Abstract

Background:

Cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure are characterized by increased late sodium current and abnormal Ca2+ handling. Ranolazine, a selective inhibitor of the late sodium current, can reduce sodium accumulation and Ca2+ overload. In this study, we investigated the effects of ranolazine on pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure in mice.

Methods and Results:

Inhibition of late sodium current with the selective inhibitor ranolazine suppressed cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and improved heart function assessed by echocardiography, hemodynamics and histological analysis in mice exposed to chronic pressure overload induced by transverse aortic constriction (TAC). Ca2+ imaging of ventricular myocytes from TAC mice revealed both abnormal SR Ca2+ release and increased SR Ca2+ leak. Ranolazine restored aberrant SR Ca2+ handling induced by pressure overload. Ranolazine also suppressed Na+ overload induced in the failing heart, and restored Na+-induced Ca2+ overload in an a sodium calcium exchanger (NCX)-dependent manner. Ranolazine suppressed the Ca2+-dependent calmodulin (CaM)/CaMKII/MEF2 and CaM/CaMKII/calcineurin/NFAT hypertrophy signaling pathways triggered by pressure overload. Pressure overload also prolonged endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress leading to ER-initiated apoptosis, while inhibition of late sodium current or NCX relieved ER stress and ER-initiated cardiomyocyte apoptosis.

Conclusions:

Our study demonstrates that inhibition of late sodium current with ranolazine improves pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and systolic and diastolic function by restoring Na+ and Ca2+ handling, inhibiting the downstream hypertrophic pathways and ER stress. Inhibition of late sodium current may provide a new treatment strategy for cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure.

Keywords: Heart failure; hypertrophy; INa,L; Ca2+ transient; ranolazine

Introduction

The prevalence of heart failure (HF) has increased over the last decade (Lou et al., 2012). Although pharmacotherapies significantly improve survival, the prognosis of HF is still relatively poor (Kaye and Krum, 2007). Defective intracellular Ca2+ handling is central to the depressed contractility and diminished contractile reserve observed in heart failure (Wehrens and Marks, 2004). Elevated Ca2+ levels lead to increased Ca2+ binding with inactive calmodulin (CaM) to form active CaM, and hypertrophic cascades involving Ca2+/CaM/CaMKII/MEF2 and CaM/CaMKII/calcineurin/NFAT may be triggered (Zhang et al., 2007). In addition, excessive Ca2+ levels increase phosphorylation of type II ryanodine receptor (RyR2) and more Ca2+ leaks from the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum through RyR2, aggravating cytoplasmic Ca2+ overload (Fischer et al., 2015; Fischer et al., 2013; Popescu et al., 2016). Furthermore, cytoplasmic Ca2+ overload and exhausted Ca2+ stores disturb the environment for protein folding and lead to unfolded protein response(UPR) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (Hayashi and Su, 2007). ER-initiated apoptosis contributes to cardiac myocyte apoptosis in failing hearts (Ni et al., 2011).

Thus, an early and sustained reduction in intracellular Ca2+ may slow the progression of heart failure. However, long-term reduction of intracellular Ca2+ overload with the L-type Ca2+ channel blockers have the potential for adverse effects including bradycardia, hypotension, and exercise intolerance (St-Onge et al., 2014). An alternative therapeutic option to reduce intracellular Ca2+ overload in the failing heart is pharmacological inhibition of the late Na+ current (INa,L) using a clinically available, selective inhibitor, ranolazine. INa,L constitutes a very small portion of the inward sodium current under physiological conditions (Glynn et al., 2015). However, during pathological situations such as pressure overload, INa,L increases and generates a considerable amount of sodium inward current, causing intracellular Ca2+ accumulation (Armoundas et al., 2003; Maltsev et al., 2007; Onal et al., 2017; Toischer et al., 2013). Ranolazine is an anti-ischemic and antianginal agent that inhibits the late Na+ current, thereby normalizing intracellular Na+ and potentiating Ca2+ extrusion from the cytosol via the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), ultimately relieving Ca2+ overload (Gaborit et al., 2005).

Ranolazine has shown beneficial effects in improving diastolic function in a HF dog model and in patients with coronary artery disease (Figueredo et al., 2011; Rastogi et al., 2008). However, the mechanism of long-term INa,L inhibition with ranolazine in HF has not been fully explored. Toward this goal, transverse aortic constriction (TAC) induced pressure overload mice were implanted with the subcutaneous osmotic minipumps containing ranolazine or vehicle. Our data demonstrate that ranolazine prevents pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure and restores aberrant intracellular Na+ and Ca2+ handling. In addition, these data revealed that ranolazine inhibits Ca2+/CaMKII dependent signaling pathways and ER stress induced in failing hearts. Our study prompts ranolazine as a potential candidate for treating pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Ranolazine (R6152), tetracaine (T7508), Claycomb medium (51800C) and Liberase™ (5401151001) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Veratridine (sc-201075) and SBFI-AM (sc-215841A), NCX (sc-32881) and GAPDH (sc-293335) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas, USA). Caffeine (14118) was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, Michigan. USA). SEA0400 (A3811) was from Apex Bio Technology (Houston, Texas, USA). Isoproterenol hydrochloride (I0260) was from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). Bay K8644 (B112) was purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, Texas, USA). Fluo 4-AM (F14201) and CaMKII t286 (PA5-35501) antibody were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Actin tracker green (C1033) was from Beyotime Technology (Shanghai, China). Osmotic minipumps (1004) were from Alzet (Cupertino, California, USA). Antibodies for GRP78 (11587-1-AP), MEF2D (14353-1-AP), CHOP (15204-1-AP), ANP (27426-1-AP) and CaMKII total (15443-1-AP) were purchased from Proteintech (Wuhan, Hubei, China). Antibodies for BNP (A2179), NFATc3 (A6666) and Histone H3 (Hist3.1, A10880) were from ABclonal Technology (Wuhan, Hubei, China). Antibody for CNα (M03026) was from BOSTER Biological Technology (Wuhan, Hubei, China).

Animal models

All animal experimental protocols complied with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” published by the United States National Institutes of Health. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Research Committee of Tongji Medical College. All animals were housed at the animal care facility of Tongji Medical College at 25ºC with 12/12h light/dark cycles and allowed free access to normal mouse chow and water throughout the study period. Eight-week old male C57BL/6J mice were randomly divided into different groups. Mice were anesthetized by a combination of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection. The detailed protocol of TAC was as previously described and the needle size for constriction is 27G (deAlmeida et al., 2010). Ranolazine dissolved in saline was given by subcutaneous minipumps (40mg/kg/d). The dosage was chosen according to the CARISA trial(Chaitman, 2004). In vitro study, 10 μmol/L ranolazine was used, because it is within the range of therapeutic plasma levels and inhibitory concentrations of 50% for inhibition of INa,L (6 to 15 μmol/l) (Toischer et al., 2013).

Evaluation of cardiac function

An ultrasound machine with high resolution and equipped with a 30 MHz scan head was used to detect mice ventricular dimensions (Vevo1100; VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada). Echocardiography was performed on anesthetized mice as described previously (Toischer et al., 2013).

In vivo hemodynamics

Mice were anaesthetized. A pressure–volume catheter (Millar 1.4F, SPR 835, Millar Instruments, Inc. Houston, TX, USA) was inserted into the left ventricle through the carotid artery for measurement of intraventricular pressure and volume as described previously (Cingolani et al., 2003).

Histological analysis

Myocardial tissue was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature and embedded in paraffin. Heart sections were performed with WGA, TUNEL, Masson, Sirius red, hematoxylin/eosin following the instructions of manufacturers.

Preparation of isolated cardiac myocytes

The mouse was anesthetized with a mixture of pentobarbital and heparin intraperitoneally. Mouse chest cavity was exposed using scissors and the heart was immediately removed and immersed into ice-cold Tyrode’s buffer containing NaCl 125 mmol/L, KCl 5 mmol/L, HEPES 15 mmol/L, MgCl2 1.2 mmol/L, and glucose 10 mmol/L, pH 7.35~7.38 (at 25°C), saturated oxygen. The aorta was then quickly mounted on the cannula. The heart was perfused with Tyrode buffer containing NaCl 125 mmol/L, KCl 5 mmol/L, HEPES 15 mmol/L, MgCl2 1.2 mmol/L, taurine 6 mmol/L, BDM 7.5 mmol/L and glucose 10 mmol/L, pH 7.35~7.38 (at 25°C) for 5 minutes at 37°C. The perfusion buffer was then switched to enzymatic buffer (Tyrode buffer supplemented with 1mg/40ml liberase). Constant perfusion pressure of 120 cm H2O was applied. When the drop rate accelerated suddenly, the perfusion was stopped. The atrial part was discarded while the ventricle part was cut into small tissue pieces and was pipetted gently. The digestion was stopped using DMEM containing 10% FBS when abundant isolate rod-like cardiac myocytes were visible by microscopy.

Calcium imaging studies

Isolated ventricular myocytes were loaded with 5 μM Fluo 4-AM in Tyrode’s buffer containing (in mM): 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 10 glucose, 1.8 CaCl2 (pH 7.4, 37°C) in 37°C for 30min. Excess dye was washed away with Tyrode’s buffer for 15 min. Myocytes were field stimulated at 0.5 Hz and the Metamorph imaging system from Universal Imaging Corporation (West, Chester, PA) was used to detect fluorescence at 488nm excitation. The background was subtracted. The Ca2+ transient was denoted as F/F0, where F0 is the baseline fluorescence as previously described (de Almeida et al., 2013).

Myocytes were paced in Tyrode’s buffer containing 1.8mM Ca2+. The perfusion was then switched to Tyrode’s buffer containing 1mM tetracaine and 0 mM Ca2+ to block SR leak through RyR2 for 5 min. Then the perfusion was switched to normal Tyrode’s buffer plus 10 mM caffeine to empty sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic Ca2+ storage. The percentage of SR leak was then calculated as previously described (Chelu et al., 2009).

Determination of intracellular Na+ concentration

Isolated ventricular myocytes were loaded with 5 μM sodium-binding benzofuran isophthalate–AM (SBFI-AM) in Tyrode’s buffer in 37ºC for 30 min. Myocytes were washed with Tyrode’s buffer for 15 min and were excited at 340 nm and 380 nm respectively. The background fluoresence was determined as the cell before loading. The ratio F340/F380 was calculated from the background-subtracted emission intensities to represent intracellular Na+ as previously described (Wagner et al., 2006).

Cell culture

HL-1 cells were cultured using Claycomb method. Claycomb medium was purchased from Sigma and was supplemented with 100 μM norepinephrine, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 4 mM L-glutamine. HL-1 cells were pretreated with 20μM isoproterenol hydrochloride (Iso), (1μM) Bay K8644 (Bay), 30 μM veratridine (Ver) for 24 hours, respectively. Ranolazine (Ran) (10 μM), SEA0400 (SEA) (1 μM), nifedipine (Nif) (1 μM) were incubated for 24 hours, followed by harvest.

Flow cytometry

Cardiomyocyte apoptosis was evaluated using Annexin-V/PI apoptotic assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (KGA108; Jiangsu KeyGEN BioTECH Corp., Ltd, Nanjing, China).

Extraction of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins

Extraction of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins from myocardium was performed using hypotonic cytoplasmic extraction (CE) buffer and high salt nuclear extraction (NE) buffer. Briefly, homogenize 50mg tissue using a TissueLyser LT (Qiagen N.V., Venlo, The Netherlands), add 500μl CE buffer (HEPES 10 mM, NaF 20 mM, Na3VO4 1mM, KCl 60 mM, EDTA 1mM, EGTA 1mM, DTT 2 mM, with the protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors), incubate the in EP tube on ice for 10 min, add ice-cold 50μl 5% NP-40, vortex and incubate on ice for 1 min, centrifuge 1500g for 5 min, transfer supernatant to a new EP tube, centrifuge 16000g for 20min, the supernatant is a cytoplasmic fraction. Add 1ml of CE buffer (without protease and phosphatase inhibitors) to pellet above, re-suspend and wash the pellet 3 times by centrifuging 1500g for 5 min, remove supernatant, add 250μl NE buffer (HEPES 10mM, NaF 20 mM, Na3VO4 1 mM, KCl 60 mM, EDTA 1 mM, EGTA 1 mM, DTT 2mM, NaCl 420mM, glycerol 0.2mM, with protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitors), re-suspend and incubate on ice for 10min, sonicate 3 times for 1 second each on ice, centrifuge 16000g for 20 min, the supernatant is the nuclear fraction.

For nuclear extraction of cultured cells, cells were scraped in cold phosphate-buffered saline, spun down (12,000g, 30 s), re-suspended in 400 μl CE buffer with 25 μl of 10% NP-40 and then spun down. Nuclei in the pellet were re-suspended in NE buffer, and protein concentration was determined.

Western blot analysis

Cells and cardiac tissue were extracted using Protein or IP lysate (Beyotime Technology, Shanghai, China) containing 1:100 protease inhibitors and 1:100 phosphatase inhibitors, and the protein concentration was calculated by BCA kit (Boster, Wuhan, China). 10% and 6-12% gradient gels were used. Antibodies were diluted by 1:1000. Gel Pro analysis software was used for quantification.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reverse transcription was performed using MultiScribe system (ABI, Waltham, MA) for cDNA. 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System was used for real-time PCR. The mRNA level was compared according to the comparative threshold cycle (2−ΔΔCt) method. Primers were designed using Primer 5.0 (PREMIER Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA) and verified using MFE 2.0 system (Qu et al., 2012). The primer sequences are listed in Supporting Information Table 3.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Comparisons among groups were performed by Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis using the Student-Newman-Keuls method. Significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

Results

Ranolazine blunts cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and improves impaired cardiac function induced by pressure overload

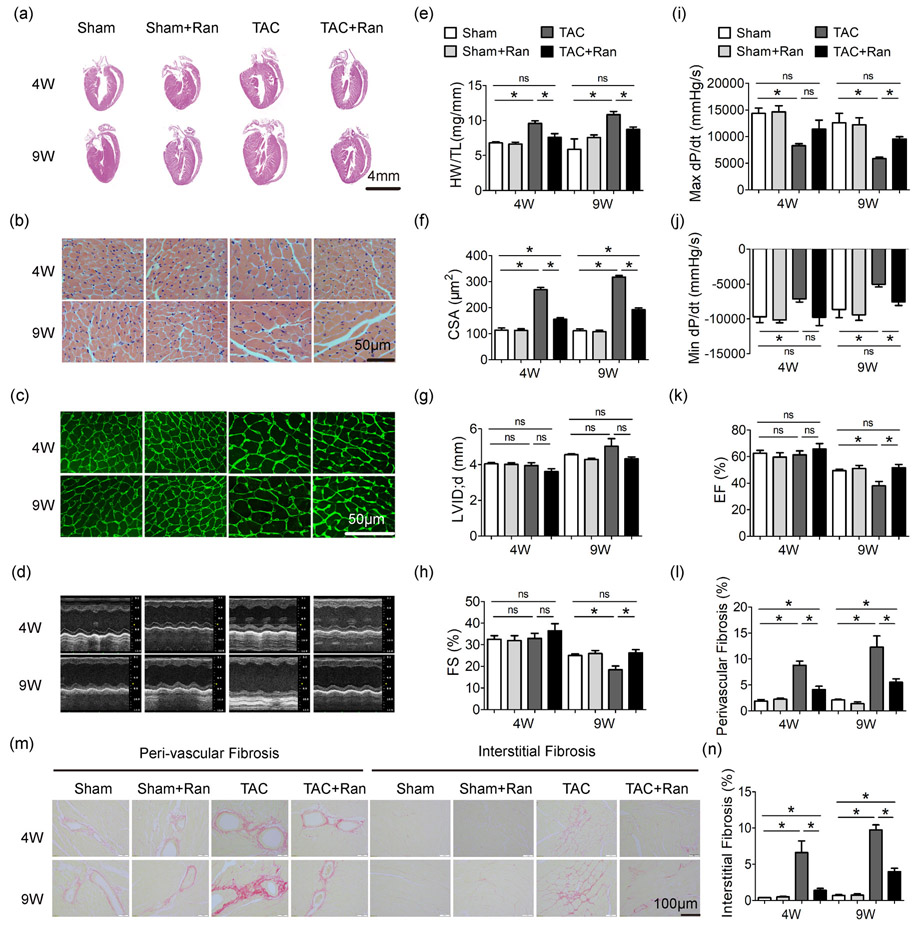

We subjected male C57BL/6J mice to constriction of the transverse aorta (TAC) or to sham surgery for 4-9 weeks. The mice were concurrently subcutaneously implanted with osmotic minipumps of ranolazine (40mg/kg/d) or vehicle saline. As shown in Figure 1, TAC induced left ventricular and cellular hypertrophy. Both the hypertrophy and the chamber remodeling were inhibited by ranolazine in TAC mice (Figure 1a-g), whereas ranolazine had no impact on sham-operated groups. TAC also induced myocardial fibrosis which was suppressed by ranolazine (Figure 1l-n).

Figure 1.

Ranolazine blunts pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. (a) Examples of HE staining of heart sections. Examples of HE staining (b) and Wheat germ agglutinin staining (c) of heart cross-sections. (d) M-mode echocardiogram. (e) Statistics of HW/TL. (f) Statistics of CSA. (g) Statistics of LVID;d by echocardiography. (h) Statistics of FS by echocardiography. Quantification of max dP/dt, peak rate of pressure increase (i), and min dP/dt, peak rate of pressure decline (j), measured by aortic catheterization. (k) Statistics of EF by echocardiography. Sirius red stained myocardium section (m) and quantification (l and n) of cardiac fibrosis. Mice number was 5–14 per group. One-way ANOVA was performed for groups with the same intervention time; e.g., in (e), HW/TL values of Sham, Sham + Ran, TAC and TAC + Ran at 4 weeks were compared using one-way ANOVA, while HW/TL values of Sham, Sham + Ran, TAC and TAC + Ran at 9 weeks were compared using another one-way ANOVA independently. The same went for the rest of statistics. All data were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (n ≥ 5; *p < 0.05). ANOVA: analysis of variance; CSA: cross sectional area; EF: ejection fraction; FS: fractional shortening; HW/TL: heart weight/tibia length; LVID;d: left ventricular internal diameter at diastole; Ran: ranolazine dyhydrocloride; TAC: transverse aortic constriction surgery; 4 W, 9 W: 4 weeks or 9 weeks after TAC operation

Detailed examination of heart function was carried out by invasive pressure-volume analysis. As shown in Figure 1i,j, cardiac function of TAC mice was decreased in comparison with sham group as evidenced by the markedly reduced dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin, and administration with ranolazine resulted in a restoration in cardiac function. Serial echocardiography showed reduced fractional shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF) in mice 9 weeks after TAC surgery, and ranolazine preserved both FS and EF in TAC mice (Figure 1d,g,h,k and Supporting Information Table 1), indicating ranolazine prevented pressure overload induced heart failure.

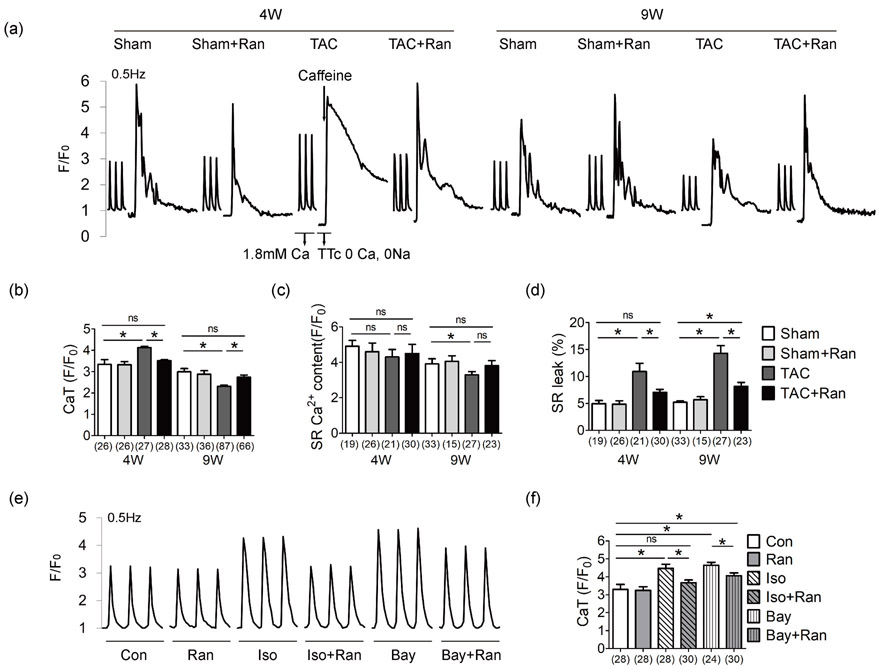

Ranolazine restores aberrant SR Ca2+ handling induced by pressure overload

We determined intracellular Ca2+ state in situ. Ventricular myocytes were isolated and paced at 0.5 Hz to obtain steady-state Ca2+ handling. There was an increase in steady-state Ca2+ transient amplitude (CaT) in myocytes isolated from mice 4 weeks after TAC, and a reduction in CaT was observed in myocytes from mice 9 weeks after TAC operation (Figure 2a,b). Rapid application of tetracaine (TTc) and caffeine revealed decreased SR Ca2+ content at 9W (Figure 2c), and increased SR Ca2+ leakage was observed (Figure 2a,d) in myocytes from mice both at 4W and 9W after TAC. Administration of ranolazine treatment restored the altered Ca2+ kinetics induced by pressure overload (Figure 2 and Supporting Information Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Ranolazine restores aberrant intracellular Ca2+ induced by pressure overload. (a) Representative Ca2+ recordings obtained in ventricular myocytes stimulated at 0.5 Hz. Ca2+ transient was recorded with Tyrode’s perfusion containing 1.8 mM Ca2+. SR leak was measured by switching the perfusion to 1 mM TTc buffer containing 0 Ca2+ and 0 Na+ to block SR leak, and caffeine was applied to empty SR Ca2+ storage. Quantification of CaT amplitude (b), SR Ca2+ content (c) and SR leak percentage (d). The Ca2+ transient recordings (e) and quantification (f) of the CaT amplitude in cardiomyocytes isolated from control C57/BL mice under different stimulus. Numbers indicate the number of cells for each condition (3–5 mice per group). Myocytes were concurrently treated with Bay/Iso and Ran 1 hr before the fluorescence detection. Ran, 10 μM; Iso, 20 μM; Bay, Bay K8644, LTCC activator, 1 μM. One-way ANOVA was performed for groups with the same intervention time; e.g., in (b), amplitude of CaT values of Sham, Sham + Ran, TAC and TAC + Ran at 4 weeks were compared using one-way ANOVA, while CaT values of Sham, Sham + Ran, TAC, and TAC + Ran at 9 weeks were compared using another one-way ANOVA independently. The same applied to (c,d). One-way ANOVA was performed for the analysis of (f). All data were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (*p < 0.05). ANOVA: analysis of variance; Bay: Bay K8644; CaT: Ca2+ transient; Iso, isoproterenol hydrochloride; LTCC: L-type calcium channel; Ran: ranolazine dyhydrochloride; TAC: transverse aortic constriction surgery; TTc: tetracaine

To investigate the effect of ranolazine in vitro, cardiomyocytes were isolated from control C57/BL mice, and treated with isoproterenol hydrochloride (Iso), a hypertrophic stimulus and L-type calcium channel (LTCC) activator Bay K8644 (Bay) which can induce intracellular Ca2+ overload. Ranolazine reduced the increasing CaT amplitude stimulated by Iso and Bay (Figure 2e,f). Overall, these findings indicate that ranolazine restores aberrant SR Ca2+ storage and Ca2+ release and relieves Ca2+ load induced by pressure overload.

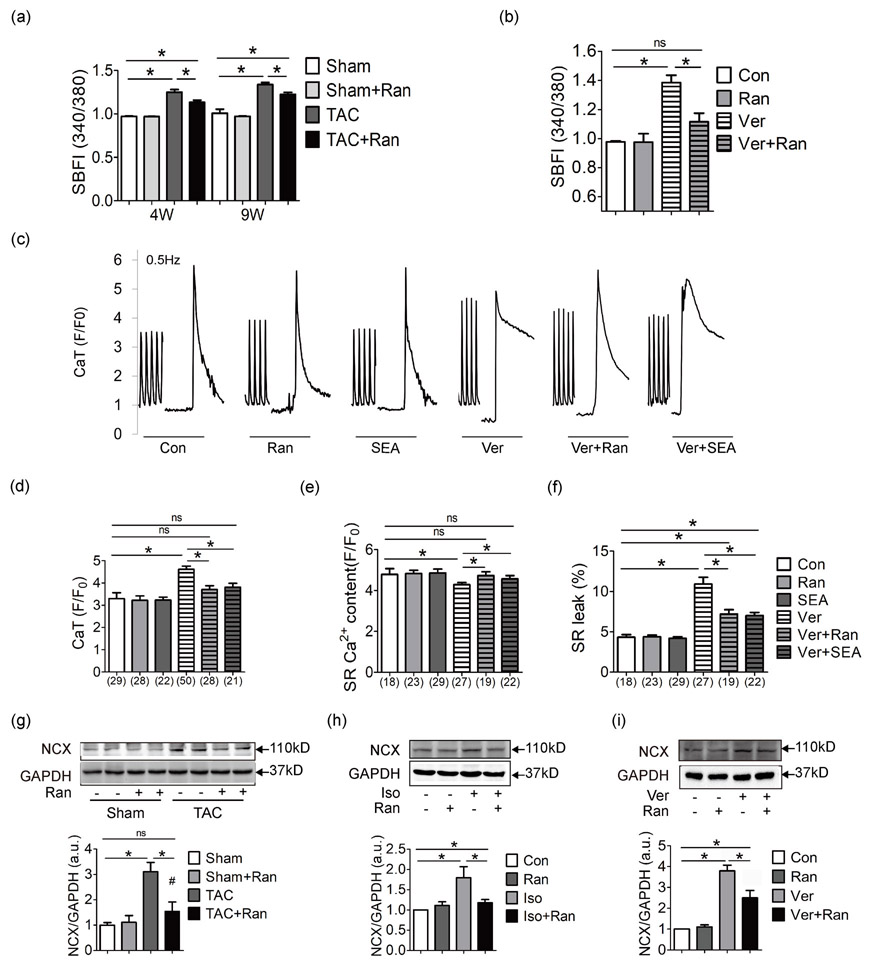

Ranolazine restores aberrant Ca2+ handling induced by Na+ overload

Since ranolazine is an inhibitor of late sodium current, we tested the intracellular Na+ level using SBFI-AM. As shown in Figure 3a, Na+ level was increased in TAC mice both at 4 weeks and 9 weeks, and administration of ranolazine alleviated such Na+ overload. For In vitro study, we used a sodium channel agonist veratridine to induce intracellular Na+ overload in isolated ventricular myocytes of control mice (Brill and Wasserstrom, 1986; Kent et al., 1989), and ranolazine relieved intracellular Na+ overload induced by veratridine (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Ranolazine suppresses Na+ induced Ca2+ overload via NCX in the failing heart. (a) Fluorescence ratio of SBFI-AM staining to mearure intracellular Na+ (3–5 mice per group). (b) Intracellular Na+ change in response to Ver and Ran treatment. Cardiomyocytes were isolated from control C57/BL mice (replicates n ≥ 5 per group). Myocytes were concurrently treated with Ver and Ran 1 hr before the SBFI-AM fluorescence detection. Representative Ca2+ recordings (c) and quantification of CaT amplitude (d), SR Ca2+ content (e) and SR leak percentage (f) of contol C57/BL mouse cardiomyocytes in response to Ver, Ran, and SEA. Drugs were given concurrently to myocytes for 1 hr before Fluo 4-AM fluorescence detection. Numbers indicate the number of cells for each condition. (g) NCX expression in mice after 4 weeks. NCX expression in Iso treated HL-1 cells (h) and Ver treated HL-1 cells (i). HL-1 cells were treated with Iso/Ver and Ran for 24 hr before protein extraction. Each western blot analysis was performed for 3–5 biological repeats. For (a) the 340/380 ratio of Sham, Sham + Ran, TAC and TAC + Ran at 4 weeks were compared using one-way ANOVA, while 340/380 ratio of Sham, Sham + Ran, TAC and TAC + Ran at 9 weeks were compared using another one-way ANOVA independently. One-way ANOVA was applied for the statistic of (b,d-i). All data were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (*p < 0.05). ANOVA: analysis of variance; CaT: Ca2+ transient; Iso: isoproterenol hydrochloride; NCX: sodium calcium exchanger; Ran: ranolazine dyhydrochloride; SBFI-AM: sodium-binding benzofuran isophthalate-AM; SEA: SEA0400; TAC, transverse aortic constriction surgery; Ver: veratridine

Since NCX plays the bridging role between Na+ and Ca2+, SEA0400 (SEA), an inhibitor of NCX activity, was utilized. We investigated the relationship between Na+ overload and Ca2+ signaling in mouse ventricular myocytes. As shown in Figure 3c-f, veratridine increased Ca2+ transient amplitude, impaired SR Ca2+ content and increased SR Ca2+ leak. Both ranolazine and NCX inhibitor were effective to normalize aberrant Ca2+ handling. In addition, ranolazine reduced overexpression of NCX induced in TAC mice, Iso treated HL-1 cells and veratridine treated HL-1 cells (Figure 3g-i).

Together, these data revealed ranolazine suppresses Na+ overload in cardiac hypertrophy, and prevents Na+ induced Ca2+ mishandling in an NCX-dependent manner.

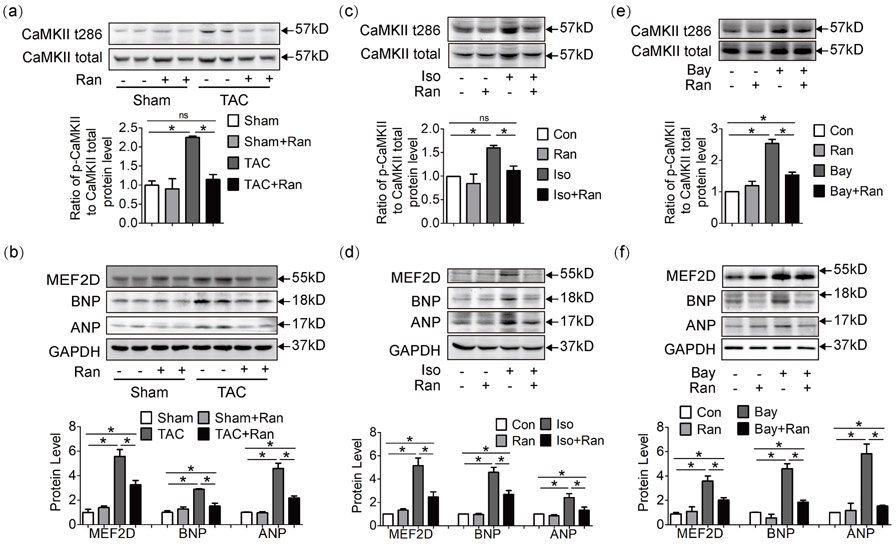

Ranolazine inhibits Ca2+ dependent hypertrophic pathways

Elevated Ca2+ level leads to increased Ca2+ binding with inactive calmodulin (CaM) to form active CaM, which may trigger the hypertrophic Ca2+/CaM/CaMKII/MEF2 cascade. Since aberrant Ca2+ cycling was observed in TAC mice (Figure 2), we tested the activation state of Ca2+ dependent hypertrophic pathway. In hearts exposed to pressure overload, CaMKII was highly phosphorylated at the 286 threonine (Figure 4a). CaMKII-t286 can in turn phosphorylate histone deacetylase (HDAC) and release MEF2D from HDAC transcription suppression. MEF2D upregulated hypertrophic gene expression, as evidenced by atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) from protein (Figure 4b) and mRNA levels (Supporting Information Figure S2A). While in mice treated with ranolazine, this hypertrophic cascade was well inhibited.

Figure 4.

Ranolazine inhibits Ca2+-dependent Ca2+/CaM/CaMKII/MEF2D hypertrophic pathway. (a, b) Western blot analysis of myocardium lysate at 4 weeks. CaMKII was highly phosphorylated in TAC mice, and the downstream hypertrophic markers MEF2D, ANP, and BNP were upregulated, while in ranolazine treated TAC mice, this pathway was inhibited. Hypertrophic markers were also tested in mouse cardiomyocyte cell line HL-1 exposed to Iso (c, d) or Bay (e, f). Each western blot analysis was performed for 3–5 biological repeats. One-way analysis of variance was used for analysis. Data were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (*p < 0.05). ANP: atrial natriuretic peptide; Bay: Bay K8644; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; CaMKII: Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; Iso: isoproterenol hydrochloride; MEF2D: myocyte enhancer factor 2D; TAC: transverse aortic constriction surgery

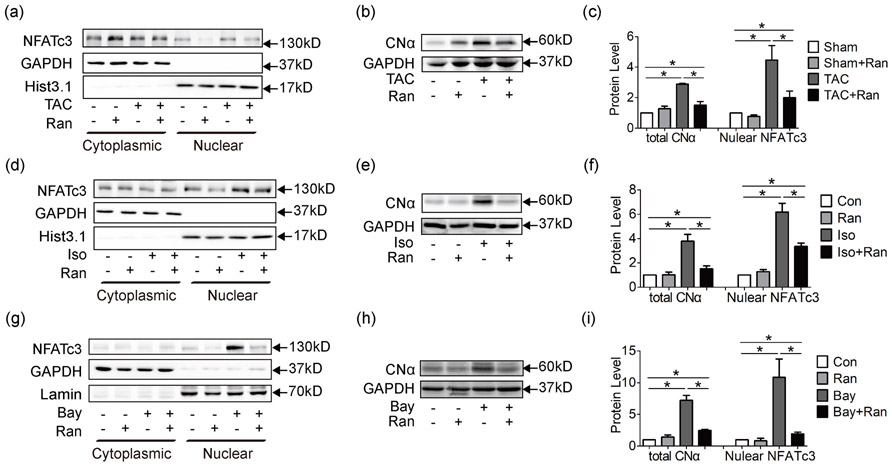

Additionally, activation of the calcineurin/NFAT pathway was observed in TAC mice. NFAT is a group of transcription factors that modulate cell cycle, differentiation and apoptosis (Mognol et al., 2016). Under physiological situations, NFAT stays in the cytoplasm in a phosphorylated state. In response to Ca2+ overload, calcineurin would be activated by p-CaMKII to dephosphorylate NFAT. Dephosphorylated NFAT then enters the nuclei and modulates its target genes. Among the four isoforms of NFAT, NFATc3 is well-documented in mediating the hypertrophic signaling pathway (Wilkins and Molkentin, 2004). In this study, upregulation of calcineurin catalytic α subunit, CNα was detected in whole cell lysate of mouse myocardium (Figure 5b,c), followed by increased nuclear localization of NFATc3 (Figure 5a,c). In mice treated with ranolazine, CNα expression and NFATc3 nuclear localization were significantly reduced.

Figure 5.

Ranolazine inhibits Ca2+ dependent Ca2+/calcineurin/NFAT hypertrophic pathway. (a) Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were extracted from mouse myocardium at 4 weeks for western blot analysis. GAPDH was taken as the cytoplasmic loading control. Histone H3 (Hist3.1) and Lamin B (Lamin) were taken as the nuclear loading control. Data showed that NFATc3 nuclear localization was increased in TAC mice and was significantly reduced by ranolazine. (b) Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate revealed increased expression of calcineurin catalytic α subunit (CNα), which was reduced by ranolazine. (c) showed statistics of (a) and (b). CNα was also upregulated in Iso (e) and Bay (h) treated HL-1 cells, followed by increased nuclear localization of NFATc3 (d,g), and treatment with ranolazine significantly inhibited the calcineurin/NFAT pathway. Statistics were shown in (f) and (i). Each western blot analysis was performed for 3–5 biological repeats. One-way analysis of variance was used for analysis. Data were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (*p < 0.05). GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; NFAT: nuclear factor of activated T-cells; TAC: transverse aortic constriction surgery

In vitro hypertrophic stimuli Iso was applied to HL-1 cells and similar results were achieved for both the CaMKII/MEF2 (Figure 4c,d; Supporting Information Figure S2B and S2C) and the calcineurin/NFAT pathways (Figure 5d-f); indicating hypertrophic pathways induced by Iso were ameliorated by ranolazine.

To verify the anti-hypertrophic effect of ranolazine is by restoring altered Ca2+ handling than other mechanisms, the Ca2+ activator Bay was applied. As shown in Figure 4e,f, Supporting Information Figure 3D and Figure 5g-i, Ca2+/CaM/CaMKII/MEF2 and calcineurin/NFAT pathways were triggered by Ca2+ overload and inhibited by ranolazine. Together, these data indicated that ranolazine probably exerts its protection by inhibiting Ca2+ dependent hypertrophic pathways.

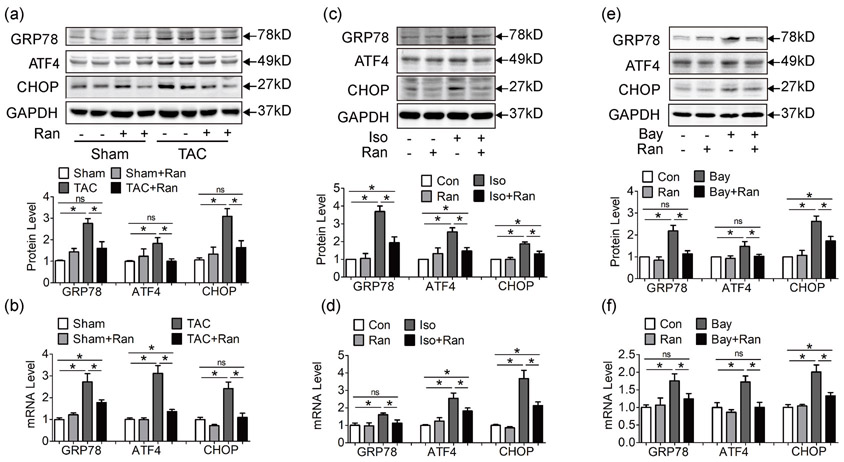

Inhibition of late sodium current inhibits TAC-induced ER stress

Ca2+ overload and exhausted Ca2+ storage leads to unfolded protein response (UPR) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Sustained ER stress activates ER chaperones and CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) expression, leading to cardiac myocyte apoptosis in failing hearts (Okada et al., 2004). Consistent with our previous study, we found that both mRNA and protein levels of ER stress markers GRP78, ATF4 and CHOP were increased in TAC mice, while ranolazine suppressed ER stress induced by pressure overload (Figure 6a,b); (Ni et al., 2011) Similar results were observed in Iso and Bay treated HL-1 cells (Figure 6c-f). Ranolazine reduced ER stress markers GRP78, ATF4 and CHOP induced by Iso and Bay. These data indicated that ranolazine relieves ER stress triggered by cardiac hypertrophy and Ca2+ overload.

Figure 6.

Ranolazine suppresses ER stress induced by pressure overload and Ca2+ overload. (a, b) Both protein level (a) and mRNA level (b) of ER stress markers GRP78, ATF4 and CHOP were increased in TAC mice at 4 weeks, while ranolazine suppressed ER stress induced by pressure overload. (c, d) ER stress markers increased in Iso pretreated HL-1 cells, while ranolazine inhibited ER stress at both protein and mRNA levels. (e, f) ER stress markers increased in LTCC activator Bay K8644 pretreated HL-1 cells, and ranolazine also reduced such ER stress at both protein and mRNA levels. Each western blot analysis was performed for 3–5 biological repeats. Real-time PCR was performed for three biological replicates, and three technical repeats for each replicate. One-way analysis of variance was used for analysis. Data were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (*p < 0.05). ATF4: activating transcription factor 4; CHOP: CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; GRP78: glucose-regulated protein 78; LTCC: L-type calcium channel; mRNA, messenger RNA; PCR: polymerase chain reaction

CHOP is an apoptotic regulator. As shown in Figure 6a,b and Supporting Information Figure S4A, sustained ER stress and CHOP increase cell apoptosis in hypertrophic and failing hearts. In vitro apoptotic assay was assessed by Annexin V flow cytometry and inhibition of late sodium current by ranolazine effectively attenuated cell apoptosis under stimulation of Ca2+ (Bay) and Na+ activator (Ver; Supporting Information Figure S4B and S4C).

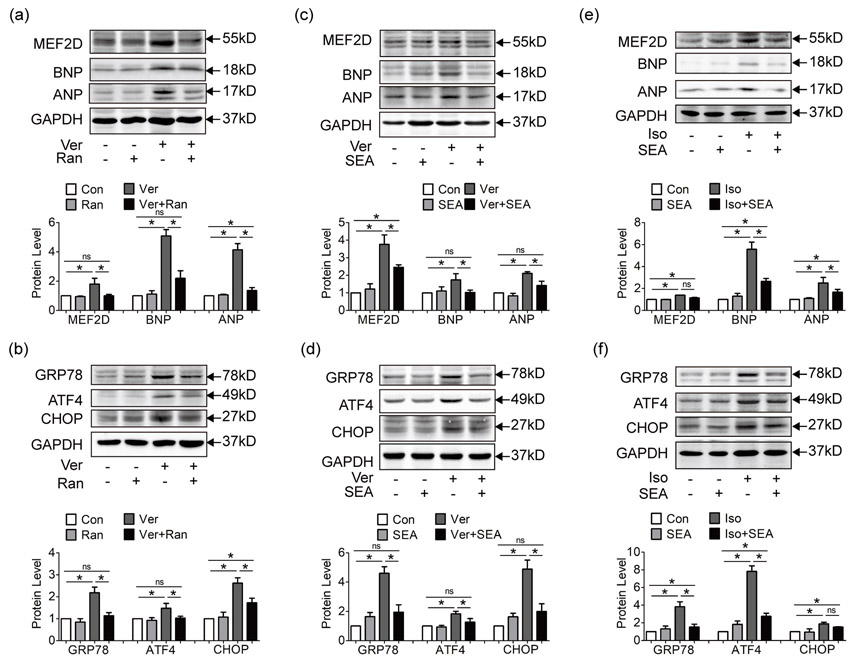

Inhibition of NCX reduces Ca2+ dependent hypertrophic pathways and ER stress

The sodium/calcium exchanger NCX is a key mediator of Na+ and Ca2+ crosstalk. The physiological working mode of NCX is to carry Ca2+ out in exchange for Na+ inward (Glynn et al., 2015). While in pathological situations like pressure overload, sustained INa,L leads to elevated intracellular Na+, which triggers the outward transfer mode of NCX to export Na+ out and brings in more Ca2+ (Armoundas et al., 2003; Maltsev et al., 2007; Onal et al., 2017; Toischer et al., 2013). This also explains how the sodium channel agonist veratridine leads to increased CaT in Figure 3c. Since Na+ activator leads to Ca2+ overload, we examined the state of Ca2+ dependent hypertrophic pathway and ER stress in HL-1 cell line pretreated with veratridine.

As shown in Figure 7a,b, hypertrophic markers MEF2D, ANP and BNP and ER stress markers GRP78, ATF4 and CHOP were up-regulated by sodium channel agonist veratridine, and reduced by inhibition of INa,L with ranolazine. Also, inhibition of NCX activity with SEA0400 alleviated the hypertrophic pathway and ER stress triggered by veratridine (Figure 7c,d), highlighting the role of NCX in Na+ induced Ca2+ overload. And flow cytometry suggested that inhibition of NCX effectively reduced veratridine induced cell apoptosis (Supporting Information Figure S3C). We further explored the role of SEA0400 in Iso pretreated HL-1 cells. As shown in Figure 7e,f, SEA0400 protected HL-1 cells from severe hypertrophy and ER stress. And depletion of NCX using NCX siRNA in HL-1 cells copied the observations in experiments with SEA0400 (Supporting Information Figure S5), implying the importance of NCX in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of NCX reduces Ca2+-dependent hypertrophic pathway and ER stress. (a, b) Hypertrophic markers MEF2D, ANP, and BNP (a) and ER stress markers GRP78, ATF4, and CHOP (b) were upregulated in HL-1 pretreated with Na+ activator veratridine, while ranolazine suppressed hypertrophic pathway and ER stress induced by veratridine. (c, d) Hypertrophic markers (c) and ER stress markers (d) were upregulated in HL-1 pretreated with veratridine, while inhibition of NCX activity with SEA suppressed hypertrophic pathway and ER stress induced by veratridine. (e, f) Hypertrophic markers (e) and ER stress markers (f) were upregulated by β-agonist Isoproterenol in HL-1 cells, and inhibition of NCX activity with SEA also attenuated hypertrophy and ER stress. Each western blot analysis was performed for 3–5 biological repeats. Data were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (*p < 0.05). ANP: atrial natriuretic peptide; ATF4: activating transcription factor 4; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide; CHOP: CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; GRP78: glucose-regulated protein 78; MEF2: myocyte enhancer factor 2; NCX: sodium calcium exchanger; SEA: SEA0400

Above observations pointed to the importance of NCX in Na+/Ca2+ crosstalk, and that inhibition of NCX activity alleviated Ca2+ dependent hypertrophy and ER stress in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure.

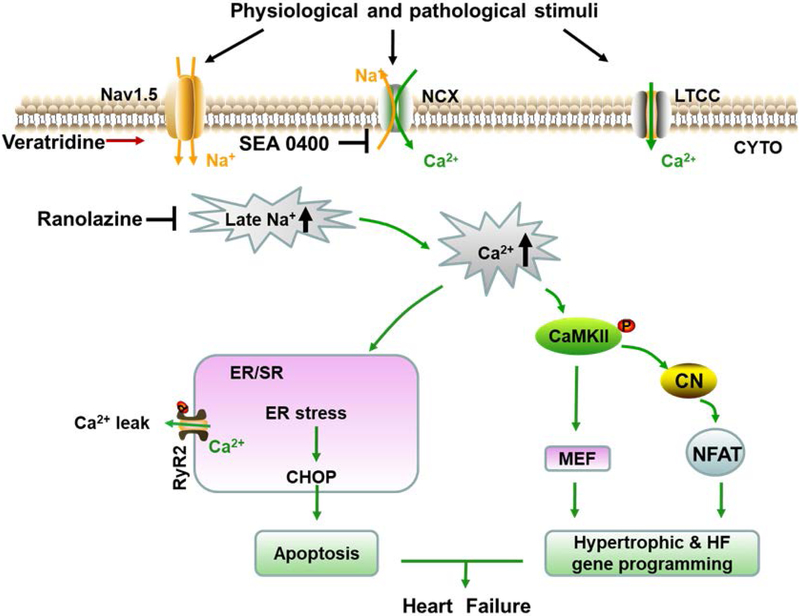

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the therapeutic effect of ranolazine in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure, and the mechanisms underlying were through relieving Na+ dependent Ca2+ overload and inhibiting ER stress and hypertrophic pathways as summarized in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic showing how ranolazine attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Under physiological situation, INa,L constitutes a small inward sodium current, and NCX works in the forward mode to bring Na+ in and export Ca2+ out of the cell membrane. While under stimuli such as pressure overload, sustained INa,L makes up a considerable amount of Na+ current, and results in an elevated concentration of intracellular Na+, favoring the reverse mode of NCX to expel extra Na+ and bring in more Ca2+. Excessive Ca2+ triggers its target pathways and stress response. Under Ca2+ overload, Ca2+ leak from ER also increased, partly owing to the highly phosphorylated RyR2 by CaMKII, aggravating intracellular Ca2+ overload. In addition, imbalance of cytoplasmic and ER luminal Ca2+ handling disturb the protein folding environment and unfolded protein aggregates lead to ER stress. Prolonged ER stress up-regulates the apoptotic effector CHOP to induce cell apoptosis and heart failure. Activated CaMKII releases the transcriptional activity of transcription factor MEF2D and promote nuclear translocalization of NFATc3, allowing for hypertrophic and heart failure gene programming. Together, ranolazine exerts protection by inhibition of INa,L and normalizing Ca2+ handling, thus alleviating the downstream deterioration of cardiac structural and functional remodeling.

Referring to the modeling characteristic of TAC surgery (Takimoto et al., 2005), 4 weeks after surgery was chosen as the time point of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), and 9 weeks after surgery as the time point of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Consistently, contractile function parameters such as EF, FS and LVID;d were normal at 4 weeks and impaired at 9W. As heart failure results from continuous remodeling rather than a sudden transformation. Genetic and microscopic alteration precedes the onset of impaired contractile function. Correspondingly, fibrotic deposition, cellular hypertrophy, Ca2+ dysregulation and gene changes were detected at 4 weeks, before the reduction of EF. One interesting finding in this study was that, while EF and FS by echocardiography were not altered, invasive pressure measurements show decline in function at 4 weeks in TAC mice. We attributed this discrepancy to impaired cardiac reserve of HFpEF (Henein et al., 2013). While cardiac function was compensated at resting state by echocardiography, the operation of invasive pressure measurements introduced a stress stimulus to the mouse cardiovascular system, exposing the impaired cardiac reserve at 4 weeks.

Heart failure is the end stage of many cardiac diseases, and complex abnormalities are involved in the structural and functional remodeling. Ion dysregulation is a key aspect of cardiac remodeling. Studies have revealed aberrant dynamics of intracellular Na+, K+ and Ca2+, accompanied by altered ion channel expression in heart failure. Late sodium current (INa,L) composes a lasting inward sodium current generated by delayed sodium channel inactivation. Increased INa,L brings in more Na+ into the cell and leads to intracellular Na+ accumulation. Aberrant INa,L is directly linked with increased susceptibility to arrhythmia and dysfunction in cardiac disease (Toischer et al., 2013). Recent studies demonstrated that sustained INa,L was also causative to cardiac structural remodeling (Glynn et al., 2015). Data from patients and animal models all revealed enhanced INa,L in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes (Coppini et al., 2013; Flenner et al., 2016; Toischer et al., 2013). Cellular Na+ and Ca2+ homeostasis are tightly integrated, as cellular Na+ overload stimulates the reverse mode of NCX to facilitate the influx of Ca2+ in exchange for efflux of Na+. The net result is an elevated Ca2+ concentration. Ranolazine, a potent late INa,L inhibitor, may normalize altered intracellular Ca2+ concentration due to the close relationship between Na+ and Ca2+ handling by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Our study shows that ranolazine prevents cardiac hypertrophy and reduces myocardial fibrosis in a model of TAC induced pressure overload by relieving Na+ dependent Ca2+ overload.

SR Ca2+ leak is generated by increased opening probability (Po) of RyR2. Parikh et al has proved that ranolazine reduced Po of RyR2 by stabilizing RyR2, though the mechanism remains unclear still (Parikh et al., 2012). Studies have shown that RyR2 is a phosphorylated substrate for kinase CaMKII, and hyper-phosphorylation of RyR2 at Ser2809 by CaMKII leads to increased Po and SR leak, while activity of CaMKII is regulated by Ca2+ level (Fischer et al., 2013; Maier and Bers, 2007; Onal et al., 2017; Wehrens et al., 2004). In this study, we found that cardiac myocytes from TAC mice displayed decreased Ca2+ transient amplitudes due to reduced SR Ca2+ stores at the late stage of heart failure (9 weeks), while ranolazine treatment restored the altered SR Ca2+ stores induced by pressure overload. Based on above facts and findings in our study, we speculate that ranolazine reduces SR leak by inhibiting Na+ induced Ca2+ overload, down-regulating the RyR2 phosphorylation by CaMKII and reducing the Po of RyR2. This speculation was supported by the findings in control cardiomyocytes that veratridine induced Na+ and Ca2+ overload with increased SR leak and impaired SR Ca2+ stores, while ranolazine treatment normalized the aberrant Na+ and Ca2+ handling.

Though triggered by different initial pathologic causes, cardiac hypertrophy shares some common features resulting from a genetic reprogramming of several proteins, and Ca2+ has been proved as a key signaling regulator in the initiation of such genetic reprogramming (Gomez et al., 2013). As in this study, CaMKII activation is a response to elevated Ca2+ concentrations. Under intracellular Ca2+ overload, phosphorylated CaMKII increases MEF2D transcriptional activity by phosphorylating HDAC and releasing MEF2 from HDAC repression (Zhang et al., 2007). In addition, phosphorylated CaMKII activates calcineurin and promotes NFATc3 translocalize into nuclei. Both MEF2D and NFATc3 are transcription factors targeting at hypertrophic and heart failure gene programming. In this study, we detected increased activity of CaMKII in TAC mice, as denoted by the phosphorylation ratio of CaMKII, which is consistent with the aberrant Ca2 cycling in TAC mice cardiomyocytes. And Ca2+/CaM/CaMKII/MEF2 and calcineurin/NFAT pathways were activated, together with overexpression of the hypertrophic and heart failure markers ANP and BNP. While in mice treated with ranolazine, this cascade was well inhibited. These observations were reproduced in HL-1 cell line exposed to beta-agonist isoproterenol and LTCC activator Bay K8644. Together, these data suggest that ranolazine alleviated the Ca2+/CaM/CaMKII/MEF2 and calcineurin/NFAT pathways by normalizing Ca2+ handling in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure.

The ER is the cell’s protein folding workshop. Under stress stimuli such as Ca2+ and ER Ca2+ depletion, protein folding would be suspended to reduce oxygen consumption and save energy, which results in the accumulation and aggregation of unfolded proteins-a condition referred to as ER stress (Yaoita et al., 2002). As in this study, ER chaperone GRP78 was overexpressed to deal with unfolded protein under pressure overload. Unfolded protein aggregates recruit GRP78 from ER membrane and dissociate with PERK, activating the transcription factor ATF4. ATF4 not only induces up-regulation of molecular chaperones and folding enzymes, but also induces the expression of pro-apoptotic transcription factor CHOP (Groenendyk et al., 2013). Pressure overload by transverse aortic constriction induces expression of ER chaperones and ER stress-induced apoptosis of cardiac myocytes, leading to cardiac hypertrophy and HF (Okada et al., 2004). In this study, induction of ER stress and cell apoptosis were observed in TAC mice and ameliorated by ranolazine.

In vitro study using HL-1 cell line showed that ER stress and apoptosis were induced by both Ca2+ activator Bay K8644 and Na+ activator veratridine, which opens voltage-dependent Na+ channels and increases [Na+]i, while pretreatment of ranolazine markedly reduced ER stress signaling. Furthermore, interrupting the Na+ induced Ca2+ influx by pharmocological or genetical inhibition of NCX activity attenuated ER stress and apoptosis in veratridine treated cells, suggesting a joint role of NCX between Na+ and Ca2+ crosstalk.

The effect of ranolazine in chronic heart failure has been investigated by many groups worldwide. And the conclusions were generally promising, revealing increased INa,L in hearts of both animal models and failing human hearts, and administration of ranolazine improved cardiac function (De Angelis et al., 2016; Flenner et al., 2016; Murray and Colombo, 2014; Sossalla and Maier, 2012; Williams et al., 2014). Studies in dogs with chronic heart failure revealed therapeutic effect of ranolazine on left ventricular function (Rastogi et al., 2008; Undrovinas et al., 2006). For clinical trials, a study of Murray’s group confirmed ranolazine preserved and improved left ventricular ejection fraction and autonomic measures when added to guideline-driven therapy in 54 matched patients of chronic heart failure, with a mean follow-up period of 23.7 months. And the subgroup of MERLIN-TIMI 36 (Metabolic Efficiency With Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 36) trial with 4,543 patients revealed that patients with elevated levels of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP> 80 pg/ml) were at higher risk of composite cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and recurrent ischemia at 1 year; and in these high risk patients, ranolazine reduced the primary end point (Morrow et al., 2010).

While the current studies of ranolazine on heart failure came to the similar conclusions with our observations on pressure overload-induced heart failure, the effect of ranolazine on cardiac hypertrophy remained controversial. Among many others, Coppini Raffaele’s team has done a lot of work to explore the effect of ranolazine on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Their research on the troponin-T mutation mouse model of HCM, cardiomyocytes and trabeculae from HCM patients (Coppini et al., 2013; Coppini et al., 2017; Olivotto et al., 2018) all showed enhanced INa,L and Ca2+ overload, and ranolazine improved HCM phenotype and protected cardiac function. However, Flenner et al suggested ranolazine lacks long-term therapeutic effects in vivo in an Mybpc3-targeted knock-in mouse model of HCM (Flenner et al., 2016). Meanwhile, the Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled clinical trial RESTYLE-HCM, including 80 non-obstructive HCM patients aged 53±14 years, revealed that ranolazine showed no overall effect on exercise performance, plasma prohormone brain natriuretic peptide levels, diastolic function, or quality of life after 5 months follow-up (Olivotto et al., 2018). What’s worse, the LIBERTY-HCM Trial (NCT02291237), including 172 HCM patients aged 47±11.1 years to explore the effect of another INa,L inhibitor eleclazine on HCM, was terminated prior to the end of the double-blind phase, because the totality of the current data did not support continuation. These discrepancies were not easy to interpret. A couple of possibilities might be put forward. (i) Onset of treatment. According to the current animal experiments (De Angelis et al., 2016; Liles et al., 2015; Rocchetti et al., 2014; Toischer et al., 2013), ranolazine was effective on cardiac hypertrophy on those acquired models, which were treated shortly after hypertrophic modeling. However, on those genetic models, hypertrophic cardiac remodeling starts since the embryonic period. Ranolazine might not be strong enough to reverse the already severe hypertrophy. A clinical trial of Carolyn Ho et al to explore the treatment for HCM also emphasized the importance of early onset of treatment (Ho et al., 2015). As human HCM was mainly caused by genetic mutations, this might be the major reason for the failure in HCM clinical trials. Subclinical juvenile might be the appropriate population for administration, as has performed by Carolyn Ho et al (Ho et al., 2015). (ii) Drug administration duration. Accoring to published data, though ranolazine lacked therapeutic effects in the Mybpc3 knock-in mouse as Flenner et al reported, improvement in hypertrophic biomarkers and echocardiographic dimensions were observed (Flenner et al., 2016). Longer duration might be essential for ranolazine to exert protection effect.

However, we still have limitations. Ranolazine is generally investigated as selective INa,L inhibitor, since it exhibits higher inhibition selection than other ion currents within a certain range of concentration (Scirica et al., 2007). But its pleiotropic effect should not be ignored. Besides INa,L inhibition, ranolazine also exhibits β receptor blockade, L-type Ca channel blockade as well as a block of transient outward K current. In the future, we will focus on more selective INa,L inhibitor effect on cardiac hypertrophy and HF.

In summary, our study demonstrates that inhibition of INa,L with ranolazine improves pressure overload induced cardiac hypertrophy and systolic and diastolic dysfunction by normalizing Na+ and Ca2+ handling, inhibiting the downstream hypertrophic pathways and ER stress. Our study provides evidence for the new clinical application of INa,L inhibition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 81470519, 91439203, 81630010, 31771264, 31400998] and supported by National Institutes of Health grants [R01-HL089598, R01-HL091947, R01-HL117641] to X.H.T.W., and American Heart Association grant [13EIA14560061] to X.H.T.W..

Murine cardiac cell line HL-1 was a kind gift from professor Claycomb. Supports from colleagues of Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology and Hubei Key Laboratory of Genetics and Molecular Mechanisms of Cardiological Disorders were acknowledged in this study.

NONSTANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- ANP

Atrial natriuretic peptide

- ATF4

Activating transcription factor 4

- BNP

Brain natriuretic peptide

- CaM

Calmodulin

- CaMKII

Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- CHOP

CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein

- CNα

Calcineurin α subunit

- EF

Ejection fraction

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- GRP78

Glucose regulated protein 78

- HDAC

Histone deacetylase

- HF

Heart failure

- INa,L

Late sodium current

- LTCC

L-type calcium channel

- MEF2D

Myocyte enhancer factor 2D

- NCX

Sodium calcium exchanger

- NFAT

Nuclear factor of activated T cells

- RyR2

Type II ryanodine receptor

- TAC

Transverse aortic constriction

- TUNEL

TdT-mediated dUTP Nick-End Labeling

- UPR

Unfolded protein response

- WGA

Wheat germ agglutinin

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Xander H.T. Wehrens is a founding partner of Elex Biotech, a start-up company that developed drug molecules that target ryanodine receptors for the treatment of cardiac arrhythmia disorders. Other authors have no conflicts.

References

- Armoundas AA, Hobai IA, Tomaselli GF, Winslow RL, and O’Rourke B. 2003. Role of sodium-calcium exchanger in modulating the action potential of ventricular myocytes from normal and failing hearts. Circulation research. 93:46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill DM, and Wasserstrom JA. 1986. Intracellular sodium and the positive inotropic effect of veratridine and cardiac glycoside in sheep Purkinje fibers. Circulation research. 58:109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaitman BR 2004. Efficacy and safety of a metabolic modulator drug in chronic stable angina: review of evidence from clinical trials. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology and therapeutics. 9 Suppl 1:S47–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelu MG, Sarma S, Sood S, Wang S, van Oort RJ, Skapura DG, Li N, Santonastasi M, Muller FU, Schmitz W, Schotten U, Anderson ME, Valderrabano M, Dobrev D, and Wehrens XH. 2009. Calmodulin kinase II-mediated sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak promotes atrial fibrillation in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 119:1940–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani OH, Yang XP, Cavasin MA, and Carretero OA. 2003. Increased systolic performance with diastolic dysfunction in adult spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 41:249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppini R, Ferrantini C, Yao L, Fan P, Del Lungo M, Stillitano F, Sartiani L, Tosi B, Suffredini S, Tesi C, Yacoub M, Olivotto I, Belardinelli L, Poggesi C, Cerbai E, and Mugelli A. 2013. Late sodium current inhibition reverses electromechanical dysfunction in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 127:575–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppini R, Mazzoni L, Ferrantini C, Gentile F, Pioner JM, Laurino A, Santini L, Bargelli V, Rotellini M, Bartolucci G, Crocini C, Sacconi L, Tesi C, Belardinelli L, Tardiff J, Mugelli A, Olivotto I, Cerbai E, and Poggesi C. 2017. Ranolazine Prevents Phenotype Development in a Mouse Model of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. Heart failure. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida PW, de Freitas Lima R, de Morais Gomes ER, Rocha-Resende C, Roman-Campos D, Gondim AN, Gavioli M, Lara A, Parreira A, de Azevedo Nunes SL, Alves MN, Santos SL, Alenina N, Bader M, Resende RR, dos Santos Cruz J, Souza dos Santos RA, and Guatimosim S. 2013. Functional cross-talk between aldosterone and angiotensin-(1-7) in ventricular myocytes. Hypertension. 61:425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis A, Cappetta D, Piegari E, Rinaldi B, Ciuffreda LP, Esposito G, Ferraiolo FA, Rivellino A, Russo R, Donniacuo M, Rossi F, Urbanek K, and Berrino L. 2016. Long-term administration of ranolazine attenuates diastolic dysfunction and adverse myocardial remodeling in a model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. International journal of cardiology. 217:69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deAlmeida AC, van Oort RJ, and Wehrens XH. 2010. Transverse aortic constriction in mice. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE 21(38). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueredo VM, Pressman GS, Romero-Corral A, Murdock E, Holderbach P, and Morris DL. 2011. Improvement in left ventricular systolic and diastolic performance during ranolazine treatment in patients with stable angina. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology and therapeutics. 16:168–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer TH, Herting J, Mason FE, Hartmann N, Watanabe S, Nikolaev VO, Sprenger JU, Fan P, Yao L, Popov AF, Danner BC, Schondube F, Belardinelli L, Hasenfuss G, Maier LS, and Sossalla S. 2015. Late INa increases diastolic SR-Ca2+-leak in atrial myocardium by activating PKA and CaMKII. Cardiovascular research. 107:184–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer TH, Herting J, Tirilomis T, Renner A, Neef S, Toischer K, Ellenberger D, Forster A, Schmitto JD, Gummert J, Schondube FA, Hasenfuss G, Maier LS, and Sossalla S. 2013. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and protein kinase A differentially regulate sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in human cardiac pathology. Circulation. 128:970–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flenner F, Friedrich FW, Ungeheuer N, Christ T, Geertz B, Reischmann S, Wagner S, Stathopoulou K, Sohren KD, Weinberger F, Schwedhelm E, Cuello F, Maier LS, Eschenhagen T, and Carrier L. 2016. Ranolazine antagonizes catecholamine-induced dysfunction in isolated cardiomyocytes, but lacks long-term therapeutic effects in vivo in a mouse model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovascular research. 109:90–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaborit N, Steenman M, Lamirault G, Le Meur N, Le Bouter S, Lande G, Leger J, Charpentier F, Christ T, Dobrev D, Escande D, Nattel S, and Demolombe S. 2005. Human atrial ion channel and transporter subunit gene-expression remodeling associated with valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 112:471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn P, Musa H, Wu X, Unudurthi SD, Little S, Qian L, Wright PJ, Radwanski PB, Gyorke S, Mohler PJ, and Hund TJ. 2015. Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Phosphorylation at Ser571 Regulates Late Current, Arrhythmia, and Cardiac Function In Vivo. Circulation. 132:567–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez AM, Ruiz-Hurtado G, Benitah JP, and Dominguez-Rodriguez A. 2013. Ca(2+) fluxes involvement in gene expression during cardiac hypertrophy. Current vascular pharmacology. 11:497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenendyk J, Agellon LB, and Michalak M. 2013. Coping with endoplasmic reticulum stress in the cardiovascular system. Annual review of physiology. 75:49–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, and Su TP. 2007. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+) signaling and cell survival. Cell. 131:596–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henein M, Morner S, Lindmark K, and Lindqvist P. 2013. Impaired left ventricular systolic function reserve limits cardiac output and exercise capacity in HFpEF patients due to systemic hypertension. International journal of cardiology. 168:1088–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CY, Lakdawala NK, Cirino AL, Lipshultz SE, Sparks E, Abbasi SA, Kwong RY, Antman EM, Semsarian C, Gonzalez A, Lopez B, Diez J, Orav EJ, Colan SD, and Seidman CE. 2015. Diltiazem treatment for pre-clinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy sarcomere mutation carriers: a pilot randomized trial to modify disease expression. JACC. Heart failure. 3:180–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye DM, and Krum H. 2007. Drug discovery for heart failure: a new era or the end of the pipeline? Nature reviews. Drug discovery. 6:127–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent RL, Hoober JK, and Cooper G.t.. 1989. Load responsiveness of protein synthesis in adult mammalian myocardium: role of cardiac deformation linked to sodium influx. Circulation research. 64:74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liles JT, Hoyer K, Oliver J, Chi L, Dhalla AK, and Belardinelli L. 2015. Ranolazine reduces remodeling of the right ventricle and provoked arrhythmias in rats with pulmonary hypertension. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 353:480–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Q, Janardhan A, and Efimov IR. 2012. Remodeling of calcium handling in human heart failure. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 740:1145–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier LS, and Bers DM. 2007. Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) in excitation-contraction coupling in the heart. Cardiovascular research. 73:631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltsev VA, Silverman N, Sabbah HN, and Undrovinas AI. 2007. Chronic heart failure slows late sodium current in human and canine ventricular myocytes: implications for repolarization variability. European journal of heart failure. 9:219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mognol GP, Carneiro FR, Robbs BK, Faget DV, and Viola JP. 2016. Cell cycle and apoptosis regulation by NFAT transcription factors: new roles for an old player. Cell death & disease. 7:e2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow DA, Scirica BM, Sabatine MS, de Lemos JA, Murphy SA, Jarolim P, Theroux P, Bode C, and Braunwald E. 2010. B-type natriuretic peptide and the effect of ranolazine in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: observations from the MERLIN-TIMI 36 (Metabolic Efficiency With Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 36) trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 55:1189–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray GL, and Colombo J. 2014. Ranolazine preserves and improves left ventricular ejection fraction and autonomic measures when added to guideline-driven therapy in chronic heart failure. Heart international. 9:66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni L, Zhou C, Duan Q, Lv J, Fu X, Xia Y, and Wang DW. 2011. beta-AR blockers suppresses ER stress in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. PloS one. 6:e27294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K, Minamino T, Tsukamoto Y, Liao Y, Tsukamoto O, Takashima S, Hirata A, Fujita M, Nagamachi Y, Nakatani T, Yutani C, Ozawa K, Ogawa S, Tomoike H, Hori M, and Kitakaze M. 2004. Prolonged endoplasmic reticulum stress in hypertrophic and failing heart after aortic constriction: possible contribution of endoplasmic reticulum stress to cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Circulation. 110:705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivotto I, Camici PG, Merlini PA, Rapezzi C, Patten M, Climent V, Sinagra G, Tomberli B, Marin F, Ehlermann P, Maier LS, Fornaro A, Jacobshagen C, Ganau A, Moretti L, Hernandez Madrid A, Coppini R, Reggiardo G, Poggesi C, Fattirolli F, Belardinelli L, Gensini G, and Mugelli A. 2018. Efficacy of Ranolazine in Patients With Symptomatic Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: The RESTYLE-HCM Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Circulation. Heart failure. 11:e004124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onal B, Gratz D, and Hund TJ. 2017. Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II-dependent regulation of atrial myocyte late Na+ current, Ca2+ cycling and excitability: a mathematical modeling study. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology:ajpheart 00185 02017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh A, Mantravadi R, Kozhevnikov D, Roche MA, Ye Y, Owen LJ, Puglisi JL, Abramson JJ, and Salama G. 2012. Ranolazine stabilizes cardiac ryanodine receptors: a novel mechanism for the suppression of early afterdepolarization and torsades de pointes in long QT type 2. Heart rhythm. 9:953–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popescu I, Galice S, Mohler PJ, and Despa S. 2016. Elevated local [Ca2+] and CaMKII promote spontaneous Ca2+ release in ankyrin-B-deficient hearts. Cardiovascular research. 111:287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu W, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Wang X, Zhao D, … Zhang C, (2012). MFEprimer-2.0: A fast thermodynamics-based program for checking PCR primer specificity. Nucleic acids research. 40, W205–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi S, Sharov VG, Mishra S, Gupta RC, Blackburn B, Belardinelli L, Stanley WC, and Sabbah HN. 2008. Ranolazine combined with enalapril or metoprolol prevents progressive LV dysfunction and remodeling in dogs with moderate heart failure. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 295:H2149–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchetti M, Sala L, Rizzetto R, Staszewsky LI, Alemanni M, Zambelli V, Russo I, Barile L, Cornaghi L, Altomare C, Ronchi C, Mostacciuolo G, Lucchetti J, Gobbi M, Latini R, and Zaza A. 2014. Ranolazine prevents INaL enhancement and blunts myocardial remodelling in a model of pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovascular research. 104:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scirica BM, Morrow DA, Hod H, Murphy SA, Belardinelli L, Hedgepeth CM, Molhoek P, Verheugt FW, Gersh BJ, McCabe CH, and Braunwald E. 2007. Effect of ranolazine, an antianginal agent with novel electrophysiological properties, on the incidence of arrhythmias in patients with non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: results from the Metabolic Efficiency With Ranolazine for Less Ischemia in Non ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 36 (MERLIN-TIMI 36) randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 116:1647–1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sossalla S, and Maier LS. 2012. Role of ranolazine in angina, heart failure, arrhythmias, and diabetes. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 133:311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Onge M, Dube PA, Gosselin S, Guimont C, Godwin J, Archambault PM, Chauny JM, Frenette AJ, Darveau M, Le Sage N, Poitras J, Provencher J, Juurlink DN, and Blais R. 2014. Treatment for calcium channel blocker poisoning: a systematic review. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 52:926–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto E, Champion HC, Li M, Belardi D, Ren S, Rodriguez ER, Bedja D, Gabrielson KL, Wang Y, and Kass DA. 2005. Chronic inhibition of cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase 5A prevents and reverses cardiac hypertrophy. Nature medicine. 11:214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toischer K, Hartmann N, Wagner S, Fischer TH, Herting J, Danner BC, Sag CM, Hund TJ, Mohler PJ, Belardinelli L, Hasenfuss G, Maier LS, and Sossalla S. 2013. Role of late sodium current as a potential arrhythmogenic mechanism in the progression of pressure-induced heart disease. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 61:111–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undrovinas AI, Belardinelli L, Undrovinas NA, and Sabbah HN. 2006. Ranolazine improves abnormal repolarization and contraction in left ventricular myocytes of dogs with heart failure by inhibiting late sodium current. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 17 Suppl 1:S169–S177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Dybkova N, Rasenack EC, Jacobshagen C, Fabritz L, Kirchhof P, Maier SK, Zhang T, Hasenfuss G, Brown JH, Bers DM, and Maier LS. 2006. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates cardiac Na+ channels. The Journal of clinical investigation. 116:3127–3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrens XH, Lehnart SE, Reiken SR, and Marks AR. 2004. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation regulates the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circulation research. 94:e61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrens XH, and Marks AR. 2004. Novel therapeutic approaches for heart failure by normalizing calcium cycling. Nature reviews. Drug discovery. 3:565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins BJ, and Molkentin JD. 2004. Calcium-calcineurin signaling in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 322:1178–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S, Pourrier M, McAfee D, Lin S, and Fedida D. 2014. Ranolazine improves diastolic function in spontaneously hypertensive rats. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 306:H867–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaoita H, Sakabe A, Maehara K, and Maruyama Y. 2002. Different effects of carvedilol, metoprolol, and propranolol on left ventricular remodeling after coronary stenosis or after permanent coronary occlusion in rats. Circulation. 105:975–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Kohlhaas M, Backs J, Mishra S, Phillips W, Dybkova N, Chang S, Ling H, Bers DM, Maier LS, Olson EN, and Brown JH. 2007. CaMKIIdelta isoforms differentially affect calcium handling but similarly regulate HDAC/MEF2 transcriptional responses. The Journal of biological chemistry. 282:35078–35087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.