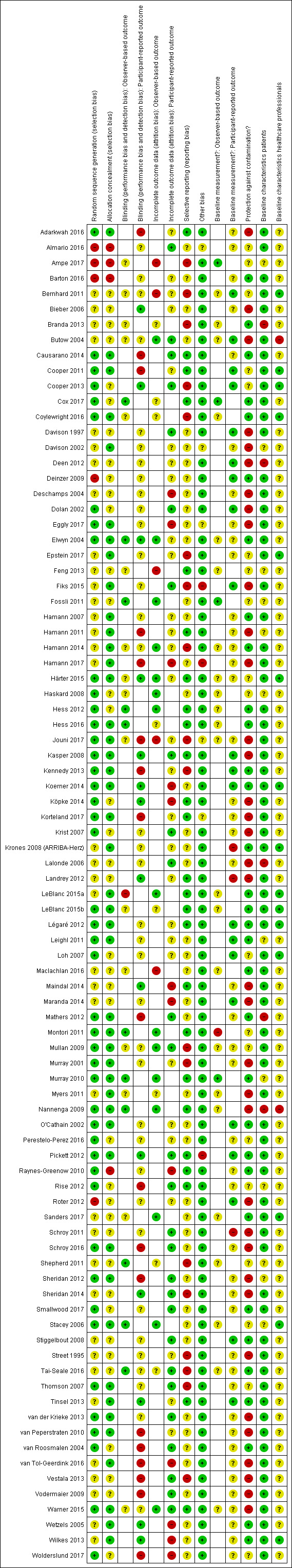

Risk of bias in included studies

Further details on the ratings and rationale for risk of bias are in the 'Risk of bias' tables in the Characteristics of included studies tables and displayed in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The 'Risk of bias' assessment reported there was based on the primary outcome only.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary for each included study.

Allocation

Allocation concealment was rated as being at low risk of bias in 44 of 87 studies (51%), unclear risk of bias in 38 studies (44%) and high risk of bias in five studies (6%) .

Blinding

For assessing risk of detection bias in the 28 studies that used observer‐based outcome measures (OBOMs), blinding was rated as being at low risk of bias in 11 studies (39%), unclear risk in 16 studies (57%) and high risk in one study (4%). In the 68 studies that used patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs), blinding was rated as being at low risk of bias in 14 studies (21%), unclear risk in 36 studies (53%) and high risk in 18 studies (26%).

Incomplete outcome data

Of the 28 studies that used OBOMs, incomplete outcome data were rated as being at low risk of bias in 15 studies (53%), unclear risk in eight studies (29%) and high risk in five studies (18%). Of the 68 studies that used PROMs, incomplete outcome data were rated as being at low risk of bias in 27 studies (40%), unclear risk in 29 studies (42%) and high risk in 12 studies (17%).

Selective reporting

For assessing risk of reporting bias, selective outcome reporting was rated as being at low risk of bias in 25 of 87 studies (29%), unclear risk in 44 studies (50%) and high risk in 18 studies (21%).

Other potential sources of bias

Among the 87 studies, in 79 studies other risks of bias were rated as low (91%), in five studies they were unclear (6%) and in three studies they were high (3%).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Interventions targeting patients compared to usual care or interventions of the same type for shared decision making.

| Interventions targeting patients compared to usual care or to interventions of the same type for shared decision making | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients, including healthcare consumers and simulated patients Settings: Australia, Canada, Germany, Namibia, Spain, Sweden, the Netherlands, UK, USA Interventions: interventions designed to improve shared decision making among healthcare professionals that target patients (for example, patient‐mediated interventions) Comparison: usual care or interventions of the same type | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Risk difference (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| [control] | [experimental] | |||||

| a‐ Intervention targeting patients compared to usual care | ||||||

| Shared decision making (observer based outcome measure (OBOM), continuous measures) (follow‐up: up to 6 months) | ‐ | SMD 0.54 higher (0.13 lower to 1.22 higher) | ‐ | 424 (4 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,b,c,d | Scales are: OPTION (0‐100) and RIAS. Higher score indicates more shared decision making use. One study was not included in the quantitative synthesis and was consistent with the pooled result |

| Shared decision making (patient reported outcome measure (PROM), continuous measures) (follow‐up: up to 3 years) | ‐ | SMD 0.32 higher (0.16 higher to 0.48 higher) | ‐ | 1386 (9 randomized) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,b,c | Scales are: Patient activation measure (0‐100), patient self‐advocacy (1‐5), COMRADE (0‐100), decision evaluation scale (1‐5), clinicians’ participatory decision making (1‐5), satisfaction with decision making process (0‐100), CollaboRATE (0‐100), patient role in treatment decision (1‐5). Higher score indicates more shared decision making use. One study was not included in the quantitative synthesis. It is unlikely that it would change the direction of the effect size estimate given that its sample size was not very large. |

| Shared decision making (PROM), dichotomous measures (follow‐up : up to 3 months) | Study population | ‐0.09 (‐0.19 to 0.01) | 754 (6 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,f | Three studies were not included in the quantitative synthesis.The first study did not support the pooled result but given that the pooled estimate of the effect size is in favor of the control group, it is likely that adding that study would move the pooled estimate of the effect size toward a null effect. The second study did not support the pooled result but given its very large sample size, it is likely that adding this study would move the pooled estimate of the effect size toward a positive effect. The third study supported the pooled result toward the null effect. | |

| 56 per 100 | 46 per 100 | |||||

| Low risk population | ||||||

| 33 per 100e | 33 per 100 | |||||

| High risk population | ||||||

| 88 per 100e | 60 per 100 | |||||

| Decision regret (follow‐up : 6 months) | ‐ | SMD 0.10 lower (0.39 lower to 0.19 higher) | ‐ | 212 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,h | Decision regret scale (0‐100). Higher score indicates more regret after decision |

| Health‐related quality of life (physical) (follow‐up: 3 months post‐operatively) | ‐ | SMD 0.00 (0.36 lower to 0.36 higher) | ‐ | 116 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW c,g,h | Physical component scale of SF‐36 (0‐100). Higher score indicate better quality of life. |

| Health‐related quality of life (mental) (follow‐up: 3 months post‐operatively) | ‐ | SMD 0.10 higher (0.26 lower to 0.46 higher) | ‐ | 116 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW c,g,h | Mental component scale of SF‐36 (0‐100). Higher score indicate better quality of life. |

| Consultation length (minutes) | ‐ | SMD 0.10 higher (0.39 lower to 0.58 higher) | ‐ | 224 (2 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW c,f,g,h | |

| Cost (£) | ‐ | SMD 0.82 higher (0.42 higher to 1.22 higher) | ‐ | 105 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,h | |

| b‐ Intervention targeting patients compared to intervention of the same type | ||||||

| Shared decision making (OBOM, continuous) (post‐visit) | ‐ | SMD 0.88 higher (0.39 higher to 1.37 higher) | ‐ | 271 (3 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW b,c,g,h | OPTION scale (0‐100). Higher score indicates more shared decision making use. Decision aid study increase the use of shared decision making compared to booklet or pamphlet |

| Shared decision making (PROM, continuous) (follow‐up: up to 6 months) | ‐ | SMD 0.03 higher (0.18 lower to 0.24 higher) | ‐ | 1906 (11 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW b,c,g,h | Scales are: Decision making subscale of the Modified Perceived involvement in care scale (4‐20), Patient Activation Measure (0‐100), 1‐item question on “who makes decisions about medical treatment” (1‐5), Satisfaction With Decision Making Process scale (12‐60), Problem‐Solving Decision‐Making Scale (1‐5), SDM‐Q9 (0‐100), patient role in treatment decision (1‐5), SDM‐Q (0‐11), Patient‐reported shared decision making (0‐4). Higher score indicates more shared decision making use. Two studies were not included in the quantitative synthesis but supported the pooled results. |

| Shared decision making (PROM, categorical or dichotomous) (follow‐up : up to 6 weeks) | Study population | 0.03 (‐0.02 to 0.08) | 2272 (10 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,f | Three studies were not included in the quantitative synthesis.Two of them were consistent with the pooled results, but the third reported an increase in the use of shared decision making for the intervention group. | |

| 38 per 100 | 40 per 100 | |||||

| Low risk population | ||||||

| 18 per 100e | 22 per 100 | |||||

| High risk population | ||||||

| 73 per 100e | 52 per 100 | |||||

| Decision regret | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| Health‐related quality of life (physical) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| Health‐related quality of life (mental) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| Consultation length (minutes) | ‐ | SMD 0.65 lower (1.29 lower to 0.00 ) | ‐ | 39 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW c,g,h | |

| Cost | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by two levels due to very serious limitations in the design (most of the studies are at high risk of bias (≥ 50%). Across studies, taking all low risk and unclear risk judgements together, there are ≥ 50% of unclear risk for our key domains) b. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by two level due to unexplained high heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 50% and P value for heterogeneity ≤ 0.05) c. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to indirectness of evidence (important difference in populations) d. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by two levels due to imprecision (insufficient number of participants for more than one study and large confidence interval) e. The low and high risk values are the two extreme percentages of events. f. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to small heterogeneity (I2 < 50% or I2 ≥ 50% and P value > 0.05) g. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to serious limitations in the design (most of the studies are at unclear risk of bias (≥ 50% of the studies are at unclear risk)) h. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to imprecision (insufficient number of participants for one study and/or large confidence interval) GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; OBOM: Observer‐based outcome measures; PROMs: Patient‐reported outcome measures; RD: Risk difference; SMD: Standardized mean difference.

Summary of findings 2. Interventions targeting healthcare professionals compared to usual care or interventions of the same type for shared decision making.

| Interventions targeting healthcare professionals compared to usual care or interventions of the same type for shared decision making | ||||||

| Patient or population: healthcare professionals responsible for patient care Settings: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, USA, UK Interventions: interventions designed to improve shared decision making among healthcare professionals that target healthcare professionals (for example, distribution of printed educational material, educational meetings, audit and feedback, reminders and educational outreach visits) Comparison: usual care or interventions of the same type | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Risk difference (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| [control] | [experimental] | |||||

| a‐ Intervention targeting healthcare professionals compared to usual care | ||||||

| Shared decision making (OBOM, continuous) (follow‐up: up to 3 months post‐intervention) | ‐ | SMD 0.70 higher (0.21 higher to 1.19 higher) | ‐ | 479 (6 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,b,c,d | Scales are: Fours Habits Coding Scheme (23‐115), OPTION (0‐100), Decision Support Analysis Tool (0‐100), Control Preference Scale (0‐4), and Family engagement (number of utterances or decision‐making events that families engaged). Higher score indicates more shared decision making use. Two studies were not included in the quantitative synthesis. The first study and one sub‐sample of the second study were consistent with the pooled result. The other sub‐sample of the second study reported no difference between the study groups. |

| Shared decision making (PROM, continuous) (follow‐up : up to 12 months) | ‐ | SMD 0.03 higher (0.15 lower to 0.20 higher) | ‐ | 5772 (5 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,b,c,d | Scales are: Physicians’ participatory decision making style (0‐4), short‐form healthcare climate questionnaire (0‐100), SDM‐Q9 (0‐100), and Overall PSA SDM perception (5‐20). Higher score indicates more shared decision making use. One study was not included in the quantitative synthesis and reported an increase in the use of shared decision making for the intervention group. |

| Shared decision making (PROM, categorical or dichotomous) (follow‐up: up to 8 weeks after delivery of pregnant women) | Study population | 0.01 (‐0.03 to 0.06) | 6303 (2 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,b,c | One study was not included in the quantitative synthesis and was consistent with the pooled results. | |

| 21 per 100 | 22 per 100 | |||||

| Low risk population | ||||||

| 19 per 100e | 17 per 100 | |||||

| High risk population | ||||||

| 36 per 100e | 45 per 100 | |||||

| Decision regret (follow‐up: 2 weeks) | ‐ | SMD 0.29 higher (0.07 higher to 0.51 higher) | ‐ | 326 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,d | Decision regret scale (0‐100). Higher score indicates more regret after decision. The slight effect observed on patient decisional regret was not clinically significant. |

| Health‐related quality of life (physical) (follow‐up: 2 weeks) | ‐ | SMD 0.16 higher (0.05 lower to 0.36 higher) | ‐ | 359 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOW a,c | Scale are : Physical scale of SF‐12 (0‐100) and SF12v2 (0‐100). Higher score indicate better quality of life. |

| Health‐related quality of life (mental) (follow‐up: 2 weeks) | ‐ | SMD 0.28 higher (0.07 to 0.49 higher) | ‐ | 359 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOW a,c | Scale are : Mental scale of SF‐12 (0‐100) and SF12v2 (0‐100). Higher score indicate better quality of life. |

| Consultation length (minutes) | ‐ | SMD 0.51 higher (0.21 higher to 0.81 higher) | ‐ | 175 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,d | |

| Cost | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| b‐ Intervention targeting healthcare professionals compared to intervention of the same type | ||||||

| Shared decision making (OBOM, continuous) (post‐visit) | ‐ | SMD 0.30 lower (1.19 lower to 0.59 higher) | ‐ | 20 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW c,f | OPTION scale (0‐100). Higher score indicates more shared decision making use.

Intervention group included: education meeting (in shared decision‐making skill) + audit and feed‐back. Control group included: educational meeting (in risk communication skills) + audit and feed‐back. One study was not included in the quantitative synthesis but reported significant positive results. |

| Shared decision making (PROM, continuous) (follow‐up: up to 4 weeks) | ‐ | SMD 0.24 higher (0.10 lower to 0.58 higher) | ‐ | 1459 (2 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,b,c,d | Scales are: COMRADE (0‐100) and SDM‐Q. Higher score indicates more shared decision making use. In one study multifaceted intervention like educational meeting, audit and feedback, educational material and educational outreach visit increase the use of shared decision making compared to educational meeting alone (control group). In the second study, no differences were found between intervention and control groups. |

| Decision regret | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| Health‐related quality of life (physical) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| Health‐related quality of life (mental) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| Consultation length | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| Cost | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to serious limitations in the design (most of the studies are at unclear risk of bias (≥ 50% of the studies are at unclear risk)) b. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by two levels due to unexplained high heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 50% and P value for heterogeneity ≤ 0.05) c. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to indirectness of evidence (important difference in populations) d. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to imprecision (insufficient number of participants for one study and/or large confidence interval)

e. The low and high risk values are the two extreme percentages of events

f. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by two levels due to imprecision (insufficient number of participants for more than one study and large confidence interval) GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; OBOM: Observer‐based outcome measures; PROMs: Patient‐reported outcome measures; RD: Risk difference; SMD: Standardized mean difference.

Summary of findings 3. Interventions targeting healthcare professionals and patients compared to usual care or interventions of the same type for shared decision making.

| Interventions targeting healthcare professionals and patients compared to usual care or interventions of the same type for shared decision making | ||||||

| Patient or population: healthcare professionals and patients Settings: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Norway, the Netherlands, UK, USA Interventions: intervention designed to improve shared decision making among healthcare professionals that target both healthcare professionals and patients (for example, a patient‐mediated intervention combined with an intervention targeting healthcare professionals) Comparison: usual care or interventions of the same type | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Risk difference (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| [control] | [experimental] | |||||

| a‐ Interventions targeting healthcare professionals and patients compared to usual care | ||||||

| Shared decision making (OBOM, continuous) (follow‐up : up to 3 months) | ‐ | SMD 1.10 higher (0.42 higher to 1.79 higher) | ‐ | 1270 (6 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,b,c,d,e | OPTION scale (0‐100). Higher score indicates more shared decision making use. |

| Shared decision making (PROM, continuous) (follow‐up: up to 6 weeks) | ‐ | SMD 0.13 higher (0.02 lower to 0.28 higher) | ‐ | 1479 (7 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,f | Scales are: Physicians’ participatory decision making style (0‐4), SDM‐Q9 (0‐100), COMRADE (0‐100), Patient activation measure (0‐100), Overall PSA SDM perception (5‐20), CollaboRATE (0‐100), Healthcare Climate Questionnaire (0‐100). Higher score indicates more shared decision making use. Two studies were not included in the quantitative synthesis. One study reported an increase in the use of shared decision making for the intervention group and the second study did not report any differences between the study groups. |

| Shared decision making (PROM, categorical or dichotomous) (post‐visit) | Study population | ‐0.01 (‐0.20 to 0.19) | 266 (2 randomized trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,d,f | One study was not included in the quantitative synthesis and the results were consistent with the pooled results. | |

| 41 per 100 | 36 per 100 | |||||

| Low risk population | ||||||

| 36 per 100g | 27 per 100 | |||||

| High risk population | ||||||

| 48 per 100g | 58 per 100 | |||||

| Decision regret (follow‐up : 3 months) | ‐ | SMD 0.13 higher (0.08 lower to 0.33 higher) | ‐ | 369 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOW a,c | Decision regret scale (0‐100). Higher score indicates more regret after decision |

| Health‐related quality of life (physical) (follow‐up: 6 weeks) | ‐ | SMD 0.08 higher (0.37 lower to 0.54 higher) | ‐ | 75 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,d | Scale are : Physical scale of SF‐12 (0‐100) and SF12v2 (0‐100). Higher score indicate better quality of life. |

| Health‐related quality of life (mental) (follow‐up: 6 weeks) | ‐ | SMD 0.01 higher (0.44 lower to 0.46 higher) | ‐ | 75 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,d | Scale are : Mental scale of SF‐12 (0‐100) and SF12v2 (0‐100). Higher score indicate better quality of life. |

| Consultation length (minutes) | ‐ | SMD 3.72 higher (3.44 higher to 4.01 higher) | ‐ | 536 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,d | |

| Cost | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| b‐ Interventions targeting healthcare professionals and patients compared to intervention of the same type | ||||||

| Shared decision making (OBOM, continuous) (post‐visit) | ‐ | SMD 0.29 lower (1.17 lower to 0.6 higher) | ‐ | 20 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,d | OPTION scale (0‐100). Higher score indicates more shared decision making use. |

| Shared decision making (OBOM, categorical or dichotomous) (post‐visit) | Study population | ‐0.04 (‐0.13 to 0.04) | 134 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW c,d,h | ||

| 8 per 100 | 4 per 100 | |||||

| Low risk population | ||||||

| N/A | N/A | |||||

| High risk population | ||||||

| N/A | N/A | |||||

| Shared decision making (PROM, continuous) (post‐visit) | ‐ | SMD 0.00 (0.32 lower to 0.32 higher) | ‐ | 150 (1 randomized trial) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOW a,c,d | CollaboRATE (0‐100). Higher score indicates more shared decision making use. |

| Decision regret | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| Health‐related quality of life (physical) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| Health‐related quality of life (mental) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| Consultation length | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| Cost | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data available for this outcome |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to serious limitations in the design (most of the studies are at unclear risk of bias (≥ 50% of the studies are at unclear risk)) b. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by two levels due to unexplained high heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 50% and P value for heterogeneity ≤ 0.05) c. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to indirectness of evidence (important difference in populations) d. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to imprecision (insufficient number of participants for one study and/or large confidence interval) e. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to possible publication bias f. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by one level due to small heterogeneity (I2 < 50% or I2 ≥ 50% and P value > 0.05) g. The low and high risk values are the two extreme percentage of events h. We downgraded the certainty of evidence by two levels due to very serious limitations in the design (most of the studies are at high risk of bias (≥ 50%). Across studies, taking all low risk and unclear risk judgements together, there are ≥ 50% of unclear risk for our key domains. GRADE: Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; OBOM: Observer‐based outcome measures; PROMs: Patient‐reported outcome measures; RD: Risk difference; SMD: Standardized mean difference.

Please refer to Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Data and analyses,Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13, Table 14, Table 15, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Appendix 8, Appendix 9 and Appendix 6 for detailed results.

1. Effect of intervention on primary outcome: interventions targeting patients compared to usual care.

| Observer‐based outcome measure ‐ Continous data | Meta‐analysis | |||||||

| Study | Intervention | Control | Outcome | N | SMD | SMD (95% CI) | I2 | |

| LeBlanc 2015a | Patient‐mediated intervention (decision aid) | Usual care | OPTION | 96 | 0.93 (0.50 to 1.36) | 0.54 (‐0.13 to 1.22) | 84% | X |