Abstract

Background

This is an updated version of the original Cochrane Review published in the Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 9. Despite good evidence for the health benefits of regular exercise for people living with or beyond cancer, understanding how to promote sustainable exercise behaviour change in sedentary cancer survivors, particularly over the long term, is not as well understood. A large majority of people living with or recovering from cancer do not meet current exercise recommendations. Hence, reviewing the evidence on how to promote and sustain exercise behaviour is important for understanding the most effective strategies to ensure benefit in the patient population and identify research gaps.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions designed to promote exercise behaviour in sedentary people living with and beyond cancer and to address the following secondary questions: Which interventions are most effective in improving aerobic fitness and skeletal muscle strength and endurance? Which interventions are most effective in improving exercise behaviour amongst patients with different cancers? Which interventions are most likely to promote long‐term (12 months or longer) exercise behaviour? What frequency of contact with exercise professionals and/or healthcare professionals is associated with increased exercise behaviour? What theoretical basis is most often associated with better behavioural outcomes? What behaviour change techniques (BCTs) are most often associated with increased exercise behaviour? What adverse effects are attributed to different exercise interventions?

Search methods

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. We updated our 2013 Cochrane systematic review by updating the searches of the following electronic databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Embase, AMED, CINAHL, PsycLIT/PsycINFO, SportDiscus and PEDro up to May 2018. We also searched the grey literature, trial registries, wrote to leading experts in the field and searched reference lists of included studies and other related recent systematic reviews.

Selection criteria

We included only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared an exercise intervention with usual care or 'waiting list' control in sedentary people over the age of 18 with a homogenous primary cancer diagnosis.

Data collection and analysis

In the update, review authors independently screened all titles and abstracts to identify studies that might meet the inclusion criteria, or that could not be safely excluded without assessment of the full text (e.g. when no abstract is available). We extracted data from all eligible papers with at least two members of the author team working independently (RT, LS and RG). We coded BCTs according to the CALO‐RE taxonomy. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias. When possible, and if appropriate, we performed a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis of study outcomes. If statistical heterogeneity was noted, a meta‐analysis was performed using a random‐effects model. For continuous outcomes (e.g. cardiorespiratory fitness), we extracted the final value, the standard deviation (SD) of the outcome of interest and the number of participants assessed at follow‐up in each treatment arm, to estimate the standardised mean difference (SMD) between treatment arms. SMD was used, as investigators used heterogeneous methods to assess individual outcomes. If a meta‐analysis was not possible or was not appropriate, we narratively synthesised studies. The quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach with the GRADE profiler.

Main results

We included 23 studies in this review, involving a total of 1372 participants (an addition of 10 studies, 724 participants from the original review); 227 full texts were screened in the update and 377 full texts were screened in the original review leaving 35 publications from a total of 23 unique studies included in the review. We planned to include all cancers, but only studies involving breast, prostate, colorectal and lung cancer met the inclusion criteria. Thirteen studies incorporated a target level of exercise that could meet current recommendations for moderate‐intensity aerobic exercise (i.e.150 minutes per week); or resistance exercise (i.e. strength training exercises at least two days per week).

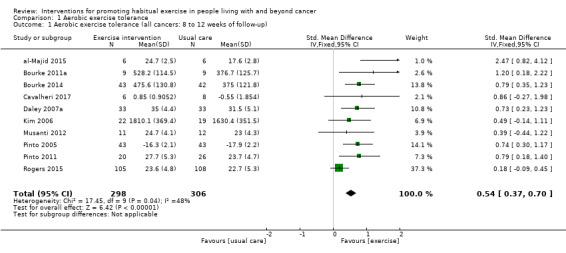

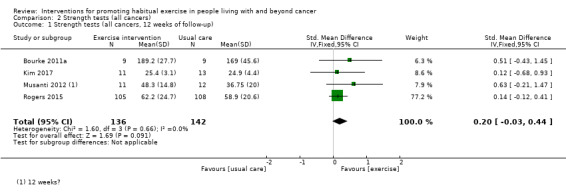

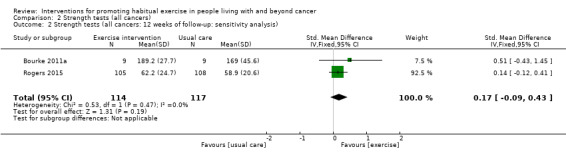

Adherence to exercise interventions, which is crucial for understanding treatment dose, is still reported inconsistently. Eight studies reported intervention adherence of 75% or greater to an exercise prescription that met current guidelines. These studies all included a component of supervision: in our analysis of BCTs we designated these studies as 'Tier 1 trials'. Six studies reported intervention adherence of 75% or greater to an aerobic exercise goal that was less than the current guideline recommendations: in our analysis of BCTs we designated these studies as 'Tier 2 trials.' A hierarchy of BCTs was developed for Tier 1 and Tier 2 trials, with programme goal setting, setting of graded tasks and instruction of how to perform behaviour being amongst the most frequent BCTs. Despite the uncertainty surrounding adherence in some of the included studies, interventions resulted in improvements in aerobic exercise tolerance at eight to 12 weeks (SMD 0.54, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.70; 604 participants, 10 studies; low‐quality evidence) versus usual care. At six months, aerobic exercise tolerance was also improved (SMD 0.56, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.72; 591 participants; 7 studies; low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Since the last version of this review, none of the new relevant studies have provided additional information to change the conclusions. We have found some improved understanding of how to encourage previously inactive cancer survivors to achieve international physical activity guidelines. Goal setting, setting of graded tasks and instruction of how to perform behaviour, feature in interventions that meet recommendations targets and report adherence of 75% or more. However, long‐term follow‐up data are still limited, and the majority of studies are in white women with breast cancer. There are still a considerable number of published studies with numerous and varied issues related to high risk of bias and poor reporting standards. Additionally, the meta‐analyses were often graded as consisting of low‐ to very low‐certainty evidence. A very small number of serious adverse effects were reported amongst the studies, providing reassurance exercise is safe for this population.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Male, Cancer Survivors, Exercise, Habits, Sedentary Behavior, Breast Neoplasms, Breast Neoplasms/rehabilitation, Colorectal Neoplasms, Colorectal Neoplasms/rehabilitation, Exercise Tolerance, Exercise Tolerance/physiology, Health Promotion, Muscle Strength, Neoplasms, Neoplasms/rehabilitation, Patient Compliance, Patient Compliance/statistics & numerical data, Prostatic Neoplasms, Prostatic Neoplasms/rehabilitation, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Time Factors

Plain language summary

Interventions for promoting habitual exercise in people living with and beyond cancer

The issue Being regularly active can bring a range of health benefits for people living with and beyond cancer, including improved quality of life and physical function. Being physically active might also reduce the risk of cancer recurrence and of dying from cancer. Because most cancer survivors are not regularly physically active, there is a need to understand how best to promote and sustain physical activity in this population.

The aim of the review To understand what are the most effective ways to improve and sustain exercise behaviour in people living with and beyond cancer.

Study characteristics We included only studies that compared an exercise intervention with a usual care comparison or 'waiting list' control. Only studies that included sedentary people over the age of 18 with the same cancer diagnosis were eligible. Participants must have been allocated to exercise or usual care at random. We searched for evidence from research databases from 1946 to May 2018.

What are the main findings? We included 23 studies involving 1372 participants in total. Evidence suggests that exercise studies that incorporate an element of supervision can help cancer survivors. However, we still have a poor understanding of how to promote exercise long term (over six months). There is some concern that research is not being reported as clearly as it should be. We found that setting goals, graded physical activity tasks and providing instructions on how to perform the exercises could help people to do beneficial amounts of exercise. In addition, we found some evidence that in people who do meet recommended exercise levels, get fitter for up to six months.

Quality of the evidence The main problems that we found regarding the quality of studies in this review included: not knowing how study investigators conducted randomisation for the trials and not knowing whether investigators who were doing trial assessments knew to which group the person they were assessing had been randomly assigned. The quality of the evidence from these studies was found to be low due to the majority of the trials often containing a low number of participants.

What are the conclusions? The main conclusions from this review are that exercise is generally safe for cancer survivors. We have a better understanding of how to encourage cancer survivors to meet current exercise recommendations. However, there is still a lack of evidence of how to encourage exercise in cancer survivors over six months.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Exercise interventions compared to usual care for promoting habitual exercise in people living with and beyond cancer to improve aerobic exercise tolerance.

| Exercise interventions compared to usual care for promoting habitual exercise in people living with and beyond cancer to improve aerobic exercise tolerance | ||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) Follow‐up | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with usual care | Risk difference with exercise interventions | |||

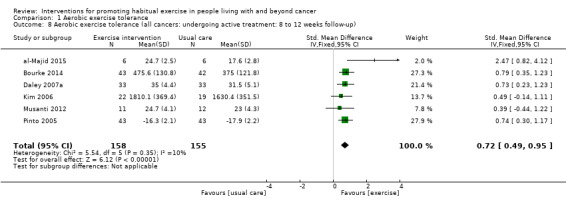

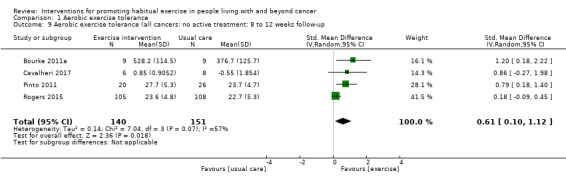

| Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: 8 to 12 weeks of follow‐up) | 604 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | The mean aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: 8 to 12 weeks of follow‐up) was 0 | SMD 0.54 higher (0.37 higher to 0.70 higher) |

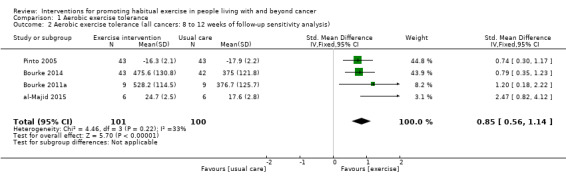

| Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: 8 to 12 weeks of follow‐up sensitivity analysis) | 201 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | The mean aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: 8 to 12 weeks of follow‐up sensitivity analysis) was 0 | SMD 0.85 higher (0.56 higher to 1.14 higher) |

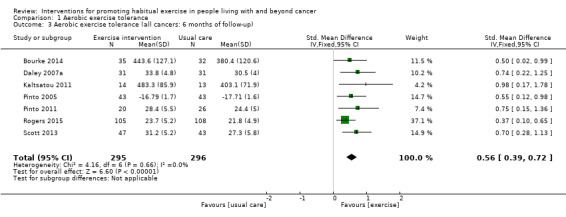

| Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: 6 months) | 591 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | The mean aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: 6 months) was 0 | SMD 0.56 higher (0.39 higher to 0.72 higher) |

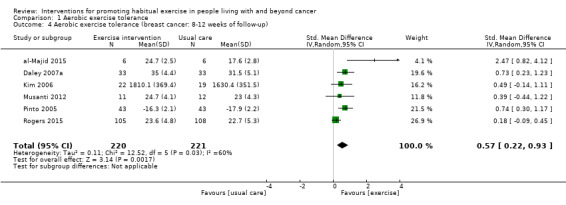

| Aerobic exercise tolerance (breast cancer: 8‐12 weeks of follow‐up) | 441 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 4 | The mean aerobic exercise tolerance (breast cancer: 8‐12 weeks of follow‐up) was 0 | SMD 0.57 higher (0.22 higher to 0.93 higher) |

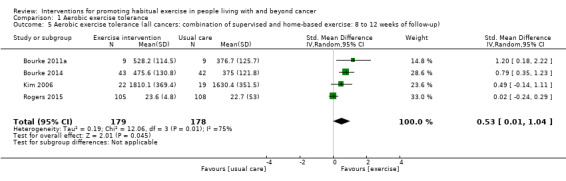

| Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: combination of supervised and home‐based exercise: 8 to 12 weeks of follow‐up) | 357 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 3 4 | The mean aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: combination of supervised and home‐based exercise: 8 to 12 weeks of follow‐up) was 0 | SMD 0.53 higher (0.01 higher to 1.04 higher) |

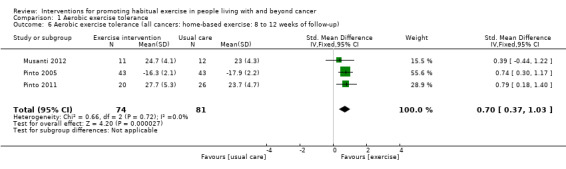

| Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: home‐based exercise: 8 to 12 weeks of follow‐up) | 155 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | The mean aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: home‐based exercise: 8 to 12 weeks of follow‐up) was 0 | SMD 0.70 higher (0.37 higher to 1.03 higher) |

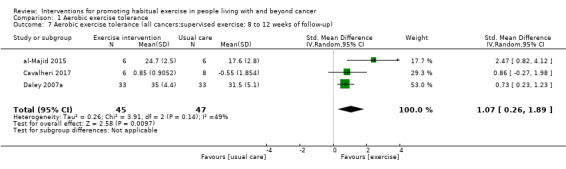

| Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers:supervised exercise: 8 to 12 weeks of follow‐up) | 92 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 2 3 5 | The mean aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers:supervised exercise: 8 to 12 weeks of follow‐up) was 0 | SMD 1.07 higher (0.26 higher to 1.89 higher) |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; SMD: standarised mean difference | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||

1 Some concerns with high number of participants lost to follow‐up, selective reporting of data and other risks of bias 2 Concerns over number of small studies included with positive results 3 Low number of participants in the studies overall and large confidence intervals 4 Some concerns over variations in effect sizes, the test for heterogeneity is significant and I2 value is high (> 50) 5 Some concerns over the variations in effect sizes.

Background

This review is an update of a previously published review in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2013, Issue 9) Bourke 2013.

Description of the condition

Cancer is a major public health issue. In 2015, there were 17.5 million cases of cancer globally, 8.7 million deaths and the disease is estimated to be responsible for 208 million disability adjusted life years (Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration 2017). Age‐standardised cancer mortality rates are decreasing (in the Western hemisphere), which is encouraging progress (Hashim 2016). However, although increasing numbers of cancer survivors live longer, this does not equate to living well. Survivors face a multitude of unique, debilitating health problems, even after treatment with curative intent. These range from an increased risk of recurrent cancers (Low 2014), persistent symptoms such as fatigue (Low 2014), ongoing poor health and well‐being (Elliott 2011), and mental health comorbidity (Nakash 2014). The burden of these problems can lead to negative impacts on health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) (Corner 2013). Throughout this review, the term we define as 'cancer survivor' is synonymous with someone 'living with and beyond cancer', in accordance with the Macmillan Cancer Support definition (Macmillan Cancer Support 2011).

Description of the intervention

The goal of any exercise intervention is to offer a sustained physiological challenge that, over time, will induce a spectrum of beneficial cardiovascular, respiratory, musculoskeletal, neurological, metabolic adaptations as well as bringing a host of psychosocial benefits. In the context of living with and beyond cancer, such adaptations underpin improvements in cancer‐related fatigue, HRQoL and physical function (Mishra 2014; Stout 2017). The UK Chief Medical Officer recommends that in adults, weekly activity should add up to at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity aerobic activity, performed in bouts of 10 minutes or longer (Department of Health 2011), with similar international recommendations for cancer survivors (Rock 2012). For example, this could translate to 30 minutes of aerobic activity that raises heart rate and breathing rate, five times per week. Alternatively, 75 minutes of vigorous intensity aerobic activity spread across the week has been suggested to confer similar benefit (Schmitz 2010a).

We have deliberately chosen the term 'habitual' over 'regular' to reflect the intention to assess which interventions could both A) improve and B) sustain exercise behaviour. 'Regular exercise' can be applied to both short‐term and long‐term contexts, where as a 'habitual' exerciser indicates a sustained and regular pattern of behaviour. Whilst 'habitual' refers to the process of behavioural 'habit forming' and an automaticity of behaviour (Gardner 2011; Verplanken 2009), we recognise there are other theoretical principals underpinning physical activity behaviour (Kwasnica 2016).

How the intervention might work

Encouraging people to participate in regular exercise from a background of an inactive lifestyle is difficult, requiring attention to important psychosocial and behavioural influences (Kampshoff 2014; Ormel 2017). A major challenge is to provide a support structure for physical activity until it becomes a pattern of sustained healthy behaviour. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in cancer survivors have assessed a number of exercise interventions, with the aim of promoting short‐ and long‐term habitual exercise. A wide range of approaches have been investigated; including supervised exercise and home‐based exercise (Bourke 2014), and inclusive of group counselling sessions, (Rogers 2015). Tailored exercise interventions commonly comprise aerobic exercise training, strength training or a combination of both, with or without behaviour change support. Behaviour change theory within exercise interventions is often viewed as essential, with the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) recommending the use of theory in intervention development for complex interventions to help improve behaviour change (Craig 2008). However, the application of behaviour change theory or specific behaviour change techniques is often generally poor, unclear and not clearly examined for impact of effectiveness.

Why it is important to do this review

The majority of people living with and beyond cancer are not regularly active, with estimates ranging from less than 10% to 20% to 30% of cancer survivors meeting the physical activity guidelines (Garcia 2014). There are a number of important beneficial effects of exercise participation in cancer survivors reported from RCTs including improved HRQoL, reduced fatigue and improved physical function, (Bourke 2014; Dittus 2017; Meneses‐Echavez 2015; Mishra 2012a; Mishra 2012b; Stout 2017). However, the original review (Bourke 2013) found that most of the current evidence comes from studies with short‐term interventions and follow‐up. Understanding which interventions are most efficacious in supporting the maintenance of long‐term exercise behaviour is critical not just because of the HRQoL benefits (Bourke 2012a), but multiple observational reports link being regularly active to reduced chances of dying from cancer after diagnosis (Li 2016).

The original review showed that there is a poor understanding of how to encourage people living with and beyond cancer to meet current exercise recommendations (Bourke 2013). Poor study reporting standards was a pervasive issue e.g. failure to report adherence data. However, there were some useful data regarding the use of behaviour change techniques (BCTs). An updated review can firstly, offer insight as to whether interventions being tested in contemporary studies are mapping to the existing international recommendations i.e. the American Cancer Society (ACS) guidance (i.e. provided by Rock 2012). Secondly, this will allow us to evaluate if there have been any improvements in the quality of intervention reporting around specifics of set prescriptions (i.e. frequency, intensity, duration etc). Thirdly, and critically, we can use a larger data set from our updated searches to assess if both the quality of reporting of exercise adherence has improved and if there is more to learn about how to promote and sustain better adherence to exercise behaviour interventions in previously inactive cancer survivors.

In the UK, the Independent Cancer Taskforce strategy document sets out a number of initiatives to achieve world class outcomes in cancer; ensuring survivors have the best possible quality of life and improving rates of mortality. Promoting habitual exercise participation could help to accomplish these high priority agendas within the UK.

Objectives

Primary objective

To assess the effects of interventions designed to promote exercise behaviour in sedentary people living with and beyond cancer.

Secondary objectives

To address the following questions.

Which interventions are most effective in improving aerobic fitness and skeletal muscle strength and endurance?

What adverse effects are attributed to different exercise interventions?

Which interventions are most effective in improving exercise behaviour amongst patients with different cancers?

Which interventions are most likely to promote long‐term (12 months or longer) exercise behaviour?

What frequency of contact with exercise professionals and/or healthcare professionals is associated with increased exercise behaviour?

What theoretical basis is most often associated with increased exercise behaviour?

What behaviour change techniques are most often associated with increased exercise behaviour?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that allocated participants or clusters of participants by a random method to an exercise‐promoting intervention compared with usual care or 'waiting list' control. We included studies conducted both during and after primary treatment or during active monitoring. Only interventions that included a component targeted at increasing aerobic exercise and/or resistance exercise behaviour were included in this review. We did not include studies of heterogeneous cancer cohorts (i.e. participants with different primary cancer sites). We did not include studies in 'at risk' populations (i.e. studies involving individuals who have risk factors for cancer but who have not yet been diagnosed with the disease) that addressed primary prevention research questions.

Types of participants

We included only studies involving adults (18 years of age or older) who had a sedentary lifestyle or physically inactive at baseline (i.e. not undertaking 30 minutes or more of exercise of at least moderate intensity, three days per week, or 90 minutes in total of moderate intensity exercise per week). Participants must have been histologically or clinically diagnosed with cancer regardless of sex, tumour site, tumour type, tumour stage and type of anticancer treatment received. We excluded studies directed specifically at end‐of‐life‐care patients and individuals who were currently hospital inpatients.

Types of interventions

For the purposes of this review, the phrases 'exercise' and 'physical activity' were used interchangeably. Definitions of exercise, related terms and nomenclature that describe the performance of exercise must adhere to principles of science and must satisfy the Système International d'Unités (SI), which was adopted universally in 1960. Hence, we referred to the appropriate, combined definition that applies to all situations: 'A potential disruption to homeostasis by muscle activity that is either exclusively or in combination, concentric, eccentric or isometric' (Winter 2009). Investigators must have reported the frequency, duration and intensity of aerobic exercise behaviour or frequency, intensity, type, sets and repetitions of resistance exercise behaviour that was prescribed in the intervention.

We acknowledge that the maximal aerobic capacity (V̇O2max)/peak is often the most informative metric for setting aerobic exercise intensity; however, given the nature of the population involved (elderly, potentially with multiple comorbidities), it is often difficult to conduct maximal testing protocols to prescribe intensity on the basis of this measures because of the requirements for medically qualified staff to be present during assessment. As such, for reasons of pragmatism, we accepted that exercise intensity is more frequently reported in cancer the cohorts in terms of age‐predicted maximum heart rate(HRmax) or Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) (Borg 1982). The interventions in this review were categorised as achieving a mild (less than 60% HRmax/10 RPE or less), moderate (60% to 84% HRmax/11 to 14 RPE) or vigorous (85% HRmax or more/15 RPE or more) exercise intensity.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Aerobic exercise behaviour as measured by:

exercise frequency (number of bouts per week);

exercise duration (total minutes of exercise achieved);

exercise intensity (e.g. % HRmax, RPE);

estimated energy expenditure from free‐living physical activity (e.g. from accelerometer readings (where available));

adherence to the exercise intervention (% of exercise sessions completed/attended); total duration of intervention when ≥75% adherence is achieved (in weeks);

total duration of sustained exercise behaviour meeting American Cancer Society guidelines for exercise in people living with and beyond cancer (Rock 2012; i.e. aim to exercise at least 150 minutes per week, with at least two days per week of strength training).

Resistance exercise behaviour as measured by:

exercise frequency (number of bouts per week);

exercise intensity (e.g. % of 1 repetition max or % of body mass);

type of exercise (e.g. free weights, body weight exercise);

repetitions;

sets.

Secondary outcomes

Change in aerobic fitness or exercise tolerance (maximal or submaximal when measured directly or by a standard field test).

Change in skeletal muscle strength and endurance.

Adverse effects.

study recruitment rate.

Intervention attrition rate.

Interventions were judged as successful in achieving exercise goals if investigators reported at least 75% adherence over a given follow‐up period as done in the original review (Bourke 2013). Data on compliance with the intervention were quantified in terms of number of prescribed exercise sessions completed as a proportion of the total set. The intervention must have included at least six weeks of follow‐up. Interventions were described according to whether they reported being based on a behaviour change theory e.g. control theory, social cognitive theory; (Bandura 2000; Bandura 2002; Carver 1982. This relates to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance for behaviour change, which recommends that clinicians should be explicit about the theoretical constructs on which interventions are based (NICE 2007). Interventions were also coded using the ‘Coventry, Aberdeen & London-Refined’ (CALO‐RE) taxonomy (Michie 2011). This is a validated taxonomy of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) that can be used to help people change their exercise behaviour. Coding interventions according to this taxonomy allows for a better understanding of which techniques are employed by current interventions and how they are related to short‐ and longer‐term exercise behaviour change.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The searches were run for the original review from inception to August 2012. The subsequent searches from the following electronic databases were run from August 2012 up to 3 May 2018. We carried out the following searches:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 5) in The Cochrane Library;

MEDLINE via OVID August 2012 to April week 4 2018;

Embase via OVID August 2012 to 2018 week 18;

AMED (Allied and Alternative Medicine Database; covers occupational therapy, physiotherapy and complementary medicine) August 2012 to May 2018;

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) August 2012 to May 2018;

PsycINFO (Database of the American Psychological Association) August 2012 to May 2018;

SportDiscus (Sports Evidence Database) August 2012 to April 2017;

PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence Database) August 2012 to April 2017.

The search strategies are presented in the Appendices, with both the 2018 updated strategy and previous 2012 strategy reported. CENTRAL search strategy is presented in Appendix 1 and the MEDLINE search strategy in Appendix 2. For databases other than MEDLINE, we adapted the search strategy accordingly: Embase (Appendix 3), AMED (Appendix 4), CINAHL (Appendix 5) PsycINFO (Appendix 6) PEDro (Appendix 7) SportsDiscus (Appendix 8).

The search strategies were developed with the Cochrane Gynaecological Cancer Group Information Specialist and included MeSH and text word terms as appropriate.

Searching other resources

We used snowballing, by searching reference lists of retrieved articles and published reviews on the topic.

We expanded the database search by identifying additional relevant studies for this review, including unpublished studies and references in the grey literature. This was done by searching the OpenGrey database (www.opengrey.eu/), which includes technical or research reports, doctoral dissertations, conference papers and other types of grey literature. We also searched the following clinical trials web pages.

World Health Organisation apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx

National cancer institute www.cancer.gov/about‐cancer/treatment/clinical‐trials/search

Furthermore, we wrote to Cancer Research UK (CRUK), Macmillan Cancer Support, the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF), Worldwide Cancer Research , the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR), the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) to enquire about relevant unpublished papers.

Data collection and analysis

Since publication of the previous version of this review, we have included the use of the GRADE assessment to assess the quality of the evidence and produced a Table 1.

Selection of studies

We imported results from each database into the reference management software package Endnote, from which we removed duplicates. After training on the first 100 references retrieved from two different databases to ensure a consistent approach, two review authors (RT and HQ) worked independently to screen all titles and abstracts to identify studies that met the inclusion criteria, or that could not be safely excluded without assessment of the full text (e.g. when no abstract was available). Disagreements were resolved by discussion with another review author (LB). Full texts were retrieved for these articles.

After training was provided to ensure a consistent approach to study assessment and data abstraction, two review authors worked independently to assess the retrieved full texts (RT and HQ). We linked together multiple publications and reports on the same study. Studies that appeared to be relevant but were excluded at this stage are listed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We resolved disagreements by discussion with other group members. We attempted to contact study corresponding authors if we could not access a full text (e.g. if only an abstract was available), if we required more information to determine whether a study could be included (e.g. to determine baseline exercise behaviour of a cohort), or if we required supplementary information about an already eligible study (please also see Excluded studies).

Data extraction and management

Review authors (RT and LB) extracted the following data using the same data extraction form used in the original review and entered data into RevMan 5.3 (Review Manager 2014).

Study details: author; year; title; journal; research question/study aim; country where the research was carried out; funding source; recruitment source (e.g. consecutive sampling from outpatient appointments; advertising in the community; convenient sample from support groups); inclusion and exclusion criteria; study design (cluster RCT, non‐cluster RCT, single centre or multi‐centre); sample size; number of participants per arm; length of follow‐up; description of usual care.

Intervention details: categorisation of intervention (e.g. supervised, independent, educational); setting (e.g. dedicated exercise facility, community, home); exercise prescription components (e.g. aerobic exercise, resistance exercise, stretching); theoretical basis, behaviour change techniques (using CALO‐RE taxonomy), frequency of contact with an exercise professional and or healthcare professional; instructions to controls.

Participant characteristics: primary cancer diagnosis; any cancer treatment currently undertaken; metastatic disease status; age; sex; body mass index (BMI); ethnicity; reported comorbidities.

Resulting exercise behaviour: method of measuring exercise (e.g. self‐report questionnaire). Numbers of participants randomly assigned and assessed at specified follow‐up points. Frequency, duration, intensity of aerobic exercise achieved; frequency, intensity, type, sets and repetitions of resistance exercise achieved; total duration of the intervention; total duration of sustained meaningful exercise behaviour as a result of the intervention and whether the Rock 2012 guidelines were met, adherence to the intervention; rate of attrition and adverse effects reported.

Resulting change in other outcomes: changes in aerobic fitness and estimated energy expenditure from free‐living physical activity.

Three members of the group worked independently (RT, RG and LS) to extract data from all eligible papers using the data collection form. Data were entered into the Cochrane's statistical software, Review Manager 2014, by one review author and checked by a second review author.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias and methodological quality were assessed in accordance with Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). The tool includes the following seven domains:

sequence generation (method of randomisation);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding (masking) of participants and personnel (detections bias);

blinding (masking) of outcome assessors (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting;

other sources of bias.

However, we did not include blinding to group allocation, as it is not possible (e.g. in a supervised exercise setting) to blind participants to an intervention while promoting exercise behaviour. Two review authors (RT and RG) independently applied the 'Risk of bias' tool, and differences were resolved by discussion with a third review author (LB). We summarised results in both a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias' summary. Results of meta‐analyses were interpreted in light of the findings with respect to risk of bias. We contacted study authors to ask for additional information or for further clarification of study methods if any doubt surrounded potential sources of bias. Individual 'Risk of bias' items can be seen in Appendix 9.

Measures of treatment effect

For the purposes of this review, all exercise behaviour was synthesised as specified in the primary outcomes. For comparison of measures of change in fitness levels or estimated energy expenditure from free‐living physical activity, please see the section on 'Continuous data' in Data synthesis.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not include any cross‐over trials in this review because of the high risk of contamination. It can be very difficult to “wash out” exercise behaviour. Cancer survivors in particular can be a highly‐motivated cohort, and significant contamination has been reported even in conventional RCT settings (Courneya 2003; Mock 2005). Hence this learning effect distorts results. Furthermore, asking individuals to revert to sedentary behaviour could be considered unethical (Das 2012). Therefore, any cross‐over trials identified were rejected at the title and abstract screening stage.

Dealing with missing data

We assessed missing data and dropout rates for each of the included studies and reported the numbers of participants included in the final analysis as a proportion of all participants included in the study. We assessed the extent to which studies conformed to an intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Consistency of results was assessed visually and through examination of the I2 statistic, a quantity that describes approximately the proportion of variation in point estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error.An I2 greater than or equal to 50% was considered significant heterogeneity. We addressed this by performing a sensitivity analysis that excluded any heterogeneous trials. We supplemented this with a test of homogeneity to determine the strength of evidence that the heterogeneity was genuine. When significant statistical heterogeneity was detected, differences in characteristics of the studies or other factors were explored as possible sources of explanation. Any differences were summarised in a narrative synthesis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Publication bias

We intended to examine funnel plots corresponding to meta‐analysis of the primary outcomes to assess the potential for small study effects such as publication bias if a sufficient number of studies (i.e. more than 10) was identified. However, this was not the case; therefore this step was not included in the analysis.

Data synthesis

Continuous data

For continuous outcomes (e.g. cardiorespiratory fitness), we extracted the final value, the standard deviation (SD) of the outcome of interest and the number of participants assessed at endpoint for each treatment arm at the end of follow‐up, to estimate standardised mean differences (SMD) between treatment arms.

Dichotomous outcomes

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. adverse effects, deaths), if it was not possible to use a hazard ratio (HR), we extracted the number of participants in each treatment arm who experienced the outcome of interest and the number of participants assessed at endpoint, to estimate a risk ratio (RR).

Meta‐analysis

When possible, and if appropriate, we performed a meta‐analysis of review outcomes. If statistical heterogeneity was noted, a meta‐analysis was performed using a random‐effects model. We planned to use a fixed‐effect model if no significant statistical heterogeneity was observed.

When possible, all data extracted were those relevant to an intention‐to‐treat analysis in which participants were analysed in groups to which they were assigned. We noted the time points at which outcomes were collected and reported.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If a sufficient number of studies were identified, we performed subgroup analyses for the following.

Cancer site.

Type of intervention (i.e. supervised, home‐based, etc).

Age of individuals (i.e. elderly versus non‐elderly).

Current treatment (currently undergoing treatment versus not currently undergoing treatment).

Participants with metastatic disease (metastatic cohort versus non‐metastatic cohort).

Accordance with behaviour change theory.

Interventions in obese individuals (mean body mass index (BMI) of intervention group > 30 kg/m2 versus mean BMI of intervention group < 30 kg/m2).

Sensitivity analysis

Methodological strength was judged using Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias to identify studies of high and low quality (Higgins 2011). Sensitivity analyses were performed with the studies of low quality excluded.

Summary of findings

To assess the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome of the meta‐analysis, we employed the GRADE approach. The GRADE profile (https://gradepro.org) enabled us to import data directly from Review Manager 5.3 to create Table 1. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall certainty of the evidence from studies included in the meta‐analysis. Risk of bias, inconsistency of the data, the preciseness of the data publication bias and the indirectness of the data were all considered in assessing the quality of the data.

We downgraded the evidence from 'high' certainty by one level for serious (or by two for very serious) concerns for each limitation.

High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

The following outcomes were included in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: eight to 12 weeks of follow‐up)

Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: eight to 12 weeks of follow‐up sensitivity analysis)

Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: six months of follow‐up)

Aerobic exercise tolerance (breast cancer: eight to 12 weeks of follow‐up)

Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: combination of supervised and home‐based exercise: eight to 12 weeks of follow‐up)

Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: supervised exercise: eight to 12 weeks of follow‐up)

Aerobic exercise tolerance (all cancers: home‐based exercise: eight to 12 weeks of follow‐up)

Results

Description of studies

Please see Table 2, 'Summary of included studies'. See 'Characteristics of included studies'; 'Characteristics of excluded studies'; 'Characteristics of studies awaiting classification'; and 'Characteristics of ongoing studies'.

1. Summary of included studies.

| Study | Exercise components | n | Meets Rock et al guidelines? | Adherence summary | At least 75% adherence? | High risk of bias? | Change in AET reported? | Adverse effects |

| Cadmus 2009 | Aerobic | 37, 38 (intervention vs control) | 33% reported 150 minutes/week of moderate intensity aerobic exercise at an average of 76% HR, for six months | 75% of women were doing between 90 and 119 minutes of moderate intensity aerobic activity per week at six months | Yes; for up to 119 minutes per week | No | Not reported | Five of the 37 women randomly assigned to exercise experienced an adverse effect; two were related to the study (plantar fasciitis) |

| Daley 2007a | Aerobic | 34, 36, 38 (intervention, sham, control, respectively) |

No | 77% of the exercise therapy; attended 70% (at least 17 of 24 sessions) or more of sessions | Unclear | Yes; outcome assessors were not blinded to participants’ group allocation | Yes | Three withdrawals in the intervention group: unclear as to why this occurred. Some withdrawals because of medical complications in placebo and control arms but unclear whether study related |

| Drouin 2005 | Aerobic | 13 intervention, 8 placebo stretching controls | Unclear | Participants in the intervention group averaged 3.6 days per week of aerobic exercise over an 8‐week period | Unclear | No | Yes | None reported |

| Kaltsatou 2011 | Aerobic | 14, 13 (intervention vs control) | Unclear | Not reported | Not reported | Yes; method of measuring exercise and adherence not reported | Not reported | None reported |

| Kim 2006 | Aerobic | 22,19 (intervention vs control). | No | Average weekly frequency of exercise was 2.4 ± 0.6 sessions, and average duration of exercise within prescribed target HR was 27.8 ± 8.1 minutes per session. Overall adherence was 78.3% ± 20.1% | Yes | Yes; data missing for 45% of the cohort | Yes | Reasons for withdrawal included personal problems (n = 2), problems at home (n = 2), problems related to chemotherapy (n = 3), thrombophlebitis in the lower leg (n = 2), non-exercise‐related injuries (n = 1), and death (n = 1). Unclear to which arm of the study these date relate |

| Pinto 2003 | Aerobic | 12, 12 (intervention vs control) |

Unclear | Participants attended a mean of 88% of the 36‐session supervised exercise programme | Yes | Yes; 38% lost to follow‐up. Exercise tolerance test was performed but no control group comparison data were reported | Yes | None reported; however, it is unclear why the six controls dropped out |

| Pinto 2005 | Aerobic | 43, 43 (intervention vs control) | Unclear | At week 12, intervention participants reported a mean of 128.53 minutes/week of moderate intensity exercise. However, no changes were reported in the accelerometer data in the intervention group (change score = ‐0.33 kcal/hour) | Less than 75% of the intervention group was meeting the prescribed goal after week 4 | Yes; significantly more control group participants were receiving hormone treatment. Accelerometer data do not support the self‐reported physical activity behaviour | Yes | Not clear whether chest pain was related to exercise in dropout whose participation was terminated |

| Pinto 2011 | Aerobic | 20, 26 (intervention vs control) | Three‐day PAR questionnaire indicates that 64.7% of the intervention group and 40.9% of the control group were achieving the guidelines at three months | Correlation between self‐reported moderate intensity exercise and accelerometer data at three‐month follow‐up, when the only significant between‐group change is reported: r = 0.32 | No | Yes; accelerometer data were not reported; also, cited correlation is weak (0.32). Further, substantial contamination was noted in the control group | Yes | One cancer recurrence in the control group at three months |

| Bourke 2011a | Aerobic and resistance | 9, 9 (intervention vs control) | Six weeks of resistance exercise twice a week | 90% attendance at the supervised sessions. 94% of independent exercise sessions were completed | Yes | No | Yes | One stroke in the intervention group, unrelated to the exercise programme |

| Hayes 2009 | Aerobic and resistance | 16, 16 (intervention vs control) | Unclear | Most women (88%) allocated to the intervention group participated in 70% or more of scheduled supervised exercise sessions | Unclear | Yes; adherence data on unsupervised aspect of the intervention are not clear | No | None reported |

| McKenzie 2003 | Aerobic and resistance | 7,7 (intervention vs control) | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes; adherence to exercise not reported | Not reported | None reported |

| Musanti 2012 | Aerobic and resistance | Flexibility group (n = 13), aerobic group (n = 12), resistance group (n = 17), aerobic and resistance group (n = 13) | 12 weeks of resistance exercise two or three times per week | Mean percentages of adherence were as follows: flexibility = 85%, aerobic = 81%, resistance = 91% and aerobic plus resistance = 86% | Unclear | Yes; a significant number of dropouts belonged to the resistance exercise group (n = 8/13). Only 50% of activity logs were returned | Yes | Adverse effects were reported in two women during the study. In both cases, the women developed tendonitis: one in the shoulder and the other in the foot. Both had a history of tendonitis, and both received standard treatment |

| Perna 2010 | Aerobic and resistance | 51 participants in total. Numbers randomly assigned to each arm are unclear | Three months of resistance exercise three times per week | Women assigned to the structured intervention completed an average of 83% of their scheduled hospital‐based exercise sessions (only 4 weeks in duration), and 76.9% completed all 12 sessions. Home‐based component (8 weeks in duration) | Unclear | Yes; numbers randomly assigned to intervention and control groups are unclear, as are numbers completing in each arm | Not reported | Unclear |

| al‐Majid 2015 | Aerobic | 7,7 (intervention vs control) | No | Adherence to per‐protocol exercise sessions was very high, ranging between 95% and 97%. | Yes | No | Yes | None reported |

| Bourke 2014 | Aerobic and resistance | 25,25 (intervention vs control) | Yes; 6 weeks of resistance exercise | Adherence was 94% for the supervised and 82% of the prescribed independent exercise sessions over the first 12 week. | Yes | Yes incomplete outcome data at 6 months. | Yes | None reported |

| Campbell 2017 | Aerobic | 10 in exercise intervention, 9 in delayed exercise control | 150 minutess per week of moderate‐vigorous aerobic exercise for 24 weeks. | Participants attended 88% of supervised gym sessions (mean 1.8 sessions/ week and 87.5 minutes/week), and participants met 82% of the prescribed exercise targets (mean intensity 74.5% HRR). Home session completion was 87% (mean 2.4 sessions/week and 101.5 minutes/week), and participants met 87% of the prescribed exercise targets (mean intensity 73.5% HRR) | Yes | Yes; Low study recruitment rate. | Yes | None reported |

| Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b | Aerobic | 33,33 (intervention vs control) | Three sixty minute sessions per week for 8 weeks. | All intervention group completed more than 85% of the 24 water exercise sessions, showing a high adherence rate to the program. | Yes | No | Not reported | One participant in the intervention dropped out due to a recurrence of breast cancer during the program. Three women reported a transient increase of oedema, and four women noted an increase in fatigue immediately after the beginning of the first session, which improved in the next few days. These women did not dropout of the study. No other adverse effects were reported. |

| Cavalheri 2017 | Aerobic and resistance | 9, 8 (intervention vs control) | Yes; six weeks of resistance exercise. | Nine of the participants randomised to the EG, four (44%) adhered to exercise training by completing 15 or more training sessions (i.e.,≥60%). | No | Yes; missing patient data in both arms with no reasons given. | Yes | One participant completed four sessions and another completed six sessions. Both stopped training as they felt unwell. They completed some of the post‐intervention assessments and were later diagnosed with a primary cancer other than lung cancer. |

| Kim 2017 | Aerobic and resistance | 15, 15 (intervention vs control) | Three sixty minute sessions per week for 12 weeks. | Vague statement: Two participants did not fulfil the required exercise | Unclear | Yes; Age differences between groups in baseline demographics were present. Adherence data is vague. | Not reported | None reported |

| Mohamady 2017 | Aerobic | 15, 15 (intervention vs control) | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes; No adherence data. | Unclear | Unclear |

| Rogers 2015 | Aerobic | 110, 112 (intervention vs control) | Yes | Adherence to the intervention was 98 % for supervised exercise sessions, 96 % for update sessions, and 91 % for discussion group sessions. | Yes | Yes; differences in objective and subjective measures of physical activity reported | Yes | Related expected adverse events in the intervention group included back or lower extremity musculoskeletal pain or injury (n = 14), heart rate monitor rash (n = 1), fall while walking (n = 1), breast reconstruction (n = 3), and chest pain during treadmill fitness test (n = 1) |

| Scott 2013 | Aerobic and resistance | 47, 43 (intervention vs control) | Yes, six weeks of resistance exercise. | Adherence for the intervention group was 80% | Yes | No | Yes | None reported. |

| Thomas 2013 | Aerobic | 35, 30 (intervention vs control) | Yes | The exercise goal was 150 minutes/week of moderate intensity aerobic exercise; 33% of women achieved this amount. 57% of women achieved 80% of the exercise goal or 120 minutes/week, and 75% of women achieved 90 minutes/week. | No | Yes; not all outcomes were reported and low recruitment rate. | Not reported | None reported. |

| Irwin 2015 | Aerobic and resistance | 61, 60 (intervention vs control) | Yes | Women randomly assigned to exercise also reported their exercise prospectively in daily activity logs and reported an average 119 minutes per week of aerobic exercise, with an average of 70% of strength‐training sessions completed. Women randomly assigned to exercise increased their physical activity by an average 159 minutes per week, compared with 49 minutes per week in the usual‐care group. | No | No | Yes | 5 participants had to discontinue the use of Atromatise inhibitors. |

AET = aerobic exercise tolerance.

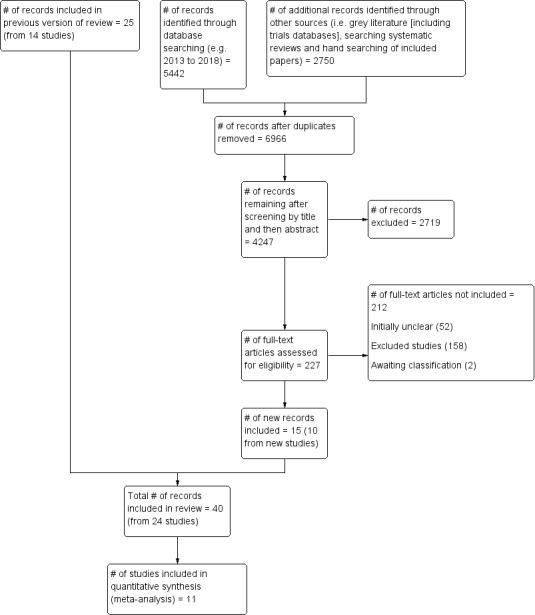

Results of the search

Figure 1 illustrates the process of the literature search and study selection for the review. The updated search identified 5442 unique records from databases searched. In addition, we identified 2750 records from grey literature and 'snowballing' techniques for this update. Given that the details of prescribed exercise are rarely reported in manuscript abstracts (e.g. frequency, intensity, duration of exercise prescription), this led to evaluation of a large number of manuscripts at full text stage (n = 227). From these full‐text articles, 212 manuscripts were excluded, leaving 15 publications from 10 unique studies included in the review (total unique studies = 23). Reasons for excluding these 212 publications and a subset of the original review total (n = 377) are covered in the Excluded studies section below.

1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Included studies

This update identified 15 publications from 10 new studies, which when combined with the studies from the original review equates to 40 publications in total from 23 studies. (al‐Majid 2015; Bourke 2014; Cadmus 2009; Campbell 2017; Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b; Cavalheri 2017; Daley 2007a; Drouin 2005; Hayes 2009; Irwin 2015; Kaltsatou 2011; Kim 2006; Kim 2017; McKenzie 2003; Mohamady 2017; Musanti 2012; Perna 2010; Pinto 2003; Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015; Scott 2013; Thomas 2013). One study (Bourke 2014) was a efficacy study, following on from a previous feasibility study (Bourke 2011a) from the original review.

For the 2018 update, we sent an additional 112 emails to request unpublished information for manuscripts that were unclear in reporting relative to our inclusion and exclusion criteria. We were able to include an additional seven published manuscripts and to exclude an additional eight published manuscripts on the basis of information received in correspondence from authors.

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included in the review. All included studies used a parallel‐group design with baseline assessment and follow‐up of 12 months maximum. All included studies were conducted using participant‐level randomisation. The format of reporting precluded data extraction for meta‐analytical combination in two studies (Drouin 2005; Pinto 2003). Sample size ranged from 14 to 222, with a total of 1372 participants included in this review (mean age range 51 to 72).

Participants

Twenty of the included trials were on breast cancer survivors (al‐Majid 2015; Cadmus 2009; Campbell 2017; Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b; Daley 2007a; Drouin 2005; Hayes 2009; Irwin 2015; Kaltsatou 2011; Kim 2006; Kim 2017; McKenzie 2003; Mohamady 2017; Musanti 2012; Perna 2010; Pinto 2003; Pinto 2005; Rogers 2015; Scott 2013; Thomas 2013); only two studies involved colorectal cancer (Bourke 2011a; Pinto 2011), one prostate cancer (Bourke 2014,) and one lung cancer (Cavalheri 2017). Of these studies, 12 included participants who were currently undergoing active treatment inclusive of hormone‐based therapy (al‐Majid 2015; Bourke 2014; Cadmus 2009; Daley 2007a; Drouin 2005; Irwin 2015; Kim 2006; Mohamady 2017; Musanti 2012; Perna 2010; Pinto 2005; Scott 2013). We found only one study that reported data from participants with metastatic disease (Bourke 2014), and six studies that were conducted in obese cohorts (i.e. mean BMI > 30 kg/m2; (Cadmus 2009; Drouin 2005; Mohamady 2017; Rogers 2015; Scott 2013; Thomas 2013). The majority of participants were white, and only five studies reported data from an ethnically diverse sample (al‐Majid 2015; Irwin 2015; Perna 2010; Rogers 2015; Thomas 2013). Comorbidities at baseline were largely unclear or unreported.

Interventions

Type of exercise

Fourteen studies prescribed exclusively aerobic exercise (al‐Majid 2015; Cadmus 2009; Campbell 2017; Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b; Daley 2007a; Drouin 2005; Kaltsatou 2011; Kim 2006; Mohamady 2017; Pinto 2003; Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015; Thomas 2013); the remaining RCTs used a mix of aerobic and resistance training (no exclusively resistance training studies met our inclusion criteria). Ten studies used a combination of supervised and home‐based exercise (Bourke 2011a; Bourke 2014; Cadmus 2009; Campbell 2017; Hayes 2009; Irwin 2015; Kim 2006; Perna 2010; Pinto 2003; Rogers 2015), four studies opted to use an exclusively home‐based design (Drouin 2005; Musanti 2012; Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011), and 10 studies were exclusively supervised studies (al‐Majid 2015; Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b; Cavalheri 2017; Daley 2007a; Kaltsatou 2011; Kim 2017; McKenzie 2003; Mohamady 2017; Scott 2013; Thomas 2013).

Exercise sessions and the role of exercise professionals and healthcare professionals

Contact with exercise professionals or study researchers ranged from two to three weekly supervised sessions (Rogers 2015), to weekly phone calls after an initial one‐to‐one exercise consultation (Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011). Most commonly however, supervised sessions were offered two to three times per week. Of note, seven studies (Drouin 2005; Kaltsatou 2011; Kim 2006; McKenzie 2003; Pinto 2003; Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011), placed restrictions on the control group regarding exercise behaviour during the course of the study, usually taking the form of direct instruction to refrain from changing exercise behaviour. However, the 2018 update found no additional studies that placed restrictions on the control group, usual activities were encouraged. Contact with healthcare professionals was not frequent amongst the studies, with three studies having healthcare professionals carry out medical assessments for eligibility (Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b; Kim 2017; Mohamady 2017), two studies having oncologists refer the participants onto the study, but it was not stated explicitly if they delivered any aspects of the intervention (al‐Majid 2015; Campbell 2017).

Level of exercise and adherence

Thirteen studies incorporated prescriptions that would meet the Rock 2012 recommendations for aerobic exercise (i.e.150 minutes per week); (Cadmus 2009; Campbell 2017; Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015) or resistance exercise (i.e. resistance training strength training exercises at least two days per week); (Bourke 2011a; Bourke 2014; Cavalheri 2017; Irwin 2015; Kim 2017; Musanti 2012; Perna 2010; Scott 2013). However, only eight of these studies reported 75% adherence to these guidelines, (Bourke 2011a; Bourke 2014; Campbell 2017; Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b; Irwin 2015; Kim 2017; Rogers 2015; Scott 2013).

Theoretical basis

Of the interventions provided, only six were explicitly based on a theoretical model (Daley 2007a; Musanti 2012; Perna 2010; Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015); the trans‐theoretical model was most common, followed by social cognitive theory and exercise, and self‐esteem theory. Only one intervention from the 2018 update was found to be based on a theoretical model (Rogers 2015).

Behaviour change techniques (BCT) and adherence

Full details of intervention BCT coding according to the CALO‐RE taxonomy for the previous review (Bourke 2013) and the 2018 update can be seen in Table 3 and Table 4 (respectively). In the previous review, there was a lack of identified studies that met the Rock 2012 guidelines. For this updated version of the review, our searches found more instances of studies (eight in total) that meet the 150 minutes per week or two strength sessions per week Rock 2012 target. Also, there were other studies with lower exercise targets but good adherence (i.e. over 75%). Hence, we presented BCTs in a hierarchy format: Tier 1 and Tier 2. Tier 1 BCTs are presented from interventions that set prescriptions which meet the Rock 2012 target and achieved 75% or more adherence. Tier 2 BCTs are presented from interventions that reported good adherence (i.e. 75% or more) but set prescriptions that are below the 150 minutes per week Rock 2012 target. BCTs reported in the eight Tier 1 trials are presented in Table 5. It is notable that four of these studies incorporated both a supervised and an independent exercise component as part of their intervention and four were exclusively supervised, with all placing no restrictions on the control group in terms of exercise behaviour. Six studies were included in Tier 2 BCTs and reported adherence of 75% or greater to a specified exercise aerobic prescription which was lower than the targets set in the Rock 2012 guidelines (al‐Majid 2015; Bourke 2011a; Bourke 2014; Cadmus 2009; Kim 2017; Scott 2013). BCTs reported in Tier 2 studies are presented in Table 6.

2. Original review Behaviour change components.

| Behaviour change technique | Bourke 2011a |

Cadmus 2009 YALE |

Daley 2007a | Drouin 2005 | Hayes 2009 | Kaltsatou 2011 | McKenzie 2003 | Musanti 2012 | Perna 2010 | Kim 2006 | Pinto 2003 | Pinto 2005 | Pinto 2011 |

| Theory | TTM | EXSEM | TTM | TTM | TTM SCT | ||||||||

| 1. Provide Info on consequences of behaviour in general | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 2. Provide Info on consequences of behaviour to the individual | |||||||||||||

| 3. Provide Info about others' approval | |||||||||||||

| 4. Provide normative info about others' behaviour | |||||||||||||

| Programme set goal | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 5. Goal setting (behaviour) | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 6. Goal setting (outcome) | |||||||||||||

| 7. Action planning | |||||||||||||

| 8. Barrier identification/Problem solving | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 9. Setting of graded tasks | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 10. Prompt review of behavioural goals | X | X | |||||||||||

| 11. Prompt review of outcome goals | |||||||||||||

| 12. Prompt rewards contingent on effort or progress towards goal | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| 13. Provide rewards contingent on successful behaviour | X | ||||||||||||

| 14. Shaping | |||||||||||||

| 15. Prompt generalisation of a target behaviour | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 16. Prompt self‐monitoring of behaviour | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 17. Prompt self‐monitoring of behavioural outcome | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 18. Prompt focus on past success | X | ||||||||||||

| 19. Feedback on performance provided | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 20. Information provided on where and when to perform behaviour | X | X | |||||||||||

| 21. Instruction provided on how to perform the behaviour | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 22. Modelling/Demonstration of behaviour | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| 23. Teaching to use prompts/cues | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| 24. Environmental restructuring | X | X | |||||||||||

| 25. Agreement on behavioural contract | X | ||||||||||||

| 26. Prompt practise | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 27. Use of follow‐up prompts | X | ||||||||||||

| 28. Facilitating social comparison | |||||||||||||

| 29. Planning social support/social change | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| 30. Prompt identification as role model/position advocate | |||||||||||||

| 31. Prompt anticipated regret | |||||||||||||

| 32. Fear arousal | |||||||||||||

| 33. Prompt self‐talk | |||||||||||||

| 34. Prompt use of imagery | |||||||||||||

| 35. Relapse prevention/coping planning | X | X | |||||||||||

| 36. Stress management/emotional control training | X | ||||||||||||

| 37. Motivational interviewing | |||||||||||||

| 38. Time management | |||||||||||||

| 39. General communication skills training | |||||||||||||

| 40. Stimulation of anticipation of future rewards |

EXSEM = exercise self‐esteem model; SCT = social cognitive theory; TTM = trans‐theoretical model.

3. 2018 Update Behaviour change components.

| Behaviour change technique | al‐Majid 2015 | Bourke 2014 | Campbell 2017 | Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b | Cavalheri 2017 | Irwin 2015 | Kim 2017 | Mohamady 2017 | Rogers 2015 | Scott 2013 | Thomas 2013 |

| Theory | SCT | ||||||||||

| 1. Provide Info on consequences of behaviour in general | x | x | |||||||||

| 2. Provide Info on consequences of behaviour to the individual | |||||||||||

| 3. Provide Info about others' approval | |||||||||||

| 4. Provide normative info about others' behaviour | |||||||||||

| Programme set goal | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 5. Goal setting (behaviour) | x | x | |||||||||

| 6. Goal setting (outcome) | |||||||||||

| 7. Action planning | |||||||||||

| 8. Barrier identification/Problem solving | x | x | |||||||||

| 9. Setting of graded tasks | x | x | x (implicit) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 10. Prompt review of behavioural goals | x | ||||||||||

| 11. Prompt review of outcome goals | |||||||||||

| 12. Prompt rewards contingent on effort or progress towards goal | x | ||||||||||

| 13. Provide rewards contingent on successful behaviour | |||||||||||

| 14. Shaping | |||||||||||

| 15. Prompt generalisation of a target behaviour | x (from linked paper Gilbert 2016* | x | |||||||||

| 16. Prompt self‐monitoring of behaviour | |||||||||||

| 17. Prompt self‐monitoring of behavioural outcome | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 18. Prompt focus on past success | |||||||||||

| 19. Feedback on performance provided | x | ||||||||||

| 20. Information provided on where and when to perform behaviour | x | x | |||||||||

| 21. Instruction provided on how to perform the behaviour | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 22. Modelling/Demonstration of behaviour | x | ||||||||||

| 23. Teaching to use prompts/cues | |||||||||||

| 24. Environmental restructuring | |||||||||||

| 25. Agreement on behavioural contract | |||||||||||

| 26. Prompt practise | x | x | |||||||||

| 27. Use of follow‐up prompts | |||||||||||

| 28. Facilitating social comparison | |||||||||||

| 29. Planning social support/social change | x | ||||||||||

| 30. Prompt identification as role model/position advocate | |||||||||||

| 31. Prompt anticipated regret | |||||||||||

| 32. Fear arousal | |||||||||||

| 33. Prompt self‐talk | |||||||||||

| 34. Prompt use of imagery | |||||||||||

| 35. Relapse prevention/coping planning | x | ||||||||||

| 36. Stress management/emotional control training | |||||||||||

| 37. Motivational interviewing | |||||||||||

| 38. Time management | |||||||||||

| 39. General communication skills training | |||||||||||

| 40. Stimulation of anticipation of future rewards |

4. Tier 1 BCTs ‐ trials which had 75% adherence to the Rock resistance or aerobic guidelines.

| BCT | Bourke 2014 | Campbell 2017 | Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b | Bourke 2011a | Rogers 2015 | Scott 2013 | Kim 2017 | Irwin 2015 | |

| Resistance | Aerobic | Aerobic | Resistance | Aerobic | Resistance | Resistance | Aerobic | Frequency of BCTs | |

| Programme set goal | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 8 |

| 9. Setting of graded tasks | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 7 | |

| 21. Instruction provided on how to perform behaviour | x | x | x | 3 | |||||

| 26. Prompt practise | x | x | 2 | ||||||

| 5. Goal setting (outcome) | x | x | 2 | ||||||

| 8. Barrier identification/problem solving | x | x | 2 | ||||||

| 1. Provide information on consequences of behaviour in general | x | x | 2 | ||||||

| 15. Prompt generalisation of a target behaviour | x | x | 2 | ||||||

| 17. Prompt self‐monitoring of behavioural outcome | x | x | 2 | ||||||

| 20. Information provided on where and when to perform behaviour | x | x | 2 | ||||||

| 19. Feedback on performance provided | x | 1 | |||||||

| 22. Modelling/demonstration of behaviour | x | 1 | |||||||

| 12. Prompt rewards contingent on effort or progress towards goal | x | 1 | |||||||

| 29. Planning social support/social | x | 1 | |||||||

| 35. Relapse prevention/coping planning | x | 1 |

BCTs: behaviour change techniques

5. Tier 2 BCTs ‐ trials which had 75% adherence to their specified aerobic exercise prescription.

| BCT | Bourke 2011a | al‐Majid 2015 | Bourke 2014 | Cadmus 2009 | Scott 2013 | Kim 2017 | |

| Frequency of BCTs | |||||||

| Programme set goal | x | x | x | x | x | x | 6 |

| 9. Setting of graded tasks | x | x | x | x | x | 5 | |

| 21. Instruction provided on how to perform behaviour | x | x | x | 3 | |||

| 1. Provide information on consequences of behaviour in general | x | x | 2 | ||||

| 26. Prompt practise | x | x | 2 | ||||

| 8. Barrier identification/problem solving | x | x | 2 | ||||

| 15. Prompt generalisation of a target behaviour | x | x | 2 | ||||

| 5. Goal setting (outcome) | x | 1 | |||||

| 16. Prompt self‐monitoring of behaviour | x | 1 | |||||

| 17. Prompt self‐monitoring of behavioural outcome | x | 1 | |||||

| 20. Information provided on where and when to perform behaviour | x | 1 | |||||

| 29. Planning social support/social | x | 1 | |||||

| 27. Use of follow‐up prompts | x | 1 |

BCTs: behaviour change techniques

Few interventions (Bourke 2014; Cadmus 2009; Daley 2007a; Kim 2006; Perna 2010; Rogers 2015) reported providing information on the consequences of behaviour (BCT #1). All interventions had programme set goals, which we have highlighted as being different for the purpose of this review to goal setting (behaviour) and goal setting (outcome). Only seven studies set exercise goals in conjunction with participants (BCT # 5) (Bourke 2014; Cadmus 2009; Daley 2007a; Perna 2010; Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015). These same seven studies also reported problem‐solving with barriers identified (BCT #8) and solutions facilitated. Three interventions (Daley 2007a; Perna 2010; Rogers 2015) which participants had some input into setting of goals were these reviewed (BCT #10). When monitoring did occur (BCT #16) or monitoring of outcome behaviour occurred (BCT #17), feedback on performance (BCT #19) was provided in only five out of 10 (Cadmus 2009; Perna 2010; Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015), which is important to note. Fourteen studies (Bourke 2011a; Bourke 2014; Cadmus 2009; Daley 2007a; Drouin 2005; Hayes 2009; Kaltsatou 2011; Kim 2006; Musanti 2012; Perna 2010; Pinto 2003; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015; Scott 2013) reported providing instruction on how to perform the behaviour (BCT #21), although it may be anticipated that this did occur but just was not reported. In addition, 15 studies prompted practise of the behaviour (BCT #26) (Bourke 2011a; Bourke 2014; Cadmus 2009; Daley 2007a; Drouin 2005; Hayes 2009; Kaltsatou 2011; Kim 2006; McKenzie 2003; Musanti 2012; Perna 2010; Pinto 2003; Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015), Only four studies used techniques to increase social support (BCT #29); (Bourke 2014; Cadmus 2009; Daley 2007a; Perna 2010). Other common BCTs included setting of graded tasks (i.e. increased exercise duration or intensity over time) and self‐monitoring of behaviour (exercise) and outcomes of behaviour (e.g. heart rate), although it is not clear for all interventions whether this was done primarily for data collection or as a mechanism of behaviour change.. Only three studies reported relapse prevention (BCT #35) (Daley 2007a; Perna 2010; Rogers 2015).

Measurement of exercise behaviour

Ten studies were identified that attempted to objectively validate independent exercise behaviour with accelerometers or heart rate monitoring (al‐Majid 2015; Bourke 2014; Cadmus 2009; Irwin 2015; Mohamady 2017; Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015; Scott 2013; Thomas 2013). Seven of these studies attempted to validate self‐reported independent exercise behaviour by using accelerometers or heart rate monitors (al‐Majid 2015; Bourke 2014; Irwin 2015; Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015; Thomas 2013), however in three studies (Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015), data either were not supportive of exercise behaviour recorded by participants or were not reported in their entirety.

Excluded studies

Reasons for excluding published studies included the following.

Non‐RCTs (e.g. review manuscripts, comment/editorial articles).

Mixed cancer cohorts or cohorts that included non‐cancer populations.

Studies that failed to describe essential metrics of exercise prescription used in the intervention (e.g. frequency, intensity, duration).

Studies involving active participants at baseline.

Studies involving hospital inpatients.

Interventions that provided follow‐up of less than 6 weeks.

Studies involving participants younger than 18 years of age.

All excluded studies (N = 180) for the 2018 update, are presented in the Characteristics of excluded studies. However for the original review only a subset of excluded studies could be included in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' section. This is a result of the large volume of studies that had to be full text screened (N = 402) and the high proportion (around 90%) that were excluded. In accordance with editorial advice, we divided this large number (N = 365) into initially unclear studies that required further investigation (N = 76) and those that clearly were not eligible after full text had been retrieved (N = 289). This approach is analogous to the approach adopted in recent reviews (Galway 2012), and is detailed in the existing PRISMA diagram (Figure 1).

For the 2018 update, we sent an additional 101 emails to corresponding authors to request additional information (regarding included studies, excluded studies and studies that we could not access) to determine eligibility and to supplement published data for this review.

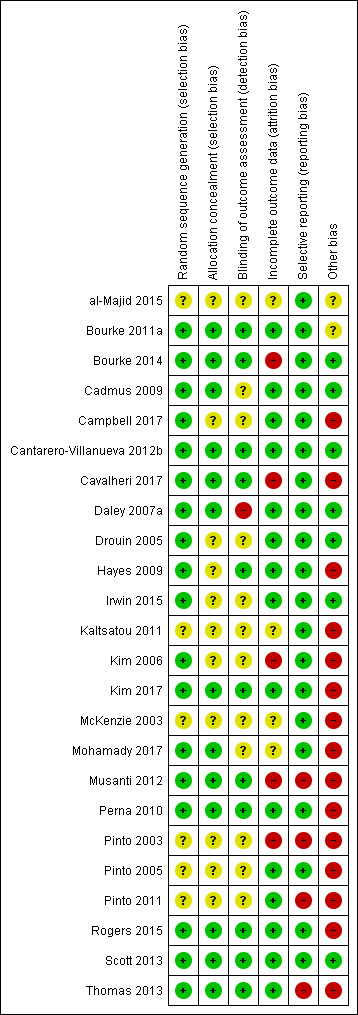

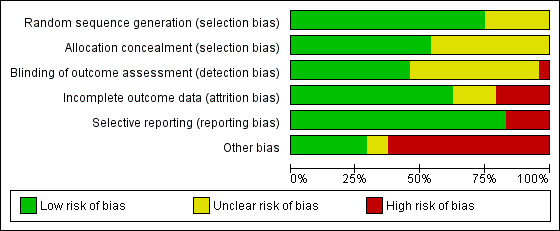

Risk of bias in included studies

Only seven studies were judged not to include a high risk of bias (al‐Majid 2015; Bourke 2011a; Cadmus 2009; Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b; Drouin 2005; Irwin 2015; Scott 2013). Full results of the methodological quality assessment for allocation bias, blinding, incomplete data outcome and selective reporting (along with justifications) are covered in the 'Risk of bias' tables for each study and are illustrated in Figure 2; Figure 3. Twelve studies stated that an intention‐to‐treat analysis was used (Bourke 2011a; Bourke 2014; Cadmus 2009; Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b; Cavalheri 2017; Daley 2007a; Irwin 2015; Perna 2010; Pinto 2005; Rogers 2015; Scott 2013; Thomas 2013).

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Eleven studies had an unclear risk in their description of concealment in randomisation allocation. However, no study was judged to have a high risk of bias in this respect.

Blinding

Eleven studies had undertaken the blinding of study assessors (Bourke 2011a; Bourke 2014; Cantarero‐Villanueva 2012b; Cavalheri 2017; Hayes 2009; Kim 2017; Musanti 2012; Perna 2010; Rogers 2015; Scott 2013; Thomas 2013). The remaining studies did not include enough information for the review authors to make a definitive judgement on this criterion.

Incomplete outcome data

Five studies were judged to have been subject to incomplete data outcome bias: Kim 2006 reported data from only 41 of 74 participants randomly assigned; Musanti 2012 reported that 13 women (24%) did not complete their assigned 12‐week programme; and Pinto 2003 did not report control group data for the exercise tolerance test. Bourke 2014 had incomplete outcome data at six months follow‐up. Cavalheri 2017 reported missing patient data in both arms with no reasons given.

Selective reporting

Most studies reported all listed outcomes; however, four studies were judged to omit outcomes from their results reporting. Musanti 2012 did not report waist and upper, mid and lower arm circumference outcomes; Pinto 2003 reported none of the physiological assessments in the control group at 12 weeks of follow‐up; Pinto 2011 did not report data derived from the use of accelerometers; and Thomas 2013 did not report on body fat or lean mass values and no data were given from food frequency questionnaire.

Other potential sources of bias

Other sources of bias found in the included studies that are worth highlighting include adherence data missing or not clear (Cavalheri 2017; Hayes 2009; Kaltsatou 2011; Kim 2017; McKenzie 2003; Mohamady 2017; Musanti 2012); high attrition at follow‐up (Pinto 2003); low recruitment rate (Bourke 2011a; Campbell 2017; Thomas 2013); Significant differences in participants excluded from study analysis/dropouts (Kim 2006; Musanti 2012; Pinto 2003); numbers randomly assigned to study arms with study completion rate unclear (Perna 2010); significant differences in cohorts at baseline (Kim 2017; Musanti 2012; Pinto 2003; Pinto 2005); and inconsistencies between objective and subjective measures of exercise behaviour (Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011; Rogers 2015). Insufficient information was reported to permit a judgement about any single element of bias because of lack of data (al‐Majid 2015; Bourke 2011a; Cadmus 2009; Campbell 2017; Drouin 2005; Hayes 2009; Irwin 2015; Kaltsatou 2011; Kim 2006; McKenzie 2003; Mohamady 2017; Pinto 2003; Pinto 2005; Pinto 2011).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcome

To assess the effects of interventions designed to promote exercise behaviour in sedentary people living with and beyond cancer

Please see Table 2, 'Summary of included studies'. As it is not meaningful to interpret individually the component metrics of aerobic (frequency, intensity and duration) or resistance exercise (frequency, intensity, type of exercise, sets and repetitions) behaviour, these primary outcomes are presented in the narrative synthesis below of interventions achieving 75% or greater adherence.