Abstract

The level of stem cell proliferation must be tightly controlled for proper development and tissue homeostasis. Multiple levels of gene regulation are often employed to regulate stem cell proliferation to ensure that the amount of proliferation is aligned with the needs of the tissue. Here we focus on proteasome-mediated protein degradation as a means of regulating the activities of proteins involved in controlling the stem cell proliferative fate in the C. elegans germ line. We identify five potential E3 ubiquitin ligases, including the RFP-1 RING finger protein, as being involved in regulating proliferative fate. RFP-1 binds to MRG-1, a homologue of the mammalian chromodomain-containing protein MRG15 (MORF4L1), which has been implicated in promoting the proliferation of neural precursor cells. We find that C. elegans with reduced proteasome activity, or that lack RFP-1 expression, have increased levels of MRG-1 and a shift towards increased proliferation in sensitized genetic backgrounds. Likewise, reduction of MRG-1 partially suppresses stem cell overproliferation. MRG-1 levels are controlled independently of the spatially regulated GLP-1/Notch signalling pathway, which is the primary signal controlling the extent of stem cell proliferation in the C. elegans germ line. We propose a model in which MRG-1 levels are controlled, at least in part, by the proteasome, and that the levels of MRG-1 set a threshold upon which other spatially regulated factors act in order to control the balance between the proliferative fate and differentiation in the C. elegans germ line.

Keywords: E3 ubiquitin ligase, MRG-1, RFP-1, Substrate recognition subunit, Proteasomal degradation, Stem cell proliferative fate, Caenorhabditis elegans

Summary: The C. elegans chromodomain protein MRG-1 promotes proliferation in the germline, and its activity is regulated by the putative E3 ubiquitin ligase RFP-1 and proteasomal degradation.

INTRODUCTION

Proper development and tissue homeostasis require precise control of the extent of stem cell proliferation. Excess proliferation can lead to tumor formation, while reduced proliferation can lead to stem cell depletion. Multiple levels of gene control are often employed to ensure that the amount of proliferation is aligned with the needs of the tissue. In addition, the mammalian embryonic stem cell (ESC) system is highly dependent upon transcriptional regulation to control self-renewal (proliferation) and differentiation, relying heavily on the Sox2, Nanog and Oct4 (Pou5f1) transcription factors (Avilion et al., 2003; Chambers et al., 2003; Nichols et al., 1998); however, other modes of gene regulation have also been identified as being involved in regulating ESC proliferation, including protein phosphorylation (Li et al., 2011; Phanstiel et al., 2011), microRNA-mediated gene regulation (Martinez and Gregory, 2010) and the epigenetic modification of DNA (Meissner, 2010). Recently, protein degradation has also been implicated in regulating mammalian stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal (Buckley et al., 2012). We previously found that a reduction in proteasome function enhances overproliferation of stem cells in the C. elegans germ line (MacDonald et al., 2008), suggesting that a role for the proteasome in regulating stem cell proliferation might be conserved.

Proliferating cells in the C. elegans germ line are confined to the proliferative zone (PZ) at the distal ends of both gonad arms (Fig. 1A). As cells move proximally, they enter into meiotic prophase. From the very distal end of the gonad to where cells first show signs of entering meiotic prophase is a distance of ∼20 cell diameters (Crittenden et al., 1994; Hansen and Schedl, 2013; Kershner et al., 2013). The primary signal regulating whether a cell adopts a proliferating (mitotic) or differentiating (meiotic) fate is the canonical GLP-1/Notch signalling pathway, with high levels of signalling promoting the proliferative fate and low or absent levels more proximally allowing cells to enter meiotic prophase (Hansen and Schedl, 2013; Kershner et al., 2013) (Fig. 1B,C). GLP-1 signalling indirectly inhibits the activities of factors in two genetic pathways, referred to as the GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathways, that inhibit the proliferative fate and/or promote entry into meiotic prophase (Eckmann et al., 2004; Francis et al., 1995; Hansen et al., 2004b; Kadyk and Kimble, 1998) (Fig. 1B,C). GLD-1 is a translational regulator that contains a K homology (KH) RNA-binding domain (Crittenden et al., 2002; Hansen et al., 2004b; Jones et al., 1996; Jones and Schedl, 1995). GLD-1 levels are low in the distal end of the gonad, but increase gradually until reaching their maximum level in the transition zone (Jones et al., 1996). GLD-2 is the catalytic portion of a poly(A) polymerase and functions with GLD-3, a BicC homologue (Eckmann et al., 2004; Kadyk and Kimble, 1998). Factors in the GLD-1 pathway (GLD-1 and the Nanos-related NOS-3 protein) function redundantly with factors in the GLD-2 pathway (GLD-2 and GLD-3), such that each pathway is sufficient for relatively normal proliferative levels. However, if the activities of both pathways are disrupted, overproliferation occurs resulting in a germline tumor (Eckmann et al., 2004; Hansen et al., 2004b; Kadyk and Kimble, 1998).

Fig. 1.

C. elegans hermaphrodite germ line. (A) A dissected N2 (wild-type) hermaphrodite gonad immunostained with anti-REC-8 antibodies (green) for proliferative germ cells, anti-HIM-3 antibodies (red) for differentiating germ cells, and DAPI (blue) for DNA. The transition zone marks the region where meiotic entry is first visible. The somatic distal tip cell (DTC) caps the very distal end (asterisk) of the gonad. Scale bar: 50 µm. (B,C) GLP-1/Notch signalling inhibits the activities of GLD-1 NOS-3 and GLD-2 GLD-3, which allows proteins necessary for proliferation and proliferative fate-promoting proteins to be active. More proximally, GLP-1/Notch signalling levels decrease, and GLD-1 NOS-3 and GLD-2 GLD-3 become active, downregulating the activities of proteins necessary for proliferation and proteins promoting the proliferative fate. The proteasome acts in parallel to further decrease the activity of GLP-1/Notch signalling, proliferative fate-promoting proteins, and proteins necessary for proliferation. (D) The E3 ligase provides a scaffold to bind the E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme (E2) and substrate recognition subunit (SRS) to form a multi-subunit complex that binds the substrate. (E) The monomeric E3 ligase includes the SRS function, thus binding both the substrate and the E2 conjugating enzyme. (F) A living worm with ozIs2[GLD-1::GFP] observed under a dissecting microscope, showing the regions of GLD-1::GFP expression. (G) Diagram illustrating the increase in the space between the GLD-1::GFP expression in ozIs2[GLD-1::GFP] animals that have a larger proliferative (mitotic) zone (middle) as compared with wild-type animals (top) and tumorous animals (bottom).

This core genetic network controls the balance between the proliferative fate and differentiation. Presumably, this network promotes the expression of factors needed for proliferation, such as cell cycle regulators, in the PZ, and factors needed for meiosis, such as synaptonemal complex proteins, in the transition zone and beyond. Additionally, there are other factors, some promoting the proliferative fate and others promoting meiotic entry, that appear to work in parallel to the GLP-1 and GLD-1 GLD-2 pathways, presumably to reinforce or fine-tune the regulation accomplished through these pathways (Hansen and Schedl, 2013). As cells move from the distal mitotic region to the more proximal meiotic region, not only do meiotic proteins need to be expressed, but the activities of proteins that are necessary for proliferation must also be reduced. The role of the proteasome in regulating the balance between proliferative fate and differentiation might be to degrade proteins that promote the proliferative fate, as well as proteins that are necessary for proliferation, thereby allowing cells to differentiate. We previously demonstrated that partially reducing proteasome activity in a sensitized genetic background results in overproliferation (MacDonald et al., 2008). Therefore, when proteasome function is reduced, proteins that promote the proliferative fate may persist, resulting in stem cell overproliferation.

Proteins to be degraded by the proteasome are targeted through ubiquitylation (Komander, 2009; Pickart, 2001). An E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme first places ubiquitin on an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Then, an E3 ligase binds to both the E2 and to the substrate protein and facilitates the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 enzyme to the substrate (Komander, 2009; Pickart, 2001). E3 ligases can either be monomeric, in which different domains within a single protein bind to the E2 enzyme and substrate, or multi-subunit, in which multiple proteins accomplish these different functions and form a complex (Metzger et al., 2012) (Fig. 1D,E). Binding of the E3 ligase to the substrate protein is a critical step in providing specificity for this targeting reaction. Either the monomeric protein, or the substrate recognition subunit (SRS) of a multi-subunit complex, binds directly to the target protein and provides specificity. There are estimated to be more than 600 mammalian E3 ligases (Li et al., 2008), and potentially even more in C. elegans (Kipreos, 2005).

Here, we identify five putative E3 ubiquitin ligases or SRSs that enhance overproliferation when their activity is reduced. The RING finger protein RFP-1 shows the strongest overproliferation phenotype. We confirm that RFP-1 binds to MRG-1, which is homologous to the mammalian MRG15 (MORF4L1) chromodomain protein. MRG-1 has multiple functions in C. elegans, including facilitating synaptonemal complex-independent pairing of homologous chromosomes (Dombecki et al., 2011), maintaining genomic integrity in germ cells (Xu et al., 2012) and repressing the expression of X-linked genes in the germ line (Takasaki et al., 2007). Additionally, MRG-1 is necessary for proliferation of C. elegans primordial germ cells (Fujita et al., 2002; Takasaki et al., 2007), and loss of MRG15 reduces the proliferation capacity of neural precursor cells in mice (Chen et al., 2009). We demonstrate that MRG-1 also contributes to the proliferation capacity of stem cells in adult C. elegans, and that MRG-1 levels are controlled, at least in part, through proteasome-mediated protein degradation. We propose a model in which MRG-1 sets a threshold for proliferation upon which the spatially regulated GLP-1–GLD-1 GLD-2 signalling network acts.

RESULTS

Identification of E3 ligases involved in regulating stem cell proliferative fate

We previously determined that reduction in proteasome activity results in increased proliferation in sensitized genetic backgrounds in the C. elegans germ line (MacDonald et al., 2008), suggesting that the proteasome normally functions to inhibit the proliferative fate in the germ line. Our current model is that, in order for cells to enter meiotic prophase, the proteasome degrades proteins that promote the proliferative fate (which we refer to as proliferative fate-promoting proteins). We sought to identify these proliferative fate-promoting proteins and understand how their degradation contributes to the control of stem cell proliferation. Since a partial reduction of proteasome function results in increased proliferation in sensitized genetic backgrounds (MacDonald et al., 2008), we reasoned that a reduction in the activity of the ubiquitin system that targets proteins for degradation would also result in increased proliferation in these same genetic backgrounds. We further reasoned that since the SRS or a domain of the monomeric E3 ubiquitin ligase physically interacts with the protein to be degraded, we could use this as a means to identify proliferative fate-promoting proteins.

To identify the SRSs/monomeric E3 ligases that are involved in controlling stem cell proliferation, we performed an RNAi screen of the majority of the predicted SRSs/monomeric E3 ligases in the C. elegans genome. We speculated that there could be many proliferative fate-promoting proteins and that different SRSs/monomeric E3 ligases could target many of these proteins; therefore, reducing the function of any single SRS/monomeric E3 ligase might not yield a significant stem cell proliferation phenotype. We devised a screen that allowed us to detect even subtle amounts of overproliferation using the glp-1(oz264gf) gain-of-function allele at 20°C as a highly sensitive genetic background for overproliferation (Kerins et al., 2010). These animals also carried a transgene containing a GFP-tagged version of the GLD-1 protein, the levels of which are low or absent in proliferating cells and high as cells enter meiotic prophase (Jones et al., 1996; Schumacher et al., 2005) (Fig. 1F). An increase in the number of proliferative cells results in a larger PZ, which in turn causes the region where GLD-1 levels increase to be moved more proximally in the gonad (Hansen et al., 2004b). To identify animals containing modest amounts of overproliferation, we screened for animals in which the two regions of GLD-1 expression (from the two gonad arms) were further apart than in wild-type animals (Fig. 1G), as well as for animals with proliferative cells in the region where GLD-1 is normally expressed, or with proximal proliferation (see below). The animals screened also lacked rrf-1 activity, which reduces the effectiveness of RNAi in many somatic tissues, but not in the germ line (Kumsta and Hansen, 2012; Sijen et al., 2001). This reduced the possibility of an SRS/monomeric E3 ligase also functioning in other somatic processes, the disruption of which might mask a germline overproliferation phenotype.

We generated a list of 854 potential SRSs/monomeric E3 ligases by identifying those with domains typical of such proteins, including F-box, HECT, U-box, BTB/POZ, RING finger, SOC-box and VHL-box domains (supplementary material Methods and Table S1). We obtained 714 bacterial feeding RNAi clones from commercial libraries (Kamath and Ahringer, 2003; Rual et al., 2004) and constructed 109 clones that were not contained in these libraries, for a total of 823 potential SRSs/monomeric E3 ligases that we screened by feeding RNAi (supplementary material Table S1). Initial screening identified five potential candidates that appeared to increase proliferation in both the primary screen and a subsequent repeat of the RNAi (Fig. 2). To verify that reduction of function in these genes results in overproliferation, we performed RNAi by dsRNA injection and dissected and stained the gonads with anti-REC-8 and anti-HIM-3 antibodies, which mark proliferative and differentiating cells, respectively (supplementary material Table S2). We found that RNAi against fbxb-54, fbxa-171 and rle-1 resulted in overproliferation primarily in the proximal end of the gonad [proximal tumor (Pro) phenotype], which can be due to excess proliferation during larval development and contact with somatic cells that are normally in contact with proliferative cells (McGovern et al., 2009), although defects in processes other than stem cell proliferation can also cause this phenotype (Hansen and Schedl, 2013). RNAi against vps-11, when performed by dsRNA injection, resulted in embryonic lethality, precluding further analysis (supplementary material Table S2). RNAi against rfp-1, which encodes a RING finger protein (Crowe and Candido, 2004), gave the strongest phenotype, with proliferative cells present in patches throughout the gonad arm (as described below; Fig. 3D). Subsequent analyses focused primarily on this gene.

Fig. 2.

Genes identified in the SRS RNAi screen. pL4440 is the vector-only control. Animals were classified as tumorous if they had patches of proliferative cells outside of the proliferative zone (PZ). RNAi was performed on rrf-1(pk1417); glp-1(ar202gf) animals (18°C). For each gene, RNAi was performed three times and the results were averaged. Animals analyzed: pL4440, n=326; fbxb-54, n=251; fbxa-171, n=272; rfp-1, n=349; rle-1, n=261; vps-11, n=238. Error bars indicate s.d.

Fig. 3.

Loss of rfp-1 enhances overproliferation of glp-1(ar202gf). Gonads immunostained with anti-REC-8 antibodies (green) for proliferative cells, anti-HIM-3 antibodies (red) for meiotic cells, and with DAPI (blue) for germ cell nuclei. Gonads are outlined and an asterisk marks the distal end of each gonad. (A) N2 (wild-type) germ line. (B,C) Germ line of glp-1(ar202gf) single-mutant animals fed with either OP50 bacteria (B) or pL4440 RNAi vector only (C). These germ lines have an enlarged PZ, with no ectopic proliferative cells in the proximal germ line. (D) Germ line of glp-1(ar202gf) single mutant fed with rfp-1(RNAi). Large patches of proliferative cells are found throughout the germ line, including in the proximal germ line. (E) rfp-1(ok572) single mutant has a smaller PZ, with an average of 165 germ cells compared with 207 in the wild-type (N2) PZ (Table 2); however, germline polarity is similar to wild type. (F) rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) double mutant has proliferative cells throughout, interspersed with small patches of meiotic germ cells. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Characterization of rfp-1 involvement in the proliferative fate versus differentiation decision

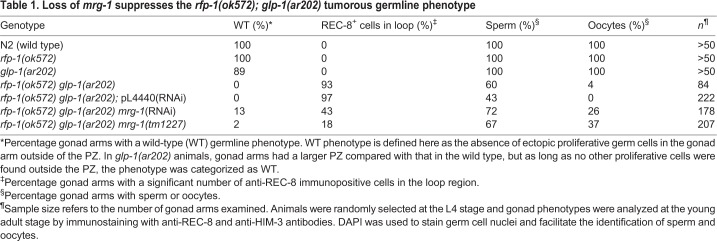

To help determine how rfp-1 functions in the proliferative fate versus differentiation decision, we more closely analyzed the overproliferation phenotype and determined how rfp-1 interacts with other genes in the genetic pathway regulating this decision. To determine if the enhancing activity of rfp-1 is specific to the glp-1(oz264gf) allele, we examined whether it could also enhance the glp-1(ar202gf) gain-of-function allele, which has been used extensively to analyze enhancement of proliferation (Hansen et al., 2004a; Pepper et al., 2003). We found that reducing RFP-1 activity either through RNAi or using the rfp-1(ok572) presumed null allele (supplementary material Fig. S1) caused significant overproliferation in glp-1(ar202gf) animals, as compared with either single mutant (Fig. 3, Table 1). The regions of overproliferation appear as large areas of proliferative cells, interspersed with regions of meiotic cells (Fig. 3D,F). Most gonads have proximal proliferation (Pro; 96%, n=24), with the locations and sizes of the interspersed proliferative regions differing somewhat from gonad to gonad (data not shown). Using the loop region where the gonad arm reflexes back as a landmark, we found that 93% of rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) gonad arms have proliferative cells in this region, whereas this phenotype is not displayed by gonads in any of the single mutants (Table 1). Indeed, rfp-1(ok572) single mutants have a wild-type polarity, with proliferative cells only being found in the distal end, and the PZ being even smaller than that in wild-type animals (Table 2). The smaller PZ is likely to reflect a function for RFP-1 other than in regulating the proliferative fate versus differentiation decision, such as regulating progression through the mitotic cell cycle. Smaller PZs have been observed for puf-8 and gld-1 single mutants, even though both genes strongly enhance glp-1(gf) overproliferation, suggesting that they also have additional functions (Hansen et al., 2004a; Racher and Hansen, 2012).

Table 1.

Loss of mrg-1 suppresses the rfp-1(ok572); glp-1(ar202) tumorous germline phenotype

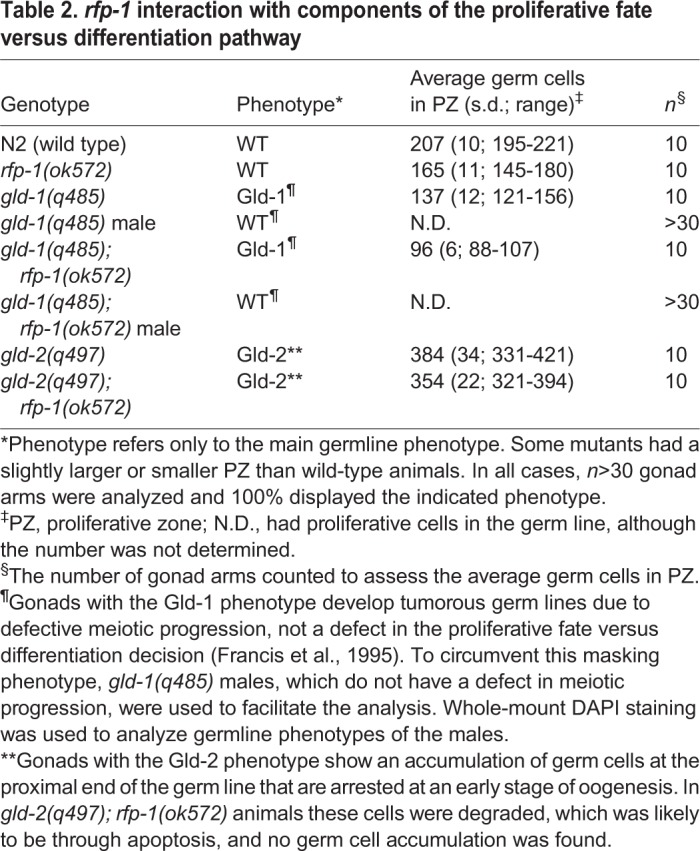

Table 2.

rfp-1 interaction with components of the proliferative fate versus differentiation pathway

To determine where rfp-1 might function in the genetic pathway regulating the proliferative fate versus meiotic entry decision, we examined whether rfp-1 functions in the GLD-1 or GLD-2 pathways that function downstream of GLP-1 signalling (Fig. 1B,C). The genes in these pathways inhibit the proliferative fate and/or promote meiotic entry, and their loss enhances overproliferation in sensitized genetic backgrounds, similar to that observed with the loss of rfp-1. If the activity of one pathway is removed, the balance between the proliferative fate and meiosis is essentially the same as in wild-type animals. However, if the activities of both pathways are removed simultaneously, most cells fail to switch from the proliferative fate to meiotic entry, resulting in a germline tumor (Hansen and Schedl, 2013; Kadyk and Kimble, 1998). We found that rfp-1(ok572) did not form a synthetic tumor with either gld-1(q485) or gld-2(q497), suggesting that rfp-1 does not function in either pathway (Table 2). These results are consistent with rfp-1 functioning parallel or downstream to the GLP-1 and GLD-1 GLD-2 genetic pathways.

Reduction in MRG-1 expression partially suppresses rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) overproliferation

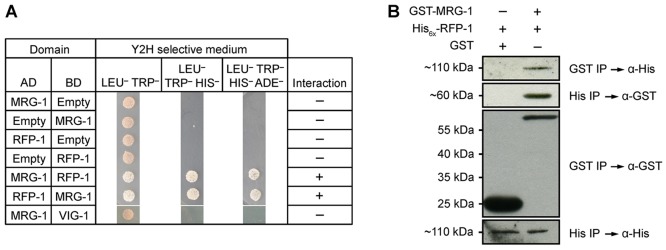

RFP-1 is likely to be a monomeric E3 ubiquitin ligase. It contains a conserved RING finger domain in its carboxy terminus (Crowe and Candido, 2004) and interacts with the E2 conjugating enzyme UBC-1 (Crowe and Candido, 2004). RFP-1 homologues in other systems, including BRE1 from yeast and rat Staring, have been shown to have E3 ligase activity (Chin et al., 2002; Ishino et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2003; Xuan et al., 2013). Therefore, reducing RFP-1 activity would be expected to impair the degradation of target proteins by the proteasome. This model suggests that the enhancing activity of rfp-1(ok572) or rfp-1(RNAi) is likely to be due to perdurance of proliferative fate-promoting proteins that are normally targets of proteasomal degradation. Reducing the expression of these proliferative fate-promoting proteins in rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) animals should reduce the extent of overproliferation. However, since E3 ligases may target multiple proteins for degradation, reducing the activity of a single proliferative fate-promoting protein might not completely suppress the overproliferation in rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) animals. RFP-1 was previously proposed to bind to MRG-1 based on a large-scale yeast two-hybrid screen (Li et al., 2004; Zhong and Sternberg, 2006), and the activity of MORF4, an MRG15 homologue in humans, is regulated by the proteasome (Tominaga et al., 2010). Using both yeast two-hybrid and bacterially expressed protein co-immunoprecipitation experiments, we have confirmed that MRG-1 and RFP-1 directly interact (Fig. 4). MRG-1 is necessary for proliferation of the primordial germ cells, with mutants lacking both maternal and zygotic activity completely lacking a germ line due to failure of the primordial germ cells to proliferate (Fujita et al., 2002). Additionally, the murine homologue of MRG-1, MRG15, promotes proliferation of neural precursor cells (Chen et al., 2009). Therefore, MRG-1 is a good candidate for a proliferative fate-promoting protein, the accumulation of which may be controlled through proteasomal degradation.

Fig. 4.

MRG-1 and RFP-1 physically interact. (A) Yeast two-hybrid screen showing interaction between MRG-1 and RFP-1. Yeast strains contain activation domain (AD) and DNA-binding domain (BD) vectors with no insert (Empty), full-length mrg-1 cDNA or full-length rfp-1 cDNA. Growth on Leu–Trp– medium indicates successful co-transformation, growth on Leu–Trp–His– indicates interaction, and growth on Leu–Trp–His–Ade– indicates strong interaction. vig-1 was used as an unrelated negative control. (B) Bacterial co-immunoprecipitation followed by western blot confirms the interaction between MRG-1 and RFP-1. His6x-RFP-1 was co-expressed in E. coli with either GST or GST-MRG-1. Immunoprecipitation of GST-MRG-1 also immunoprecipitated His6x-RFP-1, but not by GST alone (top panel). Likewise, using Ni-NTA beads GST-MRG-1 was isolated together with His6x-RFP-1 (second panel). Controls demonstrate that GST, GST-MRG-1 and His6x-RFP-1 were efficiently isolated (third and bottom panels).

To test this we first performed RNAi of mrg-1 in rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) animals and found that the extent of overproliferation was dramatically reduced as compared with control RNAi (Fig. 5C-E). Indeed, whereas 100% of rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) gonad arms have regions of proliferative cells outside of the PZ, 13% of rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) mrg-1(RNAi) gonad arms have a wild-type polarity. Additionally, rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) mrg-1(RNAi) gonads are reduced in the extent of ectopic proliferation, with only 43% of gonad arms having proliferative cells in the loop region as compared with 97% with the control RNAi (Table 1). We confirmed the RNAi results by analyzing rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) mrg-1(tm1227) triple-mutant animals, where the extent of ectopic proliferation was reduced compared with the rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) double mutant (Fig. 5F and Fig. 3F). However, the suppression was slightly weaker than with mrg-1 RNAi, which was likely to be due to a maternal contribution of MRG-1 in the mrg-1(tm1227) mutant. Since rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) mrg-1(tm1227) M−Z– animals lacked a germ line, we could only analyze M+Z– animals, in which some maternal MRG-1 would still be present (supplementary material Fig. S2A). Consistent with MRG-1 promoting the proliferative fate, mrg-1(RNAi) results in a smaller than normal PZ in otherwise wild-type animals (Xu et al., 2012), partially suppresses glp-1(ar202gf) overproliferation, and slightly enhances the glp-1(bn18ts) smaller PZ phenotype (supplementary material Fig. S3).

Fig. 5.

Reduction of mrg-1 expression partially suppresses the tumorous germline phenotype of rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf). Gonads stained with anti-REC-8 antibodies (green) for proliferative cells, anti-HIM-3 antibodies (red) for meiotic cells and with DAPI (blue) for germ cell nuclei. Gonads are outlined and an asterisk marks the distal end of each gonad. (A) N2 (wild-type) germ line. (B) mrg-1(RNAi) gonad has wild-type germline polarity. (C) rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) pL4440 vector-only RNAi control. Proliferative germ cells are present throughout the germ line, with small patches of meiotic germ cells. (D,E) Representative images of rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) mrg-1(RNAi) gonads that show tumor suppression. About 10% of the germ lines have a wild-type germline polarity (D), while ∼60% of the gonads show partial suppression (E). (F) Representative image of rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) mrg-1(tm1227) triple-mutant gonads showing partial tumor suppression. Scale bar: 50 μm.

The role of MRG-1 in influencing the proliferative fate versus differentiation decision could be accomplished by working in parallel to the GLP-1 and GLD-1 GLD-2 pathways, and affecting the activity of downstream proliferative fate-promoting and/or differentiation-promoting proteins. Alternatively, MRG-1 could directly affect the activity of the GLP-1 and GLD-1 GLD-2 pathways, either promoting GLP-1 signalling or inhibiting the GLD-1 and/or GLD-2 pathways. Since our genetic analysis of rfp-1 suggested that it functions parallel to, or downstream of, these pathways, if MRG-1 is regulated by RFP-1 then we expect MRG-1 to also function parallel to, or downstream of, these pathways. To test this we determined whether loss of MRG-1 activity could suppress proliferation when the activities of the GLP-1 and GLD-1 GLD-2 pathways are eliminated. gld-2(q497) gld-1(q485); glp-1(q175) animals have completely tumorous gonads (Hansen et al., 2004a). When MRG-1 levels were reduced by RNAi in these animals, 12% (n=136; data not shown) of the gonads contained large regions of cells that entered meiotic prophase, whereas none of the control gonads contained these regions (Fig. 6). This partial suppression suggests that at least part of the influence of MRG-1 on the proliferative fate versus differentiation decision does not involve controlling the GLP-1 and GLD-1 GLD-2 pathways. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that MRG-1 has some influence on these pathways, in addition to its role that is independent of them. That mrg-1 and rfp-1 both genetically function parallel to, or downstream of, the GLP-1 and GLD-1 GLD-2 signalling pathways is consistent with RFP-1 regulating MRG-1 activity.

Fig. 6.

mrg-1(RNAi) partially suppresses the tumorous germline phenotype of the gld-2 gld-1; glp-1 mutant. Gonads are stained with anti-REC-8 antibodies (green) for proliferative cells, anti-HIM-3 antibodies (red) for meiotic cells and with DAPI (blue) for germ cell nuclei. Gonads are outlined and an asterisk marks the distal end. Patches of meiotic cells are interspersed in gonads of animals fed with mrg-1(RNAi) (12%, n=136; B) but not in control animals with pL4440 vector-only RNAi (0%, n=117; A). Actual genotype is gld-2(q497) gld-1(q485); unc-32(e189) glp-1(q175). Scale bar: 50 μm.

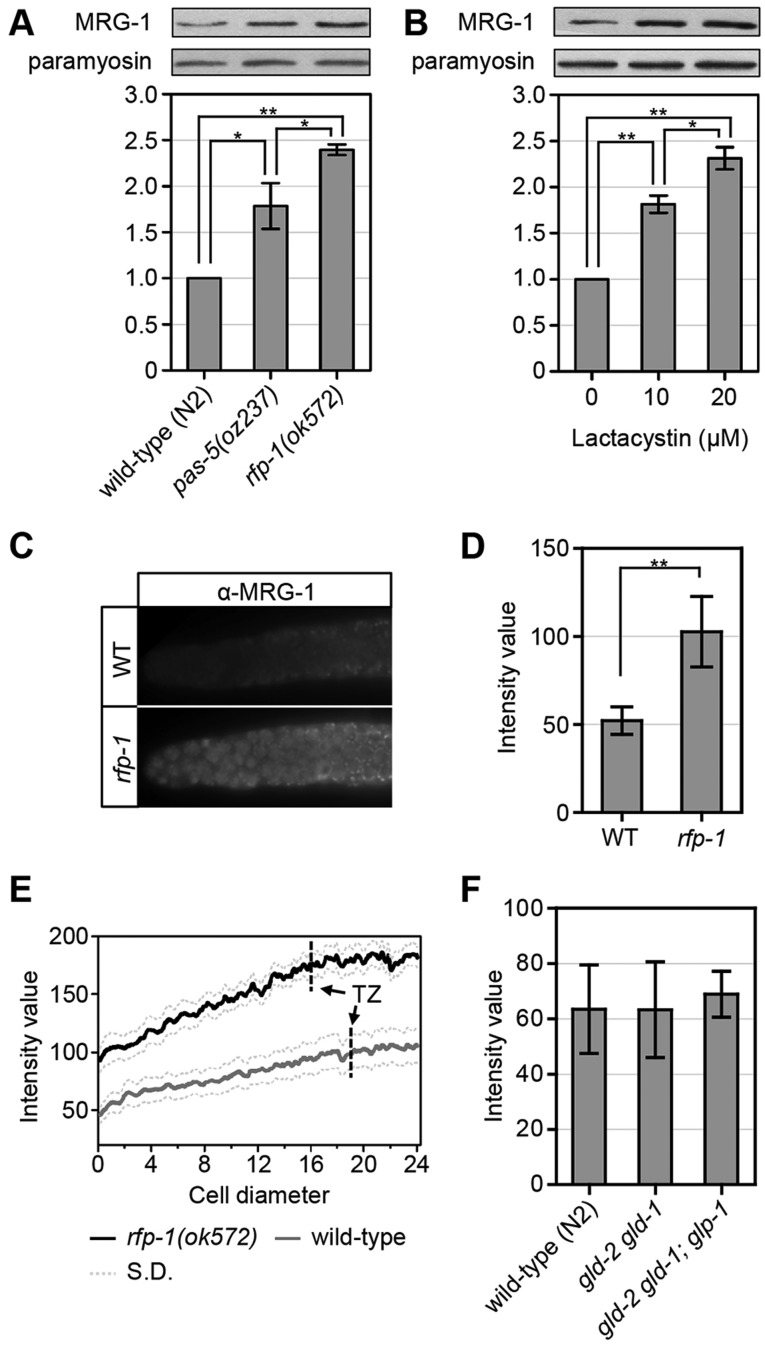

MRG-1 is degraded by the proteasome

To further test our model that proteasomal degradation contributes to the control of MRG-1 levels, we analyzed the levels of MRG-1 protein in animals with reduced proteasome activity. PAS-5 is a highly conserved alpha subunit of the proteasome, with pas-5(oz237) mutant animals having a partial reduction in proteasome activity (MacDonald et al., 2008). We found that MRG-1 levels increase ∼1.8-fold in pas-5(oz237) animals (Fig. 7A), suggesting that the wild-type levels of MRG-1 are likely to be controlled, at least in part, by proteasomal degradation. To further verify that MRG-1 levels increase when proteasome activity is reduced, we treated wild-type animals with the proteasomal inhibitor lactacystin. We found that MRG-1 levels increase ∼1.9-fold at 10 µM and ∼2.4-fold at 20 µM (Fig. 7B). We also observed that MRG-1 becomes ubiquitylated (supplementary material Fig. S4). Therefore, MRG-1 levels are likely to be reduced in wild-type animals through proteasomal degradation.

Fig. 7.

MRG-1 level is regulated by the proteasome. (A,B) MRG-1 levels increase when proteasome activity is reduced. (A) MRG-1 levels are higher in pas-5(oz237) and rfp-1(ok572) mutants compared with N2 (wild type). (B) Animals treated with increasing concentrations of lactacystin (proteasome inhibitor) have increasing MRG-1 levels. For both A and B, intensity measurements were averaged from four separate experiments. (C-E) MRG-1 levels are higher in rfp-1(ok572) single mutants. (C) Representative images of wild-type and rfp-1(ok572) gonads immunostained with anti-MRG-1 antibodies. MRG-1 is detected even at the most distal end of the wild-type gonad, but at lower levels than in rfp-1(ok572) mutants (see D and supplementary material Fig. S2). (D) Average MRG-1 intensity is higher in rfp-1(ok572) gonads than in wild type (n=23). (E) Average MRG-1 intensity along the gonad arm from distal end to transition zone (TZ) (n=9). MRG-1 levels are higher in rfp-1(ok572) mutants than in wild type, with lower levels in the distal end than in the transition zone. Dotted lines indicate s.d. In C-E, actual genotypes are unc-32(e189) for wild type and rfp-1(ok572) unc-32(e189) for rfp-1. (F) Average MRG-1 levels are similar in wild-type, gld-2(q497) gld-1(q485) and gld-2(q497) gld-1(q485); glp-1(q175) gonads (n=14). Actual genotypes are unc-32(e189), gld-2(q497) gld-1(q485); unc-32(e189) and gld-2(q497) gld-1(q485); unc-32(e189) glp-1(q175). (A,B,D) *P<0.01, **P<0.001, two-tailed Student's t-test. Error bars indicate s.d.

To determine whether RFP-1 is likely to be a monomeric E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets MRG-1 for degradation, we analyzed MRG-1 levels in rfp-1(ok572) animals and found that they increase ∼2.5-fold as compared with wild-type animals (Fig. 7A). To verify that this increase in MRG-1 accumulation occurs in the tissue relevant to germline proliferation, we used indirect immunofluorescence to analyze MRG-1 levels in dissected gonads and found an increase of ∼2-fold in rfp-1(ok572) mutants as compared with wild-type animals (Fig. 7C,D).

Spatial regulation of MRG-1

We suggest that MRG-1 normally promotes the proliferative fate in the germ line, and proteasomal degradation of MRG-1 helps to control the level of proliferation. We envision two models for how this could occur. First, MRG-1 levels might be spatially regulated, with high levels in the distal end of the gonad where proliferative cells are located. Proteasomal degradation of MRG-1 would occur more proximally, allowing cells to cease proliferating and enter into meiotic prophase. In the second model, MRG-1 levels would be relatively uniform throughout the gonad, and the amount of MRG-1 sets a threshold upon which other spatially regulated molecules act. To distinguish between these possibilities, we analyzed the spatial distribution and overall level of MRG-1 in wild-type and rfp-1(ok572) gonads. We found that MRG-1 levels are relatively constant throughout the distal end of the gonad in wild-type gonads, with no observable decrease in levels as cells enter into meiotic prophase (Fig. 7C,E). Indeed, MRG-1 levels even appear slightly higher more proximally. Overall MRG-1 levels are higher in the rfp-1(ok572) mutant, and show the same general pattern of accumulation as in wild-type gonads (Fig. 7C-E). This accumulation pattern is more consistent with our second model, whereby MRG-1 could be active throughout the gonad, and other factors ensure that this activity promotes proliferation only in the PZ. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that MRG-1 activity is restricted to this region through some form of post-translational modification (see Discussion).

The GLP-1 and GLD-1 GLD-2 signalling network is the primary mechanism by which spatial control of the proliferative fate versus differentiation is achieved (Hansen and Schedl, 2013). If MRG-1 does set a threshold for this signalling network, it would be expected that this network would not control MRG-1 levels. To test this, we analyzed MRG-1 levels in gld-2(q497) gld-1(q485) double mutants. Since GLD-1 and GLD-2 inhibit the proliferative fate and/or promote meiotic entry, if they regulate MRG-1 levels then such levels would be expected to increase in gld-2(q497) gld-1(q485) mutants. However, we observed the same level of MRG-1 accumulation in gld-2(q497) gld-1(q485) mutants as in wild-type animals, suggesting that this signalling pathway does not control MRG-1 levels (Fig. 7F). It is possible that GLP-1 signalling might promote MRG-1 levels through a pathway that is independent of GLD-1 and GLD-2, including through the hypothesized third pathway that functions redundantly with GLD-1 and GLD-2 (Hansen et al., 2004a). However, MRG-1 levels are not decreased when glp-1 activity is also removed, suggesting that this is not the case (Fig. 7F). Therefore, the level of MRG-1 accumulation is important in regulating the balance between the proliferative fate and differentiation; however, its accumulation is not controlled by the GLP-1 and GLD-1 GLD-2 signalling pathways. Rather, MRG-1 levels are independently controlled and might set a threshold upon which this pathway acts.

DISCUSSION

Role of the proteasome in regulating stem cell proliferation

Although many modes of gene regulation have been implicated in regulating the balance between the proliferative fate and differentiation in various stem cell systems, there has been relatively little exploration of proteasome-mediated protein turnover in controlling this balance. Here we describe the role of the proteasome in regulating the accumulation of MRG-1, a protein implicated in promoting the proliferative fate in various systems (Chen et al., 2009; Tominaga et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2010). We found that reducing proteasome activity, or mutating the putative E3 ligase RFP-1, elevated the levels of MRG-1 and enhanced stem cell overproliferation. Given that RFP-1 and MRG-1 physically interact, RFP-1 is likely to function as the E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets MRG-1 for degradation, although we cannot rule out the possibility that RFP-1 could regulate the activity of another factor which then targets MRG-1 for degradation. Importantly, reducing the level of MRG-1 suppressed the overproliferation observed in rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) animals, although not completely. Therefore, RFP-1 is likely to target other proteins for degradation that are also involved in regulating the balance between the proliferative fate and differentiation. Additionally, we identified four other SRSs/monomeric E3 ligases that are likely to be involved in regulating this balance, each of which may target one or more proteins. Finally, our initial genetic analysis of pas-5(oz237) suggested that the proteasome targets proteins in both the GLP-1 signalling pathway and in the GLD-1 pathway (MacDonald et al., 2008). Therefore, many proteins are likely to be involved in regulating the balance between proliferative fate and differentiation, the activities of which are controlled, at least in part, through proteasome-mediated turnover.

Recent work with mammalian ESCs and induced pluripotent stem cells found that many of the factors that are involved in regulating pluripotency and differentiation are ubiquitylated, and that reduction of the activities of many ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases is required for proper self-renewal and differentiation (Buckley et al., 2012). Thus, proteasomally mediated degradation is likely to be a conserved mechanism for regulating the activity of factors that control the balance between the proliferative fate and differentiation.

MRG-1 promotes the proliferative fate

A lack of maternal and zygotic MRG-1 results in C. elegans lacking a germ line due to a failure of the primordial germ cells to proliferate (Fujita et al., 2002; Takasaki et al., 2007). Here, we demonstrate that MRG-1 also plays a role in promoting the proliferative fate and/or inhibiting differentiation in the adult germ line. MRG-1 contains a chromodomain and has homologues from yeast to humans (Bertram et al., 1999; Gorman et al., 1995; Nakayama et al., 2003; Reid et al., 2004). It associates with chromatin (Takasaki et al., 2007), and MRG15, the mammalian homologue, complexes with proteins involved in acetylation (Akhtar and Becker, 2000; Cai et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2009; Doyon et al., 2004; Eisen et al., 2001; Hayakawa et al., 2007; Ikura et al., 2000; Joshi and Struhl, 2005; Pardo et al., 2002; Yochum and Ayer, 2002); as such, MRG-1 is likely to be involved in controlling the expression of many genes. The mammalian homologue associates with both acetyltransferases and deacetylases. Additionally, it has been shown in other organisms, including Drosophila, yeast and humans, that MORF/MRG family proteins are associated with complexes that are involved in the activation or repression of target gene transcription. Some of these target genes, including B-myb, cdc-2 and p53, are known to control cell proliferation (Alekseyenko et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2011, 2010; Kind et al., 2008; Leung et al., 2001; Martrat et al., 2011; Pena and Pereira-Smith, 2007; Peña et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2005; Tominaga et al., 2003). Therefore, MRG-1 could both promote the expression of proteins necessary for proliferation and repress the expression of proteins necessary for differentiation. Its influence on stem cell proliferation might be conserved, as lack of MRG15, the MRG-1 homologue in mammals, results in smaller and fewer murine neurospheres (Chen et al., 2009).

MRG-1 sets a threshold upon which other factors act

The balance between the proliferative fate and differentiation in the C. elegans germ line is regulated by a number of factors with activities that are spatially regulated (Hansen and Schedl, 2013; Kershner et al., 2013). GLP-1 signalling activity is presumed to be high in the distal end of the gonad in the PZ, but decreases more proximally as GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathway levels increase, allowing cells to cease proliferation and enter into meiotic prophase (Hansen and Schedl, 2013; Kershner et al., 2013). This signalling pathway presumably promotes the accumulation and activity of proteins in the distal end of the gonad that are necessary for proliferation and of proteins that are necessary for meiosis more proximally.

Here, we demonstrate that MRG-1 promotes the proliferative fate; however, MRG-1 protein is not enriched in the PZ (Takasaki et al., 2007) (Fig. 7E). Additionally, the GLP-1 and GLD-1 GLD-2 pathways do not control the level and pattern of MRG-1 accumulation (Fig. 7F). It remains possible that MRG-1 activity is restricted to the PZ through some other mechanism, such as post-translational modification; however, we consider this unlikely because MRG-1 has been shown to have functions in more proximal regions of the gonad, including maintaining genomic integrity in meiotic cells, silencing X-linked genes and facilitating pairing of homologous chromosomes (Dombecki et al., 2011; Fujita et al., 2002; Olgun et al., 2005; Takasaki et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2012). We propose a model in which MRG-1 sets a threshold for the proliferative fate upon which the spatially regulated molecules of the GLP-1 and GLD-1 GLD-2 pathways act (Fig. 8). As part of this model, MRG-1 levels are controlled, at least in part, by the proteasome. MRG-1 could be thought of as priming cells for the proliferative fate, and if MRG-1 levels are too high, as in the rfp-1 mutant, cells are more primed for the proliferative fate.

Fig. 8.

MRG-1 sets up a threshold for proliferation and differentiation. White and grey bars represent hypothetical levels of GLD-1 GLD-2 pathway activity in the distal and proximal germ line, respectively. Dashed lines indicate a hypothetical threshold set by MRG-1 and the corresponding activity of factors controlled by MRG-1. Differentiation occurs if GLD-1 GLD-2 pathway levels are above the MRG-1 threshold and proliferation occurs if the pathway levels are below the threshold. In the wild type and in permissive glp-1(ar202gf) conditions, GLD-1 GLD-2 pathway levels are sufficient to promote differentiation in the proximal germ line, but not in the distal germ line, even though GLD-1 GLD-2 pathway levels are likely to be lower in glp-1(ar202gf) animals. In rfp-1(ok572) glp-1(ar202gf) animals, MRG-1 levels increase (due to decreased degradation), raising the threshold, such that proliferation occurs in the proximal end. In mrg-1(lf) animals (M–Z–), the threshold is lowered; therefore, even minimal levels of GLD-1 GLD-2 pathway activity promote differentiation.

All proteins within the GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathways appear to affect the level of translation and/or stability of target mRNAs, although targets specific to the proliferative fate versus differentiation decision are yet to be characterized (Hansen and Schedl, 2013; Kershner et al., 2013; Racher and Hansen, 2010). Since MRG-1 homologues associate with acetyltransferases, MRG-1 could control the level of transcription of many genes and could set the threshold by keeping the abundance of mRNAs at a level that allows their translation or stability to be properly controlled by GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathway proteins. If MRG-1 levels are too high, this could result in mRNAs – presumably encoding proteins that are necessary for proliferation – to be expressed at too high a level to be properly repressed by GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathway proteins in the proximal region of the gonad. For those genes that are repressed by MRG-1 – which may encode proteins that promote meiotic entry – transcription levels might be too low in the presence of excess MRG-1 for GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathway proteins to properly stabilize their mRNAs or promote translation. Although the higher levels of MRG-1 that are present in rfp-1 mutants are not sufficient on their own to cause overproliferation, when they are combined with a glp-1(gf) mutation, which presumably lowers GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathway activity, overproliferation occurs (Fig. 8). Identification of genes whose transcription is influenced by MRG-1 activity, and whose translation is regulated by the GLD-1 and GLD-2 pathways, will be the next step in understanding how MRG-1 levels help to control the extent of proliferation in the C. elegans germ line.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General methods and nematode strains

C. elegans handling, genetic manipulation and maintenance were performed using standard methods (Brenner, 1974). Experiments were performed at 20°C and animals were prepared by L1 synchronization as described by Wang et al. (2014) unless otherwise stated. Lactacystin treatment was performed as previously described (Ding et al., 2007). Lactacystin (Cayman Chemicals, #70980) in DMSO, or DMSO alone, was added to synchronized wild-type L1 animals in M9 minimal medium containing OP50 bacteria and grown at 20°C for 2-3 days. Alleles used: linkage group I (LGI): gld-2(q497), rrf-1(pk1417), gld-1(q485); LGII: ozIs2[GLD-1::GFP]; LGIII: rfp-1(ok572), unc-32(e189), glp-1(q175), glp-1(ar202), glp-1(oz264), mrg-1(tm1227).

Computational search for C. elegans SRSs and monomeric E3 ligases

A list of potential C. elegans SRSs and monomeric E3 ligases was compiled through a computational search using WormMart (http://www.wormbase.org) as outlined in the supplementary material Methods.

RNA interference

RNAi was performed by feeding as previously described (unless otherwise stated) (Wang et al., 2014). RNAi vectors for genes not available from commercial RNAi libraries were constructed through TA cloning as previously described (Holton and Graham, 1991) using the L4440 vector (Timmons and Fire, 1998). For the SRS/monomeric E3 ligase RNAi screen, L4 and young adult (1 day past L4) stage rrf-1(pk1417); ozIs2[GLD-1::GFP]; glp-1(oz264gf) animals were grown on RNAi plates at 20°C. F1 animals were analyzed for an overproliferation phenotype based on a larger than normal space between the two regions of GLD-1::GFP expression, or an increase in clear regions in the gonad (Fig. 1F,G). Positives were repeated and tested through RNAi on rrf-1(pk1417); glp-1(ar202gf) by feeding and on rrf-1(pk1417); ozIs2[GLD-1::GFP]; glp-1(oz264gf) by dsRNA injection as previously described (MacDonald et al., 2008).

Gonad dissection, immunostaining and imaging

Gonad dissection and staining were performed as previously described (Jones et al., 1996). Dissected gonads were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 5-8 min at room temperature. Post-fixation was performed with 100% methanol overnight at −20°C. Gonads were blocked with 30% goat serum at room temperature for 1 h and incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies were: anti-REC-8 (Pasierbek et al., 2001) (1:200), anti-HIM-3 (Zetka et al., 1999) (1:400), anti-Nop1p (EnCor Biotech, MCA-38F3; 1:200) and anti-MRG-1 (Novus Biologicals, 4913.00.02; 1:1000) (Fujita et al., 2002). Secondary antibodies used were rabbit Alexa 594 (Molecular Probes, A21207; 1:500) and rat and mouse Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes, A21208 and A21202; 1:200). DNA was visualized by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. Images were captured using a Zeiss Imager Z.1 microscope with an AxioCam MRm camera (Zeiss). Dissected gonads and other worm tissues were mounted on slides. To achieve consistent display, other tissues were cropped out of the immunofluorescence images in Fig. 1A,F and Figs 3, 5 and 6, so that only the gonad arms are shown. Fluorescence intensity was measured as described in the supplementary material Methods.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2012). For further details, see the supplementary material Methods.

Yeast two-hybrid analysis

mrg-1 and rfp-1 cDNAs were PCR amplified from wild-type (N2) cDNA using primers A61 and A62 (for mrg-1) and B21 and B22 (for rfp-1), and cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega); for primers see supplementary material Methods. NdeI and EcoRI sites (for mrg-1) and SmaI and BamHI sites (for rfp-1) were used to subclone mrg-1 and rfp-1 into pGBKT7 (DNA-binding domain) and pGADT7 (activation domain) from the Matchmaker Two-Hybrid System 3 (Clontech). Combinations of pDH310 (mrg-1 in pGBKT7), pDH311 (mrg-1 in pGADT7), pDH339 (rfp-1 in pGADT7), pDH340 (rfp-1 in pGBKT7) and empty vector controls were co-transformed into the AH109 yeast strain (Matchmaker Two-Hybrid System 3).

Bacterial co-immunoprecipitation

Bacterial co-immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2012). MRG-1 (1-337 aa) and RFP-1 (1-834 aa) cDNAs were PCR amplified (C1 and C2 primers for rfp-1, C3 and C4 for mrg-1; see supplementary material Methods) and cloned into pGEX-4T1 (GE Healthcare) and pET-29a (Novagen), respectively, to generate plasmids pDH354 and pDH355. GST-tag and His6x-tag proteins were co-expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS. His6x-RFP-1 fusion proteins that bound to GST-MRG-1 were co-immunoprecipitated using glutathione agarose beads (GE Healthcare). GST-MRG-1 proteins that interact with His6x-RFP-1 were purified on Ni-NTA beads (Qiagen).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the D.H. laboratory for helpful discussions; Vanina Zaremberg, Marcus Samuel, Subramanian Sankaranarayanan, John Cobb, Stanley Neufeld, Monique Zetka, Tim Schedl, Jim McGhee and Paul Mains for helpful advice, reagents and strains; and anonymous reviewers for suggestions and insights.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

P.G. and X.W. performed experiments associated with mrg-1 and helped in preparation of the manuscript. L.L., B.B. and X.W. performed experiments associated with the SRS RNAi screen and downstream genetic analyses of rfp-1. C.W. performed experiments related to the co-immunoprecipitation. K.J. helped with mrg-1 RNAi experiments. D.H. developed the concepts, experimental approaches and prepared the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to D.H., and by a studentship from the CIHR Training Program in Genetics, Child Development and Health to L.L. Some strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), which is funded by the National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs [P40 OD010440].

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.115147/-/DC1

References

- Akhtar A. and Becker P. B. (2000). Activation of transcription through histone H4 acetylation by MOF, an acetyltransferase essential for dosage compensation in Drosophila. Mol. Cell 5, 367-375. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80431-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alekseyenko A. A., Larschan E., Lai W. R., Park P. J. and Kuroda M. I. (2006). High-resolution ChIP-chip analysis reveals that the Drosophila MSL complex selectively identifies active genes on the male X chromosome. Genes Dev. 20, 848-857. 10.1101/gad.1400206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avilion A. A., Nicolis S. K., Pevny L. H., Perez L., Vivian N. and Lovell-Badge R. (2003). Multipotent cell lineages in early mouse development depend on SOX2 function. Genes Dev. 17, 126-140. 10.1101/gad.224503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram M. J., Berube N. G., Hang-Swanson X., Ran Q., Leung J. K., Bryce S., Spurgers K., Bick R. J., Baldini A., Ning Y. et al. (1999). Identification of a gene that reverses the immortal phenotype of a subset of cells and is a member of a novel family of transcription factor-like genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 1479-1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley S. M., Aranda-Orgilles B., Strikoudis A., Apostolou E., Loizou E., Moran-Crusio K., Farnsworth C. L., Koller A. A., Dasgupta R., Silva J. C. et al. (2012). Regulation of pluripotency and cellular reprogramming by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Cell Stem Cell 11, 783-798. 10.1016/j.stem.2012.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Jin J., Tomomori-Sato C., Sato S., Sorokina I., Parmely T. J., Conaway R. C. and Conaway J. W. (2003). Identification of new subunits of the multiprotein mammalian TRRAP/TIP60-containing histone acetyltransferase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 42733-42736. 10.1074/jbc.C300389200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers I., Colby D., Robertson M., Nichols J., Lee S., Tweedie S. and Smith A. (2003). Functional expression cloning of Nanog, a pluripotency sustaining factor in embryonic stem cells. Cell 113, 643-655. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00392-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Takano-Maruyama M., Pereira-Smith O. M., Gaufo G. O. and Tominaga K. (2009). MRG15, a component of HAT and HDAC complexes, is essential for proliferation and differentiation of neural precursor cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 87, 1522-1531. 10.1002/jnr.21976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Tominaga K. and Pereira-Smith O. M. (2010). Emerging role of the MORF/MRG gene family in various biological processes, including aging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1197, 134-141. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05197.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Pereira-Smith O. M. and Tominaga K. (2011). Loss of the chromatin regulator MRG15 limits neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation via increased expression of the p21 Cdk inhibitor. Stem Cell Res. 7, 75-88. 10.1016/j.scr.2011.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin L.-S., Vavalle J. P. and Li L. (2002). Staring, a novel E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase that targets syntaxin 1 for degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35071-35079. 10.1074/jbc.M203300200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden S. L., Troemel E. R., Evans T. C. and Kimble J. (1994). GLP-1 is localized to the mitotic region of the C. elegans germ line. Development 120, 2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden S. L., Bernstein D. S., Bachorik J. L., Thompson B. E., Gallegos M., Petcherski A. G., Moulder G., Barstead R., Wickens M. and Kimble J. (2002). A conserved RNA-binding protein controls germline stem cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 417, 660-663. 10.1038/nature754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe E. and Candido E. P. M. (2004). Characterization of C. elegans RING finger protein 1, a binding partner of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 1. Dev. Biol. 265, 446-459. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding M., Chao D., Wang G. and Shen K. (2007). Spatial regulation of an E3 ubiquitin ligase directs selective synapse elimination. Science 317, 947-951. 10.1126/science.1145727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombecki C. R., Chiang A. C. Y., Kang H.-J., Bilgir C., Stefanski N. A., Neva B. J., Klerkx E. P. F. and Nabeshima K. (2011). The chromodomain protein MRG-1 facilitates SC-independent homologous pairing during meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Cell 21, 1092-1103. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon Y., Selleck W., Lane W. S., Tan S. and Cote J. (2004). Structural and functional conservation of the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex from yeast to humans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 1884-1896. 10.1128/MCB.24.5.1884-1896.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckmann C. R., Crittenden S. L., Suh N. and Kimble J. (2004). GLD-3 and control of the mitosis/meiosis decision in the germline of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 168, 147-160. 10.1534/genetics.104.029264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen A., Utley R. T., Nourani A., Allard S., Schmidt P., Lane W. S., Lucchesi J. C. and Cote J. (2001). The yeast NuA4 and Drosophila MSL complexes contain homologous subunits important for transcription regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 3484-3491. 10.1074/jbc.M008159200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R., Maine E. and Schedl T. (1995). Analysis of the multiple roles of gld-1 in germline development: interactions with the sex determination cascade and the glp-1 signaling pathway. Genetics 139, 607-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M., Takasaki T., Nakajima N., Kawano T., Shimura Y. and Sakamoto H. (2002). MRG-1, a mortality factor-related chromodomain protein, is required maternally for primordial germ cells to initiate mitotic proliferation in C. elegans. Mech. Dev. 114, 61-69. 10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00058-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman M., Franke A. and Baker B. S. (1995). Molecular characterization of the male-specific lethal-3 gene and investigations of the regulation of dosage compensation in Drosophila. Development 121, 463-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen D. and Schedl T. (2013). Stem cell proliferation versus meiotic fate decision in Caenorhabditis elegans. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 757, 71-99. 10.1007/978-1-4614-4015-4_4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen D., Hubbard E. J. A. and Schedl T. (2004a). Multi-pathway control of the proliferation versus meiotic development decision in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Dev. Biol. 268, 342-357. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen D., Wilson-Berry L., Dang T. and Schedl T. (2004b). Control of the proliferation versus meiotic development decision in the C. elegans germline through regulation of GLD-1 protein accumulation. Development 131, 93-104. 10.1242/dev.00916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa T., Ohtani Y., Hayakawa N., Shinmyozu K., Saito M., Ishikawa F. and Nakayama J. (2007). RBP2 is an MRG15 complex component and down-regulates intragenic histone H3 lysine 4 methylation. Genes Cells 12, 811-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holton T. A. and Graham M. W. (1991). A simple and efficient method for direct cloning of PCR products using ddT-tailed vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 1156 10.1093/nar/19.5.1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura T., Ogryzko V. V., Grigoriev M., Groisman R., Wang J., Horikoshi M., Scully R., Qin J. and Nakatani Y. (2000). Involvement of the TIP60 histone acetylase complex in DNA repair and apoptosis. Cell 102, 463-473. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00051-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishino Y., Hayashi Y., Naruse M., Tomita K., Sanbo M., Fuchigami T., Fujiki R., Hirose K., Toyooka Y., Fujimori T. et al. (2014). Bre1a, a histone H2B ubiquitin ligase, regulates the cell cycle and differentiation of neural precursor cells. J. Neurosci. 34, 3067-3078. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3832-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A. R. and Schedl T. (1995). Mutations in gld-1, a female germ cell-specific tumor suppressor gene in Caenorhabditis elegans, affect a conserved domain also found in Src-associated protein Sam68. Genes Dev. 9, 1491-1504. 10.1101/gad.9.12.1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A. R., Francis R. and Schedl T. (1996). GLD-1, a cytoplasmic protein essential for oocyte differentiation, shows stage- and sex-specific expression during Caenorhabditis elegans germline development. Dev. Biol. 180, 165-183. 10.1006/dbio.1996.0293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A. A. and Struhl K. (2005). Eaf3 chromodomain interaction with methylated H3-K36 links histone deacetylation to Pol II elongation. Mol. Cell 20, 971-978. 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadyk L. C. and Kimble J. (1998). Genetic regulation of entry into meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 125, 1803-1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath R. S. and Ahringer J. (2003). Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods 30, 313-321. 10.1016/S1046-2023(03)00050-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerins J. A., Hanazawa M., Dorsett M. and Schedl T. (2010). PRP-17 and the pre-mRNA splicing pathway are preferentially required for the proliferation versus meiotic development decision and germline sex determination in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Dyn. 239, 1555-1572. 10.1002/dvdy.22274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershner A., Crittenden S. L., Friend K., Sorensen E. B., Porter D. F. and Kimble J. (2013). Germline stem cells and their regulation in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 786, 29-46. 10.1007/978-94-007-6621-1_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind J., Vaquerizas J. M., Gebhardt P., Gentzel M., Luscombe N. M., Bertone P. and Akhtar A. (2008). Genome-wide analysis reveals MOF as a key regulator of dosage compensation and gene expression in Drosophila. Cell 133, 813-828. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipreos E. T. (2005). Ubiquitin-mediated pathways in C. elegans. WormBook, 1–24. www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komander D. (2009). The emerging complexity of protein ubiquitination. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 937-953. 10.1042/BST0370937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumsta C. and Hansen M. (2012). C. elegans rrf-1 mutations maintain RNAi efficiency in the soma in addition to the germline. PLoS ONE 7, e35428 10.1371/journal.pone.0035428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung J. K., Berube N., Venable S., Ahmed S., Timchenko N. and Pereira-Smith O. M. (2001). MRG15 activates the B-myb promoter through formation of a nuclear complex with the retinoblastoma protein and the novel protein PAM14. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39171-39178. 10.1074/jbc.M103435200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Armstrong C. M., Bertin N., Ge H., Milstein S., Boxem M., Vidalain P.-O., Han J.-D. J., Chesneau A., Hao T. et al. (2004). A map of the interactome network of the metazoan C. elegans. Science 303, 540-543. 10.1126/science.1091403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Bengtson M. H., Ulbrich A., Matsuda A., Reddy V. A., Orth A., Chanda S. K., Batalov S. and Joazeiro C. A. P. (2008). Genome-wide and functional annotation of human E3 ubiquitin ligases identifies MULAN, a mitochondrial E3 that regulates the organelle's dynamics and signaling. PLoS ONE 3, e1487 10.1371/journal.pone.0001487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q.-R., Xing X.-B., Chen T.-T., Li R.-X., Dai J., Sheng Q.-H., Xin S.-M., Zhu L.-L., Jin Y., Pei G. et al. (2011). Large scale phosphoproteome profiles comprehensive features of mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, M110.001750 10.1074/mcp.M110.001750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Oh S.-M., Okada M., Liu X., Cheng D., Peng J., Brat D. J., Sun S.-y., Zhou W., Gu W. et al. (2009). Human BRE1 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase for Ebp1 tumor suppressor. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 757-768. 10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald L. D., Knox A. and Hansen D. (2008). Proteasomal regulation of the proliferation vs. meiotic entry decision in the Caenorhabditis elegans germ line. Genetics 180, 905-920. 10.1534/genetics.108.091553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez N. J. and Gregory R. I. (2010). MicroRNA gene regulatory pathways in the establishment and maintenance of ESC identity. Cell Stem Cell 7, 31-35. 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martrat G., Maxwell C. A., Tominaga E., Porta-de-la-Riva M., Bonifaci N., Gómez-Baldó L., Bogliolo M., Lázaro C., Blanco I., Brunet J. et al. (2011). Exploring the link between MORF4L1 and risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 13, R40 10.1186/bcr2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern M., Voutev R., Maciejowski J., Corsi A. K. and Hubbard E. J. A. (2009). A “latent niche” mechanism for tumor initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 11617-11622. 10.1073/pnas.0903768106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner A. (2010). Epigenetic modifications in pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 1079-1088. 10.1038/nbt.1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger M. B., Hristova V. A. and Weissman A. M. (2012). HECT and RING finger families of E3 ubiquitin ligases at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 125, 531-537. 10.1242/jcs.091777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama J.-i., Xiao G., Noma K.-i., Malikzay A., Bjerling P., Ekwall K., Kobayashi R. and Grewal S. I. S. (2003). Alp13, an MRG family protein, is a component of fission yeast Clr6 histone deacetylase required for genomic integrity. EMBO J. 22, 2776-2787. 10.1093/emboj/cdg248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J., Zevnik B., Anastassiadis K., Niwa H., Klewe-Nebenius D., Chambers I., Schöler H. and Smith A. (1998). Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell 95, 379-391. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81769-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olgun A., Aleksenko T., Pereira-Smith O. M. and Vassilatis D. K. (2005). Functional analysis of MRG-1: the ortholog of human MRG15 in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 60, 543-548. 10.1093/gerona/60.5.543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo P. S., Leung J. K., Lucchesi J. C. and Pereira-Smith O. M. (2002). MRG15, a novel chromodomain protein, is present in two distinct multiprotein complexes involved in transcriptional activation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50860-50866. 10.1074/jbc.M203839200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasierbek P., Jantsch M., Melcher M., Schleiffer A., Schweizer D. and Loidl J. (2001). A Caenorhabditis elegans cohesion protein with functions in meiotic chromosome pairing and disjunction. Genes Dev. 15, 1349-1360. 10.1101/gad.192701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena A. N. and Pereira-Smith O. M. (2007). The role of the MORF/MRG family of genes in cell growth, differentiation, DNA repair, and thereby aging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1100, 299-305. 10.1196/annals.1395.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña A. N., Tominaga K. and Pereira-Smith O. M. (2011). MRG15 activates the cdc2 promoter via histone acetylation in human cells. Exp. Cell Res. 317, 1534-1540. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper A. S., Killian D. J. and Hubbard E. J. (2003). Genetic analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans glp-1 mutants suggests receptor interaction or competition. Genetics 163, 115-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phanstiel D. H., Brumbaugh J., Wenger C. D., Tian S., Probasco M. D., Bailey D. J., Swaney D. L., Tervo M. A., Bolin J. M., Ruotti V. et al. (2011). Proteomic and phosphoproteomic comparison of human ES and iPS cells. Nat. Methods 8, 821-827. 10.1038/nmeth.1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickart C. M. (2001). Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 503-533. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racher H. and Hansen D. (2010). Translational control in the C. elegans hermaphrodite germ line. Genome 53, 83-102. 10.1139/G09-090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racher H. and Hansen D. (2012). PUF-8, a Pumilio homolog, inhibits the proliferative fate in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. G3 (Bethesda) 2, 1197-1205. 10.1534/g3.112.003350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid J. L., Moqtaderi Z. and Struhl K. (2004). Eaf3 regulates the global pattern of histone acetylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 757-764. 10.1128/MCB.24.2.757-764.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rual J.-F., Ceron J., Koreth J., Hao T., Nicot A.-S., Hirozane-Kishikawa T., Vandenhaute J., Orkin S. H., Hill D. E., van den Heuvel S. et al. (2004). Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res. 14, 2162-2168. 10.1101/gr.2505604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher B., Hanazawa M., Lee M.-H., Nayak S., Volkmann K., Hofmann R., Hengartner M., Schedl T. and Gartner A. (2005). Translational repression of C. elegans p53 by GLD-1 regulates DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Cell 120, 357-368. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijen T., Fleenor J., Simmer F., Thijssen K. L., Parrish S., Timmons L., Plasterk R. H. A. and Fire A. (2001). On the role of RNA amplification in dsRNA-triggered gene silencing. Cell 107, 465-476. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00576-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. R., Cayrou C., Huang R., Lane W. S., Cote J. and Lucchesi J. C. (2005). A human protein complex homologous to the Drosophila MSL complex is responsible for the majority of histone H4 acetylation at lysine 16. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9175-9188. 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9175-9188.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasaki T., Liu Z., Habara Y., Nishiwaki K., Nakayama J.-i., Inoue K., Sakamoto H. and Strome S. (2007). MRG-1, an autosome-associated protein, silences X-linked genes and protects germline immortality in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 134, 757-767. 10.1242/dev.02771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L. and Fire A. (1998). Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature 395, 854 10.1038/27579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga K., Leung J. K., Rookard P., Echigo J., Smith J. R. and Pereira-Smith O. M. (2003). MRGX is a novel transcriptional regulator that exhibits activation or repression of the B-myb promoter in a cell type-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 49618-49624. 10.1074/jbc.M309192200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga K., Kirtane B., Jackson J. G., Ikeno Y., Ikeda T., Hawks C., Smith J. R., Matzuk M. M. and Pereira-Smith O. M. (2005). MRG15 regulates embryonic development and cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 2924-2937. 10.1128/MCB.25.8.2924-2937.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga K., Tominaga E., Ausserlechner M. J. and Pereira-Smith O. M. (2010). The cell senescence inducing gene product MORF4 is regulated by degradation via the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 316, 92-102. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Wilson-Berry L., Schedl T. and Hansen D. (2012). TEG-1 CD2BP2 regulates stem cell proliferation and sex determination in the C. elegans germ line and physically interacts with the UAF-1 U2AF65 splicing factor. Dev. Dyn. 241, 505-521. 10.1002/dvdy.23735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Gupta P., Fairbanks J. and Hansen D. (2014). Protein kinase CK2 both promotes robust proliferation and inhibits the proliferative fate in the C. elegans germ line. Dev. Biol. 392, 26-41. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood A., Krogan N. J., Dover J., Schneider J., Heidt J., Boateng M. A., Dean K., Golshani A., Zhang Y., Greenblatt J. F. et al. (2003). Bre1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase required for recruitment and substrate selection of Rad6 at a promoter. Mol. Cell 11, 267-274. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00802-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Sun X., Jing Y., Wang M., Liu K., Jian Y., Yang M., Cheng Z. and Yang C. (2012). MRG-1 is required for genomic integrity in Caenorhabditis elegans germ cells. Cell Res. 22, 886-902. 10.1038/cr.2012.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan T., Xin T., He J., Tan J., Gao Y., Feng S., He L., Zhao G. and Li M. (2013). dBre1/dSet1-dependent pathway for histone H3K4 trimethylation has essential roles in controlling germline stem cell maintenance and germ cell differentiation in the Drosophila ovary. Dev. Biol. 379, 167-181. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochum G. S. and Ayer D. E. (2002). Role for the mortality factors MORF4, MRGX, and MRG15 in transcriptional repression via associations with Pf1, mSin3A, and Transducin-Like Enhancer of Split. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7868-7876. 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7868-7876.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetka M. C., Kawasaki I., Strome S. and Muller F. (1999). Synapsis and chiasma formation in Caenorhabditis elegans require HIM-3, a meiotic chromosome core component that functions in chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 13, 2258-2270. 10.1101/gad.13.17.2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Li Y., Yang J., Tominaga K., Pereira-Smith O. M. and Tower J. (2010). Conditional inactivation of MRG15 gene function limits survival during larval and adult stages of Drosophila melanogaster. Exp. Gerontol. 45, 825-833. 10.1016/j.exger.2010.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W. and Sternberg P. W. (2006). Genome-wide prediction of C. elegans genetic interactions. Science 311, 1481-1484. 10.1126/science.1123287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]