Abstract

Background:

Cyberchondria is the excessive searching of online health information that leads to anxiety and distress. There is scarce information about its prevalence in low and middle-income country settings.

Objectives:

The objective of the study was to assess the prevalence and factors influencing cyberchondria among employees working in the information technology sector in India.

Methods:

An emailed questionnaire-based cross-sectional survey was conducted among 205 employees working in various information technology firms in and around Chennai. The data were analyzed using nonhierarchical k-means cluster analysis to group participants with and without cyberchondria on its four subdomains. The association of cyberchondria with general mental health as measured by the General Health Questionnaire 12 was studied using independent sample t-test. Logistic regression analysis was performed to study the association between general mental health and cyberchondria after adjusting for sociodemographic covariates.

Results:

The prevalence of cyberchondria was 55.6%. The dominant pattern was excessiveness of online searching, requirement of reassurance followed by distress due to health anxiety, and compulsivity. Cyberchondria was negatively associated with general mental health (adj. OR 0.923; 95% CI 0.882–0.967) after adjusting for age, sex, education, and years of service.

Conclusions:

Cyberchondria is an emerging public mental health problem in India. Since it is associated with poor mental health, measures need to be adopted to evaluate, prevent, and treat it at the population level.

KEY WORDS: Cyberchondria, excessiveness, mental well-being, reassurance

Introduction

Cyberchondria has emerged as a phenomenon in recent years with the liberal and easy access to internet and through it to health-related information. Persons who have a tendency of health-related anxiety engage in health-related information search in the internet. They find the information, which push them to more anxiety and distress. This phenomenon is referred to as cyberchondria.[1] Cyberchondria has features of health anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder as well as hypochondriasis, and therefore, some argue that it is a combination of these clinical diagnoses.[2,3] However, some studies have shown the distinct differences between cyberchondria and these other conditions, thus warranting the diagnosis as a separate clinical entity.[2,4]

The cognitive behavioral model of cyberchondria proposes that primarily people with this condition have health anxiety. Due to their reassurance-seeking tendency, they engage in excessive search of online health information. The online health information, instead of relieving their anxiety and providing them reassurance, worsens the health anxiety.[5] In yet another model of cyberchondria, there is illness-related attentional bias. The people with health anxiety tend to selectively attend to only that information online that confirms and worsens their worries about being sick.[5] A third theory of cyberchondria proposes that people with health anxiety have intolerance of uncertainty.[6,7] Excessive online search for health information provides uncertain information that fails to provide a “perfect explanation” for their symptoms. Their intolerance to uncertainty worsens the health anxiety.

Cyberchondria is characterized by excessive use of the internet for searching health-related information. Compulsivity, or the use of internet search which compromises important everyday activities, is a characteristic trait of this condition. The Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS), developed and validated previously, consists of all these components in addition to a mistrust in medical professional subscale.[8] Subsequent validation studies of the scale recommended that this mistrust in medical professional subscale should be dropped.[9] The shortened version of the CSS is a valid and reliable measure of extent of cyberchondria.[10]

Despite an emerging scholarship about cyberchondria, it is not clear whether cyberchondria is prevalent even in low and middle-income countries.

This study was conducted to assess the prevalence of cyberchondria among professionals working in the information technology sector in Chennai, India and to evaluate the covariates associated with it.

Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional survey was conducted through an online emailed questionnaire format using the CSS and the General Health Questionnaire 12 (GHQ 12). The CSS is a 33-item questionnaire developed by McElroy and Shelvin.[8] This questionnaire had been validated in previous studies. An abbreviated 15-item version of this questionnaire was used in this study.[10] Though this version has not been thoroughly validated in the Indian context, content validity testing and internal consistency testing were performed to understand its validity and reliability. GHQ 12 is a screening instrument for identifying minor psychiatric disorders in the general population and within community or nonpsychiatric clinical settings. IT professionals working in Chennai, India were chosen so as to ensure computer and digital literacy as well as uninterrupted access to the internet. We hypothesized that the prevalence in this sample can be extrapolated to all those people who have access to internet. People with known mental disorders (self-reported) were excluded from the study. For calculation of sample size, the prevalence of cyberchondria was assumed arbitrarily to be 40% as no data are available regarding its epidemiology in the Indian population. For a 95% confidence level and 20% relative precision of the estimate, the sample size of 150 was obtained. Accounting for a poor response rate in online emailed surveys, the sample size was increased by another 15%, thus rounding it off to 200. The study was conducted as an emailed survey using Google forms. The human resources (HR) managers of six IT companies in and around Chennai were provided these emailed questionnaires to circulate to the employees working in their companies. Reminders were sent to the HR managers to obtain the responses. The responses were exported to Microsoft Excel sheet and then analyzed using the statistical software SPSS version 21. Each subscale of the CSS was treated as separate scales and their mean and standard deviation scores were computed. Based on the scores in each subscale, the respondents were classified using k-means cluster analysis into two groups, one with (high cluster center scores on all domains) and another without cyberchondria. The mean GHQ 12 scores of these two clusters were compared using an independent sample t-test. Further, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was also performed to understand the factors influencing cyberchondria. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the institution of origin of the study after an expedited review. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study information was provided as part of the survey form in the E-mail that was circulated to the participants. They were also told that the act of beginning to answer the survey would be considered as their implicit consent to participate. Their confidentiality was protected, by anonymizing the questionnaires and delinking the identifying information, such as E-mail and IP address from the database.

Results

Out of 720 persons contacted through the HR managers, 208 responded to the survey. This gave a response rate of 29%. Such a low response rate is usually seen in email-based surveys.[11] Out of the 208 received responses, 3 were incomplete and hence not included in the analysis. The characteristics of the 205 sample population were explored. This was done to determine its composition and it is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample

| Characteristic | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤25 | 101 (49.3) |

| 26-35 | 64 (31.2) | |

| 36-45 | 27 (13.2) | |

| 46-55 | 13 (6.3) | |

| Sex | Male | 123 (60) |

| Female | 82 (40) | |

| Education | Diploma | 3 (1.5) |

| Bachelors | 133 (64.9) | |

| Masters | 68 (33.2) | |

| Doctorate | 1 (0.5) | |

| Years of service | <1 | 44 (21.5) |

| 2-3 | 68 (33.2) | |

| >3 | 26 93 (45.4) |

It is seen that a clear majority (80%) of the respondents were in the age group of less than 35 years. A majority (60%) were men. About 80% of them had more than 2 years of service in the information technology sector.

The responses on the CSS, which was on a frequency type of Likert scale, were evaluated. Choosing an answer to each question grants a score of 1–5, where 1 stands for never and 5 for always. The responses to the CSS are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cyberchondria severity scale responses

| Statement | Never (%) | Rarely (%) | Sometimes (%) | Often (%) | Always (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| If I notice an unexplained bodily sensation I will search for it on the internet | 24 (11.7) | 31 (5.1) | 69 (33.7) | 41 (20) | 40 (19.5) |

| I enter the same symptoms into a web search on more than one occasion | 28 (13.7) | 68 (33.2) | 55 (26.8) | 36 (17.6) | 18 (8.8) |

| Researching symptoms or perceived medical conditions online interrupts other research (e.g., for my job/college assignment/homework) | 69 (33.7) | 44 (21.5) | 57 (27.8) | 21 (10.2) | 14 (6.8) |

| Researching symptoms or perceived medical conditions online interrupts my online leisure activities (e.g., streaming movies) | 77 (37.6) | 54 (26.3) | 50 (24.4) | 15 (7.3) | 9 (4.4) |

| I take the opinion of my GP/medical professional more seriously than my online medical research | 10 (4.9) | 27 (13.2) | 31 (15.1) | 52 (25.4) | 85 (41.5) |

| I start to panic when I read online that a symptom I have is found in a rare/serious condition | 28 (13.7) | 50 (24.4) | 69 (33.7) | 36 (17.6) | 22 (10.7) |

| Researching symptoms or perceived medical conditions online interrupts my work (e.g., writing emails, working on word documents or spreadsheets) | 73 (35.6) | 53 (25.9) | 49 (23.9) | 18 (8.8) | 12 (5.9) |

| I discuss my online medical findings with my GP/health professional | 53 (25.9) | 42 (20.5) | 53 (25.9) | 33 (16.1) | 24 (11.7) |

| I feel more anxious or distressed after researching symptoms or perceived medical conditions online | 39 (19) | 51 (24.9) | 67 (32.7) | 32 (15.6) | 16 (7.8) |

| Researching symptoms or perceived medical conditions online leads me to consult with other medical specialists (e.g., consultants) | 36 (17.6) | 50 (24.4) | 58 (28.3) | 34 (16.6) | 27 (13.2) |

| Discussing online info about a perceived medical condition with my GP reassures me | 28 (13.7) | 30 (14.6) | 58 (28.3) | 48 (23.4) | 41 (20) |

| I trust my GP/medical professional’s diagnosis over my online self-diagnosis | 14 (6.8) | 19 (9.3) | 38 (18.5) | 49 (23.9) | 85 (41.5) |

| When researching symptoms or medical conditions online I visit both trustworthy websites and user-driven forums | 19 (9.3) | 26 (12.7) | 61 (29.8) | 53 (25.9) | 46 (22.4) |

| I have trouble getting to sleep after researching symptoms or perceived medical conditions online, as the findings play on my mind | 61 (29.8) | 50 (24.4) | 46 (22.4) | 30 (14.6) | 18 (8.8) |

| When my GP/medical professional dismisses my online medical research, I stop worrying about it | 20 (9.8) | 24 (11.7) | 49 (23.9) | 50 (24.4) | 62 (30.2) |

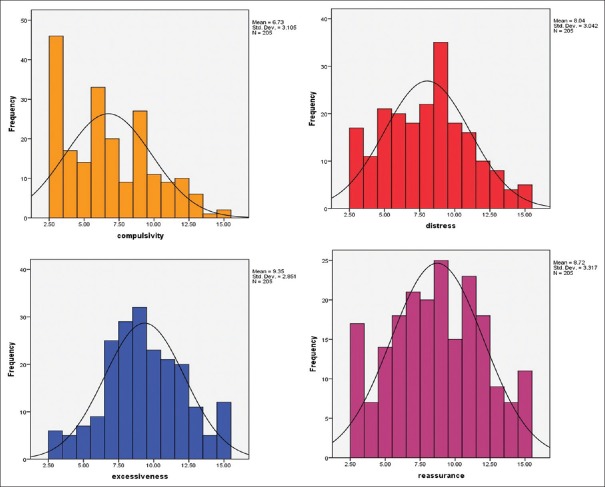

The CSS is categorized into five subscales with three questions in each. These subscales are compulsivity (CM), distress (DS), excessiveness (EX), reassurance (RE), and mistrust (MS). Subscales are used to determine the respective behaviors. Previous studies have shown that the mistrust subscale is not useful and hence it was not analyzed any further in this study.[9] The score distribution on the four subscales is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The score distribution of the sample in the four subscales, namely, compulsivity (mean 6.73; standard division 3.10), distress (mean 8.04; standard division 3.04), excessiveness (mean 9.35; standard division 2.85), and reassurance (mean 8.72; standard division 3.31). It is seen that the mean score was highest for excessiveness and least for compulsivity

The k-means cluster analysis of the scores in the four domains of CSS revealed a classification of the sample of 205 participants into 2 clusters as shown in Table 3. The cluster with higher cluster center scores on all the four dimensions was classified as the cyberchondria cluster (n = 114; 55.6%) and the one with lower scores as the normal cluster (n = 91; 44.4%).

Table 3.

Classification of the study participants into cyberchondria and normal clusters

| Cyberchondria Subscale | Cyberchondria cluster center score (n=114) | Normal cluster center score (n=91) |

|---|---|---|

| Compulsivity | 8.23 | 4.86 |

| Distress | 9.85 | 5.77 |

| Excessiveness | 10.66 | 7.70 |

| Reassurance | 10.63 | 6.33 |

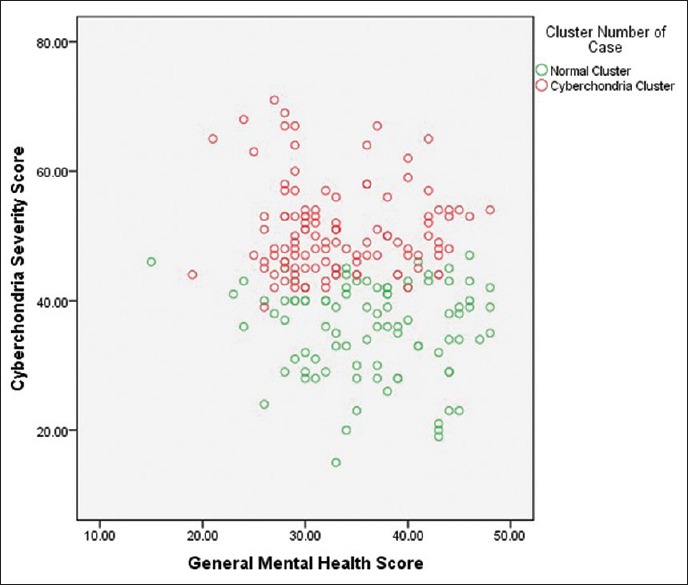

The scatter plot of the CSS score and the GHQ 12 score of the participants belonging to the cyberchondria cluster and the normal cluster are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The negative correlation between the general mental health score and the cyberchondria severity score among the participants who were classified as having cyberchondria and those classified as being normal. It is seen that the participants having cyberchondria (red dots) had greater cyberchondria severity scores and lesser general mental health scores

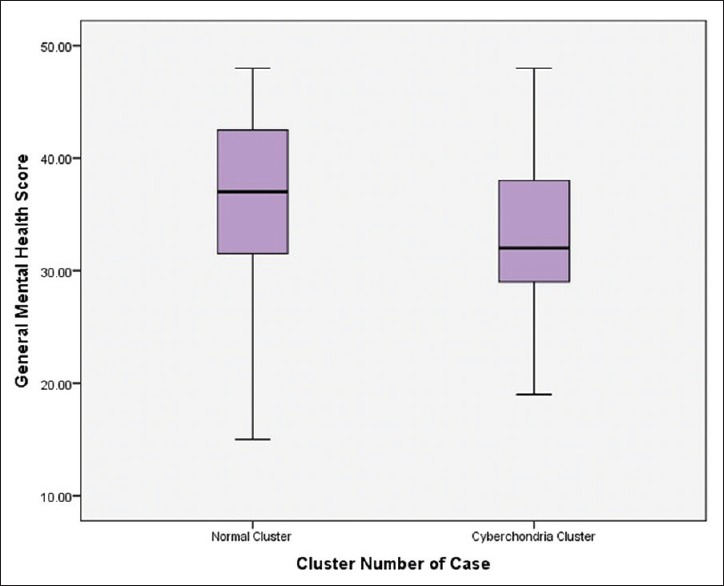

The mean general mental health scores of the participants belonging to the cyberchondria cluster and the normal cluster were compared using an independent sample t-test. It is shown in Figure 3. It was seen that people belonging to the cyberchondria cluster had statistically significant lower mean general mental health score compared to normal people.

Figure 3.

The box plot of the mean general mental health scores obtained from the GHQ 12 scale for the two clusters. The cyberchondria cluster had a lower mean general mental health score and this was statistically significant by the independent sample t-test (P < 0.001)

The multivariate logistic regression analysis to detect the factors influencing cyberchondria revealed that age, sex, education, or years of service did not influence it. After adjusting for age, sex, education, and years of service, the general mental health score of the participants was significantly associated with cyberchondria (adj. OR 0.923; 95% CI 0.882–0.967). This is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors influencing cyberchondria

| Factor influencing cyberchondria | Categories | Cyberchondria cluster (%) | Normal cluster (%) | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <25 | 45 (44.6) | 56 (55.4) | 0.778 | 0.499-1.211 |

| 26-35 | 24 (37.5) | 40 (62.5) | |||

| 36-45 | 15 (55.6) | 12 (44.4) | |||

| 46-55 | 7 (53.8) | 6 (46.2) | |||

| Sex | Male | 38 (46.3) | 44 (53.7) | 0.861 | 0.478-1.552 |

| Female | 53 (43.1) | 70 (56.9) | |||

| Education | Graduation | 56 (41.2) | 80 (58.8) | 1.369 | 0.725-2.582 |

| Postgraduation | 35 (50.7) | 34 (49.3) | |||

| Years of service | <1 | 25 (56.8) | 19 (43.2) | 1.471 | 0.894-2.421 |

| 2-3 | 23 (33.8) | 45 (66.2) | |||

| >3 | 43 (46.2) | 50 (53.8) | |||

| General mental health score (GHQ 12) | 0.923* | 0.882-0.967 | |||

*Statistically significant at P<0.001. OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval

Discussion

This study revealed that more than half the participants (55.6%) had some form of cyberchondria. The cyberchondria severity was negatively correlated with the general mental health of the participants. None of the sociodemographic characteristics assessed in this study influenced cyberchondria and cyberchondria was influenced by the general mental health of the participants even after adjusting for all these covariates. The following paragraphs will discuss the prevalence and pattern of cyberchondria, the association between general mental health and cyberchondria, the strengths and limitations of this study, and the implications of these findings.

Prevalence and pattern of cyberchondria in the Indian setting

The study sample consisted mainly of young males with a graduate degree working for more than 2 years in the information technology sector. This is representative of the typical young IT sector employees in India. In this sample, the prevalence of some form of cyberchondria was as high as 55.6%. The exact proportion of these participants who had less severe and more sever forms of cyberchondria is not clear. As the CSS has not been thoroughly validated in the Indian context, standard threshold values of the CSS scores could not be used to identify and classify participants with varying degrees of cyberchondria. Instead, a nonhierarchical classification protocol using the k-means cluster analysis was performed. k-Means cluster analysis is a method which utilizes statistical methods to group individuals with similar characteristics together.[12] In this analysis, those who are similar with respect to certain characteristics are grouped together and those who are very different from each other are grouped apart. Thus, without using any standard cutoff values, but just by grouping together participants with high scores on all four subscales of cyberchondria and those with low scores, the analysis was able to identify and classify people with cyberchondria.

The pattern of cyberchondria identified in the Indian context was dominated by the excessiveness, followed by requirement for reassurance. The less dominant domains were distress and least dominant one was compulsion. Of the four domains of cyberchondria, compulsivity and distress are the most disruptive because they hamper everyday life and mental well-being. These are the more severe and negative dimensions of cyberchondria. Therefore, the pattern of cyberchondria seen in this context may be said to be mild.

Association between cyberchondria and general mental health

The GHQ 12 is a popular scale that measures the general mental health at a population level. It is a useful screening tool that helps identify common mental disorders like depression and anxiety at a population screening level.[13] In this study, it was seen that the general mental health was inversely related to severity of cyberchondria. Lower the general mental health, greater the cyberchondria. The relationship between general mental health and cyberchondria may be a reciprocal one. As discussed in the introduction, poor general mental health in the form of anxiety disorder, more specifically health anxiety, may predispose to cyberchondria, and cyberchondria, due to its compulsivity and distress components, may lead to poor general mental health. In cross-sectional studies such as these, it is difficult to say which of the two relationships is indicated by the association. In this sample of participants, it is clear that the distress subscale scores are very less and therefore psychological distress contributes less to cyberchondria classification. Therefore, the psychological distress measured in the GHQ 12 is independently associated with the cyberchondria that is measured using the CSS.

This study does not clarify the theoretical basis of association between health anxiety, cyberchondria, compulsivity, and other mental health issues, as it has employed a cross-sectional design, which cannot study temporal relationship between these variables. However, it does show a clear association between cyberchondria and general mental health, independent of the distress subscale of the cyberchondria measure itself. The study also considers important confounding variables such as age, gender, years of work, and education, and even after adjusting for these confounders, it reports an association between cyberchondria and general mental health. This finding has important clinical and public health implications.

Implications of the study findings

Cyberchondria is an emerging problem in India with greater access to internet and health-related information. This is particularly important among the young information technology sector employees, who have constant uninterrupted access to internet. This study affirms this concern by demonstrating a high prevalence of 55.6%. The finding that cyberchondria is associated with general mental health has implications for mental health promotion among young employees of the IT sector. In the background of increasing rates of distress among IT employees in India, this compounds the issue of mental well-being.[14] Efforts to reduce levels of cyberchondria have to focus on regulating the quality of health-related information on the internet, increasing online health literacy among users, incorporating evidence-based diagnostic algorithms in popular online health information pages and sites, and providing counseling services to those affected by cyberchondria.[15,16,17]

Although this study sampled only employees in the IT sector, the findings are likely to be similar in other populations which have similar access to internet and internet-based health information. It is not uncommon to find people coming to hospitals and clinics armed with questions and doubts that arise after internet search.[18] Therefore, there is a need to expand the scope of this study and evaluate the prevalence of cyberchondria in the population at large.

Strengths and limitations of the study

To the best knowledge of the authors, this is the first study to document the prevalence of cyberchondria in a specific occupational group in India. It heralds the important area of research in the country. There are a few limitations in this study. The sample was selected from a very specific occupational group and so the findings may not be generalizable to the population. Moreover, the pattern of cyberchondria may be different in this setting compared to the general population or a typical psychiatric clinical setting. The CSS has not been thoroughly validated in the Indian context, other than the content validation performed for this study. A thorough validation and calibration of the scale may be required for future research. The low response rate of the emailed questionnaire in this study is likely to have resulted in a selection bias, with the ones with most access to internet and email responding to the survey. The sample size was calculated for estimating prevalence of cyberchondria. However, several hypotheses have been tested. Though the sample size required for the logistic regression analysis is met (20 observations per variable in the model), there is a possibility that the study may be underpowered for some of the hypothesis testing that has been performed. The cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to assess temporal and reciprocal relationships between cyberchondria and general mental health.

Conclusions

This study has unraveled a high prevalence of cyberchondria among employees working in the information technology sector in India. Cyberchondria, as characterized in this study, has a mild pattern dominated by excessiveness and reassurance. It is associated with poor mental health. Therefore, future studies on cyberchondria are required in India to better characterize and understand the condition and take measures to prevent it.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Starcevic V, Berle D. Cyberchondria: Towards a better understanding of excessive health-related internet use. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:205–13. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norr AM, Oglesby ME, Raines AM, Macatee RJ, Allan NP, Schmidt NB, et al. Relationships between cyberchondria and obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230:441–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiken M, Kirwan G. The psychology of cyberchondria and cyberchondria by proxy. in Cyberpsychology and New Media A thematic reader. In: Power A, Kriwan G, editors. London and New York: Psychology Press, Taylor and Francis Group; 2014. pp. 158–69. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fergus TA, Russell LH. Does cyberchondria overlap with health anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms? An examination of latent structure and scale interrelations. J Anxiety Disord. 2016;38:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Te Poel F, Baumgartner SE, Hartmann T, Tanis M. The curious case of cyberchondria: A longitudinal study on the reciprocal relationship between health anxiety and online health information seeking. J Anxiety Disord. 2016;43:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fergus TA. Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty as potential risk factors for cyberchondria: A replication and extension examining dimensions of each construct. J Affect Disord. 2015;184:305–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norr AM, Albanese BJ, Oglesby ME, Allan NP, Schmidt NB. Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty as potential risk factors for cyberchondria. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:64–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McElroy E, Shevlin M. The development and initial validation of the cyberchondria severity scale (CSS) J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28:259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norr AM, Allan NP, Boffa JW, Raines AM, Schmidt NB. Validation of the cyberchondria severity scale (CSS): Replication and extension with bifactor modeling. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;31:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barke A, Bleichhardt G, Rief W, Doering BK. The cyberchondria severity scale (CSS): German validation and development of a short form. Int J Behav Med. 2016;23:595–605. doi: 10.1007/s12529-016-9549-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheehan KB. E-mail survey response rates: A review. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2001;6:621. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Punj G, Stewart DW. Cluster analysis in marketing research: Review and suggestions for application. J Mark Res. 1983;20:134–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumann M, Meyers R, Bihan EL, Houssemand C. Mental health (GHQ12; CES-D) and attitudes towards the value of work among inmates of a semi-open prison and the long-term unemployed in Luxembourg. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharya S, Basu J. Distress, wellness and organizational role stress among IT professionals: Role of life events and coping resources. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2007;33:169–78. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loos A. Cyberchondria: Too much information for the health anxious patient? J Consum Health Internet Taylor Francis. 2013;17:439–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghaddar SF, Valerio MA, Garcia CM, Hansen L. Adolescent health literacy: The importance of credible sources for online health information. J Sch Health. 2012;82:28–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White RW, Horvitz E. Cyberchondria: Studies of the escalation of medical concerns in web search. ACM Trans Inf Syst. 2009;27:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kothari M, Moolani S. Reliability of “Google” for obtaining medical information. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2015;63:267–9. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.156934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]