Key Points

Question

Can a risk score predict the probability of nontraumatic fracture within 1 year after ischemic stroke?

Findings

This prognostic study found that among a cohort of 20 435 patients with ischemic stroke, 3.6% had a nontraumatic fracture within 1 year after stroke. Using a combination of 7 characteristics, including global stroke disability, the Fracture Risk After Ischemic Stroke score predicted fracture risk with good discrimination (C statistic, 0.70 in the validation cohort).

Meaning

The risk predictions in the Fracture Risk After Ischemic Stroke score can be used to select patients for bone densitometry screening or, for very high-risk patients, for consideration for empirical bisphosphonate therapy.

This prognostic study evaluated medical records of survivors of ischemic stroke from a national Canadian database to develop and validate a scoring system to predict low-trauma fractures within 1 year of hospital discharge.

Abstract

Importance

The risk for low-trauma fracture is increased by more than 30% after ischemic stroke, but existing fracture risk scores do not account for history of stroke as a high-risk condition.

Objective

To derive a risk score to predict the probability of fracture within 1 year after ischemic stroke and validate it in a separate cohort.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prognostic study of a cohort from the Ontario Stroke Registry, a population-based sample of adults in Ontario, Canada, who were hospitalized with ischemic stroke from July 1, 2003, to March 31, 2012, with 1 year of follow-up. A population-based validation cohort consisted of a sample of 13 698 consecutive stroke admissions captured across 5 years: April 2002 to March 2003, April 2004 to March 2005, April 2008 to March 2009, April 2010 to March 2011, and April 2012 to March 2013.

Exposures

Predictor variables were selected based on biological plausibility and association with fracture risk. Age, sex, and modified Rankin score were abstracted from the medical records part of the Ontario Stroke Audit, and other characteristics were abstracted from administrative health data.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Incidence of low-trauma fracture within 1 year of discharge, based on administrative health data.

Results

The Fracture Risk after Ischemic Stroke (FRAC-Stroke) Score was derived in 20 435 patients hospitalized for ischemic stroke (mean [SD] age, 71.6 [14.0] years; 9564 [46.8%] women) from the Ontario Stroke Registry discharged from July 1, 2003, to March 31, 2012, using Fine-Gray competing risk regression. Low-trauma fracture occurred within 1 year of discharge in 741 of the 20 435 patients (3.6%) in the derivation cohort. Age, discharge modified Rankin score (mRS), and history of rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, falls, and previous fracture were associated with the cumulative incidence of low trauma fracture in the derivation cohort. Model discrimination in the validation cohort (n = 13 698) was good (C statistic, 0.70). Discharge mRS was an important discriminator of risk (relative integrated discrimination improvement, 8.7%), with highest risk in patients with mRS 3 and 4 but lowest in bedbound patients (mRS 5). From the lowest to the highest FRAC-Stroke quintile, the cumulative incidence of 1-year low-trauma fracture increased from 1.3% to 9.0% in the validation cohort. Predicted and observed rates of fracture were similar in the external validation cohort. Analysis was conducted from July 2016 to January 2019.

Conclusions and Relevance

The FRAC-Stroke score allows the clinician to identify ischemic stroke survivors at higher risk of low-trauma fracture within 1 year of hospital discharge. This information might be used to select patients for interventions to prevent fractures.

Introduction

Patients with ischemic stroke are at risk for poststroke comorbidities including pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis, pressure ulcerations, and urinary tract infections.1 They also have higher risk of subsequent low trauma fractures, for example from ground level falls.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 A previous study showed that low-trauma fracture risk was increased by more than 30% in survivors of stroke compared with matched controls from the general population.10 Independent risk factors for fracture were identified in that study, but the adequacy of fracture prediction and the most predictive risk factors were not determined.10

For the primary prevention of fracture, guidelines recommend screening for osteoporosis with bone densitometry based on risk. To guide screening, prediction rules have been derived and validated for low-trauma fracture. The best validated and most commonly used score is the World Health Organization Fracture Risk (FRAX) score.11,12 However, the FRAX score was derived in a general community population, does not take into account unique stroke-related predictors, and has not been validated in a population of stroke survivors.

We used data from a large stroke registry to derive a fracture risk for stroke (FRAC-Stroke) score, and then validated it in a separate population-based stroke registry linked to administrative health records.

Methods

This study followed the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) reporting guideline. The Ontario Stroke Registry (formerly known as the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network) collects clinical information on a population-based sample of patients with stroke seen at all 150 acute care institutions in the province.13,14,15 Patients included in this study were admitted to the hospital with ischemic stroke and subsequently discharged alive, excluding hemorrhagic stroke, inpatient stroke, and pediatric patients (18 years or younger). The registry is housed at ICES. Ontario privacy legislation authorizes health information custodians to disclose personal health information to a prescribed entity, like ICES, without consent. The study was approved by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board Institutional Review Board with waiver of consent. The derivation cohort consisted of patients with ischemic stroke discharged alive from any of the 11 regional stroke centers included in the Ontario Stroke Registry from July 1, 2003, to March 31, 2012. The population-based validation cohort consisted of a sample of 13 698 consecutive stroke admissions across 5 years: April 2002 to March 2003, April 2004 to March 2005, April 2008 to March 2009, April 2010 to March 2011, and April 2012 to March 2013, not included in the derivation cohort. For both cohorts, only the first ischemic stroke event was included if the patient had more than one stroke event during the study time frame. Patient records were linked to provincial population-based administrative health records using unique, encoded patient identifiers as previously described.10 Analyses were performed from July 2016 to January 2019. The province of Ontario has universal health care coverage for hospital care, physician services, and diagnostic tests.

Baseline characteristics were abstracted from patient medical records by trained research personnel. These characteristics included age, sex, presence of limb weakness, and history of stroke, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, dementia, and cancer. Duplicate medical record abstraction has shown excellent agreement for key variables including stroke type, severity and comorbid conditions.16 History of falls, rheumatoid arthritis, hyperparathyroidism, and fractures were obtained through administrative data linkages. Stroke severity was recorded using the Canadian Neurological Scale,17 in which lower scores indicate more severe stroke. The scale ranges from 0 to 11.5, with scores of 0 to 4 indicating severe stroke; 5 to 7, moderate stroke; and 8 or greater, mild stroke. The CNS can be converted to an estimated National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) by using the conversion formula NIHSS = 23 – 2 CNS, where CNS is the Canadian Stroke Scale score.18 Discharge modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score was abstracted from the medical record by trained study staff, using notes from physicians, nurses, physical and occupational therapists.

The outcome of the study was the occurrence of a new low-trauma fracture within the year after discharge. Outcomes were captured using linked administrative health data. A low-trauma fracture was defined as any fracture of the femur, forearm, humerus, pelvis or vertebrae, including ground-level falls but excluding fractures resulting from trauma, motor vehicle accidents, falls from a height, or in people with active cancer. The billing codes and databases for variables derived from administrative health data are specified in the eTable in the Supplement.

To determine comparability of the derivation and validation cohort, baseline characteristics were tabulated. Using the derivation cohort, a multivariable Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard regression model was used to identify factors associated with the cumulative incidence of new fracture within one year. The model accounted for death as a competing risk.19 A points-based risk scoring system for estimating the risk of fractures was created based on the β coefficients in the model. Candidate model variables were based on clinical plausibility, including variables related to components of the FRAX score as well as variables related to stroke severity (Canadian Neurological Scale, limb weakness, and mRS).20 Because we were interested also in the degree to which stroke-related disability affected risk, we used integrated discrimination improvement (IDI)21 to measure the added predictive value of including vs not including mRS in the model. The relative IDI was defined as –1 plus the ratio of the difference in the mean estimated probability between events and nonevents under the model with the mRS to the difference in the mean estimated probability between events and nonevents under the model without the mRS.22 The relative IDI quantifies the relative change in the mean predicted probability of an event between those who do and do not experience an event when a new predictor is added to the model.21 Model calibration was assessed in the derivation and validation cohorts by comparing the observed 1-year incidence of fractures to the predicted 1-year incidence of fractures according to deciles of predicted risk from the derivation cohort.23 The cumulative incidence function curves were used to compare the incidence of fracture in the derivation cohort and the validation cohort by the risk score quintiles. The risk score quintile ranges in the validation cohort were as same as the ranges in the derivation cohort. In subgroup analyses, calibration and discrimination were tested separately in men and women and in persons 80 years and older and younger than 80 years, using the derivation cohort to take advantage of its larger sample size. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc). A 2-sided P < .05 was considered significant.

The data set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. Although data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet prespecified criteria for confidential access. The full data set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors on request, understanding that the programs may rely on coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES.

Results

The derivation cohort consisted of 20 435 patients with ischemic stroke and the validation cohort consisted of 13 698 patients with ischemic stroke discharged alive from the hospital. Baseline characteristics of the patients in the derivation and validation samples are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of Derivation and Validation Samples.

| Variable | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Derivation | Validation | |

| Sample size | 20 435 | 13 698 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 71.6 (14.0) | 72.9 (13.3) |

| <40 | 495 (2.4) | 203 (1.5) |

| 40-49 | 1097 (5.4) | 590 (4.3) |

| 50-59 | 2430 (11.9) | 1453 (10.6) |

| 60-69 | 3893 (19.1) | 2653 (19.4) |

| 70-79 | 5660 (27.7) | 3852 (28.1) |

| 80-89 | 5564 (27.2) | 3958 (28.9) |

| ≥90 | 1296 (6.3) | 989 (7.2) |

| Female sex | 9560 (46.8) | 6719 (49.1) |

| Canadian Neurological Stroke Scale scorea | ||

| Mild (≥8) | 14 630 (71.6) | 10 032 (75.3) |

| Moderate (5-7) | 3723 (18.2) | 2258 (16.9) |

| Severe (0-4) | 2082 (10.2) | 1039 (7.8) |

| Weakness | 9003 (44.1) | 10 288 (75.1) |

| Modified Rankin scoreb | ||

| 0 | 1744 (8.5) | 1138 (8.3) |

| 1 | 3784 (18.5) | 2264 (16.5) |

| 2 | 4130 (20.2) | 2701 (19.7) |

| 3 | 4690 (23.0) | 3093 (22.6) |

| 4 | 4811 (23.5) | 3690 (26.9) |

| 5 | 1276 (6.2) | 812 (5.9) |

| Previous stroke | 3714 (18.2) | 2797 (20.4) |

| Hypertension | 13 948 (68.3) | 9660 (70.5) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 7835 (38.3) | 5723 (41.8) |

| Diabetes | 5237 (25.6) | 3867 (28.2) |

| Cancer | 1745 (8.5) | 939 (6.9) |

| Dementia | 2115 (10.3) | 1601 (11.7) |

| Osteoporosis | 2212 (10.8) | 1472 (10.7) |

| History of falls | 4219 (20.6) | 3071 (22.4) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 288 (1.4) | 204 (1.5) |

| Hyperparathyroidism | 81 (0.4) | 65 (0.5) |

| Prior fracture | 1566 (7.7) | 1165 (8.5) |

The Canadian Neurological Stroke Scale measures stroke-related deficits (orientation, language, and motor function); the score ranges from 1.5 to 11.5 with lower scores indicating more severe stroke.

The modified Rankin score measures global disability and ranges from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death).

Multivariable-adjusted predictors of the cumulative incidence of low trauma fracture within 1 year in the derivation cohort are shown in Table 2. The risk of fracture was higher in older patients (80-89 years: adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 2.23; 95% CI, 1.14-4.37; 90-99 years: aHR, 1.90; 95% CI, 0.94-3.87); female sex (aHR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.43-2.00); history of rheumatoid arthritis (aHR, 1.46; 95% CI, 0.94-2.26); osteoporosis (aHR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.17-1.70); previous falls (aHR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.12-1.60); and previous fracture (aHR, 2.67; 95% CI, 2.17-3.28). The risk of fracture varied by discharge disability level, with the highest risk in patients with mRS 3 or 4, and the lowest risk in patients with mRS 5 (bedbound). Including mRS in the model significantly improved prediction, with a relative IDI of 8.7%. Thus, the difference in mean predicted probabilities between patients with and without an event increased by 8.7% when mRS was added to the model.

Table 2. Multivariable Adjusted Predictors of Cumulative Incidence of Fracture at 1 Year After Ischemic Stroke.

| Parameter | β Coefficient | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| <40 | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA |

| 40-49 | −0.04592 | 0.955 (0.432-2.114) | .91 |

| 50-50 | −0.2535 | 0.776 (0.370-1.628) | .50 |

| 60-69 | 0.19367 | 1.214 (0.608-2.422) | .58 |

| 70-79 | 0.49223 | 1.636 (0.834-3.210) | .15 |

| 80-89 | 0.80331 | 2.233 (1.140-4.372) | .02 |

| 90-99 | 0.64422 | 1.904 (0.939-3.865) | .07 |

| Female | 0.5249 | 1.69 (1.429-2.000) | <.001 |

| Modified Rankin scorea | |||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA |

| 1 | 0.03355 | 1.034 (0.731-1.462) | .85 |

| 2 | 0.10762 | 1.114 (0.793-1.564) | .53 |

| 3 | 0.31612 | 1.372 (0.992-1.898) | .06 |

| 4 | 0.30149 | 1.352 (0.976-1.872) | .07 |

| 5 | −0.55915 | 0.572 (0.358-0.913) | .02 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.37586 | 1.456 (0.938-2.261) | .09 |

| Osteoporosis | 0.34454 | 1.411 (1.169-1.704) | <.001 |

| Previous | |||

| Falls | 0.28918 | 1.335 (1.116-1.598) | .002 |

| Fracture | 0.98175 | 2.669 (2.173-3.279) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable.

The modified Rankin score measures global disability, and ranges from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death).

We used the model β coefficients to produce the FRAC-Stroke scoring system, shown in Table 3. In the derivation cohort the FRAC-Stroke scores were distributed as follows: the lowest quintile had scores of 9 or lower, the second quintile had scores of 10 to 12, the third quintile had scores of 13 to 15, the fourth quintile had scores of 16 to 18, and the top quintile had scores of 19 or greater. The association between total point score and the predicted incidence of fracture within 1 year is shown in Table 4.

Table 3. Components of Fracture Risk After Ischemic Stroke (FRAC-Stroke) Score.

| Parameter | Score |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| <40 | 0 |

| 40-49 | 0 |

| 50-59 | −3 |

| 60-69 | 2 |

| 70-79 | 5 |

| 80-89 | 8 |

| 90-99 | 6 |

| Female | 5 |

| Modified Rankin scorea | |

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 |

| 5 | −6 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4 |

| Osteoporosis | 3 |

| Previous | |

| Falls | 3 |

| Fracture | 10 |

The modified Rankin score measures global disability, and ranges from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death).

Table 4. Predicted Cumulative Incidence of Fracture at 1 Year After Ischemic Stroke.

| FRAC Score | Predicted Risk, % |

|---|---|

| −9 | 0.5 |

| −8 | 0.5 |

| −7 | 0.6 |

| −6 | 0.6 |

| −5 | 0.7 |

| −4 | 0.7 |

| −3 | 0.8 |

| −2 | 0.9 |

| −1 | 1.0 |

| 0 | 1.1 |

| 1 | 1.2 |

| 2 | 1.4 |

| 3 | 1.5 |

| 4 | 1.7 |

| 5 | 1.8 |

| 6 | 2.0 |

| 7 | 2.2 |

| 8 | 2.5 |

| 9 | 2.7 |

| 10 | 3.0 |

| 11 | 3.3 |

| 12 | 3.7 |

| 13 | 4.0 |

| 14 | 4.5 |

| 15 | 4.9 |

| 16 | 5.4 |

| 17 | 6.0 |

| 18 | 6.6 |

| 19 | 7.3 |

| 20 | 8.0 |

| 21 | 8.8 |

| 22 | 9.7 |

| 23 | 10.7 |

| 24 | 11.7 |

| 25 | 12.9 |

| 26 | 14.1 |

| 27 | 15.5 |

| 28 | 17.0 |

| 29 | 18.6 |

| 30 | 20.4 |

| 31 | 22.3 |

| 32 | 24.3 |

| 33 | 26.5 |

| 34 | 28.9 |

| 35 | 31.4 |

| 36 | 34.1 |

Abbreviation: FRAC, Fracture Risk After Ischemic Stroke (FRAC-Stroke) Score.

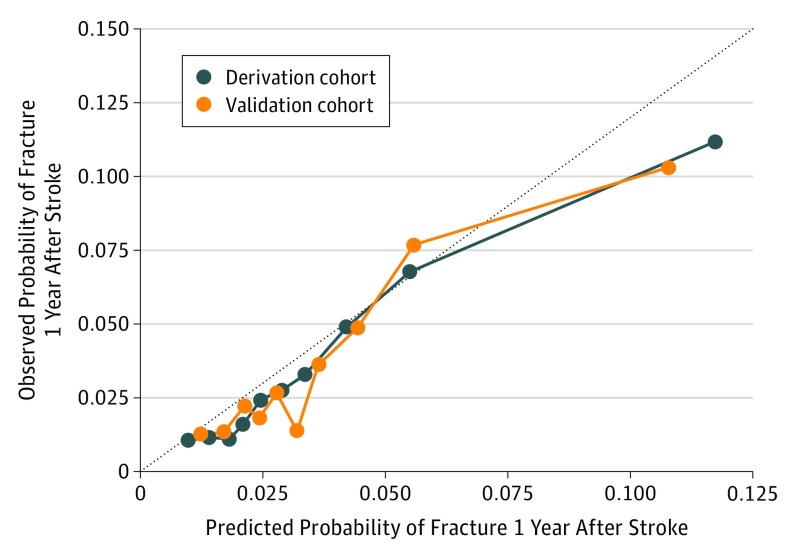

The C statistic for the FRAC-Stroke score was 0.72 in the derivation cohort and 0.70 in the validation cohort. Model calibration in the derivation cohort was good across 9 of 10 risk strata (Figure). The eFigure in the Supplement shows cumulative incidence curves according to quintile of risk scores in the derivation cohort. The observed risk in the derivation and validation cohorts ranged from 1.1% and 1.3% in the lowest quintile to 9.0% and 9.0% in the highest quintile, respectively.

Figure. Observed vs Predicted Fracture Risk According to Deciles of Predicted Risk in the Derivation Cohort.

Predicted probabilities are based on the association of the numerical risk score (Table 3) with predicted probability (Table 4) and are shown for the derivation cohort (blue line) and validation cohort (orange line). Dotted line connects the estimates for each stratum.

The C statistic in women was 0.68 (95% CI, 0.66-0.71) and in men was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.66-0.73); model calibration was good for both groups (data not shown). The C statistic in persons younger than 80 years was 0.71 (95% CI, 0.69-0.74) and in persons 80 years or older was 0.66 (95% CI, 0.63-0.69); model calibration was good for both groups (data not shown).

Discussion

We used data from a large, population-based stroke registry and population-based stroke audit to derive and validate a risk score for the cumulative incidence of fracture at 1 year after stroke, the FRAC-Stroke score (https://www.ucalgary.ca/esmithresearch/publications/frac-stroke). The risk score had moderately good discrimination, with a C statistic of 0.70, a value that is typically considered sufficient to make clinically useful individual predictions.24 In addition, it showed excellent calibration in the validation cohort. The FRAC-Stroke score discriminated average 1-year fracture risk from 1.3% in the lowest quintile to 9.0% in the highest quintile. The FRAC-Stroke score worked similarly well in men and women, but showed reduced discrimination in persons older than 80 years.

The FRAC-Stroke score shares many variables with the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) score, developed by the World Health Organization for prediction of fracture risk in the general community and validated in multiple settings. Age, sex, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoporosis are also variables in the FRAX score. Our work shows that the same variables also independently predict risk in stroke patients, as expected. However, we did not have access to data to completely recreate the FRAX score in our data, so could not directly compare FRAC-Stroke with FRAX.

In addition, we found that global disability from stroke, as measured by the mRS, was an important predictor of fracture risk. The integrated discrimination improvement for mRS was 8.7%, indicating the inclusion of mRS results in a moderate improvement in prediction. This demonstrates that predicting fracture risk in stroke patients differs from predicting risk in the general community, and should take stroke-related disability into account. Fracture risk was greatest in patients with stroke who were ambulating independently but with moderate disability, with or without a walking aid (mRS 3), or those unable to ambulate independently without assistance from other persons (mRS 4), and was lowest in patients with stroke who were bedbound (mRS 5). This suggests that fracture risk may have been related to ground-level falls secondary to motor, sensory, balance, or cognitive consequences of moderate stroke. In addition, patients with a greater degree of weakness after stroke exhibit greater levels of poststroke bone loss, which is more severe in the affected limbs,25,26 and this may also contribute to the elevated risk of fracture in patients with moderate disability. However, we did not have detailed information on stroke location and resulting symptoms, although these are probably important determinants of risk of falls.

A fracture risk score in ischemic stroke survivors has been derived using data from the Insulin Resistance Intervention After Stroke (IRIS) randomized trial.27 However, for several reasons, this risk score may be less applicable than FRAC-Stroke for estimating fracture risk at discharge after ischemic stroke. It was derived in a highly selected clinical trial population overrepresented with men (65%), younger patients (mean age, 63 years), and mild stroke severity (74% with mRS of 0 or 1). It included patients up to 180 days after stroke and patients with TIA. Half of the patients were randomized to pioglitazone therapy, which was shown in IRIS to be associated with a greater risk of fractures. Finally, the score was derived in a smaller cohort (3876) than FRAC-Stroke and was not externally validated in an independent cohort. Despite these limitations in generalizability, several findings were concordant with ours, including that stroke patients had relatively high risk of fracture (median 10.2% across 5 years) and that higher disability correlated with greater fracture risk.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this analysis include the large sample size, access to medical record data that was abstracted by trained research personnel using validated methods, and the ability to link to population-based administrative health data for outcomes. However, the use of medical record data and administrative data has some limitations as well. Although the diagnosis of stroke was verified by physicians as recorded in the medical record, diagnosis of low-trauma fracture relied on administrative health data gathered from hospital or physician visits. Administrative health data are generally acknowledged to be less accurate than the medical record; however, previous research shows excellent sensitivity (>90%) and positive predictive value (>90%) of administrative health data for fractures.28 Some variables in the FRAX score were not included in stroke admission records and could not be reliably accessed using administrative data: parental history of hip fracture, history of smoking, greater alcohol use, race, weight, height, glucocorticoid use, and femoral neck bone mineral density. Therefore, we were unable to fully recreate the FRAX score in our database. Bone mineral density as determined by bone densitometry is an established predictor of fracture risk, but we did not have access to these data. However, we considered it unlikely that outpatient bone densitometry testing would be available to the clinician at the time the patient was hospitalized for stroke. In contrast to other fracture risk scores, which are designed to be implemented to predict fracture risk after bone densitometry is performed,29 our risk score is designed to be used at the time of patient discharge to determine which patients might benefit from bone densitometry screening, special programs for fall prevention, or empirical treatment with bisphosphonates in very high-risk patients, before any additional testing. In addition, in contrast to FRAX, which estimates 10-year fracture risk, the FRAC-Stroke predicts short-term (1-year) risk, which may be of greater clinical utility than 10-year risk in an older stroke population with a high competing risk of death. In the present study, mRS was assessed at discharge rather than at 90 days as is standard in stroke clinical trials; however, an assessment at discharge may be better than at 90 days so that steps such as assessments for fall prevention or osteoporosis screening can be taken earlier to prevent postdischarge fracture.

Risk prediction using the FRAC-Stroke score may help clinicians improve care by identifying individual patients at high risk for poststroke fracture, who could undergo targeted screening for osteoporosis using bone densitometry, or who would potentially benefit from empirical pharmacotherapy with bisphosphonates or from fall-prevention programs. Guidelines for fracture prevention, including vitamin therapy and osteoporosis screening and treatment, have been offered by the US Preventive Services Task Force30,31 and Osteoporosis Canada.32 Osteoporosis Canada recommends measuring bone mineral density in all women and men 65 years and older, and in menopausal women and men aged 50 years and older and have major risk factors.32 However, for patients with estimated risk greater than 20% across 10 years, pharmacologic treatment is recommended regardless of bone mineral density, although with a lower level of evidence.32 In the United States, guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force recommend screening all women 65 years and older as well as younger women with the same fracture risk as a 65-year-old white woman with no major risk factors (8.4% over 10 years, or 0.84% per year). The US guidelines state that the evidence for screening men is inconclusive.30

Conclusions

Given the evidence that stroke is a major risk factor for fracture, it may be reasonable to use the FRAC-Stroke risk score to identify stroke patients with a 1-year risk greater than 0.8% for screening with bone densitometry. For very high-risk individuals (1-year risk, ≥2.0%), empirical therapy with bisphosphonates could be considered regardless of bone mineral density. In this study, most patients in the validation cohort had an estimated 1-year fracture risk greater than 0.8% (13 365 of 13 968 [97.5%]), including 9656 (70.5%) who had estimated 1-year fracture risk of 2.0% or greater. The optimal timing for bone densitometry is unclear, because bone mineral loss may occur over a period of up to 1 year owing to acute stroke-related reduction in mobility.25,26 Further studies will be needed to better understand the optimal timing and health benefits of screening patients with stroke.33 In stroke survivors who have been screened for bone mineral density, it would be reasonable to follow existing guidelines for osteoporosis treatment; however, there are no randomized clinical trials of osteoporosis treatment specifically in recent stroke survivors.

eTable. Data Sources and Algorithms for Study Variables

eFigure. Cumulative Incidence of Low Trauma Fracture in the Derivation and Validation Cohorts Based on Risk Score Quintiles From the Derivation Cohort

References

- 1.Bustamante A, García-Berrocoso T, Rodriguez N, et al. Ischemic stroke outcome: a review of the influence of post-stroke complications within the different scenarios of stroke care. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;29:9-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster EJ, Barlas RS, Bettencourt-Silva JH, et al. Long-term factors associated with falls and fractures poststroke. Front Neurol. 2018;9:210. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myint PK, Poole KE, Warburton EA. Hip fractures after stroke and their prevention. QJM. 2007;100(9):539-545. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dennis MS, Lo KM, McDowall M, West T. Fractures after stroke: frequency, types, and associations. Stroke. 2002;33(3):728-734. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.103621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramnemark A, Nyberg L, Borssén B, Olsson T, Gustafson Y. Fractures after stroke. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8(1):92-95. doi: 10.1007/s001980050053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lisabeth LD, Morgenstern LB, Wing JJ, et al. Poststroke fractures in a bi-ethnic community. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21(6):471-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown DL, Morgenstern LB, Majersik JJ, Kleerekoper M, Lisabeth LD. Risk of fractures after stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25(1-2):95-99. doi: 10.1159/000111997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pouwels S, Lalmohamed A, Leufkens B, et al. Risk of hip/femur fracture after stroke: a population-based case-control study. Stroke. 2009;40(10):3281-3285. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.554055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanis J, Oden A, Johnell O. Acute and long-term increase in fracture risk after hospitalization for stroke. Stroke. 2001;32(3):702-706. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.3.702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapral MK, Fang J, Alibhai SM, et al. Risk of fractures after stroke: results from the Ontario Stroke Registry. Neurology. 2017;88(1):57-64. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Jonsson B, Dawson A, Dere W. Risk of hip fracture derived from relative risks: an analysis applied to the population of Sweden. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(2):120-127. doi: 10.1007/PL00004173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(4):385-397. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang J, Kapral MK, Richards J, Robertson A, Stamplecoski M, Silver FL. The Registry of Canadian Stroke Network: an evolving methodology. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2011;20(2):77-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapral MK, Hall RE, Stamplecoski M, et al. Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network—Report on the 2008/09 Ontario Stroke Audit. 2011; https://www.ices.on.ca/~/media/Files/Atlases-Reports/2011/RCSN-2008-09-Ontario-stroke-audit/Full report.ashx. Accessed November 4, 2018.

- 15.Kapral MK, Hall R, Fang J, et al. Association between hospitalization and care after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Neurology. 2016;86(17):1582-1589. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapral MK, Silver FL, Richards JA, et al. Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network: Progress Report 2001–2005. Toronto: Institute of Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Côté R, Battista RN, Wolfson C, Boucher J, Adam J, Hachinski V. The Canadian Neurological Scale: validation and reliability assessment. Neurology. 1989;39(5):638-643. doi: 10.1212/WNL.39.5.638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilanont Y, Komoltri C, Saposnik G, et al. The Canadian Neurological Scale and the NIHSS: development and validation of a simple conversion model. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;30(2):120-126. doi: 10.1159/000314715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133(6):601-609. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin PC, Lee DS, D’Agostino RB, Fine JP. Developing points-based risk-scoring systems in the presence of competing risks. Stat Med. 2016;35(22):4056-4072. doi: 10.1002/sim.6994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Pencina KM, Janssens AC, Greenland P. Interpreting incremental value of markers added to risk prediction models. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(6):473-481. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy K. A SAS macro to compute added predictive ability of new markers predicting a dichotomous outcome. SESUG 2010: Proceeding of SouthEast SAS User Groups. 2010. https://analytics.ncsu.edu/sesug/2010/SDA07.Kennedy.pdf. Accessed November 26, 2018.

- 23.Alba AC, Agoritsas T, Walsh M, et al. Discrimination and calibration of clinical prediction models: users’ guides to the medical literature. JAMA. 2017;318(14):1377-1384. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.12126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr, Demler OV. Novel metrics for evaluating improvement in discrimination: net reclassification and integrated discrimination improvement for normal variables and nested models. Stat Med. 2012;31(2):101-113. doi: 10.1002/sim.4348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaupre GS, Lew HL. Bone-density changes after stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(5):464-472. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000214275.69286.7a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramnemark A, Nyberg L, Lorentzon R, Englund U, Gustafson Y. Progressive hemiosteoporosis on the paretic side and increased bone mineral density in the nonparetic arm the first year after severe stroke. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9(3):269-275. doi: 10.1007/s001980050147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viscoli CM, Kent DM, Conwit R, et al. Scoring system to optimize pioglitazone therapy after stroke based on fracture risk. Stroke. 2018;50(1):95-100. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ray WA, Griffin MR, Fought RL, Adams ML. Identification of fractures from computerized Medicare files. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(7):703-714. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90047-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanis JA. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. Lancet. 2002;359(9321):1929-1936. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08761-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for osteoporosis to prevent fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521-2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Vitamin D, calcium, or combined supplementation for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1592-1599. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, et al. ; Scientific Advisory Council of Osteoporosis Canada . 2010 Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ. 2010;182(17):1864-1873. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carda S, Cisari C, Invernizzi M, Bevilacqua M. Osteoporosis after stroke: a review of the causes and potential treatments. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28(2):191-200. doi: 10.1159/000226578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Data Sources and Algorithms for Study Variables

eFigure. Cumulative Incidence of Low Trauma Fracture in the Derivation and Validation Cohorts Based on Risk Score Quintiles From the Derivation Cohort