Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In contemporary times, employers use information available on the social media (SM) to assess attitudes before interviews and recruitment of potential employees. It is used as one of the criteria to rank applicants for acceptance as residents in the Middle East. In this study, an evaluation was done of this new practice in which program directors (PDs) take into account e-professionalism for the acceptance of applicants. It was a national study of all 41 hospitals in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia involved in Saudi board family medicine training programs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A 36-item questionnaire was administered to PDs. Next, a focus group discussion (FGD) was held, after which there was social listening. We recorded the FGD. There was verbatim transcription and coding of the qualitative data. We held social listening using Keyhole. The percentage of positive attitudes (PPAs) was normally distributed; we tested its relationship with different factors by comparing the mean score values among categories using the Student's t-test and one-way analysis of variance.

RESULTS:

The average PPA toward the ranking of applicants by using their SM was 55.5% ± 17.3% (median: 56.6%). The average PPA was higher in those who used SM to communicate with residents (60.2% ±19.5%) than those who did not (49.4% ±12%; P = 0.04), even after adjusting for familiarity with Internet use. Directors in hospitals of the Ministry of Education had higher percentages; these figures, however, are not statistically significant. PDs considered the importance of establishing culturally acceptable guidelines for the assessment of e-professionalism and social reputation.

CONCLUSIONS:

Culturally appropriate, bioethical regulations that meet the needs of modern times should be designed. We need to solve ethical dilemmas, especially with regard to privacy in SM.

Keywords: Digital media, health, professionalism, program directors, residency

Introduction

The use of social media (SM), now a powerful tool of worldwide influence, is rising exponentially. This revolution is transforming and affecting both individuals and the entire societies.[1]

SM reflects both contemporary and future generations' impressions, expressions, emotions, behaviors, and social reputation. Using SM profiles for the selection of residents and the recruitment of employees is part of this digital revolution. In addition to the conventional face-to-face interviews, program directors (PDs) can now find more about applicants' behavior by using technology.[2]

The PDs of Saudi board specialties follow certain standards for the selection of high-caliber candidates with a deep sense of morality and professionalism.[3] However, the process of selection has to be improved by adding online professionalism (e-professionalism) in order to keep pace with development around the globe.

The adoption of SM platforms presents new challenges and ethical dilemmas such as patients' privacy and confidentiality, which must be strictly maintained.

The current debate going on in the professional space and social life is the extent to which one's personal behavior could affect one's professional identity; the scope remains unclear. We surveyed the perspectives of PDs to investigate this issue.

Many studies have examined the availability of guidelines on using SM as a selection tool for residents. There are no established institutional policies to determine the appropriateness of using online information for this purpose.[4,5,6,7,8,9] Researchers emphasize the importance of educational programs for PDs to improve selection and for students to boost their e-professionalism. Recent graduates might not be able to avoid the risk of misusing SM.[10]

Future evaluations of applicants might shift from simply the traditional interviews of applicants to a consideration of an applicant's e-professionalism and a review of their SM records as well as a face-to-face interview, owing to the growing importance of e-professionalism, especially since the current global movers/shakers are generation Y and Z. The term “the digital generation refers to those born from the mid-1980s to the early 2000s, a time of widespread technology. These are now either graduating from high school, applying to go to college or looking for employment, and to become the current world movers.[11]

Many references have defined e-professionalism as conventional professionalism that occurs through SM.[6,12] This definition is vague, but health-care professionals still question the appropriateness of some behaviors on SM.[6,12]

We found a few studies that discussed the e-professionalism of residency program candidates. In November 2016, a study investigating the use of SM by surgery PDs was published; 11% of them indicated that they would reject applicants because of unprofessional online behavior. About 10% reported that they would take formal disciplinary action against residents who demonstrated inappropriate online behavior. Moreover, 68% agreed to the importance of educating residents on the safe use of SM.[7]

In 2013, a cohort study tried to find the applicants' accounts on SM: 85% of the accounts were public and 16% had inappropriate posts.[13]

Furthermore, in 2012, a study showed that >50% of the PDs said that unprofessional behavior in applicants' SM profiles could adversely affect their acceptance.[8]

A US nationwide survey in 2012 showed that 69% of those who currently use SM would continue during the admission process. Researchers stress the significance of the awareness of e-professionalism because the use of SM by PDs is increasing.[4] In another study, 33.3% of PDs ranked an applicant lower because of unprofessional behavior on SM.[5] Similarly, in 2012, 132 anesthesiology PDs agreed on the need to have clear policies to regulate the use of SM in their selection process.[4]

A study of PDs revealed that 89% of the respondents believed that what an applicant posted was a reasonable target for criticism and judgment on their behavior/professionalism.[2] In other investigations, some PDs concurred that e-professionalism was critical and could predict an applicant's future practice in terms of confidentiality/protection of patient information.[4,5,7]

To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in the Middle East to assess the attitudes of PDs toward the ranking of applicants for residency programs using their SM accounts as a criterion of acceptance.

Materials and Methods

We distributed a total of 41 questionnaires to all family medicine PDs (FMPDs) around the kingdom; 39 completed the questionnaires (95.12% response rate). For this cross-sectional survey, a web-based questionnaire was used. The questionnaire was distributed through a link sent to the directors' emails to minimize selection bias (due to lack of technology savvy). A data collector was assigned to each province to distribute the questionnaires manually to PDs who were not accustomed to technology/web-based surveys. The PDs were asked to complete the questionnaires by themselves.

For our qualitative technique (semi-structured interview), the FMPDs from the Eastern provinces and one PD from Najd province were invited to participate in the focus group discussion (FGD). We chose Eastern province's PDs because it was the province with the highest number of FMPDs; all of whom took part. We aimed to assess the experience of SM use and explain the results obtained during the quantitative phase through the following:

The FGD (semi-structured interview style)

Social listening (an SM platform assessment of the PDs' accounts).

SM listening consists of “listening and responding to the conversation on individuals on SM websites”[14] and is also known as SM monitoring. Only two of the PDs who joined the FGD had active accounts that could be analyzed; the rest did not have any or what they had was inactive. We employed the SM analytics tool Keyhole to analyze the accounts and check PDs' engagement in the SM from February 22, to March 25, 2018. At that stage, our FGD results had been completed. The study period was from November 2017 to April 2018.

We held the FGD on December 18, 2017, with ten FMPDs, including an FMPD expert on SM, from the Nejd Province. A SM engineer, and a physician who is an SM-blogger, facilitated the discussion.

A formal letter was sent to the training director of El Hasa Province in order to invite the FMPD. Those who agreed to participate were asked to arrive about 1 h prior to the scientific committee meeting.

For the quantitative section, we employed a 36-item questionnaire which we adapted from a previous study,[8] after permission had been obtained from the authors to use their questionnaire with modifications.[3] Two faculty members performed face validity and pilot tested ten consultants to ensure clarity. The questionnaire's reliability was deemed good based on the Cronbach's alpha (0.89).

The questionnaire was in three parts. The first covered demographic data. The second was on familiarity with technology, reasons that might lower an applicant's ranking, and professional usage. The third part had questions on a 5-point Likert scale to assess PDs' attitude in the selection process.

The scores of 2 of the 15 questions in the third section were reversed because the high scores of those items indicated a negative attitude. We calculated the percentage of positive attitude (PPA) score as the sum of scores of the 15 questions × 100/75. Attitudes were categorized as negative (<50%), neutral (50−< 75%), and positive (+75%).

The data were described using frequency and percentage. The PPA was normally distributed; its relationship with different factors was tested by comparing the mean score values between different groups using the Student's t-test and ANOVA.

Regarding the qualitative aspect, the FGD was held for 75 min or until the data reached saturation. The questions were self-constructed [Table 1]. The session was audio-recorded so that it could be transcribed verbatim.

Table 1.

Focus group discussion items

| Semi-structured interviews: Topic guidance of all questions in the focus group discussion was open ended |

|---|

| 1. What is your opinion on ranking applicants for residency programs using their SM accounts? Why? (Using SM as one of the ranking criteria) |

| 2. If the criteria of admissions boards were to mandate screening applicants by looking at their SM accounts before acceptance, would you prefer primary (before interviewing the applicant) or secondary screening? Why? |

| 3. In your opinion, how does the use of SM platforms to rank applicants breach their privacy? |

| 4. How can we choose and use these platforms for ranking the criteria applied to applicants? |

| 5. In your opinion, what is important in terms of setting rules/regulations when using these platforms to rank criteria? |

| 6. List your general recommendations |

SM=Social media

After completing the verbatim transcription, a qualitative interpretive examination was done using inductive content analysis and color coding.

Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, and informed written consent was taken from all the participants. Participation was voluntary.

Results

For the quantitative part of the study, 39 out of 41 PDs from all the five provinces took part (for a response rate of 95%): Eastern province (13), Western province (10), the Central and Southern provinces (7 each), and the Northern province (2). Almost 30 (77%) PDs were male and 9 were female. They ranged in age from 34 to 65 years, with an average age of 45.7 ± 7.7 years. On an average, they had earned their most recent academic degree 10 years prior (between 4 and 30 years prior). The duration of being a PD varied from 3 months to 8 years, with a median of 3 years. Almost 87% (34) had other responsibilities besides being a PD (e.g., a faculty member or chairperson). With regard to residents' applications to their training programs, they received 4 to 120 applications (with an average of 30) each year, while the number of admissions ranged from 1 to 40, with a median of 12, and an acceptance rate of 3% to 100%, with a median of 46.7%. (Please note that the figures do not show these data).

About 25 PDs (64%) mentioned that their hospitals had an SM profile: 3 in the form of official websites, 7 on LinkedIn, 22 on Twitter, 10 on Facebook, 3 on Snapchat, 3 on Instagram, and 2 on YouTube; 4 directors (10.3%) did not know if their hospital had an SM profile. The majority (84.6%) had personal SM profiles: Twitter (79%), Facebook (73%), LinkedIn (52%), Instagram (39%), YouTube (36%), SlideShare (15%), WhatsApp (74.4%), Slack (9%), and Edmodo (3%).

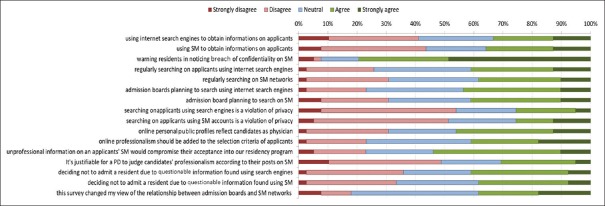

More than half (56%) of the PDs were very familiar with searching for individuals using Internet search engines, 41% were somewhat familiar, while 2.6% were not at all familiar. As for searching for people on SM networks, 38.5% of PDs were very familiar, 46.2% were somewhat familiar, and 15.4% were not at all familiar [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Distribution of program directors according to familiarity with Internet usage

Concerning duration, 36% spent <1 h a day on a social network, 25.6% from 1 to 2 h, and the rest spent 4 h or more. More than half (56.4%) mentioned using SM to communicate with their residents. (Please note that the tables do not show these data).

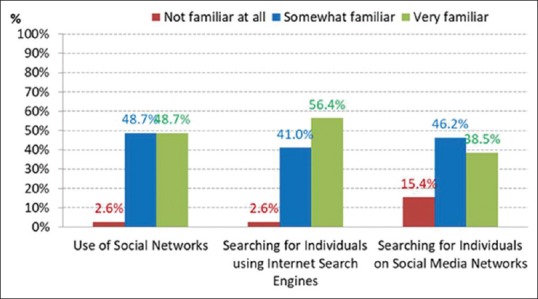

The PPA comprised 15 items, with a Cronbach's α of 0.895 [Figure 2]. The PPA of PDs toward ranking applicants using their SM accounts ranged from 16.67% to 93.3%, with an average of 55.5% ±17.3% (a median of 56.6%).

Figure 2.

Perceptions of program directors on the ranking of applicants of family medicine residency programs using digital media accounts

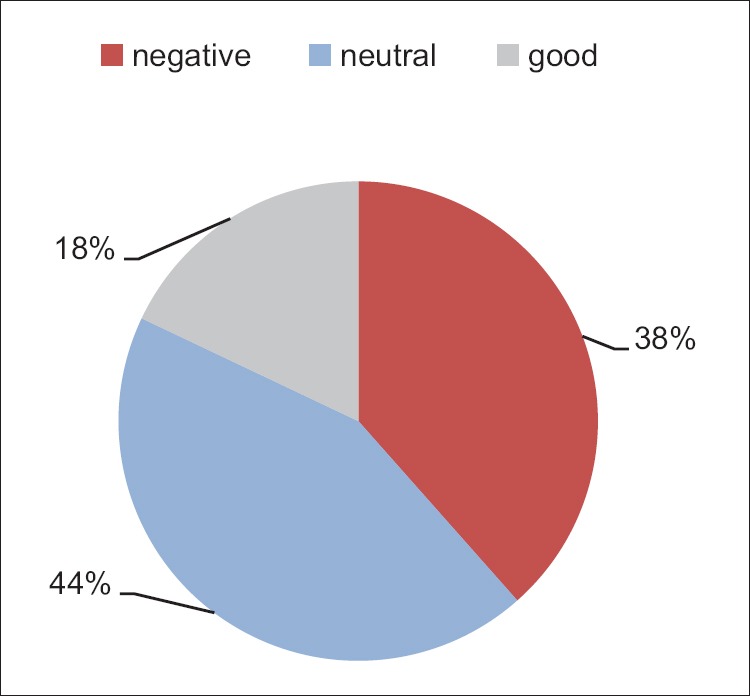

Only 18% had good attitude [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Attitudes of program directors toward ranking applicants using digital media accounts

The average PPA was higher among those who used SM to communicate with residents (60.2% ±19.5%) than those who did not (49.4% ±12%; P = 0.04), even after adjusting for familiarity with the use of the Internet. Directors at hospitals of the Ministry of Education had higher percentages, but the figures are not statistically significant. The relationship with the type of hospital, whether it has a social networking profile, province, or the PD's gender did not reach statistical significance.

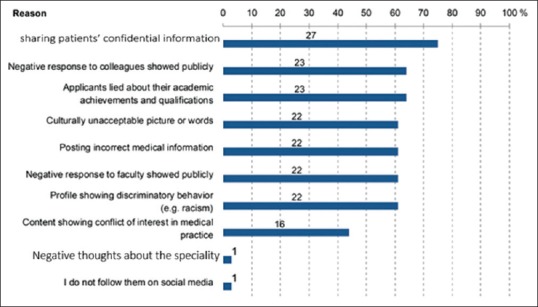

The reasons why directors indicated that they might lower an applicant's ranking on seeing his/her SM profile included: (1) sharing confidential patient information (75%); (2) public expression of negative reactions to colleagues (64%); (3) lying about academic achievements and qualifications (64%); (4) culturally unacceptable images or language (61%); (5) posting incorrect medical information (61%); (6) public expression of negative reaction to faculty members (61%); (7) expression of discriminatory behavior in applicant's profile (e.g., racism) (61%); (8) presenting a conflict of interest in medical practice (44%); and (9) negative ideas about one's area of expertise (3%) [Figure 4]. About 30.7% agreed or strongly agreed, and 20.5% were neutral on whether it was justifiable for a PD to judge a candidate's professionalism according to his/her behavior on SM.

Figure 4.

Distribution of perceived reasons that might lower an applicant's ranking if director sees his/her social media profile

Nearly 38% of the PDs mentioned that this survey had changed their view of the relationship between admissions and SM networks, which encouraged us to continue with the second phase of the study (qualitative phase).

We conducted a semi-structured interview with a total of ten FMPDs from six different cities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in the presence of a SM engineer and a physician who owned a professional medical channel on YouTube.

Two participants had active SM accounts. The other eight PDs had inactive accounts or none. We categorized them into the following three groups according to their opinions: (1) those who agreed that SM was an essential tool for consideration; (2) those who agreed with conditions; and (3) those who disagreed.

PDs who agreed emphasized the importance of e-professionalism and social reputation. Some considered SM accounts as part of one's curriculum vitae. One said: “Some sort of background check has always been there; for example, the stability of the applicants' in previous jobs, their reputation, and their personal life. We used to ask applicants about themselves during interviews, now things have changed, and we have moved on to SM.” Another remarked: “For the sake of employment, consideration of e-professionalism, check on SM accounts plus the interviews help us make the right decision.”

One said, “This technology gives me a general impression of the employee.” Another stated: “We might find something ethically unacceptable that could lower the candidate's ranking. For example, doctors who are SM celebrities might have a conflict of interest.”

Other PDs agreed but mentioned that additional aspects need to be considered, such as the presence of third-party experts who can determine the applicant's social reputation. Furthermore, PDs would rather not use this tool until clear institutional guidelines on e-professionalism and the proper use of SM among health-care professionals are set. One mentioned: “This tool is subject to variations, we need clear boundaries about what constitutes e-professionalism.” Another said: “I need an SM expert to search the applicants.”

A few PDs disagreed because they thought it violated confidentiality. One stated, “This tool breaches the candidate's privacy,” whereas another asked, “What if the candidate was remorseful of previous behavior?” A few thought that it is necessary to obtain permission from candidates before viewing their profiles.

One PD claimed, “I will inform the candidate that we gave marks for e-professionalism and ask to review his/her account on SM. If the applicant disagreed, his/her e-professionalism score would be adversely affected.”

With regard to the timing of SM screening, it was clear that most PDs preferred to check candidates' SM accounts after the interview. One remarked: “I will try not to check the applicant's SM account prior to the interview in order not to be biased.” While others preferred prior screening; one said, “It would be helpful to view SM accounts before interviewing candidates, especially if the list of applicants is long so that we can eliminate candidates with unacceptable behavior.”

The PDs perceived the need to form a team of SM experts comprising legal and human resources specialists to establish an action plan at the organizational level. One thought that “A committee with experts from different backgrounds should be to set up to define e-professionalism.” Another believed that “Guidelines should be drawn to be reviewed periodically by a committee of experts.” Another stressed, “We need to have a clear legal framework to report on rejected candidates based on what is found in their SM profiles.”

Most PDs emphasized the importance of designing a culturally, religiously, and nationally appropriate code of ethics for the use of SM. One said, “Although there is a consensus on ethical principles, policies vary across cultures.”

All the PDs agreed on the importance of establishing guidelines for the proper use of SM. One suggested creating a template for ranking criteria to minimize variations among PDs. He recommended that “objective criteria should be defined and templates should be established and generalized.” Another suggested defining “the weight of SM in terms of ranking and fostering equity between SM users and nonusers.”

We used Keyhole to examine two Twitter accounts of PDs and explored their SM engagement. We found that PD#1 had a total of 7056 posts, 8434 followers, follows 463 accounts, and an average engagement rate of 0.19% in a period of 1 month. PD#2 had a total of 12,038 posts, 86 followers, follows 142 accounts, and an average engagement rate of 0.04%. The followers of both accounts were mostly from Saudi Arabia, the U.A.E., Canada, and the U.S. The accounts had a high degree of medical content. We also observed communication with residents.

We ranked some of the top posts on the level of engagement as follow:

“Antibiotics prescription for an acute sore throat: NICE guideline 2018” had 107 likes and 34 retweets

”#Hepatitis B serology interpretation” had 86 likes and 24 retweets.

Discussion

Social media is the language of today. Health-care professionals are engaged with SM and interact more closely with the public. Classical ethical solutions might not adequately resolve the new problems that emanate from technology. However, it is important to maintain a strong public image of trusted physicians in the context of SM.

Overall, we found that most PDs were not aware of SM's role in the selection criteria. We observed a clear gap in the PDs' use of SM, which may be explained by the differences in the older generation's perception of the role of SM, as well as the resistance to stay abreast with the fast digital revolution owing to their busy lives, a lack of skills and interest, and the inability to search for applicants on SM platforms.

In our study, the majority of respondents (84.6%) had SM profiles. We found a higher rate of engagement with SM compared to a previous study done in 2016 (68% for Facebook). It is said to be one of the investigations with the highest rates of usage recorded (in comparison to prior research).[7] Most of the PDs we interviewed use Twitter and Facebook.

In general, PDs with a positive perception of SM strongly agreed that they would search for candidates using search engines (33.3%) or SM (35.9%); 25.6% and 20.5% of the participants were neutral, respectively. We observed a higher positive perception in our study in comparison to a similar investigation, for which positive views comprised 15% for the use of search engines and 14% for the use of social networks.[3]

With regard to the general views of the PDs, we found that less than half had a positive outlook. However, 79.5% replied that they would warn residents if they noticed breaches of confidentiality on SM platforms. Some PDs who resisted the use of SM for the ranking criteria and had a negative response to the first question changed their opinions after they were asked more specific questions on conventional ethical areas such as patient confidentiality that might be violated on SM networks.

The PDs mentioned several bases on which an applicant's ranking on the SM profile could be lowered. These included: (1) The sharing of confidential patient information (the most frequent reason, mentioned by 75% of the participants); (2) public expressions of negativity toward colleagues (64%); and (3) lying about academic achievements and qualifications (64%). Nevertheless, the order of the reasons was not the same as in a previous study: sharing confidential patient information accounted for 7.1%; the most frequently cited reasons in that study were sharing inappropriate content or photographs (92.9%) and public expressions of negative reactions to colleagues (14.3%).[5]

In our study, the average PPA was higher in those who use SM to communicate with residents (60.2% ±19.5%) than those who did not (49.4% ±12%; P = 0.04), even after adjusting for familiarity with Internet usage. We found a study that mentioned the relationship between personal use and communication with residents by anesthesiology PDs, 83.3% of whom did not engage in SM routinely. Those who claimed that they did not utilize SM for personal reasons comprised 96% and said that they did not use SM to communicate with residents.[5] This means that PDs who were familiar with SM usage were more likely to adopt a refined criteria of acceptance that included e-professionalism.

Directors at hospitals run by the Ministry of Education had a higher PPA. Thus far, published research has not assessed this factor in a meaningful way.[2,4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]

In our study, 46.1% of the participants thought that SM profiles reflected a physician's character; this is a relatively low percentage compared to another study that assessed this factor. In that study, 79.9% of the respondents agreed that what was in a candidate's account reflected that person's behavior as a physician.[8]

The FMPDs in our study thought that searching for applicants through Internet search engines (25.6%) or on SM (27.6%) compromised their privacy. This outcome is similar to that of another investigation, which found that only 19% of PDs thought that this was a violation of the candidate's privacy.[4]

After results for the quantitative portion of the study were reached, we moved on to the qualitative section and explored in depth the perceptions of PDs toward the ranking of applicants using their SM accounts, how they dealt with e-professionalism, and the extent to which they considered reputation as a factor. Very few qualitative studies in this area did not meaningfully address the matter.[6]

Some PDs thought that reviewing an applicant's SM account prior to the interview facilitated the acceptance process whereby a shortlist of probable candidates is drawn up if PDs find unacceptable behavior on the Internet. On the other hand, an investigation conducted in 2013 concluded that a Google search of an applicant was a waste of time; however, the authors of that study did not examine the role of SM in assessing applicants.[9]

Most of the PDs interviewed agreed on the importance of SM behavior and how inappropriate behavior could jeopardize a candidate's chance of acceptance. The participants had a relatively high positive perception compared with those in previous research.[10]

Some PDs thought that it was logical to consider SM as a ranking criterion for today's generation. This finding is similar to that of the investigations discussed in a systematic review published in 2017.[15] Another study discussed how the doctor–patient relationship was changing due to SM and how this might affect professionalism.[16]

One of this study's strengths is that it was a large-scale investigation covering all of the provinces of Saudi Arabia. As far as we are aware, this is the first mixed methods study that tested the perceptions of FMPDs toward ranking applicants using their SM accounts and took their e-professionalism and social reputations into account.

No selection bias was caused by administering a web-based questionnaire. We assessed the engagement of PDs across nine SM platforms. The study limitation was smaller number of FMPDs in Saudi Arabia (n = 41).

Policymakers can use the results to develop SM guidelines for health-care professionals with the local culture in mind, to minimize variation in the acceptance and rejection practices among employers/PDs during the process of selecting candidates

Improving students'/residents' professional use of SM in medical practice

Updating the selection criteria to suit the innovations of the digital generation

Implementing a scoring system that incorporates e-professionalism and social reputation into admission criteria

Conducting qualitative studies involving experts with a legal background. These include physicians, digital media experts, and lawyers to help construct a code of ethics

Developing a code of ethics for utilizing SM

-

Minimizing ethical dilemmas concerning health and SM

- Defining the line between e-professionalism and social life on SM

- Ensuring that privacy settings adequately protect doctors, given that these settings do not guarantee leakage of information.

Minimizing conflicts of interest and unethical ads by health-care professionals on SM to maintain the public's confidence and trust in physicians.

Conclusions

It is vital that we formulate bioethical regulations to meet the needs of the new digital age. Culturally and nationally appropriate guidelines for the use of SM by health-care professionals are urgently required. Such bioethical guidelines will help minimize inappropriate behavior and increase patient sense of safety.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Magdy Darwish and Dr. Amr Sabra for validating the questionnaire, Dr. Badr Almotairi for arranging the scientific committee meeting, as well as the engineers Ahmed Al-Fnais and Dr. Mushari Al-Shuraim for sharing their knowledge on SM and technology. We also appreciate the efforts done by data collectors and the study subjects for participation in the study.

References

- 1.Nepal S, Paris C, Georgakopoulos D. Social Media for Government Services: An Introduction. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cain J, Scott DR, Smith K. Use of social media by residency program directors for resident selection. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67:1635–9. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omair A. Introduction to clinical research for residents. J Health Spec. 2014;2:184. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker AL, Wehbe-Janek H, Bhandari NS, Bittenbinder TM, Jo C, McAllister RK, et al. A national cross-sectional survey of social networking practices of U.S. Anesthesiology residency program directors. J Clin Anesth. 2012;24:618–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Go PH, Klaassen Z, Chamberlain RS. Attitudes and practices of surgery residency program directors toward the use of social networking profiles to select residency candidates: A nationwide survey analysis. J Surg Edu. 2012;69:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffis HM, Kilaru AS, Werner RM, Asch DA, Hershey JC, Hill S, et al. Use of social media across US hospitals: Descriptive analysis of adoption and utilization. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e264. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langenfeld SJ, Cook G, Sudbeck C, Luers T, Schenarts PJ. An assessment of unprofessional behavior among surgical residents on facebook: A warning of the dangers of social media. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:e28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulman CI, Kuchkarian FM, Withum KF, Boecker FS, Graygo JM. Influence of social networking websites on medical school and residency selection process. Postgrad Med J. 2013;89:126–30. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin NC, Ramoska EA, Garg M, Rowh A, Nyce D, Deroos F, et al. Google internet searches on residency applicants do not facilitate the ranking process. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:995–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Go PH, Klaassen Z, Chamberlain RS. Residency selection: Do the perceptions of US programme directors and applicants match? Med Educ. 2012;46:491–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlitzkus LL, Schenarts KD, Schenarts PJ. Is your residency program ready for generation Y? J Surg Educ. 2010;67:108–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deloney LA, Perrot LJ, Lensing SY, Jambhekar K. Radiology resident recruitment: A study of the impact of web-based information and interview day activities. Acad Radiol. 2014;21:931–7. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ponce BA, Determann JR, Boohaker HA, Sheppard E, McGwin G, Jr, Theiss S, et al. Social networking profiles and professionalism issues in residency applicants: An original study-cohort study. J Surg Educ. 2013;70:502–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey K. Encyclopedia of Social Media and Politics. Washington DC: George Washington University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: A systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92:1043–56. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moubarak G, Guiot A, Benhamou Y, Benhamou A, Hariri S. Facebook activity of residents and fellows and its impact on the doctor-patient relationship. J Med Ethics. 2011;37:101–4. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.036293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]