Abstract

Background:

Thyroid Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES) or transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy using vestibular approach is a recent advance embraced by the surgical community because of its potential for a scar-free thyroidectomy. In this article, we present our initial experience with this technique.

Materials and Methods:

We used a three-port technique through the oral vestibule, one 10 mm port for the laparoscope and two additional 5 mm ports for the endoscopic instruments required. The carbon dioxide insufflation pressure was set at 12 mm of Hg. Anterior cervical subplatysmal space was created from the oral vestibule down to the sternal notch, and the thyroidectomy was done using conventional laparoscopic instruments and a harmonic scalpel.

Results:

From May 2016 to December 2017, we have performed ten such procedures in the Department of General Surgery in our hospital, which is a tertiary referral center. Six patients had solitary thyroid nodules, for which a hemi-thyroidectomy was done. Four patients had multi-nodular goiter and total thyroidectomy or near-total thyroidectomy was done. The preoperative fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was suggestive of Bethesda class 2 lesions in all the patients with multinodular goiter and in five of the six patients with solitary nodular goiter. Only one patient with solitary nodular goiter had a Bethesda class 3 lesion on FNAC. The final histopathological report of the specimen was benign, either colloid goiter, or degenerative nodule in all cases of multinodular goiter and in four cases of solitary thyroid nodule. In one Bethesda class 2 solitary nodule, the histopathological report was suggestive of follicular carcinoma; in the Bethesda class 3 solitary nodule, the histopathological report was suggestive of follicular variant of papillary carcinoma. No complication such as temporary or permanent vocal cord paralysis, hypoparathyroidism, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, tracheal injury, esophageal injury, mental nerve palsy, or surgical site infection was found postoperatively. However, two patients developed small hematomas in the midline.

Conclusion:

Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy is a safe, feasible, and minimally invasive technique with excellent cosmetic results.

KEY WORDS: Endoscopic thyroidectomy using vestibular approach, scar-free thyroidectomy, transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy

Introduction

Thyroidectomy remains a very common procedure in everyday surgical practice to date. However, in recent times, there has been an increasing demand for better safety and better cosmesis. The use of endoscopes and endoscopic instruments for thyroid surgery has allowed surgeons to make small incisions and be minimally invasive.[1]

Endoscopic thyroidectomy can be broadly classified into direct or cervical and indirect or extra-cervical approaches depending on the site of the incision. In the direct approach, a smaller incision is taken on the neck, and endoscopic instruments are used resulting in less surgical dissection and the technique is truly minimally invasive. Extra-cervical approaches such as those approaching from the breast or axilla result in the absence of a visible scar in the neck but require a large amount of surgical dissection.[1] The transoral approach in which the access is through the vestibule of the mouth not only minimizes the surgical dissection but also results in a scar-less neck.[2]

This article describes our initial experience with transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy using vestibular approach in a tertiary care hospital on ten patients.

Materials and Methods

From May 2016 to December 2017, the procedure has been done in ten selected patients by a single surgical unit in the department of General Surgery in our hospital, which is a tertiary referral center. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients undergoing the procedure, and the study has been approved by the ethics committee of our institute.

Indications were small sized (each individual lobe <4 cm) Bethesda class 2 benign thyroid disease such as solitary nodular goiter or multi-nodular goiter, small sized (each individual lobe <4 cm) Bethesda class 3 swellings requiring lobectomy, and thyroid cyst recurring after two sonography guided aspirations. A toxic goiter is not a contraindication for this procedure. Absolute contraindications were (1) previous history of surgery or radiation to the neck and (2) patient unfit for anesthesia. Biopsy proven or highly suspicious of malignant disease (Bethesda classes 4 to 6) is a relative contraindication.

Anesthesia

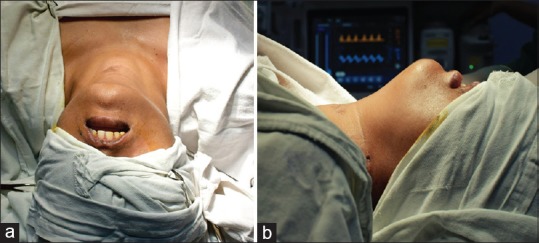

The procedure was done under general anesthesia with nasotracheal intubation with north pole ivory endotracheal tube. The anesthesia machine was kept on the right side, so that the gas pipes did not interfere with the surgeon's position. Injectable amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (1.2 g) was used as a prophylactic antibiotic at the time of induction. The patient was placed in supine position with more extension at atlantoaxial joint than required for conventional technique so as to have the chin and the thyroid cartilage at the same level. However, 15° to 20° reverse trendelenburg position ensured less congestion at the head end [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

(a) Top view and (b) Lateral view of the patient showing adequate extension at the neck

Operative techniques

The camera and the monitor were placed at the foot end of the patient, with the surgeon at the head end with camera surgeon next to him. The oral cavity was cleaned with dilute betadine, and 5 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine with adrenaline was injected submucosally in the vestibule in the inter-canine area.

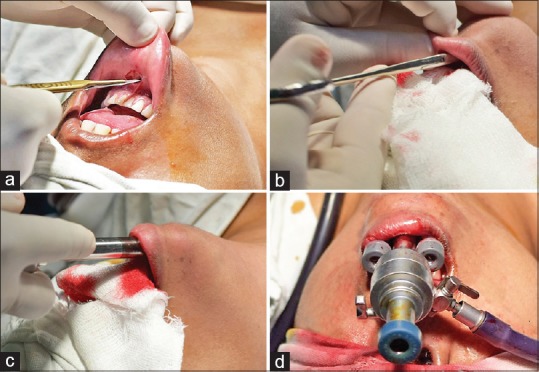

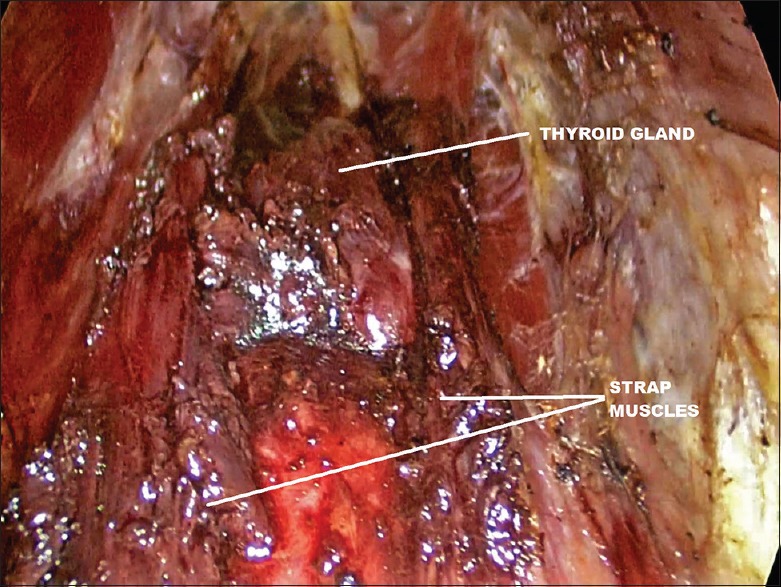

A 10 mm mucosal incision was taken in the midline, and 10 mm trocar was introduced anterior to the mandible, in an attempt to enter the submental triangle without flexing the neck to avoid any injury to the skin [Figure 2]. Space was then insufflated with carbon dioxide (CO2) with a flow of 3 liters/min to build up the pressure to 12 mm of Hg. Blunt dissection was done in midline and space created in the subplatysmal plane, and 5 mm ports were then inserted inside the vestibule into the same space through a separate 5 mm incision on either side in front of the intercanine area. The dissection was extended up to the suprasternal space and laterally beyond the sternocleidomastoids on either side. The deep cervical fascia was divided in the midline to retract the strap muscles [Figure 3]. A percutaneous suture was passed to keep strap muscles retracted. The thyroid was dissected anteriorly from strap to identify the superior pedicle. However, as the working ports were in the same line with visualization port, difficulty was encountered to loop the entire pedicle. To increase the mobility of the thyroid lobe, a plane was created below isthmus and trachea, and the isthmus was divided with ultrasonic shears keeping the active blade away from the trachea.

Figure 2.

(a) 10 mm incision is made in the midline for camera port. (b) Space is created with artery forceps. (c) 10 mm port is inserted above the mandible into the neck. (d) Final placement of working ports through the vestibule

Figure 3.

Endoscopic view from cranial end showing thyroid gland exposed after separating strap muscles

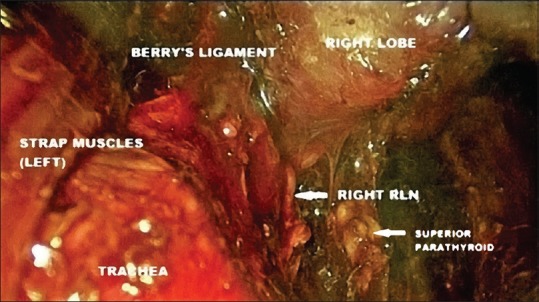

The thyroid was dissected from Berry's ligament. The ipsilateral lobe of the thyroid was retracted in the midline to dissect the upper pole of the thyroid. The superior pedicle was dissected, clipped doubly, and cut. The superior parathyroid was identified, and with blunt and sharp dissection. the thyroid was dissected caudally. The superior branch of the inferior thyroid artery was clipped and cut to identify the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which was dissected away from the thyroid [Figure 4]. The inferior parathyroid was preserved, and the entire lobe was removed. Hemostasis was confirmed, and the specimen was retrieved through the vestibule [Figure 5]. Larger glands were bagged and removed in pieces from the port. The strap muscles were approximated, muscles of the mouth were sutured, and mucosa of the oral cavity was sutured with absorbable suture [Figure 6]. Patients were extubated and were started on liquids within 6 h. Drains were not placed, and oral antibiotics (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) and mouthwashes were continued for 5 days.

Figure 4.

Endoscopic view from cranial end showing right recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN)

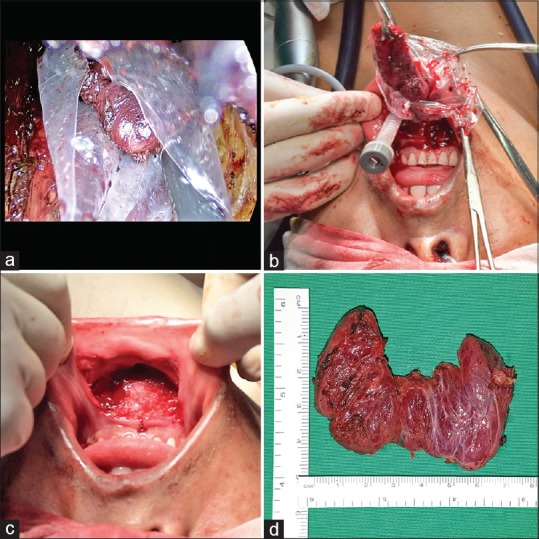

Figure 5.

(a) The specimen is collected in endo-bag. (b) The bag is brought out through the incision and the specimen is retrieved. (c) Postoperative view of the entire incision. (d) Total thyroidectomy specimen

Figure 6.

(a) Approximation of incision with interrupted sutures in two layers. (b) Postoperative view of port sites after closure with inset showing a schematic view of port insertion sites

Results

We have performed ten transoral thyroidectomies since May 2016 in our hospital, out of which, there were eight female patients. The mean age was 29.8 years (range 24–39 years). Six patients had solitary thyroid nodules, and thus, hemi-thyroidectomy was performed. In total, four patients had multi-nodular goiter: total thyroidectomy was performed for one and near-total thyroidectomy was performed for the remaining three patients. The preoperative fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was suggestive of Bethesda class 2 lesions in all the patients with multinodular goiter and in five of the six patients with solitary nodular goiter. Only one patient with solitary nodular goiter had a Bethesda class 3 lesion on FNAC. The final histopathological report of the specimen was benign, either colloid goiter, or degenerative nodule in all cases of multinodular goiter and in four cases of solitary thyroid nodule. In one Bethesda class 2 solitary nodule, the histopathological report was suggestive of follicular carcinoma, and in the Bethesda class 3 solitary nodule, the histopathological report was suggestive of follicular variant of papillary carcinoma. The patient with the follicular carcinoma had no high-risk features and is on regular follow-up. Completion thyroidectomy was done for the patient whose final histopathological report was suggestive of follicular variant papillary carcinoma as there was an extra-capsular extension. The average size of the individual thyroid lobe was 2.6 cm (range 2–3.5 cm).

The mean operative time was 73.70 (range 55–85) min. The mean operative time for a hemi-thyroidectomy was 69.5 (55–85) min and that for near-total or total thyroidectomy was 80 (75–85) min. The average blood loss was 20.50 (15–30) ml. Oral feeding was started 6 h after surgery in all the patients. Tables 1–3 summarize preoperative, operative and postoperative patient characteristics.

Table 1.

Biochemical, radiological, and pathological details of all patients

| Patient Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Hormone status | |

| Euthyroid status | 9 |

| Thyrotoxicosis | 1 (1 MNG) |

| Preoperative USG findings | |

| Solitary nodule | 6 |

| Multi-nodular | 4 |

| Average size of lobe | 2.6 cm (range 2-3.5 cm) |

| Preoperative FNAC findings | |

| Bethesda Class 2 | 9 |

| Bethesda Class 3 | 1 |

| Postoperative histopathological report | |

| Benign (colloid goiter or degenerative nodule) | 8 |

| Follicular carcinoma | 1 |

| Follicular variant of papillary carcinoma | 1 |

USG: Ultrasonography, FNAC: Fine-needle aspiration cytology, MNG: Multinodular goiter

Table 3.

Postoperative complications (n=10)

| Complication | n (rate) |

|---|---|

| Hypoparathyroidism | 0 |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury | 0 |

| Subcutaneous emphysema | 0 |

| Pneumomediastinum | 0 |

| Tracheal injury | 0 |

| Esophageal injury | 0 |

| Mental nerve palsy | 0 |

| Hematoma | 2 (20%) |

| Surgical site infection | 0 |

Table 2.

Operative details

| Details | Value |

|---|---|

| Surgery (n=10), n (%) | |

| Hemi thyroidectomy | 6 (60) |

| Total or near-total thyroidectomy | 4 (40) |

| Operative time (mean, min) | 73.70 (55-85) |

| Hemi thyroidectomy | 69.5 (55-85) |

| Total or near-total thyroidectomy | 80 (75-85) |

| Blood loss (mean, ml) | 20.50 (15-30) |

| Duration of nil by mouth (mean, h) | 6 |

| Hospital stay after surgery (median, h) | 24 (24-36) |

The recurrent laryngeal nerve was visualized in all but two cases and no patient developed temporary or permanent vocal cord paralysis. None of the patients developed hypoparathyroidism postoperatively, and the serum calcium levels done 24 h postoperatively were normal in all the patients. No complications such subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, tracheal injury, esophageal injury, mental nerve palsy, or surgical site infection were found postoperatively. However, two patients developed small hematoma in the midline in the submental triangle, which was managed conservatively.

Oral feeding was started in all patients 6 h postoperatively. Median hospital stay was 24 (24–36) h. The follow-up was at 1, 4, and 12 weeks. All patients had excellent cosmesis and no complications except small midline hematomas, which developed in two patients.

Discussion

The technique of thyroidectomy was described as early as in 937 AD in China.[3] Modern thyroid surgery, however, began in the 20th century with the contributions of Billroth and Kocher.[3] The mortality due to thyroid surgeries decreased from 1 in 6 at the start of Kocher's series to 1 in 500 at the end of it, and he was awarded the Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work in 1909.[4] Thyroid surgery has come a long way since then.

New technologies such as intra-operative monitoring of recurrent laryngeal nerve, postoperative parathyroid hormone assay, and usage of alternative energy sources such as ultrasonic shears and bipolar coagulation have been adopted by the surgical community in an attempt to provide better safety and improved surgical outcomes.[1]

The application of endoscopy in thyroid surgery has meanwhile resulted in minimally invasive thyroidectomies with smaller incisions and better cosmesis.[1] Since Gagner described the first endoscopic parathyroidectomy in 1996, various endoscopic approaches have been reported for thyroidectomy also.[5] Huscher et al. described the first direct endoscopic thyroidectomy in 1997.[6] Direct endoscopic thyroidectomy also called minimal neck incision thyroidectomy can be performed through a central or lateral neck incision smaller than 3 cm under endoscopic guidance and is minimally invasive by way of surgical dissection. However, it still produced a scar in the neck. Indirect endoscopic thyroidectomy or extra-cervical scar-less neck thyroidectomy, however, shifted the scar away from the neck and resulted in truly “scar-less neck” thyroidectomies. The following are the approaches to extra-cervical endoscopic thyroidectomy

Anterior chest wall approach

Areolar breast approach

Axillary approach

Hybrid (anterior combined with axilla) approach

Trans-oral approach.

Although the anterior chest, breast, and axillary approaches produce a “scar-less” neck, they involve large amounts of dissection and are thus not truly minimally invasive. They produce significant postoperative pain due to large dissections and dreaded complications such as brachial plexus and tracheal injury that have never been reported with conventional open thyroidectomy after Kocher's era of “safe thyroidectomy” have been described with these approaches.[7]

The trans-oral approach, also called thyroid NOTES, first described by Witzel et al. in two fresh human cadavers as a sublingual trans-oral approach, produces a “scar-less” neck and also involves much less dissection because of the decreased distance from the floor of the mouth to the thyroid gland and can thus be considered truly minimally invasive.[2] Wilhelm et al. subsequently performed the first thyroid NOTES on eight patients using a sublingual approach.[8] However, the sublingual approach had a high incidence of mental nerve injury (7 out of 8 cases) and because of the limited laparoscopic visualization, a high rate of conversion to open (3 out of 8 cases). Nakajo et al. then reported their study in eight patients using a 2.5 cm incision in the oral vestibule with Kirschner wires for anterior neck skin lifting (gasless technique).[9] All the patients in this study, however, reported sensory disorders around the chin for more than 6 months. Subsequently, studies of thyroid NOTES using trans-oral vestibular approach with CO2 insufflation and one 10 mm port and two 5 mm ports in the vestibule on 12 and 60 patients, were reported respectively by Wang et al. and Anuwong.[10,5] Both these studies did not have any sensory disorders.[5]

In our thyroid NOTES technique, we used one 10 mm camera port and two 5 mm working ports through the vestibule of the mouth. At this point, we emphasize that care must be taken to prevent the incision for the working port from extending beyond the canines as the mental foramen lies at the level of the premolars and lateral extension can cause injury to this nerve. None of the patients in our study developed mental nerve injury. We used CO2 for insufflation at a pressure of 12 mm of Hg and normal laparoscopic instruments. We did not have any incidents of mediastinal or subcutaneous emphysema at this pressure of CO2. The laparoscopic visualization was adequate, and we did not have any conversions to open surgery.

The rates of transient and permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve injury after conventional open thyroidectomy ranged from 2.11 to 11.8% and from 0.2 to 5.9%, respectively. The rates of transient and permanent hypoparathyroidism ranged from 0 to 5.7% and from 0 to 11%, respectively.[5] In our study, no patient developed both these complications. Wang et al. also reported that none of their patients developed either of the complications.[10] In the study by Anuwong, transient recurrent laryngeal nerve injury and hypoparathyroidism were observed in 2 (3.3%) of 60 cases and 3 (5%) of 60 cases, respectively. Nakajo et al. had reported 1 (12.5%) recurrent laryngeal nerve injury and 0 incidents of hypoparathyroidism.[9] We recommend heat coagulation devices to be used with caution especially when applied to the inferior thyroid artery as the recurrent laryngeal nerve usually crosses this artery.

At this point in time, our experience with this technique is limited to benign Bethesda class 2 lesions and Bethesda class 3 lesions, of size less than 4 cm (size of the individual lobe) though literature describes the procedure being successfully used for thyroidectomy with central neck node dissection for papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid.[5] In our study, one patient's histopathology report indicated follicular carcinoma without any high-risk features and the patient is under routine follow-up and is doing well. Another patient's histopathology report was suggestive of follicular variant of papillary carcinoma and the patient had extra-capsular extension and we ended up doing a completion thyroidectomy.

Infection has always been a concern with oral cavity surgeries, as these are clean contaminated wounds, and we recommend antibiotic prophylaxis at induction followed by a full course of antibiotics. We routinely give a course of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (625 mg) twice daily for 5 days and have had no wound infections till date.

Our considerations with this technique are as follows:

The procedure has a learning curve, which is significantly long (literature describes that at least 50 cases are required to be performed to master the surgery[6]). We recommend that beginners should start with smaller, benign lesions, preferably in the inferior pole.(Left side be preferred initially for a dominant right-hand surgeon)

This procedure can be done with instruments used routinely for laparoscopic procedures and requires no special instruments

Port insertion technique should be adjusted to avoid damage to the mental nerve. The camera port should be in the midline and the lateral ports should not cross the canines

The operating space is less and smoke obscures vision. Repeated cleaning of the telescope and smoke clearing are mandatory. Additionally, operating times are longer compared to the open procedure because of the constrained working space and the repeated fogging because of the smoke, but we hope to cut down the operating time as we gain more experience with the procedure

For smaller lesions (less than 3 cm), we recommend starting the dissection at the inferior pole as this then provides mobility at the superior pole and easier clipping of the superior pedicle

Care must be taken to identify and preserve recurrent laryngeal nerve and parathyroid. Tracheal injury should be avoided. Active blade of energy sources should be used away from them

Good hemostasis is absolutely essential and we were able to achieve it in all our cases. In fact, we wait for sufficient time to be absolutely sure that perfect hemostasis has been achieved and have never felt the need for drain placement. There are, however, descriptions in literature of drain placement for total thyroidectomy[5] done using similar trans-oral endoscopic approaches, but we do not recommend routine drain placement. In fact, there are numerous published studies which say that routine drainage is not required even for conventional open thyroidectomy for benign lesions

The specimen is bagged as shown in Figure 5 [a and b]. We use a sterile transparent indigenous plastic bag available with the camera covers routinely used in our institute. The bag is cut to the desired size and introduced through the 10 mm port site, and the specimen bagged and retrieval are done as it is done normally for any laparoscopic procedure.

As the surgery is of clean contaminated type, we recommend broad spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis along with due attention to oral hygiene.

Conclusion

Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy is safe, feasible, and minimally invasive technique with excellent cosmetic results. This procedure is perhaps a feasible option for small thyroidectomies done for benign lesions as most of these patients are young women who opt for the procedure only for cosmetic reasons in the first place.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wong K, Lang B. Endoscopic thyroidectomy: A literature review and update. Curr Surg Rep. 2013;1:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witzel K, von Rahden BH, Kaminski C, Stein HJ. Transoral access for endoscopic thyroid resection. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1871–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan CT, Cheah WK, Delbridge L. “Scar less” (in the neck) endoscopic thyroidectomy (SET): An evidence-based review of published techniques. World J Surg. 2008;32:1349–57. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9555-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Philip WS, Laura RH, Leslie JS, John BH. Thyroid. In: Townsend C, Evers B, Mattox K, Beauchamp R, editors. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017. pp. 881–922. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anuwong A. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach: A series of the first 60 human cases. World J Surg. 2016;40:491–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huscher CS. Endoscopic right thyroid lobectomy. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:877. doi: 10.1007/s004649900476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dralle H, Machens A, Thanh PN. Minimally invasive compared with conventional thyroidectomy for nodular goiter. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;28:589–99. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilhelm T, Metzig A. Endoscopic minimally invasive thyroidectomy (eMIT): A prospective proof-of-concept study in humans. World J Surg. 2011;35:543–51. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0846-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakajo A, Arima H, Hirata M, Mizoguchi T, Kijima Y, Mori S, et al. Trans-Oral Video-Assisted Neck Surgery (TOVANS). A new transoral technique of endoscopic thyroidectomy with gasless premandible approach. Surgical Endoscopy. 2013;27:1105–10. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2588-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C, Zhai H, Liu W, Li J, Yang J, Hu Y, et al. Thyroidectomy: A novel endoscopic oral vestibular approach. Surgery. 2014;155:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]