Abstract

Background

There is general agreement that oxytocin given either through the intramuscular or intravenous route is effective in reducing postpartum blood loss. However, it is unclear whether the subtle differences between the mode of action of these routes have any effect on maternal and infant outcomes. This is an update of a review first published in 2012.

Objectives

To determine the comparative effectiveness and safety of oxytocin administered intramuscularly or intravenously for prophylactic management of the third stage of labour after vaginal birth.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (7 September 2017) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing intramuscular with intravenous oxytocin for prophylactic management of the third stage of labour after vaginal birth. We excluded quasi‐randomised trials.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed studies for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy. We assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

Three studies with 1306 women are included in the review and compared intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin administered just after the birth of the anterior shoulder or soon after the birth of the baby. Studies were carried out in hospital settings in Turkey and Thailand and recruited women with singleton, term pregnancies. Overall, the included studies were at moderate risk of bias: none of the studies provided clear information on allocation concealment or attempted to blind staff or women. For GRADE outcomes the quality of the evidence was very low, with downgrading due to study design limitations and imprecision of effect estimates.

Only one study reported severe postpartum haemorrhage (blood loss 1000 mL or more) and showed no clear difference between the intramuscular and intravenous oxytocin groups (risk ratio (RR) 0.11, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.01 to 2.04; 256 women; very low‐quality evidence). No woman required hysterectomy in either group in one study (no estimable data, very low‐quality evidence), and in another study one woman in each group received a blood transfusion (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.82; 256 women; very low‐quality evidence). Other important outcomes (maternal death, hypotension, maternal dissatisfaction with the intervention and neonatal jaundice) were not reported by any of the included studies. There were no clear differences between groups for other prespecified secondary outcomes reported (postpartum haemorrhage 500 mL or more, use of additional uterotonics, retained placenta or manual removal of the placenta).

Authors' conclusions

Very low‐quality evidence indicates no clear difference between the comparative benefits and risks of intramuscular and intravenous oxytocin when given to prevent excessive blood loss after vaginal birth. Appropriately designed randomised trials with adequate sample sizes are needed to assess whether the route of prophylactic oxytocin after vaginal birth affects maternal or infant outcomes. Such studies could be large enough to detect clinically important differences in major side effects that have been reported in observational studies and should also consider the acceptability of the intervention to mothers and providers as important outcomes.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Labor Stage, Third; Blood Transfusion; Blood Transfusion/statistics & numerical data; Injections, Intramuscular; Injections, Intravenous; Oxytocics; Oxytocics/administration & dosage; Oxytocin; Oxytocin/administration & dosage; Postpartum Hemorrhage; Postpartum Hemorrhage/epidemiology; Postpartum Hemorrhage/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Oxytocin injected into a muscle or a vein for reducing blood loss after vaginal birth

What is the issue?

We set out to look at the effectiveness, risks and side effects of oxytocin given by injection into muscle (intramuscular) compared with injection into a vein (intravenous) to prevent excessive blood loss in the third stage of labour. The third stage of labour is when the placenta separates from the mother’s uterus and is delivered following the birth of the baby.

Previous studies have shown that oxytocin given to a woman during or immediately after the birth of her baby is effective in reducing excessive bleeding after vaginal birth. There is no reliable research to show whether giving oxytocin into a muscle or vein makes any difference to the effectiveness of the oxytocin or the health of the mother and baby.

Why is this important?

Blood loss during the third stage of labour depends on how quickly the placenta separates from the uterus and how well the uterus contracts to close the blood vessels to the placenta.

Most deaths of mothers related to childbirth happen in the first 24 hours after birth, mainly caused by complications of this process resulting in excessive blood loss, also known as 'postpartum haemorrhage'. Excessive bleeding is an important cause of maternal death, particularly in low‐income countries, where pregnant women are more likely to be anaemic (have too few red blood cells in their blood).

Oxytocin injected into a vein may sometimes cause serious side effects, such as a sudden drop in blood pressure and an increase in heart rate, particularly when given rapidly in a small amount of solution (undiluted). The method involved in injecting oxytocin into a muscle takes much less time than is needed for injecting it into a vein. It is also more convenient for the provider, requires relatively less skill and thus can be given by providers with limited skills.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence on 7 September 2017 and identified three studies (together including 1306 women) comparing intramuscular versus intravenous administration of oxytocin to women during or immediately after the birth of the baby. Studies were carried out in hospitals in Turkey (two) and Thailand (one) and recruited women having only one baby, at term (not early or late). The methods that the studies used to divide women into treatment groups were not clear, and in all three included studies women and staff would have been aware of which treatment they received. This may have had an impact on results and means we cannot be confident in the evidence.

The included studies did not report several important outcomes. Only one study reported severe blood loss (a litre or more) after birth and showed that there may be little or no difference between giving intramuscular and intravenous oxytocin. None of the women in one study needed surgery to remove their uterus (womb) after either intramuscular or intravenous oxytocin, and in another study two women needed a blood transfusion, one after intramuscular oxytocin and one after intravenous oxytocin. The quality of the evidence was low or very low, so we had very little confidence in the results. The studies did not report other important outcomes, such as death of the mother, low blood pressure, mothers' dissatisfaction with intramuscular or intravenous oxytocin, and number of babies with jaundice (yellowing of the skin). We found little or no clear difference between intramuscular and intravenous oxytocin for blood loss of 500 mL or more, use of additional drugs to reduce bleeding, and the placenta either not being delivered naturally or having to be removed by doctors.

What does this mean?

The findings from the three included studies did not clearly show which method of giving oxytocin was better for the mother or baby and more research is needed to answer this question.

There was only a small number of included studies and our important outcomes did not occur very often, so there was insufficient evidence to decide whether intramuscular or intravenous oxytocin is more effective and safer for women in the third stage of labour.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Intramuscular compared to intravenous prophylactic oxytocin in the third stage of labour

| Intramuscular (IM) compared to intravenous (IV) prophylactic oxytocin in the third stage of labour | ||||||

| Patient or population: women in the third stage of labour (just after delivery of the anterior shoulder or birth of the baby and cord clamping) Setting: 2 studies both in hospital settings in Turkey Intervention: intramuscular prophylactic oxytocin in the third stage of labour Comparison: intravenous prophylactic oxytocin in the third stage of labour | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with IV prophylactic oxytocin in the third stage of labour | Risk with IM | |||||

| Severe PPH (blood loss ≥ 1000 mL) | Study population | RR 0.11 (0.01 to 2.04) | 256 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1, 2 | ||

| 31 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (0 to 64) | |||||

| Serious maternal morbidity: hysterectomy | Study population | Not estimable | 600 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1, 3 | There were no events in either group | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Blood transfusion | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.06 to 15.82) | 256 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1, 2 | 1 woman in each arm of the trial had a blood transfusion | |

| 8 per 1000 | 8 per 1000 (0 to 124) | |||||

| Maternal death | Study population | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | This outcome was not reported in either of the 2 studies included in this comparison | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Maternal major adverse effects: hypotension | Study population | ‐ | (0 study) | ‐ | This outcome was not reported in either of the 2 studies included in this comparison | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Maternal dissatisfaction with intervention | Study population | ‐ | (0 study) | ‐ | This outcome was not reported in either of the 2 studies included in this comparison | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Neonatal jaundice | Study population | ‐ | (0 study) | ‐ | This outcome was not reported in either of the 2 studies included in this comparison | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; PPH: postpartum haemorrhage; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Single study with design limitations (no blinding) contributing data (‐1). 2Wide 95% CI crossing the line of no effect, low event rate, small sample size (‐2). 3No events, small sample size (‐2).

Background

Recent estimates of global maternal mortality indicate that over 300,000 women, mostly from low‐income countries, lose their lives during pregnancy and childbirth every year (WHO 2015). Most of these deaths occur during the first 24 hours postpartum largely as a result of complications of the third stage of labour.

Description of the condition

The third stage of labour refers to the period between the birth of the baby and complete expulsion of the placenta and membranes. Blood loss during this period and immediately thereafter depends on how quickly the placenta separates from the uterine wall and how well the uterus contracts to close the vascular channels in the placenta bed. While this process is entirely physiologic and often results in moderate blood loss, in situations where the uterus fails to properly contract after childbirth (uterine atony), severe postpartum bleeding could put the mother at risk of dying. For centuries, failure of the uterus to contract and retract has been recognised as a major cause of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), and in spite of the presence of effective medical interventions, remains an important cause of maternal death (Khan 2006; Oladapo 2016). PPH accounts for nearly a quarter of all maternal death worldwide (Khan 2006; Selo‐Ojeme 2002) and most of these deaths occur in low‐income countries, where a lack of access to uterotonic drug therapies combine with a high incidence of anaemia in pregnant women to complicate the third stage of labour (Lazarus 2005).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), PPH is defined as bleeding from the genital tract in excess of 500 mL after the birth of the baby (WHO 2012). Globally, this complication occurs in approximately 6% of all births although the prevalence is disproportionately higher in low‐income countries (Carroli 2008). An evidence‐based intervention that is universally recommended to reduce the incidence of PPH is the active management of the third stage of labour (ICM‐FIGO 2003; NICE 2014; WHO 2012; WHO 2017). Active management of the third stage of labour is a set of interlocking interventions that usually include administration of a prophylactic uterotonic (preferably oxytocin) during or immediately after the birth of the baby, cord clamping and cutting, and placental delivery by controlled cord traction (WHO 2017). Compared with expectant management, active management significantly reduced the risk of PPH and severe PPH by 66%, maternal postpartum anaemia by 50%, blood transfusion by 65% and use of therapeutic uterotonics by 81% (Begley 2008). However, these benefits were achieved at the expense of an increased risk of postnatal hypertension, need for opiate analgesia and afterpains. When the individual components of active management of the third stage of labour were separately analysed, it was evident that the beneficial and adverse effects observed were due mainly to the uterotonic administered during the third stage of labour (Prendiville 2000).

Description of the intervention

Historically, the first uterotonic drugs were ergot alkaloids followed by oxytocin and finally prostaglandins. Of these three, oxytocin is the most widely used in clinical practice. Oxytocin is a 9‐amino‐acid peptide that is secreted in vivo by the posterior pituitary gland. It was first discovered in 1909 by Sir Henry Dale (Dale 1909), later synthesised in 1954 by du Vigneaud (Du Vigneaud 1954), and since then has been used for labour induction and augmentation and management of the third stage of labour. Oxytocin binds to its receptors in the smooth muscles of the uterus to cause rhythmic contractions of the upper uterine segment, more powerfully towards the end of pregnancy, during labour and immediately postpartum. It is not bound to plasma proteins and has a short circulating half‐life of about three to five minutes. Oxytocin is deactivated in the gastrointestinal tract and thus its main route of administration is parenteral. The dose used for PPH‐prophylaxis varies widely between practitioners and obstetric units, ranging from 2 IU to 10 IU (international units) for both intravenous bolus and intramuscular injections. For intravenous infusion, the usual prophylactic dose is 20 IU in 500 mL of crystalloid solution, with the dosage rate adjusted according to response (Breathnach 2006). When given by the intravenous route, oxytocin causes an almost immediate action and reaches a plateau concentration after 30 minutes whereas intramuscular administration results in a slower onset of action, taking between three and seven minutes, but produces a longer‐lasting clinical effect of up to one hour (Breathnach 2006). Its elimination from the plasma is mainly through the liver and kidneys, with less than 1% excreted unchanged in the urine.

Oxytocin is stable at temperatures up to 25° C but requires refrigeration to prolong its shelf life. This requirement constitutes a major challenge to ensuring its potency in resource‐poor settings, where prolonged storage is common and the necessary facilities are either not available or in short supply. An important limitation of oxytocin is its short half‐life, which makes repeated administration inevitable in certain situations. This limitation has led to the exploration of its long‐acting analogue, carbetocin, which produces sustained uterine contractions similar to ergometrine but without its associated side effects (Su 2012).

How the intervention might work

Effectiveness in third stage of labour

For many years, oxytocin has remained a frontline uterotonic that plays a central role in the management of the third stage of labour. Although the recommended uterotonics for active management of the third stage of labour also include ergometrine and syntometrine, oxytocin is the preferred choice because it has similar efficacy but fewer side effects compared with other conventional uterotonics (ICM‐FIGO 2003; NICE 2014; WHO 2012). Even in the absence of active management of the third stage of labour, oxytocin alone reduces the incidence of PPH and has been recommended in preference to other uterotonics for PPH‐prophylaxis (WHO 2012). One limitation to its universal use for all women giving birth is that it requires parenteral administration and is thus restricted to settings where sterile equipment and providers skilled in injection practices and safety are available. A Cochrane Review comparing prophylactic oxytocin with no uterotonics, within the context of both active and expectant management of third stage of labour, found that both intramuscular and intravenous routes were effective in terms of reducing PPH and the need for therapeutic uterotonics, but lacked sufficient information about other important outcomes and adverse effects to assess their comparative efficacy and safety (Westhoff 2013).

Since the aim of giving a prophylactic uterotonic is to hasten placental separation by stimulating uterine contractions soon after birth, it can be reasonably assumed that the sooner the onset of action of a uterotonic, the faster the placenta separates and the smaller the amount of blood loss. This assumption underlies the advice to give prophylactic uterotonic during the second stage of labour (either with crowning of the fetal head or delivery of its anterior shoulder) to allow time for prompt drug action as soon as the baby is born. While it is scientifically plausible for the intravenous route to have a comparative advantage over the intramuscular route in this regard, this theory is not supported by evidence from a Cochrane Review comparing different timing of administration of uterotonics in active management of the third stage of labour (Soltani 2010). Administration of oxytocin before and after the expulsion of the placenta did not have any significant influence on many clinically important outcomes, such as the incidence of PPH and severe PPH, retained placenta, pre‐ and postdelivery changes in haemoglobin (Hb), the need for blood transfusion, use of additional uterotonic drugs and duration of the third stage of labour (Soltani 2010). This implies that a short delay in the onset of action of a uterotonic, as expected with intramuscular oxytocin, may not alter the outcomes related to blood loss when given for prophylaxis.

Potential adverse effects

Oxytocin is a vasoactive peptide with a complex hormonal activity. Apart from the uterine smooth muscles, specific receptors of oxytocin have been described in all kinds of tissues including the myocardium (heart muscle), vessels, central nervous systems and the lactating glands. Oxytocin shares about 5% of the antidiuretic properties of vasopressin as a result of certain similarities in their structures. This antidiuretic effect is responsible for the water intoxication that results from repeated administration of oxytocin in large volumes of electrolyte‐free solutions. Depending on the degree of water overload, a woman could present with headaches, vomiting, drowsiness, confusion, lethargy, convulsions or coma (In 2011). It also has a direct relaxing effect on vascular smooth muscle leading to a decreased systemic vascular resistance, hypotension and tachycardia (rapid heart beat). These haemodynamic responses were mainly associated with the intravenous route of administration particularly when given by rapid bolus injection, and often in women under anaesthesia for caesarean delivery or other pregnancy‐related indications (Hendricks 1970; Langesaeter 2009; Pinder 2002; Secher 1978; Spence 2002; Thomas 2007; Weis 1975). Oxytocin administered as an intravenous bolus of 10 IU was reported to induce chest pain, transient profound tachycardia, hypotension and ECG changes suggestive of myocardial ischaemia (Charbit 2004; Svanström 2008). In the report, Confidential enquiries into maternal deaths, 1997‐1999 (Cooper 2002), the death of two mothers with cardiovascular instability was related to cardiac arrest following intravenous injection of 10 IU of oxytocin. This finding subsequently reinforced the recommendation of 5 IU of oxytocin for the third stage of labour, to be administered slowly or by controlled intravenous infusion and since then has changed the practice in the UK (Bolton 2003). There are also reports to suggest that even low‐dose oxytocin is not haemodynamically inert as a bolus injection of 5 IU, and has the potential to cause a marked but short‐lived hypotension and tachycardia (Thomas 2007). These concerns have led to a call for caution in using intravenous oxytocin in women with unstable cardiovascular conditions, such as hypovolaemia, shock or cardiac disease.

Unlike intravenous oxytocin, there is a paucity of data regarding the side effects of intramuscular oxytocin probably because there are few of clinical importance. However, the usual side effects of any intramuscular injection such as pain at injection site and injection abscess where safety procedures are not followed are to be expected. The relative safety of intramuscular oxytocin, as perceived by stakeholders, is evident in the recommendations regarding prophylactic oxytocin by the International Confederation of Midwives and International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (ICM‐FIGO 2003), National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE 2014) and WHO (WHO 2012; WHO 2017), which are all in favour of the intramuscular route of administration.

Why it is important to do this review

While the efficacy of parenteral oxytocin in the prophylactic management of the third stage of labour is not being contested, there seems to be a general preference for the intramuscular route. Obstetric texts advocate the use of oxytocin, either intramuscularly or by dilute intravenous infusion, and warn against the use of intravenous bolus oxytocin, for fears of maternal haemodynamic consequences. Yet this safety concern was not based on rigorous scientific evidence but mainly derived from isolated cases and contexts that are not applicable to the majority of women undergoing low‐risk vaginal birth (Hendricks 1970; Langesaeter 2009; Pinder 2002; Secher 1978; Spence 2002; Thomas 2007; Weis 1975). Davies and colleagues demonstrated that a bolus oxytocin injection of 10 IU was more effective than a dilute oxytocin infusion and not associated with adverse haemodynamic responses when used for PPH‐prophylaxis in women undergoing vaginal birth (Davies 2005). On this basis, giving intramuscular oxytocin to women with established intravenous access during vaginal birth for PPH prevention may be violating the principles of best clinical practice.

Apart from the safety issues, the preference for intramuscular oxytocin might have been encouraged by its implication on the scale‐up of programmes for active management of the third stage of labour. Intramuscular injection is quicker to administer, more convenient for the provider, requires relatively less skill and thus can be given by lower‐level providers. Oxytocin administration through the pre‐filled Uniject device by lay health workers in primary health care and home birth settings is being promoted worldwide to scale up oxytocin use in places where skilled professionals are few or non‐existent (Strand 2005; Tsu 2003). This device ensures accurate dosage and safe injection practices and has been shown to be generally acceptable to both providers and mothers (Tsu 2003; Tsu 2009).

In this era of evidence‐based practice and women‐centred care, there are increasing efforts to move the recommended interventions for uncomplicated third stage of labour away from considerations of only effectiveness and also to include associated risks and adverse effects. As the issue of informed consent regarding routine interventions for the third stage of labour begins to gain ground (Begley 2008), practitioners would require concrete evidence on the trade‐off between effectiveness and adverse effects of the two routes of oxytocin administration for mothers to make an informed choice. It is therefore important to assess whether the subtle differences in the pharmacokinetics of these routes have any implications on maternal outcomes (related to vaginal blood loss, adverse effects and other PPH‐related morbidity and mortality) and infant outcomes. In view of the potential implications of such clarifications on programmatic efforts to scale up active management of the third stage of labour, it is imperative to systematically review evidence regarding the optimal route of administration of oxytocin in women undergoing low‐risk vaginal birth.

This is an update of a review first published in 2012 (Oladapo 2012).

Objectives

To determine the comparative effectiveness and safety of oxytocin administered intramuscularly or intravenously for prophylactic management of the third stage of labour after vaginal birth.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials comparing intramuscular with intravenous oxytocin when used for prophylactic management of the third stage of labour after vaginal birth. We excluded quasi‐randomised trials. We classified potentially eligible studies presented only as abstract as 'Studies awaiting classification' pending their full publication. Cluster‐randomised trials were eligible for inclusion, but we did not identify any in this update.

Types of participants

Pregnant women anticipating a vaginal birth, regardless of other aspects of third stage of labour management.

Types of interventions

Intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin (used alone or as part of active management of the third stage of labour) given as prophylaxis for the third stage of labour, at whatever dose, timing of administration and in whatever form (e.g. intravenous rapid or slow bolus injection or infusion). This update, as did the first review, focused only on oxytocin given during vaginal birth. Comparison of bolus oxytocin with dilute infusion during caesarean delivery will be the subject of another review and is not included here.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies whether or not they reported the following outcome measures of interest.

Primary outcomes

Severe PPH (blood loss of 1000 mL or more).

Serious maternal morbidity (organ failure, coma, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, hysterectomy, or as defined by the study authors).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

PPH (≥ 500 mL)

Estimated blood loss (mL)

Use of additional uterotonics

Blood transfusion

Third stage duration longer than 30 minutes

Retained placenta or manual removal of placenta

Maternal postpartum anaemia (Hb concentration less than 9 g/dL 24 to 48 hours postpartum, or as defined by study authors)

Maternal death

Adverse effects

Any adverse effect reported

Minor adverse effects (e.g. headache, nausea or vomiting) between delivery of baby and discharge from the labour ward

Major adverse effects (e.g. maternal hypotension as defined by study authors, any adverse effect requiring treatment)

Acceptability of intervention

Maternal dissatisfaction with intervention

Providers' dissatisfaction with intervention

Infant outcomes

Apgar score less than 7 at five minutes

Neonatal jaundice (as defined by the study authors)

Admission to special care baby unit

Not breastfeeding at hospital discharge

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (7 September 2017).

The Register is a database containing over 24,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. It represents over 30 years of searching. For full current search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth in the Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Two people screen the search results and review the full texts of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set that has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification; Ongoing studies).

In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (7 September 2017) for unpublished, planned and ongoing trial reports (See: Appendix 1 for detailed search methods).

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, see Oladapo 2012.

For this update, we used the following methods for assessing the 16 reports that the Information Specialist identified as a result of the updated search and for reassessing a report that was 'ongoing' in the previous version of the review.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author. We entered data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) software (RevMan 2014) and checked them for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

For each included study we assessed the method as being at:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study we described the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as being at:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

For each included study we described the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding was unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as being at:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

For each included study we described the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as being at:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

For each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, we described the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the study authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses that we undertook.

We assessed methods as being at:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

For each included study we described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as being at:

low risk of bias (where it was clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes were reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

For each included study we described any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to have an impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses (Sensitivity analysis).

'Summary of findings' table and assessment of evidence quality using the GRADE approach

For this update we used the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the evidence, as outlined in the GRADE handbook in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparisons (intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin in the third stage of labour).

Severe PPH (blood loss 1000 mL or more)

Severe maternal morbidity

Blood transfusion

Maternal death

Major adverse effects

Maternal dissatisfaction with intervention

Neonatal jaundice

We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (GRADEpro GDT 2015) to import data from RevMan 5 (RevMan 2014) in order to create a 'Summary of findings' table. We produced a summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we have presented results as summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Continuous data

We used the mean difference (MD) if outcomes were measured in the same way between studies. We planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine studies that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We planned to include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials; no such trials were identified for this version of the review. If we identify cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion in future updates we will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely (Deeks 2017).

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials are not a suitable design for these interventions and are not eligible for inclusion.

Other unit of analysis issues

One of the included studies included four study arms (with two intramuscular and two intravenous groups with oxytocin administered at different times); we combined the data from the relevant arms to form a single pairwise intramuscular versus intravenous comparison.

Dealing with missing data

We noted levels of attrition in the included studies. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, we will carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effects.

As far as possible, we carried out analyses for all outcomes on an intention‐to‐treat basis, that is, we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each study was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² (Higgins 2003) and Chi² statistics (Deeks 2017). We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I² was greater than 30% and either Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it (Sterne 2017).

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the RevMan 5 software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: that is, where studies were examining the same intervention, and we judged the studies’ populations and methods to be sufficiently similar.

If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between studies, or if we detected substantial statistical heterogeneity, we planned to use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across studies was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary would be treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we planned to discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between studies. If we did not consider the average treatment effect to be clinically meaningful, we did not combine studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to investigate heterogeneity by subgroup analyses (Deeks 2017). In this version of the review only three studies contributed data and for most outcomes only a single study contributed data or heterogeneity was low. In addition, separate data were not available for us to carry out planned subgroup analysis. In future updates if sufficient data are available, we plan to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Oxytocin used alone versus oxytocin used as part of active management of the third stage of labour

Oxytocin versus no oxytocin during the first stage of labour

Intravenous oxytocin bolus injection versus infusion

The following outcomes will be used in the subgroup analyses.

Severe PPH (1000 mL or more)

Serious maternal morbidity (organ failure, coma, ICU admission, hysterectomy or as defined by the study authors)

We will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available in RevMan 5 (RevMan 2014). We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of study quality for each comparison by restricting analysis to those studies rated as 'low risk of bias' for random sequence generation and allocation concealment. In this version of the review only three studies (all with design limitations) contributed data and so we did not carry out this additional analysis. In future updates if sufficient data become available to carry out sensitivity analysis we will limit analyses to the primary outcomes.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

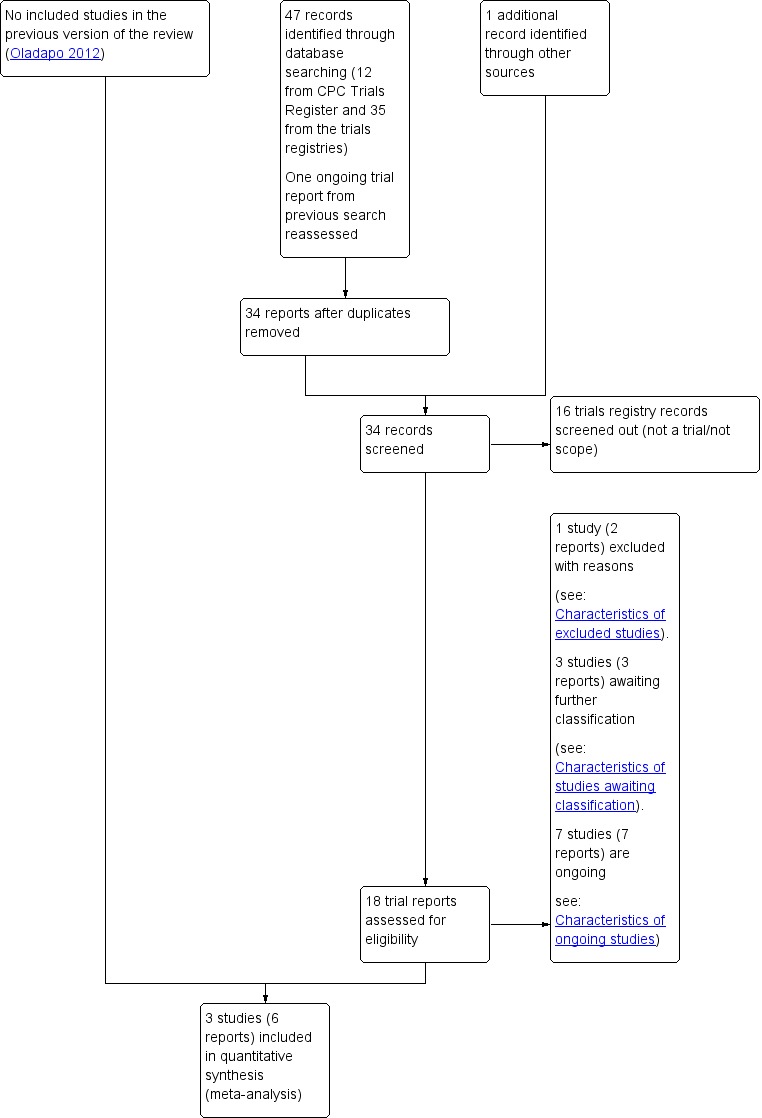

The search strategy retrieved 16 study reports for consideration in this updated review, an additional report was provided by a study author, and we also reassessed one report (Sheldon 2011) that was identified in the previous version of the review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

The 18 reports that we assessed corresponded to a total of 14 studies (four studies had two reports each). We included three studies in the review, we excluded one study, seven studies are ongoing, and the remaining three are awaiting further assessment pending more information from study authors or publication of the study report (see Figure 1). For more information on ongoing studies see Characteristics of ongoing studies, and for those awaiting classification see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Included studies

Three studies including 1306 women met the inclusion criteria (Dagdeviren 2016; Oguz 2014; Sangkhomkhamhang 2015) and contribute data to the review.

Settings

Two studies were carried out in hospital settings in Turkey (Dagdeviren 2016; Oguz 2014). Dagdeviren 2016 recruited women between February 2014 to March 2015, and Oguz 2014 from January to October 2010. Neither study reported the source of funding, however Dagdeviren 2016 and Oguz 2014 reported no conflicts of interest. One study was conducted in Thailand with recruitment between February and June 2012, but did not report its source of funding or conflicts of interest (Sangkhomkhamhang 2015).

Participants

All of the studies recruited women with singleton, term pregnancies. Dagdeviren 2016 randomised women at the point when vaginal birth was "imminent" and Oguz 2014 when women intending to give birth vaginally were in active labour. The time of randomisation was not clear in Sangkhomkhamhang 2015. Dagdeviren 2016 excluded women if the labour had been induced, and all three studies excluded women with medical or obstetric complications or complications in a previous pregnancy.

Interventions

Dagdeviren 2016 compared a group receiving intramuscular oxytocin 10 IU administered after delivery of the anterior shoulder with women receiving intravenous oxytocin 10 IU in 1000 mL saline at 1 mL/minute after delivery of the anterior shoulder.

Oguz 2014 included four arms (two intramuscular groups and two intravenous groups). In the intramuscular arms, both groups received 10 IU intramuscular oxytocin. In one group oxytocin was administered after the birth of the baby and cord clamping, while in the other, oxytocin was given at the point of delivery of the anterior shoulder. Similarly, in the intravenous arms, both groups received 10 IU intravenous oxytocin at 1 mL/minute, with administration in one group after delivery of the baby and cord clamping, and in the other at the point of delivery of the anterior shoulder. We combined the two intramuscular and intravenous groups to form a single intramuscular versus intravenous comparison. In this study none of the women received epidural or narcotics, and cord traction and late cord clamping were not applied (cord clamping was at one minute unless early intervention for the infant was needed).

Sangkhomkhamhang 2015 compared women who were given 10 IU of intramuscular oxytocin with women receiving 10 IU of oxytocin as an intravenous bolus administered over two minutes. In both groups, oxytocin was administered at the point of delivery of the anterior shoulder.

Dagdeviren 2016 and Oguz 2014 removed the placenta manually if it was not delivered within 30 minutes, and in cases of excessive bleeding massaged the uterus and administered additional uterotonics.

Excluded studies

We excluded one study (Sheldon 2011) as this was secondary analysis of data from several studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

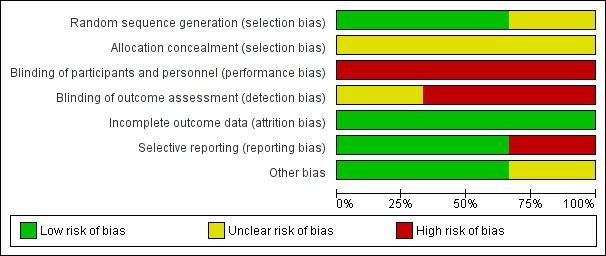

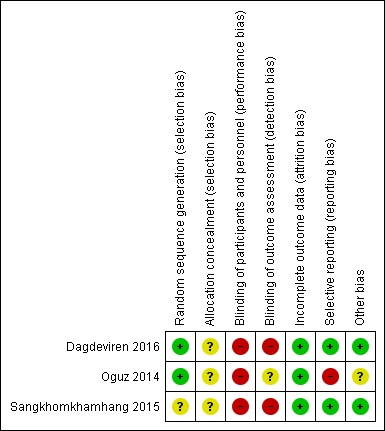

See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for a summary of our 'Risk of bias' assessments.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Dagdeviren 2016 and Oguz 2014 reported using random number tables to determine the randomisation sequence and we assessed them as low risk of bias for this domain. Sangkhomkhamhang 2015 did not describe their method for generating the randomisation sequence (unclear risk of bias). None of these studies clearly described how allocation concealment was achieved at the point of randomisation (unclear risk of bias).

Blinding

In all studies women and staff would be aware of which treatment group they were in. Lack of blinding may have affected other aspects of clinical management and we assessed all three studies as high risk of performance bias. Dagdeviren 2016 and Sangkhomkhamhang 2015 did not mention detection bias and we assessed them as high risk of bias for this domain, as lack of blinding may have had an impact on outcomes such as blood loss estimation. While Oguz 2014 reported that staff assessing blood loss outcomes were blind to group allocation, it was not clear whether or not blinding was effective.

Incomplete outcome data

None of the included studies reported any attrition or missing data (low risk of bias).

Selective reporting

The Dagdeviren 2016 study was registered and reported all expected outcomes (low risk of bias). Oguz 2014 was registered retrospectively and did not report some important outcomes. In addition, while the background sections of the paper mentioned blood loss greater than 500 mL (the usual cut‐off for PPH), the outcome reported in this study was blood loss greater than 600 mL; we assessed this study as high risk of bias for this domain. While Sangkhomkhamhang 2015 was registered and did collect data on expected outcomes, they did not fully report all outcomes, nevertheless we assessed this study as low risk of bias for this domain.

Other potential sources of bias

Other bias was not apparent in Dagdeviren 2016 and Sangkhomkhamhang 2015. Oguz 2014 had a baseline difference between groups. One group had a greater proportion of women undergoing induction of labour and this may have had an impact on outcomes (assessed as unclear).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

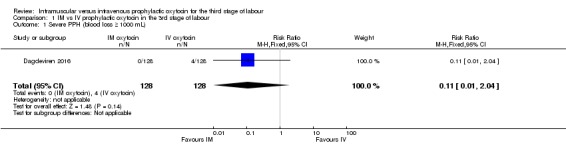

Severe PPH (blood loss 1000 mL or more)

Only one study (Dagdeviren 2016) reported this outcome and the event rate was low, with no clear difference between the intramuscular and intravenous oxytocin groups (RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.04, 256 women; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour, Outcome 1 Severe PPH (blood loss ≥ 1000 mL).

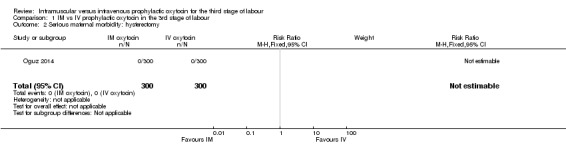

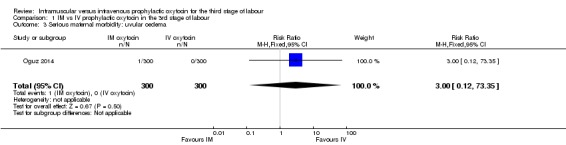

Serious maternal morbidity

Oguz 2014 reported that no women in either the intramuscular or intravenous group required hysterectomy (very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.2) and one woman in the intramuscular group suffered uvular oedema (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.12 to 73.35; 600 women; Analysis 1.3).

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour, Outcome 2 Serious maternal morbidity: hysterectomy.

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour, Outcome 3 Serious maternal morbidity: uvular oedema.

Secondary outcomes

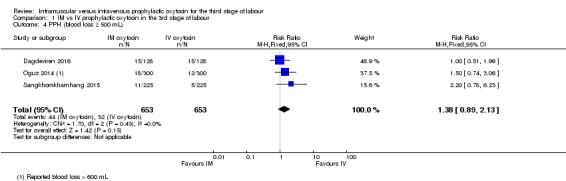

PPH (blood loss 500 mL or above)

We pooled data for this outcome although Oguz 2014 used blood loss of 600 mL or above as the cut‐off for PPH. In the intramuscular group 6.7% had PPH compared with 4.9% in the intravenous group (unweighted percentages); the CIs are wide for this outcome and show no clear difference between groups (RR 1.38, 95% CI 0.89 to 2.13; 1306 women, 3 studies; Analysis 1.4).

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour, Outcome 4 PPH (blood loss ≥ 500 mL).

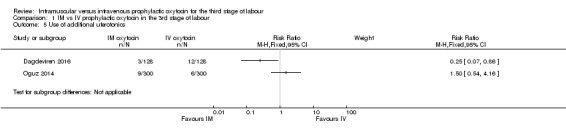

Use of additional uterotonics

Dagdeviren 2016 and Oguz 2014 reported data for this outcome, however, due to high heterogeneity and inconsistency in the direction of the treatment effect in the two studies, we decided not to pool the results. While Dagdeviren 2016 suggested less use of additional uterotonics in the intramuscular compared with the intravenous group, the direction of effect was the opposite in Oguz 2014 (Analysis 1.5).

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour, Outcome 5 Use of additional uterotonics.

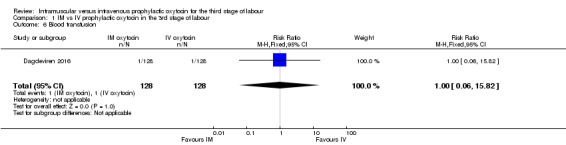

Blood transfusion

Only Dagdeviren 2016 reported the number of women requiring blood transfusion. One woman in each group received a blood transfusion (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.82; 256 women; very low‐quality evidence;Analysis 1.6).

Analysis 1.6.

Comparison 1 IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour, Outcome 6 Blood transfusion.

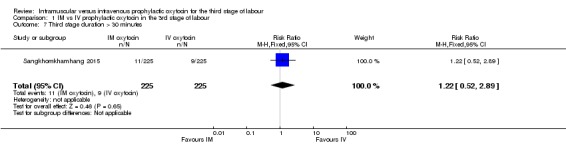

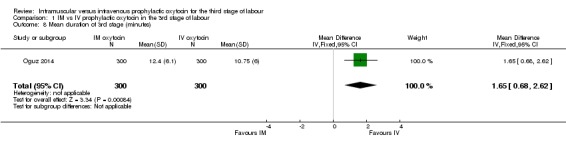

Third stage duration longer than 30 minutes

Sangkhomkhamhang 2015 reported the number of women with third stage longer than 30 minutes. There were similar numbers of women in the intramuscular and intravenous groups having a prolonged third stage (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.52 to 2.89; 450 women; Analysis 1.7). Oguz 2014 reported mean duration of third stage, and women in the intravenous group had a slightly shorter third stage (MD 1.65 minutes, 95% CI 0.68 to 2.62; 600 women; Analysis 1.8), even though the duration was less than 13 minutes in both groups.

Analysis 1.7.

Comparison 1 IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour, Outcome 7 Third stage duration > 30 minutes.

Analysis 1.8.

Comparison 1 IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour, Outcome 8 Mean duration of 3rd stage (minutes).

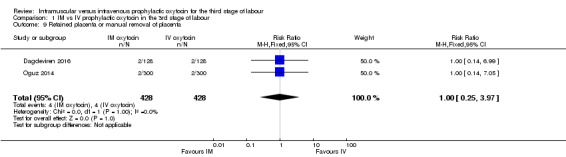

Retained placenta or manual removal of the placenta

Dagdeviren 2016 and Oguz 2014 reported this outcome. Event rates were low (0.9%) and were the same in both the intramuscular and the intravenous groups (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.25 to 3.97; 856 women; 2 studies; Analysis 1.9).

Analysis 1.9.

Comparison 1 IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour, Outcome 9 Retained placenta or manual removal of placenta.

Maternal postpartum anaemia

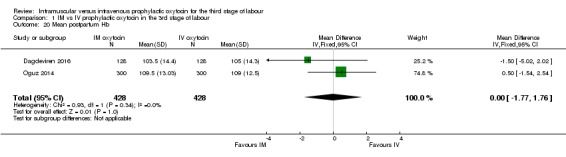

Dagdeviren 2016 and Oguz 2014 reported mean haemoglobin, and pooled results suggest that mean maternal haemoglobin following birth was almost identical for women receiving intramuscular and intravenous oxytocin (MD ‐0.00, 95% CI ‐1.77 to 1.76; Analysis 1.20).

Analysis 1.20.

Comparison 1 IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour, Outcome 20 Mean postpartum Hb.

Minor and major maternal adverse effects

None of the included studies reported either minor adverse effects, such as headache, or major adverse effects, such as hypotension.

Acceptablilty of the intervention

None of the included studies reported either maternal or provider dissatisfaction with intervention.

Infant outcomes

None of the included studies reported Apgar score less than 7 at five minutes, neonatal jaundice, admission to special care baby unit, and not breastfeeding at hospital discharge.

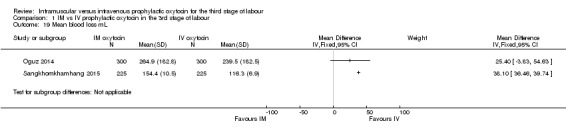

Mean blood loss (mL)

We did not pre‐specify the following outcome.

Oguz 2014 and Sangkhomkhamhang 2015 reported this outcome. Although we have displayed the data as reported, we decided not to pool results as the reported standard deviations (SDs) in the two studies varied considerably (with very low SDs in Sangkhomkhamhang 2015). While both studies suggest blood loss may have been slightly reduced in the intravenous group compared with the intramuscular group, in both studies mean loss was low and the minor difference between groups is unlikely to be clinically important. (Analysis 1.19).

Analysis 1.19.

Comparison 1 IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour, Outcome 19 Mean blood loss mL.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review we included three studies with 1306 women that compared intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin administered just after the birth of the anterior shoulder or soon after the birth of the baby. The included studies did not report many of the outcomes specified for this review. Only one study reported severe PPH (blood loss 1000 mL or above) and showed no clear difference between the intramuscular and intravenous oxytocin groups (very low‐quality evidence). In one study no women in either group required hysterectomy (very low‐quality evidence) and in another study one woman in each group received a blood transfusion (very low‐quality evidence). Other important outcomes (maternal mortality, hypotension, maternal dissatisfaction with the intervention and neonatal jaundice) were not reported by any of the included studies. For our secondary outcomes, results from one study suggested a slightly shorter mean duration of the third stage of labour. There were no clear differences between groups for other secondary outcomes reported (PPH 500 mL or above, use of additional uterotonics, retained placenta or manual removal of the placenta, or third stage duration longer than 30 minutes).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The review includes data from only three studies. The search identified a number of ongoing studies comparing intramuscular versus intravenous administration of oxytocin in the third stage of labour, and we hope to include results from these studies in the next update.

While this review set out to determine the effectiveness and safety of oxytocin administered intramuscularly or intravenously for prophylactic management of third stage of labour after vaginal birth, the small number of included studies, and very low‐quality evidence for some important outcomes makes it impossible to determine which route is better. There was a small reduction in mean blood loss in the intravenous group; however this result may be at high risk of bias and may not be of clinical importance. Ascertainment of blood loss was unlikely to have been accurate, and both of the studies contributing data were unblinded. Further, in one of the studies estimations of mean blood loss were very low in both groups (less than 155 mL). Results also suggest a slightly shorter duration of third stage by less than two minutes in the intravenous group; this has little clinical importance and would be insufficient to advocate for a change in clinical practice.

Quality of the evidence

The studies contributing data to the review were at moderate risk of bias: none of the studies provided clear information about how allocation was concealed at the point of randomisation, and all three studies were at high risk of performance bias. With this type of intervention, blinding women and staff is not simple. Both groups would have needed to receive an intramuscular or intravenous placebo; the provision of such placebos would cause additional discomfort for study participants and may be unethical. For our GRADE outcomes that the studies reported (severe PPH, hysterectomy and blood transfusion), we assessed the evidence as being of very low quality. We downgraded the evidence because of study design limitations and imprecision of the effect estimates ‐ event rates for all of these outcomes were low.

Potential biases in the review process

We minimised potential bias by the use of a comprehensive search strategy. Two review authors independently assessed eligibility and GRADE, and carried out data extraction.

The growing interest in women‐centred care has shifted evaluation of best practice beyond effectiveness alone to include adverse effects and acceptability of interventions. We examined the study reports for information on adverse events, even though the included studies provided little or no data on them.

A source of bias in this review may be the inconsistent definition of PPH in the included studies, whose pooled data indicated little difference in treatment effect, with either the intramuscular or intravenous route of administration of oxytocin. Bias in this review was, however, reduced by adherence to the review protocol and the decision not to pool individual study data on 'use of additional uterotonics' when the data showed inconsistent direction of treatment effects.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In a Cochrane Review to determine the effects of oxytocin used for the prophylactic management of the third stage of labour (Westhoff 2013), the review authors also noted that the included studies provided insufficient data to examine the role of different routes of oxytocin administration.

The number of included studies and the very low event rates for important review outcomes supports the inadequacy of data to determine whether the intramuscular or intravenous route is more effective and safer for prophylactic oxytocin administration in the third stage of labour.

Authors' conclusions

There is no reliable evidence on the comparison of intramuscular and intravenous oxytocin in terms of effectiveness and safety when used for prophylactic management of the third stage of labour after vaginal birth. This review included three studies, involving a relatively small number of participants, reporting low event rates, and studies lacked data on many of the outcomes of interest to the review. These factors make it impossible to provide reliable evidence on which route of parenteral oxytocin is better than the other in terms of effectiveness and safety when used for prophylactic management of the third stage of labour after vaginal birth.

Health practitioners who manage women should be aware of the low‐quality evidence regarding intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin in the management of third stage of labour and be guided in their choice of route by the availability of intravenous access. For women whose medical condition necessitates intrapartum intravenous access, the intravenous route may be preferred, while for women without intravenous access, intramuscular oxytocin may be more convenient for management of third stage of labour.

It is important that women are supported in their choice of the route of oxytocin administration to reduce blood loss following a low‐risk vaginal birth.

The search for eligible studies for this review update identified several completed clinical studies awaiting publication, and some ongoing clinical studies. It is hoped that by the next review update these studies will have been published. While awaiting these publications, future studies comparing intramuscular or intravenous route of oxytocin administration for the management of the third stage of labour should give importance to study design (especially allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment) in order to improve the quality of the research evidence available.

In this era of woman‐centred maternity care, future studies comparing intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin to manage third stage of labour should identify and report critical outcome measures that are important to women. Such studies should be large enough to detect clinically important differences in major side effects that have been reported in observational studies and also consider acceptability of the intervention to mothers and providers as important outcomes.

Acknowledgements

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

The World Health Organization, Babasola O Okusanya and Edgardo Abalos retain copyright and all other rights in their respective contributions to the manuscript of this review as submitted for publication.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search terms for ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP

ICTRP

intramuscular AND oxytocin AND labour

intramuscular AND oxytocin AND labor

IM AND oxytocin AND labour

IM AND oxytocin AND labor

oxytocin AND route AND labor

oxytocin AND route AND labour

ClinicalTrials.gov

Advanced search

Condition = labour OR labor

Intervention = oxytocin

Other terms = IM OR intramuscular

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

IM vs IV prophylactic oxytocin in the 3rd stage of labour

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Severe PPH (blood loss ≥ 1000 mL) | 1 | 256 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.01, 2.04] |

| 2 Serious maternal morbidity: hysterectomy | 1 | 600 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Serious maternal morbidity: uvular oedema | 1 | 600 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.12, 73.35] |

| 4 PPH (blood loss ≥ 500 mL) | 3 | 1306 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.89, 2.13] |

| 5 Use of additional uterotonics | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6 Blood transfusion | 1 | 256 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.06, 15.82] |

| 7 Third stage duration > 30 minutes | 1 | 450 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.52, 2.89] |

| 8 Mean duration of 3rd stage (minutes) | 1 | 600 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.65 [0.68, 2.62] |

| 9 Retained placenta or manual removal of placenta | 2 | 856 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.25, 3.97] |

| 10 Maternal postpartum anaemia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Minor adverse effects: headache | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12 Major adverse effects: hypotension | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13 Maternal dissatisfaction with intervention | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Providers' dissatisfaction with intervention | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15 Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16 Neonatal jaundice | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17 Admission to SCBU | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 18 Not breastfeeding at hospital discharge | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 19 Mean blood loss mL | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 20 Mean postpartum Hb | 2 | 856 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐1.77, 1.76] |

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 September 2017 | New search has been performed | Search updated and three studies identified for inclusion. In addition, we identified seven ongoing studies. |

| 13 September 2017 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | No studies were included in the previous version of the review. In this update we have included three studies examining intramuscular versus intravenous oxytocin. |

Differences between protocol and review

In the 2017 update, we added an additional search of ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

We have incorporated a 'Summary of findings' table and assessment of evidence quality using the GRADE approach into this 2017 update.

We did not pre‐specify 'mean blood loss' (mL) as an outcome in the original protocol.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT with individual randomisation | |

| Participants | Setting: teaching hospital in Istanbul, Turkey Dates of recruitment: February 2014‐March 2015 256 women randomised at the point when delivery was “imminent” Inclusion criteria: women aged 18‐45 years, singleton term pregnancy (37‐42 weeks), cephalic presentation, normal blood pressure (< 140/90 mmHg) intending to have vaginal birth Exclusion criteria: grand multiparity (although it was not clear how this was defined as parity ranged from 1‐6 in women recruited), Hb < 7 g/dL, prolonged 1st stage of labour induction (oxytocin for ≥ 12 h) previous caesarean birth or uterine surgery, uterine myoma or serious obstetric or other co‐morbidity, previous PPH, history of coagulopathies and anticoagulant treatment around the time of delivery, haemorrhage during current pregnancy, history of placental abruption, macrosomia or polyhydramnios |

|

| Interventions |

Experimental intervention: IM oxytocin 10 IU after delivery of the anterior shoulder. Total number randomised = 128 women Control/comparison intervention: IV oxytocin 10 IU in 1000 mL saline at 1 mL/min after delivery of the anterior shoulder. Total number randomised = 128 women In both groups the placenta was removed manually if it was not delivered within 30 min. If there was excessive bleeding the uterus was massaged bimanually for at least 15 s and additional uterotonics (20 IU oxytocin in 1000 mL saline solution and IM methylergometrine maleate 0.2 mg). Observations recorded every 15 min in the 1st hour and 30 min in the 2nd hour after birth. |

|

| Outcomes | Blood loss (measured by gauge in blood collection bag and weighing tampons and swabs (gauze used during episiotomy and perineal repair not included). Primary PPH (blood loss ≥ 500 mL) within 24 hours, blood loss ≥ 1000 mL, need for blood transfusion, additional uterotonics or manual removal of the placenta, duration of third stage, prolonged third stage (> 30 minutes), and side effects | |

| Notes | Funding: source of study funding not clear CoI: stated that authors have no conflicts of interest |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Reported that a random number table was used to determine the sequence for randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | The way women were allocated to groups at the point of randomisation was not clear. It was stated that women were divided into 2 “equal” groups and randomisation was at the point when delivery was imminent. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Staff providing care and making clinical decisions about interventions would be aware of which intervention women received; this may have had an impact on outcomes such as estimated blood loss and need for additional interventions. The study protocol stated that there was no attempt to mask treatment from women and personnel. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Outcomes would be recorded by staff aware of allocation and this may have had an impact on subjective outcomes such as estimates of blood loss. For outcomes such as postpartum Hb measured 24 h after the birth, the impact of lack of blinding may have been low. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The study flow diagram and tables suggest there was no loss to follow‐up. It was not clear if there were any missing data for particular outcomes. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | This was a registered study and expected outcomes were reported. Incidence of prolonged 3rd stage not reported but duration was reported as a mean. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Groups appeared similar at baseline and other bias was not apparent. It was not clear what usual practice had been in the study hospital prior to the study. |

| Methods | RCT with individual randomisation | |

| Participants | Setting: teaching hospital in Ankara, Turkey Dates of recruitment: January‐October 2010 Inclusion criteria: singleton pregnancy with cephalic presentation > 37 weeks, in active phase of labour, with normal vaginal birth Exclusion criteria: fetal death, multiple pregnancy, coagulation disorder, placental pathology, liver disease, thrombocytopenia, hypertension or taking anticoagulants, caesarean or operative birth, deep vaginal tear, chorioamnionitis, HELLP syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation before delivery |

|

| Interventions |

Experimental intervention: 2 IM groups (150 women in each). Both groups received 10 IU IM oxytocin, in group IM (A) this was given after delivery of the baby and cord clamping, in group IM (B) oxytocin was given at the point of delivery of the anterior shoulder. Total number randomised = 300 in IM group Control/comparison intervention: 2 IV groups (150 women in each) Both groups received 10 IU IM oxytocin at 1 mL/min, in group IV (A) this was given after delivery of the baby and cord clamping, in group IV (B) oxytocin was given at the point of delivery of the anterior shoulder. Total number randomised = 300 in IV group NOTE: in the data and analysis we combined the 2 IM and IV groups to form a single IM versus IV comparison. None of the women in any of the groups received epidural or narcotics. Cord traction and late cord clamping were not applied (cord clamped at 1 min unless early intervention for the infant was needed). If the placenta was not delivered after 30 min additional oxytocin (10 mU) was given (route not clear) and if no change manual removal of the placenta was performed under sedation. Women with blood loss > 500 mL also given additional oxytocin (10 mU) and if the uterus was atonic massage performed. |

|

| Outcomes | Total mean blood loss (estimated using a sterile calibrated drape) duration of 3rd stage, blood loss ≥ 600 mL postpartum haematocrit and haemoglobin. Subgroup analysis by induction | |

| Notes | Funding: source not stated CoI: reported that there was no conflict of interest |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Reported using random number table. No other information provided. There were 4 equal sized groups. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | It was not clear how allocation was concealed or at what point women were randomised. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Staff providing care and making decisions about management were not blinded and this may have had an impact on some outcomes although outcomes such as haemoglobin may not have been affected and interventions were not reported. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It was reported that staff measuring the blood‐loss outcome were blinded to treatment group although it was not clear whether other outcomes would be affected by lack of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | It appeared from the tables that there was no loss to follow‐up. It was not clear whether there were any missing data for any outcomes. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Retrospective study registration. Only a limited number of outcomes were reported. Important outcomes such as need for transfusion and severe PPH were not reported. It was not clear why the cut‐off of 600 mL was used for PPH; this is not the usual definition and the Background section talks about PPH as blood loss > 500 or 1000 mL. ClinicalTrials.gov:NCT01954186 |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | 1 of the groups had more women that had had labour induction. Other baseline characteristics were similar. |

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Setting: women attending Khon Kaen Hospital Thailand Dates of recruitment: February‐June 2012 Inclusion criteria: 450 women with singleton pregnancy attending hospital for a vaginal birth. Exclusion criteria: women with obstetric complications or medical problems. Women with a previous history of curettage, manual removal of the placenta, cardiovascular instability or oxytocin hypersensitivity |

|

| Interventions |

Experimental intervention: IM oxytocin. 10 IU oxytocin by IM injection after delivery of the anterior shoulder. Number randomised = 225 women Comparison intervention: IV oxytocin. 10 IU of oxytocin in 10 mL normal saline administered over 2 min after delivery of the anterior shoulder Number randomised = 225 women |

|

| Outcomes | Incidence of PPH (not defined) within 24 hours of the birth. Mean blood loss (measured from cord clamping until complete repair of episiotomy using plastic bags and scale) prolonged third stage, retention of the placenta for > 30 min, use of additional uterotonics, blood transfusion | |

| Notes | Funding: not reported CoI: not stated in the published report |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: “The allocation was randomly carried out by using an assignment card placed in a sealed envelope which would be picked by each sample to be assigned into one of the two treatment groups.” Comment: description unclear |