Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) affects more than 257 million people globally, resulting in progressively worsening liver disease, manifesting as fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The exceptionally narrow species tropism of HBV restricts its natural hosts to humans and non-human primates, including chimpanzees, gorillas, gibbons, and orangutans. The unavailability of completely immunocompetent small-animal models has contributed to the lack of curative therapeutic interventions. Even though surrogates allow the study of closely related viruses, their host genetic backgrounds, immune responses, and molecular virology differ from those of HBV. Various different models, based on either pure murine or xenotransplantation systems, have been introduced over the past years, often making the choice of the optimal model for any given question challenging. Here, we offer a concise review of in vivo model systems employed to study HBV infection and steps in the HBV life cycle or pathogenesis.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, in vivo, animal model

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a global health concern, resulting in approximately 1 million human deaths annually.1 Despite the availability of a protective vaccine, the often-lacking birth-dose immunization in many countries results in 10–30 million new infections each year.2 HBV belongs to the Baltimore scheme VII classification, being a partially double-stranded DNA virus that transitions through an RNA intermediate through its reverse transcriptase.3 Treatment for HBV infection consists of pegylated interferon (IFN) alpha and reverse transcriptase inhibitors, or combinations thereof, which do not constitute a cure, resulting in universal viral rebound if treatment is interrupted.4 Currently, many novel therapies, including direct-acting antiviral compounds and host factor targeting, are being developed.5 However, the exceptionally narrow species tropism of HBV coupled with the recent ban on the use of chimpanzees in biomedical research makes the evaluation of new therapies in regard to curative potential difficult. Thus far, the molecular determinants for the restriction of HBV in non-human model systems remain largely elusive.

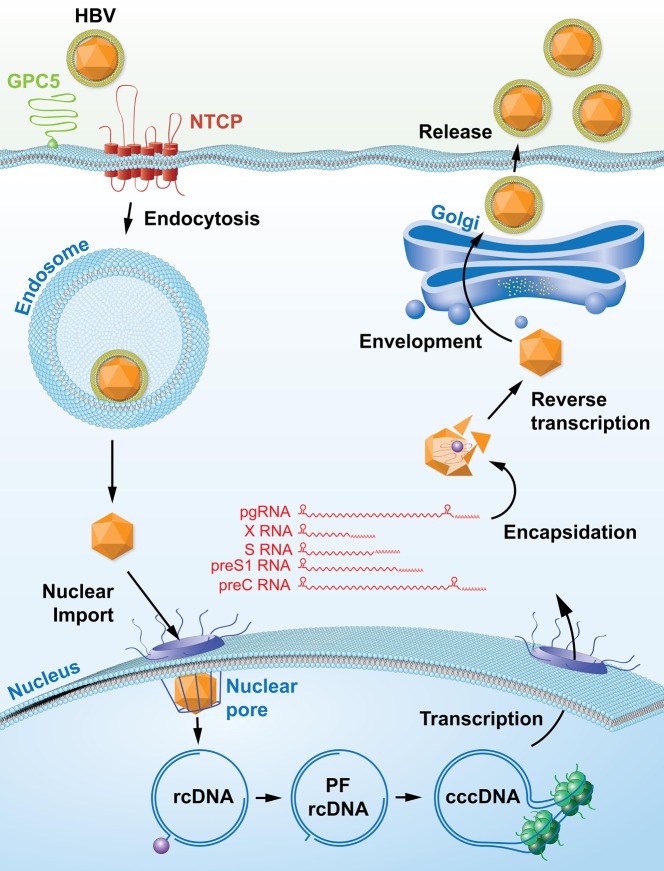

HBV initially binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs)6 and enters hepatocytes in the liver through interaction of its glycoprotein preS1 with the sodium/bile acid co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP).7 Once HBV is internalized via either clathrin-8 or caveolin-mediated mechanisms,9 HBV particle-containing endosomes are transported from early to mature endosomes,10 and enveloped Dane particles fuse with the endosomal membrane by thus far unknown mechanisms. Following release of HBV capsids into the cytoplasm, they are transported along microtubules to the nuclear pore.11 In contrast to other viruses, HBV nucleocapsids are imported intact into the nucleus, potentially via a core protein-encoded nuclear localization signal and importin beta binding motif.12−14 Upon entry of these nucleocapsids into the nuclear pore, nucleoporin (Nup) 153 arrests HBV and allows only mature capsids to enter.15 Once inside the nucleus, the capsid disintegrates and releases the relaxed circular HBV genome, which subsequently undergoes a set of highly orchestrated modifications to remove the covalently linked reverse transcriptase, ligate the complete negative DNA strand, complete the incomplete positive strand, and remove a capped RNA intermediate to form the covalently closed circular (ccc) DNA genome, which serves as a transcriptional template for all HBV transcripts.16 The cccDNA genome is highly associated with host chromatin structures, forming the cccDNA “minichromosome”.17 This includes binding of not only host histones, signaling mediators (e.g., STAT1/2/318,19), transcription factors (e.g., HNF1a/HNF4a19), histone-modifying enzymes (e.g., histone acetyltransferases, histone deacetylases, histone methyltransferases),20−22 and nuclear receptors (FXR, GR)23 but also viral proteins, including hepatitis B X protein (HBx)24 and hepatitis B core (HBc),25 all of which regulate the transcriptional activity of cccDNA.

Host cell polymerase II subsequently transcribes four subgenomic mRNA species, encoding the three glycoproteins, preS1, preS2, and S, as well as the HBx. Additionally, two overlength mRNA species, pre-core and pre-genomic RNA, are produced. These serve as translational templates for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) in the case of pre-core RNA as well as the core protein and the reverse transcriptase, which are produced from pre-genomic RNA by thus far poorly understood mechanisms.26 The HBV reverse transcriptase directly binds to the HBV encapsidation signal structure of the pre-genomic RNA and initiates packaging in association with the HBc.27,28 Once immature HBV capsids are formed, the reverse transcriptase reverse transcribes pre-genomic RNA to form de novo relaxed-circular, partially double-stranded DNA (rcDNA).29 The capsids travel along the secretory pathway and are enveloped prior to release (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Life cycle of hepatitis B virus.

Many of these viral life cycle stages are not recapitulated in non-human cells, ranging from the highly specific interaction of HBV with human NTCP to the nuclear import of capsids and the formation of cccDNA. This has resulted in the creation of several model systems recapitulating individual parts of the HBV life cycle in vivo.

Chimpanzee Model of HBV

Chimpanzees are the only primate model for HBV infection. The identification of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in chimpanzee serum led to the conclusion that chimpanzees are susceptible to infection with HBV.30,31 Following these early studies, chimpanzees became a crucial model for HBV infection. As little as one genome equivalent of virus from a previously infected animal can cause infection in a naïve chimpanzee, in contrast to the thousands of genome equivalents needed for in vitro infection models.32 Other sources of viruses that have been used to infect chimpanzees include sera from chronic HBV patients, recombinant HBV DNA, and cell-line-derived HBV. Reports demonstrating that chimpanzees exposed to HBsAg could generate long-term protective immune responses enabled the development of HBV vaccines.33 The first to be developed, using HBsAg from the serum of chronic HBV carriers,34 was replaced by one constituting HBsAg purified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae.35 Both relied heavily on safety testing performed in chimpanzees.

The realization that MHC and HLA have similar peptide binding characteristics in humans and chimpanzees subsequently enabled the use of the chimpanzee to study the host response to infection. One of the main advantages of using chimpanzees is that liver biopsies can be taken throughout experimental studies. Liver biopsies have enabled interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) expression analysis within the liver, showing the absence of ISG induction early in infection and the importance of a strong CD8+ T cell response for viral clearance at later stages of infection.36,37 Depletion of CD8+ T cells had little effect on early infection but severely impacted the duration of infection, and priming of the CD4+ response at early infection is crucial for a functional CD8+ response.32 Chimpanzees are capable of establishing chronic infections at frequencies similar to those of chronic infections seen in humans. Studying cccDNA persistence, a vital component for chronic infection, has therefore been possible in chronically infected chimpanzees.38 This has enabled the study of many parameters over the course of chronic infections, including viral DNA integration and the clonal expansion of infected hepatocytes.39

The chimpanzee was used in multiple drug studies informing the design of future clinical trials. Initial studies of GS-9620, a TLR7 agonist, in chronically infected chimpanzees showed a reduction in viremia.40 This drug candidate was taken forward to clinical trials, where no reduction in serum HBsAg levels was observed, though there was an increase in T cell responses.41 An approach using small interfering (si) RNA against conserved HBV regions designed to specifically target hepatocytes gave promising results in vitro and was evaluated in chronically infected chimpanzees and HBV-infected patients.42 In this phase II study, the reduction in viremia was dependent on the HBeAg status of the patients. By using this siRNA treatment (ARC-520) in chronically infected chimpanzees, it was shown that HBsAg can be produced in large amounts from integrated HBV DNA. Once HBV DNA integrates, it may lose the siRNA target sites, resulting in a loss of efficiency. This observation could not have been made with data from patient trials alone. However, there are differences in disease progression between chimpanzees and humans, since chimpanzees rarely develop HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Due to ethical constraints, in vivo research has moved away from using chimpanzees. There have been attempts at establishing other non-human primate models, following the detection of HBV in other primate species, including gorillas, orangutans, and macaques. Infectious virus has been isolated from woolly monkeys43 and capuchin monkeys44 and has been shown to be capable of infecting human hepatocytes.43 After intrahepatic injections, Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) show markers of viral infection.45 Endogenous HBV was found in cynomolgus macaques in 2013, but these macaques could not be infected with recombinant HBV.46,47 However, Rhesus macaques expressing human (h) NTCP through adeno-associated viral delivery were recently shown to be susceptible to HBV infection.47 This is, to date, the first description of establishment of cccDNA in macaques, but furthermore it evaluates pathogenesis and immune responses in an immunocompetent primate model of HBV infection.

Tree Shrew Model of HBV

The northern tree shrew, Tupaia belangeri, is the only non-primate susceptible to human HBV. Demonstration of susceptibility to infection in primary Tupaia hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo highlighted the possibility using of the tree shrew as an immunocompetent HBV infection model.48 However, experimental limitations such as the lack of tupaia antibodies and other reagents have hindered their use. Nevertheless, Tupaia have made considerable contributions to the HBV field, as it was in this species that NTCP as receptor for HBV infection was first identified.7 With the development of more assays and reagents, more research is being performed using Tupaia. This has resulted in the description of reduced IFNβ responses in HBV-infected Tupaia.49 Similar to chimpanzees, Tupaia are susceptible to chronic infections at rates similar to those observed in humans, but, in contrast to chimpanzees, they develop HBV-associated HCC.50,51 Pathological changes in the liver are also consistent with disease progression in humans.52 The main use of Tupaia in the context of HBV infection focuses on the similarity to humans with chronic HBV and HCC, but with experimental assays continuing to be developed, the Tupaia may become a very useful model for acute HBV infection.

Surrogate Models for Studying HBV

Woodchuck Hepatitis Virus

Woodchuck hepatitis B virus (WHBV) was first identified in the 1970s.53 WHBV has a high homology to HBV and can cause both acute and chronic infections. There is only one major genotype of WHBV, in contrast to the eight of HBV, and there are differences between the post-transcriptional regulatory elements (PREs) involved in nuclear export of unspliced transcripts and regulating expression of transcripts. HBV has a bipartite PRE, compared to the more active tripartite PRE from woodchucks (WPRE), which has an additional element.54 Due to the high activity level, WPRE has been used to promote expression in genetic vectors.55

The most commonly used woodchuck species is the American Marmota monax, though the Chinese Marmota himalayana is also susceptible to infection.56 The rate of the animals’ development of chronic infections is very similar to that in humans, with 60–75% of infections in neonatal animals but only 5–10% of adults progressing to chronic infection.57 Additionally, almost all infections in woodchucks lead to HCC due to viral integration resulting in the activation of myc, with disease progression comparable to that in humans.58 Studying pathogenesis in woodchucks has recently been made possible by the development of a CD107a assay to study antigen-specific T cell responses, which was not possible previously.59 This demonstrated the importance of cytotoxic T cell responses in WHBV infection and has led to the woodchuck model being used for developing therapeutic vaccines. In contrast to the HBsAg prophylactic vaccine, a therapeutic vaccine against HBV has been the focus, initially suppressing viral load and subsequently inducing immune responses against HBV. DNA vaccines are promising candidates here since they induce strong T cell responses. Combining DNA vaccines with vaccine antigens, such as woodchuck (w)HBsAg, after pretreatment with lamivudine resulted in a reduction of the viral load, though the response was not sustained.60 Optimization of the three components could lead to a more efficient vaccination. Alternative strategies to develop a therapeutic vaccination involve the use of a DNA prime injection followed by an adenoviral (AdV) boost. This was shown to induce T cell responses in naïve woodchucks,61 while in chronically infected woodchucks, entecavir with the DNA prime-Adv boost significantly reduced viral markers, and some animals cleared infection.62 An effective therapeutic vaccine would be beneficial for the hundreds of millions of people with chronic infections and would have advantages over life-long antiviral treatments.

Duck Hepatitis Virus

Duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) is the least similar to HBV, with only 40% sequence homology. Since its discovery in 1980,63 it has been a valuable model for testing antiviral compounds both in vivo using ducklings and in vitro with primary duck hepatocytes. A significant difference compared to HBV lies in viral entry, since the preS domain of the large surface protein of DHBV binds specifically to duck carboxypeptidase D64 and shows no affinity for chicken or human versions of the protein.65 Ducks have been used extensively in the study of cccDNA, in part due to the high numbers of cccDNA copies found in infected duck hepatocytes66 and the comparatively high efficiency of cccDNA formation.67 Key experiments identifying the formation and maintenance of cccDNA were performed in ducks, including those performed by Summers et al.68,69 Increasing the age of ducks at the time of DHBV inoculation corresponded with a decrease in the development of chronic infections,70 mirroring the situation in humans, where in adults the rate of chronic infections is 5–10%. However, infected ducks do not develop cirrhosis or HCC. Despite this, they have been a useful model for studying viral replication and the efficacy of antivirals, such as entecavir.71,72 Overall, the difference between human and duck hepatitis means that results from drug studies may vary considerably between species.

Transgenic Models of HBV

Given the many advantages of mice in biomedical research in regard to genetic versatility, ease of manipulation, and the wealth of available data, large efforts have been undertaken to establish transgenic murine model systems to study the molecular virology and pathogenesis of HBV. These can be separated broadly into single HBV protein-transgenic mice and full genome-transgenic mice (Table 1).

Table 1. Transgenic HBV in Vivo Models.

| antigen | promoter | subtype | background strain | pathogenesis | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBsAg | HBV or metallothionein | ayw | C57BL/6 × SJL hybrid | none | (56) |

| albumin | ayw | C58BL/6J | inflammation, aneupleudy, HCC predominantly in male mice | (57) | |

| albumin | ayw | Balb/C | liver injury, fibrosis | (58) | |

| HBcAg | major urinary promoter | ? | C57BL/6 × SJL hybrid | none | (62) |

| HBeAg | metallothionein promoter | ayw | B10.S | none | (65) |

| HBx | HBV | adr | C57BL/6 | benign adenomas, HCC predominantly in male mice | (67) |

| HBV | adr | C57BL6 × DBA | HCC | (69) | |

| HBV | adw2 | ICR × B6C3F1 | none | (71) | |

| HBV | ayw | C57BL/6J × DBA/2 | none | (72) | |

| full genome | – | ayw | C57BL/6J × SJL/J | none | (73) |

| – | adr4 | C57BL/6 | none | (74) | |

| – | ayw | C57BL/6 or B10.D2 | none | (75) | |

| – | adr | C57 | none | (80) | |

Hepatitis B Virus Surface Antigen (HBsAg)-Transgenic Mice

In 1985, the first transgenic mouse expressing the HBV envelope protein was developed.73 Such mice produce large quantities of HBsAg particles, which are indistinguishable from those present in HBV-infected humans. Notably, these mice did not exhibit signs of pathology and failed to produce antibodies specific to HBsAg, even after immunization. This suggests that liver damage caused by HBV infection is not directly related to the expression of the HBV envelope protein. However, the complete tolerance caused by germ-line-encoded HBV envelope proteins may not reflect infection-associated pathology. Subsequently, HBV-envelope-transgenic mice, originally produced by Chisari et al.,74 were crossed to two distinct genetic backgrounds, C57BL/6 and BALB/c, which revealed that the pathology of the HBV envelope protein is dependent on the host genetic background.75 Interestingly, other studies using the same model showed that the overexpression of HBV large envelope protein by oral administration of zinc inhibits HBsAg secretion76 and that exogenous stimuli using lipopolysaccharide or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α down-regulates HBV gene expression.77 Recently, it was demonstrated that the time-dependent reduction of HBsAg secretion in this model is due to hypermethylation of specific CpG sites. The absence of HBsAg expression decreases cell stress and improves liver integrity, which identified the modulation of HBsAg expression as a possible therapeutic approach for HBV-infected patients.78

Hepatitis B Virus Core Antigen (HBcAg)-Transgenic Mice

In 1994, Guidotti et al. developed the first transgenic mouse expressing the HBV core protein.79 This model suggested that nucleocapsid particles do not cross the hepatocyte nuclear membrane. HBcAg becomes detectable slowly and requires weeks to be detectable in mouse hepatocytes. HBcAg localization is exclusively nuclear, being detectable in the cytoplasm only during mitosis, when the nuclear membrane dissipates. Data from a second HBcAg-transgenic mouse model did not demonstrate any evidence of liver injury.80 In this model, extrathymic expression of HBcAg resulted in T cell tolerance at the level of T cell proliferation, despite the fact that HBcAg is localized primarily in hepatocytes and to a lesser extent in the kidney, whereas it is undetectable in the serum or the thymus other lymphoid tissues. In vivo, anti-HBc antibody production following HBcAg immunization is decreased in the transgenic mice compared to non-transgenic littermate controls. However, no spontaneous anti-HBV core antibody is produced in the transgenic mice in the absence of immunization.81

Hepatitis B Virus Pre-core Antigen (HBeAg)-Transgenic Mice

The first HBeAg-transgenic mouse was generated in 1990.82 HBeAg is not essential for viral infection or replication but is believed to be relevant for the establishment of chronic infection and responsible for modulation of immune responses during chronic HBV infection. During vertical transmission, it has been demonstrated that the rates of establishing chronic infection are higher in babies born from HBeAg-positive mothers, compared to HBeAg-negative mothers.80 In contrast, babies infected during birth from HBeAg-negative mothers experience acute or fulminant infection instead of chronic infection.83 Subsequently, the HBeAg-transgenic mouse was developed to investigate the role of immunological tolerance mechanisms in chronic infection. These mice are completely tolerized to HBeAg and HBcAg at the T cell level. They fail to produce antibodies recognizing HBeAg, but the B cells secrete anti-HBc antibodies. These findings mimic the immunological state of newborn babies of carrier mothers. The T cell tolerance is dependent on the presence of HBeAg, since otherwise T cell tolerance can reverse. In conclusion, this explains, at least in part, the reason for the inverse correlation between age and rate of chronic infection.82

Hepatitis B Virus X (HBx)-Transgenic Mice

HBx is a multifunctional protein with oncogenic potential that participates in the transition from chronic hepatitis B to cirrhosis and HCC as well as other processes relevant during infection. The first HBx-transgenic mouse was created in 1991,84 and transgenic animals expressing HBx suffered histopathological modifications in the liver, including areas of altered hepatocytes, development of benign adenomas, and finally the formation of malignant carcinomas. The outcome is different according to sex, with male mice developing terminal disease before female mice do. The level of HBx antigen expression plays an important role in the outcome as well. The tumor formation in transgenic mice with low expression of HBx protein is similar to that in non-transgenic control mice. However, 84% of transgenic mice with high expression of HBx protein develop liver cancer. The hepatocytes in areas of the liver showing altered morphology have increased DNA synthesis and presence of aneuploid peaks prior to tumor development.85 Even though these results have been independently confirmed,86 there is a plethora of contradicting reports,87−89 leaving the role of HBx in carcinogenesis unclear, to date.

Replication-Competent Full-Length HBV-Transgenic Mice

The single HBV-protein-transgenic mice developed over the years have facilitated the study of assembly, secretion, immune responses, and functionality of these proteins in an in vivo system. However, the presence of all viral proteins and replicative capacity are essential for a better understanding of HBV in an in vivo context.

A first attempt at generating an HBV-transgenic mouse was made in 1988, but the mice failed to transmit the transgene through the germ line.90 The first HBV germ-line-transmitted transgenic mouse expressing the full HBV viral genome was subsequently created in 1989.91 This model was designed to express the HBV genome constitutively in all organs to evaluate the immune response to the different viral antigens. In this model, HBsAg and HBeAg were detectable in the serum, and all viral RNA transcripts were detected in the liver and kidneys of these mice. HBV DNA was detectable in the cytoplasm of the cells in the liver and kidneys and also in the serum. HBV DNA is packaged into core particles, forming virions equal to the ones generated in HBV-infected patients.

The second model, developed in 1995, exhibits much higher levels of HBV replication compared to the other two models developed previously.92 HBV replication in this model is similar to that of HBV chronically infected patients. Different viral markers are highly expressed in liver and kidneys, and viral replication does not induce any cytopathic effect in the mouse hepatocytes. Viral RNA increases over several weeks, reaching a stable plateau 4 weeks after birth. Even though HBV RNA is mainly present in the liver and kidneys, it can also be found in other organs, including the stomach, small intestine, pancreas, and heart. At the protein level, HBsAg, preS1 and HBeAg are detectable in urine and serum, whereas HBcAg is detectable only in the liver and kidney. HBcAg is, similar to the observation in HBcAg-transgenic mice, localized in the nuclei and can be detected only in the cytoplasm of centrilobular hepatocytes and areas close to the renal medulla in the kidneys. HBx could not be detected at the protein level in these mice. HBV DNA is readily detectable by Southern blotting in nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts of the liver. However, HBV DNA is only DNase-resistant in the cytoplasm, demonstrating that the reverse transcription is occurring within the nucleocapsid and suggesting that mature nucleocapsid containing the HBV DNA genome cannot pass through the nuclear pore into the nucleus. Since viral RNA is transcribed from the integrated transgene, no cccDNA is detectable. Infectious viral particles are secreted into the circulatory system, as demonstrated by inoculating chimpanzees with the serum of HBV-transgenic mice.36 HBV DNA in these mice is associated with the HBV polymerase, and electron microscopy showed the production of Dane particles equivalent to the ones produced by HBV-infected patients. In regard to pathogenesis, histological analysis did not show any sign of exacerbated pathogenesis, suggesting no direct relation to HBV antigen but a relation to the antiviral immune responses produced by the host. The HBV-transgenic mouse has been used extensively over the years and has greatly contributed to our knowledge of HBV infection. Guidotti et al. demonstrated that viral clearance in HBV infection is not due to the elimination of infected cells by the cytotoxic T cells, as is the case for other viruses.93 Furthermore, type I IFN and ISG, including interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 1, protein kinase (PK) R, and ribonuclease (RNase) L, tightly regulate HBV replication in HBV-transgenic mice.94 This model has also demonstrated that the reduction of HBV gene expression and replication in the liver upon adoptive transfer of cytotoxic T cells is mediated by IFNγ and TNFα, since blocking these cytokines with antibodies prevents viral clearance. Recently, HBV-transgenic mice have been extensively used to assess the molecular determinants for immunosurveillance within the liver by intravascular effector T cells, which greatly contributed to our understanding of intrahepatic immune responses.95 Other studies in HBV-transgenic mice elucidated the role of antigen-nonspecific inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, Kupffer cells, and platelets.96−100

Subsequently, another strain of HBV-transgenic mice based on the adr subtype of HBV was produced, and these mice, similar to the original HBV-transgenic mice, secrete Dane particles and exhibit mildly elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels.101 Surprisingly, another transgenic strain harboring the adw subtype was described, and the authors reported hepatocellular neoplasms with liver nodules and increased incidence of HCC.102 It remains, however, unclear what governs the differences in these strains.

Tian et al. demonstrated that HBeAg is a critical factor for the establishment of chronic infection during vertical transmission103 by using yet another HBV-transgenic mouse strain.104 HBeAg is responsible for the impairment of CD8+ T cell responses in the offspring by upregulation of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and alteration of the polarization of hepatic macrophages.

For a more in-depth study of the immune responses to HBV, Baron et al. generated two alternative versions of HBV-transgenic mice.105 Mice expressing large, medium, and small HBV surface antigens as transgenes in the liver106 were backcrossed to immunodeficient (recombination activating gene (Rag)-1–/–)107 or T cell receptor C-α chain-deficient (TCR C-α–/–) mice.108 The adoptive transfer of naïve splenocytes into these mice allowed the evaluation of immune responses and pathologic evolution. Nonclassical natural killer T cells (NKT cells) get activated by hepatocytes expressing hepatitis B viral antigens.105 Furthermore, NKG2D and its ligand, retinoic acid early inducible-1 (RAE-1), are modulated in the livers of these transgenic mice on NKT cells by HBV. Inhibition of the NKG2D–ligand interaction completely prevented nonclassical NKT cell-mediated acute hepatitis and liver injury.109 Additionally, this has led to a better understanding of the successful immune control of HBV by adult individuals. Interleukin (IL) 21 and OX40 (CD134) play important roles in HBV persistence in young individuals versus adults due to age-dependent changes in their expression.110,111 Also, the function of liver macrophages on lymphoid organization and immune priming within the adult liver has an impact on promoting successful immunity to control HBV infection.110

HBV-transgenic mice have been very useful for the evaluation of antiviral drugs and treatments, including IFN, poly(IC), IL15, nucleoside analogues, lamivudine, adefovir, and entecavir, and for the understanding of their mechanisms of action in some cases.93,112−118 Additionally, it was demonstrated that siRNA targeting the HBV RNA transcripts can effectively suppress viral replication119−121 and that 5′-triphosphorylated HBV-specific siRNAs activating the retinoid acid-inducible protein I-dependent pathway can induce the production of type I IFN and inhibit viral replication directly.122

In summary, HBV-transgenic mice recapitulate replication and secretion of HBV infectious viral particles, making them powerful tools for the study of some steps of the HBV viral cycle, viral pathogenesis, and development of liver cancer. However, they do not recapitulate viral entry, nuclear import, and cccDNA formation, which are crucial to developing new therapies and investigating HBV infection in a more physiological context. Due to their immunotolerant nature, HBV-transgenic mice do not develop hepatitis, and the study of immune cells requires adoption of naïve cells. Viral clearance cannot be studied in this model due to the fact that the HBV genome is integrated in the host genome, and cccDNA is not produced. To study viral clearance, entry, cccDNA formation, and interaction with adaptive immune responses without immunotolerance, other mouse models have been developed and can be used. They will be described in the following parts of this Review.

Immunocompetent Mouse Models of HBV

In order to circumvent the problems with immune tolerance associated with germ line integration of HBV transgenes, several alternative models were created, aiming at the transient delivery of replication-competent HBV. In the absence of a functional small-animal model recapitulating the early steps of HBV entry, nuclear capsid import, and cccDNA formation, alternative methods are required to deliver replication-competent HBV DNA to the liver of these animals.

Hydrodynamic Delivery-Based Model Systems

The first transient replication-competent mouse model for HBV is based on hydrodynamic delivery (HDD) of overlength HBV DNA-containing plasmids.123 HDD is a nonviral method for intracellular gene delivery to the liver and involves the rapid injection of a large liquid bolus containing the plasmid.124 Although generally well tolerated, this delivery method results in sinusoidal expansion, disruption of fenestrae, and elevations in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and ALT levels.125 HDD of HBV-containing plasmids results in rapid increases in circulating viral antigen and Dane particles, comparable to those observed in the HBV-transgenic mouse. In comparison to transgenic models, HDD is more versatile and has been used to study replication of distinct HBV genotypes and to evaluate drug resistance using reverse genetics.126 However, in immunocompetent mice, HBV infection is rapidly sensed by the mouse’s immune system and is usually cleared within 1–2 weeks.123 This model was used to evaluate HBV persistence using a variety of immunodeficient mouse strains, demonstrating that CD4 and CD8 T cells, but not B cells, are responsible for HBV clearance.127 Additionally, the same study revealed a contribution of NK cells and type I IFN in the clearance mechanism of HBV. While this model enables the study of immune clearance, it is limited for studying curative therapies. Similar to HBV-transgenic mice, all HBV transcripts exclusively originate from the plasmid encoding the overlength HBV genome, resulting in the general absence of cccDNA. To bypass this step, a plasmid-free system was recently developed, in which a recombinant HBV genome resembling cccDNA is used for HDD.128 This approach was shown to result in persistence of HBV in C3H/HeN mice, with at least part of the delivered recombinant cccDNA being associated with host chromatin.

Adenovirus and Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV)-Based Model Systems

Since the transient nature of the HBV HDD model does not allow for the analysis of pathogenesis or immune responses during chronicity, viral gene delivery vectors, including adenoviral129−131 and adeno-associated viral vectors,132−134 were subsequently adapted for the delivery of overlength HBV genomes into the livers of mice. HBV infection in these models is rapidly established, and reports have shown that both adenovirus and AAV delivery of HBV genomes results in the formation of cccDNA.131,135 Of note, however, transcriptional activity of pre-genomic RNA in these models is driven by a cytomegalovirus promoter, rather than by the HBV-intrinsic promoters, resulting in potentially differential RNA expression and ratios of viral proteins.

Interestingly, especially in the adenovirus-based HBV system, the dose of adenoviruses used for infection directly correlates with the outcome of infection. While high doses of adenovirus result in immune-mediated clearance of HBV infection, low doses of adenovirus were shown to lead to persistent infection in immunocompetent mice.129 It is, however, likely that adenoviral antigens, which are very immunogenic, contribute to this effect. In contrast to this, adeno-associated viral vectors usually do not induce immune activation and have been shown to even induce immune tolerance when delivered to the liver.136 Even though this is beneficial when establishing HBV persistence in mice, the resulting model exhibits HBV-tolerized T cells.133 Nevertheless, these models have been used to evaluate the impact of TLR agonists134 as well as adenovirus-based vaccine candidates137 on HBV infection.

Human NTCP-Transgenic Mice

The discovery of NTCP as the key entry receptor for HBV,138 as well as the molecular characterization of species-restricting binding residues of NTCP,139 raised hopes that expression of human NTCP in mice would render them susceptible to HBV infection. Even though the transgenic expression of human NTCP in mice enables infection and persistence of hepatitis D virus (HDV),140−142 which, as a viral satellite, utilizes the HBV glycoproteins for entry, no evidence for successful infection with HBV is available, to date. Several studies have since then delineated that the absence of an essential host factor, rather than the presence of a restriction factor, prevents HBV infection in human NTCP-expressing mice.143−145 It remains, however, unclear as to whether this block in infection is at the level of capsid transport post endocytosis, nuclear capsid import, or the formation of cccDNA.

Xenotranplantation Models for HBV

Human Liver-Chimeric Mice

In contrast to the transgenic expression or gene delivery of HBV genes or genomes in mouse hepatocytes in vivo, human liver-chimeric mice are circumventing the refractory nature of mice to HBV infection by the engraftment of primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) in highly immunodeficient mice. This most commonly entails genetic deficiency in either Rag1107 or Rag2,146 or in the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase (Prkdc),147 to abolish mature B and T cells as well as deficiency of the IL2 receptor common gamma chain,148 which results in reduced lymphocyte numbers and NK cell deficiency.

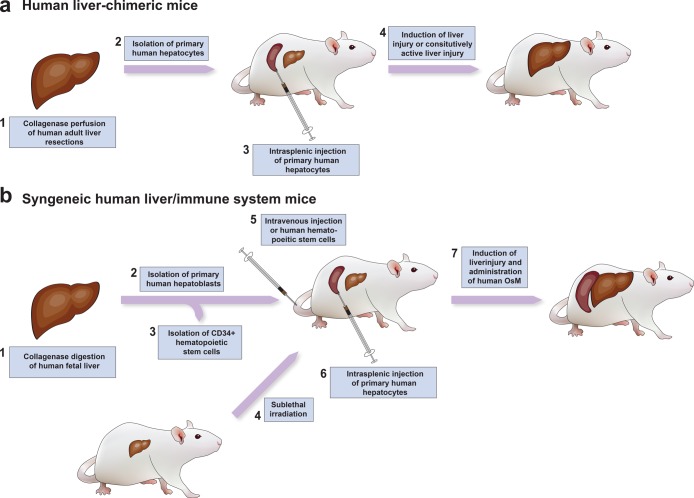

All human liver-chimeric mouse models are based on the same principle of causing murine hepatocellular damage, thereby creating an advantageous environment for human hepatocyte transplantation149−156 (Table 2). The means of generating the underlying liver injury differs between models, but three main background strains of mice are most commonly used.

Table 2. Model Systems of Different Human Liver-Chimeric Mice.

| model | background | mode of liver injury | inducible liver injury | maximal engraftment (%) | immune reconstitution | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| uPA/Rag2 | B6(Cg)-Rag2tm1.1Cgn | albumin promoter-driven urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) expression | no | 15 | no | (101) |

| uPA/Scid-beige | CB17.Cg-PrkdcscidLystbg-J | no | >50 | no | (110) | |

| BRGS-uPA | C.Cg-Rag2tm1.1FwaIL2rgtm1Sug | no | 50 | yes | (122) | |

| FRG | C;129S4-Rag2tm1.1FlvIL2rgtm1.1Flv | FAH deficiency resulting in accumulation of toxic metabolites | yes | 97 | no | (103) |

| FRGN | NOD.Cg-Rag2tm1.FwaIL2rgtm1.Sug | yes | >80 | yes | (123) | |

| FNRG | NOD.Cg-Rag1tm1.MomIL2rgtm1.Wjl | yes | >80 | yes | (124) | |

| ACF8 | C.Cg-Rag2tm1.FwaIL2rgtm1.Sug | dimerization of caspase 8 resulting in hepatocyte death | yes | 15 | yes | (108) |

| TK-NOG | NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIL2rgtm1.Sug | albumin promoter-driven HSV1 thymidine kinase expression | yes | 94 | no (but possible) | (106) |

The urokinase-type plasminogen activator/severe combined immunodeficiency (uPA/Scid) model was the first described human liver-chimeric mouse, in which uPA expression in the liver is driven via a hepatocyte-specific albumin promoter. Its constitutive activity results in hypo-fibrinogenemia and severe hepatotoxicity.157 Dandri et al. were the first to realize that this environment presented an opportunity to transplant human hepatocytes.149 The initial model, based on Rag2–/– mice, had an engraftment rate of 15% and successfully infected HBV in heterozygous uPA-Rag2–/– mice. Mercer et al. subsequently crossed homozygous uPA mice with SCID/Beige mice and demonstrated a considerably higher human hepatocyte engraftment level.158 Homozygous uPA/SCID mice demonstrate higher human hepatocyte engraftment levels and prolonged viremia compared to heterozygous mice; this is most likely due to somatic deletion of the transgene in heterozygotes, leading to normal hepatocyte regeneration.157 Unfortunately, homozygous mice have a very narrow time window in which human hepatocyte engraftment must take place and a generally very high mortality rate.159 Homozygous uPA mice are infertile, and normal hepatocytes from uPA–/– mice are required to rescue their reproductive capability.159 Furthermore, the actual procedure of transplanting PHH into extremely small and young mice, which are prone to severe bleeding, is technically challenging.

In order to circumvent these challenges, Grompe et al. subsequently developed a background strain with inducible liver injury based on the deficiency of fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase (Fah).160 Fah deficiency disrupts the conversion of fumaryl acetoacetate to fumarate and acetoacetate in tyrosine catabolism, resulting in the accumulation of succinyl acetone, which causes severe liver and kidney damage. Liver injury in this model, however, can be prevented by providing the mice with 2-(2-nitro-4-trifluoromethylethylbenzoyl)-cyclohexane-1,3-dione (NTBC) in their drinking water. Initially, for the creation of human xenografts, the Fah-deficient mice were bred to Rag2–/–IL2rg–/– mice (FRG), and these became fully established as a viable model when Bissig et al. demonstrated 97% human liver chimerism and successfully infected mice with HBV.151 In contrast to the uPA/Scid model, FRG mice require continuous weight-based cycling of NTBC in order to sustain human hepatocyte engraftment for extended periods of time.

Other models for inducible liver injury have been developed over time, ranging from models with inducible active caspase 8, where a synthetic dimerizer results in caspase 8-dependent hepatocyte apoptosis,156 to models with transgenic expression of the herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1) thymidine kinase (TK), where hepatocyte injury is induced by treatment with ganciclovir.155 Common in all these models, PHHs are injected intra-splenically in order to ensure equal distribution in the liver, where the liver injury triggers the proliferative expansion of the PHH to occupy the murine parenchyma. Over the course of 1–3 months, depending on the quality of the initially injected hepatocytes, the number of transplanted hepatocytes, and the background strain used, over 90% of the liver is replaced with human cells (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Creation of human liver-chimeric and syngeneic human liver chimeric/immune system mice.

In contrast to transgenic HBV models, human liver-chimeric mice are highly susceptible to patient-derived HBV of HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative isolates.149,161 Reports on the exact susceptibility to infection with HBV, however, vary widely. Only a few data are available on utilization of minimum-dose infection studies, which suggests as little as a single HBV virion launching infection.162 Most commonly, however, inocula of 104–108 HBV genome equivalents are used to initiate infection.153,163−168 HBV readily produces cccDNA in the human hepatocytes, rendering them a valuable tool for the development of cccDNA-targeting or curative therapies.149,161

Human Immune System/Liver-Chimeric Mice

One of the shortcomings of human liver-chimeric mice is their complete immunodeficiency, limiting the study of curative therapies, where immune-mediated clearance likely plays an important role. To circumvent this, several groups have adapted and combined humanized mouse approaches (e.g., the engraftment of a human immune system through transplantation of human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs))169 with human liver-chimeric mice. In the classical humanized mouse models, human HSCs are injected into highly immunodeficient mice, similar to the ones used for human liver-chimeric mice. These subsequently home to the bone marrow and repopulate the animal with all major human leukocyte lineages. Initial models of dually humanized mice consisted of allogeneic sources of PHHs and HSCs.170,171 This, however, requires complete HLA-matching of PHHs and HSCs and does not account for mismatches in Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors on NK cells. The main reason for the use of allogeneic cell sources was the reduced ability of human fetal hepatoblasts to successfully engraft in human liver-chimeric mice.156,172 Even though the double humanization of mice and subsequent infection with hepatitis C virus were reported, liver engraftment in this model did not reach the same level as compared to that following transplantation of adult hepatocytes.156 However, the recent identification of human oncostatin M (OsM) as a non-redundant growth factor limiting the terminal differentiation and thus repopulation of immunodeficient mice with fetal hepatoblasts has largely overcome this.172 Providing mice with recombinant OsM during the engraftment period results in mice with syngeneic human liver and immune system (Figure 2b). Most strikingly, Billerbeck et al. report that NK cells, which are usually largely dysfunctional in humanized mice due to an incompatibility of murine IL15, show functionality in human liver/immune system mice.172 However, despite the ability to establish persistent infection in this model, there have been no reports on the induction of immune-mediated liver injury or fibrosis. This may, at least in part, be due to the human immune system in humanized mice not being fully functional, including absent B cell and macrophage responses, unless extensive human growth factors are supplied to the mice.173,174

Conclusions

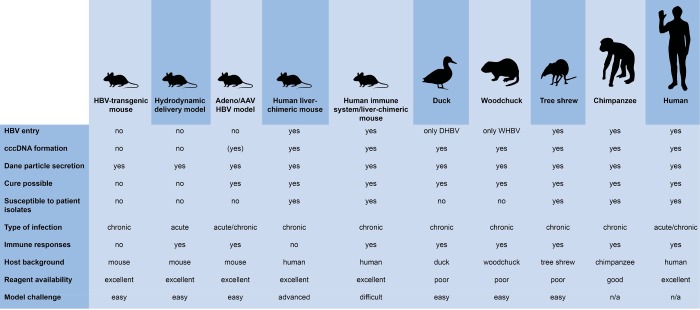

Many different model systems have been described for modeling individual aspects of the HBV life cycle or the complete infection cycle in vivo (Figure 3). This can make the choice of models difficult, since each model has its strengths and weaknesses. Even though single HBV-protein-transgenic mice have contributed to our understanding of the genes’ functions in vivo, their expression is mostly driven by constitutive or tissue-specific, but not viral, promoters. The resulting expression levels are, in many cases, much higher than those observed in HBV-infected humans, and many reports offer contradicting results as to their contribution to HBV pathogenesis. They might, however, be a useful platform to evaluate novel direct-acting antivirals inhibiting HBsAg secretion or encapsidation of viral nucleocapsids.

Figure 3.

Comparison of different HBV in vivo model systems.

In contrast, HBV-transgenic mice expressing the complete HBV genome have greatly contributed to our understanding of the HBV life cycle, its interaction with innate and adaptive immune responses, and HBV-associated pathogenesis. Even in the absence of HBV entry, this model has demonstrated that murine hosts do not contain dominant-negative restriction factors, paving the way to the creation of model systems allowing infection of mice. Despite this, human NTCP-transgenic mice have been shown to still be refractory to HBV infection, suggesting that key steps of the viral life cycle, from receptor engagement to generation of cccDNA, are still not functional in mice. The major limitation of HBV-transgenic mice is the immune tolerance of the mice, combined with the lack of cccDNA and the integrated nature of the HBV transgene. This poses significant problems when utilizing these mice for the study of curative HBV therapies.

Even though hydrodynamic delivery and adenoviral and adeno-associated viral delivery of HBV have been shown to initiate transient or stable HBV infection, these model systems hold the same inherent problems as the HBV-transgenic mouse. HBV transcripts in these models are driven by constitutively active promoters rather than viral promoters, and, even though cccDNA was successfully detected in AAV-HBV-infected mice,135 they still contain the delivered viral genome within the AAV backbone, limiting their use for evaluation of curative therapies. Nevertheless, these models, as well as novel, backbone-free recombinant cccDNA models, are extremely valuable for assessing immune responses to HBV infection and may assist in the development of therapeutic vaccinations or therapies based on the killing of HBV-infected cells. However, given the high infectivity of HBV, it is likely that re-infection of cells and virus spread will play important roles in assessing the efficacy of curative therapies. Models unable to recapitulate this step in the HBV life cycle may result in over-interpretation of any approach aimed at eradicating cccDNA from the liver.

Finally, human liver-chimeric mice have replaced the chimpanzee as the gold-standard model for the evaluation of the complete HBV life cycle in vivo. Although human liver-chimeric mice were originally considered as a difficult to work with and frail model system, novel background strains with inducible liver injury and advanced generation protocols have facilitated the creation of larger cohorts for inclusion in preclinical studies. Among the main caveats, which hold true even more so for dually human liver/immune system mice, are the ethical concerns and limitations of PHH and HSC. Recent advances in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived hepatocyte engraftment of human liver-chimeric mice and their subsequent HBV infection are very promising.175 However, reports on iPSC-derived HSC and their engraftment are, to date, very limited.176 If this were overcome, the resulting model would allow for an indefinite cell source for xenotransplantation.

Ultimately, however, a fully susceptible, immunocompetent mouse model for HBV infection would mitigate many of the individual shortcomings of other models. Since HBV replication and assembly have been shown to be successful in mouse hepatocytes of the HBV-transgenic mouse models and human NTCP-transgenic mice are susceptible to hepatitis D virus infection, which utilizes the same receptor as HBV, it is likely that any block in the HBV life cycle in mice is located at the point of capsid nuclear import or the generation and maintenance of cccDNA. If this could be overcome, the resulting murine HBV model would greatly contribute to assessing novel curative approaches as well as understanding the complex pathogenesis of HBV infection.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding through a Wellcome Trust New Investigator award to M.D. (104771/Z/14/Z), a starting grant from the European Research Council to M.D. (ERC-StG-2015-637304), and the Imperial NIHR Biomedical Research Centre.

Author Contributions

A.M.O.-P. and M.D. conceptualized this Review. A.M.O.-P., C.C., H.G., and M.D. contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- MacLachlan J. H.; Cowie B. C. (2015) Hepatitis B virus epidemiology. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 5 (5), a021410 10.1101/cshperspect.a021410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein L. R.; Mariat S.; Gacic-Dobo M.; Diallo M. S.; Conklin L. M.; Wallace A. S. (2017) Global Routine Vaccination Coverage, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66 (45), 1252–1255. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6645a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore D. (1971) Expression of animal virus genomes. Bacteriol. Rev. 35 (3), 235–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepo C.; Chan H. L.; Lok A. (2014) Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet 384 (9959), 2053–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testoni B.; Durantel D.; Zoulim F. (2017) Novel targets for hepatitis B virus therapy. Liver Int. 37, 33–39. 10.1111/liv.13307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leistner C. M.; Gruen-Bernhard S.; Glebe D. (2007) Role of glycosaminoglycans for binding and infection of hepatitis B virus. Cell. Microbiol. 10 (1), 122–33. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H.; Zhong G.; Xu G.; He W.; Jing Z.; Gao Z.; Huang Y.; Qi Y.; Peng B.; Wang H.; Fu L.; Song M.; Chen P.; Gao W.; Ren B.; Sun Y.; Cai T.; Feng X.; Sui J.; Li W. (2012) Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. eLife 1, e00049 10.7554/eLife.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. C.; Chen C. C.; Chang W. C.; Tao M. H.; Huang C. (2012) Entry of hepatitis B virus into immortalized human primary hepatocytes by clathrin-dependent endocytosis. J. Virol. 86 (17), 9443–53. 10.1128/JVI.00873-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macovei A.; Radulescu C.; Lazar C.; Petrescu S.; Durantel D.; Dwek R. A.; Zitzmann N.; Nichita N. B. (2010) Hepatitis B virus requires intact caveolin-1 function for productive infection in HepaRG cells. J. Virol. 84 (1), 243–53. 10.1128/JVI.01207-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macovei A.; Petrareanu C.; Lazar C.; Florian P.; Branza-Nichita N. (2013) Regulation of hepatitis B virus infection by Rab5, Rab7, and the endolysosomal compartment. J. Virol. 87 (11), 6415–27. 10.1128/JVI.00393-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe B.; Glebe D.; Kann M. (2006) Lipid-mediated introduction of hepatitis B virus capsids into nonsusceptible cells allows highly efficient replication and facilitates the study of early infection events. J. Virol. 80 (11), 5465–73. 10.1128/JVI.02303-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh C. T.; Liaw Y. F.; Ou J. H. (1990) The arginine-rich domain of hepatitis B virus pre-core and core proteins contains a signal for nuclear transport. J. Virol. 64 (12), 6141–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt S. G.; Milich D. R.; McLachlan A. (1991) Hepatitis B virus core antigen has two nuclear localization sequences in the arginine-rich carboxyl terminus. J. Virol. 65 (2), 575–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann M.; Sodeik B.; Vlachou A.; Gerlich W. H.; Helenius A. (1999) Phosphorylation-dependent binding of hepatitis B virus core particles to the nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 145 (1), 45–55. 10.1083/jcb.145.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz A.; Schwarz A.; Foss M.; Zhou L.; Rabe B.; Hoellenriegel J.; Stoeber M.; Pante N.; Kann M. (2010) Nucleoporin 153 arrests the nuclear import of hepatitis B virus capsids in the nuclear basket. PLoS Pathog. 6 (1), e1000741 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniger C.; Wingert I.; Marsmann M.; Rosler C.; Beck J.; Nassal M. (2014) Involvement of the host DNA-repair enzyme TDP2 in formation of the covalently closed circular DNA persistence reservoir of hepatitis B viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111 (40), E4244–53. 10.1073/pnas.1409986111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. T.; Guo H. (2015) Metabolism and function of hepatitis B virus cccDNA: Implications for the development of cccDNA-targeting antiviral therapeutics. Antiviral Res. 122, 91–100. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni L.; Allweiss L.; Guerrieri F.; Pediconi N.; Volz T.; Pollicino T.; Petersen J.; Raimondo G.; Dandri M.; Levrero M. (2012) IFN-alpha inhibits HBV transcription and replication in cell culture and in humanized mice by targeting the epigenetic regulation of the nuclear cccDNA minichromosome. J. Clin. Invest. 122 (2), 529–37. 10.1172/JCI58847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo G. A.; Scisciani C.; Pediconi N.; Lupacchini L.; Alfalate D.; Guerrieri F.; Calvo L.; Salerno D.; Di Cocco S.; Levrero M.; Belloni L. (2015) IL6 Inhibits HBV Transcription by Targeting the Epigenetic Control of the Nuclear cccDNA Minichromosome. PLoS One 10 (11), e0142599 10.1371/journal.pone.0142599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z. Q.; Zhang Y. H.; Ke C. Z.; Chen H. X.; Ren P.; He Y. L.; Hu P.; Ma D. Q.; Luo J.; Meng Z. J. (2017) Curcumin inhibits hepatitis B virus infection by down-regulating cccDNA-bound histone acetylation. World J. Gastroenterol 23 (34), 6252–6260. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i34.6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J. H.; Tao Y.; Zhang Z. Z.; Chen W. X.; Cai X. F.; Chen K.; Ko B. C.; Song C. L.; Ran L. K.; Li W. Y.; Huang A. L.; Chen J. (2014) Sirtuin 1 regulates hepatitis B virus transcription and replication by targeting transcription factor AP-1. J. Virol. 88 (5), 2442–51. 10.1128/JVI.02861-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. W.; Lee S. H.; Park Y. S.; Hwang J. H.; Jeong S. H.; Kim N.; Lee D. H. (2011) Replicative activity of hepatitis B virus is negatively associated with methylation of covalently closed circular DNA in advanced hepatitis B virus infection. Intervirology 54 (6), 316–25. 10.1159/000321450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radreau P.; Porcherot M.; Ramiere C.; Mouzannar K.; Lotteau V.; Andre P. (2016) Reciprocal regulation of farnesoid X receptor alpha activity and hepatitis B virus replication in differentiated HepaRG cells and primary human hepatocytes. FASEB J. 30 (9), 3146–54. 10.1096/fj.201500134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni L.; Pollicino T.; De Nicola F.; Guerrieri F.; Raffa G.; Fanciulli M.; Raimondo G.; Levrero M. (2009) Nuclear HBx binds the HBV minichromosome and modifies the epigenetic regulation of cccDNA function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106 (47), 19975–9. 10.1073/pnas.0908365106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong C. K.; Cheng C. Y. S.; Tsoi S. Y. J.; Huang F. Y.; Liu F.; Seto W. K.; Lai C. L.; Yuen M. F.; Wong D. K. (2017) Role of hepatitis B core protein in HBV transcription and recruitment of histone acetyltransferases to cccDNA minichromosome. Antiviral Res. 144, 1–7. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A.; Kao Y. F.; Brown C. M. (2005) Translation of the first upstream ORF in the hepatitis B virus pregenomic RNA modulates translation at the core and polymerase initiation codons. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 (4), 1169–81. 10.1093/nar/gki251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack J. R.; Ganem D. (1993) An RNA stem-loop structure directs hepatitis B virus genomic RNA encapsidation. Arch. Intern. Med. 67 (6), 3254–63. 10.1001/archinte.1993.00410130081008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N.; White S. J.; Thompson R. F.; Bingham R.; Weiss E. U.; Maskell D. P.; Zlotnick A.; Dykeman E.; Tuma R.; Twarock R.; Ranson N. A.; Stockley P. G. (2017) HBV RNA pre-genome encodes specific motifs that mediate interactions with the viral core protein that promote nucleocapsid assembly. Nat. Microbiol 2, 17098. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassal M. (2008) Hepatitis B viruses: reverse transcription a different way. Virus Res. 134 (1–2), 235–49. 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman R. J.; Shulman N. R.; Barker L. F.; Smith K. O. (1969) Virus-like particles in sera of patients with infectious and serum hepatitis. JAMA 208 (9), 1667–70. 10.1001/jama.1969.03160090027006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard J. E.; Berquist K. R.; Krushak D. H.; Purcell R. H. (1972) Experimental infection of chimpanzees with the virus of hepatitis B. Nature 237 (5357), 514–5. 10.1038/237514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asabe S.; Wieland S. F.; Chattopadhyay P. K.; Roederer M.; Engle R. E.; Purcell R. H.; Chisari F. V. (2009) The size of the viral inoculum contributes to the outcome of hepatitis B virus infection. J. Virol. 83 (19), 9652–62. 10.1128/JVI.00867-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepo C.; Vnek J.; Prince A. M. (1975) Delayed hypersensitivity and Arthus reaction to purified hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in immunized chimpanzees. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 4 (4), 528–37. 10.1016/0090-1229(75)90094-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe V. J.; Purcell R. H.; Gerin J. L. (1980) Type B hepatitis: a review of current prospects for a safe and effective vaccine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2 (3), 470–92. 10.1093/clinids/2.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenne J. (1990) Development and production aspects of a recombinant yeast-derived hepatitis B vaccine. Vaccine 8 (Suppl), S69–73. (discussion on S79–80) 10.1016/0264-410X(90)90221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti L. G.; Rochford R.; Chung J.; Shapiro M.; Purcell R.; Chisari F. V. (1999) Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection. Science 284 (5415), 825–9. 10.1126/science.284.5415.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland S.; Thimme R.; Purcell R. H.; Chisari F. V. (2004) Genomic analysis of the host response to hepatitis B virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 (17), 6669–74. 10.1073/pnas.0401771101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland S. F.; Spangenberg H. C.; Thimme R.; Purcell R. H.; Chisari F. V. (2004) Expansion and contraction of the hepatitis B virus transcriptional template in infected chimpanzees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 (7), 2129–34. 10.1073/pnas.0308478100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W. S.; Low H. C.; Xu C.; Aldrich C. E.; Scougall C. A.; Grosse A.; Clouston A.; Chavez D.; Litwin S.; Peri S.; Jilbert A. R.; Lanford R. E. (2009) Detection of clonally expanded hepatocytes in chimpanzees with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J. Virol. 83 (17), 8396–408. 10.1128/JVI.00700-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanford R. E.; Guerra B.; Chavez D.; Giavedoni L.; Hodara V. L.; Brasky K. M.; Fosdick A.; Frey C. R.; Zheng J.; Wolfgang G.; Halcomb R. L.; Tumas D. B. (2013) GS-9620, an oral agonist of Toll-like receptor-7, induces prolonged suppression of hepatitis B virus in chronically infected chimpanzees. Gastroenterology 144 (7), 1508–17. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boni C.; Vecchi A.; Rossi M.; Laccabue D.; Giuberti T.; Alfieri A.; Lampertico P.; Grossi G.; Facchetti F.; Brunetto M. R.; Coco B.; Cavallone D.; Mangia A.; Santoro R.; Piazzolla V.; Lau A.; Gaggar A.; Subramanian G. M.; Ferrari C. (2018) TLR7 Agonist Increases Responses of Hepatitis B Virus-Specific T Cells and Natural Killer Cells in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B Treated With Nucleos(T)Ide Analogues. Gastroenterology 154 (6), 1764–1777e7. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooddell C. I.; Rozema D. B.; Hossbach M.; John M.; Hamilton H. L.; Chu Q.; Hegge J. O.; Klein J. J.; Wakefield D. H.; Oropeza C. E.; Deckert J.; Roehl I.; Jahn-Hofmann K.; Hadwiger P.; Vornlocher H. P.; McLachlan A.; Lewis D. L. (2013) Hepatocyte-targeted RNAi therapeutics for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Mol. Ther. 21 (5), 973–85. 10.1038/mt.2013.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanford R. E.; Chavez D.; Barrera A.; Brasky K. M. (2003) An infectious clone of woolly monkey hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 77 (14), 7814–9. 10.1128/JVI.77.14.7814-7819.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho Dominguez Souza B. F.; Konig A.; Rasche A.; de Oliveira Carneiro I.; Stephan N.; Corman V. M.; Roppert P. L.; Goldmann N.; Kepper R.; Muller S. F.; Volker C.; de Souza A. J. S.; Gomes-Gouvea M. S.; Moreira-Soto A.; Stocker A.; Nassal M.; Franke C. R.; Rebello Pinho J. R.; Soares M.; Geyer J.; Lemey P.; Drosten C.; Netto E. M.; Glebe D.; Drexler J. F. (2018) A novel hepatitis B virus species discovered in capuchin monkeys sheds new light on the evolution of primate hepadnaviruses. J. Hepatol. 68 (6), 1114–1122. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheit T.; Sekkat S.; Cova L.; Chevallier M.; Petit M. A.; Hantz O.; Lesenechal M.; Benslimane A.; Trepo C.; Chemin I. (2002) Experimental transfection of Macaca sylvanus with cloned human hepatitis B virus. J. Gen. Virol. 83 (7), 1645–9. 10.1099/0022-1317-83-7-1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupinay T.; Gheit T.; Roques P.; Cova L.; Chevallier-Queyron P.; Tasahsu S. I.; Le Grand R.; Simon F.; Cordier G.; Wakrim L.; Benjelloun S.; Trepo C.; Chemin I. (2013) Discovery of naturally occurring transmissible chronic hepatitis B virus infection among Macaca fascicularis from Mauritius Island. Hepatology 58 (5), 1610–20. 10.1002/hep.26428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwitz B. J.; Wettengel J. M.; Muck-Hausl M. A.; Ringelhan M.; Ko C.; Festag M. M.; Hammond K. B.; Northrup M.; Bimber B. N.; Jacob T.; Reed J. S.; Norris R.; Park B.; M?ller-Tank S.; Esser K.; Greene J. M.; Wu H. L.; Abdulhaqq S.; Webb G.; Sutton W. F.; Klug A.; Swanson T.; Legasse A. W.; Vu T. Q.; Asokan A.; Haigwood N. L.; Protzer U.; Sacha J. B. (2017) Hepatocytic expression of human sodium-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide enables hepatitis B virus infection of macaques. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 2146. 10.1038/s41467-017-01953-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter E.; Keist R.; Niederost B.; Pult I.; Blum H. E. (1996) Hepatitis B virus infection of tupaia hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo. Hepatology 24 (1), 1–5. 10.1002/hep.510240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayesh M. E. H.; Ezzikouri S.; Chi H.; Sanada T.; Yamamoto N.; Kitab B.; Haraguchi T.; Matsuyama R.; Nkogue C. N.; Hatai H.; Miyoshi N.; Murakami S.; Tanaka Y.; Takano J. I.; Shiogama Y.; Yasutomi Y.; Kohara M.; Tsukiyama-Kohara K. (2017) Interferon-beta response is impaired by hepatitis B virus infection in Tupaia belangeri. Virus Res. 237, 47–57. 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Schwarzenberger P.; Yang F.; Zhang J.; Su J.; Yang C.; Cao J.; Ou C.; Liang L.; Shi J.; Yang F.; Wang D.; Wang J.; Wang X.; Ruan P.; Li Y. (2012) Experimental chronic hepatitis B infection of neonatal tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri chinensis): a model to study molecular causes for susceptibility and disease progression to chronic hepatitis in humans. Virol. J. 9, 170. 10.1186/1743-422X-9-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.; Ruan P.; Ou C.; Su J.; Cao J.; Luo C.; Tang Y.; Wang Q.; Qin H.; Sun W.; Li Y. (2015) Chronic hepatitis B virus infection and occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri chinensis). Virol. J. 12, 26. 10.1186/s12985-015-0256-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan P.; Yang C.; Su J.; Cao J.; Ou C.; Luo C.; Tang Y.; Wang Q.; Yang F.; Shi J.; Lu X.; Zhu L.; Qin H.; Sun W.; Lao Y.; Li Y. (2013) Histopathological changes in the liver of tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri chinensis) persistently infected with hepatitis B virus. Virol. J. 10, 333. 10.1186/1743-422X-10-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers J.; Smolec J. M.; Snyder R. (1978) A virus similar to human hepatitis B virus associated with hepatitis and hepatoma in woodchucks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 75 (9), 4533–7. 10.1073/pnas.75.9.4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Q.; Summers J.; Burch J. B.; Mason W. S. (1997) Major differences between WHV and HBV in the regulation of transcription. Virology 229 (1), 25–35. 10.1006/viro.1996.8422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R.; Donello J. E.; Trono D.; Hope T. J. (1999) Woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element enhances expression of transgenes delivered by retroviral vectors. J. Virol. 73 (4), 2886–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B. J.; Tian Y. J.; Meng Z. J.; Jiang M.; Wei B. Q.; Tao Y. Q.; Fan W.; Li A. Y.; Bao J. J.; Li X. Y.; Zhang Z. M.; Wang Z. D.; Wang H.; Roggendorf M.; Lu M. J.; Yang D. L. (2011) Establishing a new animal model for hepadnaviral infection: susceptibility of Chinese Marmota-species to woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 92 (3), 681–91. 10.1099/vir.0.025023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote P. J.; Korba B. E.; Miller R. H.; Jacob J. R.; Baldwin B. H.; Hornbuckle W. E.; Purcell R. H.; Tennant B. C.; Gerin J. L. (2000) Effects of age and viral determinants on chronicity as an outcome of experimental woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. Hepatology 31 (1), 190–200. 10.1002/hep.510310128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant B. C.; Toshkov I. A.; Peek S. F.; Jacob J. R.; Menne S.; Hornbuckle W. E.; Schinazi R. D.; Korba B. E.; Cote P. J.; Gerin J. L. (2004) Hepatocellular carcinoma in the woodchuck model of hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology 127 (5), S283–93. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank I.; Budde C.; Fiedler M.; Dahmen U.; Viazov S.; Lu M.; Dittmer U.; Roggendorf M. (2007) Acute resolving woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) infection is associated with a strong cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response to a single WHV core peptide. J. Virol. 81 (13), 7156–63. 10.1128/JVI.02711-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M.; Yao X.; Xu Y.; Lorenz H.; Dahmen U.; Chi H.; Dirsch O.; Kemper T.; He L.; Glebe D.; Gerlich W. H.; Wen Y.; Roggendorf M. (2008) Combination of an antiviral drug and immunomodulation against hepadnaviral infection in the woodchuck model. J. Virol. 82 (5), 2598–603. 10.1128/JVI.01613-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinska A. D.; Johrden L.; Zhang E.; Fiedler M.; Mayer A.; Wildner O.; Lu M.; Roggendorf M. (2012) DNA prime-adenovirus boost immunization induces a vigorous and multifunctional T-cell response against hepadnaviral proteins in the mouse and woodchuck model. J. Virol. 86 (17), 9297–310. 10.1128/JVI.00506-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinska A. D.; Zhang E.; Johrden L.; Liu J.; Seiz P. L.; Zhang X.; Ma Z.; Kemper T.; Fiedler M.; Glebe D.; Wildner O.; Dittmer U.; Lu M.; Roggendorf M. (2013) Combination of DNA prime–adenovirus boost immunization with entecavir elicits sustained control of chronic hepatitis B in the woodchuck model. PLoS Pathog. 9 (6), e1003391 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W. S.; Seal G.; Summers J. (1980) Virus of Pekin ducks with structural and biological relatedness to human hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 36 (3), 829–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiner K. M.; Urban S.; Schaller H. (1998) Carboxypeptidase D (gp180), a Golgi-resident protein, functions in the attachment and entry of avian hepatitis B viruses. J. Virol. 72 (10), 8098–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg H. C.; Lee H. B.; Li J.; Tan F.; Skidgel R.; Wands J. R.; Tong S. (2001) A short sequence within domain C of duck carboxypeptidase D is critical for duck hepatitis B virus binding and determines host specificity. J. Virol. 75 (22), 10630–42. 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10630-10642.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Y.; Zhang B. H.; Theele D.; Litwin S.; Toll E.; Summers J. (2003) Single-cell analysis of covalently closed circular DNA copy numbers in a hepadnavirus-infected liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 (21), 12372–7. 10.1073/pnas.2033898100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kock J.; Rosler C.; Zhang J. J.; Blum H. E.; Nassal M.; Thoma C. (2010) Generation of covalently closed circular DNA of hepatitis B viruses via intracellular recycling is regulated in a virus specific manner. PLoS Pathog. 6 (9), e1001082 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers J.; Smith P. M.; Horwich A. L. (1990) Hepadnavirus envelope proteins regulate covalently closed circular DNA amplification. J. Virol. 64 (6), 2819–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttleman J. S.; Pourcel C.; Summers J. (1986) Formation of the pool of covalently closed circular viral DNA in hepadnavirus-infected cells. Cell 47 (3), 451–60. 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90602-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilbert A. R.; Miller D. S.; Scougall C. A.; Turnbull H.; Burrell C. J. (1996) Kinetics of duck hepatitis B virus infection following low dose virus inoculation: one virus DNA genome is infectious in neonatal ducks. Virology 226 (2), 338–45. 10.1006/viro.1996.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion P. L.; Salazar F. H.; Winters M. A.; Colonno R. J. (2002) Potent efficacy of entecavir (BMS-200475) in a duck model of hepatitis B virus replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 (1), 82–8. 10.1128/AAC.46.1.82-88.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster W. K.; Miller D. S.; Scougall C. A.; Kotlarski I.; Colonno R. J.; Jilbert A. R. (2005) Effect of antiviral treatment with entecavir on age- and dose-related outcomes of duck hepatitis B virus infection. J. Virol. 79 (9), 5819–32. 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5819-5832.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari F. V.; Pinkert C. A.; Milich D. R.; Filippi P.; McLachlan A.; Palmiter R. D.; Brinster R. L. (1985) A transgenic mouse model of the chronic hepatitis B surface antigen carrier state. Science 230 (4730), 1157–60. 10.1126/science.3865369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari F. V.; Klopchin K.; Moriyama T.; Pasquinelli C.; Dunsford H. A.; Sell S.; Pinkert C. A.; Brinster R. L.; Palmiter R. D. (1989) Molecular pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus transgenic mice. Cell 59 (6), 1145–56. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90770-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churin Y.; Roderfeld M.; Stiefel J.; Wurger T.; Schroder D.; Matono T.; Mollenkopf H. J.; Montalbano R.; Pompaiah M.; Reifenberg K.; Zahner D.; Ocker M.; Gerlich W.; Glebe D.; Roeb E. (2014) Pathological impact of hepatitis B virus surface proteins on the liver is associated with the host genetic background. PLoS One 9 (3), e90608 10.1371/journal.pone.0090608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari F. V.; Filippi P.; McLachlan A.; Milich D. R.; Riggs M.; Lee S.; Palmiter R. D.; Pinkert C. A.; Brinster R. L. (1986) Expression of hepatitis B virus large envelope polypeptide inhibits hepatitis B surface antigen secretion in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 60 (3), 880–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles P. N.; Fey G.; Chisari F. V. (1992) Tumor necrosis factor alpha negatively regulates hepatitis B virus gene expression in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 66 (6), 3955–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann F.; Churin Y.; Tschuschner A.; Reifenberg K.; Glebe D.; Roderfeld M.; Roeb E. (2015) Genomic Methylation Inhibits Expression of Hepatitis B Virus Envelope Protein in Transgenic Mice: A Non-Infectious Mouse Model to Study Silencing of HBV Surface Antigen Genes. PLoS One 10 (12), e0146099 10.1371/journal.pone.0146099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti L. G.; Martinez V.; Loh Y. T.; Rogler C. E.; Chisari F. V. (1994) Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid particles do not cross the hepatocyte nuclear membrane in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 68 (9), 5469–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milich D. R.; Jones J.; Hughes J.; Maruyama T. (1993) Role of T-cell tolerance in the persistence of hepatitis B virus infection. J. Immunother. 14 (3), 226–33. 10.1097/00002371-199310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milich D. R.; Jones J. E.; Hughes J. L.; Maruyama T.; Price J.; Melhado I.; Jirik F. (1994) Extrathymic expression of the intracellular hepatitis B core antigen results in T cell tolerance in transgenic mice. J. Immunol. 152 (2), 455–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milich D. R.; Jones J. E.; Hughes J. L.; Price J.; Raney A. K.; McLachlan A. (1990) Is a function of the secreted hepatitis B e antigen to induce immunologic tolerance in utero?. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87 (17), 6599–603. 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terazawa S.; Kojima M.; Yamanaka T.; Yotsumoto S.; Okamoto H.; Tsuda F.; Miyakawa Y.; Mayumi M. (1991) Hepatitis B virus mutants with pre-core-region defects in two babies with fulminant hepatitis and their mothers positive for antibody to hepatitis B e antigen. Pediatr. Res. 29 (1), 5–9. 10.1203/00006450-199101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. M.; Koike K.; Saito I.; Miyamura T.; Jay G. (1991) HBx gene of hepatitis B virus induces liver cancer in transgenic mice. Nature 351 (6324), 317–20. 10.1038/351317a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike K.; Moriya K.; Iino S.; Yotsuyanagi H.; Endo Y.; Miyamura T.; Kurokawa K. (1994) High-level expression of hepatitis B virus HBx gene and hepatocarcinogenesis in transgenic mice. Hepatology 19 (4), 810–9. 10.1002/hep.1840190403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D. Y.; Moon H. B.; Son J. K.; Jeong S.; Yu S. L.; Yoon H.; Han Y. M.; Lee C. S.; Park J. S.; Lee C. H.; Hyun B. H.; Murakami S.; Lee K. K. (1999) Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis B virus X-protein. J. Hepatol. 31 (1), 123–32. 10.1016/S0168-8278(99)80172-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billet O.; Grimber G.; Levrero M.; Seye K. A.; Briand P.; Joulin V. (1995) In vivo activity of the hepatitis B virus core promoter: tissue specificity and temporal regulation. J. Virol. 69 (9), 5912–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. H.; Finegold M. J.; Shen R. F.; DeMayo J. L.; Woo S. L.; Butel J. S. (1990) Hepatitis B virus transactivator X protein is not tumorigenic in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 64 (12), 5939–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfumo S.; Amicone L.; Colloca S.; Giorgio M.; Pozzi L.; Tripodi M. (1992) Recognition efficiency of the hepatitis B virus polyadenylation signals is tissue specific in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 66 (11), 6819–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farza H.; Hadchouel M.; Scotto J.; Tiollais P.; Babinet C.; Pourcel C. (1988) Replication and gene expression of hepatitis B virus in a transgenic mouse that contains the complete viral genome. J. Virol. 62 (11), 4144–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki K.; Miyazaki J.; Hino O.; Tomita N.; Chisaka O.; Matsubara K.; Yamamura K. (1989) Expression and replication of hepatitis B virus genome in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86 (1), 207–11. 10.1073/pnas.86.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti L. G.; Matzke B.; Schaller H.; Chisari F. V. (1995) High-level hepatitis B virus replication in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 69 (10), 6158–69. 10.1159/000084312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti L. G.; Ishikawa T.; Hobbs M. V.; Matzke B.; Schreiber R.; Chisari F. V. (1996) Intracellular inactivation of the hepatitis B virus by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunity 4 (1), 25–36. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti L. G.; Morris A.; Mendez H.; Koch R.; Silverman R. H.; Williams B. R.; Chisari F. V. (2002) Interferon-regulated pathways that control hepatitis B virus replication in transgenic mice. J. Virol. 76 (6), 2617–21. 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2617-2621.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti L. G.; Inverso D.; Sironi L.; Di Lucia P.; Fioravanti J.; Ganzer L.; Fiocchi A.; Vacca M.; Aiolfi R.; Sammicheli S.; Mainetti M.; Cataudella T.; Raimondi A.; Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G.; Protzer U.; Ruggeri Z. M.; Chisari F. V.; Isogawa M.; Sitia G.; Iannacone M. (2015) Immunosurveillance of the liver by intravascular effector CD8(+) T cells. Cell 161 (3), 486–500. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitia G.; Isogawa M.; Kakimi K.; Wieland S. F.; Chisari F. V.; Guidotti L. G. (2002) Depletion of neutrophils blocks the recruitment of antigen-nonspecific cells into the liver without affecting the antiviral activity of hepatitis B virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 (21), 13717–22. 10.1073/pnas.172521999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitia G.; Isogawa M.; Iannacone M.; Campbell I. L.; Chisari F. V.; Guidotti L. G. (2004) MMPs are required for recruitment of antigen-nonspecific mononuclear cells into the liver by CTLs. J. Clin. Invest. 113 (8), 1158–67. 10.1172/JCI200421087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitia G.; Iannacone M.; Aiolfi R.; Isogawa M.; van Rooijen N.; Scozzesi C.; Bianchi M. E.; von Andrian U. H.; Chisari F. V.; Guidotti L. G. (2011) Kupffer cells hasten resolution of liver immunopathology in mouse models of viral hepatitis. PLoS Pathog. 7 (6), e1002061 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]