Key Points

Question

How many suicide and unintentional firearm deaths among US residents aged 0 to 19 years could be prevented by a modest increase in safe household firearm storage?

Findings

This modeling study using Monte Carlo simulation estimated that 6% to 32% of youth firearm deaths (by suicide and unintentional firearm injury) could be prevented, depending on the probability that an intervention motivates adults who currently do not lock all household firearms to instead lock all guns in their home.

Meaning

Results of this modeling study suggest that approaches that will motivate adults who live in homes with youths to store firearms safely may prevent up to 32% of firearm deaths.

This modeling study uses Monte Carlo simulation and US Census Data, National Firearms Survey, and Centers for Disease and Prevention Compressed Mortality Files to estimate the association of safe firearm storage with firearm suicide and unintentional firearm deaths among youths.

Abstract

Importance

Firearm injury is the second leading cause of death in the United States for children and young adults. The risk of unintentional and self-inflicted firearm injury is lower when all household firearms are stored locked.

Objective

To estimate the reduction in youth firearm suicide and unintentional firearm mortality that would result if more adults in households with youth stored household guns locked.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A modeling study using Monte Carlo simulation of youth firearm suicide and unintentional firearm mortality in 2015. A simulated US national sample of firearm-owning households where youth reside was derived using nationally representative rates of firearm ownership and storage and population data from the US Census to test a hypothetical intervention, safe storage of firearms in the home, on youth accidental death and suicide. Data analyses were performed from August 3, 2017, to January 9, 2018.

Exposures

Observed and counterfactual household-level safe firearm storage (ie, storing all firearms locked), the latter estimated by varying the probability that a hypothetical intervention increased safe firearm storage beyond that observed in 2015.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Observed and counterfactual counts of firearm suicide and unintentional firearm mortality among youth aged 0 to 19 years, the latter estimated by incorporating an empirically based estimate of the mortality benefit expected from additional safe storage (beyond that observed in 2015).

Results

A hypothetical intervention among firearm owners residing with children with a 20% probability of motivating these owners to lock all household firearms was significantly associated with a projected reduction in youth firearm mortality (median incidence rate ratio = 0.90; interquartile range, 0.87-0.93). In the overall model, 6% to 32% of deaths were estimated to be preventable depending on the probability of motivating safer storage.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this modeling study suggest that a relatively modest uptake of a straightforward safe storage recommendation—lock all household firearms—could result in meaningful reductions in firearm suicide and unintentional firearm fatalities among youth. Approaches that will motivate additional parents to store firearms safely are needed.

Introduction

In 2015, 13 million US households with children also contained firearms.1 In that same year approximately 14 000 youth younger than 20 years were treated for nonfatal firearm injuries,2 and 2800 youths died by gunfire (of whom more than 1100 died by suicide or unintentional firearm injury).3 The firearm used in suicides comes from the youth’s home in approximately 9 of 10 deaths, and from the home of the victim or the victim’s relative or friend in 9 of 10 unintentional firearm deaths.4

The presence of a gun in a household substantially increases the risk of suicide and unintentional firearm death.5,6,7,8,9,10,11 Moreover, when guns are present in a home with youth, storing all firearms locked as opposed to unlocked, unloaded as opposed to loaded, and storing all ammunition locked and separate from firearms have each been associated with a reduced risk of intentional self-inflicted and unintentional firearm injuries.4

Although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that if parents decide to keep firearms in their home, all firearms should be locked, unloaded, and separate from ammunition,12 only 3 of 10 adults in households with children report storing all guns unloaded and locked up.1 Consistent with this finding, data suggest that few gun owners appreciate the risks posed by household firearms, let alone how that risk is modified for youth by storage practices.13

The present study is the first, to our knowledge, to estimate of the number of youths whose lives could be saved were additional gun-owning adults to adopt safer firearm storage practices. In particular, we estimate the reduction in firearm suicide and unintentional firearm deaths that would result from a hypothetical “lock all firearms” intervention aimed at adults living in homes with youth and guns (eg, public safety campaigns, incentives for primary care doctors to follow American Academy of Pediatrics firearms guidelines, or firearm storage laws).

Methods

This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. We conducted a Monte Carlo simulation using household-level data on firearm ownership and storage, and contemporaneous data on firearm suicide and unintentional firearm injury among US youth (defined as children and adolescents aged 0-19 years) in 2015. The year 2015 was selected as this was the most recent year for which several key data elements were available. The age range of 0 to 19 years was chosen because, to our knowledge, it is the age group for which the only published estimate of the observed outcomes of firearm storage practices on firearm suicides and unintentional firearm injuries among youth are available.14 Data analyses were performed from August 3, 2017, to January 9, 2018. This project was deemed exempt from human subject review by the institutional review board of Boston Children’s Hospital.

Data Sources

All sources of data used to generate the final data set are summarized in Table 1. Estimates for national firearm ownership prevalence and firearm storage practices among households in which youth (aged <18 years) reside were taken from the National Firearms Survey (NFS), a nationally representative probability-based online survey sample of US adults conducted in 2015 (n = 3949; response rate, 55%). Details of the NFS methodology are described elsewhere.16 The survey included the following: “The next questions are about working firearms. Throughout this survey we use the word gun to refer to any firearm, including pistols, revolvers, shotguns and rifles, but not including air guns, bb guns, starter pistols or paintball guns.” This preamble was followed by the question: “Do you or does anyone else you live with currently own any type of gun?” Those who responded affirmatively were asked, “Do you personally own a gun?” Firearm owners (those who answered “yes”) were asked to specify the storage status of their firearms (locked/unlocked, loaded/unloaded).

Table 1. Data Sources for Monte Carlo Simulations.

| Variable | Values | Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| National firearm suicide and unintentional fatality estimates among youth aged 0-19 y (2015) | 1117 | Compressed Mortality File | National Center for Health Statistics15 |

| National firearm ownership prevalence among households containing children and adolescents aged 0-17 y (2015), % | 33.4 | National Firearm Survey | Azrael et al,16 2017 |

| National estimates of households containing children and adolescents aged 0-17 y (2015) | 37 117 391 | American Community Survey | US Census Bureau17 |

| Prevalence of unsafe (ie, unlocked) firearm storage among owners cohabitating with children and adolescents aged 0-17 y, % (95% CI) | 48.6 (43.4-53.8) | National Firearm Survey | Unpublished data16 |

National counts of firearm suicide and unintentional fatalities in 2015 among persons 19 years and younger were taken from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Compressed Mortality Files (CMF).15 Deaths due to firearm suicide and unintentional injury were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes X72-X74 and W32-W34, respectively.

National counts of the number of households that contain residents younger than 18 years in 2015 were taken from The American Community Survey, a nationally representative survey administered by the US Census.17

Approach and Measures

To estimate the association of a hypothetical firearm storage intervention with firearm suicide and unintentional firearm deaths among youth 19 years and younger, we assumed that all deaths resulted from firearms kept in homes where youth resided. Under this assumption, we compared observed fatalities in 2015 (taken from the CMF, as noted above) with deaths in a counterfactual 2015 generated using Monte Carlo simulation methods in which fewer homes with youth had unlocked guns.

To operationalize this approach, we first created a data set of homes with youth and guns consisting of 12 397 209 observations (households), based on calculations that multiplied the number of US households with youth younger than 18 years (37 117 391, as taken from the census) by the estimated prevalence of firearm ownership among households that contain youth younger than 18 years (33.4%, as taken from the NFS).1,16 Next, we randomly selected 46.8% of these households (ie, reflecting the prevalence of unlocked firearm storage among owners cohabiting with youth, provided by the 2015 NFS)1 to which we applied an “unlocked” storage designation. We chose locked/unlocked status (as opposed to definitions comprising both locked/unlocked and loaded/unloaded designations, with or without requirements pertaining to ammunition location) to simulate the outcomes associated with a relatively straightforward, single-component intervention (ie, “store your firearms locked”).

We then created a death indicator variable, coded positive for a selected set of observations (ie, households), equal to the number of observed suicide and unintentional firearm deaths among persons aged 0 to 19 years in 2015 (n = 1117, of which 1017 were suicides, as provided by the CMF). In approximately 10% of cases, the firearm used in youth suicides and unintentional firearm deaths does not come from the home of the victim or a friend or relative4 (eg, among youth aged 18 to 19 years who possess their own firearm and live away from their parents) and thus there might be no benefit from an intervention that affects adult storage practices. To address this potential overestimate of benefit, we reduced the number of potentially preventable deaths by 10%, from 1117 to 1005.

To construct data consistent with the empirical evidence that safe storage protects against firearm fatalities, deaths were distributed to households across our locked vs unlocked storage designation such that the risk ratio (proportion of deaths among households with all firearms locked divided by proportion of deaths among households with at least 1 firearm unlocked) was equivalent to the corresponding odds ratio (OR) reported in Grossman et al (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.17-0.45).14 This calculation assumes the OR is a proxy for the risk ratio, which can be justified in this case because the outcome, pediatric suicide and unintentional firearm death, is rare (see eAppendix 1 in the Supplement for additional details). It is reasonable to combine deaths by suicide with deaths by unintentional firearm injury because Grossman and colleagues14 found that the observed protective outcomes of storing firearms locked on youth unintentional death (OR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.10-0.64) are nearly identical to the observed protective outcomes on suicide (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.16-0.47). As such, 223 deaths were randomly assigned to households where all guns were stored locked and 782 deaths were randomly assigned to households where at least 1 firearm was unlocked.

We then generated our counterfactual scenarios. First, a fraction of homes originally designated as storing firearms unlocked were randomly selected to respond to the hypothetical intervention and were recategorized as homes that store all firearms locked. Specifically, among those observations (households) that were not already categorized as locked, we randomly selected a set of homes to receive an augmented locked storage designation, where each observation had a specified probability, ranging from 10% to 50% in 10% increments, of receiving a positive designation (ie, becoming a household where all firearms are locked).

Second, we assigned the mortality benefit expected from improved storage. To do so, we used crude cell count data from Grossman et al14 to calculate the attributable (ie, prevented) fraction (OR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.43-0.78), which represents the probability that locking all household firearms would have prevented a death that otherwise occurred (see eAppendix 2 in the Supplement for additional details and sensitivity analyses). Using this derived parameter, we randomly selected homes among those with the augmented locked storage designation to receive an effectively preventive designation, meaning that firearms in the given household could not cause a death.

Finally, we created a counterfactual death variable. This variable is equal to the observed death variable except where an observation met all of the following conditions: (1) it was not designated as locked; (2) it had an augmented locked storage designation; (3) it had an effectively preventive designation; and (4) it had a positive value for the observed death variable. In these cases, the death was negated (ie, recoded to zero). This counterfactual death variable represents the deaths that would have occurred, given adherence with a hypothetical storage intervention.

Statistical Analysis

We created a long data set with a single composite fatality variable in which each household is represented by 2 observations: first, where the composite fatality variable equaled the unaltered CMF death indicator variable; and second, where the composite fatality variable equaled the counterfactual death variable. We compared the observed vs the counterfactual death rate using a Poisson regression model with the composite fatality variable as the dependent variable and observation type (empirical vs counterfactual) as the independent variable. From each model we derived the incidence rate ratio (IRR) and 95% CI.

Each model estimation represented 1 repetition. We used the simulate command as implemented in Stata SE, version 14.2, (StataCorp LLC) to estimate 1000 repetitions of the model for each “augmented locked storage” probability under consideration (ie, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50%). An α level of .05 was used to determine statistical significance. All statistical tests were 2-sided. To evaluate the results of the simulation, we examined the median IRR with the corresponding interquartile range (IQR), the proportion of repetitions with a significantly protective observed outcome of counterfactual safe storage, and the estimated number of deaths prevented (equal to the observed death count minus the counterfactual death count).

We performed several sensitivity analyses. First, we reran the simulations using the lower and upper bounds, respectively, of the attributable fraction CI (ie, 43% and 78%). These sensitivity analyses were repeated for each hypothetical locked storage probability under consideration. Second, recognizing that locking guns may also mitigate the occurrence of nonfatal firearm injuries among youth, we reran our simulations while including firearm injuries. Unintentional injury counts among youth 19 years or younger in 2015 were taken from the web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System, maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (n = 2724; self-inflicted nonfatal injuries were not included because the estimate was based on too few cases to be considered statistically reliable). Based on evidence that, among nonfatal youth firearm injuries, approximately 66% occurred in the home,4 we reduced the number of potentially preventable nonfatal injuries by 33%, from 2724 to 1798, giving a combined fatal and nonfatal injury count for this sensitivity analysis of 2803 (1005 + 1798).

Results

The results of simulations assuming an effectively preventive proportion of 64%, while varying the augmented locked storage probability from a 10% increase over the empirical 2015 baseline to a 50% increase, in 10% increments, are displayed in Table 2. The median (IQR) IRR assuming an augmented locked storage probability of 10% was 0.95 (0.95-0.96). However, none of the repetitions was significantly protective. After increasing the augmented locked storage probability to 20%, the median (IQR) IRR decreased to 0.90 (0.89-0.91) and 93.1% of these repetitions were significantly protective. Each additional increase of the augmented locked storage probability (30%, 40%, and 50%) decreased the median (IQR) IRR by approximately 5% (0.85 [0.84-0.86]; 0.80 [0.79-0.81]; and 0.75 [0.74-0.76], respectively).

Table 2. Simulation of Augmented Locked Firearm Storage (Percent Increase Over Empirical Baseline) and Youth Unintentional Deaths and Suicides by Firearm, 2015a.

| Probability of Augmented Locked Storage, % | Summary of Model Estimates | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence Rate Ratio | Deaths Prevented, No. | ||

| Median (IQR) [Range] | Significant Repetitions, %b | Median (IQR) [Range] | |

| 10 | 0.95 (0.95-0.96) [0.93-0.98] | 0 | 50 (45-55) [25-70] |

| 20 | 0.90 (0.89-0.91) [0.87-0.93] | 93.1 | 99 (93-106) [72-135] |

| 30 | 0.85 (0.84-0.86) [0.81-0.88] | 100 | 150 (143-158) [117-191] |

| 40 | 0.80 (0.79-0.81) [0.76-0.84] | 100 | 200 (192-208) [162-239] |

| 50 | 0.75 (0.74-0.76) [0.71-0.80] | 100 | 251 (242-260) [204-289] |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Each row represents a simulation; 1000 repetitions were estimated per simulation. All simulations assumed a 64% probability that safe storage would prevent a death that would have otherwise occurred.

Percentage of repetitions of a given simulation where the upper bound of the CI for the incidence rate ratio is less than 1.

The estimated number of deaths prevented is displayed in Table 2. The median (IQR) number of deaths prevented per repetition ranged from 50 (45-55) for simulation repetitions using 10% augmented storage probabilities, to 251 (242-260) for simulation repetitions using 50% augmented storage probabilities. We estimated that among all 782 youth firearm suicide and unintentional deaths assigned to firearms that were designated as unlocked and preventable by our hypothetical intervention, 50 (6.4%) to 251 (32.1%) could be prevented by a hypothetical storage intervention, depending on the proportion of adult firearm owners living with youth who newly lock all household firearms.

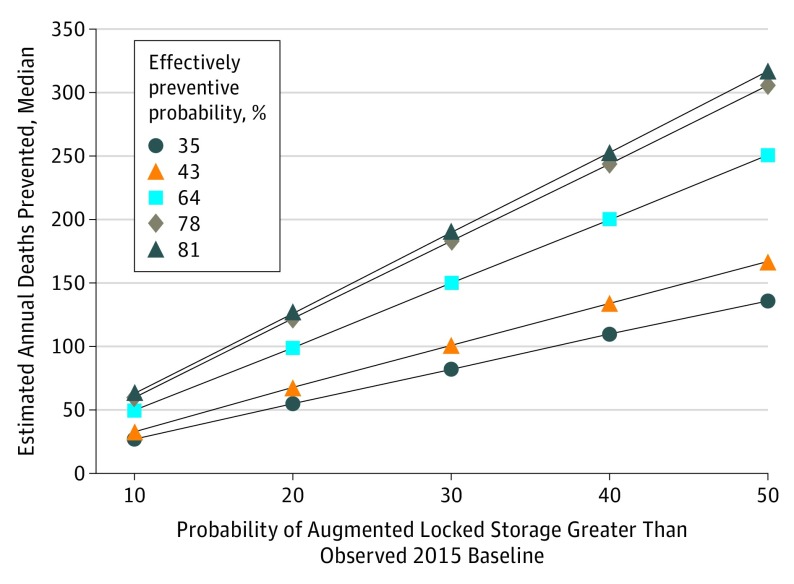

Table 3 shows sensitivity analyses using the lower and upper bounds of the effectively preventive point estimate (43% and 78%, respectively). With the effectively preventive proportion set to 43% and an augmented locked storage probability of 30%, 93.7% of the repetitions were significantly protective. With the effectively preventive proportion set to 78%, all repetitions were significantly protective as the augmented storage probability reached 20%. The Figure displays the median deaths prevented across a range of augmented storage probabilities and effectively preventive values, including the 95% and 99% CI bounds of the effectively preventive point estimate.

Table 3. Sensitivity Analyses of the Probability That Augmented Locked Storage Prevents a Death That Would Have Otherwise Occurreda.

| Probability of Augmented Locked Storage | Incidence Rate Ratio | Deaths Prevented, Median (IQR) [Range] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) [Range] | Significant Repetitions, %b | ||

| 43% Probability That Safe Storage Would Prevent a Death That Would Have Otherwise Occurred | |||

| 10% | 0.97 (0.96-0.97) [0.95-0.98] | 0 | 33 (30-37) [17-54] |

| 20% | 0.93 (0.93-0.94) [0.90-0.96] | 0.6 | 68 (62-72) [41-100] |

| 30% | 0.90 (0.89-0.91) [0.87-0.93] | 93.7 | 101 (94-108) [71-129] |

| 40% | 0.87 (0.86-0.87) [0.83-0.90] | 100 | 134 (128-141) [102-175] |

| 50% | 0.83 (0.83-0.84) [0.79-0.87] | 100 | 167 (159-175) [129-208] |

| 78% Probability That Safe Storage Would Prevent a Death That Would Have Otherwise Occurred | |||

| 10% | 0.94 (0.93-0.95) [0.92-0.96] | 0 | 60 (55-66) [36-84] |

| 20% | 0.88 (0.87-0.89) [0.84-0.91] | 100 | 122 (115-129) [89-158] |

| 30% | 0.82 (0.81-0.82) [0.78-0.86] | 100 | 183 (176-192) [144-225] |

| 40% | 0.76 (0.75-0.77) [0.72-0.80] | 100 | 244 (235-253) [202-283] |

| 50% | 0.70 (0.69-0.71) [0.65-0.74] | 100 | 306 (296-315) [265-356] |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Each row represents a simulation; 1000 repetitions were estimated per simulation.

Percentage of repetitions of a given simulation where the upper bound of the CI for the incidence rate ratio is less than 1.

Figure. Estimate of Median Deaths Prevented, Stratified by Probability of Augmented Locked Storage and Effectively Preventive Probability.

Median estimate across 1000 simulation repetitions of youth unintentional and suicide firearm deaths prevented in 2015, stratified by probability of augmented locked firearm storage (over empirical baseline) and effectively preventive probability (ie, probability that safe storage would prevent a death that would otherwise have occurred); values are the point estimate (0.64) and the upper and lower bounds of the 95% and 99% CIs.

In our second set of sensitivity analyses, we included nonfatal firearm injuries along with deaths. Using the Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS), we arrived at a total count of firearm shootings among youth 19 years and younger in 2015 of 2803 (ie, 1005 deaths plus 1798 unintentional injuries). With an effectively preventive probability of 64% and the augmented locked storage probability set at 20%, 100% of repetitions were statistically protective, and the number of firearm injuries (fatal and nonfatal) prevented ranged from 235 to 323, with a median (IQR) of 280 (270-290).

Discussion

Fewer than 1 in 3 US homes with youth and firearms follow American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations to store all household firearms locked and unloaded.1 At least 15 million youth live in households with firearms stored in a manner inconsistent with American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines.1,18 As such, saving lives through promoting safer storage has great, but as yet unrealized, potential. Our findings suggest that a relatively modest improvement in firearm storage practices induced by a hypothetical intervention that prompted adults in households with youth to lock all household firearms could result in substantial, statistically significant reductions in firearm suicide and unintentional fatalities among US youth. Specifically, we found that if 20% of households storing at least 1 gun unlocked moved in a single year to locking all guns (eg, from 53.2% of households locking all firearms to 62.6% of households), between 72 and 135 youth firearm fatalities, and between 235 and 323 youth firearm shootings (ie, nonfatal injuries and deaths combined) could be prevented.

Our results are based on motivating adult firearm owners in homes with youth to lock all household firearms that were not locked in the absence of our hypothetical intervention. Locking firearms is not the only way to reduce risk of injury from household firearms. Indeed, Grossman et al14 reported that unloading firearms, as well as locking ammunition, provided additional protective benefits. To the extent that gun owners who respond to an intervention by locking all guns and adopting other safer storage practices, our estimates are conservative.

Our findings that youth firearm suicide rates may decline substantially if at least 20% of households with youth moved from storing guns unlocked to locking all guns do not speak directly to the association that such an intervention may have on overall suicide rates. However, it is likely that the number of lives saved is roughly approximated by the number of firearm suicides averted, based on evidence from case-control and ecologic studies showing that the positive relationship between household firearm availability and overall suicide is entirely attributable to an elevated rate of suicide by firearms and that suicide by nonfirearm methods is trivially associated with firearm availability (ie, lethal substitution of nonfirearm methods is minimal).5,6,7,8,10,11,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 Moreover, for the age group studied herein, lethal substitution is less likely than among older age groups because the case-fatality rate for commonly used nonfirearm suicide methods is inversely related to age.26

Limitations

Our results should be interpreted in the light of additional considerations. First, our analysis relied on estimates derived from a single study conducted more than 15 years ago, Grossman et al,14 the only published study that quantifies the relationship between storage practices among youth and the risk of firearm injuries. However, representativeness is not necessary for the mechanics of causal association measured in one study to be transportable to other settings.27 Indeed, there is no a priori reason to think that either the passage of time, sociodemographic differences (between youth studied by Grossman and colleagues14 compared with youth today), or spatial heterogeneity with regard to rates of firearm death and adoption of improved storage practices would materially alter the extent to which an unlocked household firearm, relative to a locked firearm, increases the risk of firearm suicide (or unintentional firearm death) to youth. Thus, our estimates of the net benefit are not likely to be significantly affected by these considerations. Second, although the point estimate for the observed protective outcomes of locking guns on suicide attempts (ie, 0.27) in the study by Grossman and colleagues14 pertains to both fatal and nonfatal attempts, it seems a reasonable approximation of an OR applying to suicide deaths, because 95% of attempts in Grossman et al proved fatal. By contrast, the OR (ie, 0.26) for unintentional injuries pertains to both the 52% of events that proved fatal and the 48% that did not. To the extent that gun storage has a differential association with the lethality of an unintentional injury, as opposed to the risk of the injury itself, our results might overestimate or underestimate the number of unintentional deaths averted. However, since the overall effect on deaths averted largely reflects firearm suicides prevented, our overall estimates are likely reasonable approximations, even if the assumption about storage regarding fatal vs nonfatal unintentional firearm injury does not hold.

Conclusions

To date, the evidence characterizing existing interventions, such as office-based pediatrician counseling28,29,30,31 and legislative initiatives that provide penalties for misuse by youth of unsafely stored firearms,32,33 is mixed. Our findings that a relatively modest uptake of a straightforward recommendation to lock all household firearms is likely to result in meaningful reductions in firearm suicide and unintentional firearm fatalities among youth underscores the need to further develop and test approaches that will more effectively motivate parents to store firearms safely.

eAppendix 1. Calculation to Distribute Firearm Deaths Across the Locked vs Unlocked Firearm Storage Designations to Reflect the Evidence That Safe Storage Protects Against Firearm Fatalities

eAppendix 2. Sensitivity Analysis for the Attributable Fraction Estimate

References

- 1.Azrael D, Cohen J, Salhi C, Miller M. Firearm storage in gun-owning households with children: results of a 2015 national survey. J Urban Health. 2018;95(3):295-304. . doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-0261-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS): nonfatal injury reports. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/nonfatal.html. Published 2018. Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS): fatal injury reports https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal.html. Published 2015. Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 4.Grossman DC, Reay DT, Baker SA. Self-inflicted and unintentional firearm injuries among children and adolescents: the source of the firearm. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(8):875-878. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.8.875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Firearm availability and unintentional firearm deaths, suicide, and homicide among 5-14 year olds. J Trauma. 2002;52(2):267-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Somes G, et al. . Suicide in the home in relation to gun ownership. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(7):467-472. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208133270705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brent DA, Perper JA, Allman CJ, Moritz GM, Wartella ME, Zelenak JP. The presence and accessibility of firearms in the homes of adolescent suicides: a case-control study. JAMA. 1991;266(21):2989-2995. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03470210057032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Baugher M, Schweers J, Roth C. Firearms and adolescent suicide: a community case-control study. AJDC. 1993;147(10):1066-1071. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160340052013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D, Vriniotis M. Firearm storage practices and rates of unintentional firearm deaths in the United States. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37(4):661-667. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2005.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller M, Hemenway D. The relationship between firearms and suicide: a review of the literature. Aggress Violent Behav. 1999;4(1):59-75. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(97)00057-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anglemyer A, Horvath T, Rutherford G. The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(2):101-110. doi: 10.7326/M13-1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowd MD, Sege RD; Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention Executive Committee; American Academy of Pediatrics . Firearm-related injuries affecting the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1416-e1423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conner A, Azrael D, Miller M. Public opinion about the relationship between firearm availability and suicide: results from a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(2):153-155. doi: 10.7326/M17-2348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, et al. . Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707-714. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.6.707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention About compressed mortality, 1999-2016. CDC Wonder, US Dept of Health and Human Services. https://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html. Accessed March 28, 2018.

- 16.Azrael D, Hepburn L, Hemenway D, Miller M. The stock and flow of U.S. firearms: results from the 2015 National Firearms Survey. Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci. 2017;3(5):38-57. doi: 10.7758/RSF.2017.3.5.02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United States Census Bureau. American Fact Finder. 2015. American community survey 1-year estimates, table S1101: households and families. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_15_1YR_S1101&prodType=table. Published 2015. Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 18.Scott J, Azrael D, Miller M. Firearm storage in homes with children with self-harm risk factors. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20172600. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller M, Hemenway D. Guns and suicide in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(10):989-991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0805923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wintemute GJ, Parham CA, Beaumont JJ, Wright M, Drake C. Mortality among recent purchasers of handguns. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(21):1583-1589. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911183412106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller M, Swanson SA, Azrael D. Are we missing something pertinent? a bias analysis of unmeasured confounding in the firearm-suicide literature. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):62-69. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cummings P, Koepsell TD, Grossman DC, Savarino J, Thompson RS. The association between the purchase of a handgun and homicide or suicide. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(6):974-978. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.6.974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grassel KM, Wintemute GJ, Wright MA, Romero MP. Association between handgun purchase and mortality from firearm injury. Inj Prev. 2003;9(1):48-52. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.1.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller M, Lippmann SJ, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Household firearm ownership and rates of suicide across the 50 United States. J Trauma. 2007;62(4):1029-1034. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000198214.24056.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller M, Barber C, White RA, Azrael D. Firearms and suicide in the United States: is risk independent of underlying suicidal behavior? Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(6):946-955. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. The epidemiology of case fatality rates for suicide in the Northeast. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(6):723-730. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothman KJ, Gallacher JEJ, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):1012-1014. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carbone PS, Clemens CJ, Ball TM. Effectiveness of gun-safety counseling and a gun lock giveaway in a Hispanic community. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(11):1049-1054. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.11.1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barkin SL, Finch SA, Ip EH, et al. . Is office-based counseling about media use, timeouts, and firearm storage effective? results from a cluster-randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):e15-e25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grossman DC, Cummings P, Koepsell TD, et al. . Firearm safety counseling in primary care pediatrics: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1, pt 1):22-26. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sidman EA, Grossman DC, Koepsell TD, et al. . Evaluation of a community-based handgun safe-storage campaign. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):e654-e661. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siegel M, Pahn M, Xuan Z, et al. . Firearm-related laws in all 50 US states, 1991-2016. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(7):1122-1129. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hepburn L, Azrael D, Miller M, Hemenway D. The effect of child access prevention laws on unintentional child firearm fatalities, 1979-2000. J Trauma. 2006;61(2):423-428. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000226396.51850.fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Calculation to Distribute Firearm Deaths Across the Locked vs Unlocked Firearm Storage Designations to Reflect the Evidence That Safe Storage Protects Against Firearm Fatalities

eAppendix 2. Sensitivity Analysis for the Attributable Fraction Estimate