Abstract

The objective of this study was to identify determinants of pet food purchasing decisions. An online survey was administered via e-mail, newsletters, and social media. A total of 2181 pet owners completed the survey: 1209 dog owners and 972 cat owners; 26% of respondents were animal professionals. Pet food characteristics ranked the highest were health and nutrition, quality, ingredients, and freshness. The veterinary healthcare team was reported to be the primary (43.6%) and most important source of nutrition information for pet owners; Internet sources were the primary information source for 24.6% of respondents. Most pet owners reported giving equal (53.1%) or more priority (43.6%) to buying healthy food for their pets compared with themselves. Results suggest that pet owners face numerous challenges in determining the best diet to feed their pets.

Résumé

Déterminants des décisions d’achat des aliments pour animaux de compagnie. Cette étude avait pour objectif d’identifier les déterminants des décisions d’achat des aliments pour animaux de compagnie. Un sondage en ligne a été administré par l’entremise de courriels, de bulletins et des médias sociaux. Un total de 2181 propriétaires d’animaux a répondu au sondage : 1209 propriétaires de chiens et 972 propriétaires de chats; 26 % des répondants étaient des professionnels pour animaux. Les caractéristiques des aliments pour animaux qui étaient les plus importantes étaient la santé et la nutrition, la qualité, les ingrédients et la fraîcheur. L’équipe de soins vétérinaires a été mentionnée comme la source primaire (43,6 %) et la plus importante d’information pour les propriétaires d’animaux. Les sources sur Internet représentaient la source primaire pour 24,6 % des répondants. La plupart des propriétaires d’animaux ont signalé qu’ils accordaient une priorité égale (53,1 %) ou une plus grande priorité (43,6 %) à l’achat d’aliments sains pour leurs animaux de compagnie comparativement à eux-mêmes. Les résultats suggèrent que les propriétaires sont confrontés à plusieurs défis en vue de déterminer la meilleure diète pour leurs animaux de compagnie.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Introduction

Pet ownership in the United States has been steadily growing, with 68% of households having at least 1 pet in 2014 (1). Consumer spending on pets has also risen dramatically from $17 billion in 1994 to $58 billion in 2014 (1). A substantial component of this spending has been for pet food, with US consumers having spent an average of $194 per year in 2013 for pet food (2). Concurrently, the pet food industry has expanded to include new retail outlets for pet food, new marketing strategies, and new varieties of pet food. Also, the growing trend of humanization and anthropomorphism of pets has spurred strong marketing messages, ingredient claims, and confusing and often conflicting information on the Internet about the best food for pets (1–3). These factors have made it increasingly difficult for pet owners to make objective pet food purchase decisions. One survey of 900 dog owners found that nearly half responded that choosing the right food for their dog was the most difficult part of pet ownership. In this same survey 52% of dog owners [and 68% of Millennial (ages: 18 to 34) dog owners] responded that their dogs’ nutrition was more confusing than their own, with nearly 25% feeling overwhelmed with the choices available (3).

Several studies have revealed that food characteristics, food recommendation sources, and the relationship between pet and owner seems to be the major factors influencing food purchase decisions (3–10). Food characteristics such as price, ingredients, and quality have been identified by several studies as important considerations for pet food purchasers. Ingredients have been identified in multiple studies to be the most important factor for most pet owners when selecting a food for their pets (4,8). It appears that consumers prefer lower priced pet food, but value natural and organic ingredients (8). While most pet owners feed commercial pet food to their pets, many feed their pets other foods, such as home-prepared foods, table scraps, and raw meat-based diets. This may be in part due to an apparently growing perception that commercial pet foods may not be wholesome, nutritious, and safe, and that other sources of food may be more natural and more nutritious (6). Recommendations for pet food also appear to be important, with research consistently showing that veterinarians are the most common source of information for consumers regarding pet nutrition (6). However, the Internet and social media have become increasingly common sources of pet nutrition information (and misinformation) in recent years (11).

The relationship between a consumer and pet also appears to be an important factor in pet food purchase behavior. A growing trend of anthropomorphism of pets by their owners may also have an impact on pet food selection and purchase (5,12,13). Research has shown that pet owners with the highest anthropomorphism scores placed the most importance on health/nutrition, quality, freshness, and taste of pet food, and also valued taste and variety in their pets’ diets (4). With the humanization of pets, trends in human food and nutrition often spill over into the pet food industry. Some studies have examined whether similarities exist between consumer behavior for themselves and their pets (5,10). One study found that dog owners who are more serious about purchasing healthy food for themselves are more likely to be serious about purchasing healthy food for their dog as well (14). In addition, owners who are price sensitive and loyal to their own food and food brands are also more likely to be price sensitive and loyal to their pets’ food and food brands (5).

The expanding number of pet food options and growing interest among pet owners in feeding their pets the best diets possible have led consumers to struggle to make appropriate pet food purchase decisions (3). Consumers face a dizzying array of pet food choices and a growing wealth of misinformation regarding pet nutrition on the Internet. Understanding how consumers make pet food purchase decisions and what aspects of pet food are most important is essential information for veterinarians to help pet owners make more objective decisions about their pets’ food. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to identify determinants of pet food purchasing decisions.

Materials and methods

A survey was designed to gather information about pet food purchase decisions, including the type of pet owned, factors influencing pet food purchases, owners’ relationship with their pets, and demographics. Survey questions were created based on past consumer behavior research surveys and established scales (4–7,14,15). Most responses were made using a 7-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = somewhat disagree, 4 = neither agree nor disagree, 5 = somewhat agree, 6 = agree, 7 = strongly agree, or 8 = not applicable) or a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 = not at all important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, 5 = extremely important). Pet attachment was assessed by the contemporary version of the Companion Animal Bonding scale (CABS) (15). Scores for the CABS were broken into 3 groups. A high level of bonding was indicated by a CABS score of ≥ 30. An intermediate level of bonding was indicated by a CABS score between 20 and 30 and a low level of bonding was indicated by a CABS score of ≤ 20. The Health Prioritization Gap measure was calculated by subtracting scores of the importance of healthy food for pet ratings from scores of the importance of healthy food for self ratings.

The survey was administered through commercial survey software and was available from July 2015 to February 2016. The survey was designed so that the respondent entered the names of all his or her pets and then the software randomly selected 1 of the respondent’s pets (if they owned more than 1) and asked the questions as they pertained to that specific pet. The survey was designed to take 10 to 15 min to complete. A “snowball” survey recruitment approach was used to invite cat and dog owners to participate in the study. The survey was widely distributed via e-mail; university, veterinary hospital, and pet owner newsletters and e-lists; and social media. Distribution of the electronic survey link was not restricted. Any person who accessed the link was able to provide electronic consent and complete survey questions if they were over the age of 18 and owned a dog or cat at the time of survey distribution. The study was approved by the Tufts University Social Behavioral, and Educational Research Institutional Review Board.

Data were analyzed using Stata 13 statistical software (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). Data are presented for respondents who completed the survey, which was defined as completing at least 80% of the questions. Descriptive data were reported as actual counts and the percentage of respondents. Associations between variables were assessed using Spearman’s rho correlation (for ordinal measures), and mean scores were compared using t-tests. P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Demographics

The online survey was accessed 2484 times with a total of 2181 respondents completing at least 80% of the survey. Fifty-five percent (1209/2181) of respondents answered questions about their dog and 45% (972/2181) of respondents answered questions about their cat. There were no significant differences in demographics for cat and dog owners (data not shown) so these were combined for all results. Respondents were predominately female (1838/1974) and the age of all respondents ranged from 18 to 82 y [mean = 46 y, standard deviation (SD) = 14.6 y]. A notably large proportion (564/1975, 28.6%) of respondents were employed in the veterinary healthcare field or animal industry, including self-identified veterinarians, veterinary technicians, breeders, animal trainers, and/or pet store employees. Most respondents (1981/2181) were the primary decision-makers in pet food purchases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of 2181 pet owners who responded to a survey about pet food purchasing decisions.

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender (out of 1976 respondents) | |

| Female | 1838 (93%) |

| Male | 136 (7%) |

| Annual household income (1965 respondents) | |

| $0 to $25 000 | 156 (7.9%) |

| $25 000 to $50 000 | 334 (17.0%) |

| $50 000 to $75 000 | 277 (14.1%) |

| $75 000 to $100 000 | 304 (15.4%) |

| > $100 000 | 514 (26.1%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 386 (20.0%) |

| Education (1973 respondents) | |

| 12th grade or GED® | 104 (5.3%) |

| Some college/Associate’s degree | 402 (20.4%) |

| College | 663 (33.6%) |

| Non-doctoral graduate degree or professional degree | 521 (26.4%) |

| Doctoral degree | 281 (14.3%) |

| Occupation (1976 respondents) | |

| Veterinarian | 167 (8.5%) |

| Veterinary technician | 158 (8.0%) |

| Breeder | 70 (3.5%) |

| Animal trainer | 155 (7.9%) |

| Pet store employee | 14 (0.7%) |

| None of the above | 1411 (71.4%) |

| Role in food purchase decisions (2181 respondents) | |

| Primary decision-maker | 1981 (90.8%) |

| Some role | 185 (8.5%) |

| No role | 15 (0.7%) |

Characteristics of foods purchased

Respondents were asked several questions regarding what types of food they feed their pets and where they purchase pet foods (Table 2). Eighty-nine percent (1943/2188) of respondents indicated that they feed commercially prepared foods to their pets and over half (1194/2182) of respondents indicated that they fed primarily dry food to their pet. The only significant difference between cat and dog owners was that cat owners were significantly more likely to feed canned food than were dog owners (713/977 for cats versus 419/1211 for dogs; P < 0.001). Thirteen percent (278/2182) of respondents indicated that they fed other types of food to their pet, including raw food, dehydrated food, or supplements. Respondents reported buying their pet food primarily at large specialty stores (26.5%), small “boutique” specialty pet stores (18.5%), veterinarians’ offices (11.91%), and grocery stores (10.9%); other sources included Internet retailers (e.g., Amazon), farmers’ markets, directly from the manufacturer, or from local agricultural feed stores.

Table 2.

Types of pet food purchased and preferred retail outlets for 2181 pet owners who responded to a survey about pet food purchasing decisions.

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Purchase commercial prepared food | 1943 (89%) |

| Primary type of food fed to pet | |

| Primarily dry food | 1194 (54.7%) |

| Equal amounts dry and canned food | 392 (18%) |

| Primarily canned food | 148 (6.8%) |

| Primarily home-prepared food | 84 (3.8% |

| Equal amounts dry and home-prepared food | 74 (3.4%) |

| Equal amounts canned and home-prepared food | 12 (0.6%) |

| Other | 278 (12.7%) |

| Food that is ever part of the pet’s diet | |

| Dry food | 1872 (85.8%) |

| Packaged treats | 1385 (63.5%) |

| Canned | 1132 (51.9%) |

| Table food | 775 (35.5%) |

| Home-prepared | 532 (24.4%) |

| Other | 350 (16.0%) |

| Preferred retail outlet for purchasing pet food | |

| Large specialty pet store | 514 (23.6%) |

| Small “boutique” pet store | 358 (16.4%) |

| Veterinarian’s office | 231 (10.6%) |

| Grocery store | 212 (9.7%) |

| Mass market store | 115 (5.3%) |

| Farmer’s market | 24 (1.1%) |

| Drug store | 2 (0.09%) |

| Other | 483 (22.1%) |

Pet dietary or nutrition information sources

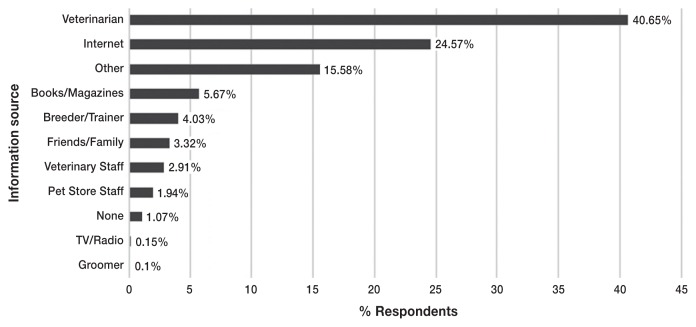

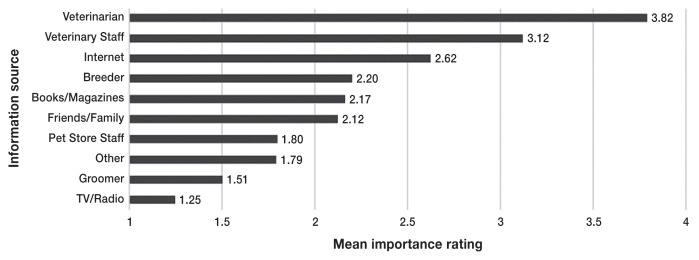

The veterinary healthcare team, including veterinarians, veterinary technicians, and veterinary clinic staff, was the primary pet dietary or nutrition information source for most respondents (853/1958; 43.6%) and Internet sources were the primary information source for 24.6% (481/1958; Figure 1). Other sources of information were the primary source for 15.6% (305/1958) of respondents and included animal nutritionists, owner initiated research and a combination of information sources. When asked to rate the importance of recommendations from different information sources on a 5-point Likert scale, veterinarians and the veterinary staff were ranked to be of the highest importance (3.82 ± 0.03 and 3.12 ± 0.03, respectively), whereas Internet sources were ranked as slightly to moderately important (2.63 ± 1.29; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Primary source of pet dietary or nutrition information for 2181 pet owners responding to a survey. Bars indicate the percentage of respondents.

Figure 2.

Importance of information sources for 2181 pet owners responding to a survey. Bars indicate the mean score reported for each source, where: 1 = not at all important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, and 5 = extremely important.

Factors affecting food purchase

Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with statements about pet food purchases on a 7-point Likert scale. The statements with the strongest agreement related to the importance of providing the pet with the best nutrition possible, buying a pet food that is beneficial for the pet, consistent quality, and feeding a diet that is best for the pet’s medical condition (Table 3). The mean score for being very knowledgeable about how to feed their pets was 6.23 ± 1.02 (agree to strongly agree). The statements with the lowest agreement scores were planning the pet’s meals in advance and changing pet food because the pet gets tired of it.

Table 3.

Agreement with statements regarding pet food purchasing decisions from 2181 pet owners who responded to a survey about pet food purchasing decisions. The number of respondents for each question is listed in parentheses.

| Statement | Agreement |

|---|---|

| I want to provide my pet with the best nutrition possible (2036) | 6.70 ± 0.65 |

| I buy a pet food that is beneficial to my pet (1964) | 6.47 ± 0.82 |

| I buy a pet food that has consistent quality (1980) | 6.43 ± 0.83 |

| I feed a diet that is best for my pet’s medical condition, if applicable (1484) | 6.35 ± 1.00 |

| I am very knowledgeable about how to feed my pet (2018) | 6.23 ± 1.02 |

| I always try to get the best quality for the best price when buying pet food (1970) | 6.03 ± 1.39 |

| I actively seek out information about pet food (1999) | 5.54 ± 1.61 |

| I trust my veterinarian’s advice regarding nutrition for my pet (1977) | 5.28 ± 1.84 |

| I notice when pet food products I regularly buy change in price (1959) | 5.24 ± 1.81 |

| Information on pet food labels is misleading (1993) | 4.90 ± 1.55 |

| I buy pet food that offers value for the money (1940) | 4.83 ± 1.64 |

| I buy a pet food that is reasonably priced (1950) | 4.81 ± 1.61 |

| I enjoy preparing foods for my pet (1842) | 4.63 ± 1.81 |

| Information on pet food labels is easy to understand (1986) | 3.83 ± 1.73 |

| My pet’s meals need to be planned in advance (1941) | 3.70 ± 2.00 |

| I always plan my pet’s meals a few days in advance (1922) | 3.16 ± 2.04 |

| I change pet food because my pet gets tired of the existing one (1887) | 2.76 ± 1.77 |

Importance of food characteristics

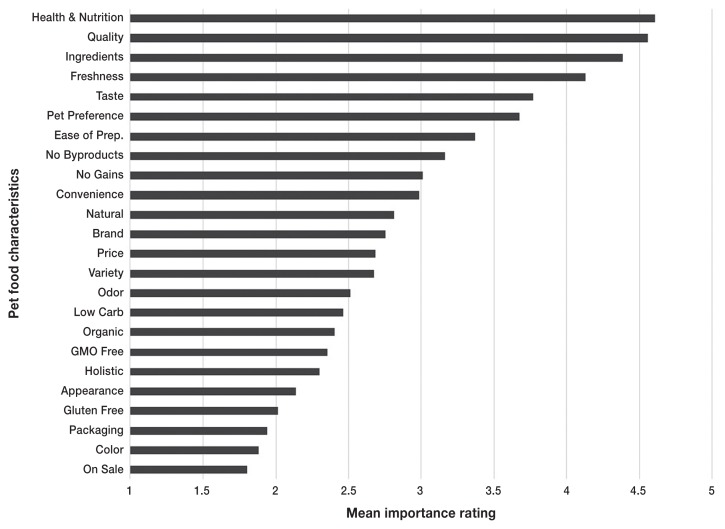

Respondents were also asked to rate the importance of a variety of pet food characteristics on a 5-point Likert scale. Health and nutrition (4.61 ± 0.01), quality (4.56 ± 0.01), ingredients (4.39 ± 0.02), and freshness (4.13 ± 0.02) were ranked as the most important characteristics of pet food by study respondents (Figure 3). In contrast, characteristics rated as slightly important were being on sale (1.80 ± 0.02), color (1.88 ± 0.03), packaging (1.94 ± 0.03), and being gluten-free (2.0 ± 0.04).

Figure 3.

Importance of pet food characteristics for 2181 pet owners responding to a survey. Bars indicate the mean score reported for each source, where: 1 = not at all important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, and 5 = extremely important.

Pet food labels

In order to understand the role of calorie labeling in pet food purchase decisions, respondents were asked about their use and knowledge of calorie labeling on pet food. Most respondents (1446/1931; 74.9%) indicated that they are aware of calorie labeling on pet food but only 1013/1935 (52.4%) of respondents indicated that they use or notice the calorie labels on pet food. To further understand the role and use of pet food labels, respondents were also asked to rate their agreement with 2 statements about pet food labels. For the statement, “Information on pet food labels is misleading,” 63.02% (1256/1993) agreed. For the statement, “Information on pet food labels is easy to understand,” 41.1% (817/1988) agreed and 47.2% (937/1985) did not agree.

The health prioritization gap

Respondents were asked to rate how important buying healthy food was for themselves and how important buying healthy food was for their pet. The owner-pet “Health Prioritization Gap” (i.e., the difference between these separate scores) showed that 1023/1926 (53.1%) of respondents had equal priority for themselves and their pet (Health Prioritization Gap = 0, Equal Priority group). Of the 1926 respondents, 840 (43.6%) had scores indicating a higher importance for buying healthy food for their pet (Higher Priority Pet group), and only 63/1926 respondents (3.3%) had scores indicating a higher priority on buying healthy food for themselves compared to the pet (Higher Priority Self group). The mean age of respondents in the Higher Priority Pet group was slightly but statistically significantly younger (44 y versus 47 y; P = 0.0063) and this group was significantly more likely to actively seek out information about pet food (as indicated by higher rankings to the question “I actively seek out information about pet food”; P < 0.001) compared to the Equal Priority group.

Role of price and brand loyalty

To further examine differences in purchase decisions for the pet versus respondents’ own food, respondents were asked how important changes in price were for their food versus their pets’ food on a 5-point Likert scale. Respondents rated changes in the price of their own food as more important (3.36 ± 0.02) than changes in the price of their pets’ food (2.90 ± 0.03; P < 0.001). There was also a significantly higher score for loyalty to pet food (3.48 ± 0.02) versus owner food (3.22 ± 0.02) brands (P < 0.001).

Bonding scale

The CABS was used to examine the relationship between pet owners and their pets. Most respondents (1770/2042; 86.7%) had a high level of bonding with their pet, while only 12.9% (263/2042) and 0.4% (9/2042) had intermediate or low levels of bonding, respectively. There was a positive correlation between CABS score and agreement with the statement “I enjoy preparing food for my pet” (rho = 0.0793, P = 0.001). There was a negative correlation between CABS and the reported importance of feeding a diet that is low in carbohydrates (rho = −0.0484, P = 0.039), but no correlation with other feeding preferences.

Discussion

Most responders to the current survey wanted to feed their pets the best, most nutritious diet possible. Similar to findings from other studies, the results of this study indicate that pet owners assess the healthfulness, freshness, and ingredients of a pet food when making pet food purchase decisions. However, owners may inaccurately assess how healthy, nutritious, or fresh the pet food or ingredients within a pet food are. While it is encouraging that owners are trying to feed their pets the best nutrition possible, some of the current results suggest that pet owners may misinterpret certain nutrition information, or believe some marketing strategies (e.g., gluten-free, grain-free, raw, holistic) which could result in feeding practices for which there are no scientific studies showing any health benefits to pets. For example, a portion of the sample, albeit small, indicated that feeding gluten-free pet foods was important to them [although the median importance score was only 2 (Figure 3), some owners responded that feeding a gluten-free diet was very or extremely important to them]. The survey did not ask the reason for avoiding gluten but in our experience, it often is out of concern over gluten allergy or sensitivity in pets. However, in dogs, gluten allergy/sensitivity has only been reported in the literature in a family of Irish setters and more recently in a small number of border terriers (16,17). In addition, approximately 3% of respondents said that raw or dehydrated foods were part of their pets’ diets, despite there being no evidence that raw diets offer any health benefits over traditional diets and strong evidence for risks to pet and human health (18). While the survey did not identify why these feeding practices are important to respondents, these results show that some pet owners may engage in feeding practices for which there is no scientific evidence of any health benefit to dogs or cats. Raw or dehydrated food responses were write-in responses rather than explicit survey options; the number of respondents feeding raw meat diets may therefore be underestimated. Better education to foster public understanding of pet nutrition, which is surrounded by much misinformation and confusion, is needed to ensure pets are fed a diet that is truly nutritious, healthy, and has good quality control, not just the food with the best marketing.

The focus on ingredients and good nutrition may reflect how trends in human health and nutrition have begun to spill over into the pet health world. As consumers have become more interested and concerned about what is in their food, they have begun to also focus more on the ingredients and production of their pets’ food. This is supported by the fact that 53% of respondents had a similar rating for the importance of buying healthy food for their pet versus themselves. However, it was surprising that 43.6% of respondents indicated that buying healthy food was more important for their pet than for themselves — a phenomenon that we describe here as the Health Prioritization Gap. This may be a result of the growing bond between pets and their owners, with over 80% of respondents being highly bonded to their pets. However, pet owners may get caught up in food trends instead of focusing on feeding their pets a nutritionally balanced, high quality, nutritious diet. Ingredient claims and strong marketing messages on pet food products may fuel food trends that may or may not be based on proven research. The fact that mean age of respondents in the Higher Priority Pet group was younger and this group was more likely to actively seek out information about pet food compared to the Equal Priority group suggests that younger pet owners may benefit from additional assistance in understanding science and sifting through the information overload about pet nutrition to find accurate information on which to base their decisions. However, given the relatively small difference in ages of the 2 groups, providing additional assistance on optimal pet nutrition to all pet owners may be valuable.

Price was not reported to be a highly important factor in food purchase decisions, with a mean response of 4.81 out of 7 (5 = somewhat agree) on the statement, “I buy a pet food that is reasonably priced.” These findings may be due to respondents being relatively affluent. It is also possible that the question may have been interpreted differently by different respondents and this could have influenced the respondents’ answers. However, respondents rated changes in the price of their own food as more important than changes in the price of their pets’ food, so the lower priority of price for pet food selection could be related to the higher importance of other factors, such as being healthy, nutritious, or containing good ingredients.

The veterinary healthcare team was not only the most commonly reported primary source of nutrition information, but it also was rated as the most important source. This is similar to prior research and identifies an opportunity to proactively provide accurate information to owners on pet nutrition. This underscores the importance of performing a nutritional assessment on every pet at every visit (19,20), which includes assessing body weight, body condition score, muscle condition score, diet, and making a specific nutritional recommendation. Furthermore, it is important that veterinarians receive adequate training and education on nutrition and provide consistent recommendations to pet owners.

Other sources of information such as the Internet or owner research were also identified as important primary information sources in the current survey. However, some owners appear to be using unreliable sources to inform their pet food purchase decisions and they may not fully understand how to properly read a pet food label, to objectively select the best food for their pet, or to evaluate results of nutritional research (20). This may result in owners feeding a diet to their pet that is not nutritionally adequate, safe, or appropriate for their pet’s life stage or medical conditions. Results of this study also revealed that while most respondents trust their veterinarians’ advice, respondents scored their own knowledge about pet nutrition highly and some responded that they did not trust their veterinarians’ advice on pet nutrition. A previous study reported significant differences between owners feeding commercial foods versus owners feeding noncommercial foods in statements indicating mistrust of pet foods, pet food manufacturers, and veterinarians (7).

The current survey revealed that while most pet owners are aware of calorie labeling on pet food, they may not be aware of how to find and properly use this information. Responses in this survey support the clinical impression that information on pet food labels is misleading and is not easy to understand. This finding is supported by prior research showing that over 70% of respondents believed that pet food labels do not list all the ingredients, although pet food labels are required by the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) to list all ingredients (21). Furthermore, consumers may be misinformed about the meaning of certain terms (such as “byproducts”) or information on the label (such as whether the food is complete and balanced or if it has undergone feeding trials) (22,23). This confusion around pet food labels is like the confusion and lack of understanding of consumers’ own food labels. The veterinary healthcare team should take this into account when counseling owners on nutrition. It is important to ensure that the entire veterinary healthcare team is well-educated in evidence-based pet nutrition and that they take the necessary time to educate owners on how to properly understand and use information on pet food labels.

Much of the prior research in consumer behavior with regard to pet food has focused on dog owners. In this study, both cat and dog owners were enrolled, allowing for the comparison of food purchase behavior between dog and cat owners. Overall, no significant differences were found between responses of cat and dog owners, other than a higher proportion of cat owners reporting that they feed canned food. Given this finding, it appears that similar strategies can be employed when counseling cat owners, dog owners, or owners of both cats and dogs on how to best feed their pets.

Limitations of this study include the primarily female, well-educated, and affluent sample that may not represent the larger pet owner population. In addition, employees of the veterinary and animal fields represented approximately 26% of the sample and could represent a biased population. On average, the animal professionals in our sample were younger and better educated than other respondents; were less likely to report that they enjoyed preparing their own food; and illustrated some significant differences in where they purchased food and in the information sources they utilized. Interestingly, the animal professionals did not exhibit significantly different preferences for the labeled attributes of food (such as natural, organic, low-carb, GMO-free) than other respondents, nor did they score significantly different on the companion animal bonding scale.

Furthermore, respondents were recruited for this study primarily by receiving a link to the survey either via e-mail or social media blasts from the veterinary hospital, or through a friend referral. Therefore, the sample may not be generalizable to the greater population of pet owners, particularly as the distribution of the sample in online pet owner communities may attract respondents for whom pet ownership is a stronger part of their self-identity than is the case for the general population of pet owners. Finally, as a survey study, we rely on self-reported behaviors and thus results may not completely reflect how respondents would actually act in a given food purchase situation. In addition, the use of survey questions with predetermined answer scaled may result in varying interpretations or limited answers. Revealed preference measures obtained through observational studies, purchases experiments, or purchase scan data would be useful to investigate whether these self-reports are accurate representations of actual consumer behavior.

In conclusion, ensuring that pets receive proper nutrition requires understanding of consumer behavior in regard to pet food purchase decisions. Increasing marketing claims and misinformation about pet nutrition and the spillover of trends from the human health and nutrition realm into the pet food market complicate the challenging task of educating consumers on how to best feed their pets. However, the strong bond owners have with their pets, their priority for providing their pets with the best nutrition possible, and their use of the veterinary healthcare team for nutritional information provide an excellent opportunity. In order to provide sound nutritional advice to their clients, members of the veterinary healthcare team need to understand the underlying motivations of pet food purchases and why a pet is being fed a certain diet. This information should then be used to provide specific evidence-based recommendations that optimize patients’ health. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.American Pet Products Association. Pet Industry Market Size & Ownership Statistics. [Last accessed February 28, 2019]. Available from: http://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp.

- 2.Statista. Pet Food in The US. [Last accessed February 28, 2019]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/topics/1369/pet-food/

- 3.PetFood News. Dog Owners have difficulty choosing pet food. [Last accessed February 28, 2019]. Available from: http://www.petfoodindustry.com/articles/5407-survey-dog-owners-have-difficulty-choosing-pet-food.

- 4.Boya UO, Dotson MJ, Hyatt EM. A comparison of dog food choice criteria across dog owner segments: An exploratory study. Int J Consum Stud. 2015;39:74–82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen A, Kuang-peng H, Peng N. A cluster analysis examination of pet owners’ consumption values and behavior — Segmenting owners strategically. J Target Meas Anal Mark. 2012;20:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laflamme DP, Abood SK, Fascetti AJ, et al. Pet feeding practices of dog and cat owners in the United States and Australia. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;232:687–694. doi: 10.2460/javma.232.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michel KE, Willoughby KN, Abood SK, et al. Attitudes of pet owners toward pet foods and feeding management of cats and dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;233:1699–1703. doi: 10.2460/javma.233.11.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simonsen JE, Fasenko GM, Lillywhite JM. The value-added dog food market: Do dog owners prefer natural or organic dog foods? J Ag Sci. 2014;6:86–97. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suarez LPC, Carreton E, Juste MC, Bautista-Castano I, Montoya-Alonso JA. Preferences of owners of overweight dogs when buying commercial pet food. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr. 2012;96:655–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2011.01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tesfom GBN. Do they buy for their dogs the way they buy for themselves? Psychol Mark. 2010;27:898–912. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Animal Hospital Association. Survey shows pet owners seek health, nutrition info online. [Last accessed February 28, 2019]. Available from: http://www.aaha.org/blog/NewStat/post/2012/08/01/935220/Clients-seek-health-nutrition.aspx.

- 12.Kienzle EBR, Mandernach A. A comparison of the feeding behavior and the human–animal relationship in owners of normal and obese dogs. J Nutr. 1998;128:2779S–2782S. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.12.2779S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aylesworth A, Chapman K, Dobscha S. Animal companions and marketing: Dogs are more than just a cell in the BCG matrix. Adv Consumer Res. 1999;26:385–391. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jyrinki H. Pets as extended self in the context of pet food consumption. Eur Adv Cons Res. 2006;7:543–549. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson D. Assessing the Human-Animal Bond: A Compendium of Actual Measures. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowrie M, Garden OA, Hadjivassiliou M, et al. The clinical and serological effect of a gluten-free diet in border terriers with epileptoid cramping syndrome. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29:1564–1568. doi: 10.1111/jvim.13643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daminet SC. Gluten-sensitive enteropathy in a family of Irish setters. Can Vet J. 1996;37:745–746. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman LM, Chandler ML, Hamper BA, Weeth LP. Current knowledge about the risks and benefits of raw meat-based diets for dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;243:1549–1558. doi: 10.2460/javma.243.11.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldwin L, Bartges J, Buffington T, et al. AAHA nutritional assessment guidelines for dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2010;46:285–296. doi: 10.5326/0460285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Global Nutrition Toolkit. [Last accessed February 28, 2019]. Available from: http://www.wsava.org/nutrition-toolkit.

- 21.The Ohio State University Veterinary Medical Center. Myths and Misconceptions Surround Pet Foods. [Last accessed February 28, 2019]. Available from: http://vet.osu.edu/vmc/companion/our-services/nutrition-support-service/myths-and-misconceptions-surrounding-pet-foods.

- 22.PetFood Industry. Survey confirms that pet owners need pet nutrition education. [Last accessed February 28, 2019]. Available from: http://www.petfoodindustry.com/blogs/7-adventures-in-pet-food/post/4629-surveys-confirm-that-pet-owners-need-pet-nutrition-education.

- 23.Connolly KM, Heinze CR, Freeman LM. Feeding practices of dog breeders in the United States and Canada. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;245:669–676. doi: 10.2460/javma.245.6.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]