Abstract

RNA viruses synthesize new genomes in the infected host thanks to dedicated, virally-encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRps). As such, these enzymes are prime targets for antiviral therapy, as has recently been demonstrated for hepatitis C virus (HCV). However, peculiarities in the architecture and dynamics of RdRps raise fundamental questions about access to their active site during RNA polymerization. Here, we used molecular modeling and molecular dynamics simulations, starting from the available crystal structures of HCV NS5B in ternary complex with template-primer duplexes and nucleotides, to address the question of ribonucleotide entry into the active site of viral RdRp. Tracing the possible passage of incoming UTP or GTP through the RdRp-specific entry tunnel, we found two successive checkpoints that regulate nucleotide traffic to the active site. We observed that a magnesium-bound nucleotide first binds next to the tunnel entry, and interactions with the triphosphate moiety orient it such that its base moiety enters first. Dynamics of RdRp motifs F1 + F3 then allow the nucleotide to interrogate the RNA template base prior to nucleotide insertion into the active site. These dynamics are finely regulated by a second magnesium dication, thus coordinating the entry of a magnesium-bound nucleotide with shuttling of the second magnesium necessary for the two-metal ion catalysis. The findings of our work suggest that at least some of these features are general to viral RdRps and provide further details on the original nucleotide selection mechanism operating in RdRps of RNA viruses.

Keywords: RNA virus; viral polymerase; molecular dynamics; nucleoside/nucleotide transport; protein motif; RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp); Single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus; structural biology

Introduction

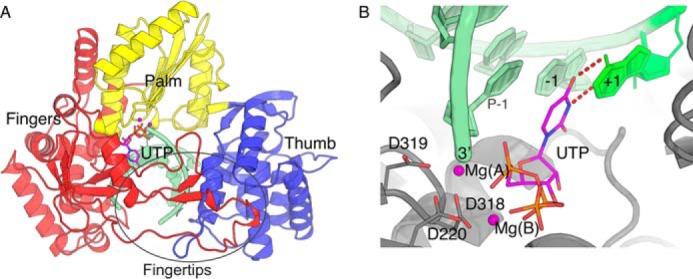

Template-dependent synthesis of nucleic acids to generate a template-complementary strand is at the heart of the transmission and expression of genetic information. Nucleic acid polymerases are those enzymes that direct such template-dependent DNA or RNA synthesis. At the most basic level, the crucial function of these enzymes is to achieve exact positioning of a nucleotide so that it may probe the next base of the template to be copied (base labeled “+1” on Fig. 1B), checking for proper Watson-Crick base pairing. The “P-1” 3′ hydroxyl of the neosynthesized nucleic acid can then attack the 5′-α-phosphate of the nucleoside triphosphate (NTP), ultimately leading to the addition of the nucleoside monophosphate and release of pyrophosphate. This chemistry step is assisted by two metal ions (normally magnesium) and this overall scheme seems general to all nucleic acid polymerases (1). In bacteria and viruses the polymerase activity may be carried by a single polypeptide chain that is necessary and sufficient for template-dependent nucleic acid synthesis. These polymerases usually only use one type of nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) as template, and synthesize only one type (DNA or RNA) complementary to the first. Atomic structures and sequence comparisons of these enzymes have shown that a very successful architecture is that initially found in the Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (a DNA-dependent DNA polymerase, or replicase) (2). This architecture (hereafter called base polymerase) has been likened to a right hand with three domains dubbed “fingers,” “palm,” and “thumb” (Fig. 1A). There are base polymerases found for all four possible activities: replicases, transcriptases (DNA-dependent RNA polymerases such as the bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase), reverse transcriptases (such as the HIV DNA polymerase), and RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp).3 In the latter two cases of RNA-dependent base polymerases, the enzymes are specific to the viral world and are prime targets of antivirals.

Figure 1.

HCV NS5B ternary complex. UTP ternary complex derived from PDB 4WTA by adding the γ-phosphate and substituting the two Mn2+ ions of the crystal structure with two Mg2+, Mg(A) and Mg(B) (in deep purple). The primer/template RNA is in pale green. A, overall view with domains fingers, palm, and thumb colored red, yellow, and blue, respectively. The two loops extending from the fingers (Fingertips) are indicated. B, close up of the active site showing Watson-Crick base pairing of UTP with the +1 template base and coordination of Mg(A) and Mg(B) by aspartates 220 (motif A) and 318–319 (motif C) and the primer's 3′-end on one side, and the UTP triphosphate moiety on the other side.

The first complete crystal structure of a viral RdRp, that of hepatitis C virus polymerase (HCV NS5B), revealed that, in contrast to other base polymerases, RdRp harbor extensions from the fingers connecting to the thumb. These “fingertips” (Fig. 1A) leave only a narrow tunnel for access of NTP to the catalytic site (3–5). Nearly all RNA viruses with no DNA stage encode their own RdRp for intracellular transcription and replication, and numerous atomic structures of these are now known. They all display this peculiar elaboration on the base polymerase-fold, whether in the 400–600–residue RdRp of single-stranded, positive sense RNA ((+)-ssRNA) viruses or in the usually larger and more complex RdRp of (−)-ssRNA viruses (such as influenza virus) (6) and dsRNA viruses (7, 8), where the fingertips may be very large.

Groundbreaking work at the turn of the 1990's identified conserved sequence motifs within the basic architecture of base polymerases, some found in all (2) and others specific to RNA-dependent polymerases (9) or more narrowly to RdRp (10). We follow here the nomenclature of Delarue and colleagues (9), extended by other authors, in labeling these motifs in alphabetical order. Thus motifs A and C (common to all base polymerases) provide aspartic acid residues that chelate the two active site magnesium ions (for HCV NS5B, Asp220 of motif A and Asp318–Asp319 of motif C, Fig. 1B). The so-called motif F is best described as a tripartite, RdRp-specific motif F1–F2–F3 (in NS5B, residues 141–144, 151–154, and 155–161) (11). It resides in the RdRp fingertips in successive circles of residues lining the NTP tunnel and increasingly distant from the active site in the order F3 < F1 < F2. F1–F3 are not as conserved in RdRp as motifs A and C. Indeed sequence divergence in these and other residues allows partitioning of (+)-ssRNA RdRp into three supergroups (10, 12). Among major pathogens, supergroup I contains the Picornaviridae (including the enteroviruses such as poliovirus, or hepatitis A virus), and Caliciviridae (including noroviruses), as well as Coronaviridae (including severe acute respiratory syndrome virus). Supergroup II contains the Flaviviridae (including among many others dengue virus, Zika virus and HCV). Supergroup III contains the Togaviridae (including the alphaviruses such as chikungunya virus and the rubella virus), as well as hepatitis E virus. Available atomic structures of complexes with template-primer nucleic acids (called binary complexes in the field) and of complexes with nucleic acids and an incoming nucleotide bound at the active site (ternary complexes) are very unevenly distributed among (+)-ssRNA RdRp supergroups. There are no structures of supergroup III RdRp (apo or complexes). Recently the structures of binary (13) and ternary (14) complexes of HCV NS5B have been the first for supergroup II. Finally, numerous crystal structures of binary and ternary complexes are available for supergroup I (e.g. Refs. 15 and 16).

Of particular interest in these supergroup I structures are those obtained in recent years for enteroviruses (17–19). Through careful tailoring of experimental conditions, Gong and colleagues (17–19) could catch incoming NTP not only at the active site but also just prior to transfer to the active site. At this stage, the NTP already base pair to the +1 template base but its triphosphate, which comes with catalytic magnesium B (Mg(B)), is not in the right place yet. Indeed, Mg(A) (Fig. 1B) does not yet reside in the active site where it is to activate the primer 3′-OH for attack of the NTP α-phosphate. In one enterovirus complex it is found instead some 5 Å away (18), at a noncatalytic site that has been reported also in other RdRp including Flaviviridae (supergroup II) RdRp (20) (and references therein). Gong and colleagues (17–19) conclude that these complexes are equivalent to the “preinsertion” state reported for the T7 RNA polymerase (21). In the present work, we extend these structural insights on nucleotide entry into RdRp through extensive molecular dynamics simulations using a variety of methods on HCV NS5B complexes.

Results

Overall dynamics of ternary and binary complexes

We took advantage of the availability of crystal structures of ternary complexes of NS5B with double-stranded primer-template RNAs and incoming nucleoside diphosphate (14) to generate the all-atom ternary system (see “Experimental procedures”): NS5B, template-primer RNA and UTP with two Mg2+, Mg(A) and Mg(B), at the active site (Fig. 1, A and B). Starting from this system, we first produced 1 μs of simulation in the forms of (i) 5 replicas of 100-ns simulations of the ternary complex and (ii) 5 replicas of 100-ns simulations of a binary complex where we kept Mg(A) at the active site but removed UTP, together with Mg(B), because it is expected to come with the incoming nucleotide (22, 23). In all 10 simulations, the systems showed several conserved properties. The first is an initial relaxation/expansion from the crystal structure conformation corresponding to an opening movement of the protein, mainly of the thumb domain. To monitor this opening we used the NS5B “interdomain angle” as defined by Davis and Thorpe (24). We find that this angle consistently goes up from some 76° in the crystal structure to around about 84° during the simulations (see Fig. S1 for the ternary complexes). In fact this initial relaxation occurs in large part during the careful equilibration protocol we used to avoid spurious breakup of contacts that we saw in initial trials. The relaxation is ended for all simulations after 10 ns and the angle then oscillates with breathing motions of the enzyme. We therefore considered the first 10 ns of simulations as pre-production.

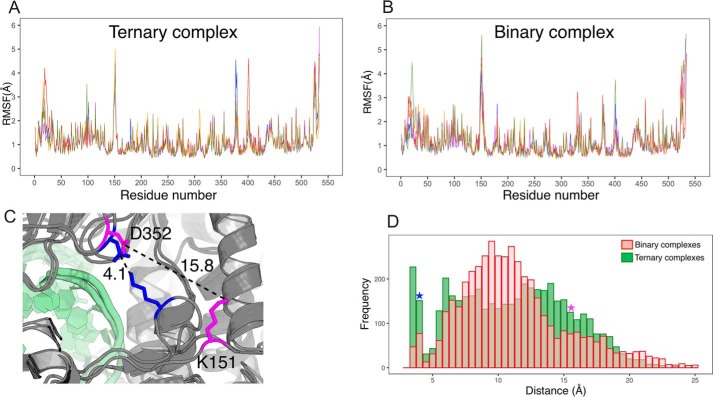

Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) increases with mobility of atoms and is a good indicator of which parts are rigid and which flexible. RMSF on all nonhydrogen atoms computed over the last 90 ns show that several NS5B internal loops are very mobile (Fig. 2, A and B). We focus on the loop in the fingertips that overhangs the NTP entry tunnel and shows a very sharp RMSF peak in all 10 simulations at residues 148–152 (RMSF peaking at 4–5 Å at residue 151 and above 2.5–3 Å over 148–152, whereas it is below 1 Å immediately upstream and downstream). In crystal structures this part (assigned by Bruenn (11) to RdRp motif F2, and hereafter called “entry loop”) is often not visible in electron density maps and hence not built in the model, suggesting dynamic disorder. However, it is present in the crystal structure we used and our simulations show that it does stabilize at times in several defined positions. This is best illustrated by the distance between Lys151 Nζ and Asp352 Cγ on the other side of the NTP tunnel next to motif D (Fig. 2, C and D). The very wide distributions (from below 3.5 to 25 Å) show several peaks that correspond to alternate salt bridges made by Lys151. The dynamics of the entry loop thus allow it to stably sample “closed” conformations (including one where Lys151 and Asp352 make a salt bridge, bisecting the NTP tunnel entry in two) to “open” conformations (including one where the entry loop sticks out from the protein, Fig. 2C). When we remove UTP and Mg(B) (binary complex), the mobility of the entry loop increases and the distribution of distances is shifted as the loop tends to sample more the open conformations and less the closed ones (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Molecular dynamics simulations of HCV NS5B ternary and binary complexes. A and B, RMSF along the NS5B sequence for five replicas of 100-ns simulations of NS5B ternary complex (A) and binary complex where UTP and Mg(B) were removed (B). The last 90 ns of the simulations were considered. C, two snapshots of alternate conformations of the entry loop taken from simulations of binary complexes. Lys151 in the loop is displayed, as well as Asp352 on the other side of the NTP tunnel with which Lys151 makes a salt bridge in the closed entry loop conformation (residues in blue), whereas the two side chains are far away in open conformations (residues in magenta). D, distributions of the distance between Lys151 Nζ and Asp352 Cγ in binary complex simulations (transparent red histogram) and ternary complex simulations (green histogram). The blue and magenta stars signal the value for the closed and open entry loop conformations, respectively.

NS5B residues interfering with access to and egress from the active site

In base polymerases, the NTP tunnel is RdRp-specific (see “Discussion”) and how nucleotides shuttle through it has been an almost completely unaddressed question. We therefore set out to explore how the UTP could enter the NS5B NTP tunnel and reach the active site. As a starting approach to locate residues likely involved during NTP entry, we first placed the UTP with Mg(B) at the tunnel entry 40 Å from Mg(A), which we kept at first at the active site. We then used biased MD protocols to direct UTP toward the active site.

Targeted molecular dynamics simulations on 4 systems (2 UTP orientations × 2 loop conformations)

We first used targeted molecular dynamics simulations (TMD). For the starting point we chose the side of the larger opening remaining when Lys151 forms a salt bridge to Asp352 (Fig. S2, panels 1 and 2). We denote this side as “Asp387 side,” whereas the other side is “Lys51 side.”

In TMD an extra energy term is added that depends on the differences between a set of atoms in the simulated system and the same set in a reference, target system. In all cases the target system was our initial, energy minimized and equilibrated ternary complex system. The difference between the simulated and target systems was computed as the root mean square deviation (RMSD) between UTP in the simulated system and UTP in the target system. The extra energy term increased with the square of RMSD, thus pushing UTP toward its position and orientation in the ternary complex. Mg(B) was not included in the RMSD target, but still remained associated with UTP in all simulations. In view of the previous results, we tried two starting NS5B conformations, one with the entry loop closed and the other open (Fig. 2C, Fig. S2). These conformations were chosen by clustering of the entry loop conformations in the 5 binary complex simulations using our in-house clustering utility TTClust (25). The corresponding Lys151–Asp352 distances are indicated in Fig. 2C. We also used two different UTP orientations at the tunnel entry, “base oriented” (Fig. S2, panels 1 and 3) and “triphosphate oriented” (Fig. S2, panels 2 and 4).

In all 4 systems UTP enters the tunnel up to a point, then is checked in its progression (Fig. S3 for the closed entry loop, UTP base-oriented case). The main contribution to this check seems to be RdRp motif F3's Arg158, whose side chain keeps UTP out of the active site. Increasing the constant to 0.1 Kcal/mol/Å2 allows UTP to finally pass the Arg158 block, pushing aside the Arg158 side chain. Even after this forced passage, UTP is not correctly inserted in the active site and neither makes a Watson-Crick bp to the template +1 adenosine nor has its α-phosphate coordinating Mg(A).

Steered molecular dynamics simulations of the base-oriented systems

Steered molecular dynamics (SMD) is a complementary method to the previous TMD to investigate incoming UTP at the active site. To better assess how Arg158 interferes with the establishment of base pairing to the template RNA we performed 30 SMD, most on the open entry loop (initial UTP orientation) and a few on the closed entry loop (initial UTP orientation) systems. During the SMD simulations, a time-dependent external force is applied between two selected atoms (or group of atoms) to define the direction forcing the UTP to move from its initial position to the target position (a straight-line in this case). Parameter values were varied for the velocity constant, the atoms on which the force was applied, and the force constant. In all cases, from the entrance of the tunnel to Arg158, the progression of the nucleotide is progressive and continuous. Then the nucleotide abuts on the salt bridge between Arg158 and Glu143 of motif F1 and at that moment we observe four scenarios (Fig. S4, panels A, B, C, and D, respectively). 1) The progress of the nucleotide is stopped (panel A). 2) The salt bridge Arg158–Glu143 breaks off before the nucleotide arrives, clearing the passage to the template +1 adenosine. 3) The nucleotide passes next to the salt bridge but is poorly positioned to reach the base to be interrogated. 4) The nucleotide goes under the salt bridge and can reach the template strand. We could obtain all four scenarios with both conformations of the entry loop and similar work was required for the UTP trajectories. Interestingly, in scenario 2, the salt bridge Arg158–Glu143 breaks, whereas the incoming UTP is far, about 36 Å from its target (Fig. S4B, right panel). This is because Glu143 can form a salt bridge with Lys141, whereas Arg158 interacts with the template +1 adenosine (π-cation interaction). These results further highlight Arg158 in motif F3 and more precisely its salt bridge with Glu143 in motif F1 as a possible dynamic checkpoint in nucleotide entry.

Nucleotide interactions once at the active site: a locked down UTP

In view of this, we examined the behavior of Arg158 in the ternary complex, once UTP has entered the active site. In the initial PDB code 4WTA, Arg158 is sandwiched between Glu143 and UTP and makes two stable interactions with the latter. It establishes on the one hand a salt bridge to the α-phosphate and on the other hand a cation–π interaction with the base. In our 5 unbiased simulations of ternary complexes, these contacts are maintained throughout, as well as Watson-Crick interactions of the UTP base with the +1 template adenine (>70%) and classical Mg2+-mediated electrostatic interactions on its triphosphate side. Only ribose interactions with the protein are dynamic, with the 2′-OH environment being particularly labile on one side. These observations highlight a locking down of the active site after nucleotide insertion where Arg158 contributes to keeping in place triphosphate and base moieties, whereas the ribose moiety is more loosely bound.

Exit TMD

To further probe this locking down, we also performed reverse TMD from the ternary UTP complex (not shown). Thus we used as target system the initial ternary complex system and as target RMSD at 30 Å instead of 0 to push UTP out of the active site. With a constant of 0.01 Kcal/mol/Å2, UTP does not budge from the active site (final RMSD of about 2 Å). Increasing the constant to 0.1 Kcal/mol/Å2 finally pushes UTP out of the active site (final RMSD goes above 20 Å). However, UTP does not then pass Arg158 to go to the NTP tunnel but pushes aside the −1 template-primer bp and the surrounding protein. The two magnesium ions remain attached to the triphosphate moiety and pull along the three coordinating aspartates: Asp220, Asp318, and Asp319.

A minimally biased approach of the NTP tunnel: distance-restrained MD from “open entry loop”

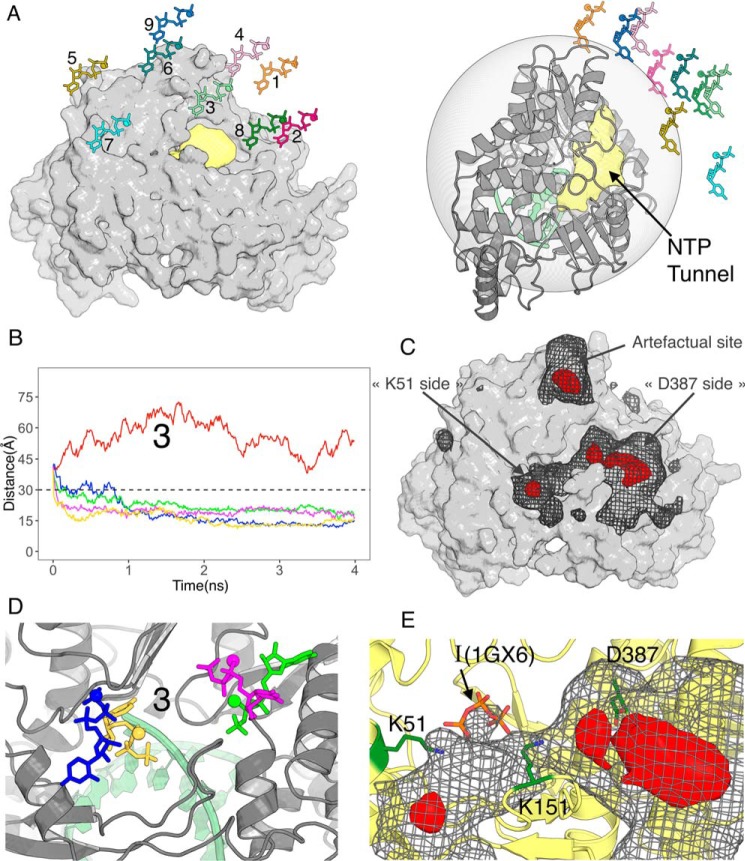

Having found a likely checkpoint along the NTP tunnel, we next searched how an incoming nucleotide would actually approach the tunnel. For this we did not use targeted or steered MD, as they introduce important biases. For instance in TMD, “large” conformational changes, which reduce most the target RMSD, are strongly biased to occur first (26). In the case of UTP entry this means that translation in a straight line toward the target position will tend to occur first. The starting nucleotide position is therefore very important as the nucleotide may be on an improper pathway and/or become trapped in an improper orientation. There may also not be enough time for the protein to adjust to the nucleotide's presence. Therefore we designed minimally biased MD protocols to explore both translational and rotational components of diffusion of UTP at the NTP tunnel entry. We started simulations from 9 initial UTP positions with centers of masses 40 Å from Mg(A). The positions (labeled 1–9 on Fig. 3A) were chosen to cover the space outside the NTP tunnel, with position 1 corresponding to the starting point of TMD (see above). In view of our previous results we selected as initial NS5B conformation one that is typical of an open entry loop in binary complexes after clustering of the trajectories (Fig. 2, C and D). We only biased the dynamics by adding a harmonic energy term when the distance to Mg(A) is more than 30 Å (Fig. 3A, right panel) with 5 energy constants 0 (no bias)/0.02/0.05/0.1/0.5 Kcal/mol/Å2. Four ns were sufficient for UTP to settle on the protein in most of the 45 simulations (Fig. 3B, Fig. S5). Visual examination of the trajectories shows that with these protocols, UTP indeed samples many orientations before coming to the protein's surface, as is apparent also from the variety of final orientations that may be reached from the same starting point (e.g. Fig. 3D). Interestingly, in many cases the UTP distance to Mg(A) converges below 30 Å, where no restraining force is applied any longer. This is particularly apparent for starting position 3 (Fig. 3B), but for 8 of 9 starting positions at least one simulation displays this behavior, sometimes even with no force applied at any point (red curves).

Figure 3.

Molecular dynamics simulations with distance restraints on UTP. NS5B is in the same orientation in panels A, left, and C–E. A, nine initial positions for UTP (together with Mg(B)) 40 Å from NS5B's active site on the side of the NTP tunnel (in pale yellow). The semitransparent gray sphere on the right panel signals the 30 Å distance from the active site under which no extra energy term is added. B, UTP distances from the active site during five 4-ns simulations starting from position 3 and with five energy constants of 0 (no bias, red curve), 0.02 (blue), 0.05 (green), 0.1 (magenta), and 0.5 (yellow) Kcal/mol/Å2. C, UTP density when considering the 45 4-ns simulations (nine initial positions times five energy constants) simultaneously, contoured at two levels to highlight regions of nucleotide binding (gray mesh) and more localized binding sites (red volumes). D, the four stable positions reached by UTP from initial position 3, colored according to the energy constant applied beyond 30 Å. E, close up of the density at the NTP tunnel entry also showing the locations of Lys51, Lys151, and Asp387. I(1GX6) is the triphosphate for the UTP at the “I” site reported previously (27).

To quantify and visualize regions where UTP accumulates, we computed a density map of UTP in all 45 simulations (Fig. 3C). A prominent apparent accumulation site lies at a surface pocket on the outside of the palm domain. We dismiss this site as artifactual because it is actually contributed to only by simulations from position 9, the only starting position where UTP never goes much below 30 Å from Mg(A) (Fig. S5). Clearly the restraint force is what traps UTP there. The relevant features of the map show that UTP goes preferentially to the entry of the NTP tunnel. We can thus define for NS5B a “capture cone,” one limit of which is position 9, which extends from the NTP tunnel and in which nucleotides will tend to bind at the tunnel's entry.

Contouring the map at a higher level (red density), we find two locations on either side of the entry loop. A fairly wide density at 20–25 Å lined on one side by residue Asp387 and a more sharply localized one at 15 Å near Lys51, corresponding to the two distance plateaus below 30 Å that may be reached by UTP (e.g. Fig. 3B). Both densities are contributed to by nucleotide poses where the triphosphate (still with its Mg(B)) makes most interactions to the protein, whereas the ribose and base may be oriented in several directions but generally point outside the NTP tunnel. Indeed the end points from starting position 3 sample these positions and orientations and are shown on Fig. 3D. Replicating some of the calculations (not shown) we found that UTP could end up from the same initial position and with the same restraint force either on the same side of the entry loop but in a different orientation, or on the other side of the entry loop. We next tried to extend simulations beyond 4 ns (not shown). After 13 ns we found that the nearer positions (15 Å) had remained stable once reached, whereas the farther (20–25 Å) generally had not. Indeed in one case UTP had gone from a farther to a nearer position within the initial 4-ns simulation (Fig. S5, position 8, blue curve). Interestingly, the part of the 15 Å density closest to the active site overlaps with the “interrogation (I) site” (Fig. 3E) that was previously identified as a site that bound NTP by their triphosphate with ribose and base crystallographically disordered (27). From these observations, we conclude that this region likely represents the end of the capture cone and that nucleotides will tend to funnel toward it, albeit in an undefined orientation.

The NTP tunnel entry is a nucleotide orientation location

We reasoned that the next step in nucleotide entry either occurred at a much larger time scale than a few nanoseconds or depended on an extra trigger. An obvious one is the magnesium Mg(A). Indeed, in crystallographic structures of RdRp, Mg(A) is seen at the active site only with the fully inserted nucleotide, i.e. in ternary complexes. However, in some cases a “noncatalytic ion” site has been reported 5–7 Å away from the catalytic site, as measured after superimposition of the RdRp backbones. The hallmark of this noncatalytic site is that the counterpart of NS5B Asp319 is part of the Mg2+ coordination sphere but is flipped away from the 3′ end of the RNA primer (Fig. 1B) and toward the NTP tunnel (Ref. 20, and references therein). The recent work by Gong and colleagues (17, 18) has shown that Mg(A) may be located at this noncatalytic site during nucleotide entry. Therefore, on the one hand we used accelerated molecular dynamics (aMD), a technique for exploring the conformational space of biomolecules that accelerates the state to state evolution of a system relative to normal molecular dynamics (28). On the other hand, we considered several hypotheses as to the location of Mg(A) during the initial steps of nucleotide entry, either at the noncatalytic position or missing altogether.

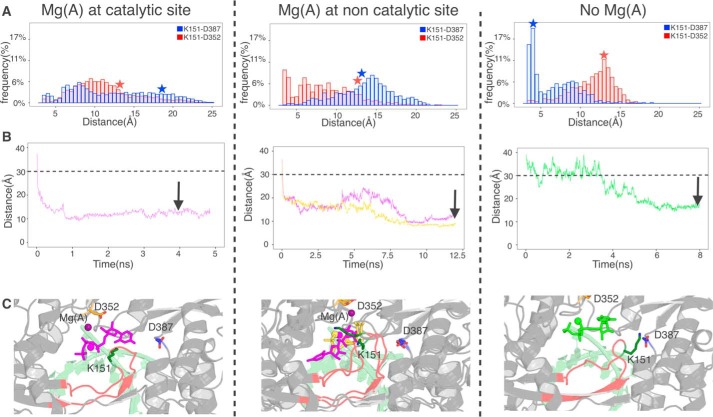

Simulations of binary complexes with Mg(A) at noncatalytic position or missing, and subsequent distance restrained MD (drMD)

First we ran preparatory simulations of binary complexes as our previous ones (Fig. 2, B and D) but now with Mg(A) either at the noncatalytic site (Fig. 4A, middle) or removed altogether (Fig. 4A, right). Mg(A) was as stable at the noncatalytic site as at the catalytic site over 100 ns. We found that the mobility of the entry loop was much affected, as is evident in the Lys151–Asp352 distance distribution (Fig. 4A, red histograms). Contrary to our expectations, in the case of Mg(A) at the noncatalytic site the two extra positive charges near Asp352 actually increase the frequency of the Lys151–Asp352 salt bridge (i.e. of the closed entry loop conformation). Also unexpectedly, the absence of any Mg(A) quickly induces a particular, retracted conformation of the loop where it establishes several salt bridges including Lys151–Asp387, a conformation that is at best very minor in the other two kinds of simulations (Fig. 4A, blue histograms). We performed new drMD with UTP (and Mg(B)) starting from position 3 (Fig. S6), using this “retracted loop” conformation for systems with no Mg(A) and an open loop conformation for systems with Mg(A) at the pre-catalytic position (Fig. 4A, stars). The results were qualitatively similar to those with Mg(A) at the catalytic site, in that UTP bound stably at the entry of the NTP tunnel in the same general places and also in a variety of orientations, but there were differences in details. Generally simulations took longer to converge and reached slightly different positions, as evidenced by the distances between the UTP center of mass and residue 319 of motif C (Fig. 4B) and by examination of the positions after convergence (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Simulations for alternate hypotheses as to Mg(A) prior to UTP approach at the catalytic site (left), at the noncatalytic site (middle), and not present (right). A, simulations of binary complexes under the three hypotheses. Displayed are distance distributions between Lys151 Nζ and Asp352 Cγ (red histograms) and Lys151 Nζ and Asp387 Cγ (blue histograms). Red and blue stars denote the single conformation that was used in each case for downstream distance-restrained MD. B, selected simulations from the initial position 3 with distance restraints between the centers of masses of UTP and Asp319, chosen this time for location of the active site. The color code for the curves is as described in the legend to Fig. 2B and the distance of 30 Å below, which no extra energy term is added is indicated. Arrows denote the snapshots from which further simulations were performed (see Fig. 5). C, stable positions reached by UTP in the indicated snapshots.

Spontaneous nucleotide orientation observed by accelerated molecular dynamics

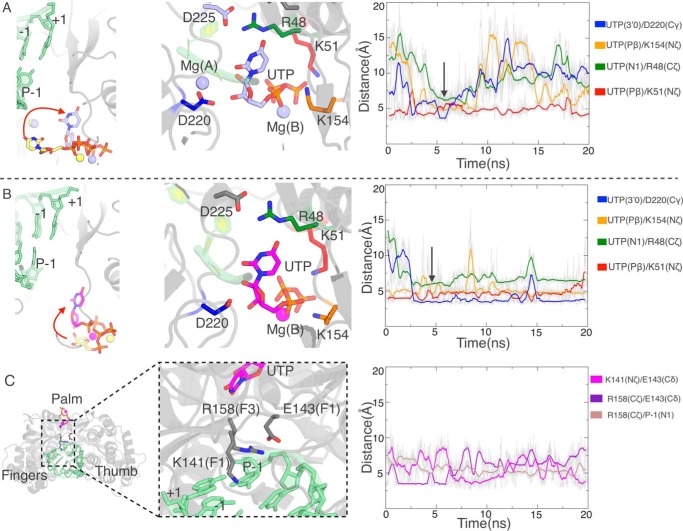

Next we performed accelerated molecular dynamics simulations from positions shown in Fig. 4, B (arrows) and C. With Mg(A) at the catalytic position or with no Mg(A) we find that UTP flips to insert its base moiety into the NTP tunnel, pointing toward the RNA template (Fig. 5, A and B). This movement can be followed by monitoring the distance between the base N1 and Arg48 Cζ (Fig. 5, A and B, right panels, green curves), as the Arg48 side chain lines the side of the tunnel, interacting at this point with Asp225 of motif A. Early in aMDs this distance drops to a plateau of 6 Å, a feature that follows soon after establishment of interactions of Asp220 also in motif A with the ribose moiety (Fig. 5, A and B, blue curves). The details of interactions are different, with the nucleotide bound much more stably when no Mg(A) is present. Close examination of the trajectories shows that in this case, all three nucleotide moieties interact strongly with the NS5B conserved residues, as the triphosphate moiety is pinched between Lys51 at the tunnel entry (red curve) and Lys154, positioned on the other side in the “retracted entry loop” conformation (orange curve). Only the first interaction is established in the “open entry loop” conformation of the system with Mg(A) at the catalytic site. As to the case of Mg(A) at the noncatalytic site, the nucleotide does not flip toward the template RNA at all (Fig. S7), although we tried either initial base orientation (Fig. 4C, middle) and in both cases the nucleotide base samples several positions and orientations. The problem seems to be that with Mg(A) stably bound at the noncatalytic position, the triphosphate moiety establishes many strong interactions when the nucleotide binds more deeply in the NTP tunnel (Fig. 4B, middle), whereas the Lys154–Lys51 pincer of the case with no Mg(A) allows much more rotational freedom.

Figure 5.

Accelerated molecular dynamics simulations show spontaneous UTP orientation at the NTP tunnel entry. A, in the case of Mg(A) at the catalytic site. B and C, in the case of no Mg(A) in the system. A and B, left panels, positions of UTP at the different starts of the two accelerated simulations and at the (transiently) stable same position (shown by the arrow in the right panels). Middle panels, details of key residues lining the UTP triphosphate, ribose, and base. Right panels, evolution of relevant distances between those residues and UTP during the simulations. C, concerted shift in motifs F3 and F1 following UTP orientation. The distances in the right panel record the closing of Arg158 with the P-1 base and the switch in salt bridges from Arg158–Glu143 to Glu143–Lys14.

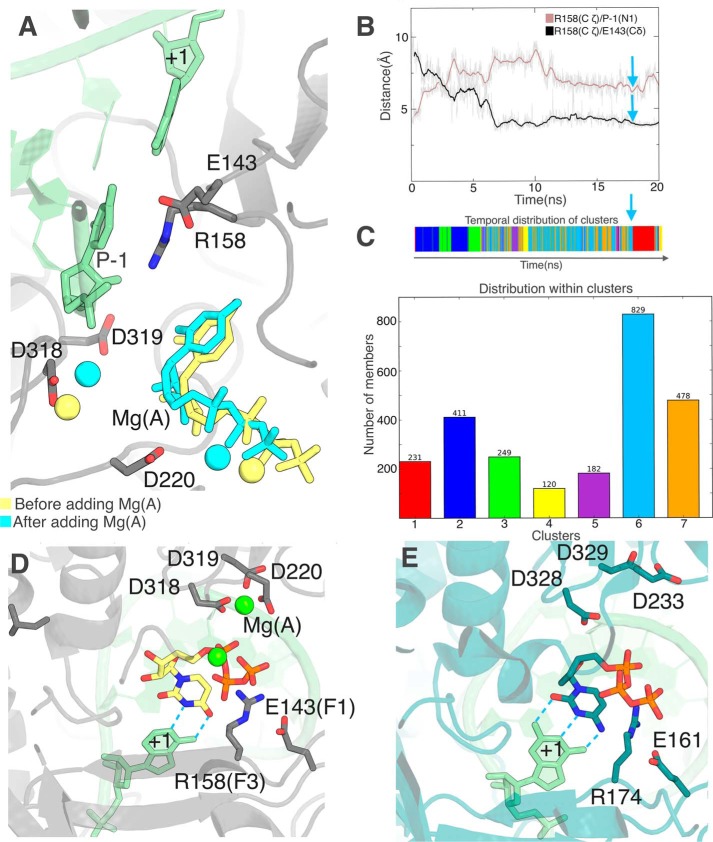

Mg(A)-dependent unmasking and initial base pairing of the +1 templating base

In view of these results, we continued with the system with no Mg(A). Extending the aMD did not lead to further progress of the nucleotide toward the template RNA. Indeed at this stage we find the check by Arg158 that we noted in directionally biased simulations (TMD and SMD, see above). It is all the more prominent here that, when the nucleotide flipped, the Arg158 side chain broke its salt bridge to Glu143 and moved to a position where it stacks against the −1 base of the primer strand, i.e. right between the +1 template base and the nucleotide base (Fig. 5C). We noted in simulations of binary complexes that the presence and location of Mg(A) affected the dynamics not only of the entry loop (Fig. 4A), but also of Arg158 (not shown). We therefore tried adding Mg(A) at the noncatalytic site and performed a subsequent 20-ns simulation (Fig. 6, A–C). The main effect is a large increase in the dynamics of motif F3 (Fig. 6, B and C). Initially Arg158 Cα moves away from the primer's 3′ end by 2.3–2.6 Å, followed by successive changes in side chain rotamers and interactions to Glu143 that break the Arg158 side chain contact with the P-1 base (Fig. 6B). Arg158 then cycles between two major conformations (Fig. 6C, 6 and 7). Compared with 7, 6 seems stabilized by the UTP base being sandwiched between Arg158 and Arg48, with Arg158 itself stabilized by its salt bridge to Glu143. We performed targeted MD simulations from this conformation with the same parameters as described previously (Fig. S3, orange curves). This time, however, the Arg158 guanidinium group moved readily around the UTP base to reach the α-phosphate, allowing pairing with the +1 base (Fig. 6D), in striking similarity to the poliovirus RdRp preinsertion complex (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6.

Addition of Mg(A) at the noncatalytic site triggers a displacement of motif F3 unmasking the +1 base. A–C, unbiased simulation after Mg(A) addition. A, initial UTP and Mg(A) positions (yellow) superimposed on the snapshot (cyan) defined by cyan arrows in B and C. The P-1 primer base on which the incoming nucleotide is to stack and the +1 adenine with which it is to bp are labeled. B, evolution of the same Arg158 distances as in Fig. 5C show a reversal of Arg158 interaction with base P-1 as the salt bridge with Glu143 is re-established. C, clustering of the Arg158 conformation along the trajectory with a timeline (top) and a distribution of clusters (bottom). The representative snapshot from the major cluster 6 used for A is indicated by the cyan arrow. D, after targeted molecular dynamics (see text for details), base-pairing with the template base (labeled “+1”) is readily established. E, the same view for the preinsertion complex crystal structure for the poliovirus RdRp obtained with a 2′,3′-ddCTP (PDB 3OLB) (17) is shown for comparison with D.

GTP entry with C as +1 base can be recapitulated as UTP's with A as +1 base

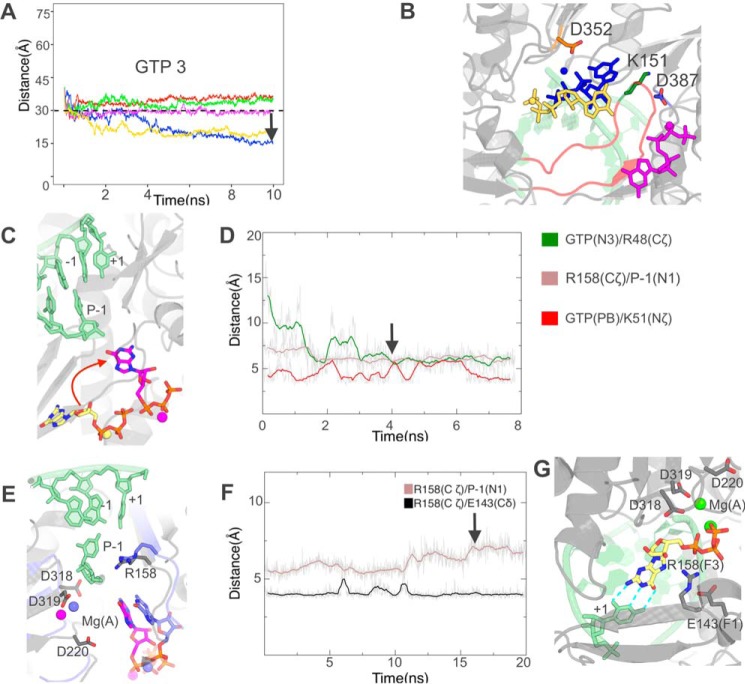

Having found a likely path through the NS5B NTP tunnel for UTP, we sought to check the generality of our observations by using the same procedures with another NTP. We chose GTP, a purine, as a more trying test with the larger guanine base size.

We generated a system identical to the one in Fig. 4A, right, namely with no Mg(A) and a retracted NS5B entry loop, but with GTP as entering nucleotide starting from position 3 and C as +1 base. Distance-restrained MD (Fig. 7, A and B) shows the retracted loop conformation also allows GTP binding at the tunnel entry in several conformations, although at only one site (likely due to the larger base size) and with differences in details. As with UTP, aMD then allows nucleotide orientation (Fig. 7C) thanks to interactions of the triphosphate with Lys51 and its base with the tunnel's side (Fig. 7D), which rearranges similarly with a salt bridge between Arg48 and Asp225. Again details differ, most obviously as the guanine base and ribose are almost at a right angle to UTP's in the former system. Still adding Mg(A) at this stage also has the effect of increasing dynamics of Arg158 leading to unmasking of the +1 base (Fig. 7, E and F). The set of Arg158 interactions, however, is different from the former case of the UTP system with A as +1 base, as is readily apparent from the lack of exchange of the Arg158–Glu143 salt bridge (compare Fig. 7F with Fig. 6B). Although a major conformation of Arg158 again emerges, it is not the same as found in the former system. Still, TMD from this major conformation also leads to Watson-Crick base pairing with the +1 C and to Arg158 binding the α-phosphate, constitutive of RdRp preinsertion (Fig. 7G).

Figure 7.

GTP entry with a cytosine as the +1 base occurs through successive steps similar to those as UTP entry with an adenosine as +1 base. A and B, molecular dynamics simulations with distance restraints between the centers of masses of Asp319 and GTP starting from position 3. A, evolution of GTP distances from Asp319 during five 10-ns simulations with five energy constants 0 (no bias, red curve), 0.02 (blue), 0.05 (green), 0.1 (magenta), and 0.5 (yellow) Kcal/mol/Å2. The distance of 30 Å below which no extra energy term is added is indicated. The black arrow denotes the snapshot that was selected for further simulations. B, the three stable positions closest to Asp319 reached by GTP from initial position 3, colored according to the energy constant applied beyond 30 Å. C and D, accelerated molecular dynamics simulations show spontaneous GTP orientation at the NTP tunnel entry. C, positions of GTP at the start of simulations (yellow carbons) and at a stable position reached in two of five replicas (magenta carbons). D, evolution of relevant distances between GTP and residues lining the NTP tunnel in one such simulation. The black arrow denotes the snapshot that was selected for further simulations. E and F, simulation after addition of Mg(A) at the noncatalytic site. E, initial GTP position (magenta carbons for GTP and Arg158) superimposed on the snapshot (purple carbons) defined by the arrow in F. F, evolution of the same Arg158 distances as in Fig. 6B also show a reversal of Arg158 interactions with base P-1 unmasking, this time with no change in the interaction with Glu143. The black arrow denotes the snapshot that was selected for further simulations. G, after targeted molecular dynamics simulations, GTP preinsertion is established.

GTP entry with a +1 base A mismatch

Finally, we sought to find out which of the above-mentioned differences were due to a different +1 base and which to a different entering nucleotide, and to assess how NS5B would discriminate a Watson-Crick mismatch. We thus performed the same successive steps for a system with A as +1 base and with GTP, allowing comparison with both previous systems (Fig. S8). We found the same behavior for GTP in the early binding and orientation steps. After these two steps GTP are superimposable regardless of the +1 base. In contrast, the dynamics of Arg158 were dependent on the +1 base. They were identical to the system with UTP and A as +1 base, before and after Mg(A) addition (e.g. compare Fig. S8F to Fig. 6B). This resulted in the same major Arg158 conformation after Mg(A) addition. TMD from this conformation did not allow GTP to pass Arg158 with the same force constant (0.05 Kcal/mol/Å2) as the one applied for the previous GTP TMD. The G and A bases remained apart (Fig. S8G). Further increasing the force constant was necessary to bring the bases within hydrogen bonding distance, but even then Arg158 did not come around to contact the GTP α-phosphate.

From all this we conclude that GTP may come up to base orientation into the NTP tunnel but will not in general reach preinsertion even with an available Mg(A) if the +1 base is A. On the other hand, Mg(A) is sufficient for +1 base unmasking by Arg158. The atomic details of Arg158 dynamics depend on the nature of the +1 base. Thus Arg158 seems to be an integral part of nucleotide selection by Watson-Crick base pairing.

Discussion

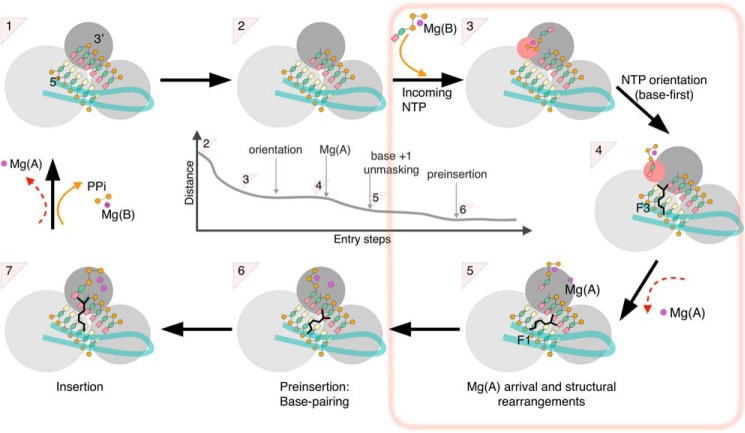

The nucleotide addition cycle of base polymerases involves several crucial steps. Starting from the product state of the preceding addition (step 1 in Fig. 8), the template-primer nucleic acid must translocate (1 to 2) to allow subsequent probing of the template +1 base by incoming nucleotides (step 6), transfer to the active site proper (6 to 7) and the chemistry step with release of pyrophosphate (7 to 1). In all base polymerases except RdRp (i.e. in replicases, transcriptases, and reverse transcriptases), a large movement (typically a 20° rotation) of the fingers domain occurs between steps 2 and 7 as the fingers close in on the correct incoming nucleotide. The structure of the preinsertion complex (step 6) of the T7 RNA polymerase (a transcriptase) shows that this occurs essentially between steps 6 and 7 (21). Biomolecular simulations have proved extremely helpful in complementing the wealth of structural and biochemical data on base polymerases. For instance, pyrophosphate release was found thereby to be largely independent of the structural changes associated with fingers reopening and translocation in the T7 RNA polymerase (i.e. 1 and 2 in Fig. 8 are distinct states) (29). This finding is consistent with the emerging picture that catalysis and translocation are actually uncoupled in base polymerases including RdRp (30). Similarly, simulations with ribonucleotide or antiviral ribonucleotide analogues at the active site of the mitochondrial RNA polymerase allowed computing differences in affinity that match experimental differences (31).

Figure 8.

Overall scheme of nucleotide entry in RdRp. The new findings of the present work (from step 2 to step 6) are boxed. Crystal structures are available for a number of (+)-ssRNA RdRp of supergroup I and for HCV NS5B (supergroup II) for steps 1 (product state/pre-translocation) and 7 (ternary complex). Crystal structures for step 4 (post-translocation) are available only for supergroup I RdRp, and for step 6 (preinsertion) only for two enteroviruses (supergroup I). The RdRp domains are represented as three gray spheres (dark, palm; middle gray, fingers; light gray, thumb) with the entry loop of the RdRp-specific fingertips in pale green. The dsRNA is represented with yellow bases for template and salmon bases for primer. The central panel depicts the general reduction of distance between the base of the incoming nucleotide and the +1 base from the first nucleotide capture (2 to 3) to preinsertion (5 to 6), where Watson-Crick base pairing is established. Note that the actual values in early stages differ in different simulations and only converge at orientation.

Still there is next to no data on the path followed by nucleotides to access the active site after translocation. This may not be a large issue for non-RdRp base polymerases, whose active sites are readily accessible before fingers closing. But the RdRp fingers remain closed throughout the nucleotide addition cycle. This begs the question of how NTP access the active site through the restricted NTP tunnel and what quality checks they encounter. Here we trace the path of incoming UTP and GTP to the cognate +1 base of the template RNA for hepatitis C virus RdRp NS5B using a variety of biased and unbiased molecular dynamics simulations methods. We find that once the nucleotide together with an associated Mg2+ Mg(B) enters a cone extending from the entry of the NTP tunnel, it is attracted to the tunnel entry (Fig. 8, steps 2-3). The interactions leading to this binding are mostly electrostatic and involve the triphosphate moiety (step 3). At a longer time scale, the ribose and base spontaneously reorient and UTP or GTP enter the NTP tunnel base first (step 4). This necessary step is thus achieved well upstream of base pairing by the organization of the tunnel entry at this stage. Indeed, it is observed identically when the +1 template base is mismatched with the entering nucleotide. A major determinant of this organization is a mobile entry loop harboring what has been termed “motif F2” (11). Lys151 in F2 may form alternate salt bridges to Asp352 on the other side of the tunnel, or to Asp387 on the same side, stabilizing the entry loop in opposite conformations and consequently making up alternate and very different tunnel entries.

These entry loop conformations, the preferential nucleotide-binding positions, and the subsequent nucleotide reorientation are all strongly affected by the presence and location of magnesium ion Mg(A). Thus the tunnel entry is widest and UTP reorients most easily and stably when no Mg(A) is present in our simulations. Furthermore, in this case GTP also binds and reorients at the tunnel entry despite its larger size. On the other hand, further progress toward the active site after nucleotide reorientation depends on Mg(A) arriving at the RdRp noncatalytic site (Fig. 8, 4–5). Gong and colleagues (17, 18) showed for the enterovirus RdRp that the movement of Mg(A) from the noncatalytic to the catalytic position was a major determinant of active site closure in the very last stages of nucleotide entry. We propose here that Mg(A) is involved in nucleotide entry already from a very early stage. Its dissociation from the active site region after the previous nucleotide incorporation, either at the pyrophosphate release step as depicted in Fig. 8 (steps 7 to 1), or together with translocation (steps 1 to 2), thus triggers a rearrangement of the NTP tunnel entry that signals availability of the active site for the next +1 base probing. After a new nucleotide orientation at the tunnel entry, Mg(A) passage at the noncatalytic site signals further nucleotide advance to check for pairing to the +1 base. This ensures the simultaneous presence of two magnesium dications with the nucleotide for active site closure, if Watson-Crick base pairing is successful.

The roles of Mg(A) in pre-chemistry steps have been much studied experimentally for base DNA polymerases, notably by stopped-flow assays. For instance, in HIV1 reverse transcriptase a combined experiment and simulation study using Be2+ to substitute for Mg(B) highlighted a specific role of Mg(A). After fingers closing upon incoming NTP binding, Mg(A) would bind and stabilize a catalytically competent active site conformation (32). A similar mechanism involving late binding of Mg(A) is found in bacterial base polymerases, for instance, in experimental study of the pre-chemistry conformational transitions of the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. Alternately mutating the two conserved aspartates Asp705 and Asp882 from motifs A and C (corresponding to NS5B Asp220 and Asp318) shows that the latter (that can bind an Mg2+ ion at the active site even in the absence of nucleotide) is required for fingers closing (33). In contrast the former aspartate is necessary for a subsequent conformational change, likely induced by Mg(A) entry. This late involvement of Mg(A) is obviously similar to the active site closure of RdRp seen when comparing the preinsertion to the ternary complexes of enteroviruses RdRp (17–19). Our work indicates that the steps of NTP binding (with Mg(B)) and fingers closure are replaced in RdRp by shuttling through the NTP tunnel, and that this early process is critically dependent of Mg(A) for limited but critical conformational adjustments in the fingertips. In accordance with this extra early role, Mg(A) can be found at the noncatalytic site in structures of nonternary RdRp complexes crystallized at high Mg2+ concentration (20) and residues making up the site (including Asp219) are conserved throughout RdRp supergroups.

The patterns of residue conservation along the NTP tunnel show successive circles receding from the active site. Thus motif F3 (closest to the active site) is also conserved, with Arg158 being found in all (+)-ssRNA virus RdRp and even in reverse transcriptases, where its counterpart (Arg72 in HIV1 RT) binds the incoming NTP upon fingers closing (5, 32, 34). Further away, motif F1 that we show here prominently contributes to the Arg158 dynamics that substitute for fingers closing is not present in reverse transcriptases. However, it is readily detectable in all (+)-ssRNA virus RdRp, with the counterpart of Lys141 strictly conserved and the counterpart of Glu143 strictly conserved in supergroups I and II (it is an aspartate in supergroup III) (10, 12). In contrast, residues involved in nucleotide reorientation at the tunnel entry are not detectably conserved when considering all RdRp of (+)-ssRNA viruses. For instance, the segment between motifs F1 and F3 is of very varying length between virus families (from 5 to >50 residues) and the entry loop at its tip that harbors motif F2 is highly mobile (35), rendering both sequence-only and structure-based alignments dubious. However, in this third circle residues are conserved within virus families, whether they participate in triphosphate or base stabilization in our simulations. Thus at the tunnel entry motif F2 (including Lys151), Arg48 and Lys51 are strictly conserved in all genotypes of HCV and in its closest relatives. Motif D on the other side of the tunnel from motif F2 also displays this pattern of conservation within families, for instance, in flaviviruses and enteroviruses (35). In enterovirus RdRp a lysine from motif D (not present in HCV NS5B) could serve in reorientation of the nucleotide. This lysine has been proposed also to be directly involved in catalysis and fidelity control (36), but this is by no means exclusive. We propose that nucleotide reorientation at the NTP tunnel entry is a general feature of RdRp but that it may be achieved by different means in different families. Indeed, mechanistically it only requires that the triphosphate moiety be bound by suitably oriented basic residues allowing rotational mobility, and that favorable interactions, not specific of the base, be made available for the base. In support of this, we find here that this is what happens for both UTP and GTP at the tunnel entry of HCV NS5B. The GTP base and triphosphate are bound and oriented at the same spot as UTP, but in distinct orientations and by making distinct contacts to the same NS5B residues.

As stated, and in contrast to nucleotide reorientation, in the next stages of UTP entry we find only residues conserved among (+)-ssRNA RdRp of all three supergroups (10). The central residue regulating template base probing by the incoming nucleotide base is the strictly conserved arginine of motif F3 (Arg158 for HCV NS5B, a supergroup II RdRp). Arg158 achieves its limited but essential movements through an Mg(A)-dependent mobility that is surprising for such a buried residue, particularly as it involves in part its main chain. Sofosbuvir, the ribose-modified nucleotide analogue that is so successful in the treatment of hepatitis C, selects a rare resistance mutation in a residue that is close to the ribose in ternary complexes, but also another mutation, L159F, that is buried in the protein core away from the nucleotide. This highlights the importance of motif F3 main chain dynamics in nucleotide selection (37). The other factor to Arg158 dynamics is its ability to form alternate networks of salt bridges involving conserved residues of motif F1 (Glu143 and Lys141 in HCV NS5B). The counterpart of K141R was selected as a resistance mutation for the antiviral favipiravir (a purine analogue) in the RdRp of chikungunya virus (supergroup III) (38). The same mutation engineered into enterovirus B3 (supergroup I) led to an RdRp with lower fidelity and increased susceptibility (rather than resistance) to favipiravir (39). Again these findings are not ascribable to direct interaction with the analogue but are consistent with the regulation that we see here of F3 dynamics by F1 being important for base selection in all three supergroups of (+)-ssRNA RdRp.

In conclusion, our work points to the dependence on magnesium of conformational adjustments in viral RdRp that allow these enzymes to shuttle incoming nucleotides to the preinsertion state, thus achieving template probing and eventually initial base-pairing through completely different mechanisms than the other, fingers-closing base polymerases. First, the pre-closed fingers of RdRp imply that incoming NTP must be suitably oriented at the entry of their NTP tunnel, something that is probably achieved in different ways by different RdRp families. Second, the counterpart of fingers closing is achieved by magnesium-dependent mobility of motif F3, regulated by motif F1.

This divergent preinsertion mechanism explains in principle why some nucleotide analogues can be so active against viral RdRp, yet not inhibitory toward the mitochondrial RNA polymerase, a critical requirement for nontoxicity (31, 40). For instance, in this scheme Gong and colleagues (17, 18) proposed that local conformational changes in motif A allowed ribose check prior to preinsertion. Such a mechanism for ribose checking is unrelated to the one proposed for T7 RNA polymerase that would involve rather residues of the closing fingers (41). Our work also provides a framework for further establishing mechanistic differences between viral RdRp and cellular polymerases.

Experimental procedures

Construction of the molecular systems

To generate our systems we used the crystallographic structure 4WTA refined to 2.8 Å resolution with a UDP in the active site base-paired to the template RNA +1 adenosine (14). To stabilize the nucleotide in the active site, Appleby et al. (14) used Mn2+ instead of Mg2+ (the likely physiological catalytic ion). Furthermore, to prevent catalysis and incorporation they used nucleoside diphosphates rather than triphosphates, the single β-phosphate in the former being a much worse leaving group than the β,γ-diphosphate in the latter (see the supplemental information to Ref. 14). We changed the two catalytic ions back to Mg2+ (Mg(A) and Mg(B)) and added a γ-phosphate to obtain the ternary NS5B/template-primer RNA/UTP complex (Fig. 1). In principle there is an ambiguity as to which of the two nonchelating oxygens is the bridging oxygen between β- and γ-phosphates, but comparison with a norovirus polymerase ternary complex (PDB 3BS0) (16) makes this unambiguous. The NS5B construct crystallized in 4WTA harbored two deletions, one C-terminal (residues 571–591) to increase solubility and one internal (residues 444–453) to favor the more open RNA-binding conformation. All residues were crystallographically ordered except for a few side chains (that were modeled in stereochemically consistent starting positions) and residues beyond 542 (that were not modeled). Thus our systems comprise 534 protein residues (NS5B 1–443 and 454–542, with an added diglycine to connect 443 to 454) and 12 RNA bases (a 7-base template and a 5-base primer). We included or excluded UTP bound to Mg(B) and/or Mg(A) as indicated. For simulations of GTP entry, we either used the same NS5B/RNA system as for UTP or we mutated the +1 base to C, as indicated. Parameters for UTP were adapted and parameters for GTP were obtained from the nucleotide parameters (http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/bryce/amber).4

Unbiased molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations of the ternary complexes (with UTP) and the binary complexes (without UTP) were carried out with the Gromacs program (42) using the AMBER ff99SB-ILDN force-field. The systems to simulate were neutralized with Cl− counterions and solvated in a periodic cubic box of explicit TIP3P water molecules with a minimum distance of 12 Å between the protein atoms and the edge of the water box. The obtained models were then energy minimized with the steepest descent method for 20,000 steps, whereas restraining the protein and RNA atoms and ions with harmonic potentials with a constant force of 1000 KJ/mol. Our simulation protocol starts by NVT progressive heating in two steps of 500 ps each followed by NPT equilibration. During the NPT equilibration the constraints were gently removed in 12 successive stages, each progressively releasing the restraints on protein side chains, main chain, then RNA. The total length of the equilibration phase was 4 ns. For both equilibration and production, a 2-fs integration step was used. For electrostatic and van der Waals interactions, cut-off distances for the short-range van der Waals (rvdw), Coulomb cut-off (r coulomb), and neighbor list (rlist) were fixed at 12 Å. The particle mesh Ewald method was used for the treatment of long-range electrostatic interactions. Water molecules were constrained using the SETTLE algorithm and the parallel linear constraint solver (P-LINCS) algorithm was used for covalent bond constraints of biomolecules. After the equilibration phase, production runs of 100 ns with a time step for integration of 2 fs were carried out where each simulation started from a different random velocity.

Simulations were also performed with the AMBER 14 suite of programs (43) as indicated, particularly for minimizing and equilibrating systems prior to biased MD (see below). The AMBER protocol was equivalent to the Gromacs protocol.

Biased molecular dynamics simulations

All biased molecular dynamic simulations were performed using the AMBER 14 suite (43).

aMD simulations

aMD (28) is a technique for exploring the conformational space of biomolecules that accelerates the state to state evolution of a system relative to normal molecular dynamics therefore making rare events accessible in reasonable simulation times. In aMD, a positive boosting potential, ΔV(r), is applied to the system if the potential energy drops below a certain energy threshold (E). We used the dual boosting potential of the AMBER implementation of aMD (iamd = 3). We estimated the AMBER aMD input parameters for the boost to the total potential and the extra boost to the torsion potential (EthreshP, αP, EthreshD, and αD) by using the average energy values computed from a 4 to 12 ns unbiased simulation of our system and we used a boost factor of 0.2. aMD were then launched with the parallelized version of the pmemd module of the AMBER package with a 2-fs time step.

TMD

In TMD simulation, a molecular system is guided from an initial structure using a reference structure by adding an extra term to the energy function according to the following equation,

| (Eq. 1) |

where Natm is the number of atoms in the subset used for RMSD(t) computation; K is the energy constant applied during the simulation; RMSD(t) is the root mean square deviation of a subset of atoms in the current structure compared with the same subset in the reference structure. This subset was the UTP heavy atoms (30 atoms) in all our TMD; and RMSDtarget is the desired final RMSD. We used K > 0 and RMSDtarget = 0 to guide the simulation toward the reference structure's UTP from a different starting point. We used K > 0 and RMSDtarget > 0 to push UTP from the reference structure's position. We used energy constants ranging from K1 = 0.01 Kcal/mol/Å2 to K2 = 0.1 Kcal/mol/Å2 as indicated. The initial and reference systems were built to be chemically identical (same topology file) and minimized and equilibrated according to our unbiased AMBER protocol prior to TMD simulations. The TMD were then launched with the parallelized version of the sander module of the AMBER package. The duration of TMD simulations ranged from 1 to 4 ns length with a 2-fs time step.

SMD

During the SMD runs the incoming UTP was positioned outside the polymerase and a harmonic symmetric restraint was applied to reduce the distance of UTP with the +1 base. The atoms defining this distance, the velocity of the translation, and the force constant of the external harmonic force were varied as indicated.

drMD

drMD simulations are conventional MD simulations with an added harmonic energy term if the distance between the UTP or GTP center of mass and the active site is above a threshold distance that we fixed at 30 Å. For the location of the active site we used either Mg(A) or the center of mass of residue 319, as indicated. For each UTP or GTP starting position, we performed five simulations with force constants ranging from 0 to 0.5 kcal/mol/Å2 as indicated.

Analyses

All simulations were analyzed and rendered using the AMBER (43) cpptraj module, VMD 1.9.3 (44), and PyMOL (45). For clustering analyses of the local and global protein conformations we used our homemade program TTClust (25) (https://github.com/tubiana/TTClust)4 under the Gnu General Public License (GPL).

Author contributions

K. B. O., Y. B., and S. B. data curation; K. B. O., Y. B., and S. B. formal analysis; K. B. O. and Y. B. investigation; K. B. O., Y. B., and S. B. visualization; K. B. O., Y. B., and S. B. writing-review and editing; Y. B. and S. B. conceptualization; Y. B. resources; Y. B. and S. B. supervision; Y. B. and S. B. validation; Y. B. methodology; Y. B. and S. B. project administration; S. B. funding acquisition; S. B. writing-original draft.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Samia Aci-Sèche for advice and suggestions on this work. This work was granted access to the high performance computing resources of TGCC under allocation A0010707583 made by GENCI. We also thank the CEA-CCRT infrastructure for giving us access to the supercomputer COBALT.

This work was supported by Agence Nationale de la Recherche sur le Sida et les hépatites virales (France REcherche Nord and sud SIDA-hiv Hépatites) Grant AAP 2014-2 (to S. B.) and a Université Paris-Saclay Graduate Student Fellowship (to K. B. O.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S8.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- RdRp

- RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- HCV

- hepatitis C virus

- (+)-ssRNA

- single-stranded, positive sense RNA (virus)

- TMD

- targeted molecular dynamics

- RMSF

- root mean square fluctuation

- RMSD

- root mean square deviation

- SMD

- steered molecular dynamics

- aMD

- accelerated molecular dynamics

- drMD

- distance restrained MD

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank.

References

- 1. Steitz T. A. (1998) A mechanism for all polymerases. Nature 391, 231–232 10.1038/34542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Delarue M., Poch O., Tordo N., Moras D., and Argos P. (1990) An attempt to unify the structure of polymerases. Protein Eng. 3, 461–467 10.1093/protein/3.6.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ago H., Adachi T., Yoshida A., Yamamoto M., Habuka N., Yatsunami K., and Miyano M. (1999) Crystal structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of hepatitis C virus. Structure 7, 1417–1426 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)80031-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bressanelli S., Tomei L., Roussel A., Incitti I., Vitale R. L., Mathieu M., De Francesco R., and Rey F. A. (1999) Crystal structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 13034–13039 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lesburg C. A., Cable M. B., Ferrari E., Hong Z., Mannarino A. F., and Weber P. C. (1999) Crystal structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from hepatitis C virus reveals a fully encircled active site. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 937–943 10.1038/13305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pflug A., Guilligay D., Reich S., and Cusack S. (2014) Structure of influenza A polymerase bound to the viral RNA promoter. Nature 516, 355–360 10.1038/nature14008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Butcher S. J., Grimes J. M., Makeyev E. V., Bamford D. H., and Stuart D. I. (2001) A mechanism for initiating RNA-dependent RNA polymerization. Nature 410, 235–240 10.1038/35065653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tao Y., Farsetta D. L., Nibert M. L., and Harrison S. C. (2002) RNA synthesis in a cage: structural studies of reovirus polymerase λ3. Cell 111, 733–745 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01110-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Poch O., Sauvaget I., Delarue M., and Tordo N. (1989) Identification of four conserved motifs among the RNA-dependent polymerase encoding elements. EMBO J. 8, 3867–3874 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08565.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koonin E. V. (1991) The phylogeny of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases of positive-strand RNA viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 72, 2197–2206 10.1099/0022-1317-72-9-2197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bruenn J. A. (2003) A structural and primary sequence comparison of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 1821–1829 10.1093/nar/gkg277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koonin E. V., and Dolja V. V. (1993) Evolution and taxonomy of positive-strand RNA viruses: implications of comparative analysis of amino acid sequences. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 28, 375–430 10.3109/10409239309078440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mosley R. T., Edwards T. E., Murakami E., Lam A. M., Grice R. L., Du J., Sofia M. J., Furman P. A., and Otto M. J. (2012) Structure of hepatitis C virus polymerase in complex with primer-template RNA. J. Virol. 86, 6503–6511 10.1128/JVI.00386-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Appleby T. C., Perry J. K., Murakami E., Barauskas O., Feng J., Cho A., Fox D. 3rd, Wetmore D. R., McGrath M. E., Ray A. S., Sofia M. J., Swaminathan S., and Edwards T. E. (2015) Structural basis for RNA replication by the hepatitis C virus polymerase. Science 347, 771–775 10.1126/science.1259210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferrer-Orta C., Arias A., Pérez-Luque R., Escarmís C., Domingo E., and Verdaguer N. (2007) Sequential structures provide insights into the fidelity of RNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9463–9468 10.1073/pnas.0700518104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zamyatkin D. F., Parra F., Alonso J. M., Harki D. A., Peterson B. R., Grochulski P., and Ng K. K. (2008) Structural insights into mechanisms of catalysis and inhibition in Norwalk virus polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7705–7712 10.1074/jbc.M709563200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gong P., and Peersen O. B. (2010) Structural basis for active site closure by the poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 22505–22510 10.1073/pnas.1007626107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shu B., and Gong P. (2016) Structural basis of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase catalysis and translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E4005–E4014 10.1073/pnas.1602591113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu J., and Gong P. (2018) Visualizing the nucleotide addition cycle of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Viruses 10, 24 10.3390/v10010024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malet H., Egloff M.-P., Selisko B., Butcher R. E., Wright P. J., Roberts M., Gruez A., Sulzenbacher G., Vonrhein C., Bricogne G., Mackenzie J. M., Khromykh A. A., Davidson A. D., and Canard B. (2007) Crystal structure of the RNA polymerase domain of the West Nile virus non-structural protein 5. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 10678–10689 10.1074/jbc.M607273200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Temiakov D., Patlan V., Anikin M., McAllister W. T., Yokoyama S., and Vassylyev D. G. (2004) Structural basis for substrate selection by t7 RNA polymerase. Cell 116, 381–391 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00059-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gupta R. K., Gupta P., Yushok W. D., and Rose Z. B. (1983) Measurement of the dissociation constant of MgATP at physiological nucleotide levels by a combination of 31P NMR and optical absorbance spectroscopy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 117, 210–216 10.1016/0006-291X(83)91562-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Romani A. M. (2011) Cellular magnesium homeostasis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 512, 1–23 10.1016/j.abb.2011.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Davis B. C., and Thorpe I. F. (2013) Molecular simulations illuminate the role of regulatory components of the RNA polymerase from the hepatitis C virus in influencing protein structure and dynamics. Biochemistry 52, 4541–4552 10.1021/bi400251g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tubiana T., Carvaillo J.-C., Boulard Y., and Bressanelli S. (2018) TTClust: a versatile molecular simulation trajectory clustering program with graphical summaries. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 58, 2178–2182 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ovchinnikov V., and Karplus M. (2012) Analysis and elimination of a bias in targeted molecular dynamics simulations of conformational transitions: application to calmodulin. J. Phys. Chem. B. 116, 8584–8603 10.1021/jp212634z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bressanelli S., Tomei L., Rey F. A., and De Francesco R. (2002) Structural analysis of the hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase in complex with ribonucleotides. J. Virol. 76, 3482–3492 10.1128/JVI.76.7.3482-3492.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pierce L. C., Salomon-Ferrer R., Augusto F de Oliveira C, McCammon J. A., and Walker R. C. (2012) Routine access to millisecond time scale events with accelerated molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 2997–3002 10.1021/ct300284c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Da L.-T., E C., Duan B., Zhang C., Zhou X., and Yu J. (2015) A jump-from-cavity pyrophosphate ion release assisted by a key lysine residue in T7 RNA polymerase transcription elongation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004624 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shu B., and Gong P. (2017) The uncoupling of catalysis and translocation in the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. RNA Biol. 14, 1314–1319 10.1080/15476286.2017.1300221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Freedman H., Winter P., Tuszynski J., Tyrrell D. L., and Houghton M. (2018) A computational approach for predicting off-target toxicity of antiviral ribonucleoside analogues to mitochondrial RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 9696–9705 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mendieta J., Cases-González C. E., Matamoros T., Ramírez G., and Menéndez-Arias L. (2008) A Mg2+-induced conformational switch rendering a competent DNA polymerase catalytic complex. Proteins 71, 565–574 10.1002/prot.21711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bermek O., Grindley N. D. F., and Joyce C. M. (2011) Distinct roles of the active-site Mg2+ ligands, Asp-882 and Asp-705, of DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) during the prechemistry conformational transitions. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 3755–3766 10.1074/jbc.M110.167593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang H., Chopra R., Verdine G. L., and Harrison S. C. (1998) Structure of a covalently trapped catalytic complex of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: implications for drug resistance. Science 282, 1669–1675 10.1126/science.282.5394.1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Selisko B., Papageorgiou N., Ferron F., and Canard B. (2018) Structural and functional basis of the fidelity of nucleotide selection by flavivirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Viruses 10, 59 10.3390/v10020059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang X., Smidansky E. D., Maksimchuk K. R., Lum D., Welch J. L., Arnold J. J., Cameron C. E., and Boehr D. D. (2012) Motif D of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases determines efficiency and fidelity of nucleotide addition. Structure 20, 1519–1527 10.1016/j.str.2012.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lontok E., Harrington P., Howe A., Kieffer T., Lennerstrand J., Lenz O., McPhee F., Mo H., Parkin N., Pilot-Matias T., and Miller V. (2015) Hepatitis C virus drug resistance-associated substitutions: state of the art summary. Hepatology 62, 1623–1632 10.1002/hep.27934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Delang L., Segura Guerrero N., Tas A., Quérat G., Pastorino B., Froeyen M., Dallmeier K., Jochmans D., Herdewijn P., Bello F., Snijder E. J., de Lamballerie X., Martina B., Neyts J., van Hemert M. J., and Leyssen P. (2014) Mutations in the chikungunya virus non-structural proteins cause resistance to favipiravir (T-705), a broad-spectrum antiviral. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, 2770–2784 10.1093/jac/dku209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abdelnabi R., Morais A. T. S. de, Leyssen P., Imbert I., Beaucourt S., Blanc H., Froeyen M., Vignuzzi M., Canard B., Neyts J., and Delang L. (2017) Understanding the mechanism of the broad-spectrum antiviral activity of favipiravir (T-705): key role of the F1 motif of the viral polymerase. J. Virol. 81, e00487 10.1128/JVI.00487-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jin Z., Kinkade A., Behera I., Chaudhuri S., Tucker K., Dyatkina N., Rajwanshi V. K., Wang G., Jekle A., Smith D. B., Beigelman L., Symons J. A., and Deval J. (2017) Structure-activity relationship analysis of mitochondrial toxicity caused by antiviral ribonucleoside analogs. Antiviral Res. 143, 151–161 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Duan B., Wu S., Da L.-T., and Yu J. (2014) A critical residue selectively recruits nucleotides for t7 RNA polymerase transcription fidelity control. Biophys. J. 107, 2130–2140 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.09.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Berendsen H., Vanderspoel D., and Vandrunen R. (1995) Gromacs: a message-passing parallel molecular-dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 91, 43–56 10.1016/0010-4655(95)00042-E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Case D. A., Cheatham T. E. 3rd, Darden T., Gohlke H., Luo R., Merz K. M. Jr., Onufriev A., Simmerling C., Wang B., and Woods R. J. (2005) The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1668–1688 10.1002/jcc.20290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Humphrey W., Dalke A., and Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38, 27–28 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schrödinger LLC. (2015) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.8, Schroedinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.