Abstract

The relative abundance of thermogenic beige adipocytes and lipid-storing white adipocytes in adipose tissue underlie its metabolic activity. The roles of adipocyte progenitor cells, which express PDGFRα or PDGFRβ, in adipose tissue function have remained unclear. Here, by defining the developmental timing of PDGFRα and PDGFRβ expression in mouse subcutaneous and visceral adipose depots, we uncover depot specificity of pre-adipocyte delineation. We demonstrate that PDGFRα expression precedes PDGFRβ expression in all subcutaneous but in only a fraction of visceral adipose stromal cells. We show that high-fat diet feeding or thermoneutrality in early postnatal development can induce PDGFRβ+ lineage recruitment to generate white adipocytes. In contrast, the contribution of PDGFRβ+ lineage to beige adipocytes is minimal. We provide evidence that human adipose tissue also contains distinct progenitor populations differentiating into beige or white adipocytes, depending on PDGFRβ expression. Based on PDGFRα or PDGFRβ deletion and ectopic expression experiments, we conclude that the PDGFRα/PDGFRβ signaling balance determines progenitor commitment to beige (PDGFRα) or white (PDGFRβ) adipogenesis. Our study suggests that adipocyte lineage specification and metabolism can be modulated through PDGFR signaling.

KEY WORDS: Adipose tissue, White and brown adipogenesis, PDGFR, Progenitor, Adipocyte

Summary: White and beige adipocytes arise from distinct progenitor cell lineages. In both mice and humans, beige and white adipogenesis is induced by PDGFRα and PDGFRβ signaling, respectively.

INTRODUCTION

Adipose tissue (AT), commonly referred to as fat tissue, is a highly dynamic organ that mediates systemic homeostasis. White adipose tissue (WAT) expansion is the hallmark of obesity. Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) overgrowth and dysfunction fuel the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer (Sun et al., 2011). In contrast, subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) has been shown to have anti-diabetic properties, which is, at least in part, explained by its ability to buffer lipids by oxidizing them (Rosen and Spiegelman, 2014). Distinct cell types composing AT, including adipocytes, adipose stromal cells (ASCs), endothelial cells and infiltrating leukocytes execute diverse functions implicated in disease pathogenesis (Sun et al., 2011). Adipocytes, the differentiated lipid-rich cells and the main constituents of AT, are heterogeneous and have depot-specific ontogeny (Chau et al., 2014). In adults, major AT depots are composed of white adipocytes that store triglycerides in unilocular lipid droplets. In contrast, AT in neonates contains mitochondria-rich adipocytes specialized in burning energy through muscle-independent adaptive thermogenesis in response to sympathetic nervous system stimuli (Cannon and Nedergaard, 2004). The organ specialized to execute this function is brown adipose tissue (BAT), which has fixed anatomical locations (Cinti, 2009). While in adulthood it is prominent mainly in rodents, its presence and function in adult humans has also been demonstrated (Porter et al., 2016; Rosen and Spiegelman, 2014). In both mice and humans, major SAT depots contain inducible/recruitable brown-like (beige, also known as brite) adipocytes, which are functionally similar to brown adipocytes in the canonical (constitutive) BAT (Kajimura et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2012). In both brown and beige adipocytes, thermogenic energy dissipation relies on the function of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). This protein, which is not expressed in white adipocytes or in any other cells in the body, leaks protons to uncouple substrate oxidation from ATP synthesis, resulting in heat dissipation (Cannon and Nedergaard, 2004; Rosen and Spiegelman, 2014). Both BAT and beige fat can counteract glucose intolerance and other metabolic consequences of obesity (Lowell et al., 1993; Tseng et al., 2010). Metabolic effects resulting from AT ‘beiging’ in animal models have suggested that activation of beige adipocytes in humans could be beneficial (Orci et al., 2004).

The process through which adipocytes in AT change from beige to white, or vice versa, in development or in response to physiological cues is not completely understood. Lineage-tracing data have provided evidence for trans-differentiation of existing adipocytes (Lee et al., 2015). Another mechanism for AT conversion is the recruitment of new adipocytes (Berry et al., 2016). Such de novo generation of beige adipocytes is observed in SAT upon β3-adrenoceptor stimulation (Seale et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2013). Proliferation of progenitor cells and their differentiation into pre-adipocytes and, subsequently, into hyperplastic adipocytes underlies AT remodeling in conditions of positive energy balance (Kras et al., 1999; Sun et al., 2011). The identity of adipocyte progenitors has remained controversial (Berry et al., 2016). We and others have shown that adipocyte progenitors are perivascular cells that can be isolated from the stromal/vascular fraction (SVF) as a component of the ASC population (Berry et al., 2014; Rodeheffer et al., 2008; Tang et al., 2008; Traktuev et al., 2008). Like mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) in the bone marrow and other organs, ASCs have been reported to express platelet-derived growth factor receptors α (PDGFRα) and β (PDGFRβ), the tyrosine kinases that mark mesenchymal cells (Turley et al., 2015). PDGFR activity is regulated primarily by ligands that function as dimers composed of two glycoprotein chains (Hoch and Soriano, 2003). PDGFRα is activated by homodimers PDGF-AA and PDGF-BB, PDGF-CC or heterodimer PDGF-AB, whereas PDGFRβ is activated by PDGF-BB and PDGF-DD (He et al., 2015; Iwayama et al., 2015). In some tissues, PDGFRα/PDGFRβ receptor heterodimers have been reported (Hoch and Soriano, 2003; Seki et al., 2016). Both PDGFRα and PDGFRβ are expressed by ASCs cultured ex vivo (Traktuev et al., 2008). However, ASCs in adult mouse AT are heterogeneous and in vivo their subpopulations predominantly express only PDGFRα or only PDGFRβ (Daquinag et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2012).

The identities of cell populations marked by PDGFRα and PDGFRβ during AT development and in adulthood have been debated. Lineage-tracing experiments have shown that PDGFRα marks progenitors of all white and beige adipocytes in SAT (Berry et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2012). PDGFRβ has also been reported to mark adipocyte progenitors (Tang et al., 2008). We recently reported that a compound targeting PDGFRβ-high ASCs, but sparing PDGFRα-high ASCs, induces AT beiging in mice (Daquinag et al., 2015). This suggested that beige adipocytes are derived from PDGFRα-high/PDGFRβ-low ASCs in adulthood. Consistent with these observations, PDGFRα signaling was shown to activate AT beiging (Seki et al., 2016). However, PDGFRβ expression in a subset of beige mouse adipocyte progenitors has also been reported (Vishvanath et al., 2016).

The potential role of PDGFR signaling in adipocyte progenitors has not been explored. To date, it is unclear in which cells PDGFRα signaling is important. The role of PDGFRβ signaling in progenitor cells has also remained controversial. The goal of this study was to analyze the contribution of the PDGFRβ+ lineage to adipogenesis in distinct AT depots during neonatal development and to establish the role of PDGFRα and PDGFRβ signaling in adipocyte lineage specification. We conclude that the progenitor pool with dominant PDGFRα expression and signaling generates beige adipocytes, whereas the progenitor pool with dominant PDGFRβ expression and signaling generates white adipocytes in both mice and humans.

RESULTS

Distinct progenitor lineages generate adipocytes in SAT and VAT

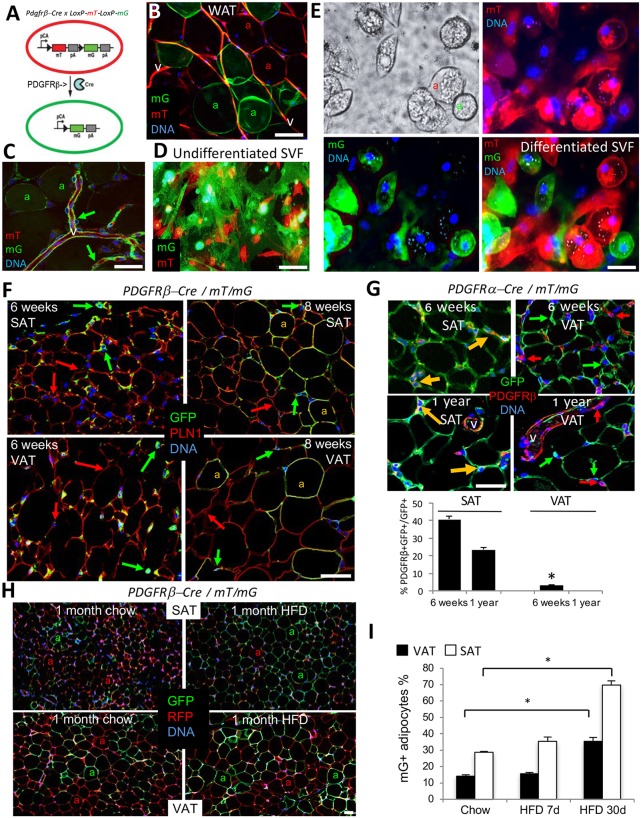

We first investigated the significance of PDGFRβ expression in adipocyte progenitors in a mouse model. To track the PDGFRβ+ lineage in AT, we used the genetic approach based on the Cre/loxP technology. Upon crossing a reporter strain termed mT/mG (Muzumdar et al., 2007) with mice expressing the Cre recombinase under a promoter of interest, the progeny tissues are composed of cells fluorescing red or green. Cells not expressing Cre fluoresce red due to expression of a loxP-flanked red fluorescent protein (RFP) membrane tdTomato (mT). The loxP-mT-loxP cassette also blocks the expression of the downstream gene coding for membrane green (mG) fluorescent protein (GFP) (Fig. 1A). Therefore, cells expressing the Cre recombinase driven by a promoter of interest, as well as their derivatives, become indelibly green due to loxP-flanked mT excision and induction of mG. Lineage tracing with an inducible Pdgfrb-Cre model reported recently indicated that PDGFRβ+ lineage predominantly generates white adipocytes in adulthood (Vishvanath et al., 2016). Here, we used a constitutive Pdgfrb-Cre driver strain with a confirmed specifically perivascular pattern of Cre expression (Cuttler et al., 2011) to account for all PDGFRβ+ lineage adipocytes generated during development. As shown in Fig. 1B and Fig. S1A, both SAT and VAT of 10-week-old Pdgfrb-Cre × mT/mG progeny have a mixture of mG+ and mT+ adipocytes that are derived from PDGFRβ+ (mG+) or PDGFRβ− (mT+) stromal cells. As a control, we used adult Pdgfra-Cre; mT/mG mice, in which all adipocytes are reportedly mG+ (Berry et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2012). Consistent with these previous reports, in SAT of these mice all adipocytes were found to be of the PDGFRα+ lineage (Fig. S1B). Notably, in VAT of Pdgfra-Cre; mT/mG mice, mT+ adipocytes were also observed (Fig. S1B), indicating that PDGFRα-negative lineage also contributes to VAT adipogenesis. Consistent with previously reported PDGFRβ expression pattern (Daquinag et al., 2011), confocal microscopy of AT vasculature from Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mice revealed vast PDGFRβ+ lineage tracing of ASC in the perivascular niche surrounding the PDGFRβ-negative endothelium (Fig. 1C). We then analyzed the SVF of Pdgfrb-Cre × mT/mG progeny containing the PDGFRβ+ lineage (49.2±4.41%) and PDGFRβ− lineage (50.8±4.42%) ASCs (Fig. 1D). By inducing adipogenesis, we confirmed that both PDGFRβ+ and PDGFRβ− ASC lineages are capable of differentiating into the adipocytes, which was the case for both SAT and VAT (Fig. 1E; Fig. S1C).

Fig. 1.

Distinct lineages generate white adipocytes in SAT and VAT. (A) Schematic for lineage tracing of PDGFRβ+ cells and their derivatives (mG+) among other cells (mT+). pCa, chicken actin promoter; triangle, LoxP; pA, polyadenylation site. (B) A whole mount of SAT from a 10-week-old Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mouse showing mT+ and mG+ adipocytes (a) and mT+ vasculature (v). (C) Confocal microscopy analysis of SAT from a 10-week-old Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mouse (whole mount) showing a large blood vessel (v) with perivascular mG+ ASCs (arrows). (D) Adherent mT+ and mG+ ASCs in the cell culture of SVF from SAT of a 10-week-old Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mouse. (E) SVF from D subjected to white adipogenesis induction. There are lipid droplets in mT+ and mG+ adipocytes (a). (F) Confocal immunofluorescence on paraffin wax-embedded sections of SAT and VAT from 6-week-old and 8-week-old Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mice subjected to perilipin 1 (red) in adipocytes/GFP (green) in ASC. Yellow indicates mG/perilipin 1 colocalization in adipocytes (a) at week 8. Arrows indicate GFP+ and RFP+ cells. (G) Paraffin wax-embedded sections of VAT and SAT from 6-week-old and 1-year-old Pdgfra-Cre; mT/mG mice subjected to PDGFRβ (red)/GFP (green) immunofluorescence. Yellow arrows indicate mG/PDGFRβ colocalization. Graph shows the quantification of PDGFRβ and GFP colocalization in the images. (H) Paraffin wax-embedded sections of SAT and VAT from 12-week-old Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mice fed chow or high-fat diet (HFD) for 1 month subjected to RFP (red)/GFP (green) immunofluorescence. mT+ and mG+ adipocytes (a) are indicated. (I) Time-course of an increase in the frequency of mG+ adipocytes from experiment in H. Data are mean±s.e.m. for multiple fields (n=10); *P<0.05 (Student's t-test). In all panels, colocalization is indicated with yellow arrows; nuclei are blue. Scale bars: 50 µm. Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

Next, we assessed the recruitment of the PDGFRβ+ lineage during mouse development using immunofluorescence analysis of AT paraffin sections with GFP antibodies. In Pdgfrb-Cre ×mT/mG progeny, lineage tracing was observed in the perivasculature, but not in endothelial or hematopoietic cells (Fig. S1D), consistent with the pattern of PDGFRβ expression (Fig. S1E). As expected, there was a concordance of mG and PDGFRβ expression in perivascular cells of both SAT and VAT (Fig. S1F), confirming that this strain is appropriate for Pdgfrb lineage tracing. In mice raised in regular housing conditions at up to 6 weeks of age, both SAT- and VAT-only mG+ ASCs were observed in streaks of connective tissue separating AT lobes (Fig. 1F). As assessed using perilipin 1 immunofluorescence, 13.1% of VAT and 30% of SAT adipocytes became Pdgfrb+ lineage traced at 8 weeks of age (Fig. 1F). This pattern is different from that reported for Pdgfra-Cre, which starts tracing most adipocytes during embryogenesis (Berry et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2012), as we confirmed using both SAT and VAT of Pdgfra-Cre; mT/mG mice (Fig. 1G). Our data indicate that while the Pdgfra+ lineage engages in adipogenesis early in development, Pdgfrb+ lineage adipocyte recruitment is activated postnatally.

We then used immunofluorescence to test whether PDGFRβ is induced in PDGFRα+ lineage cells. In SAT of 6-week-old and 1-year-old Pdgfra-Cre; mT/mG mice, PDGFRβ colocalized with GFP in over 20% of cells, indicating PDGFRβ expression in PDGFRα+ lineage stroma (Fig. 1G). In contrast, in VAT, over 95% of PDGFRβ+ cells were GFP negative in both 6-week-old and 1-year-old Pdgfrα-Cre; mT/mG mice (Fig. 1G). This indicates that in VAT, PDGFRβ is induced in stromal cells that have not expressed PDGFRα. These results were confirmed by a reciprocal PDGFRα/GFP immunofluorescence analysis of AT from Pdgfrb-Cre × mT/mG progeny: PDGFRα/GFP colocalization was also observed in SAT but not in VAT in both 6-week-old and 1-year-old animals (Fig. S1G). Perilipin 1 colocalization assessed using immunofluorescence confirmed that, in SAT, Pdgfrb expression is initially induced in PDGFRα+ progenitor cells (Fig. S1H). To further validate these results through an independent methodology, we performed flow cytometry on the SVF from Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mice. Again, this revealed that the majority of mG+ cells expressed PDGFRα in SAT, whereas mG+/PDGFRα+ cell frequency was at the background level in VAT (Fig. S1I). These results suggest that, in SAT, the PDGFRβ+ population is derived from cells that previously expressed PDGFRα, whereas in VAT it arises, at least to a degree, from a separate progenitor lineage.

Next, we analyzed the effect of physiological stimuli on PDGFRβ+ lineage recruitment. Analysis of chow-fed Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mice of different ages revealed a trend for higher frequency of PDGFRβ+ lineage adipocytes in SAT and VAT of 6-month-old mice compared with 3- and 2-month-old mice (Fig. S2A). As above, mG+ adipocyte frequency was calculated based on perilipin 1/GFP co-immunofluorescence (Fig. S2B). To test whether diet-induced obesity (DIO) development relies on PDGFRβ+ progenitor recruitment, we placed 8-week-old mice on chow or high-fat diet (HFD) for 1 month. In 12-week-old Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mice fed chow, ∼30% of adipocytes in SAT and 14% in VAT were found to be of the PDGFRβ+ lineage, as determined by GFP/RFP immunofluorescence (Fig. 1H,I). After 1 month of HFD feeding, the frequency of PDGFRβ+ lineage (GFP+) adipocytes in these 12-week-old DIO mice was higher than in chow-fed mice in both SAT (70%) and VAT (38%) (Fig. 1H,I). Notably, the newly recruited PDGFRβ+ lineage adipocytes were hypertrophic (Fig. 1H). These results suggest that the PDGFRβ+ lineage is engaged to generate white adipocytes that accumulate in conditions of positive energy balance. We also analyzed PDGFRβ+ lineage in interscapular BAT. In chow-fed 12-week-old mice, fewer than 10% of BAT adipocytes were of PDGFRβ+ lineage (Fig. S2C). Four weeks of HFD feeding significantly increased the frequency of BAT PDGFRβ+ lineage adipocytes, which tended to have larger lipid droplets (Fig. S2C). Interestingly, continued HFD feeding did not further increase GFP+ adipocyte frequency in either SAT or VAT (Fig. S2D). Moreover, HFD feeding failed to increase GFP+ adipocyte frequency in either SAT or VAT of 6-month-old and 11-month-old mice (Fig. S2E). This indicates that Pdgfrb lineage recruitment, inducible by HFD feeding, is efficient only transiently in postnatal development.

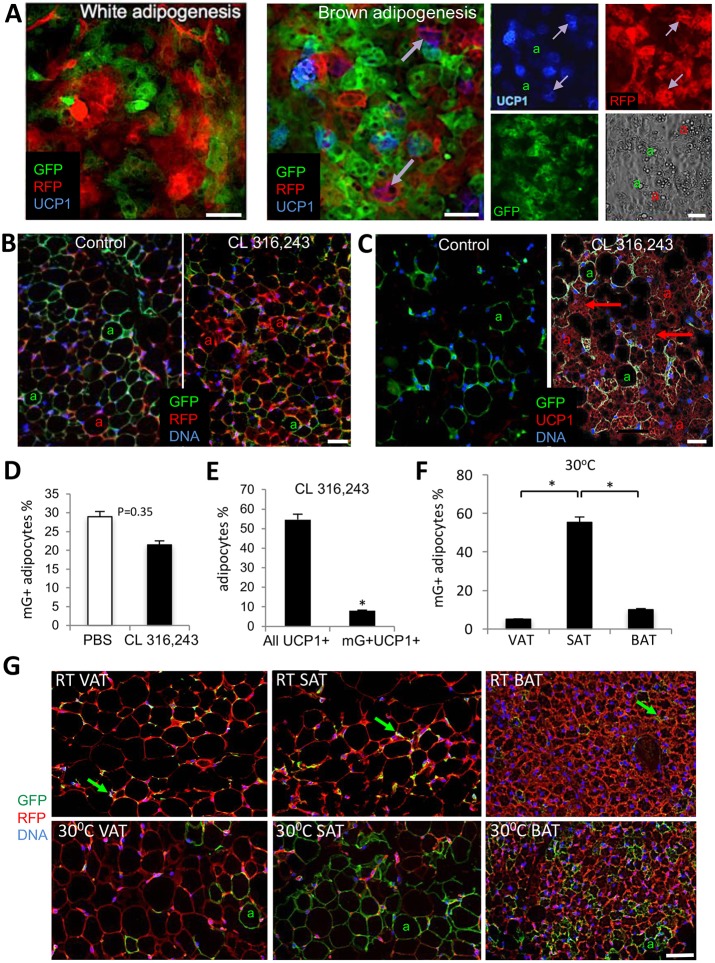

The PDGFRβ+ lineage contribution to the beige adipocyte pool is minimal

We then tested whether the PDGFRβ+ lineage could also be recruited to make beige adipocytes. Upon inducing brown (but not white) adipogenesis in the SVF of Pdgfrb-Cre×mT/mG progeny, we observed differentiation of UCP1+ adipocytes mainly (70%) from the progenitors of PDGFRβ-negative lineage (Fig. 2A). To confirm this in vivo, we stimulated the sympathetic nervous system by injecting the β3-adrenoceptor agonist CL 316,243 (Lee et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013) into Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mice. As expected, the treatment resulted in SAT beiging, as revealed by a decrease in adipocyte size, lipid droplet fragmentation and UCP1 expression (Fig. 2B,C). This was not accompanied by a significant increase in mG+ adipocytes; instead they displayed a trend for decreased abundance (Fig. 2B,D), suggesting that beige adipocytes are generated de novo from the Pdgfrb-negative lineage. Indeed, the majority of mG+ adipocytes did not express UCP1 (Fig. 2E). Similar observations were made for mice in which SAT beiging was induced by housing at 4°C or tumor grafting (Fig. S2F). Our results suggest that the PDGFRβ+ lineage is not considerably recruited by β3 adrenoceptor-mediated signaling and does not substantially contribute to the pool of beige adipocytes in SAT.

Fig. 2.

The PDGFRβ+ lineage contribution to the beige adipocyte pool is minimal. (A) Cultured SVF from SAT of Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mouse were subjected to white or brown adipogenesis induction. Fixed cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence with RFP (red), GFP (green) and UCP1 (blue) antibodies. Arrows indicate expression of UCP1 in mT+ (purple) but not in mG+ adipocytes (a). Separate channels are shown on the right; phase-contrast image shows adipocyte lipid droplets. (B,C) Paraffin wax-embedded sections of SAT from Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mice 7 days after injection with PBS (control) or the β3AR activator CL 316,243. Nuclei are blue. (B) Immunofluorescence with RFP (red) and GFP (green) antibodies. (C) Immunofluorescence with UCP1 (red) and GFP (green) antibodies. UCP1 expression is present in multilocular mT+ adipocytes (arrows) but not in unilocular mG+ adipocytes (a). (D) Quantification of data from B. (E) Quantification of data from C. (F) Quantification of 30°C data from G. (G) Paraffin wax-embedded sections of VAT, SAT and BAT from 6-week-old Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mice after 7 days of housing at 30°C or at room temperature subjected to anti-RFP (red)/GFP (green) immunofluorescence showing mG+ ASCs (arrows) at room temperature and mG+ adipocytes (a) at 30°C. In all panels, nuclei are blue. Scale bars: 50 µm. Data are mean±s.e.m. for multiple fields (n=10). *P<0.05 (Student's t-test). Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

Next, we tested whether the PDGFRβ+ lineage is activated upon suppression of sympathetic tone, which can be achieved by housing at warm temperature (Ravussin et al., 2014). We placed 5-week-old Pdgfrb-Cre; mT/mG mice at 30°C for 1 week, after which WAT depots were analyzed. Compared with mice housed at room temperature, which do not have mG+ adipocytes at 6-weeks of age, mice housed at 30°C had 55% adipocytes in SAT and 5% adipocytes in VAT Pdgfrb+ lineage traced (Fig. 2F-G). Housing in thermoneutrality was also sufficient to generate 10% of PDGFRβ+ lineage adipocytes in interscapular BAT, in which mainly non-differentiated mG+ cells were observed in control RT-housed animals (Fig. 2G). These results suggest that the Pdgfrb+ lineage is engaged postnatally upon sympathetic tone suppression in SAT, VAT and BAT.

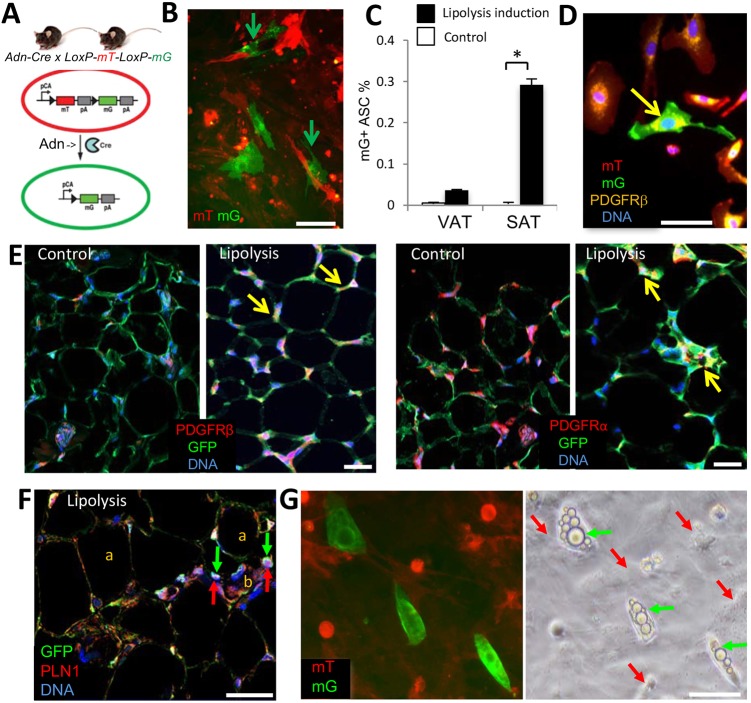

SAT remodeling results in adipocyte-derived stromal cells

In cell culture, adipocytes can undergo lipolysis, lose lipid droplets and revert to the fibroblastoid stromal cell morphology (Wei et al., 2013). However, it has not been tested whether such a conversion can take place in vivo. To address this, we used a mouse strain in which expression of Cre recombinase is driven by the adiponectin (Adn) promoter, which is active only in differentiated adipocytes (Fig. 3A) (Eguchi et al., 2011). Analysis of tissues from Adn-Cre×mT/mG progeny confirmed Cre activity exclusively in adipocytes, all of which were mG+ as a result of indelible lineage tracing (Fig. 3E). Although the majority of the SVF cells were mT+ as expected, mG+ lineage stromal cells in both SAT and VAT were also observed at low frequency. To test whether Adn+ lineage stromal cells are derived from adipocytes losing lipid droplets, we used a mouse cancer model, based on the notion that tumor growth induces adipocyte lipolysis (Arner and Langin, 2014; Rohm et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2012). Frequency of Adn+ lineage stromal cells was notably higher in the SVF from SAT of mice grafted with RM1 tumor cells (Fig. 3B). To exclude the possibility that pre-adipocytes are registered as the mG+ stromal cells, as a control we used 4-week-old Adn-Cre×mT/mG mice undergoing active adipogenesis. Only a background frequency (0.01%) of Adn-Cre lineage-traced cells was observed in SVF of young mice, which does not support the possibility that preadipocytes contribute to their pool (Fig. 3C). In contrast, a 30-fold higher SAT frequency and a threefold higher VAT frequency of these cells was observed for the SVF of Adn-Cre; mT/mG mice that had been pre-fed HFD to develop DIO, then switched to regular chow and grafted with tumors for 1 week (Fig. 3C). Immunofluorescence analysis of SVF from SAT of these mice demonstrated that the Adn+ lineage stromal cells express PDGFRβ (Fig. 3D). As expected, analysis of SAT sections of Adn-Cre; mT/mG mice revealed PDGFRα and PDGFRβ expression only in mG− cells (ASC) in mice raised on chow. In contrast, in obese mice bearing tumors, mG+/PDGFRβ+, as well as mG+/PDGFRα+, perivascular cells were detected (Fig. 3E), indicating expression of both PDGFRs in stromal cells derived from adipocytes. In lipolytic SAT, immunofluorescence revealed localization of perilipin 1 in a pattern consistent with its presence in lipid droplet remnants in Adn+ lineage stromal cells (Fig. 3F). Upon adipogenesis induction in culture, these mG+ adipocyte-derived stromal cells re-accumulated lipid droplets within 3 days, which is 2 days earlier than observed for mT+ adipocyte progenitors (Fig. 3G). This suggests that the adipocyte-derived stromal cells accumulating in remodeling AT are primed to quickly re-differentiate into adipocytes.

Fig. 3.

Adipocyte-derived stromal cells in remodeling SAT. (A) Scheme for lineage tracing of adiponectin (Adn)+ cells and their derivatives (mG+) among other cells (mT+). pCa, chicken actin promoter; triangle, LoxP; pA, polyadenylation site. (B) Cultured SVF from SAT of a 12-week-old Adn-Cre; mT/mG mouse pre-fed HFD to develop DIO and then grafted with RM1 tumor cells for 1 week (lipolysis induction). mG+ cells with ASC morphology emerge among mT+ cells (arrows). (C) Increased frequency of mG+ cells with ASC morphology in culture-plated SVF from SAT of Adn-Cre; mT/mG mice in which lipolysis was induced as in B, compared with untreated 4-week-old mice (control). Data are mean±s.e.m. for 10 view fields; *P<0.05 (Student's t-test). (D) Culture-plated SVF (P0) from SAT of a mouse in B were subjected to four-color anti-PDGFRβ immunofluorescence (yellow). Arrow indicates an mG+ cell with ASC morphology expressing PDGFRβ. (E) Paraffin wax-embedded sections of SAT from mice described in C subjected to PDGFRα or PDGFRβ (red) and GFP (green) immunofluorescence. Arrows indicate mG/PDGFR colocalization. (F) Paraffin wax-embedded sections of SAT of a mouse in B subjected to PLN1 (red) and GFP (green) immunofluorescence. Arrows indicate PLN1 in GFP+ stromal cells next to a blood vessel (b). a, adipocytes. (G) SVF from a mouse in B subjected to white adipogenic conditions for 3 days. The phase-contrast image indicates quick lipid droplet (arrows) accumulation in Adn+ lineage stromal cells; nuclei are blue. Scale bars: 50 μm.

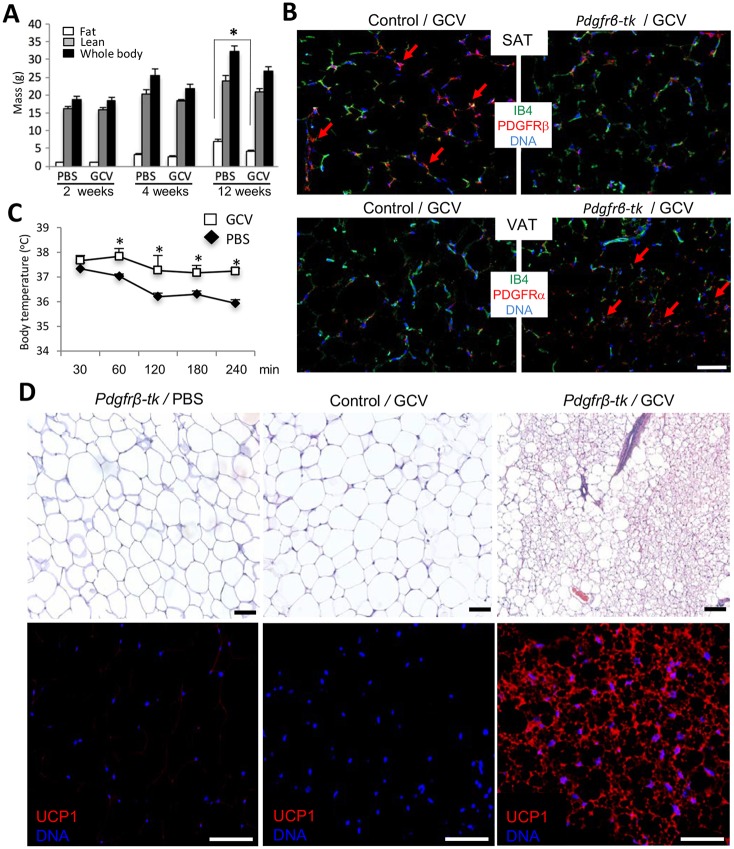

Depletion of the PDGFRβ+ lineage results in SAT and VAT beiging

To test the function of PDGFRβ+ lineage via a genetic approach, we used Pdgfrb-tk mice (Cooke et al., 2012). In this strain, thymidine kinase (tk) is expressed under the PDGFRβ promoter. In response to ganciclovir (GCV) treatment, proliferating PDGFRβ-expressing cells are depleted in these mice. We treated age-matched Pdgfrb-tk mice with increasing concentrations of GCV, or with PBS as a control, immediately after weaning and placed them on a HFD. Although fat body mass increased in control mice, which is indicative of WAT expansion, GCV-treated mice displayed a GCV dose-dependent resistance to DIO after 3 months (Fig. 4A). Immunofluorescence analysis of SAT and VAT demonstrated a reduced frequency of PDGFRβ+ cells in GCV-treated Pdgfrb-tk mice (Fig. 4B). In contrast, PDGFRα signal was increased upon PDGFRβ+ lineage depletion (Fig. 4B). We also placed GCV-treated and control Pdgfrb-tk mice into a 4°C chamber and monitored their body temperature. This experiment revealed elevated cold tolerance in PDGFRβ lineage-depleted mice (Fig. 4C). PDGFRβ+ lineage-depleted mice also had higher oxygen consumption and CO2 generation during both day and night cycles, indicating increased energy expenditure (Fig. S3A), while their food consumption was not changed (Fig. S3B). These observations suggest that either BAT or beige AT is activated upon PDGFRβ+ lineage depletion. Histological analysis and UCP1 immunofluorescence revealed a marked beiging of both SAT (Fig. 4D) and VAT (Fig. S3C) of PDGFRβ+ lineage-depleted mice, but not of control C57BL/6 mice treated with GCV. AT analysis indicates that not only WAT but also interscapular BAT depots were smaller in GCV-treated mice (Fig. S3E), likely due to decreased adipocyte size as detected by histology (Fig. S3D). Other tissues, including skeletal muscle were not noticeably affected (Fig. S3F). Combined, our results indicate that the PDGFRβ+ lineage is dispensable for beige adipogenesis in mice.

Fig. 4.

Depletion of the PDGFRβ+ lineage results in AT beiging. (A) Four-week-old Pdgfrb-tk mice (n=6/group) were injected intreperitoneally (i.p.) daily with 50 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg ganciclovir (GCV) or PBS control for 10 days. Data are fat and lean body mass measured using EchoMRI, along with whole body mass at the three time points post-treatment. (B) Paraffin wax-embedded sections of SAT from wild-type (control) and Pdgfrb-tk mice 1 month post-treatment with 100 mg/kg GCV were subjected to anti-PDGFRα or anti-PDGFRβ immunofluorescence (red) and endothelium-specific isolectin B4 (IB4) staining (green). Arrows indicate the comparatively high density of PDGFRβ+ or PDGFRα+ cells. (C) Body temperature of Pdgfrb-tk mice 1 month post GCV or PBS treatment measured over 240 min at 4°C. There is increased cold tolerance of PDGFRβ+ lineage-depleted mice. Data are mean±s.e.m. for multiple mice; *P<0.05 (Student's t-test). (D) Paraffin wax-embedded sections of SAT from Pdgfrb-tk or C57BL/6 (control) mice 1 month post-treatment with PBS (control) or 100 mg/kg GCV were subjected to Hematoxylin and Eosin staining (top) and anti-UCP1 immunofluorescence (red, bottom). Scale bars: 50 µm. Nuclei are blue. Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

PDGFRα/PDGFRβ signaling balance directs adipogenesis

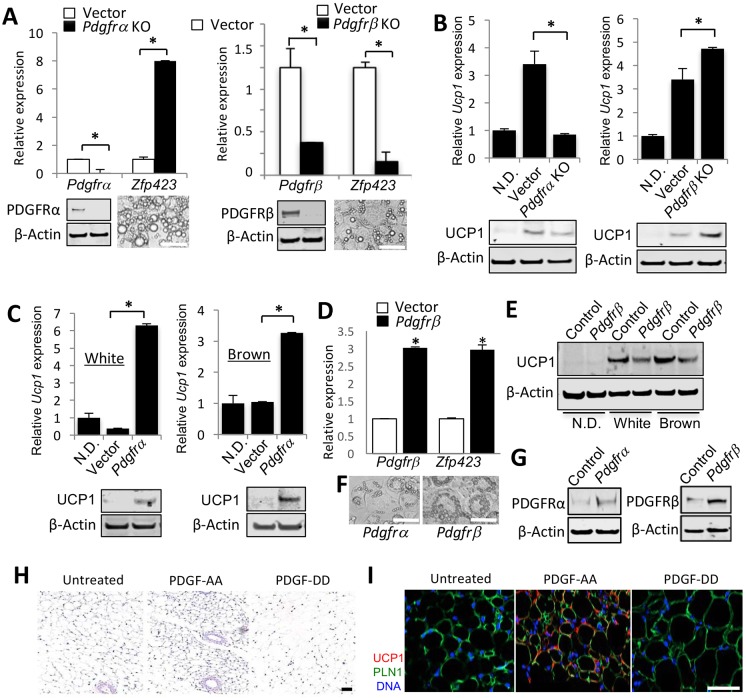

To directly test the role of PDGFR signaling in adipogenesis, we chose to use cell culture models. We used immortalized preadipocytes from mouse BAT (IBP) that spontaneously differentiate into brown adipocytes in culture (Uldry et al., 2006). We also used mouse 3T3-L1 cells commonly used as white adipocyte progenitors (Daquinag et al., 2011). By measuring mRNA levels, we observed that expression of PDGFRβ was higher than that of PDGFRα in 3T3-L1 cells, whereas in brown adipocyte progenitors, PDGFRβ expression was lower than that of PDGFRα (Fig. S4A). This suggested that the relative PDGFRα/PDGFRβ expression levels might be a determinant of subsequent white/brown adipogenesis. Consistent with previous reports indicating that continuous activity of PDGFRα and PDGFRβ prevents adipogenesis (He et al., 2015; Iwayama et al., 2015), expression of both of these genes was not detectable after 2 days of adipogenesis induction (Fig. S4B), indicating that their function is transient at the onset of differentiation. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing was used to knock out (KO) either PDGFRα or PDGFRβ in the two cell lines. Knockout efficiency was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR on differentiated adipocytes (Fig. 5A). We measured the expression of Zfp423, a gene expressed during white, but not brown, adipogenesis (Vishvanath et al., 2016), to assess the effect of PDGFR loss on the white adipogenic program. We observed that loss of PDGFRα signaling promoted white adipogenesis in brown preadipocytes, whereas loss of PDGFRβ signaling abrogated white adipogenesis (Fig. 5A). Vice versa, loss of PDGFRα signaling in brown preadipocytes suppressed the brown adipogenic program, as indicated by reduced Ucp1 expression, whereas loss of PDGFRβ signaling induced Ucp1 expression even under white adipogenesis induction culture conditions (Fig. 5B). These RT-PCR results were confirmed by UCP1 immunoblotting (Fig. 5A,B; Fig. S4C,D). In adipocytes, PDGFRα knockout reduced UCP1 protein by 1.7-fold (Fig. 5B), whereas Pdgfrb knockout enhanced UCP1 protein by 2.9-fold (Fig. 5B), and Pdgfrb ectopic expression reduced UCP1 protein by 4.5-fold (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

PDGFRα/PDGFRβ signaling balance directs adipogenesis. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Pdgfra, Pdgfrb and Zfp423 mRNA expression, normalized to 18S RNA, in immortalized brown preadipocytes with knockout (KO) of Pdgfra or Pdgfrb compared with control cells transduced with empty CRISPR/Cas9 vector. Cells were induced to undergo white adipogenesis for 8 days. Below, knockout of PDGFRα and PDGFRβ is confirmed by immunoblots with the corresponding antibody prior to adipogenesis induction. Images show differentiated Pdgfra KO and Pdgfrb KO adipocytes. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Ucp1 mRNA expression, normalized to 18S RNA, in immortalized brown preadipocytes lacking Pdgfra or Pdgfrb compared with control cells transduced with empty CRISPR/Cas9 vector. Cells were induced to undergo adipogenesis for 8 days prior to analysis. Baseline control is non-differentiated cells (N.D.). Changes in UCP1 protein expression are confirmed by immunoblotting. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Ucp1 gene expression, normalized to 18S RNA, in 3T3-L1 cells transduced with an ectopic Pdgfra expression vector or empty lentiviral vector. Cells were induced to undergo white or brown adipogenesis for 8 days prior to analysis. Baseline control is non-differentiated cells (N.D.). Changes in UCP1 protein expression are confirmed by immunoblotting. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Pdgfrb and Zfp423 gene expression, normalized to 18S RNA, in 3T3-L1 cells transduced with an ectopic Pdgfrb expression vector or empty lentiviral vector. In A-D, data are mean±s.e.m. for two qPCR reactions; *P<0.05 (Student's t-test). (E) UCP1 immunoblotting of extracts from immortalized brown preadipocytes transduced with doxycycline-inducible Pdgfrb expression lentivirus. Cells were induced to undergo white or brown adipogenesis for 8 days prior to analysis and not treated (control) or treated (Pdgfrb) with doxycycline prior to differentiation induction. Baseline control is non-differentiated cells (N.D.). (F) Images of adipocytes differentiated from 3T3-L1 cells overexpressing Pdgfrα or Pdgfrb. (G) Immunoblotting of cells from C and D prior to adipogenesis induction showing the extent of Pdgfra and Pdgfrb overexpression. In all blots, β-actin immunoblotting is a protein-loading control. (H,I) Paraffin wax-embedded sections of SAT from mice treated with PDGF-AA or PDGF-DD; control mice were injected with PBS. (H) Hematoxylin and Eosin staining reveals smaller adipocyte in PDGF-AA-treated mice. (I) Anti-UCP1 immunofluorescence/anti-perilipin 1 immunofluorescence reveals UCP1 expression in PDGF-AA-treated mice. Scale bars: 50 µm. Nuclei are blue.

We also transduced the cell lines with lentivirus constructs for doxycycline-inducible PDGFR expression (Fig. 5C-G). Ectopic expression of PDGFRα in 3T3-L1 cells resulted in increased UCP1 protein expression, which was observed not only in brown but also in white adipogenesis induction media (Fig. 5C). In contrast, ectopic expression of Pdgfrb in 3T3-L1 cells resulted in increased Zfp423 expression (Fig. 5D). Moreover, ectopic expression of PDGFRβ in brown preadipocytes suppressed UCP1 expression in both brown and white adipogenic conditions, as revealed by immunoblotting (Fig. 5E), as well as in larger lipid droplets (Fig. 5F). By using Seahorse, we demonstrated that PDGFRα overexpression and PDGFRβ knockout induce uncoupled respiration in adipocytes, confirming their beiging (Fig. S4E-G).

We also tested whether these effects can be induced by PDGFR ligands. Treatment of immortalized preadipocytes (Galmozzi et al., 2014) induced to undergo brown adipogenesis with PDGF-DD, a specific ligand of PDGFRβ, suppressed UCP1 expression (Fig. S5A). Moreover, mice treated with the PDGFRα ligand PDGF-AA displayed a reduction in fat body mass, increased cold tolerance and increased energy expenditure, the indicators of activated uncoupled thermogenesis (Fig. S5B-D). Histology demonstrated decreased adipocyte size, while immunofluorescence revealed UCP1 expression, indicating adipocyte beiging in both SAT (Fig. 5H,I) and VAT (Fig. S5E,F). Conversely, mice treated with PDGFRβ ligand PDGF-DD displayed increased adipocyte size in both SAT (Fig. 5H,I) and VAT (Fig. S5E,F), as well as decreased energy expenditure (Fig. S5D). Combined, these results indicate that PDGFRβ expression directs progenitor cells towards white adipogenesis and that PDGFRα signaling underlies AT beiging while PDGFRβ signaling counteracts it.

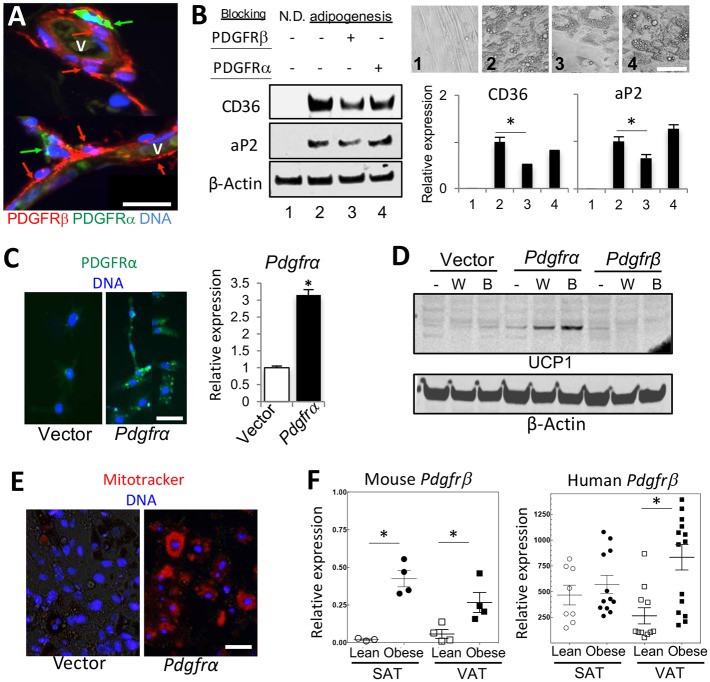

Human ASC heterogeneity and PDGFRα/PDGFRβ signaling balance

Finally, we tested whether the function of PDGFRα and PDGFRβ signaling in adipogenesis might be conserved in humans. Consistent with observations in mice (Daquinag et al., 2015), immunofluorescence on human AT identified ASCs with high levels of PDGFRβ and low levels of PDGFRα expression in the perivasculature (Fig. 6A). In contrast, ASCs with low levels of PDGFRβ and high levels of PDGFRα expression were observed in the stroma further away from the lumen (Fig. 6A). We then subjected ASCs derived from SAT of human donors to adipogenesis by incubating with antibodies that block human PDGFR signaling added during the induction of differentiation. PDGFRβ blockade delayed lipid droplet formation and reduced the expression of aP2/fabp4 and of CD36 (Fig. 6B), indicating suppression of adipogenesis. Antibody blocking human PDGFRα signaling used as a control did not have a significant effect on adipogenesis. In a reciprocal approach, we ectopically expressed human PDGFRα in 3T3-L1 cells (Fig. 6C). Consistent with observations for mouse gene ectopic expression results, human PDGFRα induced UCP1 protein expression in both brown (6.4-fold) and white (4.6-fold) adipogenesis induction conditions, whereas PDGFRβ did not (Fig. 6D). UCP1+ adipocytes also had a notably higher Mitotracker signal (Fig. 6E), further confirming that human PDGFRα signaling induces brown adipogenesis. To investigate the clinical relevance of our findings, we used RT-PCR to compare Pdgfrb expression in the SVF of lean and obese human AT donors. We observed a higher Pdgfrb expression in the SVF of obese donors, compared with lean, which was particularly the case for VAT (Fig. 6F). Analysis of AT from lean and obese mice confirmed this trend for both SAT and VAT (Fig. 6F). These observations, consistent for mouse models and human samples, suggest that PDGFRβ signaling favors white adipogenesis commitment.

Fig. 6.

Human ASC heterogeneity and PDGFRα/PDGFRβ signaling balance. (A) Paraffin wax-embedded sections of VAT from a bariatric surgery patient subjected to PDGFRα (green)/PDGFRβ (red) immunofluorescence. Mutually exclusive PDGFRβ expression is found on perivascular cells and PDGFRα expression is found on cells further away from the lumen of blood vessels (v). (B) ASCs isolated from SAT of a bariatric surgery patient were treated with a PDGFRα-blocking antibody or a PDGFRβ-blocking antibody and then either not differentiated (N.D.) or subjected to adipogenesis induction (2-4). Phase-contrast images demonstrate formation of adipocytes with smaller lipid droplets upon PDGFRβ blockade (3). Immunoblotting of cell extracts shows that PDGFRβ blocking suppresses expression of adipogenesis markers aP2 and CD36. Equal protein loading is confirmed by β-actin immunoblotting. Data are mean band intensity± s.e.m. for three samples; *P<0.05 (Student's t-test). (C) 3T3-L1 cells transduced with human PDGFRA expression vector or control lentiviral vector and subjected to PDGFRα (green) immunofluorescence. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of human PDGFR gene expression, normalized to 18S RNA are plotted. Data are mean±s.e.m. for two reactions; *P<0.05 (Student's t-test). (D) 3T3-L1 cells transduced with human PDGFRA, PDGFRB or the control lentiviral vector were induced to undergo white adipogenesis; adipocyte extracts were subjected to UCP1 immunoblotting. (E) Cells from C were induced to undergo white adipogenesis and stained with Mitotracker (red), indicating abundance of active mitochondria in adipocytes differentiated from PDGFRA-expressing 3T3-L1 cells. (F) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mouse Pdgfrb mRNA expression normalized to 18S RNA and of human PDGFRB mRNA expression, normalized to GAPDH. For mouse Pdgfrb, cDNA was prepared from samples of total SAT and VAT of mice raised for 5 months on chow (lean) or HFD (obese). For human PDGFRB, cDNA was prepared from SVF of SAT and VAT samples from lean (BMI<30) or obese (BMI>30) patients. Data are mean±s.e.m. for the multiple samples analyzed. *P<0.05 (Student's t-test). Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

DISCUSSION

The roles of progenitor cells expressing PDGFRα and PDGFRβ in AT have remained controversial. It has been reported that ASC are heterogeneous and predominantly express either PDGFRα or PDGFRβ (Lee et al., 2012). Our recent studies (Daquinag et al., 2015, 2016) confirm that PDGFRα and PDGFRβ are expressed in a semi-mutually exclusive fashion in AT, suggesting that PDGFRα/PDGFRα and PDGFRβ/PDGFRβ homodimers are the major functional receptors operating in distinct ASC subpopulations. Previous lineage-tracing experiments have shown that all adipocytes are derived from progenitors that express PDGFRα during development (Berry and Rodeheffer, 2013; Lee et al., 2012). Instead, PDGFRβ marks only a subset of progenitor cells (Tang et al., 2008; Vishvanath et al., 2016). Here, we confirm that PDGFRβ+ cells serve as adipocyte progenitors with an increased propensity to make white adipocytes and do not significantly contribute to the pool of beige adipocytes. The main conclusion from our study is that in both mice and humans, the balance between PDGFRα and PDGFRβ signaling in adipocyte progenitors predetermines their commitment to beige or white adipogenesis.

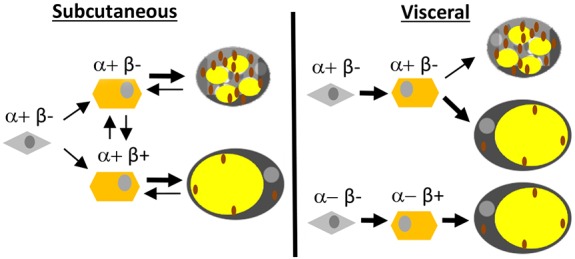

Our data indicate that PDGFRα expression precedes ASC differentiation into beige adipocytes, whereas PDGFRβ induction and PDGFRα suppression in states of low sympathetic tone underlie the shift towards white adipogenesis. The increased PDGFRβ and decreased PDGFRα signaling appears to be a requisite for AT hypertrophy and hyperplasia, which at least in part depends on the PDGFRβ+ cell lineage. Another important conclusion from our study is that adipocytes in SAT and VAT are maintained by different lineages of ASC that have distinct differentiation capacities, which is depicted in our working model (Fig. 7). In SAT, all preadipocytes are derived from the PDGFRα+ lineage and can drift from beige to white progenitor state as a function of PDGFRβ expression. Moreover, under lipolytic conditions, SAT adipocytes can transiently re-acquire lipid-free ASC morphology. In contrast, not all adipocytes are derived from the PDGFRα+ lineage and display such plasticity in VAT. A fraction of VAT progenitors never expresses PDGFRα and only expresses PDGFRβ. Our observations provide an explanation for the reduced ability of VAT to undergo beiging, and its distinct pathophysiological features. We show that in standard housing conditions Pdgfrb+ lineage adipocytes arise in SAT and VAT after 6 weeks of age coincidently with WAT expansion. The signal inducing this switch may be a decrease in the sympathetic tone, as suggested by our data that PDGFRβ+ lineage recruitment can be advanced by thermoneutrality. Interestingly, compared with VAT, SAT was found to mount higher PDGFRβ+ lineage adipocyte recruitment in response to both warm housing temperature and HFD feeding. Our results are consistent with studies concluding that adipocytes in VAT and SAT have different developmental origins (Berry et al., 2016; Chau et al., 2014) and reporting a particular plasticity of SAT (Joe et al., 2009; Rosenwald et al., 2013).

Fig. 7.

A model of SAT and VAT adipocyte lineage specification. In SAT, all progenitor cells (gray) are of the PDGFRα+ lineage and give rise to PDGFRβ− and PDGFRβ+ preadipocytes (orange) that can differentiate into beige adipocytes rich in mitochondria (brown) or unilocular white adipocytes. SAT adipocytes can transiently acquire lipid-free ASC morphology and drift from mitochondria-rich beige to white as a function of PDGFRβ expression in de-differentiated preadipocytes. In VAT, some adipocytes are also derived from the PDGFRα+ progenitor lineage without PDGFRβ expression in preadipocytes, whereas other adipocytes are derived from a distinct PDGFRα-negative progenitor cells expressing only PDGFRβ.

Our conclusions, based in part on the analysis of cells with prior and present expression of Pdgfrb-Cre, are largely in agreement with the results recently reported for the doxycycline-inducible Pdgfrb-Cre mouse strain (Vishvanath et al., 2016). The only inconsistency is that Vishvanath et al. did not observe a significant DIO-induced recruitment of PDGFRβ+ progenitors in SAT in their study, in which HFD feeding was performed in older mice. Interestingly, in our study, SAT Pdgfrb+ lineage adipogenesis activation was also not observed in older mice fed HFD (Fig. S2B,C). These observations suggest that induction of Pdgfrb+ lineage adipogenesis by HFD feeding in SAT, effective in neonatal development, is a transient process. A caveat with the distinct available mouse strains expressing Cre from the Pdgfrb promoter is a possibility of deviation of Cre expression from the endogenous Pdgfrb expression pattern. A distinct mouse strain (Foo et al., 2006) originally used for constitutively active Pdgfrb lineage tracing in development revealed SAT staining at P30, although no signal in adipocytes was specifically shown (Tang et al., 2008). However, that Pdgfrb-Cre mouse strain (Foo et al., 2006) induces Cre expression in hematopoietic and endothelial cells in addition to mesenchymal cells (Guimaraes-Camboa et al., 2017; Hong et al., 2015) and, therefore, does not label the Pdgfrb lineage specifically. Our study is based on an independently generated Pdgfrb-Cre strain in which Cre is activated specifically in perivascular cells (Cuttler et al., 2011), consistent with Pdgfrb expression pattern we had reported (Daquinag et al., 2011). Here, we clearly show that, in this strain, neither PDGFRβ nor Cre are expressed in hematopoietic cells, or endothelial cells. Our analysis indicates that the majority of perivascular AT cells express Cre in this strain, arguing against a possibility of incomplete penetrance. Nevertheless, differences in the efficiency of Cre expression for the distinct reported Pdgfrb-Cre lines could account for the subtle discrepancies in reported results.

We show that expression of PDGFR genes is downregulated during adipogenesis induction (Fig. S4B), suggesting that their function is transient at the onset of differentiation. Consistent with this observation, Pdgfrb-Cre lineage-tracing experiments indicate that during the first 6 weeks of postnatal development, Cre is expressed only in stromal cells but not in adipocytes, which become lineage traced only by week 8. Thus, the increase in frequency of Pdgfrb+ lineage adipocytes during DIO development should be largely due to new progenitor recruitment. In agreement with our conclusions, the previous inducible Pdgfrb-Cre lineage-tracing study also showed that Pdgfrb-Cre induction in pre-existing adipocytes does not take place (Vishvanath et al., 2016). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that Pdgfrb/Cre might be induced in a fraction of pre-existing adipocytes in our constitutive model. This is particularly an issue in light of the ability of adipocytes to lose lipid droplets and revert to the ASC morphology, which we discovered.

This study reinforces our previous report, in which we pharmacologically targeted PDGFRβ+ ASCs in mice and concluded that surviving PDGFRα+ ASCs were responsible for AT beiging (Daquinag et al., 2015). The conclusions of that study could have been confounded by unknown off-target effects of the agent used. Here, we confirm that depletion of the PDGFRβ+ cell lineage in the Pdgfrb-tk/GCV model induces beiging of SAT, as well as of VAT. The GCV-activated tk suicide gene specifically targets proliferating cells. Consistent with an expectation that proliferation of PDGFRβ+ cells should be infrequent outside AT in adulthood, effects outside tumors were not observed in the original study (Cooke et al., 2012). We confirmed that PDGFRβ+ ASC proliferate by Ki67 immunofluorescence, as well as by demonstrating EdU incorporation into ASC nuclei upon injection into Pdgfrb-Cre; mTmG mice, which was promoted by HFD pre-feeding (data not shown). GCV treatment had no effect on skeletal muscle and other adult organs in Pdgfrb-tk mice. Therefore, it is likely that the beiging phenotype we observed is directly due to depletion of Pdgfrb+ stromal cells. However, we do not exclude a possibility that depletion of PDGFRβ+ cells in BAT contributes to it. Future studies could establish the extent to which PDGFRβ+ lineage adipocyte generation relies on progenitor cell proliferation and new preadipocyte recruitment observed previously, as opposed to beige/white conversion of existing adipocytes (Berry et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2013). Engagement of these alternative mechanisms of AT remodeling appears to be depot specific and a function of age (Kim et al., 2014; Sanchez-Gurmaches and Guertin, 2014; Wang et al., 2013). Results of our Adn-Cre lineage-tracing experiments indicating that adipocytes can lose lipid droplets and acquire preadipocyte properties are consistent with the recent reports on embryonic adipocyte plasticity (Hong et al., 2015) and adipocyte-myofibroblast transition reported in skin fibrosis models (Marangoni et al., 2015). As we show, the frequency of adipocyte dedifferentiation appears to be low and its physiological significance is unclear. We had previously discovered that, in obesity, ASCs become systemically mobilized in human disease (Zhang et al., 2016). Moreover, ASCs are recruited by tumors, differentiate into tumor-infiltrating fibroblasts and adipocytes, and promote cancer progression (Zhang et al., 2016). We have reported that both PDGFRβ-high and PDGFRβ-low ASCs become recruited from WAT by tumors (Daquinag et al., 2016). It remains to be determined what roles these distinct populations of migratory ASCs, some of which may be derived from adipocytes, serve in other pathological settings.

Our cell culture experiments indicate that, at early stages of preadipocyte lineage specification, PDGFRβ signaling favors white adipogenesis, whereas PDGFRα signaling favors brown adipogenesis. Importantly, we observed that UCP1 expression could be turned on or off by PDGFR signaling modulation, irrespective of brown adipogenesis inducers in culture. This indicates that the PDGFRα/PDGFRβ switch is downstream of β3-adrenoceptor signaling induction. Furthermore, our data suggest that PDGFRβ expression in AT may serve as an indicator of its white/beige adipogenesis balance. Consistent with our conclusions, treatment of mice with PDGFR inhibitor imatinib results in WAT repopulation with smaller adipocytes, which the authors of the study attributed to PDGFRβ inhibition (Jiang et al., 2017).

In situ PDGFR signaling is regulated by local concentrations of the ligands, PDGF-A, PDGF-B, PDGF-C and PDGF-D, which form homo- and heterodimers with different receptor selectivity (Seki et al., 2016). Our results indicate that PDGFs are contained in FBS at concentrations sufficient for receptor activation. Indeed, changing relative PDGFRα/PDGFRβ expression levels was sufficient to change progenitor cell fate without ligand addition. However, treatment of immortalized preadipocytes induced to undergo brown adipogenesis with PDGFD (specific for PDGFRβ) suppressed UCP1 expression (Fig. S4E), indicating ligand importance.

Transcription programs downstream of PDGFRα and PDGFRβ signaling remain incompletely understood. The details of extracellular cues that mediate activation of the signal transduction cascades relying on PDGFRα and PDGFRβ remain to be further investigated. It should be noted that sustained constitutive activation of PDGFRα or PDGFRβ actually suppresses adipogenesis (He et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2017). Instead, in our study modest PDGFRα and PDGFRβ overexpression was transient and merely skewed the adipogenic differentiation towards white or beige, rather than blocking it. Together, our data demonstrate that the ratio of PDGFRα/PDGFRβ signaling in adipocyte progenitors directs adipogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects

The clinical protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board. For each subject, the body mass index (BMI; kg m−2) was calculated; obese was defined as BMI ≥30, lean as BMI<30. For PDGFRα/PDGFRβ immunofluorescence, SAT and VAT from healthy bariatric surgery patients (IRB protocol HSC-MS-14-0514) were used. For PDGFRB gene expression analysis, we used cDNA from WAT samples of prostate cancer patients described previously (Zhang et al., 2016). Freshly isolated (not-plated) SVF from abdominal SAT and periprostatic AT (VAT) was used for mRNA extraction and cDNA isolation.

Mouse experiments

All animal experimentations complied with protocols approved by the University of Texas Health Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed in the animal facility with a 12 h light/dark cycle and regulated temperature (22-24°C) unless indicated otherwise. Animals had free access to water and diet. The reporter mT/mG (stock 007676), Pdgfrα-Cre (stock 013148) and Adiponectin-CRE (stock 010803) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. The Pdgfrb-Cre and Pdgfrb-tk strains have been described previously (Cooke et al., 2012; Cuttler et al., 2011). To avoid strain-specific variations, both strains were back-crossed into the C57BL/6 background (eight generations). For DIO induction, mice were fed 58 kcal% (fat) diet (Research Diets, D12331). For Pdgfrb-tk cell depletion, mice were injected (intraperitoneally, i.p.) daily with 50 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg body weight of ganciclovir (Sigma, G2536, stock diluted with saline to 10 mg/ml) for 10 days starting at 4 weeks of age; mice injected with PBS were used as a baseline control. CL 316,243 was injected i.p. at the dose of 1 mg/kg daily for 5 days (Lee et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013). PDGF-AA (R&D, 221-AA) and PDGF-DD (R&D, 1159-SB/CF) were injected daily subcutaneously (s.c.) (lower back) into 6-week-old C57BL/6 females at a dose of 10 ng/mouse/day and mice were analyzed 7 days after the last injection. Body composition was measured using EchoMRI-100T (Echo Medical Systems). Indirect calorimetry studies were performed with OXYMAX (Columbus Instruments) Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS) as described previously (Daquinag et al., 2015). The core body temperature was determined using a MicroTherma 2K High Precision Type K Thermocouple Meter (THS-221-092, ThermoWorks)/RET-3 rectal probe (Braintree Scientific) as described previously (Daquinag et al., 2015). The environmental chamber IS33SD (Powers Scientific) was used. For thermoneutrality, animals were housed at 26°C for 1 day and then at 30°C for additional 7 days. For prolonged cold exposure, acclimation was performed for the first 4 days: temperature was decreased to 16°C on day 1, 10°C on day 2, 6°C on day 3 and 4°C on days 4-8.

Fluorescence microscopy

Inguinal AT was analyzed as SAT, gonadal AT was analyzed as VAT. AT cell suspensions were isolated as described previously (Daquinag et al., 2011). Briefly, minced AT was digested in 0.5 mg/ml collagenase type I (Worthington Biochemical) and 2.5 mg/ml of dispase (Roche, 04942078001) solution under gentle agitation for 1 h at 37°C and centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min to separate the SVF pellet from the adipocytes. Paraformaldehyde-fixed cells and formalin-fixed paraffin wax-embedded tissue sections were analyzed by immunofluorescence as described previously (Daquinag et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2016). Whole mounts of AT were prepared and analyzed as described previously (Azhdarinia et al., 2013). Upon blocking, primary (4°C, 12 h) and secondary (room temperature, 1 h) antibody incubations were carried out. Antibodies, diluted in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20, were as follows: anti-GFP (Gene Tex, GTX26673; 1:250); anti-RFP (Abcam, ab34771; 1:200); anti- UCP1 (Alpha Diagnostic, UCP-11A; 1:400); anti-CD31 (Santa-Cruz, sc-1506; 1:75); anti-F4/80 (Abcam, ab16911; 1:50); anti-perilipin (Cell Signaling, 3470; 1:100); anti-CD45 (eBioscience, 16-0451-85; 1:50); anti-PDGFRα (Abcam, ab51875; 1:100); anti-PDGFRβ (Abcam, ab32570; 1:100). Donkey Alexa 488-conjugated (1:200) IgG, Cy3-conjugated (1:300) IgG, streptavidin-Cy3 (1:200) and streptavidin-Cy5 (1:200) were from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Isolectin B4 (Vector, B-1205; 1:2000) and MitoTracker Deep Red (Molecular Probes, M22426; 0.02 mM) were used. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen, H3569) or DRAQ5 (Cell Signaling, 4084). Images were acquired with a confocal Leica TCS SP5 microscope/LAS AF software (Leica) or Carl Zeiss upright Apotome Axio Imager Z1/ZEN2 Core Imaging software. mG+ adipocyte percentage was determined using NIH ImageJ software by cell counts in 10 separate 10× fields. Amira 5.4 software (VSG) was used for data capture and analysis.

Plasmids

The Tet-On 3G tetracycline-inducible gene expression system was used for overexpression of Pdgfra or Pdgfrb by cloning mouse Pdgfra or Pdgfrb cDNA (He et al., 2015; Iwayama et al., 2015) into plasmid pLVX-TRE3G to generate the pLenti-Pdgfra or pLenti-Pdgfrb. The regulator plasmid pLVX-Tet3G and the response plasmid pLVX-TRE3G harboring full-length mouse Pdgfra or mouse Pdgfrb cDNAs were transfected into Lenti-X293T cells to generate lentivirus according to the manufacturer's protocol (Clontech). To construct pLenti-CRISPR/Cas9 Pdgfra or Pdgfrb gRNA expression vectors, each 20 bp target sequence was subcloned into lenti-CRISPR v2 plasmid (Addgene, 52961). The CRISPR/Cas9 target sequences, 20 bp target and 3 bp PAM sequence used in this study were: mouse Pdgfra 5′-CGATATCCTGGGCGTCGGGTAGG-3′; mouse Pdgfrb 5′- TCCAGTCCCCGTCCGTGTGCTGG-3′. Human PDGFRα (Plasmid 23892) and PDGFRβ (Plasmid 23893) were from Addgene.

Cell culture

The two IBP cell lines (Galmozzi et al., 2014; Uldry et al., 2006), RM1 cells (Zhang et al., 2016) and authenticated 3T3-L1 cells from American Type Tissue Collection (ATCC) were tested for contamination. Cells were grown in DMEM/10% FBS. For transduction, plasmids were transfected into Lenti-X293T cells with packing vector in 10 cm plates using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11668019). Virus supernatants were collected 48 h post transfection, filtered through a 0.45 µm filter and concentrated with the Lenti-X concentrator (TakaRa Clontech, 631231). Viral infection was performed in medium containing 8 μg/ml polybrene in six-well plates for 12 h. Selection with 10 μg/ml puromycin and 200 μg/ml G418 was performed for 10 days. Cells were plated in eight-well chamber slides (Thermo Fisher, 154941). For white adipogenesis induction, cells grown to confluence were cultured in medium containing 1.7 µM insulin/0.5 mM IBMX, 1 μM dexamethasone/0.2 μM indomethacin for 3 days and 1.7 µM insulin afterwards, as described previously (Daquinag et al., 2011). For brown adipogenesis induction, cells grown to confluence were cultured in medium containing 50 nM insulin/0.5 mM IBMX, 1 μM dexamethasone, 1 nM 3,5,3′-Triiodothyronine (T3) and 5 μM rosiglitazone for 3 days, and 50 nM insulin with 1 nM T3 afterwards. Human ASCs isolated from SAT of a bariatric surgery patients were treated with a PDGFRα-blocking antibody (R&D,MAB322) or a PDGFRβ-blocking antibody (R&D, AF385) at a dose of 40 μg/ml in inducing medium and then subjected to adipogenesis induction as described previously (Tseng et al., 2008).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the Trizol Reagent (Life Technologies, 15596018). Complementary DNAs were generated using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, 4368814). PCR reactions were performed on a CFX96 Real-Time System C1000 Touch thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) using Q-PCR Master Mix (Gendepot, Q5600-005). Expression of mouse Pdgfra, Pdgfrb, Ucp1 and Zfp423 was normalized to 18S RNA. Expression of human Pdgfra and Pdgfrb was normalized to human Gapdh. The Sybr green primers are as follows: human PDGFRA, 5′-GGTCTTGGAAGTGAGCAGT-3′ and 5′-ACATCTGGGTCTGGCACATA-3′, human PDGFRB, 5′-GTGCTCACCATCATCTCCCT-3′ and 5′-ACTCAATCACCTTCCATCGG-3′; human GAPDH, 5′- CGACCACTTTGTCAAGCTCA-3′ and 5′-AGGGGTCTACATGGCAACTG-3′; mouse Pdgfra, 5′-CAAACCCTGAGACCACAATG-3′ and 5′-TCCCCCAACAGTAACCCAAG-3′, mouse Pdgfrb, 5′-TGCCTCAGCCAAATGTCACC-3′ and 5′-TGCTCACCACCTCGTATTCC-3′; mouse Zfp423, 5′-CAGGCCCACAAGAAGAACAAG-3′ and 5′-GTATCCTCGCAGTAGTCGCACA-3′, Ucp1, 5′-TCTCAGCCGGCTTAATGACTG-3′ and 5′-GGCTTGCATTCTGACCTTCAC-3′; and 18S RNA, 5′-AAGTCCCTGCCCTTTGTACACA-3′ and 5′-GATCCGAGGGCCTCACTAAAC-3′.

Western blotting

The whole-cell lysate was prepared in a lysis buffer and analyzed as described previously (Tseng et al., 2008). The following antibodies were used: anti-UCP1 (Sigma, U6382; 1:5000), anti-FABP4 (aP2) (Cell Signaling, 2120; 1:1000), anti-CD36 (Thermo Scientific, PA1-168; 1: 5000), anti-PDGFRα (Cell Signaling, 3174; 1:5000), anti-PDGFRβ (Abcam, ab32570; 1:5000) and anti-β-actin (Abcam, ab8226; 1:5000). The signal was detected using the Odyssey CLx imaging system (LI-COR).

Flow cytometry

The SVF pellet was treated with red blood cell lysis buffer and sequentially filtered through 70 and 40 μm cell strainers before staining with anti-PDGFRα-PE conjugate antibody at 1:100 (BioLegend, 135905) along with the isotype IgG control (BD Bioscience). Following antibody incubation, samples were washed, centrifuged at 400 g for 3 min and analyzed with FACS Aria as described previously (Daquinag et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). Data analysis was performed using FLowJo software.

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel was used to plot data as mean±s.e.m. and to calculate P-values using homoscedastic Student's t-test. P<0.05 was considered significant. All experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ali Dadbin, Chieh Tseng, Tao Zhang and Angielyn Rivera for technical help. We thank Volkhard Lindner for PDGFRβ-Cre mice and Ragu Kalluri for PDGFRβ-TK mice. We thank Aleix Ribas Latre and Kristin Mahan for providing mRNA from adipose tissue of lean and obese mice. We thank Erik Wilson and Philip Orlander for help with obtaining patient adipose tissue samples. We thank Lorin Olson for providing PDGFRα and PDGFRβ plasmids; Jiandie Lin and Shingo Kajimura for providing IBP cell lines; and Timothy Thompson for providing RM1 cells. We thank Kai Sun for many helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M.G.K.; Methodology: Z.G., A.C.D., F.S.; Validation: Z.G., A.C.D.; Formal analysis: Z.G., A.C.D., M.G.K.; Investigation: Z.G., F.S.; Resources: B.S., M.G.K.; Data curation: Z.G., A.C.D.; Writing - original draft: M.G.K.; Writing - review & editing: B.S., M.G.K.; Visualization: Z.G., A.C.D., B.S., M.G.K.; Supervision: M.G.K.; Project administration: M.G.K.; Funding acquisition: M.G.K.

Funding

This research was supported by the Harry E. Bovay, Jr Foundation and, in part, by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 TR000371).

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.155861.supplemental

References

- Arner P. and Langin D. (2014). Lipolysis in lipid turnover, cancer cachexia, and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 25, 255-262. 10.1016/j.tem.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhdarinia A., Daquinag A. C., Tseng C., Ghosh S., Amaya-Manzanares F., Sevick-Muraca E. and Kolonin M. G. (2013). A peptide probe for targeted brown adipose tissue imaging. Nature Comm. 4, 2472-2482. 10.1038/ncomms3472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry R. and Rodeheffer M. S. (2013). Characterization of the adipocyte cellular lineage in vivo. Nature Cell Biol. 15, 302-308. 10.1038/ncb2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry R., Jeffery E. and Rodeheffer M. S. (2014). Weighing in on adipocyte precursors. Cell Metab. 19, 8-20. 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D. C., Jiang Y. and Graff J. M. (2016). Emerging roles of adipose progenitor cells in tissue development, homeostasis, expansion and thermogenesis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 27, 574-585. 10.1016/j.tem.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon B. and Nedergaard J. (2004). Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol. Rev. 84, 277-359. 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau Y.-Y., Bandiera R., Serrels A., Martinez-Estrada O. M., Qing W., Lee M., Slight J., Thornburn A., Berry R., McHaffie S. et al. (2014). Visceral and subcutaneous fat have different origins and evidence supports a mesothelial source. Nat. Cell. Biol. 16, 367-375. 10.1038/ncb2922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinti S. (2009). Transdifferentiation properties of adipocytes in the Adipose Organ. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 297, 977-986. 10.1152/ajpendo.00183.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke V. G., LeBleu V. S., Keskin D., Khan Z., O'Connell J. T., Teng Y., Duncan M. B., Xie L., Maeda G., Vong S. et al. (2012). Pericyte depletion results in hypoxia-associated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis mediated by met signaling pathway. Cancer Cell 21, 66-81. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttler A. S., LeClair R. J., Stohn J. P., Wang Q., Sorenson C. M., Liaw L. and Lindner V. (2011). Characterization of Pdgfrb-Cre transgenic mice reveals reduction of ROSA26 reporter activity in remodeling arteries. Genesis 49, 673-680. 10.1002/dvg.20769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daquinag A. C., Zhang Y., Amaya-Manzanares F., Simmons P. J. and Kolonin M. G. (2011). An isoform of decorin is a resistin receptor on the surface of adipose progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell 9, 74-86. 10.1016/j.stem.2011.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daquinag A. C., Salameh A., Zhang Y., Tong Q. and Kolonin M. G. (2015). Depletion of white adipocyte progenitors induces beige adipocyte differentiation and suppresses obesity development. Cell Death Diff. 22, 351-363. 10.1038/cdd.2014.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daquinag A. C., Tseng C., Zhang Y., Amaya-Manzanares F., Florez F., Dadbin A., Zhang T. and Kolonin M. G. (2016). Targeted pro-apoptotic peptides depleting adipose stromal cells inhibit tumor growth. Mol. Ther. 24, 34-40. 10.1038/mt.2015.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi J., Wang X., Yu S., Kershaw E. E., Chiu P. C., Dushay J., Estall J. L., Klein U., Maratos-Flier E. and Rosen E. D. (2011). Transcriptional control of adipose lipid handling by IRF4. Cell Metab. 13, 249-259. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo S. S., Turner C. J., Adams S., Compagni A., Aubyn D., Kogata N., Lindblom P., Shani M., Zicha D. and Adams R. H. (2006). Ephrin-B2 controls cell motility and adhesion during blood-vessel-wall assembly. Cell 124, 161-173. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmozzi A., Sonne S. B., Altshuler-Keylin S., Hasegawa Y., Shinoda K., Luijten I. H., Chang J. W., Sharp L. Z., Cravatt B. F., Saez E. et al. (2014). ThermoMouse: an in vivo model to identify modulators of UCP1 expression in brown adipose tissue. Cell Rep. 9, 1584-1593. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães-Camboa N., Cattaneo P., Sun Y., Moore-Morris T., Gu Y., Dalton N. D., Rockenstein E., Masliah E., Peterson K. L., Stallcup W. B. et al. (2017). Pericytes of multiple organs do not behave as mesenchymal stem cells in vivo. Cell Stem Cell 20, 345-359. 10.1016/j.stem.2016.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C., Medley S. C., Hu T., Hinsdale M. E., Lupu F., Virmani R. and Olson L. E. (2015). PDGFRbeta signalling regulates local inflammation and synergizes with hypercholesterolaemia to promote atherosclerosis. Nature Comm. 6, 7770 10.1038/ncomms8770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch R. V. and Soriano P. (2003). Roles of PDGF in animal development. Development 130, 4769-4784. 10.1242/dev.00721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K. Y., Bae H., Park I., Park D.-Y., Kim K. H., Kubota Y., Cho E. S., Kim H., Adams R. H., Yoo O. J. et al. (2015). Perilipin+ embryonic preadipocytes actively proliferate along growing vasculatures for adipose expansion. Development 142, 2623-2632. 10.1242/dev.125336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwayama T., Steele C., Yao L., Dozmorov M. G., Karamichos D., Wren J. D. and Olson L. E. (2015). PDGFRalpha signaling drives adipose tissue fibrosis by targeting progenitor cell plasticity. Genes Dev. 29, 1106-1119. 10.1101/gad.260554.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Berry D. C., Jo A., Tang W., Arpke R. W., Kyba M. and Graff J. M. (2017). A PPARgamma transcriptional cascade directs adipose progenitor cell-niche interaction and niche expansion. Nat. Commun. 8, 15926 10.1038/ncomms15926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe A. W. B., Yi L., Even Y., Vogl A. W. and Rossi F. M. (2009). Depot-specific differences in adipogenic progenitor abundance and proliferative response to high-fat diet. Stem Cells 27, 2563-2570. 10.1002/stem.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimura S., Spiegelman B. M. and Seale P. (2015). Brown and beige fat: physiological roles beyond heat generation. Cell Metab. 22, 546-559. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. M., Lun M., Wang M., Senyo S. E., Guillermier C., Patwari P. and Steinhauser M. L. (2014). Loss of white adipose hyperplastic potential is associated with enhanced susceptibility to insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 20, 1049-1058. 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kras K. M., Hausman D. B., Hausman G. J. and Martin R. J. (1999). Adipocyte development is dependent upon stem cell recruitment and proliferation of preadipocytes. Obes. Res. 7, 491-447 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.-H., Petkova A. P., Mottillo E. P. and Granneman J. G. (2012). In vivo identification of bipotential adipocyte progenitors recruited by beta3-adrenoceptor activation and high-fat feeding. Cell Metab. 15, 480-491. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. H., Petkova A. P., Konkar A. A. and Granneman J. G. (2015). Cellular origins of cold-induced brown adipocytes in adult mice. FASEB J . 29, 286-299. 10.1096/fj.14-263038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell B. B., S-Susulic V., Hamann A., Lawitts J. A., Himms-Hagen J., Boyer B. B., Kozak L. P. and Flier J. S. (1993). Development of obesity in transgenic mice after genetic ablation of brown adipose tissue. Nature 366, 740-742. 10.1038/366740a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marangoni R. G., Korman B. D., Wei J., Wood T. A., Graham L. V., Whitfield M. L., Scherer P. E., Tourtellotte W. G. and Varga J. (2015). Myofibroblasts in murine cutaneous fibrosis originate from adiponectin-positive intradermal progenitors. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 1062-1073. 10.1002/art.38990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar M. D., Tasic B., Miyamichi K., Li L. and Luo L. (2007). A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45, 593-605. 10.1002/dvg.20335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L., Cook W. S., Ravazzola M., Wang M. Y., Park B. H., Montesano R. and Unger R. H. (2004). Rapid transformation of white adipocytes into fat-oxidizing machines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2058-2063. 10.1073/pnas.0308258100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter C., Herndon D. N., Chondronikola M., Daquinag A. C., Kolonin M. G. and Sidossis L. S. (2016). Human supraclavicular brown adipose tissue mitochondria have comparable UCP1 function to those found in murine intrascapular brown adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 24, 246-255. 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravussin Y., Xiao C., Gavrilova O. and Reitman M. L. (2014). Effect of intermittent cold exposure on brown fat activation, obesity, and energy homeostasis in mice. PloS ONE 9, e85876 10.1371/journal.pone.0085876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodeheffer M. S., Birsoy K. and Friedman J. M. (2008). Identification of white adipocyte progenitor cells in vivo. Cell 135, 240-249. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohm M., Schäfer M., Laurent V., Üstünel B. E., Niopek K., Algire C., Hautzinger O., Sijmonsma T. P., Zota A., Medrikova D. et al. (2016). An AMP-activated protein kinase-stabilizing peptide ameliorates adipose tissue wasting in cancer cachexia in mice. Nat. Med. 22, 1120-1130. 10.1038/nm.4171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen E. D. and Spiegelman B. M. (2014). What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell 156, 20-44. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwald M., Perdikari A., Rülicke T. and Wolfrum C. (2013). Bi-directional interconversion of brite and white adipocytes. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 659-667. 10.1038/ncb2740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gurmaches J. and Guertin D. A. (2014). Adipocyte lineages: tracing back the origins of fat. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1842, 340-351. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale P., Bjork B., Yang W., Kajimura S., Chin S., Kuang S., Scime A., Devarakonda S., Conroe H. M., Erdjument-Bromage H. et al. (2008). PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature 454, 961-967. 10.1038/nature07182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T., Hosaka K., Lim S., Fischer C., Honek J., Yang Y., Andersson P., Nakamura M., Näslund E., Ylä-Herttuala S. et al. (2016). Endothelial PDGF-CC regulates angiogenesis-dependent thermogenesis in beige fat. Nat. Commun. 7, 12152 10.1038/ncomms12152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun K., Kusminski C. M. and Scherer P. E. (2011). Adipose tissue remodeling and obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2094-2101. 10.1172/JCI45887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Berry W. L. and Olson L. E. (2017). PDGFRalpha controls the balance of stromal and adipogenic cells during adipose tissue organogenesis. Development 144, 83-94. 10.1242/dev.135962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W., Zeve D., Suh J. M., Bosnakovski D., Kyba M., Hammer R. E., Tallquist M. D. and Graff J. M. (2008). White fat progenitor cells reside in the adipose vasculature. Science 322, 583-586. 10.1126/science.1156232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traktuev D., Merfeld-Clauss S., Li J., Kolonin M., Arap W., Pasqualini R., Johnstone B. H. and March K. L. (2008). A Population of multipotent CD34-positive adipose stromal cells share pericyte and mesenchymal surface markers, reside in a periendothelial location, and stabilize endothelial networks. Circ. Res. 102, 77-85. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.159475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng Y.-H., Kokkotou E., Schulz T. J., Huang T. L., Winnay J. N., Taniguchi C. M., Tran T. T., Suzuki R., Espinoza D. O., Yamamoto Y. et al. (2008). New role of bone morphogenetic protein 7 in brown adipogenesis and energy expenditure. Nature 454, 1000-1004. 10.1038/nature07221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng Y.-H., Cypess A. M. and Kahn C. R. (2010). Cellular bioenergetics as a target for obesity therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 465-482. 10.1038/nrd3138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turley S. J., Cremasco V. and Astarita J. L. (2015). Immunological hallmarks of stromal cells in the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 669-682. 10.1038/nri3902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uldry M., Yang W., St-Pierre J., Lin J., Seale P. and Spiegelman B. M. (2006). Complementary action of the PGC-1 coactivators in mitochondrial biogenesis and brown fat differentiation. Cell Metab. 3, 333-341. 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishvanath L., MacPherson K. A., Hepler C., Wang Q. A., Shao M., Spurgin S. B., Wang M. Y., Kusminski C. M., Morley T. S. and Gupta R. K. (2016). Pdgfrbeta mural preadipocytes contribute to adipocyte hyperplasia induced by high-fat-diet feeding and prolonged cold exposure in adult mice. Cell Metab. 23, 350-359. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. A., Tao C., Gupta R. K. and Scherer P. E. (2013). Tracking adipogenesis during white adipose tissue development, expansion and regeneration. Nat. Med. 19, 1338-1344. 10.1038/nm.3324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Y., Attane C., Milhas D., Dirat B., Dauvillier S., Guerard A., Gilhodes J., Lazar I., Alet N., Laurent V. et al. (2017). Mammary adipocytes stimulate breast cancer invasion through metabolic remodeling of tumor cells. JCI Insight 2, e87489 10.1172/jci.insight.87489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S., Zan L., Hausman G. J., Rasmussen T. P., Bergen W. G. and Dodson M. V. (2013). Dedifferentiated adipocyte-derived progeny cells (DFAT cells): potential stem cells of adipose tissue. Adipocyte 2, 122-127. 10.4161/adip.23784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Boström P., Sparks L. M., Ye L., Choi J. H., Giang A.-H., Khandekar M., Virtanen K. A., Nuutila P., Schaart G. et al. (2012). Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell 150, 366-376. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Daquinag A. C., Amaya-Manzanares F., Sirin O., Tseng C. and Kolonin M. G. (2012). Stromal progenitor cells from endogenous adipose tissue contribute to pericytes and adipocytes that populate the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 72, 5198-5208. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Tseng C., Zhang Y., Sirin O., Corn P. G., Li-Ning-Tapia E. M., Troncoso P., Davis J., Pettaway C., Ward J. et al. (2016). CXCL1 mediates obesity-associated adipose stromal cell trafficking and function in the tumor microenvironment. Nature Comm. 7, 11674 10.1038/ncomms11674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]