Abstract

Introduction

A highly sensitive and specific nucleic acid test (NAT) for the blood-borne viruses human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C (HCV), and hepatitis B (HBV) is essential for the safety of blood components. Since more than 2 decades, NAT screening of blood donations has become standard in developed countries that have implemented the individual-donation (ID-NAT) and mini-pool NAT (MP-NAT) approaches. With this powerful technique, confirmation of initial reactive (IR) NAT samples becomes a challenge. Different algorithms are currently in use to eliminate false reactive results. To show that the algorithm implemented in 2007, that uses repeat testing of IR samples in duplicate runs, is a safe strategy, especially in low endemic countries, data from a 10-year experience of ID-NAT were extensively analyzed when follow-up data were available.

Methods

From July 2007 to December 2014, the Procleix Ultrio assay on a Procleix Tigris system, and from January 2015 to December 2017, the cobas MPX on a cobas 8800 platform, were used for ID-NAT screening. All IR samples were subjected to repeat testing in duplicate independent runs. Only when both tests remained negative were the products released. Donor data from the last 10 years were investigated retrospectively, looking for the reoccurrence of a reactive result in a follow-up sample. Only those donors with at least an x + 1 donation result were included for the confirmation of a false reactive result.

Results

From the 1,830,657 donations tested, 2,450 samples were IR (0.13%); only 228 were repeat reactive ([RR], 18 HIV, 61 HCV, and 149 HBV samples), and 2,222 were non-RR (0.12%). Follow-up data were available from 1,267 donors (57%) for further analysis. All except one of these donors were ID-NAT-negative in all follow-up samples. The one exception was from a donor who acquired a fresh HBV infection 10 years after the IR donation (in the x + 28 donation) and subsequently seroconverted. Subsequent serological tests from all succeeding donations (x + 1, x + 2, etc.) were negative in all the other cases, proving that no seroconversion took place after the IR ID-NAT result.

Conclusions

The algorithm to deal with IR ID-NAT donations using duplicate repeat testing is very safe and cost-effective in low-prevalence countries. There is no unnecessary destruction of blood products, no counseling of false reactive donors, and also no need to add further complexity to the screening algorithm.

Keywords: Nucleic acid test, Blood-borne viruses, Individual donations, Mini-pools

Introduction

The first blood donor screening test for any infectious disease agent to be routinely introduced was implemented in the early 1940s to detect a Treponema pallidum infection. Until the discovery and characterization of the Australia antigen (HBsAg) in 1968, no further blood donor screening test was introduced. Consequently, up to the mid-1990s, many blood products contaminated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C (HCV), or hepatitis B (HBV) were unfortunately not identified, which resulted in many infections in blood transfusion recipients. Following the AIDS scandal during which thousands of blood product recipients were infected, there has been a vast increase in specific and elaborated measures to prevent the transmission of such dramatic infectious diseases. New and highly sensitive serological and, finally, the nucleic acid test (NAT) for detecting blood-borne pathogens was developed and implemented in various formats.

A tremendous technical advancement occurred during the 1990s with the development and application of NAT technology in blood donor screening. A highly sensitive NAT for blood-borne viruses has since then become essential for the safety of blood components; for more than 2 decades, the NAT screening of blood donations has become standard in developed countries [1, 2, 3, 4]. With the later developments in sensitivity and specificity of the NAT platforms, gradually the health authorities of most Western countries have declared the technology mandatory for the release of blood products. This has coincided with the development of several CE-marked commercial NAT systems in multiplex format to detect all 3 viral genomes (HIV, HBV, and HCV) on automated testing platforms. Multiplexing the 3 major viruses on 1 commercially available, highly automated NAT screening platform has substantially reduced the workload and enhanced the throughput when compared to previous analyzer platforms. In the beginning, most countries began mini-pool NAT (MP-NAT), i.e. screening of 96–16 pooled samples. However, there was a stepwise progression to smaller pools of 6 and individual-donation NAT (ID-NAT) to enhance testing sensitivity [5].

Currently, different systems are commercially available using both the ID-NAT and MP-NAT approaches. The predominant commercially available platforms used in Europe during the last decade, are the cobas s201 and cobas 6800/8800 (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), the Procleix Tigris and Procleix Panther (Grifols, Madrid, Spain), and the autoX-System (GFE Blut, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). However, only 3 of these are suitable for the ID-NAT approach, namely, the cobas 6800/8800, Procleix Tigris, and Procleix Panther systems. Which platform and which format are used depends on the regulatory requirements of different countries, regions, or even blood transfusion services.

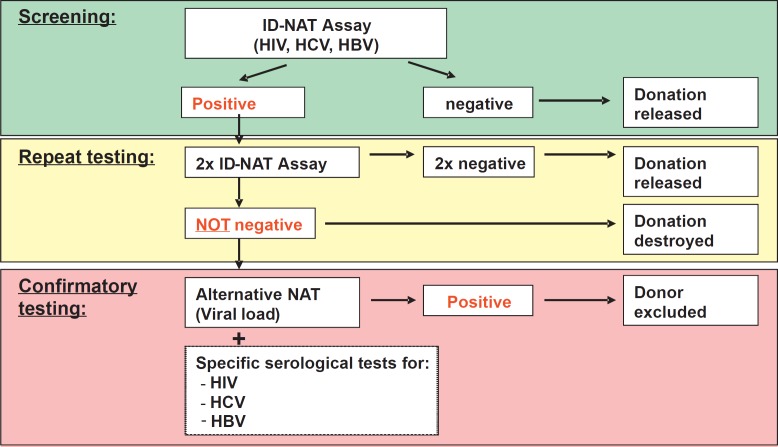

Thanks to the development of NAT technology, the safety of blood components has increased substantially. Since its introduction as a screening test, several hundred NAT-positive donations, so-called NAT yields, have been detected, thereby preventing transfusion-transmitted infections [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. However, in addition to high sensitivity, a high specificity of NAT is paramount to prevent the loss of too many valuable blood components that are destroyed as a consequence of a false-positive (FP) result. Furthermore, such FP results often lead to the avoidable deferral of otherwise eligible donors and unnecessary donor counseling. With the introduction of this highly sensitive NAT technology, 2 points therefore needed to be addressed. First, the confirmation of low-viral-load samples, and second, an adequate algorithm for the efficient delivery of blood products. In 2007, when we began ID-NAT at our institution, we defined a specific confirmation algorithm with the aim of identifying, with a high level of confidence, initial reactive (IR) donations which were FP. On the basis of the sensitivity limits and the known possibility of FP NAT, we adopted a repeat duplicate testing algorithm for the release of IR NAT donations (Fig. 1). It was our goal to identify all contaminated donations without discarding the unnecessary FP donations.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for ID-NAT screen of blood donations.

Ten years later, our algorithm is still in use. The principal specification for the testing of the blood donations in Switzerland were the sensitivity limits set by our responsible regulatory health authority, Swissmedic (ref. Therapeutic Act of Ordinance, AMBV, annex paper 812.212.1), initially set at 10,000 IU/mL for HIV-1 and 5,000 IU/mL for HCV. At that time, the Swiss authorities did not require HBV NAT. This changed in 2008, when HBV NAT was declared mandatory with a sensitivity limit of 25 IU/mL. With our NAT screening system, the Procleix Ultrio assay on the Procleix Tigris system, we achieved the following sensitivity limits: 24.9 IU/mL for HIV-1, 3.7 IU/mL for HCV, and 7.6 IU/mL for HBV. These validated sensitivity limits are thus far below the mandatory sensitivity limits set by Swissmedic. Recently, Swissmedic and the Blood Transfusion Service of the Swiss Red Cross (BTS SRC) have adopted new deferral criteria for men having sex with men (MSM), (ref. new version of the annex paper 812.212.1). The sensitivity limits were set lower than previously defined (i.e., 500 IU/mL for HIV, 50 IU/mL for HCV, and 25 IU/mL for HBV), but still greater than the level of the current validated commercial screening platform used at our institution.

To show whether our algorithm using repeat testing of IR samples in duplicate is a safe strategy to discriminate between “false” and “true” reactive results, all donors with an IR ID-NAT result were followed up over a 10-year period, and the NAT and all serological results from available follow-up donations were recorded. As presented in this study, we could show that our confirmation algorithm is safe, at least for low-prevalence countries.

Material and Methods

The ID-NAT blood donor screening started in our institution in July 2007 with the Procleix Ultrio assay on the Procleix Tigris platform. A new NAT platform was introduced at our institution in 2014, and after extensive process validation, ID-NAT screening started in January 2015 with the cobas MPX test on the cobas 8800 analyzer. Our validated viral sensitivity limits determined by probit analysis on the Procleix Ultrio assay on the Tigris system were: HBV 7.6 (95% confidence interval [CI] 6.0–11.1) IU/mL, HCV 3.7 (CI 3.1–4.8) IU/mL, and HIV-1 24.9 (CI 20.2–33.3) IU/mL. With the cobas MPX test on the cobas 8800 system, we determined the following sensitivity limits: HBV 1.1 (CI 0.81–2.0) IU/mL, HCV 8.3 (CI 5.6–20.3) IU/mL, and HIV-1 12.9 (CI 9.9–20.5) IU/mL. Noteworthy here is the improved sensitivity for HBV with the Roche cobas 6800/8800 platform. All tests were performed as described by the manufacturers' instructions.

Routine serological donor screening was performed on a Quadriga system (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany) with the Enzygnost HBsAg assay (Siemens, Marburg, Germany), the Ortho HCV 3.0 ELISA assay (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Switzerland), or the Enzygnost HCV 4.0 assay (since 2014) and the Enzygnost HIV integral assay (Siemens), according the manufacturer's instructions. Antibody testing to the hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) is not mandatory in Switzerland and was therefore not routinely performed during the blood donor screening.

Repeat reactive (RR) NAT donations were confirmed numerous times with further NAT and serological assays. A quantitative NAT assay was performed, using the corresponding real-time NAT (Abbott, Delkenheim, Germany) which has the following validated viral sensitivity limits determined by probit analysis: HBV 4.3 (CI 3.6–5.6) IU/mL, HCV 9.4 (CI 7.7–11.2) IU/mL, and HIV-1 51.8 (CI 39.5–81.2) IU/mL. At the same time, the serological status of the donor was determined using several confirmatory tests on several different platforms, in the case of an RR HBV donation, neutralization HBeAg, anti-HBc IgG/IgM, anti-HBc IgM, anti-HBe and anti-HBs “AUSAB” (Abbott) on the Abbott Axsym analyzer or, since November 2011, the Abbott Architect analyzer, respectively. For HIV1/2 RR donations, we tested anti-HIV-1/2 plus p24 Ag (BioRad, Marnes la Coquette, France) by Innolia Immunoblot (Innogenetics, Heiden, Germany). For HCV RR donations, we tested anti-HCV by Innolia Immunoblot.

Data from all the IR donors were collected in a follow-up analysis, from the first IR donation to the last donation given. The donor screening data were analyzed retrospectively for the recurrence of a reactive result in any of the follow-up donations during the last 10 years. This confirmation of an initial FP result was, however, restricted to only those donors who had donated at least once more (i.e., x + 1 donation).

Statistical differences between subgroups were analyzed using Fisher's exact test to compute p values, and Newcombe's (1998) method 10 to determine CIs the difference in proportions.

Results

Survey of All NAT Screening Platforms Currently in Use in Europe

A survey of the NAT screening platforms currently used for blood donor screening in Europe was conducted by the major commercial manufacturers, Grifols, Roche Diagnostics, and GFE Blut. At present, 24 countries in Europe perform NAT screening for the 3 major viruses HIV, HCV, and HBV using these commercial platforms. Some use an ID-NAT approach while others have implemented an MP-NAT approach with different pool sizes (Table 1).

Table 1.

The use of commercial NAT platforms in European countries

| ID-NAT | MP-NAT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grifols | ||

| Austria | – | Yes |

| Belgium | – | Yes |

| Croatia | Yes | – |

| Czech Republic | – | Yes |

| Denmark | Yes | – |

| Estonia | Yes | Yes |

| Finland | Yes | – |

| France | Yes | – |

| Germany | – | Yes |

| Greece | Yes | – |

| Ireland | Yes | – |

| Italy | Yes | Yes |

| Lithuania | Yes | – |

| Luxembourg | – | Yes |

| Netherlands | – | Yes |

| Poland | Yes | Yes |

| Portugal | Yes | Yes |

| Russia | Yes | Yes |

| Slovenia | Yes | – |

| Spain | Yes | Yes |

| Switzerland | Yes | Yes |

| Turkey | Yes | – |

| UK | – | Yes |

| Roche Diagnostics | ||

| Austria | – | Yes |

| Belgium | – | Yes |

| Germany | – | Yes |

| Greece | Yes | – |

| Hungary | – | Yes |

| Italy | Yes | Yes |

| Latvia | – | Yes |

| Lithuania | – | Yes |

| Netherlands | – | Yes |

| Poland | – | Yes |

| Portugal | Yes | – |

| Russia | – | Yes |

| Spain | Yes | Yes |

| Switzerland | Yes | – |

| UK | – | Yes |

These lists of countries that use Procleix NAT or MPX or Taqscreen MPX NAT assays, whether in individual-donation (ID) or mini-pool (MP) format, were provided by Grifols and Roche Diagnostics, respectively. They are for guidance only and are composed of unverified data not previously published. The data are on file at the sponsor companies and were obtained from a large variety of sources.

NAT Algorithm for IR NAT Blood Donations

Figure 1 describes in detail the algorithm used routinely during 10 years at our institution to deal with IR NAT results. All IR NAT samples were repeated in duplicate with the same assay, on independent runs. If both the repeated tests were negative, the blood products were released for transfusion, and the donor was eligible to provide future blood donations. When one or both of the repeated tests were again reactive, the donation was destroyed, and an alternative quantitative NAT assay was performed (Abbott real-time NAT). At the same time, the serological status of the donor was determined using several confirmatory tests on several different platforms (see Methods). If these tests confirmed a viral infection, the donor was permanently deferred.

ID-NAT Screening Data Included in the IRB Algorithm over 10 Years

From the 1,830,657 donations tested over the 10-year period, 2,450 were IR (0.13%); 1,762 (from 1,446,308 donations) were tested with the Grifols Ultrio assay and 688 (from 384,349 donations) were tested with the Roche MPX assay. The IR rates were 0.12 and 0.18%, respectively, using these 2 platforms (p = 0.000; Table 2). From the 2,450 IR donations, only 228 were RR (9.12%) and the other 2,222 were negative in all the duplicate repeat tests. The corresponding products were thus released, and so 90.7% of the IR donations did not have to be destroyed. Based on our retrospective data collected over 10 years, we show that this repeat replicate testing approach in duplicate is safe in a low-prevalence setting and minimizes the loss of otherwise usable blood products. The risk posed by releasing such blood products appears negligible.

Table 2.

NAT screening results from the Swiss blood donor population

| Grifols (Procleix Ultrio assay) | Roche (cobas MPX test) | Difference per 100,000 |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | p value | ||||

| Time period | 07/2007–12/2014 | 01/2015–04/2017 | 07/2007–04/2017 | ||

| Total donations, n | 1,446,308 (100,000) | 384,349 (100,000) | 1,830,657 (100,000) | ||

| Initial reactive, n | 1,762 (121.8) | 688 (179.3) | −72.39 to −43.30 | 0.000 | 2,451 (133.9) |

| Non-RR, n | 1,587 (109.7) | 635 (165.2) | −69.83 to −41.95 | 0.000 | 2,222 (121.4) |

| Repeat reactive (RR), n | 175 (12.1) | 53 (13.8) | −6.25 to 2.09 | 0.416 | 228 (12.5) |

From the 1,762 IR samples obtained with the Grifols Ultrio assay, 1,587 were non-RR. From the 688 IR donations obtained with the Roche MPX test, 635 were non-RR in the repeat duplicate tests performed on the respective platform (Table 2). From July 2007 to December 2014, 1,587 donations were non-RR. No splitting into HIV, HCV, and HBV was available for these samples as they were identified with the Grifols Ultrio assay. From January 2015 to April 2017, 635 donations were non-RR with the Roche MPX assay (369 HIV, 167 HCV, and 99 HBV).

The remaining 228 RR donations were confirmed positive with the official mandatory confirmation algorithm specified in Switzerland (175 identified with the Procleix Ultrio assay and 53 with the cobas MPX assay; p = 0.416; Table 3). The viral load of the confirmed positive donations was determined with the Abbott real-time NAT (data not shown). Eighteen of these donations were HIV RNA-positive, 61 were HCV RNA-positive, and 149 were HBV DNA-positive (Table 3). Of the 149 HBV DNA-positive donations, 25 were HBsAg-negative.

Table 3.

Number and virus identified for repeat reactive donations

| Grifols (Procleix Ultrio assay) | Roche(cobasMPX test) | Difference per 100,000 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | p value | |||

| Time period | 07/2007–12/2014 | 01/2015–04/2017 | ||

| Total donations, n | 1,446,308 (100,000) | 384,349 (100,000) | ||

| Repeat reactive, n | 175 (12.1) | 53 (13.8) | −6.25 to 2.09 | 0.416 |

| HIV-positive, n | 11 (0.8) | 7 (1.8) | −3.03 to 0.05 | 0.079 |

| HCV-positive, n | 48 (3.3) | 13 (3.4) | −2.60 to 1.71 | 1.000 |

| HBV-positive, n | 116 (8.0) | 33 (8.6) | −4.28 to 2.38 | 0.763 |

| HBV NAT onlya, n | 18 (1.2) | 7 (1.8) | −2.57 to 0.61 | 0.459 |

HBV DNA-positive and HBsAg-negative.

Statistically more IR NAT samples were identified with the cobas MPX assay than with the Procleix Ultrio assay (179.3/100,000 vs. 121.8/100,000 samples; p = 0.000). However, the 2 systems identified a similar number of RR NAT samples (13.8/1000,000 and 12.1/ 1000,000, respectively; p = 0.416) and no difference was seen in the viruses identified.

From the 2,222 IR but non-RR donations, follow-up data was available from 1,267 blood donors (57%) for further analysis (Table 4). The median inter-donation time for these donors was 141 days. The corresponding follow-up donations were investigated for a subsequent seroconversion or a recurring ID-NAT event. All except one of these donors remained serological and ID-NAT-negative in the follow-up samples (Table 5). The exception was a 41-year-old repeat male donor of Caucasian origin, who acquired a fresh HBV infection 10 years after his IR result, between his x + 27 and x + 28 donations, and subsequently seroconverted. As all the serological tests from the previous follow-up donations (x + 1 to x + 27) were negative, this proved that no seroconversion had taken place between his IR ID-NAT result and this later (x+28) HBV-positive donation.

Table 4.

Number of non-RR donations

| Grifols (Procleix Ultrio assay) | Roche(cobasMPX test) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | 07/2007–12/2014 | 01/2015–04/2017 | 07/2007–04/2017 |

| HIV non-RR, n | n.a. | 369 | n.a. |

| HCV non-RR, n | n.a. | 167 | n.a. |

| HBV non-RR, n | n.a. | 99 | n.a. |

| Total non-RR, n | 1,587 | 635 | 2,222 |

RR, repeat reactive; n.a., not available.

Table 5.

Tracking of follow-up donations for donors with a non-RR (repeat reactive) result

| Grifols (Procleix Ultrio assay) | Roche (cobas MPX test) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | 07/2007–12/2014 | 01/2015–04/2017 | 07/2007–04/2017 |

| Initial reactive (non-RR), n | 1,587 | 635 | 2,222 |

| Donors with available follow-up data, n | 954 | 313 | 1,267 |

| Database coverage, % | 60.1 | 49.3 | 57.0 |

| Repeatedly non-RR in follow-up, n | 954 | 312 | 1’266 |

| Donors with a reactive/unclear follow-up, n | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| False-negative rate | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

Discussion

A recent survey describing the use within Europe of the commercial NAT screening platforms from the 2 major manufacturers, Grifols and Roche Diagnostics, has highlighted how common this technology has become. Back in 2010, an international survey showed that 16 countries were using the NAT technology for the screening of blood donors [6]. Since then, many more countries have successfully integrated the technology into their blood screening programs. Currently, within Europe, 24 countries have adopted the technology, either an ID-NAT or MP-NAT approach, primarily using the Grifols and/or Roche Diagnostics NAT platforms (Table 1). In some countries, both commercial platforms and formats are used. In Germany, however, 3 of the larger Deutsches Rotes Kreuz (DRK) blood transfusion services have implemented another commercial NAT assay, the GFE Blut autoX-System, in pools of 96 donations. In other regions, the Roche Diagnostics NAT platform is used, also in 96-donation pools.

NAT technology in comparison to the serological testing approach is favored, as it is known to shorten the window period, thereby offering blood transfusion services a higher sensitivity for detecting viral infections. With the implementation of the highly sensitive ID-NAT platforms and assays, sensitivity is now often far below that required by the national health authorities. While the contemporary NAT blood donor screening assays have excellent specificity, defined as the probability of giving a negative result for donors without previous exposure to the virus in question, 100% specificity remains elusive.

FP results may theoretically arise from cross-contamination with the analyzer. However, such donations are not a major concern as the current commercial NAT systems have been extensively developed to keep such cross-contamination to a minimum. Furthermore, the algorithm presented here to release IR donations can identify most, if not all, of these FP donations due to cross-contamination. On the other hand, very-low-viral-target concentrations are a subject of this investigation, as they can be in a seroconversion period when virus concentrations may be low or from the low and fluctuating virus concentrations often present in HBV chronically infected individuals (i.e., those with occult HBV infections [OBI]). The algorithm we present with repeat testing in duplicate of IR donations has identified most, if not all, low-level virus infections. Review of the IR donors showed that none had seroconverted in the following donations, suggesting that our algorithm is safe.

The FP viral marker results in blood donors pose several challenges. For instance, informing donors of FP results and subsequent deferral, however temporary or permanent, can result in stress and anxiety for donors and lead to additional complexity and workload for the blood donor services. Therefore, donor management strategies need to balance the requirement to minimize donor anxiety and inconvenience while maintaining a sufficient supply of blood and a high level of safety.

It is essential that testing algorithms are designed to discriminate efficiently between “false” and “true” positive reactions. In centers using the MP-NAT protocol, donations implicated in the reactive pool are tested individually and nonreactive donations are released for transfusion. Because the ID-NAT approach is intrinsically more sensitive than the MP-NAT approach, there is only a small risk that a low-viral-load donation that was identified in the MP is missed in the repeat tests of the single donations. On the other hand, when the original screening is performed in ID-NAT, a repeat ID-NAT test poses a greater challenge. For this reason, many testing centers have a policy to not use IR donations for transfusion, even though it is known that the vast majority of these donations are FP. This can lead to the loss of valuable donations and needless donor deferrals, so many testing centers around the world including ours have now implemented replicate (duplicate, triplicate, or greater) repeat test strategies on the primary screening tube or sometimes from the fresh frozen plasma (FFP) collected from respective donations [5, 10]. This replicate repeat testing helps to identify low-viral-load samples which may be below the sensitivity limit of the quantitative NAT assays often used for confirmation.

ID-NAT users undergoing screening with the Grifols systems (Tigris and Panther) often perform a discriminatory test on RR samples. For the Roche platform (MPX on the cobas 6800/8800), the multidye capacity eliminates the need for discriminatory testing, but still, a repeat testing is required to discriminate between false and true IR results. Both MP-NAT resolution and replicate testing with the ID-NAT approach increase specificity but, with both strategies, it is believed that FP samples may still occur [5]. In this study, we show that duplicate testing is not only able to identify true-viral-positive donations but also eliminates FP initial screening results, and thus keeps the loss of blood products to a minimum. Similarly, in a recent report from India using a repeat triplicate testing strategy of IR donations, it was shown that the number of inconclusive results in their setting could be significantly reduced [11].

HBV, with its special course of infection, especially the OBI, makes the screening strategy for this virus not as straightforward as that for HIV and HCV. Several authors have pointed out that the blood screening for HBV often gives inconclusive results [12, 13, 14]. They argue that the cause of such questionable results is due to FP IR-NAT, OBI, or window-period donations. In a study performed on Polish donors, it was shown that from 9,980 first-time donors, the IR rate with the Ultrio Plus assay on the Tigris was 0.85, and 0.63% were RR whereas 0.22% were non-RR, and the calculated specificity of initial screening result lay around 99.77% [10]. These authors calculated a 100% specificity with a triplicate ID NAT repeat-testing strategy to eliminate discriminatory tests on false non-RR anti-HBc nonreactive donations. The specificity thus seems to depend heavily on the testing platform used.

Many blood-screening laboratories worldwide also include anti-HBc tests on both RR and non-RR samples to specifically identify OBI. Though this serological approach is not recommended by the NAT manufacturer's instructions, it is nevertheless often used, particularly in many European countries, as it is deemed to circumvent unnecessary discriminatory tests on FP ID-NAT results. For possible HBV-contaminated blood products, only HBsAg and HBV ID-NAT are mandatory in Switzerland. In contrast, however, anti-HBc, together with anti-HBs, is used in the confirmation algorithm. False reactive anti-HBc results are often known to occur because the commercial anti-HBc tests have a high sensitivity but lower specificity. For this reason, anti-HBc tests are not mandatory in Switzerland for blood screening [15]. It is, however, required in the confirmation algorithm for RR donations as follows: if the sample of a donation is confirmed RR for HBV DNA or is HBsAg-positive, then an HBsAg neutralization test is conducted, together with 2 independent anti-HBc assays. If one these markers proves conclusive, then the donor is permanently deferred. The use of 2 independent anti-HBc tests is required to circumvent the high sensitivity but lower specificity of the commercial anti-HBc assays, often leading to false anti-HBc results.

We have shown that, over the 10-year study period, the chosen duplicate repeat testing algorithm for ID-NAT resolution of IR-NAT reactive donations was safe and cost-effective in a country with a low prevalence of blood-borne infections. The 10-year follow-up of the IR-NAT donors found that none had seroconverted, indicating that our adopted strategy is safe in our blood transfusion setting. All true-positive HIV, HCV, and HBV donations were identified, all FP donations were detected, there was no unnecessary loss of blood donors and blood products, and unnecessary counseling of false reactive donors could be avoided. Our study has shown that there is no need to add further complexity to our screening algorithm.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with regard to the data reported in this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank and acknowledge Dr. Alexander Jordan from the Institute of Mathematical Statistics and Actuarial Science, University of Berne, for his help and expert statistical analysis performed on part of the data.

References

- 1.Bruhn R, Lelie N, Custer B, Busch M, Kleinman S, International NAT Study Group Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus RNA and antibody in first-time, lapsed, and repeat blood donations across five international regions and relative efficacy of alternative screening scenarios. Transfusion. 2013 Oct;53((10 Pt 2)):2399–412. doi: 10.1111/trf.12299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruhn R, Lelie N, Busch M, Kleinman S, International NAT Study Group Relative efficacy of nucleic acid amplification testing and serologic screening in preventing hepatitis C virus transmission risk in seven international regions. Transfusion. 2015 Jun;55((6)):1195–205. doi: 10.1111/trf.13024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stolz M, Tinguely C, Fontana S, Niederhauser C. Hepatitis B virus DNA viral load determination in hepatitis B surface antigen-negative Swiss blood donors. Transfusion. 2014 Nov;54((11)):2961–7. doi: 10.1111/trf.12694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lelie N, Bruhn R, Busch M, Vermeulen M, Tsoi WC, Kleinman S, International NAT Study Group Detection of different categories of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in a multi-regional study comparing the clinical sensitivity of hepatitis B surface antigen and HBV-DNA testing. Transfusion. 2017 Jan;57((1)):24–35. doi: 10.1111/trf.13819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vermeulen M, Lelie N. The current status of nucleic acid amplification technology in transfusion-transmitted infectious disease testing. ISBT Sci Ser. 2016;11(S2):123–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth WK, Busch MP, Schuller A, Ismay S, Cheng A, Seed CR, et al. International survey on NAT testing of blood donations: expanding implementation and yield from 1999 to 2009. Vox Sang. 2012 Jan;102((1)):82–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2011.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stolz M, Tinguely C, Graziani M, Fontana S, Gowland P, Buser A, et al. Efficacy of individual nucleic acid amplification testing in reducing the risk of transfusion-transmitted hepatitis B virus infection in Switzerland, a low-endemic region. Transfusion. 2010 Dec;50((12)):2695–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vermeulen M, Coleman C, Mitchel J, Reddy R, van Drimmelen H, Ficket T, et al. Sensitivity of individual-donation and minipool nucleic acid amplification test options in detecting window period and occult hepatitis B virus infections. Transfusion. 2013 Oct;53((10 Pt 2)):2459–66. doi: 10.1111/trf.12218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vermeulen M, et al. Assessment of HIV transfusion transmission risk in South Africa: a 10-year analysis following implementation of individual donation nucleic acid amplification technology testing and donor demographics eligibility changes. Transfusion. 2018 doi: 10.1111/trf.14959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grabarczyk P, van Drimmelen H, Kopacz A, Gdowska J, Liszewski G, Piotrowski D, et al. Head-to-head comparison of two transcription-mediated amplification assay versions for detection of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 in blood donors. Transfusion. 2013 Oct;53((10 Pt 2)):2512–24. doi: 10.1111/trf.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiwari AK, Dara RC, Arora D, Aggarwal G, Rawat G, Raina V. Comparison of two algorithms to confirm and discriminate samples initially reactive for nucleic acid amplification tests. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2017 Jul-Dec;11((2)):140–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.214330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlewood R, Flanagan P. Ultrio and Ultrio Plus non-discriminating reactives: false reactives or not? Vox Sang. 2013 Jan;104((1)):7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2012.01624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allain JP, Candotti D. Diagnostic algorithm for HBV safe transfusion. Blood Transfus. 2009 Jul;7((3)):174–82. doi: 10.2450/2008.0062-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiely P, Margaritis AR, Seed CR, Yang H, Australian Red Cross Blood Service NAT Study Group Hepatitis B virus nucleic acid amplification testing of Australian blood donors highlights the complexity of confirming occult hepatitis B virus infection. Transfusion. 2014 Aug;54((8)):2084–91. doi: 10.1111/trf.12556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niederhauser C, Mansouri Taleghani B, Graziani M, Stolz M, Tinguely C, Schneider P. Blood donor screening: how to decrease the risk of transfusion-transmitted hepatitis B virus? Swiss Med Wkly. 2008 Mar;138((9-10)):134–41. doi: 10.4414/smw.2008.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]